1 Introduction

In the current years, engineering of bio-mimetic materials receive increasing interest for the development of new high-performance nanomaterials in many different fields from biomedecine (e.g. implants) to transport technology (e.g. aerospace) and information technology (nanofluidics, electronics…). In this context, a natural composite such as lignified plant cell wall is a good candidate, which can provide inspiration on how to design and develop nanostructured composite materials [1]. Lignocellulosic cell wall is a complex and highly complex network of nano- or microsized building blocks, where cellulose microfibrils are surrounded by hemicelluloses, lignins and proteins. Notably, cellulose which is formed by repeated connection of D-glucose has specific properties compared to other natural and synthetic polymers such as hydrophilicity, cristalline morphologies, chirality, broad chemical modifying capacity, birefringence… Acid hydrolysis of cellulose microfibrils can lead to stable aqueous suspensions of rodlike nanocrystals whose width (between 3 and 20 nm) and length (between 100 and several micrometers) depend on their biological origin [2]. As a renewable material, cellulose nanocrystal is a fascinating biopolymer that has considerable potential for preparation of low cost, lightweight and high strength nanomaterials.

Over the last 5 years, cellulosic polyelectrolyte multilayers have received wide attention in designing high-performance composite films with low environmental impact for optical [3,4], biological [5], medical [6], and sensor or electronic applications [7]. A great variety of components have thus been used including cationic polyelectrolytes such as (poly(allylamine hydrochloride) [8–11], poly(diallyldimethylammonium) chloride [3,4]), combination of polyacrylic acid and polyethylene oxide [12], polystyrene sulfonate and poly(diallyldimethylammonium chloride) [13], or natural polymers such as proteins [5] or hemicelluloses [11]. The build-up of these multilayered films proceeds via successive nanoscale depositions, and consecutive adsorption of various materials onto a solid substrate thanks to many kinds of driving interactions (electrostatic forces, hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic, charge transfer interactions) [14]. Depending on the type of polymers, their chemical functionalities may vary according to the local environment [14]. Thus, specific processes can be required to assess molecular orientation and organization of the polymer within the multilayer. The layer-by-layer technique is the most simple process for deposition of polyanion/polycation solutions on a charged surface, although films can be inhomogeneous [8]. Multilayer films obtained with cellulose nanocrystals suspensions have thus been reported to display radial orientation of the rod-shaped nanoparticules [8–10] or antireflective (AR) properties [3,4]. The conditions required for this latter property (AR) are that coatings are composed of nanoporous layers with both low refractive indices and high transparency over the entire visible spectrum. Apart from vacuum-deposited dielectric thin films, virtually all antireflection techniques are based on the production of densely packed nanopores on the surface of components. They can be fabricated from one single hybrid layer or multilayers [15]. The nanopores in the film should have smaller size than the wavelength light (no light scattering occurs) to reduce the effective refractive index of the film, n ≈ 1.2–1.3. For an AR multilayer, the technological feasibility of nanoporous layers require two nanoporous layers with low and high porosity which are coated one on top of the other with: (1) satisfactory adhesion between these two layers; (2) satisfactory intrinsic surface roughness that depends mainly on the coating process; (3) satisfactory size of the nanoparticules aggregates and dispersion quality. Beside layer-by-layer, spin-coating is the most widely used technique to produce alternating layers from cellulose nanocristals and amorphous polymer [8,10]. Indeed, spin-coating affords many advantages as films with variable thickness, density and roughness can be obtained while using very weak amounts of aqueous or organic liquid. In addition this technique enables to prepare new multilayer films without any requirement toward electrostatic driving forces between the layers like layer-by-layer method.

Lignin is a typical component of lignocelluloses and consists in a complex phenolic polymer composed of three phenylpropane monomeric building units [16,17]. Owing to its aromatic structure and the fewer hydroxyl groups compare to polysaccharides, lignin is generally considered as a hydrophobic polymer. Lignin being intimately associated with polysaccharides in the cell wall is hardly isolated in the native form [18,19]. Lignin model components (dehydrogenation polymers [DHPs]) can also be synthetized by in vitro polymerization of lignin precursors using peroxidase/H2O2 as oxidizing agents [20,21] Interactions between lignin and polysaccharides in plant cell walls have been extensively studied to improve biomass delignification, which is a key technology for the pulp and paper industry. Such interactions are classified into non-covalent and covalent bonds, and are responsible for the formation of a dense and highly organized network [20]. The occurrence of the covalently linked structure forms, so-called lignin-carbohydrate complexes (LCC), has been repeatedly investigated in fractions isolated from wood [22,23]. These covalent bonds are reported to play a major role in the biological function of plant cell walls (mechanical resistance, recalcitrance to biodegradation). Non-covalent interactions between lignin and polysaccharide cell-wall components have not been investigated to such an extent. However xylan were shown to interact with model lignin component (DHP) via non-covalent linkage, hence these interactions were suggested to be involved in the formation of colloids during DHP synthesis, thereby favoring LCC formation [24,25]. According to Shigematsu et al. [26–28], the interfacial affinity of isolated lignins was higher with hemicelluloses than with cellulose. The knowledge of physical properties and solid-state organization of model lignins was improved by physical techniques in solution and in an anisotropic environment like the air/water interface through the Langmuir technique to exploit both the molecular structure and the spatial arrangement of the lignin [29–31]. The characterization of lignin layers by measurements of the concentration profile and of the optical and rheological properties was shown that DHPs layer with a thickness range from 15 to 36 Å has a non-homogeneous DHP distribution going from a dense structure at the air side to a dilute one at the water side [31] and that after transfer onto glass substrates lignin molecules assume a three-dimensional arrangement even within a single layer with a large free volume, probably forming stable aggregates [32,33]. The long relaxation time and the large dilational modulus are in favor of strong non-covalent interactions between lignin molecules in an aqueous and anisotropic environment [34].

The present study aimed at designing new multilayer cellulose/lignin films with AR properties by spin-coating alternating layers of cellulose nanocrystals and the lignin model compound. One of the challenges for the fabrication of AR coatings is to balance of roughness, thickness and transmittance. The structure and optical properties of the multilayers were investigated by spectroscopy and ellipsometry combined with atomic force microscopy. The occurence of non-covalent binding between the lignin model compound and the surface of cellulose nanocrystals was studied by isotherm adsorption measurements at liquid/NC layer interface.

2 Experimental part

2.1 Materials

2.1.1 Cellulose nanocrystals preparation

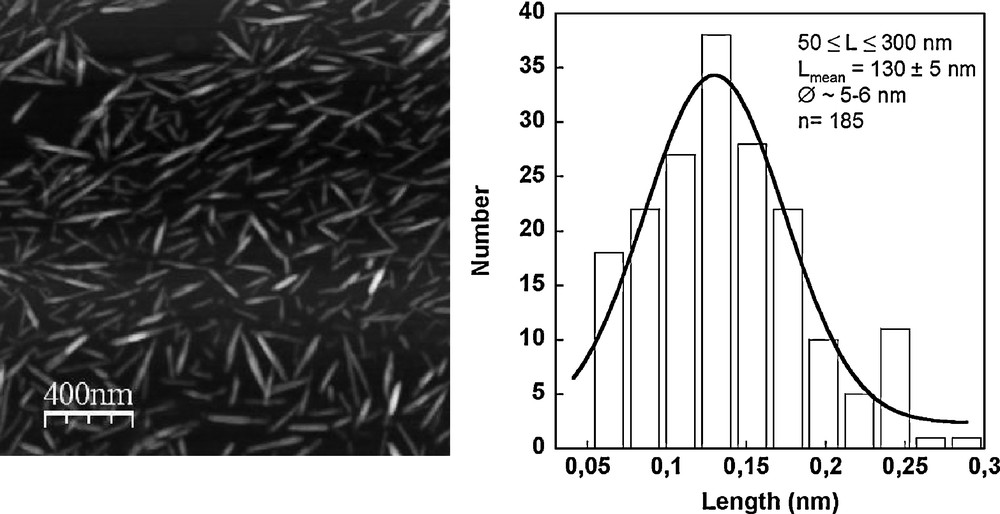

Cellulose nanocrystals (CN) were prepared from bleached ramie (Boehmeria nivea) fibres (Stucken Melchers, Germany). Small cut pieces of fibers were treated with 2% NaOH at 35 °C for 48 h in order to remove residual proteins, hemicelluloses and traces of pectin. The homogeneous suspensions obtained from washed ramie fibers were submitted to overnight hydrolysis (∼16 h) with 65% (w/w) H2SO4 at 35 °C under stirring. The suspensions were washed with water until neutrality and dialysed with 6000 cut-off regenerated cellulose membrane. The resulting colloidal cellulose nanocrystal suspensions were stored at 4 °C and were sonicated with a Sonics vibra-cell (750W, Fisher-Bioblock) with appropriate concentration for a few minutes before use. The average crystal dimensions were measured from AFM image analysis with ImageJ (Fig. 1). CN is 99% pure glucose and 0.7% ± 0.1 sulfur, as estimated by elementary analysis of the dry matter corresponding to the average surface charge of 0.4 charge.nm−2.

AFM image of cellulose nanocristals from aqueous suspension and their average crystal dimensions.

2.1.2 Lignin compounds

Lignin model compound (DHP) was synthesised according to the classical “Zutropfverbaten” method consisting of a slow and continuous addition of coniferyl alcohol (4-hydroxy-3-methoxy-cinnamyl alcohol) and hydrogen peroxide to a solution of peroxidase according to the procedure detailed in [35]. DHP was collected at the end of the reaction by centrifugation of the suspension and the insoluble part was washed with water before freeze-drying. The weight average molecular mass (Mw) is 2775 g mol−1 with a polydispersity index Mw/Mn of 1.4, determined by high-performance size exclusion chromatography using the relative calibration method based on the elution of ten polystyren standards [35].

2.2 Methods

2.2.1 Adsorption isotherm measurements

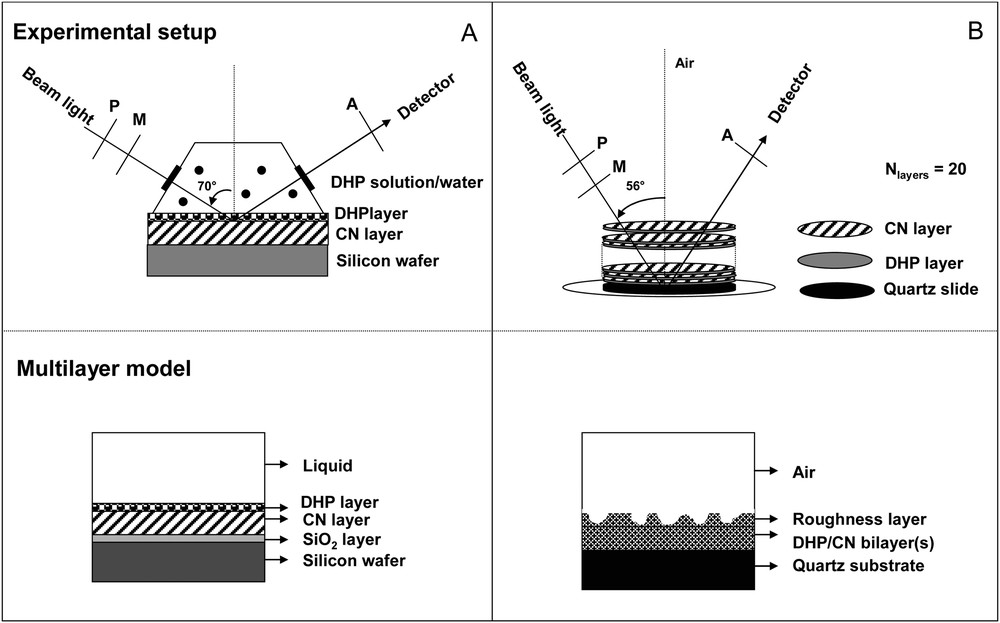

Adsorption isotherm measurements were performed at liquid/solid interface according to the experimental setup drawn in Fig. 2A. DHP was solubilized in liquid phase (dioxane/water mixture [9/1, v/v]) at bulk concentrations between 0.1 and 1.0 g/L. Solid phase was composed of cellulose nanocrystal layer prepared on silicon wafer by Langmuir-Blodgett method as described in [36]. The adsorption layer of lignin formed on cellulosic layer was observed after 6 h of contact, until the quasi-equilibrium state of the adsorption kinetics. The structure (apparent thickness [tapp] and topography) of the DHP layer formed on cellulosic layer was analysed by spectroscopic ellipsometry and AFM after washing lignin-cellulosic surface with pure water and after drying layers under N2 flux.

Schematic diagrams showing experimental setup of ellipsometric measurements at liquid/solid (A) and air/solid (B) interfaces and of the multilayer model respectively used for data fitting (for indication, the optical properties at 589 nm of silicon wafer, SiO2 layer, CN layer and quartz substrate are respectively: NSi = 3.97 – i × 0.031; NSiO2 = 1.458, thicknessSiO2 = 20 Å; NCN = 1.513; thicknessCN = 60–70 Å; Nquartz = 1.457).

2.2.2 Multilayer film preparation

Nanocomposite films were assembled on quartz slides (Suprasil, diameter 35 mm, HTL France) for UV/Visible spectroscopy or BaF2 (diameter 10 mm) for FTIR measurements. Before deposition, the quartz disk was washed with piranha solution (7:3 concentrated sulfuric acid to hydrogen peroxide mixture) for 0.5 h, then rinsed with ultrapure water 18 MΩ and dried under N2 flux. The BaF2 disks were cleaned in acetone. Cellulose nanocrystal suspensions and lignin solutions were diluted to 12 g L−1 and 1 g L−1 using ultrapure water (pH 6) and dioxane/water mixture (9:1, v/v) respectively. Each solution was alternatively deposited by spin-coating at ambient temperature on the solid substrate with a commercial spin-coater (Speedline Technologies, USA). A volume of 100 μL was deposited on a stationary quartz disk, which was then accelerated at 1260 rpm/s and spun at 3000 rpm for 40 s. Multilayered films were assembled from 1 bilayer (Lignin/CN) up to 10. After each deposition, the film was dried at 50 °C for 10 min.

2.2.3 Film characterizations

Film growth was monitored by UV/Vis absorption spectrophotometry, FTIR and spectroscopic ellipsometry at air/solid interface according to the experimental setup drawn in Fig. 2B. All spectroscopic characterizations were followed by AFM surface morphology measurements.

2.2.3.1 UV/Vis absorption spectrophotometry

UV/Vis spectra were recorded on a Shigematsu Scientific Instrument (USA) in double-beam mode, using an uncovered quartz slide as reference.

2.2.3.2 Fourier Transform InfraRed spectroscopy (FTIR)

FTIR spectra were recorded on film using a Nicolet 460 (ThermoScientific, USA) spectrophotometer by scanning 16 times in a resolution of 4 cm−1 from 833 to 4000 cm−1.

2.2.3.3 Spectroscopic ellipsometry

Ellipsometric measurements were performed using a spectroscopic phase modulated ellipsometer (UVISEL, Horiba-Jobin Yvon, Longumeau, France) as described previously [36]. Each spin-coating deposition was monitored by spectroscopic measurements recorded between 240 and 820 nm at the air/quartz interface at an incidence angle of 56°. In addition, adsorption isotherm of the lignin model compound on the cellulose nanocrystal film was determined at liquid/solid interface at an incidence angle of 70° in a specially constructed cell with quartz crystal windows at both ends fixed at an angle of 70 °C (Fig. 2). All ellipsometric experiments were done in an air-conditioned room at 20 ± 0.5 °C.

In an ellipsometric experiment, two parameters, Ψ and Δ are measured. The variation of these two ellipsometric angles is directly related to the change in the state of the polarization when a light beam is reflected in a surface: the amplitude attenuation and the phase difference before and after reflection respectively. These angles are related to the ratio of the Fresnel reflection coefficients: Rp (within the plane of reflection) and Rs (normal to the plane of reflection) [37]:

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

The interrelation between Eqs. (3) and (4) gives:

| (5) |

| (6) |

The Classical Dispersion and Tauc-Lorentz models work particularly well for transparent and absorbent materials in UV or visible range, respectively. The classical dispersion law is used as a single Lorentz oscillator dielectric function (Eq. (7)):

| (7) |

The Tauc-Lorentz model is a powerful and convenient tool which can be applied to polycrystalline and nanocrystalline thin films and allows one to parameterize the imaginary part ɛi and the real part ɛr of the dielectric function with multiple oscillators [38]. This formulation has been adopted to model the experimental ellipsometric spectra in order to derive the desired spectral refractive indices and band gaps for the composite films.

Thus, assuming such a definite sample multilayer structure for the composite thin film (Fig. 2), initial parameters like thickness, void fraction and variables of the dispersion relation (Classical or Tauc-Lorentz relations) as fitting parameters are judiciously assigned. With these initializations, the measured ellipsometric data are fitted by progressively minimizing the error function, χ2 which represents the squared difference between the measured and calculated values of the ellipsometric data (Ψ and Δ). The maximum of iteration allowed is 100 and the criteria for convergence used is δχ2 = 1 × 10−6. Using these best-fitted parameters dielectric and optical constants of thin cellulose–lignin film sample were evaluated.

Moreover, in the case of thin layers for which the thickness, tl is largely lower than the wavelength λ, the surface concentration, Γ can be estimated from the formula (8) [39]:

| (8) |

2.2.3.4 Atomic Force Microscopy

AFM investigation was performed at ambient conditions. The AFM was placed on an active vibration isolation table so that eventual external vibrations did not affect the imaging process. A scanner with a maximum scan area of 120 μm2 was used and calibrated following the standard procedures provided by Digital Instruments. The AFM setup was a dimension setup equipped with a Nanoscope V controller from Veeco. A silicon tip with a nominal resonance frequency around 320 kHz, a nominal spring constant around 40 N.m−1 and a nominal tip radius of 5 to 10 nm was used to simultaneously record height and phase images in tapping mode. High oscillation amplitudes were used to get rid of a possible effect of the adsorbed water on the surface. Scanning rates of 1 Hz or 0.5 Hz depending on the image size and a resolution of 512 × 512 data points were used. During the scans, proportional and integral gains were increased to values just below those at which the feedback started to oscillate. Images were processed only by flattening to remove background slopes. All images were processed and treated using ImageJ 1.40 g software. The samples used for AFM analysis were prepared either after adsorption of DHP on the cellulosic layer or the multilayered films that were deposited on a quartz slide.

3 Results and discussion

Prior to the construction and characterization of the nanocomposite multilayer films, the adsorption of DHP molecule on cellulose nanocrystals was studied by spectroscopic ellipsometry at water/CN layer interface followed by air/CN layer interface after drying film under N2 flux.

3.1 Adsorption of DHP on cellulose nanocristal surface

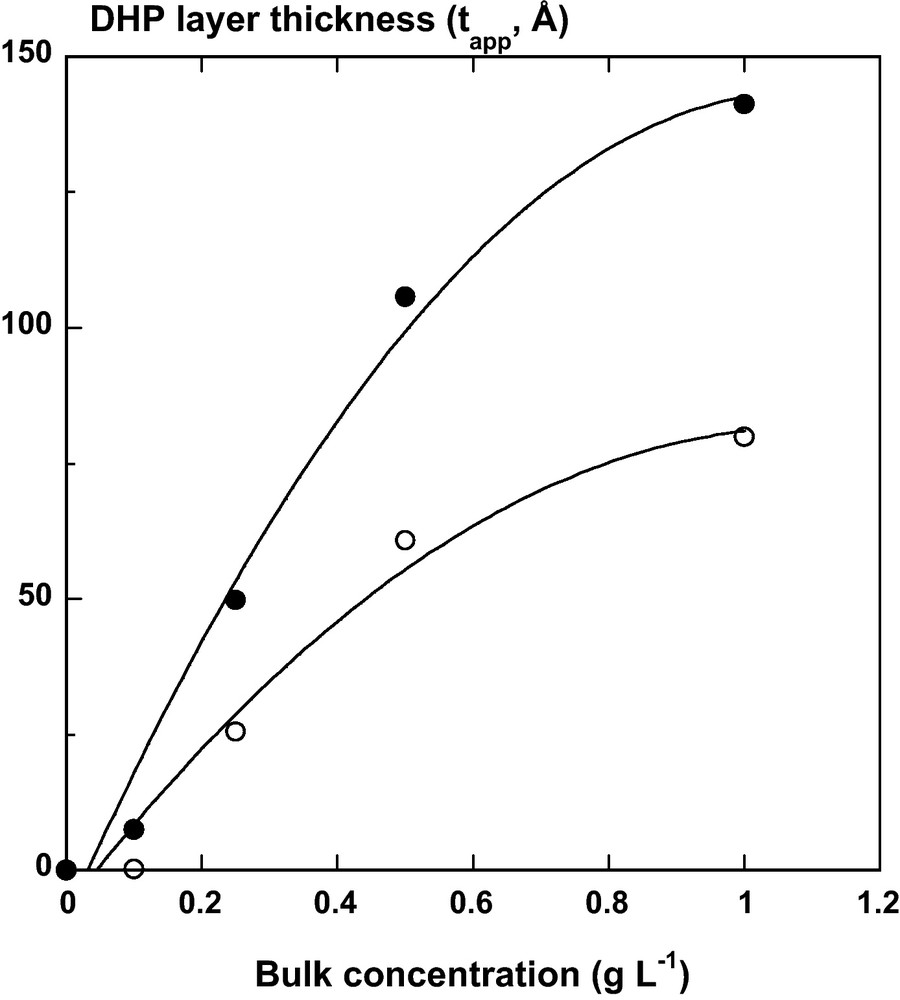

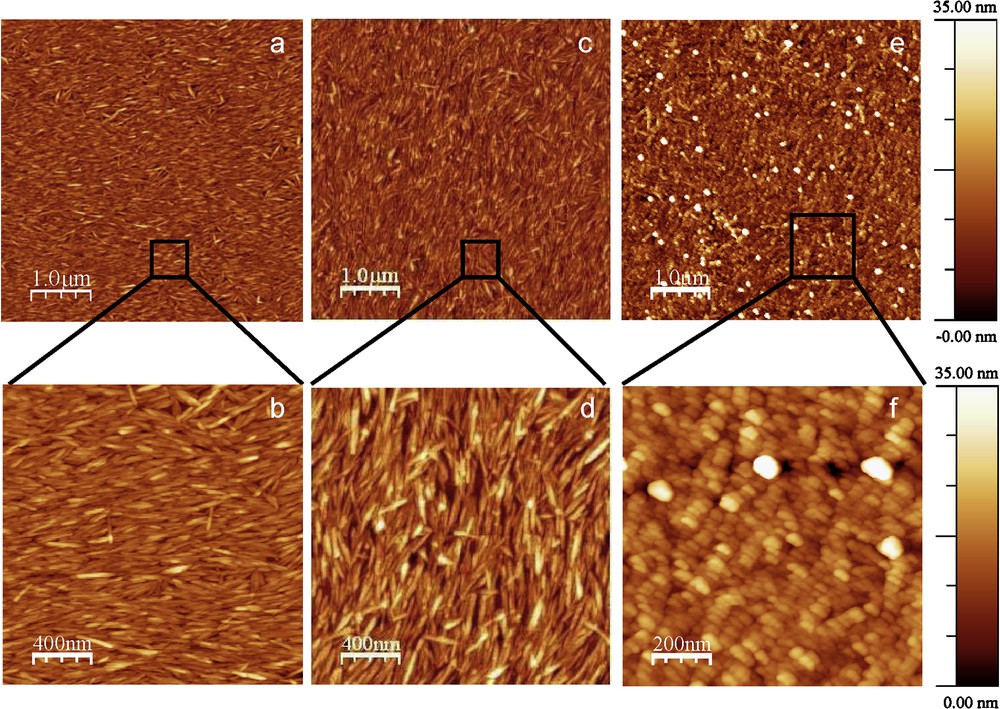

DHP–cellulose nanocristal associations were monitored at liquid/solid interface as function of the bulk concentration of aromatic compounds by spectroscopic ellipsometry. After 6 h contact, a DHP layer was formed on the cellulosic film. Before washing and drying the bilayer under N2 flux, the apparent layer thickness (tapp) of DHP with a refractive index of 1.425, increased from 7.5 ± 0.7 to 141 ± 1.4 Å with the bulk concentration of aromatic polymer (from 0 to 1 g/L) (Fig. 3). After washing with pure water and drying under N2 flux, the DHP layer was collapsed on the cellulosic film and the apparent thickness (tapp) was reduced to values ranging from 0.2 ± 0.1 to 79.9 ± 0.5 Å with a refractive index of 1.295 (mixed DHP and ambient air) for the same bulk concentration range. Analysis of AFM images showed that the topography of the free cellulose nanocrystal monolayer, and the one with a low surface coverage of DHP (Γ ∼ 0.01–0.02 mg m−2 calculated according to Eq. (8)) were very similar (Fig. 4a–d). On the contrary, at large surface coverage where Γ ∼ 6.0 ± 0.1 mg m−2, DHP formed globular structures on the cellulosic surfaces (Figs. 4e-f), as previously observed on solid surfaces [40–42]. The topography of the self-assembled DHP layer on the cellulose nanocristal film was clearly influenced by the bulk concentration of DHP. The surface roughness of the DHP layer on cellulose increased from 2.5 nm to 5.4 nm when the bulk concentration of DHP increases from 0 to 1 g/L. These globular structures ranged 30 to 40 nm in height and exhibited a typical diameter of 100 nm in diameter. Given the size of a phenylpropane monomer (11 Å × 5 Å) and the average molecular mass of DHP, one may estimate that the globules contained at least several hundreds aromatic cycles in a confined area. In these self-assembled systems, DHP polymers interact with the surface of cellulose nanocristals. According to computational studies [43,44], two main types of non-covalent interactions should be considered: (i) hydrogen bonds between the free hydroxyl groups at the surface of each nanocristal and the different lignin groups likely phenolic and alcoholic hydroxyl groups, carbonyl, or methoxyl groups; and (ii) hydrophobic interactions between the hydrophobic cristalline surface of the cellulose nanocristal (100) [45] and the aromatic cycle of the model lignin. Such interactions were strong enough to keep stable even after several washings with water. Therefore lignin is a good candidate to investigate and design cellulose nanocristals-based films varying in structural and physical properties. Consequently, we decide to build films by spin-coating deposition of alternative layers of each polymer (Fig. 2B).

DHP layer thickness (Å) after 6 hours adsorption kinetics at the liquid/CN layer () and air/CN layer () interfaces. The thickness was calculated from fitting experimental ellipsometric spectra (Ψ and Δ) using a single Lorentz oscillator dielectric function (Eq. (7)) and a fixed refractive index layer corresponding to 100% DHP (n = 1.425) and 50% DHP with 50% ambient air (n = 1.295) at liquid/solid and air/solid interfaces, respectively.

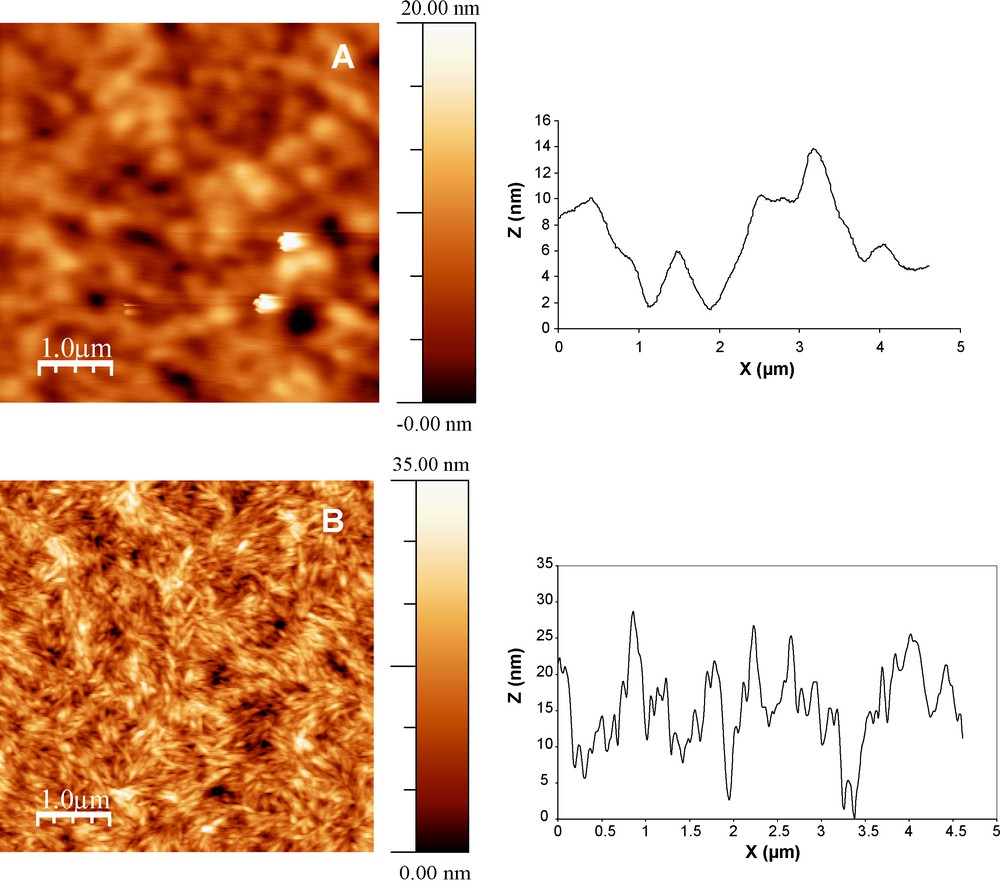

AFM tapping mode images of CN layer (a–b), DHP adsorbed on CN layer after 6 hours of contact of DHP solutions at 0.1 g L−1 (c–d) and 1 g L−1 (e–f). The rms roughness was calculated and reached 2.5 nm, 3.7 nm and 5.4 nm over 5 μm × 5 μm images from a, c and e respectively.

3.2 DHP/cellulose nanocristals multilayer films

A sequential spin-coating of DHP and cellulose nanocristals was performed ten times on quartz slide. Ellipsometry and UV-Visible spectroscopy analysis allowed to monitor the growth of the self-assembly into multilayer. Further analysis using FTIR spectroscopy and AFM were carried out.

3.2.1 Optical properties

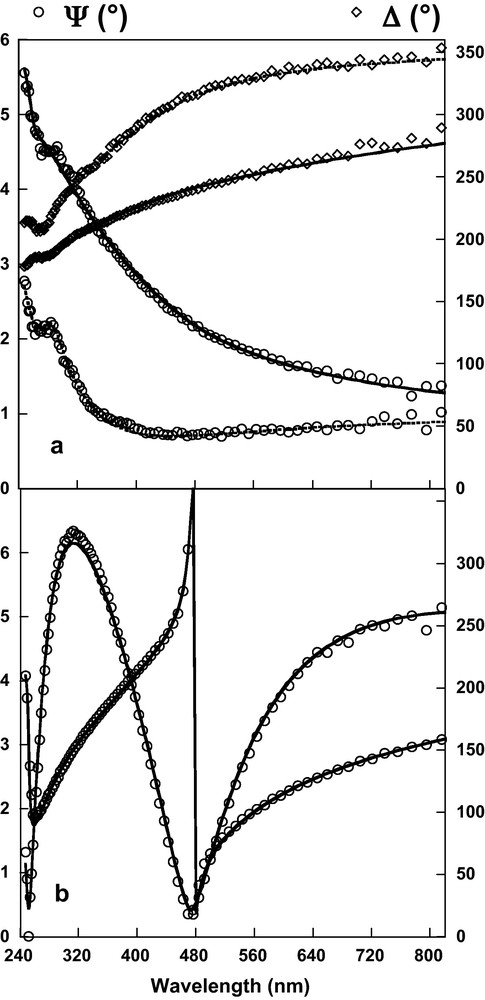

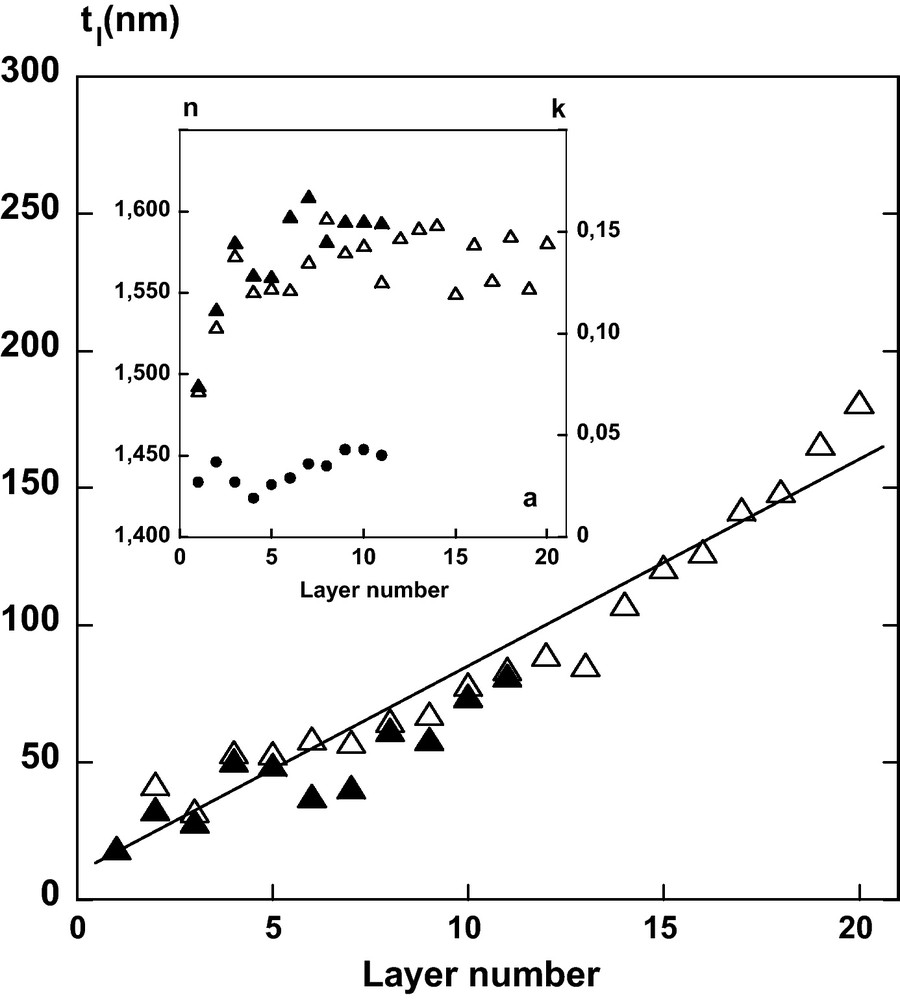

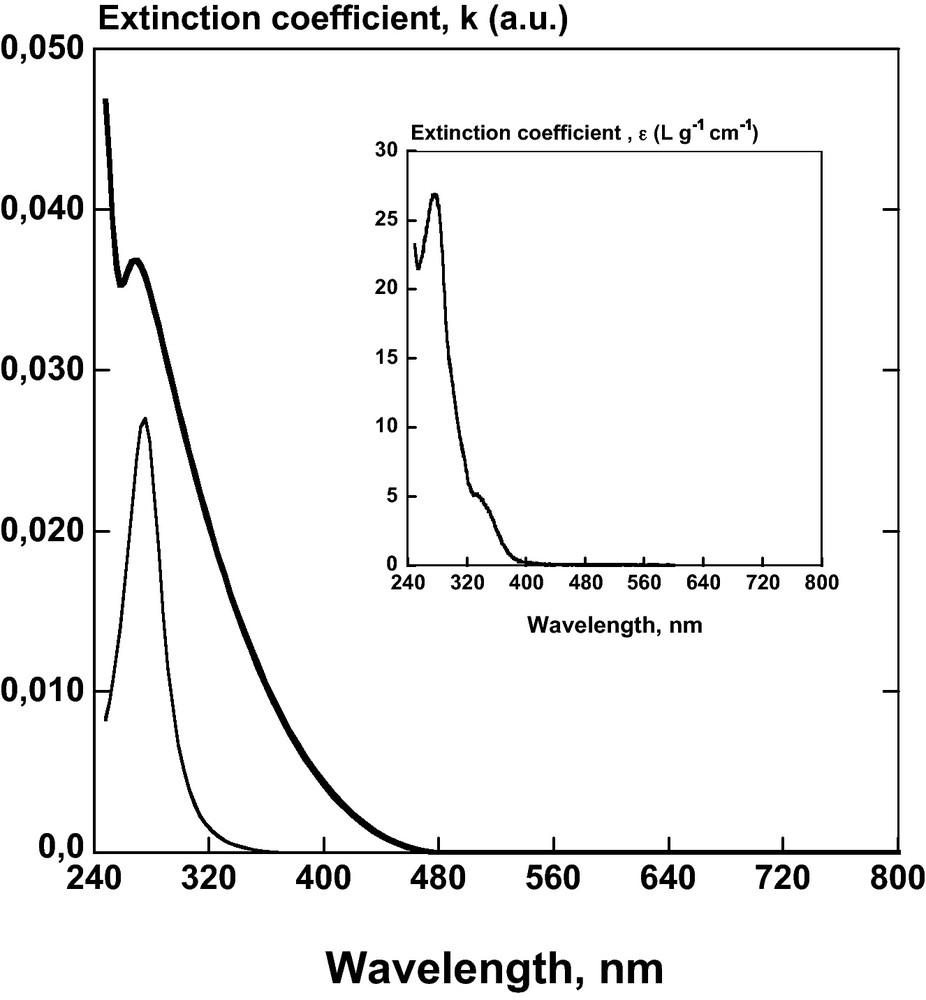

Ellipsometric measurements were performed on all alternative spin-coated layers in the center of the film with an elliptic area size of ∼2 mm2 probed by the ellipsometry beam. A polarization degree higher than 99% was measured over the entire UV/Visible spectrum, thereby confirming that the multilayer film can be considered as isotropic without depolarization effects introduced by large surface roughness or anisotropy in the film. According to [10], in the thinner multilayer films containing less than 10 bilayers of CN/polycation (PAH) with a thickness less than 190 nm, the birefringence in the center is less than 0.01. This value is much lower than the birefringence of cellulose crystal that ranges from 0.045 to 0.062 (according to its origin) with a refractive index parallel and perpendicular to the crystal axis (1.576–1.595 and 1.527–1.534 respectively) [46]. Therefore, in order to fit the ellipsometric spectra, a standard multilayer model that included an effective layer mimicking the contribution of the surface roughness was adopted (Fig. 2). A significant change in intensity of Ψ and Δ in the wavelength range occurred with increasing the number of bilayers (DHP-CN) (Fig. 5), in agreement with the increasing film thickness after each deposit. Moreover, the variation of Ψ and Δ is not uniform for measurements recorded between 240 and 340 nm, especially for the first deposited layers (Fig. 5a). The peak near 280 nm indicates that a relatively small imaginary component of the film refractive index can lead to a measurable absorption. Thus, the experimental ellipsometric parameters (Ψ and Δ) can be fitted with Classical or Tauc-Lorentz formulations to determine parameters during the film growth: the thickness (tl), the real part of the refractive index (n) and the extinction coefficient (k) as well as the thickness (trou) and the air percentage of the roughness layer (Figs. 6 and 7). At high bilayer number (> 10), the imaginary component, k becomes negligeable over the entire wavelength range measured. Then, the analysis with the Classical dispersion law (Eq. (7)) has been applied to ellipsometric data without imaginary part (Γ0 = 0) as shown in Fig. 5b. In consequence, the fitting of the multilayer thickness (Fig. 6) demonstrates that tl is linearly related to the number of deposited layers on quartz slide from 10 to 180 nm. The contineous line is a linear fit of the data, which indicates a thickness contribution of about 14 nm/bilayer. This result is influenced by the complex refractive index (Fig. 6) and the roughness. Fitting the real part of the refractive index led to a value at sodium ray (589 nm) from n = 1.49 for the first bilayer to 1.585 ± 0.005 for the following ones (Fig. 6 insert). The extinction coefficient, (k versus λ) was evaluated from fitting ellipsometric data of DHP before the deposition of CN layer and showed maximum value near 275 nm (Fig. 7). This profile was similar to the absorption spectrum of DHP solubilised in dioxane/water (9/1, v/v) (Fig. 7). The maximum value of k at 277 nm is attributed to the nonconjugated phenolic groups in DHP molecule [31]. Nevertheless, the deposition of successive bilayers did not lead to a significant increase of k value with increasing film thickness. Instead, this maximum got almost constant values: 0.033 ± 0.008 (Figs. 6 and 7). The thickness of the roughness layer (trou) with a refractive index of 1.286 ± 0.008, increased from 0 to 6 nm for all samples with N > 10.

Experimental (symbols) and simulated (line) ellipsometric spectra of DHP/CN assembly spin-coated on a quartz substrate. (a) ---- DHP layer; — DHP/CN bilayer with Tauc-Lorentz formulation [38] (b) — 10 bilayers of DHP/CN with single Lorentz oscillator law (Eq. (7)).

Film thickness (tl, nm) versus number of sequential spin-coated DHP and CN layers. Insert: evolution of the real, n and imaginary, k parts of the refractive index at 589 nm of the film after each deposition as evaluated from fitting with one single Lorentz oscillator (Δ) or Tauc-Lorentz (n: ; k: ) formulations.

Extinction coefficient, k (a.u.) evaluated from fitting ellipsometric data with Tauc-Lorentz formulation of pure DHP layer (—) and of the DHP/CN bilayer () versus UV/Visible wavelength range. Insert: comparison with the extinction coefficient spectra of DHP solution, ɛ (L g−1 cm−1) in dioxane/water (9/1, v/v).

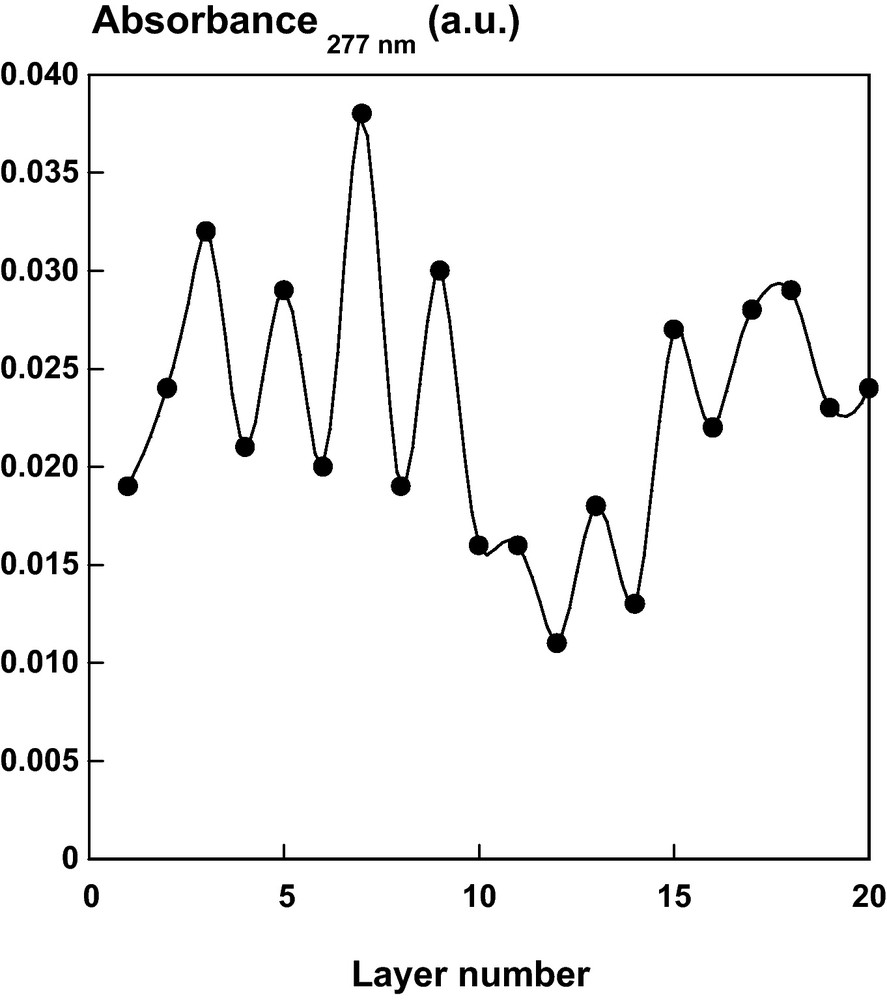

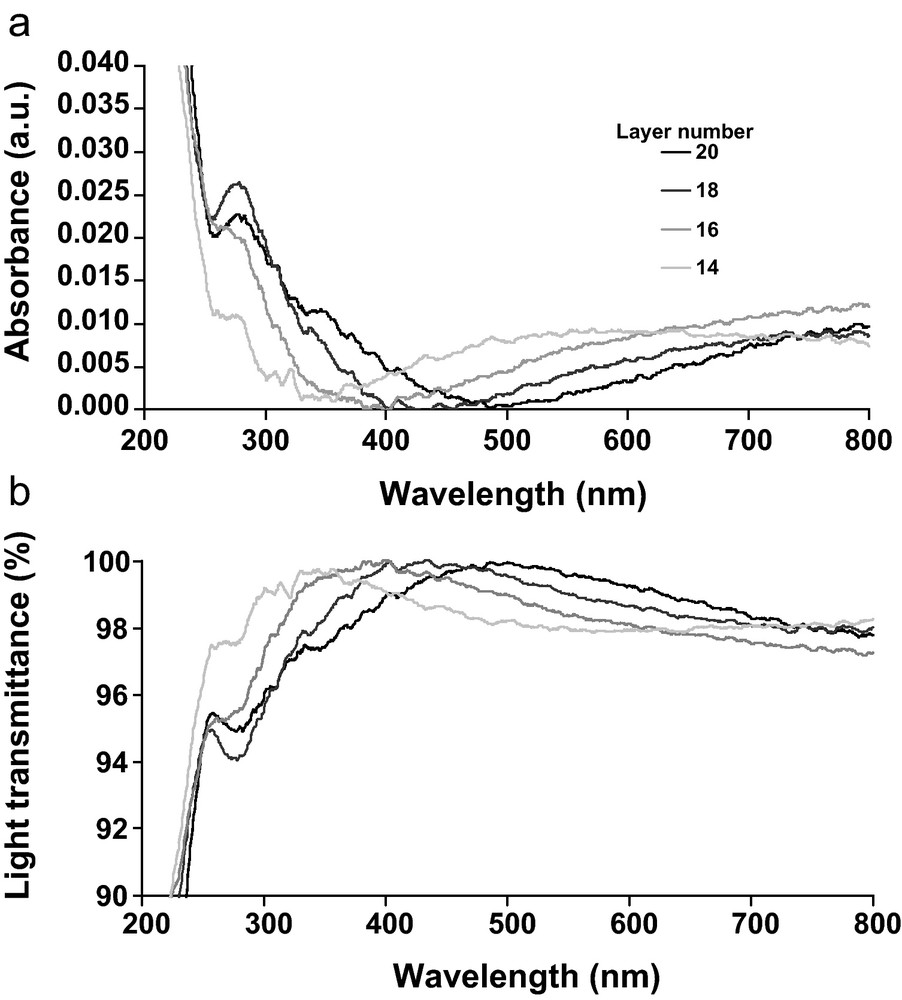

3.2.2 Spectroscopic properties in UV and IR wavelength ranges

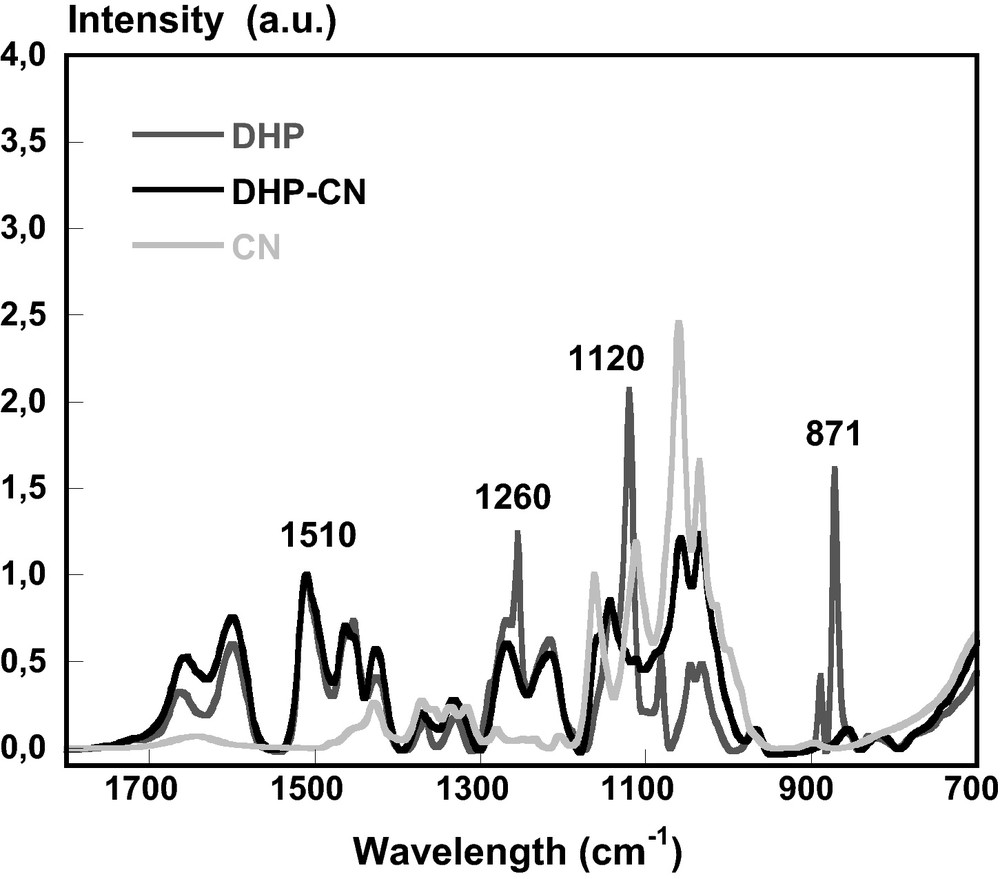

The nanocomposite film was further observed in UV/Visible and characterized by FTIR spectroscopy (Figs. 8 and 9). In the UV wavelength range, the absorption value at the maximum wavelength (277 nm) varied between 0.015 and 0.035 and increased after each deposition of DHP (Fig. 8). On the contrary, the absorption decreased after each deposition of CN. Moreover, the deposition of CN on the DHP layer caused the disappearance of DHP bands at 871, 1120 and 1260 cm−1 observed by FTIR (Fig. 9). These peaks have been assigned to the δC-H (out of plane) and δC-H (in plane) bending in aromatic rings of DHP respectively [47].

Absorbance at 277 nm of a DHP/CN multilayer film on quartz slide as a function of layer number.

FTIR spectra of DHP (), CN () and DHP-CN () superposed layer. Each film was prepapred by solution casting on BaF2 slide.

A hypochromic effect with no shift of λmax in the UV and IR spectra was observed when cellulose layer was spread on DHP layer. This phenomenon can be related to the type of DHP self-aggregation on cellulose layer, or to the moderate dispersion of the effective field of the light wave in non contineous media such as the CN layer. In the nanocomposite film, DHP polymer formed aggregates as observed in AFM image (Fig. 10A) and could act as an “adhesive” between CN layers. Thus, in the first hypothesis, the UV absorption of each chromophore should depend on the absorption by the other ones due to shielding and/or intramolecular interactions. When interchromophore distance is comparable with chromophore size (much lower than the wavelength), one light wave covers many chromophores. This creates the conditions for competition for the given incident proton which leads to a decrease in the extinction coefficient [48]. In the second hypothesis, cellulosic layer in the multilayer film revealed generally porous structure with a rms roughness of 5 nm approximatively and some minor orientational order (Fig. 10B). This layer would behave as an optic filter which screens the specific absorption of lignin in UV and IR (Figs. 8 and 9, respectively).

AFM tapping mode images and height profiles (nm) of multilayer assemblies on quartz slide after coating DHP, Nlayer = 19 (A) and CN, Nlayer = 20 (B). The rms roughness was calculated and reached 2.5 nm over 5 μm × 5 μm image (A insert) and 5.2 nm over 5 μm × 5 μm image (B).

3.2.3 Spectroscopic properties in visible wavelength range

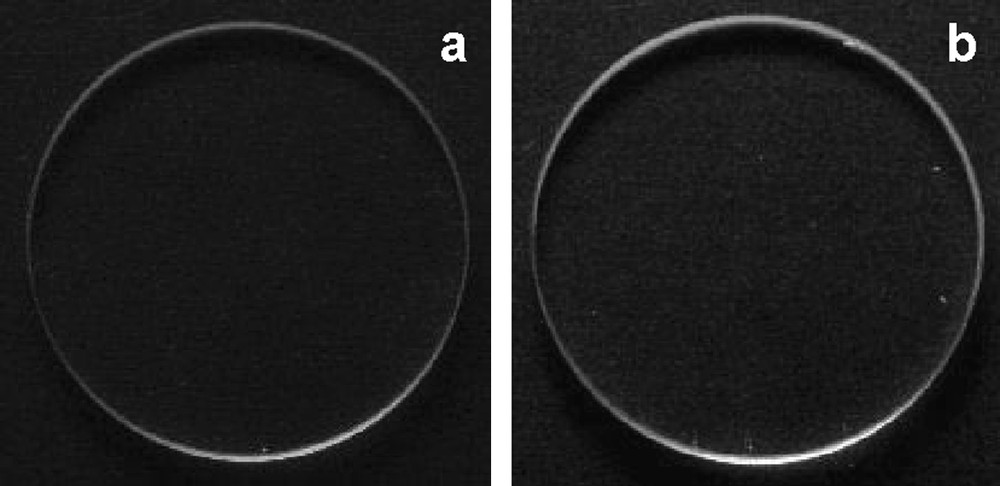

The nanoporous film was indeed highly transparent (Fig. 11). Moreover, three principal conditions of antireflection coating were satisfied: (1) a multilayer system; (2) the wavelength of the maximum transmittance, λTmax is in accordance to the wavelength of zero reflexion observed on ellipsometric spectra (Fig. 12 and Table 1); (3) the optical thickness of the total film is close to λTmax/4 (Table 1). The fourth condition involving that the index of refraction of the film is equal to nf = (nans)1/2 where nf, na and ns are refractive indices of the multilayer film, air and quartz slide, respectively, is more difficult to satisfy. Only the layer that displayed thickness of trou ∼ 5 nm led to a reduction of the refractive index to ∼1.3. Size and spacing of pores observed by AFM could imply diffuse scattering of the incident light in the film [49]. They are smaller than the wavelength of light, consequently, according to Ibn-Elhaj and Schadt [50], no light scattering occurs. Nevertheless, the calculation of the void fraction in the isotropic film from ellipsometric data was not easy to control. Air (n ≈ 1) persisting within the pores could be partially replaced by water (n ≈ 1.33) because the nanoporous materials were exposed to ambient air with 50% of relative humidity. Consequently, the low contrast between the refractive index of DHP layer, of CN layer and of void in the multilayer implied the use of a simple model for fitting ellipsometric data, which average the refractive index of the film to 1.584 ± 0.005 (Fig. 6). Nevertheless, this last observation does not modify the accordance between the λTmax and zero reflection like the λTmax/4 and thickness of the film for AR coating.

Photographies of quartz slides uncoated (a) and coated with 10 bilayers of DHP/CN (b).

Absorbance (a) and transmittance (b) spectra of the DHP/CN multilayer film on quartz slide, in UV/Visible wavelength range for the four last bilayers.

Optical properties of the multilayer DHP/CN film.

| Layer number | λ(T > 90%) (nm) | λTmax (nm) | λ (R∼ 0) (nm) | t1 (nm) | trou (nm) | λTmax/4 (nm) |

| 14 | 291–403 | 350 | 287 ± 2 | 108 ± 1 | 6 ± 0.4 | 87.5 |

| 16 | 323–499 | 400 | 342 ± 2 | 127 ± 0.2 | 4 ± 0.1 | 100 |

| 18 | 350–632 | 450 | 395 ± 2 | 149 ± 0.1 | 5 ± 0.1 | 112 |

| 20 | 370–800 | 500 | 475 ± 2 | 181 ± 0.3 | 6 ± 0.2 | 125 |

In conclusion, the transparency and antireflective properties were associated to the porous structure of the multilayer film and could be obtained using shorter cellulose nanorods (length of ∼135 nm) than previous study reporting on the use of some μm length nanorods [4]. The construction of antireflective multilayer assembly using short length CN can be permitted by the spin-coating technique which forces the nanocristal to adopt a 2D-orientation in the layer as previously observed in layer-by-layer CN assemblies [4]. The current results indicate that the challenge for fabrication of AR coatings from CN and lignin may be met by fine-tuning the surface roughness and internal structure.

4 Conclusions

Thin multilayed film incorporating lignin model compound (DHP) layers and nanocrystalline cellulose layers were prepared by the spin-coating methodology. This technique gave transparent and antireflective film properties, as confirmed by AFM surface morphology measurements, absorbance-transmittance properties in UV-Visible wavelength range and optical properties determined from ellipsometric measurements. The affinity between these two polymers at the liquid/cellulosic film interface was evidenced before building the structured nanocomposite. DHP formed globular structures on the cellulosic surface thereby improving the adhesion of cellulosic layers. The optical properties of the nanostructured DHP/cellulose CN systems thus offers an opportunity for new application of the co-products recovered from emergent biomass industry such as second generation biofuel production. For future practical applications, both the transparent and antireflective properties should be preserved under ambient conditions. Studies aiming at improving hydrophobicity and resistance to photochemical ageing in relation to the presence of lignin are under progress.

Disclosure of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest concerning this article.

Acknowledgment

We acknowledge the financial help supported in part by the Conseil régional Champagne-Ardennes. We thank C. Eypert and M. Schakowsky (Horiba-Jobin Yvon, France) for discussions concerning ellipsometric data.