1 Introduction

The adult male babirusa (genus Babyrousa), a wild pig endemic to the Indonesian island of Sulawesi and neighbouring smaller islands, has large canine teeth, with the upper (maxillary) teeth piercing through the skin of the nose and curling over the front of the face [1]. The histology of these continually growing canine teeth has been described [2] and the absence of an enamel outer layer highlighted [3,4]. The pattern of growth and eruption through the nose of the maxillary canine teeth has recently been described [5].

The function of the babirusa's canine teeth has long been a puzzle [4,6]. MacKinnon [7] studied a collection of 24 skulls and noted various patterns of abrasive wear on these teeth. He formulated the hypothesis that the teeth had been sharpened by specific “intraspecific fighting”, and that this behaviour was the cause of damage to the teeth. This “intraspecific fighting” suggestion was then diagrammatically illustrated [8]. Several studies of the behaviour of babirusa have since been carried out, in different zoological collections and in the forests of north Sulawesi; no evidence was found to support the hypothesis that the male babirusa uses its canine teeth in a directly agonistic way [9–11]. Indeed, ironically, it may be that in the last stages of agonistic behaviour the upper canines of the subservient male babirusa are there to protect the throat of the superior animal from the mandibular canines of the subservient animal [9]. Therefore, the question has remained; what causes the patterns of wear found on the canine teeth of the adult male babirusa?

2 Materials and methods

The anatomy of the maxillary and mandibular canine teeth was examined in 260 adult male babirusa skulls (Fig. 1; Supplementary Table 1). The written data accompanying 125 of these skulls indicated that they originated from Buru island (n = 33), the Sula island of Taliabu (n = 13), the Togian Islands (n = 9); and the island of Sulawesi, in the northern peninsula (n = 52), the central part (n = 13), and the east and the south-eastern peninsulae (n = 5); the babirusa has been extinct on the South-west peninsula of Sulawesi for some time [12]. No location data were found with the other 135 skulls, but their morphology indicated that 48 skulls were from either Buru or the Sula Islands, and 87 skulls were from Sulawesi or the Togian Islands [13,14]. The 260 specimens came from 17 museum collections in ten countries (Supplementary Table 1).

Right lateral view of the skull of an adult male babirusa from North Sulawesi (17.96). Note the smoothness of the wear on the lateral surface of the maxillary tooth, and over the sides of the maxillary teeth.

Video recordings, representing a total of 60 days (ca. 600 h) of observations of 161 adult male babirusas at two salt licks in the lowland tropical forest of North Sulawesi, were examined for behaviour that might relate to erosion of the canine teeth [10]. In addition, over a cumulative period of three months observations were made of the behaviour of approximately 15 adult male babirusas in Antwerp and Surabaya zoos.

3 Results

3.1 Skeletal observations

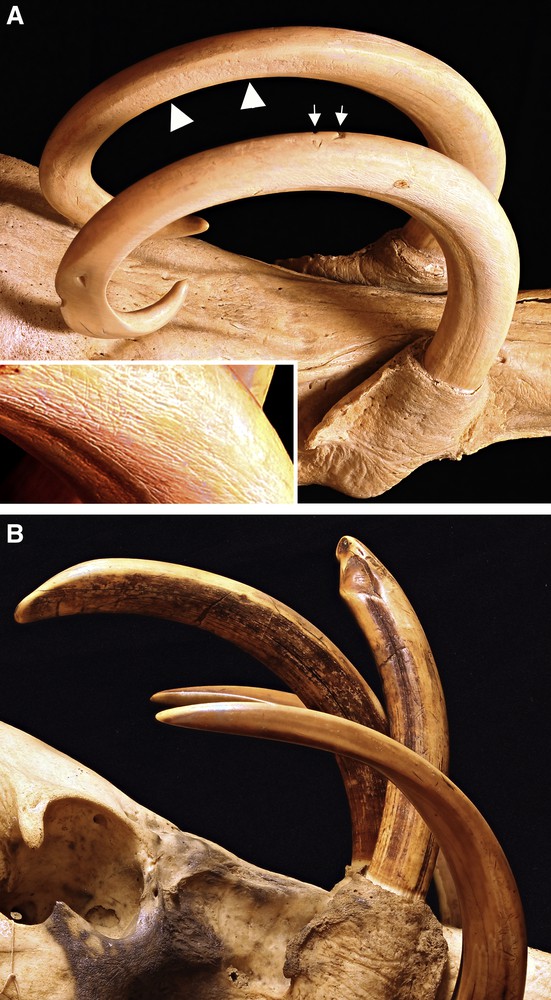

Various types of abrasive wear were found on the canine teeth of the adult male babirusa. In younger animals wear was slight; in older animals it was much more noticeable. Scratches of varying depth, length and direction (Fig. 2) appeared to be distributed randomly on the rostral, lateral and caudal surfaces of maxillary (upper) canine teeth of the skulls. They were less frequently present on the mandibular (lower) canine teeth.

A. Maxillary canine teeth (somewhat teased apart) of an adult male babirusa from Taliabu or Buru (1811). Note the shallow, somewhat parallel linear abrasions (insert enlargement) rostral to the smoothness of the wear on the lateral upper third of the right maxillary tooth. Note also the two “notched pits” (arrows) on the rostral upper part of that tooth, and the patch of rough abrasion (white triangles) on the medio-caudal aspect of the left maxillary tooth. A corresponding patch of rough abrasion lay on the medio-caudal aspect of the right maxillary tooth (not shown). B. Close-up of the canine teeth of an adult male babirusa from the North Sulawesi (17.947). Note that the maxillary canines are broken and carry deep linear abrasions. The mandibular teeth have intact tips and are smoothly “polished”.

No differences were found in the variety or patterns of this wear on the teeth of the skulls from different geographical regions. The amount of scratching and pitting (point abrasions) of the maxillary teeth (Figs. 2 and 3) on the skulls from Sulawesi and the Togian Islands was 101 of 166 skulls (61%) and on those from the Taliabu and Buru Islands it was 42 of 94 skulls (45%). Within Sulawesi itself, 36 of 52 skulls (71%) from North Sulawesi showed evidence of more than a few scratches and pits on the maxillary canine teeth; the comparable figures for Central Sulawesi were 6 of 13 skulls (46%), for East & SE Sulawesi were 3 of 5 skulls (60%), and for the Togian Islands were 5 of 9 skulls (56%).

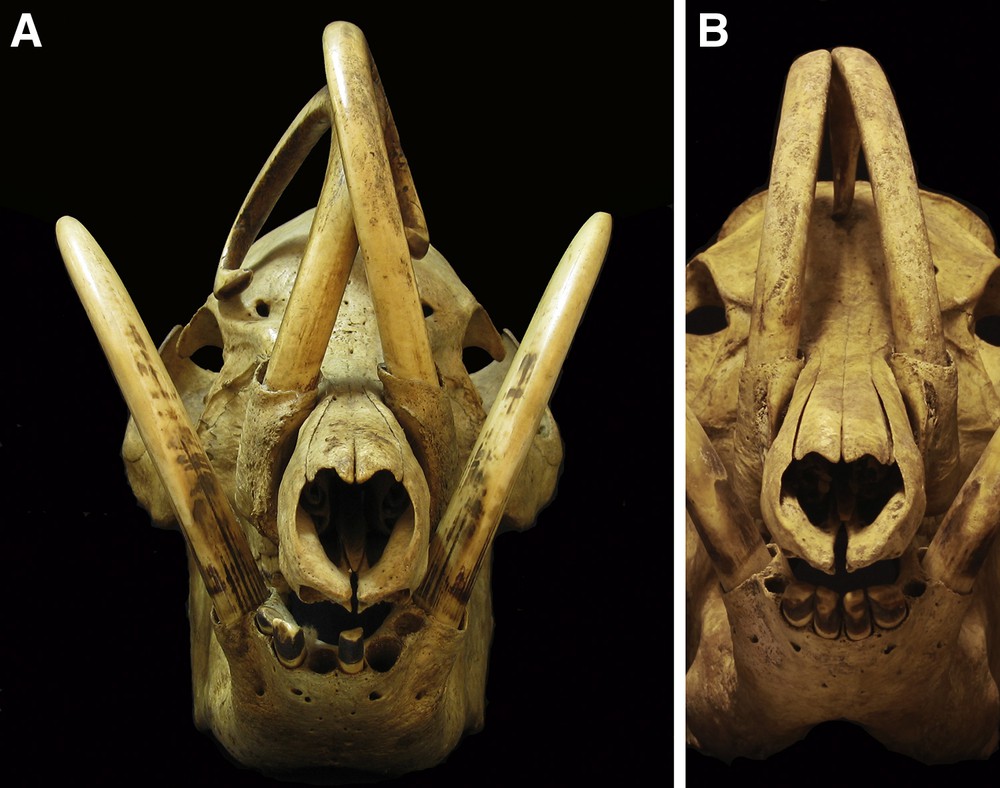

Frontal views of skulls of adult male babirusa from North Sulawesi, 7046, 17.942. A. Note the lateral erosion of the caudal aspect of the maxillary canine teeth, the smoothness of the wear on the rostral aspects of the maxillary and mandibular canine teeth, and the erosion of dentine from the distal medial aspects of the mandibular canine teeth. B. Note the medial orientation of the maxillary canine teeth and the pitting and random scratching along their lengths.

These types of tooth wear did not lead to much loss of tooth tissue. More significant losses of dentine were localised from specific regions of the tooth. With respect to the maxillary canine tooth most of this loss of tissue was from the ventro-lateral or lateral surface of the tooth, towards its distal (pointed) end (Figs. 1, 2A, 3A and 4). The tooth in this region often appeared smoothly flattened on a plane somewhat approximating to the plane formed on the side of the face by the snout, the zygion of the zygomatic bone and the zygomatic process of the frontal bone (Figs. 3A and 4). In 79 (30%) skulls the erosion of the dentine had been sufficiently severe to expose the pulp cavity (Figs. 4 and 5) and to result in the breakage of the maxillary tooth (Figs. 2B and 5). The left maxillary canine of ZMA.MAM.01856 was orientated more laterally than usual, such that it lay close to the left mandibular canine; the wear of the maxillary dentine occurs on the tooth's medial surface rather than on its lateral surface. When maxillary teeth have a more medial orientation (Fig. 3B), there is little or no erosion of the dentine on their lateral sides. A somewhat different, more “rounded polished appearance” is generally evident on the rostral surface of the maxillary canine teeth (Figs. 2B, 3A and 5).

Dorsal view of the skull of an adult male babirusa from the Sula Islands or Buru (C.2886). Note the erosion of dentine from the lateral aspect of the right maxillary canine's tip, and the medial aspect of the mandibular canines.

Lateral view of maxillary canine teeth of an adult male babirusa from Buru (429) to illustrate dentine erosion to the pulp cavity of the right canine tooth. This tooth has not been fully set back into its alveolus.

In those maxillary canine teeth where one tooth had rested against the contralateral maxillary tooth, a patch of coarse wear is present on the medial surfaces of the two teeth (Figs. 1 and 6). In one skull (C.6204) the left maxillary canine tooth had grown over the nose to the right side; its lateral surface was eroded near its alveolus on the left side and it was also eroded rostro-medially towards its tip on the right side of the face.

Rostral view (A) and right lateral view (B) of the maxillary canine teeth of adult male babirusa from Sulawesi (64,560) and East Sulawesi (17.987) respectively to illustrate the region of rough medial wear of the area of contact between the teeth.

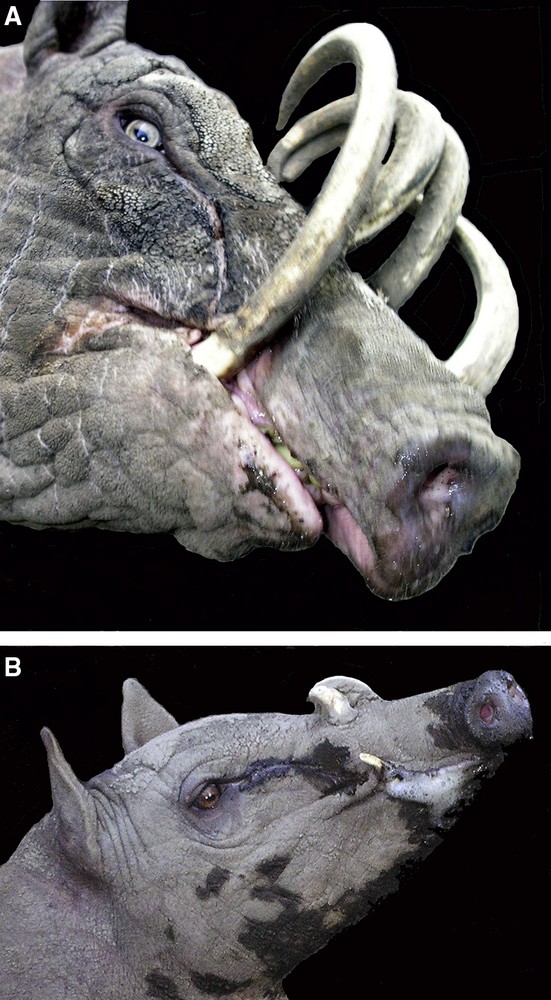

With regard to the mandibular canine tooth, the largest amount of dental erosion can be seen as a “flattened” surface that is usually situated on the medial side of the tooth (Figs. 3A and 4). A more “rounded” smoothness of the tooth is also evident rostrally and this sweeps up to and sometimes over the distal point of the tooth and onto its other surfaces (Figs. 1, 2B and 3A). When the orientation of growth of the mandibular canine teeth was more medial than the usual lateral orientation, the “flattened” erosion is on the lateral rather than on the medial side of the tooth (Fig. 7A). In one skull (47,520) the mandibular canine teeth curl over the front of the face, and the “flattened” wear pattern is concentrated on the lateral surface of these teeth.

A. Adult male babirusa illustrating his right mandibular canine tooth growing in an almost medial plane and demonstrating dental erosion of the tooth on the lateral side. The superficial pathway over the side of the face taken by eye-gland secretions is also shown. B. Young male babirusa exhibiting both eye-gland secretions and foaming saliva from the corner of his mouth.

3.2 Observations in North Sulawesi

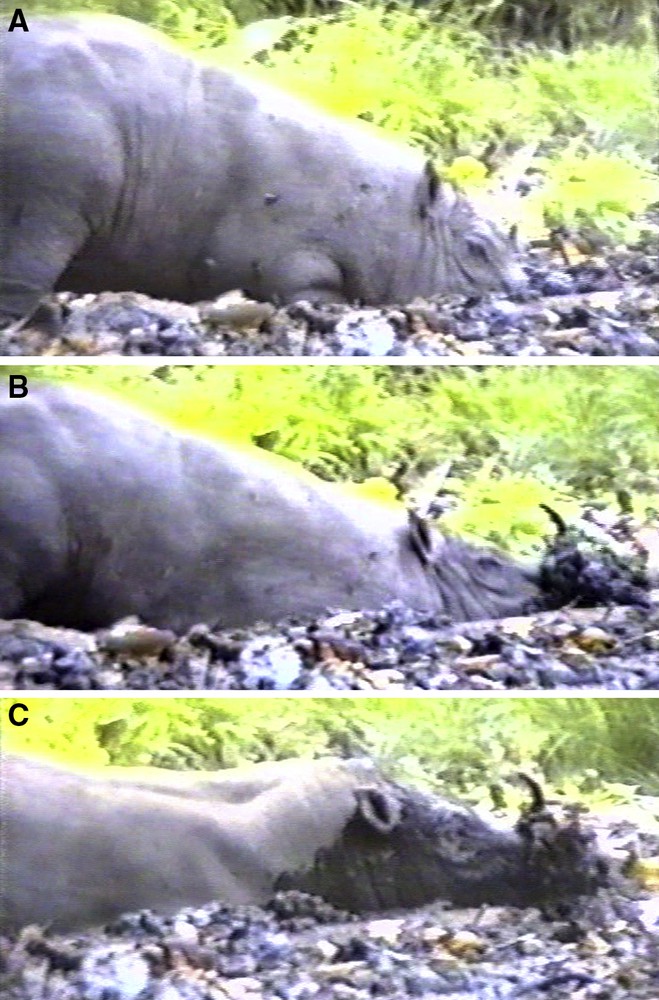

Adult male babirusa exhibited ploughing behaviour in the salt lick on six occasions (Fig. 8), and a further 37 babirusa appeared “on camera” with their heads and sides covered in wet mud, indicating recent ploughing and subsequent wallowing (Fig. 9). Erosion of the lateral surfaces of the maxillary canine teeth and the medial surfaces of the mandibular canine teeth was evident prior to ploughing and wallowing behaviour.

A, B and C. Sequences of photos illustrating an adult male babirusa “ploughing” into mud and in so doing raising a clod of wet mud onto his canine teeth.

A. The head of an adult male babirusa that has just ploughed with its face covered in the drying mud of the substrate. Note the broken canine teeth. B. The head of an adult male babirusa that has just ploughed with its face covered in the wet mud of the substrate. Note the layer of mud covering his canine teeth.

3.3 Observations in zoological collections

The maxillary canine teeth of adult males had areas of flattened wear on their lateral surfaces. Scratches were observed on these and other canine tooth surfaces. The mandibular canine teeth were usually somewhat eroded on their medial surfaces, but if the teeth were orientated in a more medial plane, then tooth wear was seen on the lateral surface (Fig. 7A). Several times each day, adult male babirusa were observed rubbing the sides of their faces against upright and horizontal fence posts, and metal fence netting, as well as on stone, concrete and brick walls. This behaviour was expressed more frequently when another adult male was in an adjacent pen or in a nearby pen. In those instances a considerable flow of liquid secretion was seen on the side of the face, rostral to and below the eye (Fig. 7A and B) and a, white frothy material was also observed around the mouth (Fig. 7B). These secretions were deposited on the surfaces of the wood, metal and other substrates against which the side of the head was rubbed. The ploughing of the nose and face into soft sand and wet muddy substrate was also exhibited, where the availability of appropriate substrate material permitted such behaviour.

4 Discussion

The smooth wear marks on the lateral surfaces of the maxillary canine teeth of adult male babirusa in zoos correspond to those seen on the skulls of museum specimens taken from the wild. Adult male babirusas are generally not penned together with other male babirusa in zoological collections, so there is no opportunity for them to show “intraspecific fighting”. In those instances where adult male babirusa were placed in the same enclosure, in none of the agonistic behaviour observed between them was there any attempt to “lock teeth together” as has been suggested [7,8]. Only one instance of such behaviour has been recorded, and that was when one of a pair of male babirusa fell on the slippery, wet floor of a zoo corridor and both sets of teeth briefly became entangled (P. Vercammen, personal communication).

The anatomy of the canine teeth of the adult male babirusa has been investigated [15,16] and X-rayed [9]. The maxillary canine tooth grows through a relatively short, bony alveolar collar that functions as its supporting structure (Figs. 1A, 2A, 2C and 3). The maxillary canine tooth has no enamel outer covering, the structure of its dentine is relatively soft [2], and it is subject to longitudinal and transverse fracture [4,17]. It wears relatively easily, as evidenced by the shallow grooves shown in the insert to Fig. 2A, the flattened areas on the lateral surface of the tooth towards the eye (Figs. 2A, 3A, 4 and 5) and the roughened areas of medial tooth wear between contralateral maxillary canines (Fig. 6). The latter is caused by the relative flexibility of the maxillary canine teeth within their sockets and their propensity to rub together when in contact and subjected to external forces.

In contrast, the alveolus of the mandibular canine tooth is situated in the molar part of the mandibular corpus (Fig. 1A) and this tooth is strongly supported by the bony structure of the mandible; it has about four times the length of bony support as the maxillary canine tooth. There is almost no movement in this tooth.

What are the maxillary canine teeth for? The female babirusas have either no maxillary canine teeth or only very small canine teeth [5]. One suggestion might be that the curved nature of the maxillary canine teeth in the adult male babirusa offers a significant measure of protection to the throat of the superior babirusa during and immediately after the ultimate stage of agonistic behaviour between adult two males. That is when they are both on their hind limbs “boxing”, and then come down onto all four feet with the submissive male placing his head under the chin of the superior male [9]. The curved shape of the maxillary canine teeth in the submissive male prevents his sharp mandibular canine teeth from gaining access to the throat of the superior male. Female babirusas are not agonistic in this manner, instead using their sharp chisel-like incisors to exert authority [9].

Adult male babirusas mark their territories [18,19]. They appear to do this when depositing secretions from their salivary and eye glands (Fig. 7) during “ploughing” into a soft or sandy substrate [18,19] and when rubbing the side of their head against structures on the ground [20]. In the current study the babirusa were observed to plough in the mud and soft ground in the salt-lick areas of North Sulawesi (Fig. 8). It was evident that this behaviour was also taking place “off camera” at other muddy locations around the salt-lick site (Fig. 9). Selmier [21] reported that babirusa made shallow, straight-line furrows in the ground. Slightly more scratching and pitting damage was noted on Sulawesi and Togian teeth than those reported for Taliabu and Buru. This is the opposite of MacKinnon's observations based on a much smaller sample of skulls [7]. It is likely that the irregular pattern of scratches and pit marks on the teeth resulted from lifting and turning over rough-edged stones, and the pitting could be caused, at least in part, by collision with stones and other hard objects while ploughing (Fig. 8). The apparently random way in which this damage is likely to have been caused, together with a lack of appropriate geological data to associate with the skeletal material, makes any regional differentiation inconclusive. The recurrent ploughing [19] and the repeated rubbing of lubricated abrasives over the rostral surfaces of both maxillary and mandibular canine teeth at the salt lick and in the forest are likely to have caused the “rounded smoothness” seen on those teeth.

Common warthogs (Phacochoerus africanus) root with their tusks in the ground (Wühl-Markieren) in a behaviour somewhat similar to that of ploughing by babirusas [22]. However, “rooting” behaviour as such, by babirusas in hard ground, has not been observed [21]. The adult male babirusa does not have a large rostral bone; only a (1–2 mm) thin 1–3 cm2 piece of calcified cartilage or bone is present to support the snout [12]. Therefore it is not equipped anatomically to show rooting behaviour.

Adult male babirusa in both Antwerp and Surabaya Zoos were observed rubbing their faces and “mouthing” the metal, wooden and concrete supports of their pens. Indeed, the presence of other males in the neighbourhood seemed to stimulate more of this type of agonistic behaviour, perhaps because the superiority of one male over another could not be “resolved” by direct animal-to-animal interaction [9]. Other aspects of this type of behaviour have been reported [19,23]. For example, Sutton [23] recounted one London Zoo babirusa's habit of rubbing “its tusks” against the keeper's legs, until they became “as polished as an ivory ornament fresh from the turner's lathe”. He did not report if any aqueous material was deposited during this behaviour. However, deposition of wet material was noted in the present study, and earlier [19].

The relative importance of the mouth versus the area rostral to the eye in these scent-marking behaviours by babirusa remains unknown. The biochemical identities of the secretions from both sets of glands in babirusa have still to be defined, although some steps in that direction have been made [19]. It was also noticeable that not only the facial skin, but also both the mandibular and maxillary canine teeth on that side of the head were rubbed against the pen supports. In Antwerp and Surabaya Zoos many of the male babirusa were housed either as individuals or with a female, and had no opportunity for “intraspecific fighting”. And so the tooth-erosion of the type shown in Figs. 2, 3, 4, 5 and 7A is most likely to be the result of head-rubbing behaviour. Trees in Sulawesi of between 3 and 10 cm in diameter had bark damage between 15 and 40 cm above the ground [7]. These observations are supported by a number of observations of adult male babirusa rubbing the sides of their faces against soil substrate, young trees, tree branches, fence posts, railings, and gate materials ([19,20], Ito personal communication). The likelihood is that the young trees, when rubbed against the face, were simultaneously rubbed against the lateral surface of the maxillary canine tooth and medial surface of the mandibular canine tooth.

The present study found no evidence of canine tooth sharpening, as suggested by MacKinnon [7]. Indeed many of these maxillary canine teeth showed a flattened and thinned structure (Figs. 2A, 3A, 4 and 5); many were broken (Figs. 2B and 5). The pattern of erosion of the mandibular canine teeth also did not appear to be directed towards the sharpening of the tips; many had rounded tips (Figs. 2B and 4).

Head-rubbing as scent-marking behaviour has also been reported in other wild pigs such as the common warthog, the bushpig (Potamochoerus larvatus) and the Eurasian wild pig (Sus scrofa) [22,24,25]. Various cranial sites for pheromone secretion have been proposed [11]. A milky secretion comes from the median angle of the eye of the bushpig may originate from the Harderian gland [24]. Alternatively, it has been suggested that in the common warthog and forest hog (Hylochoerus meinertzhageni) the infra-orbital glands may be responsible [26,27]. Further studies will be required to identify which pheromone secretions are produced by male babirusa, and for what purpose precisely.

5 Conclusions

In the adult male babirusa, most of the loss of maxillary canine dental tissue was from the ventro-lateral or lateral surface of the tooth, towards its distal end. This smooth flattening of the tooth is on a plane approximating to the plane formed on the side of the face by the snout, the zygion of the zygomatic bone and the zygomatic process of the frontal bone. The largest amount of mandibular canine dental erosion was on the medial side of that tooth, shown as a “flattened” surface. When the anatomical evidence is taken together with published information and from observations in zoos, it was concluded that face rubbing against young trees accounted for most of the flattened surface erosion of dentine from both maxillary and mandibular teeth. The more “rounded” smoothness of both teeth evident rostrally is concluded to be the result of substrate abrasion brought about by ploughing into mud and other ground. Stones in and on the ground probably caused most of the scratches and pits on the teeth.

6 Post scriptum

During this study, in 59 of the 260 specimens (23%) the maxillary canine tooth was not in the correct alveolus but was found in that of the contralateral maxillary tooth (Supplementary Fig. 1). Many of these teeth were fixed in place mechanically with pins or with glue of some sort and could not be replaced into the original alveoli. Identification of this anomaly is fairly straightforward. The pattern of clean, intra-alveolar tooth compared to the slope of the alveolar rim (Supplementary Fig. 1A) highlights a mismatch. Alternatively, the pattern of wear of the maxillary canine appearing on the medial surface (Fig. 1A and B), where nothing could have caused it, also makes these misplacements obvious.

It was also noted during this study (in skulls not reported here) that sometimes maxillary canine teeth were placed into the maxillary alveoli, and vice versa. In addition, sometimes the canine teeth that had the inventory number of the skull came from other (one or more) male babirusa.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the directors, curators and staff of the following zoological collections for giving him close access to their animals: Royal Zoological Society of Antwerp, Belgium, Ragunan zoo, Indonesia, and Surabaya zoo, Indonesia. He would also like to thank the curators and staff of the following museums for access to the babirusa skeletal material that form part of their collections: American Museum of Natural History, New York, USA; Göteborgs naturhistoriska museum, Sweden; Harvard Museum of Natural History, USA.; Museum für Naturkunde, Berlin, Germany; Museum Nationale D’histoire Naturelle Paris, France; Museum Zoologicum Bogoriense, Cibinong, Indonesia; National Museum of Natural History, Washington, USA; National Museums of Scotland, Edinburgh, Scotland; Natural History Museum, London, England; Naturalis Biodiversity Center, Leiden, The Netherlands; Naturhistorisches Museum Basel, Switzerland; Naturmuseum Senckenberg, Frankfurt Am Main, Germany; Senckenberg Naturhistorische Sammlungen Dresden, Germany; University Museum of Zoology, Cambridge, England; Zoologische Staatssammlung München, Germany; Zoologisches Museum, Universität Hamburg, Germany; Zoologisk Museum, København, Denmark. He is grateful to Darren Shaw for database support, and to the University of Edinburgh and the Balloch Trust for financial support during these studies.