1 Introduction

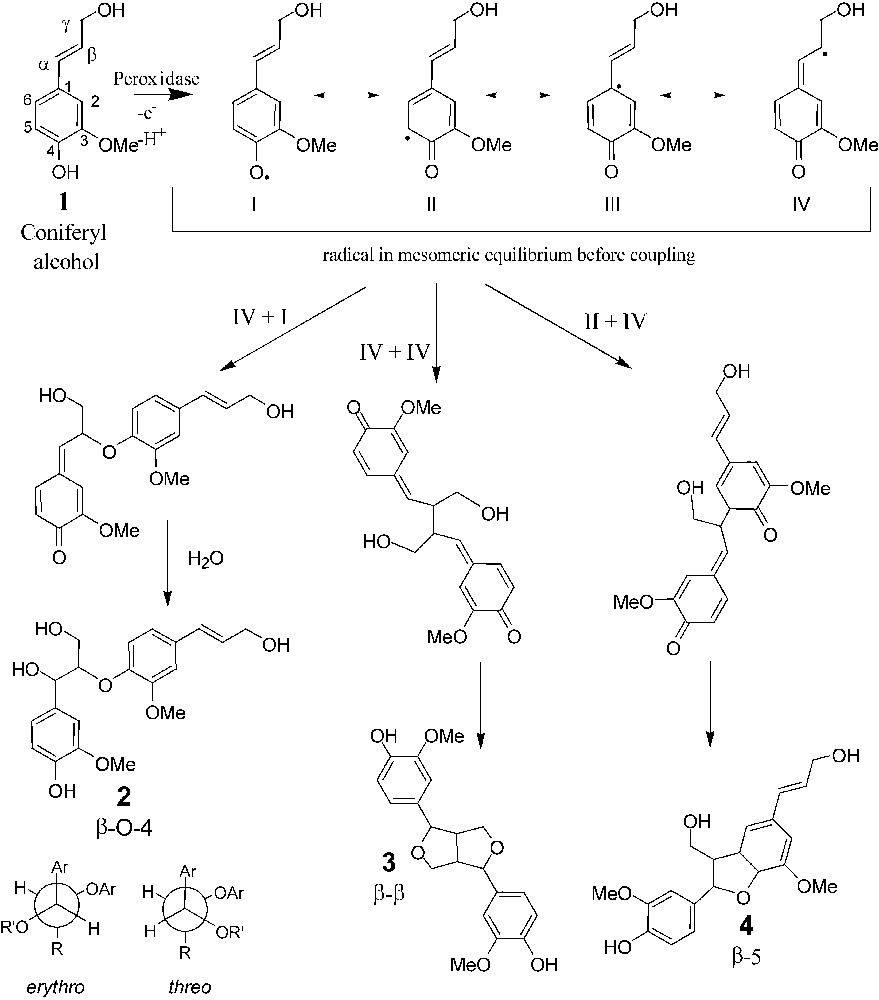

The final phase of lignin formation proceeds as an enzyme-catalysed but chemically driven mechanism influenced by the physicochemical environment of the reaction. The polymerisation involves the coupling of p-hydroxyl cinnamyl alcohol monomers (such as coniferyl alcohol) via phenoxy radicals generated upon phenol dehydrogenation (Fig. 1). These radicals are coupled in a variety of ways to build up the lignin polymer. The validity of this concept has been established by numerous in vitro studies using enzymes or oxidants to produce lignin-like synthetic molecules: the dehydrogenation polymers (DHPs). These synthetic analogues have been found to contain most of the structural units detected in natural lignin, but in very different proportions. As a consequence, the synthesis of a perfect synthetic lignin is still a challenge. This problem illustrates the difficulty to understand and reproduce the real physicochemical conditions (thermodynamic and kinetic) of the polymerisation process within the cell wall. Previous studies have emphasised several factors that may influence the monomer reactivity, such as kinetic effect, competition between dimerisation and cross coupling, specific orientation [1], template effect [2], or changes in the solvation of radicals [3]. All these assumptions are consistent with the fact that the plant cell wall is a complex, heterogeneous and dense medium. Accordingly, the understanding of the lignin biosynthesis requires the use of new polymerisation conditions in order to test the effect of complex physicochemical parameters. For instance, the hydrophilic/hydrophobic character of the cell wall polymers has been seldom taken into account. Cell-wall polysaccharides contain a large amount of hydroxyl groups and can be considered as hydrophilic substances [1], whereas lignins, built of phenyl propane subunits are rather hydrophobic. These polymers are closely associated in plant cell walls and anisotropic structures such as hydrophilic/hydrophobic interfaces can be formed. Another feature poorly taken into account is that cell wall polymers form dense and interpenetrated networks that are difficult to reproduce by model systems in solution. In order to evaluate the effect of these two parameters (local anisotropy and high local concentration) on the monolignol coupling, coniferyl alcohol was polymerised at the air/water interface, which presents the two characteristics described above. In this paper, we report the characterisation of the reaction system (i.e. the air/water interface) during the course of polymerisation. The analysis of the reaction products was also carried out. They were found to be mostly dilignols. Proportions of dilignols formed during interfacial polymerisation were compared to those formed in reference bulk conditions in order to evaluate the effect of the interface.

Dehydropolymerisation of coniferyl alcohol. Phenoxy radicals exist as four mesomeric forms that can be coupled to form dimers. β-O-4 exits as erythro and threo forms.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Experimental system

Coniferyl alcohol, synthesised as previously described [4], was solubilised at 10 mg l−1 in 17-mM phosphate buffer, pH 5.5 to form the sub-phase of the experimental system (Fig. 2). Hydrogen peroxide solution from Sigma (30% w/w in water) was deposited as small drops on the liquid surface until the amount added was equivalent to a concentration of 14.6 mM in the sub-phase. The polymerisation agent was type-VI peroxidase (Sigma, 250–330 units mg−1). It was dissolved in phosphate buffer before spreading by the procedure of Trurnit [5]. The spread quantity of enzyme used in the surface experiments (0.15 mg m−2) was equivalent to 28.8 μg l−1 in the bulk. All glass vessels were cleaned with chromosulfuric acid and rinsed thoroughly with ultra-pure water (

Schematic illustration of the experimental system. S, sub-phase,

Schematic illustration of the experimental system. S, sub-phase,

2.2 Surface pressure

The surface pressure

2.3 Ellipsometry

Ellipsometry analyses optical properties of interfacial thin layers by measuring the change of polarization between the incident and reflected beams. The ellipsometry measurements were done in an air-conditioned room at

| (1) |

| (2) |

The complex ellipticity

| (3) |

2.4 Refractive index increment

The specific refractive index increment of DHPs,

2.5 Surface concentration calculation

From the Drude equation [9] and as a first approximation, the absolute value of the Brewster ellipticity is proportional to the surface concentration. The surface concentration was also calculated from the refractive index according to the de Feijter's equation [10]:

| (4) |

| (5) |

2.6 Absorption coefficient calculation

Using the fit parameters, d and

| (6) |

2.7 Bulk polymerisation

Coniferyl alcohol, dissolved in 17-mM phosphate buffer (5 ml), pH 5.5 was added during 10 min using a peristaltic pump to a stirred solution (15 ml, final volume of the reaction 20 ml) of hydrogen peroxide (Sigma, 30% w/w in water,) and peroxidase type VI in the same concentration as in the surface experiment (

2.8 HPLC assays

HPLC was performed according to the procedure described by Wallace and Fry [14] (column Spherisorb 5ODS2, 40-min linear gradient 0–100% of water/butanol/acetic acid 98.3:1.2:0.5 to acetonitrile/butanol/acetic acid 98.3:1.2:0.5). Identification and quantification (external calibration) of coniferyl alcohol and associated dehydrodimers was done using reference compounds synthesized according to the procedure described by Okusa et al. [15] and characterized by NMR, as previously published [16].

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Dehydrogenative polymerisation of coniferyl alcohol at the air/water interface

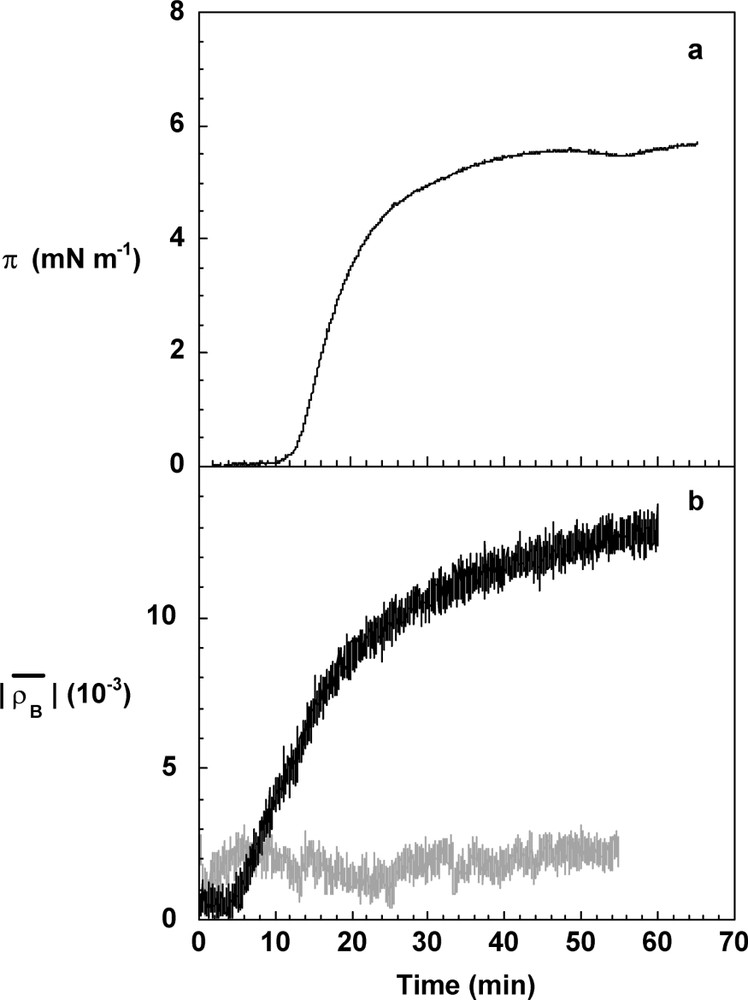

The polymerisation kinetics was simultaneously monitored by surface pressure and Brewster ellipticity measurements on the coniferyl alcohol solution where hydrogen peroxide had been deposited (Fig. 3). Surface pressure and Brewster ellipticity are two physical measurements very sensitive to any structure present at the interface. The last one becomes negative when an adsorption layer is formed at the interface and as a first approximation [9], its absolute value is proportional to the surface concentration. It was observed that the 10-mg l−1 coniferyl alcohol solution used throughout this study has no significant surface properties. Its surface pressure is null and the Brewster ellipticity has a slight positive value

Evolution of the surface pressure, π (a), and of the absolute value of the Brewster ellipticity,

Evolution of the surface pressure, π (a), and of the absolute value of the Brewster ellipticity,

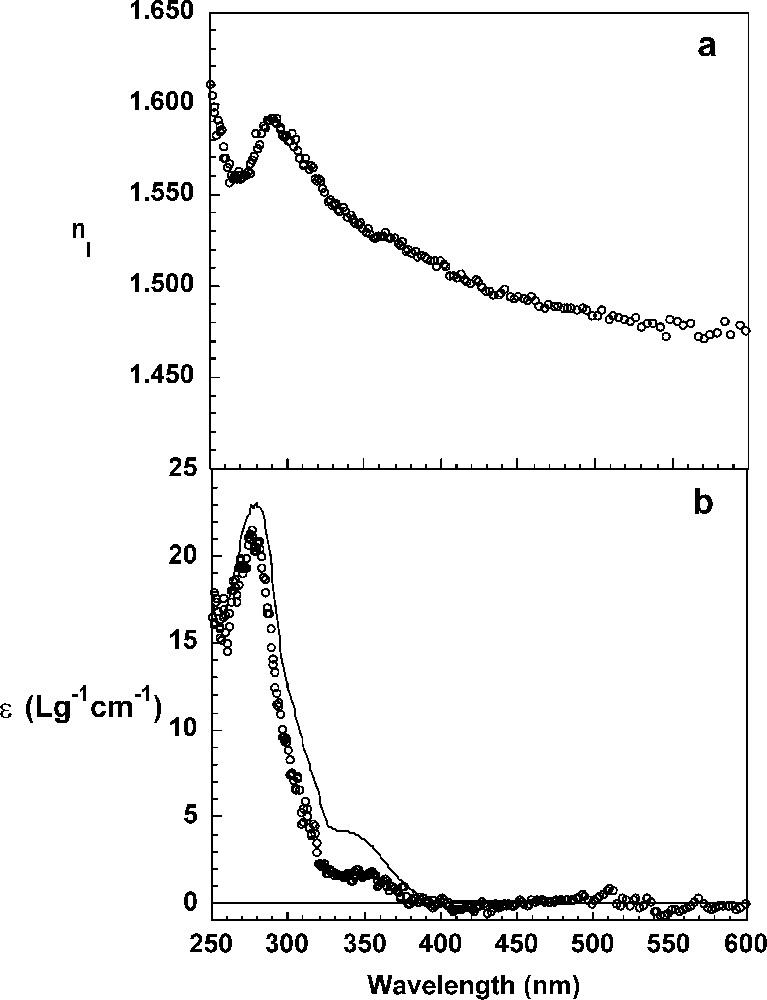

3.2 Characterisation of DHP layers

The real and imaginary parts of the refractive index and the thickness, d, of the DHP layers were determined after 60 min of reaction from the ellipsometric spectra Ψ and Δ as a function of the wavelength according to the procedure detailed before. The thickness of the DHP layer calculated by fitting a Cauchy law and a one-layer model to the data is

Refractive index,

3.3 Identification and quantification of the reaction products

After stabilization of the surface pressure (60 min), the interfacial layer was transferred by sweeping in vials containing methanol to stop the reaction and insure a good solubility of the products. A similar procedure was applied for bulk experiments. HPLC analysis of bulk and interfacial samples reveals the presence of unreacted coniferyl alcohol and dehydrodimers (dehydrogenation polymers = DHPs). Quantification of these products indicates that only a minor part of the coniferyl alcohol is incorporated in higher-molecular-weight molecules, since overall recovery yields based on the starting alcohol concentration range roughly between 75 and 85% for both bulk and interfacial polymerisation. As a consequence, it is assumed that the analysis of the dehydrodimers is representative of the reactivity of coniferyl alcohol in these experiments. Since recovery yields present similar values for all the experiments, results are presented as the relative proportion of coniferyl alcohol and of the three main dimers for an easier comparison (Fig. 5). Values are the average of seven independent experiments for interfacial polymerisation and only three different reactions for bulk process, since this latter process was found to be more reproducible.

Relative percentage of coniferyl alcohol and of the three main dimers formed in surface and bulk experiments, as determined by HPLC.

As previously reported [16], the three major reaction products are representative of the β-5, β–β and β-O-4 intermonomeric linkages, whereas 4-O-5 or 5–5 coupling modes were not detected, if they occur. This finding emphasizes the higher reactivity of the β position, as reported in the literature. The relative proportion of the three compounds agrees with previously published data [16]. β-5 Dehydrodimer is the major compound, whereas the two other molecules are formed in approximately equal amount. Results of the bulk and interfacial experiments reveal some differences. The amount of β-5 dehydrodimers is roughly 15% lower in interfacial experiments than in the bulk ones. This results in the increase of the β-O-4, β–β, and CA amounts (4, 8 and 3%, respectively). These amounts are low, but significant, since they are larger than standard errors (Fig. 5). Another difference between the two processes was also evidenced by the change observed of the threo/erythro ratio of the β-O-4 dehydrodimer. In the case of the bulk process, this ratio is equal to 0.63 in good agreement with previous studies [15] and it increases to 0.75 in interfacial polymerisation. Again, the difference between these two values is low, but statistically significant. These results can be interpreted according to two different hypotheses. In interfacial experiments, CA diffuses from the sub-phase to the surface, where it polymerises, whereas in the bulk experiments, CA is pumped into the stirred solution via a Teflon tubing. Since the addition rate of the monomers is a well-known and critical factor in lignin polymerisation, as illustrated by the difference evidenced between ‘Zulauf’ (ZL) and ‘Zutropf’ (ZT) dehydrogenopolymers [19,20], it can be hypothesized that interfacial polymerisation is a ‘Zutropf’-like process, whereas in the bulk it is a more ‘Zulauf’-type, locally at the end of the pumping tube, even though the reaction time for the interfacial reaction is somehow very short (20 min). One of the main structural differences between ZL and ZT DHP is the increase of the β-O-4 linkage content in the ZT process similarly to the increase found at the interface [19,20]. The second hypothesis is based on the fact that the reaction occurs at the air/water interface (or very close), as demonstrated in the first section. In this local environment, the physicochemical properties such as solvation are different from those observed in the bulk. It has been demonstrated that changes in polarity of the polymerisation medium induced by adding organic solvents modify the reactivity of the coniferyl alcohol [21,22]. For, instance the formation of a higher proportion of β-O-4 linkages was reported in the case of a methanol/water mixture [21]. Two arguments support the second hypothesis. The first one is related to the fact that the Zutropfverfahren process results in higher molar mass DHPs, since the monomer concentration is lower and consequently the coupling between monomers and oligomers is favoured at the expenses of dimerisation. If interfacial polymerisation was controlled by the diffusion process, the yield of the dehydrodimers should be lowered, as previously reported in the case of dialysis experiments [23]. As mentioned previously, the bulk and interfacial yields were very similar. The second feature supporting the hypothesis of the modification of the local environment is the change of the threo/erythro ratio of the β-O-4 dehydrodimer between the two synthesis methods (0.63 for bulk polymerisation and 0.75 in the interfacial process). Variation of the threo/erythro ratio has been studied and was found to be related to some physicochemical conditions of the reaction, such as pH [24,25], via the modification of the mechanism of water addition on the quinone methide (see Fig. 1). Based on this previous work, it seems that the addition rate is not a factor influencing the threo/erythro ratio and, to our knowledge, such an assumption was never reported in the literature. Accordingly, the increase in this ratio can also be understood as a local modification of the coupling environment, for instance a modification of the solvation of radicals by water, which may affect the reactivity of the quinone methide.

4 Conclusion

Polymerisation of coniferyl alcohol at the air/water interface confirms the sensitivity of coupling reaction of lignin monomers to the physicochemical environment. This emphasizes the need for understanding and characterizing the physicochemical conditions occurring in the plant cell walls during lignification. Among all the possible scientific investigations, model systems such air/water interfaces may afford some opportunities for us to understand the lignification process by changing in a simple and defined manner the polymerisation conditions. In the case of the air/water interface, this will be done by studying the polymerisation in the presence of various adsorbed molecules (surfactant, polymers...).

Acknowledgments

Thanks to N. Grozev for his contribution to a preliminary part of this work and the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs for financial support.

Vous devez vous connecter pour continuer.

S'authentifier