The term “biodiversity” has pervaded the media and politics. Terms coined by scientists have, as a rule, a precise meaning, but that meaning becomes diluted and imprecise as they become more and more popular in socio-political circles, especially as ideology becomes involved. On closer examination, however, the worm was undoubtedly in the fruit right from the start... This is what we propose to examine here. Biodiversity is now understood by everyone as a count of species, which is too reductive; by others as the “fabric of all living things”1 [1], which is too vague; or else as a synonym for “ecosystem”, which negates the need for the term. In epistemological terms, it is in fact none of the above.

The term is a neologism derived from “Biological Diversity”. It was coined in 1985 by Walter G. Rosen in preparation for a conference held in Washington in 1986, whose title mentioned the term “BioDiversity”: “The National Forum on BioDiversity”. The conference was already discussing the acceleration of species extinctions, which was perceived as a threat to our civilisation. The political dimension was therefore not entirely absent. The emergence of the word is in fact historically linked to the worldwide history of nature protection. In 1988, the XVIIIth General Assembly of the International Union for Conservation of Nature was held in Costa Rica, and it was during this event that a definition of biodiversity appeared: "Biological diversity, or biodiversity, is the variety and variability among all living organisms". It includes the genetic variability within species and populations, the variability of species and life forms, the diversity of associated species complexes and their interactions, and the diversity of ecological processes that they influence or are involved in. The term was then published in the proceedings of the symposium, edited by Edward O. Wilson, also known as the “father of biodiversity”, under the title BioDiversity in 1988 [2]. It caught on and became a central theme at the Earth Summit in Rio in 19922 .

Biodiversity is defined in Article 2 of the Convention on Biological Diversity (1992)3 as: the “variability among living organisms from all sources including, but not limited to, terrestrial, marine and other aquatic ecosystems and the ecological complexes of which they are part; this includes diversity within species, between species and of ecosystems”. According to the French Ministry for Ecological Transition4 :

“Biodiversity is the living fabric of our planet. It covers all natural environments and life forms (plants, animals, fungi, bacteria, etc.) and their interactions. It comprises three interdependent levels

- the diversity of living environments at all scales: from the oceans, meadows and forests to the contents of cells (think of the parasites that can live there), not forgetting the pond at the bottom of your garden or green spaces in cities;

- the diversity of species (including humans) that live in these environments;

- the genetic diversity of individuals within each species: in other words, we're all different!”

According to the French Office for Biodiversity5 , “Biodiversity refers to all living beings and the ecosystems in which they live. The term also includes the interactions of species with each other and with their environment”.

All these definitions share two characteristics.

First, there are indeed three levels of understanding of living beings: infra-specific, specific and supra-specific. This is the issue that gives the concept its full value: it is not enough to understand nature by counting species alone; we need to be concerned about the diversity of each species at the lower scale, and the diversity of their assemblages encountered regularly at a higher scale. In other words, we need to take into account the diversity of individuals that a species contains, at the genetic level or at other scales, bearing in mind, for example, that plants have “species” with enormous genetic diversity, whereas insects have species with much smaller amounts of genetic variation, for both biological and epistemological reasons related to taxonomic practices. In short, a plant species is not, in genetic terms, the same as an insect species. And at the other end of the spectrum, a landscape of ten square kilometres with only a rich prairie fauna and flora is less “biodiverse” than a landscape of the same size with three assemblages of prairie, grove and river species, even if the fauna and flora of each are relatively poor.

Secondly, there are two ways of assessing the situation: characterising what is there (this diversity at these three scales) and characterising the interactions. This raises the question of why the term biodiversity was coined. Because if biodiversity covers all these dimensions, we already had a concept at the end of the 1980s, that of the biosphere. However, there was a slight limitation in the scope of the terms: the biosphere is all-encompassing, whereas biodiversity can be applied locally. In short, the concept served no scientific purpose: we already had one. But it could be used politically, as a banner to signal the (real) urgency of protecting nature6 [3]. And it's fair to say that the mayonnaise caught on: the word was used far beyond the scientific sphere. In 1996, David Takacs spoke of a “political slogan” [3]. Lévêque spoke of a “loss leader” and a “Spanish inn” [4]. Delord calls it a “concept cluster” [5]. As Hervé Le Guyader points out [6], in 2000 Edward O. Wilson felt he had to specify what biodiversity is “for a scientist” [7], which means that the term was already widely used outside of science and may already be undergoing semantic dilution.

1. Current confusions

The question arises as to what kind of diversity we are talking about when we talk about biodiversity: that of organisms or that of their interactions? “Both”, ecologists tend to answer. “Not so fast”, will suggest the epistemologist: just because we consider the mosaic of species communities that make up a landscape (the third level of biodiversity) does not mean that we are necessarily interested in indentifying the various links binding these communities. The recurrence of species assemblages is what makes them distinguishable as communities. The skill of the systematist is all that is needed to characterise the assemblage. Each structuring level of reality deserves to be characterised. No one would ignore or deny the need to characterise species, subspecies and even populations, but as soon as the issue of characterising communities of species is raised, the task is seen as a study of interactions, thereby obscuring compositional characterisation. However, whether an ecologist or a systematist is characterising communities in a landscape, the question is one of systematics, not of ecology: we continue to describe what is there, and the spatial segregation of entities does not change that. The issue here is not functional relationships, but a relatively perennial compartmentalisation of living things, which is recurrently found. Furthermore, the use by ecologists of concepts of systematics to characterise communities of species does not mean that they are asking questions about systematics, or that ecology includes systematics. Twenty-five years ago, the French Académie des sciences produced a report on the state of systematics in France [8], which discussed the scientific autonomy of the discipline. This report addressed the confusion between being a user of systematics—almost any profession in contact with living organisms—and being a systematist, i.e. a scientist who conducts research in systematics.

Moreover, the definition of biodiversity dates back to the late 1980s, when geno-centrism was in full swing. Intraspecific diversity could only be genetic. And this is still what is taught today. All exhibitions on the subject speak of infraspecific diversity only in genetic terms, as do our ministries7 , or Wikipédia8 , for example. Yet explanations of the variability observed in the living world no longer focus exclusively on the gene, but also on the organism. Variations can exist, and sometimes be passed on through mechanisms beyond the gene, such as accidents or modulations in embryonic development [9], certain behavioural components, cultural variations [10, 11, 12], and those known as “epigenetic” variations. We are beginning to glimpse the evolutionary effects of some of these [13, 14]. Genes are still important, but we now recognise that such effects can be attributed to variations transmissible through channels other than genes, at a level of integration linked to the organism. In short, it is important today to bear in mind that intraspecific diversity is not just genetic, because the sources of these heritable variations are involved at several levels of integration within the organism.

The concept of Biodiversity (judged too all-encompassing by [6]) could have been scientifically useful if it had not confused everything, i.e. the study of what there is (the characterisation of diversity) and the study of what it does (the characterisation of functional interactions between living beings). This confusion is found among members of the Académie des sciences, in the collective “Libres points de vue d'Académiciens sur la biodiversité” [15]. When two academics were asked “What is biodiversity?”, one did not include interactions in the definition, while the other did [15, p. 6]: “Biodiversity is therefore all the diversity of living organisms, broadly structured into genetic diversity, species diversity, diversity of forms, functions and interactions”. When four academicians were asked the question “Does the study of biodiversity only concern the census of living species?”, two academicians maintained a clearly systematic epistemology, while the other two subordinated biodiversity to the ecosystem and its study to the study of interactions, e.g. on p. 7 : “But a simple inventory of living species would only give a very partial understanding of the diversity of the functioning of living organisms. Each individual interacts with members of its own species within a population, each species with other species; all these species use resources and recycle matter and energy within larger ecological systems, the ecosystems”; or p. 11: “The study of biodiversity cannot be limited to a census of living species (...) it must also make it possible to specify the role of biodiversity in the functioning and dynamics of ecosystems, for example with regard to their productivity and stability in the face of disturbances of varying degrees of severity (...) Nevertheless, the study of biodiversity cannot be developed without a census which, it must be acknowledged, is still only partial”. This last opinion generously grants biodiversity the only analytical prism that, in my opinion, can give meaning to the concept. Within the same ideological framework, and probably unconsciously, the INPN's definition of biodiversity9 refers to the study of functioning as an improvement (the description of living organisms remains behind, relegated to an already completed task): “Today, we are still studying the components of biodiversity (inventories of ecosystems, flora and fauna), yet we are increasingly seeking to understand how it functions. We have reached a new stage in our understanding of the system, moving from its description to the study of how it works”. Systematics is an outdated science, a view echoed at the beginning of Robert Barbault's book [1], as discussed in [16]. As a result, confusion now exists about the respective uses of the terms “biodiversity” and “ecosystem”, which have become virtually interchangeable in the general public's usage.

To overcome these confusions, the ecosystem must remain what is examined when documenting the interactions between species in a given environment, or between these species and the abiotic environment, regardless of the scale considered. Since these interactions are part of the definition of biodiversity, either “ecosystem” and “biodiversity” are synonymous, or “ecosystem” is a subset of “biodiversity”. However, it is difficult to see how the latter option could be possible. Indeed, if “ecosystem” is only a subset of “biodiversity”, there must be entities that come under the heading of biodiversity that cannot be understood through the prism of the ecosystem. This is impossible, because there are no living beings that are not in relationship with others. Therefore, introducing interactions into the definition of biodiversity (at its third level) makes the concepts of ecosystem and biodiversity superimposable, and renders the concept of biodiversity useless. There is no need to look for a distinction in the first two levels: we know of no specific diversity that is not part of an ecosystem; we know of no individual conspecific organisms that are not part of an ecosystem.

2. Systematics and taxonomy deal with what is there, ecology with what it does

For biodiversity to be a scientifically operational concept, interactions must not be included, which are then reserved for the ecosystem. If we do not include interactions in the definition of biodiversity, the ecosystem is no longer synonymous with it, but this does not diminish its significance: it remains what constitutes the interactions between organisms among themselves (biocenosis) on the one hand, and between organisms (biocenosis) and their environment (biotope) on the other. In short, an ecosystem is defined by what organisms do with each other and with the environment. Ecosystems are studied by ecology, geochemistry, pedology, geology, meteorology, etc. Biodiversity would then be what is examined when characterising what organisms have (their structures) and are (how we refer to them), at all scales, from the individual to the population, from the population to the species, from the species to assemblages of species. Biodiversity is then studied by systematics and taxonomy, informed by the sciences that compare and characterise structures.

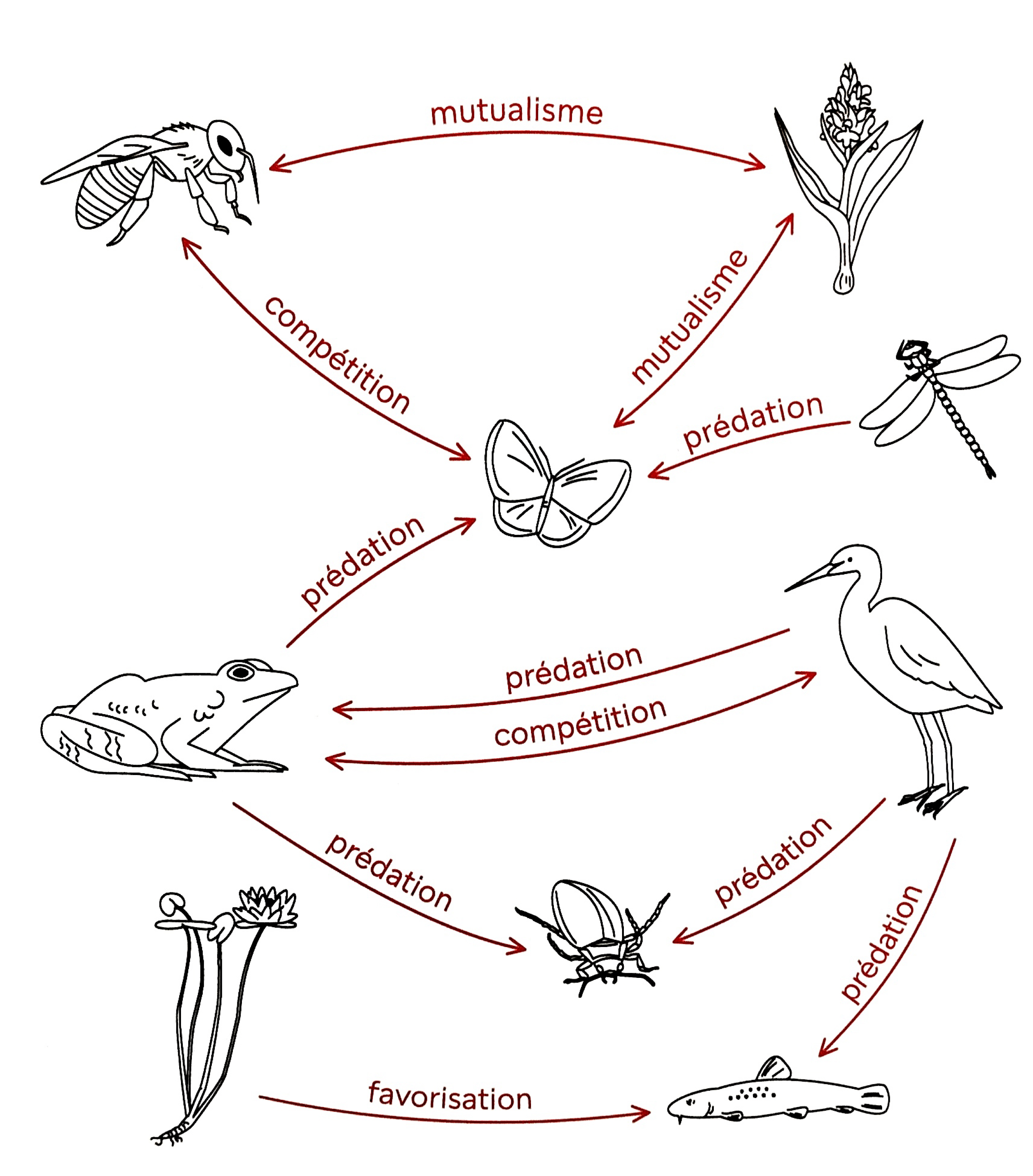

The common confusion in the use of the terms “biodiversity” and “ecosystem” is also undoubtedly due to the fact that these two modes of apprehending reality address the same entities: in the former case, the focus is on what they are; and in the latter, it is on their interactions (Figure 1). This can lead to tensions between scientists, as it does in politics: taking power or capturing resources always involves reclaiming concepts and lexicon. A political or administrative round table is indeed a strange place where all sorts of tricks are allowed when it comes to manipulating concepts, but where any rectification is forbidden for fear of drowning the meeting in a “quarrel between specialists”, a pejorative term designed to protect the ideology at work. Epistemology and politics cannot coexist on a board of directors, or even on the scientific board of any research institution. The latter manipulates the former. This should come as no surprise. When politics involves power relations, its power depends on an ideological framework that is all the more effective for having rewritten history and redefined words to suit its needs. This is undoubtedly where the term “biodiversity” comes from: a new term was needed for political reasons. Today the confusion is such that, even among scientists, words have sometimes lost their meaning. For example, the characterisation of living beings in a given environment by metabarcoding (i.e. the identification of populations and species present through the analysis of a small piece of their DNA sequences) is described as “molecular ecology”, even though the concepts and methods used actually are those of molecular systematics. Indeed, the question is what is there and how much there is in a given place, not what it does. The people involved are not even aware of this. In universities, the “molecular ecology” curriculum teaches the conceptual content of molecular systematics, not that of ecology. Moreover, taxonomy is taught in the context of ecology rather than systematics, which can lead to many inaccuracies.

An elementary distinction between biodiversity and ecosystems: biodiversity in black, ecosystems in red. © Muséum National d’Histoire naturelle.

To conclude on a positive note, biodiversity was a useful concept at the end of the 80s because it drew attention to a point of caution: measuring the diversity of living organisms should not only be done by counting species. It was also necessary to take into account the diversity within each species, which was crucial for estimating its evolutionary potential, as well as the diversity of communities in a given landscape, in other words whether the landscape was formed by a homogeneous assemblage of species or whether it was composed of packets of species that were distinct from each other. Today, to save the concept from intellectual vacuity, we need to clarify its relationship with the ecosystem, by restricting biodiversity to the exactness of its etymology: it is what is studied when the biological diversity of what there is at all levels is examined. Walter G. Rosen has removed “logical” in the expression “Biological diversity”. But logic ought to come back.

Declaration of interests

The author does not work for, advise, own shares in, or receive funds from any organization that could benefit from this article, and has declared no affiliations other than his research institution.

1 https://biodiversite.gouv.fr/la-biodiversite-cest-quoi (accessed on 8 October 2024).

2 http://www.un.org/french/events/rio92/rio-fp.htm (accessed on 8 October 2024).

3 https://www.cbd.int/doc/legal/cbd-fr.pdf (accessed on 8 October 2024).

4 https://biodiversite.gouv.fr/la-biodiversite-cest-quoi (accessed on 8 October 2024).

5 https://www.ofb.gouv.fr/quest-ce-que-la-biodiversite (accessed on 8 October 2024).

6 https://reporterre.net/Baptiste-Lanaspeze-Le-concept-de-biodiversite-est-artificiel (accessed on 8 October 2024).

7 https://biodiversite.gouv.fr/la-biodiversite-cest-quoi (accessed on 8 October 2024).

8 https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Biodiversit%C3%A9 (accessed on 3 September 3, 2024).

9 https://inpn.mnhn.fr/informations/biodiversite/definition (accessed on 8 October 2024).

CC-BY 4.0

CC-BY 4.0