1 Introduction

Substituted thiazolidines Cys(ΨR,R'Pro) are efficient tools to constrain the prolyl peptide bond into a well-defined conformation. In fact, within the heterocyclic system, the conformation preference is essentially driven by the number and the steric requirements of the 2-C substituents which destabilize one of the two conformers. Especially, the 2,2-dimethylated derivative Cys(ΨMe,MePro) can induce up to 100% of cis conformation in the preceding peptide bond [1,2]. In addition to be involved in protein folding, several studies have recently suggested that the cis proline form could be the bioactive conformation in some recognition processes [3–6]. To evidence this active form, the Cys(ΨMe,MePro) analog is an invaluable tool and has been incorporated in model peptides and in peptides involved in biologically relevant recognition processes [7,8].

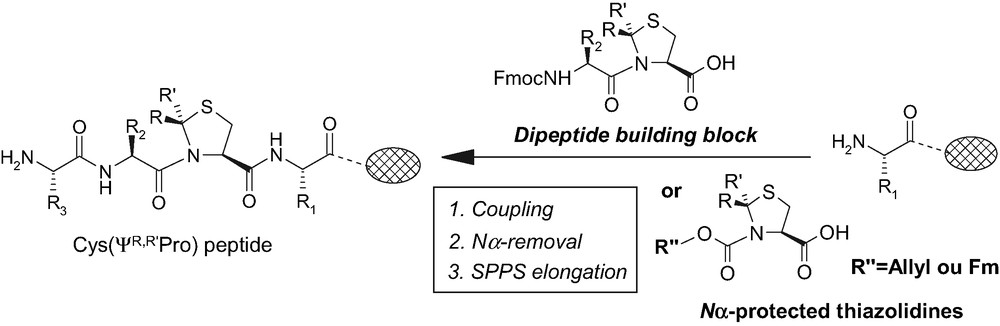

Currently, the typical way to introduce a thiazolidine residue in a peptide sequence is to incorporate it as preformed dipeptide building block [9] during the elongation of the peptide on the solid support (Fig. 1). Despite the efficiency of this method, the synthesis of the corresponding dipeptide unit in solution, FmocXaaCys(ΨR,R'pro), is mandatory that prevents the generalization of the approach. More recently, the insertion of thiazolidine systems into Ser-peptides has been investigated [10,11]. But the procedure has only been proved on a dipeptide and in the case of the cyclosporine A analog the yield remains very low.

Strategies to incorpore Cys(ΨR,R'pro) in a peptide sequence.

Herein, we have investigated a most convenient strategy using Nα-protected thiazolidines (Fig. 1) as standard amino acids in a SPPS procedure (solid phase peptide synthesis). Two protecting groups have been used in this study: the fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl Fmoc and the allyloxycarbonyl Alloc groups, carbamates well-suited to standard Fmoc/tBu peptide synthesis.

2 Results and discussion

The prerequisite Nα-protected thiazolidines 2, 3a–c (Fig. 2) have been prepared with good yields (68–78%) from the corresponding chloroformate and the Cys(ΨR,R'pro) [12,13]. To investigate their direct incorporation on solid support, a model peptide sequence: H2N-Phe-Ala-Gly-Sasrin® resin 1 (Fig. 2) was built up using standard protocol of Fmoc/tBu SPPS. The Super acid-sensitive resin Sasrin® allows the cleavage of the peptides from the resin under very low acidic conditions (1% of trifluoroacetic acid TFA) to prevent the integrity of the ring in the case of the Cys(ΨMe,Mepro) moiety [14].

Insertion of Nα-protected thiazolidines in a model peptide.

Our general strategy (Fig. 2) can be recapitulated as follows: incorporation of the Nα-protected thiazolidine 2, 3a–c, removal of carbamate then coupling of the Fmoc-protected pseudoproline-preceding amino acid (FmocGlyF [15] in our case). We choose to use fluoride as activating ester in this step due to their high reactivity and because Fmoc amino acid fluorides were reported to be extremely well suited for hindered amino acids [16].

In this study, the efficiency of reactions was followed by RP-HPLC analysis using a UV detector after cleavage of few beads of resin. Therefore, to get the HPLC standarts of the targeted peptides 7a–c, they have been also synthesized by the common approach using the FmocGlyCys(ΨR,R′pro) dipeptides 4a–c1.

We first investigated the potential of the Fmoc as thiazolidine protecting group due to its popularity in peptide synthesis (Fig. 2). The preliminary assays were realized from the Nα-FmocCys(ΨMe,Mepro) 2. As attempted its coupling was achieved efficiency on supported peptide 1 (as judged by RP-HPLC and mass spectroscopy analyses) but the removal of the Fmoc group from 5 has been the limiting step (Fig. 3).

Basic removal of Nα-FmocCys(ΨMe,Mepro) on the solid support.

Several basic conditions have been used, conditions commonly known as Nα-deprotecting reagents for Fmoc group in SPPS and others: 2% of piperidine, 2% of 1,8-diazobicyclo[5.4.0]undec-7-ene DBU [17], 10% of diethylamine and 50% of morpholine in DMF. But in all cases the HPLC and mass spectroscopy analyses concluded to the opening of the thiazolidine ring. We only detected the cysteinyl containing peptide H2N–CysPheAlaGly–OH 8 and the resulting disulfide peptide H2N–Cys(CysPheAlaGlyOH)PheAlaGly–OH 9 as major product (60% of HPLC conversion ratio). The cleavage of the ring could proceed through a base Schiff intermediate [18–20] under basic conditions and the dimethyl groups, electron donating substituents, could be in favor of the open form. To check that the acidic cleavage from the resin (1% TFA) was not responsible of the ring opening, we carried out the coupling of FmocGlyF straight after the removal. In this case, the coupling step was inefficient maybe due to the steric hindrance on the solid support of the disulfide peptide 9. This result would confirm the instability of the ring during the basic removal conditions.

Consequently we studied the allyl carbamate as an alternative to the Fmoc protecting group. The smooth removal of Alloc group, with catalytic amount of Pd(PPh3)3 in the presence of scavenger for trapping the formed π-allyl, could preserve the integrity of thiazolidine ring. Moreover the orthogonality between the Alloc and Fmoc groups allows the one-pot removal of the allyl carbamate and the acylation of thiazolidine in situ by the preceding amino acid FmocGlyF. The sequence could be applied until completeness of the transformation compared to the stepwise strategy used with the Nα-Fmoc-thiazolidines. This tandem deprotection-coupling reaction reported for other amino acids [21] appeared as an interesting way to investigate in the case of thiazolidines.

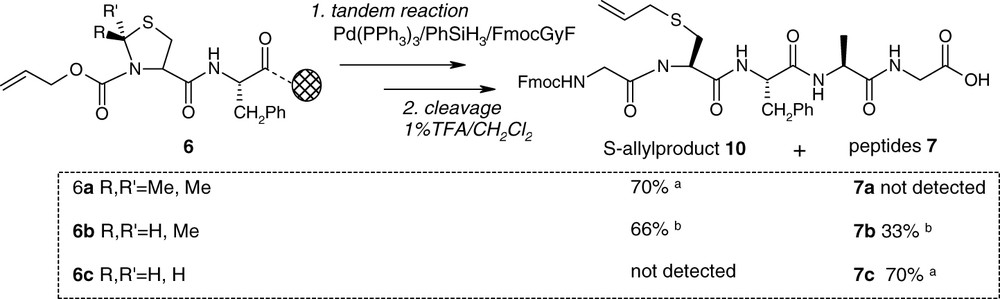

Following the coupling of Nα-Alloc thiazolidines 3a–c by standart protocol (Fig. 2), the tandem deprotection-coupling reactions were carried out from 6a–c with Pd(PPh3)3, PhSiH3 and FmocGlyF (0.2, 24 and 10 equivalents, respectively) in dichloromethane (Fig. 4). Special care has to be taken for the choice of π-allyl scavenger. Indeed it was reported that the use of nucleophilic secondary amine such as morpholine as the allyl acceptor leads to deprotection of Fmoc group [21]. Phenyltrihydrosilane PhSiH3 has been used as a neutral nucleophile able to prevent the formation of allylamine by-product especially observed in the case of secondary amines.

Tandem reaction: a isolated yield; b 1H RMN ratio.

The Nα-AllocCys(ΨMe,Mepro) peptide 6a was first examined under these conditions. The HPLC analysis of the peptide after tandem reaction and cleavage from the resin confirmed the removal of the Alloc group and the efficient coupling of FmocGlyF. Indeed the obtained peptide was detected at 214 and 299 nm (characteristic wavelength of the Fmoc). Unfortunately, the 1H-NMR structure revealed, instead of peptide 7a, the S-allylated product 10 with 70% of isolated yield (Fig. 4). With the more stable Nα-AllocCys(ΨH,Hpro) peptide 6c the peptide 7c was obtained in 70% yield. The Nα-AllocCys(ΨH,Mepro) peptide 6b showed an intermediate behavior: 7b was obtained as the major product, mixed with the by-product 10 (66/33 ratio). In this special case the two peptides having the same retention time, their separation by preparative RP-HPLC was not allowed and the ratio has been obtained by 1H RMN analysis. In all cases, a small amount (10%) of the cysteinyl peptide FmocGlyCysAlaGLy–OH has also been detected.

The opening of the thiazolidine ring during the Alloc removal and the trapping of π-allyl palladium by the thiol group of the so formed base Schiff intermediate could explain the formation of the by-product 10. Moreover a stereoelectonic effect of the 2-C substituents in the heterocyclic ring could justify the differences of reactivity observed between the three thiazolidine residues. Indeed it's well known that the open form in thiazolidine ring is facilitated by the presence of electron donating groups at the C2 position [18,19].

To prevent the formation of the S-allylated peptide 10 from the Cys(ΨMe,Mepro) moiety, we added thiol scavengers, as β-mercaptoethanol or thioanisol, to trap the π-allyl entity and to cause the ring closure from the suggested base Schiff intermediate. We also tested other scavengers or Pd(II) as catalyst: Pd(PPh3)4/Bu3SnH [22,23], Pd(PPh3)4/NaBH4 [24], Pd(PPh3)4/Me2NSiMe3 [25], PdCl2(dba)2/thiosalicylic acid [26], PdCl2(PPh3)2/Bu3SnH/AcOH [27]. None of these reagents avoided product 10 and rather inhibit the reaction by poisoning the catalyst.

3 Conclusion

In the present study, we have investigated a new approach to incorporate directly thiazolidine as Nα-fluoromethyloxycarbonyl and Nα-allyloxycarbonyl residues in a supported peptide sequence. These residues were prepared from the corresponding thiazolidines in good yield (68–78%) and efficiency coupled to a model peptide using standart Fmoc/tBu procedure. Unfortunately in the case of the Cys(ΨMe,Mepro) moiety, the weak point of our approach has been the N-αremoval step of the carbamates due to the instability of the heterocyclic ring under the basic as well as neutral conditions. From this study, it becomes clearly that this instability is a serious limitation to the use of Nα-AllocCys(ΨMe,Mepro) and Nα-FmocCys(ΨMe,Mepro). Therefore we are currently investigating other strategies to avoid the ring opening. The first one is the direct formation of the thiazolidine ring on the solid support from a cysteinyl containing peptide. The other one is the use of fluorinated thiazolidines, the fluorine groups at position C-2 should allow the stabilization of the heterocyclic ring.

4 Experimental section

Reverse phase high pressure liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC) was performed on Waters equipment using C18 columns (Nucleosil 300 Å). The analytical column (250 × 4.6 mm) was operated at 1 ml/min with UV monitoring at 214 and/or 299 nm using an A–B gradient: 5–100% B in 30 min (buffer A: 0.09% trifluoroacetic acid, TFA, in water; buffer B: 0.09% TFA in 90% acetonitrile). The preparative column (250 × 21 mm) was operated at 18 ml/min using the following gradient: 30–100% B in 30 min. Mass spectra were obtained by electron spray ionization (ESI-MS) on a VG Platform II or by chemical ionization (CI-MS, NH3/isobutane) on a Thermofinnigan Polaris Q in the positive mode. 1D and 2D 1H-NMR experiments were carried out using a Bruker Avance 300 MHz spectrometer.

4.1 Nα-Protected thiazolidines

4.1.1 N-Fmoc-2,2-dimethyl-1,3-thiazolidine-4-carboxylic acid (2)

To a suspension of 2,2-dimethyl-l-thiazolidine-4-carboxylic acid hydrochloride [12] (500 mg, 2.5 mmol) in dry CH2Cl2 (5 ml) under argon is added diisopropylethylamine DIPEA (1.1 ml, 6.3 mmol) and 9-fluorenylmethyl chloroformate (0.83 g, 3.2 mmol). The solution is stirred overnight at room temperature and concentrated on vacuum. The crude is purified by flash chromatography (ethyl acetate/cyclohexane/acetic acid, 8/11/0.5) to afford 650 mg (1.7 mmol) of compound 2 (68%). C21H21NO4S (383.47). tR = 28.5 min. CI-MS (m/z): 400.8 [M + NH4]+. 1H-NMR (300 MHz, DMSO d6), δ ppm: 7.90–7.25 (16H, m, 8HFmoc cis + trans), 4.90–4.60 (2H, m, CHα cis + trans), 4.40–4.15 (6H, m, CHFmoc, CH2OFmoc, cis + trans), 3.45–2.95 (4H, m, CH2β cis + trans), 1.80, 1.70, 0.80, 0.90 (12H, 4s, 2CH3cis, 2CH3trans).

4.1.2 N-Alloc-2,2-dimethyl-1,3-thiazolidine-4-carboxylic acid (3a)

Applying the same procedure using allylchloroformate instead of fluorenylmethyl chloroformate, 2 g of 2,2-dimethyl-l-thiazolidine-4-carboxylic acid hydrochloride [12] (10.2 mmol) gave 3a (1.8 g, 7.5 mmol) with 72% yield after flash chromatography purification (ethyl acetate/cyclohexane/acetic acid, 1/3/0.2). C10H15NO4S (245.30). tR = 22.6 min. CI-MS (m/z): 262.7 [M + NH4]+. 1H-NMR (300 MHz, DMSO d6), δ ppm: 5.90–5.75 (1H, m, CHallyl), 5.40–5.20 (2H, m, CH2allyl), 4.90 (1H, dd, CHα, 3J = 11 Hz, 3J = 6 Hz), 4.50–4.30 (2H, m, CH2allyl), 3.40 (1H, dd, CH2β, 2J = 11 Hz, 3J = 7 Hz), 3.10 (1H, dd, 3J = 6 Hz, CH2β), 1.80, 1.70 (6H, 2s, 2CH3).

4.1.3 N-Alloc-2-methyl-1,3-thiazolidine-4-carboxylic acid (3b)

Using the procedure described for 3a, compound 3b (0.97 g, 4.2 mmol) was obtained from 2-dimethyl-l-thiazolidine-4-carboxylic acid hydrochloride [13] (1 g, 5.4 mmol) with 78% yield. C9H13NO4S (231.27). tR = 20.7, 21.2 min. CI-MS (m/z): 248.8 [M + NH4]+. 1H-NMR (300 MHz, DMSO d6), δ ppm: 5.90–5.65 (1H, m, CHallyl), 5.20–4.90 (2H, m, CH2allyl), 5.00 (1H, q, CHCH3, 3J = 7.4 Hz), 4.70–4.55 (1H, m, CHα), 4.50–4.30 (2H, m, CH2allyl), 3.50–3.35 (1H, m, CH2β), 3.20–2.95 (1H, m, CH2β), 1.50–1.40 (3H, m, CH3).

4.1.4 N-Alloc-1,3-thiazolidine-4-carboxylic acid (3c)

Applying the procedure for 3a, l-thiazolidine-4-carboxylic acid hydrochloride (1 g, 5.9 mmol) gave 3c (0.95 g, 4.4 mmol) with 74% yield. C8H11NO4S (217.25). tR = 18.9 min. CI-MS (m/z): 234.6 [M + NH4]+. 1H-NMR (300 MHz, DMSO d6), δ ppm: 5.90–5.70 (1H, m, CHallyl), 5.20–4.95 (2H, m, CH2allyl), 4.75–4.65 (1H, m, CHα), 4.50–4.45 (2H, m, CH2allyl), 4.40 (1H, d, SCH2N, 2J = 7.4 Hz), 3.40–3.20 (1H, m, CH2β), 3.15–3.00 (1H, m, CH2β).

4.2 Dipeptide syntheses

4.2.1 FmocGlyCys(ΨMe,Mepro) (4a)

Yield: 75%. C23H24N2O5S (440.1). tR = 27.1 min. CI-MS (m/z): 440.9 [M + H]+. 1H-NMR (300 MHz, DMSO d6), δ ppm: 7.90–7.33 (9H, m, 8HFmoc, NH), 4.50–4.40 (1H, m, CHα), 4.21–3.56 (5H, m, CHFmoc, 2CHαGly, CH2OFmoc), 3.50–3.34 (2H, m, CH2β), 1.78, 1.76 (6H, 2s, 2CH3).

4.2.2 FmocGlyCys(ΨMe,Hpro) (4b)

Yield: 82%. C22H22N2O5S (426.5). tR = 25.7 min. CI-MS (m/z): 427.4 [M + H]+. 1H-NMR (300 MHz, DMSO d6), δ ppm: 7.90–7.30 (9H, m, 8HFmoc, NH), 5.10–4.90 (1H, m, CH), 4.30 (1H, t, CHα, 3J = 10 Hz), 4.10–3.70 (5H, m, CHFmoc, 2CHαGly, CH2OFmoc), 3.20–3.55 (2H, m, CH2β), 1.45–1.20 (3H, m, 2CH3).

4.2.3 FmocGlyCys(ΨH,Hpro) (4c)

Yield: 91%. C21H20N2O5S (412.5). tR = 24.8 min. CI-MS (m/z): 413.3 [M + H]+. 1H-NMR (300 MHz, DMSO d6), δ ppm: 7.90–7.33 (9H, m, 8HFmoc, NH), 4.51–4.40 (1H, m, CHα), 3.60–3.40 (5H, m, 2CHαGly, CHFmoc, CH2OFmoc), 3.50–3.35 (2H, m, CH2β), 3.40–3.20 (2H, m, NCH2S).

4.3 Peptide syntheses

Peptides were built up from Sasrin® resin by standard solid phase procedure using 2 equivalents of N-Fmoc amino acids, Nα-protected thiazolidines 2, 3a–c or dipeptides 4a–c, 2 equivalents of PyBOP (benzotriazol-1-yloxy)tris (pyrrolidino)phosphonium hexafluorophosphate) and 4 equivalents of DIPEA in DMF as coupling conditions and piperidine solution (20% in DMF) for Nα-Fmoc removal. Peptides or an aliquot were cleaved from the resin with a solution of 1%TFA in DCM.

4.3.1 H2N-PheAlaGlySasrin® (1)

C14H19N3O4 (293.3). tR = 13.0 min. ESI-SM (m/z): 294.2 [M + H]+.

4.3.2 FmocCys(ΨMe,Mepro)PheAlaGlySasrin® (5)

C25H33N3O7S (658.8). tR = 29.1 min. ESI-SM (m/z): 659.2 [M + H]+.

4.3.3 AllocCys(ΨMe,Mepro)PheAlaGlySasrin® (6a)

C25H33N3O7S (519). tR = 23.2 min. ESI-SM (m/z): 520 [M + H]+.

4.3.4 AllocCys(ΨH,Mepro)PheAlaGlySasrin® (6b)

C24H31N3O7S (505). tR = 22.3, 22.6 min. ESI-SM (m/z): 506.1 [M + H]+.

4.3.5 AllocCys(ΨH,Hpro)PheAlaGlySasrin® (6c)

C23H29N3O7S (491.5). tR = 21.3 min. ESI-SM (m/z): 492.6 [M + H]+.

4.3.6 FmocGlyCys(ΨMe,Mepro)PheAlaGly (7a)

Yield: 77%. C37H41N5O8S (714.9). tR = 27.5 min. ESI-SM (m/z): 716.1 [M + H]+.

4.3.7 FmocGlyCys(ΨH,Mepro)PheAlaGly (7b)

Yield: 70%. C36H39N5O8S (701.8). tR = 27.3 min. ESI-SM (m/z): 351.2 [M + 2H]2+.

4.3.8 FmocGlyCys(ΨH,Hpro)PheAlaGly (7c)

Yield: 81%. C35H37N5O8S (687.8). tR = 26.1 min. ESI-SM (m/z): 344.3 [M + 2H]2+.

4.3.9 CysPheAlaGlySasrin® (8)

C17H24N4O5S (396.5). tR = 14.3 min. ESI-SM (m/z): 199.2 [M + 2H]2+.

4.3.10 Cys(CysPheAlaGly)PheAlaGlySasrin® (9)

C34H46N8O10S2 (790.9). tR = 12.0 min. ESI-SM (m/z): 791 [M + H]+.

4.3.11 FmocGlyCys(allyl)PheAlaGlySasrin® (10)

C37H41N5O8S (715.8). tR = 27.2 min. ESI-SM (m/z): 716 [M + H]+.

Acknowledgements

The ‘Institut universitaire de France’ (IUF) is gratefully acknowledged for financial support as well as the MENRT for grant to M.F.

1 Coupling the FmocGlyF in solution to the corresponding unprotected Cys(ΨR,R'pro) allowed to get the dipeptides in good yield (75–91%).