The vast majority of cluster compounds are supposed to be diamagnetic, and to possess a definite (even) number of valence electron, mainly dependent on their geometry [1]. This conviction was so strong that paramagnetic behavior was normally associated with odd number of electrons, even in the absence of experimental evidences [2]. However, in recent years, electrochemical experiments have shown that many cluster cores are able to add/release electrons without disruption [3]. At the same time, an increasing number of clusters violating electron counting rules have been isolated and characterized. Some of them have been isolated only as paramagnetic compounds [4], only a few are sufficiently stable that could be isolated in multiple oxidation states [5]. For this peculiar behavior of metal clusters, frequently referred as electron sponges [6], a molecular (rather than atomic) type of magnetism was claimed, since they can store unpaired spin on molecular orbital delocalized over the entire metallic particles (which can approach nano-sized dimensions), instead of single metallic ions [7]. One example of this sort are the [Fe3Pt3(CO)15]n– clusters (n = 0–2). The structure of the three congeners [5,8], the ESR of the monoanion [9], the computational explanation for their behavior [10,11], and peculiar electrochemical [8,10] and magnetic properties have been described [7].

In this paper the new family of multivalent [Fe6Ni6N2(CO)24]n– (n = 1–4) clusters is reported. The three stable anions [Fe6Ni6N2(CO)24]n– (n = 2–4) have been synthesized by the reaction between (NEt4)2[Ni6(CO)12] and the preformed nitride (NEt4)[Fe4N(CO)12], in acetonitrile. The exact composition of the final reaction mixture is strongly dependent from the experimental details (molar ratio of the reagents, temperature, solvents, etc.). Subsequent extraction of the reaction mixture with MeOH, THF, acetone and MeCN allowed isolating a large variety of mixed-metal clusters, which are not, as yet, fully characterized. Some of them contain an interstitial nitride (such as [HFe4Ni2N(CO)13]2– or [HFe5NiN(CO)14]2–) [12] some others are homoleptic carbonyl compounds (such as [FeNi5(CO)13]2– and [Fe3Ni(CO)12]2–) [13].

When the reaction is carried at room temperature, in acetonitrile, with a Fe4N/Ni6 = 2:1 molar ratio, the main products are the anions [Fe6Ni6N2(CO)24]n– (n = 2–4), which can be fractionated easily, owing to their different solubility in MeOH, acetone and acetonitrile, brought about by their different negative charge1. Therefore, the three anions could all be examined by single crystal X-ray analysis2.

Later on, we could interconvert smoothly and selectively the three anions, by using conventional redox reagents (H+, atmospheric oxygen, tropilium or ferrocenium cations were proved suitable for oxidations, cobaltocene for the reduction to [Fe6Ni6N2(CO)24]3– and sodium-ketyl for the obtainment of the tetraanion), or controlled potential electrolysis.

As clearly demonstrated by the cyclic voltammogram shown in Fig. 1, the dianion [Fe6Ni6N2(CO)24]2– exhibits in MeCN solution either a (coulometrically measured) one-electron oxidation (E°′2–/– = +0.17 V, vs. SCE; ΔEp = 74 mV at 0.2 V s–1), which possesses features of partial chemical reversibility (at 0.2 V s–1: ipc/ipa = 0.7), or two stepwise (coulometrically measured) one-electron reductions (E°′2–/3– = –0.40 V, E°′3–/4– = –0.90 V; ΔEp = 66 and 62 mV, respectively, at 0.2 V s–1), which are chemically reversible both in the cyclic voltammetric (ipa/ipc constantly equal to 1.0) and in the macroelectrolysis time scales [14].

Cyclic voltammogram recorded at a platinum electrode in MeCN solution of [Fe6Ni6N2(CO)24]2– (0.2 × 10–3 mol dm–3). [NBu4][ClO4] supporting electrolyte (0.1 mol dm–3). Scan rate: 0.5 V s–1.

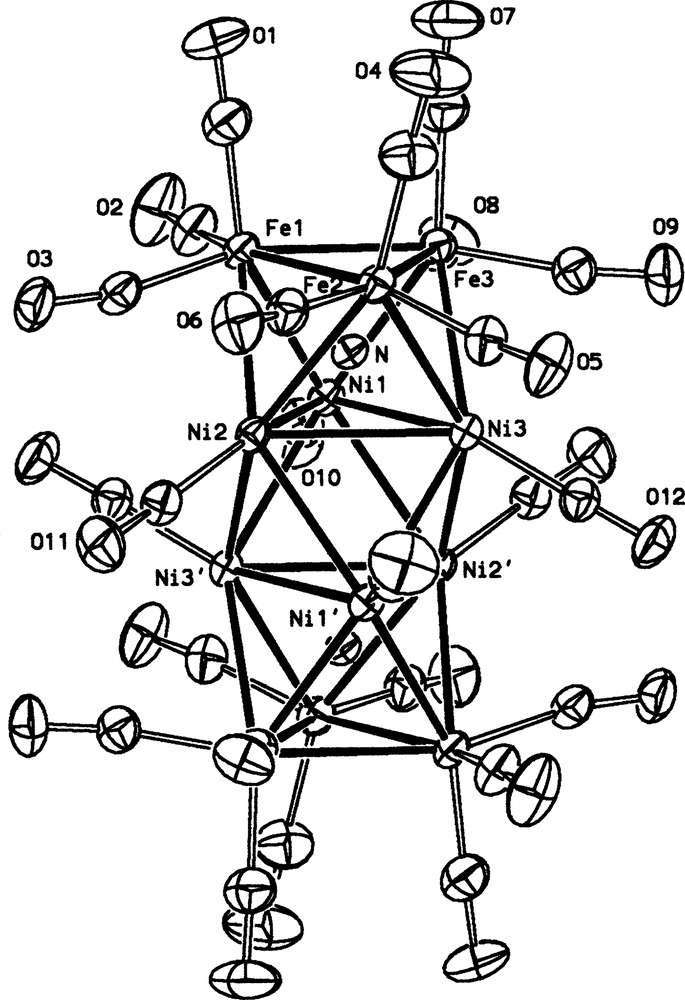

The X-band EPR spectrum of the electrogenerated trianion [Fe6Ni6N2(CO)24]3– displays under glassy conditions (T = 103 K) a broad and unresolved signal, whose lineshape analysis can be accounted for by the presence of one unpaired electron (doublet state, S = 1/2) substantially delocalized on the Fe–Ni metal skeleton. In fact, the average g value of 2.033(8) well agrees with the metallic character of the signal. No evidence for hyperfine or superhyperfine splittings (if any) of the magnetically active nuclei (57Fe, 61Ni, 14N) was detected [15,16]. The fluid solution is EPR mute, likely due to effective fastening of the electron relaxation rates in fast motion conditions [15]. In the solid state, at room temperature, an authentic sample of the trianion [Fe6Ni6N2(CO)24]3– exhibits a broad signal with a poorly resolved axial structure (g∣∣ > g⊥ ≠ gelectron = 2.0023) and no hyperfine or superhyperfine splittings. The pertinent gi values are: g∣∣ = 2.99(5), g⊥ = 2.10(5). In solution, under glassy conditions, it exhibits an absorption pattern quite similar to that described above for the electrogenerated analogue. In agreement with the substantial electrochemical reversibility of the pertinent redox changes [14], the structure of the three anions are very similar, and Fig. 2 illustrates the molecular structure of the dianion.

The solid state structure of dianion [Fe6Ni6N2(CO)24]2–.

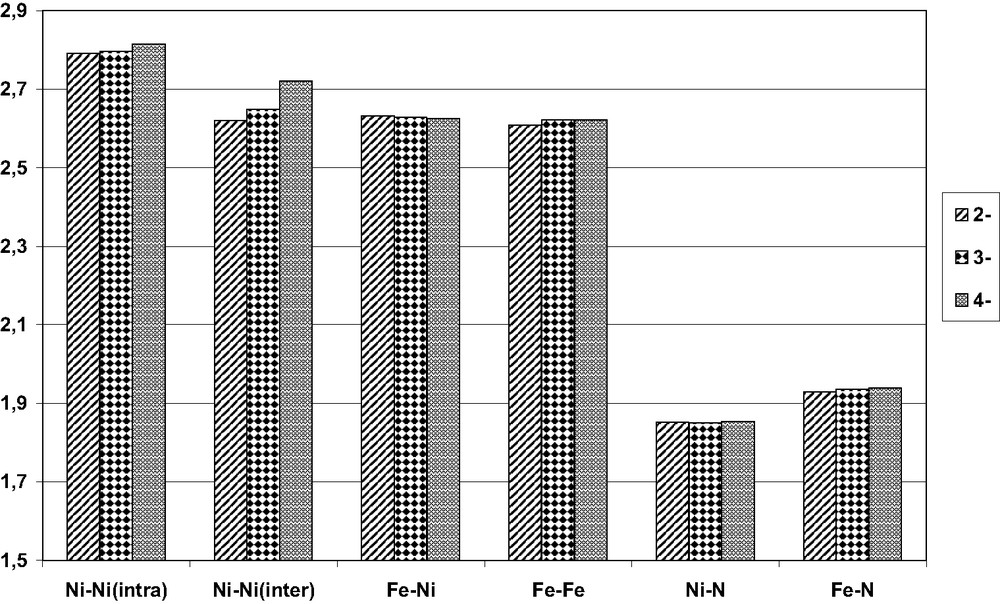

The metallic framework is composed by four homometallic triangular staggered layers: the two external are formed by iron, the two internal by nickel. This arrangement defines three octahedral cavities, the two external being filled by the two interstitial nitrides. Each iron vertex is bound to three terminal CO, each nickel to only one. All three anions can be numbered coherently, since they all lay on a crystallographic center of symmetry, and are therefore of crystallographic Ci symmetry. However, the idealized symmetry is D3d, with the six iron and the six nickel atoms being equivalent. Table 1 and Fig. 3 compare the bonding distances of the three anions, which are strong experimental evidences of the electron sponge ability of the metallic framework. As a matter of fact, the Ni–N and Fe–N are virtually identical in all clusters; variations are limited in the Ni–Ni bonds, which monotonically increase with the increasing number of valence electrons. Based on this, it is reasonable to assume that, in the series 2–/3–/4– the bond order of the Ni–Ni interactions are partially reduced (Table 2).

Average bond distances within the anions [Fe6Ni6N2(CO)24]n–, with root mean squared deviations in parentheses

| 2– | 3– | 4– | |

| Ni–Ni(intra) a | 2.791(8) | 2.797(10) | 2.814(7) |

| Ni–Ni(inter) a | 2.620(8) | 2.648(11) | 2.720(4) |

| Fe–Ni | 2.632(34) | 2.628(13) | 2.625(28) |

| Fe–Fe | 2.608(13) | 2.621(10) | 2.621(10) |

| Ni–N | 1.853(4) | 1.849(6) | 1.853(6) |

| Fe–N | 1.929(1) | 1.937(5) | 1.9384(3) |

| Fe–C | 1.746(1) | 1.740(5) | 1.744(2) |

| Ni–C | 1.781(7) | 1.78(1) | 1.77(1) |

| C–O | 1.151(8) | 1.154(8) | 1.157(10) |

a Intra = bonds within the same triangular layer (unprimed Ni atoms in Fig. 2), inter = bonds between two triangular layers (primed and unprimed Ni atoms in Fig. 2).

The M–M and M–N bond distances in the three anions.

Crystallographic data

| Compound | 2– | 3– | 4– |

| Formula | C72H40Fe6N2Ni6O24P2 | C48H60Fe6N5Ni6O24 | C92H86Fe6N6Ni6O24P2 |

| M | 2066.41 | 1778.37 | 2409.03 |

| Crystal system | Triclinic | Triclinic | Triclinic |

| Space group | |||

| a (Å) | 12.710(1) | 11.986(1) | 13.057(1) |

| b (Å) | 13.491(1) | 12.094(1) | 14.450(1) |

| C (Å) | 13.683(1) | 13.797(1) | 14.930(1) |

| α (°) | 63.41(1) | 114.29(1) | 111.75(1) |

| β (°) | 71.82(1) | 104.25(1) | 107.68(1) |

| γ (°) | 68.64(1) | 102.72(1) | 93.28(1) |

| U (Å3) | 1922.4(3) | 1645.8(2) | 2446.5(3) |

| Z | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Number of reflections (total; independent) | 22 238; 8953 | 19 787; 7993 | 28 025; 11294 |

| Rint | 0.0361 | 0.0212 | 0.0208 |

| Final R2 and R2w indices (F2; all reflections) | 0.045; 0.056 | 0.040; 0.061 | 0.041; 0.062 |

| Conventional R1 index (I > 2σ(I)) | 0.028 | 0.024 | 0.025 |

A peculiarity of the clusters is also the rather large number of valence electrons (168–170 C.V.E.'s, respectively), instead of 160–162 which could be anticipated on the basis of the Wade- Mingos P.S.E.P.T. rule [1], or from existing compounds which adopt the very same metal arrangement [17]. This difference is not unexpected, considering the ability of the interstitial atoms to modify the bonding character of the frontier molecular orbitals [18]. In order to understand if this large discrepancy and the redox flexibility could be both related to the presence of the interstitial nitrides, we performed EHMO and DFT calculations, with substantial agreements. CACAO [19] calculations on the [Fe6Ni6N2(CO)24]n– cluster anions show that the HOMO level is constituted by two degenerate orbitals which are essentially antibonding combinations of the metal 3d orbitals only, with no contribution from the 2p nitrogen orbitals. Thus, populating these levels reduces the metal-metal bond order, but has no influences on the metal–nitrogen bonds. These results confirm that the interstitial nitrogen atoms can prevent cluster fragmentation by forming ‘radial’ metal–nitrogen bonds, otherwise addition of electrons to the dianion [Fe6Ni6N2(CO)24]2– (corresponding to its reduction) would mean weakening of ‘tangential’ metal–metal bonds. As observed also for other cobalt clusters, it appears that polynitrido species are built up by fairly rigid units, containing interstitial atoms, linked by looser metal-metal bonds, and that these intercage empty polyhedra can act as sink for additional valence electrons [18,20]. The electronic structure of the [Fe6Ni6N2(CO)24]x– (x = 2–4) complexes has also been investigated theoretically in the framework of the density functional theory (DFT). Calculations have been performed on the X-ray geometries (in the Ci symmetry) using the hybrid three parameter functional B3LYP [21] and a full electron split valence double-ζ basis set with polarization functions added to all atoms [22] as implemented in the Gaussian suite of programs [23]. Interestingly, for the dianion the triplet state (S = 1) is calculated to be more stable than the singlet one by about 23 kJ mol–1. As expected, in the closed-shell configuration, the HOMO is no longer degenerate as in the EHMO calculation (see Fig. 4). However, the LUMO is only at about 1 eV higher in energy, therefore accounting for the promotion of one electron to give the more stable triplet configuration. As shown in Fig. 4 the HOMO and LUMO in the closed-shell configuration are completely delocalized on the twelve metal atoms, without contributions of the 2p orbitals of the nitrogen atoms. It should also be noted that the atomic charge of the N atoms is equal to about –1 in all complexes. This further confirms that the extra-electrons in the tri- and tetra-anions are not accommodated on the interstitial atoms. In the case of the [Fe6Ni6N2(CO)24]3– and [Fe6Ni6N2(CO)24]4– complexes S is equal to 1/2 and 0, respectively. In particular, for the [Fe6Ni6N2(CO)24]4– species, the triplet state is higher in energy by more than 80 kJ mol–1 with respect to the singlet one. In the light of the results of these calculations, the reduction of the [Fe6Ni6N2(CO)24]2– to the [Fe6Ni6N2(CO)24]4– should be accompanied by a change of the spin state from triplet ([Fe6Ni6N2(CO)24]2–) to doublet ([Fe6Ni6N2(CO)24]3–) to singlet ([Fe6Ni6N2(CO)24]4–). Further experiments are planned, to isolate larger amounts of the three anions, to better establish their magnetic behavior. In conclusion, the clusters [Fe6Ni6N2(CO)24]n– (n = 2–4) are ligand stabilized-metallic particles which can be isolated in three forms, differing from their charge and (possibly) their spin multiplicity. The state of the particle can be switched with selective redox reactions and therefore can be easily controlled by chemical or electrochemical means.

Orbital energy diagram of the [Fe6Ni6N2(CO)24]2– complex in the singlet (on the left) and in the triplet (on the right) spin states; in the boxes are also reported the HOMO and LUMO orbitals of the singlet species.

Supporting information available

Table S3 (supporting information) contains the full list of crystallographic data. CCDC 249247 (2–), 249248 (3–) and 249249 (4–) contains the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge at http://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/conts/retrieving.html [or at Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center, 12 Union Road, Cambridge CB2 1EZ, UK; fax: +44 122 336 033; E-mail: deposit@ccdc.cam.ac.uk].

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by MIUR (Cofin 2003 and FAR). We acknowledge Davide Proserpio for helpful suggestions.

1 (NEt4)2[Ni6(CO)12] (0.49 g; 0.52 mmol) and (NEt4)[Fe4N(CO)12] (0.75 g; 1.07 mmol) were dissolved in 45 ml of MeCN and stirred at room temperature for 72 h: the solvent was then removed in vacuum, and the black residue was suspended overnight in MeOH (mixed NEt4+/PPh4+ salts were obtained, if PPh4Br was added ad this stage). The solution contained fairly pure [Fe6Ni6N2(CO)24]2–, which was precipitated by the addition of PPh4Br and water, filtered, dried and crystallized from THF/2-propanol. The solid residue was extracted with acetone and then acetonitrile. The two solutions were layered with 2-propanol and di-isopropyl ether, respectively, yielding variable amounts of [Fe6Ni6N2(CO)24]3– and [Fe6Ni6N2(CO)24]4–. ν(CO) for [Fe6Ni6N2(CO)24]2–: 2016vs, 2003vs, 1954m, 1911w cm–1, in THF. ν(CO) for [Fe6Ni6N2(CO)24]3-: 1993vs, 1978vs, 1924m, 1882w cm–1, in MeCN. ν(CO) for [Fe6Ni6N2(CO)24]4–: 1974vs, 1951vs, 1930m, 1884w cm–1, in MeCN.

2 Crystal data are reported in table 2. Bruker SMART CCD area-detector, T 223 K, Mo Kα radiation (λ = 0.71073 Å), ω scan mode, θmin = 3°, θmax = 26°. Structures solved by direct methods and refined by full-matrix least squares. Program used was Personal SDP on a Pentium III computer.