1 Introduction

The large success encountered by liquid-state NMR during the last three decades is inherently associated with the robustness of the theoretical description of the spin dynamics. Indeed the responses of nuclear magnetization to excitations and evolutions as well as its inductive detection are described by linear differential equations. This is allowed thanks to the statistical reduction of the sample to one “average” molecule, disregarding intermolecular couplings. The rise of static magnetic field value and of the probeheads' quality factor tends to break down this assumption [1]. First, the precession of a large magnetization creates by induction a current in the coil which, by retro-action, generates an rf field which interacts with the magnetization , leading to the so-called radiation damping effect (RD) [2]. Second, the distant dipolar fields (DDFs) between molecules are not averaged out by Brownian motions and induce, for large magnetization, many effects such as multiple echoes [3], intermolecular coherences [4], spectral clustering [5], cross-precession [6] and even chaotic behavior [7,8]. During the recent years, interest for these DDF and RD effects has moved from curiosity to the idea that new applications could derive from these phenomena, for instance, acquisitions of spectra and images in inhomogeneous fields [9], non-linear amplification of spin precession [10], contrast agent in MRI when it is combined to RD [11] or spectroscopy with a better sensitivity when it is used as a mechanism designed to allow polarization transfer [12].

These applications have driven us to careful studies of DDF. The exploration of DDF with thermally polarized liquids is limited by the poor dipolar field they create (less than 5 × 10−8 T). Resorting to polarized nuclear spin systems, such as optically polarized noble gas, allows the preparation of much larger dipolar fields (up to about 5 × 10−5 T) and, at least partially, to the study of large DDF in the presence of reduced RD effects. Instead of using liquid xenon [13] or mixture of 3He/4He [14] in low field and low temperature, we are addressing these questions in high field (11.7 T) using dissolved laser-polarized xenon. We take benefit from the existence of solvent and solutes to probe xenon magnetization directly by 129Xe NMR but also indirectly by 1H NMR. We, here, report on the main features observed on the xenon and proton spectra.

2 Materials and methods

Isotopically enriched 129Xe (96% from Chemgas) was polarized by spin-exchange with optically pumped Rb [15], using a home-built apparatus [16]. According to the orientation of the quarter wave plate and the direction of the static magnetic field, xenon was prepared either with a positive or a negative spin temperature. We needed 3–4 batches to prepare the right amount of xenon for the experiments reported here. The container was transported in the fringe field of a 11.7-T magnet, where it was heated. Polarized xenon was, then, transferred by cryo-condensation into the NMR tube of interest. The latter was a 3-mm O.D. NMR tube from Cortec closed by a J. Young valve. It contained deuterated hexane (90 μL) as solvent and trans-2 pentenal as solute (c = 4 mMol/L), and was previously degassed. After xenon transfer, the tube was rapidly warmed, shaken, thermalized at 273 K in a ice/water mixture and put back into the high field NMR magnet. A delay of about 2 min was needed to ensure the stabilization of the magnetic field homogeneity and the correct tuning and matching of the xenon and proton rf channels. Using this protocol, polarization up to 49% in the gaseous phase inside the NMR magnet was achieved with a usable polarization between 10 and 25% for dissolved laser-polarized xenon.

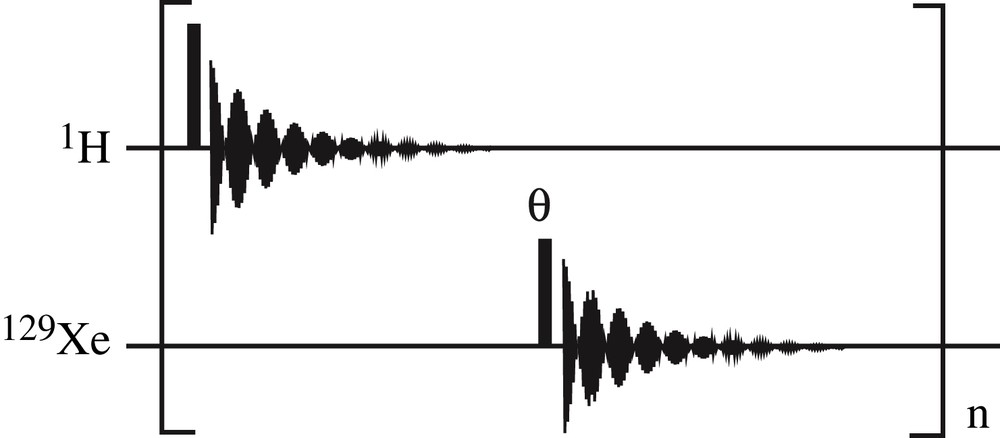

NMR spectra were acquired on a Bruker Avance500 spectrometer using a Bruker 1H/15N/X probe. For positive xenon spin temperature, the pulse sequence depicted in Fig. 1 was used. It consisted of an alternate acquisition of proton and xenon spectra. The pulse on the xenon channel allowed the reduction of the xenon magnetization by an apparent factor cos θ.

Pulse sequence used to monitor the xenon and proton spectral properties. A 90° hard pulse (pulse duration of 6.2 μs) is used for proton excitation while the hyperpolarized xenon magnetization is reduced, thanks to pulses of angle θ (pulse duration of 4 μs). The delay between two consecutive proton spectra is 22.2 s and the delay between proton and xenon pulses is 10.3 s.

The protocol used to observe the spontaneous large transverse magnetization (maser emission) consisted of (i) the preparation of xenon with a negative spin temperature obtained by spin-exchange optical pumping, (ii) the same procedure to dissolve xenon and (iii) the acquisition of FIDs at the xenon frequency without any rf excitation. It was carefully checked that the spectrometer did not emit rf excitation using such a sequence. For the experiment reported here, deuterated cyclohexane (90 μL) was used as solvent for trans-2 pentenal (c = 3 mmol/L) and xenon, temperature was set to 293 K.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Xenon spectral features

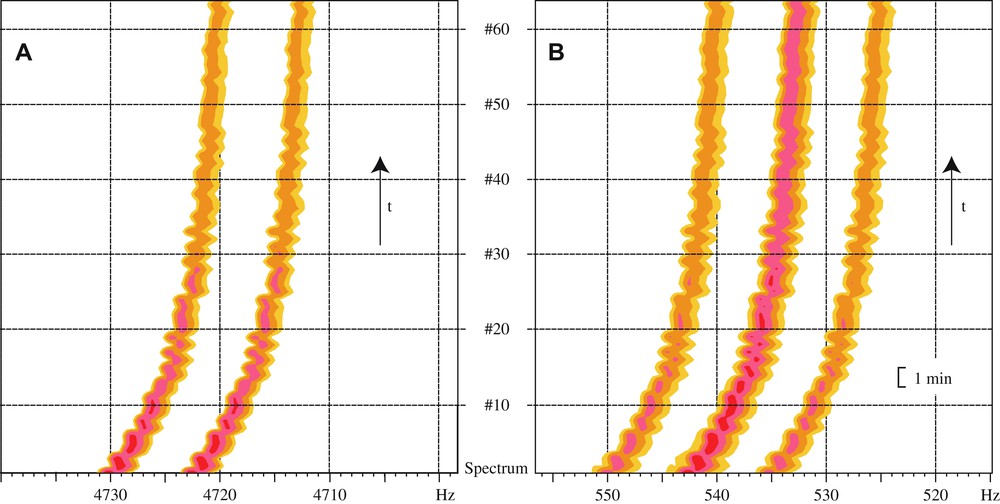

The 129Xe NMR spectra of solutions containing a large amount of laser-polarized xenon were different from those for which xenon was thermally polarized. Fig. 2 illustrates the variation of the spectral lines as a function of xenon magnetization. These spectra were acquired in alternation with the proton spectra discussed in Section 3.2 using the pulse sequence of Fig. 1. In this experiment, xenon polarization was 0.18 for the initial spectrum (stable state, positive spin temperature). Xenon concentration was about 1.5 mol/L. Three features, which changed with the polarization level, were observed on the xenon spectra (Fig. 2).

- – At high polarization, narrow lines superimposed on the main xenon resonance line (spectrum #1 and #5). They should result from spectral clustering effects which appeared at high magnetization. Under the influence of distant dipolar fields and static magnetic field inhomogeneities the statistical nuclear spin system organized itself in such a way that a large number of spins precesses in a coherent way [1,7,13,14]. As theoretically predicted [7], this special feature was even more evident when a very small xenon flip angle (inset of Fig. 2) was used.

- – The average resonance frequency of the xenon spins was not constant along the experiment performed without deuterium lock. Indeed, the Larmor frequency was dependent on the local magnetic field, equal to the sum of the external magnetic field (corrected by the electronic susceptibility of the sample) and the magnetic field created by the xenon nuclear magnetic moments, i.e. the xenon average dipolar field [17]. The decay of xenon magnetization reduced the average dipolar field created by this species, explaining the change of xenon resonance frequency [18].

- – The xenon resonance line-width was also strongly affected by the presence of a high xenon magnetization since it was narrowed by more than a factor of three along the experiment. A small radiation damping contribution was expected since the radiation damping characteristic rate [2] was scaled down by the low Q value of the probe, the small filling factor (inverse 5 mm probehead with a 1.6 I.D. NMR tube) and its dependence on |γXe|3. Experiments had shown that it could not explain the whole broadening, but the interplay between the static magnetic field inhomogeneities and the distant dipolar fields changed the contributions of the latter along the sample, creating a distribution of experienced average dipolar fields [18].

Evolution of the 129Xe resonance line shape along the experiment performed with the sequence of Fig. 1 and a xenon flip angle of ∼20°. Only 5 out of the 64 acquired spectra are shown. In inset, this xenon spectrum was acquired with a very small flip angle (∼2.5°) prior to the beginning of the experiment. The magnitude of the dipolar field Bdip was 0.46 μT according to proton measurements; this might represent a shift of about −4 Hz for 129Xe spins (see Ref. [18] for a discussion).

Due to the superimposition of clustering effect, distribution of dipolar fields, and radiation damping, this experiment clearly reveals the richness of the xenon spin dynamics when large xenon magnetization is present but also the difficulty to determine the principal characteristics (resonance frequency, average dipolar field) of the spin system by exploiting xenon spectra [18].

3.2 Proton NMR spectra

The principal features of proton spectra of a solute in the presence of large amounts of polarized xenon can be seen in Fig. 3, obtained using the pulse sequence of Fig. 1. If the 1H resonance line-width remained constant along the experiment, the two other main 1H spectral parameters were affected.

- – Obviously, when the experiment was performed without locking the magnet, the resonance frequency of any proton changed according to the xenon magnetization. The variations were identical for all protons as observed in Fig. 3 for aldehyde proton (A) and methyl group (B) of trans-2 pentenal. This change of magnetic field experienced by any proton resulted from the field created by xenon magnetization, [17]. The shift δH in hertz was

| (1) |

| (2) |

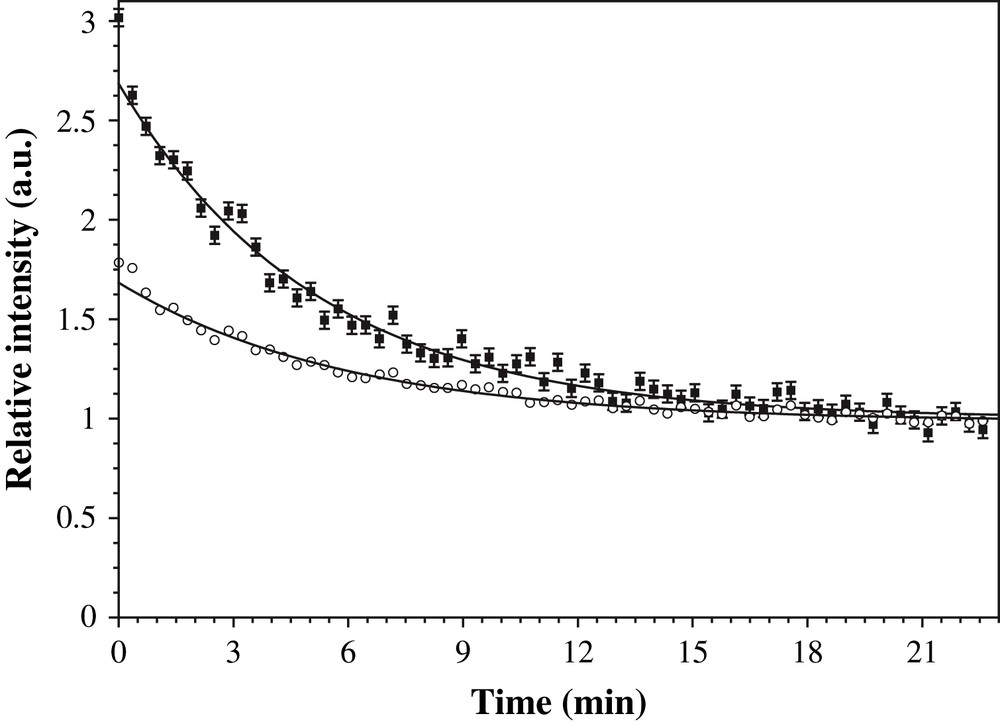

- – Proton peak intensities were also strongly affected by the presence of laser-polarized xenon with a positive spin temperature (Fig. 3). Signal intensities were strongly enhanced at the beginning of the experiment when compared to that at the end, i.e. when xenon magnetization was strongly reduced by pulses. In Fig. 4, the signal intensities of the aldehyde proton and of the methyl group are represented as a function of time. The best-fit theoretical curves to Acosn−1 θ + B are superimposed. It clearly appeared that, conversely to the resonance frequency shift, the amount of proton signal enhancement A was dependent on the considered proton. It was 2.4 times larger for the aldehyde proton than for the methyl group. This relative proton enhancement ηH = A/B results from the xenon–proton dipolar cross-relaxation (SPINOE) [20,21]. Using a simple linear model, it is proportional to

| (3) |

Example of the evolution of the proton resonance line as a function of the xenon magnetization. Between two consecutive FIDs a θ ∼ 20° hard pulse is applied on the xenon spins, reducing xenon magnetization and thus the average dipolar field and the SPINOE it creates. These 1H spectra were obtained with the pulse sequence of Fig. 1, while the associated 129Xe spectra are presented in Fig. 2. (A) Aldehyde proton of trans-2 pentenal; and (B) methyl group of trans-2 pentenal.

Variation of the relative signal intensity of the aldehyde proton (filled squares) and methyl proton (open circle) as a function of time. Between points n and n + 1 the xenon magnetization is reduced by a θ ∼ 20° hard pulse. Same experiment as in Fig. 3.

Proton NMR consequently appears as a valuable source of information on the xenon magnetization. Indeed the frequency shifts are identical for all protons and characterize the average xenon magnetization along the sample, since it only results from long-distance dipolar interactions averaged on the whole sample. On the other hand, the variations of the proton signal intensities depend on SPINOE, which is a local effect. Even if this enhancement is dependent on the proton longitudinal self-relaxation time and of the xenon affinity to the molecule (Fig. 3), relative variations in time or in space along the sample allow the characterization of the local xenon magnetization. For instance, an enhancement of proton signal happens for xenon with positive spin temperature, while xenon with negative spin temperature induces a decrease of proton signal (Eq. (3)). The possible interest in the knowledge of the xenon magnetization sign resides in the dependence of the frequency shift δH on the geometric factor ξ, which can be either positive or negative (Eq. (1)).

3.3 Maser emission

These experiments designed to explore the effect of DDF and to characterize the average dipolar field induced by xenon magnetization were primarily performed with positive xenon spin temperature. Indeed for negative xenon spin temperature, the magnetization was anti-aligned with the static magnetic field, i.e. it was in an unstable state, with the upper Zeeman level more populated. In these conditions, any rf excitation could excite, due to radiation damping, a larger amount of xenon magnetization than expected. As a consequence, even if similar behaviors were observed for negative xenon spin temperature [18], this non-linear coupling could inhibit the preceding careful analysis designed to comparatively study the variation of SPINOE, average frequency shifts, line broadening and xenon signal intensities.

With the recently achieved larger Bdip values, i.e. with the larger xenon magnetization , the situation has become even more curious. Indeed, as shown in Fig. 5, the system became able to spontaneously create a large transverse magnetization, i.e. emit a burst of rf irradiation. This is reminiscent to maser emission. Similar spontaneous maser effects were observed for laser-polarized 3He [22,23] but in a situation where the optical pumping cell was connected by diffusion to the NMR active volume.

Observation of a spontaneous transverse xenon magnetization, i.e. a maser emission. Xenon was laser-polarized with a negative spin temperature. No radio-frequency pulse was applied, only signal acquisition at the xenon frequency was performed.

Qualitatively, this maser emission can be explained in such a way that the presence of a large amount of xenon in the sample induces a non-negligible spin-noise in the coil [24,25]. These small fluctuations of the transverse magnetization can pass a threshold defined by the relative weight of transverse relaxation which tends to wash out these fluctuations and radiation damping, which tends to amplify them by driving the magnetization towards its stable state, i.e. aligned with the static magnetic field [26]. When this requirement is achieved maser emission starts. The RD coupling between the transverse magnetization and the coil is the motor which is active when the transverse relaxation time is longer than the characteristic RD time [27]. When this condition stops to be valid, the maser emission stops. Obviously, this simple model has to be refined to take into account the collective effects present in xenon spin dynamics, which result from DDF and lead, for instance, to the appearance of spectral clustering.

4 Conclusions

Distant dipolar fields appear as a source of complex spin dynamics but promising perspectives [9–12] deserve their careful study in order to bring their applications from specialized laboratories to the majority. In this article, we have illustrated the variety and the complexity of phenomena induced by large DDF obtained when a large amount of laser-polarized xenon is dissolved. In particular, we are reporting the largest average dipolar field observed in a deuterated solvent. This was achieved by increasing the solvent solubility through lowering the temperature. This approach appears appealing since a larger range of diffusion coefficients or of average dipolar field can thus be explored on the same apparatus. Experimental protocols are nevertheless complicated by always possible temperature gradients, which might induce biases. We also show the complementarity between proton and xenon NMR to probe xenon magnetization. Finally, we are reporting what we believe to be the first spontaneous maser emission observed at room temperature in a commercial NMR spectrometer using a solute previously polarized in a batch mode. This large spontaneous transverse magnetization can appear when a large amount of polarized xenon with the upper Zeeman level populated is placed inside a xenon-tuned coil. A better characterization of this type of phenomenon has been undertaken in our laboratory and will be reported elsewhere.

Acknowledgments

Prof. Jean Jeener, Prof. Maurice Goldman, Dr. Pierre-Jean Nacher and Dr. Geneviève Tastevin are greatly acknowledged for helpful comments. We thank the ‘Conseil général de l'Essonne’ for financial support (ASTRE program). This research program is financially supported by the French Ministry of Research (ANR BLAN07-2_193759).