1 Introduction

The coordination chemistry of cyanide ligands with transition metal ions has been studied extensively for many years [1]. Spectacular results were achieved in the field of molecular magnetism [2] and photomagnetism [3]. Cyanide chemistry is particularly attractive since the ambivalent ligand builds stable and inert cyanidometalate complexes [M(CN)m]n−, then used as molecular building blocks for the preparation of bimetallic molecules and networks, when combined with metallic complexes M′L. The charge of the precursors and the nature of the ligand L determine the stoichiometry and tune the molecular and crystallographic structures of the resulting compounds. We focus here on octacyanidometalates [4] [M(CN)8]n− and on their magnetic properties, that our groups explore for some years. We omit the exciting photomagnetic properties (for recent works cf. Ref. [5] and references quoted therein). In the field of molecular magnetism, the electronic structure of the octacyanidometalate is of the utmost importance: the systems built from MoIV and WIV (d2 electronic configuration, spin zero), present no interaction with the magnetic neighbours; they behave as simple paramagnets, whatever their dimensionality may be [6]. Instead, when combining paramagnetic [MIV/V(CN)8]4−/3− precursors (MIV = Nb; MV = MoV, WV, d1 electronic configuration, spin 1/2) [7,8] with M′II divalent transition metal ions, a wealth of systems are found ranging from polynuclear clusters [7a–d], including high spin ground state M′II9[MV(CN)8]6 [7e–g] to two- and three-dimensional magnets [7h–j]. Symmetry and topology determine the interaction between paramagnetic nearest neighbours with localized electrons [1b,7f]: even if the crystallographic structures are often complex and if the analysis is not easy [7f], overlap between singly occupied molecular orbitals leads to an antiferromagnetic interaction whereas orthogonality leads to ferromagnetic exchange.

We would like to demonstrate that one unpaired electron, well located, can dramatically change the magnetic behaviour of octacyanido-based networks presenting isostructural three-dimensional structures.

First, one of the condition to get isostructural systems is to choose precursors [MIV(CN)8]n− having the same charge n−. In polar solvents, neutral entities precipitate and we can expect that tetravalent niobium, molybdenum and tungsten octacyanido units [MIV(CN)8]4− combined with labile hexaaquamanganese(II) ions (d5 electronic configuration, spin 5/2) can give rise to insoluble neutral MIVMnII2 networks. Second, we need to choose precursors [MIV(CN)8]4− with different MIV electronic structures. Indeed, the octacyanidoniobiate [NbIV(CN)8]4− (NbIV, d1 electronic configuration, spin 1/2) [8] is a paramagnetic complex, whereas the analogous precursors [MIV(CN)8]4− (MIV = MoIV, WIV, d2 electronic configuration, spin zero) are diamagnetic. Then, it can be foreseen that in NbIVMnII2, the wave function of the unpaired d electron of the niobium will overlap with the ones of the five d electrons of the MnII ion so that antiferromagnetic exchange interactions between these spin carriers appear, leading to an NbIVMnII2 ferrimagnet. Meanwhile, MoIVMnII2 and WIVMnII2 are foreseen to be simple paramagnetic solids.

2 Results and discussion

2.1 Crystal structures of [MIV{(μ-CN)4MnII(H2O)2}2·4H2O]n (MIV = NbIV (1); MoIV (2) and WIV (3))

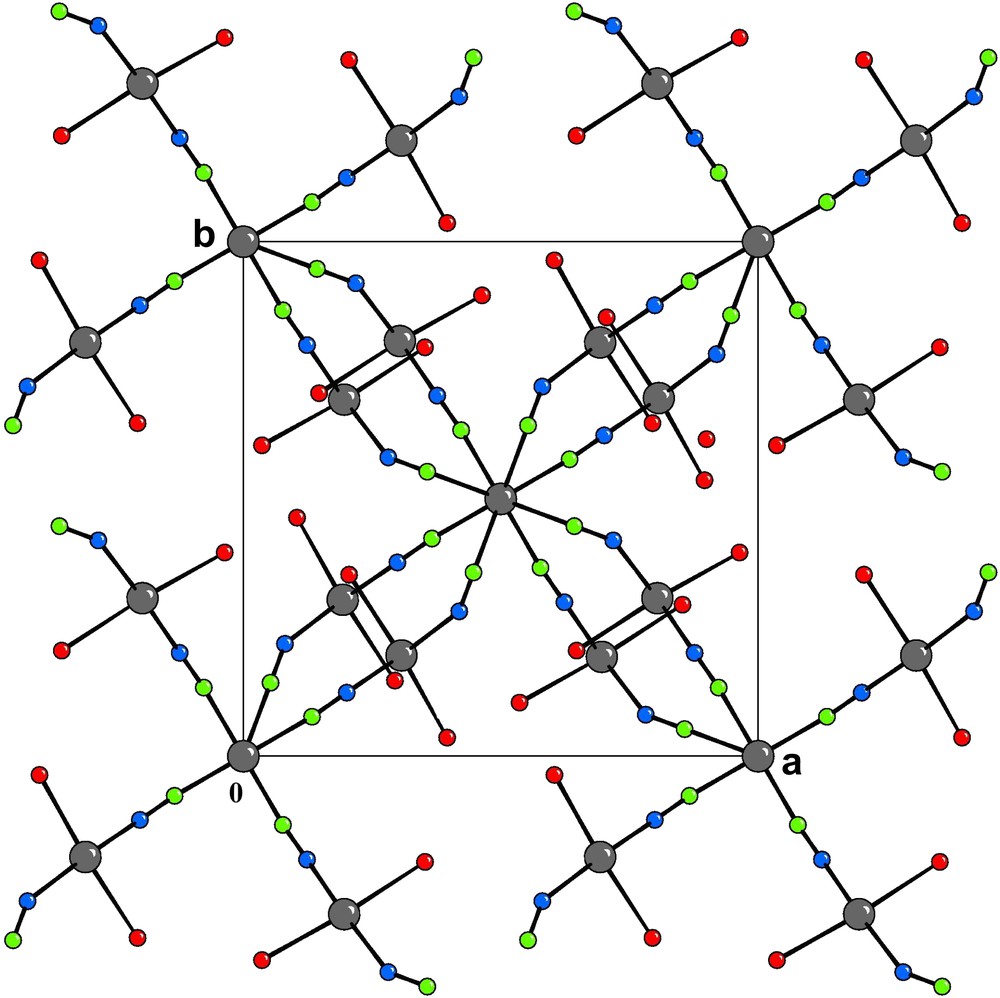

The three bimetallic, three-dimensional networks 1–3 are isostructural and crystallize in the tetragonal space group I4/m. Crystallographic data and selected bond distances and angles for 1–3 are given in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. The MIV ions and MnII ions are alternately linked through μ-cyanido ligands in a 1:2 ratio. The NbIV and MnII coordination spheres of 1 are shown as ORTEP drawing in Fig. 1. The [001] projection of the crystal structure of 1 is shown in Fig. 2. The MIV ion is surrounded by eight carbon atoms from μ-cyanido ligands in approximately square antiprismatic coordination. A fourfold rotation axis is passing through the MIV center. The coordination around the MnII ion is a slightly distorted octahedron: four nitrogen atoms from μ-cyanido ligands bind in equatorial positions whereas the axial positions are occupied by oxygen atoms from two water molecules. A mirror plane is passing through the MnII ion and the two oxygen atoms. The average bond distances (in Å, (1)/(2)/(3)) Mn–N (2.222/2.203/2.22) and Mn–O (2.186/2.16/2.20) are similar in the three compounds. Similar conclusions can be drawn for C–N distances (in Å, (1)/(2)/(3), 1.137/1.13/1.14) in [MIV(CN)8]. The only significant difference between 1 and 3 is related to the M–C bond distances (in Å), Nb–C (2.248), Mo–C (2.157), W–C (2.17). The Nb–C distances are slightly longer than those of Mo–C or W–C. Such trend was previously observed [7d–e]. The bond angles M–C1–N1 (in °, (1)/(2)/(3), 176.1/176.5/175.5) and M–C2–N2 (177.1/176.8/179.1) deviate only slightly from linearity, whereas the bond angles Mn–N1–C1 (166.6/166.2/164.6) and Mn–N2–C2 (154.1/155.0/153.1) are much less than 180°, as found in other μ-cyanido-bridged compounds [3–6]. The shortest distance between the MIV and MnII ions across the μ-cyanido bridge is 5.57 Å in 1, 5.49 Å in 2 and 5.51 Å in 3. These distances and angles are similar to those found in other [MIV(CN)8]/MII compounds [5,6]. We would like to point out that our crystallographic results are a very clean and simple demonstration of the structural trends usually observed in the periodic table: (i) contraction of the atomic radii when increasing Z in the same line [from Nb to Mo, in Å: Nb–C (2.248), Mo–C (2.157)] thanks to the increase of the effective atomic number Zeff (due to a reduced screening of the valence electrons of the same valence shell); (ii) moderate increase of the atomic radii in the same column when going to 4d to 5d elements [from Mo to W, in Å: Mo–C (2.157), W–C (2.17)] because of the “lanthanide contraction” due to the filling of the f orbitals before the 5d ones. These data are peculiarly reliable since for the three elements (Nb, Mo, W), the oxidation state (IV), the coordination number (8) and the symmetry of the coordination sphere (square antiprism) are exactly the same and make easy the comparison.

Summary of crystal, data collection and refinement details for 1, 2 and 3

| Compound | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Formula | NbMn2C8N8O8H16 | MoMn2C8N8O8H16 | WMn2C8N8O8H16 |

| Molecular weight | 555 | 558.1 | 646.0 |

| Crystallographic system | Tetragonal | Tetragonal | Tetragonal |

| Space group | I4/m | I4/m | I4/m |

| a, Å | 12.080(2) | 11.894(5) | 11.903(5) |

| b, Å | 12.080(2) | 11.894(5) | 11.903(5) |

| c, Å | 13.375(4) | 13.236(3) | 13.235(9) |

| α, ° | 90 | 90 | 90 |

| β, ° | 90 | 90 | 90 |

| γ, ° | 90 | 90 | 90° |

| V, Å3 | 1951.6(8) | 1873(1) | 1875(2) |

| Z | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| ρ, g cm−3 | 1.89 | 1.98 | 2.288 |

| μ, mm−1 | 18.3 | 19.7 | 7.58 |

| Temperature, K | 298 | 298 | 298 |

| Color, habit | Red, box | Yellow, box | Yellow-orange, box |

| Crystallographic size, mm3 | 0.2 × 0.2 × 0.4 | 0.4 × 0.4 × 0.35 | 0.2 × 0.2 × 0.4 |

| No. of reflections collection/unique | 1860/902 | 1935/1183 | 1988/902 |

| Final R1, wR2 | 0.0516, 0.050 | 0.081, 0.062 | 0.0564, 0.0487 |

Selected bond lengths (Å) and angles (°) for 1, 2 and 3

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| M(1)–C(1) | 2.243(4) | 2.157(7) | 2.18(1) |

| M(1)–C(2i) | 2.245(4) | 2.152(6) | 2.15(1) |

| Mn(1)–N(1) | 2.187(4) | 2.203(7) | 2.20(1) |

| Mn(1)–N(2) | 2.236(4) | 2.238(7) | 2.25(1) |

| Mn(1)–O(1) | 2.175(7) | 2.16(1) | 2.17(2) |

| Mn(1)–O(2) | 2.215(6) | 2.207(9) | 2.22(1) |

| C(1)–N(1) | 1.149(6) | 1.13(1) | 1.13(1) |

| C(2)–N(2) | 1.157(6) | 1.156(9) | 1.15(2) |

| C(1)–M(1)–C(1ii) | 73.7(1) | 72.5(2) | 73.1(3) |

| C(1)–M(1)–C(1iii) | 115.9(2) | 113.6(4) | 114.7(6) |

| C(1)–M(1)–C(2i) | 145.2(2) | 146.6(3) | 146.7(5) |

| C(1)–M(1)–C(2iv) | 139.3(2) | 138.6(3) | 138.1(5) |

| C(1)–M(1)–C(2v) | 75.4(2) | 76.2(3) | 75.1(4) |

| C(1)–M(1)–C(2vi) | 79.1(1) | 81.2(3) | 80.5(4) |

| C(2i)–M(1)–C(2v) | 115.1(2) | 113.9(4) | 115.1(6) |

| C(2i)–M(1)–C(2vi) | 73.3(1) | 72.7(2) | 73.2(3) |

| N(1)–Mn(1)–N(1vii) | 90.9(2) | 90.0(4) | 91.9(6) |

| N(1)–Mn(1)–N(2) | 176.5(2) | 176.5(3) | 175.3(4) |

| N(1)–Mn(1)–N(2vii) | 92.1(2) | 92.8(3) | 92.2(4) |

| N(1)–Mn(1)–O(1) | 85.2(2) | 84.7(3) | 86.4(5) |

| N(1)–Mn(1)–O(2) | 92.2(2) | 92.5(3) | 91.0(4) |

| N(2)–Mn(1)–N(2vii) | 84.8(2) | 84.3(4) | 83.5(6) |

| N(2)–Mn(1)–O(1) | 96.7(2) | 97.6(3) | 96.1(5) |

| N(2)–Mn(1)–O(2) | 85.9(2) | 85.3(3) | 86.7(4) |

| O(1)–Mn(1)–O(2) | 176.4(3) | 176.1(4) | 176.2(6) |

| M(1)–C(1)–N(1) | 176.2(5) | 176.5(8) | 175.5(11) |

| M(1viii)–C(2)–N(2) | 177.1(4) | 176.8(7) | 179.1(10) |

| Mn(1)–N(1)–C(1) | 166.6(4) | 166.2(7) | 164.6(10) |

| Mn(1)–N(2)–C(2) | 154.1(4) | 155.0(7) | 153.1(10) |

ORTEP representation of the NbIV and MnII coordination and numbering scheme for 1. The H atoms are omitted. Ellipsoids are drawn at 50% probability.

[001] Projection of the crystal structure of 1. The H atoms and the water molecules of crystallization are omitted for clarity.

2.2 Magnetic properties

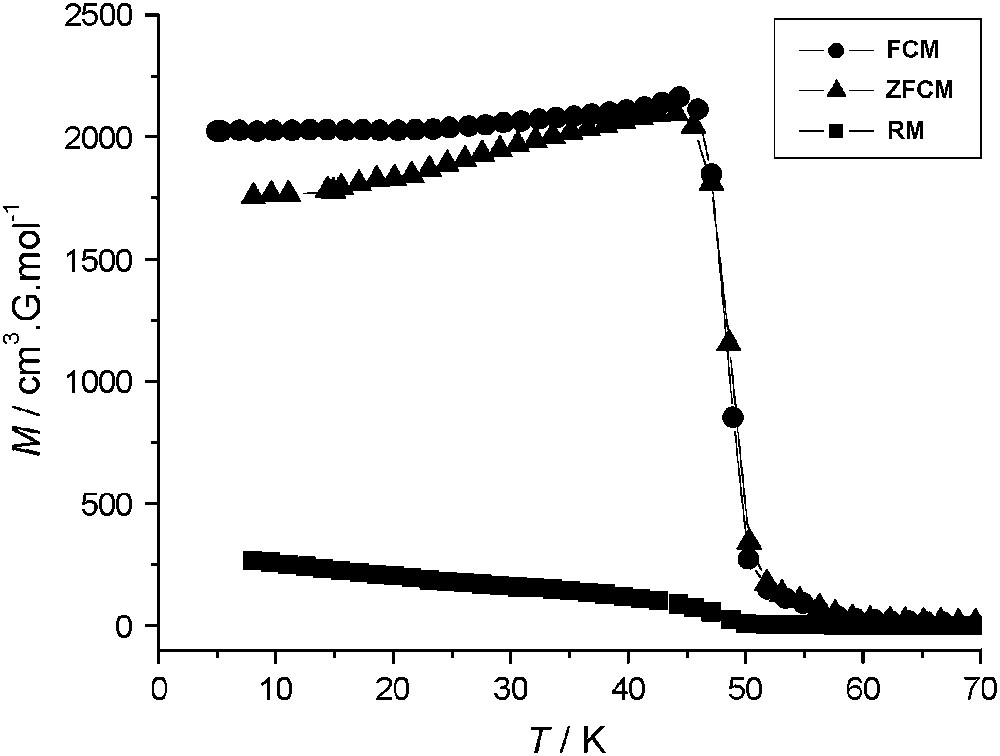

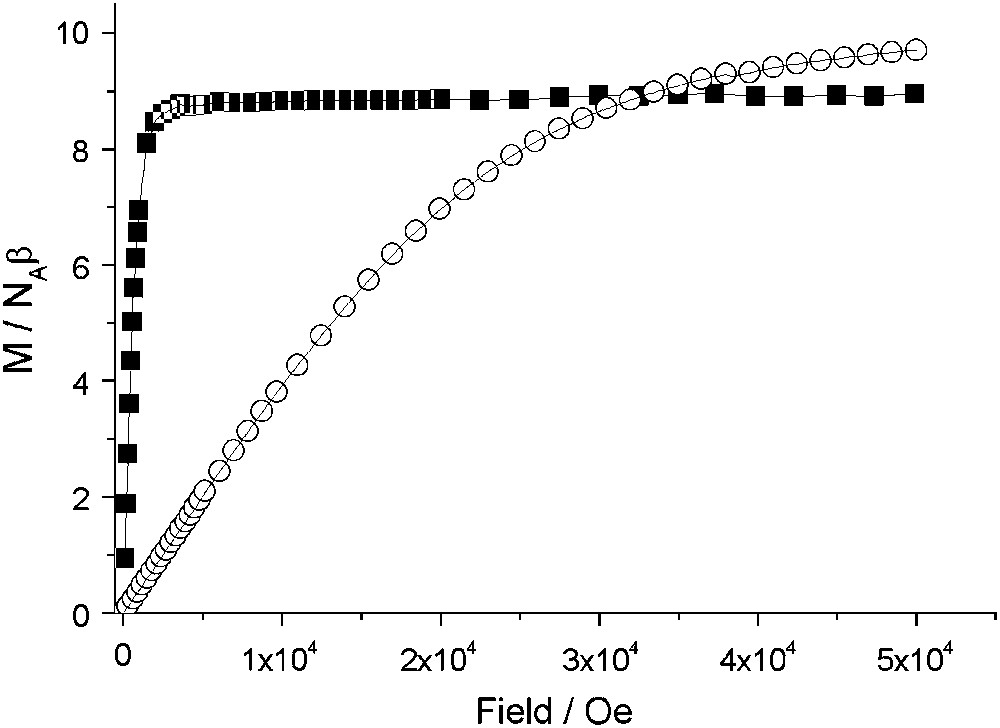

Variable-temperature magnetization data, collected for 1 with field-cooled (FCM), zero-field-cooled (ZFCM) and remnant (RM) measuring protocols, are shown in Fig. 3. The FCM shows a rapid increase when the temperature is lowered below 50 K, corresponding to the onset of a magnetically ordered phase. When the field is switched off at 5 K, a remnant magnetization (RM) is observed which vanished as the temperature is increased up to 50 K. The ZFCM curve merges with the FCM one at TC ≈ 47 K. The field dependence of the magnetization at T = 2 K for 1 and 2 is presented in Fig. 4. The magnetization curve shows a very high zero-field susceptibility and reaches a saturation value at 8.9 Bohr magnetrons per NbMn2 formula unit, close to the value of 9 (g = 2.0), expected for antiferromagnetically coupled NbIV and MnII ions. The magnetization data demonstrate a three-dimensional ferrimagnetic ordering in 1.

Thermal dependence of the magnetization (M vs T) for a polycrystalline sample of 1: FCM, cooling the sample with a 30 Oe applied magnetic field (●), ZFCM, cooling in zero field and warming in a 30 Oe applied field, (▴), and RM (■).

Field dependence of the magnetization, M/NAß, at 2 K for polycrystalline samples of 1 (■) and 2 (○) (NA is the Avogadro's constant and β the electron Bohr magneton).

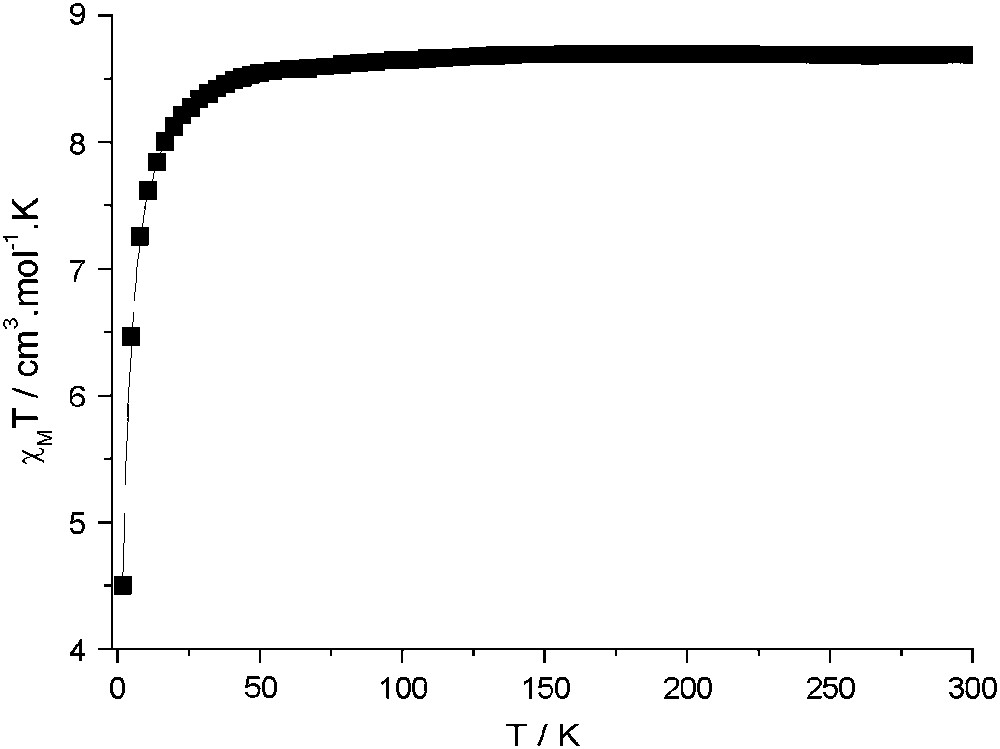

Instead, compounds 2 and 3 present no magnetic order. The magnetization of 2, in Fig. 4, in contrast to the high zero-field susceptibility shown by compound 1, shows the expected behaviour for practically uncoupled MnII ions, approaching 9.7 Bohr magnetrons per formula unit, at 50 kOe, close to the expected value of 10 (g = 2). Furthermore, the variable-temperature magnetic susceptibility data for 2–3 are very similar and consistent with two uncoupled MnII ions as shown in Fig. 5. At T > 50 K, χMT is constant with a 8.8 cm3 K mol−1 value, close to the χMT value of 8.75 cm3 K mol−1 calculated for two uncoupled MnII (S = 5/2, g = 2). Below 50 K, the χMT decrease points out the existence of a weak antiferromagnetic exchange interactions between next nearest MnII neighbours. The MnII–NC–M–CN–MnII pathway is rather long since the Mn–M–Mn distances are around 10.9 Å but the overlap between MnII magnetic orbitals is not strictly zero.

Plot of χMT vs T for a polycrystalline sample of 2. The magnetic susceptibility χM was measured under a 50 G magnetic field between 2 and 50 K, and 500 G between 50 and 300 K. Data for 3 (not shown) are practically superimposable.

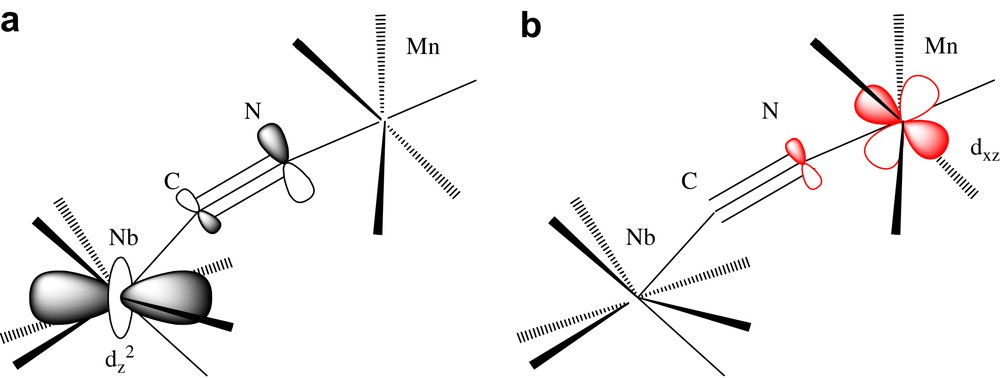

The antiferromagnetic interaction NbIV–MnII is simply explained by a “trough-bond” interaction, i.e. the overlap between the magnetic orbital centered on the 4dz2 orbital of niobium and some of the 3d orbitals of manganese [1b,7f]. The magnetic orbital (singly occupied molecular orbital) centered on the dz2 orbital of Nb(IV) is partially delocalized on the carbon and nitrogen (π symmetry) of the cyanide (Scheme 1a). Among the five magnetic orbitals centered on the d orbitals of manganese, at least one of them (xz for example, t2g type) is also delocalized on the nitrogen and the carbon of the cyanide (with the same π symmetry) (Scheme 1a). These two basis orbitals overlap to give two molecular orbitals in the complex Nb–Mn. For two electrons, the Kahn's model [J = 2 k + 4βS, where J is the coupling constant, energy difference between the singlet and the triplet, k is the exchange integral (>0), β is the resonance integral (<0), and S is the overlap integral] [9] allows to foresee an antiferromagnetic interaction (2k << |4βS|). Furthermore, for two metals located at ≈5.5 Å the ferromagnetic terms arising from the orthogonality of the dz2 niobium orbital with some of the manganese orbitals are weak and can be neglected.

The antiferromagnetic coupling between nearest neighbour spins with different values (NbIV, S = 1/2; MnII, S = 5/2) leads then to ferrimagnetism (↓↑) and to the observed long range ferrimagnetic order.

3 Experimental section

3.1 Materials

All solid reactants were reagent grade, purchased from Acros or Aldrich and used as-received. Absolute methanol was obtained over magnesium before use.

3.2 Syntheses

The precursors K4[M(CN)8]·2H2O (M = Mo, W) were made according to previously published procedures [10]. The precursor K4[Nb(CN)8]·2H2O was prepared using a procedure slightly modified compared to the literature [11]. In 25 mL of methanol was dissolved 20 g of NbCl5 under inert argon atmosphere using Schlenk technique. After the vigorous HCl evolution stopped, the light-yellow solution was diluted with an additional 50 mL of methanol. The resulting solution was electrochemically reduced on carbon electrodes for 24 h at a constant voltage of 35 V. After reduction, the green-brown solution was slowly added to a solution of 100 g KCN dissolved in 150 mL H2O, cooled in an ice/NaCl bath. The mixture was stirred for 1 h under cooling and for additional 24 h at ambient temperature. Brick red K5[NbIII(CN)8] precipitated by this time. After centrifugation, K5[NbIII(CN)8] was added under stirring to 100 mL of H2O and then 15 mL of a 10% aqueous solution of hydrogen peroxide were slowly added. Yellow K4[NbIV(CN)8]·2H2O precipitated by addition of methanol. The product was recrystallized from water/methanol. Yield ∼25%.

[NbIV{(μ-CN)4MnII(H2O)2}2·4H2O]n (1) was prepared by the addition, in the dark, of 0.4 mmol (197.2 mg) of K4[Nb(CN)8]·2H2O in 15 mL of H2O to 1.0 mmol (0.198 g) of MnCl2·4H2O in 15 mL of H2O (without stirring). The resultant yellow suspension was kept at 4 °C. After a few days, dark-red polyhedral crystals formed. The crystals were washed with a few small portions of distilled water and ethanol and dried in air. Calcd for 1: C, 17.3; H, 2.9; N, 20.2. Found: C, 17.2; H, 3.1; N, 20.1.

MoIV{(μ-CN)4MnII(H2O)2}2·4H2O]n (2) and [WIV{(μ-CN)4MnII(H2O)2}2·4H2O]n (3) were prepared by reacting aqueous solutions, in the dark, of MnCl2·4H2O and K4[Mo(CN)8]·2H2O for 2 or K4[W(CN)8]·2H2O for 3 by slow diffusion in an H-tube. After a few weeks, yellow-orange polyhedral crystals formed. The crystals were washed with a few small portions of distilled water and ethanol and dried in air. Calcd for 2: C, 17.2; H, 2.9; N, 20.1. Found: C, 17.1; H, 3.0; N, 20.0. Calcd for 3: C, 14.9; H, 2.5; N, 17.3. Found: C, 14.8; H, 2.9; N, 17.3.

3.3 Crystallographic data collection and structure determination

The determination of the unit cell parameters and the collection of intensity data for 1, 2 and 3 were made at 295 K on a Enraf Nonius CAD4 diffractometer using crystals of dimensions 0.2 × 0.2 × 0.4 mm3 (1), 0.4 × 0.4 × 0.35 mm3 (2) and 0.2 × 0.2 × 0.4 mm3 (3). Of the 902 (1), 1183 (2) and 902 (3) unique reflections, 838 (1), 856 (2) and 720 (3) with I > 3σ(I) were used to solve the structure with SHELXS-86 program [12]. Computations were performed by using PC versions of CRYSTALS [13]. Least-squares refinements of 68 (for 1), 67 (for 2) and 67 (for 3) parameters with approximation to the normal matrix were carried out by minimizing the function Σw(|Fo| − |Fc|)2, where Fo and Fc are the observed and calculated structure factors. Corrections were made for Lorentz and polarization effects. Empirical absorption corrections based on Ψ scan curves were applied. The models reached convergence with R = 0.0516 and Rw = 0.050 for 1, R = 0.081 and Rw = 0.062 for 2 and R = 0.0564 and Rw = 0.0487 for 3. The hydrogen atoms were not included in the refinement. All non-hydrogen atoms were refined anisotropically. The crystallographic data for 1, 2 and 3 are summarized in Table 1. Main bond lengths and angles are listed in Table 2.

3.4 Magnetic measurements

Magnetic susceptibility data of polycrystalline samples of 1, 2 and 3 were collected with an MPMS Quantum Design SQUID magnetometer (XL5S) in the temperature range 300–302 K. Pascal's constants were used for the diamagnetic corrections [14].

4 Conclusions

We have presented an example of isostructural octacyanidometalate-based three-dimensional bimetallic networks that present striking different magnetic properties, due to the presence of an unpaired electron on the octacyanidometalate (NbIV) or its absence (MoIV and WIV): (1), NbIVMnII2 is a ferrimagnet below TC = 47 K, whereas (2) (MoIVMnII2) and (3) (WIVMnII2) are simple paramagnets. Besides the amazing saga of magnetic Prussian blues [1b], the chemistry of octacyanidometalates is bringing new perspectives in molecular magnetism, including multifunctional materials [5].

Supporting information available. X-ray crystallographic files in CIF format for the structures of compounds 1, 2 and 3. This material has been sent to the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, 12 Union Road, Cambridge CB2 1EZ, UK (CCDC 679635–679637).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the TMR Programme from the European Union (Contract ERBFM-RXCT98-0181), the Magmanet network of Excellence, the European Science Foundation through the Molecular Magnets Programme and the Swiss National Science Foundation through Project No. 20-116003.