1 Introduction

The decomposition of organometallic precursors under appropriate conditions represents an elegant synthetic methodology to give metallic nanoparticles with a well-defined composition and controlled morphology [1], key aspects for their subsequent applications in particular for catalysis [2]. Nanoparticles dispersed in solution can agglomerate because of thermodynamic reasons [3], and also can leach molecular species promoted by solvent, ligands or other reaction parameters [4]. The discussion about the catalyst nature, using metallic nanoparticles as catalytic precursors, has been recently reviewed [5].

In the present paper, we focus on the comprehension of the interaction of the stabilizers with the metallic surface to rationalize the catalytic behaviour observed. In particular, the results obtained in palladium-catalyzed enantioselective allylic alkylation [6] and Suzuki C–C cross-coupling in ionic liquid [7,8], have led us to consider the interaction of the stabilizers at the metallic surface. These studies have been mainly carried out by means of NMR spectroscopy [9,10].

2 Metallic nanoparticles in organic solvents

The use of metal nanoparticles for catalytic transformations of organic substrates is a growing area [2]. Metal nanoparticles have been proved to be efficient and selective catalysts for reactions which are catalyzed by molecular complexes such as olefins hydrogenation or C–C couplings, for example, but also for reactions which are not or poorly catalyzed by molecular species such as arenes hydrogenation [11]. Despite impressive progress in enantioselective catalysis [12], only very few colloidal systems have been found to exhibit an interesting activity, namely Pt and Pd nanocatalysts containing cinchonidine as stabilizer for the hydrogenation of ethyl pyruvate [13], Pd/BINAP nanoparticles for styrene hydrosilylation [14] or Pd-catalyzed kinetic resolution of racemic substrates in allylic alkylation (see below).

2.1 Pd nanoparticles catalyzed allylic alkylation: molecular vs. surface behaviour

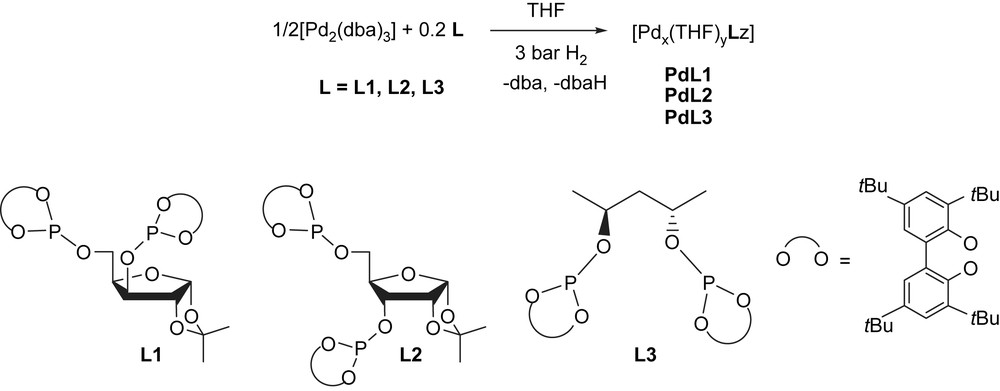

PdNPs were obtained from decomposition of [Pd2(dba)3] in THF under hydrogen atmosphere and in presence of the appropriated ligand (Pd/L = 1/0.2) (Scheme 1) [6]. The ligands involved, chiral diphosphites, tagged to functionalized carbohydrate (L1 and L2) [15], and to 2,4-disubstitued pentyl (L3) [16] skeletons, were used in order to study the stereochemistry and backbone influences in the stabilization of nanoparticles and its effect in catalysis.

Synthesis of palladium nanoparticles PdL1–PdL3.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) revealed a similar size for the colloids PdL1, PdL2 and PdL3 with ca. 4 nm mean diameter; PdL1 and PdL2 show a good dispersion, in contrast to PdL3 (Fig. 1).

Transmission electron micrograph of PdL1 (left), PdL2 (middle) and PdL3 (right).

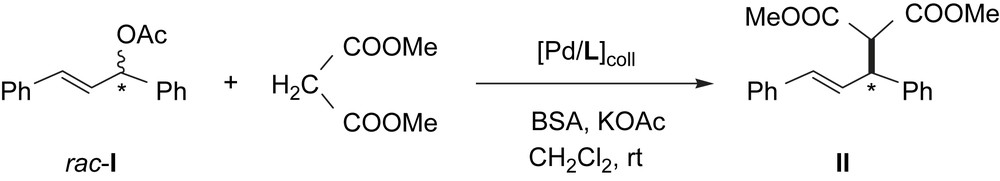

PdL1–PdL3 were tested as catalysts for the asymmetric allylic alkylation reaction of the racemic substrate rac-3-acetoxy-1,3-diphenyl-1-propene (rac-I) using dimethyl malonate as nucleophile under basic Trost conditions [17]. (Scheme 2).

PdL catalyzed asymmetric allylic alkylation of rac-3-acetoxy-1,3-diphenyl-1-propene (rac-I) with dimethyl malonate.

No reaction was observed in the absence of added ligand (entries 1, 3 and 5, Table 1). However, extra addition of the corresponding ligand (entries 2, 4 and 6, Table 1) led to active systems. This fact proves that the presence of free ligand prevents the formation of catalytically inactive heterogeneous species (formed under catalytic conditions by PdNPs agglomeration in presence of low ligand amount). PdL1 induces excellent enantioselectivity in the alkylation product, but the reaction practically stops after 55% conversion (entry 2, Table 1). According to the enantiomeric excess observed for the residual substrate, the (R)-I reacts faster than the (S)-I in contrast to the catalytic behaviour observed for the corresponding molecular catalyst (entry 1, Table 2). On the contrary, PdL2 gave the product II after a long reaction time without the induction of enantioselectivity (entry 4, Table 1), analogously to the lack of selectivity observed for the corresponding molecular catalyst (entry 2, Table 2); this fact can be probably due to the PdL2 decomposition giving molecular species. PdL3 led to a high activity and selectivity (entry 6, Table 1), comparable to that observed when the corresponding molecular catalyst was used (entry 3, Table 2).

Asymmetric allylic alkylation of rac-I catalyzed by PdNPs, PdL1-PdL3.a

| Entry | PdL/L | Time (h) | Conv. (%)b | ee I (%)c | ee II (%)c |

| 1 | PdL1/– | 168 | 0 | 0 | – |

| 2 | PdL1/L1 | 10 | 50 | 70(S) | 96 (S) |

| 24 | 56 | 89 (S) | 97 (S) | ||

| 3 | PdL2/– | 168 | 0 | 0 | – |

| 4 | PdL2/L2 | 24 | 0 | 0 | – |

| 48 | 100 | – | 11 (S) | ||

| 5 | PdL3/– | 168 | 0 | – | – |

| 6 | PdL3/L3 | 3 | 68 | 94 (S) | 92 (S) |

| 24 | 88 | nd | 90 (S) |

a Results from duplicated experiments; Pd/rac-I/dimethyl malonate/BSA = 1/100/300/300. Pd/Lstabilizer/Lfree ligand = 1/0.2/1.05.

b Conversions based on the substrate I and determined by 1H NMR.

c Determined by HPLC on a Chiralcel-OD column.

Asymmetric allylic alkylation of rac-I catalyzed by molecular palladium systems containing chiral ligands L1–L3.a

| Entry | L | Time (h) | Conv. (%)b | ee I (%)c | ee II (%)c |

| 1 | L1 | 1.5 | 83 | nd | 90 (S) |

| 2 | L2 | 1.5 | 80 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | L3 | 0.15 | 100 | – | 94 (S) |

a Results from duplicated experiments; Pd/rac-I/dimethyl malonate/BSA = 1/100/300/300. Catalytic precursor generated in situ from [PdCl(C3H5)]2 and the appropriated ligand (Pd/L = 1/1.25).

b Conversions based on the substrate I and determined by 1H NMR.

c Determined by HPLC on a Chiralcel-OD column.

Looking for the origin of the kinetic resolution observed for PdL1 catalytic system, the allylic alkylation of rac-I was carried out using the corresponding molecular system as catalytic precursor at different Pd/substrate ratios (Table 3).

Asymmetric allylic alkylation of rac-I catalyzed by molecular palladium systems containing chiral ligands L1 and L3, at different Pd concentrations.a

| Entry | L | Pd/I | Time (h) | Conv. (%)b | ee I (%)c | ee II (%)c |

| 1 | L1 | 1/100 | 1.5 | 83 | 0 | 90 (S) |

| 2 | L1 | 1/2000 | 3 | 43 | 26 (S) | 90 (S) |

| 3 | L1 | 1/10,000 | 24 | 72 | 43 (S) | 90 (S) |

| 4 | L3 | 1/100 | 0.15 | 100 | – | 94 (S) |

| 5 | L3 | 1/2500 | 0.5 | 88 | nd | 91 (S) |

a Results from duplicated experiments; rac-I/dimethyl malonate/BSA = 1/3/3. Catalytic precursor generated in situ from [PdCl(C3H5)]2 and the appropriated ligand (Pd/L = 1/1.25).

b Conversions based on the substrate I and determined by 1H NMR.

c Determined by HPLC on a Chiralcel-OD column.

PdL1 catalyst behaves differently than the corresponding molecular system Pd/L1 even at low Pd/I ratios (up to 1/10,000: entry 3, Table 3) attesting to the absence of molecular species. In addition, the reusing of the catalytic phase (up to three times) led to a conversion around 50–60% with high selectivity for the substrate as well as for the product. The high activity and selectivity obtained for both colloidal (PdL3) and molecular (Pd/L3) catalysts do not provide any evidence about the nature of the catalyst.

In order to corroborate the robustness of the PdL1 catalytic system, free ligand L2 (and no L1) was added to the catalytic reaction mixture (ratio Pd/L1/L2 = 1/0.2/1.05) (Table 4). In this case, the catalyst was completely inactive (entry 1, Table 4), analogously to the PdL1 system without added ligand (entry 1, Table 1). On the contrary, the “cross-system” formed by PdL2 nanoparticles and free ligand L1, exhibits a high activity and enantioselectivity (entry 2, Table 4), similar to that observed for molecular system Pd/L1 (entry 1, Table 2), pointing to the decomposition of PdL2 nanoparticles to give molecular species.

Asymmetric allylic alkylation of rac-I catalyzed by PdL1 and PdL2 colloidal systems.a

| Entry | PdL/L | Time (h) | Conv. (%)b | ee I (%)c | ee II (%)c |

| 1 | PdL1/L2 | 24 | 0 | 0 | – |

| 2 | PdL2/L1 | 24 | 100 | – | 89 (S) |

a Results from duplicated experiments; Pd/rac-I/dimethyl malonate/BSA = 1/100/300/300. Pd/Lstabilizer/Lfree ligand = 1/0.2/1.05.

b Conversions based on the substrate I and determined by 1H NMR.

c Determined by HPLC on a Chiralcel-OD column.

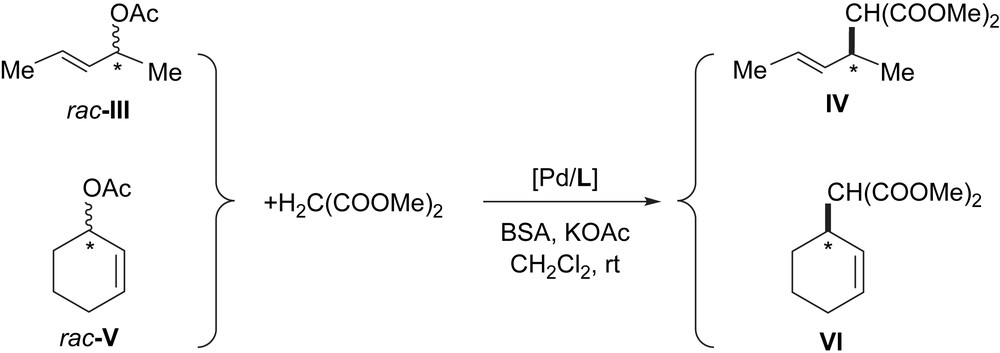

The allylic alkylation was also studied using alkyl-substituted allyl substrates, rac-3-acetoxy-1,3-dimethyl-1-propene (rac-III) and rac-3-acetoxy-1-cyclohexene (rac-V), with both molecular and colloidal systems (Scheme 3).

Pd-catalyzed allylic alkylation of rac-III and rac-V (L = L1, L3).

The robust PdL1 system was completely inactive when rac-III was used under the same conditions as those described for the phenylallyl acetate rac-I (entry 2, Table 1). In addition, the colloidal systems PdL1 and PdL3 were also inactive when rac-V was involved. However, the corresponding molecular catalytic systems were highly active and selective (with rac-III and L1: 45% conversion after 3 h reaction with 50% ee of (R)-IV; with rac-V after 30 min with L1 or L3 100–73% conversion, with 22–73% ee of (S)-VI respectively). Therefore the inactivity of PdL1 and PdL3, even a long reaction time (up to 72 h), shows both their stability under the catalytic conditions used and their low affinity for alkyl-substituted allyl substrates.

In summary, the catalytic behaviour observed demonstrates that nanocatalysts are more sensitive to the tuning between the metallic surface, stabilizer (ligand) and substrate than the corresponding molecular catalytic systems. This specificity reveals the importance to studying the coordination chemistry at the metallic surface in liquid phase. In the next section, the interaction of aromatic groups with the metallic surface is explored.

2.2 A coordination chemistry study: π-interactions at ruthenium surface

Ligands commonly used for the stabilization of metallic nanoparticles possess functional groups, such as carboxylic acids, thiols or amines, proving that the heterodonor atom interacts by σ-coordination with the metallic surface [18]. Techniques like UV–vis, [18a] IR or NMR spectroscopy are appropriated tools to elucidate this kind of interaction. For instance, Au–C and Au–S σ-bonds at gold nanoparticles surface involving decylbenzene [18b] and cystein [18c] respectively, have been evidenced by means of FTIR spectroscopy as well as PPh3–Ag contacts by Raman spectroscopy [19]. This spectroscopy has been also used to study ligand exchanges with CO at metallic surfaces [20]. A dynamic process has been also described for ruthenium nanoparticles stabilized by hexadecylamine (HDA) by means of 13C NMR [18d]. When a low quantity of HDA is added to a suspension of RuNPs, the signals corresponding to the carbon atoms in the α, β, γ positions and the methyl group are not observed pointing to a direct interaction of both the methyl and amino groups with the metal surface atoms, but the addition of an extra ligand results in the displacement of the methyl group weakly bonded at the metallic surface. In spite of this, coordination studies by means of 1H NMR spectroscopy are scarce. To the best of our knowledge, only the interaction of a carbene ligand at Ru nanoparticles surface has been recently evidenced by this technique [21].

With the purpose of elucidating the π-coordination between an organic fragment and the metallic surface, 4-(3-phenylpropyl)-pyridine (L4) was chosen for its simple structure containing a pyridine group, which, upon σ-coordination, can favour the phenyl flat approach to the metallic surface. To facilitate the use of the NMR spectroscopy, ruthenium was selected because of its absence of Knight shift.

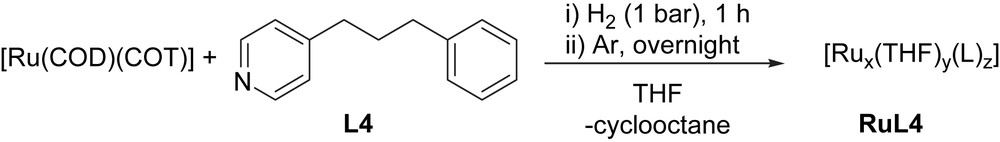

Ruthenium nanoparticles (RuNPs) were prepared by decomposition of [Ru(COD)(COT)] (COD = 1,5-cyclooctadiene; COT = 1,3,5-cyclooctatriene), in the presence of L4 under hydrogen atmosphere, based on previously reported methodology (Scheme 4) [1].

Synthesis of RuNPs stabilized by 4-(3-phenylpropyl)-pyridine, RuL4.

Reproducible syntheses led to the formation of small and homogeneously dispersed nanoparticles showing a quite narrow size distribution (mean diameter of 1.3 nm) (Fig. 2).

TEM micrograph of RuL4 and size distribution histogram (mean diameter = 1.27 ± 0.33 nm for 696 particles).

The influence of the phenyl group in the stabilization of these particles is crucial. Big and agglomerated particles were obtained when pyridine was used as stabilizer, in agreement with the reported data concerning gold particles containing pyridine [22]. The presence of the propyl-phenyl moiety in the ligand favours the dispersion of particles due to the phenyl interaction at the metallic surface.

The infrared spectroscopy permitted us to confirm qualitatively the presence of the ligand (C–N, C–C and C–H absorptions). In particular no bands were observed in the far IR region (400–200 cm−1) suggesting the absence of Ru–N or RuO covalent bonds [23]. However Raman spectroscopy proved the presence of RuO (500 and 610 cm−1) because the material oxidizes under low energy irradiation (green laser).

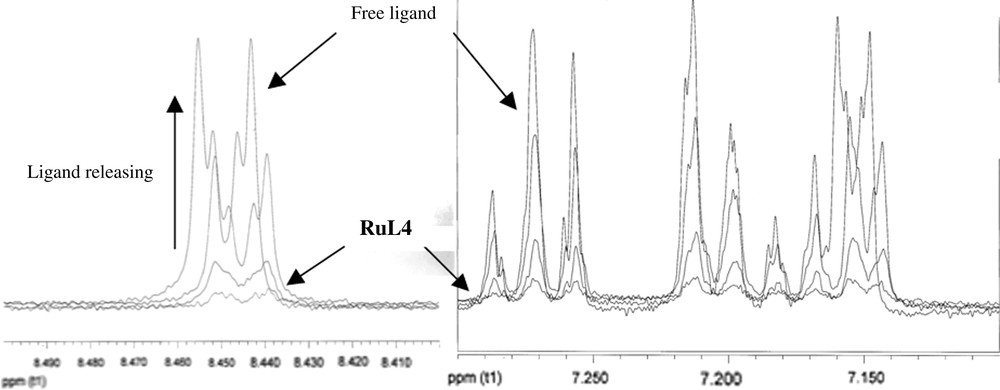

In relation to the characterization by means of NMR spectroscopy, no resonances in the 1H NMR spectrum were observed for RuL4 dispersed in THF-d8, suggesting that the ligand is close to the metallic surface. In addition, no aromatic signals were either observed in the 13C MAS NMR spectrum. In order to rule out the hydrogenation of the ligand promoted by the ruthenium nanoparticles, a ligand exchange reaction with dodecanethiol was made, taking advantage of the known affinity of the sulphur group for metal surfaces [13]. A quantitative release of L4 (monitored by 1H NMR) was achieved after 24 h of reaction (Fig. 3). Other tests were carried out using CO instead of dodecanethiol, but the releasing of L4 was slower than that observed with the thiol derivative (more than one week under 2 bar carbon monoxide pressure). These facts reveal (i) the presence of the ligand at the surface of the particle and (ii) a strong interaction of the ligand with the metallic surface.

1H NMR spectra (aromatic region, 500 MHz, THF-d8, 298 K) corresponding to the L4/dodecanethiol exchange monitoring for RuL4. Left: signal at ca. 8.5 ppm corresponds to pyridinyl ortho protons; right: signals at 7.1–7.3 ppm correspond to the other aromatic protons.

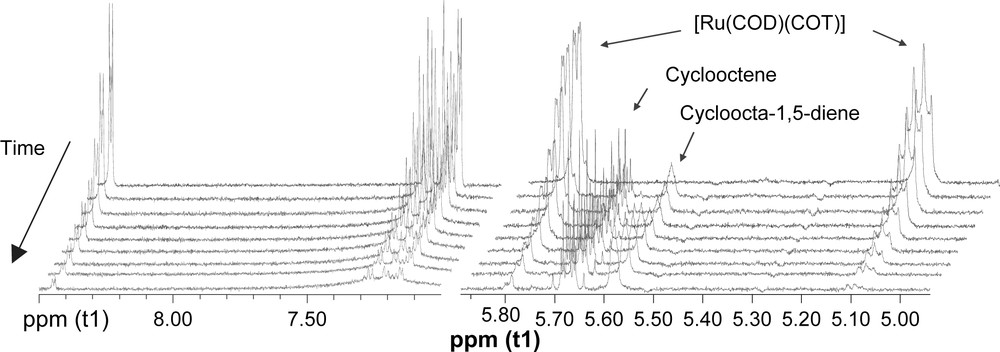

The ligand coordination to RuL4 was studied by 1H NMR monitoring under preparative conditions, using undecane as quantitative internal reference. The disappearance of [Ru(COD)(COT)] signals and appearance of resonances corresponding to COD, cyclooctene and cyclooctane were observed, without detecting new defined peaks. Moreover, ligand signal broadening was observed after a few minutes under hydrogen pressure (Fig. 4). This phenomenon could be related to the interaction of the ligand with the metallic surface as observed for gold nanoparticles [19].

1H NMR (500 MHz, 298 K, THF-d8) monitoring of RuL4 formation: left, aromatic region (9–7 ppm); right olefinic region (6–5 ppm).

TEM micrographs corresponding to samples taken during the NMR monitoring, revealed the extremely fast formation of ruthenium nanoparticles, showing a mean diameter close to that observed under preparative conditions.

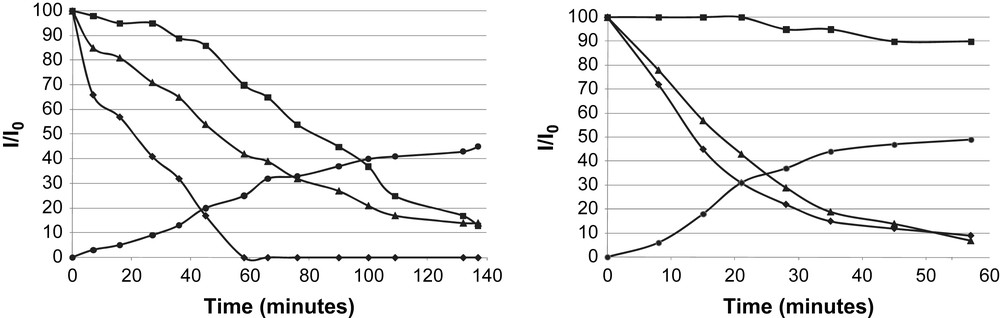

From the kinetic curves using a Ru/L4 ratio = 1/0.2, the signal broadening was faster for the ortho-pyridinyl protons than that observed for the other aromatic ones (Fig. 5a). Then, the ligand seems to interact with the metallic surface by the N atom of pyridinyl group in a first step, moving on to a π-interaction with the surface, consistent with the absence of Ru–N absorption band in the IR spectrum.

Relative 1H NMR signal integral vs. time corresponding to RuL4 formation (■ H phenyl; ▴ [Ru(COD)(COT)]; H ortho pyridine; ● cyclooctane): a) Ru/L4 = 1/0.2 (left); b) Ru/L4 = 1/1.7 (right).

In order to prove the σ-bond between nitrogen and ruthenium, a larger amount of ligand was used (Ru/L4 = 1/1.7). In this case, the relative signal integral of aromatic protons (other than ones in ortho position for pyridine moiety) appears nearly constant with time, pointing to interaction of ruthenium with the nitrogen atom analogously to the phenomenon observed with ruthenium nanoparticles stabilized by HDA [18d]. In summary, we have proved the strong interaction of aromatic groups at the metallic surface by π-coordination of the pyridinyl and phenyl group at the particle surface. This fact can be related to the catalytic behaviour observed when substrates containing aromatic groups are used in the same way, as discussed above (see above Section 2.1).

3 Palladium nanocatalysts in ionic liquids

The main advantages to use ionic liquids (ILs) as (co)solvents in comparison to organic solvents are to make easier the product separation and the catalyst recovery by its immobilization in the ionic liquid phase [24,25]. In this area, the mostly fully described system is ligand-free palladium acetate, in particular in imidazolium ILs [26,27]. ILs are efficient stabilizers of metal nanoclusters by electrostatic interactions avoiding the formation of bulk metal [28]. Among reaction patterns to compare catalytic systems, Heck [29] and Suzuki [30] couplings are often mentioned. From a mechanistic point of view, Hu et al. proposed that for the Suzuki coupling catalyzed by starting Pd nanoparticles, discrete Pd(II) species are involved, regenerating Pd(0) nanoparticles after the reductive elimination [31]; analogously, Dupont et al. suggested that Pd nanoparticle precursors behave as a reservoir of molecular palladium species, which are the true catalytic species in Heck reactions [32]. With the aim of putting more light in the nature of active catalytically species involved in the Pd-catalyzed Suzuki C–C coupling, we have studied ligand-free palladium systems [7], as well as those containing ligands as co-stabilizers [8].

3.1 C–C Suzuki cross-couplings in [BMI][PF6]

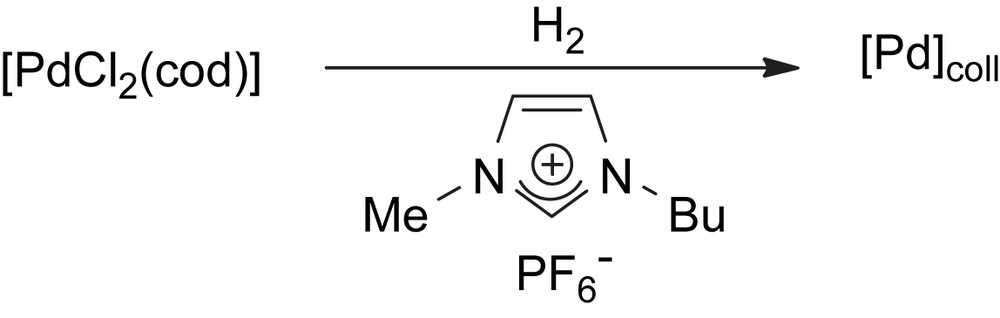

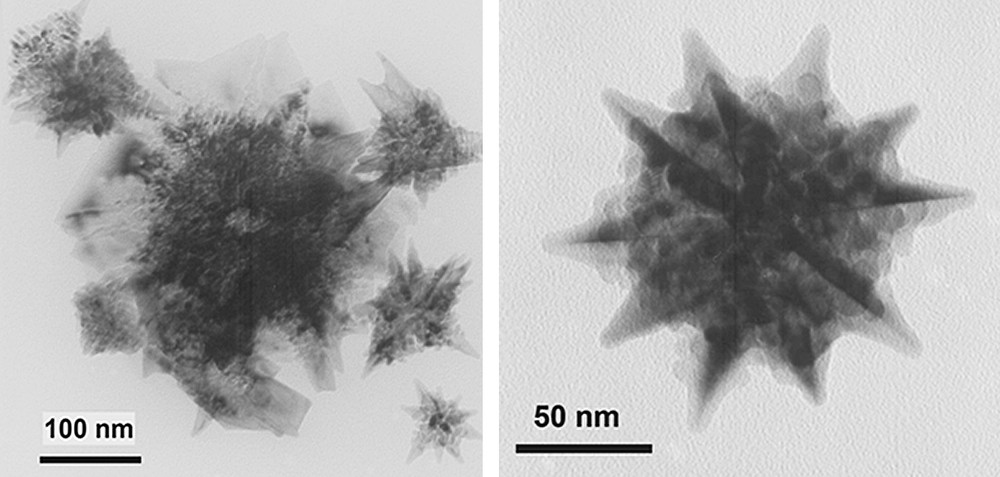

Palladium nanoparticles were prepared in [BMI][PF6] by decomposition of [PdCl2(cod)] under hydrogen atmosphere (Scheme 5). TEM analyses of these particles dispersed in the IL (Fig. 6) show star-like shaped inter-particle organizations. The “branches” are constituted by small nanoclusters, showing a diameter between 6 and 8 nm.

Synthesis of palladium nanoparticles from [PdCl2(cod)] in [BMI][PF6].

TEM micrographs of palladium nanoparticles from [PdCl2(cod)] stabilized in [BMI][PF6].

The electrostatic stabilization of palladium nanoparticles by the ionic liquid depends on the palladium precursor because no super-structures were observed for nanoparticles formed from PdCl2 salt or from [Pd2(dba)3·CHCl3], giving in these two latter cases quite well-dispersed material formed by nanoparticles with a mean size ca. 7 nm.

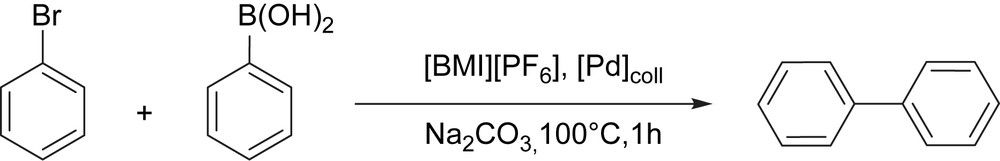

Preformed Pd nanoparticles in [BMI][PF6] were used as catalytic precursor for Suzuki C–C coupling between bromobenzene and phenylboronic acid (Scheme 6) [24]. For palladium nanoparticles prepared from [PdCl2(cod)], after 1 h at 100 °C using 0.25 mol% of palladium (based on the starting precursor), the total conversion of bromobenzene was reached, isolating 92% of biphenyl.

Suzuki C–C coupling in [BMI][PF6].

The palladium content in biphenyl isolated (determined by ICP–MS) is in the range of 3–5 ppm. Under these conditions, iodobenzene was also activated, but not chlorobenzene. After an appropriate work-up, IL phase containing the catalyst was reused up to 10 times, observing a slight diminution in yield after the eighth run (Fig. 7). The palladium content in the biphenyl isolated after each recycling lowered, reaching 200 ppm in the last two runs.

Recycling of the ionic liquid phase.

It is noteworthy that both [PdCl2(cod)] as molecular catalytic precursor and palladium powder as heterogeneous catalyst, were not active, even at high concentration of catalyst (2.5 mol%).

Nanoparticles derived from PdCl2 were less active than those from [PdCl2(cod)] and its catalyst reuse led to an isolated yield of 53% after the second run, showing that the reusability of this system is less efficient. However, nanoparticles formed from [Pd2(dba)3·CHCl3] were not active, probably due to the presence of organic stabilizers hindering the substrate–metal contact.

As a result, the formation of nanoparticles is necessary to have a performant catalytic system in this Suzuki C–C coupling and the organization of nanoparticles in IL, observed by TEM analysis, is related to the catalytic activity.

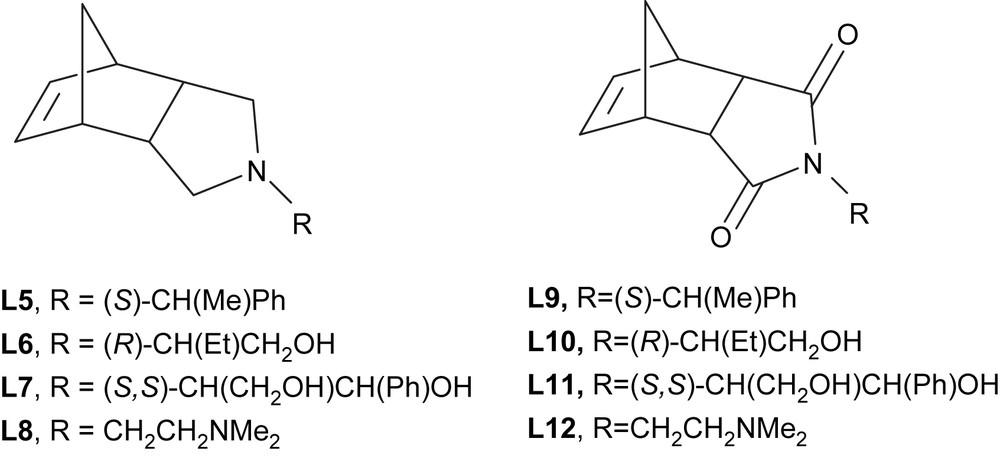

In order to develop selective catalytic reactions in ILs, we looked for functionalized ligands with aromatic-free backbones in order to favour the electrostatic stabilization of the palladium nanoparticles by ILs. Imide derivatives of endo-norbornene were prepared by condensation of endo-norborn-5-ene-2,3-dicarboxylic anhydride with the appropriated primary amine based on the methodology described in the literature [33]. The corresponding amines were obtained by reduction of carbonyl groups with LiAlH4 [34], from the isolated imides (Fig. 8). These products were obtained in good yields (68–95%).

Amines (L5–L8) and imides (L9–L12) ligands derived from endo-carbic anhydride.

Suzuki cross-coupling reactions between substituted bromobenzene and phenylboronic acid derivatives [35], were carried out using molecular palladium catalysts containing amines (L5–L8) and imides (L9–L12). A catalytic precursor was generated in situ from palladium acetate and the appropriated ligand. In order to simplify the following discussion, only bromobenzene and phenylboronic acid will be considered.

The best results (80–98% isolated yield in biphenyl) were obtained using the two amines containing hydroxy groups (L6 and L7). The corresponding imides (L10 and L11) were less efficient with yields in the 34–48% range, because of the loss of the electron-donor character of the heterocyclic nitrogen atom.

Mono- and bis-amine (L5 and L8) palladium systems were inactive. Their ionic liquid phase remained yellow in contrast to the black colour observed for the other systems. This fact points to the formation of stable palladium(II) complexes which do not evolve towards Pd(0) active species.

Under optimized conditions, (Pd/L/bromobenzene/phenylboronic acid/sodium carbonate = 1/1.2/100/120/250 mmol), the same reaction was tested in organic solvent (toluene) (Table 5). With amine L7, the catalytic system is more active in IL than in toluene (entry 1 vs. 2, Table 5). Contrarily, with amine L8, the catalytic system is more active in toluene than in IL (entry 4 vs. 3, Table 5). So it seems that the reduction of palladium(0) is more difficult in the ionic liquid than in toluene for palladium(II) complexes containing robust N,N-bidentated ligand, avoiding the formation of the active species. Therefore depending on the solvent (toluene vs. ionic liquid) well-adapted ligands should be chosen.

Suzuki C–C reaction in toluene and [BMI][PF6].

| Entry | L | Time (h) | Temp. (°C) | Yield in [BMI][PF6] (%) | Yield in toluene (%) |

| 1 | L7 | 1 | 60 | 93 | – |

| 2 | L7 | 6 | 100 | – | 36 |

| 3 | L8 | 6 | 100 | 4 | – |

| 4 | L8 | 6 | 100 | – | 57 |

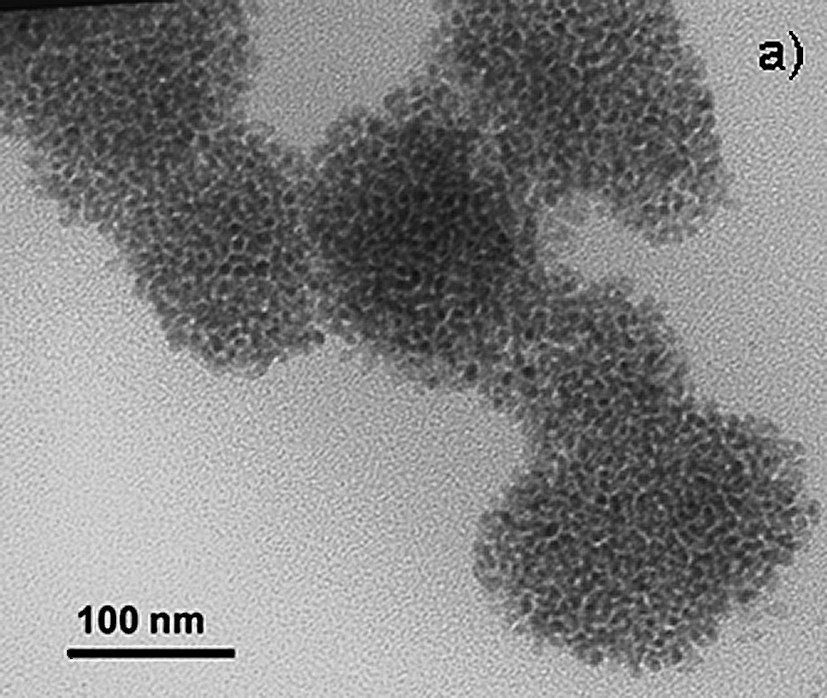

In order to elucidate the nature of the active catalyst, different analyses were made. The palladium content in biphenyl was determined by ICP–MS for the isolated product indicating that a notary metal leaching from the ionic liquid phase to the organic phase is more important at low substrate conversions (63 ppm), than for quantitative yields (10 ppm). As observed for Heck reactions with preformed nanoparticles [32], it seems that in our conditions, palladium nanoparticles act as a reservoir of catalytically active molecular species. TEM micrograph of the post-catalysis ionic liquid phase (Fig. 9) was carried out. In fact, small nanoparticles were observed (ca. mean diameter 8 nm) showing a pile organization in the ionic liquid.

TEM micrograph of the post-catalysis ionic liquid phase.

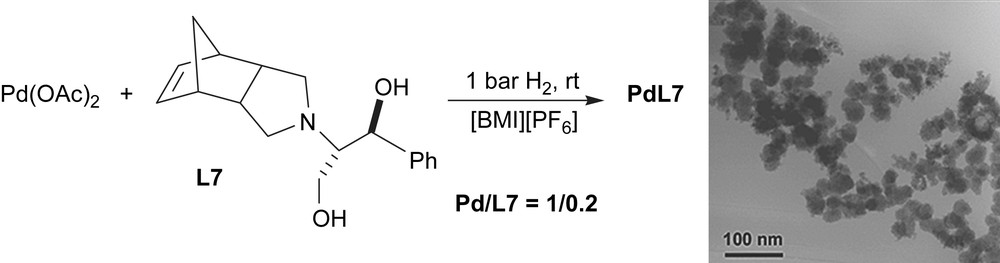

In order to compare the catalytic behaviour of particles generated under catalytic conditions with that observed using preformed material, palladium nanoparticles were prepared following the methodology previously described [1,7]. Pd nanoparticles were synthesised from palladium acetate in presence of amine L7 under hydrogen atmosphere in [BMI][PF6] (Scheme 7). TEM images essentially revealed the formation of agglomerates.

Synthesis of palladium nanoparticles containing ligand L7 (PdL7).

PdL7 nanoparticles were used as a catalytic precursor in [BMI][PF6], giving a low yield (52%) in agreement with the agglomerated material used.

The formation of catalytically active Pd(0) species depends on the solvent type and the ligand nature. When a good donor ligand is used, like bidentate nitrogen donor ligand, Pd(II) species could be reduced in Pd(0) active species in organic solvent, but not in IL. When the ligand possesses hydroxy groups, the nanoparticles in situ formed agglomerate in organic solvent, and are stable in IL.

Therefore, the mechanism proposed for Pd-catalyzed Heck C–C couplings where palladium nanoparticles act as a reservoir of active molecular species [36], seems to be also reasonable for Suzuki couplings, although the catalytic activity of the nanoparticles cannot be excluded at this time. The molecular precursor could also influence the stability and the activity of the catalytic system.

3.2 DOSY technique: a tool to shed light on metallic surface/solvent/ligand interactions

Diffusion ordered spectroscopy (DOSY) [37–40] obtained through pulsed field gradient (PFG) NMR experiments [41,42] has become a multi-purpose tool in the chemical laboratory due to its ability to gain insight into the inner behaviour of solution systems through the measurement of diffusion coefficients (D) and their correlation with properties such as molecule size, weight, shape, etc. or the relation with the interaction between different molecules [43–46]. In order to study the interaction between the metallic surface, ligand and solvent for palladium nanoparticles dispersed in ionic liquids, multinuclear (1H, 31P, 19F and 11B) DOSY technique has been applied [9]. Even if the nanoparticles themselves cannot be detected through NMR, observation of the solvent (methanol) and the ionic liquid ([BMI][PF6] or [BMI][NTf2]), their diffusion coefficients and their changes in the presence of nanoparticles allow us to draw significant assumptions about the organization of palladium nanoparticles in the ionic liquid.

A very elegant approach to ensure diffusion data accuracy and reproducibility is the use of relative diffusivity [47,48,49], also applied when metal oxide nanoparticles are involved [50,51,52]. In this approach, an internal diffusion reference molecule is introduced, and the diffusion coefficients are given as a ratio Dcompound/Dreference (or vice versa).

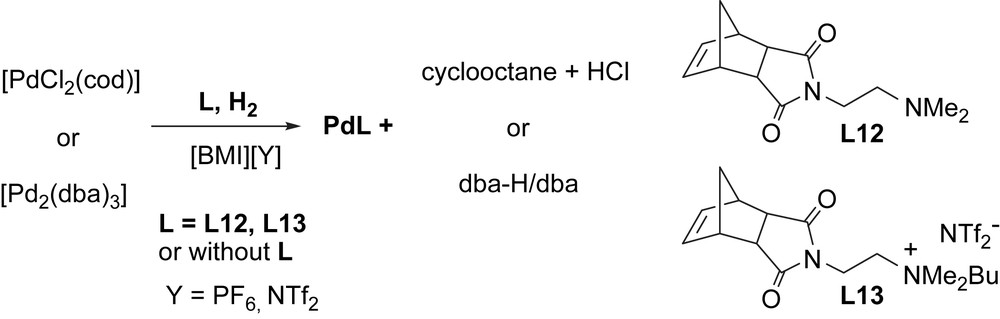

As stated above, we have already demonstrated that both ligand-free systems [7], and those containing additional ligands (possessing donor groups or ionic ammonium moieties) [8], can be of interest in catalytic carbon–carbon-coupling reactions. Wanting to gain more information concerning the nature of the interactions involved and the organization in such systems, we have described for the first time, the use of the DOSY technique to palladium nanoparticles stabilized only by IL or also by added ligand (Scheme 8).

Synthesis of palladium nanoparticles (Pdcod, Pddba, PdcodL12, PdcodL13, PddbaL12 and PddbaL13) in ionic liquid ([BMI][PF6] or ([BMI][NTf2]).

The relation between the relative diffusion coefficient of the anion and the cation forming the ionic liquid (Danion/Dcation) was also calculated in order to study the degree of ion pairing in the ionic liquid for each sample. TEM (Transmission Electronic Microscopy) analysis carried out after the spectroscopic experiments evidenced that no modification (in size and shape) of the nanoparticles is produced in presence of methanol.

[BMI][PF6] and [BMI][NTf2] in absence of any metallic species or ligand are tested and present some significant differences. Only in the presence of [BMI][PF6], a strong interaction and ordering of the methanol are found. These data agree with the loss of polymeric structure [53,54] of the ionic liquid in the presence of protic co-solvents, specially important for [BMI][PF6], but much less significant for [BMI][NTf2] [55]. The different behaviour of [BMI][NTf2] in relation to [BMI][PF6], could probably be due to the lower symmetry of the bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide anion, NTf2, in comparison to PF6. With the aim of simplifying the following discussion, only [BMI][PF6] will be taken into account.

For palladium nanoparticles without added ligand, Pdcod and Pddba, we have observed that methanol does not interact significantly with the metallic surface; this fact suggests a direct interaction of the ionic liquid with the metallic surface (entries 3, 4 and 5, Table 6). Moreover, we could postulate that the cation (BMI) interacts directly with the surface of the nanoparticles, due to the significant diminution of DBMI comparing with that observed for Danion (entries 3, 4 and 5, Table 6).

Relative diffusion coefficients (related to TMS) for nanoparticles systems in [BMI][PF6].

| Entry | Sample | Dmet | DBMI | DPF6 | Danion/Dcation |

| 1 | Neat MeOD | 1.69 | – | – | – |

| 2 | Neat [BMI][PF6] | – | 1.88 × 10−2 | 1.75 × 10−2 | 0.93 |

| 3 | [BMI][PF6] | 1.17 | 0.54 | 0.66 | 1.22 |

| 4 | Pdcod | 1.11 | 0.48 | 0.62 | 1.29 |

| 5 | Pddba | 1.23 | 0.48 | 0.61 | 1.27 |

| 6 | PdcodL12 | 1.35 | 0.42 | 0.56 | 1.33 |

| 7 | PdcodL13 | 1.06 | 0.52 | 0.63 | 1.21 |

| 8 | PddbaL12 | 1.26 | 0.47 | 0.55 | 1.17 |

| 9 | PddbaL13 | 1.23 | 0.48 | 0.59 | 1.23 |

For the systems prepared in the presence of ligands, PdcodL and PddbaL (L = L12 and L13), we observe different behaviours depending on the ligand nature. For PdcodL12 and PdcodL13 in [BMI][PF6], a divergence in comparison with the system without ligand is clearly evidenced. Therefore, BMI interacts weakly with the surface (Danion/Dcation ratio for PdcodL13 is the same as that observed for [BMI][PF6] in methanol (entries 3 and 7, Table 6)), probably due to the competition between both cationic species, BMI and the ammonium derivative coming from L13 (entries 3, 6 and 7, Table 6). BMI interacts also with L12 by hydrogen bond formation (due to the presence of dimethylamino group, see Scheme 8). As a result a big nanoparticle/L12/BMI structure can probably be the responsible of the mobility diminution of the corresponding anion. For nanoparticles derived from the molecular complex [Pd2(dba)3], Pddba, PddbaL12 and PddbaL13 in [BMI][PF6], a weak interaction of the ionic liquid with the surface is observed probably due to the presence of the remaining dibenzylidenacetone (dba), leading to a nanoparticle/dba/L12/BMI structure (entries 5, 8 and 9, Table 6).

In order to prove the different interaction of the ionic liquid with molecular species in relation to that observed for metallic nanoparticles, diffusion measurements have been carried out for ligands L12 and L13 and both molecular palladium complexes, [PdCl2(cod)] and [Pd2(dba)3]. We have observed the solvation ability of methanol for molecular species, independently of the IL employed.

As a result, these experiments permit us to prove the presence of Lewis bases coordinated at the metallic surface by a significant decrease of IL diffusion coefficients relative to ligand-free nanoparticles. This effect is better revealed by ionic liquids showing a strong trend to form ion pairs in the presence of a co-solvent (in our case, methanol), as observed for [BMI][NTf2]. This behaviour is not observed for molecular species (ligands and metallic complexes) independently of the ionic liquid nature. Even if we are very far away from a comprehension of these really complicated systems and their properties, DOSY allows us to probe the systems, detecting meaningful changes in the dynamics of their components.

4 Final remarks

The use of metallic nanocatalysts in liquid phase is mechanistically intricate. First, this approach requires the analysis about the catalytic active species because of their kinetic stability; in solution, these materials can be agglomerated but also can give the leaching of molecular species due to the high reactivity of the low coordination atoms at the metallic surface. Second, knowledge about the interactions of organic molecules with the surface turns into being essential to justify the catalytic behaviour induced. For that, tools like spectroscopy techniques are appropriate means to elucidate how the substrates or solvents interact with the nanocluster, as described here using NMR in organic and in ionic liquid solvents. Further work in this research area seems to be promising in order to progress in the applications of nanocatalysts.

Acknowledgements

We thank CNRS and Université Paul-Sabatier for financial support.