1 Introduction

The synthesis and perfect assembly of 2- and 3-D structures from molecular components (nanobuilding blocks) is of immense current interest due to the potential to realize novel properties in nanosized and nanostructured materials, since materials reduced to the nanoscale often exhibit very different properties or phenomena compared to the macroscale. In fact, the essential challenge is to control matter at these dimensions because the ability to tailor global properties precisely is dependent on manipulating component organization at the finest length scales. Indeed the construction of materials nanometer-by-nanometer should lead to the design of a variety of materials with well-defined nanoarchitectures and predictable behaviors.

Consequently highly symmetrical nanobuilding blocks are required, particularly those that offer both diverse functionality coupled with ease of synthesis, since it follows that breaks in periodicity (defects) in assembled 2- and 3-D structures should be minimized with higher component symmetry. Since the energy required to create a defect is offset by a gain in entropy, in theory defects can be minimized by using highly symmetrical and well-ordered components that minimize the entropy of a given system. It can be expected then that misaligned but highly symmetrical components would require the least energy (associated with the least movement) to reorient and align with other assembled components. Accordingly, cubic structures (offering the highest symmetry) would also require the least energy to assemble [1]. Note that defects will still occur due to temperature-dependent entropic effects (TΔS).

Still another perhaps more important issue is the fact that assembly is often driven by kinetics rather than thermodynamics. Thus, for example in studies on the assembly of supramolecular structures, it is possible to actually find assembled structures wherein on edge of the structure is completely random and the opposite side is perfectly ordered [2]. Alternately, if the energy of two similar structures is very close, then one can observe stacking faults resulting from twinning [3]. In a similar vein, if surface orientation energies are very similar one can also drive the assembly of two different polymorphs at surfaces that promote assembly [4]. Finally, control of solvent effects assembly conditions and temperature can drastically change the types of assembly observed [5]. Thus, although high symmetry is the best place to start, it is important to recognize that this alone can only be considered an optimal starting point but not a guarantee of perfectly controlled assembly.

Cubic silsesquioxanes are one of the few groups of 3-D molecules with structures that offer high symmetry, ease of synthesis and/or modification, and octafunctionality such that each octant in Cartesian space contains one functional group. It is the positioning of functional groups, the variety possible, and their nm size that provide unique opportunities to build nanocomposites in 1-, 2- or 3-D, one nm at a time [6–37]. In addition, the core adds the rigidity and heat capacity of silica (in essence “the smallest single crystal sand particle”) making these compounds thermally robust at elevated temperatures.

As nanoconstruction sites, completely condensed silsesquioxanes can be further functionalized by direct chemical modification of the organic moieties to form larger, well-defined structures. However, similar “bottom-up” construction possibilities may also exist by employing incompletely condensed silsesquioxanes as nanobuilding blocks. Recently, incompletely condensed silsesquioxanes ((RSiO1.5)a(H2O)0.5b, where a, b, n are integers: a + b = 2n, b < a + 2) have attracted attention as models for silica-supported systems, ligands for homogeneous catalysts, and comonomers in silsesquioxane-siloxane polymers [38]. Of particular interest to us is the all cis-(RSiO1.5)4(H2O)2 “half cube” (Fig. 1a), since it represents a proposed intermediate in the formation of completely condensed cubic silsesquioxanes [39,40].

Suggested structures of a: [RSiO(OH)]4 “half cube”; b: [PhSiO(ONa)]4 half cube salt; c: [p-IPhSiO(ONa)]4 half cube salt.

In principle, such incompletely condensed half cube silsesquioxanes may provide potential access to “perfectly” defined surfaces via “Janus” (two-faced) cubes and may also help explain the unique emission characteristics of stilbene silsesquioxane derivatives, which are red-shifted up to 80 nm (0.75 eV) [41]. The synthesis of a Janus cube such as suggested by Fig. 2 could help support (or refute) the existence of 3-D excited state conjugation through the center of the silsesquioxane cage, which DFT HOMO-LUMO calculations have deemed quite possible. [42].

Proposed structure of tetrastilbene cubic silsesquioxane [StilbeneSiO1.5]4[RSiO1.5].

In addition, bi-functional Janus cubes in principle can be tailored to modify surfaces and/or thin films with nanometer-length control of individual layers. In addition, one could also introduce bifunctionality allowing layer-by-layer coatings of hydrophobic/hydrophilic or hard/flexible layers with defined length scales. Janus cubes could also serve as interfaces between different domains or to guide self-assembly wherever complementary or dissimilar chemical functionalities are used. Here we describe efforts to develop routes to Janus cubes through studies on the functionalization of compounds like that shown in Fig. 1b.

2 Experimental section

2.1 Materials

All trichlorosilanes were purchased from Gelest, Inc. and used without further purification. All other chemicals were purchased from Fisher or Aldrich and used as received. Octaphenyl-silsesquioxane (OPS) and octaiodophenylsilsesquioxane (I8OPS) were synthesized following methods described in the literature [42,43]. All work was performed under N2 unless otherwise stated.

2.2 Analytical methods

2.2.1 Gel permeation chromatography

All GPC analyses were done on a Waters 440 system equipped with Waters Styragel columns (7.8 × 300, HT 0.5, 2, 3, 4) with RI detection using Optilab DSP interferometric refractometer and THF as solvent. The system was calibrated using polystyrene standards and toluene as reference.

2.2.2 NMR analyses

All 1H and 13C-NMR analyses were done in CDCl3 (or CD3OD) and recorded on a Varian INOVA 400 spectrometer. 1H-NMR spectra were collected at 400.0 MHz using a 6000 Hz spectral width, a relaxation delay of 3.5 s, a pulse width of 38°, 30 k data points, and CHCl3 (7.27 ppm) as an internal reference. 13C-NMR spectra were collected at 100 MHz using a 25000 Hz spectra width, a relaxation delay of 1.5 s, 75 k data points, a pulse width of 40°, and CDCl3 (77.23 ppm) as the internal reference.

2.2.3 Thermal gravimetric analysis (TGA)

Thermal stabilities of materials under N2 or air were examined using a 2960 simultaneous DTA-TGA Instrument (TA Instruments, Inc., New Castle, DE). Samples (5–10 mg) were loaded in platinum pans and ramped to 1000 °C (10 °C/min/N2). The N2 or airflow rate was 60 mL/min.

2.2.4 FTIR spectra

Diffuse reflectance Fourier transform (DRIFT) spectra were recorded on a Mattson Galaxy Series FTIR 3000 spectrometer (Mattson Instruments, Inc., Madison, WI). Optical grade, random cuttings of KBr (International Crystal Laboratories, Garfield, NJ) were ground, with 1.0 wt% of the sample to be analyzed. For DRIFT analysis, samples were packed firmly and leveled off at the upper edge to provide a smooth surface. The FTIR sample chamber was flushed continuously with N2 prior to data acquisition in the range 4000–400 cm-1.

2.2.5 Melting point

Melting point determinations were performed on samples using a Mel-Temp 3.0 (Laboratory Devices, Inc. Dubuque, IA) with a ramp rate of 5 °C/min.

2.2.6 Matrix-assisted laser-desorption/Time-of-flight spectrometry

MALDI-TOF was performed on a Micromass TofSpec-2E equipped with a 337 nm nitrogen laser in positive ion reflection mode using poly(ethylene glycol) as the calibration standard, 1,8,9-anthracenetriol as the matrix, and AgNO3 as the ion source. Samples were prepared by mixing solutions of five parts dithranol (10 mg/mL in THF), five parts sample (1 mg/mL in THF) and one part AgNO3(10 mg/mL in water) and blotting the mixture on the target plate.

2.3 Synthetic methods

2.3.1 Synthesis of tetraphenyl sodium salt from OPS

To a dry 250 mL round bottom flask under N2 and equipped with a magnetic stir bar and reflux condenser was added 5.00 g OPS (4.84 mmol, 38.8 mmol Si), 1.71 g NaOH (42.6 mmol), and 150 mL n-BuOH. The solution was stirred at 110 °C for 24–48 h, during which time it turns yellowish green. The hot solution was gravity filtered to remove the insolubles and allowed to cool to room temperature. The solution was then placed in a freezer and after 24 h white needle-like crystals form. The solid was filtered and dried in vacuo at 50 °C for 6 h, giving 4.97 g [(80%) – Fig. 1b]. Characterization data: 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO): 7.1 (1H, m, para Ar-H), 7.2 (2H, m, meta Ar-H), 7.7 (2H, m, ortho Ar-H).

2.3.2 Reaction of tetraphenyl sodium salt and Me3SiCl3

To a 250 mL round bottom flask under N2 and equipped with magnetic stir bar was added 8.23 mL Me3SiCl (65.0 mmol) and 2.83 mL pyridine (35.0 mmol) in 50 mL of toluene. 5.00 g of tetraphenyl sodium salt (8.22 mol) was added in one portion and the resulting mixture was refluxed for 1.5 h. The mixture was allowed to cool to room temperature and the insolubles were gravity filtered. The toluene filtrate was washed with water and dried over sodium sulfate. Benzene was removed in vacuo at 50 °C for 12 h to give 6.23 g (90.0%) of white crystalline solid. Characterization data: 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): 0.2 (36H, s, CH3), 7.1 (4H, m, Ar-H), 7.3 (4H, m, Ar-H), 7.4 (8H, m, Ar-H) ppm.

2.3.3 Synthesis of tetra(p-iodo)phenyl sodium salt from I8OPS

To a dry 250 mL round bottom flask under N2 and equipped with a magnetic stir bar and reflux condenser was added 3.40 g I8OPS (1.66 mmol, 13.28 mmol Si), 0.53 g NaOH (13.25 mmol), and 100 mL n-BuOH. The solution was stirred at 110 °C for 12 h, during which time it turns colorless after 40 mins. The hot solution was gravity filtered to remove the insolubles and allowed to cool to room temperature. The solvent was removed slowly under reduced pressure at 35 °C for ∼5 h at which point white needle-like crystals form. The solid was filtered and dried in vacuo at 50 °C for 6 h, giving 2.82 g [(74%) – Fig. 1c]. Characterization data: 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD): 7.3 (2H, m, meta Ar-H), 7.6 (2H, m, ortho Ar-H).

2.3.4 Synthesis of tetramethyltetraphenyl dimethoxy derivative

To a 500 mL round bottom flask under N2 and equipped with magnetic stir bar was added a suspension of 5.00 g of tetraphenyl sodium salt (8.22 mmol) in 100 mL MeOH. 4.25 mL of CH3SiCl3 (36.2 mmol) was dissolved in 100 mL of hexane and added to the MeOH suspension via addition funnel over 30 minutes. The heterogeneous reaction mixture was allowed to stir for 24 h at room temperature at which point insoluble NaCl formed. The salt was filtered from the reaction mixture and the hexane layer was separated, dried over Na2SO4, and rotary evaporated to give viscous light-yellow oil. The oil was dried in vacuo at 80 °C for 6 h to give 6.20 g (82%). Characterization data: 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCD3): 0.4 (3H, s, CH3), 3.2 (6H, s, OCH3), 7.2 (3H, m, Ar-H); 7.6 (2H, m, Ar-H) ppm; GPC: Mn 658; Mw 684; PDI 1.09.

2.3.5 Hydrolysis of tetramethyltetraphenyl dimethoxy derivative

To a 25 mL round bottom flask under N2 and equipped with magnetic stir bar was added 0.500 g (0.516 mmol) of tetramethyltetraphenyl dimethoxy derivative dissolved in 10 mL of hexane. 5 mL of H2O and 1 mL of concentrated HCl were added dropwise to the solution and allowed to react 24 h at room temperature. The white insoluble precipitate (0.344 g, 85%) was filtered and dried in vacuo at 80 °C for 12 h. Characterization data: TGA (air, 1000 °C): Found 61.2%; Calculated 61.2%; Td5% 450 °C; IR: vC = H (3048–2939), vCH3 (2838), vC = C (Ar ring, 1591), vSi-CH3 (1269), vSi-O(1132) cm-1.

2.3.6 Bromination of tetramethyltetraphenyl Janus cube

To a 50 ml Schlenk flask under N2 and equipped with a magnetic stir bar was added granular iron (0.060 g, 1.00 mmol), tetramethyl tetraphenyl silsesquioxane (2.00 g, 2.56 mmol), and CH2Cl2 (15 mL). The suspension was cooled to 0 °C and bromine (3.30 g, 21.0 mmol) was slowly added. The suspension was stirred for two days and then more bromine (0.1 mL) and iron (0.02 g) were added and stirred for an additional two days. The suspension was filtered and the organic layer was washed with a sodium bicarbonate solution and then dried over Na2SO4. Solvent was removed under reduced pressure and the solid was collected, washed with water (3 × 10 mL), acetone (3 × 10 mL) and diethylether (3 × 10 mL) and dried in vacuo to give 1.2 g as white solid (64%). Characterization data: IR: vC = H (2870), vSi-C (1274), vSi-O (1142, 1041), cm-1; MALDI-TOF: m/z (Ag+ adduct) = 897 [Si8O12(C6H5)3(CH3)4], 970 [Si8O12(C6H4Br)(C6H5)3 (CH3)4], 1205 [Si8O12(C6H4Br)4(CH3)4].

2.3.7 Synthesis of tetraphenyltetravinyl dimethoxy derivative

To a 500 mL round bottom flask under N2 and equipped with magnetic stir bar was added a suspension of 5.00 g of tetraphenyl sodium salt (8.22 mmol) in 100 mL MeOH. About 4.60 mL of C2H3SiCl3 (36.2 mmol) was dissolved in 100 mL of hexane and added to the MeOH suspension via addition funnel over 30 min. The heterogeneous reaction mixture was allowed to stir for 24 h at room temperature at which point insoluble NaCl formed. The salt was filtered from the reaction mixture and the MeOH layer was separated, dried over Na2SO4, and rotary evaporated to give a viscous colorless oil. The oil was dried in vacuo at 80 °C for 6 h to give a white crystalline solid 6.91 g (87%). Characterization data: 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD): 3.2 (6H, s, OCH3), 5.9 (3H, m, -CH = CH2), 7.2 (3H, m, Ar-H), 7.6 (2H, m, Ar-H) ppm; GPC: Mn 705; Mw 741; PDI 1.05.

2.3.8 Hydrolysis of tetraphenyltetravinyl dimethoxy derivative

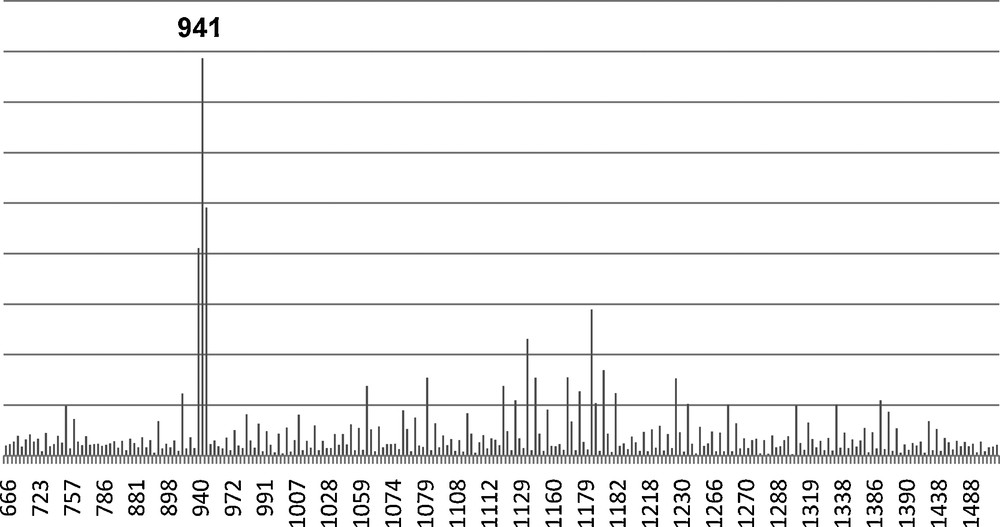

To a 25 mL round bottom flask under N2 and equipped with magnetic stir bar was added 0.500 g (0.492 mmol) of tetraphenyltetravinyl dimethoxy derivative dissolved in 10 mL of MeOH. Five millitres of H2O and 1 mL of concentrated HCl were added dropwise to the solution and allowed to react 24 h at room temperature. The white insoluble precipitate (0.377 g, 92%) was filtered and dried in vacuo at 80 °C for 12 h. Characterization data: TGA (air, 1000 °C): Found 51.5%; Calculated 57.7%; Td5% 424 °C; IR: vC = H (3048–2950), vC = C (1630), vC = C (Ar ring, 1593), vSi-O (1134), cm-1; MALDI-TOF: m/z (Ag+ adduct) = 755, 900, 941, 1060, 1080, 1130, 1180, 1230 [AgSi8O12(C6H5)4 (C2H3)4) 941].

2.3.9 Synthesis of tetracyclohexyltetraphenyl dimethoxy derivative

To a 500 mL round bottom flask under N2 and equipped with magnetic stir bar was added a suspension of 5.00 g of tetraphenyl sodium salt (8.22 mmol) in 100 mL MeOH. 6.45 mL of C6H9SiCl3 (36.2 mmol) was dissolved in 100 mL of hexane and added to the MeOH suspension via addition funnel over 30 min. The heterogeneous reaction mixture was allowed to stir for 24 h at room temperature at which point insoluble NaCl formed. The salt was filtered from the reaction mixture and the hexane layer was separated, dried over Na2SO4, and rotary evaporated to give a viscous light-yellow oil. The oil was dried in vacuo at 80 °C for 6 h to give 7.76 g (76%). Characterization data: 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): 0.8 (3H, m, aliphatic-H), 1.2 (4H, m, aliphatic-H), 1.7 (4H, m, aliphatic-H), 3.5 (7H, m, OCH3), 7.4 (2H, m, Ar-H), 7.7 (3H, m, Ar-H) ppm; GPC: Mn 934; Mw 1037; PDI 1.18.

3 Results and discussion

The objectives of the current study are to develop straightforward routes to half cube silsesquioxanes that in turn may be tailored by simple chemistry. The resulting modified half cubes could then be hydrolyzed to form fully condensed Janus cubes with different moieties on each defined “face” of the cube. For example, any effort to functionalize just four of the eight p-iodo groups in I8OPS, [43] see reaction (3) below, would lead not only to a statistical distribution of functional groups at the corners rather than functionalizing only one side, it would also lead to sets of products where the average degree of substitution would be four.

Thus, one can only expect to form a true Janus cube (where each face has one specific functionality) exclusively via a half cube intermediate. Previous work [39,43–48] by others and members of our team [44] focused on using acid-catalyzed hydrolysis of aromatic trichloro- or triethoxysilanes to form half cubes as suggested in reaction (1).

However, the susceptibility of incompletely condensed half cubes (Fig. 1a or the product of reaction (1)) to further condensation even at room temperature in the solid state severely limits their utility and makes subsequent modification of the phenyl groups (i.e. by electrophilic aromatic substitution) essentially impossible without encountering extensive undesirable side reactions. In the past, the incorporation of tailorable moieties on the half cube required prior functionalization of the starting monosilane via multiple step reactions involving both air and moisture sensitive intermediates [44]. We report here an alternative route that permits access to desired perfectly functionalized half cube intermediates and initial efforts to produce Janus cages.

4 Synthesis of tetra(p-iodo)phenyl tetrasilesquioxane (I4Ph4) sodium salt

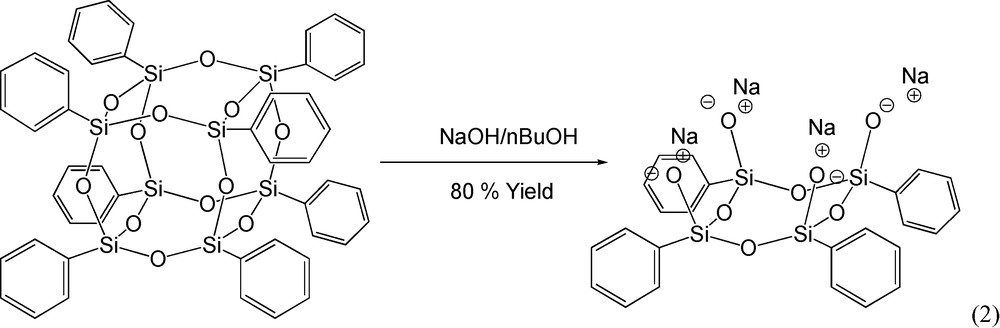

Shchegolikhina et al. [46] reported the high yield synthesis of the sodium salt of tetraphenyl tetrasilesquioxane [(Ph4 half cube) – Fig. 1b] from OPS, reaction (2). The structure of the Ph4 half cube salt was corroborated by 1H NMR and reacts as expected (see below) based on the literature [46].

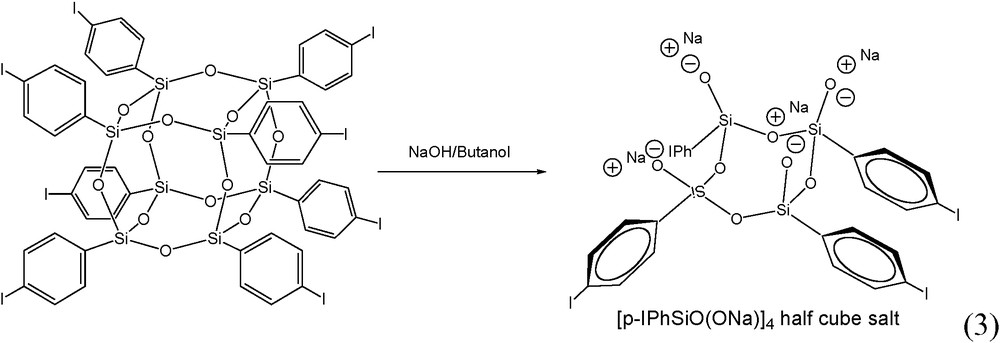

A similar approach was extended to the NaOH cleavage of I8OPS to produce [p-IPhSiO(ONa)]4, Fig. 1c and reaction (3), which incorporates a modifiable para iodo on the aromatic ring. This compound is readily synthesized in one step in high yield (see experimental section) and eliminates the need for Grignard modification of a triethoxysilane. The structure of the I4Ph4 sodium salt was confirmed by 1H NMR and the absence of a para aromatic proton (due to p-iodo substitution) is observed in the spectrum. A single crystal XRD data set was collected and while the data at this time are not suitable for publication, the structure clearly shows the I-Ph-groups entirely cis on one face and the half cube in a distorted boat conformation [45,47].

As shown by Feher et al., [39] Shchegolikhina et al. [46] and Pizzotti et al. [44], these salts react quantitatively with in the presence of an amine base. In principle, reaction of the nucleophilic oxygen with produces a trimethylsilyl “face” that protects the half cube from further hydrolysis. This would allow subsequent modification of the iodophenyl group by various Pd-catalyzed coupling reactions [43] (Heck, Sonogashira, Suzuki, etc.) and exclude unwanted side reactions. In principle the trimethylsilyl protecting group could then be removed by displacement with either fluoride or oxygen nucleophiles to regenerate the hydroxyl group. This remains an area for future investigation.

5 Synthesis of tetramethyltetraphenyl (Me4Ph4) silsesquioxane

In an effort to make fully condensed Janus cubes, the Ph4 half cube sodium salt was reacted with MeSiCl3 in the presence of methanol at room temperature to form the tetramethyltetra-phenyl (Me4Ph4) dimethoxy half cube derivative [PhSi(O)O(Me)Si(OCH3)2]4 reaction (4). 1H NMR spectroscopy confirmed the structure of the product and revealed that the remaining chloro groups are replaced by methoxy groups due to reaction with methanol solvent. GPC analysis reveals a single peak with a molecular weight lower than expected (Mn = 658 and Mw = 684 vs. 969 amu theory), but such discrepancies are typical of silsesquioxane compounds due to their smaller hydrodynamic radii compared to polystyrene standards. Mass determination by MALDI-ToF was unsuccessful and such compounds may not be readily ionizable.

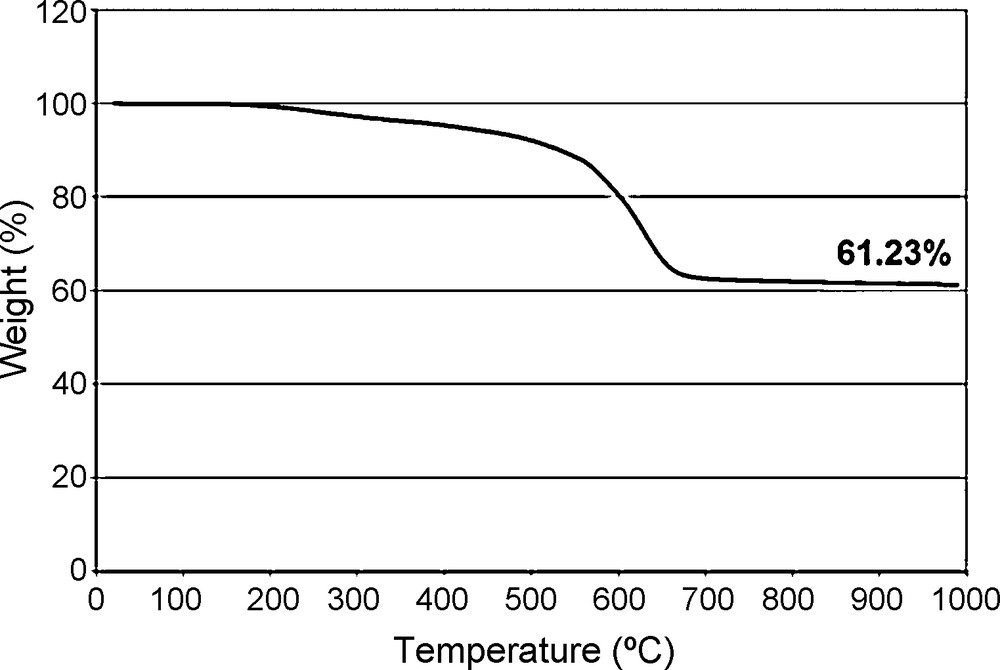

Hydrolysis of Me4Ph4 dimethoxy half cube derivative and subsequent cage closure was achieved by reaction with H2O and conc. HCl (at dilute concentrations) to form the Me4Ph4 Janus cube (Fig. 3) in 85% yield. Supporting TGA data is shown in Fig. 4. The ceramic yield (61.23%) is essentially identical to theory (61.21%), which is a strong indication that the product formed is indeed Me4Ph4 silsesquioxane. Unfortunately, the yields of this material are rather low, 10%.

[PhSiO1.5]4[MeSiO1.5] Janus silsesquioxane cube.

TGA (air) of [PhSiO1.5]4[MeSiO1.5].

The correlation of the ceramic yield of the fully condensed product to theory seems to indicate that all of the -O(Me)Si(OCH3)2 groups of the starting material are cis on the same face of the half cube, or else subsequent reaction with aqueous acid would lead to the formation of high MW oligomeric condensation products. Thus the TGA ceramic yield seems to support that the phenyl and methyl groups are located on opposite sides of the cube.

In addition to the TGA, the melting point of the Me4Ph4 cube (112–114 °C) formed in Fig. 3 is essentially the same (116–118 °C) as reported by Andrianov et al. [47] formed by the reaction of cis-1, 3, 5, 7-tetrahydroxy-1, 3, 5, 7-tetraphencylcyclotetrasiloxane with tetramethylcylclotetrasiloxane in low concentrations.

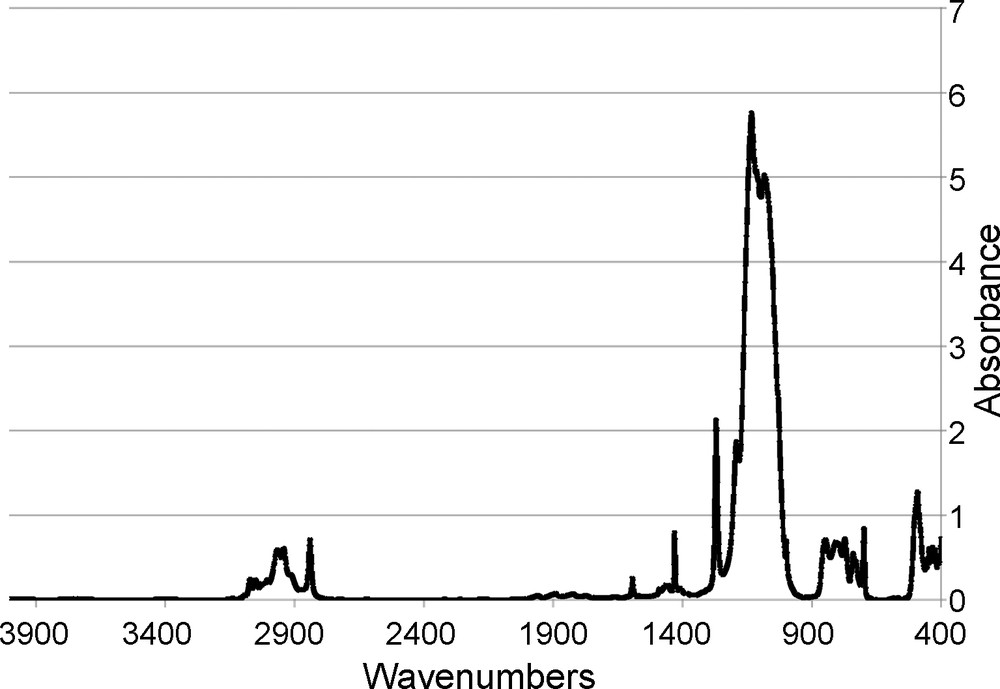

The FTIR of the Me4Ph4 cube, Fig. 5, exhibits characteristic aromatic v = C-H stretching vibrations (ca. 3070–2970 cm-1), aliphatic vC-H stretching vibrations (ca. 2490 cm-1), vSi-C bond vibrations (1270 cm-1), and vSi-O bonds attributed to the silsesquioxane cage (1130 cm-1). Perhaps most importantly, no vO-H bond vibrations (ca. 3200–3400 cm-1) are seen signifying a lack of unreacted -OH groups and a completely condensed compound.

FTIR of [PhSiO1.5]4[MeSiO1.5].

We have not been able to gather evidence for the structure of the Me4Ph4 cube by NMR or MALDI-TOF because it is highly insoluble in both nonpolar and polar organic solvents (CHCl3, DMSO, THF, MeOH, etc.). MALDI spectrometry data was inconclusive because effective sample preparation requires THF solubility to allow intimate mixing with aqueous AgNO3 solution.

Unfortunately, recent efforts to reproduce the synthesis of the hydrolysis product have been inconsistent (even under the exact same experimental conditions) and have sometimes led to insoluble products with lower-than-expected ceramic yields (∼ 45–55% – indicating higher-than-expected Mws) and no melting points. This seems to indicate that oligomerization of the dimethoxy derivative occurs and hydrolysis at the methoxy-substituted silicon proceeds competitively via bi-molecular (or higher-molecular) pathways even at highly dilute concentrations of acid and/or water. The inconsistency in forming the intended product signifies a more complicated hydrolysis mechanism than originally predicted. Recently we tried a variety of hydrolysis conditions and varied solvents, concentrations of reactants, reaction time, temperature, etc. with no clear insight into hydrolysis optimization. Amore precise and rigorous study into the optimization of the hydrolysis conditions to form the Me4Ph4 Janus cube exclusively via a unimolecular pathway is necessary.

As a result of these shortcomings, we attempted to brominate the phenyl moieties of the Me4Ph4 cube, reaction (5) in order to make the compound more soluble (and thus more easily isolable). We found evidence for the Ag+ adduct of both mono- [Me4(Br-Ph)1Ph3] and tetra-brominated [Me4(Br-Ph)4] Janus cube. However, the very limited solubility of Me4Ph4 in solution gave moderate yields (64%) of a mixture of soluble products, of which we are uncertain as to the amounts of mono- and tetra-brominated Janus cube and/or higher-MW brominated species. Furthermore, bromination of phenyl silsesquioxanes always gives rise to a mixture of isomers and varying degrees of substitution [48]. No further attempt was made to isolate solely the tetra-brominated Janus cube and represents an area for further investigation.

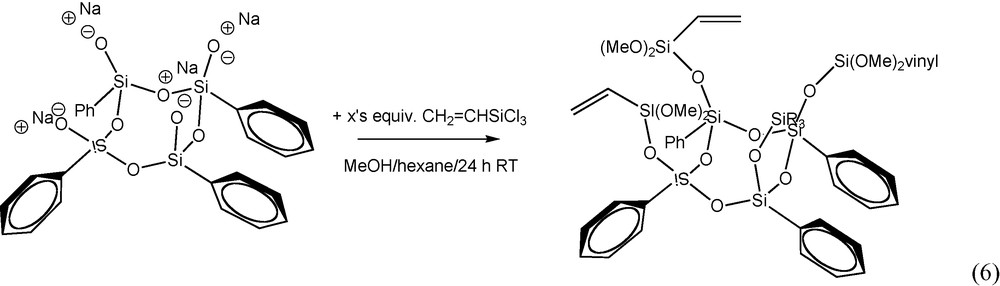

6 Synthesis of [PhSiO1.5]4[vinylSiO1.5]

Similarly the tetraphenyltetravinyl dimethoxy derivative [PhSi(O)OSi(Vinyl)(OCH3)2]4 was formed by reaction of the Ph4 half cube sodium salt with vinyltrichlorosilane at room temperature in the presence of methanol, reaction (6). Unlike the Me4Ph4 dimethoxy derivative (which is a viscous oil), the Vinyl4Ph4 derivative is a white crystalline solid. The structure of the Vinyl4Ph4 dimethoxy derivative was confirmed by 1H NMR and is shown in Fig. 6. The spectrum exhibits characteristic aromatic (7.0–8.0 ppm), vinyl (∼5.9 ppm), and methoxy (∼3.2 ppm) peaks with the correct integration (1.9:1.0:22 actual vs. 1.7:1.0:2.0 theory, respectively). GPC analysis showed a single peak consistent with the proposed molecular weight.

1H NMR of [PhS1.5]4[vinylSiO1.5]. (CD3OD).

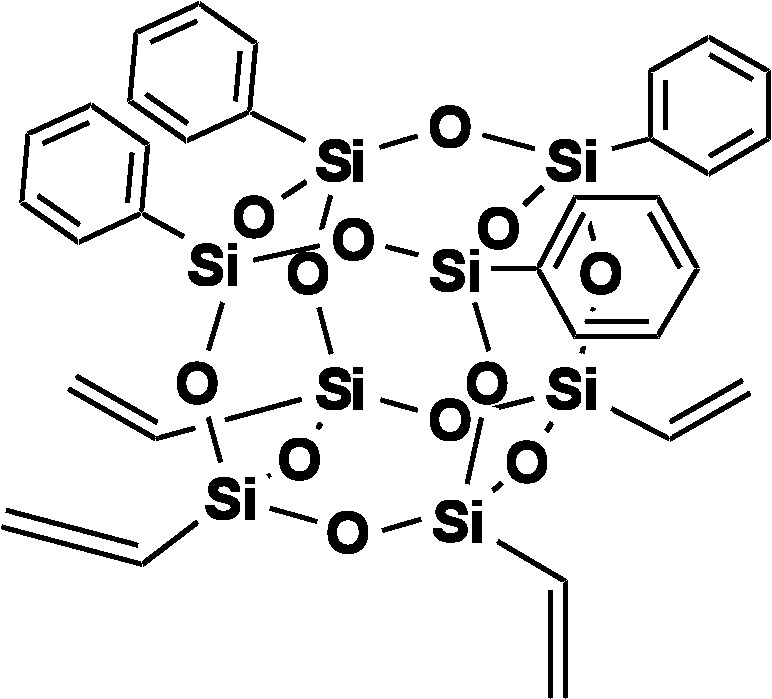

Again we attempted to hydrolyze the Vinyl4Ph4 dimethoxy derivative with H2O and HCl as previously to form the Vinyl4Ph4 Janus cube (Fig. 7). The MALDI spectrum of the hydrolysis product is shown in Fig. 8. While the spectrum indicates the presence of the MW (Ag+ adduct) of the proposed structure, higher MW peaks in the MALDI also suggests the existence of oligomeric or polymeric condensation products in addition to the desired compound. Moreover, since the resulting product is insoluble in both aqueous and organic solvents, GPC and 1H NMR analyses of the hydrolyzed product are impractical in this case.

[PhSiO1.5]4[vinylSiO1.5].

MALDI of tetravinyltetraphenyl (Vinyl4Ph4) Janus cube (m/z Ag+). 941 Da is the expected Mw of the proposed product.

As in the case of Me4Ph4 derivative, the hydrolysis of the Vinyl4Ph4 dimethoxy derivative may proceed via bimolecular pathways because of the competing reactivity of the methoxy-substituted silicon. Again, further optimization of hydrolysis conditions is needed. However, the Vinyl4Ph4 Janus cube is definitely a product that forms during hydrolysis, albeit one of many products that may or may not be easily isolated.

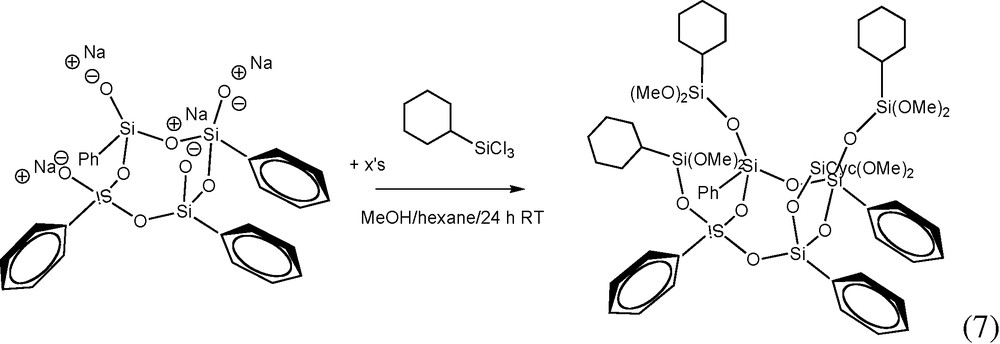

7 Synthesis of [PhSi(O)OSi(Cyclohexyl)(OCH3)2]4

The Ph4 half cube sodium salt was reacted with cyclohexyltrichlorosilane in MeOH in order to make the Cyhexyl4Ph4 dimethoxy derivative reaction (7). Again, the structure of the intended product was supported by 1H NMR and GPC analyses. Unfortunately, we were unsuccessful in hydrolyzing the Cyhexyl4Ph4 dimethoxy derivative to form the intended, fully-condensed cube. We attempted a variety of hydrolysis conditions and were only able to isolate a high MW liquid product(s). We surmise that the mechanism of hydrolysis with aqueous HCl is especially inefficient in this case because of the presence of bulky alkyl groups, which when hydrolyzed most likely form oligomeric products because of the tendency of the Cyhexyl4Ph4 dimethoxy derivative and acid to phase separate at the expense of intimate mixing. Perhaps this problem can be overcome through the use of a miscible organic acid (e.g. glacial acetic acid).

8 Conclusions

Half cube sodium salts are readily synthesized in one step and greater than 70% yields from OPS and I8OPS. In particular, the I4half cube sodium salt shows potential for further modification at the iodo moiety by a host of Pd-catalyzed substitution reactions (after protection of the hydroxyl group with Me3SiCl). We have also shown evidence for the syntheses of the Me4Ph4, Vinyl4Ph4 and Cyhexyl4Ph4 dimethoxy derivatives and their respective hydrolysis products. However, further investigation into the optimization of the hydrolysis reactions to form the Janus cubes is needed because we have also observed the formation of unwanted higher MW products. Base-catalyzed hydrolysis may also be considered as an alternative to acid-catalyzed conditions. The purity of the dimethoxy derivatives as assessed by 1H NMR and GPC suggest that the critical stage of Janus cube formation occurs during hydrolysis. Regardless, while such optimization may not be trivial, the dimethoxy derivatives still remain a potential route to nanoscale Janus cubes.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NSF through grant CGE 0740108 and in part by Canon Ltd, and Mayaterials Inc.