1 Introduction

To date, the attention from the research community for developing nanocatalysis based on Earth-abundant transition metals including Mn, Fe, Co, Ni, and Cu and early transition metals Ti, V, Cr, Zr, Nb, and W is explosively growing [1]. Among them, Fe-based nanocatalysts are generally robust, inexpensive, easy to prepare, nontoxic, magnetically recoverable, and reusable and therefore have attracted considerable interest and are used in a wide range of reactions such as Miyaura–Suzuki, Heck, Sonogashira, Knoevenagel, Hiyama, alkyne–azide cycloaddition, hydrogenation, reduction, oxidation, arylation, alkylation, epoxidation of alkenes, multicomponent reactions, Fenton-like reaction, and so forth [2,3].

Poly(ionic liquid)s (PILs) [4,5], or polymerized ionic liquids, are a class of polyelectrolytes that comprise a polymeric backbone and an ionic liquid species in monomer repeating units. The architecture of PILs can be easily redesigned by both the polymer backbone and outer ion. The chemical and mechanical properties of PILs can be tuned not only by postpolymerization but also by in situ ion exchange. Today, they are used in various applications across a countless of fields, such as stimuli-responsive materials, catalysis, precursor for carbon materials, porous polymers, antimicrobial materials, separation and absorption materials, and energy harvesting/generation as well as several special interest applications [6–8]. In this regard, merging physical and chemical properties of PILs with magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs) has been efficiently exploited in catalytic reactions [9–11].

The Knoevenagel condensation is the reaction between an aldehyde or ketone and any compound having an active methylene group [12]. Because of the mild reaction conditions and its broad applicability, the Knoevenagel reaction is a widely used method for carbon–carbon bond formation in organic synthesis with numerous applications in the synthesis of fine chemicals, hetero-Diels–Alder reactions, and in the synthesis of carbocyclic as well as heterocyclic compounds of biological significance [13,14]. Recently, a wide range of studies using MNP-supported catalyst like Fe3O4–methylene diphenyl diisocyanate-guanidine [15], Fe3O4@SiO2-3N (where 3N = N1-(3-trimethoxysilylpropyl)diethylenetriamine) [16], Fe3O4–Betti base [17], Fe3O4–cysteamine hydrochloride [18], Fe3O4@SiO2@TiO2 [19], nano-NiFe2O4 [20], CoFe2O4 [21], and Fe3O4@propylamine modified with imidazolium ionic moiety [22] have been reported for Knoevenagel condensation. In continuation of these studies, this present study reports on the synthesis and characterization of a novel MNP coated with ionic organic networks (Fe3O4–PILs) and its catalytic application in the Knoevenagel condensation of aldehydes with malononitrile.

2 Experimental section

2.1 Materials and instruments

All chemicals used in this work were commercially available and used without further purification. Reactions were monitored by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) performed on 0.25 mm Merck TLC silica gel 60 F254 plates, using UV light as a visualizing agent. The synthesized Fe3O4–PIL composite was characterized through various techniques. The Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectra (νmax) were recorded using a BOMEM MB-Series 1998 FT-IR spectrometer and samples analyzed as a KBr disk and at a scanning range of 4000–400 cm−1. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analyses were carried out using Tescan Mira 3 LMU instrument coupled with energy-dispersive X-ray (EDX) spectroscopy at a potential of 15 kV with 1 nm resolution for microanalysis and mapping of the Fe3O4–PIL nanoparticles. The transmission electron microscopy (TEM) image was recorded using a Zeiss-EM10C at 80 kV. The magnetic properties were investigated using a vibrating sample magnetometer (Meghnatis Daghigh Kavir Co, Kashan, Iran) at room temperature. The thermal stability of the Fe3O4–PIL composite was assessed using a PerkinElmer Pyris diamond thermogravimetric analysis–differential thermal analysis (TGA–DTA) by heating the sample from room temperature to 600 °C at a heating rate of 10 °C min−1 under nitrogen.

2.2 Preparation of Fe3O4–PIL composite

By using the procedure analogous to that described by Zhang et al. [23], the as prepared Fe3O4 MNPs (1 g) were dispersed in DMSO (18 mL) by ultrasonic irradiation. Then, 1,3,5-tris(bromomethyl)benzene (2 mmol, 0.357 g) and 1,4-bis(imidazol-1-yl)-butane (3 mmol, 0.285 g) were added, and the resulting mixture was heated under nitrogen bubbling and reflux conditions to 80 °C for 72 h. The MNPs were collected by an external magnet, washed with ethanol (2 × 10 mL), and mixed with NaOAC (15 mL, 1 M) at room temperature for 24 h. Finally, the composite was separated, washed with deionized water, and dried in an oven at 50 °C for 24 h.

2.3 General procedure for the Knoevenagel condensation using the Fe3O4–PIL nanocatalyst

In a vial equipped with a magnetic stirrer, aldehyde (1 mmol), malononitrile (1 mmol), Fe3O4–PIL nonmagnetic catalyst (0.05 g), and water (3 mL) were placed and sonicated for desired times. The progress of the reaction was monitored via TLC. Upon completion of the reaction, the catalyst was removed from the mixture with the aid of an external magnet and the filtrate was transferred to a separatory funnel. Then, dichloromethane (10 mL) was added and the obtained organic phase was separated and dried with calcium chloride and removed in vacuo. Finally, the residue was isolated by column chromatography on silica. All products were known and confirmed by comparing their physical and spectral data with the authentic samples.

2.4 Reusability test of the Fe3O4–PIL nanocatalyst in the Knoevenagel condensation

For this purpose and according to the general procedure, the conversion of 4-nitrobenzaldehyde was selected as the model and was performed under the same conditions for seven consecutive times. After completion of the reaction on each run, the catalyst was carefully separated and washed with ethyl acetate (10 mL) and reused for the next run. From the results, the reaction time increased with a gentle slope from 10 to 12 min.

3 Results and discussion

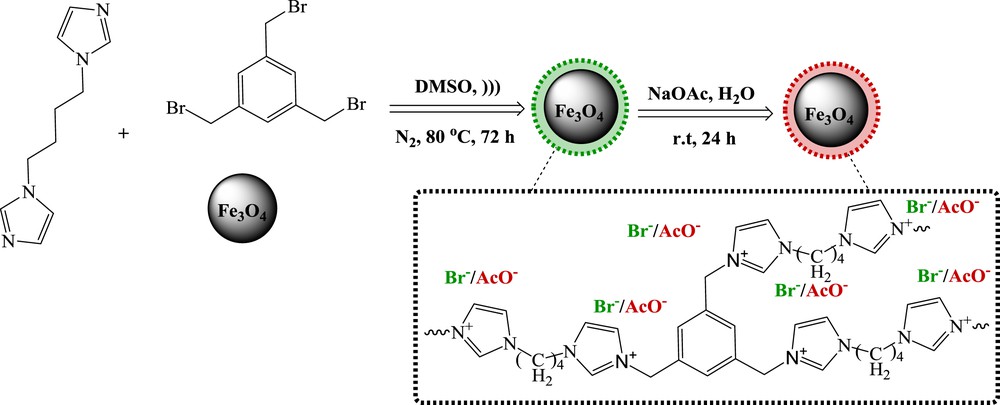

In this work, the protocol regarded to synthesize the catalyst is based on our previous experiments [24–27]. First, the Fe3O4 nanoparticles were prepared by coprecipitation method. Then, SN2 between 1,3,5-tris (bromomethyl)benzene and 1,4-bis (imidazol-1-yl)-butane was used for the formation of ionic organic network coating Fe3O4 cores, which act as a hard template generating Fe3O4–PIL composite, followed by anion exchange with sodium acetate to increase the basicity of the MNPs (Scheme 1). We assumed that coating of the ionic organic network onto Fe3O4 nanoparticles surface is achieved by electrostatic attractions between positive charge of imidazolium rings and bromide or acetate anions with oxygen and iron atoms in the magnetite crystals, respectively. Also, this modification not only prevents Fe3O4 particles from agglomeration similar to the classic, Derjaugin-Landau-Verwey-Overbeek–type coulombic repulsion model [28,29], but also increases organophilicity of magnetic particles.

Synthesis of Fe3O4–PIL composite.

Then, different physicochemical characterization techniques were used to probe the structure of the organic–inorganic composite.

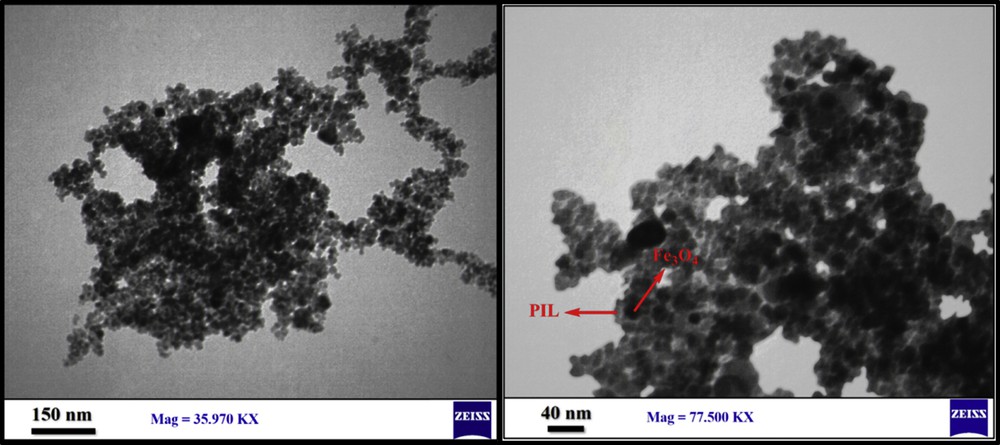

To study the size and morphology of the nanoparticles, Fe3O4–PILs were subjected to TEM and field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM). The TEM images showed that Fe3O4–PIL particles have a nearly spherical shape with the size range almost less than 20 nm (Fig. 1). In addition, dark Fe3O4 cores coated with the brighter PIL layers can be visualized.

TEM images of synthesized Fe3O4–PIL particles at the scale of 150 nm (left) and 40 nm (right).

Fig. 2 presents the FESEM image of the synthesized Fe3O4–PIL nanoparticles. As seen from the figure, the surface is rough with wrinkles. The elemental mapping indicated the good distribution of carbon (blue), nitrogen (mustard), oxygen (green), iron (red), and bromine (cyan) over the surface of Fe3O4–PIL composite.

FESEM image and SEM-energy dispersive X-Ray spectroscopy (EDS) elemental mapping images of C, N, O, Fe, and Br in Fe3O4–PIL composite.

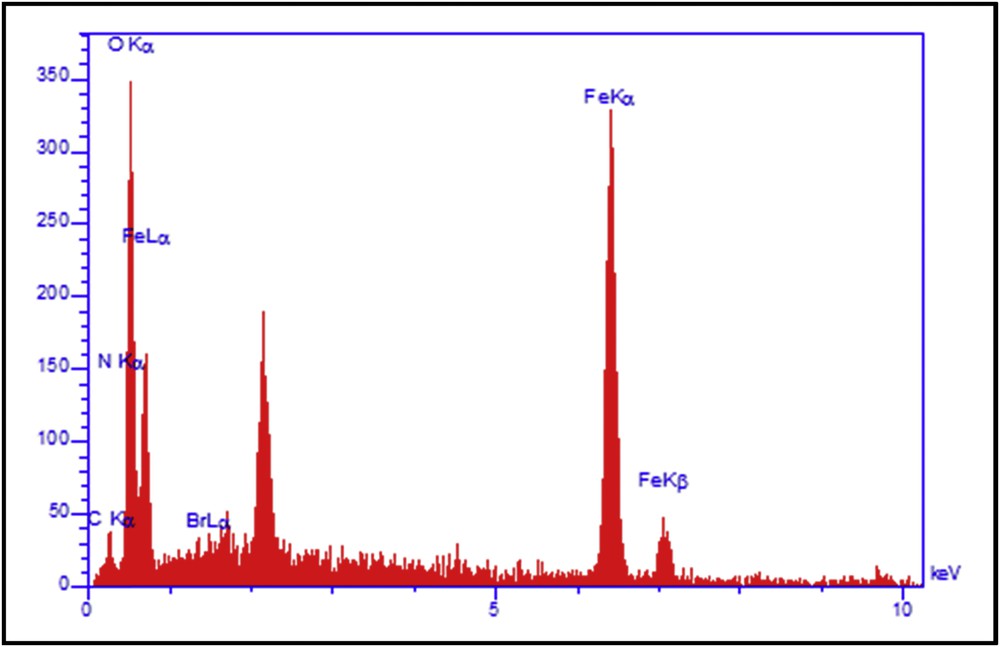

The EDS spectrum shows signals corresponding to C, N, and Br in addition to Fe and O, which further prove the presence of PIL on the surface of Fe3O4 particles (Fig. 3).

EDX of Fe3O4–PIL nanoparticles.

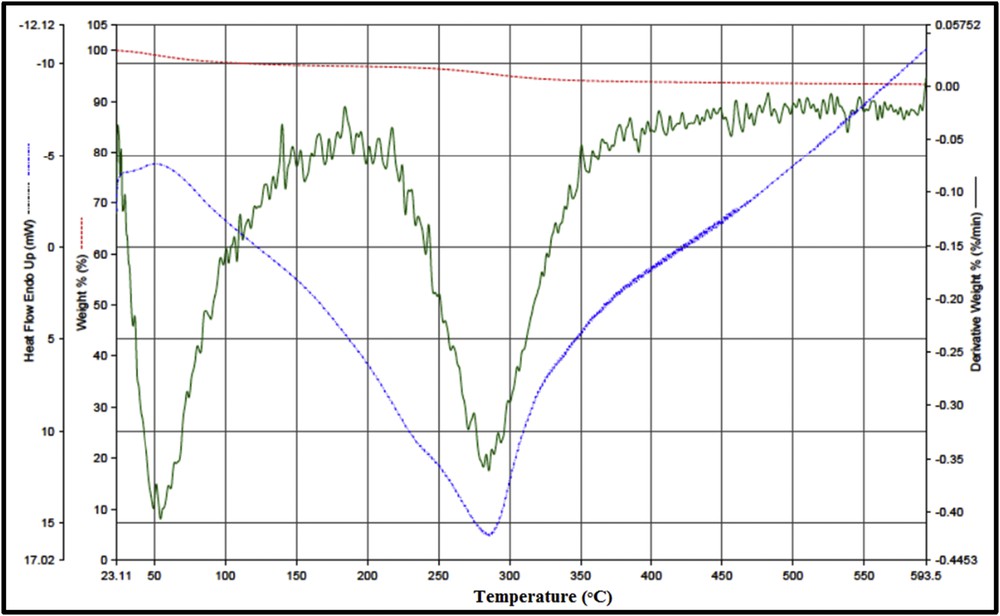

To investigate the thermal stability and determine operating temperature range of PIL@Fe3O4, TGA was carried out (Fig. 4). The combined TGA–DTG curves show weight loss from room temperature to 100 °C, which is due to the removal of physically adsorbed water and ethanol. Also, weight loss from 200 to 350 °C corresponding to the decomposition of the PIL coated on Fe3O4 particles was observed.

TG–DTG analysis for Fe3O4–PIL composite.

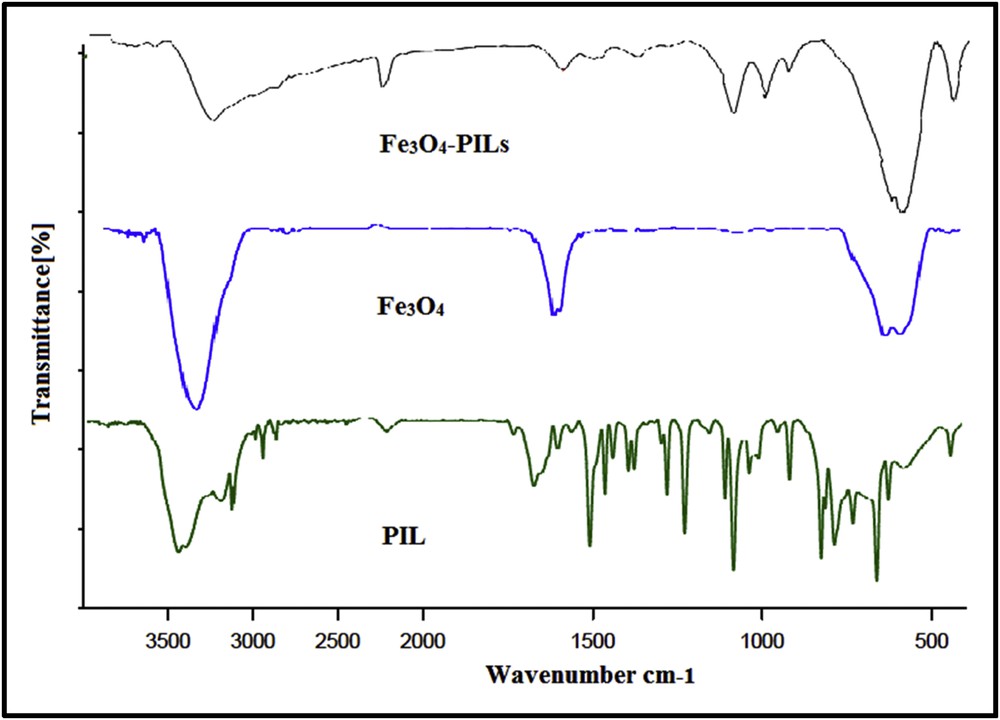

The FT-IR spectrum of the Fe3O4–PIL nanoparticles showed various peaks corresponding to Fe3O4 and PIL components (Fig. 5). The band at ∼613 cm−1 belonged to Fe-O stretching vibration in the tetrahedral sites, which is originally at ∼585 cm−1 in bare Fe3O4 and shifted after coating of PIL on the MNP surface. Also, the peaks at ∼3100 and ∼2800–2950 cm−1 and weak bands at ∼1460 and ∼1563 cm−1 were associated with aromatic C-H, alkyl C-H, CC (the benzene ring), CC and CN (the imidazole ring) stretching vibration, respectively [30]. In addition, the band at ∼1635 cm−1 and a broad one at ∼3383 cm−1 can be attributed to O–H stretching vibration of the deformation vibrations of water molecules trapped in the Fe3O4 colloidal particles and physisorbed water, respectively [31,32].

FT-IR spectra of PIL (bottom), Fe3O4 (middle), and Fe3O4–PIL (top).

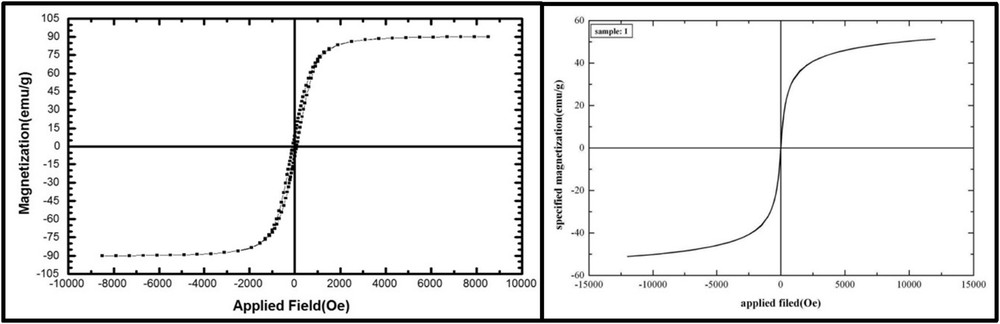

Room temperature magnetic properties of Fe3O4–PIL nanoparticles and bare MNPs were investigated (Fig. 6). The superparamagnetic characteristics of the two samples were proved because the M (H) hysteresis loops for the two samples were completely reversible. Also, Fe3O4–PIL and uncoated Fe3O4 nanoparticles presented saturation magnetization values of about 50 and 90 emu g−1, respectively. This decrease is attributed to the coating of nonmagnetic PIL over MNPs.

Hysteresis loops of MNPs (left) and Fe3O4–PIL (right).

It has been observed that ultrasound as an alternative to conventional energy sources reduces the reaction temperature and higher reaction rates can be achieved under ambient conditions [33]. Also, water is the safest of all solvents and is favorable from green chemistry viewpoint. Thus, a strong collaboration between ultrasonic irradiation and aqueous medium holds the key to the development of an environmentally sustainable protocol [34].

Accordingly, we investigate the reaction of 4-nitrobenzaldehyde with malononitrile under ultrasonic condition in water. To our delight, products were obtained in 94% yield when 0.05 g of Fe3O4–PIL catalyst was used (more details on optimization of the reaction conditions are provided in Table 1, entry 2). With the knowledge of optimized reaction conditions, a series of substituted aldehydes with electron-donating and electron-withdrawing groups were investigated in the Knoevenagel condensation and fortunately provided excellent yields (Table 1, entries 1–15).

Knoevenagel reaction of aromatic aldehydes catalyzed by Fe3O4–PIL in water under ultrasound condition.

| Entry | Aldehyde | Yield (%)a |

| 1 | Benzaldehyde | 92 |

| 2 | 4-Nitrobenzaldehyde | 94, Trace,b 30,c 65,d 45e |

| 3 | 4-Bromobenzaldehyde | 92 |

| 4 | 4-Hydroxybenzaldehyde | 82 |

| 5 | 4-Cyanobenzaldehyde | 92 |

| 6 | 4-Fluorobenzaldehyde | 91 |

| 7 | 4-Chlorobenzaldehyde | 94 |

| 8 | 2-Furaldehyde | 91 |

| 9 | 4-Methoxybenzaldehyde | 83 |

| 10 | 2,4-Dichlorobenzaldehyde | 86 |

| 11 | 4-Methylbenzaldehyde | 80 |

| 12 | 2-Chlorobenzaldehyde | 85 |

| 13 | 2,4-Dimethoxybenzaldehyde | 77f |

| 14 | 3-Nitrobenzaldehyde | 94 |

| 15 | 4-(Dimethylamino)benzaldehyde | 72 |

a Yields refer to chromatographically pure material.

b Without catalyst.

c 0.02 g of the catalyst.

d Five minutes.

e Under reflux condition.

f Fifteen minutes.

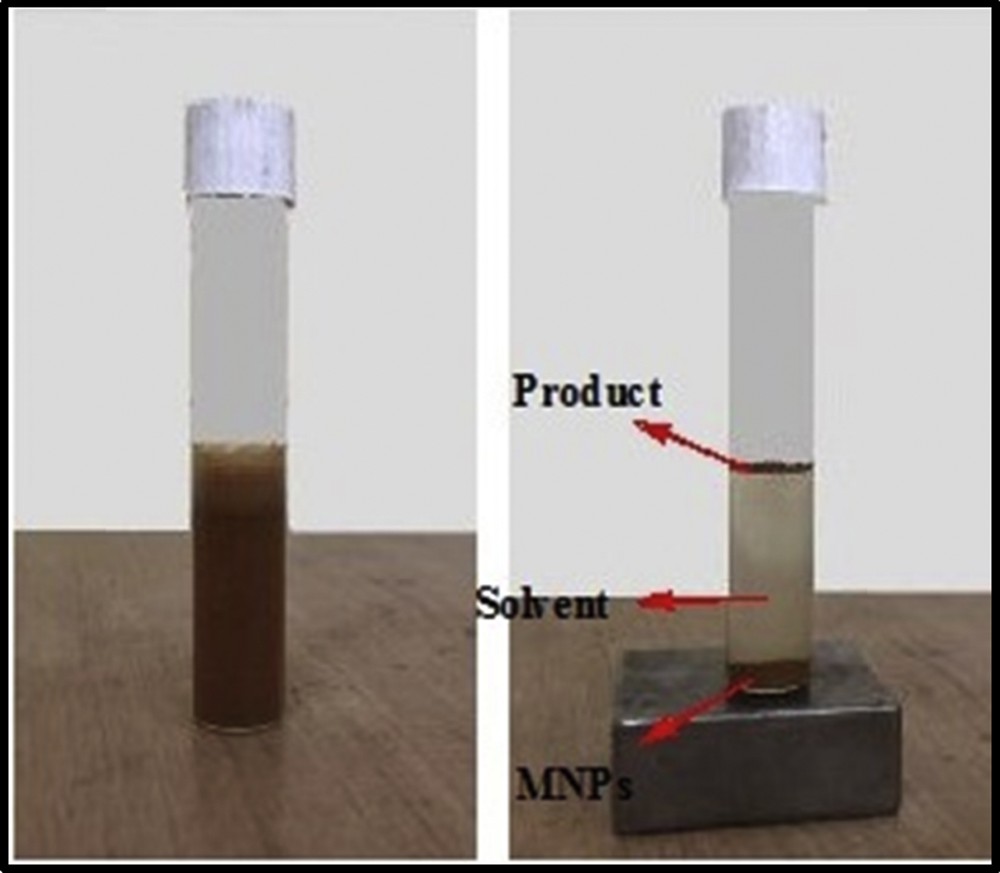

Recovery and reusability of the catalyst without losing its activity is an important feature of the use of MNPs as a catalyst support in organic synthesis [35–37]. This feature was successfully investigated (Fig. 7 and Section 2).

Separation of the MNPs from reaction media with an external magnet.

4 Conclusions

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first synthetic report of the poly ionic network coated on MNPs. This new nanocomposite presented high catalytic activity and robustness for the Knoevenagel condensation reaction in addition to easy magnetic separation and filtration, and recyclability. The catalyst could be recycled seven times without significant loss of activity.

Acknowledgments

We are sincerely grateful to the Ahvaz Branch, Islamic Azad University, for the financial support of this project.