1. Introduction

Fluoropolymers are niche macromolecules regarded as irreplaceable materials, endowed with exceptional chemical, thermal, electrical, optical, and UV resistance properties. Hence, they have found many applications in high-tech domains, such as aerospace, automotive, internet of things, optics and electronic industries [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6]. Many specific items such as high performance elastomers, stable cables in photonics (core and cladding in optical fibers), chemically resistant membranes for desalination or in ion exchange for fuel cells, gaskets, binders for batteries in lithium (or sodium) ion batteries, lubricants for wind mills, for O-rings and diaphragms, protective paints, coatings and backsheets for photovoltaic panels [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6]. The aims of this mini-review are: (i) elucidating efficient radicals can be used to initiate (co)polymerization of one of the most manufactured monomer, vinylidene fluoride (VDF), (ii) proposing a comonomer as an efficient VDF partner and (iii) presenting applications expected from the resulting copolymers.

2. Use of fluorinated radicals to initiate the polymerization of fluoroolefins

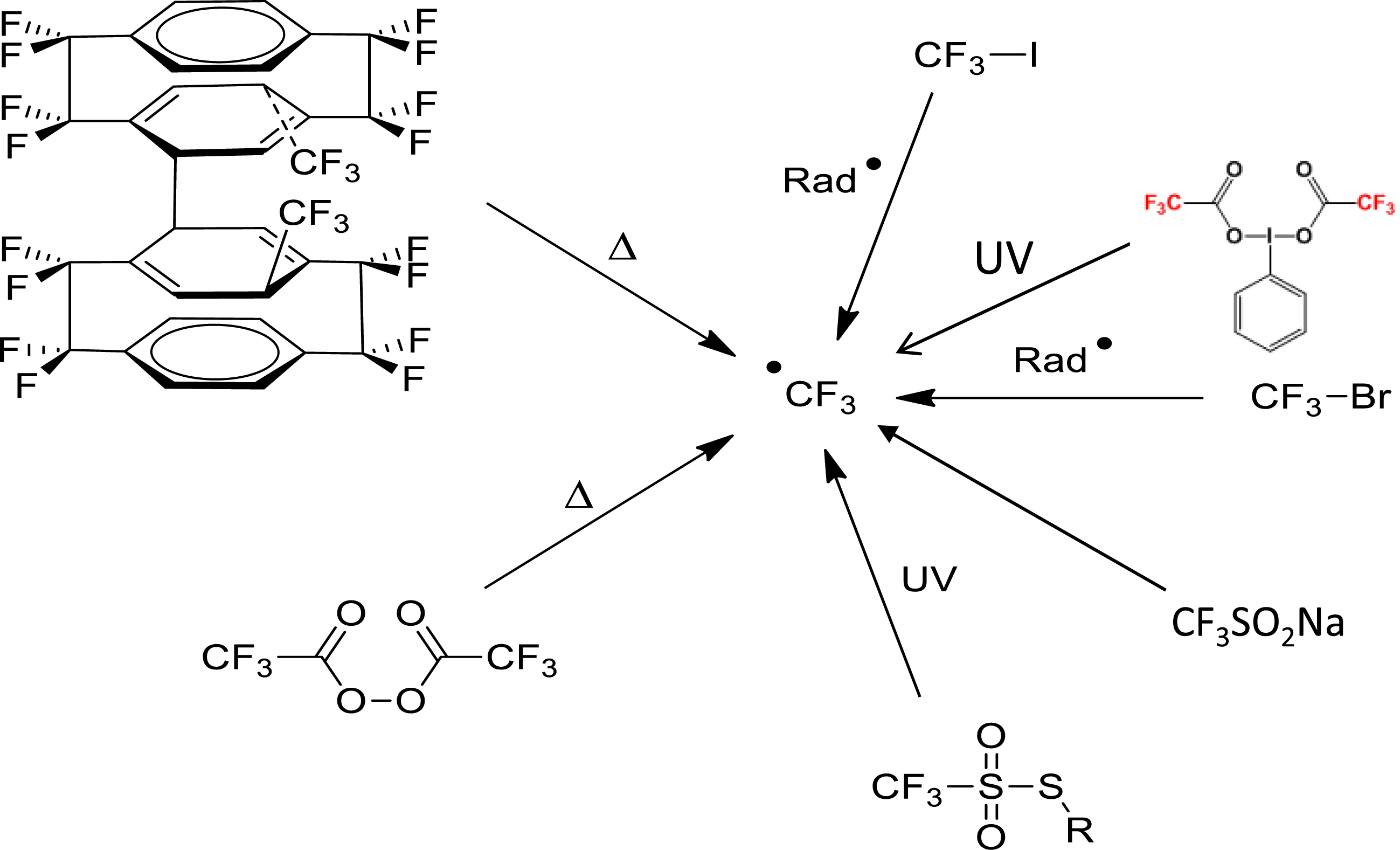

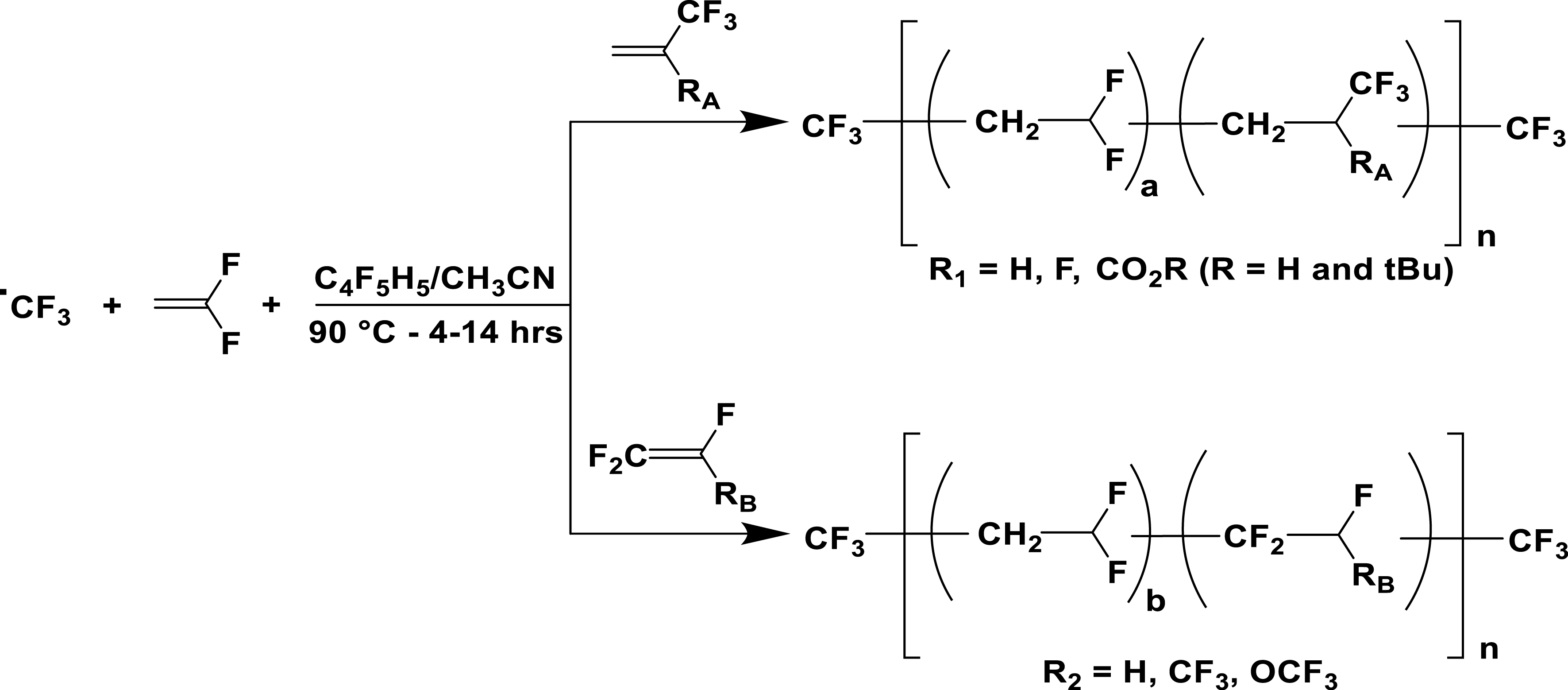

Fluoropolymers are classically prepared by radical (co)polymerization of fluoroalkenes under high pressure [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6]. While many radical initiators have been utilized [8], fluorinated ones have already demonstrated their high efficiency to initiate such a reaction. A distinct example is the trifluoromethyl radical which can be released from various reactants (Scheme 1). This halogenated radical and its addition to fluoroalkenes was comprehensively studied by Tedder and Walton [9].

Non-exhaustive strategies to generate a trifluoromethyl radical.

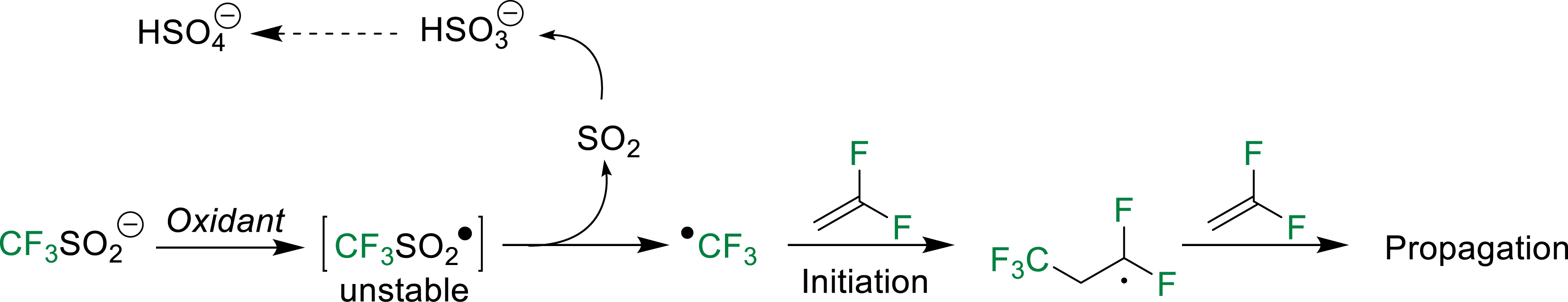

Among reactants, trifluoromethyl sulfinate (CF3SO2Na) enables generation of °CF3 radical in the presence of an oxidant (Scheme 2) but has scarcely been used to initiate the radical polymerization of fluoroolefins [7]. Typically, in aqueous polymerization processes, persulfates are suitably used as oxidants to favor the (co)polymerization(s) of VDF with hexafluoropropylene (HFP) and/or perfluoromethyl vinylether (PMVE).

Mechanism of oxidation of trifluoromethyl sulfinate, leading to the generation of ∙CF3 radicals [7].

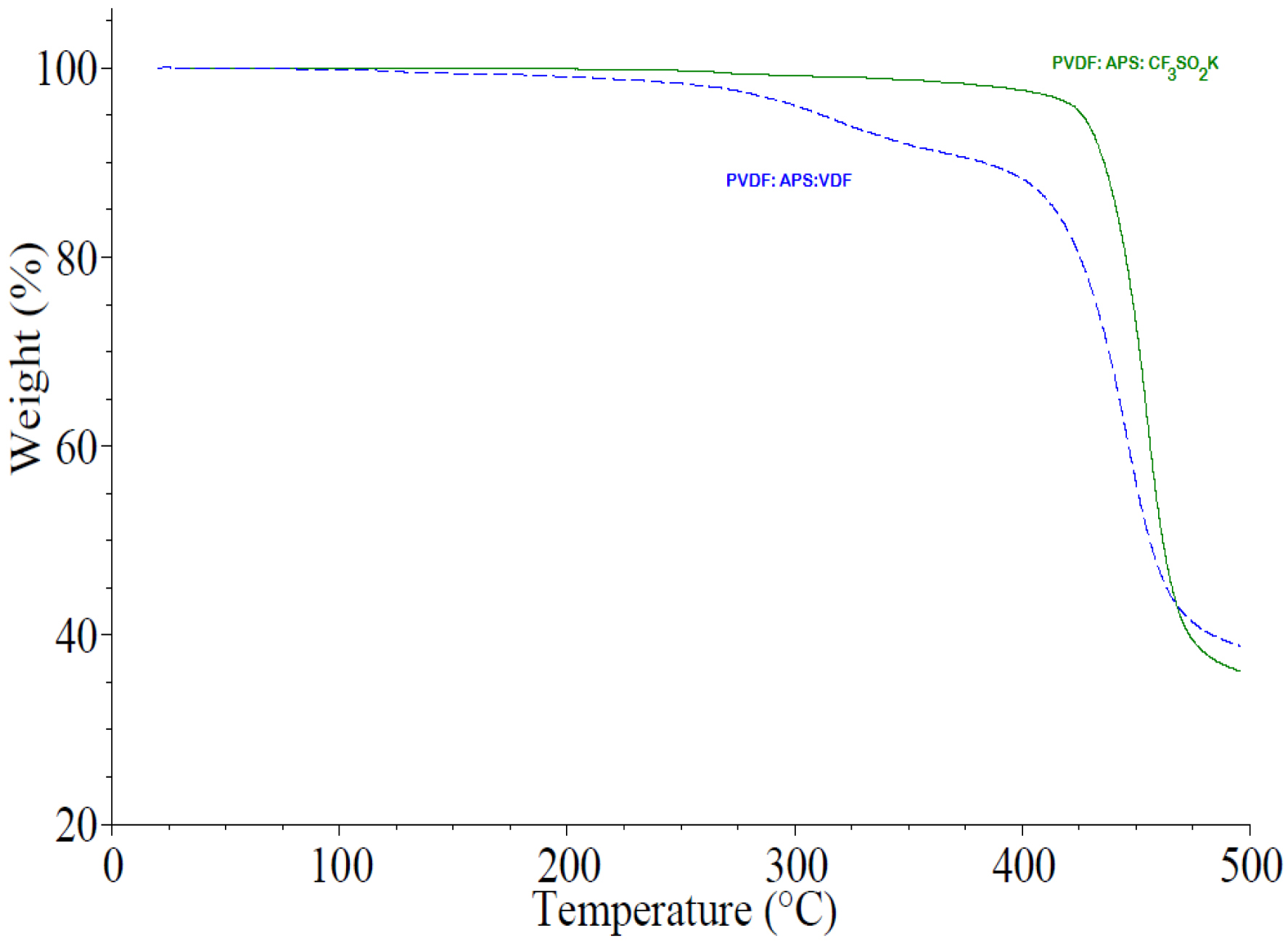

One of the main insights gleaned from this strategy is that the resulting fluoropolymers (e.g., PVDF [7]) displays a higher thermal stability than those synthesized from conventional persulfates (Figure 1) since CF3 end group slows down the “unzipping” depolymerization of such fluoropolymers.

TGA thermograms of PVDF achieved in various initiations: ammonium persulfate (APS only, dotted line) and potassium trifluorosulfinate with CF3SO2K: APS (0.9: 1.0), full line) under nitrogen (reproduced with permission from Amer. Chem. Soc. [7]).

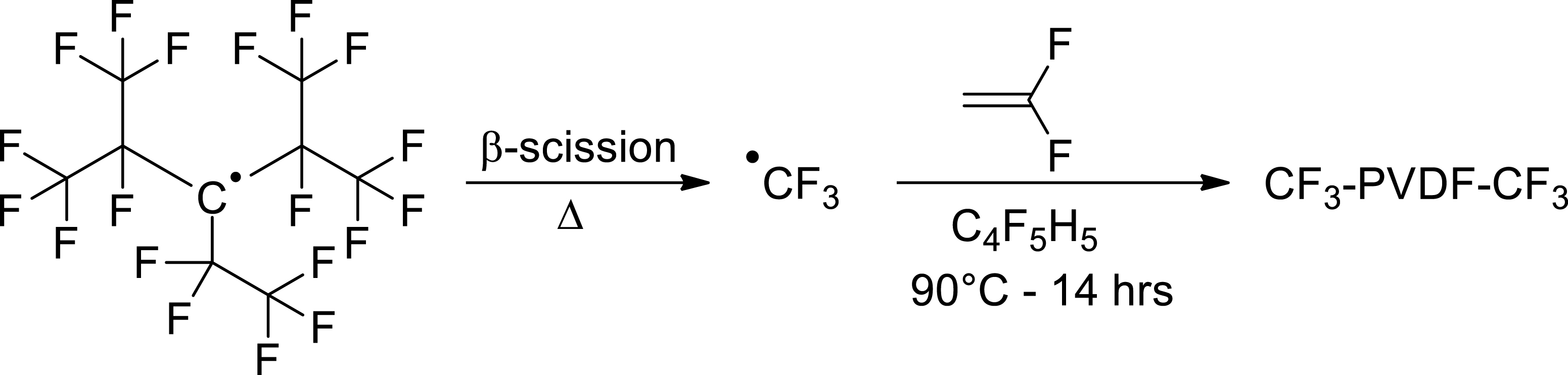

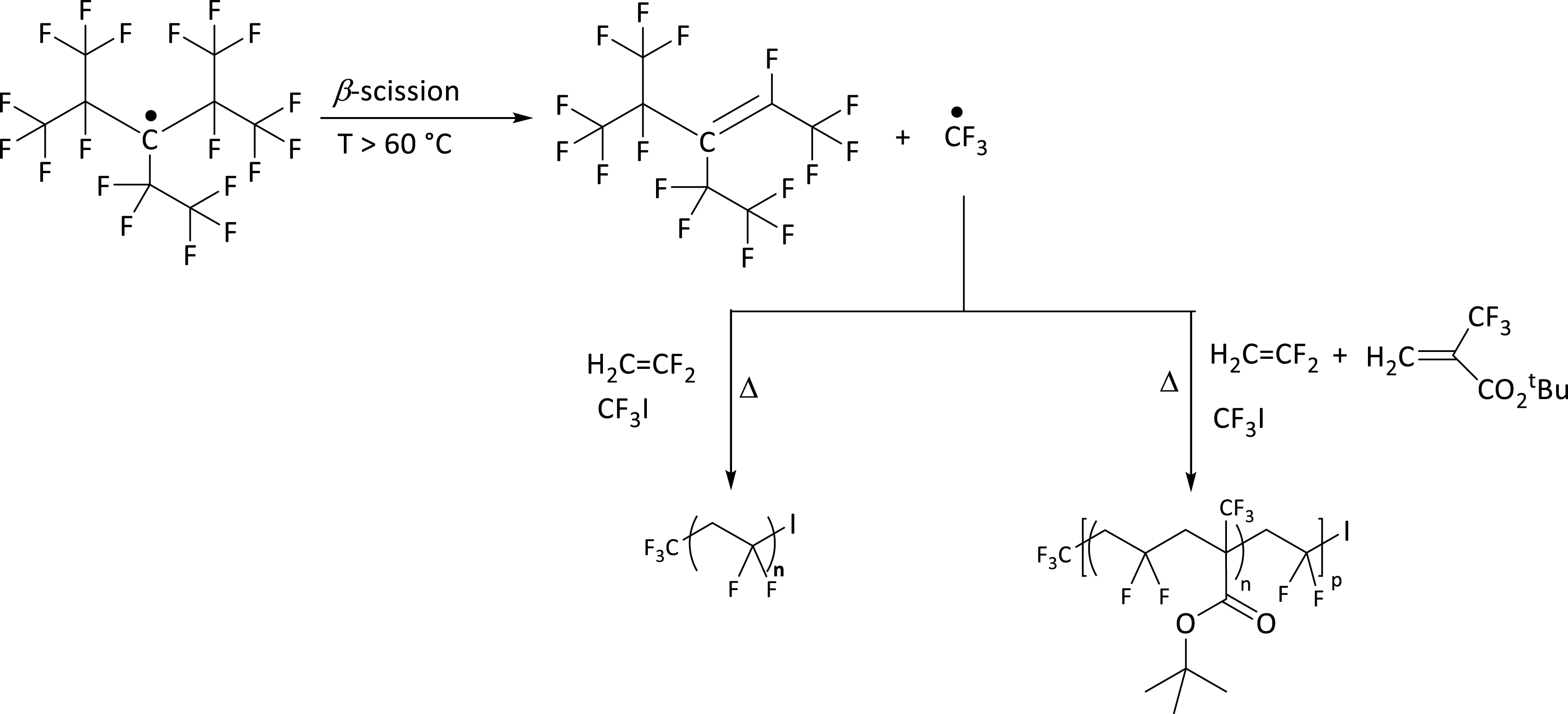

As displayed in Scheme 1, various fluorinated reactants can release trifluoromethyl radical, which can also be generated at T > 80 °C from perfluoro-3-ethyl-2,4-dimethyl-3-pentyl persistent radical (PPFR) at stable room temperature (Scheme 3) [10, 11], or from by using CF3I as a chain transfer agent involved either in telomerization [12] or in iodine transfer (co)polymerization of fluoroolefins [13]. This strategy was also extended to copolymerization of VDF with a wide range of fluoroolefins (Scheme 4) [14].

Perfluoro-3-ethyl-2,4-dimethyl-3-pentyl persistent radical (PPFR) generates a trifluoromethyl radical capable of initiating radical polymerization of VDF [10, 11].

Radical copolymerization of VDF with various comonomers initiated by PPFR [14].

Following these findings, the simultaneous use of PPFR and iodinated chain transfer agents (CTAs) can enable the obtaining of 𝜔-iodo and telechelic diiodo vinylidene fluoride (VDF)-based (co)polymers [15, 16, 17] (Scheme 5). Different CTAs, such as trifluoroiodomethane and 1,4-diiodoperfluorobutane, were used with/without tert-butyl 2-trifluoromethacrylate (MAF-TBE). All of the obtained (co)polymers were characterized by 1H and 19F NMR spectroscopies and their thermal properties were assessed.

Strategic routes to obtain PVDF-I and poly(VDF-co-MAF-TBE)-I from PPFR, a persistent radical at RT, which releases a ∙CF3 radical from 60 °C. (PVDF, PPFR and MAF-TBE stand for polyvinylidene fluoride, perfluoro-3-ethyl-2,4-dimethyl-3-pentyl persistent radical and tert-butyl 2-trifluoromethacrylate, respectively) [13].

A mechanistic investigation of these reactions evidenced the competitive presence of CF3 end group in CF3-PVDF-I originating from the CTA and showed a negligible amount of CF3-PVDF oligomer dead chains produced by the direct initiation from ∙CF3 radical (released by PPFR) onto VDF. Very low chain defects of chaining (i.e., reversed –CH2CF2–CF2CH2– and –CF2CH2–CH2CF2– in VDF–VDF dyads, even the absence of latter types) led to high melting points (161–173 °C) of the resulting polymers [13].

3. Radical copolymerization of vinylidene fluoride (VDF) with 2-trifluoromethacrylates

3.1. Introduction

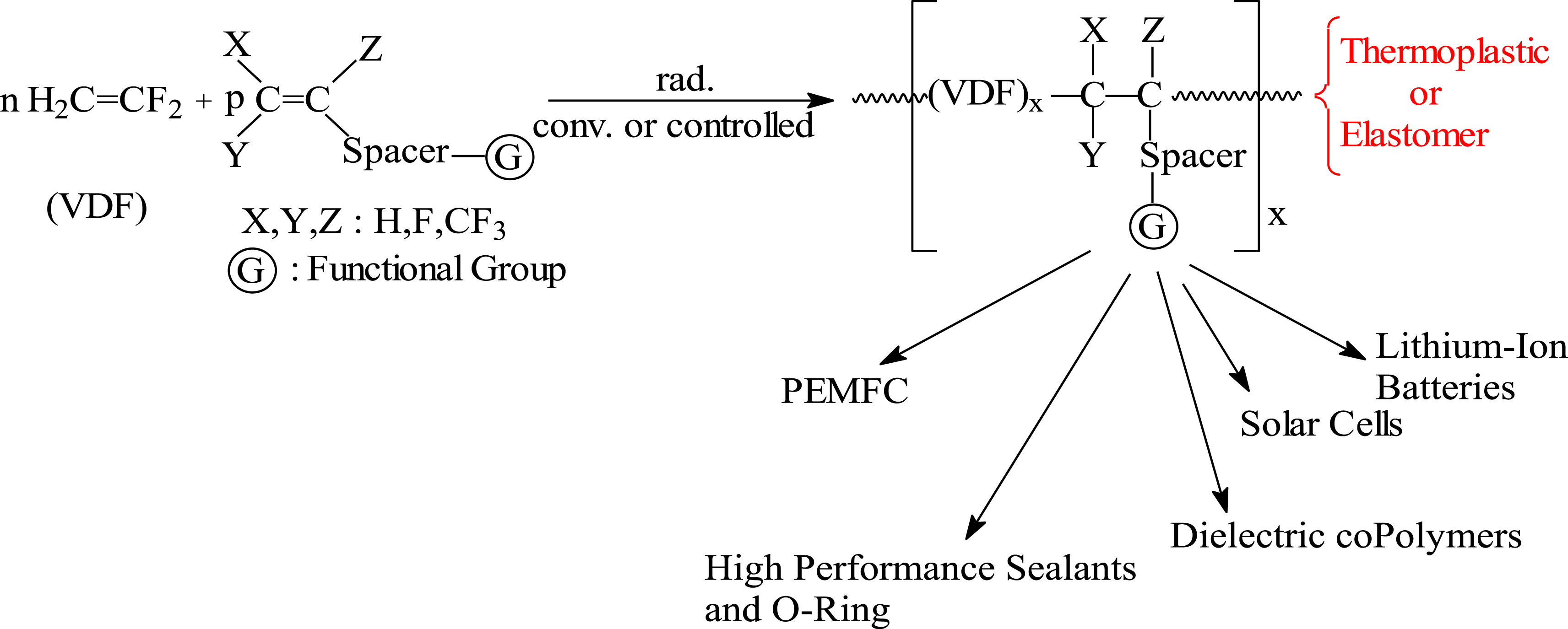

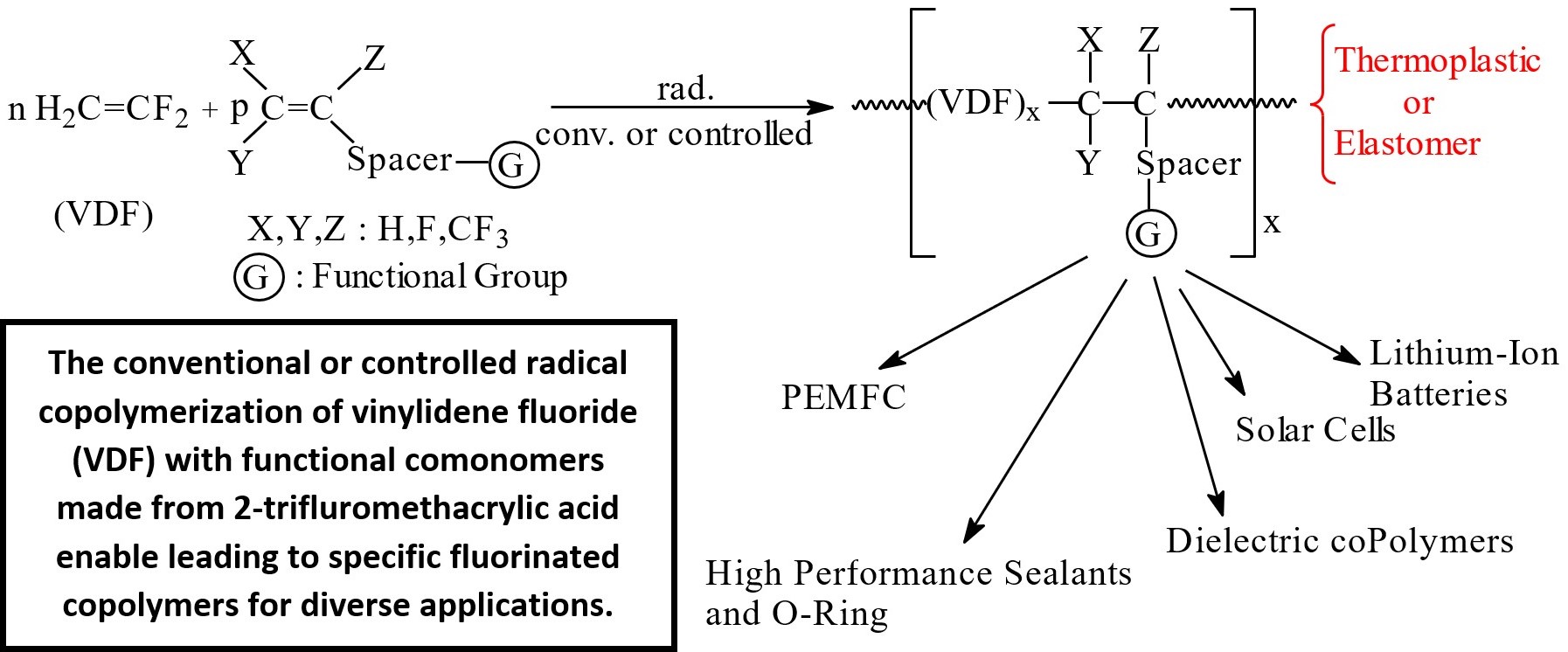

VDF has been copolymerized with a wide range of fluorinated or non-halogenated monomers [18] (Scheme 6), Q–e Alfrey and Price parameters [19, 20] to fine-tune the efficiency of the reaction.

Conventional or controlled (RDRP) radical copolymerization of VDF with functional comonomers and use of the resulting copolymers for diverse applications [18].

3.2. Copolymerization of VDF with 2-trifluoromethacrylic acid

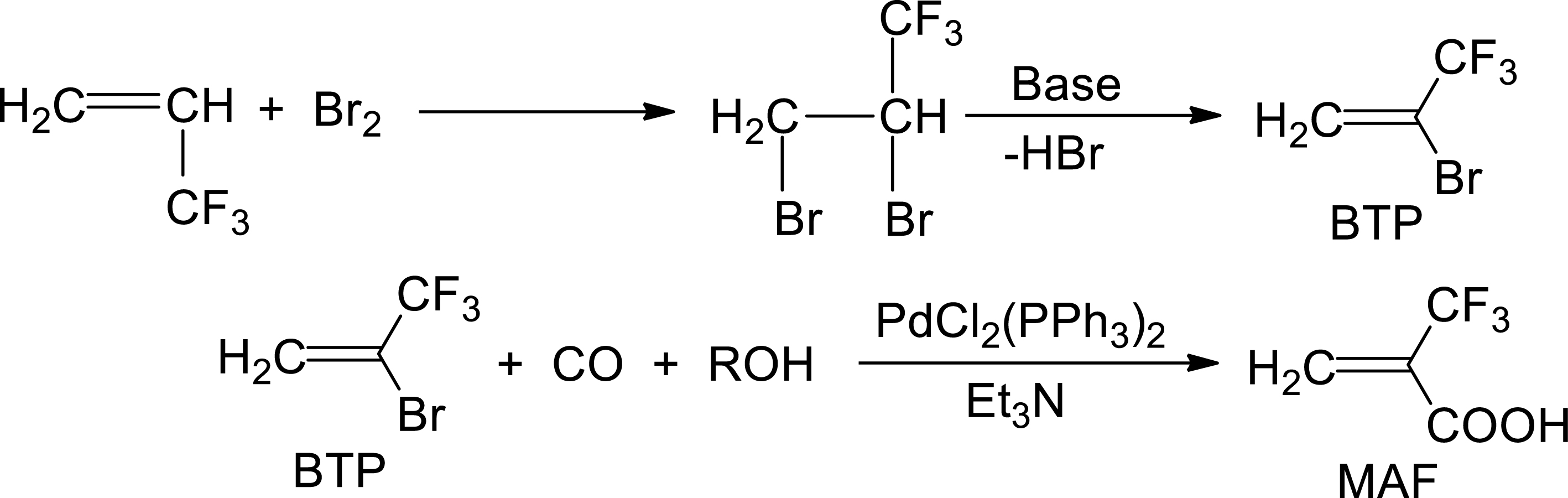

Among functional comonomers, 2-trifluoromethacrylic acid (MAF), discovered by Ojima et al. in the early 80s (Scheme 7) [21] and later manufactured by the Tosoh Finechem Corp. (ex-Tosoh F-Tech), has shown an efficiency leading to a wide range of materials [22, 23] including polymer electrolytes for Lithium-ion batteries [24] and polymer exchange membranes for fuel cells [25, 26].

Synthesis of 2-trifluoromethacrylic acid (MAF) from bromination of 3,3,3-trifluoropropene and further steps [21].

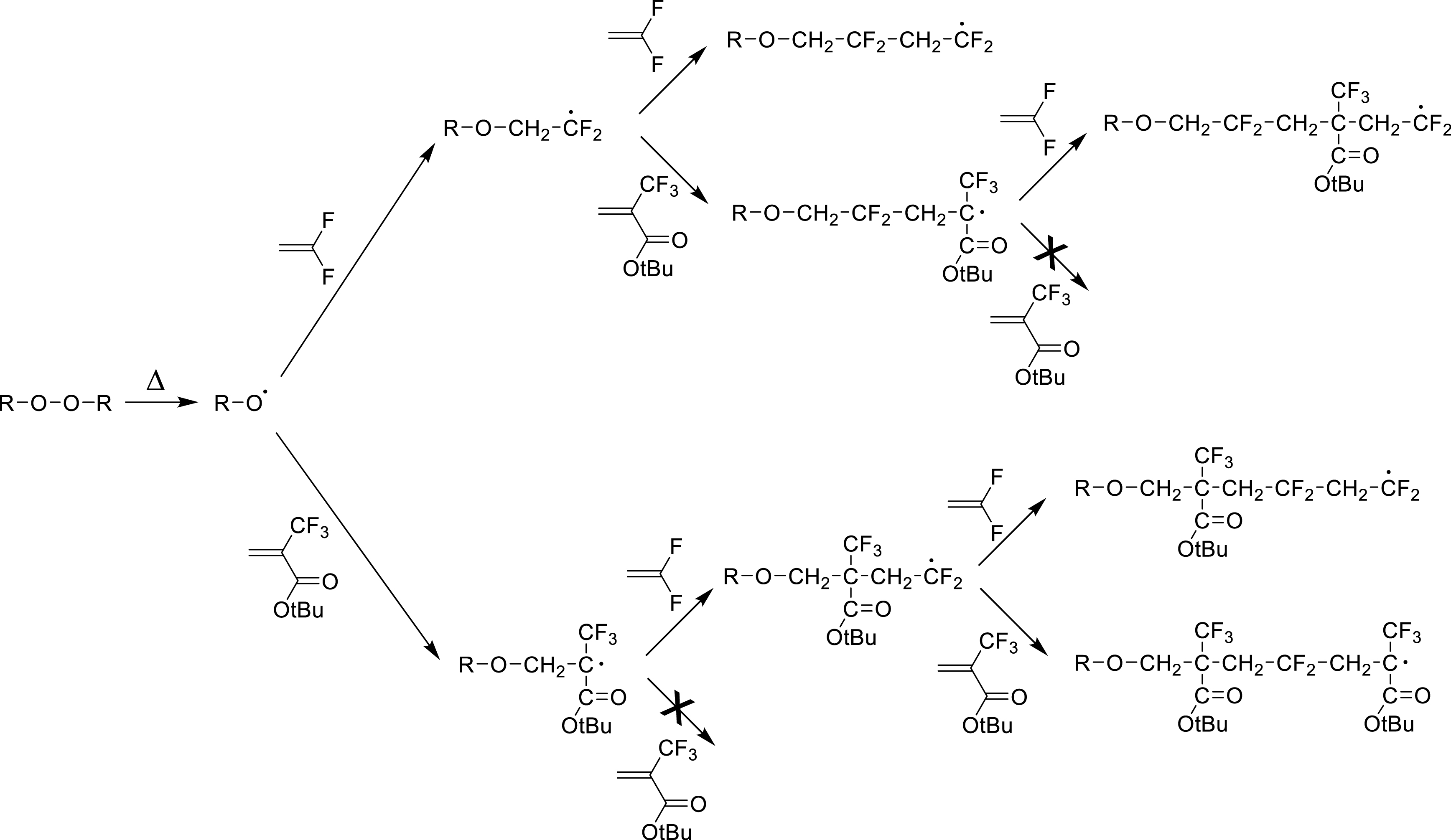

Among the first series, functional 2-trifluoromethacrylates (MAF-funcs) have been shown to be suitable partners to VDF [22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27]. Interestingly, though this monomer cannot homopropagate under radical polymerization, tert-butyl 2-trifluoromethacrylate (MAF-TBE) is quite efficient in copolymerization with VDF leading to quasi-alternating copolymers, as displayed in Scheme 8 that mainly highlights crosspropagation steps. Their reactivity ratios were calculated to be: rVDF = 0.040 and rMAF‐TBE = 0.036 at 57 °C [27].

Mechanism of alternating radical copolymerization of VDF with MAF-TBE (reproduced with permission from RSC [27]).

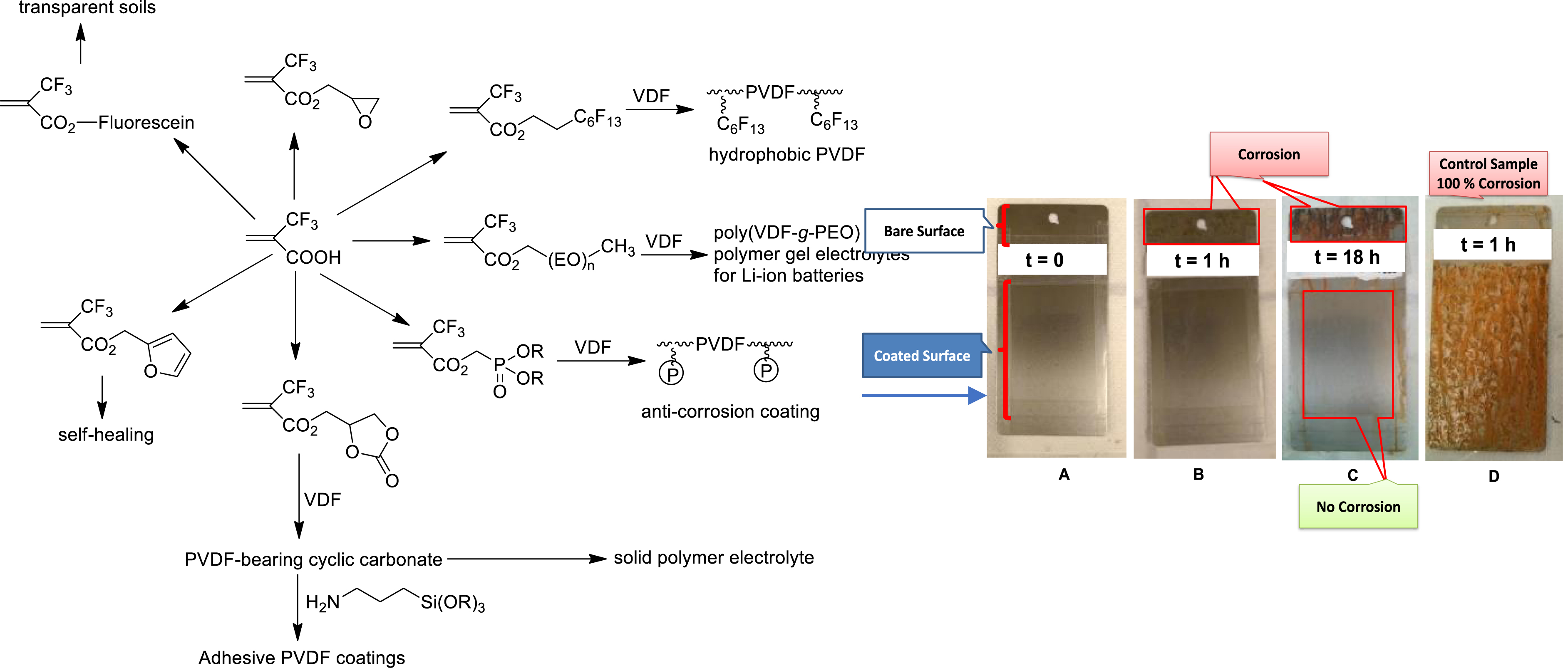

A wide variety of MAF-func monomers were synthesized from the condensation of MAF acid chloride onto functional alcohol (Figure 2) [22, 24, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32].

Overall strategies to synthesize novel functional 2-trifluoromethyl monomers from MAF and their radical copolymerization with VDF (left). Steel plates coated with poly(VDF-co-MAF Phosphonate) copolymer at the beginning of the experiment (A), after 1 h (B), and after 18 h (C). (D) Uncoated steel plate as reference sample after 1 h (right).

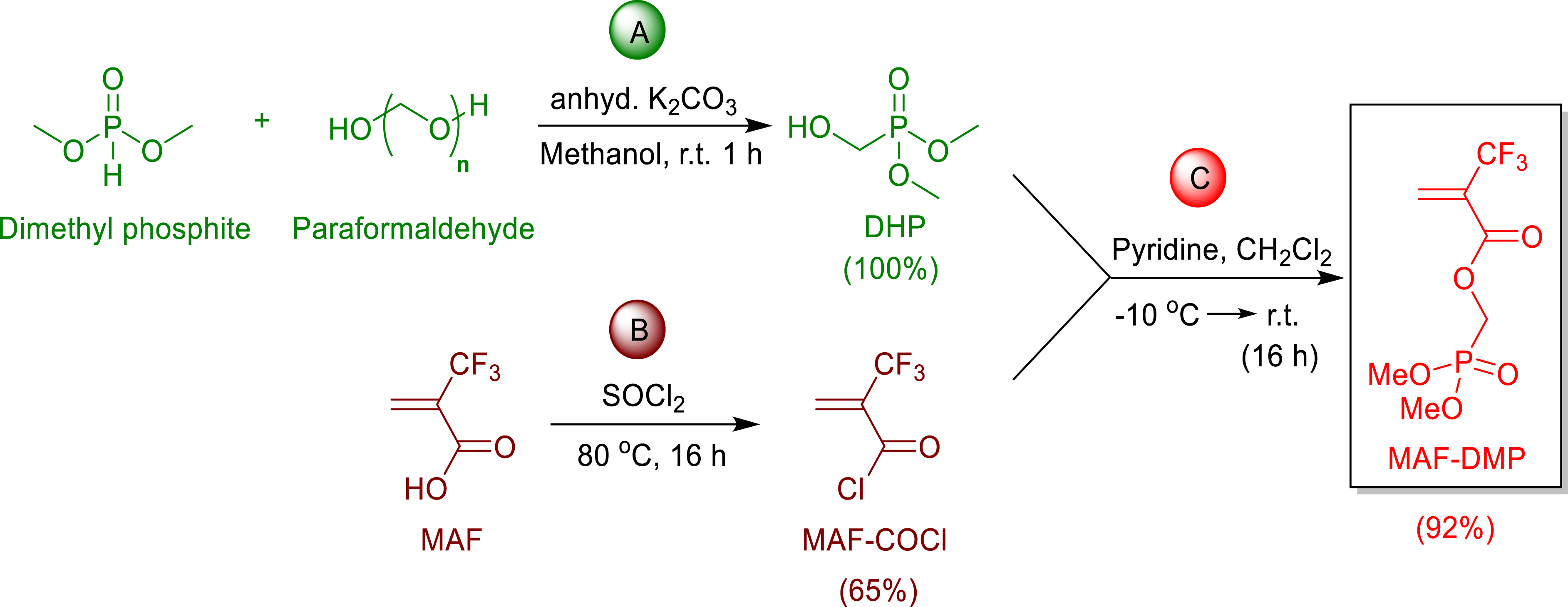

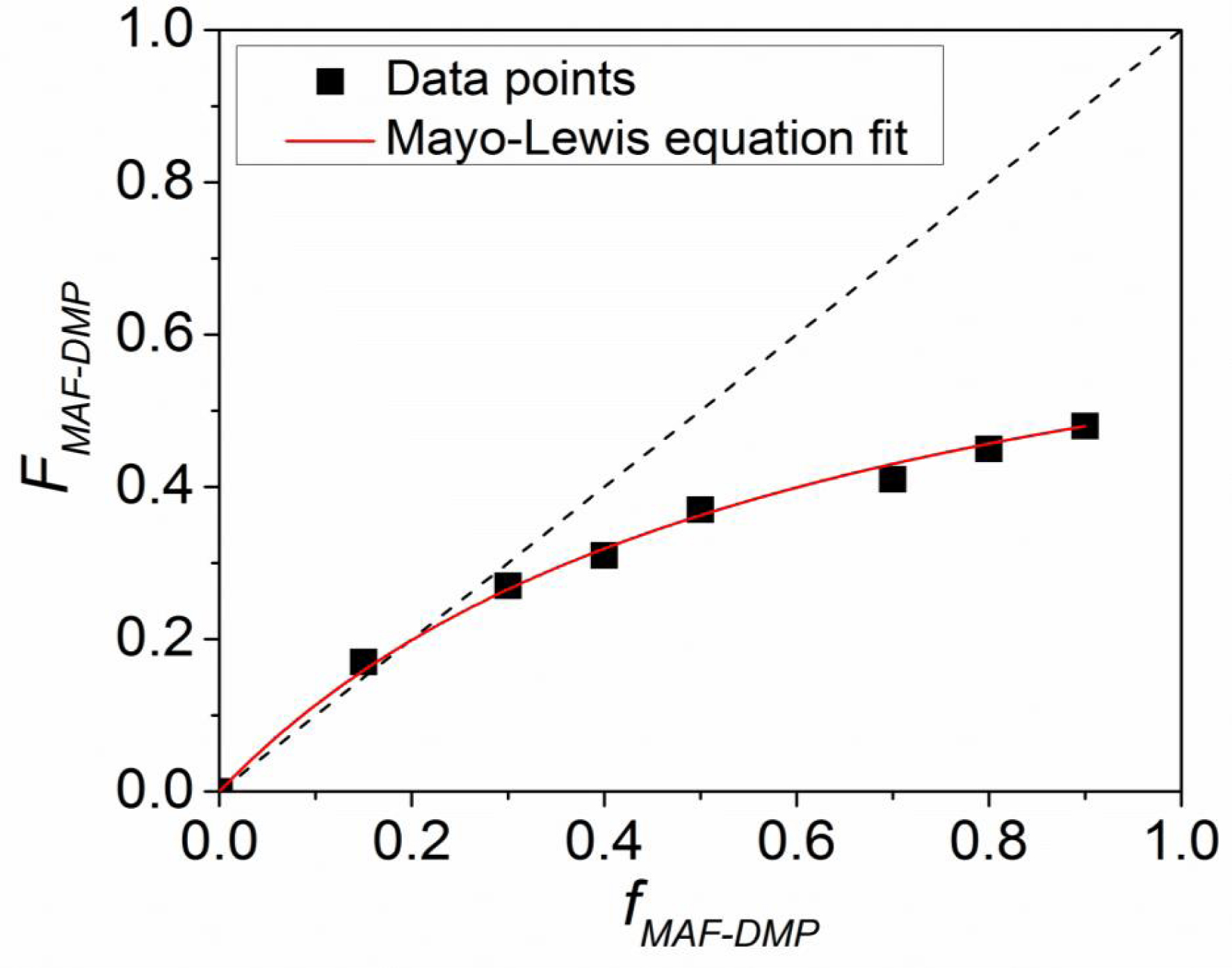

As an example, dimethyl phosphonate 2-trifluoromethyl acrylate (MAF-DMP) was prepared in two steps. First, paraformaldehyde was reacted with dimethyl phosphite to afford 2-hydroxydimethyl phosphonate [30]. Then, the latter was condensed onto MAF acryloyl chloride to yield such a MAF-DMP (Scheme 9), the kinetics of copolymerization of which led to the reactivity ratios (rVDF = 0.76 ± 0.34 and rMAF‐DMP = 0 at 74 °C [30], determined using Mayo-Lewis law from the data listed in the diagram of composition (Figure 3).

Synthesis of dimethyl phosphonate 2-trifluoromethyl acrylate (MAF-DMP) by condensation of MAF acroyl chloride onto 2-hydroxy dimethyl phosphonate [30].

Diagram of composition during radical copolymerization of VDF with MAF-DMP at 74 °C [30].

The application of such original poly(VDF-co-MAF-DMP) copolymers deals with anticorrosion coatings of steel (Figure 2) [30]. The presence of phosphonic acid (after hydrolysis of dimethyl phosphonate function in the copolymers) enables a strong adhesion onto steel surface, the PVDF chain, making the protection.

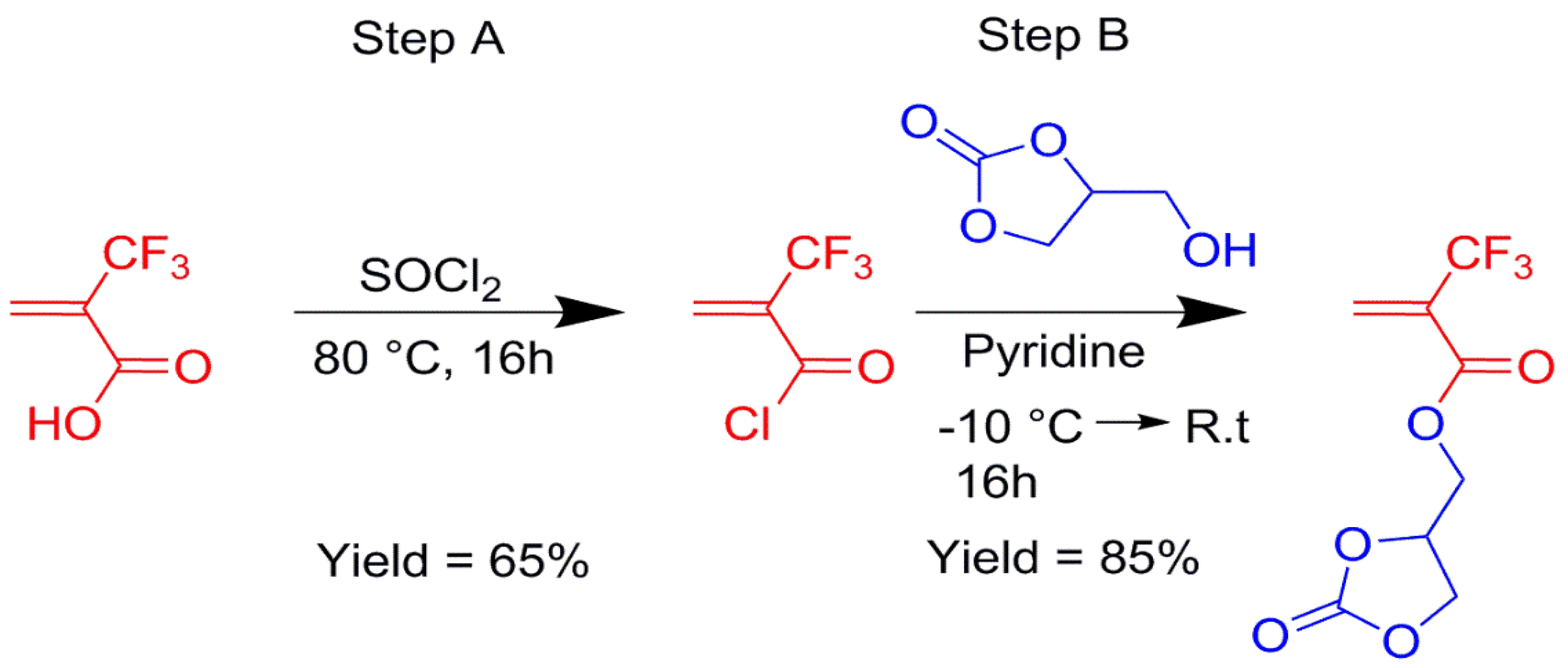

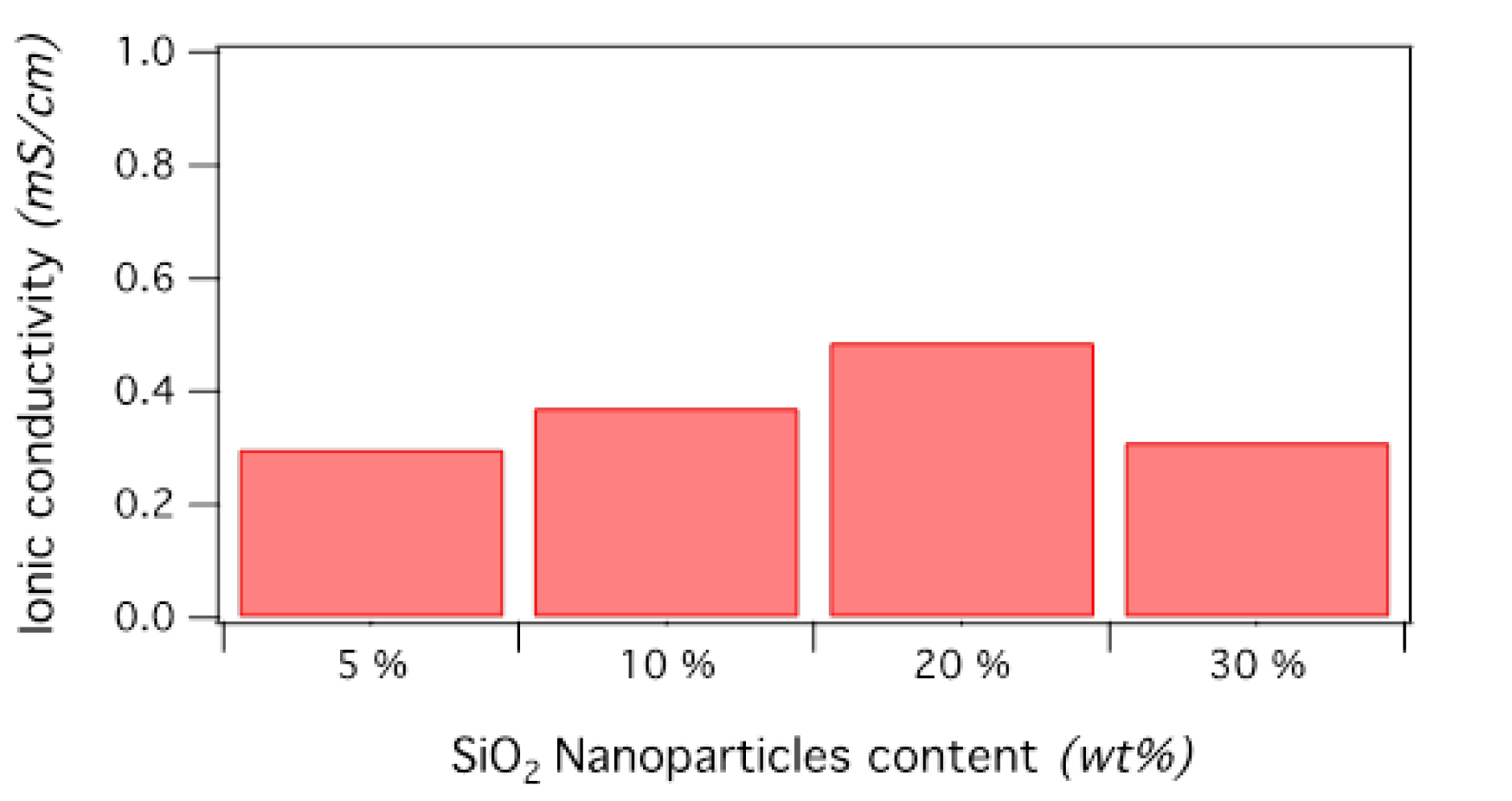

Using the same strategy, an original fluorinated monomer bearing a cyclocarbonate function, (2-oxo-1,3-dioxolan-4-yl)methyl 2-(trifluoromethyl)acrylate (MAF-cyCB), was synthesized in 70% overall yield from glycerol 1,2-carbonate (Scheme 10) [31].

Synthesis of (2-oxo-1,3-dioxolan-4-yl)methyl 2-(trifluoromethyl)acrylate (MAF-cyCB) from the condensation of glycerol 1,2-carbonate with MAF-acryloyl chloride [31].

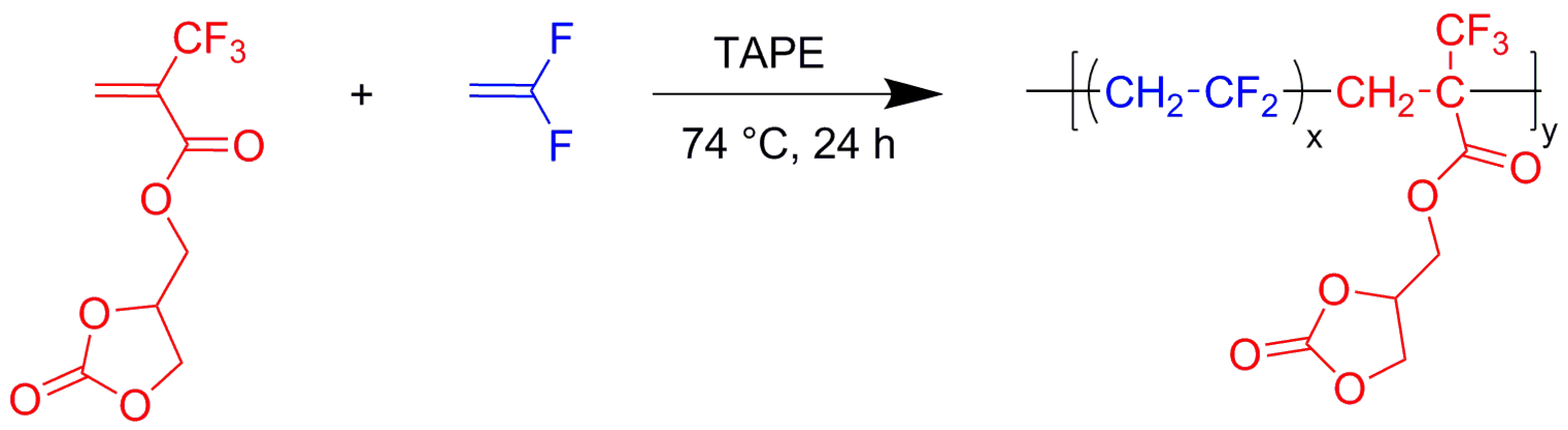

Thus, a functional monomer was successfully copolymerized with VDF under radical initiation (Scheme 11).

Radical copolymerization of VDF with (2-oxo-1,3-dioxolan-4-yl)methyl 2-(trifluoromethyl)acrylate (MAF-cyCB) initiated by tert-amyl peroxy-2-ethylhexanoate (TAPE) [24, 31].

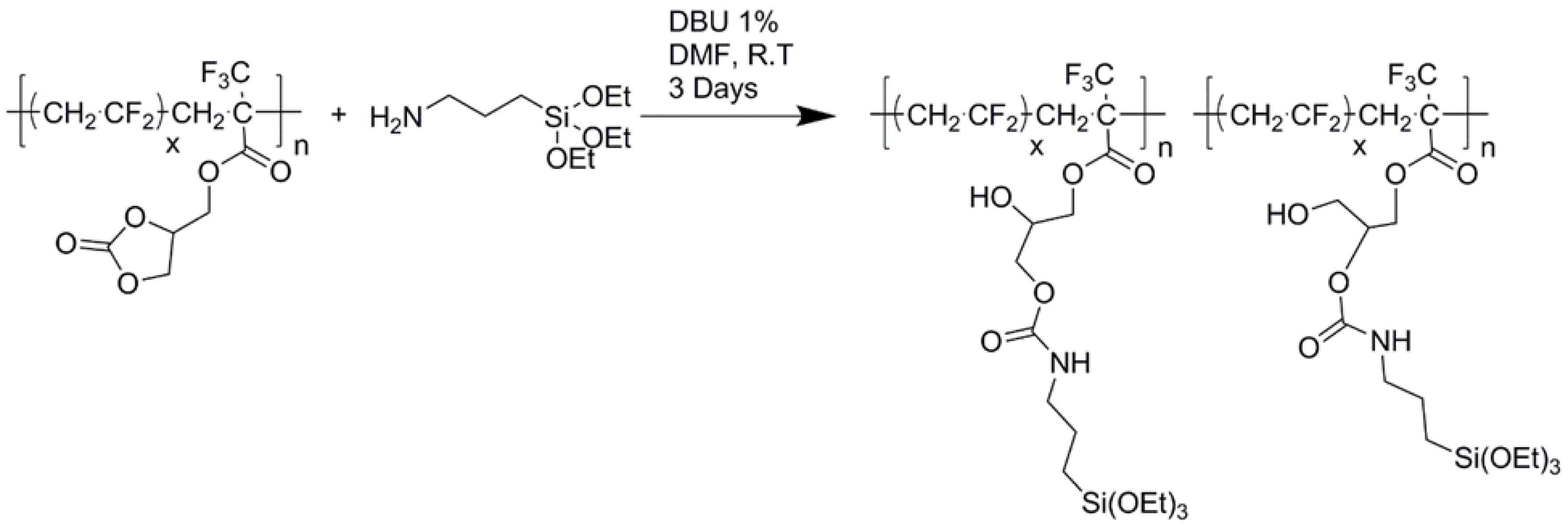

Then, the resulting copolymers were chemically modified by 3-aminopropyl triethoxysilane from the nucleophilic substitution of amino function that opens the cyclocarbonate yielding a PVDF bearing triethoxysilane side groups reinforced by a urethane link (Scheme 12) [31]. Then, hydrolysis of these trifunctional groups under acidic conditions (to avoid any dehydrofluorination of VDF units) followed by condensation led to a crosslinked network.

Chemical modification of poly(VDF-co-MAF-CyCB) copolymers by ring opening of cyclocarbonate with an aminopropyl triethoxysilane [31].

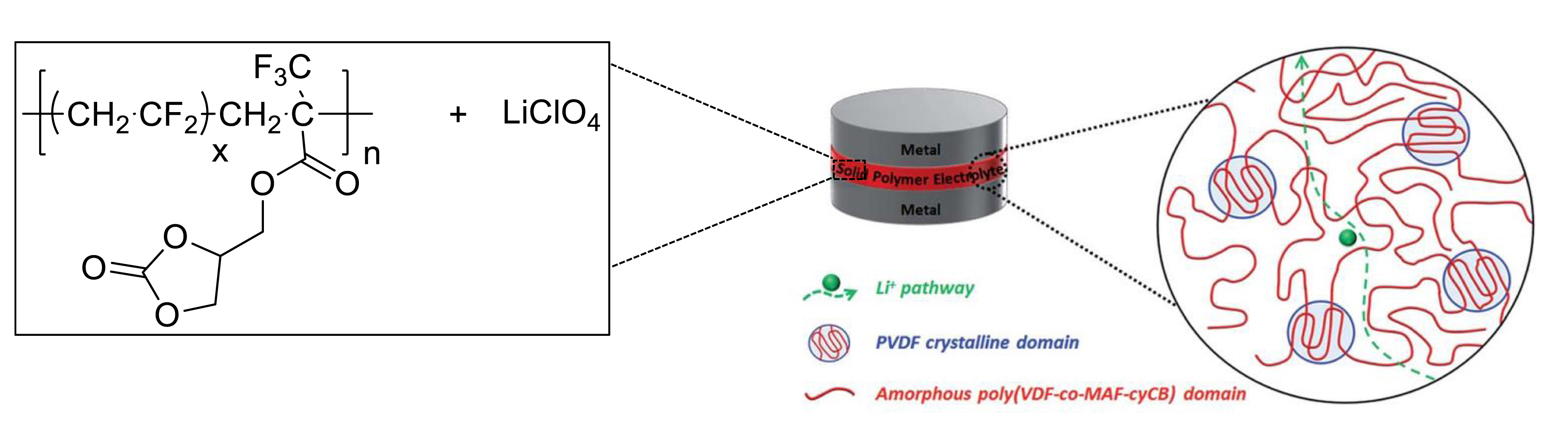

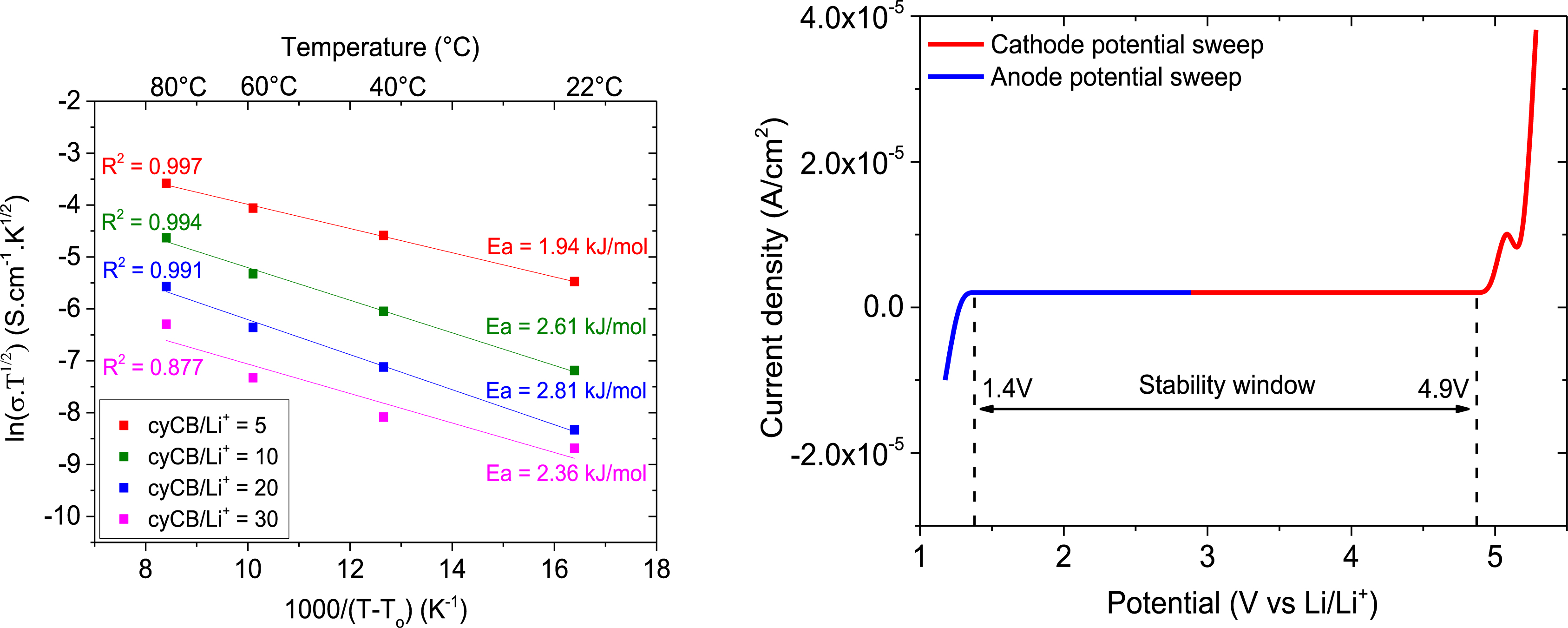

In addition, these poly(VDF-co-MAF-cyCB) copolymers were used as relevant polymer gel electrolytes dissolving Lithium perchlorate for Lithium ion batteries [24] (Figure 4), the electrochemical properties (conductivities and stability in cyclic voltammetry (Figure 5) of which were determined.

Single polymer electrolyte based on poly(VDF-co-MAF-cyCB) copolymers and LiClO4 salt for which the Li+ cation transport may occur via the amorphous state (reproduced with permission from RSC [24]).

Temperature dependence of the ionic conductivity (left) and linear sweep voltammetry curves of polymer electrolyte with cyCB/Li+ = 5. The scan rate is 0.5 mV/s (right) for the investigated SPEs using VTF model (reproduced with permission from RSC [24]).

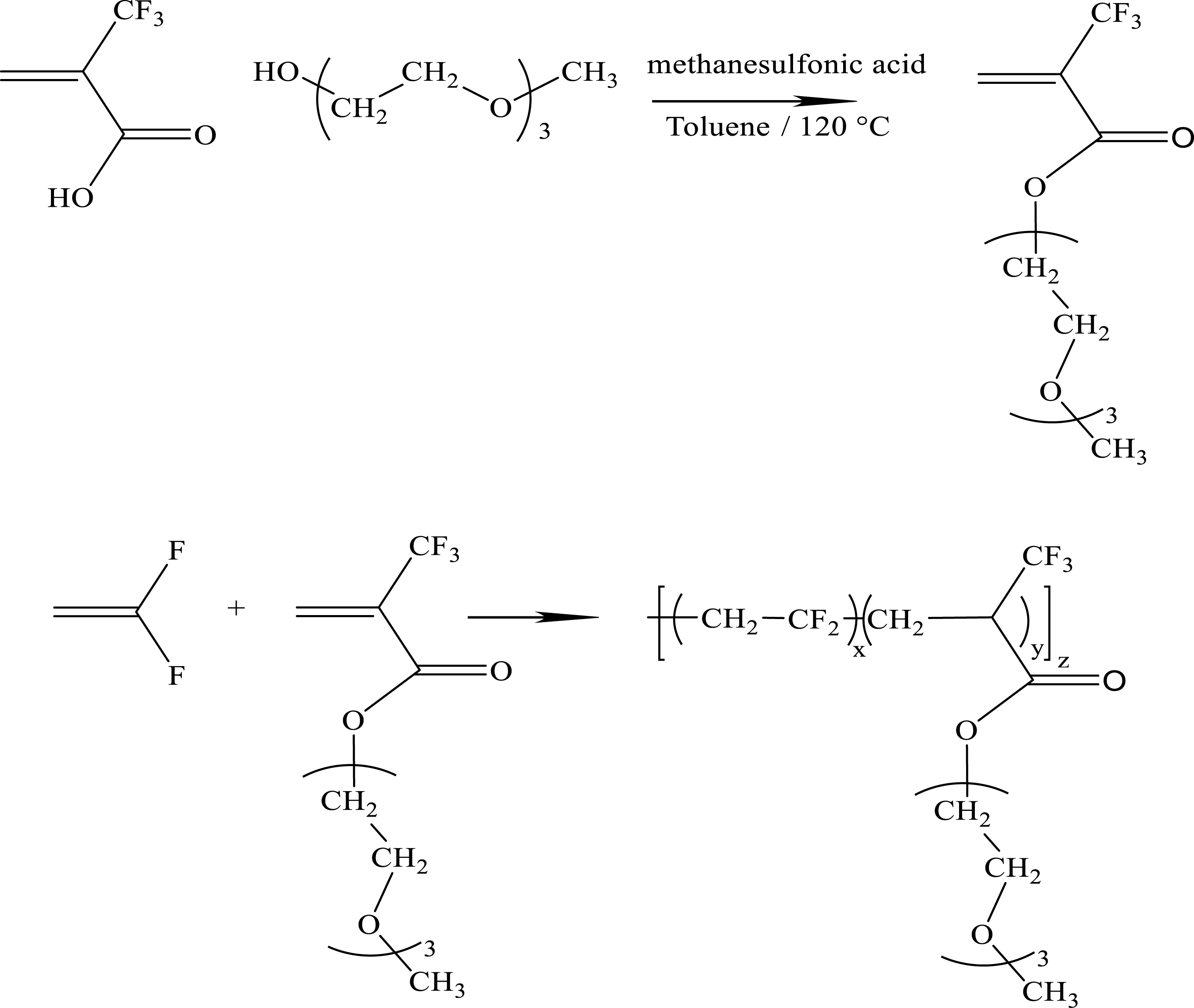

A similar strategy was also applied to PVDF bearing oligoPEG side groups [29] (Scheme 13), whose ionic conductivities are illustrated in Figure 6.

Synthesis of oligo(ethylene oxide) 2-trifluoromethyl acrylate and its radical copolymerization with VDF [29].

Ionic conductivities of PVDF-g-oligo(ethylene oxide) copolymers filled with Li salt and nanosilica (reproduced with permission from RSC [29]).

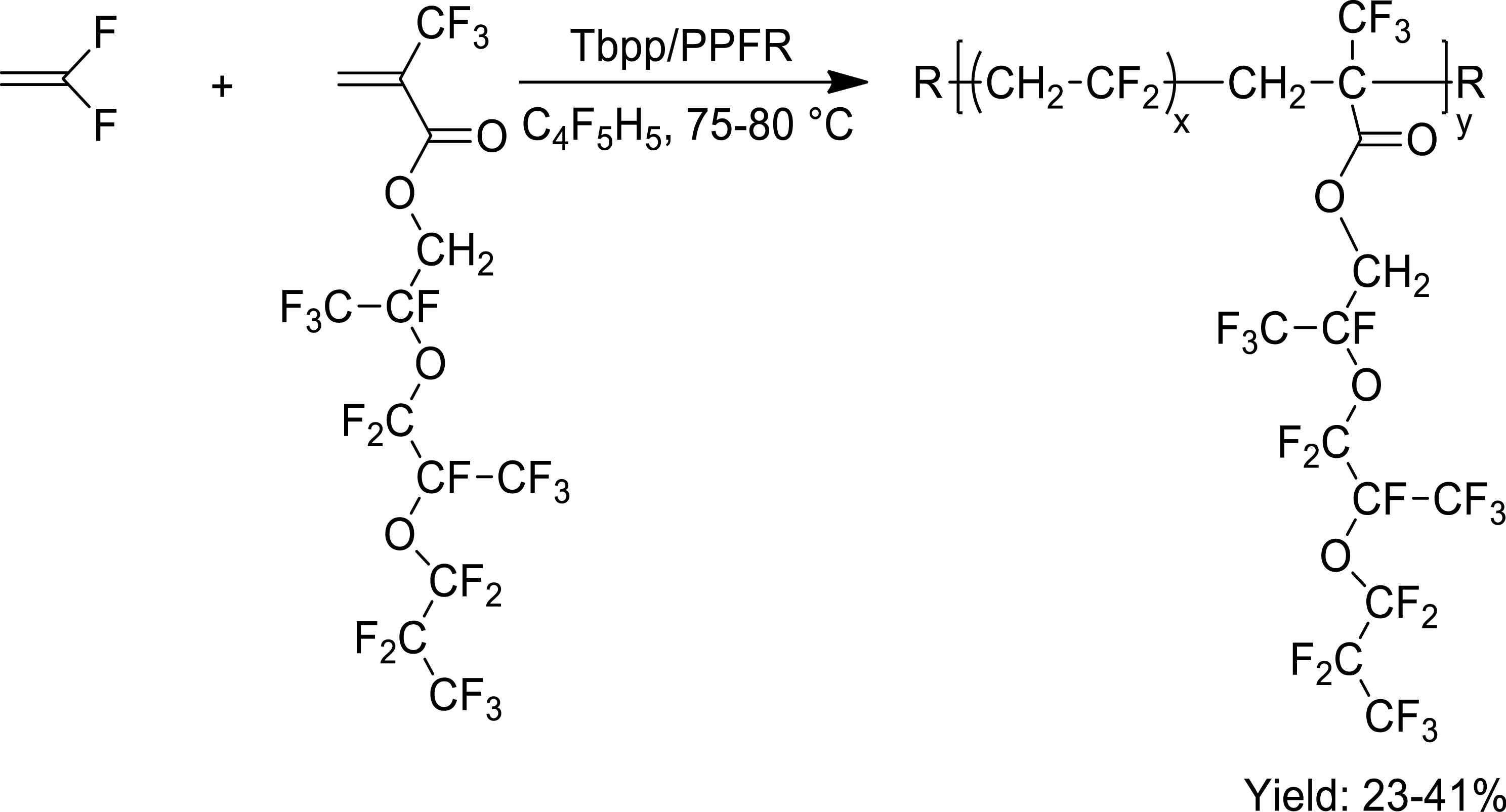

In addition, another MAF-func could be prepared by changing oligo(ethylene oxide) moiety with a polyfluoroether in an original comomoner able to copolymerize with VDF as novel solid polymer electrolyte (Scheme 14) [32].

Radical copolymerization of VDF with MAF derivative bearing polyfluoroethers [32].

Besides conventional radical copolymerization of VDF with MAF-func derivatives, the reversible deactivation radical copolymerization (RDRP) of MAF with VDF has also been studied, either via iodine transfer copolymerization in presence of 1-iodoperfluoroalkanes [33] or by RAFT in presence of linear [34] or cyclic [35] xanthates, the linear one acting as an emulsifier of polymer blend to obtain original membrane for fuel cell (PEMFC) [36]. Fuentes-Exposito et al. [37, 38] acheived surfactant-free PVDF latexes by RAFT-mediated emulsion polymerization of VDF in presence of commercially available poly(ethylene glycol) chains borne by a linear xanthate (PEG-Xa). The particle size was significantly smaller when the authors used PEG-Xa, evidencing the positive effect on particle stabilization of the involvement of xanthate chain end in the free radical process.

3.3. Radical terpolymerization of VDF with MAF and another fluorinated comonomer

3.3.1. Hexafluoropropylene (HFP) as a termonomer

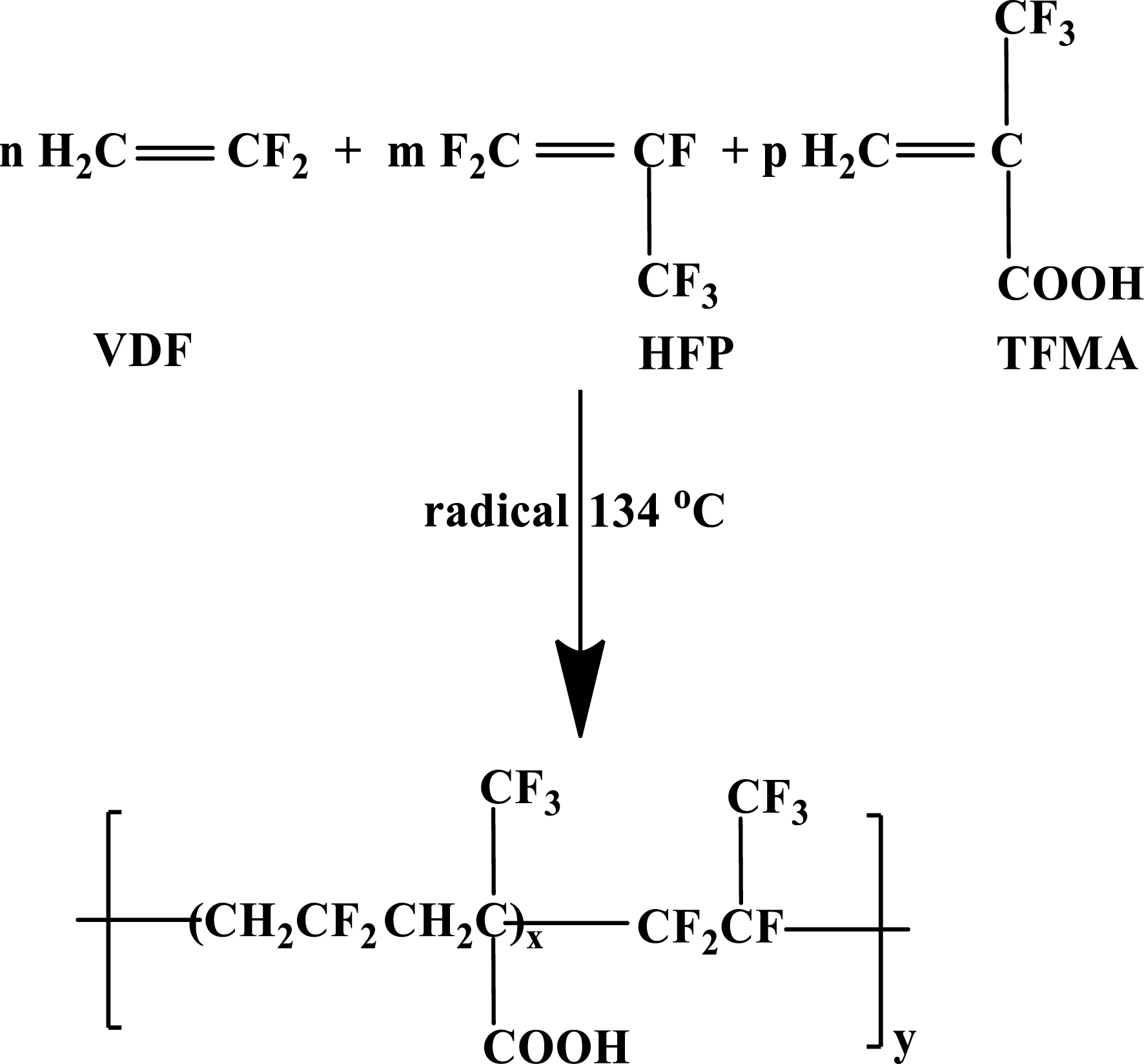

The insertion of MAF units into copolymers based on non-functional comonomers (as VDF, HFP, tetrafluoroethylene (TFE), chlorotrifluoroethylene (CTFE), etc) also brings a functional group that commercially available copolymers do not have (e.g., poly(VDF-co-HFP) as Kynar®, Viton® Daiel®, Solef® and Technoflon®, marketed by Arkema, Chemours, Daikin, Solvay and Syensqo, respectively) [39]. Scheme 15 illustrates how a simple radical terpolymerization [40] yields these copolymers bearing carboxylic side groups.

Radical terpolymerization of VDF with MAF and HFP [40].

3.3.2. Trifluoroethylene (TrFE) as a termonomer

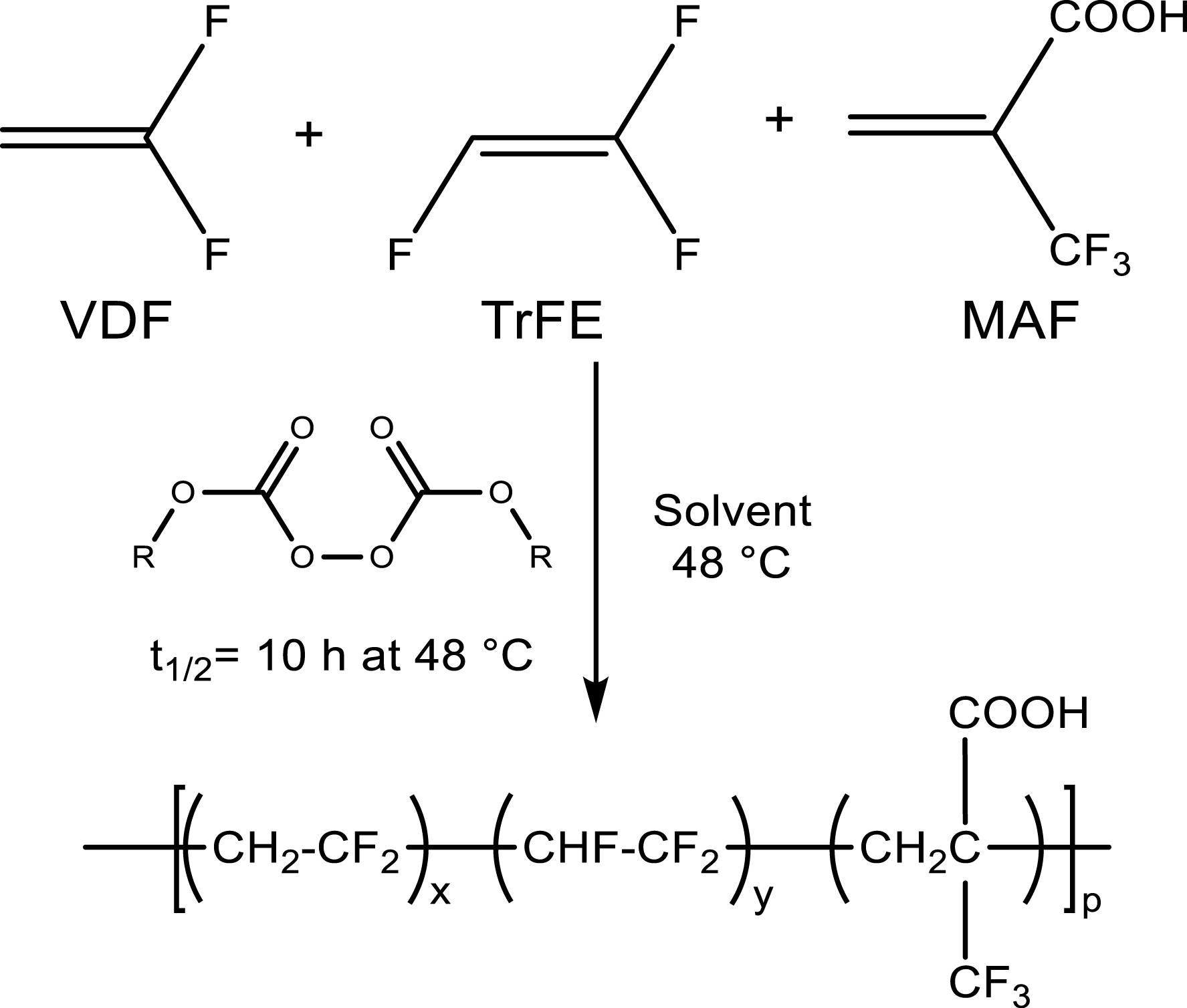

Copolymers based on VDF and trifluoroethylene (TrFE) display piezo- or ferroelectric properties [41, 42]. The use of 1% MAF (Scheme 16) enables satisfactory adhesion properties to stick golden electrodes on the poly(VDF-ter-TrFE-ter-MAF) terpolymer films for possible electroactive materials [43].

Conventional radical terpolymerization of VDF, trifluoroethylene (TrFE) and 2-trifluoromethacrylic acid (MAF) to obtain electroactive devices. In the peroxydicarbonate initiator, R stands for tert-butyl(cyclohexyl) [43].

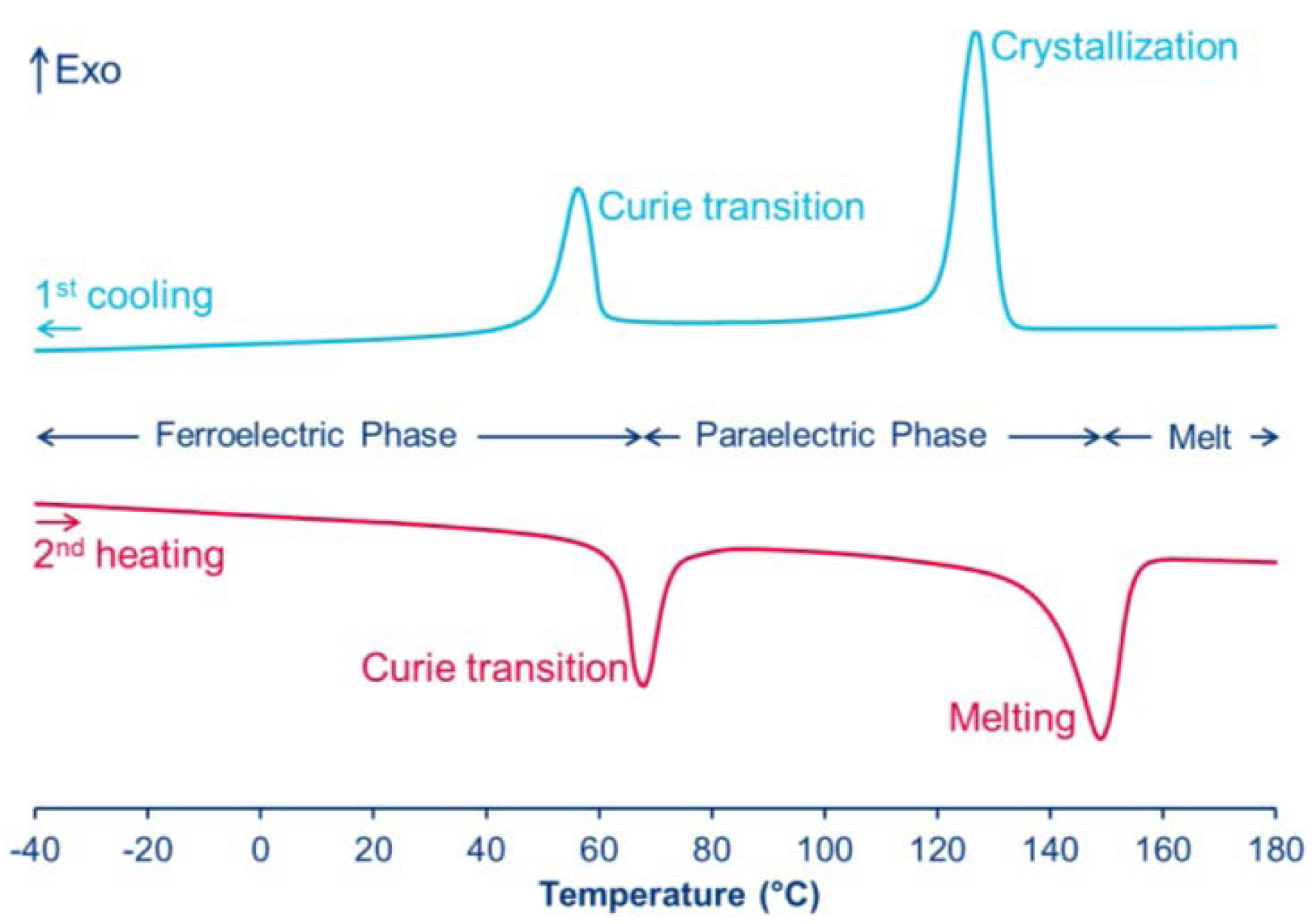

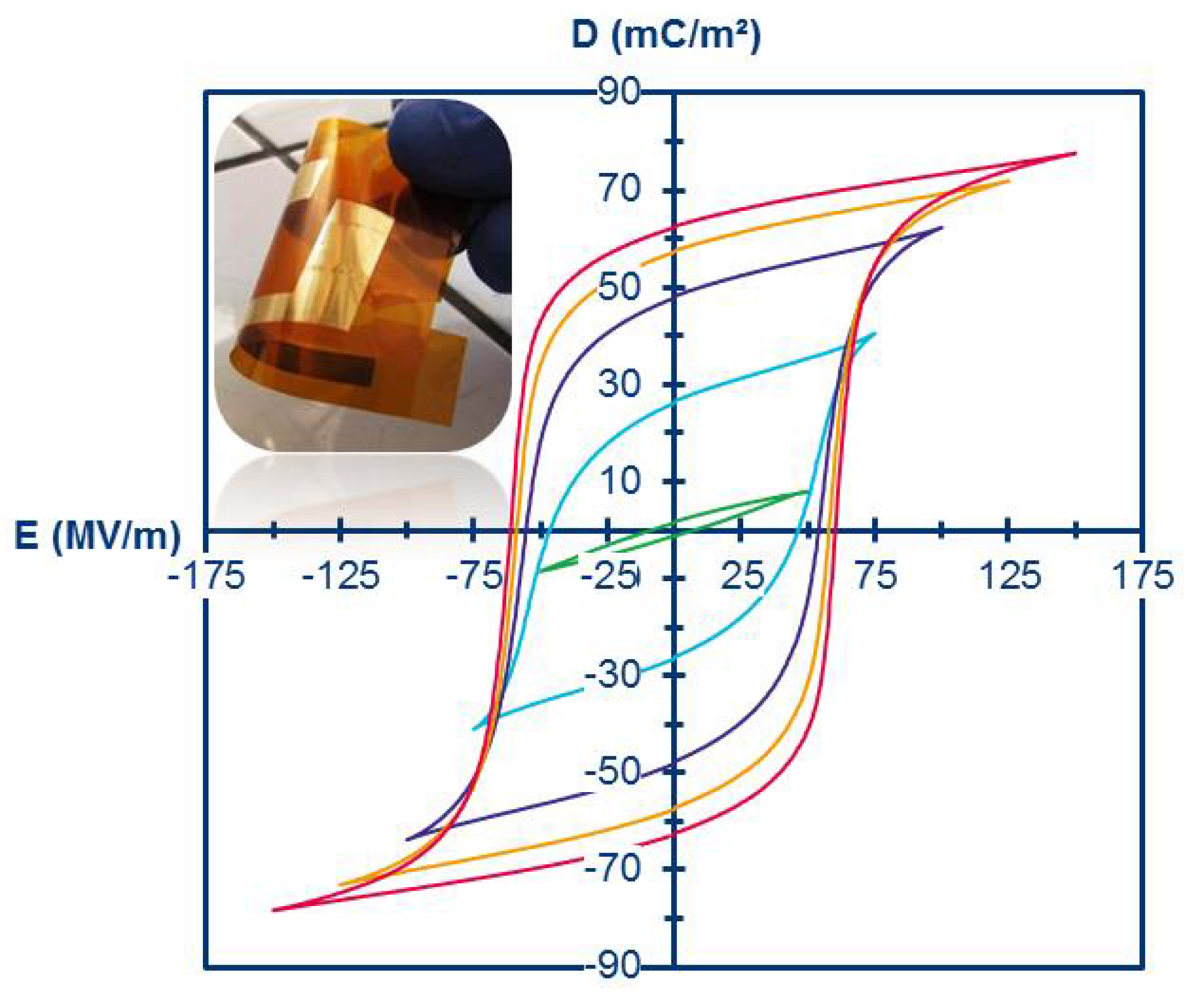

The resulting device displays some ferroelectric properties as evidenced by Figures 7 and 8. DSC thermogram of the resulting film exhibits Curie (Tc) and melting (Tm) temperatures (Figure 7), Tc being the temperature at which its spontaneous polarization undergoes an induced polarization and vice versa (i.e., the transition temperature at which a ferroelectric product becomes paraelectric material and vice-versa).

DSC thermograms of poly(VDF64-ter-TrFE35-ter-MAF1) terpolymer (reproduced with permission from RSC [41]).

Continuous D–E loops of a poly(VDF69-ter-TrFE31-ter-MAF1) terpolymer (inset is a photograph of the flexible gold electrode coated with a 20 μm thick film) (reproduced with permission from RSC [43]).

3.3.3. 2H-pentafluoropropylene (PFP) as a termonomer

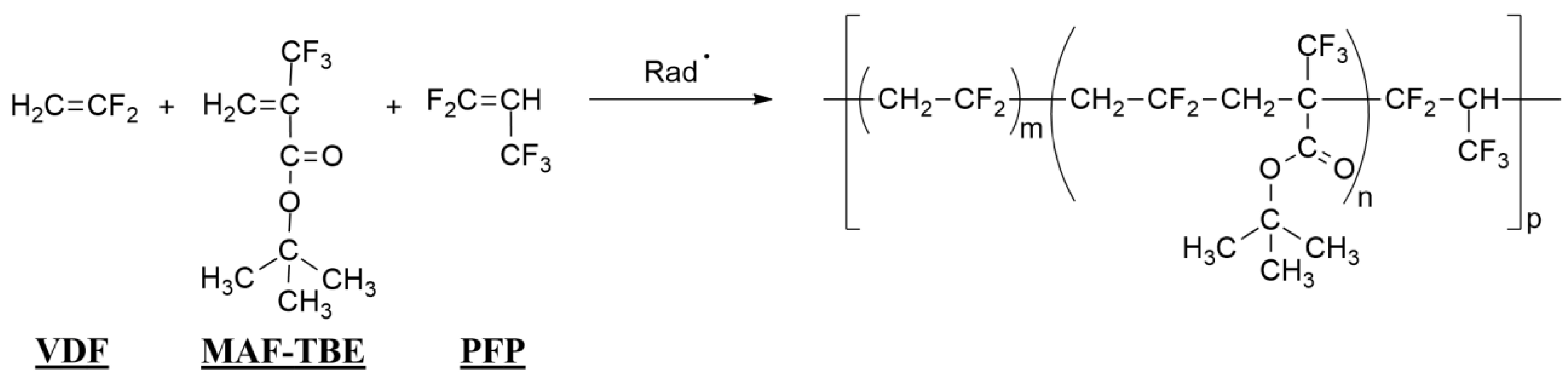

On another note, the terpolymerization of MAF-TBE with VDF and 2H-pentafluoropropylene (PFP) (Scheme 17) was reported with various monomer ratios, enabling PFP (that does not homopolymerize) to be reactive leading to poly(VDF-co-PFP) copolymers in low yields [44]. It was initiated by a mixture of two initiators (Trigonox® 101/ditert-butyl peroxide) in 1,1,1,3,3-pentafluoropropane as the solvent. The incorporation of PFP in the terpolymerization was favored by termonomer-induced copolymerization [45, 46].

Radical terpolymerization of 2H-pentafluoropropylene (PFP) with VDF and tert-butyl 2-trifluoromethyl acrylate (MAF-TBE) [44].

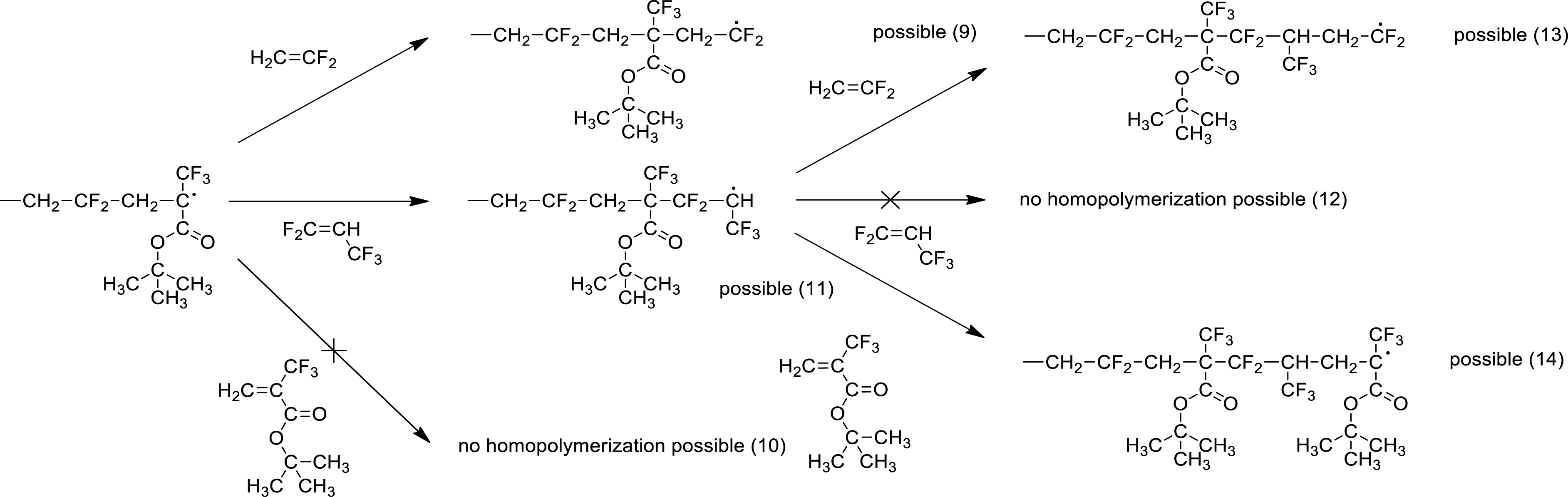

A mechanistic sketch of radical terpolymerization, based on the homopropagation of VDF and cross-propagation of PFP and HFP, is proposed (Scheme 18) that also takes into account the recombination step of macroradical (Scheme 19) [44].

Mechanism of the radical terpolymerization of PFP with VDF and MAF-TBE [44].

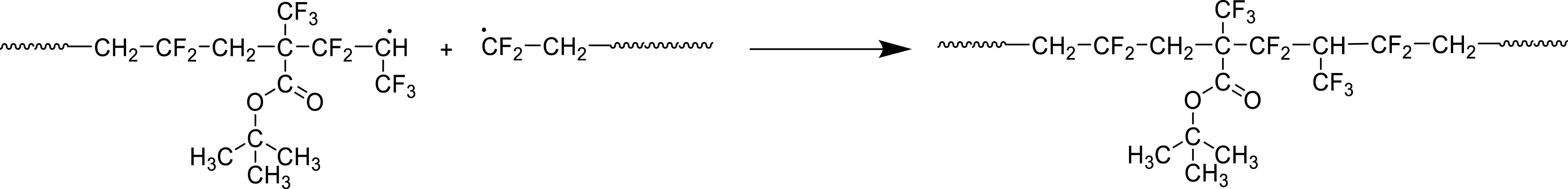

It is worth noting that the radical (co)polymerization of fluorinated monomers is usually terminated by recombination (and not disproportionation) [47]. Thus, the recombination of two growing macroradicals bearing PFP and VDF end-groups can be observed in Scheme 19.

Recombination of growing macroradicals based on PFP and VDF end-units [44].

3.4. Chemical modification of poly(VDF-co-MAF) copolymers

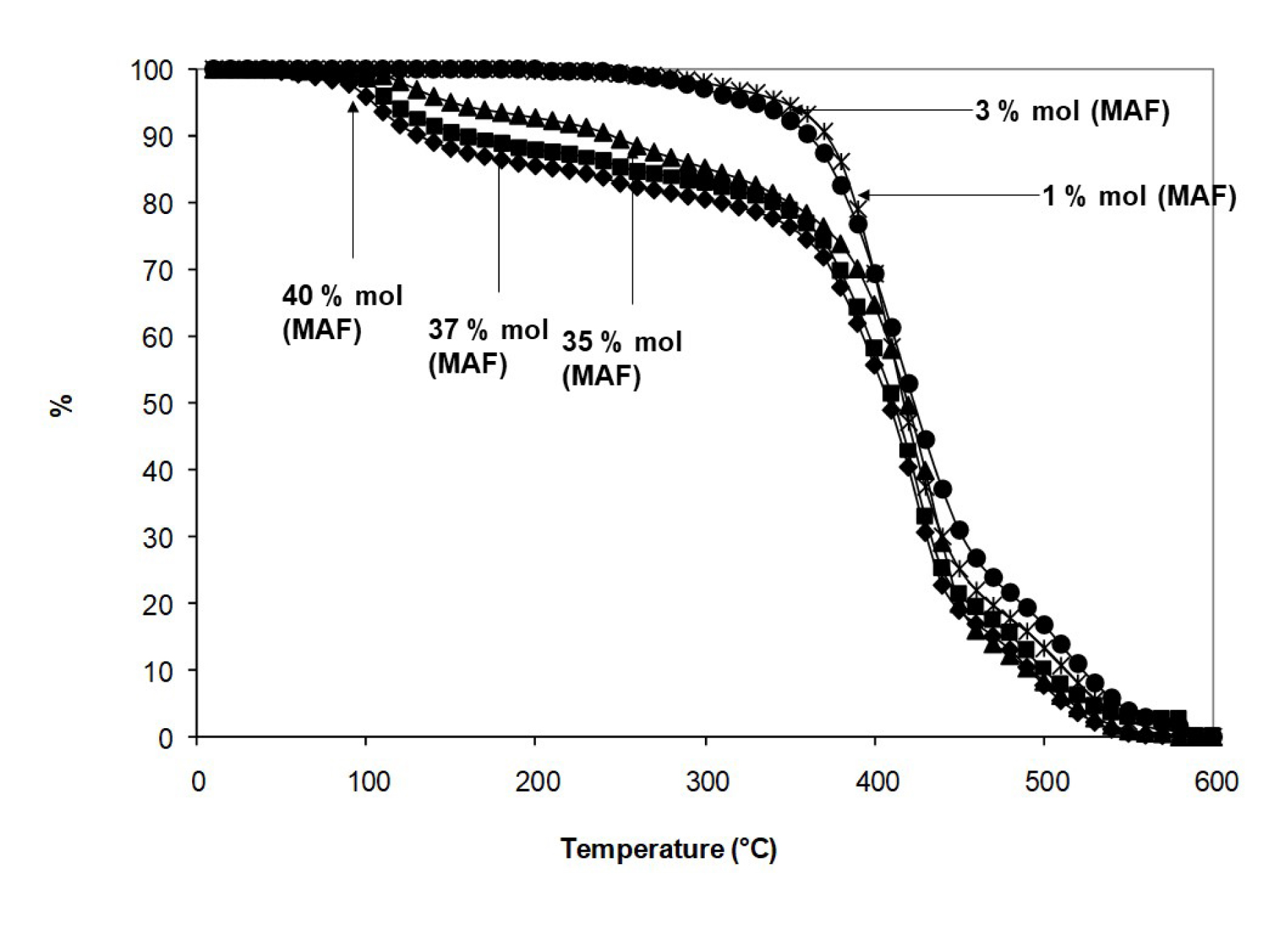

Thanks to the carboxylic acid side function, poly(VDF-co-MAF) copolymers may undergo some grafting or chemical modification. Actually, thermal stability of such copolymers is not as good as expected and the higher the MAF content [25, 26], the poorer the stability of these copolymers because of strong decarboxylation (Figure 9).

TGA thermograms of poly(VDF-co-MAF) at various MAF molar contents [25, 26].

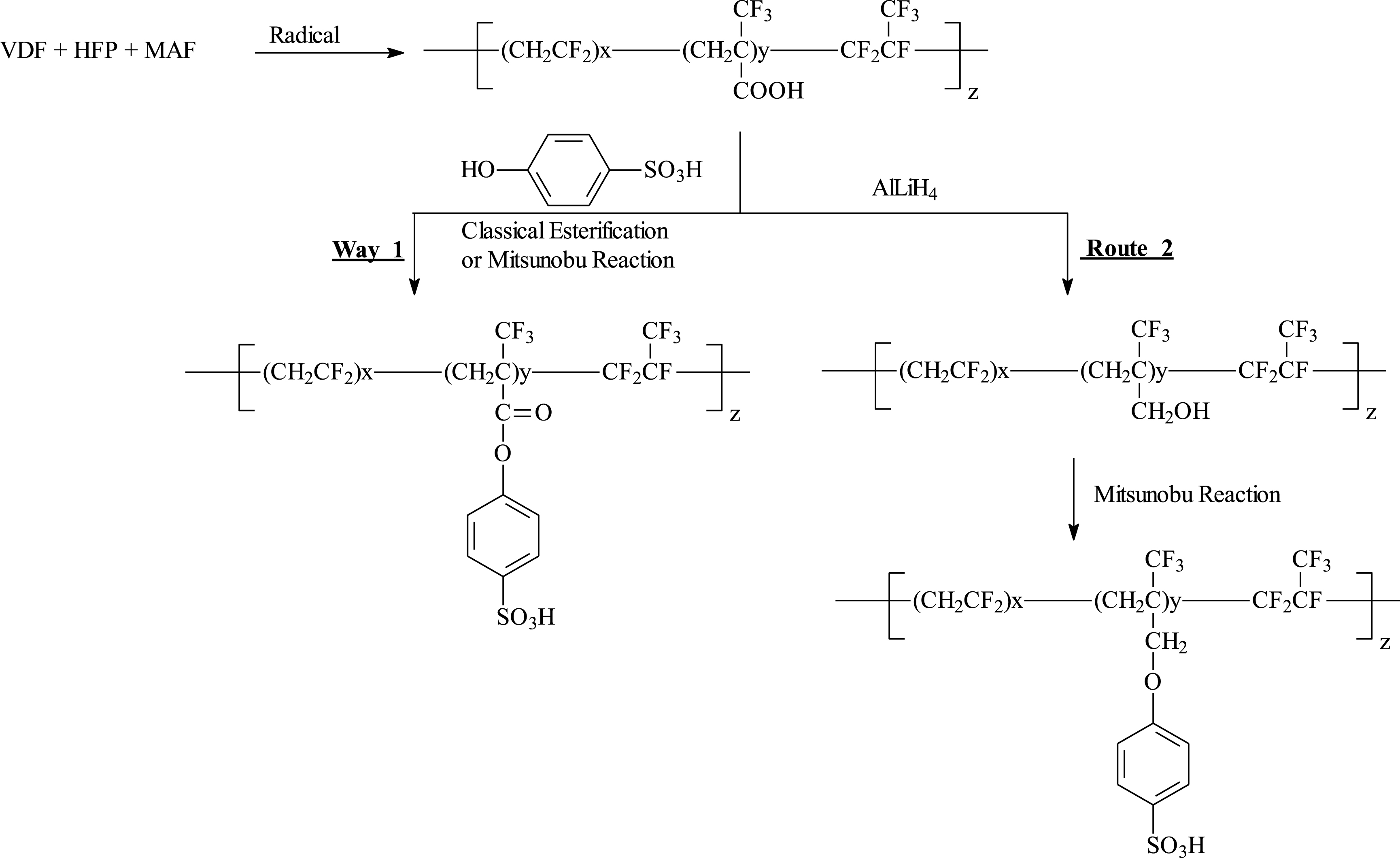

Thus, the reduction of such acid groups was reported, the resulting hydroxyl group undergoing a Mitsunobu reaction with para phenol sulfonic acid (route 2, Scheme 20), hence inserting strong acid as a possible example of fuel cell membranes [25, 26]. As expected, this etherification enhanced the thermal stability of the copolymer and could be straightforward compared to an esterification in medium yields (way 1, Scheme 20) and for which the ester link is poorly stable in acid media [25, 26].

Insertion of sulfonic acid function into poly(VDF-co-MAF) copolymers for possible fuel cell membranes (reproduced with permission from Amer. Chem. Soc. [25, 26]).

4. Issues on PFAS

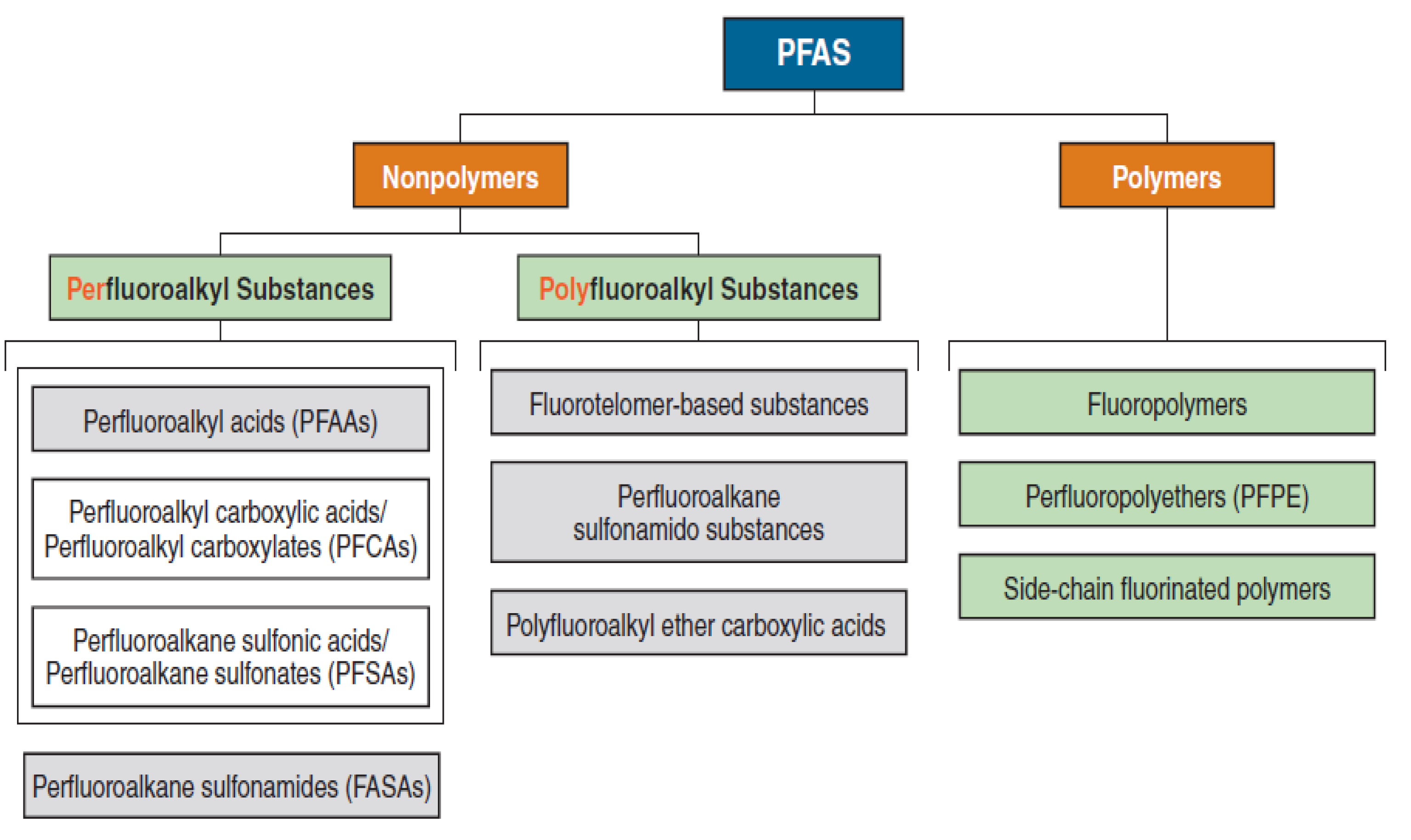

In recent years, per- or polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) have attracted significant attention [48, 49]. However, one must distinguish different categories linked to molar masses of PFAS (Figure 10) [48]. The lower ones are water soluble and are found in creeks, rivers and oceans, which are exposed to their toxicity, bioaccumulation and persistency [49].

Distinguishing families of per- or poly-fluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) into two domains (reproduced with permission from MDPI [48]).

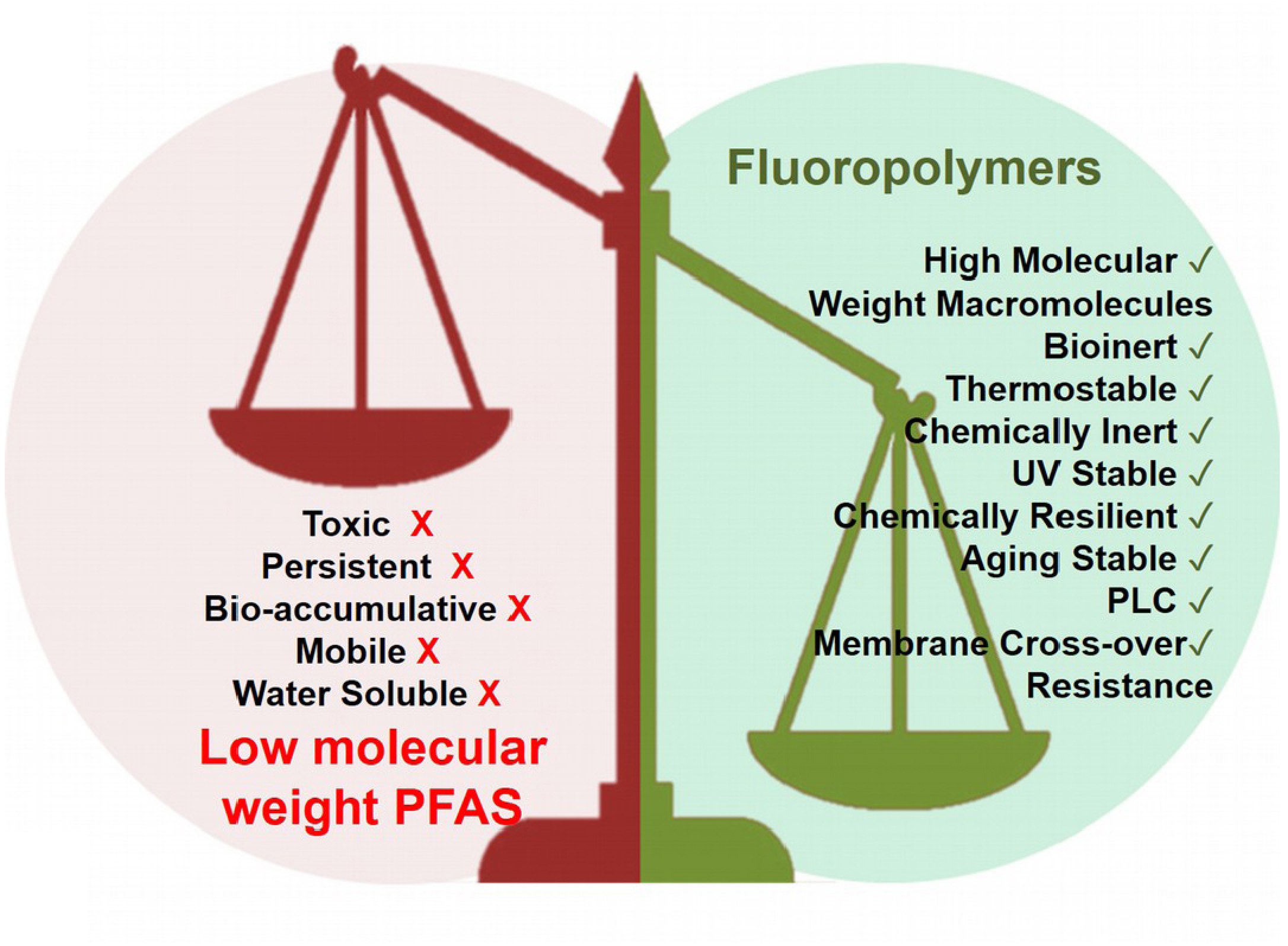

Except persistency (that can be also an advantage in resistance to aggressive media), these issues are not assigned to fluoropolymers (FPs) which are biocompatible and can be tolerated by human body [50, 51, 52]. In addition, FPs fulfill the 13 criteria of polymer of low concern (PLC), in terms of residual monomers, molar masses, dispersities, charges, etc. [53, 54] and really behave and contrast to low molar mass-compounds (Figure 11). However, 5 member states have pushed ECHA and the regulatory agencies to restrict them [55], though more than 5600 answers to the consultation were submitted [55].

The categorization of PFAS by their molar masses displays totally different advantages and issues (reproduced with permission from MDPI [48]).

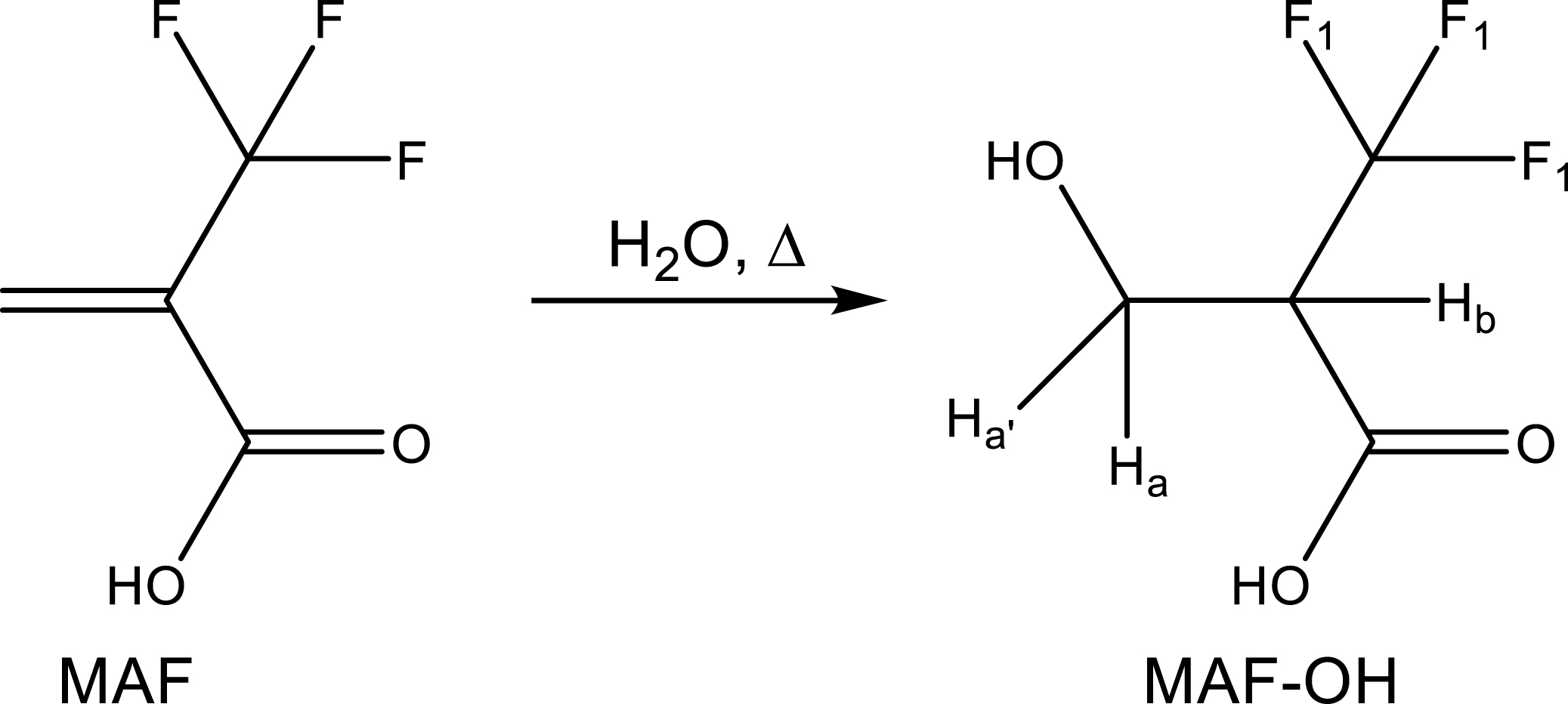

Searching alternatives to fluorosurfactants has been well-reported in the last few years [49, 56] and one strategy lies on the simple addition of water onto MAF (Scheme 21) [57]. This original and simple surfactant was successfully involved in emulsion homopolymerization of VDF [58] and copolymerization of VDF with PMVE [59].

Addition of water into MAF to yield a fluorinated short chain surfactant [57] in emulsion (co)polymerizations of VDF [58] and VDF and perfluoromethyl vinyl ether (PMVE) [59].

Though many strategies attempted recycling FPs [60], thermal unzipping [61, 62, 63, 64, 65], even achieved at the pilot scale at 3M/Dyneon Company on PTFE, FEP and PFA [66, 67], seems an appropriate option to recover TFE. The question lies on minimizing the released low molar mass compounds that led to hazardous issues.

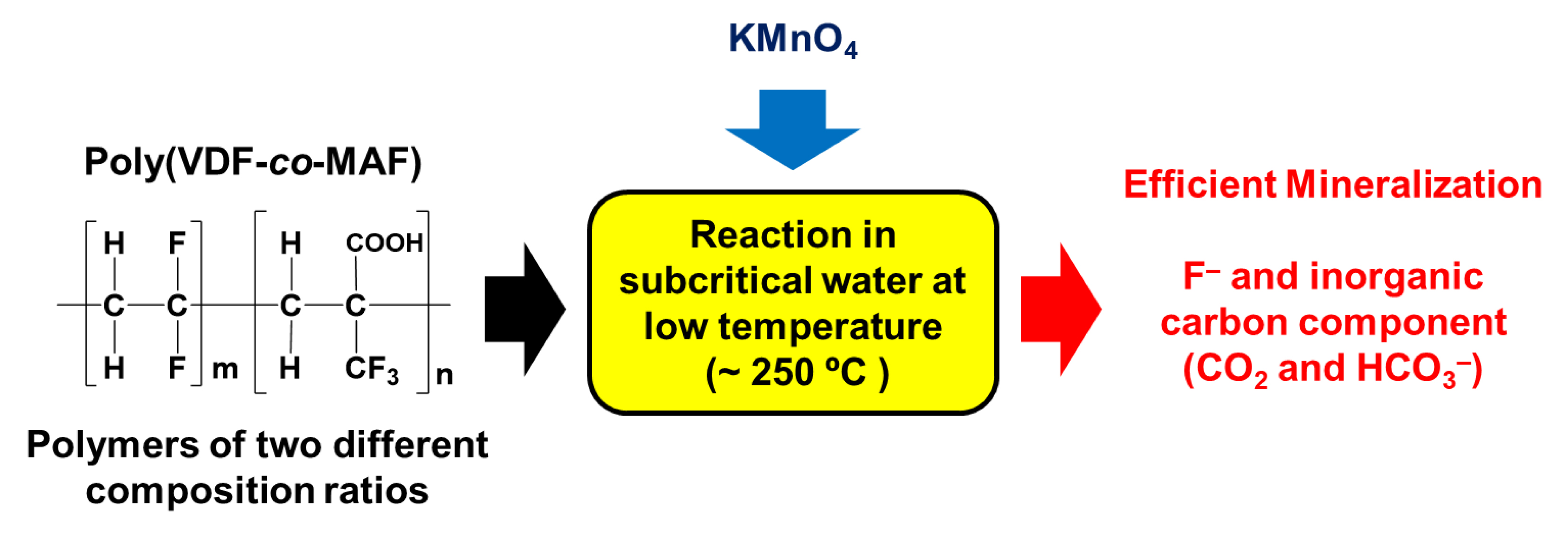

Finally, mineralizations of PVDF [68] and poly(VDF-co-MAF) copolymers [69] were recently studied in subcritical water (Figure 12) to generate fluoride anions, which in the presence of Ca(OH)2, leads to an original source of CaF2, thus closing the loop of the fluorine chemistry.

Mineralization of poly(VDF-co-MAF) copolymers in subcritical water (and oxidant in certain cases) (reproduced with permission from Amer. Chem. Soc. [68, 69]).

5. Conclusion

Fluoropolymers (FPs) are niche macromolecules with outstanding properties, designed by radical (co)polymerization. Their synthesis depends on the choice of the initiators, processes (not mentioned in this review), compared reactivity of the comonomers by the assessment of their reactivity ratios and the functional group that induces specific features for the searched applications of the targeted fluorinated copolymers. Polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) can be used in many areas as protective coatings, specific membranes for water purification, binders for cathodes in batteries, and electroactive (ferro- or piezoelectric) devices for haptics, actuators, organic transistors or sonars. Structures and reactivities of comonomers must also be considered in order to bring a specific property to the resulting materials. Among comonomers, MAF is a suitable partner for VDF and also opens up to a wide range of various reactive functional comonomers offering original VDF-containing copolymers for various applications (anticorrosion coatings, gel polymer electrolytes and possible binders for batteries, fuel cell membranes to name a few). The controlled radical (co)polymerization (or RDRP) of MAF with VDF has also been studied (ITP or RAFT polymerizations) leading to new architectures such as block, graft, gradient, alternated copolymers as original materials. Finally, related to recent severe pressure and regulations linked to PFAS issues, these fluorinated copolymers do not show any toxicity, bioaccumulation and crossing the cellular human membrane in addition to fulfilling the 13 PLC criteria. Hence, it can be anticipated that these macromolecules will exit from the PFAS family following scrutiny. Regarding recycling of VDF-containing copolymers, though several routes exist, one relevant strategy lies in their mineralization in subcritical water leading to fluoride anions as precursors of CaF2 as a starting point of fluorine chemistry as a circular economy process.

Declaration of interests

The authors do not work for, advise, own shares in, or receive funds from any organization that could benefit from this article, and have declared no affiliations other than their research organizations.

Funding

Arkema and French PEPR programme are acknowledged for financial supports.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all coauthors cited in the references below, as well as Tosoh FineChemical Corporation (Shunan, Japan) for supplying MAF monomer. BA thanks the French Fluorine Network (GIS).

CC-BY 4.0

CC-BY 4.0