1. Introduction

Colorectal cancer is the second most deadly cancer, accounting for 9.4% of the nearly 10 million worldwide cancer deaths in 2020 [1], and it remains a major public health problem. Surgery is generally the main option for treating colorectal cancer, often preceded and/or followed by chemotherapy or radiotherapy. These traditional therapies are often accompanied by myelosuppression, multidrug resistance, and numerous side effects linked to damages to healthy cells. Today photodynamic therapy (PDT) is a promising alternative treatment due to a series of advantages such as fewer side effects and toxicity, and PDT does not induce intrinsic or acquired resistance mechanisms [2]. This therapeutical approach requires the presence of molecular oxygen, the use of a photosensitizer (PS), and irradiation with light of appropriate wavelength. Upon irradiation, the PS is excited to a higher-energy state from which, by energy or electron transfer to ground state/air oxygen (3O2), it generates singlet oxygen (1O2) and other reactive oxygen species (ROS) which induce multiple damage to the tumor cell [3, 4]. Ideally, PSs should be characterized by a high 1O2 quantum yield and would not exhibit cytotoxicity in the dark; in addition, they must be able to absorb light in the near-infrared (NIR) spectral region since NIR light within the phototherapeutic window (𝜆 = 650–850 nm) can penetrate rather deeply into tissues. Another key point to avoid unwanted side effects is the preferential accumulation of PS in tumors [5, 6]. Thus, one approach to target solid tumors is to exploit the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect [7]. Over the past decade a large number of nanoparticle-based PS delivery systems have been developed [8, 9]. These nanocarriers include silica-[10], gold-[11], and natural polymer-based nanoparticles [12]. Polysaccharides have been widely explored for the design and development of nanocarriers due to their numerous advantages, including high water solubility, good biocompatibility, low toxicity, biodegradability and abundance of sources. We have recently reported the synthesis of nanoparticles consisting of covalently bonded porphyrins[13] or pheophorbide a to modified xylan [14]. These nanoparticles exhibited a dose-dependent phototoxicity only when irradiated with red light but their aggregation tendency, leading to a reduction in photodynamic efficiency, is a major drawback. To overcome this issue, nanoconjugates consisting of negatively charged cellulose nanocrystals (CNCs) and cationic β-cyclodextrin were developed to encapsulate protoporphyrin IX derivatives bearing an adamantane group [15]. The in vitro evaluation of this nanoparticle-based PS against HT-29 colorectal cancer cells showed a clear increase in efficacy compared with the free PS. This nanoplatform appears to be a very promising tool for the vectorization of PSs. Purpunin-18 (Pp-18) possesses a strong absorption band in the red region (702 nm in CHCl3), making it a potential PS for PDT, as red light penetrates deeply into animal tissues [16]. Unfortunately, direct use of Pp-18 as PS is limited, due to the presence of a cyclic anhydride, which readily opens after alkaline treatment or in biological media to form chlorin p6 with a hypsochromic shift of the Q absorption band around 662–665 nm [17, 18, 19]. In addition, the high hydrophobicity of Pp-18 leads to its aggregation at physiological pH and reduces its bioavaibility [20, 21]. To overcome these issues, it has been shown that it is possible to generate more stable PSs such as purpurinimides with a bathochromic red-shift and excellent in vitro and in vivo PDT efficacy [22, 23]. CNCs were obtained by sulfuric acid hydrolysis of microcrystalline cellulose, which removed amorphous regions and introduced negatively charged sulfate groups that cause electrostatic repulsion forces between suspended particles [24, 25]. These negative charges promote the addition, via electrostatic coupling, of positively charged β-CycloDextrin (β-CD+) previously functionalized with glycidyltrimethyl ammonium chloride (GTAC) [26].

In this work, to obtain a more stable purpurinimide PS than Pp-18 with red-shift light absorption, we transformed the Pp-18 anhydride ring into a cyclic imide to which an adamantyl group is attached. Indeed the adamantyl moiety, which is a spherical entity with a diameter of 6.5 Å, perfectly fits into the cavity diameter of β-CD (6.0–7.0 Å) [27]. Moreover, β-CD/adamantane complexes have found several important applications in supramolecular chemistry and biomedical applications due to their high stability [28]. In a second step, a complex between the newly synthesized PS and cellulose–cyclodextrin nanoparticles was formed. Finally, using PDT, the antiproliferative activity of this conjugate against HCT116 and HT-29 colorectal cancer cell lines was tested [27].

2. Results and discussion

2.1. Synthesis and characterization of the purpurinimide adamantane derivative (PIA)

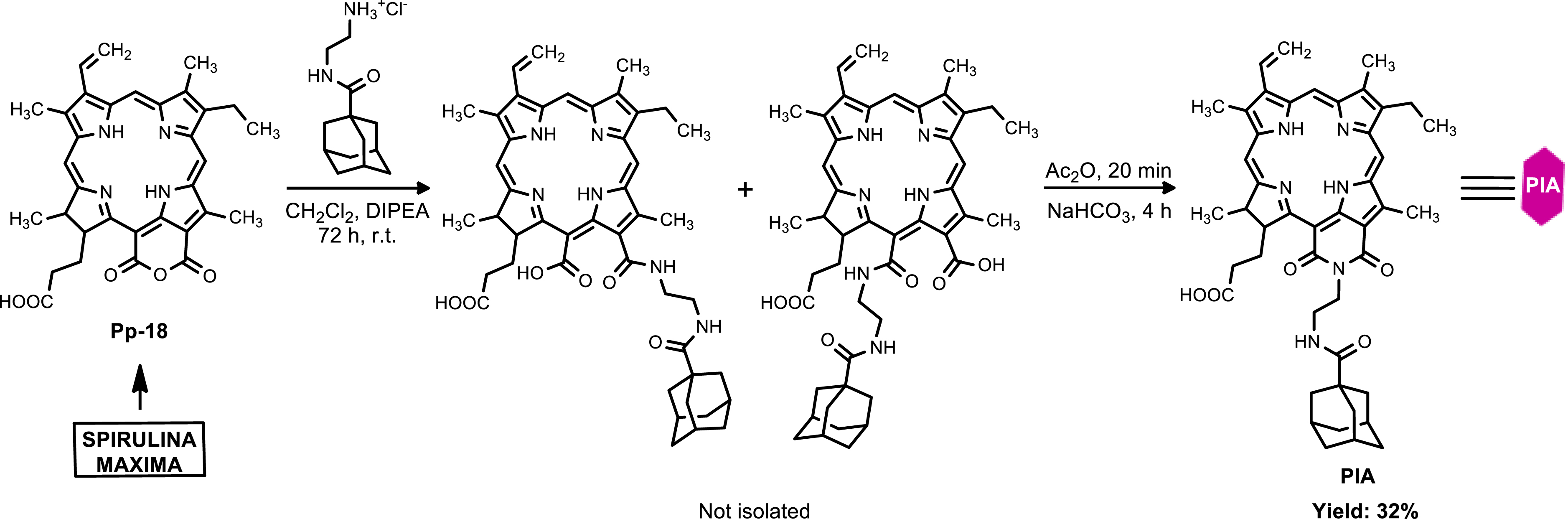

The hemisynthesis of Pp-18 from chlorophyll a was first performed following a previously reported procedure [29]. Pp-18 was reacted with N-(2-aminoethyl)adamantyl-1-carboxamide hydrochloride in the presence of diisopropylamine (DIPEA) to produce a mixture of two chlorin-p6 derivatives (not isolated) via the opening of the Pp-18 anhydride exocycle. After solvent evaporation and treatment of the crude reaction mixture with acetic anhydride, an intramolecular cyclization of the two chlorin p6 derivatives took place. After purification by preparative thin layer chromatography, the purpurinimide adamantane derivative (PIA) was obtained in 32% yield (Scheme 1). The chemical structure of PIA was established by IR, 1H, 13C NMR and HRMS (Figures S5–S10).

Synthesis of the purpurinimide adamantane derivative (PIA).

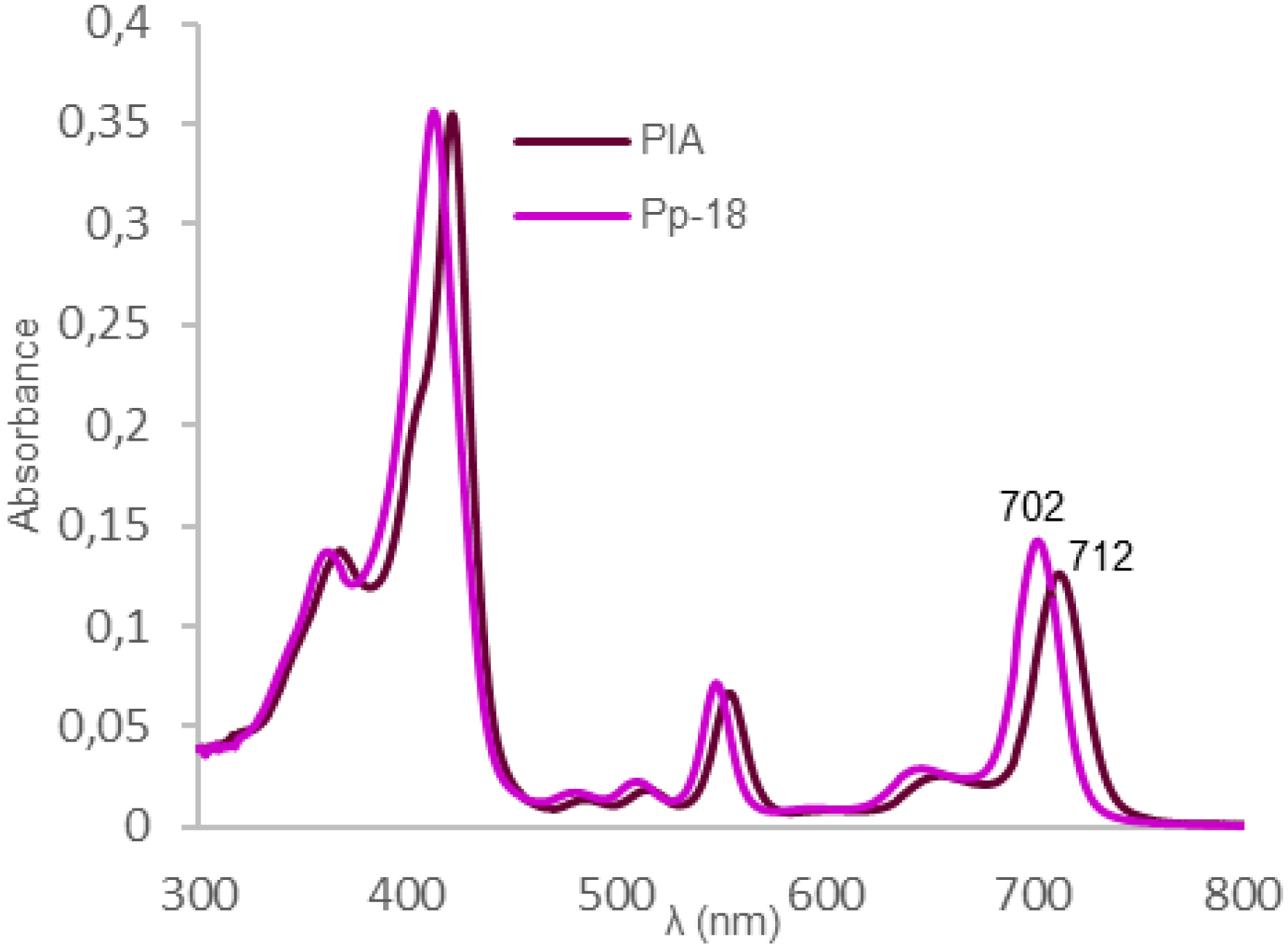

UV–Visible monitoring of the reaction showed that conversion of the anhydride of purpurin-18 to the cyclic imide of PIA was accompanied by a shift in the absorption maximum from 702 to 712 nm in CHCl3 (Figure 1).

UV–Visible absorption spectra of Pp-18 and PIA in CHCl3.

2.2. Synthesis and characterization of cellulose nanocrystals/cationic β-cyclodextrin/purpurinimide adamantane derivative (CNCs/β-CD+/PIA) complexes

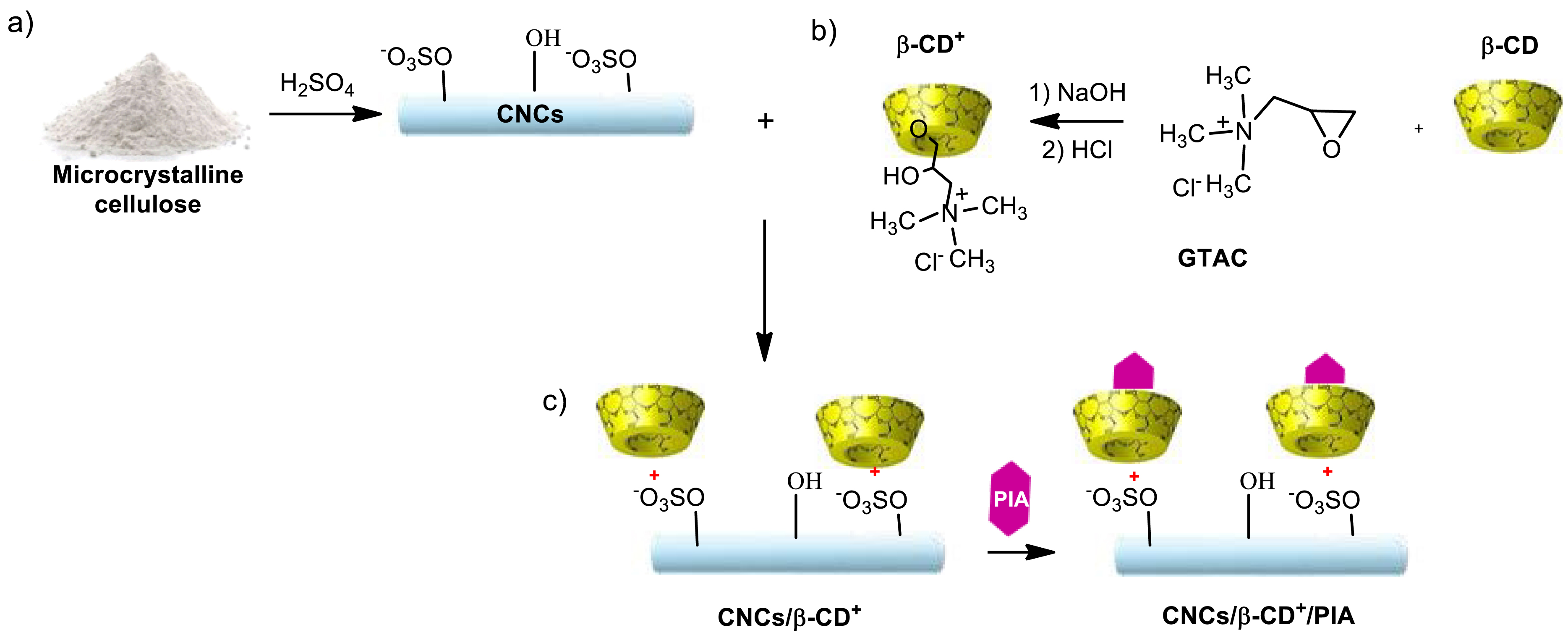

After sulfuric acid hydrolysis of microcrystalline cellulose, cellulose nanocrystals (CNCs) were obtained in 29% yield according to previously described methods (Scheme 2a) [24, 25]. The high zeta potential value of −51.8 ± 1.5 mV exhibited by CNCs (at 1.52/1000 w/w, Figure S1a) confirmed the presence of negatively charged sulfate groups on the surface of CNCs [24, 30]. This absolute value, higher than 30 mV, indicated a high degree of stability of the CNCs in aqueous suspension [31, 32]. FTIR spectra of CNCs showed peaks at 1205 cm−1 and 817 cm−1 that were assigned to sulfate esters groups on the CNCs surface, resulting from hydrolysis with sulfuric acid [33, 34] (Figure S10). In parallel, positive charges were introduced on β-cyclodextrin by functionalization with a large excess of glycidyltrimethylammonium chloride (GTAC) in alkaline aqueous medium (Scheme 2b) according to Chisholm and Wenzel [35]. Characterization of the final product is in agreement with the literature data (Figures S2 and S3) [26, 35]. Finally, mixing β-CD+ with CNCs resulted in the formation of CNCs/β-CD+ complexes via electrostatic interactions (Scheme 2) [26]. These complexes were then separated from free β-CD+ by centrifugation for 10 min at 13,000 rpm. To see how the characteristics have evolved after coupling, zeta potential measurements were conducted on CNCs/β-CD+ without dilution to determine their overall surface charge; their hydrodynamic size was measured on a 21-fold dilution (Table 1, Figure S1b). A significant increase in zeta potential from −51.8 ± 1.5 mV for CNCs to 29.77 ± 2.67 mV for CNCs/β-CD+ was observed (Table 1). The latter value, close to 30 mV, indicated that the dispersion was stable [32]. Analyzed by dynamic light scattering (DLS), this suspension showed an apparent hydrodynamic particle size of 438.97 ± 13 nm compared to 165.5 ± 2.1 nm for CNCs (Figure S1, Table 1). The FTIR spectrum of CNCs/β-CD+ differs from that of CNCs, with the appearance of a new peak at 1478 cm−1 attributed to the –N+–CH3 group of β-CD+, indicating the presence of β-CD+ on the CNCs surface (FTIR spectrum of CNCs/β-CD+/PIA, Figure S10). These data are a good indication that positively charged β-CD+ was successfully complexed with CNCs. PIA was loaded into the cavity of the complexed β-CD+ (Scheme 2c) thanks to the hydrophobic nature of the adamantane group. Briefly, a solution of PIA in acetone was mixed with aqueous CNCs/β-CD+ under ultrasound and magnetic stirring. At the end of the reaction, complexes were purified by centrifugation for 10 min at 10,000 rpm. A decrease in zeta potential from 29.77 ± 2.67 mV for CNCs/β-CD+ to 19.97 ± 0.15 for CNCs/β-CD+/PIA was observed (Table 1). This slight decrease could be explained by the carboxylate group of PIA. The new value around 20 mV indicated that the dispersion was relatively to moderately stable [32]. The successful inclusion of PIA in complexes was also confirmed by FT-IR spectroscopy (Figure S10) with peaks at 1724 cm−1, 1679 cm−1, 1641 cm−1, 1600 cm−1, due to, respectively, vibrations of C=O, C=O (amide bond), N–H (amide function), C=C. The concentration of PIA in CNCs/β-CD+ complexes was determined by UV–Vis spectroscopy around 3.65 × 10−4 mol/L.

Synthesis of CNCs/β-CD+/PIA complexes: (a) synthesis of CNCs, (b) synthesis of β-CD+, (c) inclusion of PIA into CNCs/β-CD+ complexes.

Size distribution, PDI and zeta potential (𝜁) of CNCs, CNCs/β-CD+ and CNCs/β-CD+/PIA

| CNCs | CNCs/β-CD+ | CNCs/β-CD+/PIA | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Size (nm) | 165.5 ± 2.1 | 438.97 ± 13 | - |

| PDI | 0.296 | 0.196 | - |

| 𝜁 (mV) | −51.8 ± 1.5 | 29.77 ± 2.67 | 19.97 ± 0.15 |

2.3. In vitro biological studies

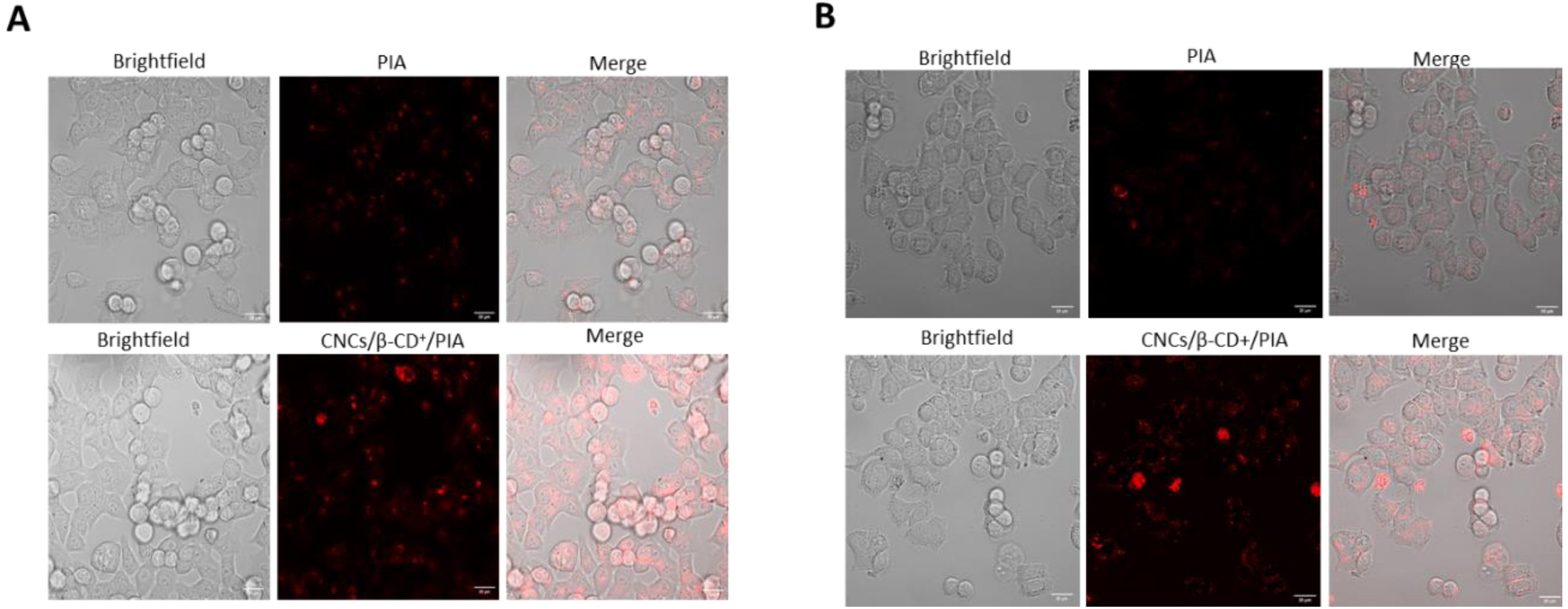

Uptake of PIA and CNCs/β-CD+/PIA complexes by HCT116 and HT-29 cells was studied by fluorescence confocal microscopy (Figure 2).

Cellular internalization of PIA and CNCs/β-CD+/PIA in human colorectal cancer cell lines HCT116 (A) and HT-29 (B). Cells were grown for 24 h in chamber slides coated with type I collagen and acetic acid. Cells were then treated with PS at IC50 values. After 24 h, the red fluorescence of PS was assessed by confocal microscopy. ImageJ software (version 1.52p) was used to determine colocalization. White scale bar = 20 μm.

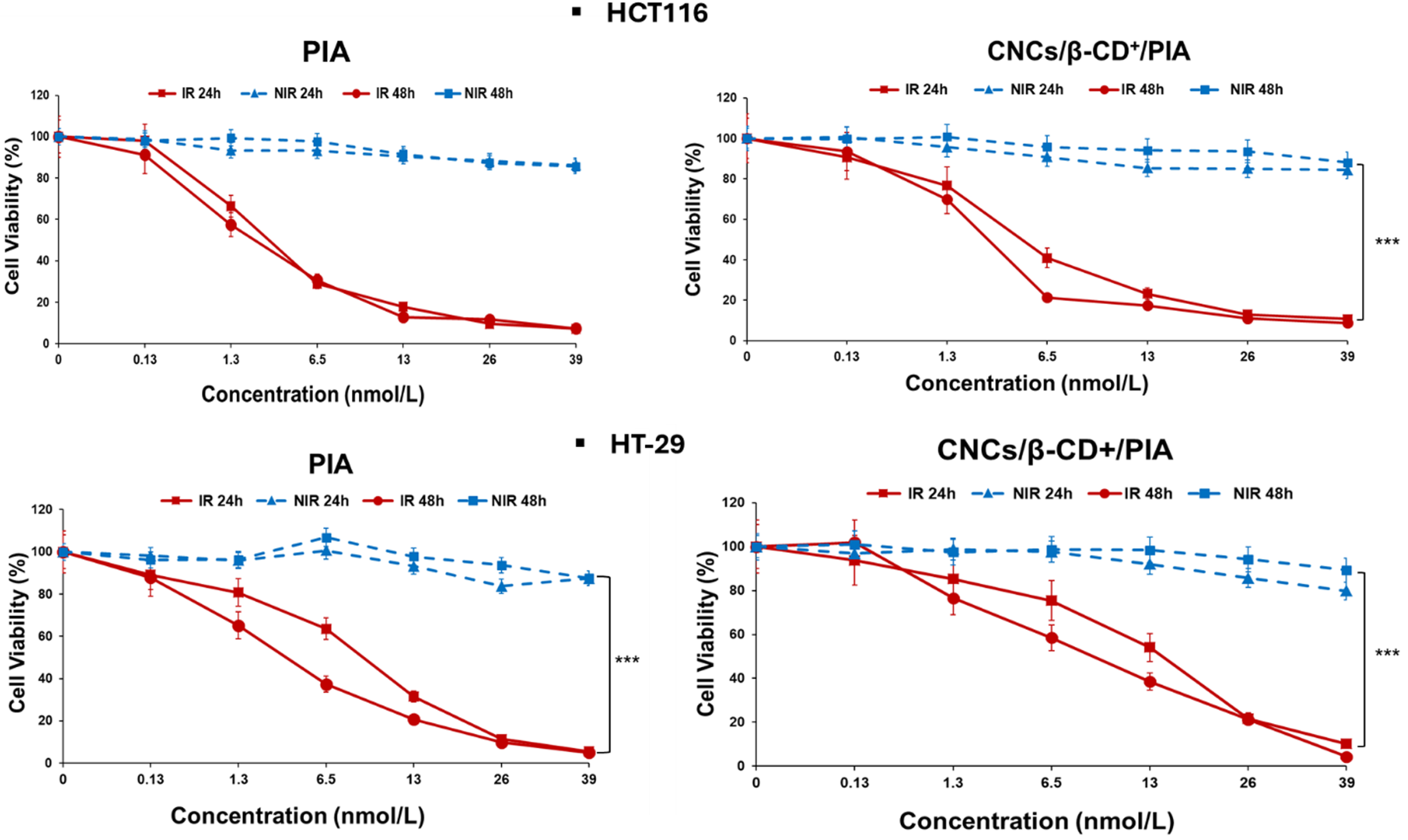

Cellular accumulation was observed after 24 h incubation with PIA and CNCs/β-CD+/PIA. Incubations in presence of CNCs/β-CD+/PIA led to an increased accumulation of PSs, regardless of the cell line. These results demonstrate the important role played by CNCs/β-CD+ in the cellular uptake of the PS and are in agreement with our previous results [26]. Photodynamic activities of PIA alone or CNCs/β-CD+/PIA complexes were evaluated in HCT116 and HT-29 colorectal cancer cell lines using MTT (3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5 diphenyl tetrazolium bromide) assays (Figure 3). The cancer cell lines were incubated with different concentrations of CNCs/β-CD+/PIA complexes as aqueous solution or PIA alone in DMSO at 0.13, 1.3, 6.5, 13, 26 and 39 nM for 24 h. Cells were then illuminated for 7 min at 650 nm (light dose 30 J/cm2) and then incubated in the dark for 24 and 48 h. Within the concentration range tested, we observed a low cytotoxicity in the dark. Under irradiation, the cytotoxicities of PIA alone or CNCs/β-CD+/PIA were much stronger in comparison with the control tests in the dark.

Cell viability in HCT116 and HT-29 colorectal cancer cells as an index of photocytotoxicity (IR) (light, total light dose 30 J/cm−2; irradiation 7 min, 𝜆 = 650 nm) and dark cytotoxicity (NIR) after 24 h incubation times of PIA alone or CNCs/β-CD+/PIA complexes at concentrations of 0.13 to 39 nM. The percentage of cell viability was determined by MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) assay, 24 and 48 h after irradiation. Error bars represent the standard deviation of three replicate experiments. (h𝜈 = irradiated and no h𝜈 = non irradiated). Data are represented as mean ± SEM (n = 3). ∗∗∗ p < 0.001 relative to the no h𝜈 at 48 h.

CNCs/β-CD+ complexes alone were shown to only slightly reduce cancer cell proliferation after 48 h [26]; therefore it can be concluded that the antiproliferative efficacy observed in these experiments, on the two cancer cell lines, is mainly due to the presence of PIA in the CNCs/β-CD+. In both cases, whether PIA is alone or complexed, the IC50 values after 48 h are only slightly lower than those obtained after 24 h (Table 2).

IC50 values of PIA and CNCs/β-CD+/PIA obtained using MTT assay

| Cell Line | HCT116 | P value (48 h relative to 24 h) | HT-29 | P value (48 h relative to 24 h) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incubation time after irradiation (h) | 24 h | 48 h | 24 h | 48 h | ||||||

| IC | IC | IC | IC | IC | IC | IC | IC | |||

| PIA | 2.6 | - | 2 | - | 0.3118 (NS) | 8.7 | - | 3.1 | - | 0.0458 (*) |

| CNCs/β-CD+/PIA | 4.3 | 22.9 | 2.5 | 13.3 | 0.0856 (NS) | 10 | 53.2 | 8.7 | 46.2 | 0.0565 (NS) |

| P value (PIA relative to CNCs/β-CD+/PIA) | 0.0306 (*) | - | 0.0876 (NS) | - | - | 0.0226 (*) | - | 0.0054 (**) | - | |

∗Data are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) of three experiments. The statistical significance of results was evaluated using GraphPad Prism 5.0 by a two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test, as ∗ p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. ∗ p < 0.05, ∗∗ p < 0.01 *NS: not significant.

a nmol PIA/L. b μg CNCs/β-CD+/PIA/mL.

As shown in Figure 3, a dose-dependent antiproliferative effect was observed in both colon cancer cell lines but HT-29 cells were more resistant than HCT116, as previously observed during in vitro assay using both cell lines [36, 37]. After 48 h photoirradiation, IC50 values of 2 and 3.1 nM were determined for HCT116 and HT-29, respectively. Encapsulation into CNCs/β-CD+ appeared to slightly decrease the toxicity of PIA. However, the IC50 values remained in the nanomolar range, with IC50 values of 2.5 and 8.7 nM against HCT116 and HT-29, respectively. The IC50 values for the CNCs/β-CD+/PIA complex of 13.3 and 46.2 μg/mL against HCT116 and HT-29, respectively, are relatively low in comparison with a biotoxicity value of 250 μg/mL reported in the literature [38]. Encapsulation of PIA in complexes proves to be a relevant choice to solubilize PIA in aqueous media and will facilitate its selective accumulation in the tumor tissues via enhanced permeation and retention (EPR) effect. In comparison with previous work, CNCs/β-CD+/PIA showed stronger photocytotoxicities than two different protoporphyrin IX (PpIX) adamantane derivatives also encapsulated into CNCs/β-CD+ (IC50 values of 1000 nM and 420 nM) [15]. PIA and its nanoformulation exhibited excellent PDT efficacies against cancer cell lines.

3. Conclusion

In this work, the synthesis of a new purpurin-18 imide derivative bearing an adamantane moiety and the preparation of biocompatible CNCs/β-CD+/PIA complexes for PDT anticancer therapy were described. 1H NMR, HRMS, UV–Visible and FTIR spectroscopies indicated that the purpurin-18 imide derivative and its inclusion complexes were successfully obtained. The biological tests demonstrated for the resulting complexes a very good solubility in aqueous media, an increased uptake of hydrophobic PS by cancer cells, and excellent photodynamic efficacy (IC50 = 2.5 and 8.7 nM against HCT116 and HT-29 cell lines respectively, 48 h after irradiation). Based on these results, we can suggest that PIA-loaded CNCs/β-CD+ is a promising tool for PDT anticancer therapy.

4. Materials and methods

4.1. Materials

For a list of materials, see Supplementary Information (SI).

4.2. Methods

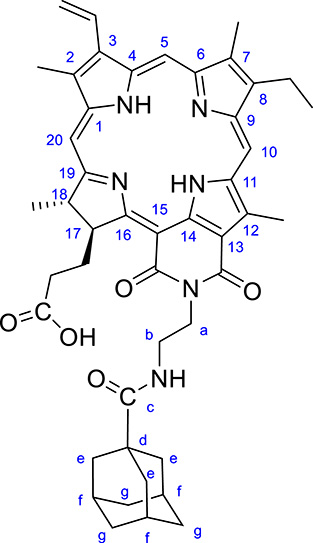

4.2.1. Synthesis of 131,151-N-(2-[(1-Adamantylcarbonyl)amino]ethylcycloimide) chlorin p6 (purpurinimide adamantane derivative or PIA) (Figure 4)

Purpurin-18 (90.8 mg, 0.1608 mmol, 1 equiv) and N-(2-aminoethyl)adamantyl-1-carboxamide hydrochloride (99.8 mg, 0.3856 mmol, 2.4 equiv) were dissolved in CH2Cl2 (10 mL) under argon atmosphere. DIPEA (100 μL, 0.5730 mmol, 3.6 equiv) was added and the resulting solution was stirred for 72 h at room temperature; the color of the solution changed from purple to green indicating the formation of the chlorin p6 derivative. CH2Cl2 was evaporated and the residue was dissolved in Ac2O (3 mL) and stirred for 20 min; the color changed from green to purple indicating the formation of the new imide cycle. The resulting mixture was diluted with 5% aqueous NaHCO3 (90 mL) and stirred for 4 h. The product was extracted with CH2Cl2, washed with deionized H2O, and dried over MgSO4. After evaporation, the purpurinimide was isolated by preparative thin layer chromatography using CHCl3/MeOH (95:5) as the eluent and crystallized from CH2Cl2/petroleum ether/cyclohexane, yielding 39.6 mg (32%).

Structure and numbering of PIA.

CCM Rf (CHCl3/MeOH 95:5) = 0.17. FTIR/ATR, 𝜈/cm−1: 3333, 2961, 2904, 2850, 1725, 1679, 1641, 1600, 1524. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): 𝛿H, ppm 9.54 (s, 1 H, H10), 9.31 (s, 1 H, H5), 8.55 (s, 1 H, H20), 7.87 (dd, 1 H, J = 17.0 and 11.9 Hz, H31-CH), 6.45 (bs, 1 H, NH), 6.28 (d, 1 H, J = 17.7 Hz, H32-CH2), 6.17 (d, 1 H, J = 11.4 Hz, H32-CH2), 5.69 (m, 1 H, H17), 4.84 (m, 1 H, a-CH2), 4.60 (m, 1 H, b-CH2), 4.48 (d, 1 H, J = 13.4 Hz, a-CH2), 4.32 (m, 1 H, H18), 3.76 (s, 3 H, 12-CH3), 3.59 (q, 2 H, J = 7.3 Hz, 81-CH2), 3.42 (d, 1 H, J = 13.1 Hz, b-CH2), 3.32 (s, 3 H, 2-CH3), 3.14 (s, 3 H, 7-CH3), 2.70 (m, 1 H, 171-CH2), 2.15-1.92 (m, 3 H, 171-CH2 and 172-CH2), 1.82 (d, 3 H, J = 8.0 Hz, 18-CH3), 1.73 (m, 3 H, f-Ad), 1.66 (t, 3 H, J = 7.5 Hz, 82-CH3), 1.53–1.38 (m, 12 H, e-Ad et g-Ad), 1.10 and −0.10 (s, 2 H, NH). 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): 𝛿C, ppm 179.8 (1C, Adamantane C=O), 176.5 (1C, C16), 175.8 (1C, C19), 170.4 (1C, COOH), 167.7 (1C, cycloimide C15’), 164.2 (1C, cycloimide C13’), 155.8 (1C, C6), 149.9 (1C, C9), 145.6 (1C, C8), 143.4 (1C, C1), 139.0 (1C, C12), 137.25 and 137.17 (2C, C3, C14), 136.42 and 136.4 (1C, C7 and C4), 131.5 (2C, C2, C11), 128.6 (1C, C31), 123.3 (1C, C32), 115.1 (1, C13), 107.0 (1C, C10), 102.6 (1C, C5), 97.9 (1C, C15), 94.9 (1C, C20), 53.5 (1C, C17), 50.3 (1C, C18), 40.5 (1C, C-Add),38.64 (3C, CH2-Ad), 38.56 (1C, NCH2CH2NH), 38.2 (1C, NCH2CH2NH), 36.2 (3C, CH2-Ad), 32.2 (1C, C172-CH2), 31.4 (1C, C171-CH2), 27.8 (3C, CH-Adf), 23.7 (1C, 18-CH3), 19.4 (1C, 8-CH2), 17.4 (1C, 8-CH3), 12.4 (1C, 12-CH3), 11.9 (1C, 2-CH3), 11.1 (1C, 7-CH3). HRMS m/z: [M + H]+ calc for C46H53N6O5 769.4072; found 769.4080. UV-Visible in DMSO, 𝜆max/nm (𝜖, 10−3 L⋅mol−1⋅cm−1): 420 (78), 512 (6.4), 550 (14), 648 (5), 705 (28). UV-Visible in CHCl3, 𝜆max/nm (𝜖, 10−3 L⋅mol−1⋅cm−1): 421 (120), 515 (6), 554 (23), 656 (8), 712 (44).

4.2.2. Production of cellulose nanocrystals (CNCs)

Microcrystalline cellulose (MCC) was used as starting material to obtain CNCs according to previously reported methods [24, 25]. Briefly, MCC (2 g) was mixed with H2SO4 (40 mL of 61 wt%) using a magnetic stirrer at 45 °C for 1.5 h. The suspension was diluted with cold distilled water (150 mL, 4 °C) to stop the reaction. Then, CNCs were pelleted by centrifugation for 10 min at 3700 rpm and the supernatant was discarded. The pellets were resuspended in H2O to eliminate excess acid and impurities and then centrifuged for 10 min at 3700 rpm. The supernatant was discarded. The pellets were resuspended in H2O and centrifuged for 10 min at 3700 rpm. The supernatant containing the CNCs was dialyzed against distilled H2O using membrane tubing (6–8 KDa cutoff) for 5–6 days. Dialysis H2O was changed two or three times each day. After dialysis, the resulting solution was completely dispersed by ultrasonic treatment in an ice bath using a Elmasonic S15 for 15 min to give the desired colloidal suspension. After freeze-drying, the yield was determined as 29% using Equation (1). Hydrodynamic size, polydispersity index, and zeta potential measurements were carried out with a 0.152 wt% suspension.

FTIR/ATR 𝜈/cm−1: 3337, 2900, 1650, 1425, 1369, 1333, 1317, 1281, 1205, 1161, 1111, 1033, 1057, 898, 817 and 776.

The CNCs yield (%) was calculated according to Equation (1):

| (1) |

4.2.3. Cationic β-cyclodextrin (β-CD+) synthesis

Cationic β-cyclodextrin was prepared by reacting the native β-cyclodextrin (β-CD) with glycidyltrimethylammonium chloride (GTAC) [35]. Distilled water (20 mL) and β-CD (3.008 g, 2.65 mmol, 1 equiv) were introduced in a round-bottomed flask (100 mL). The pH was adjusted to 12 with NaOH (2M). Then GTAC (14.5 mL, 108 mmol, 40.8 equiv) was added to the mixture. The reaction mixture was stirred at 50 °C for 5 days. The pH was adjusted to 6 with the addition of HCl (2M) and stirring for 30 min at rt. The reaction mixture was dialyzed against distilled water in a dialysis tubing (MWCO Molecular weight cutoff: 500 Da) for 27 h, distilled H2O was replaced once. After dialysis, the volume of the colorless liquid was brought up to 250 mL with distilled H2O. Aliquots of this solution were lyophilized and characterized. Degree of substitution (DS) = 2 was determined by integrating the appropriate signals of the 1H NMR spectrum.

FTIR/ATR (cm−1): 3345, 2929, 1638, 1478, 1418, 1353, 1148, 1108 and 1024. 1H NMR (500 MHz, D2O): 𝛿 (ppm) = 5.33 (d, 1 H, J = 5.75 Hz), 4.48 (m, 2 H), 4.35–4.26 (m, 1 H), 4.08-3.81 (m, 6 H), 3.78–3.69 (m, 2 H), 3.64 (m, 4 H), 3.6–3.42 (m, 6 H), 3.38-3.33 (m, 2 H) and 3.27 (s, 18 H).

4.2.4. Preparation of CNCs/β-CD+

The CNCs/β-CD+ complex was prepared as previously described with slight modification [26]. β-CD+ (40 mL, 1.42 mg/mL) was added slowly to CNCs (11 mL, 1.42 mg/mL) under ultrasound in an ice bath for 15 min and stirred overnight at rt. The mixture was then centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 10 min to eliminate free β-CD+. The precipitate was dispersed in distilled H2O (20 mL). The final solution was used to encapsulate PIA.

4.2.5. Preparation of purpurinimide-loaded cellulose nanocrystals/cationic-β-cyclodextrin (CNCs/β-CD+/PIA)

PIA (5 mg) was dissolved in acetone (800 μL) and introduced into aqueous CNCs/β-CD+ suspension (11 mL) under ultrasound in an ice bath for 5 min. The solution was then protected from light and stirred for 1.25 h in an ice bath. The complex was centrifuged at 10 000 rpm for 10 min to eliminate free PIA remaining in the supernatant. The pellet was redispersed in distilled H2O (11 mL) to form the final suspension of inclusion complex. Aliquots (0.5 mL) of this final suspension were lyophilized and then solubilized in DMSO to determine the loading amount of PIA in CNCs/β-CD+/PIA, by measurement of absorbance at 420 nm. PIA concentration in CNCs/β-CD+/PIA complex was 3.65 × 10−4 mol/L. To determine the overall surface charge of CNCs/β-CD+/PIA inclusion complex, the zeta potential of the sample was measured without dilution.

FTIR/ATR (cm−1): 3338, 2969, 2904, 2852, 1724, 1679, 1641, 1600, 1526, 1479, 1455, 1426, 1369, 1136, 1315, 1281, 1248, 1205, 1161, 1110, 1056, 1032, 900, 881 and 791.

4.2.6. In vitro photoirradiation Studies

The two human colorectal cancer cell lines used, HT-29 and HCT116, were provided by the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC-LGC Standards, Mosheim, France). Both cell lines were cultured in RPMI medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), L-glutamine (1%), penicillin (100 U/mL), and streptomycin (100 μg/mL) (all reagents purchased from Gibco BRL, Cergy-Pontoise, France). Cells were cultured in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 at 37 °C. For all experiments, HCT116 cells were seeded at 1.2 × 104, and HT-29 cells at 2.1 × 104 cells/cm2.

The PDT protocol was performed as follows: 4 × 103 and 7 × 103 cells/well for HCT116 and HT-29, respectively, were seeded into 96-well plates. Cells were grown for 24 h before exposure or not to 0.13, 1.3, 6.5, 13, 26 and 39 nM of PIA in DMSO or CNCs/β-CD+/PIA (aqueous suspension). After 24 h, a red phenol-free medium was added before irradiation or not at 650 nm (30 J/cm2–7 min) delivered from the light source PDT TP-1 (Cosmedico Medizintechnik GmbH, Schwenningen, Germany). After irradiation, the cells were incubated at 37 °C for 24 and 48 h for further analysis.

Cancer cell viability was assessed by MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) method (from Sigma-Aldrich, Saint-Quentin-Fallavier, France). MTT (5 g/L) was added 24 and 48 h after irradiation. After 3 h of incubation, DMSO (100 μL) was added to each well to dissolve the formazan crystals, and absorbance was recorded at 550 nm using a microplate reader (Thermoscientific MULTISKAN FC). The absorbance A values ± standard deviation was the mean of three experiments. The percent of viability was calculated using Equation (2):

| (2) |

4.2.7. Cellular internalization by confocal microscopy

To confirm the cellular uptake, HCT116 and HT-29 cells were seeded for 24 h before treatment with PIA or CNCs/β-CD+/PIA complexes at IC50 concentrations in chamber slides (ibidi μ-Slide 8 well from Clinisciences, Martinsried, Germany) coated with a type I collagen (3 mg/mL) and with acetic acid (20 mM) gel. Photos were taken using a confocal microscope (laser Zeiss LSM 510 Meta—×1000). Colocalization was assessed using the ImageJ software (version 1.52p).

Declaration of interests

The authors do not work for, advise, own shares in, or receive funds from any organization that could benefit from this article, and have declared no affiliations other than their research organizations.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge logistical and financial support from Campus France, “Agence Nationale des Bourses du Gabon”, “Ligue Nationale contre le Cancer (CD 87 and CD 23)” and “Conseil Régional de Nouvelle Aquitaine”. They wish to thank Dr. Cyril Colas (ICOA-Univ. Orléans) for ESI-HRMS analyses and Dr. Yves Champavier from BISCEm platform for NMR analysis. They are indebted to Dr. Michel Guilloton for his help in manuscript editing.

CC-BY 4.0

CC-BY 4.0