1. Introduction

Lignocellulosic biomass (LCB), the main component of the plant cell wall, is obtained from plant biomass like wood, herbaceous plants, coproducts and wastes from agro-industries. LCB appears to be the best promising alternative to fossil carbon due to its sustainability and abundance on Earth. Lignocellulosic biomass is rich in cellulose, a polymer composed of linear glucose chains; hemicelluloses, branched heteropolymers composed of hexoses and pentoses; and lignin, an amorphous polymer composed of three structural units, H (p-hydroxyphenyl), G (guaiacyl), and S (syringyl), resulting from the condensation of three phenylpropane monomers: coumaryl, coniferyl, and sinapyl alcohols [1]. The composition and amounts of polysaccharides and lignins greatly vary between different plant species, yielding heterogeneous structures of the LCB. Until now, polysaccharides have been the main fraction of interest in biomass biorefinery processes while lignin valorization needs further research efforts. Specific and selective fractionation of LCB, including lignin and derivatives, would enable these compounds to be used in a rational and sustainable way. Enzymatic fractionation makes it possible, by catalyzing specific bond cleavage under mild and low-energy reaction conditions. In Nature, the enzymatic depolymerization of LCB is efficiently carried out by bacteria, white- and brown-rot fungi that decompose wood [2, 3, 4].

However, to date, no biotechnological system has been shown to be sufficiently efficient to allow their use at industrial scale. The low efficiency and stability of the biocatalysts used is the main limitation of lignin valorization. Thus, the identification of efficient and stable ligninolytic enzymes still presents a technological challenge. Ligninolytic enzymes are oxidoreductases and include mainly laccases, peroxidases (versatile peroxidases (VP), dye decolorizing peroxidases (DyP), lignin peroxidases (LiP) and manganese peroxidases (MnP)) [5, 6, 7]. Furthermore, the enzymatic fractionation and upgrade of LCB and lignins is improved by the action of auxiliary enzymes operating in synergy with the cellulolytic, hemicellulolytic and ligninolytic enzymes. Among them, oxidases generate hydrogen peroxide, oxygenases convert dioxygen or hydrogen peroxide into water, and reductases as well as dehydrogenases reduce radicals.

Oxidoreductases involved in lignin degradation are usually identified and characterized by methods based on the light absorption properties of lignin-like monomers like guaiacol, pyrogallol, sinapic acid, synthetic dimers models like guaiacyl glycerol-β-guaiacyl ether (GGE), veratryl glycerol-β-guaiacyl ether (VGE) or other synthetic redox substrates like syringaldazine or azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS) [3, 8, 9, 10, 11]. These methods require clear and uniform media to perform accurate enzyme activity measurements. As a result, the activities monitored by these methods do not account for the enzyme interactions with water-insoluble lignin polymers. Furthermore, evaluating the impact of enzymes on polymeric lignin substrates requires analytical methods like liquid or gas chromatography combined with mass spectrometry, nuclear magnetic resonance [9, 10, 12]. The challenging evaluation of ligninolytic activities and their effect on native and technical lignins prevents the discovery of new efficient ligninolytic enzymes.

Electrochemical methods are particularly adapted to monitor redox enzymatic activities when substrates or products are electroactive species. They also show the advantages of being rapid, sensitive, adapted to heterogeneous media and do not require expensive apparatus. Species to be measured could be oxidized or reduced at the electrode resulting in current densities representative of their concentration. Consequently, electrochemical methods have the potential to circumvent the current lack of convenient methods for the characterization of ligninolytic and auxiliary enzymes active on polymers.

Among all electrode configurations, screen-printed electrodes (SPEs) are of particular interest due to their flexibility and low cost. This article outlines the potential of SPEs in identifying and characterizing novel enzymes involved in the depolymerization of lignocellulosic biomass. Firstly, the choice of screen-printed carbon electrodes (SPCEs) and paper-based electrodes is presented; secondly, an example of the application of SPCEs for the detection of small aromatic compounds and for the screening of peroxidase activities is outlined. Thirdly, the use of paper-based electrodes for the detection of LMPO activity, classified as an auxiliary activity in the carbohydrate active enzymes (CAZy) database (http://www.cazy.org/) [13], is demonstrated. Finally, the use of paper-based SPEs as a biomimetic substrate for the detection of depolymerizing ligninase activity will be presented.

2. Screen-printed electrodes and paper-based electrodes

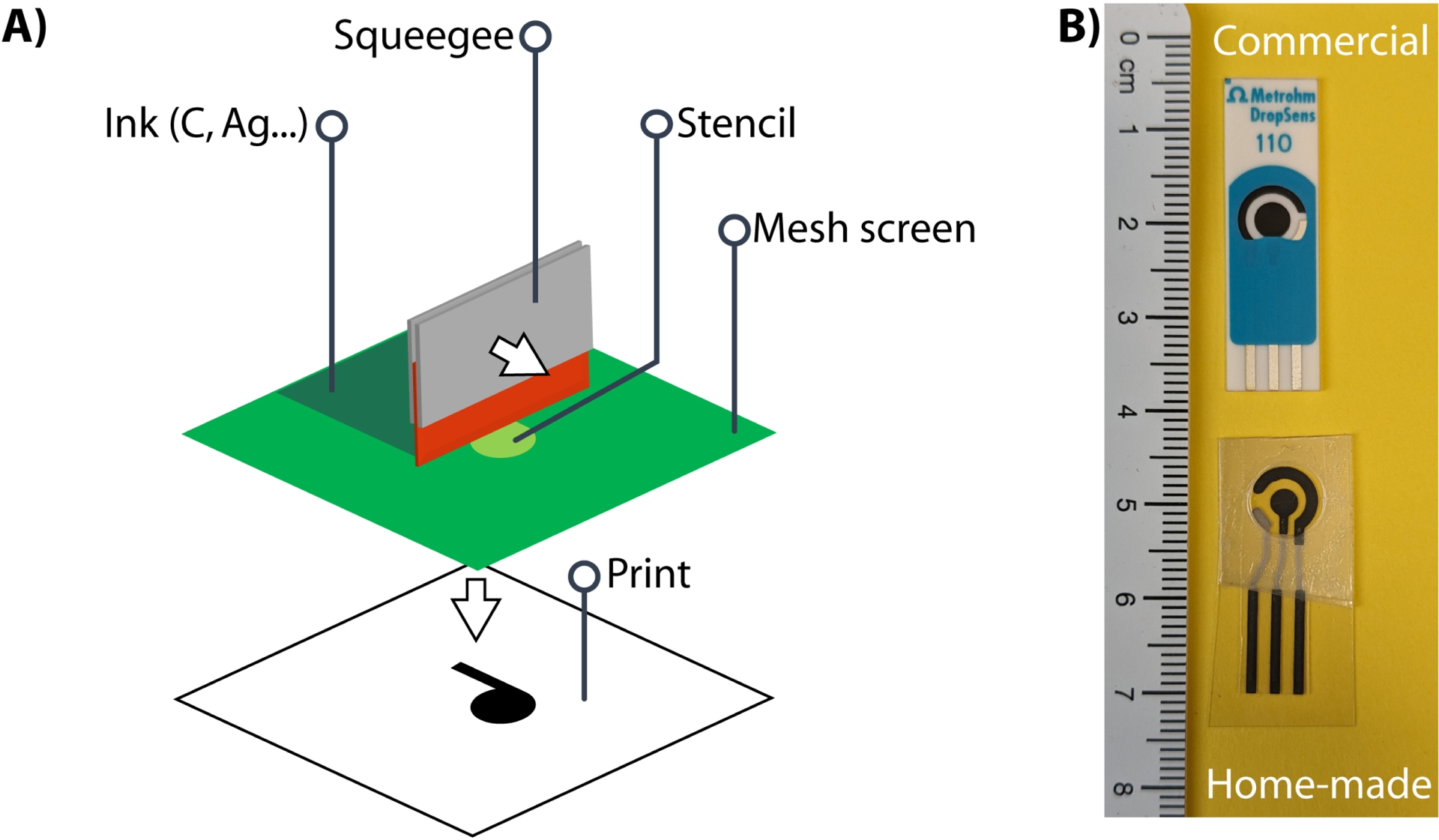

In analytical sciences, electrochemical detection is commonly used because it could be conducted in nearly all media (organic or aqueous media). This detection is not influenced by media transparency compared to optical methods (UV–vis spectroscopy, fluorescence) and the number of configurations is nearly infinite from a classical three-electrode system (work, reference, counter electrodes) in mL reactors to microelectrodes for in vivo sensing. In the field of biosensors, SPEs are usually preferred because of their commercial availability, because they are single-use, a requirement for diagnosis and because the geometry of the electrode or its composition (gold, silver, carbon) could be easily adapted to the need [14, 15]. Moreover, screen printing is a mature technology allowing mass production. The principle of screen printing is rather simple (Figure 1): a stencil is prepared by photolithography to obtain the electrode motif (permeable) on a mesh screen (impermeable). The substrate on which the electrodes are to be printed is plated below the mesh screen. The substrate could be plastic, paper, ceramics, printed-circuit board (PCB), fabric, or any material that could be obtained in a two-dimensional format. The electrode material provided as an ink or paste is applied on the top of the mesh screen and forced to pass through the stencil by a squeegee. The stencil-shaped ink is recovered on the substrate that is further cured at medium-to-high temperature to obtain a solid electrode. The inks and pastes are composed of the electrode’s conductive material (graphite particle, gold, silver, indium thin oxide) and a polymeric binder that ensure the stability of the electrode after curing, both dissolved in a solvent that evaporates during curing. The inks could also be doped with electrochemical mediators or nanomaterials, the most common being Prussian blue particles, carbon nanotubes, and gold nanoparticles.

(A) Scheme illustrating the principle of screen printing and (B) commercial and home-made screen-printed electrodes.

Since the key publication of Whitesides et al. in 2007 with paper [16], cellulosic material has been proposed as a substrate for SPEs. Since then, several reviews on the subject have been published [17, 18, 19]. The advantages of using paper, particularly absorbing paper such as Whatman #1 are numerous: (1) it is truly disposable by incineration whereas plastic is not, (2) paper and cellulosic material could be produced everywhere in the world at low cost, (3) paper technology is one of the most ancient in the world with numerous types of paper available, (4) the printing (or drawing) technologies on paper are also mature including inkjet, laser, and wax printing among others, (5) it is biocompatible and biodegradable (without considering the electrode material) and (6) the porosity of paper allows to design hydrophilic microfluidic channels together with the chromatographic (separation) properties of the cellulosic material. Whatman #1 paper for instance should be seen as a tridimensional porous material with interconnected cellulose microfibrils suitable for chemical modification close to the electrode but far enough to prevent passivation.

3. Application of SPCEs for the detection of small aromatic compounds and screening of peroxidase activities

3.1. SPCEs used for the detection of aromatic and phenylpropanoid compounds

Screen-printed electrodes (SPEs) are widely used for analytical purposes. Commercial electrodes offer the advantage of regular shapes, composition, and are ready to use, while home-made SPEs allow customizations, such as designing the shape of the electrodes, choosing the material substrate for the screen-printing, or adapting the composition of the inks. One of the common modifications of SPCEs is the functionalization of the carbon working electrode in order to form nanostructures at the electrode surface. For example, SPCEs modified by deposition of thin layers containing bismuth, gold, silver, multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNs) or carbon nanofibers (CNFs) are used for the detection and the quantification of heavy metals in water, beverages, food, and biologic samples [20]. Metabolites (e.g., glucose, ascorbic acid, uric acid), drugs (furaltadone, dopamine methotrexate, erythromycin metronidazole, estrogens), phenolic and polyphenolic compounds (bisphenol A, caffeic acid, tannins, catechins, flavonoids, etc.) are also usually detected by using layered SPEs [21]. These modifications are known to increase sensitivity, enabling lower detection thresholds and broader detection ranges.

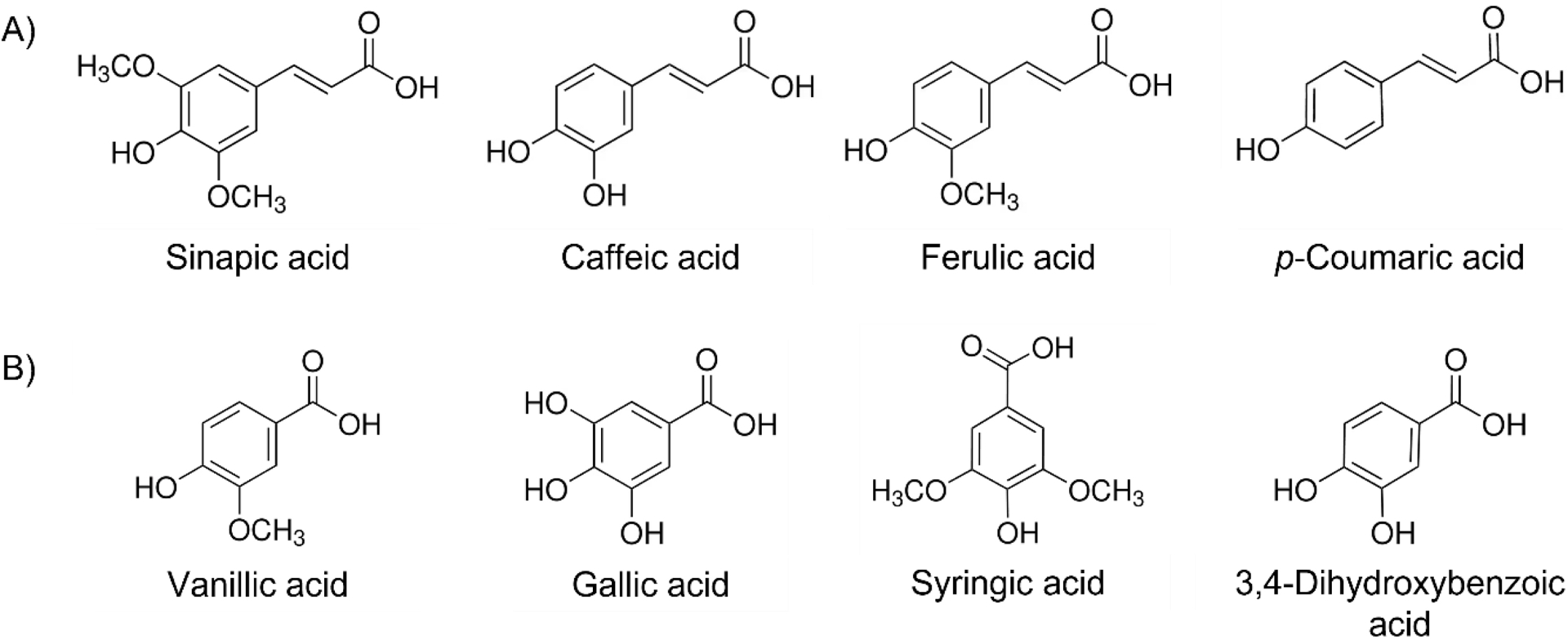

Hydroxycinnamic acids (Figure 2A) and hydroxyphenolic acids (Figure 2B) are small aromatic and electroactive compounds, allowing their detection by electrochemical methods. Caffeic acid is the most frequently analyzed hydroxycinnamic acid due to its favorable electrochemical response and its prevalence as a common antioxidant in food and beverages. Its detection and quantification can be achieved through the use of SPCEs, with or without electrode modifications, including the deposition of CNFs or MWCNs. Additionally, SPCEs can be modified with several other materials, including catechin (CT) decorated with gold nanoparticles (AuNP-CT) or tungsten disulfide supported by carbon black (SPE-CB-WS2/CT), cobalt(II,III) or cerium(IV) oxides nanoparticles (Co3O4/SPCE; CeO2 NPs), Graphene Oxide (GO), and reduced Graphene Oxide (rGO) itself decorated with gold (Au@rGO) [22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28]. These modifications enhance the quantification of hydroxycinnamic acids (Table 1). The linear range for the detection of hydroxycinnamic acids, using non-functionalized SPCEs, is comprised between 0.42 and 13.9 μM for caffeic acid between 26 and 515 μM for ferulic acid [29, 30]. Functionalization of the working electrode allows broadening the linear range and quantifying higher concentrations, up to 2 mM and 1 mM for caffeic and ferulic acids, respectively [23, 28]. Moreover, the modification of the carbon electrode decreases the oxidation potential, compared to non-modified carbon electrodes, improving the specificity of the electrode. This allows the detection and quantification of caffeic acid in a mixture containing ferulic and gallic acids, or sinapic, p-coumaric acids, present in red wine, rapeseed oil, or phyto-homeopathic tablets [22, 23, 24].

Structures of some (A) hydoxycinnamic acids and (B) hydroxyphenolic acids.

Electrochemical detection of hydroxycinnamic acids and gallic acid using SPCEs.

| Compound | Method | Electrode modifications1 | pH | Linear range (μM) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caffeic acid | CV | None (Dropsens 110) | <2 | 0.4–13.9 | [29] |

| CV | CNF (Dropsens 110) | 0.8–1000 | [22] | ||

| CV | Au@rGO (EcoBioServices) | 7 | 0.5–100 | [25] | |

| CV | rGO (EcoBioServices) | 7 | 0.5–100 | [25] | |

| CV | MWCNT (homemade SPEs) | <2 | 2.0–50 | [26] | |

| CV | CeO2 NPs (Dropsens 110) | 7.4 | 50–200 | [24] | |

| DPV | Co3O4 (-) | 7 | 0.2–272 | [27] | |

| DPV | rGO (-) | 7 | 0.2–2100 | [28] | |

| DPV | CB-WS2/AuNP-CT (EcoBioServices) | 7 | 0.4–112.5 | [23] | |

| Ferulic acid | CV | None (paperbased homemade SPCE) | 5 | 26–515 | [30] |

| CV | CNF (Dropsens 110) | 0.8–1000 | [22] | ||

| Sinapic acid | DPV | CB-WS2/AuNP-CT (EcoBioServices) | 7 | 0.7–125.0 | [23] |

| p-Coumaric acid | DPV | CB-WS2/AuNP-CT (EcoBioServices) | 7 | 1.4–93.7 | [23] |

| Gallic acid | CV | CeO2 NPs (Dropsens 110) | 7.4 | 2–20 | [24] |

CV: cyclic voltammetry; DPV: differential pulsed voltammetry; CNF: carbon nanofibers; rGO: reduced graphene oxide; MWCNT: multi-walled carbon nanotubes; CeO2 NPs: cerium oxide nanoparticles; Co3O4: cobalt oxide; CB-WS2/AuNP-CT: tungsten disulfide supported by carbon black/catechin decorated with gold nanoparticles. 1Commercial or homemade SPCEs are indicated.

Additionally, caffeic acid oxidation leads to the formation of electroactive dimers and contributes to the modification of the electrode surface. Furthermore, caffeic acid can also react with other electroactive compounds through its quinine equivalent [31].

3.2. Application of SPCEs to the screening of peroxidase substrates

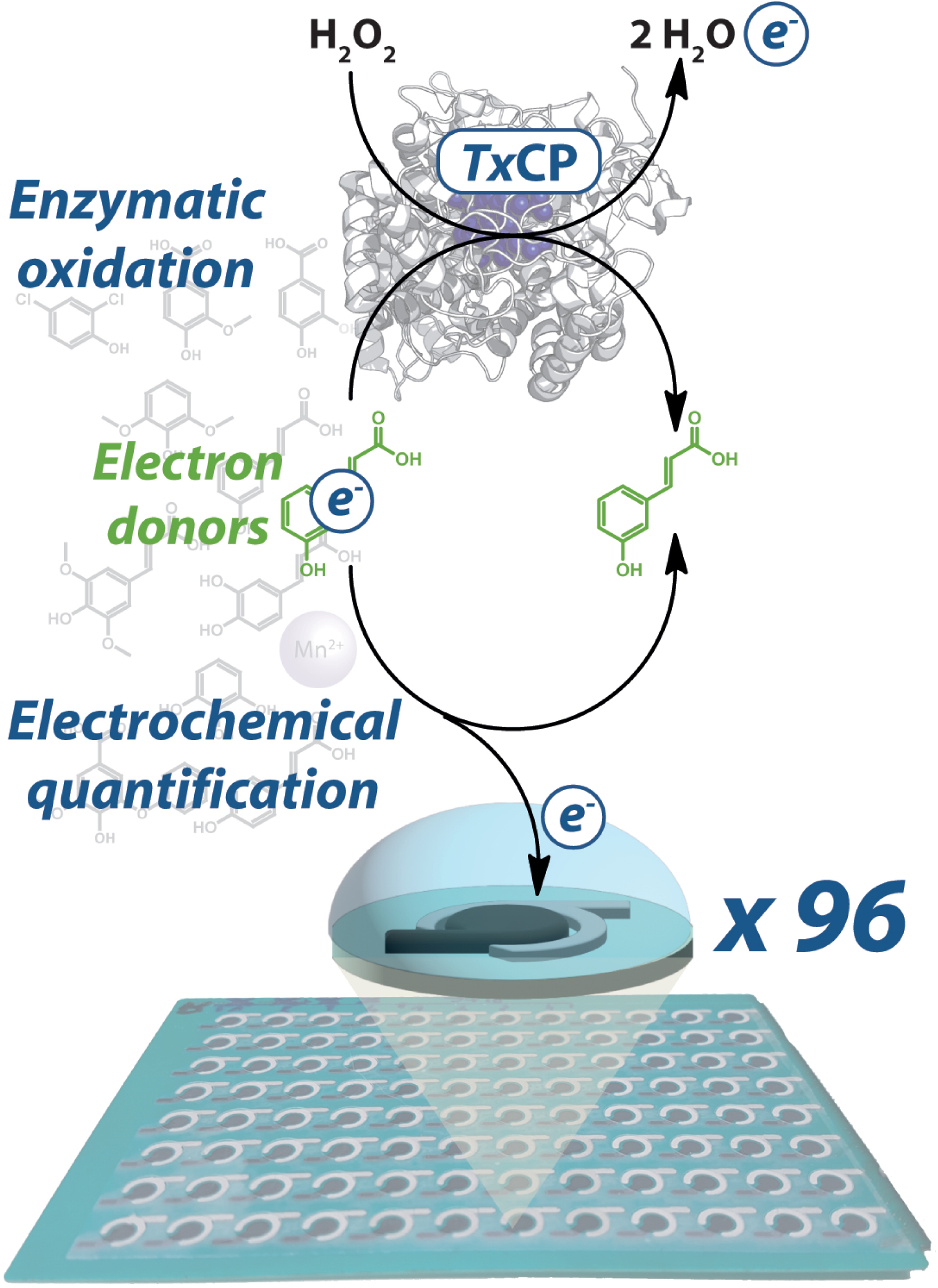

In a recent work, the electrochemical properties of hydroxycinnamic and hydroxybenzoic acids are used to develop the first electrochemical screening assay for the detection of ligninase activity [32]. The assay is applied to identify small phenolic molecules derived from lignin as substrates of a newly discovered bifunctional bacterial catalase–peroxidase. Peroxidase activity consists in the oxidation of a substrate in the presence of H2O2 as electron acceptors. Peroxidases are often expressed by microorganisms when they are fed with lignin-rich substrates. Furthermore, hydroxycinnamic and hydroxybenzoic acids have been identified as peroxidase substrates, which suggests that these activities contribute to the depolymerization of lignin. Additionally, it has been reported that catalase–peroxidases assist the main lignin-degrading enzymes and further oxidize dimers or monomers after the depolymerization of the lignin macromolecule [4].

The strategy of the screening assay developed in this study is based on the use of lignin-derived aromatic substrates as electron donors. The potential of hydroxycinnamic and hydroxyphenolic acids, including 3,4-dihydroxybenzoic, sinapic, vanillic, syringic, o-coumaric, caffeic, and p-coumaric acids as substrates is investigated. These acids are selected based on their proven ability to generate anodic current at +800 mV vs Ag|AgCl. The oxidation of these aromatics substrates by the enzyme was monitored by intermittent pulsed amperometry (IPA) on 96-SPCE plates (Figure 3). An oxidation overpotential of +800 mV vs Ag|AgCl is applied to detect electroactive species and to quantify the substrate depletion after 4 h incubation in the presence of the enzyme. The results obtained by the electrochemical method are consistent with those obtained by spectrophotometric methods using azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS) and Mn2+ as the positive controls and veratryl alcohol as the negative one.

Strategy applied for the screening of small lignin-derived compounds as substrates of a catalase–peroxidase (TxCP) using SPCEs (adapted from [32]).

The results show that the electrochemical SPCE-based screening is applicable to detect the peroxidase activity. It also evidences that the catalase–peroxidase from the bacteria Thermobacillus xylanilyticus is able to oxidize 3,4-dihydroxybenzoic (3,4-DHB), sinapic, vanillic, syringic, o-coumaric, caffeic, and p-coumaric acids, whose current densities differ significantly (>10%) in the presence of enzyme, compared to the standard reaction without enzyme (Table 2).

Monomers oxidized by the catalase–peroxidase from Thermobacillus xylanilyticus (TxCP) and screened by intermittent pulsed amperometry (adapted from [32]).

| Compound | Current density (μA⋅cm−2) | Variation (%) of the current density | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Without TxCP | With TxCP | ||

| Caffeic acid | 417 ± 18 | 620 ± 103 | 49 |

| 3,4-DHB acid | 498 ± 62 | 348 ± 52 | 30 |

| Vanillic acid | 90 ± 7 | 51 ± 5 | 44 |

| Ferulic acid | 50 ± 7 | 62 ± 9 | 23 |

| Syringic acid | 42 ± 5 | 24 ± 4 | 42 |

| Sinapic acid | 331 ± 40 | 168 ± 22 | 49 |

| o-coumaric | 68 ± 9 | 28 ± 7 | 59 |

| p-coumaric | 61 ± 2 | 101 ± 16 | 65 |

| MnCl2 | 455 ± 27 | 321 ± 19 | 30 |

| ABTS | 289 ± 48 | 205 ± 15 | 29 |

| Veratryl alcohol | 22 ± 4 | 20 ± 1 | <10 (non significant) |

4. Paper-based SPCEs applied to the measurement of LPMO activities

4.1. Consumption of ascorbic acid by LPMO activity monitored by electrochemical methods

Lytic polysaccharide monooxygenases (LPMO, EC 1.14.99.53-56) are copper-dependent oxidative enzymes catalyzing the depolymerization of polysaccharides or oligosaccharides in the presence of an oxidant and an electron donor. The oxidation of C1 and/or C4 carbon of the glycosidic backbone, causing the cleavage of the glycosidic bonds, results from a monooxygenase activity in the presence of oxygen or from a peroxygenase activity in the presence of hydrogen peroxide (Equations (1) and (2), respectively) [33, 34, 35, 36]. In the absence of a glycosidic substrate, an oxidase activity is also observed (Equation (3)) [37].

| \begin {eqnarray} \mbox {Monooxygenase reaction: } \mathrm {R{-}H} + {\mathrm {O}}_{2} + 2{\mathrm {e}}^{-} + 2{\mathrm {H}}^{{+}} \stackrel {\mathrm {Cu}(\mathrm {II})}{\longrightarrow } \mathrm{R{-}OH} + {\mathrm {H}}_{2}\mathrm {O} \label {eq1}\end {eqnarray} | (1) |

| \begin {eqnarray} \mbox {Peroxygenase reaction: } \mathrm {R{-}H}+ {\mathrm {H}}_{2}{\mathrm {O}}_{2} \stackrel {\mathrm {Cu}(\mathrm {I})} {\longrightarrow } \mathrm{R{-}OH} + {\mathrm {H}}_{2}\mathrm {O} \label {eq2}\end {eqnarray} | (2) |

| \begin {eqnarray} \mbox {Oxidase reaction: } {\mathrm {O}}_{2} + 2{\mathrm {e}}^{-} + 2{\mathrm {H}}^{+} \stackrel {\mathrm {Cu}(\mathrm {II})}{\longrightarrow } {\mathrm {H}}_{2}{\mathrm {O}}_{2}\label {eq3} \end {eqnarray} | (3) |

As LPMOs are three-substrate enzymes (oxidant, electron donor, and glycosidic substrate), the measurement of their activity is delicate. Most of the published studies focus on the quantification and identification of some short-length oligosaccharide products using liquid chromatography and/or mass spectrometry [38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45]. Recently, a method was developed to measure the peroxygenase activity using a rotating disc electrode selective to hydrogen peroxide through the presence of Prussian blue as the electrocatalyst [46]. This method is adapted to fundamental studies of the enzymatic reaction, but is less adapted to screen applicative conditions in complex media.

As explained in 1 and 2, SPCEs are adapted to the needs of high-throughput screening. In this context, we developed an electrochemical method to measure the initial rates of the oxygenase reaction (equally monooxygenase and peroxygenase reactions) catalyzed by LPMOs. The method is based on the direct detection by IPA of the remaining electron donor, without further chemical derivation or separation steps. Ascorbic acid (1 mM) is used as the electron donor (Equation (4)) in reactions containing a suspension of microcrystalline cellulose 1% (w/v) and LPMO9C isolated from Neurospora crassa (NcLPMO9C). The reactions are performed in test tubes at 45 °C, with regular sampling. The remaining ascorbic acid is quantified at +0.6 V vs Ag|AgCl by IPA onto SPCEs.

| \begin {eqnarray} \text {Detection of ascorbic acid: } \text {Ascorbic acid} \longrightarrow \text {Dehydroascorbic acid}+ 2{\mathrm {e}}^{-} + 2\mathrm {H}^{+}\label {eq4} \end {eqnarray} | (4) |

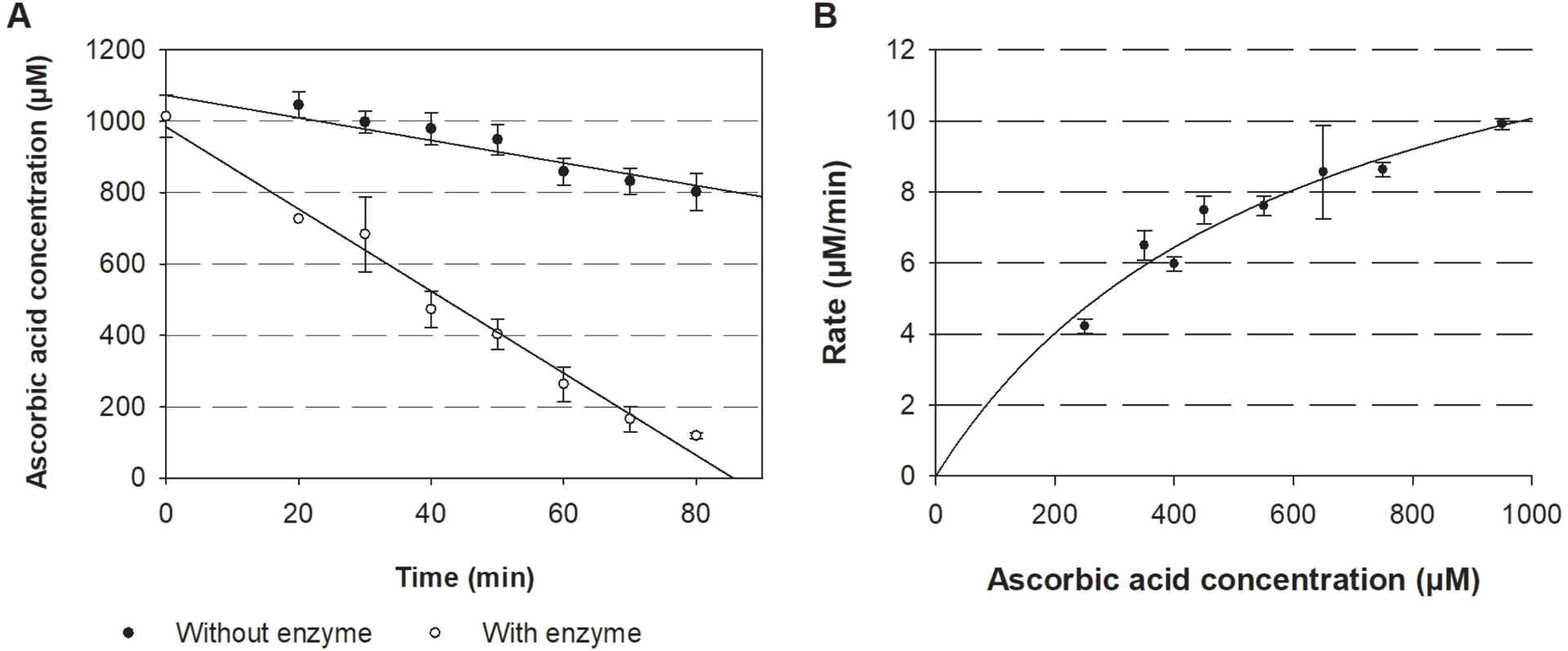

The consumption of ascorbic acid by LPMOs was linear over at least 70 min (Figure 4A). The decrease of the signal, due to ascorbic acid oxidation at 45 °C, was less than 20% in 70 min. In the same time, around 80% of the ascorbic acid disappeared in the presence of LPMO, leading to a specific activity of 196 nmol⋅min−1⋅mg−1. Apparent kinetic constants for ascorbic acid with microcrystalline cellulose as co-substrate obtained from Michaelis–Menten plots are $K_{\mathrm{m}}^{\mathrm{App}} = 601\pm 166$ μM and $k_{\mathrm{cat}}^{\mathrm{App}} = 16.1\pm 2.3$ min−1 (Figure 4B).

(A) Kinetics of ascorbic acid consumption and (B) Michaelis–Menten plots corresponding to ascorbic acid consumption rates by NcLPMO9C. Reactions are performed in the presence of 1 μM NcLPMO9C, ascorbic acid (1 mM for (A), 250–1000 μM for (B)), microcrystalline cellulose 1% (w/v) in sodium phosphate buffer (20 mM, pH 6) incubated at 45 °C (n⩾3).

These results highlight that the direct measurement of ascorbic acid consumption by electrochemistry appears to be a suitable alternative to spectrophotometric methods for the measurement of oxygenase LPMO activities.

4.2. Evaluation of filter paper instead of microcrystalline cellulose as substrate for the electrochemical detection of LPMO activity

The interest in LPMO is increasing since it has been proposed that some are active on recalcitrant cellulose and, therefore could play a key role in the enzymatic deconstruction of lignocellulosic biomass. Indeed, these enzymes are supposed to reduce the crystallinity of cellulose and operate synergistically with glycoside hydrolases that are active on amorphous cellulose [39, 47, 48, 49].

The three-substrates LPMO is ideal for the development of original screening methods for depolymerizing enzymatic activities including paper-based SPCE as substrate. Indeed, Whatman paper made of cellulose can constitute the polymeric substrate for the reaction. Paper-based electrodes present interesting properties that could be exploited for a screening method. In this context, we investigated the possibility of measuring LPMO activity using Whatman paper instead of microcrystalline cellulose as the substrate for NcLPMO.

The rate of ascorbic acid consumption using 1% (w/v) of both cellulosic substrates was measured by IPA with different enzyme concentrations at 45 °C. No significant differences between Whatman paper and microcrystalline cellulose substrates were observed regarding ascorbic acid consumption rates (15.7 ± 2.2 min−1 and 18.6 ± 3.5 min−1, respectively). This opens the way for paper-based SPCEs as a screening tool to detect LPMO activity.

4.3. Screening of electron donor using SPCEs

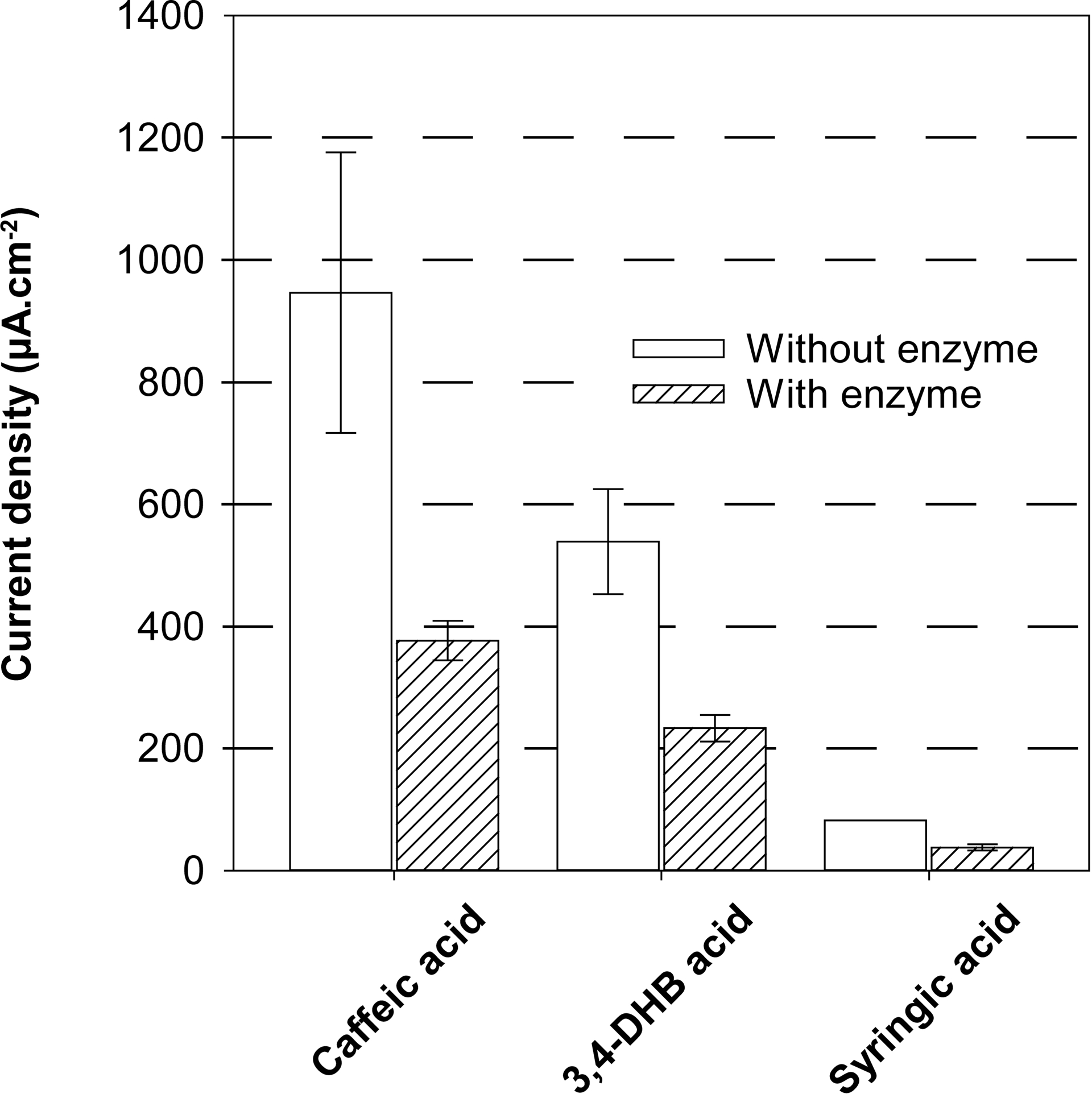

LPMOs, notably NcLPMO9C, oxidize lignin-derived electroactive species obtained from biomass pretreatments [50]. However, due to the molecular complexity of the crude liquid lignin fraction obtained after lignocellulosic biomass pretreatment, structural analogs of lignin monomers are used instead of real samples. Therefore, NcLPMO9C’s ability to oxidize three putative electron donors (caffeic, 3,4-DHB, and syringic acids) was investigated. Cyclic voltammetry of these aromatic acids showed oxidation peaks between +0.46 and +0.7 V vs Ag|AgCl in sodium acetate buffer (50 mM, pH 5) (Table 3). The reduction potential of caffeic acid and 3,4-dihydroxybenzoic acid is +0 V vs Ag|AgCl, whereas the oxidation of syringic acid is irreversible. In order to quantify simultaneously the remaining substrate after 2 h of enzymatic reaction, an overpotential of +0.8 V vs Ag|AgCl was applied on the SPCE.

Electrochemical characteristics of the electron donors measured using carbon screen-printed electrodes in acetate buffer (50 mM, pH 5).

| Electron donor | Oxidation potential (V vs Ag/AgCl) | Reduction potential (V vs Ag/AgCl) | Sensitivity at +0.8 V vs Ag/AgCl (μA⋅cm−2⋅μM−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ascorbic acid | +0.46 | n.d. | 0.467∗ |

| Caffeic acid | +0.5 | 0 | 0.796 |

| 3,4-DHB acid | +0.65 | 0 | 0.498 |

| Syringic acid | +0.7 | n.d. | 0.243 |

∗At +0.6 V vs Ag/AgCl for ascorbic acid; n.d.: not detected.

In the absence of NcLPMO9C, the current density did not evolve after 2 h at 45 °C for caffeic and 3,4-DHB acids (946 μA⋅cm−2 and 539 μA⋅cm−2, respectively) while it strongly decreased from 390 μA⋅cm−2 to 82 μA⋅cm−2 for syringic acid, meaning it is unstable in these conditions. The sensitivities were also different for the electron donors (0.243 μA⋅cm−2⋅μM−1 for syringic acid, 0.498 μA⋅cm−2⋅μM−1 for 3,4-dihydroxybenzoic acid, and 0.796 μA⋅cm−2⋅μM−1 for caffeic acid) (Table 3).

When NcLPMO9C (1 μM) was incubated with ascorbic acid and Whatman paper (1% w/v) for 2 h, the current density was in the background showing the full conversion of ascorbic acid. When caffeic, 3,4-DHB or syringic acids were used as substrates, the current densities decreased by 60, 56 and 54%, respectively (Figure 5), confirming that these compounds are electron donors for NcLPMO9C. This also suggests some guidelines regarding the redox potential of the electron donor, as it appears that species having an oxidation potential up to +0.7 V vs Ag|AgCl could supply electrons to NcLPMO9C. The role of these compounds as electron donor for LPMOs was also recently shown by following the apparition of oxidized oligosaccharide using HPLC [40]. While this transformation requires a 20-hour incubation followed by HPLC analysis, only two hours are necessary with our electrochemical method to identify electron donors as well as to estimate the enzymatic conversion rate (5 μM⋅min−1).

Activity of NcLPMO9C 1 μM using several electron donors: caffeic acid, 3,4-dihydroxybenzoic acid, and syringic acid. Reactions are performed with Whatman paper as cellulosic substrate 1% (w/v), electron donor 1 mM and incubation for 2 h at 45 °C. Current density is measured by intermittent pulsed amperometry at a fixed potential of +0.8 V vs Ag|AgCl.

Using IPA, up to 96 independent samples could be measured at a time using a given potential in 1 min [51, 52, 53]. The thermolability of some electron donors is pointed out, but in this work, all reactions were performed at 45 °C (optimal temperature of LPMOs). However, as the duration of analysis is short and the sensitivity of the method is high, the reactions could also be performed at room temperature. This enables rapidly identification of the electron donor and carbohydrate substrate for one or more LPMOs, as well as acquisition of kinetic parameters.

4.4. Important remarks

Studying and measuring LPMO activities is challenging because three substrates are involved and because several mechanisms are proposed. The methods currently applied to monitor the reaction are based on the quantification of the glycosidic products after hours of incubation, which is time-consuming and not representative of the early stage of the reaction. In this work, we present the development of a general electrochemical method based on monitoring electron donor consumption by LPMOs, with reduced analysis time for fast characterization of LPMO oxygenase activity.

The reaction rates of NcLPMO9C were determined as well as apparent Michaelis–Menten constant for ascorbic acid in less than 1 h. The values obtained are in agreement with published ones. Activities were equivalent, either using the cellulosic substrate (microcrystalline cellulose) or Whatman paper, confirming the possibility of using paper-based SPCEs directly as substrate. Therefore, this electrochemical method is found to be suitable to identify electron donors for LPMOs. This is a proof-of-concept highlighting that electrochemical electron donor detection can be used for fast monitoring of LPMO oxygenase activity using natural substrates, i.e., without the use of chromophores or fluorophores. Moreover, the possibility of acquiring a large amount of data using IPA together with 96 SPEs open the way to electrochemical high-throughput screening assays for LPMOs.

5. Paper-based SPCE as a biomimetic substrate for the detection of lignin depolymerizing enzymes

Lignin, a hydrophobic and amorphous heteropolymer, mainly composed of phenyl propanoid units, is one of the three polymers (with cellulose and hemicellulose) composing the secondary plant cell wall and the lignocellulosic biomass. As lignin constitutes up to 40% of the plant cell wall, it is considered to be the most abundant biobased source of aromatic compounds such as vanillin, syringaldehyde, acetovanillone, ferulic acid or vinyl guaiacol [4, 55].

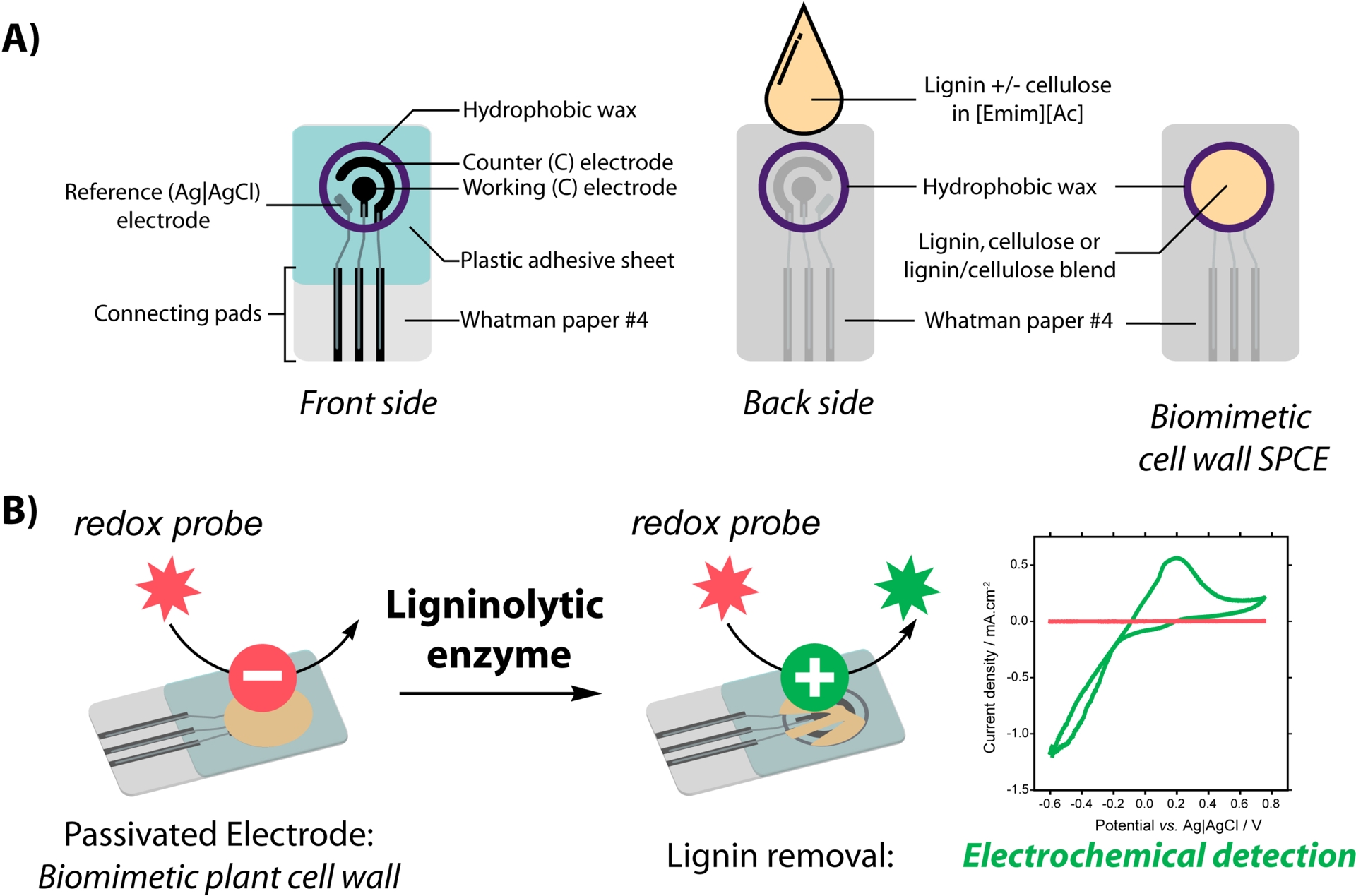

The conversion of lignin into smaller aromatic molecules of interest is challenging owing to its structural heterogeneity. Enzymatic depolymerization of lignin is a promising approach [56]. However, the characterization of new ligninolytic enzymes is challenging due to the lack of relevant methods. Electrochemical measurements are ideal for measuring redox reactions. This non-optical method can measure different substances in a few minutes, meaning that electrochemical methods may be useful to measure ligninolytic processes more easily. In recent years, paper-based electrodes have emerged as tools in the field of bioelectrochemistry. This is due to a number of factors, including their ease of use, biodegradability, and straightforward fabrication [17, 57, 58]. In a recent work, we described the development of a new methodology using paper-based SPCEs to characterize the activities of ligninolytic enzymes [54].

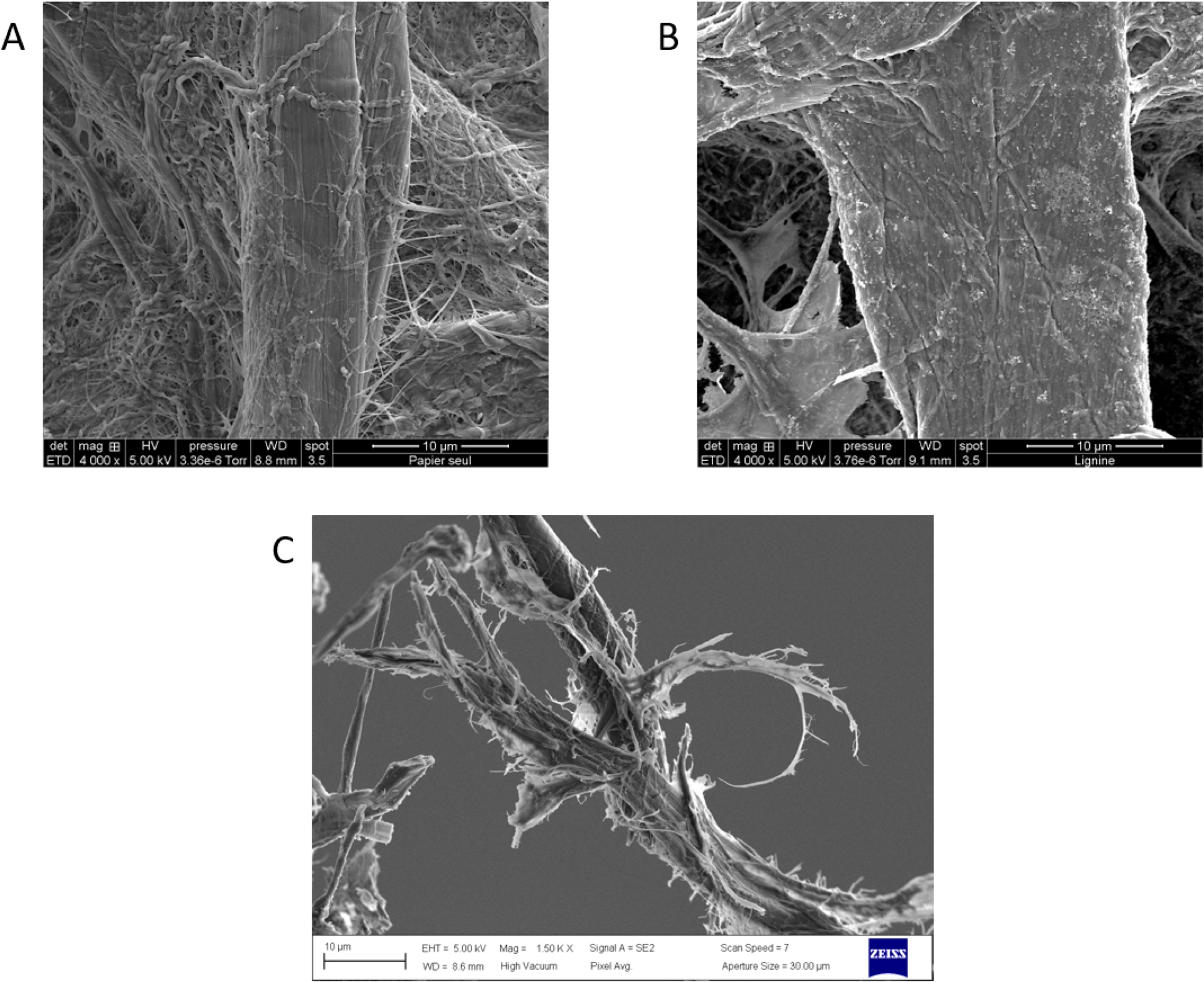

The strategy relies on the preparation of an integrated substrate/detection system composed of a “biomimetic” plant cell wall on the back side of a paper-based SPCE (Figure 6A). The polymeric substrate is formed by cellulosic material from Whatman paper and by lignin coated around the cellulose microfibrils after ionic liquid-assisted precipitation. Characterization of the substrate/electrode by profilometry and electronic microscopy showed that lignin is homogeneously deposited as nanoparticles around the cellulosic fibers (Figure 7A, B). These nanoparticles are not only deposited at the surface but deeply penetrate into the paper, mimicking polymer organization in the plant cell wall where lignin acts as a matrix engulfing cellulose and hemicellulose. Electrochemical characterization of the substrate/electrode highlighted that, when deposited in sufficient amount, the coated lignin constitutes an electrical insulator, preventing access to the electrode by soluble compounds (e.g., a redox probe). Depolymerization of this biomimetic plant cell wall by the ligninolytic enzyme catalase–peroxidase from Thermobacillus xylanilyticus (TxCP) is evidenced by the recovery of the $\mathrm{Fe(CN)}_{{6}}^{3^-/4^-}$ redox signal by cyclic voltammetry (Figure 6B). Detection of the probe is correlated with physical modification of the fibers as observed by SEM. Indeed, aggregates coating the fibers are no more observed and fibers are strongly degraded after incubation with TxCP (Figure 7C), indicating that the insulating barrier formed by the coated lignin is weakened by the enzyme-catalyzed reaction.

(A) Scheme of the biomimetic SPCE configuration and preparation: First a wax circle is printed on filter paper (diameter = 6 mm); secondly, on the front side, carbon and Ag|AgCl inks are screenprinted. Then, lignin (blended with cellulose) is deposited on the back side of the paper electrode. (B) Detection of ligninase activity is made possible by recovering the signal corresponding to a redox probe by cyclic voltammetry after action of the enzyme (green line) (adapted from [54]).

SEM analysis showing (A) cellulose fibers at the back side of bare paper-based electrodes, (B) biomimetic substrate-electrodes impregnated with lignin showing nanoparticles coating the cellulose fibers, (C) biomimetic substrate-electrodes impregnated with lignin after incubation with catalase–peroxidase, showing degraded cellulose fibers (adapted from [54]).

These results highlight the interest of developing paper-based SPCEs to detect ligninolytic activity and could be used for rapid screening of efficient ligninolytic enzymes. This method could be further improved for the electrochemical detection of products during oxidative depolymerization of lignin. Such a strategy could help solve the technological challenge of rapidly identifying robust biocatalysts with ligninolytic activities.

6. Conclusion

The discovery of new enzymes active on plant wall polymers is a major challenge for the development of biochemical routes for the valorization of lignocellulosic biomass and co-products from agricultural activities. Electrochemical methods involving screen-printed carbon electrodes have shown their interest in detecting, characterizing and quantifying small compounds, and consequently in screening for enzymatic activities associated with these compounds. For example, the detection of small aromatic compounds, such as hydroxycinnamic and hydroxyphenolic acids, potentially derived from lignin depolymerization, enables the detection of peroxidase or lytic polysaccharide monooxygenase activities by cyclic voltammetry or intermittent pulsed amperometry. Modifying or functionalizing the electrodes could improve the detection of compounds of interest, thus refining the determination of the enzymatic activities. The use of paper as support for screen-printed carbon electrodes adds another dimension for screening, in particular for cellulose-active enzymes such as lytic polysaccharide monooxygenases. In this configuration, a certain proximity between the enzyme, its cellulosic substrate and the electrode used for detection was achieved. This proximity can help to overcome substrate accessibility issues encountered in heterogeneous media. Paper-based electrodes allow exploiting the three-dimensional structure of paper to design biomimetic substrates of the plant wall, involving several types of interlocking polymers. Finally, the possibility of custom-designing the shape of the electrodes, and in particular of miniaturizing the systems, notably to work in 96-electrode format, opens the way to a wealth of potentialities in the context of high-throughput screening of enzymatic activity and reaction conditions.

Declaration of interests

The authors do not work for, advise, own shares in, or receive funds from any organization that could benefit from this article, and have declared no affiliations other than their research organizations.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully thank Dr. Varnái, Dr. Forsberg and Pr. Einjsink from the Norwegian university of life sciences for the supplying of LPMO.

CC-BY 4.0

CC-BY 4.0