1. Introduction

The application of enzymes for synthetic purposes usually relies on a restricted set of proteins, commonly known by the biocatalytic community or even commercially available ones. The knowledge of their features (substrate scope, activity, stability, structure …) reassures researchers, who tend to use them by default or for convenience. However, these properties may not always be the most suitable for specific reactions (or cascade reactions). Every organism has its own arsenal of enzymes which, from a synthetic application point of view, constitutes a truly diverse reservoir of sequences and structures. It is up to us to make the most of it, to offer an enzymatic toolbox of great diversity. When required, each enzyme can be adapted to a targeted reaction, which may be very different from that for which it has naturally evolved, by engineering or directed evolution. So genome mining for enzyme discovery is still of interest and must not be opposed to protein engineering. As mentioned by NGuyen et al., “a treasure trove of enzyme chemistry awaits to be uncovered” [1]. As a matter of fact, the number of available sequences increases daily, thanks in particular to the development of large-scale sequencing projects for marine and terrestrial biodiversity. The number of available protein sequences has increased more than 20-fold in the last 6 years, with more than 2.4 billion reported in 2023 compared to approximately 123 million in 2018 [2, 3]. According to some reports, metagenome mining has a high success rate (99%) in identifying diverse genes encoding for novel enzymes, which are crucial for biocatalytic applications [4]. Sequences coding for characterized protein homologs and many of unknown functions are added to (meta)genomic databases, already rich in proteins that can be used for synthesis [5]. The quest for other biocatalysts among biodiversity is important to enlarge the spectrum of substrates and reactions but is not restricted to this aspect [6]. For industrial applications, enzyme stability is an essential parameter. Recent studies have reported the discovery of unique enzymes, especially in the “hidden sequence space” by metagenomic mining, which exhibit enhanced properties (e.g., thermostability, substrate specificity), making them valuable for various industrial applications, including pharmaceutical ones. The impact of metagenomics on biocatalysis is undeniable [7, 8].

However the prospection for enzymes with enhanced catalytic properties and specific features is not straightforward. Discovering enzymes within the extensive array of available metagenomic data is a significant challenge, requiring the development of innovative computational and functional screening tools. The integration of bioinformatics into biocatalysis facilitates a more systematic approach to the discovery and design of novel biocatalysts. Biocatalysis and bioinformatics must work in synergy to optimize the identification of enzymes of interest within biodiversity and minimize the number of candidates to be screened. Bioinformatics tools enable the identification of enzyme functions and the prediction of their properties, mainly from sequence-based and function-based screening and modeling [9, 10]. The analysis of protein superfamilies allows the rational selection and design of enzymes with improved catalytic properties, focusing on sequence–function relationships and catalytic residues, including their conformational variation [11, 12]. Identification and analysis of biosynthetic gene clusters is also a powerful approach to select key enzymes [13]. Furthermore, the entire biocatalytic process, from enzyme discovery to the design of the retrosynthetic pathway, is increasingly being enhanced and streamlined through the integration of deep neural networks and artificial intelligence (AI). All our knowledge of enzyme natural diversity helps in parallel the development of hybrid generative AI methods, so that we can progressively customize the dream enzyme for each application [14].

Here, we present case studies from our laboratory illustrating the potential outcomes of genome mining approaches and the input of bioinformatic workflows in their efficiency to: (1) identify enzymes complementary to those already characterized; (2) leverage known enzyme mechanisms to modify natural reactions; (3) discover entirely new enzyme scaffolds for a specific transformation. The results in terms of diversity in sequences, structures and synthesis potential are described. Without going into detail, we present in each case the (meta)genome mining method used to select candidate enzymes within biodiversity.

2. Genome mining to expand biocatalytic properties within established enzyme families

2.1. Example with the nitrilase activity

Exploring the biodiversity for native enzymes is an efficient way to broaden the scope of already known or even commercially available biocatalysts [15]. It worked especially well for nitrilases (EC 3.5.5), enzymes enabling the hydrolysis of nitriles into their corresponding carboxylic acids. This biotransformation has been studied for years due to the benefits it provides over the chemical transformation [16]. In 2012, when we started this project, characterized nitrilases were still scarce, especially for regio- and stereospecific applications. We applied a genome mining approach to identify new nitrilases within biodiversity and proposed three preparative scale reactions for applications of this expanded enzymatic toolbox [17].

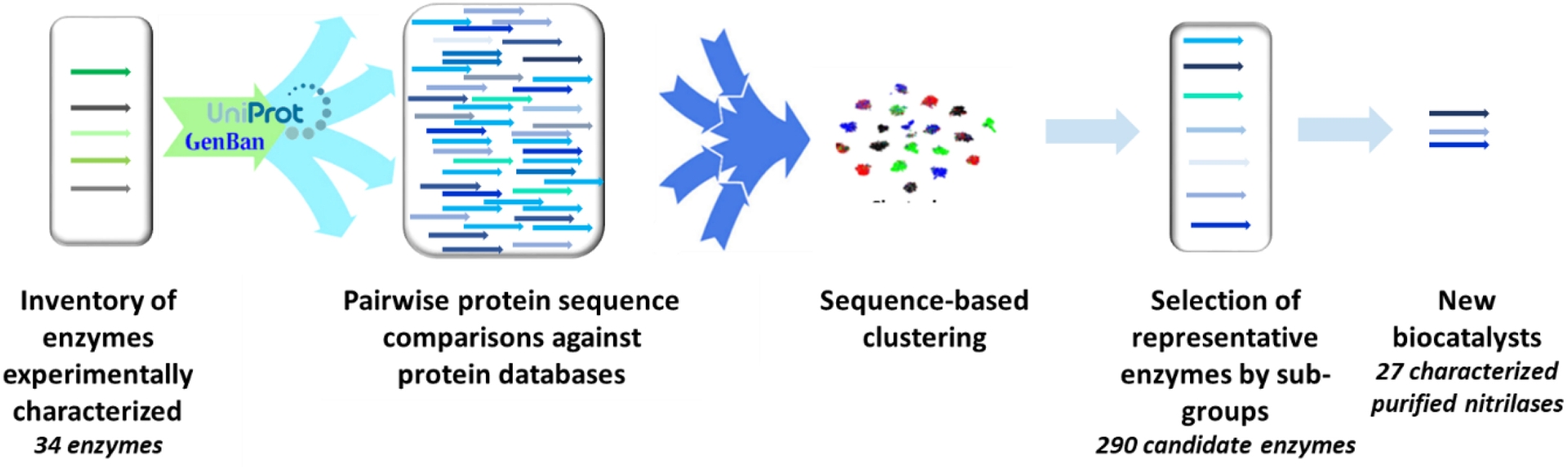

In our process, exploring enzyme diversity first requires the careful selection of experimentally validated enzymes of diverse sequences to recover the greatest possible diversity. We selected 34 reference nitrilases, based on their activity toward various nitriles and, noteworthily, without taking into account their annotation or their organism of origin. The corresponding protein sequences were used to fish out prokaryotic enzymes in the UniprotKB database using a basic local alignment search tool (BLAST) sequence alignment [18]. Only sequences presenting over 30% identity on more than 80% of their length were kept. We then classified the sequences on the basis of 80% sequence identity in order to have isofunctional clusters. By choosing a few representatives per cluster, or just one, we ensured that we covered the biodiversity being explored while minimizing the number of proteins to be screened. The representatives were chosen based on genome availability in the Genoscope strain collection (700 prokaryotic species) and in an in-house wastewater treatment plant metagenomic collection of sequences (“Cloaca maxima”), alongside nucleic sequence features like guanine-cytosine content. DNA was purchased for cluster representatives that were unavailable in the internal collection. This workflow, integrated within the FunDivEx platform, is automated. The pipeline resulted in the identification of 290 candidate nitrilases, mostly annotated as hydrolases or carbon-nitrogen hydrolases. After overexpression in Escherichia coli (E. coli) BL21(DE3) cells, we obtained 163 candidate proteins, each tagged with a hexahistidine tag to simplify subsequent purification (Figure 1).

Pipeline for the selection of candidate enzymes by sequence-driven approach within the FunDivEx platform. Source: Figure adapted from Zaparucha et al. [15].

The 163 candidates were screened against 25 nitrile substrates grouped into six categories by chemical properties (saturated, unsaturated, arylaceto-, α-hydroxylated, β-hydroxylated, and β-aminated) using a sensitive UV-spectrophotometric assay. This assay, adapted here for the first time for nitrilase activity screening, leverages glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH) to catalyze a non-limiting reaction with release of ammonia (NH3), enabling kinetic measurement through NADH consumption monitored at 340 nm, which correlates with initial NH3 concentration and thus with nitrilase activity. We identified 125 nitrilases with varying activity levels across the substrates; while some exhibited substrate specificity, most were promiscuous, efficiently hydrolyzing nitriles with aromatic groups (77%), saturated nitriles (60%), and unsaturated nitriles (50%). Notably, NIT93 from Lysinibacillus sphaericus (UniProtKB: B1HZZ4) and NIT278 from Syntrophobacter fumaroxidans (UniProtKB: A0LKP2) were active across all six substrate groups, displaying marked substrate promiscuity. The top 37 nitrilases were subsequently purified and reassessed, yielding 27 enzymes with activity spanning nearly the entire substrate range, except for 3-aminopentanenitrile.

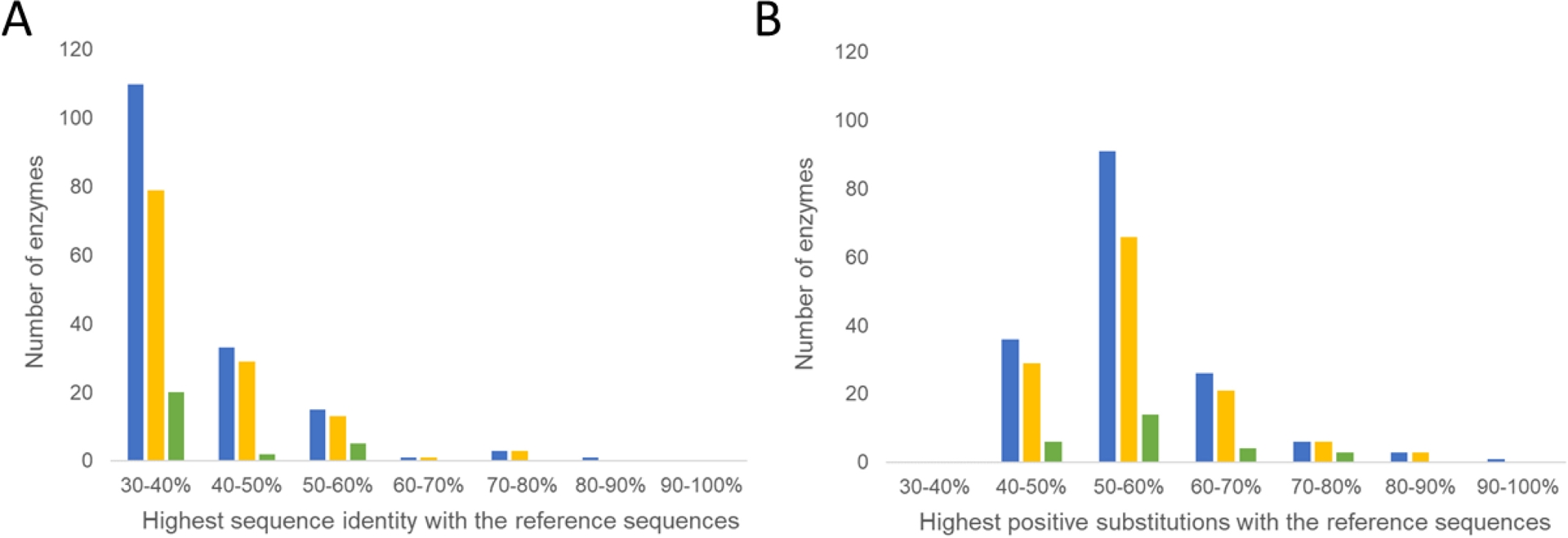

As shown in Figure 2, the selection of homologs with less than 40% sequence identity resulted in nitrilases active on a structurally diverse set of nitriles, capturing enzymatic diversity around the reference sequences. It’s interesting to note that most candidates have more than 50% amino acid similarity with the reference enzymes (Figure 2B), with over 75% of the top 27 nitrilases presenting 30–40% sequence identity, underscoring the advantage of genome mining across a broad sequence landscape to identify homologs down to 30% identity. Of the newly identified nitrilases, nearly 60% showed less than 40% identity to any of the 34 previously characterized prokaryotic nitrilases, thus expanding the available catalog of nitrilases for synthetic biocatalysis.

Distribution of the nitrilase collection based on their sequence identity with the best sequence hits in the reference set. For the analysis, we used (A) the percent sequence identity; or (B) the percent positive substitutions, i.e., amino acids that are either identical or have similar properties based on the BLOSUM62 scores. Blue bars correspond to the 163 candidate enzymes, yellow bars to the 125 screening hits, and green bars to the 27 validated enzymes with the best activities.

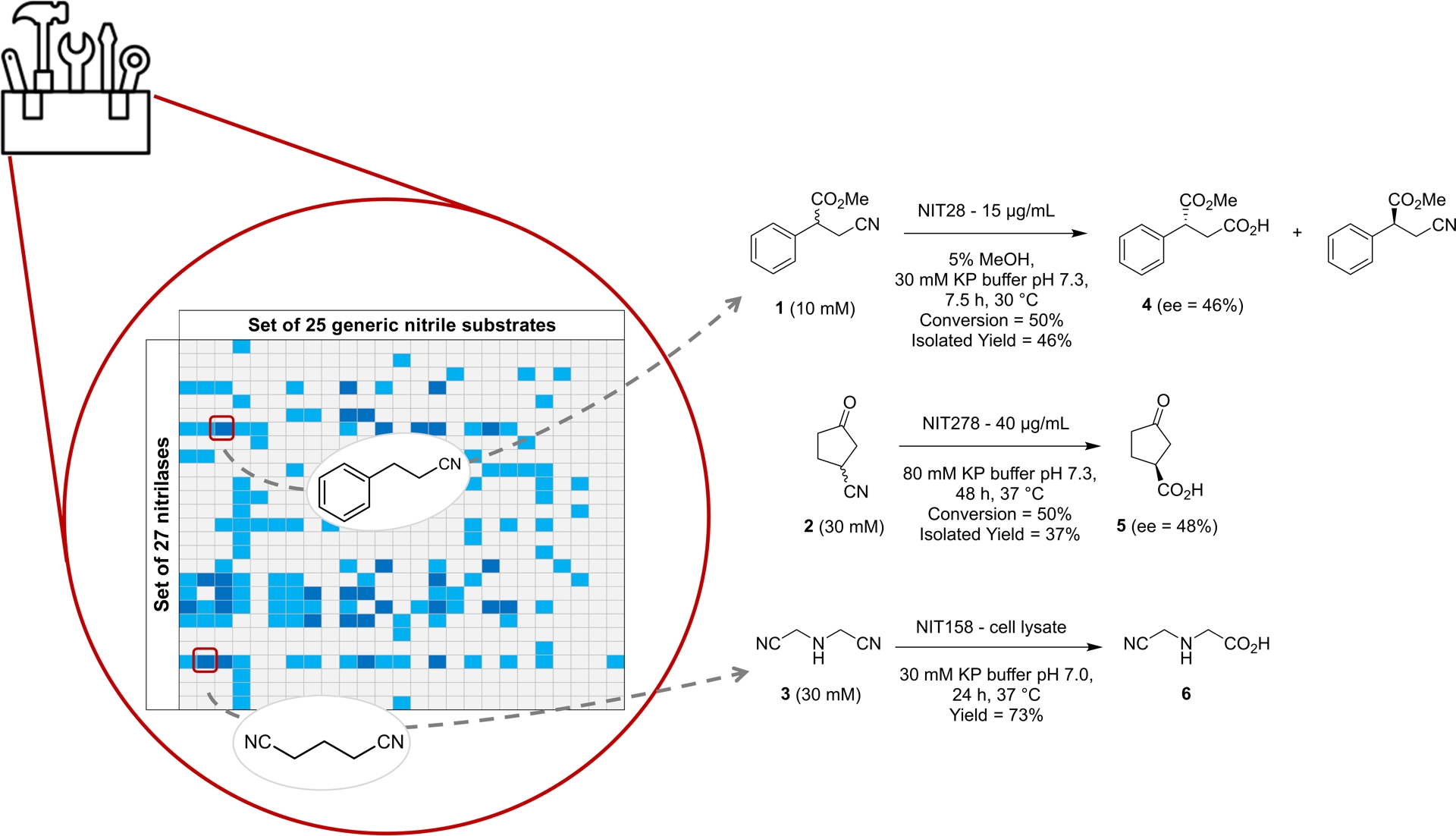

The screening revealed several enzymes with significant activity, forming a versatile toolkit of catalytic options. We used this toolbox to identify enzymes active toward specific synthons. We focused on enzymes exhibiting activity toward the generic substrate structurally related to targeted synthons in a second screening round on these more functionalized molecules frequently used in chemical synthesis. This approach yielded promising results: NIT28 from Sphingomonas wittichii (UniParc ID: UPI0000E98FFB), NIT278 from Syntrophobacter fumaroxidans (UniProtKB ID: A0LKP2), and NIT158 from Sphingomonas wittichii (UniParc ID: UPI0000E990F3) successfully converted 3-cyano-2-phenylpropanoate (1), 3-oxocyclopentanecarbonitrile (2), and iminodiacetonitrile (3) into (R)-3-methoxycarbonyl-3-phenylbutanoic acid (4) (ee = 46 ± 2%), (S)-3-oxocyclopentanecarboxylic acid (5) (ee = 48 ± 2%), and the monoacid 2-[(cyanomethyl)amino]acetic acid (6), respectively, with moderate to high yields, demonstrating substantial biocatalytic potential (Figure 3).

Genome-mined nitrilase toolbox for preparative scale hydrolysis of functionalized nitriles. The imbedded table illustrates results obtained with the set of purified enzymes where navy blue squares indicate high activities (more than 1 mM converted in 4 h) and light blue squares moderate activity (less than 1 mM converted in 4 h). Source: Figure adapted from Vergne-Vaxelaire et al. [17].

Through genome mining, we have been able to identify new nitrilases with a substrate range complementary to the initial reference set. Further analysis highlighted the distinct characteristics of these enzymes, such as their pH and solvent tolerance, along with their thermoactivity profiles. This work demonstrates that screening diverse representative enzymes across structurally varied substrates builds an enzyme toolbox that can be leveraged for further, more targeted applications in synthesis.

2.2. Example with the α-ketoacid-dependent dioxygenase activity

Another example employing this strategy is our exploration of α-ketoacid-dependent oxygenases (αKAOs), enzymes primarily known for catalyzing hydroxylation. We concentrated on bacterial αKAOs involved in hydroxylating side chains of free amino acids or peptide-bound amino acids in non-ribosomal peptide synthesis pathways. Hydroxylated amino acids are valuable chiral building blocks widely used in synthetic chemistry. Except for the production of hydroxyprolines which found applications in pharmaceutical and feed industries, the broader industrial use of αKAOs in biocatalytic processes remains limited, likely due to insufficient efficiency and a lack of comprehensive understanding of this enzyme family’s full potential. To address this gap, we undertook a genome-mining approach to identify new native dioxygenases with activity toward free amino acids and structurally related compounds.

A collection of candidate αKAOs was generated from an initial set of eleven experimentally validated enzymes. Using the established workflow described above, we obtained 274 candidate sequences after clustering. To expand the collection, we also included homologs containing InterPro motifs associated with the target activity (proline hydroxylase—IPR007803 and clavaminate synthase-like (CSL)—IPR014503), thus adding 56 enzymes representative of clusters with 80% identity or more. This brought the total to 331 candidates, of which 131 were successfully cloned with a His-tag and expressed in E. coli as previously described [19].

For a project aiming to capture the full diversity of biocatalysts for a specific transformation, it is essential to choose the substrates to encompass a wide range of chemical reactivities and structural constraints, minimizing the risk of overlooking potential activities.

To streamline the process, the fourty-six chosen substrates were organized into twelve pools. Each pool contained known substrates from the reference set and derivative targets, including non-natural amino acids, as well as amine and keto derivatives with aliphatic or aromatic chains, and aliphatic sulfates.

Dioxygenase activity was monitored using the GDH assay mentioned above, this time quantifying residual α-ketoglutarate, the αKAO cosubstrate. Enzyme hits were purified and tested on individual substrates, with product quantification by HPLC or GC-MS. This screening led to the identification of previously uncharacterized enzymes active on both known and novel substrates. Notably, three enzymes exhibited activity on l-lysine (7), with either C3 regioselectivity (KDO1 from Catenulispora acidiphila, UniProtKB ID: C7QJ42) or C4 regioselectivity (KDO2 from Chitinophaga pinensis, UniProtKB ID: C7PLM6; KDO3 from Flavobacterium johnsoniae, UniProtKB ID: A5FF23), and on l-ornithine (ODO from Catenulispora acidiphila, UniProtKB ID: C7Q942). Interestingly, KDO2 and KDO3 were the first αKAOs observed with C4 regioselectivity on a polar amino acid like lysine, later supplemented by homologs KDO4 and KDO5 (UniProtKB ID: G8T8D0 and UniProtKB ID: J3BZS6). Further study of ODO and KDO1,2,3 confirmed their total regio- and stereoselectivities. ODO achieved up to 68 and 50% conversion of l-ornithine and l-arginine into (3S)-3-hydroxy-l-ornithine and (3S)-3-hydroxy-l-arginine, respectively. KDO1 and KDO2,3 fully converted l-lysine 7 into (3S)-3-hydroxy-l-lysine (8) and (4R)-4-hydroxy-l-lysine, respectively. Moreover, sequential hydroxylation of l-lysine by KDO1 and KDO3 yielded (3R,4R)-3,4-dihydroxy-l-lysine (9), which was further transformed into the lactone (3R,4R,5R)-3-amino-5-(2-aminoethyl)-4-hydroxyoxolan-2-one, an interesting chiral scaffold for synthesis.

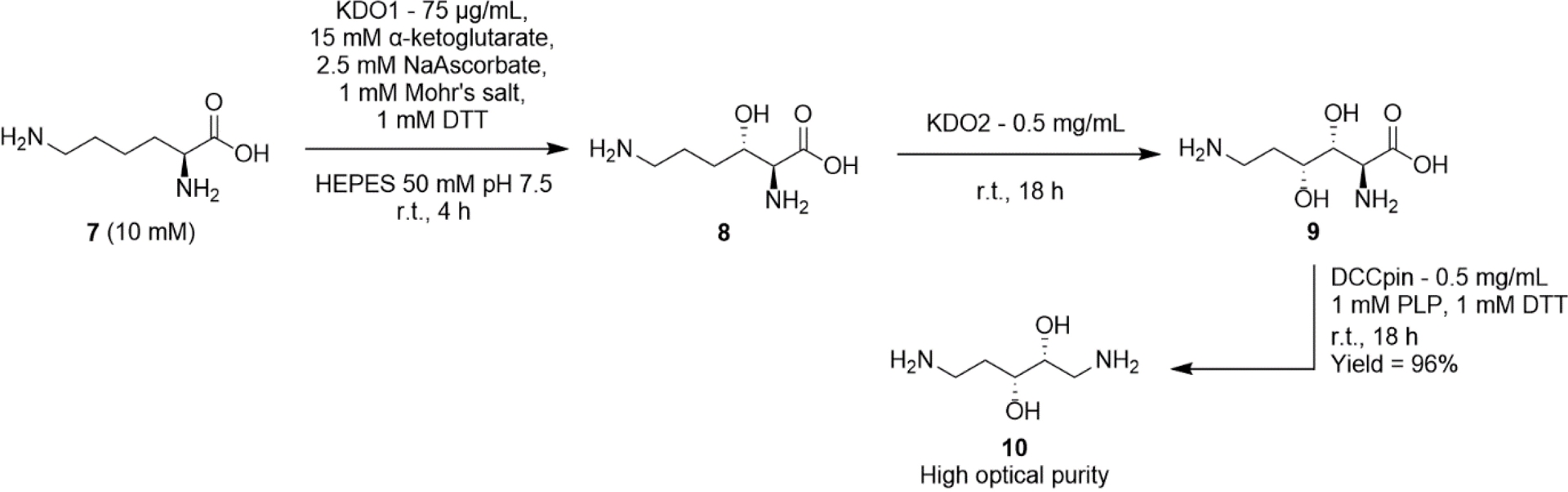

By coupling KDOs with PLP-dependent decarboxylases, we designed straightforward synthesis of chiral hydroxy amines from amino acids through two- or three-step one-pot cascade reactions. The decarboxylases were selected based on their genomic context and native substrates, specifically targeting metabolic diamines such as cadaverine. Notably, combining KDO1, KDO2, and DCCpin (a decarboxylase from Chitinophaga pinensis, UniProtKB ID: C7PLM7, genomic context of KDO2) in a three-step, one-pot synthesis led to the production of (2R,3R)-1,5-diaminopentane-2,3-diol (10) with high optical purity and 96% yield, starting from l-lysine 7 (Figure 4).

Preparative-scale dioxygenase-decarboxylase enzyme cascade yielding (2R,3R)-1,5-diaminopentane-2,3-diol (10) from l-lysine 7.

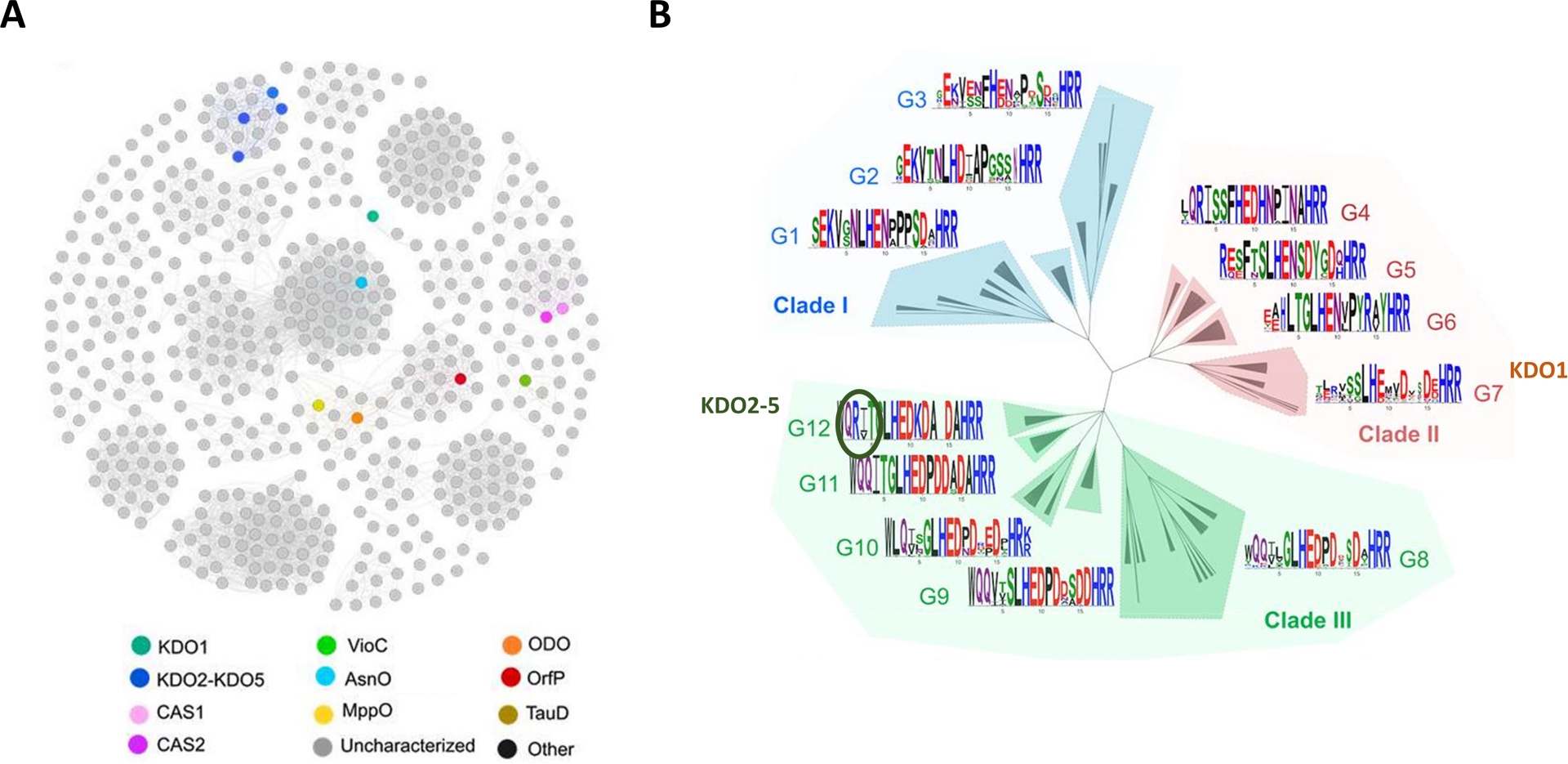

To understand the enzyme selectivity, we performed a structural and computational analysis of the enzymes. Sequence similarity network (SSN) analysis, which clusters closely related proteins, revealed that KDO2-5 homologs form a distinct group, clearly separate from other CSL dioxygenases, including KDO1 [20]. This classification aligns well with experimental findings (Figure 5A). Through genome mining, we have begun to identify and define subfamilies within this enzyme family, although many remain experimentally uncharacterized or potentially misannotated. This underscores the importance of combining in vitro screening with bioinformatic analysis to comprehensively map and harness enzymatic diversity.

Sequence and active site-structural diversity of the clavaminate synthase-like (CSL) family. (A) Sequence similarity network (SSN) of the CSL family (IPR014503) from the αKAOs superfamily. Nodes represent proteins and edges are the links between those proteins that have at least 50% sequence identity. Experimental data retrieved from Swissprot is mapped on the SSN with KDO1 colored in emerald green, KDO2-5 in dark blue and ODO in orange. The network was made with the EFI-EST tool and visualized with Gephi [21]. (B) Active site modeling and clustering (ASMC) hierarchical tree of the CSL family, encompassing 523 proteins grouped into three main clades (I, II, III). For each ASMC group (G1 to G12), a linear projection of the three-dimensional superposition of modeled and crystallographically resolved active sites is provided, via sequence logos illustrating residue conservation within each active site pocket of the ASMC group. A conserved arginine residue, specific to G12, which clusters the KDO2-5 homologs, is highlighted with a green circle marker. Source: Figure adapted from Bastard et al. [20] under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Combining sequence diversity to active site structural diversity is a key strategy to build solid hypotheses regarding enzyme mechanism, substrate selectivity, and regio- and stereoselectivity. In this regard, we further explored the diversity of the family via structural studies using the active site modeling and clustering (ASMC) method, thanks to the resolution of the crystal structures of KDO1 and KDO5 in complex with their ligands [22]. It clearly enables us to visualize the high amino acid conservation within some groups of this hierarchical tree of the family, key residues hypothesized from the solved structures. In this way, the C4 regioselectivity was explained by the presence of an arginine in a specific spatial position responsible for a salt bridge with the carboxylate group of the l-lysine substrate, and not found in C3-regioselective enzymes like KDO1 classified in another ASMC group (Figure 5B). A subpocket was also identified as responsible for the substrate specificity in the CSL family, stabilizing either hydrophobic or positively or negatively charged amino acid substrates depending on its surface charge and hydrophobicity. Extensive characterizations like that are especially useful to feed back into the genome mining process. Indeed, we can now look further into dioxygenases using genome mining reinforced with structure-based searches to look for new KDOs.

These two examples highlight the potential of genome-driven biodiversity screening, ranging from numerous hits for enzyme families with wide substrate promiscuity, such as nitrilases, to a more restricted set of hits for enzyme families tested against specific substrates and exhibiting high specificity. As databases of enzyme sequences, including many uncharacterized entries, continue to expand, genome mining emerges as an indispensable tool for uncovering this latent potential. It delivers crucial findings that enhance our understanding of sequence diversity and enrich the repertoire of biocatalysts available for biotransformations in synthetic chemistry.

3. Genome mining to divert an enzyme activity toward an un-natural synthetic reaction: a use case with coenzyme A (CoA) ligases

The transformations catalyzed by native enzymes can inspire new synthetic strategies for desirable chemical steps. One approach involves partially leveraging a native enzyme system to benefit from only the mechanistic steps useful for the targeted transformation. A notable example, reported in 2017, is the synthesis of amides using carboxylic acid reductases (CARs), which naturally catalyze the reduction of carboxylic acids to aldehydes. This reaction proceeds through a sequence involving the formation of acyl adenylate and enzyme-thioester intermediates, followed by an NADPH-dependent reduction to aldehyde. By adding a free amine to the reaction mixture, these intermediates can instead be intercepted by this nucleophile, producing amides rather than aldehydes [23]. Further enzyme engineering allowed the optimization of this promising method for enzymatic amide synthesis [24].

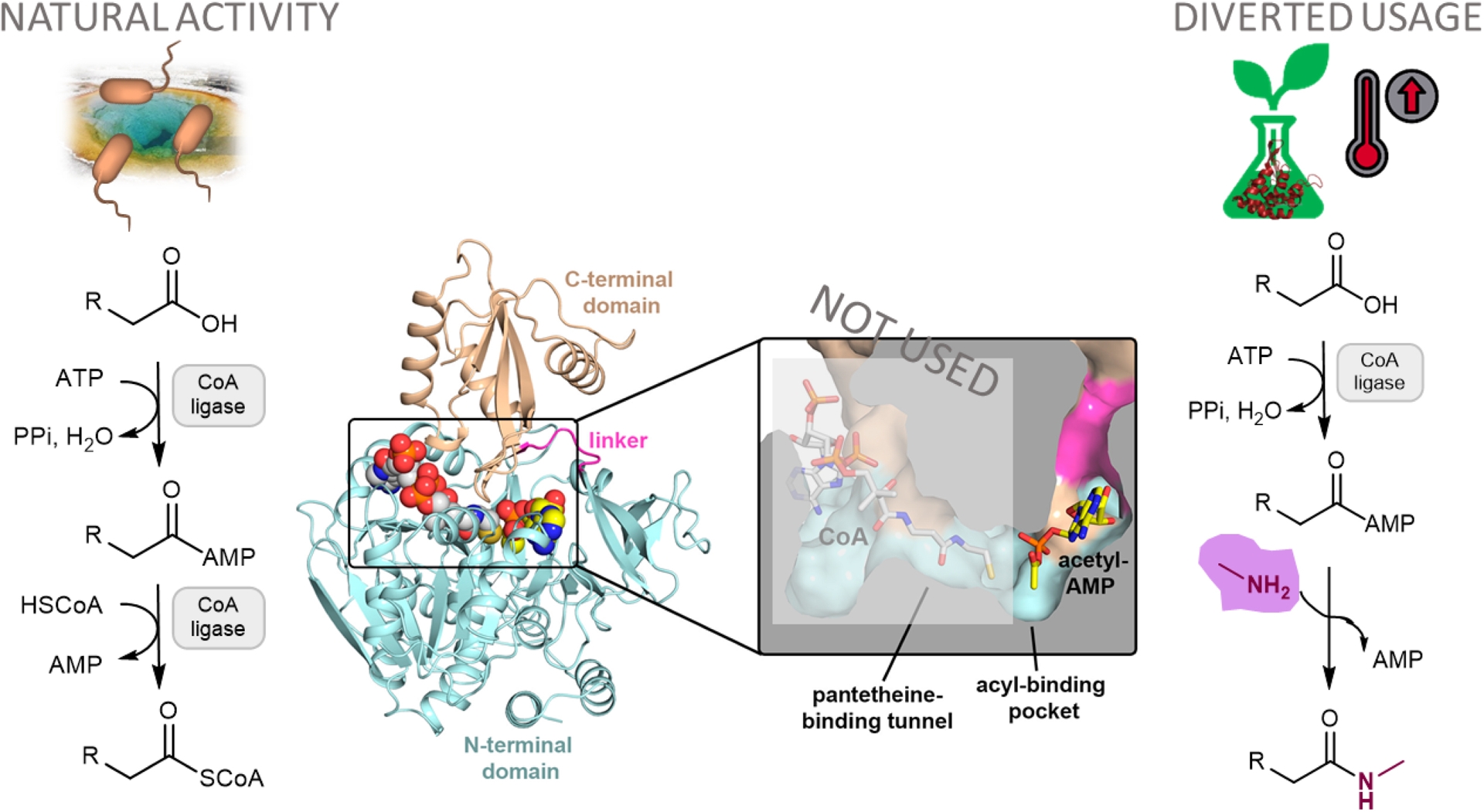

Following the same philosophy, we aimed to utilize other members of the adenylate-forming enzyme superfamily to achieve efficient amide synthesis. Amides are crucial precursors for fine chemical and pharmaceutical production [26]. By coupling bacterial coenzyme A (CoA) ligases, for the activation of carboxylic acids, with amines, we developed a chemoenzymatic route for diverse amides [27]. CoA ligases typically catalyze the ATP-dependent acyl/aroyl-CoA thioester formation from carboxylic acids in two steps: adenylation with ATP followed by thioesterification in the presence of CoA. To enhance process efficiency, we made the adenylate intermediate the direct target of amine addition, avoiding the costly use of CoA for thioesterification. To drive the nucleophilic attack, we increased the reaction temperature to 60 °C. We selected CoA ligases from thermophilic organisms to ensure stability at this temperature (Figure 6). This approach offers significant advantages over the conventional chemical synthesis of amides, which typically relies on activating carboxylic acids with reagents of low atom economy, such as carbodiimides, oxalyl or thionyl chlorides, or 1,1′-carbonyldiimidazole [28].

Synthesis of N-methylalkylamides by biocatalysis with CoA ligases diverted from their ATP-dependent acyl-CoA thioesterification natural activity. Source: Figure adapted from Capra et al. [25] under the CC-BY license.

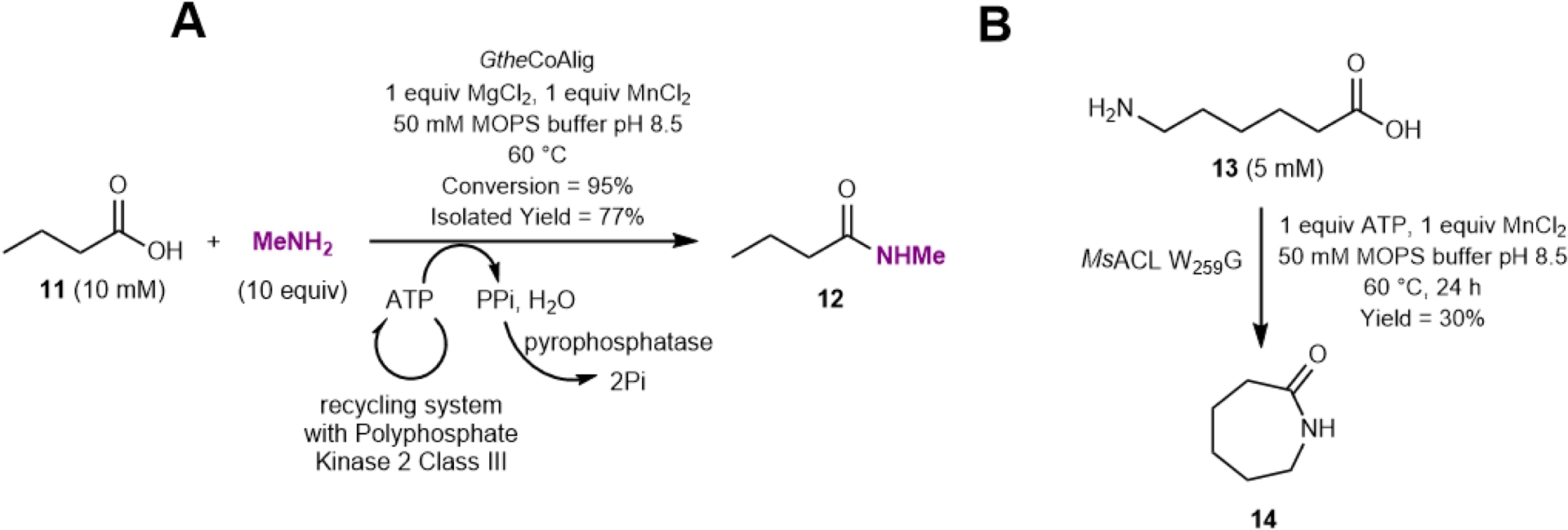

As a proof of concept, we focused on synthesizing N-methylbutyramide (12) from butyric acid (11) [27]. Based on literature, we selected carboxylic acid CoA ligases (ACLs) reported as active on small carboxylic acids and expressed by thermophilic organisms: MsACL (UniProtKB ID: A4YDT1) and MsedACL2 (UniProtKB ID: A4YDR9) from Metallosphaera sedula, GtheACL (UniProtKB ID: A4INB3) from Geobacillus thermodenitrificans, and StokACL (UniProtKB ID: Q973W5) from Sulfolobus tokodaii. To address ATP costs, an enzymatic ATP regeneration system was implemented, using a thermally stable polyphosphate kinase 2 (class III) to convert the released AMP directly to ATP, with polyphosphate (PolyPn) as the phosphate donor. After 24 h at 65 °C in MOPS buffer (pH 8.5), with 0.02 mg/mL DgeoPPK2-III from Deinococcus geothermalis (UniProtKB ID: Q1W43), 0.002 mg/mL PhPPase from Pyrococcus horikoshii (UniProtKB ID: O59570), 5 mM butyric acid, 0.5 mM ATP, and 50 equiv. of methylamine, the conversion rate to N-methylbutyrylamide reached 55 to over 99% across all four CoA ligases.

Interestingly, MsACL also accepts a range of carboxylic acids, primarily short, linear ones, but activity was also observed with 5-oxo-hexanoic acid. Activity levels with propionic to pentanoic acids (761–1514 mU/mg of purified enzyme) exceeded those for phenyl derivatives (e.g., 3-phenylpropanoic acid) or longer chains (e.g., decanoic acid). Notably, GtheACL demonstrated the highest activity (3.2 U/mg for butyric and pentanoic acid), although its substrate scope was narrower, with no activity detected for decanoic acid or 3-phenylpropanoic acid. A preparative 10 mL-scale reaction using a reduced methylamine quantity (10 equiv.) and 10 mM butyric acid confirmed the feasibility of this approach for synthetic applications (Figure 7) [27].

Preparative biocatalytic synthesis of (A) N-methylbutyramide (12) by the thermophilic CoA ligase from Geobacillus thermodenitrificans and (B) seven-membered lactam 14 from 6-aminohexanoic acid (13) by the MsACL (CoA ligase from Metallosphaera sedula) enzyme variant.

As with CARs, one of the advantages of this approach is the diversity of amides that can be obtained, since attack by the nucleophilic amine is not catalyzed by the enzyme. A priori, all amines or other nucleophiles are considered, the limitation remaining their nucleophilicity and solubility under CoA ligase reaction conditions. As the critical step from a sustainability and energetic point of view is the acid activation step and not the addition of the amine, this strategy constitutes an alternative to conventional chemistry. Recently, this advantage was harnessed in the hybrid synthesis of 5-aminomethyl-2-furancarboxylic acid (AMFC)-derived amides from alcohols, combining supported gold nanoparticles with these CoA ligases [29]. It is worth noting that another promising biocatalytic approach for amide synthesis involves catalysis by amide bond synthetases, a rare subclass within the ANL superfamily, which also includes carboxylic acid-CoA ligase [30]. In this case, the enzyme catalyzes the entire transformation [31].

Building on these successful results, we further diverted the native reaction by looking for CoA ligases active on ω-amino acids to enable intramolecular lactam formation [25]. Lactams are valuable compounds, particularly as precursors to polymers like ε-caprolactam, essential for nylon production. Such enzymes would catalyze the formation of ω-amino acyl adenylates which, for five- to seven-membered chains, could then undergo spontaneous intramolecular aminolysis of the phosphoester bond. This reaction would lead to the formation of five- to seven-membered lactams, specifically γ-butyrolactam, δ-valerolactam, and ε-caprolactam 14, respectively. To do so, we improved the acyl-binding pockets of the promiscuous propionate-CoA ligase MsACL, also reported to be active toward the ω-functionalized substrate 4-hydroxybutyric acid, by structure-guided protein engineering [32]. The thermoactivity and stability of this enzyme is all the more important for the desired intramolecular aminolysis reaction step. The three-dimensional structure of MsACL in a thioesterification state with bound acetyl-AMP and CoA was determined in collaboration with the University of Groningen, providing insight into the key residues shaping the acyl-binding pocket. Structure analysis, supplemented with docking and mutant design, revealed the interest of mutating the position W259 in MsACL located at the “pocket floor” into a smaller residue to generate a deeper pocket suitable for ω-amino acid stabilization. Docking experiments of the intermediates 5-aminopentanoyl-AMP and 6-aminohexanoyl-AMP into the W259G mutated pocket resulted in low energy binding poses with formation of hydrogen bonds and van der Waals interactions with neighboring residues (V238 and F350), not obtained in the wild-type enzyme. Combined with mutations at these latter positions to enhance interactions with the ω-amino group of the substrate, purified mutants generated by directed mutagenesis and expression in E. coli were tested for the formation of six- and seven-membered lactams. The variant W259G/V238T/F350V gave rise to the highest analytical yield in δ-valerolactam (26%), while none of the tested double or triple mutants provided higher yield in ε-caprolactam 14 than the W259G variant (30%). For the formation of γ-butyrolactam from 4-aminobutyric acid, the best analytical yield was obtained with the wild-type enzyme (63% yield) as expected from the in silico analysis. It is worth noting that the main beneficial mutation W259G also induced significantly higher activity for the intermolecular amide formation with various longer carboxylic acids up to eleven-carbon chain length.

This example highlights the benefit of drawing inspiration from nature by repurposing its natural functions to support advancements in the chemical industry, with the understanding that revisiting Nature often provides further insights. For lactam-forming CoA ligases, ongoing efforts are focused on identifying candidates within biodiversity using the genomic approach outlined in Section 2.1, complemented by insights gained from X-ray structural data and protein engineering of MsACL.

4. Genome mining for identification of a new family of biocatalysts: a use case with amine dehydrogenases (AmDHs)

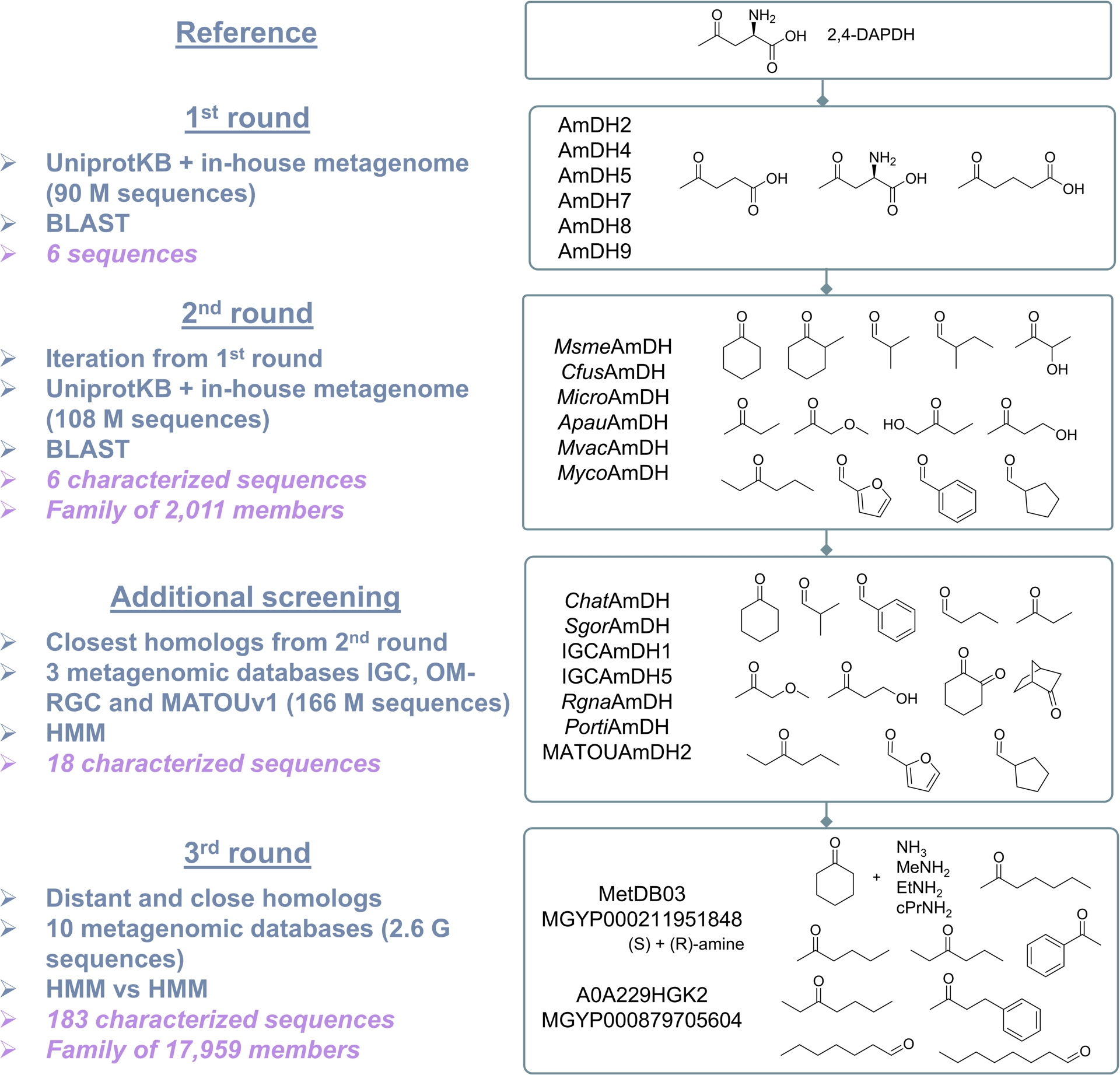

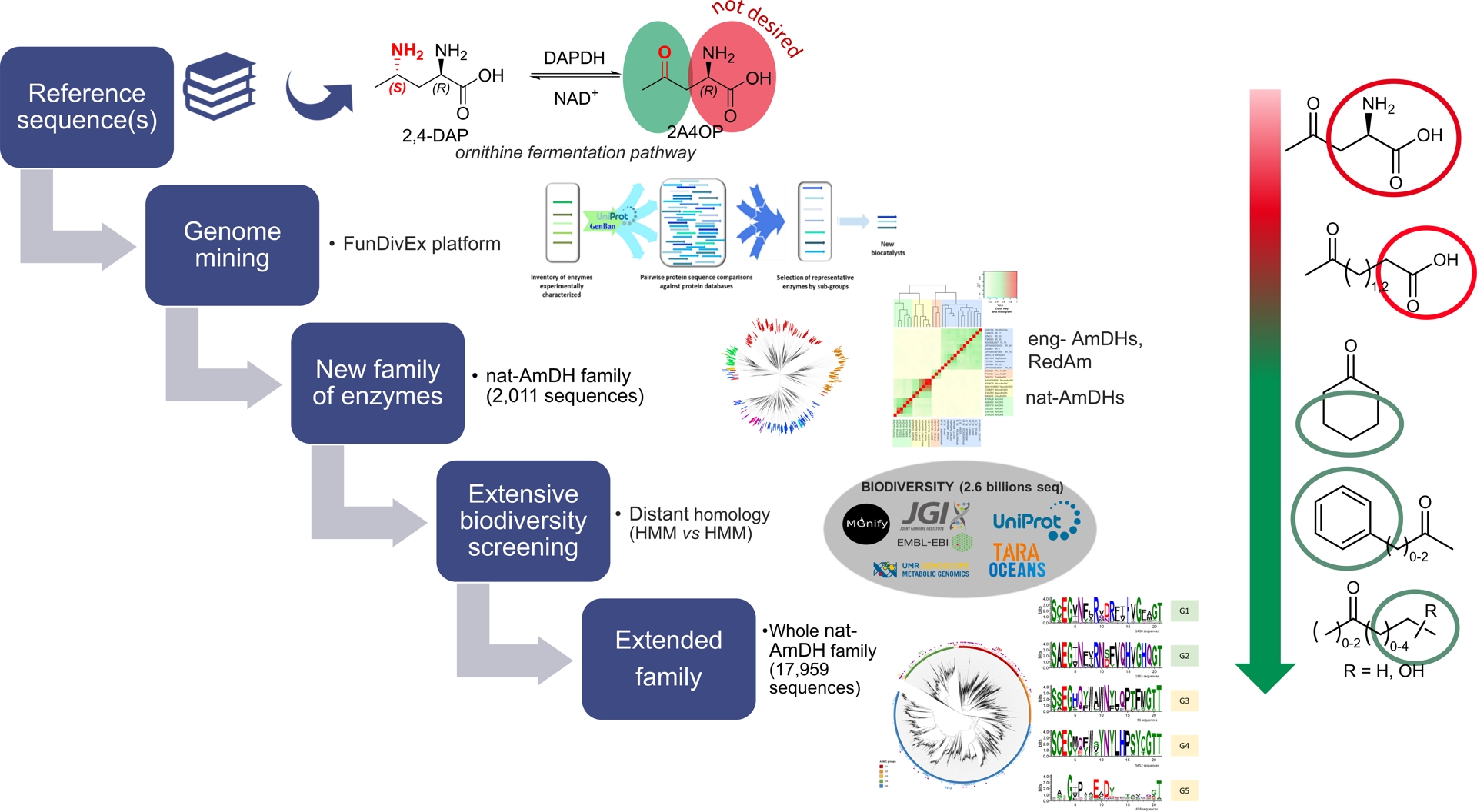

In some cases, for a given biocatalyzed transformation, no naturally occurring enzymes capable of catalyzing the reaction are known; only engineered enzymes derived from those catalyzing different reactions can be reported in the literature. This was the case in 2015 for the reductive amination of carbonyl compounds to synthesize optically active amines, where NAD(P)-dependent enzymes from Streptomyces virginiae were documented, but their corresponding protein sequences had not been identified. Given the potential of this biocatalytic route as an alternative to conventional reductive amination for optically active amine synthesis, we sought to identify this activity across biological diversity. However, the selection of reference protein sequences to find homologs proved more complex than for previously studied activities (see above), as no sequences for this specific activity were available. To address this, we mined metabolic databases to identify reactions that convert ketones to amines using ammonia and NAD(P)H, specifically excluding α/β-amino acid dehydrogenases from our search criteria. Homologous sequences of (2R,4S)-2,4-diaminopentanoate dehydrogenase (2,4-DAPDH), found in ornithine-fermenting bacteria, were selected via the FunDivEx platform using the previously described pipeline [33]. The selected hits, heterologously produced in E. coli, including AmDH4 and others, were active toward the native substrate lacking an amino group at the α-position but retaining the necessary carboxylic acid (i.e., 4-oxopentanoic acid). These hits were used in a subsequent iteration, ultimately leading to the discovery of the first gene sequences encoding native AmDHs that catalyze amination of ketones without requiring any carboxylic acid group (specifically, CfusAmDH and MsmeAmDH). Interestingly, these sequences were evolutionarily distinct from both engineered AmDHs (eng-AmDHs) and imine reductases (IREDs), including reductive aminases (RedAms), other NAD(P)-dependent enzymes that typically utilize primary amines rather than ammonia. The sequence space for this novel activity was further explored through a sequence similarity network constructed from 5313 protein homologs of AmDH4, CfusAmDH, and MsmeAmDH, limited to sequences found in the UniProtKB database and an in-house metagenomic dataset [34].

A search limited to the closest homologs of previously identified native AmDHs (nat-AmDHs) in metagenomic databases specific to marine environments (OM-RGC and MATOUv1) and human microbiomes (Integrated Gene Catalog) confirmed the presence of this activity across multiple biomes [35]. Recently, we proposed an innovative approach leveraging advances in bioinformatics to gain a more detailed understanding of the entire family across biodiversity. This involved an extensive in silico screening of billions of sequences, covering a substantial portion of publicly available metagenomic data [36]. We designed an efficient bioinformatic workflow to capture remote homologs—proteins with similar structures and functions that exhibit low sequence similarity and are challenging to detect using traditional sequence-to-sequence or sequence-to-profile methods. This approach involved screening Hidden Markov Models (HMMs) profiles of an expanded nat-AmDH family against HMM profiles of NAD(P)-dependent enzymes built within a vast dataset of 2.6 billion sequences from ten genomic and metagenomic sequence databases (2020 update). While this strategy has been applied within the metabolic biology community to annotate proteins with unknown functions, it has yet to be widely adopted in the biocatalysis research community. This approach expanded the nat-AmDH family from 2011 to 17,959 sequences, with no additional phylogenetic or structural groups identified, indicating that we captured the full enzymatic diversity for this transformation within biodiversity. Notably, we combined this extensive in silico enzyme capture with in vitro experiments to validate the function of selected representatives and to uncover nat-AmDHs with previously unreported substrate scopes. The previously straightforward search within the UniProtKB database revealed (S)-stereoselective nat-AmDHs active on carbonyl compounds limited to short aliphatic aldehydes and methyl ketones (five carbon atoms or less), favoring ammonia over primary amines. In contrast, this large-scale metagenomic screening identified members active on bulkier carbonyls and ethyl ketones, capable of utilizing methylamine, cyclopropylamine, and displaying increased (R)-selectivity, along with close homologs of previously identified nat-AmDHs (Figure 8).

Different screenings carried out to identify native amine dehydrogenases (nat-AmDHs). Substrates of some characterized enzymes are drawn (list not exhaustive).

With the crystallographic structures of AmDH4, CfusAmDH, MsmeAmDH, and MATOUAmDH2, we conducted further analysis using the Active Site Modeling and Clustering (ASMC) method [34, 37]. This resulted in a hierarchical tree for the nat-AmDH family, organized into five groups (G1–G5) based on active site residue patterns and frequency. Groups G3 and G4 include AmDHs like MsmeAmDH and its homologs, which are active on simple ketones and aldehydes, while the more distant G2 contains AmDH4-type enzymes, active on γ-keto acids and 2,4-diaminopentanoate. It should be noted that the reductive amination activity of G3–G4 members toward the substrates tested may not be the metabolic function that has yet to be elucidated. Enzymes in G1 and G5 remain functionally undefined. This classification provides a valuable tool for identifying unusual members by visualizing both conserved and divergent residues at specific 3D positions within the active site. Coupled with docking experiments, this method allows clearer differentiation of active sites suited to more hindered or uniquely functionalized substrates.

Notably, understanding the diversity of residues at specific spatial positions is invaluable to design active site variants. Considering naturally occurring diversity enables the prediction of impactful, viable mutations within the protein context, enhancing the efficiency of protein engineering efforts. This approach has proven beneficial in our work on CfusAmDH and nine additional nat-AmDHs, where biodiversity mining and protein engineering guided the development of variants capable of catalyzing the amination of sterically hindered n-alkyl aldehydes and n-alkyl ketones from C6 to C9 [38].

Some members of this family were further examined for enzyme kinetics, stability, and biocatalytic potential. Their kcat values ranged from 0.1 to 10 s−1, with KM values for carbonyl compounds between 0.5 and 100 mM. Similar to eng-AmDHs, the KM for NH3 was high (100–400 mM), while the preferred nicotinamide cofactor had a KM between 10 and 50 μM [34, 35]. Although each characterized AmDH showed a cofactor preference, most favored NADP; however, certain substrate/enzyme couples displayed preference for NAD. Structural analysis pinpointed key residues responsible for this specificity [36]. Interestingly, some nat-AmDHs functioned efficiently as ketoreductases in the absence of an ammonia source; they exhibited minimal activity in the reverse reaction for alcohol or amine oxidation [39]. Stability studies included assessments of thermal tolerance and buffer compatibility. For instance, AmDH4 from Petrotoga mobilis, a thermophilic bacterium, proved exceptionally stable with a half-life of 65 h at 60 °C and retained 90% of its initial activity after 14 days at 30 °C [33].

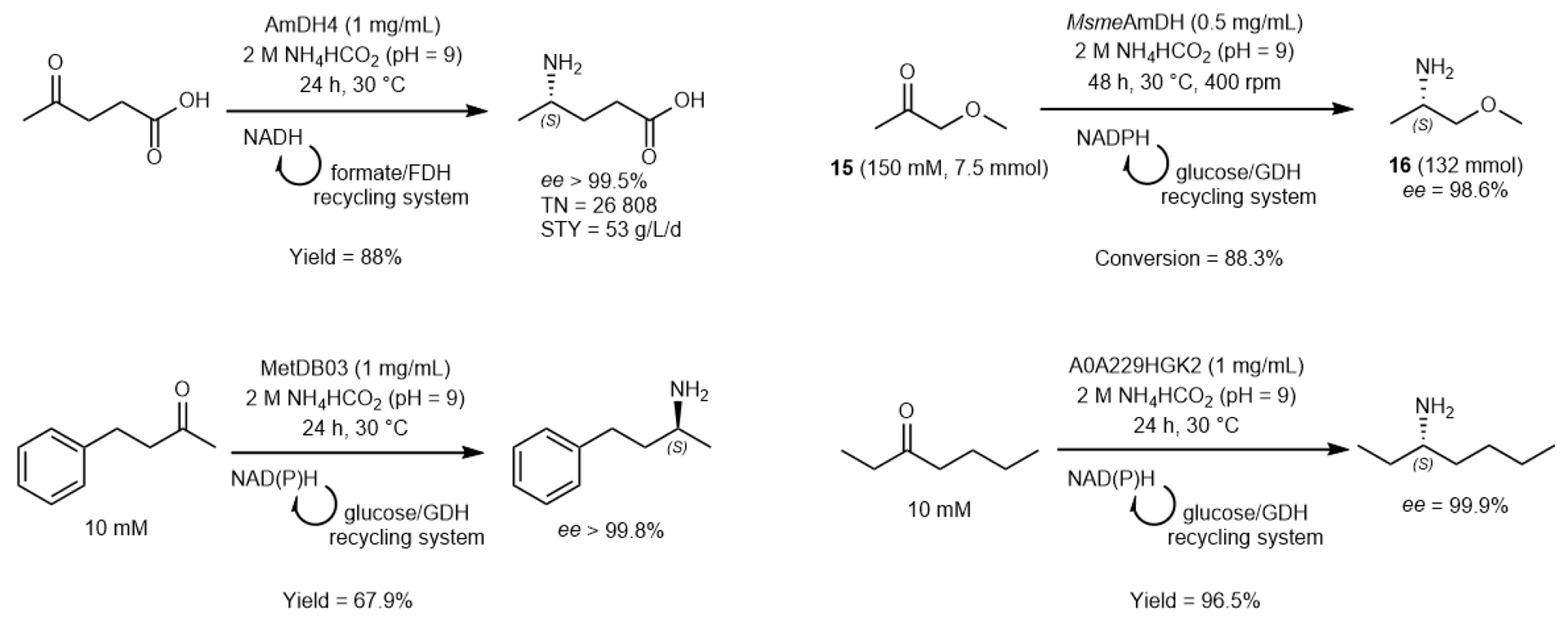

Regarding conversion yields and productivity when a cofactor recycling system was implemented, moderate to high conversions were obtained with high enantiomeric excess of the resulting amines (ee from 98 to over 99.9%) for most of them. In the case of 1-methoxypropan-2-one (15), a semi-preparative synthesis at 7.5 mmol scale (150 mM) was performed with 0.5 mg/mL of MsmeAmDH to access, with 88.3% yield and 98.6% ee, to the (S)-MOIPA 16, a key chiral element within the Outlook® herbicide (BASF) (Figure 9) [40].

Example of biocatalytic reactions performed with native amine dehydrogenases (nat-AmDHs). FDH = formate dehydrogenase, GDH = glucose dehydrogenase; TN = Turnover Number; STY = Space Time Yield.

The kinetics as well as the stability and biocatalytic potential can now be improved by protein engineering and/or directed evolution, these enzymes still being native ones heterologously overexpressed in E. coli. The success of some preliminary site-directed mutations carried out on some of them to modify their substrate range makes us confident that modification of these enzymes will lead to soluble and effective enzymes.

This iterative strategy for identifying new enzyme groups suitable for biocatalysis is highly effective and broadly applicable to other enzyme families that remain underexplored in biocatalysis (Figure 10). Searching for distant homologs within the vast pool of publicly available metagenomic databases is a key approach for efficiently and comprehensively exploring what Nature offers for biocatalytic applications, as demonstrated in this study with the exploration of reductive amination activity.

Iterative strategy to decipher a new group of enzymes for biocatalysis. Example with the identification of the native amine dehydrogenase (nat-AmDH) family. Source: Figure adapted from Zaparucha et al. [15], Mayol et al. [34], Caparco et al. [35], and Elisee et al. [36], the last under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

5. Conclusion and perspectives

Through these examples, we highlight the benefits of genome mining for expanding the enzyme toolbox for synthetic applications. Analyzing sequence diversity provides a crucial foundation, supporting not only targeted searches within existing and upcoming metagenomic datasets, but also the engineering of customized enzymes tailored to specific industrial needs. This approach is bolstered by a broad array of emerging methods for generating mutant libraries, allowing researchers to explore sequence diversity beyond what Nature alone offers [41]. Biocatalysis is increasingly driven by advanced bioinformatics workflows, which are essential for addressing the demands of sustainable chemistry with speed and precision. Machine learning and artificial intelligence are becoming pivotal in analyzing sequence diversity and predicting protein structures [42, 43, 44]. When integrated with innovations in automation and high-throughput screening, these technologies significantly enhance our capacity to discover, modify, and design enzymes with tailored functions.

Although labor-intensive, harnessing native enzyme diversity for biocatalysis is essential and promises significant long-term benefits, especially with the implementation of robust databases and standardized data practices. Initiatives like RHEA, EnzChemRED, EnzymeML, SABIO-RK must operate within a user-friendly findable, accessible, interoperable, reusable (FAIR) environment to encourage widespread adoption [45, 46, 47, 48, 49]. By integrating these tools into research workflows, the full potential of genome mining for synthetic applications can be unlocked, driving significant advancements in biocatalysis.

Declaration of interests

The authors do not work for, advise, own shares in, or receive funds from any organization that could benefit from this article, and have declared no affiliations other than their research organizations.

Funding

Part of the work described in this mini-review was supported by the Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR) through the MODAMDH (ANR-19-CE07-0007) and ALADIN (ANR-21-ESRE-0021) projects, and by Commissariat à l’énergie atomique et aux énergies alternatives (CEA), the CNRS and the University of Evry Paris-Saclay.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Jean-Louis Petit for input in this mini-review and all the authors of the articles of the UMR8030 “Genomic Metabolics” research unit at Genoscope described in detail in this mini-review.

CC-BY 4.0

CC-BY 4.0