1. Introduction

Olefinic block copolymers (OBCs) is a general description for di- or multiblock copolymers composed of distinct polyolefin segments [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16]. For example, OBCs can be stereoblock copolymers [4], or they can consist of different semicrystalline blocks such as polyethylene (PE) and isotactic polypropylene (iPP) [5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11], but the OBCs attracting the most interest are those composed of low glass transition temperature (Tg) soft blocks and high Tg or high melting temperature (Tm) hard blocks [12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17]. Depending on the proportion of hard and soft segments, typically polyolefin plastomers (POPs) or elastomers (POEs) are obtained. The major difference between OBCs and corresponding random copolymers lies in the fact that, for the same crystallinity, the Tm and hence the heat deflection temperature of OBCs is considerably higher. As a result, these materials have a wider service temperature window and consequently a much better elastic recovery and creep resistance at ambient temperature than random copolymers having the same crystallinity [18, 19, 20, 21]. There are various ways to produce OBCs. Although not economically viable, the most straightforward approach toward OBCs consists in using a living catalyst system under changing feed conditions [2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 14]. With the development of coordinative chain transfer polymerization (CCTP) [22, 23, 24], a pseudo-living polymerization process accompanied by reversible chain transfer, the commercial synthesis of OBCs has come within reach. Using CCTP, OBC’s can be produced either using two different catalysts (Dow Chemical’s chain shuttling polymerization) [3, 4, 11, 12] or employing changing feed conditions [13, 15, 17]. As an example, ethylene/α-olefin (i.e., propylene, 1-octene)-based OBCs have been produced using CCTP on commercial scale by Dow Chemical under the tradenames Infuse™ and Intune™.

As the upper service temperature of thermoplastic elastomers is governed by the material’s Tm or high Tg, even OBCs containing hard segments of polyethylene and polypropylene have their thermal limitations. OBCs based on high-melting polyolefin blocks, such as poly(4-methyl-1-pentene) (P4M1P, having a Tm above 250 °C), would be desirable as such thermoplastic elastomers could compete with thermoplastic polyurethanes, silicones, and fluorocarbon elastomers in various temperature-demanding applications.

Whereas ethylene/α-olefin OBCs, having ethylene-rich crystallizable blocks, can be prepared using chain shuttling polymerization, ethylene/α-olefins, having crystallizable poly(α-olefin) sequences, such as P4M1P, cannot be synthesized by this approach as the ethylene/α-olefin reactivity ratio is typically considerably larger than one. To produce the desired block copolymers using chain shuttling polymerization would require a catalyst that prefers α-olefins such as 4-methyl-1-pentene (4M1P) over ethylene, which is very unlikely to find. Yet, the random copolymerization of ethylene and 4M1P does not necessarily give statistical random microstructures. Depending on the catalyst structure, poly(ethylene-co-4M1P)s with blocky microstructures have been obtained, though the sequence length was typically too short to obtain elastomeric properties [25, 26, 27]. Elastomeric multiblock copolymers consisting of segmented high-melting crystallizable P4M1P and amorphous or low-crystalline poly(ethylene-co-4M1P) blocks could potentially be produced using sequential feed under CCTP conditions.

With the final objective in mind of finding a catalytic system that could produce OBCs composed of high-Tm hard and low-Tg soft blocks, the CCTP behavior of three selected catalysts regarding 4M1P was studied. To evaluate the effect of steric hindrance on the CCTP behavior of the catalysts and the occurrence of competitive β-H transfer side reaction, comparative experiments using non-branched monomer 1-octene were used as benchmark.

2. Results and discussion

To form multiblock copolymers using CCTP, conditions must be found under which the polymerization proceeds in a highly controlled fashion. β-Hydrogen transfer or related chain termination processes should be reduced to a minimum and the catalyst system should undergo fast and reversible chain transfer to the chain transfer agent (CTA) such that a pseudo-living polymerization process is obtained. Such conditions not only depend on the catalyst applied, but also on the type of monomer used [28, 29].

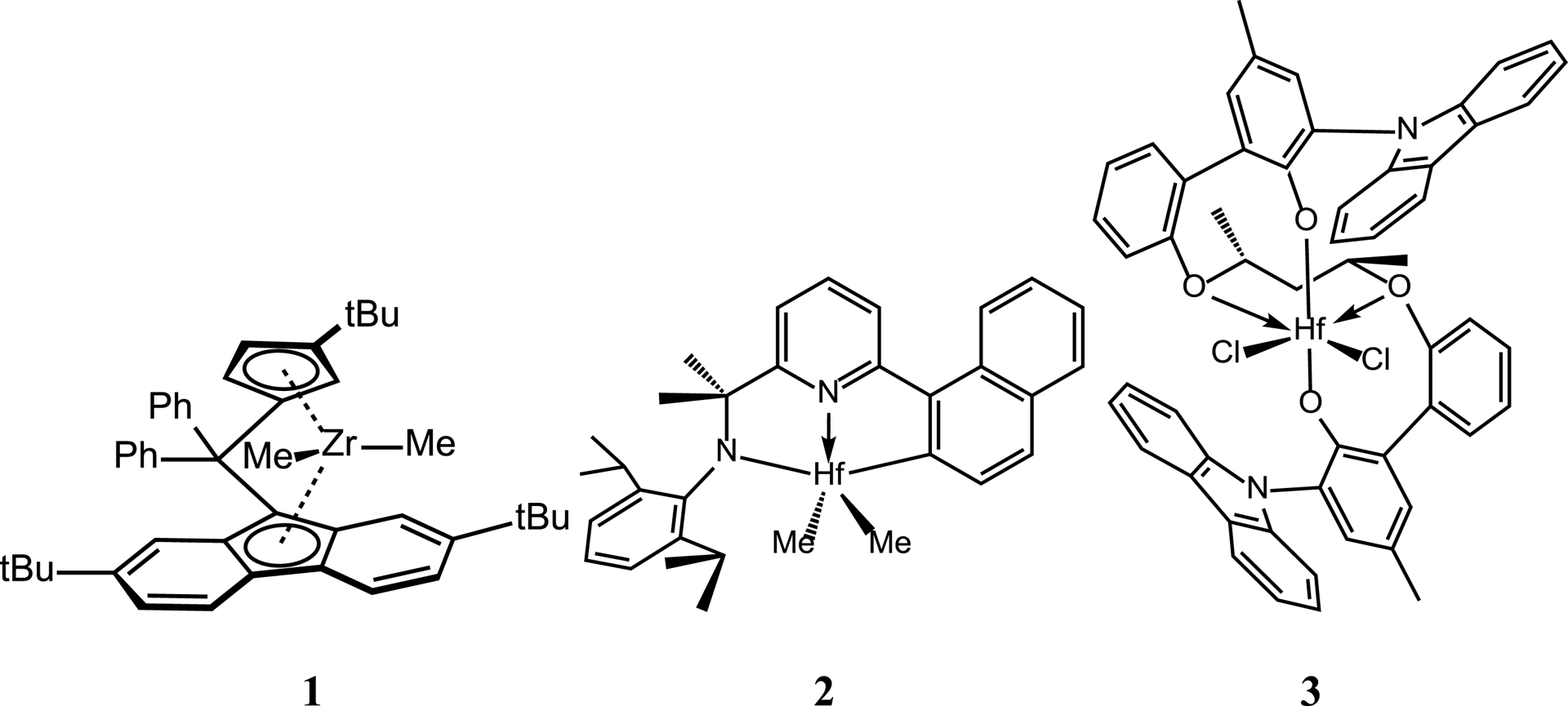

Based on their potential as described in literature, the following three catalysts have been selected for the polymerization of 4M1P and 1-octene under CCTP conditions: (1) a zirconocene: [Ph2C(3-tBu-Cp)(2,7-tBu2-Flu)]ZrMe2, (2) a pyridylamido hafnium system: [1-C10H6-5-(CMe2-2,6-iPr2-C6H3)-C6H3N]HfMe2, and (3) a bis(phenolate)diether hafnium system: {CH2[CH(Me)O-C6H4-2-(2-NC12H8)-4-Me-C6H2O]2}HfCl2 (Figure 1). Complex 1 was found to give high-molecular-weight P4M1P [30], and this type of catalyst is known to undergo chain transfer with diethyl zinc (DEZ) as CTA [31]. It was reported that 2 is able to produce PE/PP multiblock copolymers in a living fashion under sequential feed conditions and this type of catalyst—albeit with a slightly different ligand structure—has been used commercially to produce ethylene-based OBCs [8, 12, 13]. In addition, this catalyst family is also known to incorporate sterically hindered monomers like 4M1P, 3-methyl-1-butene, and vinyl cyclohexane [32]. Finally, the third catalyst (3) has shown excellent higher α-olefin incorporation abilities and has also been applied in the production of ethylene-based OBCs [33, 34, 35].

Structures of the catalyst precursors used [Ph2C(3-tBu-Cp)(2,7-tBu2Flu)]ZrMe2 (1), [1-C10H6-5-(CMe2-2,6-iPr2-C6H3)-C6H3N]HfMe2 (2) and {CH2[CH(Me)O-C6H4-2-(2-NC12H8)-4-Me-C6H2O]2}HfCl2 (3).

2.1. Cyclopentadienyl-fluorenyl zirconocene (1)

The ansa-zirconocene complex [Ph2C(3-tBu-Cp)(2,7-tBu2Flu)]ZrMe2 (1; Figure 1), in combination with methylaluminoxane (MAO) as activator, is known to polymerize higher α-olefins including 4M1P to high-molecular-weight products. This incited us to evaluate its potential for the polymerization of 4M1P under CCTP conditions to obtain a pseudo-living process in the presence of DEZ as CTA. The influence of the steric hindrance during the polymerization was studied by comparing the results of 4M1P and 1-octene polymerizations performed under similar conditions.

The initial 4M1P polymerizations performed (Table S1) demonstrated that 1 activated with MAO indeed generates an active catalyst for the polymerization of 4M1P and the activity increases with the presence of increasing amounts of DEZ (Figure S1A). The high-temperature size-exclusion chromatography (HT-SEC) analyses of the polymer samples show a dramatic effect of the increasing amounts of DEZ on the polymer’s molecular weight: it drops from 63 kDa in the absence of DEZ to only 4 kDa for a Zn:Zr ratio of 200. Although the decrease in the polydispersity (ÐM) from 2.4 to 1.8 was limited, a ÐM < 2 and a rough estimation of kCT/kCG around 1.5 (Figure S2) [36] indicate that the chain transfer (kCT) and chain growth (kCG) rate constants are of the same order of magnitude [37]. As the molecular weight did not increase with increasing polymerization time (Figure S1B), chain transfer is most likely quasi-irreversible, meaning that the reversible exchange of β-branched polymeryls between catalyst and CTA is considerably slower than the exchange of the initial ethyl group of DEZ [28].

1-Octene polymerization with 1/MAO(/DEZ) at 80 °C

| Exp. | DEZ eq. Zr | t (min) | Yield (g) | Conversiona (%) | Mnb (kDa) | Mwb (kDa) | ÐMb | Chains per Zn |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | - | 15 | 0.21 | 7 | 38.5 | 74.8 | 1.9 | - |

| 2 | - | 30 | 0.54 | 19 | 38.4 | 73.0 | 1.9 | - |

| 3 | - | 45 | 0.79 | 28 | 37.5 | 72.7 | 1.9 | - |

| 4 | - | 60 | 1.05 | 37 | 35.6 | 70.9 | 2.0 | - |

| 5 | 200 | 15 | 0.22 | 8 | 2.1 | 3.1 | 1.4 | 0.5 |

| 6 | 200 | 30 | 0.32 | 11 | 2.3 | 3.4 | 1.5 | 0.7 |

| 7 | 200 | 45 | 0.46 | 16 | 2.6 | 4.2 | 1.6 | 0.9 |

| 8 | 200 | 60 | 0.63 | 22 | 3.0 | 5.2 | 1.8 | 1.1 |

Reaction conditions: 20 mL crimp-cap vial; 1-octene: 4 mL (2.86 g); solvent: toluene (4 mL; Vreaction ∼ 8 mL); 1: 1.0 μmol; MAO: 500 equiv.; stirring rate: 500 rpm; quenching: MeOH/HCl.

aDetermined by 1H NMR. bDetermined by size-exclusion chromatography.

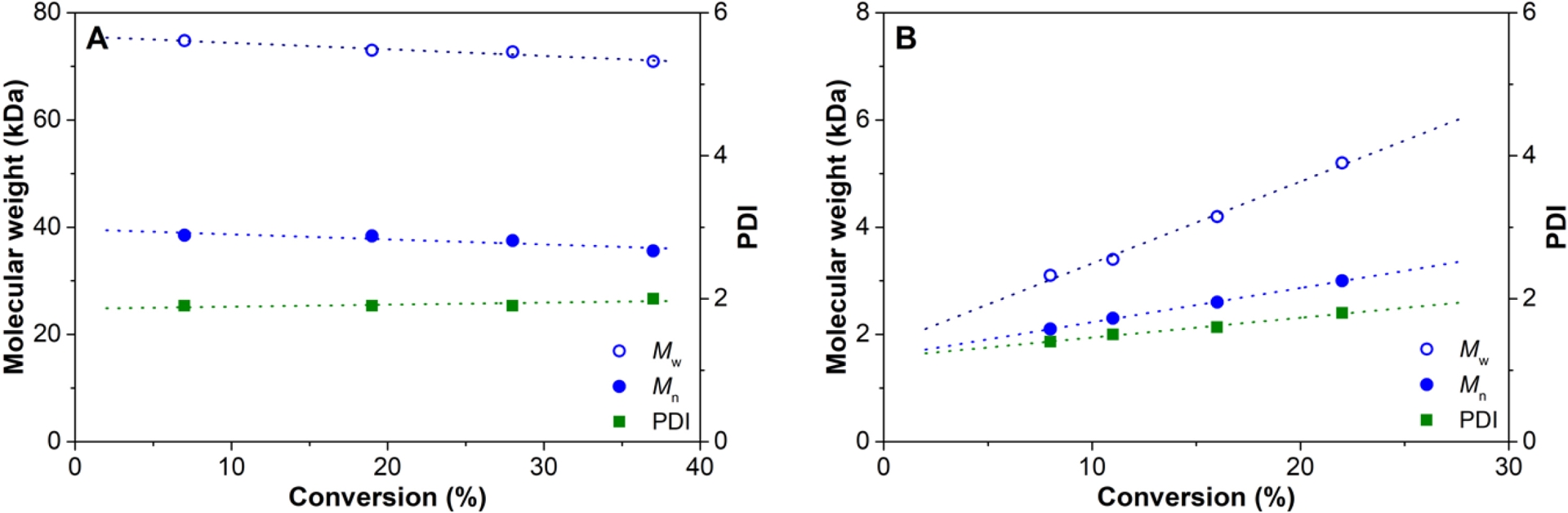

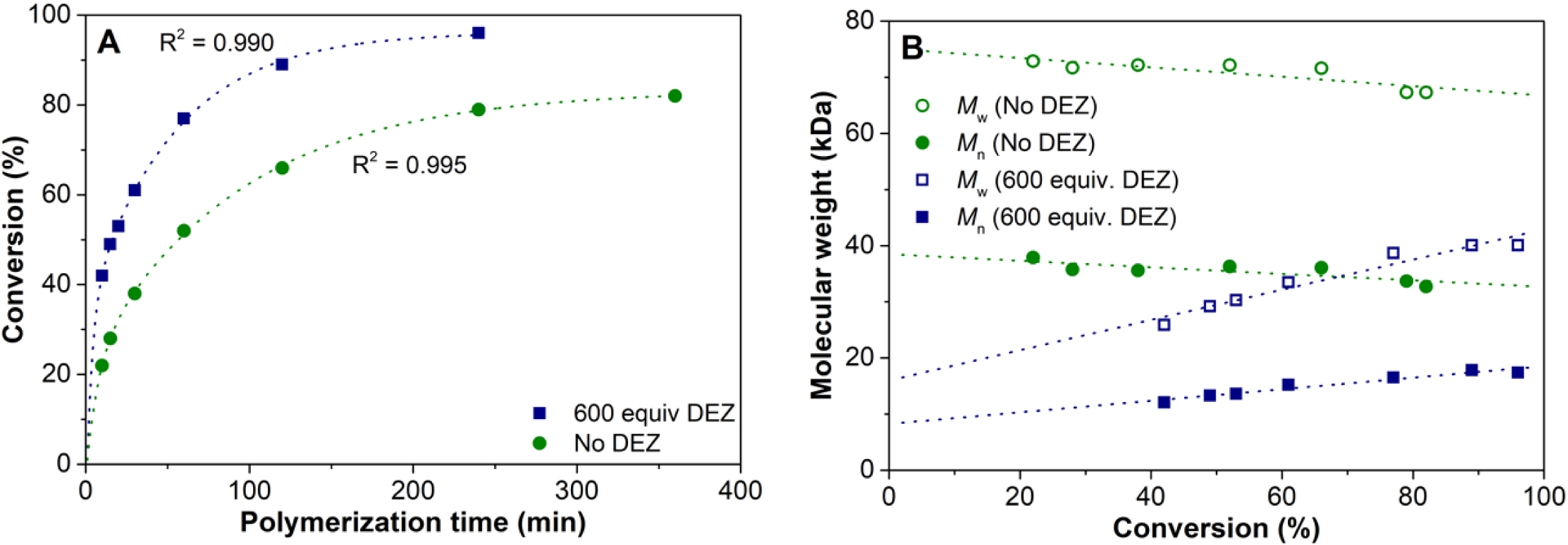

Although no pseudo-living behavior was observed for 4M1P polymerization using 1/MAO/DEZ, the strong effect of DEZ on the molecular weight encouraged us to perform polymerization experiments using the less sterically hindered 1-octene at elevated temperatures to increase the chain transfer rate. Table 2 shows the results for 1-octene polymerization performed using 1/MAO as catalyst system both in the absence and presence of DEZ. In the presence of DEZ, the catalytic activity was clearly lower, suggesting that heterobimetallic catalyst–CTA adducts with a certain stability are formed [38, 39, 40]. This negative effect of DEZ on the activity is opposite to what was observed during 4M1P polymerization. Most likely, the larger steric hindrance of 4M1P reduces the stability of the corresponding intermediate catalyst–CTA adduct. In the absence of DEZ, the molecular weight slightly decreases over time, whereas in the presence of DEZ, the molecular weight clearly increases with progressing polymerization time (Figure 2). The polydispersity of the polymer obtained in the presence of DEZ is significantly lower (ÐM < 2) than in the absence of DEZ, which suggests that reversible chain transfer to zinc takes place for the less sterically hindered 1-octene. The fact that the molecular weight does not increase proportionally with conversion agrees with a kCT being of the same order of magnitude as kCG [37]. Moreover, the calculated number of chains per Zn for poly(1-octene) indicates that only up to one ethyl group is involved in polymer chain exchange during the polymerization at the given conditions (Table 1). The limited exchange of a second ethyl group is most likely caused by the enhanced steric interactions between Zn(Et)-polymeryl species [28, 29].

Molecular weight development versus conversion for 1-octene polymerization at 80 °C using 1/MAO in the (A) absence and (B) presence of DEZ (Table 1).

Sequential and random 4M1P/ethylene copolymerization with 2/B(C6F5)3/DiBAP

| Exp. | 4M1P (min) | $\mathrm{C}_{2}^{=}$a (min) | Yield (g) | #b | Mnc (kDa) | Mwc (kDa) | Ð$_{\mathrm{M}}^{\mathrm{c}}$ | Tgd (°C) | Tmd (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1:10e | 1 | 150.2 | 222.3 | 1.48 | - | - | ||

| 2:20e | 2.11 | 2 | 318.0 | 533.8 | 1.68 | −37.2 | - | ||

| 2 | 1:40 | 1 | 43.8 | 123.0 | 2.81 | 36.7 | 215.8 | ||

| 2:20 | 3.70 | 2 | 73.4 | 294.2 | 4.01 | 36.8 | 235.2 | ||

| 3 | 1:40 | 1 | 37.4 | 115.8 | 3.10 | 36.8 | 226.0 | ||

| 2:20 | 2 | 51.6 | 248.9 | 4.80 | 33.3 | 230.9 | |||

| 3:60 | 5.88 | 3 | 46.8 | 308.1 | 6.59 | 33.3 | 232.2 |

Reaction conditions: 3-neck 200 mL round bottom flask; 2.5 μmol 2; 1.0 equiv. of B(C6F5)3; 8.0 equiv. of DiBAP (diisobutylaluminum 2,6-di-tert-butyl-4-methylphenoxide); solvent: toluene (90 mL); 10 mL 4M1P; stirring rate: 200 rpm; T = 25 °C.

a$\mathrm{C}_{2}^{=}$ = ethylene, pressure = 1.3 bar. b1, 2, 3: samples taken after feed #1, 2 or 3. cDetermined by size-exclusion chromatography. dDetermined by differential scanning calorimetry. eEthylene was added together with 4M1P.

Although CCTP conditions seem to have been achieved for the polymerization of 1-octene, the existence of concurrent chain terminations reactions was checked. The 1H NMR spectra of the poly(1-octene)s produced clearly demonstrated the presence of unsaturated-end-group resonances (Figure S3). Besides the most prominent vinylidene and vinylene end groups, trisubstituted olefin resonances and small amounts of vinyl end-group resonances could be observed. This indicates that β-hydrogen transfer forms the prime concurrent chain termination process [41]. The same unsaturated end-group resonances were found for P4M1Ps produced using 1/MAO/DEZ.

In summary, although the catalyst clearly undergoes chain transfer to zinc and it appears to be reversible in the case of 1-octene polymerization, it is quasi-irreversible for 4M1P polymerization. Furthermore, the competing chain termination by β-hydrogen transfer renders this catalyst unsuitable to produce OBCs from higher α-olefins like 1-octene and 4M1P.

2.2. Pyridylamido hafnium system (2)

The pyridylamido hafnium catalyst system has been reported to be highly prone to undergoing fast and reversible chain transfer to zinc and has been used in DOW Chemicals’ chain shuttling polymerization to produce OBCs [10, 11], Furthermore, Coates and coworkers reported the synthesis of well-defined iPP/HDPE (isotactic polypropylene/high-density polyethylene) di-, tri- and tetrablock copolymers using the living-catalyst system 2/B(C6F5)3/DiBAP (DiBAP: diisobutylaluminum 2,6-di-tert-butyl-4-methylphenoxide) in combination with a sequential feed of propylene and ethylene [8]. Therefore, we hoped that this catalyst system would be a suitable candidate for producing OBCs consisting of P4M1P hard segments and poly(ethylene-co-4M1P) soft segments under CCTP conditions. Catalyst precursor 2 was selected for its high symmetry. Keeping in mind that the first α-olefin insertion takes place in the Hf–aryl bond, selecting 2 with a symmetrical CMe2 bridge in the backbone of the ligand system most likely yields only one major active species [42, 43, 44, 45].

Before studying the CCTP behavior of 2, we were curious to know if the catalyst, when activated with B(C6F5)3/DiBAP, would also be living for the sequential feed copolymerization of ethylene and 4M1P. First, we reproduced abovementioned iPP/HDPE di-, tri- and tetra-block copolymers reported by Coates and coworkers as benchmarks (Table S2). Both the gradual increase in molecular weight and the molecular-weight-dependent average branching density agree with a living catalyst system in combination with a sequential feed of ethylene and propylene (Figure S4).

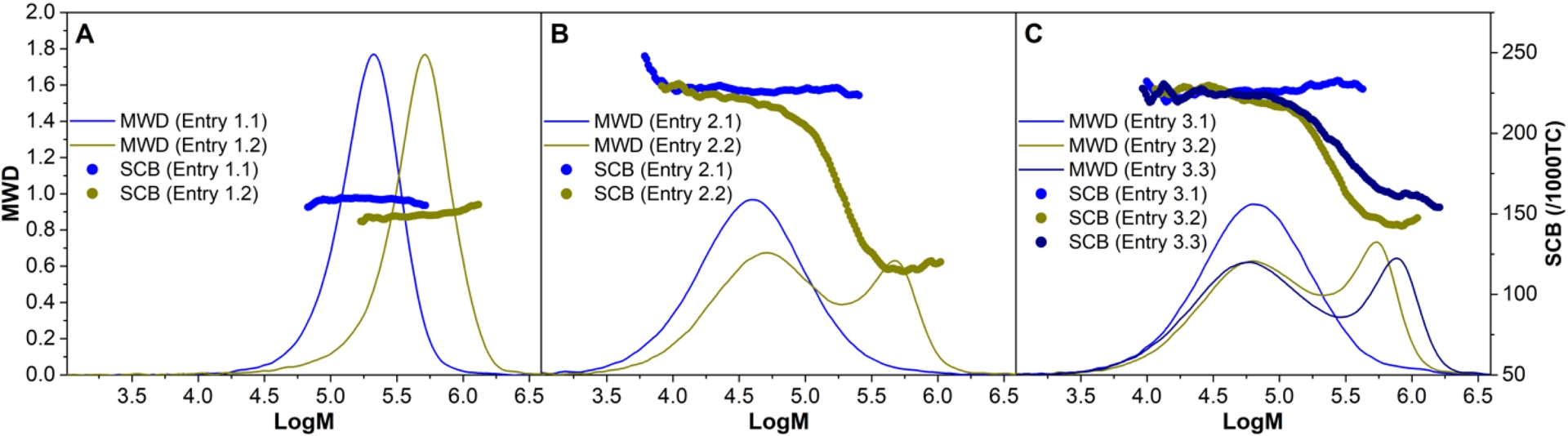

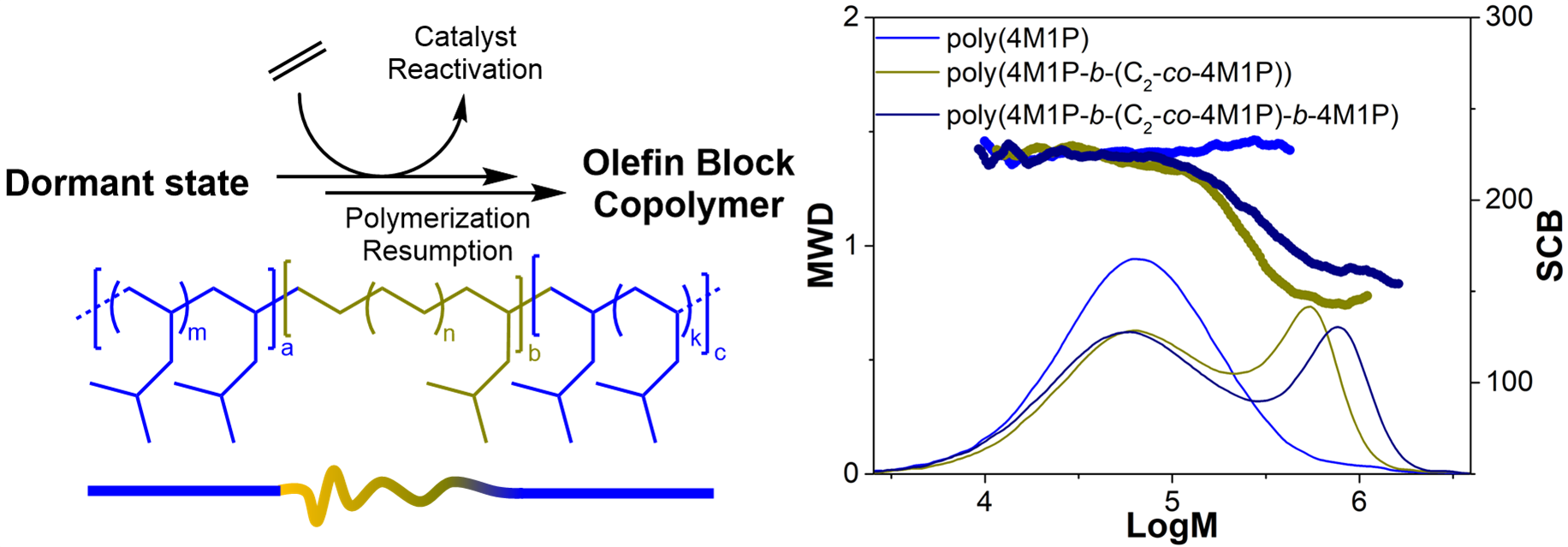

Next, the copolymerization by sequential feeding of 4M1P and ethylene was attempted using the same 2/B(C6F5)3/DiBAP catalyst system as used for synthesizing the iPP/HDPE block copolymers (Table 2). As a benchmark, the random ethylene/4M1P copolymerization was performed, which showed living-like behavior: doubling the polymerization time resulted in a doubling of Mn and the polydispersity remained relatively low and below 2 (Figure 3A).

Molecular weight distributions (MWD) and branching densities per 1000 total nr. of carbons (SCB/1000TC) obtained by high-temperature size exclusion chromatography of: (A) poly(ethylene-co-4M1P) random copolymer (Table 2, entry 1), (B) poly(4M1P-block-(ethylene-co-4M1P)) diblock copolymer (Table 2, entry 2) and (C) poly(4M1P-block-(ethylene-co-4M1P)-block-4M1P) triblock copolymer (Table 2, entry 3).

The situation is quite different when the polymerization is performed using sequential feed polymerization of 4M1P and ethylene. Figure 3B shows the HT-SEC molecular weight distribution of the first P4M1P block formed and the final product where ethylene was added after 60 min polymerization time. The bimodal behavior of the final product suggests that a significant part of the initially formed P4M1P chains had terminated, and only a relatively small fraction of poly(4M1P-block-(ethylene-co-4M1P)) diblock copolymer had been produced. The formation of the diblock copolymer is supported by the drop in the branching density of the diblock product as compared to the branching density of the initial P4M1P precursor. For the 3-step (4M1P − (ethylene + 4M1P) − 4M1P) sequential feed experiment (Figure 3C), the same behavior was observed.

Comparing SEC data of samples taken after (i) 40 min 4M1P homopolymerization, (ii) after addition of ethylene and an additional polymerization time of 20 min, and finally (iii) after 2 h total polymerization time again shows that only a small fraction of the initially formed P4M1P is transformed into the poly(4M1P-block-(ethylene-co-4M1P)) diblock copolymer after adding ethylene. Upon extending the polymerization for another 1 hour, the molecular weight of the high-molecular-weight fraction further increased, and the branching density increased somewhat, which suggests that after all the added ethylene has been consumed, 4M1P continues to be incorporated in the polymer, forming the final poly(4M1P-block-(ethylene-co-4M1P)-block-4M1P) triblock copolymer. Although some triblock copolymer is clearly formed, the bimodal molecular weight distribution obtained for the sequential feed polymerizations and the fact that the molecular weight of the low-molecular-weight fraction does not increase during the progress of the polymerization reveals a non-living nature of the catalyst system 2/B(C6F5)3/DiBAP during 4M1P homopolymerization. Increasing the polymerization temperature from 25 to 60 °C led to deactivation of the catalyst system. These results—in comparison with the living sequential ethylene/propylene copolymerization—clearly show that the living nature of a catalyst is strongly influenced by the nature of the monomers to be polymerized. For the sterically hindered 4M1P, propagation is considerably slower than for ethylene or propylene, which allows β-H transfer to occur as a competing reaction, preventing the selective formation of OBCs.

The low thermal stability of the 2/B(C6F5)3/DiBAP catalyst system, its non-living behavior for 4M1P polymerization, and its incompatibility with DEZ as CTA [46] make B(C6F5)3 an unsuitable cocatalyst in combination with 2 for the polymerization of 4M1P under CCTP conditions. Therefore, B(C6F5)3 was replaced by borate cocatalysts. First, precatalyst 2 activated with N,N-dimethylanilinium tetrakis(pentafluorophenyl)borate ([C6H5N(H)Me2]+[B(C6F5)4]−, AB) using DiBAP as scavenger was applied for the polymerization of 4M1P (Table 3, Table S3, Figure 4).

Molecular weight and polydispersity index (PDI) as a function of conversion for 4M1P polymerization at 60 °C using 2/AB/DiBAP as catalyst system: (A) without DEZ and (B) with DEZ (Table 3).

4M1P polymerization using 2/AB/DiBAP with different amounts of DEZ as CTA

| Exp. | Hf (μmol) | DEZ eq. Hf | t (min) | Yield (g) | Conversiona (%) | Mnb (kDa) | Mwb (kDa) | ÐMb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1c | 0.15 | - | 15 | 0.12 | 9 | 33.3 | 198.7 | 5.9 |

| 2c | 0.15 | - | 30 | 0.47 | 35 | 45.6 | 216.4 | 4.9 |

| 3c | 0.15 | - | 45 | 0.71 | 53 | 56.9 | 224.9 | 3.9 |

| 4c | 0.15 | - | 60 | 0.94 | 70 | -f | -f | -f |

| 5d | 0.15 | 200 | 15 | 0.35 | 13 | 10.9 | 77.0 | 7.1 |

| 6d | 0.15 | 200 | 30 | 1.47 | 55 | 12.5 | 144.8 | 11.6 |

| 7d | 0.15 | 200 | 45 | 1.97 | 74 | 23.8 | 165.0 | 6.9 |

| 8d | 0.15 | 200 | 60 | 2.07 | 78 | 8.9 | 149.0 | 16.6 |

| 9d | 0.15 | 400 | 15 | 0.06 | 2 | 4.8 | 24.9 | 5.2 |

| 10d | 0.15 | 400 | 30 | 1.09 | 41 | 6.1 | 151.4 | 24.9 |

| 11d | 0.15 | 400 | 45 | 1.64 | 62 | 16.3 | 161.6 | 9.9 |

| 12d | 0.15 | 400 | 60 | 1.89 | 71 | 24.2 | 168.8 | 6.9 |

| 13d,e | 0.075 | 800 | 120 | 0.46 | 17 | 8.3 | 98.6 | 11.9 |

Reaction conditions: 20 mL crimp-cap vial; 1.5 equiv. AB; 230 equiv. DiBAP; solvent: MCH/toluene (3 + 1 mL; Vreaction ∼ 8 mL); stirring rate: 500 rpm; T = 60 °C; quenching: MeOH/HCl.

aDetermined by 1H NMR. bDetermined by size-exclusion chromatography. c2 mL of 4M1P. d4 mL of 4M1P. e460 equiv. DiBAP. fPolymer not fully soluble in o-DCB.

While the activity was very low at 25 °C, the system is much more active at 60 °C than compared to the borane-activated system. However, raising the temperature further to 100 °C resulted in a significant drop in the activity (Table S3). The molecular weight of the polymer also strongly depends on the polymerization temperature and Mw values dropped by two orders of magnitude when the temperature was raised from 25 to 100 °C. Interestingly, the system shows an unusually long initiation period of about 10 min (Figure S5). Recently, a similar long initiation time has been reported for the 1-octene polymerization of the closely related pyridylamido hafnium catalyst, 2′, containing a CH(2-iPr-C6H4) bridge instead of a CMe2 bridge between the pyridine and the amido functionalities of the ancillary ligand [3, 47]. Already at low conversion, rather high molecular weights are obtained (Figure 4A), but the molecular weight increases somewhat further with polymerization time. However, it does not increase proportionally to the 4M1P conversion, indication that the catalyst system is non-living. The polydispersity is unusually broad for a single-site catalyst system and is considerably broader than when B(C6F5)3 was used as cocatalyst (see above).

The presence of DEZ has a slightly positive effect on the catalytic activity with the highest activity for 200 equiv. of DEZ (Figure S5). Although the molecular weight values obtained are somewhat scattered and there is little difference between adding 200 or 400 equiv. of DEZ (Table 3), the molecular weights do increase with conversion (Figure 4B). A rough estimation of the chain transfer rate constant based on the Mayo equation demonstrates that chain transfer to zinc is of the same order of magnitude as chain growth (kCT/kCG = 6.3, Figure S6) [37]. However, the very broad polydispersity of the products—even broader than observed in the absence of DEZ—suggests that the chain transfer is quasi-irreversible. Analyses of the products by 1H NMR indeed show the existence of unsaturated vinylidene and vinylene end groups, which indicates that the presence of DEZ cannot prevent concurrent chain termination by β-H transfer. These observations agree with results obtained by Landis and coworkers [28], who found similar fast and essentially irreversible chain transfer to zinc (kCT/kCG = 7.27) accompanied by concurrent β-H transfer for 1-octene polymerization using the closely related pyridylamido hafnium catalyst 2′.

Next, 4M1P polymerization experiments with trityl borate ([C(C6H5)3]+[B(C6F5)4]−, TTB) were carried out at different temperatures, with and without DEZ as CTA (Table S4). The 2/TTB/DiBAP system resembles the 2/AB/DiBAP system: the activity increases with increasing temperature from 25 to 60 °C and decreases once the temperature is increased further to 100 °C. In the absence of DEZ, there is no significant change in molecular weight and polydispersity with increasing polymerization time as was observed in the AB-activated system. Like for the AB-activated system, the temperature has a dramatic effect on the molecular weight, which clearly indicates that chain termination takes place (Figures S7, S8). The polydispersity of the polymer also drops with increasing temperature, but it remains high for a single-site catalyst with a value around 4.

Adding DEZ as CTA resulted in a clear reduction in molecular weight. For polymerizations performed in the presence of DEZ at 25 °C, a clear correlation between molecular weight and monomer conversion could be observed (Figure S9). Due to interference from the competitive chain termination (see above), the molecular weight does not show a clear trend as a function of polymerization time at 60 °C (Figure S10). The addition of DEZ resulted in a significant broadening rather than a narrowing of the polydispersity, which hints at irreversible chain transfer.

To investigate how steric hindrance at the active site affects the chain transfer to zinc and to be able to directly compare the results for 2 with the results of Landis et al. on 2′, polymerization experiments using AB/DiBAP as activator system were performed with the sterically less hindered 1-octene as the monomer (Table S5). The same unusual initiation period of around 10 min as during the 4M1P polymerization was observed (Figure S11A), in agreement with Landis’ results [3, 47]. As expected, the final molecular weight increases linearly with the initial 1-octene concentration both with and without DEZ (Table S6, Figure S12). The difference in steric hindrance between 1-octene and 4M1P is reflected in a higher molecular weight of the poly(1-octene) compared to P4M1P obtained under the same polymerization conditions (cf. Table 3, Table S3). Like for 4M1P polymerization, the presence of DEZ leads to an increase in catalytic activity (Figure S11A). Without DEZ, the molecular weight remains constant during the whole polymerization period in agreement with a non-living polymerization system. In the presence of DEZ the molecular weight starts significantly lower and increases with polymerization time, although it does not follow the 1-octene conversion as would be expected for a pseudo-living system (Figure S11B). Chain transfer to zinc is of the same order of magnitude as chain growth (kCT/kCG = 3.1, Figure S13). However, the fact that the polydispersity is three to four times broader than without DEZ, in tandem with the number of chains per zinc being greater than 2, suggest that it is quasi-irreversible, as was observed for the 1-octene polymerization using 2′ [28].

Furthermore, 1H NMR clearly shows the presence of various unsaturated end-group resonances indicating that competitive β-H and β-alkyl transfer takes place after both 1,2-insertion and 2,1-misinsertion (Figure S14), which also contributes to the broad polydispersity. These results are similar to those reported by Landis and coworkers on 1-octene polymerization using the closely related 2′, who also found fast but irreversible chain transfer to zinc accompanied by β-H transfer [28].

It can be concluded that the behavior of 2 activated with borates is broadly comparable for 1-octene and 4M1P polymerization. The addition of DEZ clearly leads to a dramatic drop in molecular weight and a broadening of the polydispersity. Whereas chain transfer to zinc takes place, the high polydispersity suggests that it is quasi-irreversible. Furthermore, β-H and β-alkyl transfer is a seriously competitive reaction, which renders this catalyst system unsuitable to produce multiblock copolymers consisting of sterically hindered higher α-olefins such as 4M1P.

2.3. Bis(phenolate)diether hafnium system (3)

Another contender in our quest for 4M1P-based OBCs is the hafnium bis(phenolate)diether complex 3, originally developed by SYMYX and later employed by for example DOW Chemicals and ExxonMobil for its excellent ability to incorporate higher α-olefins [33, 34, 35]. We decided to focus first on 1-octene polymerization and subsequently to apply the optimized conditions to 4M1P polymerization.

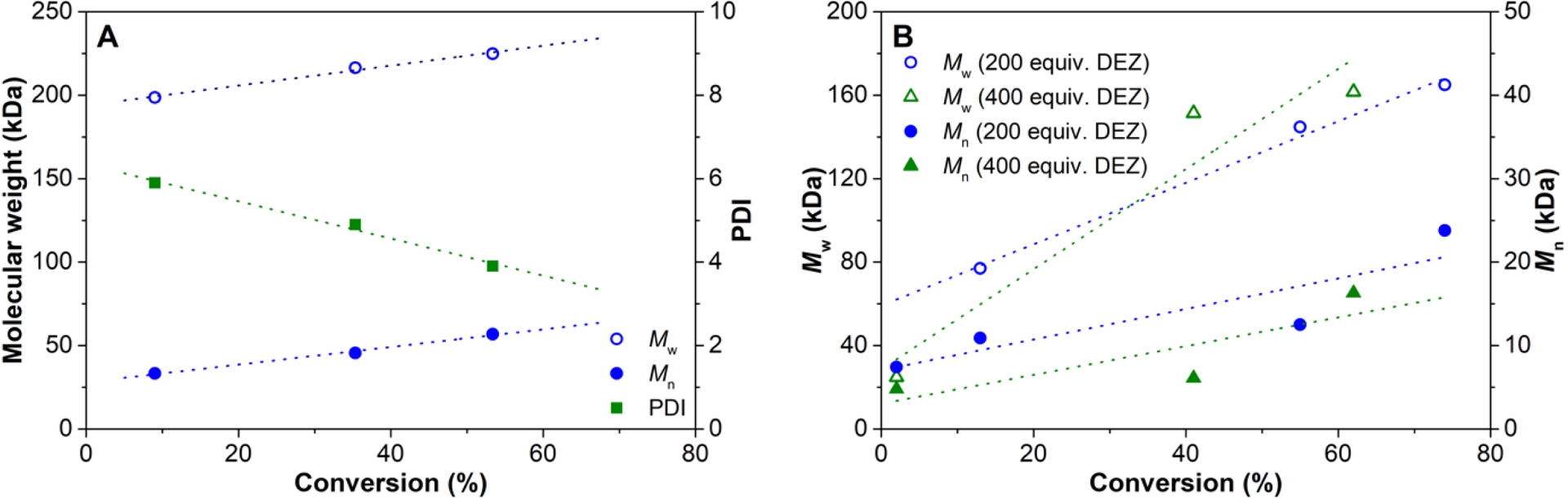

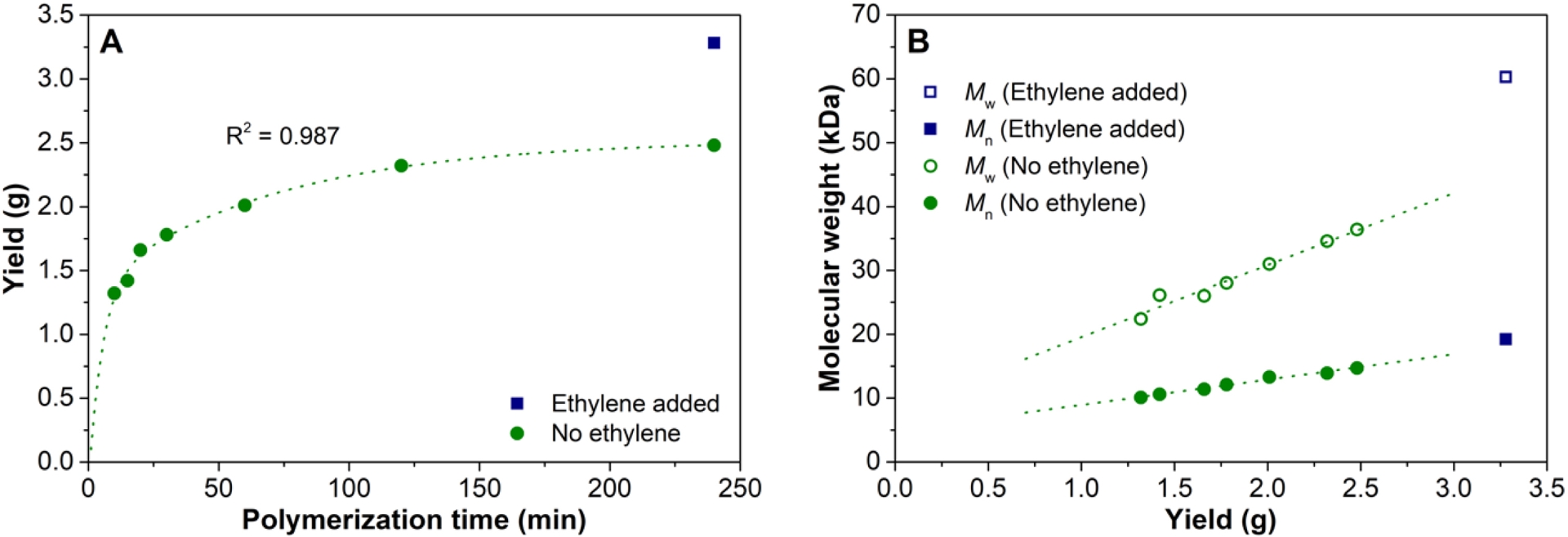

The 1-octene polymerizations were performed using TTB as cocatalyst and trimethylaluminum (TMA) as scavenger [35]. It is worth mentioning that the catalyst is thermally considerably more stable than 1 and 2 as it shows a surprisingly long lifetime of several hours at 100 °C. This is important in view of commercial solution polymerization processes, which are run at elevated temperatures. Under the polymerization conditions applied, the catalyst system follows first order kinetics in monomer, gives reasonably high 1-octene conversions, and produces polymers with moderate molecular weights and polydispersities around 2 as expected for a single-site catalyst (Table S7, Figure 5A). In the absence of DEZ, the molecular weight slightly drops with conversion, in line with the decreasing monomer concentration (Figure 5A). The addition of DEZ leads to a slight increase in catalytic activity, clearly indicating that there is no negative effect of catalyst–CTA adduct formation (Figure 5B) [38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45]. Furthermore, the molecular weight is significantly lower and increases linearly albeit not proportionally with 1-octene conversion. The polydispersity around 2 is in line with moderately fast and reversible chain transfer and agrees with the observed kCT/kCG = 13.5 (Figure S15). This is further supported by the number of polymer chains per zinc, which gradually increases with increasing 1-octene conversion, reaching a maximum value around 2 (Table S7). This shows that 3 is more tolerant to the steric hinderance of the Zn(Et)-polymeryl species during chain transfer than 1 and 2.

(A) Conversion versus polymerization time and (B) molecular weight as a function of conversion for 1-octene polymerization at 100 °C, without and with 600 equiv. of DEZ (Table S7).

To verify the existence of concurrent processes such as β-H transfer, 1H NMR spectroscopy was used (Figure S16). The 1H NMR spectrum revealed the presence of several low-intensity signals in the olefinic region (4.5–6.0 ppm) attributed to unsaturated end groups. The major resonances were assigned to vinylene (∼80%, δ 5.37 ppm) and vinylidene (∼15%, δ 4.67 and 4.73 ppm) species. The other peaks of even lower intensity were assigned to trisubstituted unsaturated and vinyl end groups. Thus, contrarily to complexes 1 and 2, complex 3 hardly undergoes β-H elimination after 1,2-insertion, and the main termination reaction proceeds via β-H transfer after 2,1-misinsertion [30]. Obviously, concurrent chain termination processes are detrimental for the attempted formation of OBCs via CCTP. However, as the prevalent concurrent chain transfer process consists in chain termination after 2,1-misinsertion and its occurrence is low, there might be a way to overcome this.

A possible approach to reactivate the dormant site formed after 2,1-misinsertion without chain scission is the addition of sterically unhindered ethylene that might be able to insert after a 2,1-misinsertion [48, 49]. Figure 6 shows the result of bubbling ethylene through the polymerization product mixture after the catalytic activity had ceased (Experiment 8, Table S8). A significant increase in the 1-octene conversion, polymer yield, and in molecular weight (ΔMn = 30%, ΔMw = 66%) could be observed, which clearly indicates that addition of ethylene indeed reactivates the catalyst. Experiments where 1-octene was polymerized in the presence of a small amount of ethylene added at the beginning of the polymerization (Table S9, Figure S17) showed an initial increase in activity, which subsequently leveled off to the same rate as observed in the absence of ethylene. Most likely, the ethylene is consumed very rapidly after which the 1-octene homopolymerization takes place. This is supported by the nearly identical molecular weight build up with 1-octene conversion for both systems, with and without ethylene. Although the presence of ethylene truly seems to reactivate the catalyst after 2,1-misinsertion, addition of small amounts of ethylene only at the beginning of a batch polymerization does not have the desired effect. A continuous flow of a minute amount of ethylene will be needed to (i) continuously reactivate the catalyst and (ii) avoid incorporation of too much ethylene. Unfortunately, this was not possible in the currently applied reactor setup.

(A) 1-Octene conversion as a function of time using 3/1.5 TTB/100 TMA/600 DEZ at 100 °C. Addition of ethylene after 120 min. (B) Molecular weight as a function of yield, without and with addition of ethylene after 120 min (Table S8).

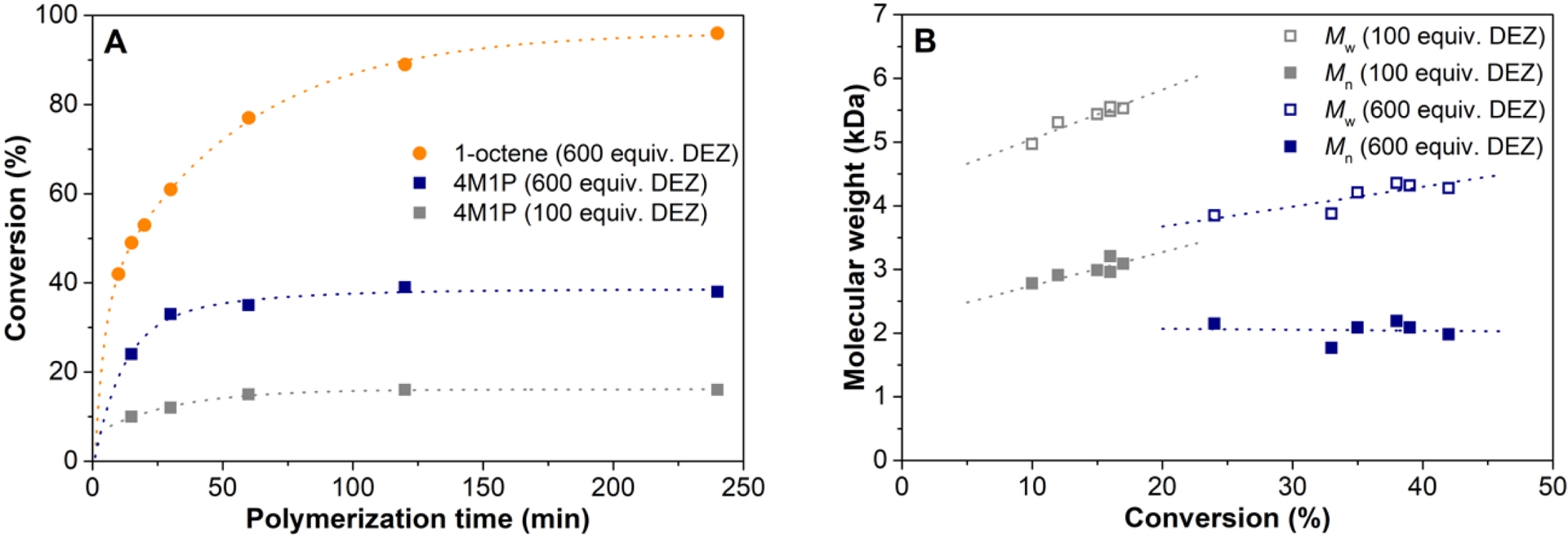

Using the optimized conditions for 1-octene polymerization, 4M1P polymerization experiments have been performed (Table S10). The conversion versus time plots for 4M1P and 1-octene polymerization (Figure 7A) reflect the difference in reactivity of the two monomers: where the conversion of 1-octene in the presence of 600 equiv. of DEZ is 89% after a polymerization time of 120 min, it is only 39% for 4M1P, and the catalyst lost most of its activity after 30 min at 100 °C. Possibly, for the more sterically hindered 4M1P, the 2,1-misinsertion deactivates the catalyst to a large extent leading to a low overall conversion. Additionally, it should be noted that commercial-grade 4M1P, contrary to commercial-grade 1-octene, contains isomers with internal double bond, like 4-methyl-2-pentene, that could lead to catalyst poisoning and low-molecular-weight products.

(A) Comparative conversion versus polymerization time plot for the 1-octene (Table S7) and 4M1P (Table S10) polymerizations and (B) molecular weight as a function of conversion for 4M1P polymerization with 100 and 600 equiv. of DEZ versus catalyst (Table S10), using the 3/TTB/TMA/DEZ system at 100 °C.

The molecular weight clearly drops with increasing DEZ concentration, and the molecular weight increases linearly with increasing conversion (Figure 7B), clearly indicating chain transfer to zinc. The most prominent concurrent chain transfer process is β-H transfer after 2,1-misinsertion also for 4M1P polymerization as revealed by 1H NMR.

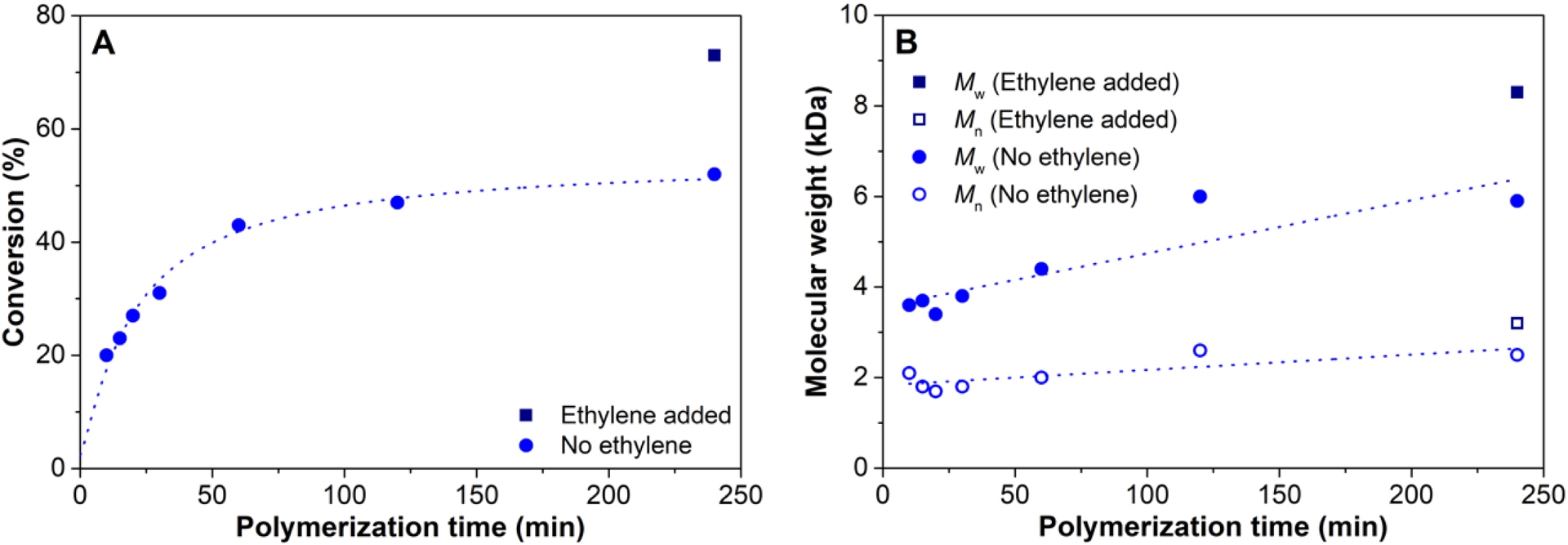

As experience has taught us that MAO effectively activates precatalyst 3 providing a long-living active species during propylene and 1-octene polymerization, we performed 4M1P polymerizations in the presence of DEZ and MAO as cocatalyst. The 4M1P conversion turned out to be somewhat higher than with the TTB-activated system (52% versus 39%; Figure 8), but a comparable deactivation due to the formation of dormant sites after 2,1-misinsertion is expected.

(A) 4M1P conversion versus polymerization time for the 4M1P(/ethylene) (Table S11) and (B) molecular weight as a function of polymerization time for 4M1P(/ethylene), using the 3/MAO/DEZ system at 100 °C.

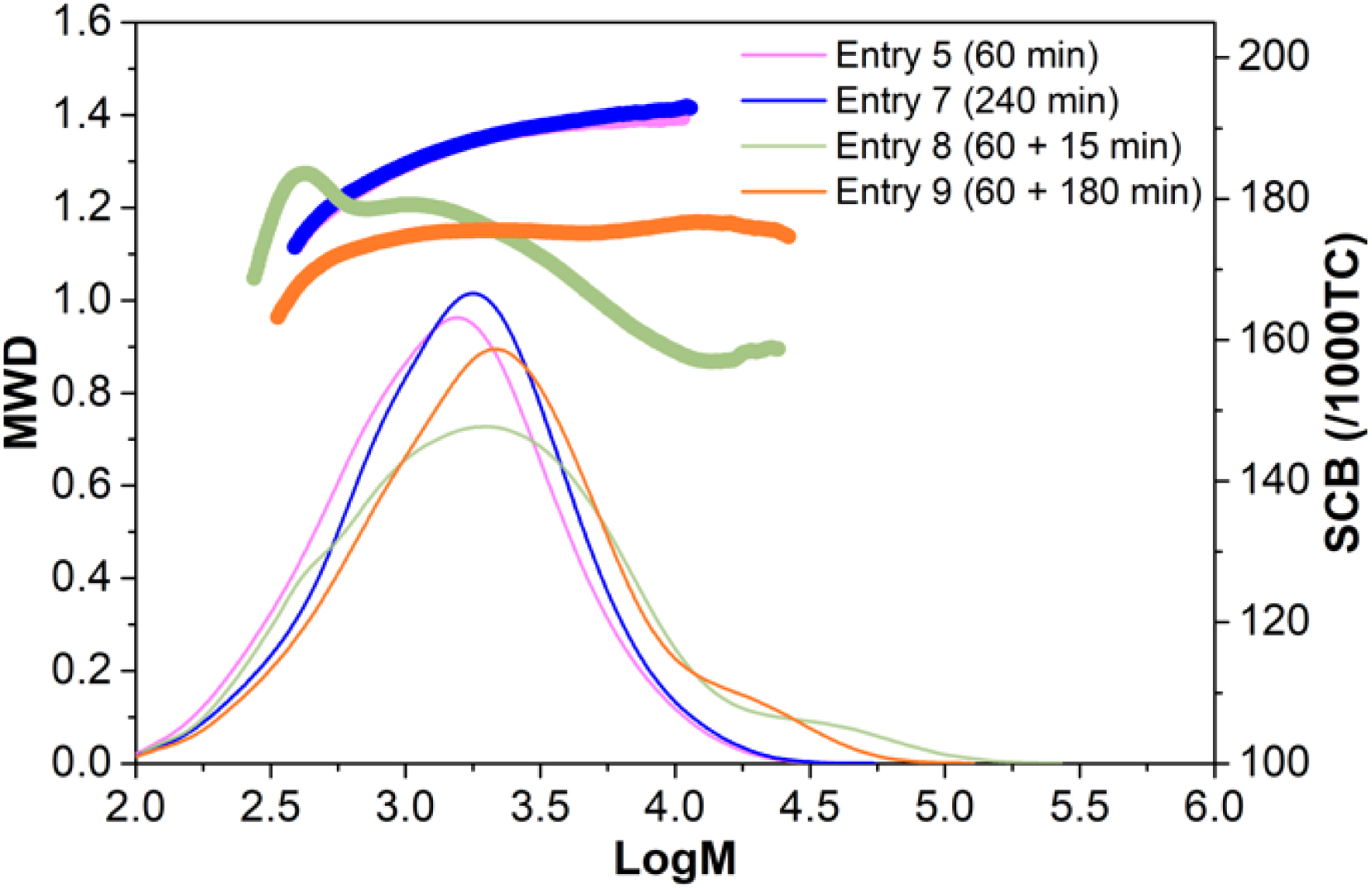

Indeed, addition of ethylene after 1 hour reaction time clearly demonstrated an increase in 4M1P conversion (>20%) and a considerably higher (>30%) polymer molecular weight (Table S11, Figure 8, 9). The size-exclusion-chromatography traces (Figure 9) show that after the addition of ethylene the initial monomodal distribution shifts to higher molecular weight but also transforms into a more bimodal distribution having a high molecular weight tail. This suggests that to some extent β-H transfer does occur, which is supported by the fact that the number of polymer chains per zinc is higher than 2. Nevertheless, the high branching density measured for the P4M1P homopolymer, followed by a clear drop in branching density a few minutes after ethylene addition, and finally an increase in the branching density 2 h after ethylene addition (Figure 9) supports the formation of a triblock copolymer. The thus formed triblock copolymer, consisting of (i) a P4M1P first block, (ii) a random/gradient copolymer poly(ethylene-co-4M1P) block followed by (iii) a second P4M1P block formed after all ethylene has been consumed, would be expected to have a melting temperature similar to that of a P4M1P homopolymer but a lower crystallinity. This is indeed observed (Table S11).

Molecular weight distributions (MWD) and short-chain branching (SCB) obtained by high-temperature size-exclusion chromatography of (i) P4M1P after 60 min (Table S11, entry 5), (ii) P4M1P after 240 min (Table S11, entry 7) and (iii) poly(4M1P-block-(ethylene-co-4M1P)-block-4M1P) triblock copolymer (Table S11, entry 8) applying the 3/MAO/DEZ system.

Unfortunately, the molecular weight of the P4M1P homopolymers and the corresponding putative block copolymer are clearly too low to afford materials with good mechanical properties. Most likely, 2,1-misinsertion is a rather common process for this catalyst resulting in short P4M1P blocks before the active site is deactivated. Thus, the production of higher molecular weight material was attempted by reducing [DEZ]:[complex 3] molar ratio down to 50, reducing the polymerization time before ethylene addition to only 10 min, and limiting the total reaction time to 40 min. Nevertheless, unfortunately only materials with a maximum Mn around 4.7 kDa (ÐM = 2.3) were achieved.

3. Conclusions

The three catalysts that were tested in the polymerization of 1-octene and 4M1P showed both similarities and clear differences. All three catalysts clearly show chain transfer to zinc and the kCT and kCG rate constants are in the same order of magnitude for catalyst 1 and 2, whereas for catalyst 3 the kCT rate constant is around one order of magnitude higher than the kCG rate constant. Furthermore, whereas catalyst 1 demonstrates reversible chain transfer for the polymerization of 1-octene but irreversible for the polymerization of 4M1P, catalyst 2 shows irreversible chain transfer for both 1-octene and 4M1P polymerization. Catalyst 3 undergoes reversible chain transfer to zinc for both 1-octene and 4M1P polymerization but suffers severely from 2,1-misinsertion leading to dormant sites. All catalysts suffer from concurrent β-H transfer processes, which can be attributed to the steric hindrance of the applied α-olefins.This steric hindrance lowers the chain growth rate constant and hence increases the probability of chain scission. Interestingly, for catalyst 3, β-H transfer after 2,1-misinsertion appeared to be the prevalent competing chain transfer process. Adding a small amount of ethylene clearly reactivated the dormant site formed after 2,1-misinsertion of 3 without terminating the growing polymer chain, which opens a route toward the desired olefinic block copolymers. Nevertheless, under the batch conditions used, concurrent β-H transfer could not be fully prevented.

Declaration of interests

The authors do not work for, advise, own shares in, or receive funds from any organization that could benefit from this article, and have declared no affiliations other than their research organizations.

Funding

The work was financially supported by SABIC, which is gratefully acknowledged.

Underlying data

Supporting information (experimental details, additional tables and graphs and NMR spectra of selected samples) for this article is available at https://hal.science/hal-05264753.

CC-BY 4.0

CC-BY 4.0