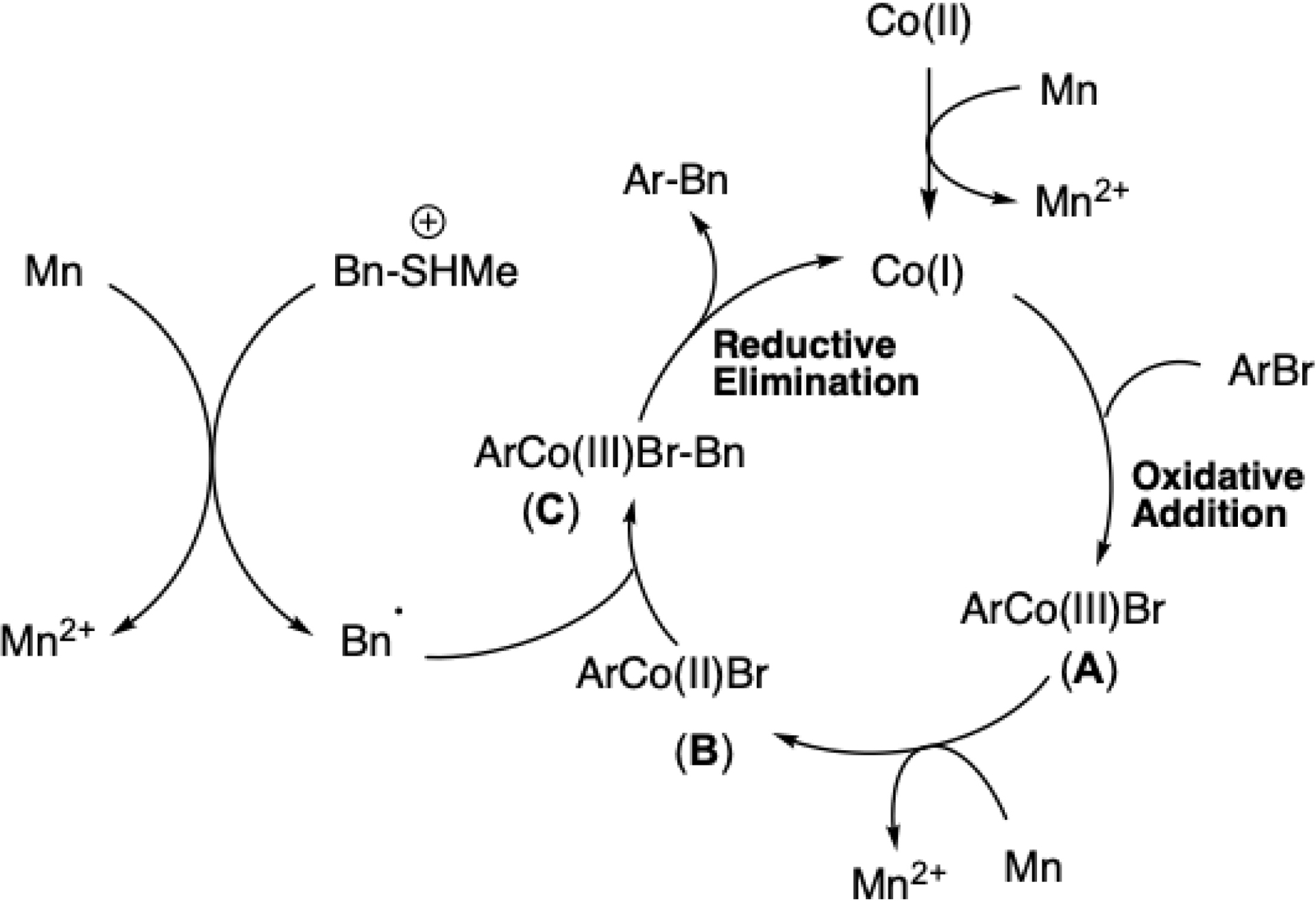

Nowadays, the formation of carbon–carbon (C–C) bonds via cross-electrophile coupling (XEC) or electrochemical cross-electrophile coupling (eXEC), catalyzed by transition metals, has emerged as a powerful and attractive strategy in synthetic chemistry [1, 2, 3]. The construction of C–C bonds is fundamental to the synthesis of a wide range of key molecules, including pharmaceuticals, agrochemicals, and basic organic materials. Compared to classic cross-coupling reactions involving the reaction of an organometallic (nucleophile) with an electrophile in the presence of a transition metal catalyst (notably palladium, as recognized by the 2010 Nobel Prize in Chemistry) [4], XEC or eXEC reactions offer several key advantages (Scheme 1). Notably, they eliminate the need for the preparation and handling of sensitive organometallic compounds in stoichiometric amount, simplify operations through one-step procedures, and exhibit broad functional group tolerance.

Conventional cross-coupling vs cross-electrophile coupling.

Although cobalt-catalyzed cross-couplings with organometallic reagents (e.g., Grignard reagents or zinc species) have been described, XECs (previously called reductive or direct couplings) have emerged as a robust and versatile alternative [5, 6, 7, 8]. These reactions enable the formation of diverse carbon–carbon and carbon–heteroatom bonds—including Csp2–Csp2, Csp2–Csp3, Csp3–Csp3, and Csp–Csp3 linkages—under mild conditions, using two electrophilic partners such as stable halides or pseudo-halogenated substrates.

Prior to the emergence of modern XEC, eXEC of two electrophiles [9, 10, 11] had already been explored, particularly by Périchon and coworkers, predominantly using nickel catalysts [12]. These early contributions laid the foundation for the development of a wide range of nickel-catalyzed eXEC methods.

In an effort to replace nickel with a more cost-effective and environmentally benign alternative, we pioneered the use of cobalt in electroreductive C–C bond formation via sacrificial anode processes [13]. Cobalt is particularly attractive due to its low cost, broad functional tolerance, and improved ecological footprint compared to nickel. Despite the increased accessibility of electrosynthesis in recent years—thanks in part to the advent of user-friendly equipment such as the IKA ElectraSyn—this technique was historically regarded as more complex and less practical than conventional synthetic methods, which significantly limited its adoption within the organic chemistry community.

It is worth noting that the concept of XEC dates back to the 19th century, with Wurtz’s pioneering work using stoichiometric sodium metal at elevated temperatures [14]. However, such harsh conditions were incompatible with many functional groups, which curtailed its utility. To overcome the challenges associated with electrosynthesis or the use of palladium at high temperature [15, 16], we reported in 2003 the first XEC of two distinct electrophiles under non-electrochemical conditions, employing a first-row transition metal catalyst, Co, in combination with metal reducers (Zn or Mn) [17]. This approach offered excellent functional group tolerance and operational simplicity.

Since 2010, the field of XEC has witnessed substantial growth, with many research groups initiating work in this area, primarily concentrating on nickel-catalyzed transformations [18, 19, 20]. These transformations typically use Ni(II) precursors along with either metallic reductants (Zn, Mn) or homogeneous reductants such as tetrakis(dimethylamino)ethylene (TDAE) [21] or bis(pinacolato)diboron (B2pin2) [22]. In contrast, examples involving other metals—such as Cu [23], Fe [24], or Cr [25]—remain comparatively rare. Photoredox catalysis has also emerged as a complementary strategy to minimize the use of stoichiometric metal reductants in XECs [26, 27].

Despite being less extensively developed than nickel-catalyzed systems, cobalt-catalyzed XECs have shown interesting complementary reactivity and offer unique advantages in certain transformations [28]. Recognizing these advantages, we have pursued our studies on cobalt catalysis, particularly for the formation of Csp2–Csp2, Csp2–Csp3, and Csp3–Csp3 bonds.

This account highlights the contributions of our laboratory to the development of cobalt-catalyzed reductive cross-coupling reactions for the construction of C–C bonds from C–X (X = Cl, Br, I), C–O, C–N, and C–S bonds, using both electrochemical (eXEC) and conventional (XEC) approaches.

These methods are operationally simple and robust. In the case of eXEC, reactions are typically conducted in undivided cells equipped with an iron anode and a nickel foam cathode, with the choice of anode proving critical to the success of the reaction. Both electrochemical and classical approaches are carried out in solvents such as acetonitrile (CH3CN) or dimethylformamide (DMF), with or without pyridine, under inert atmosphere (argon) at room temperature or moderate temperatures (up to 50 °C). The cobalt catalyst generally consists of commercially available CoBr2 or CoCl2, with negligible differences observed between these two salts. Additionally, the use of ancillary ligands (e.g., bipyridine or phosphines) is not always required, further simplifying the protocol.

1. Formation of C(sp2)–C(sp2) bonds

1.1. Biaryl formation

Unsymmetrical biaryls are key structural motifs found in a broad range of biologically active compounds, including natural products, pharmaceuticals, functional materials, and agrochemicals [29, 30, 31]. Traditionally, their synthesis involves the transition-metal-catalyzed cross-coupling of an aryl halide with an organometallic reagent—such as arylboronic acids, arylzinc, stannane, or Grignard derivatives—typically mediated by palladium or nickel catalysts.

Pioneering work by Kharasch and coworkers has demonstrated that aryl Grignard reagents can undergo efficient homocoupling in the presence of catalytic amounts of first-row transition metal salts such as cobalt(II) chloride (CoCl2) [32]. Beyond homocoupling, cobalt has also proven to be an effective catalyst for cross-coupling reactions between two different aryl partners. Notably, Nakamura et al. [33] and von Wangelin et al. [34] have independently showed that cobalt salts catalyze the cross-coupling between aryl Grignard reagents and aryl or heteroaryl halides, enabling the formation of unsymmetrical biaryls. This strategy has since been extended to include aryl tosylates as electrophilic partners by using a cobalt diisopropyl disubstituted bis(phosphino)pyridine pincer (iPrPNP)-based catalyst [35].

In a complementary approach using commercially available precursors, cobalt precatalysts bearing N-heterocyclic carbene (NHC) ligands, have also been employed in Suzuki–Miyaura cross-coupling reactions of aryl chlorides and bromides with arylboronic pinacol esters, activated in situ with alkyllithium reagents [36].

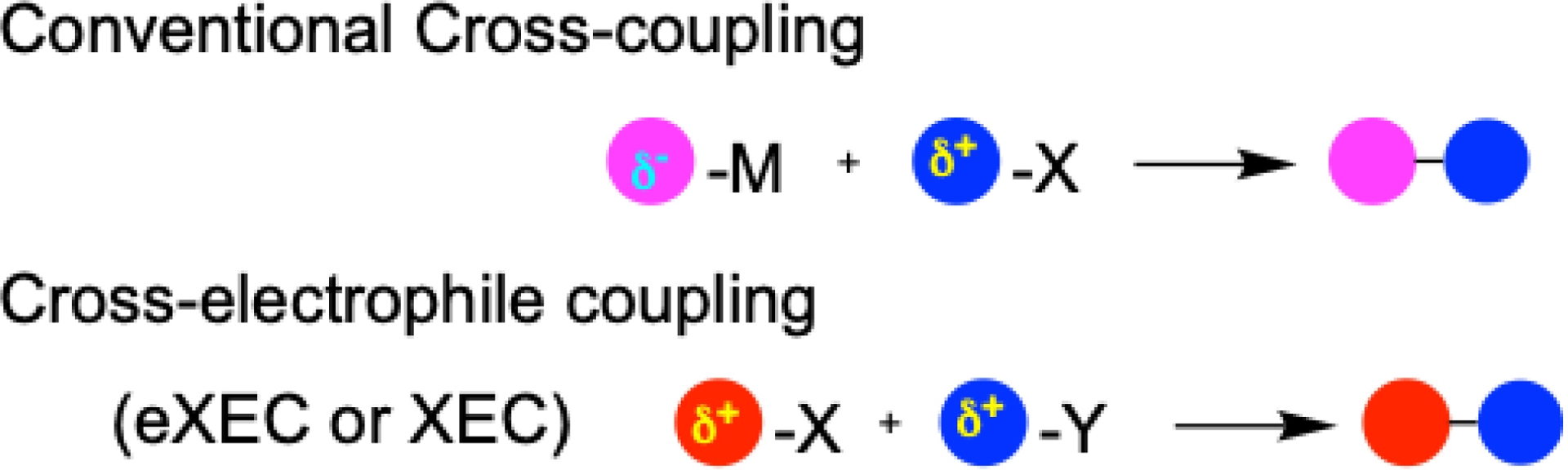

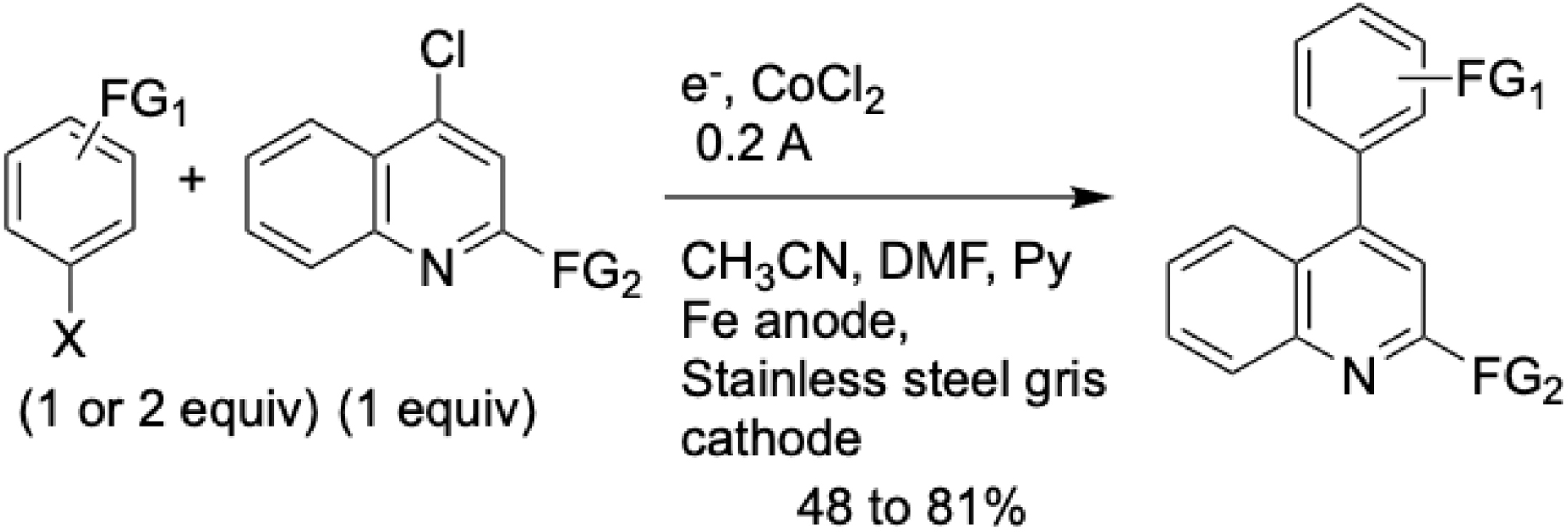

To circumvent the need for stoichiometric organometallic reagents, the first cobalt-catalyzed eXEC was developed for biaryl synthesis. Initially, the method used aryl halides and 4-chloroquinolines as electrophilic partners (Scheme 2) [37]. This was later expanded to include couplings between two distinct aryl halides (Scheme 3) [38]. In both cases, the reactions were conducted in an undivided electrochemical cell equipped with an iron anode and required pyridine as a ligand to activate the cobalt catalyst.

Electroreductive cobalt-catalyzed cross-coupling of functionalized phenyl halides with 4-chloroquinoline derivatives.

Synthesis of unsymmetrical biaryls by electroreductive cobalt-catalyzed cross-coupling of aryl halides.

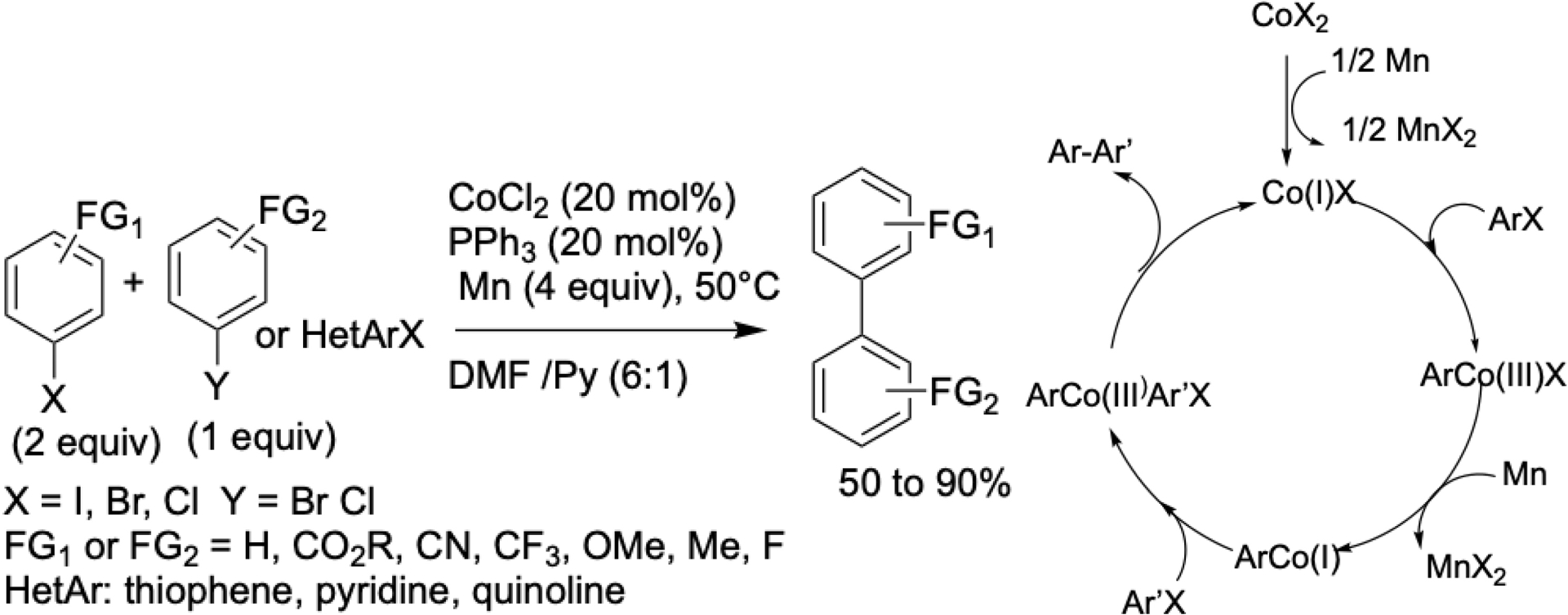

The aromatic moiety involved in these transformations can accommodate a broad range of electron-donating and electron-withdrawing substituents. In 2008, the cobalt-catalyzed synthesis of biaryls via eXEC was successfully adapted to conventional chemical methods by changing some parameters (Scheme 4). These included reactions between two aryl halides or between an aryl halide and a heteroaryl halide with comparable reactivities [39]. In this protocol, manganese powder was employed as the reductant in a DMF/pyridine solvent system. The cobalt(II) bromide (CoBr2) catalyst, ligated with triphenylphosphine (PPh3), enabled the efficient formation of unsymmetrical biaryls in good yields. With these adapted reaction conditions, the proposed mechanism proceeds via a non-radical pathway.

Cobalt-catalyzed formation of unsymmetrical biaryl compounds and proposed mechanism.

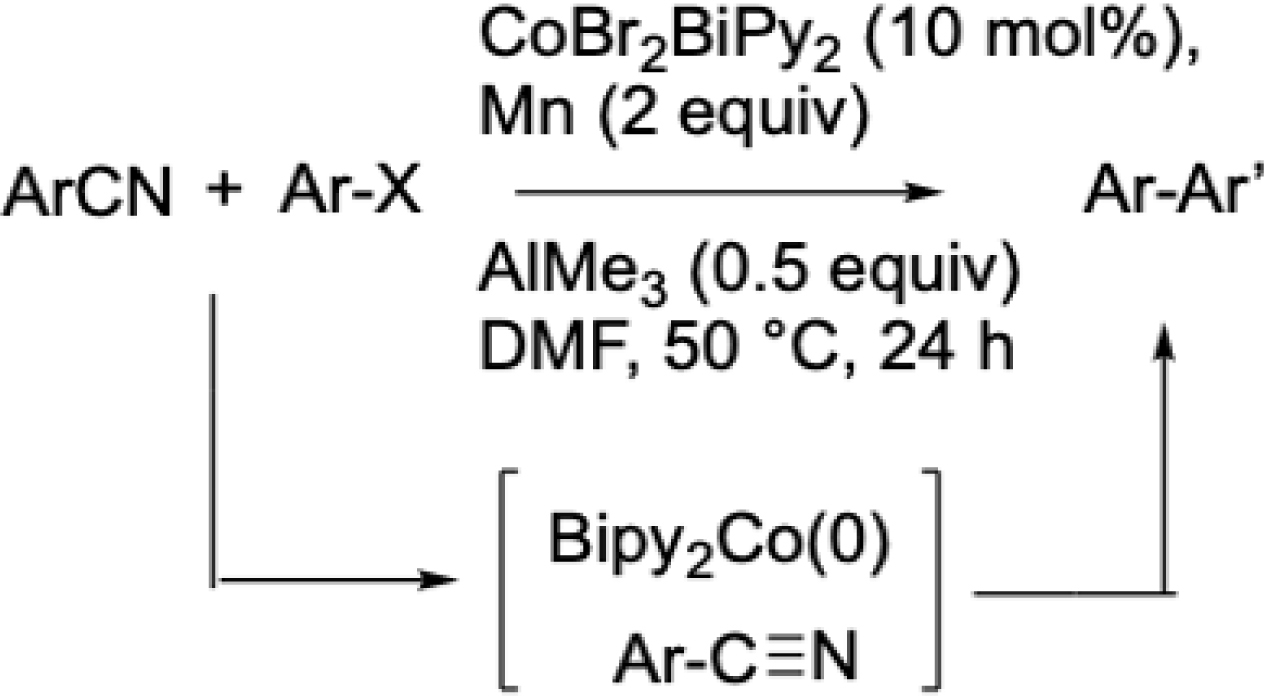

We applied this strategy to the synthesis of 2-(4-tolyl)benzonitrile, a key intermediate in the preparation of sartans—widely used antihypertensive agents. More recently, we demonstrated that cobalt catalysis could be extended to inert C–CN bond activation, thereby enabling the challenging formation of biaryls from aryl halides and benzonitriles—an approach that poses a greater synthetic challenge (Scheme 5) [40]. In this system, the addition of AlMe3 to the reaction medium enhanced the reactivity of the aryl–CN bond.

Cobalt-catalyzed biaryl formation mediated by C(sp2)–CN bond activation.

Combined DFT calculations and experimental studies revealed that the reaction proceeds through the in situ generation of two low-valent cobalt species: a Co(I) species that activates the aryl halide, and a Co(0) species that facilitates the cleavage of the aryl–CN bond. Consistent with earlier findings by Chatani et al. in rhodium catalysis [41], an intramolecular version of this transformation was also shown to be feasible, albeit requiring prolonged reaction times.

1.2. Formation of vinyl arenes

Although Heck et al. initially reported the formation of styrene in low yield from vinyl acetate, via palladium catalysis, the first efficient XEC between an aryl and a vinyl compound was achieved through electrosynthesis using a sacrificial anode and cobalt catalysis. This approach enabled, for the first time, the use of vinyl acetates as reagents, compounds that are readily accessible from abundant carbonyl precursors, inexpensive, stable, and environmentally benign.

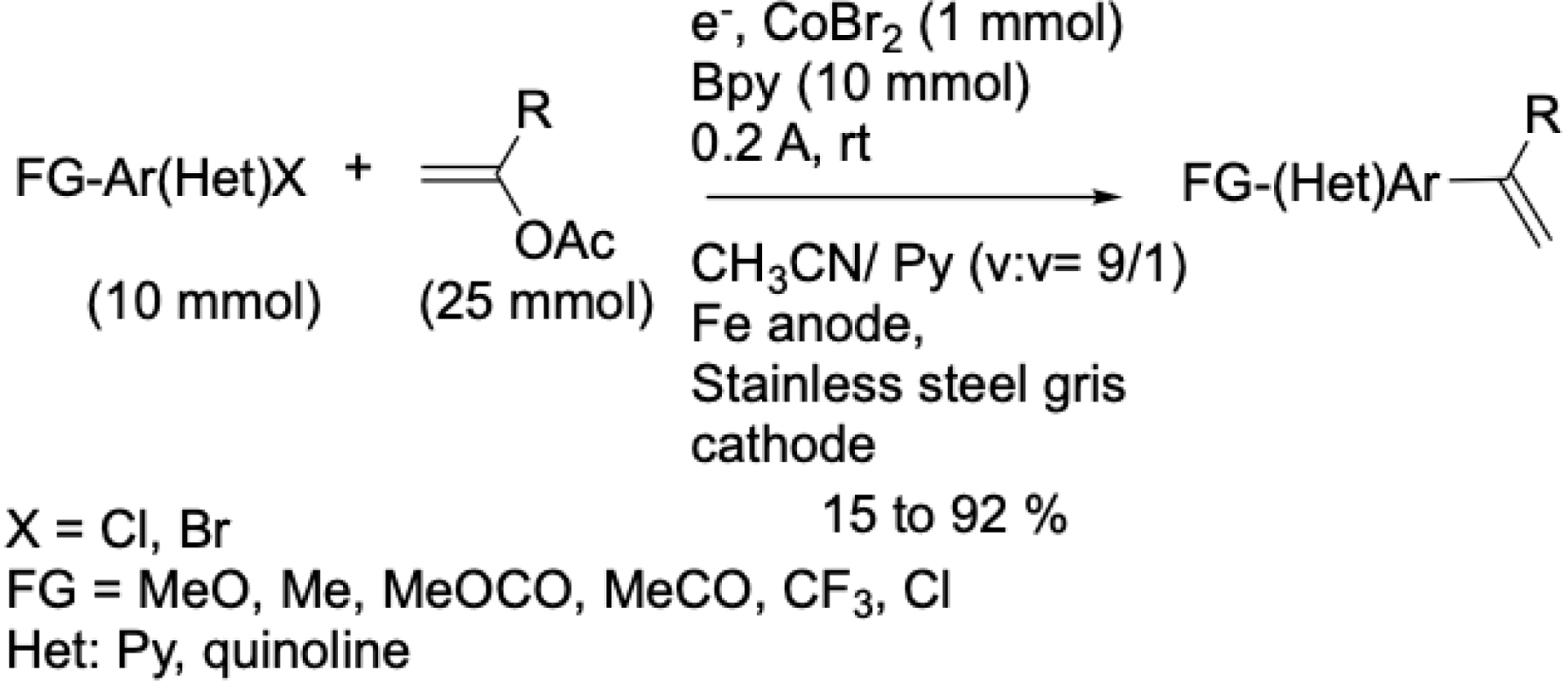

Although being considered highly attractive alkenyl reagents, vinyl acetates are rarely employed due to their low intrinsic reactivity. Daves and Arai described the first direct Pd-catalyzed vinylation starting from vinyl acetate and iodo compounds. However, poor yields were obtained [42, 43]. Our group was the first to report a cobalt-catalyzed electrochemical vinylation of aryl halides using vinyl acetates (Scheme 6). This reaction was performed in an undivided cell equipped with an iron anode and a mixture of acetonitrile/pyridine [44]. This method afforded good to excellent yields, although it required a stoichiometric amount of bipyridine, which remains a notable limitation.

Cobalt-catalyzed electrochemical vinylation of aryl halides using vinylic acetates.

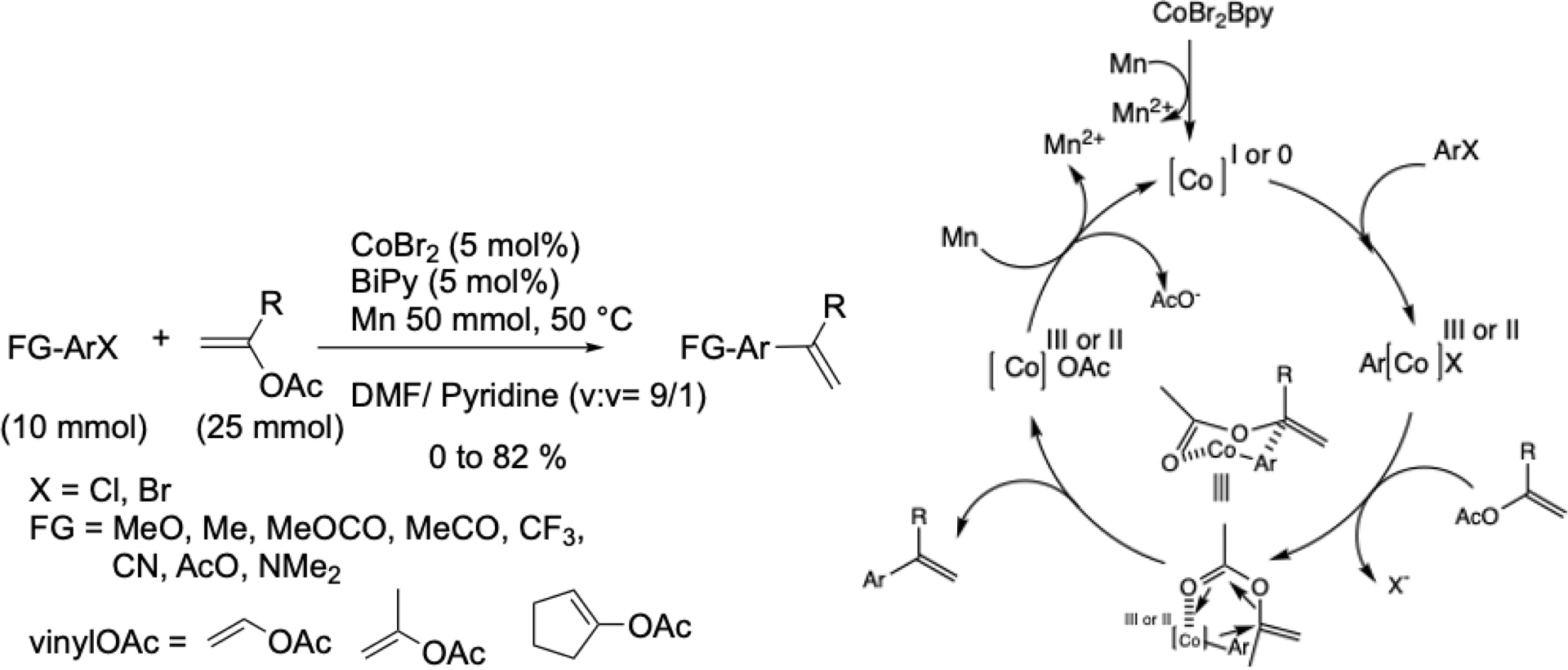

In 2005, we adapted this transformation to a conventional chemical method using manganese as the reductant, this time employing only a catalytic amount of bipyridine (Scheme 7) [45]. The proposed mechanism involves a six-membered transition state in which the aryl group adds to the more substituted carbon of the double bond.

Cobalt-catalyzed vinylation of functionalized aryl halides with vinyl acetates and proposed mechanism.

Later, Shu et al. described several nickel-catalyzed XECs for C–C bond formation using alkenyl acetates as starting materials [46].

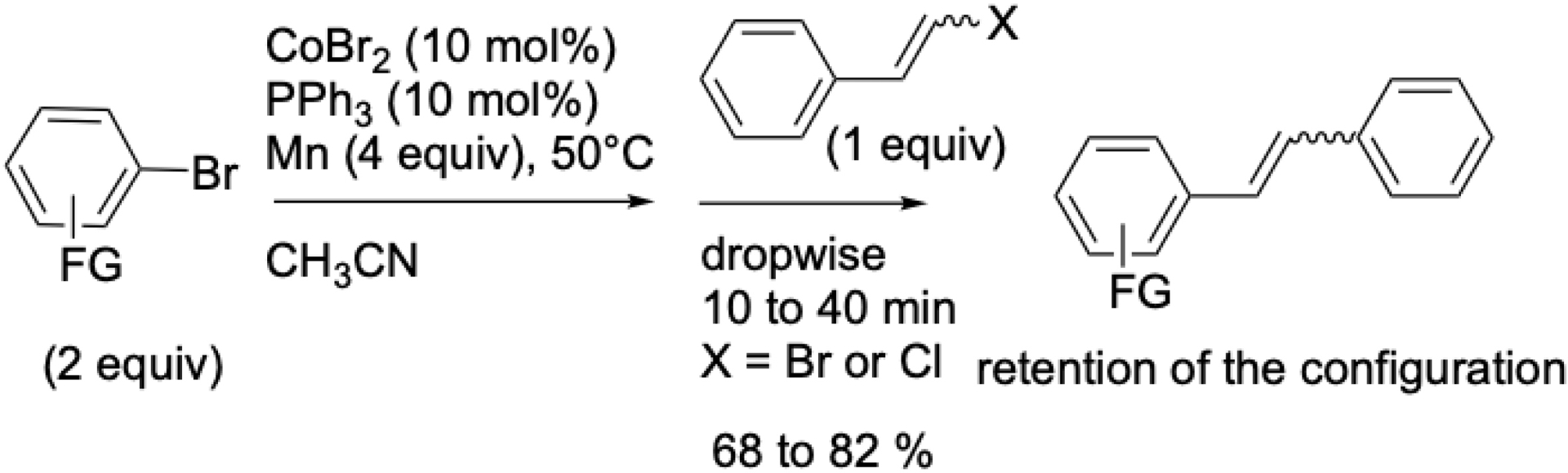

A similar strategy was applied to the synthesis of stilbenes from β-bromostyrenes and aryl halides (Scheme 8) [47]. These compounds are of significant interest due to their presence in the manufacture of industrial dyes, dye lasers, optical brighteners, scintillator, other materials, and a wide range of biologically active molecules, including resveratrol and combretastatin. Stilbenes can be obtained via XEC between aryl halides and bromostyrenes using cobalt catalysis. However, halostyrenes (X = Cl or Br) are more reactive than vinyl acetates and must be added dropwise to prevent dimerization.

Cobalt-catalyzed vinylation of aromatic halides using β-halostyrenes.

Aryl bromides bearing electron-donating or electron-withdrawing groups in the ortho, meta, or para positions afforded good yields. Moreover, this method proceeds with complete retention of the double bond configuration, in contrast to reactions catalyzed by nickel.

1.3. Formation of 1,3-dienes

1,3-Dienes are a prominent class of functional molecules with diverse applications in materials science, natural product synthesis, and pharmaceuticals. Recent years have seen significant progress in both their synthesis and utilization. Beyond classic methods such as the Wittig and Julia reactions, 1,3-dienes can be accessed through elegant transition-metal-catalyzed coupling strategies. This includes palladium-catalyzed Suzuki, Stille, and Heck reactions involving vinyl halides, as well as transformations using alkynes, allenes, and carbenes. Moreover, ruthenium-, iridium-, and palladium-catalyzed processes offer straightforward access to 1,3-dienes as well.

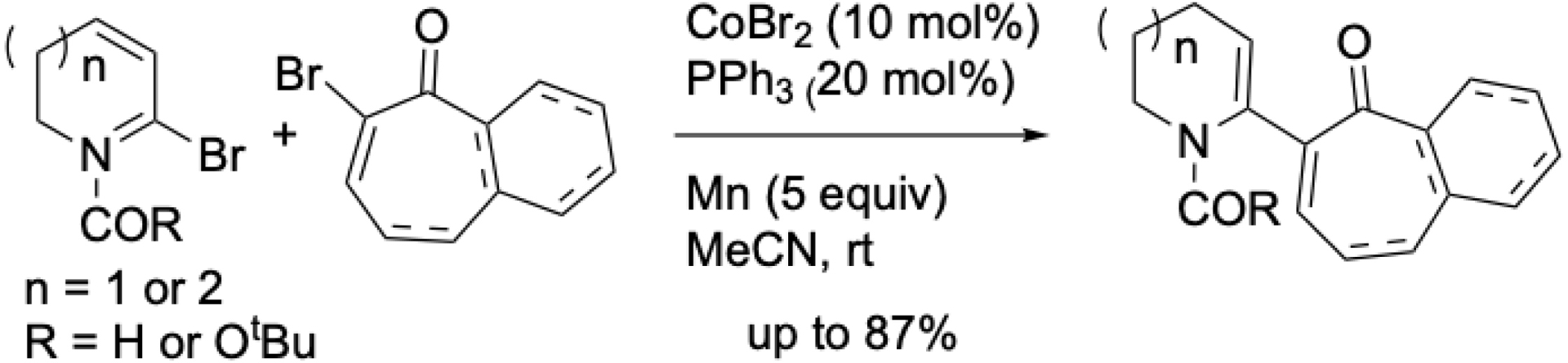

Nickel-catalyzed XECs developed by Gong and Shu et al. allow the formation of vinyl–vinyl frameworks from vinyl halides and vinyl triflates, or between two vinyl halides [48, 49]. While cobalt-catalyzed couplings using vinyl Grignard or vinyl zinc reagents with vinyl halides, triflates, or acetates have been reported, the only cobalt-catalyzed XEC between two vinyl compounds was described by Beng et al., involving α-bromo enones and α-bromo enamides for the synthesis of azepanes, piperidines, and benzotropones (Scheme 9) [50].

Access to functionalized benzotropones, azepanes, and piperidines by reductive cross-coupling of α-bromo enones with α-bromo enamides.

2. Formation of C(sp2)–C(sp3) bonds

The earliest cobalt-catalyzed XEC leading to a Csp2–Csp3 bond formation was achieved via electrosynthesis, similar to nickel-based systems.

2.1. Coupling of aryl halides with allylic compounds

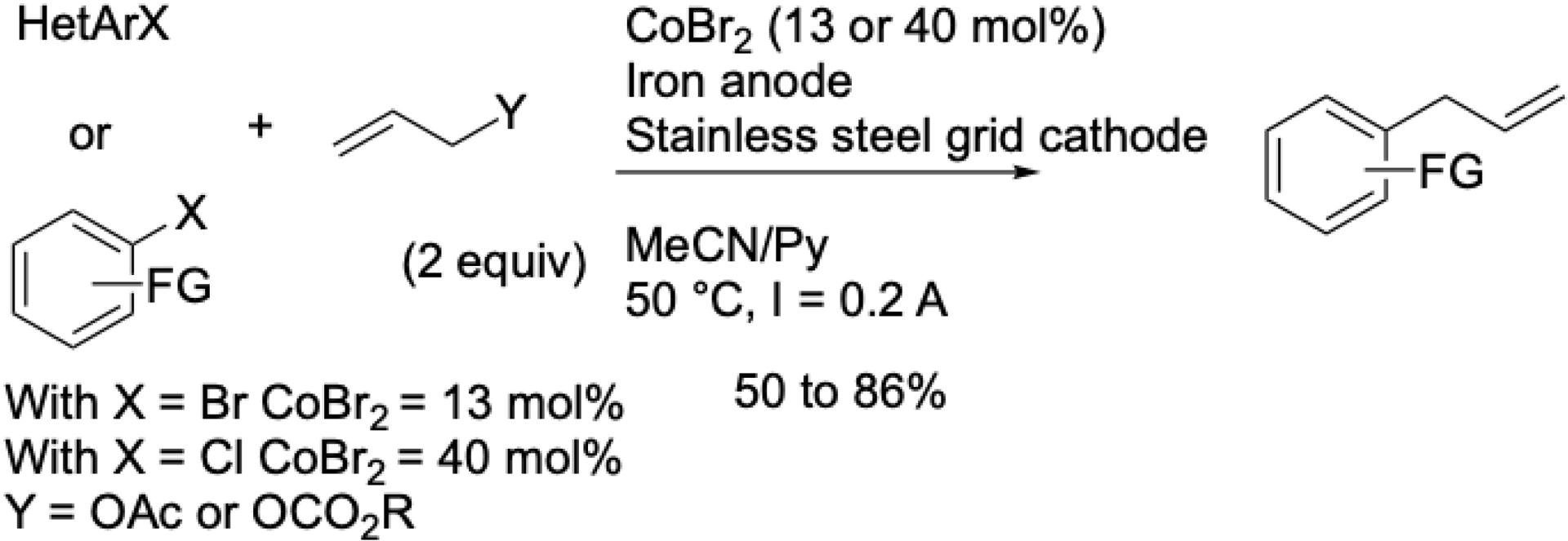

This initial transformation involving aryl halides and allyl acetates was reported by electrosynthesis. Unlike nickel catalysis, which required dropwise addition of reactive allyl chlorides or acetate [51], the cobalt system allowed the addition of allyl acetates at the beginning of the reaction, simplifying the procedure. The reaction was conducted in an undivided cell with an iron anode, using cobalt bromide as the catalyst in acetonitrile/pyridine (Scheme 10) [52].

Cobalt-catalyzed electrochemical coupling between aromatic halides and allylic acetates.

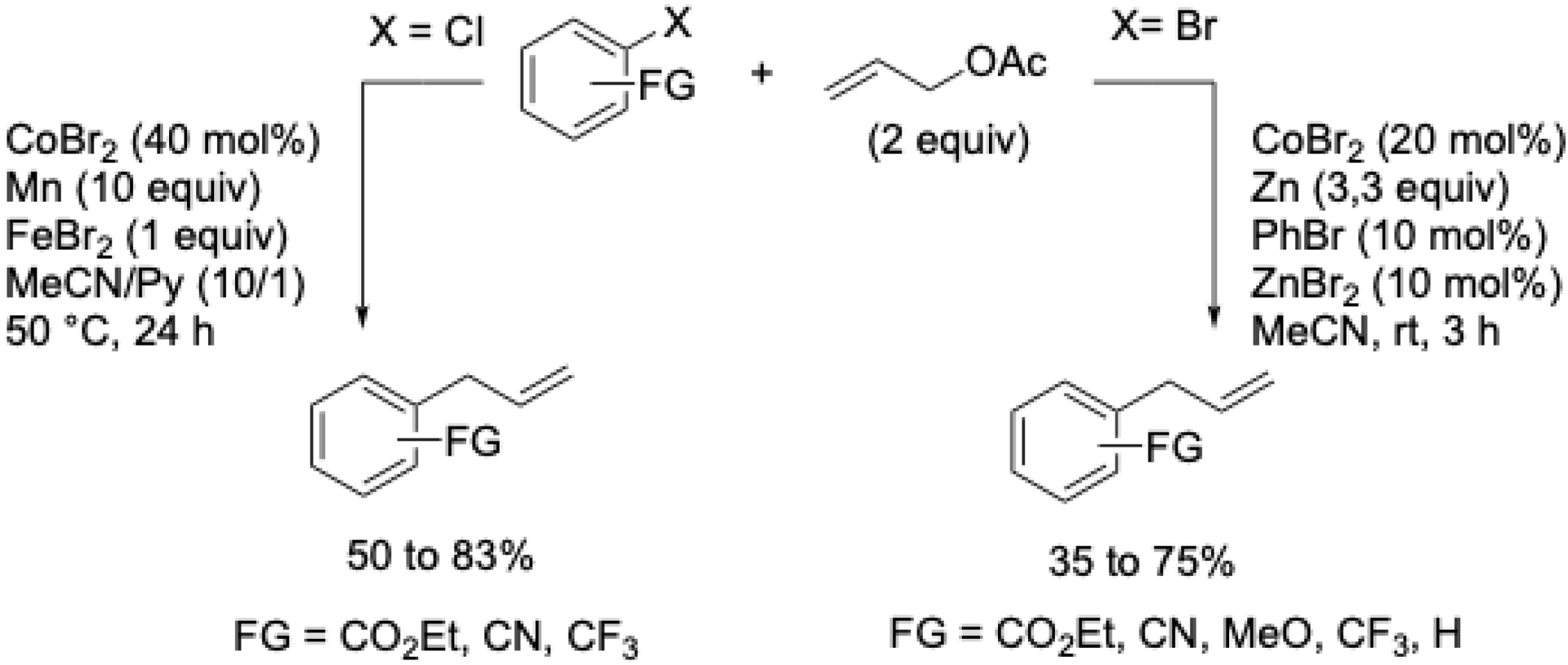

Aryl bromides bearing electron-donating or -withdrawing groups in ortho, meta, or para positions were well tolerated. In contrast, aryl chlorides required electron-withdrawing substituents. Heteroaryl substrates such as bromothiophenes or chloroquinaldines were also compatible. Remarkably, unlike many other methods, the major product was the linear isomer. This electrochemical synthesis was patented in 2001 [53]. Due to the perceived complexity of electrochemical methods at the time, we later developed a conventional chemical variant. Although this reaction was the first XEC involving a non-noble metal, yields were lower with substituted allyl acetates compared to the electrochemical approach [54]. Depending on the nature of the halide on aryl moiety, conditions are different (Scheme 11).

Cross-coupling between aryl halides and allylic acetates using a cobalt catalyst.

2.2. Coupling of aryl halides with benzylic compounds

Cobalt catalysis also enables coupling of aryl halides with benzylic compounds. Prior to exploring XECs, Gosmini and Knochel jointly demonstrated that arylzinc [55] or benzylzinc [56] reagents could react with benzyl chlorides or aryl halides, respectively, under cobalt catalysis. However, these methods required the use of preformed organozinc species.

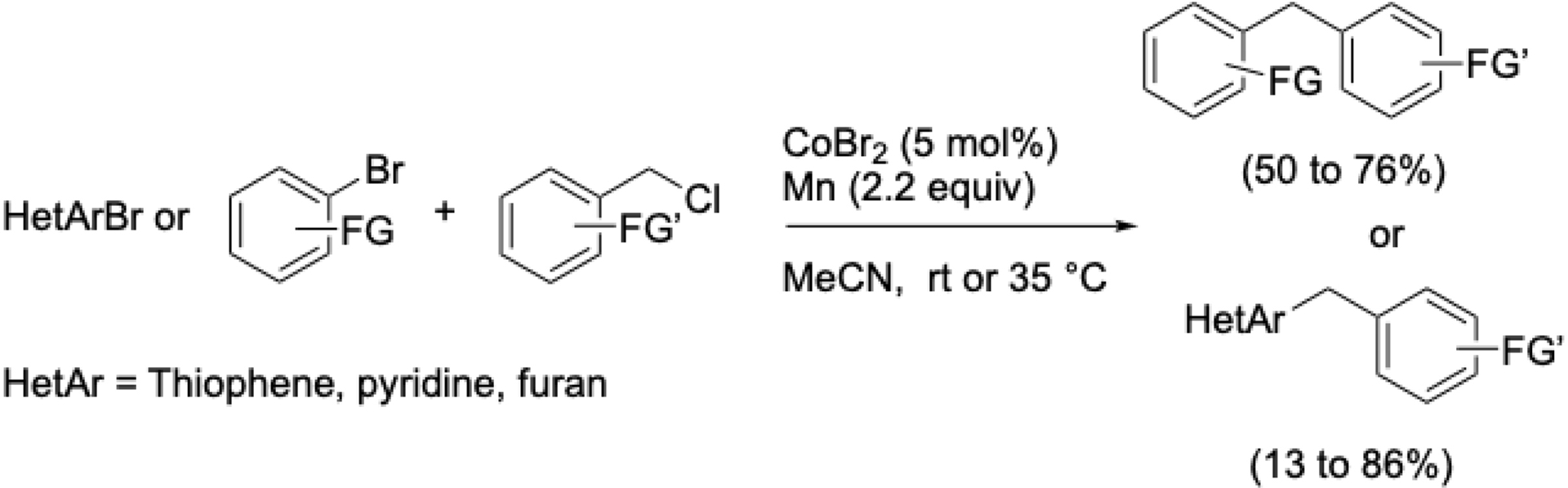

To overcome this limitation, a direct cobalt-catalyzed reductive arylation of benzyl chlorides with aryl halides was developed to synthesize diarylmethanes—key motifs in pharmaceuticals, agrochemicals, and supramolecular chemistry [57]. This protocol, which tolerates a wide range of functional groups, proceeds under mild conditions (rt to 35 °C) in acetonitrile without the need for ligands and uses pyridine as a cosolvent (Scheme 12). Heteroaryl bromides were also successfully employed.

Cross-electrophilic coupling benzyl chlorides and (Het)aryl bromides.

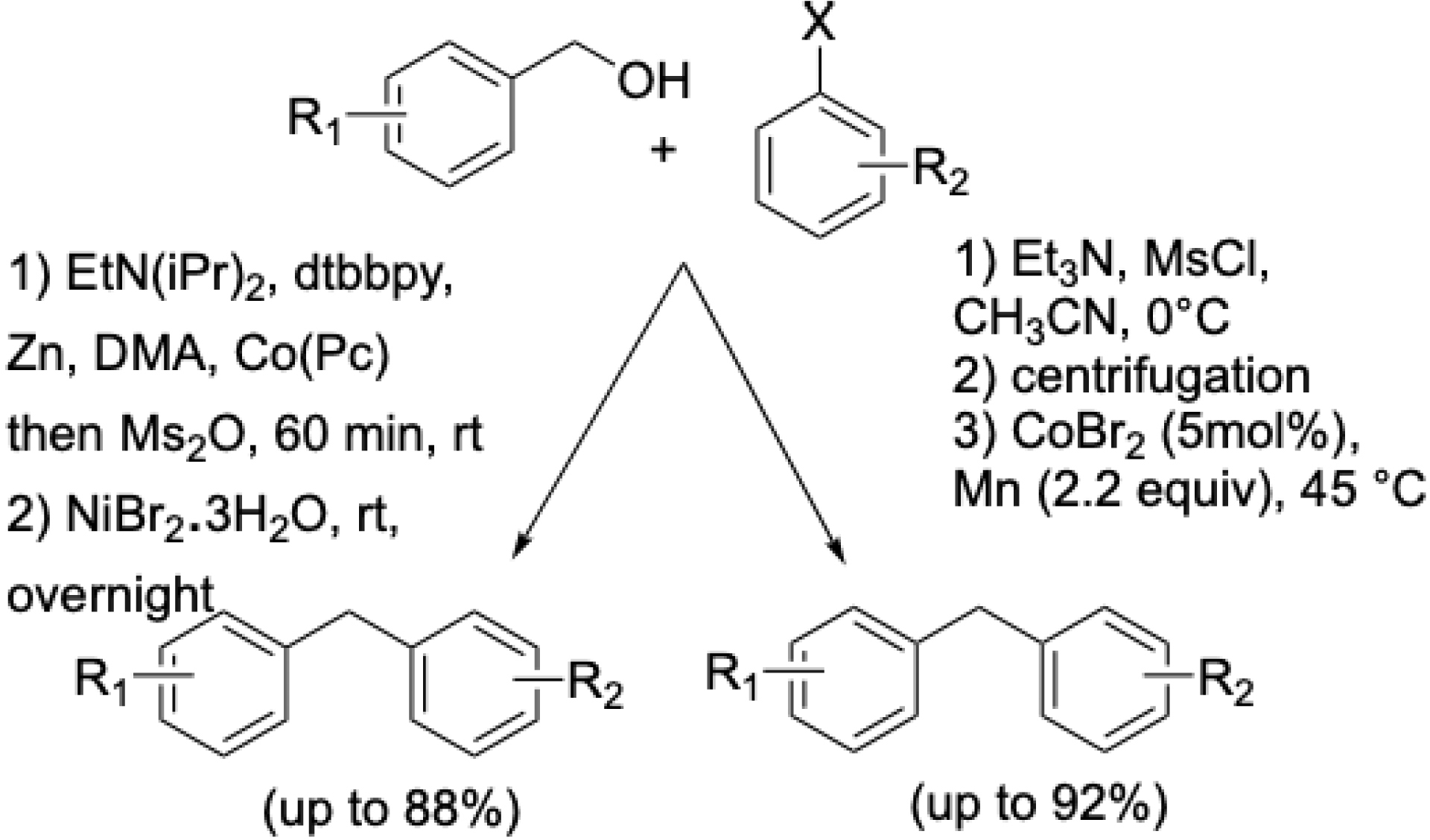

Due to environmental concerns associated with halides, alternative electrophiles are being explored. Weix et al. reported a dual Ni/Co-catalyzed coupling of benzyl mesylates with aryl halides employing cobalt phthalocyanine as a radical precursor [58]. Inspired by this, our team demonstrated that benzyl mesylates—generated in situ from benzylic alcohols—could replace benzyl chlorides using simple cobalt bromide catalysis without ligands (Scheme 13) [59]. This method tolerates various functional groups on both benzyl and aryl moieties.

Ni/Co or Co-catalyzed formation of functionalized diarylmethanes from benzyl alcohols and aryl halides.

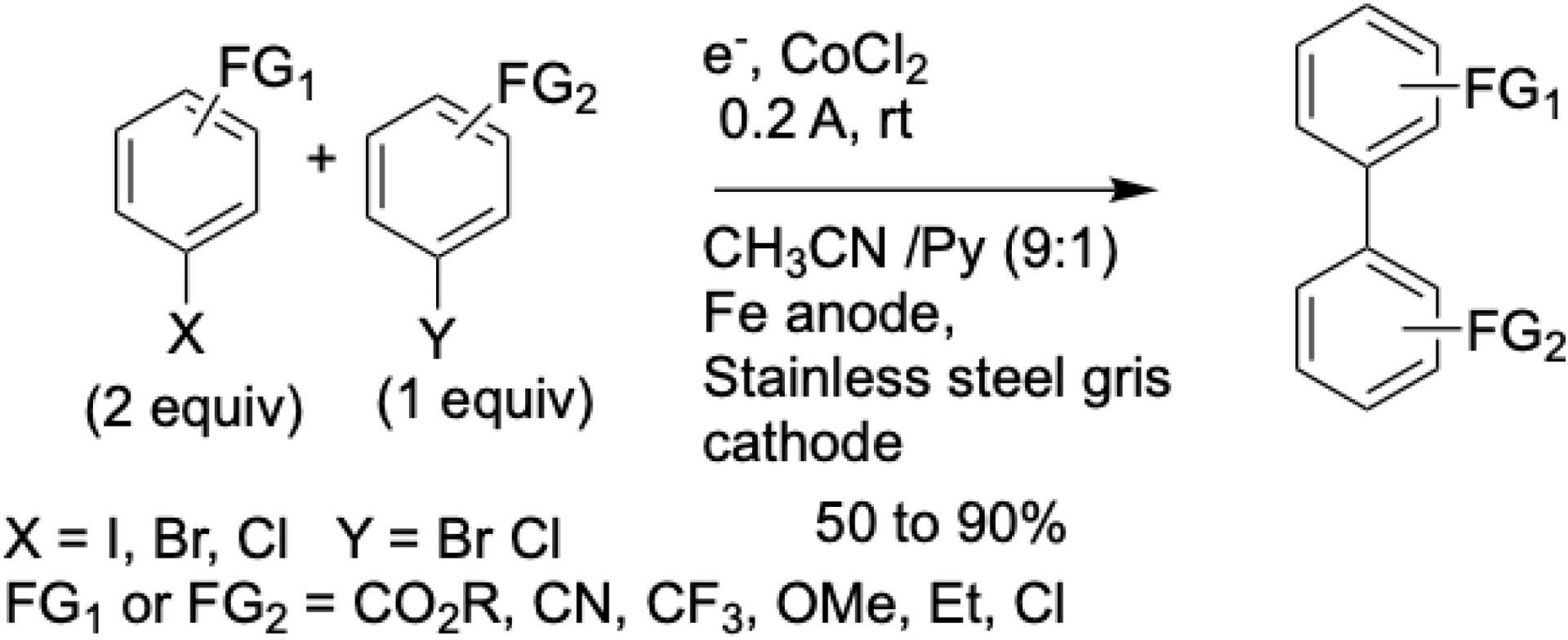

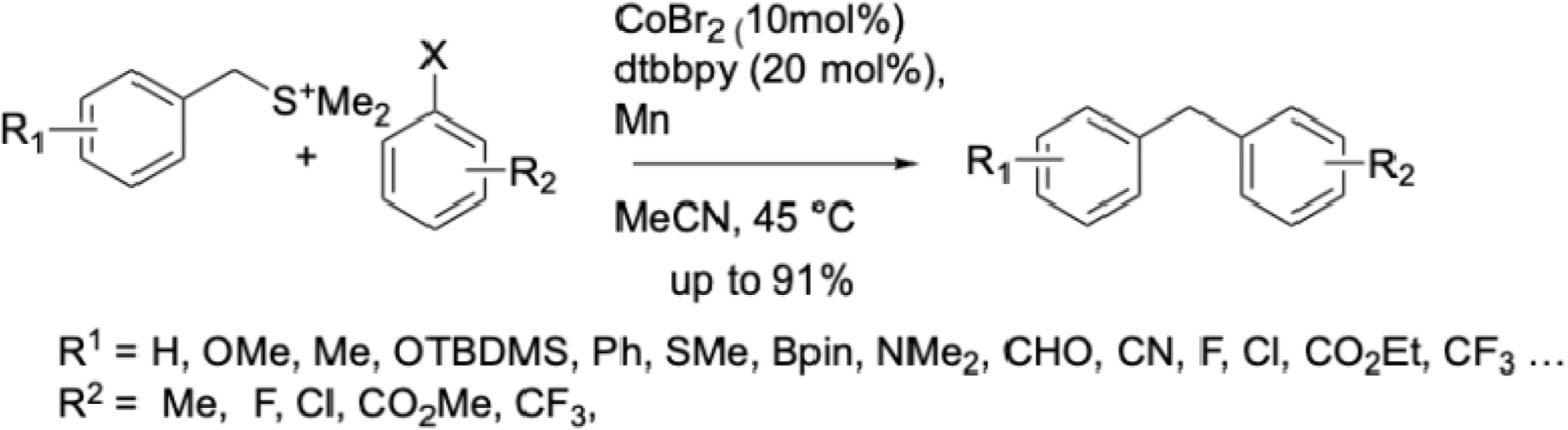

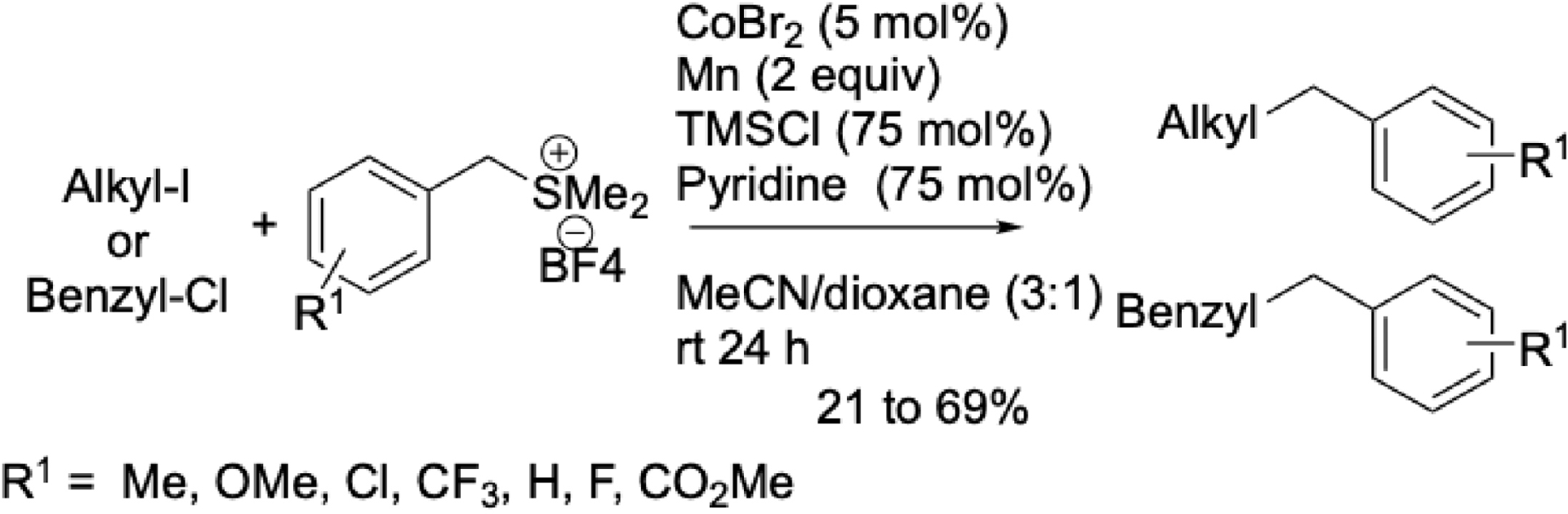

More recently, this strategy was extended to bench-stable benzyl sulfonium salts (Scheme 14) [60]. Under conditions similar to those optimized for mesylates, initial cross-coupling reaction yields were low but improved significantly upon addition of bipyridine. Mechanistic studies suggest that low-valent cobalt activates both aryl halides and C–S bonds via single-electron transfer, generating benzyl radicals.

Synthesis of diarylmethanes by cobalt-catalyzed reductive cross-coupling via Csp3–S bond activation.

2.3. Coupling of aryl halides with non-activated alkyl halides

Earlier studies primarily utilized activated alkyl electrophiles such as benzyl or allyl derivatives. Jacobi von Wangelin et al. used iron or cobalt catalysis in combination with magnesium as a reductant to expand the scope to non-activated alkyl halides. However, the underlying mechanism involves the in situ formation of Grignard reagents, which inherently limits the functional group tolerance of the reaction [61].

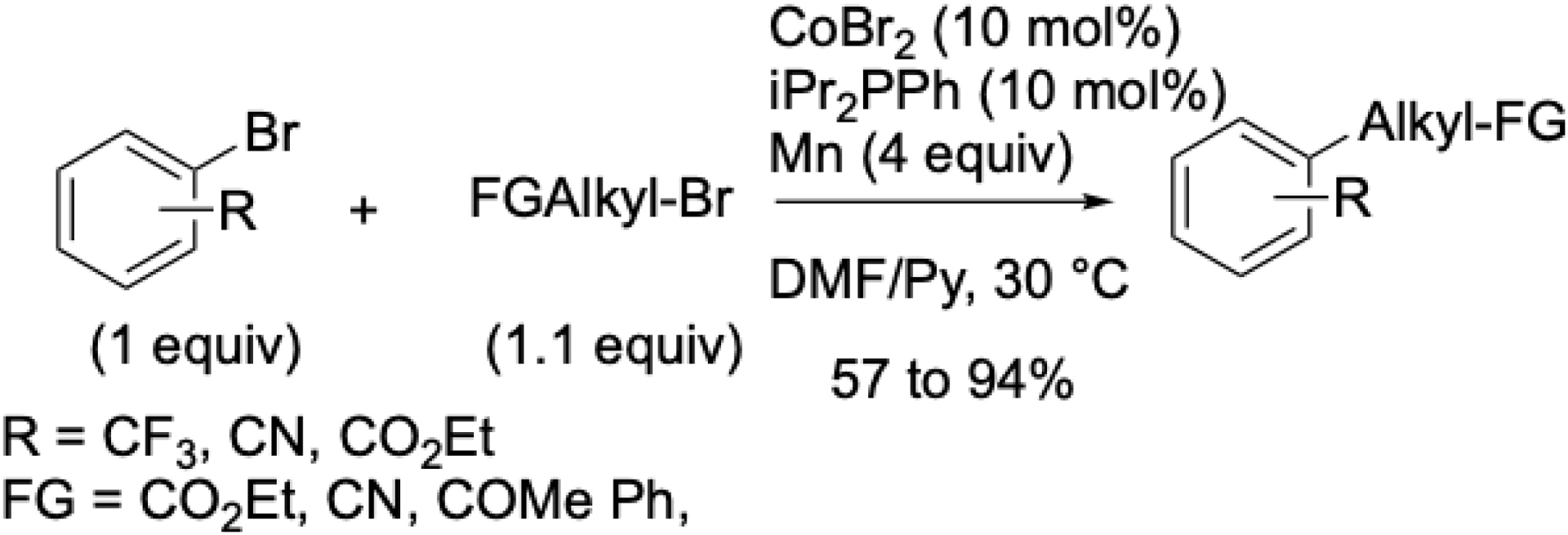

Later, a more versatile system based on CoBr2/iPr2PhP/Mn in DMF/pyridine at 30 °C was developed (Scheme 15). This protocol tolerated functional groups and gave improved yields when using monodentate phosphine ligands, in contrast to bidentate nitrogen ligands. A slight excess of alkyl bromide was required, unlike the stoichiometric amounts typically sufficient for more reactive alkyl partners.

Cobalt-catalyzed alkylation of aryl halides.

The mechanistic hypothesis is similar to other cobalt-catalyzed diarylmethane formation (Scheme 16). The initiating step is the reduction of the Co(II) precatalyst into the active low-valent Co(I) species by manganese. Subsequent oxidative addition to the aryl bromide forms an aryl Co(III) intermediate, which is reduced to arylcobalt(II). At the same time, the reduction of alkyl compound leads to the alkyl radical intermediate. Finally, the alkyl arylcobalt complex, generated from the combination of the alkyl radical and the arylcobalt complex, provides the cross-coupling product by reductive elimination together with the regeneration of the active species Co(I), closing the catalytic cycle.

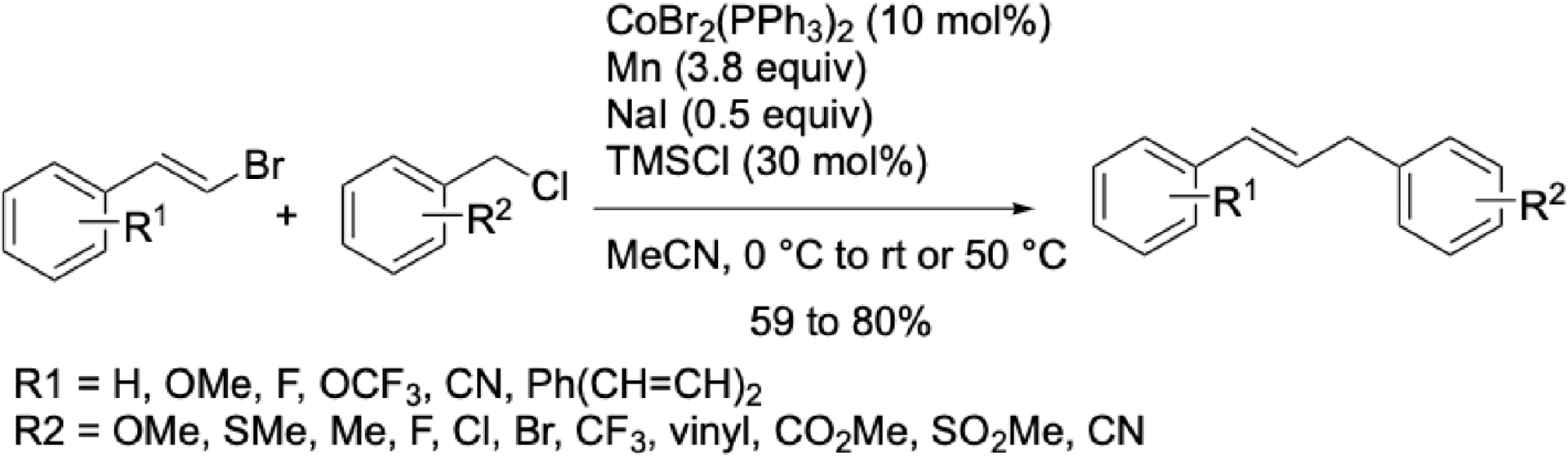

2.4. Coupling of vinyl compounds with benzyl chloride

Beyond aryl partners, vinyl halides can also be coupled with benzyl chlorides. A cobalt/manganese system using CoBr2(PPh3)2 was reported in acetonitrile with NaI as additive (Scheme 17). Electron-withdrawing groups required elevated temperatures (50 °C), while electron-donating groups allowed reactions at 0 °C to room temperature. Lipshutz et al. [62] previously described a similar transformation using palladium without organic solvents. More recently, Reisman and Cherney [63] developed an enantioselective nickel-catalyzed cross-coupling of secondary benzyl chlorides with styrenyl bromides. However, their method was not stereospecific: Z-alkenyl bromides yielded exclusively E-products. In contrast, the cobalt/manganese system preserved the stereochemistry of the starting material.

Cobalt-catalyzed reductive cross-coupling between styryl and benzyl halides.

3. Formation of C(sp3)–C(sp3) bonds

Reductive cross-coupling between two alkyl electrophiles has emerged as a powerful strategy for constructing C(sp3)–C(sp3) bonds—a long-standing challenge in organic synthesis due to issues such as β-hydride elimination and the control of the selectivity. While nickel catalysis has traditionally dominated this field, cobalt has recently gained attention as a sustainable and versatile alternative, offering distinct reactivity profiles.

Historically, the Wurtz reaction was one of the earliest alkyl–alkyl coupling methods. However, it was limited to the synthesis of symmetrical alkanes due to uncontrolled radical formation. More modern approaches involve the cross-coupling of alkylmetals with alkyl halides, typically catalyzed by palladium or nickel. Yet, when using non-activated alkyl halides, undesired β-hydride elimination often occurs due to slow reductive elimination, especially in the absence of bulky electron-rich phosphine or N-heterocyclic carbenes (NHC) ligands.

Nickel-catalyzed XECs have shown promise in suppressing β-hydride elimination by leveraging low-valent metal centers under reducing conditions [64]. However, cobalt catalysis offers complementary advantages, including broader functional group tolerance and enhanced radical reactivity.

Cobalt complexes stabilized by ligands such as bipyridines, phenanthrolines, or salen-type frameworks can mediate the coupling of two unactivated alkyl halides in the presence of external reductants like zinc or manganese. Alternatively, electrochemical reduction can generate low-valent cobalt species in situ, eliminating the need for sacrificial metals.

A key advantage of cobalt catalysis is its ability to suppress homocoupling and promote cross-coupling selectivity, particularly when using sterically or electronically differentiated electrophiles. Unlike palladium, cobalt catalysts are more effective in radical-mediated pathways and exhibit higher tolerance to functional groups.

3.1. Coupling of alkyl halides with allyl acetates

While cobalt-catalyzed homocoupling of non-activated alkyl halides has been reported [65], heterocoupling has also been achieved—either between an activated and a non-activated alkyl electrophile, or between two activated alkyl species such as benzyl or allyl compounds.

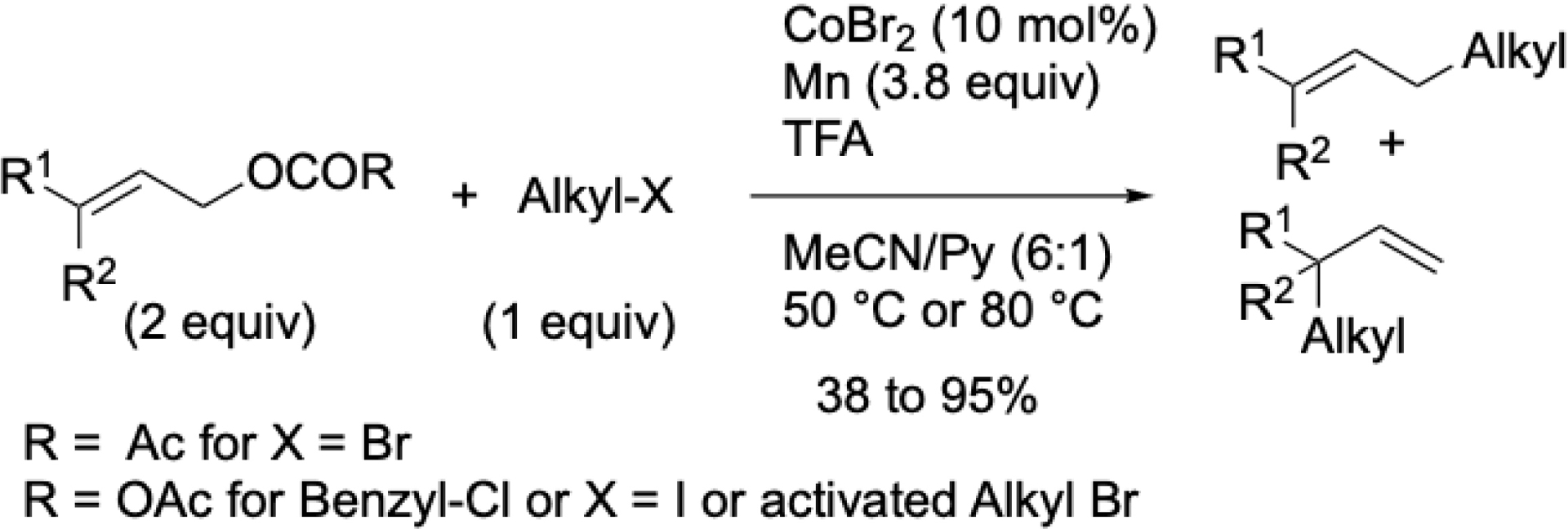

In 2011, we reported the first reductive cobalt-catalyzed Csp3–Csp3 formation by describing the allylation of alkyl halides using either allyl acetates or allyl carbonates, depending on the nature of the alkyl halide (Scheme 18) [66]. The reaction was effective with primary, secondary, and tertiary alkyl substrates and was conducted in a mixture of acetonitrile and pyridine.

Co-catalyzed reductive allylation of alkyl halides with allylic acetates and carbonates.

For reactive alkyl halides such as benzyl chlorides, alkyl iodides, or alkyl bromides bearing β-electron-withdrawing groups, more reactive allyl carbonates were preferred over acetates, and the reaction temperature was lowered to 50 °C (versus 80 °C). With substituted allyl compounds, the linear product was consistently favored. Experimental evidence supported the involvement of alkyl radical intermediates.

3.2. Coupling of activated alkyl compounds with allylic compounds

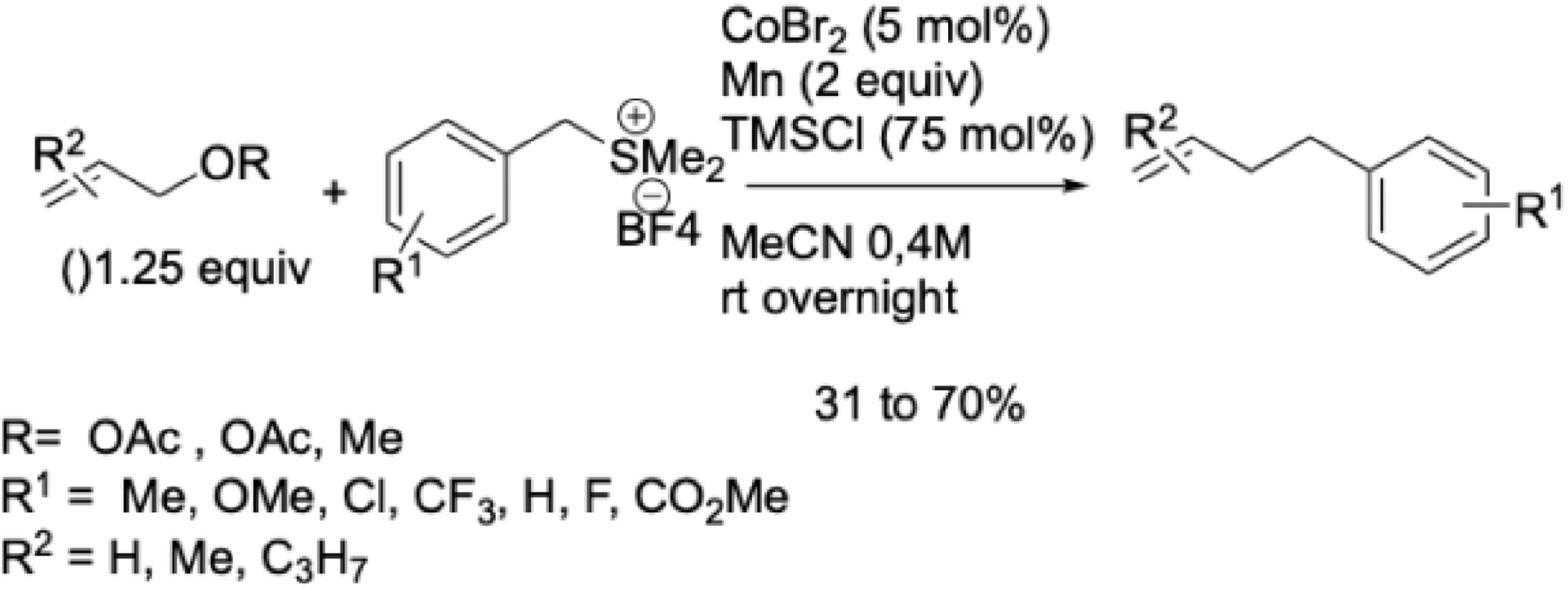

More recently, the cobalt-catalyzed reductive alkylation was extended to other activated alkyl electrophiles, including benzyl sulfonium salts and Katritzky pyridinium salts, and XEC of benzyl sulfonium salts with O-allyl electrophiles, using simple CoBr2 and Mn as reductant in acetonitrile without ligands, was demonstrated (Scheme 19) [67]. This system activated both C–S bonds (from sulfonium salts) and C–O bonds (from allyl esters or ethers), enabling the synthesis of functionalized alkyl–olefinic compounds in moderate to good yields. Notably, these reactions involved two non-halogenated electrophiles—a first in cobalt-catalyzed C–C bond formation.

Co-catalyzed cross-electrophile couplings of benzyl sulfonium salts with allyl esters or ethers.

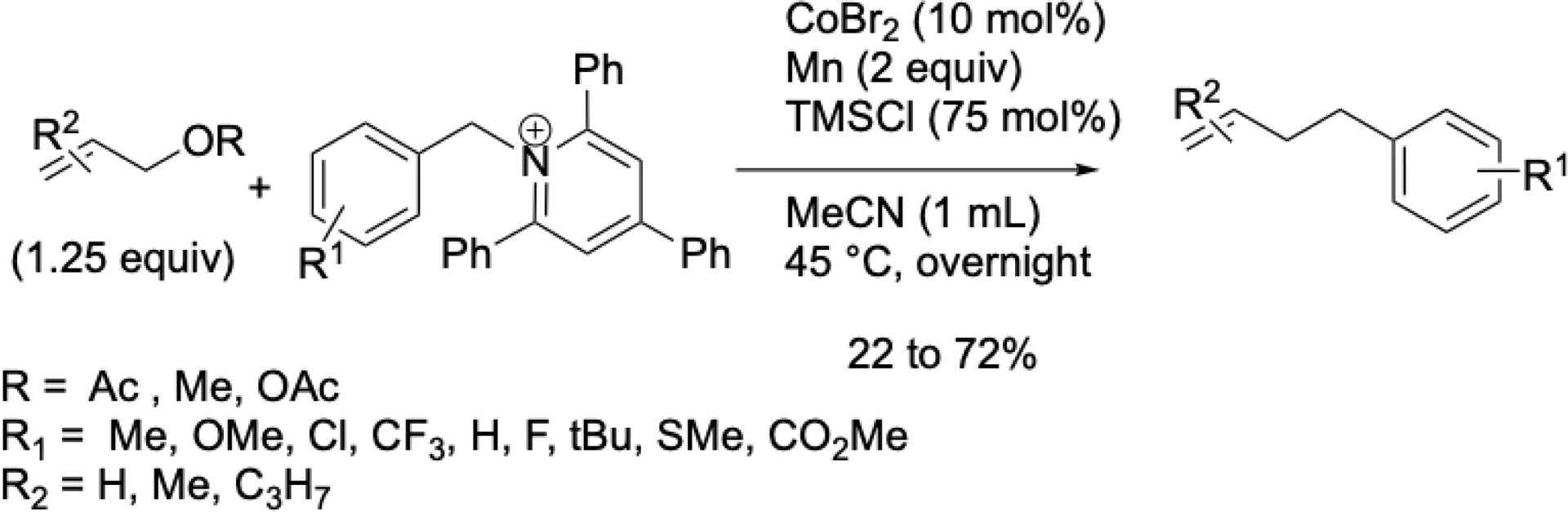

While nickel-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions with Katritzky salts had been described by Watson et al., Ni et al., and Rueping et al. [68, 69, 70], they typically involved alkyl metals or aryl halides. The only cobalt-catalyzed variant was reported by Kojima and Matsunaga et al. via cobalt/organophotoredox dual catalysis, but it was limited to secondary alkyl pyridinium salts [71]. A similar transformation using benzylic Katritzky salts was also reported [72]. This method offers a simple and efficient alternative for synthesizing allyl–benzyl derivatives, using CoBr2, under mild conditions (Scheme 20). The reaction was also applicable to allyl alkyl ethers, as previously shown with benzyl sulfonium salts. Mechanistic studies suggest the formation of benzyl radicals from pyridinium or sulfonium salts, and π-allylcobalt intermediates from allyl compounds.

Cobalt-catalyzed cross-electrophile couplings of benzyl Katritzky salts with allyl esters or ethers.

Benzyl sulfonium salts were also shown to couple with benzyl chlorides or alkyl iodides, yielding functionalized alkyl derivatives [73] (Scheme 21). Preliminary mechanistic investigations suggest the involvement of two radical species—one from the sulfonium salt and the other from the alkyl halide.

Cobalt-catalyzed cross-electrophile couplings of benzyl sulfonium salts with alkyl iodides or benzyl chlorides.

4. Conclusion

Cobalt-catalyzed reductive cross-coupling, also known as cross-electrophile coupling (XEC), represents a powerful and sustainable approach for constructing C(sp2)–C(sp2), C(sp2)–C(sp3), and C(sp3)–C(sp3) bonds from readily available precursors. This method stands out for its ability to activate non-halogenated electrophiles (e.g., C–O, C–S, or C–N bonds), its broad functional group tolerance, and its compatibility with mild conditions. Importantly, it circumvents the need for stoichiometric organometallic reagents that are typically required in traditional approaches. Although cobalt was the first catalyst used to achieve efficient chemical XECs, its applications remain less explored than those of nickel. Continued advances in catalyst design, mechanistic insight, reaction scope, and integration with electrochemical and/or photochemical methods are expected to unlock the full potential of cobalt catalysis in modern synthetic chemistry.

Declaration of interests

The author does not work for, advise, own shares in, or receive funds from any organization that could benefit from this article, and has declared no affiliations other than their research organization.

CC-BY 4.0

CC-BY 4.0