1. Introduction

Lectins are proteins that specifically recognize and bind to carbohydrates, including glycoconjugates present on the surface of all living cells [1]. These glycans participate in a wide range of biological processes, most of which are mediated through the recognition of the so-called glycocode by protein readers [2]. Indeed, the structural diversity of monosaccharides, their linkages, and conformational states provide an optimal system for signal transmission. The evolutionary expansion of glycan complexity, driven by the diversification of biosynthetic enzymes, has been paralleled by the emergence of a broad repertoire of glycan-binding proteins (GBPs), including lectins, capable of mediating both physiological and pathological functions [3].

Traditionally, lectins are defined as proteins that bind specifically to certain sugars and thereby cause agglutination of particular cell types [4]. This definition excludes both enzymes and antibodies of the adaptive immune system. Lectins can exist as soluble proteins or as modules integrated into larger proteins, where their primary function is to engage glycan targets. In pathogenic bacteria, for example, adhesins act as virulence factors by mediating attachment to host surfaces, often through pili or flagella that incorporate one or more lectin domains [5]. Similarly, many bacterial toxins, such as those responsible for cholera or tetanus, require glycan recognition for binding to host membranes prior to cell entry or membrane disruption [6]. Because lectins frequently present multiple binding sites, achieved either through oligomerization or tandem repeats, they are often called agglutinins. While the affinity of a single binding site is typically low, this is compensated by multivalency, resulting in strong avidity (the so-called Velcro effect) when glycans are presented in multiple copies [7].

Blocking lectin–glycan interactions can interfere with infection processes and biofilm formation. As such, lectins are increasingly recognized as promising targets for the development of pathoblockers [8]. These compounds are designed to inhibit virulence factors or other pathogenic mechanisms without affecting bacterial viability. By targeting processes such as adhesion, invasion, quorum sensing, and biofilm formation, pathoblockers disarm pathogens rather than kill them. This approach exerts minimal selective pressure, thereby reducing the risk of resistance development, while preserving the beneficial commensal microbiota. Pathoblockers are now considered as alternative, or more likely adjunctive, therapies alongside antibiotics, and hold significant promise in the fight against multidrug-resistant pathogens [9].

2. Structural information on lectins from pathogens involved in airway infections

The airway epithelium is covered by a dense glycocalyx composed of O-glycosylated mucins, N-glycoproteins, and glycolipids. The composition and frequency of glycan epitopes in the respiratory tract vary according to tissue type, with notable differences in the sialylated glycans expressed in the upper versus lower airways [10]. Glycan signatures are also altered in certain pathologies: for instance, cystic fibrosis is associated with abnormally thick mucus and modification of the relative abundance of sialic acid and fucose residues [11]. From the nasal epithelium to the alveoli, the respiratory tract constitutes the primary entry point for numerous airborne pathogens, which can lead to life-threatening diseases such as tuberculosis or Middle East Respiratory Syndrome. Many of these pathogens are hospital-associated and exhibit multidrug resistance, including Pseudomonas aeruginosa [12] and members of the Burkholderia cepacia complex (BCC) [13]. Emerging fungal infections further exacerbate this burden, as they are often characterized by increasing antifungal resistance and delayed diagnosis.

While mucins play a protective role by trapping pathogens, many microorganisms have evolved mechanisms to exploit host glycans in order to colonize and invade airway tissues. Lectins, in particular, play a central role in these processes, mediating specific recognition of epithelial glycans and thereby facilitating infection or biofilm formation. A summary of lectins implicated in airway infections, together with their specificities and structural data, is provided in Table 1.

Lectins from pathogens responsible for airway infections with available structural data

| Species | Lectins | Structural class | Monosaccharide specificity | PDB code |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteria | ||||

| Bordetella pertussis | PTX | AB5 toxin | NeuAc | 1PTO |

| Burkholderia ambifaria | BambL | β-propeller | Fuc | 3ZW0 |

| Burkholderia cenocepacia | Bc2L-A, Bc2L-C-Cter Bc2L-C-Nter | 2-calcium lectin TNFα-like | Man Fuc |

2VNV 3WQ4 |

| Mycoplasma pneumoniae | P40/P90 adhesin | Mycoplasma adhesin | NeuAc | 6TLZ |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Pyocin LecA/PA-IL LecB/PA-IIL | Monocot-lectin like 1-calcium lectin 2-calcium lectin | Man αGal Fuc |

4LEA 1OKO 1GZT |

| Yersinia pestis | PsaA | Bacterial adhesin | Gal | 2HB0 |

| Fungi | ||||

| Aspergillus fumigatus | AFL1/FleA | β-propeller | Fuc | 4AGI |

| Scedosporium apiospermum | SapL1 | β-propeller | Fuc | 6TRV |

| Viruses | ||||

| Human coronavirus (HCoV) MERS-CoV SARS-CoV-2 | Spike glycoprotein | Coronavirus spike protein | 9Ac-NeuAc NeuAc NeuAc |

8OPM 6Q04 7QUR |

| Influenza virus | Hemagglutinin | Influenza hemag | NeuAc | 3HTQ |

Fuc: fucose; Man: mannose, Gal: galactose, NeuAc: N-acetylneuraminic acid; 9Ac-NeuAc: N-acetylneuraminic acid with acetyl group at C9.

The most extensively studied viral lectin is hemagglutinin (HA) from influenza A virus. Sequence variations in HA have resulted in at least 18 subtypes identified across birds and mammals. Importantly, HA specificity underlies the interspecies transmission barrier: avian influenza strains preferentially recognize sialic acid on NeuAc(α2-3)Gal epitopes, whereas human strains target NeuAc(α2-6)Gal receptors [14]. In coronaviruses, the N-terminal domain of the spike glycoprotein contains a galectin-like lectin module. Binding to sialylated glycans is well established in human coronaviruses (HCoVs) [15] and in MERS-CoV [16], where it constitutes a primary receptor-recognition mechanism. Although the lectin domain is structurally conserved in SARS-CoV-2, the sialic acid-binding activity observed in the early Wuhan strain [17] has been lost in subsequent variants [18].

Lectins from fungal opportunistic pathogens also play a central role in host–pathogen interactions. In Aspergillus fumigatus, lectins expressed on both conidia and hyphae bind efficiently to fucosylated glycans on epithelial cells and mucins [19]. A closely related lectin has been characterized in Scedosporium apiospermum, an emerging opportunistic pathogen of growing clinical concern [20]. Both fungi are associated with nosocomial infections and display increasing resistance to antifungal treatments.

Additional structural data are available for lectins from bacterial pathogens causing respiratory diseases, including Bordetella pertussis (whooping cough), Yersinia pestis (plague) [21] and Mycoplasma pneumoniae (atypical pneumonia) [22]. However, the present review focuses on Pseudomonas aeruginosa and species of the Burkholderia cepacia complex. Rather than providing a comprehensive account of efforts to develop high-affinity ligands against microbial lectins, the aim here is to illustrate how structural studies have guided the rational design of active compounds through distinct strategies. This review also highlights how structural and biophysical investigations conducted at the CERMAV center for research on plant macromolecules have fostered a productive dialogue with carbohydrate chemistry groups, ultimately advancing the synthesis of antibacterial pathoblockers effective against P. aeruginosa and different species of Burkholderia.

2.1. Lectins from Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Burkholderia cepacia complex

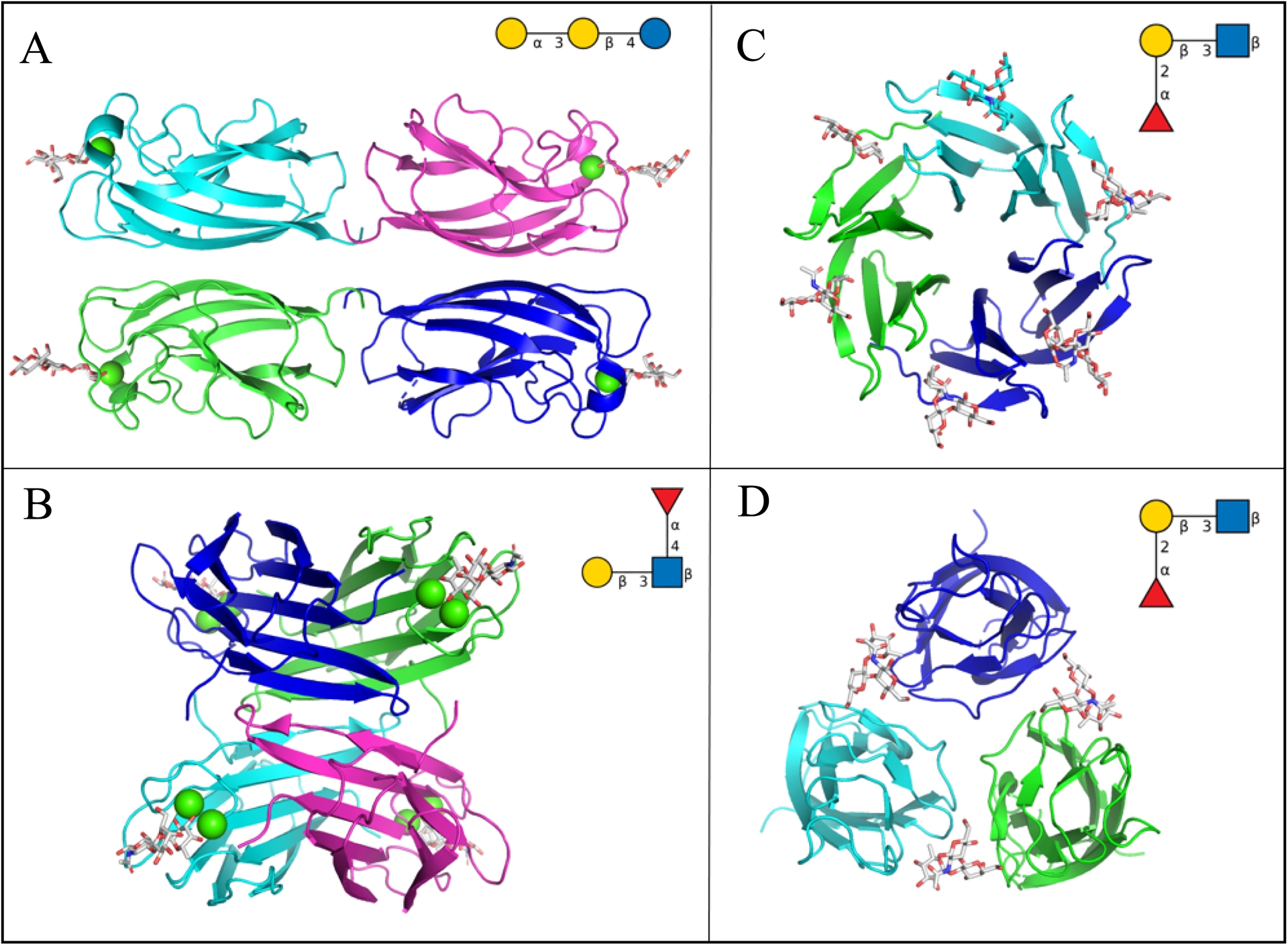

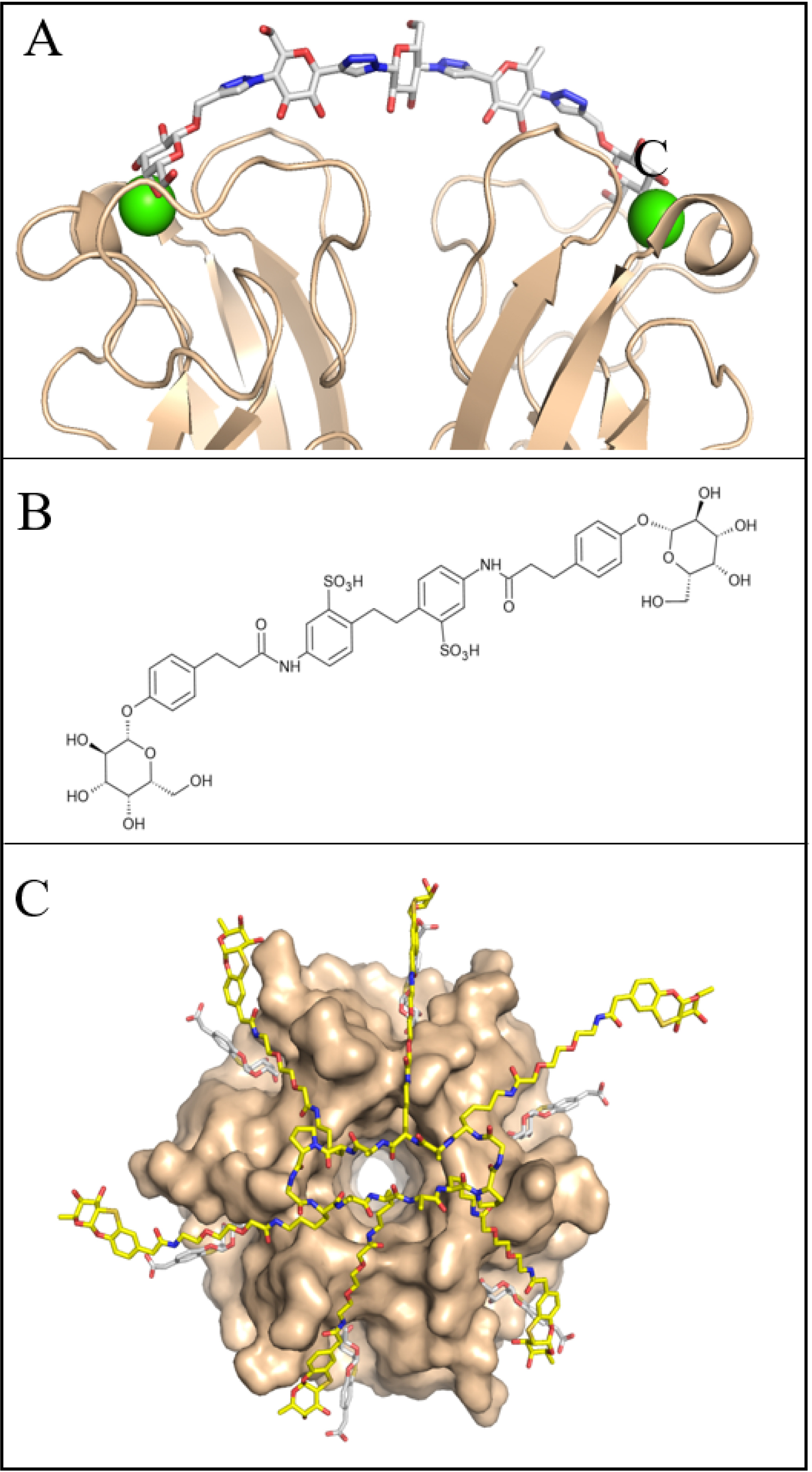

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a ubiquitous opportunistic pathogen associated with severe infections in immunocompromised individuals, particularly in patients with cystic fibrosis and those under mechanical ventilation [24]. It is included in the World Health Organization’s priority list of pathogens due to its critical role in the development of antimicrobial resistance. P. aeruginosa produces several soluble factors, including pyocins, i.e., short peptides with antibacterial activity, and two lectins, LecA and LecB, which are specific for galactose and fucose, respectively [25]. Both lectins are tetrameric and bind monosaccharides through interactions that involve calcium ions [26, 27] (Figure 1A and 1B). LecA binds to host glycolipids, inducing rearrangements of the plasma membrane that not only exert cytotoxic effects but also promote cellular internalization of the bacterium [28]. LecB has a strong preference for Lewis a oligosaccharides but binds broadly to fucose residues on glycoproteins and glycolipids [29]. Both lectins contribute significantly to biofilm formation [30].

Crystal structures of soluble lectins from bacterial pathogens in their oligomeric form and in complex with human glycan epitopes. (A) LecA from P. aeruginosa complexed with iso-Gb3 trisaccharide Gal(α1-3)Gal(β1-4)Glc, PDB 2VXJ. (B) LecB from P. aeruginosa complexed with Lewis a trisaccharide Gal(β1-3)[Fuc(α1-4)]GlcNAc, PDB W8H. (C) BambL from B. ambifaria complexed with H-type 1 trisaccharide Fuc(α1-2)Gal(β1-3)GlcNAc, PDB 3ZW2. (D) Bc2LC-nt from B. cenocepacia complexed with H-type 1 trisaccharide Fuc(α1-2)Gal(β1-3)GlcNAc, PDB 6TID. Proteins are represented by ribbons colored by chains, glycans by sticks, and calcium ions by green spheres (Pymol, Schrödinger). Oligosaccharide ligands are also represented as cartoons using the Symbol Nomenclature for Graphical Representations of Glycans [23] (Gal: yellow circle; Fuc: red triangle; Glc: blue circle, GlcNAc: blue square).

The Burkholderia cepacia complex (BCC) comprises at least twenty distinct Burkholderia species, many of which are clinically important opportunistic pathogens in cystic fibrosis patients [31]. Burkholderia cenocepacia produces several lectins with LecB-like domains, showing specificity for fucose and mannose [32]. Among them, BC2L-C is notable for its modular structure: its N-terminal domain resembles LecB, while its C-terminal domain adopts a tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α-like fold, also with fucose specificity [33] (Figure 1D). In contrast, Burkholderia ambifaria produces a different lectin that assembles into a trimeric β-propeller, exposing six fucose-binding sites [34] (Figure 1C).

2.2. Forces involved in protein–sugar interaction

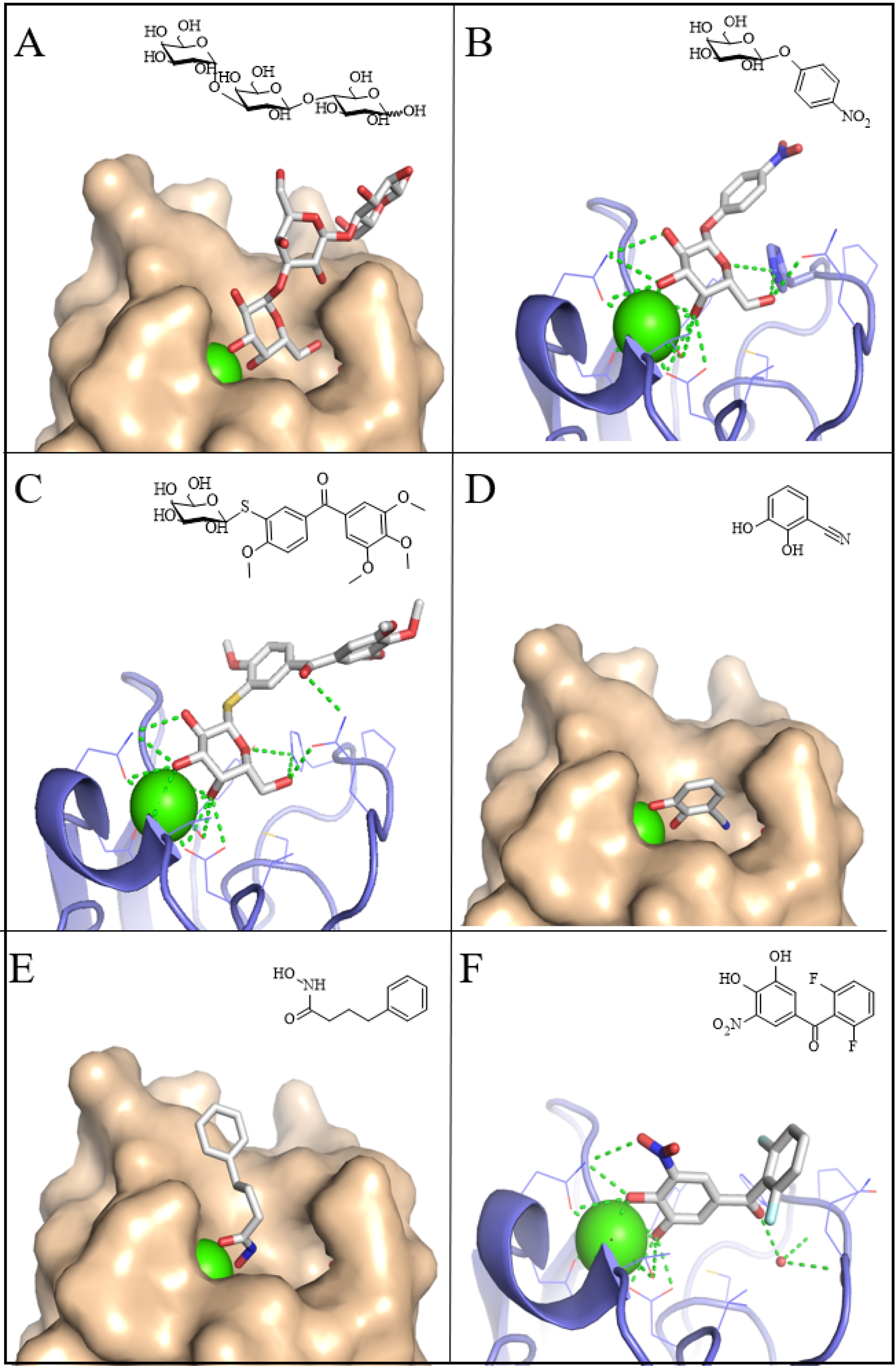

The binding sites of the four lectins discussed in this review are shown in Figure 2, and they exemplify the classical interactions typically observed in protein–carbohydrate recognition. In all cases, hydroxyl groups of the glycans participate in hydrogen bonding with amino acid side chains within the protein binding site. Statistical analyses have shown that among polar amino acids, asparagine and aspartate are preferred, occurring at approximately twice the frequency expected by chance [35]. However, aromatic amino acids are most strongly favored, with a pronounced prevalence of tryptophan, followed by tyrosine and then histidine.

Details of the glycan binding sites of bacterial lectins from crystal structures. (A) LecA/galactose, PDB 1OKO. (B) LecB/fucose, PDB 1GZT. (C) BambL/fucose, PDB 3ZW0. (D) BC2LC-nt/SeMeFuc, PDB 3WQ4. Hydrogen bonds are represented by green dashed lines, calcium ions by green spheres and water molecules as small red balls. Schematic representation of ligands is displayed in the right upper corner of each panel (ChemSketch, ACD/Labs).

This preference is attributed to CH–π interactions, whereby the CH–presenting face of monosaccharides interacts with electron-rich aromatic side chains [36]. For example, fucose interacts with tryptophan in the binding site of BambL (Figure 2C). Additional contacts are often mediated by water molecules that are integral components of the binding site; for instance, water molecule W1 in LecA is consistently observed in crystal structures and forms a hydrogen bond with O6 of the glycan within a small pocket of the protein surface (Figure 2A). The two P. aeruginosa lectins exhibit a nonconventional mode of glycan recognition. In these cases, calcium ions are directly involved in binding: O3 and O4 of galactose in LecA and O2, O3, and O4 in LecB are coordinated by calcium (Figure 2A and 2B). The presence of two calcium ions is unique to this latter lectin class, and a recent neutron diffraction study demonstrated their role in creating low-barrier hydrogen bonds, which contribute to the unusually high affinity of these interactions [37].

3. Strategies for designing high-affinity glycomimetics against lectins from pathogens

The structural information described above served as the basis for the development of high affinity glycomimetics that are able to compete with the binding of the lectins to the glycan targets with the aim of inhibiting the first stage of adhesion, but also biofilm formation. High-affinity glycomimetics are also a strategy for the vectorization of antibiotics [38] and other compounds or for labeling pathogen or biofilms by fluorescent compounds [39].

3.1. Structure-based design of monovalent glycomimetics

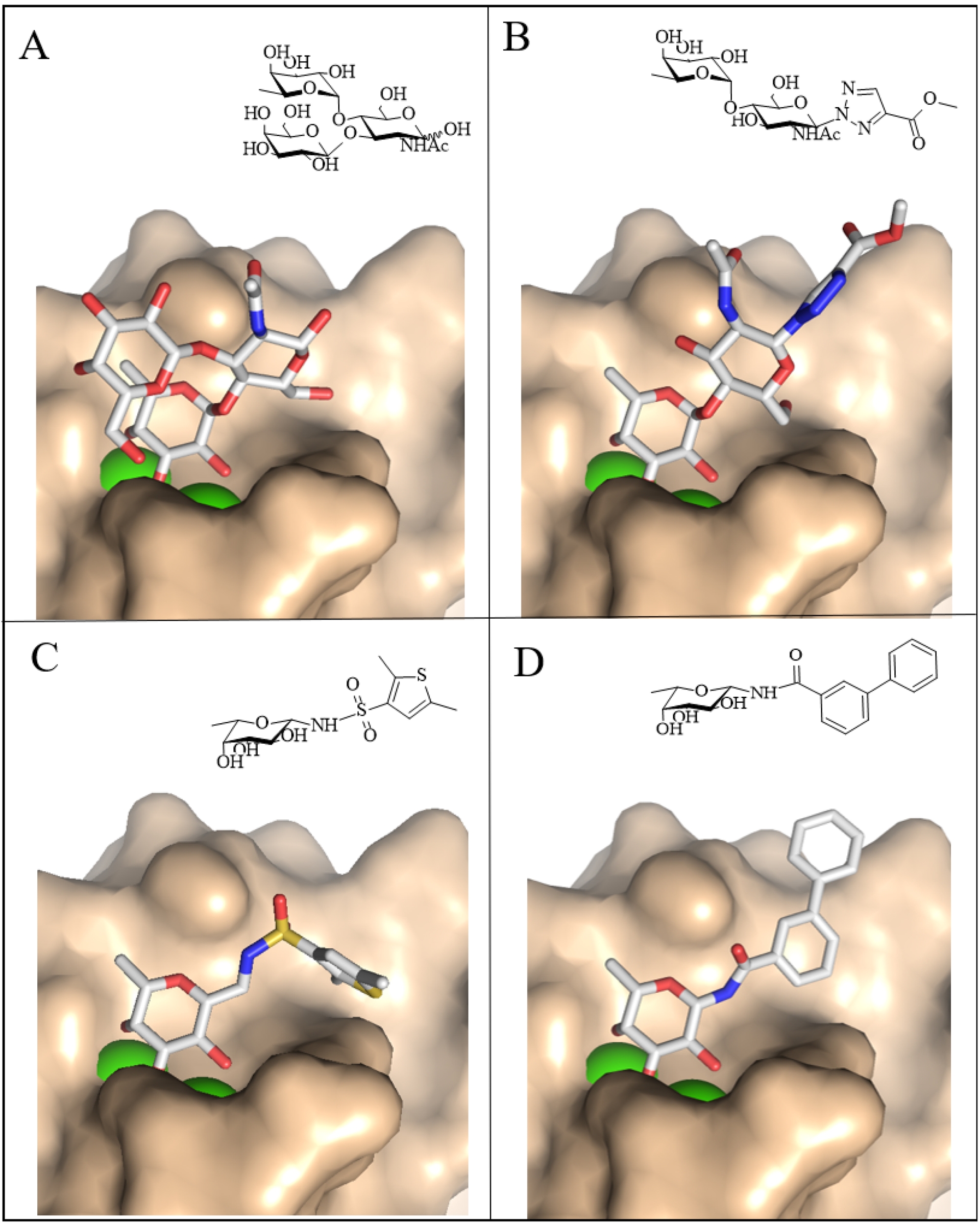

LecA binds to the terminal α-galactose residue present in Gb3, which belongs to the globosphingolipid group of glycolipids and consists of the Gal(α1-4)Gal(β1-4)Glc trisaccharide linked to ceramide [40]. The affinity of LecA for galactose or for its natural ligand Gal(α1-4)Gal is relatively low with dissociation constant (Kd) between 50 and 100 μM, but this limitation is compensated during infection by multivalent effects induced by the many oligosaccharide heads of glycolipids present on the membrane. An isomer of the natural ligand, the isogloboside trisaccharide Gal(α1-3)Gal(β1-4)Glc, displays comparable affinity and the crystal structure of the complex with LecA has been described (Figure 3A) [40], providing a basis for structure-guided design of mimetics. In the development of glycomimetics, β-galactosides with aromatic aglycones exhibit enhanced affinity, largely due to a T-shaped electronic interaction with His50 in the binding site [41]. For example, p-nitrophenyl-β-galactoside (PNP-Gal) binds with a Kd of 5 μM and the particular interaction is illustrated in Figure 3B. Other O- and S-linked aromatic derivatives have also been investigated [42], and the best monovalent ligand reported to date, a diarylthiogalactoside reaches an affinity of ∼1 μM [43]. This ligand adopts a binding mode closely resembling that of the natural ligand (Figure 3C), underscoring the potential of ligand design strategies that mimic the structural features of native glycans.

Crystal structures of LecA (surface in beige and ribbon in blue) complexed with natural and synthetic ligands. (A) Gal(α1-3)Gal(β1-4)Glc, PDB 2VXJ. (B) p-Nitrophenyl-β-galactoside, PDB 3ZYF. (C) Diarylthiogalactoside, PDB 7Z63. (D) Cyanocatechol, PDB 6YO3. (E) Phenylbutyryl hydroxamic acid, PDB 7FJH. (F) Difluoro tolcapone derivative, PDB 9I7Z. Schematic representation of ligands is displayed in the right upper corner of each panel (ChemSketch, ACD/Labs).

LecB exhibits strong affinity for natural ligands such as fucose (Kd ≈ 3 μM) and Fuc(α1-4)GlcNAc-containing trisaccharides, with a Kd of 210 nM for the Lewis a antigen (Figure 4A) [29]. Functionalization at the reducing end of this disaccharide yielded potent inhibitors with affinities comparable to those of the natural trisaccharide (Figure 4B) [44].

Crystal structures of LecB (surface in beige) complexed with natural and synthetic ligand. (A) Gal(β1-3)[Fuc(α1-4)]GlcNAc, PDB W8H. (B) Fuc(α1-4)GlcNAc triazole derivative, PDB 2JDK. (C) β-Fucopyranosyl-thiophenesulfonamide derivative, PDB 5MAZ. (D) β-Fucopyranosyl-biphenyl-3-carboxamide, PDB 8AIY. Schematic representation of ligands is displayed in the right upper corner of each panel (ChemSketch, ACD/Labs).

The observation that d-mannose, which is stereochemically related to l-fucose, is also a ligand for LecB has inspired the design of carbohydrate ring mimics, in which the axial anomeric oxygen of fucose is replaced by an equatorial sulfonamide moiety [45] (Figure 4C). Building on this approach, β-fucosyl amides, sulfonamides, and thiourea derivatives were synthesized, among which a β-fucosyl amide diaryl derivative displayed both high affinity and notable stability in plasma [46] (Figure 4D).

BambL from B. ambifaria also interacts with fucose-containing oligosaccharides, exhibiting high affinity for the fucose monosaccharide [34] as well as for fucosylated glycans such as Lewis and ABO antigens (Figure 5A). The synthesis of a conformationally constrained aryl-α-O-fucosyl analogue produced a compound with binding affinity comparable to that of native fucose, but with substantially enhanced selectivity, as it is not recognized by either human fucose-binding lectins or LecB [47]. The crystal structure of the BambL–ligand complex further revealed that the compound acts as an effective glycomimetic of natural fucosylated glycans, engaging the protein surface at the same binding site as the blood group B oligosaccharide [48] (Figure 5B).

Crystal structures of BambL (surface in beige) complexed with natural and synthetic ligands. (A) Gal(α1-3)[Fuc(α1-2)]Gal(β1-4)GlcNAc, PDB 3ZWE. (B) Conformationally constrained fucose-based glycomimetics, PDB 6ZFC. Schematic representation of ligands is displayed in the right upper corner of each panel (ChemSketch, ACD/Labs).

BC2L-C-nt from B. cenocepacia also binds fucose but displays a marked preference for H-type 1 (Figure 6A) and H-type 3 epitopes [49], albeit with modest affinity. An innovative fragment-based theoretical approach identified a binding pocket adjacent to the fucose-binding site, and several potential hits were subsequently validated using biophysical methods [50]. From the results of the fragment-based screening, bifunctional ligands were synthesized employing a panel of rationally selected linkers, yielding an alkene-bound glycomimetic with a tenfold increase in affinity relative to fucose (Figure 6B) [51]. Although N-fucosides were also synthesized, their poor aqueous solubility limited their application as antagonists. However, a subsequent generation of derivatives overcame this limitation, exhibiting both satisfactory affinity and improved solubility (Figure 6C) [52].

Crystal structures of BC2L-C-nt (surface in beige) complexed with natural and synthetic ligands. (A) Fuc(α1-2)Galβ(1-3)GlcNAc, PDB 6TID. (B) Ethynyl-phenyl derivative of fucose, PDB 7OLU. (C) Aminomethyl-phenyl derivative of fucose, PDB 8BRO. Schematic representation of ligands is displayed in the right upper corner of each panel (ChemSketch, ACD/Labs).

3.2. Covalent glyco-derived inhibitors

Covalent inhibitors have recently been developed to target growth factors in cancer and proteases in viral infections. Because specificity represents the primary challenge in this strategy, successful design requires precise positioning of the ligand warhead in close proximity to a reactive amino acid within the lectin binding site. In the case of LecA, this was achieved by exploiting Cys62, located at the base of the binding pocket near the secondary hydroxyl group of galactose (Figure 2A) [53]. A phenyl-β-galactoside derivative bearing an epoxy group at the C6 position was synthesized, and formation of the covalent adduct was confirmed by mass spectrometry. Furthermore, a fluorescein-conjugated derivative enabled specific staining of P. aeruginosa biofilms.

Another warhead was used for covalent inhibition of BC2L-C-nt by fucosides connected to salicylaldehyde groups by a variety of linkers with the aim of targeting Lys108 in the binding site of the lectin [54]. Mass spectrometry conducted on the whole lectin and on digestion peptides confirmed the formation of the covalent adduct.

3.3. Non-carbohydrate glycomimetics

All of the inhibitors described above retain the principle of a glycan residue bound in the primary binding site of the lectin. In contrast, non-carbohydrate glycomimetics offer the potential for more straightforward synthetic routes, broader chemical diversity, and improved pharmacokinetic properties. Using a virtual screening strategy, more than 1500 compounds from the National Cancer Institute (NCI) Diversity set IV were docked into LecA, leading to the identification of promising candidates [55]. Many of these compounds contained a catechol moiety, raising the possibility of false positives due to nonspecific reactivity with the protein surface. Nevertheless, screening of catechol libraries with multiple biophysical methods confirmed that several electron-deficient catechols bind specifically to LecA. Although their affinities were only in the millimolar range, the crystal structure of LecA in complex with cyanocatechol demonstrated that its oxygen atoms mimic the roles of galactose O3 and O4 in coordinating calcium within the binding site (Figure 3D) [55]. Building on this concept of metal-binding pharmacophores as novel scaffolds for inhibiting Ca2+-dependent lectins, both virtual and NMR-based screening of general and specialized compound libraries were undertaken [56]. Several hydroxamates were identified as specific LecA ligands, again with affinities in the low millimolar range, and crystal structures confirmed their calcium-coordinating interactions (Figure 3E) [56]. By contrast, malonates displayed broader activity, binding not only to LecA and LecB but also to human C-type lectins. To further develop the catechol-based scaffold, 3267 unique catechol derivatives from the Hoffmann-La Roche compound library were tested for LecA binding [57]. Among these, tolcapone, a drug used in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease, and several structural analogues, emerged as potent ligands with affinities around 10 μM—approximately 5- to 10-fold stronger than galactose. The crystal structure of one representative compound (Figure 3F) revealed that these ligands not only coordinate calcium but also form hydrogen bonds with conserved water molecules and engage in hydrophobic interactions with the protein surface.

3.4. Structure-based multivalent ligands

Structural information on lectins can also be used for the design of multivalent ligands with appropriate linkers to reach two or more binding sites of the lectins, resulting in a chelating effect that can result in several-fold increases in affinity [7].

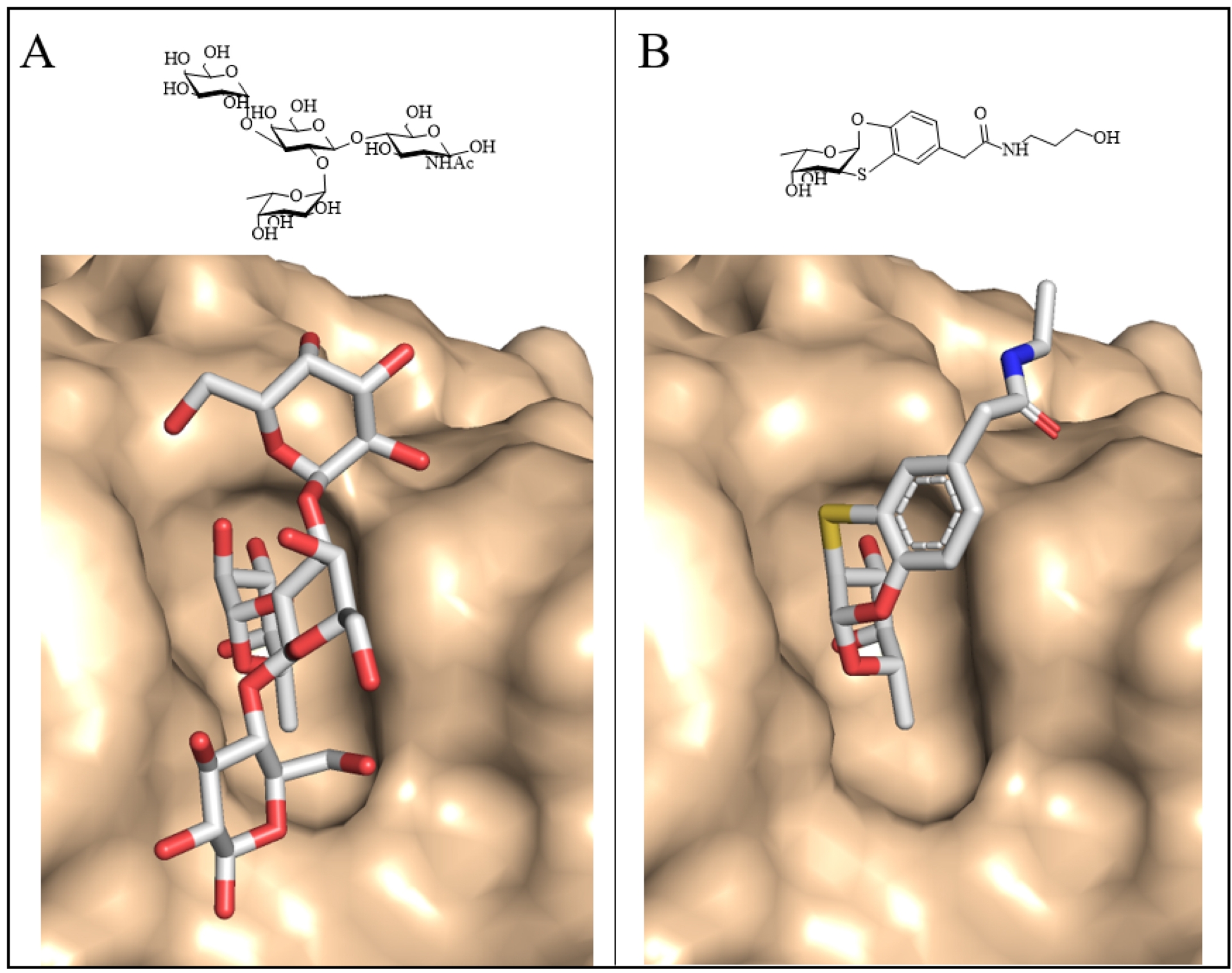

A substantial body of literature has described the synthesis of glycoclusters, glycopolymers, and other multivalent ligands targeting LecA and LecB (see Refs. [58, 59, 60]). In the case of P. aeruginosa, the present article focuses on selected examples of structure-based design of divalent ligands for LecA. The architecture of the LecA tetramer (Figure 1A), which presents two galactose-binding sites separated by approximately 29 Å on the same face, provides an optimal framework for the rational design of divalent ligands. Flexible linkers, such as those based on polyethylene glycol (PEG), proved ineffective in promoting efficient chelation due to the entropic penalty arising from their conformational flexibility. In contrast, introducing additional interactions at the protein surface, for instance, through linkers identified from a large heteroglycoconjugate library generated by nucleic-acid-encoded peptide synthesis, yielded high-affinity binders with dissociation constants as low as 82 nM [61]. Rigid spacers proved even more effective at eliciting strong avidity effects, provided they positioned the two galactose moieties at the appropriate distance while retaining adequate aqueous solubility. Subsequent optimization, involving the incorporation of alternating glucose and triazole units, resulted in a ligand with an affinity of 28 nM, corresponding to an approximately 100-fold improvement relative to the monovalent ligand [62]. Remarkably, this compound was the only divalent ligand successfully crystallized with LecA (Figure 7A), as the high protein concentrations required for crystallization typically favor ligand cross-bridging rather than intramolecular chelation. Additional potent divalent galactosides, with dissociation constants in the range of 10–40 nM, were later reported by Titz and colleagues, who also demonstrated their improved solubility and effectiveness in reducing P. aeruginosa invasiveness in host cells (Figure 7B) [39].

Some multivalent glycosides with high affinity for bacterial lectins. (A) Divalent galactoside with triazolyl–glucose-based linker in complex with LecA (surface in beige, crystal structure PDB 4YWA). (B) Divalent galactoside with aromatic-based linker also binding to LecA. (C) Pentavalent fucoside with high affinity for BambL (model superimposed on crystal structure, PDB 6ZFC).

The spherical architecture of LecB, with its fucose-binding sites positioned far apart, is not favorable for the design of divalent chelating ligands. Consequently, only limited improvements in binding affinity have been achieved relative to fucose itself [60]. In contrast, the propeller-shaped architecture of BambL is more amenable to multivalent ligand design, as it allows simultaneous engagement of two or more of the six fucose-binding sites, each separated by approximately 20 Å. The glycomimetic structure depicted in Figure 5B was assembled into a hexavalent ligand using a peptide raft scaffold [63]. The resulting construct exhibited the appropriate shape and size to interact with multiple sites of the BambL propeller, as demonstrated by the structural superposition shown in Figure 7C, and achieved a Kd of 14 nM. An alternative strategy exploited ligand cooperativity through PNA–fucose conjugates, which contained only a single fucose residue but were capable of hybridizing via the PNA (peptide nucleic acid) backbone in the presence of the protein [64]. This cooperative assembly resulted in high-affinity binding, with a Kd of 11 nM.

4. Prospectives: identification of new targets

This article highlights a subset of bacterial species implicated in lung infections, yet the principles discussed are broadly applicable to other carbohydrate-dependent pathogens. Indeed, comparable strategies have already proven effective against uropathogenic Escherichia coli, which use FimH adhesin to bind to mannosylated epitopes on urothelial cells, a crucial step in urinary tract infections [65]. Looking forward, the identification of novel lectin targets is likely to expand considerably, as systematic data mining of genomic resources now enables the prediction of putative lectins across bacterial, viral, and fungal species [66]. Dedicated tools such as LectomeXPlore will accelerate this process, providing a framework for the rational prioritization of targets [67]. In parallel, the rapid advances of carbohydrate-based therapeutics in oncology and vaccinology underscore their untapped potential in infectious disease management. Positioned as a complementary strategy to antibiotics, these approaches could play a decisive role in addressing the dual challenges of antimicrobial resistance and the emergence of novel pathogens driven by climate change.

Acknowledgments

Pathogens in the graphical abstract are designed by Freepik (www.freepik.com).

Declaration of interests

The author does not work for, advise, own shares in, or receive funds from any organization that could benefit from this article, and has declared no affiliations other than their research organization.

Funding

Support from CNRS, CBH-EUR-GS (ANR-17-EURE-0003) and Glyco@Alps (ANR-15-IDEX-02) is acknowledged.

CC-BY 4.0

CC-BY 4.0