1. Introduction

Targeting RNA using synthetic small molecules has become an important field of medicinal chemistry [1]. Indeed, the targeting of biologically relevant RNAs is an interesting approach for the discovery of innovative therapies because of the essential role that RNA plays in all major biological processes [2]. Noteworthy, RNA bears a tridimensional structure associating single-stranded and double-stranded regions and leading to the formation of stem-loop structures containing internal loops and bulges that create ideal binding sites for small-molecule ligands due to the distortion of the RNA double helix [3]. A number of RNA binders has been reported in the literature during the last twenty years against viral, bacterial and oncogenic RNAs [4]. Furthermore, drugs acting as RNA binders are already on the market, such as the antibiotic aminoglycosides or mRNA splicing modulators, such as risdiplam [5]. However, methods to rationally design ligands specific to a particular RNA structure remain underdeveloped because of a lack of knowledge about the tridimensional structure of most RNA targets as well as about the interactions formed by the reported ligands [1].

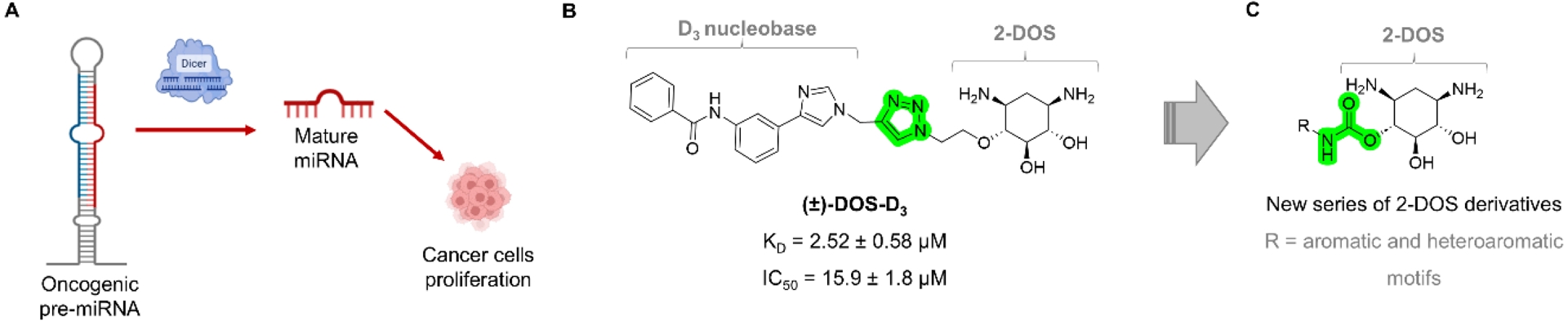

During the last years, our group has focused on the targeting of non-coding RNAs, such as microRNAs (miRNAs or miRs). These small non-coding RNAs are responsible for the regulation of gene expression [6]. They are produced in the cell starting from two precursors: primary miRNAs (pri-miRNAs) followed by precursor miRNAs (pre-miRNAs) upon processing by intracellular ribonucleases called Drosha and Dicer, respectively (Figure 1A). These precursors are stem-loop–structured RNAs and have been reported as targets for small molecules. In this context, we reported various series of compounds whose synthesis was performed using a focused design [7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14] based on the conjugation of various RNA-binding domains that act cooperatively to bind the RNA target with both affinity and selectivity. More specifically, several binding domains such as aminoglycosides, heteroaromatic compounds, and amino acids [10, 11, 13, 14] were combined to synthesize ligands directed against the production of miR-372, an oncogenic miRNA involved in various cancers [15, 16], such as gastric cancer. This work allowed us to develop optimized compounds with a specific antiproliferative activity in gastric adenocarcinoma cells overexpressing miR-372. The mechanism of this inhibition was clearly identified as resulting from the binding to pre-miR-372 and the inhibition of Dicer processing leading to mature miRNA. Among these ligands, there were a series of conjugates containing the 2-deoxystreptamine (2-DOS) core linked to various heteroaromatic compounds via a triazole linker [17]. This led us to the discovery of compound DOS-D3 (Figure 1B), which showed a low micromolar affinity for pre-miR-372 as well as a low micromolar IC50 for the inhibition of Dicer processing. This compound is composed of a 2-DOS structure, present in most of the aminoglycoside antibiotics that act by binding to prokaryotic ribosomal RNA thus impairing protein synthesis in bacteria, coupled via a triazole linker to an artificial nucleobase called D3. While 2-DOS is known to strongly interact with RNA but lacks selectivity, the heteroaromatic moiety D3 is known to selectively interact with A∙U base pairs via the formation of specific hydrogen bonds to form a base triplet [18]. Thus, derivatives combining 2-DOS and more selective substructures (such as D3 for example) have the advantage of bearing more favorable physicochemical properties than their aminoglycoside counterpart while maintaining a similar affinity for RNA. In this work, we decided to explore the carbamate linker as a replacement for the triazole one to modify the properties of the compounds (Figure 1C). Indeed, while both triazole and carbamate are commonly employed in medicinal chemistry, the carbamate linker is more flexible and could improve affinity and binding properties [19]. Carbamates can serve as both hydrogen-bond donors and acceptors and, since they are geometrically and electronically closer to amides than triazoles, they can better mimic peptide-like motifs, peptides being the RNA binders chosen by Nature.

(A) General process of pre-miRNA cleavage by Dicer to produce the mature miRNA. When the miRNA is oncogenic, its production induces the proliferation of cancer cells, and the pre-miRNA represents a potential target for small molecules to block cancer cell proliferation. (B) Chemical structure of a previously identified pre-miR-372 binder based on 2-DOS conjugated via a triazole linker to a heteroaromatic motif to form DOS-D3. (C) General chemical structure of the 2-DOS conjugates prepared in this study.

We thus prepared a series of nine derivatives where 2-DOS was conjugated with a carbamate linker to aromatic and heteroaromatic compounds. These new derivatives have been studied against our primary target, pre-miR-372, but also against other miRNAs that could represent potential targets or competitors. The study of the affinity, selectivity and inhibition activity for the processing of these miRNAs revealed a promising selectivity profile for some compounds that could be exploited for future intracellular studies.

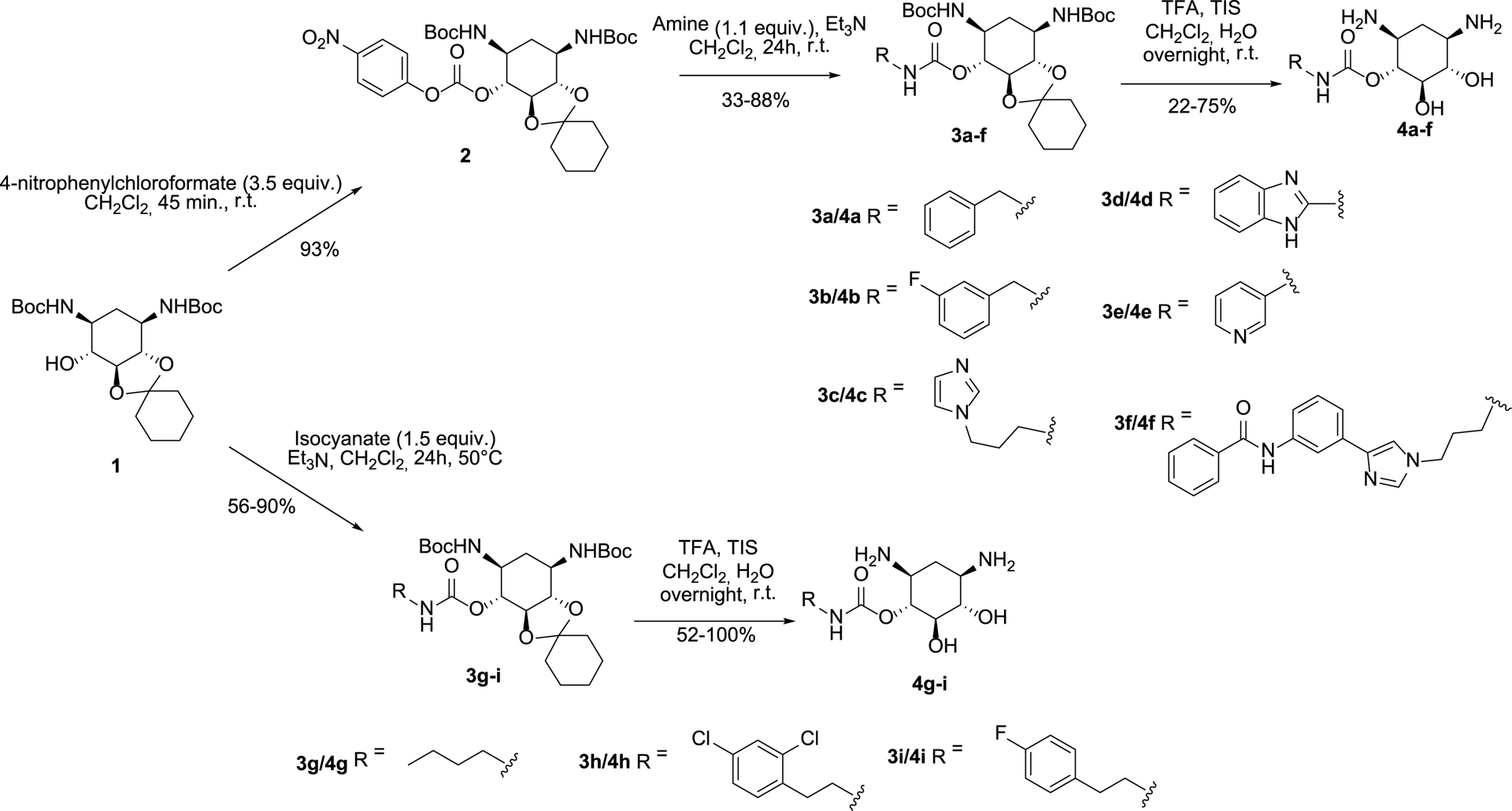

Synthesis of new carbamate derivatives of 2-DOS 4a–i.

2. Results and discussion

2.1. Synthesis of 2-deoxystreptamine derivatives

2-DOS represents an ideal platform for the development of RNA binders since it bears two cis-amino groups recognized as very important for RNA binding and hydroxyl groups that can be functionalized [20, 21]. We thus decided to substitute one of the hydroxyl groups with various aromatic and heteroaromatic substituents via the formation of a carbamate linker. Carbamates show many advantages, such as the ability to permeate the cell membrane as well as a particular chemical stability. For these reasons, carbamates have been used in the design of various drugs, such as β- and γ-secretase inhibitors, carbamate-based Hepatitis C virus (HCV) therapeutics or cysteine-protease inhibitors [19]. To prepare new conjugates with 2-DOS, we chose to conjugate various aromatic and heteroaromatic compounds (R in Figure 1B). First, we chose phenyl substituents containing or not fluorine atom(s) because this kind of substituent could interact with RNA by forming hydrophobic interactions or through unusual hydrogen bonds mediated by the fluorine atoms. Then, we chose heteroaromatic compounds such as imidazole, benzimidazole, pyridine, and the previously employed D3 nucleobase [N-(3-(1-(3-aminopropyl)-1H-imidazol-4-yl)phenyl)benzamide]. To obtain a novel series of ligands with high RNA binding affinity and miRNA inhibitory activity, we thus employed commercially available substrates as well as starting materials prepared using straightforward synthetic pathways. To synthesize the carbamate compounds, we decided to start from the previously prepared protected racemic compound 1 [17] and to use two approaches (Scheme 1): (i) preparation of the activated carbonate 2 followed by amine substitution leading to compounds 3a–f, and (ii) reaction of the free alcohol of 1 with various isocyanates leading to compounds 3g–i.

Following the first strategy, compound 1 was converted into its corresponding activated carbonate 2 in the presence of 4-nitrophenyl chloroformate in CH2Cl2. Compound 2, obtained in 93% yield, was then coupled with suitable (hetero)aromatic compounds bearing amine groups in order to form the desired carbamate derivatives. We selected five commercially available amines for the synthesis of compounds 3a–e and an artificial nucleobase that we had previously prepared for the synthesis of neomycin and 2-DOS derivatives, e.g., the N-(3-(1-(3-aminopropyl)-1H-imidazol-4-yl)phenyl)benzamide [22] also called D3 for the preparation of compound 3f and to achieve structural diversity of synthesized ligands (Figure S1, Supporting Information for the chemical structures of amine derivatives). The reaction of the amines with carbonate 2 was carried out in the presence of Et3N in CH2Cl2 at 50 °C leading to the protected carbamate derivatives 3a–f in 33–88% yields. Removal of the Boc and acetal protecting groups of compounds 3a–f was performed in one step under acidic conditions (TFA in a mixture of CH2Cl2/water 2:1) and in the presence of tripropylsilane (5%) as a scavenger. The final compounds 4a–f were obtained in 22–67% yields.

Concomitantly to the preparation of carbamate derivatives 4a–f, we also decided to prepare new conjugates upon reaction of commercially available isocyanates with compound 1. As illustrated in Scheme 1, treatment of three isocyanates, whose chemical structures are illustrated in Figure S2, with protected 2-DOS 1 in the presence of Et3N at 50 °C, led to the desired carbamates 3g–i in 56–90% yields. The final deprotection of these conjugates using TFA and TIS (5%) in a mixture of CH2Cl2/H2O (2:1) allowed the obtention of the final compounds 4g–i, which were isolated in 52–100% yield after purifications using semi-preparative HPLC. All conjugates were fully characterized by NMR, HRMS, and HPLC.

2.2. Evaluation of the affinity and inhibition activity of the synthesized 2-DOS conjugates

Once the compounds synthesized and characterized, we evaluated their affinity for pre-miR-372 but also for other microRNAs to assess the extent of selectivity that could be reached by these compounds. For this, pre-miR-17 as well as pre-miR18a, pre-miR-148a, and pre-miR-210 were chosen. The corresponding miRNAs are overexpressed in different types of cancers thus representing interesting RNAs to assess selectivity but also as potential targets. The evaluation of the affinity was performed using established assays where the target RNA is 5′-labeled with a fluorophore (fluoresceine) and incubated with increasing concentrations of the synthesized compounds. If a compound binds to the RNA target, the environment of the fluorophore changes and induces a dose-dependent variation in fluorescence. This allows the measurement of dissociation constants (KD) for all compounds against the five chosen pre-miRNAs. The results reported in Table 1 demonstrated that among all tested compounds, only three displayed an affinity for the pre-miRNAs studied: compounds 4c, 4f, and 4h. Compounds 4c and 4h showed affinity only for one pre-miRNA each, i.e., pre-miR-210 for 4c (KD = 42.3 μM) and pre-miR-372 for 4h (KD of 38.4 μM). These results, although moderate, suggest that these compounds could be further studied to optimize them in order to obtain selective compounds for one targeted RNA structure. Compound 4f strongly binds to both pre-miR-372 (KD of 2.36 μM) and pre-miR-17 (KD = 1.88 μM), while the affinity decreases at least ten times when tested on other pre-miRNAs. To further confirm the selectivity of compound 4f, we tested it in competition with other nucleic acids, i.e., a large excess (100 equiv) of tRNA and DNA, and the obtained results showed that 4f maintains its affinity for pre-miR-372 in both cases (data not shown).

Dissociation constants (KD, μM) for synthesized compounds 4a–i and for reference DOS-D3 against pre-miR-372, -17, -18a, -148a, and -210

| ID | KD (pre-miR-372) | KD (pre-miR-17) | KD (pre-miR-18a) | KD (pre-miR-148a) | KD (pre-miR-210) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4a | No binding | >50 | No binding | No binding | No binding |

| 4b | >50 | >50 | No binding | No binding | No binding |

| 4c | No binding | >50 | No binding | No binding | 42.3 ± 7.5 |

| 4d | No binding | >50 | No binding | No binding | No binding |

| 4e | No binding | No binding | No binding | No binding | No binding |

| 4f | 2.36 ± 0.32 | 1.88 ± 0.22 | 20.2 ± 1.85 | 33.5 ± 0.35 | 35.7 ± 0.42 |

| 4g | No binding | No binding | No binding | No binding | No binding |

| 4h | 38.4 ± 11 | No binding | No binding | No binding | No binding |

| 4i | >50 | >50 | No binding | No binding | No binding |

| DOS-D3 | 2.52 ± 0.58 | 0.880 ± 0.075 |

Binding studies were performed on 5′-FAM-pre-miR-372 in 20 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.4), 12 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM MgCl2, and 1 mM DTT.

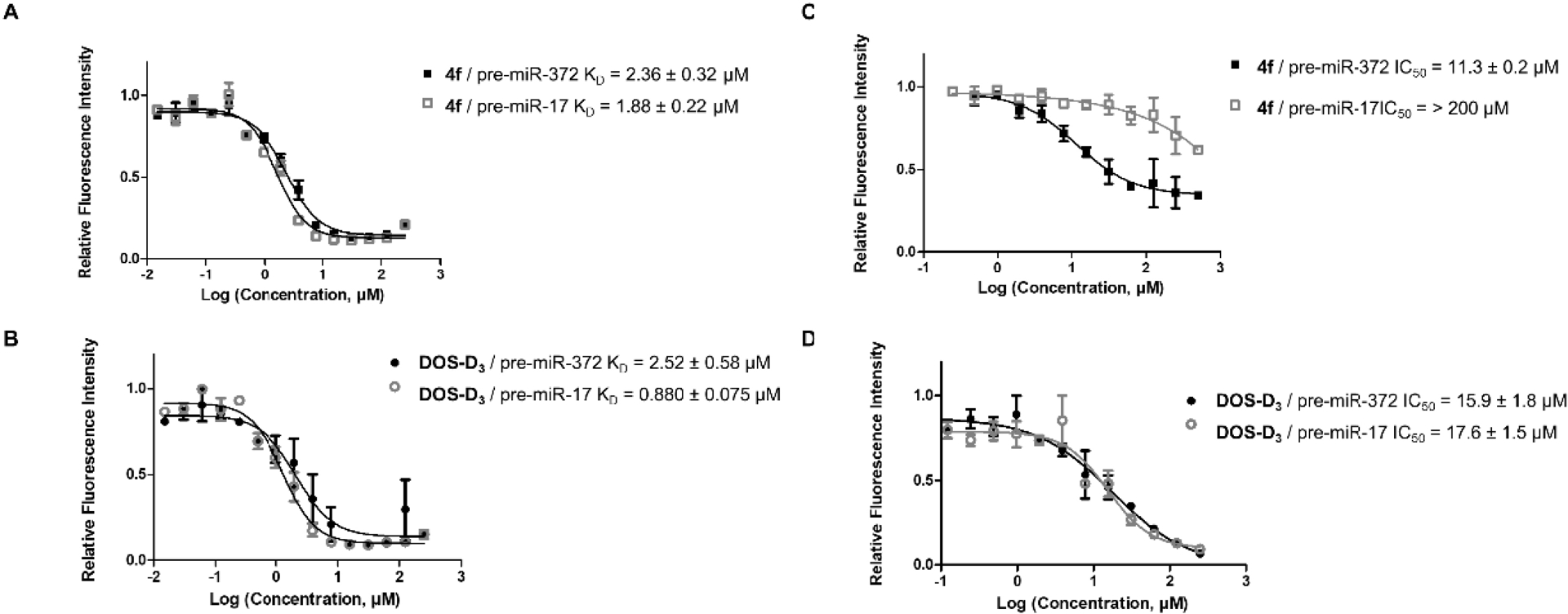

Interestingly, compound 4f exhibits the same affinity as the previous hit of the triazole series DOS-D3 (Figure 1A) suggesting that the linker does not affect the affinity. We thus wondered if the modification of the linker from triazole to carbamate was affecting the inhibition activity. To assess this parameter, we employed a FRET-based assay that we had previously validated to measure the ability of a compound to block Dicer processing by binding to a pre-miRNA.

Compounds 4f (Figure 2A) and DOS-D3 (Figure 2B) exhibit similar affinity for both pre-miR-372 and pre-miR-17. In contrast, compound 4f shows a 11.3 μM IC50 for the inhibition of pre-miR-372 processing but cannot inhibit Dicer processing of pre-miR-17 (Figure 2C). Derivative DOS-D3 can inhibit the processing of pre-miR-372 and pre-miR-17 with similar IC50s of 15.9 and 17.6 μM, respectively (Figure 2D). So, while DOS-D3 does not show selectivity between pre-miR-372 and pre-miR-17 in binding and inhibition activities, compound 4f, while binding both, inhibits only the processing of pre-miR-372. This could be due to differences in the binding site that could be much more favorable for inhibition in the case of pre-miR-372 than in pre-miR-17 and this result further supports the selectivity of compound 4f for the targeted miRNA.

(A) Dissociation constants curves for compound 4f against pre-miR-372 (full black squares) and pre-miR-17 (empty grey squares) with the associated KD values. (B) Dissociation constants curves for compound DOS-D3 against pre-miR-372 (full black circles) and pre-miR-17 (empty grey circles) with the associated KD values. (C) Inhibition curves for the processing of pre-miR-372 (full black squares) and pre-miR-17 (empty grey squares) by Dicer in the presence of compound 4f and the associated IC50 values. (D) Inhibition curves for the processing of pre-miR-372 (full black circles) and pre-miR-17 (empty grey circles) by Dicer in the presence of compound DOS-D3 and the associated IC50 values.

2.3. Study of the binding site of compound 4f

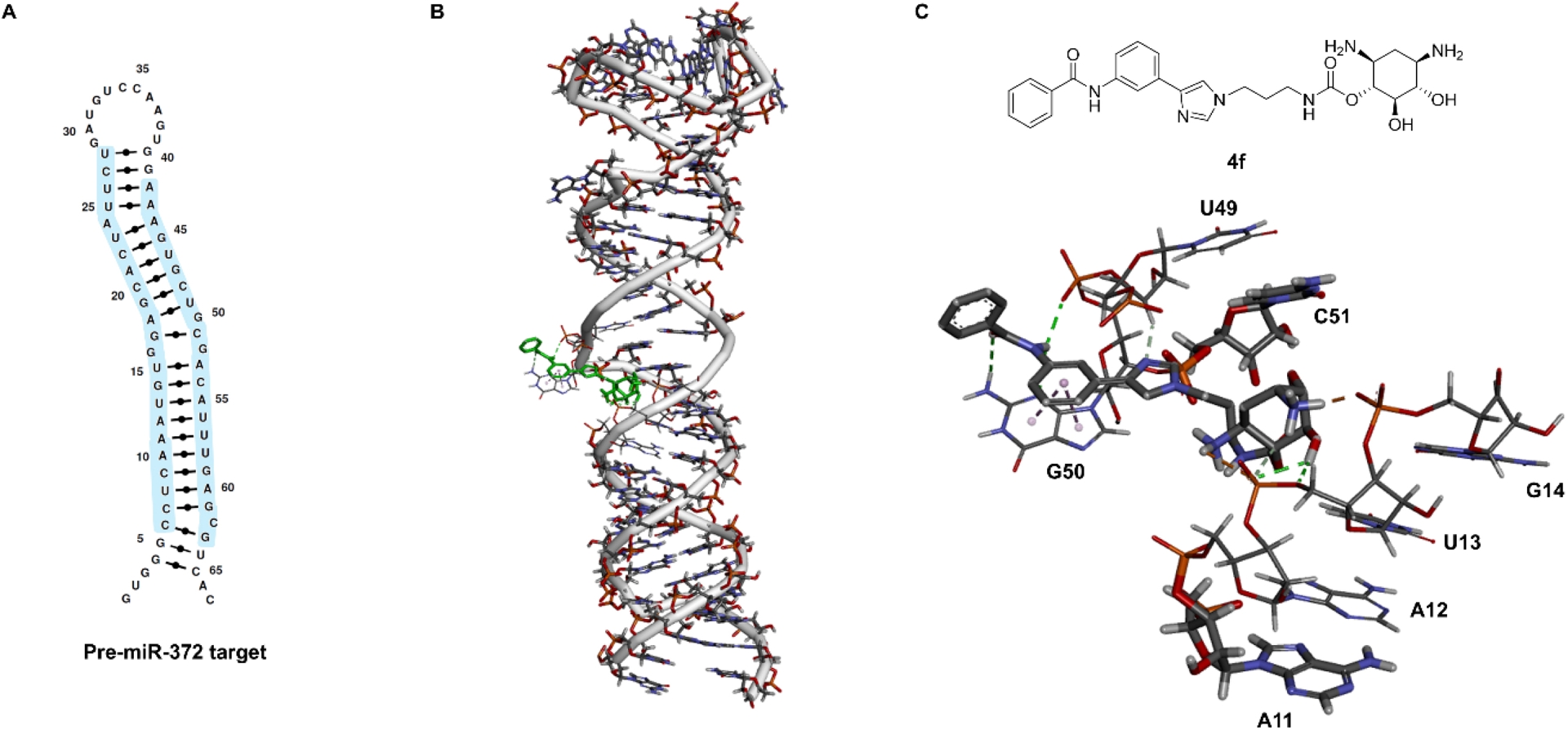

To gain a better understanding of differences in the inhibition activity between pre-miR-372 and -17 for compound 4f, we employed molecular docking and explored what could be the site of interaction of 4f on the two RNA structures. MC-Fold/MC-Sym, a program allowing RNA-structure prediction, was previously employed to predict the structural organization and the double-helix region of multiple pre-miRNAs [23]. Here, we employed the pre-miR-372 and pre-miR-17 structures obtained by integrating the MC-Fold/MC-Sym and AutoDock programs [24]. The exploration of the binding site of compound 4f on pre-miR-372 showed that this compound likely interacts with residues A11–G14 and U49–C51 where a G-bulge as well as an internal G-loop open the duplex region offering a favorable binding site (Figure 3). Compared to our previous study about the DOS-D3 compound, the binding site has changed. This highlights how minor changes in the chemical structure of an RNA ligand unexpectedly modify its binding site, rendering unpredictable which modifications should be performed to improve binding.

(A) Primary and secondary structures of pre-miR-372 RNA target. (B) Docking of compound 4f with the pre-miR-372 hairpin loop performed using Autodock 4 in which the grid boxes were fixed on the entire RNA sequence. (C) Chemical structure of compound 4f and detail of the binding pocket and interactions formed.

The results described above, however, support a selective binding to pre-miR-372. While the binding site of 4f on pre-miR-372 was confirmed in all binding poses obtained after docking, we found many possible binding sites in the case of pre-miR-17 binding. The one that occurs most frequently is located in the internal loop CA/GUA located in the lower-stem part of the pre-miRNA (Figure S4). These results suggest that binding to pre-miR-372 is much more efficient than to pre-miR-17 in inhibiting Dicer processing, due to differences in the binding site and interactions.

3. Conclusion

In this work, we successfully synthesized a new series of 2-DOS conjugates using a divergent synthetic method that led to nine new compounds. Some of these compounds can bind to the desired target pre-miR-372, the precursor of oncogenic miR-372, with low micromolar affinities making them interesting compounds, especially compound 4f, able to inhibit Dicer processing of this pre-miRNA. Interestingly, compound 4f is also selective since the comparison of its affinity with pre-miR-17, -18a, -148a, and -210 showed that 4f binds to pre-miR372 and pre-miR-17 with similar activities but not to the other pre-miRNAs. Furthermore, compound 4f showed a specific inhibition of pre-miR-372 processing while the other pre-miRNAs were not affected. Molecular docking showed that the binding site of 4f on the pre-miR-372 structure is much more favorable for inhibition than the one on pre-miR-17 thus explaining the specificity observed in inhibition activity. It is important to note that compound 4f derives from the conjugation of 2-DOS with an artificial nucleobase via a carbamate linker and that we previously studied the same conjugate but containing a triazole linker: compound DOS-D3. Both compounds show similar activity on pre-miR-372 but only 4f shows a specific inhibition activity. Furthermore, the modification from a triazole to a carbamate linker induced a major change in the binding site on the pre-miR-372 structure. This further supports an observation that we made for many series of RNA ligands before: what could be considered minor changes in the chemical structure of an RNA binder induces major modifications in the binding site and eventual biological activity. This represents one of the major limitations when designing RNA binders since it hampers our ability to predict the chemical modifications that should be introduced to improve binding based on the structure of the target. The study presented here contributes to a better understanding of the binding and inhibition activity of this kind of 2-DOS derivatives and more generally to the rules that govern RNA binding to small molecules.

4. Experimental section

4.1. Chemistry

Reagents and solvents were purchased from Merck or Carlo Erba and used without further purification. All reactions that involved air- or moisture-sensitive reagents or intermediates were performed under an argon atmosphere. Flash column chromatography was carried out on silica gel (Merck; SDS 60 Å, 40–63 μM, VWR). Analytical TLC was conducted on pre-coated silica gel plates (60F254; Merck) and compounds were visualized by irradiation (𝜆 = 254 nm) or by staining with ninhydrin. 1H and 13C NMR spectra were recorded on Bruker AC 200 and 500 MHz spectrometers. Chemical shifts are reported in parts per million (ppm, 𝛿) referenced to the residual 1H resonance of the solvent (CDCl3 𝛿 7.26; CD3OD 𝛿 3.31; DMSO-d6 𝛿 2.50; acetone-d6 𝛿 2.05 ppm). Splitting patterns are labeled as follows: s (singlet), d (doublet), t (triplet), m (multiplet), and br s (broad singlet). Coupling constants (J) are listed in hertz (Hz). High resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) was carried out on an LTQ Orbitrap hybrid mass spectrometer with an electrospray ionization probe (Thermo Fisher Scientific, San Jose, CA) by direct infusion from a pump syringe, to confirm the correct molar mass and high purity of the compounds. HPLC analyses were performed using a Waters Arc HPLC pump coupled to a Waters 2998 photodiode array detector and Waters Cortex® C18+ column (50 × 4.6 mm, 2.7 μm). Analyses were run at room temperature by using a gradient of CH3CN containing 0.1% formic acid (eluent B) in water containing 0.1% formic acid (eluent A) at a flow rate of 1.5 mL/min. The gradient of elution employed was 5 to 40% eluent B over 5 min and 40 to 100% eluent B over 2 min.

1,3-Bis-N-(tert-butyloxycarbonyl)-5,6-O-cyclohexylidene-2-deoxystreptamine (1) was prepared following a previously published procedure [17].

4.2. General protocol of carbamate synthesis starting from the activated carbonate of 2 (General procedure A)

To a stirred solution of compound 2 (100 mg, 0.16 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (5 mL), were added triethylamine (25 μL, 0.18 mmol, 1.1 equiv) and the appropriate amine (commercially available benzylamine, 3-fluorobenzylamine, 1-(3-aminopropyl)imidazole, 2-aminobenzimidazole, 3-aminopyridine and the prepared N-(3-(1-(3-aminopropyl-1H-imidazol-4-yl)phenyl)benzamide (see below) (0.18 mmol, 1.1 equiv) at room temperature. After stirring for 24 h at rt or at 50 °C, the reaction mixture was evaporated under reduced pressure, and the crude residue was purified by flash chromatography on a silica gel column.

4.3. General protocol of carbamate synthesis starting from protected 1 (General procedure B)

To a solution of compound 1 (100 mg, 0.23 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (5 mL), were added triethylamine (47.4 μL, 0.34 mmol, 1.5 equiv) and the appropriate isocyanate (butyl isocyanate, 2,4-dichloro-1-(2-isocyanatoethyl)benzene and 1-fluoro-4-(2-isocyanatoethyl)benzene, 0.34 mmol, 1.5 equiv). After stirring for 24 h at 50 °C, the reaction was concentrated in vacuo, and the residue was purified by silica gel column chromatography.

4.4. General procedure for cleavage of the Boc and acetal groups (General procedure C)

To a solution of protected compounds 3a–i in CH2Cl2 and H2O (3:1), was added TFA (50 equiv). The reaction mixture was stirred at rt overnight. Solvent and residues of TFA were then removed under reduced pressure by co-evaporating twice with toluene. Ether precipitation led to pure compounds as white solids (TFA salts).

4.5. N-3-(1-(3-aminopropyl-1H-imidazol-4-yl)phenyl)benzamide (D3)

To a solution of the previously described N-(3-(1H-imidazol-4-yl)phenyl)benzamide (250 mg, 0.95 mmol) in dry THF (10 mL), were added sodium hydride (45.6 mg, 1.9 mmol, 2 equiv) and 3-(Boc-amino)propyl bromide (317 mg, 1.42 mmol, 1.4 equiv), and the reaction mixture was stirred overnight at 60 °C. After evaporation of the solvent, the crude residue was dissolved in EtOAc and washed three times with H2O. The organic phase was dried over reduced pressure. The residue was then purified by flash chromatography on a silica gel column using a mixture of CH2Cl2/MeOH 98:2 leading to the desired protected compound as a light yellow solid. This compound was then deprotected using TFA (61 μL, 0.79 mmol, 10 equiv) in CH2Cl2 (0.6 mL) at rt for 3 h. After evaporation of the solvent and removal of the residual TFA by co-evaporation with toluene, the crude product was purified by flash chromatography on a silica gel column using a mixture of CH2Cl2/MeOH 9:1 leading to the desired protected compound as a light yellow solid in 73% yield (300 mg) over two steps. RF = 0.20 (CH2Cl2/MeOH 8:2); 1H NMR (200 MHz, CD3OD) 𝛿 (ppm): 8.10–7.90 (m, 3H), 7.80–7.70 (m, 2H), 7.65–7.50 (m, 5H), 7.40–7.30 (m, 1H), 4.20–4.10 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 2H), 2.70–2.60 (m, 2H), 2.10–1.95 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (50 MHz, CD3OD) 𝛿 (ppm): 161.5, 157.9, 148.3, 144.9, 140.2, 138.9, 136.1, 132.8, 129.6, 128.6, 121.9, 120.7, 118.3, 117.1, 45.6, 38.1, 34.7; MS (ESI) m/z = 321.2 [M+H]+ (theoretical m/z 321.0).

4.6. 1,3-Bis-N-(tert-butyloxycarbonyl)-5,6-O-cyclohexylidene-2-deoxystreptamine-4-O-[p-nitrophenyl] carbonate (2)

To a solution of commercially available p-nitrophenyl chloroformate (980 mg, 4.86 mmol, 3.5 equiv) in CH2Cl2 (5 mL), were added pyridine (461 μL, 5.72 mmol, 4 equiv) and compound 1 (633 mg, 1.43 mmol). The reaction mixture was stirred for 45 min at rt and then washed twice with H2O (2 × 20 mL). The organic phase was dried over MgSO4. Concentration under reduced pressure followed by flash chromatography on a silica gel column using a mixture cyclohexane/EtOAc 6:4 led to desired compound 2 as a white solid in 93% yield (807 mg). RF = 0.52 (cyclohexane /EtOAc 6:4); 1H NMR (200 MHz, CD3OD) 𝛿 (ppm): 8.33 (d, J = 10.2 Hz, 2H), 7.47 (d, J = 10.2 Hz, 2H), 5.02–4.92 (m, 1H), 3.84–3.50 (m, 4H), 2.18–2.09 (m, 1H), 1.60–1.50 (m, 10H), 1.45 (br s, 18H), 1,31–1.29 (m, 1H); 13C NMR (50 MHz, CD3OD) 𝛿 (ppm): 157.7, 157.0, 153.5, 146.9, 126.27, 123.1, 113.8, 80.5, 79.7, 79.0, 51.7, 37.4, 37.2, 28.7, 26.1, 24.7; MS (ESI) m/z = 630.4 [M+Na]+ (theoretical m/z 630.3).

4.7. 1,3-Bis-N-(tert-butyloxycarbonyl)-5,6-O-cyclohexylidene-2-deoxystreptamine-4-N-benzylcarbamate (3a)

General procedure A was employed for the reaction between compound 2 (100 mg) and commercially available benzylamine (20 μL). Compound 3a was obtained after purification by flash chromatography on a silica gel column using a mixture cyclohexane/EtOAc 6:4 as a white solid in 88% yield (81 mg). RF = 0.25 (cyclohexane/EtOAc 8:2); 1H NMR (200 MHz, CDCl3) 𝛿 (ppm): 7.34–7.24 (m, 5H), 4.30 (br s, 2H), 3.68–3.33 (m, 5H), 2.57–2.51 (m, 1H), 1.60–1.50 (m, 8H), 1.42–1.10 (m, 21H); 13C NMR (50 MHz, CDCl3) 𝛿 (ppm): 156.2, 155.3, 138.1, 128.8, 127.7, 127.6, 112.9, 80.0, 79.0, 74.6, 51.8, 36.4, 31.1, 29.8, 28.5, 25.1, 23.8; MS (ESI) m/z = 576.5 [M+H]+ (theoretical m/z 576.3).

4.8. 1,3-Bis-N-(tert-butyloxycarbonyl)-5,6-O-cyclohexylidene-2-deoxystreptamine-4-O-[N-m-fluorobenzyl]-N-methyl carbamate (3b)

General procedure A was employed for the reaction between compound 2 (100 mg) and 3-fluorobenzylamine (24.7 μL). Purification by flash chromatography on a silica gel column using a mixture cyclohexane/EtOAc 7:3 afforded the desired product 3b in 83% yield (80.7 mg). RF = 0.54 (cyclohexane/EtOAc 6:4); 1H NMR (200 MHz, CD3OD) 𝛿 (ppm): two isomers (minor one in italic): 7.38–7.28 (m, 1H), 7.08–6.96 (m, 3H), 4.96–4.85 (m, 2H), 4.58–4.38 (d, J = 15.8 Hz , 2H), 4.20–4.12 (d, J = 16.0 Hz, 1H), 3.76–3.46 (m, 4H), 2.89 (s, 3H), 2.85 (s, 3H), 2.18–2.10 (m, 1H), 1.65–1.25 (m, 29H); 13C NMR (50 MHz, CD3OD) 𝛿 (ppm): 166.9, 162.0, 158.1, 157.7, 157.3, 141.7, 131.4, 124.6, 115.4, 114.9, 113.4, 80.2, 79.8, 79.6, 76.8, 53.0, 52.7, 52.2, 52.1, 37.3, 37.1, 34.6, 34.3, 30.7, 28.7, 26.1, 24.7; MS (ESI) m/z 608.5 [M+H]+ (theoretical m/z 608.3).

4.9. 1,3-Bis-N-(tert-butyloxycarbonyl)-5,6-O-cyclohexylidene-2-deoxystreptamine-4-N-(n-propylimidazole) carbamate (3c)

General procedure A was employed for the reaction between compound 2 (100 mg) and commercially available 1-(3-aminopropyl)imidazole (21.3 μL). Compound 3c was obtained after purification by flash chromatography on a silica gel column using a mixture CH2Cl2/MeOH 95:5 as a white solid in 80% yield (76 mg). RF = 0.53 (CH2Cl2/MeOH 9:1); 1H NMR (200 MHz, CD3OD) 𝛿 (ppm): 7.75 (br s, 1H), 7.18 (br s, 1H), 7.00 (br s, 1H), 4.83–4.79 (m, 1H), 4.07 (t, J = 6.2 Hz, 2H), 3.72–3.43 (m, 4H), 3.11 (t, J = 6.2 Hz, 2H), 2.18–2.09 (m, 1H), 1.97 (quintuplet, J = 6.2 Hz, 2H), 1.60–1.50 (m, 8H), 1.45–1.29 (m, 21H,); 13C NMR (50 MHz, CD3OD) 𝛿 (ppm): 158.5, 157.7, 135.5, 120.8, 113.3, 112.4, 80.3, 79.7, 75.5, 52.4, 45.2, 38.5, 37.3, 37.2, 32.5, 28.7, 26.1, 24.7; MS (ESI): m/z 594.4 [M+H]+ (theoretical m/z 594.3).

4.10. 1,3-Bis-N-(tert-butyloxycarbonyl)-5,6-O-cyclohexylidene-2-deoxystreptamine-4-N-(benzimidazole)carbamate (3d)

General procedure A was employed for the reaction between compound 2 (100 mg) and commercially available 2-aminobenzimidazole (21.3 mg). Compound 3d was obtained after purification by flash chromatography on a silica gel column using a mixture cyclohexane /EtOAc 1:1 as a white solid in 67% yield (64.4 mg). RF = 0.23 (cyclohexane/EtOAc 6:4); 1H NMR (200 MHz, DMSO-d6) 𝛿 (ppm): 7.69 (br s, 1H), 7.19–7.11 (m, 4H), 7.00–6.92 (m, 1H), 5.13 (t, J = 10.3 Hz, 1H), 4.09–3.97 (m, 2H), 3.74–3.76 (m, 1H), 1.95–1.90 (m, 1H), 1.55–1.13 (m, 29H); 13C NMR (50 MHz, DMSO-d6) 𝛿 (ppm): 155.1, 154.9, 153.3, 150.4, 142.8, 129.9, 120.0, 115.3, 114.3, 111.3, 78.0, 77.9, 77.8, 76.9, 35.9, 35.8, 28.2, 23.4, 23.3; MS (ESI) m/z 602.2 [M+H]+ (theoretical m/z 602.3).

4.11. 1,3-Bis-N-(tert-butyloxycarbonyl)-5,6-O-cyclohexylidene-2-deoxystreptamine-4-N-(pyridine)carbamate (3e)

General procedure A was employed for the reaction between compound 2 (100 mg) and commercially available 3-aminopyridine (16.9 mg). The reaction mixture was heated to 50 °C. Purification by flash chromatography on a silica gel column using a mixture CH2Cl2/MeOH 95:5 afforded desired compound 3e as a white solid in 33% yield (29.7 mg). RF = 0.46 (CH2Cl2/MeOH 98:2); 1H NMR (200 MHz, CD3OD) 𝛿 (ppm): 8.64 (br, 1H), 8.19 (dd, J = 4.1, 2.3 Hz), 8.00 (dd, J = 4.1, 2.3 Hz), 7.40 (q, J = 4.1 Hz, 1H), 5.02–4.97 (m, 1H), 3.80–3.47 (m, 4H), 2.13 (td, J = 6.3, 4.1 Hz, 1H), 1.60–1.50 (m, 9H), 1.46–1.20 (m, 20H); MS (ESI) m/z 563.5 [M+H]+ (theoretical m/z 563.3).

4.12. 1,3-Bis-N-(tert-butyloxycarbonyl)-5,6-O-cyclohexylidene-2-deoxystreptamine-4-N-(D3) carbamate (3f)

General procedure A was employed for the reaction between compound 2 (100 mg) and N-3-(1-(3-aminopropyl-1H-imidazol-4-yl)phenyl)benzamide (78.1 mg). The reaction mixture was heated to 50 °C. Purification by flash chromatography on a silica gel column using a mixture CH2Cl2/MeOH 95:5 afforded desired compound 3e as a white solid in 33% yield (41.6 mg). RF = 0.45 (CH2Cl2/MeOH 9:1); 1H NMR (200 MHz, CD3OD) 𝛿 (ppm): 9.57 (s, 1H), 8.30 (s, 1H), 8.05 (d, J = 3.0 Hz, 2H), 7.80–7.50 (m, 8H), 7.35–7.25 (m, 1H), 6.70–6.60 (m, 1H), 6.40–6.30 (m, 1H), 6.10–6.00 (m, 1H), 5.00–4.90 (m, 1H), 4.14 (t, J = 2.5 Hz, 2H), 3.90–3.80 (m, 1H), 3.80–3.60 (m, 4H), 3.00–2.90 (m, 2H), 2.30–2.20 (m, 1H), 1.60–1.50 (m, 11H), 1.41 (s, 18H); 13C NMR (50 MHz, CD3OD) 𝛿 (ppm): 171.3, 166.3, 157.6, 157.4, 156.1, 140.5, 168.7, 136.7, 136.4, 132.3, 129.5, 129.2, 128.4, 120.9, 118.9, 117.3, 116.3, 112.2, 79.0, 74.7, 55.0, 52.5, 44.7, 38.5, 37.5, 37.0, 36.9, 25.6, 24.4; MS (ESI) m/z 563.5 [M+H]+ (theoretical m/z 563.3).

4.13. 1,3-Bis-N-(tert-butyloxycarbonyl)-5,6-O-cyclohexylidene-2-deoxystreptamine-4-N-(n-butyl) carbamate (3g)

General procedure B was employed for the reaction between compound 1 (100 mg) and butyl isocyanate (38.3 μL). Compound 3g was obtained after purification of the crude product by flash chromatography on a silica gel column using a mixture cyclohexane/EtOAc 7:3 as a white solid in 90% yield (112 mg). RF = 0.61 (cyclohexane/EtOAc 6:4); 1H NMR (200 MHz, CD3OD) 𝛿 (ppm): 4.84–4.74 (m, 1H), 3.70–3.41 (m, 4H), 3.10 (t, J = 6.1 Hz, 2H), 2.17–2.05 (td, J = 4.2, 12.4 Hz, 1H), 1.60–1.50 (m, 9H), 1.55–1.41 (m, 24H), 1.17 (t, J = 6.1 Hz, 1H), 0.95 (t, J = 6.1 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (50 MHz, CD3OD) δ (ppm): 158.4, 157.7, 113.3, 79.7, 79.7, 75.3, 52.4, 41.5, 37.3, 33.1, 28.7, 26.1, 24.7, 20.9, 14.16; MS (ESI) m/z 542.4 [M+H]+ (theoretical m/z 542.3).

4.14. 1,3-Bis-N-(tert-butyloxycarbonyl)-5,6-O-cyclohexylidene-2-deoxystreptamine-4-N-[n-ethyl-(2′,4′-dichlorophenyl)] carbamate (3h)

General procedure B was employed for the reaction between compound 1 (100 mg) and 2,4-dichloro-1-(2-isocyanatoethyl)benzene (56 μL). Compound 3h was obtained after purification of the crude product by flash chromatography on a silica gel column using a mixture cyclohexane/EtOAc 85:15 as a white solid in 56% yield (85 mg). RF = 0.64 (cyclohexane/EtOAc 6:4); 1H NMR (200 MHz, acetone-d6) 𝛿 (ppm): 7.46–7.30 (m, 3H), 6.57 (br, 1H), 4.92–4.82 (m, 1H), 3.77–3.53 (m, 4H), 3.39–3.29 (m, 2H), 3.00–2.89 (m, 2H), 2.31–2.24 (m, 1H), 1.60–1.50 (m, 9H), 1.62–1.28 (m, 20H); 13C NMR (50 MHz, Acetone-d6) δ (ppm): 157.1, 156.1, 136.9, 135.4, 133.3, 133.2, 129.7, 128.1, 112.2, 79.1, 78.9, 74.7, 52.5, 49.2, 41.2, 37.4, 33.1, 28.6, 27.5, 25.7, 24.4; MS (ESI) m/z = 658.1 [M+H]+ (theoretical m/z 658.3).

4.15. 1,3-Bis-N-(tert-butyloxycarbonyl)-5,6-O-cyclohexylidene-2-deoxystreptamine-4-N-[n-ethyl-(4′-fluorophenyl)] carbamate (3i)

General procedure B was employed for the reaction between compound 1 (100 mg) and commercially available 1-fluoro-4-(2-isocyanatoethyl)benzene (49 μL). Compound 3i was obtained after purification of the crude product by flash chromatography on a silica gel column using a mixture cyclohexane/EtOAc 8:2 as a white solid in 59% yield (82 mg). RF = 0.53 (cyclohexane/EtOAc 6:4); 1H NMR (200 MHz, acetone-d6) 𝛿 (ppm): 7.26–6.93 (m, 4H), 4.81–4.77 (m, 1H), 3.71–3.34 (m, 4H), 3.33–3.26 (m, 2H), 2.88–2.77 (m, 2H), 2.16–2.09 (m, 1H), 1.60–1.50 (m, 7H), 1.47–1.29 (m, 22H); 13C NMR (50 MHz, acetone-d6) 𝛿 (ppm): 158.3, 157.7, 136.4, 133.3, 131.6, 131.4, 116.2, 115.8, 113.3, 80.3, 79.7, 75.4, 71.34, 52.4, 43.5, 37.3, 37.3, 36.2, 28.7, 26.11, 24.74, 23.94; MS (ESI): m/z = 608.1 [M+H]+ (theoretical m/z 608.3).

4.16. 2-Deoxystreptamine-4-O-(N-phenyl) carbamate (4a)

General procedure C was applied for the protection of compound 3a (50 mg, 0.087 mmol) in the presence of TFA (323 μL, 50 equiv) and triethylsilane (TIS, 0.89 μL, 4.3 nmol, 0.05 equiv) in a mixture of CH2Cl2 and H2O (2.6 mL, 3:1). Compound 4a was obtained as a white solid in 44% yield (20 mg). tR = 0.68 min (analytical HPLC method); 1H NMR (200 MHz, CD3OD) 𝛿 (ppm): 7.33–7.23 (m, 5H), 4.77–4.67 (m, 1H), 4.34 (q, J = 15.2 Hz, 2H), 3.68–3.38 (m, 3H), 3.25–3.22 (m, 1H), 2.48–2.41 (m, 1H), 1.90–1.69 (m, 1H); 13C NMR (50 MHz, CD3OD) 𝛿 (ppm): 156.2, 140.1, 129.5, 128.8, 128.4, 128.2, 76.2 75.2, 51.3, 45.9, 30.1; HRMS (ESI) m/z = 296.16061 [M+H]+ (C14H22O4N3 requires 296.16048).

4.17. 2-Deoxystreptamine-4′-O-[N-m-fluorophenyl]-N-methyl carbamate (4b)

General procedure C was applied for the deprotection of compound 3b (80 mg, 0.13 mmol) in the presence of TFA (489 μL, 50 equiv) and TIS (1.33 μL, 6.5 mmol, 0.05 equiv) in a mixture of CH2Cl2 and H2O (4.5 mL, 3:1). Compound 4b was obtained as a white solid in 67% yield (48 mg). tR = 0.79 min (analytical HPLC); 1H NMR (500 MHz, CD3OD) 𝛿 (ppm): two isomers (minor one in italics): 7.37–7.32 (m, 1H), 7.18–6.98 (m, 3H), 4.84–4.73 (m, 2H), 4.37 (d, J = 16.0 Hz, 2H), 4.30 (d, J = 15.5 Hz, 1H), 3.56–3.45 (m, 3H), 3.26–3.20 (m, 1H), 2.96 (s, 3H), 2.87 (s, 3H), 2.49–2.47 (m, 1H), 1.90–1.83 (m, 1H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CD3OD) 𝛿 (ppm) two isomers (minor one in italics): 165.5, 163.6, 141.5, 131.5, 124.7, 115.6, 115.1, 76.4, 77.4, 74.9, 54.8, 53.2, 52.9, 51.3, 51.2, 34.7, 34.4, 30.3; HRMS (ESI) m/z = 328.16681 [M+H]+ (C15H23O4N3F requires 328.16671).

4.18. 2-Deoxystreptamine-4-O-(N-propylimidazole) carbamate (4c)

General procedure C was applied for the deprotection of compound 3c (78 mg, 0.13 mmol) in the presence of TFA (483 μL, 50 equiv) and TIS (1.33 μL, 6.5 mmol, 0.05 equiv) in a mixture of CH2Cl2 and H2O (4.2 mL, 3:1). Compound 4c was obtained as a colorless solid in 61% yield (25 mg). tR = 0.68 min (analytical HPLC); 1H NMR (200 MHz, CD3OD) 𝛿 (ppm): 8.96 (br s, 1H), 7.69 (br s, 1H), 7.58 (br s, 1H), 4.82–4.76 (m, 1H), 3.45 (t, J = 6.3, 2H), 3.49–3.16 (m, 4H), 3.14 (t, J = 6.3 Hz, 2H), 2.51–2.40 (m, 1H), 2.15–2.11 (m, 2H), 1.63–1.29 (m, 29H); 13C NMR (50 MHz, CD3OD) 𝛿 (ppm): 158.4, 133.2, 121.7, 111.4, 76.1, 75.2, 74.2, 51.4, 49.0, 38.1, 38.1, 31.5, 23; HRMS (ESI) m/z = 314.18240 [M+H]+ (C13H24O4N5 requires 314.18228).

4.19. 2-Deoxystreptamine-4-O-[N-benzimidazole] carbamate (4d)

General procedure C was applied for the deprotection of compound 3d (50 mg, 0.083 mmol) in the presence of TFA (726 μL, 50 equiv) and TIS (0.85 μL, 4.1 mmol) in a mixture of CH2Cl2 and H2O (3 mL, 2:1). Compound 4d was obtained as a colorless solid in 30% yield (13.7 mg). tR = 1.23 min (analytical HPLC). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CD3OD) 𝛿 (ppm): 7.38–7.25 (m, 4H), 4.81–4.68 (m, 1H), 3.59–3.45 (m, 3H), 3.29–3.16 (m, 1H), 2.51–2.40 (m, 1H), 1.94–1.81 (m, 1H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CD3OD) 𝛿 (ppm): 163.5, 158.4, 131.0, 124.7, 112.3, 81.3 79.3, 74.7, 51.2, 29.9; HRMS (ESI) m/z = 322.15103 [M+H]+ (C14H20O4N5 requires 322.15098).

4.20. 2-Deoxystreptamine-4-O-(N-pyridine) carbamate (4e)

General procedure C was applied for the deprotection of compound 3e (40 mg, 0.071 mmol) in the presence of TFA (264 μL, 50 equiv) and TIS (0.72 μL, 3.5 mmol) in a mixture of CH2Cl2 and H2O (2.2 mL, 3:1). Compound 4e was obtained as a colorless solid in 22% yield (8.0 mg). tR = 0.63 min (analytical HPLC); 1H NMR (200 MHz, CD3OD) 𝛿 (ppm): 8.97 (br, 1H), 8.41 (br, 1H), 8.28 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.75 (br, 1H), 4.95–4.80 (m, 1H), 3.67–3.19 (m, 3H), 3.27–3.19 (m, 1H), 2.54 – 2.43 (td, J = 12.1, 4.2 Hz, 1H), 1.97–1.78 (q, J = 12.1 Hz); HRMS (ESI) m/z = 283.14020 [M+H]+ (C12H19O4N4 requires 283.14008).

4.21. 2-Deoxystreptamine-4-N-(D3) carbamate (4f)

General procedure C was applied to compound 3f (100 mg, 0.127 mmol) in the presence of TFA (490 μL, 50 equiv) in a mixture of CH2Cl2 and H2O (2 mL, 3:1). Compound 4f was obtained as a colorless solid in 75% yield (70.0 mg). tR = 1.48 min (analytical HPLC); 1H NMR (500 MHz, CD3OD) 𝛿 (ppm): 9.57 (s, 1H), 8.30 (s, 1H), 8.05 (d, J = 20 Hz, 2H), 7.80–7.50 (m, 8H), 7.35–7.25 (m, 1H), 6.60–6.50 (m, 1H), 6.35–6.25 (m, 1H), 5.00–4.90 (m, 1H), 4.20–4.10 (m, 2H), 3.70–3.50 (m, 4H), 3.00–2.90 (m, 2H), 2.35–2.25 (m, 1H), 1.70–1.50 (m, 10H), 1.40–1.50 (m, 19H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CD3OD) 𝛿 (ppm): 168.9, 158.3, 140.9, 137.2, 135.9, 135.8, 133.0, 130.9, 129.5, 128.7, 128.5, 123.1, 122.5, 119.2, 119.0, 75.9, 75.1, 74.1, 51.1, 50.0, 47.6, 38.0, 31.2, 29.8, 23.7; HRMS (ESI) m/z = 509.25095 [M+H]+ (C26H33O5N6 requires 509.25069).

4.22. 2-Deoxystreptamine-4-O-(N-butyl) carbamate (4g)

General procedure C was applied to compound 3g (100 mg, 0.18 mmol) in the presence of TFA (668 μL, 50 equiv) in a mixture of CH2Cl2 and H2O (4.5 mL, 3:1). Compound 4g was obtained as a colorless solid in 88% yield (77.5 mg). tR = 0.77 min (analytical HPLC); 1H NMR (200 MHz, CD3OD) 𝛿 (ppm): 4.71–4.61 (m, 1H), 3.45–3.06 (m, 6H), 2.46–2.40 (m, 1H), 1.89–1.77 (m, 1H), 1.55–1.27 (m, 4H), 0.94 (t, J = 6.3 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (50 MHz, CD3OD) 𝛿 (ppm): 158.4, 76.1, 75.1, 74.3, 51.3, 41.8, 40.3, 32.9, 21.0, 14.1; HRMS (ESI) m/z = 262.17624 [M+H]+ (C11H24O3N3 requires 262.17613).

4.23. 2-Deoxystreptamine-4-O-[N-(2′,4′-dichlorophenyl)ethyl] carbamate (4h)

General procedure C was applied to compound 3h (55 mg, 0.084 mmol) in the presence of TFA (312 μL, 50 equiv) in a mixture of CH2Cl2 and H2O (2.5 mL, 3:1). Compound 4h was obtained as a white solid in quantitative yields (50.8 mg). tR = 0.69 min (analytical HPLC); 1H NMR (500 MHz, CD3OD) 𝛿 (ppm): 7.44–7.43 (m, 1H), 7.35–7.24 (m, 2H), 4.73–4.63 (m, 1H), 3.51–3.37 (m, 3H), 3.35–3.32 (m, 3H), 2.99–2.91 (m, 2H), 2.47–2.40 (m, 1H), 1.90–1.72 (m, 1H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CD3OD) 𝛿 (ppm): 158.3, 136.9, 135.9, 134.0, 133.3, 130.1, 76.3, 75.3, 74.1, 51.2, 41.8, 33.8, 30.2; HRMS (ESI) m/z = 378.09857 [M+H]+ (C15H22O4N3Cl2 requires 378.09819).

4.24. 2-Deoxystreptamine-4-O-[4′-(fluorophenyl)ethyl] carbamate (4i)

General procedure C was applied to compound 3i (45 mg, 0.079 mmol) in the presence of TFA (293 μL, 50 equiv) in a mixture of CH2Cl2 and H2O (1.5 mL, 3:1). Compound 4i was obtained as a colorless solid in 52% yield (23 mg). tR = 0.95 min (analytical HPLC); 1H NMR (500 MHz, CD3OD) 𝛿 (ppm): 7.28–7.22 (m, 2H), 7.21–6.94 (m, 2H), 4.74–4.64 (m, 1H), 3.49–3.37 (m, 3H), 3.31–3.27 (m, 2H), 3.24–3.20 (m, 1H), 2.84–2.77 (m, 2H), 2.49–2.41 (m, 1H), 1.91–1.72 (m, 1H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CD3OD) 𝛿 (ppm): 158.2, 156.6, 131.6, 131.4, 116.3, 115.9, 76.0, 74.9, 74.2, 51.2, 43.8, 36.0, 30.0; HRMS (ESI) m/z = 328.16678 [M+H]+ (C15H23FN3O4 requires 328.16726).

Interestingly, 2D-NMR analysis of conjugate 3b as well as its corresponding deprotected form 4b containing 2-DOS connected to a 2-fluoro-N-methylbenzylamine moiety clearly showed two distinct rotamers. This could be due to the presence of the methyl group on the nitrogen atom of the carbamate linker, which probably impedes free rotation of the carbamate function. In the absence of this methyl group, no steric effect is found to restrict this free rotation, thus no observation of two conformations was detected by NMR analysis.

5. Biochemistry

5.1. RNA and biochemicals

The buffers and solutions used in the fluorescence experiments were filtered through Millipore filters (0.22 mm; GP ExpressPLUS membrane). Human recombinant Dicer enzyme (Genlantis) had a concentration of 0.5 U/μL. Tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane hydrochloride (Tris–HCl) 20 mM (pH 7.4), containing 12 mM NaCl, 3 mM MgCl2, and 1 mM DTT was used for the FRET assays and KD determination. RNA oligonucleotides were purchased from IBA GmbH (Goettingen, Germany). RNA folding was performed in TRIS buffer upon incubation at 90 °C for 2 min, 4 °C for 10 min, and slowly returning to room temperature for 15 min.

For pre-miR-372:

5′-FAM-GUGGGCCUCAAAUGUGGAGCACUAUUCUGAUGUCCAAGUGGAAAGUGCUGCGACAUUUGAGCGUCAC-3′-DABCYL (ODN1)

5′-FAM-GUGGGCCUCAAAUGUGGAGCACUAUUCUGAUGUCCAAGUGGAAAGUGCUGCGACAUUUGAGCGUCAC-3′ (ODN2)

For pre-miR-17:

5′-FAM-GUCAGAAUAAUGUCAAAGUGCUUACAGUGCAGGUAGUGAUAUGUGCAUCUACUGCAGUGAAGGCACUU GUAGCAUUAUGGUGAC-3′-DABCYL (ODN3)

5′-FAM-GUCAGAAUAAUGUCAAAGUGCUUACAGUGCAGGUAGUGAUAUGUGCAUCUACUGCAGUGAAGGCACUU GUAGCAUUAUGGUGAC-3′ (ODN4)

For pre-miR-18a:

5′-FAM-UGUUCUAAGGUGCAUCUAGUGCAGAUAGUGAAGUAGAUUAGCAUCUACUGCCCUAAGUGCUCCUUCUGGCA-3′-DABCYL (ODN5)

5′-FAM-UGUUCUAAGGUGCAUCUAGUGCAGAUAGUGAAGUAGAUUAGCAUCUACUGCCCUAAGUGCUCCUUCUGGCA-3′ (ODN6)

For pre-miR-148a:

5′-FAM-GAGGCAAAGUUCUGAGACACUCCGACUCUGAGUAUGAUAGAAGUCAGUGCACUACAGAACUUUGUCUC-3′-DABCYL (ODN7)

5′-FAM-GAGGCAAAGUUCUGAGACACUCCGACUCUGAGUAUGAUAGAAGUCAGUGCACUACAGAACUUUGUCUC-3′ (ODN8)

DNA duplex sequence:

5′-CGTTTTAAATTTTGC-3′ (ODN9) and 5′-GCTTTTAAATTTTGC-3′

5.2. FRET Dicer assay

The Dicer assay was performed in 384-well plates (Greiner bio-one) in a final volume of 40 μL by using a 5070 EpMotion automated pipetting system (Eppendorf). Each experiment was performed in duplicate and repeated three times. A beacon of ODN1, ODN3, ODN5, or ODN7 at 50 nM was used in each well and the reaction mixtures containing inhibitors were preincubated at rt for 30 min. Human recombinant Dicer (0.25 U; Genlantis) or Escherichia coli RNase III (0.25 U, Ambion) were added to the reaction mixtures. For the IC50 experiments, each ligand was added in 12 dilutions (0.244 pM–500 μM). The fluorescence increase was measured after 1 h incubation at 37 °C on a GeniosPro (Tecan) with excitation and emission filters of l = 485 ± 10 and 535 ± 15 nm, respectively. Each point was measured ten times with an integration time of 500 ms and then averaged. The inhibition data were analyzed using nonlinear regression in Prism 5 (GraphPad Software) following the equation: Y = bottom + (top − bottom)/(1 + 10[(log(IC50) − X)⋅Hills Slope]) where X is log(concentration) and Y the fluorescence intensity.

5.3. Binding experiments and KD determination

Binding experiments were performed in 384-well plates (Greiner bio-one) in a final volume of 60 mL by using a 5070 EpMotion automated pipetting system (Eppendorf). Each experiment was performed in duplicate and repeated at least three times. A beacon (ODN2, ODN4, ODN6 and ODN8) was used at 10 nM in each well. Each ligand was added in 15 dilutions (0.030 nM–0.5 mM). The fluorescence increase measured after 4 h on a GeniosPro (Tecan) with excitation and emission filters of l = 485 ± 10 and 535 ± 15 nm, respectively. Each point was measured ten times with an integration time of 500 ms and then averaged. The binding data were analyzed using Graphpad Prism 5 software. Unless otherwise stated, the binding profiles were well fitted by a simple model that assumed 1:1 stoichiometry. In the competition experiments, 100 equiv of tRNA structured as pre-miR-372 beacon were added to the RNA solution and 100 equiv of duplex DNA (mixture of ODN9 and ODN10 incubated at 90 °C for 5 min then slowly returned at rt) were added to the RNA solution.

5.4. Molecular modeling and docking

The MC-Fold/MC-Sym pipeline (http://www.major.iric.ca/MC-Pipeline/) is a web-hosted service for RNA secondary and tertiary structure prediction. The pipeline consists in uploading RNA sequence to MC-Fold, which outputs secondary structures that are directly input to MC-Sym, which outputs tertiary structures. Pre-miRNA sequences were obtained from the miRBase database (http://www.mirbase.org/). The hairpin loops of pre-miR-372 and pre-miR-17 were chosen to predict the 3D structure using the MC-Fold/MC-Sym pipeline. Energy optimization was further conducted on the 3D model using the TINKER Molecular Modeling Package (http://dasher.wustl.edu/tinker/). For docking with AutoDock, polar hydrogen atoms, Kollman united charges and solvent parameters were applied to the RNA using pmol2q script. This script converts the .pdb file format of the RNA template to the .pdbqt file format that is compatible with AutoDock program version 4 (http://autodock.scripps.edu/). Pre-miR-372/4f and pre-miR17/4f molecular docking were conducted using AutoDock program version 4. The rotational bonds of the ligand were treated as flexible, whereas the receptor was kept rigid. Grid box was fixed in order to include the entire RNA sequence. RNA–ligand interactions were analyzed and visualized using Discovery Studio Visualizer version 4.1 (https://www.3ds.com/fr/products/biovia/discovery-studio).

Declaration of interests

The authors do not work for, advise, own shares in, or receive funds from any organization that could benefit from this article, and have declared no affiliations other than their research organizations.

CC-BY 4.0

CC-BY 4.0