Dedicated to the memory of Bertrand Carboni.

1. Introduction

Rhenium(I) tricarbonyl d6 complexes are well-known emissive complexes, notably for their efficient visible-light and long-lived luminescence [1]. Owing to the strong spin–orbit coupling of the heavy rhenium atom, these complexes exhibit efficient room-temperature (rt) phosphorescence. They have been investigated for diverse applications, including photoredox chemistry [2, 3], chemo- and electrochemiluminescence [4, 5], chemical and biological sensing [6, 7], bioconjugation [8, 9], and as dopants in organic light-emitting diodes (OLEDs) [10]. They can be easily synthesized by refluxing in toluene a rhenium(I) source (commonly ReX(CO)5, where X = Cl, Br) with a bidentate N,N or C,N ligand (such as a 2,2′-bipyridine, terpyridine, or pyridyl-N-substituted heterocyclic carbene), yielding complexes of general formula ReL2X(CO)3, with L2 representing the bidentate ligand. An attractive research direction involves the introduction of chirality into L2, for instance helical chirality, and combination with chirality at the rhenium center. Helicenes are helically chiral molecules obtained from the ortho-fusion of aromatic rings [11]. Over the past two decades, our group has focused on synthesizing helicenic structures, incorporating coordinating units to produce helically chiral ligands and a broad range of chiral metal complexes upon subsequent coordination [12, 13]. This approach enables the combination of the chirality-driven properties of the ligand with the intrinsic photophysical, chiroptical, and magnetic characteristics of the chosen metal ion, thereby generating unique functional molecular materials. In this short account, the main results on rhenium complexes bearing helicenic ligands functionalized with 2,2′-bipyridine or phenanthroline-type coordinating units are reviewed. These complexes exhibited intense electronic circular dichroism, and circularly polarized long-lived phosphorescence, appealing properties for the development of chiral photoactive materials. The specific stereochemical features that significantly influence the properties of these chiral emitters are also highlighted.

2. Results and discussion

2.1. Synthesis and characterization of helicenic N,N ligands

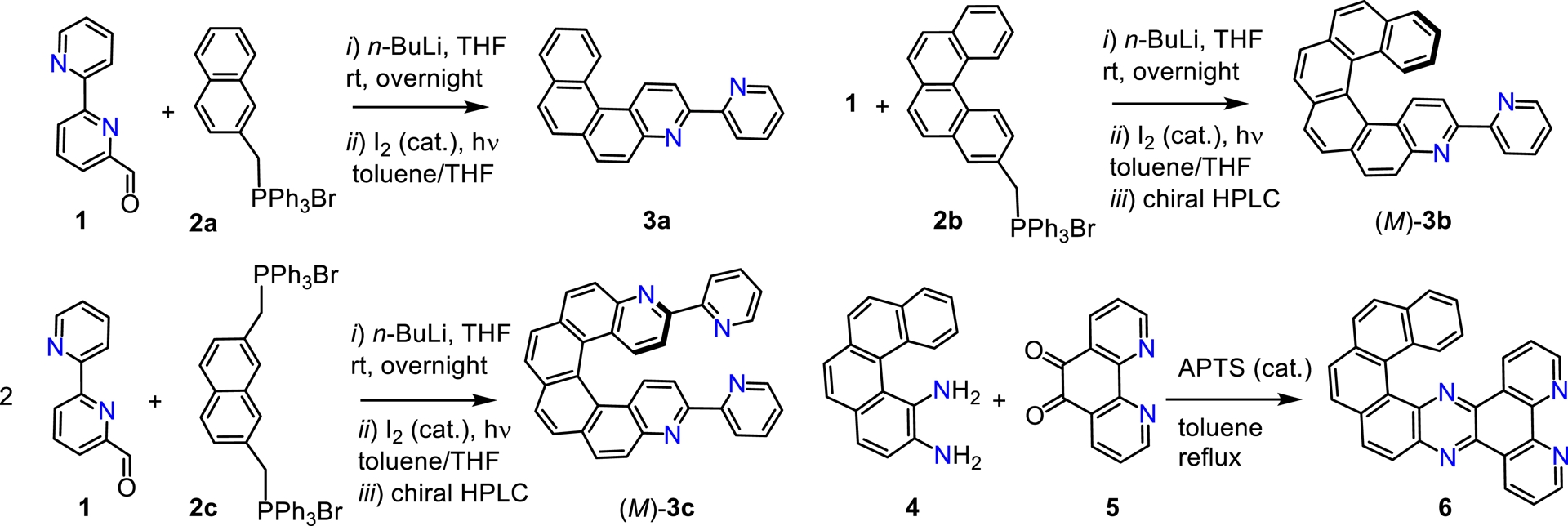

2,2′-Bipyridine (bipy) units are widely used ligands in coordination chemistry, enabling access to a broad range of luminescent metal-based molecular materials [14]. Our group was the first to prepare helical bipy ligands, i.e., bipy units fused with a helicenic moiety, actually consisting of 4-aza[n]helicenes 3-substituted by a 2-pyridyl unit. As described in Scheme 1, we developed in a systematic fashion [4]helicene 3a [15, 16], [6]helicene 3b [15, 16], with a single bipyridine unit at one end, along with [6]helicene 3c [17] containing a bipyridine unit at both termini. We started our two-step synthesis from 2,2′-bipyridine-6-carboxaldehyde 1, by a Wittig reaction with either 2-naphthyl phosphonium bromide 2a, 2-methylbenzophenanthrene phosphonium bromide 2b, or naphtyl-2,7-dimethyl-di-phosphonium bromide 2c, respectively, followed by a Mallory reaction (photocyclization under oxidative conditions) [18]. Regarding [4]helicene-pyrazino[2,3-f][1,10]phenanthroline (6), incorporating a dppz unit (dppz = benzo[h]dipyrido[3,2-a:2′,3′-c]phenazine) [19], it was obtained from condensation of a 1,2-[4]helicene-diamine 4 with 1,10-phenanthroline-5,6-dione 6 (Scheme 1) using catalytic para-toluene sulfonic acid [20]. A similar strategy was recently utilized by others to generate pyrazino-phenanthryl-based helicenic systems displaying high photoconductive properties [21].

Synthetic procedures used to prepare helicenic N,N ligands 3a–3c and 6 [15, 17, 20].

The photophysical properties of ligands 3b, 3c, and 6 were studied in detail. These three compounds exhibited absorption spectra in the UV–visible (UV–Vis) region between 270 and 500 nm. Furthermore, helicene derivatives 3b and 3c were found to display vibronically structured blue fluorescence with moderate quantum yields. For instance, in CH2Cl2 solution at rt, ligand 3b exhibited a structured blue fluorescence at 421 nm, with a vibronic progression of 1400 cm−1 (quantum yield Φ = 8.4%) (Table 1). Ligand 6 was found to emit redshifted fluorescence centered at 515 nm, which appeared broad and unresolved as a result of the presence of charge transfer (CT), and with a higher quantum yield of 29%. Interestingly, long-lived phosphorescence signals emerging around 530 nm were observed for 3b,c and at 560 nm for 6 when cooling down to low temperature (77 K) (Figure 3d).

Absorption data, emission maxima, quantum yields, lifetimes and emission dissymmetry factors of the compounds described. In dichloromethane at 298 ± 3 K, except otherwise indicated

| Compound | Absorption 𝜆max (nm) (𝜀 (×103 M−1⋅cm−1)) | Emission 𝜆max (nm) | Φ (%) | 𝜏 (ns)a | CPL glum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3b | 240 (35.0), 266 (55.8), 322 (27.0), 353 (14.4), 372 (10.2), 393 (2.63), 417 (1.80) | 421, 445, 473sh | 8.4 | 6.6 | +3.4 × 10−3

[(P)-3b] [15] |

| 3c | 242 (35.1), 272 (60.3), 286 (65.3), 344 (26.5), 366sh (20.2), 398 (3.50), 420 (2.75) | 422, 448, 476, 513sh | 8.6 | 5.1 | +8.6 × 10−3

[(P)-3c] [15] |

| 6 | 260 (85), 288 (67), 350 (33), 435 (13), 410 (16) | 515 (CH2Cl2) 560 (77 K) |

29 | 5.8, 2.8 | n.d. |

| 7a | 243 (34.5), 273 (30.3), 318 (30.3), 330 (43.2), 398 (12.7) | 678 | 0.11 | 25 | n.d. |

| 8a | 251 (54.9), 273 (51.9), 326sh (35.9), 337 (46.6), 403 (14.6), 422 (15.2) | 585, 618 | 16 | 67 000 | n.d. |

| 9a | 248 (35.7), 280 (34.2), 327sh (27.3), 338 (37.7), 408 (13.5), 422 (13.9) | 595, 623 | 8.3 | 11 500 | n.d. |

| 7b1 | 236 (45.9), 277 (49.9), 307 (28.2), 339 (21.3), 420 (7.96), 444 (7.30) | 680 | 0.13 | 27 | n.d. |

| 7b2 | 237 (59.8), 278 (65.0), 305sh (36.3), 344 (26.3), 418 (11.0), 445 (10.2) | 673 | 0.16 | 33 | +3.1 × 10−3

[(P,ARe)-7b2] [16] |

| 8b1,2 | 272 (48.0), 339 (17.6), 444 (5.6) | 598 | 6 | 79 000 | +1.3 × 10−3

[(P,ACRe)-8b1,2] [16] |

| 10-1 | 283 (46.5), 299 (51.4), 361 (15.5), 387 (15.4), 450 (6.08) | 664 | 0.20 | 38 | +3.4 × 10−3

[(P,ARe,ARe)-10-1] [17] |

| 10-2 | 283 (33.7), 299 (37.9), 359 (12.7), 389 (11.3), 450 (5.09) | 678 | 0.15 | 32 | n.d. |

| 11 | 267 (77), 304 (40), 353 (29), 460 (12) | 518 (CH2Cl2) 560 (77 K) |

2.0 | 1.2, 7.6 | +2.3 × 10−3 at rt +2.9 × 10−2 at 77 K [(P,ACRe)-11] [20] |

a In degassed solution. n.d. not determined.

While benzophenanthryl system 3a was found to be configurationally unstable, hexahelicenic enantiopure (M)- and (P)-3b, and (M)- and (P)-3c could successfully be obtained by HPLC over chiral stationary phases. Unfortunately, due to very poor solubility, attempts to separate the enantiomers of 6 proved unsuccessful. (M) and (P) enantiomers of 3b and 3c displayed the typically strong electronic circular dichroism (ECD) responses, which are very typical of helicenic organic derivatives [22]. For instance, enantiomer (P)-3b exhibited a very strong negative band at 265 nm and a very strong positive band at 335 nm along with weaker positive bands between 380 and 430 nm (Figure 2a).

3. Coordination to rhenium(I)

3.1. Monometallic helicene–bipy–Re(I) complexes

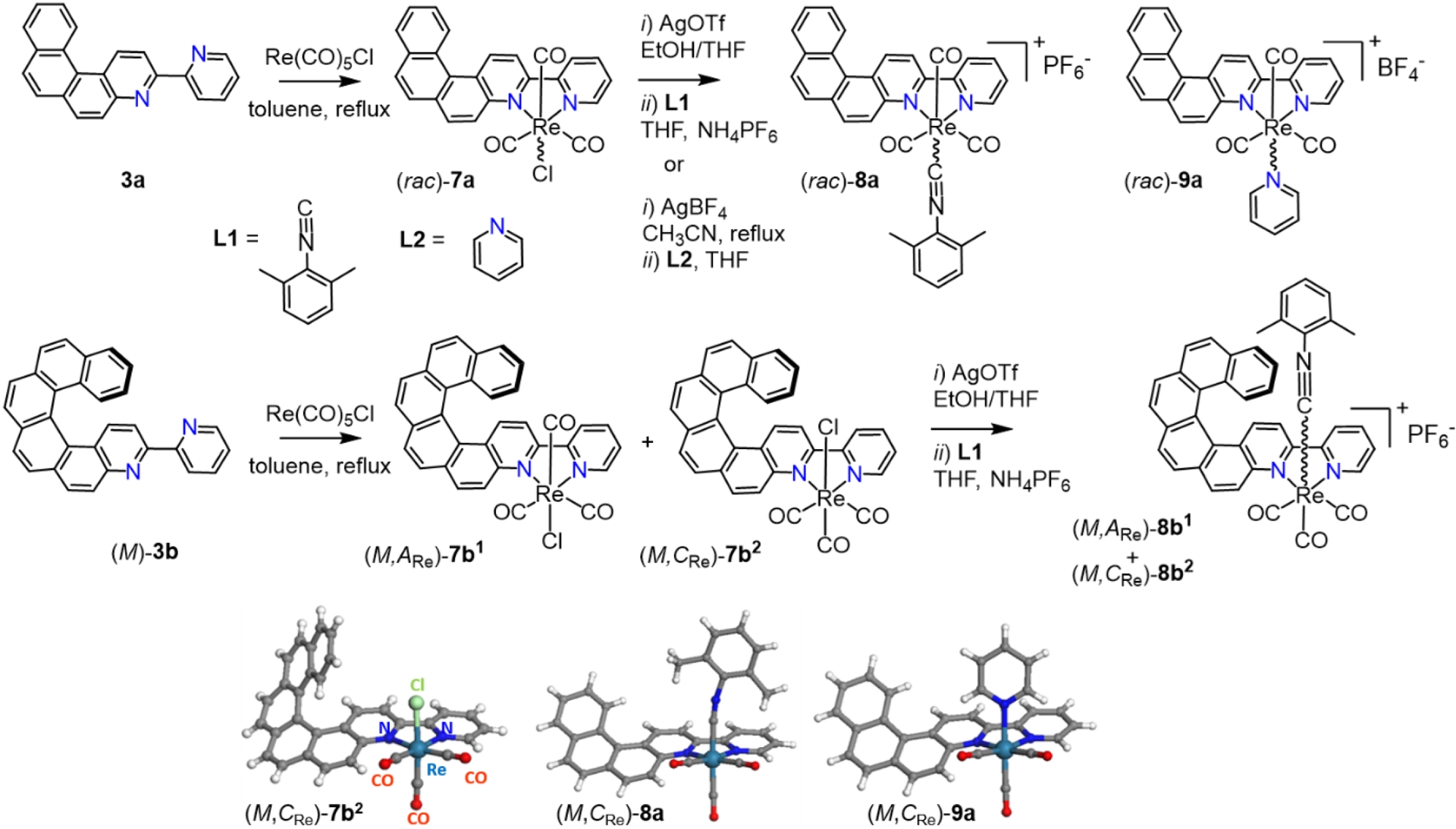

The coordination of 3a and 3b to rhenium(I) was then performed under classical conditions, i.e., by reacting them with Re(CO)5Cl in refluxing toluene and isolating the complexes by simple filtration thanks to their low solubility in toluene (Scheme 2). Specifically, the neutral Re(I) complexes 7a and 7b were synthesized from 4-(2-pyridyl)-5-aza[4]helicene 3a and 4-(2-pyridyl)-5-aza[6]helicene 3b, respectively. In contrast to the starting ligands, Re(I) complexes 7a and 7b displayed red phosphorescence at ∼673–678 nm in CH2Cl2 at rt, but with very low quantum yields (Φ = 0.11–0.13%, Table 1). In order to improve efficiency, charged complexes 8a/8b1,2 and 9a, were readily prepared by direct substitution of the chloride ligand with pyridine or isocyanide. Satisfyingly, these were found to exhibit red phosphorescence with markedly higher quantum yields (6–16%) (Table 1) and much longer lifetimes. From the stereochemical viewpoint, ligand 3a is in average planar and achiral, while ligand 3b adopts helical (P) or (M) chirality. Due to the dissymmetric nature of the bipy ligands, the slightly distorted octahedral rhenium center also becomes chiral, with its configuration described as anticlockwise (ARe) or clockwise (CRe) [23, 24]. Consequently, complex 7a can exist as (ARe)/(CRe) enantiomers, whereas 7b forms two diastereomeric pairs of enantiomers: (P,ARe)/(M,CRe) and (P,CRe)/(M,ARe). In the charged complexes, the Re center readily isomerized, thus yielding inseparable racemic mixtures (8a) or epimeric mixtures (8b1,2). In contrast, enantiomerically and diastereomerically pure samples of 7a and 7b1,2 were successfully isolated by chiral HPLC. Having these species in hand allowed a detailed investigation of their chiroptical properties. For instance, Figure 1a represents the comparison of the ECD spectra of pure stereoisomers of 3b with those of 7b1 and 7b2, while Figure 1c shows the comparison of the calculated ECD spectra of 7b1 and 7b2 with the epimeric mixture of 8b1,2, and Figure 1b presents their CPL (circularly polarized luminescence) responses. The ECD spectra of 7b1,2 and 8b1,2 feature a new low-energy band which was absent in 3b. The calculated ECD spectra revealed that this transition mainly corresponded to the HOMO→LUMO excitation and arose from the π-helical ligand system in the HOMO and the bipy–rhenium fragment, with partial π-extension into the helicenic core in the LUMO. Importantly, ligand 3b, complex 7b2, and complex 8b1,2 were found CPL-active, with emission dissymmetry factors (glum) on the order of 10−3 (Table 1). Theoretical calculations indicated that the emission process involves Re orbitals, enabling the formally spin-forbidden T1→S0phosphorescence transitions via spin–orbit coupling. The reduced metal-orbital participation (lower metal-to-ligand CT [MLCT] character) in the T1 state of 8b1,2 compared with 7b1,2 explained the higher emission efficiency of the charged complexes.

Synthesis of neutral and charged rhenium complexes 7a–9a and enantioenriched (M,ARe)-7b1, (M,CRe)-7b2 and (M,CARe)-8b1,2 from, respectively, [4]helicene-bipy 3a and [6]helicene-bipy (M)-3b. X-ray crystallographic structures of racemic 7b2, 8a, and 9a (only (M,CRe) stereoisomers are shown). Adapted with permission from Ref. [16].

(a) Experimental ECD spectra of enantiopure (M) and (P)-3b and their corresponding enantiopure ReI complexes (M,ARe)-7b1, (P,CRe)-7b1, (M,CRe)-7b2, and (P,ARe)-7b2. Inset: ECD spectra of 7b1 enantiomers between 450 and 550 nm. (b) CPL (upper curves within each panel) and total luminescence (lower curves within each panel) spectra of (M)-3b, (P)-3b, (M,CRe)-7b2, (P,ARe)-7b2, (M,ACRe)-8b1,2, (P,ACRe)-8b1,2 in degassed CH2Cl2 at rt. (c) Calculated ECD spectra of (P,CRe)-7b1, and (P,ARe)-7b2 and Boltzmann-averaged spectrum for (P)-8b1,2 conformers. View of HOMO and LUMO of 7b1 and 8b1. First excitation energies indicated by dots on the abscissa. Adapted with permission from Ref. [16].

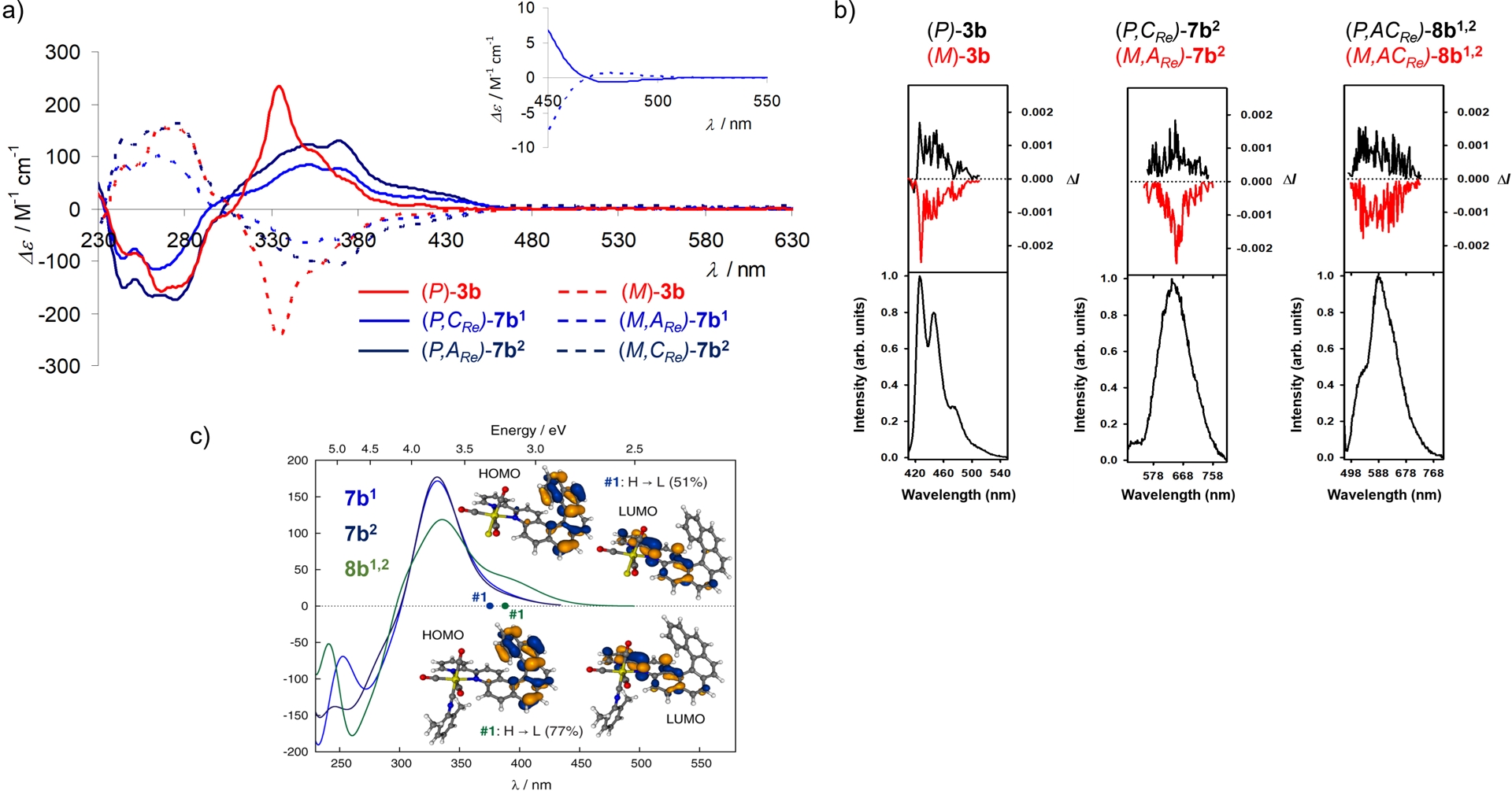

3.2. Bimetallic helicene–bis-bipy–Re(I) complexes

Using the same strategy, the dinuclear Re(I) complexes 10-1 and 10-2 were synthesized from 3,14-bis(2-pyridyl)-4,13-diaza[6]helicene 3c incorporating two bipy units (Scheme 3). Similarly to mono-Re complexes, each Re center in 10-1 and 10-2 adopts a distorted octahedral geometry with fac-oriented carbonyl groups. In 10-1, both chlorides point toward the helicene core, giving C2 symmetry with identical C or A configurations at the two Re centers and a helical angle of 39.13°. In 10-2, one chloride points inward (C) and the other outward (A), breaking the symmetry (C1) and increasing the helical angle to 46.39°. The isomer with both chlorides pointing outward was not observed. X-ray diffraction established the absolute configurations as (M,CRe,CRe)/(P,ARe,ARe) for 10-1 and (M,CRe,ARe)/(P,ARe,CRe) for 10-2, consistent with their respective C2 and C1 symmetry. Incorporation of two Re centers into the helicenic ligand induced a marked redshift of the lowest-energy bands and increased molar absorptivity beyond 375 nm (Table 1). The nature of these excitations in 10-1 and 10-2 was investigated in detail by TDDFT calculations. Bands around 299 nm are assigned to intraligand π–π∗ transitions, while the lower-energy bands corresponded to intra-ligand CT (ILCT) excitations with MLCT contributions. In CH2Cl2 at rt, 10-1 and 10-2 displayed weak, broad red phosphorescence (𝜆max = 673 and 687 nm; Φ = 0.20% and 0.15%; 𝜏 = 38 and 32 ns), typical of 3MLCT emission in Re(CO)3(N,N)Cl complexes. At 77 K, the complexes exhibited structured phosphorescence blueshifted by over 100 nm relative to rt, with 𝜏 over 40 μs. This low-temperature emission closely resembled that of ligand 3c suggesting that a ligand-centered 3π–π∗ state lies below the 3MLCT state under these conditions, with metal coordination slightly stabilizing the π∗ orbitals and accelerating the T1→S0 transition.

(a) Synthesis of dinuclear rhenium(I) complexes (rac)-10-1 and (rac)-10-2 from racemic diaza [6]helicene-bis-bipyridine ligand 3c. (b) X-ray crystallographic molecular structures of 3c, 10-1, and 10-2 (racemic structures, only one enantiomer shown). Adapted with permission from Ref. [17].

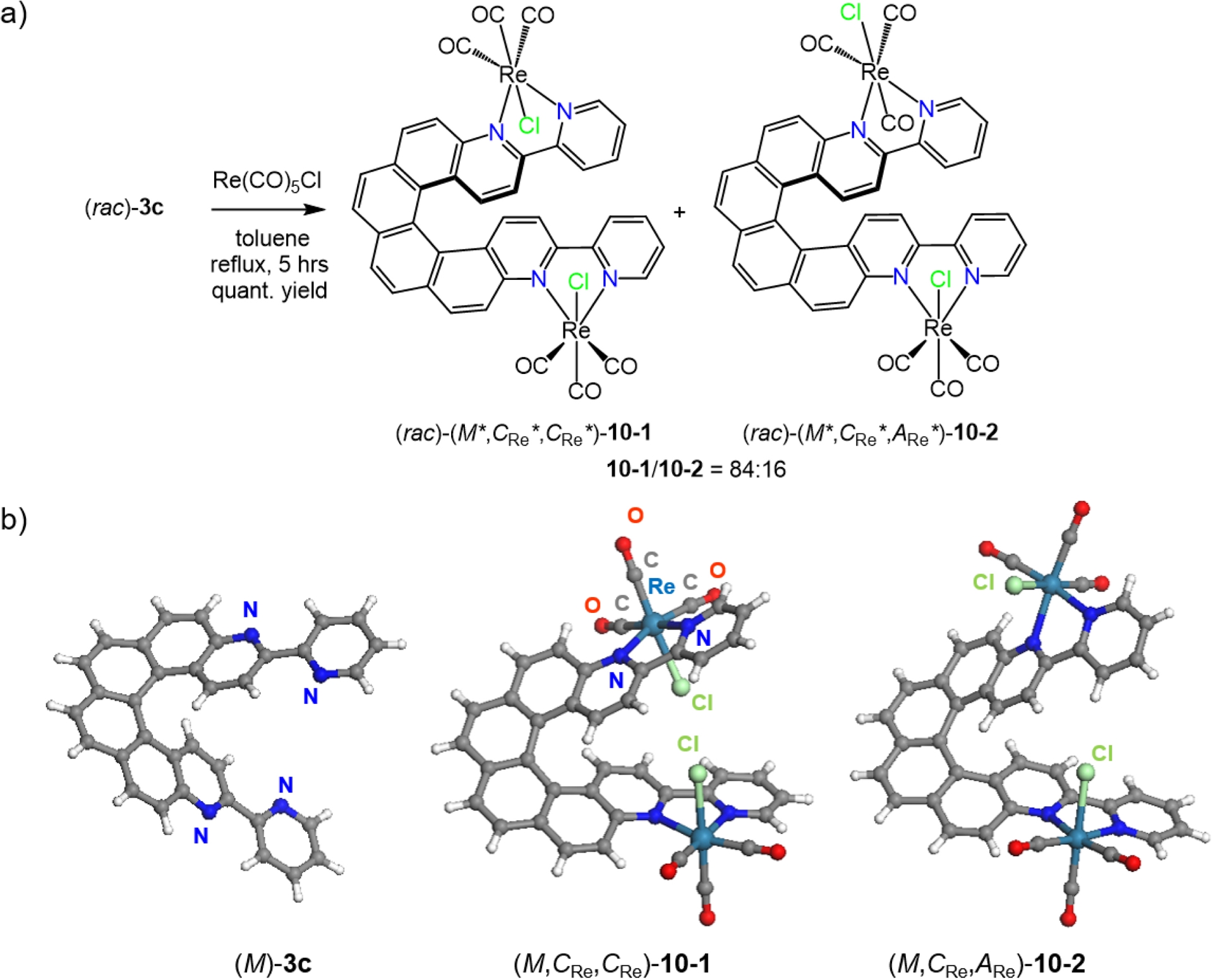

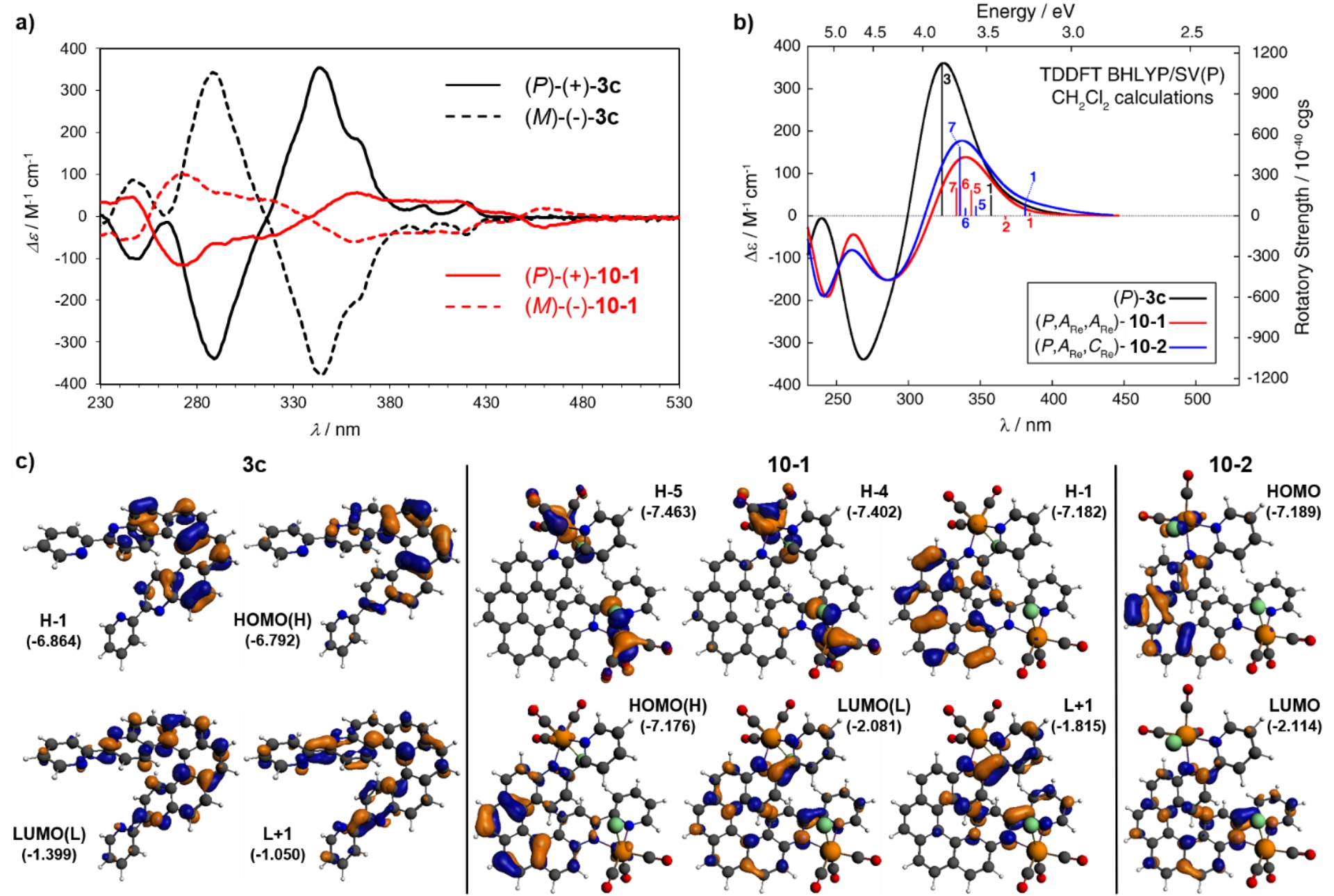

Enantiopure dinuclear Re(I) complexes were prepared from enantiopure ligands. Interestingly, only one diastereomer was formed from each ligand, namely (M,CRe,CRe) and (P,ARe,ARe)-10-1 from (M)- and (P)-3c, respectively, while enantiopure 10-2 was not detected. This selectivity most likely originated from the lower stability of enantiopure 10-2, which under refluxing toluene isomerized to the thermodynamically more stable 10-1. This interpretation was supported by DFT calculations. Figure 2a compares the experimental ECD spectra of the ligand and its complexes. The enantiomers of 10-1 exhibited mirror-image spectra featuring several bands between 272 and 459 nm. The MOs involved in the low-energy intense excitations of 3c and 10-1 are shown in Figure 2c. Transitions of the ligands are dominated by π–π∗ ones, with extended conjugation through the whole system. In complex 10-1, the strong ECD bands mainly arise from metal and halogen to helicene–bis-bipyridine charge transfers (MLCT and halogen-to-ligand CT [XLCT]), with additional helicene ILCT and π–π∗ transitions. Finally, nearly mirror-image CPL spectra were recorded in degassed CH2Cl2 solutions at rt, with glum values of +8.6 × 10−3 at ∼450 nm for (P)-3c and +3.4 × 10−3 at ∼630 nm for (P,ARe,ARe)-10-1. The latter value is similar to the one of complex 7b2 (see Table 1). It is worth mentioning that complex 10-1 displayed a CPL sign which was opposite to that of the lowest-energy ECD band (gabs = −3.4 × 10−3 for (P,ARe,ARe)-10-1), suggesting that absorption and emission involve different electronic states and/or the transition is not Franck–Condon-allowed [25].

(a) Experimental ECD spectra of (P)- and (M)-3c and (P)- and (M)-10-1 in CH2Cl2 at rt. (b) Simulated ECD spectra of (P)-3c, (P,ARe,ARe)-10-1, and (P,ARe,CRe)-10-2 with selected calculated excitation energies and rotatory strengths indicated as “stick” spectra. (c) Isosurfaces of selected molecular orbitals for 3c, 10-1, and 10-2. Adapted with permission from Ref. [17].

3.3. Monometallic helicene–DPPZ–Re(I) complexes

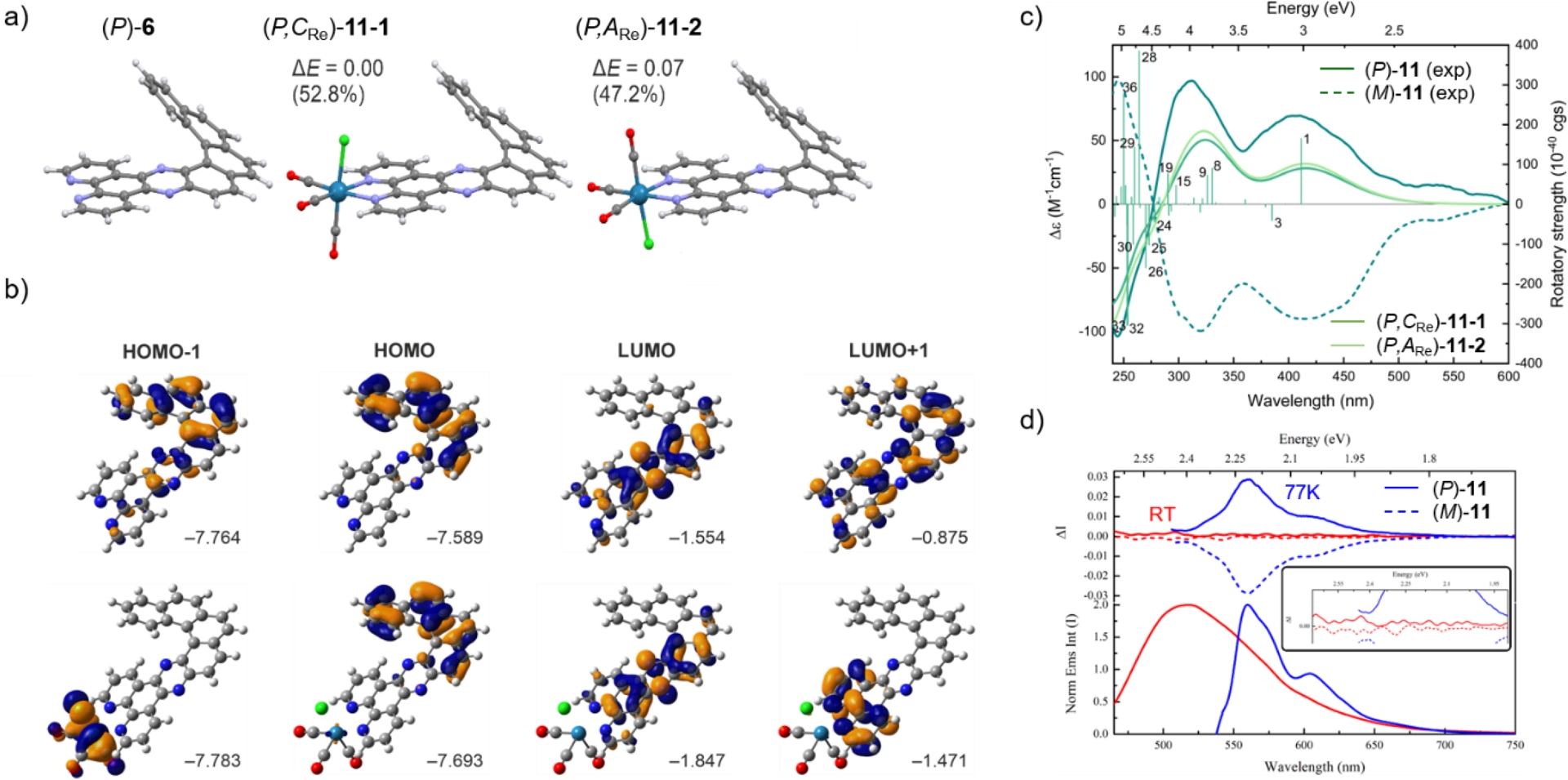

Coordination of Re(I) to helical DPPZ-type ligand 6, using Re(CO)5Cl in refluxing toluene, yielded complex 11. Contrary to ligand 6, it was possible to obtain enantiomerically enriched samples of 11 on an analytical scale using the chiral HPLC separation technique [20]. The (P) and (M) helical configurations were confirmed by (TD)DFT calculations. However, these systems may exist in two octahedral diastereomeric forms differing in rhenium-centered chirality ((P,CRe)-11-1 and (P,ARe)-11-2 and their mirror images), but they could not be clearly distinguished in this particular case. This outcome suggested either a weak differentiation between both diastereomers, a potential dynamic equilibrium in solution, or a preferential formation of one stereoisomer under the synthetic conditions, as already seen in the complexes described above. Complex 11 exhibited very similar UV–Vis absorption in the higher-energy region as for the ligand (Figure 3 and Table 1) but with an additional tail of absorption going down to 575 nm due to the presence of the rhenium atom. TDDFT calculations and MO analysis of 6 highlighted the presence of strong charge-transfer transitions ([4]helicene→pyrazino-phenanthroline) in addition to the classical π–π∗ transitions (Figure 3b), while for 11 they revealed similar electronic characteristics corresponding to almost pure HOMO→LUMO ILCT transition with some helicene-centered π–π∗ signature but with additional Metal-to-Ligand CT (MLCT) component due to the involvement of the metal orbital. The emission spectra of 11 recorded in CH2Cl2 at rt and in 2-MeTHF at 77 K (Figure 3d) were nevertheless found to be mainly influenced by the ligand scaffold with rather minimal impact of the metal center on the photophysical properties but with a quantum yield (Φ = 2%) which was found one order of magnitude higher than for the previously reported neutral mononuclear rhenium–bipyridine–helicene complexes (0.1–0.3%, see above) although lower than for the charged systems (8.3–16%, see above) and the rhenium–NHC–helicene complexes also described by our group (5–13%) [26, 27]. Similarly to 6, emission decay of 11 was found bi-exponential, with a faster lifetime component at 1.2 ns (87%) and a more extended lifetime component of 7.6 ns (13%). The observed lifetime was much shorter than that reported for rhenium–bipyridine–helicene complexes (25–38 ns) (Table 1) indicating again that the emission predominantly originated from the ligand itself with small contribution of the rhenium. Regarding the chiroptical properties, complex 11 exhibited mirror-image ECD and CPL spectra (Figures 3c, d). In ECD, (P)-11 enantiomer exhibited mainly four bands, a negative one around 240 nm, and three positive ones between 311 and 540 nm. The (P) and (M) assignments were based on theoretical calculations. However, calculations showed similar ECD spectra for (P,CRe)-11-1 and (P,ARe)-11-2 preventing any further assignment about the rhenium stereochemistry. CPL signals of 11 were examined both at rt in CH2Cl2 and at 77 K in 2-MeTHF. At rt, the CPL signal correlated with the ECD signals, and (P)-11 showed a positive CPL signal and a glum value of +2.3 × 10−3 at 507 nm. Notably, the CPL signal was significantly increased at 77 K, with a glum value of +2.9 × 10−2 at 560 nm and displayed a clear vibrational progression. Noteworthy, the glum was found to be stable throughout the band suggesting that the emission at 77 K originated from a single excited state, which was not the case at rt, as also indicated by the presence of bi-exponential decay.

(a) Optimized structures of (P)-6, (P,CRe)-11-1, and (P,ARe)-11-2 with relative electronic energy ΔE values (in kcal/mol) and respective Boltzmann populations at 298 K. (b) FMOs of (P)-6 and (P,CRe)-11 obtained based on LC-PBE0*/def2-TZVP/PCM(CH2Cl2) calculations. Values listed are the corresponding orbital energies (in eV). (c) Experimental ECD spectra of 11 enantiomers in CH2Cl2 at rt, along with the corresponding simulated (TDDFT-LC-PBE0*/def2-TZVP/PCM(CH2Cl2)) spectral envelopes obtained for (P,CRe)-11-1 and (P,ARe)-11-2. Selected numbered excitation energies and the corresponding rotatory strengths obtained for (P,CRe)-11-1 indicated as “stick”. (d) Experimental photoluminescence spectra of 11 in CH2Cl2 at rt and in 2-MeTHF at 77 K. Inset: Enlarged spectra. Adapted with permission from Ref. [20].

4. Conclusion

In this review, we have described helicenic organic bipy- or phen-type fluorophores and their use as efficient N,N ligands for coordination to rhenium(I) heavy transition metal centers. This strategy enabled us to generate enantiopure or enantioenriched fac-ReX(bpy)(CO)3-type complexes for which the structure and stereochemical features were carefully analyzed. Furthermore, this gave access to helically chiral absorbers and phosphorescent derivatives with strong experimental ECD responses, substantial CPL activity, and long-lived emission. Their photophysics and chiroptics were studied in detail by theoretical calculations, allowing characterization of CT/π–π∗ transitions in the ligands, and additional MLCT, XLCT, and ligand-to-ligand CT (LLCT) in the complexes. Further molecular engineering enabled access to optimized chiral phosphorescent compounds. Indeed, going from neutral to charged complexes led to significantly improved photophysical characteristics, especially improved quantum yields and much longer-lived emission, while lowering the temperature significantly improved the CPL response, with emission dissymmetry factors increasing by one order of magnitude (from ∼10−3 to ∼10−2). Overall, we think that such specific features in these unique helically shaped heavy-metal complexes provide potentially important future applications, notably in the domain of photoactive catalysts such as in the use of rhenium tricarbonyl bipy complexes for CO2-to-CO reduction [28, 29, 30]. This work is currently ongoing in our group.

Acknowledgements

All collaborators and students involved in this work reviewed in this article are warmly thanked for their precious contributions.

Declaration of interests

The authors do not work for, advise, own shares in, or receive funds from any organization that could benefit from this article, and have declared no affiliations other than their research organizations.

Funding

We acknowledge the Ministère de l’Education Nationale, de la Recherche et de la Technologie, the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS), Rennes Métropole and the French National Agency (ANR, LumoMat-E project, 18-EURE-0012). The European Commission Research Executive Agency (Grant Agreement number: 859752 – HEL4CHIROLED – H2020-MSCA-ITN-2019) is thanked for financial support.

CC-BY 4.0

CC-BY 4.0