1 Introduction

Angular momentum, arguably the second most important concept in the understanding of chemistry is often either ignored or treated in such abstract mathematical terms that its true meaning remains obscure. This happens because the angular–momentum relationship, equivalent to the momentum and energy relationships, p = ℏk and E = ℏω, that connect particle and wave properties of quantum–mechanical entities, is routinely overlooked [1]. The Planck–Einstein relationship attributes a well-defined energy to any phenomenon with harmonic time dependence of periodicity τ, where ω = 2π/τ. The De Broglie relationship likewise associates a well-defined momentum to a phenomenon with harmonic space variation of wavelength λ, where k = 2π/λ.

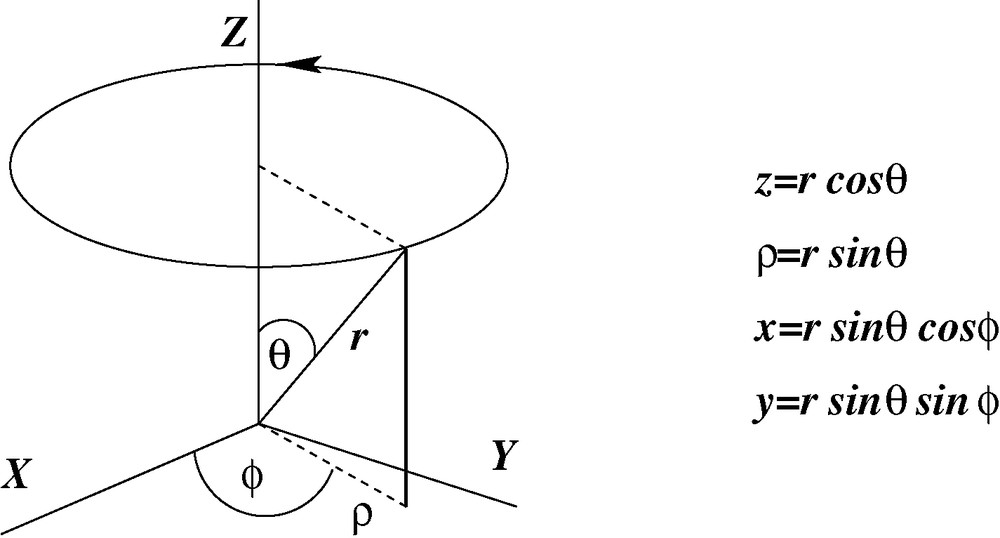

It was suggested by Lévy-Leblond [1] that a well-defined component of angular momentum should accompany a phenomenon of periodicity α around a rotation axis along z, according to a comparable relationship(1)

Quantum–mechanical particle–wave relationships

| Invariance | Period | Pulsation | Dynamic | Quantum condition |

| Temporal | τ | ω = 2π/τ | E Energy | E = ħω Planck–Einstein |

| Translation | λ | k = 2π/λ | p Momentum | p = ħk De Broglie |

| Rotation | α | m = 2π/α | Lz Angular momentum | Lz = ħm Lévy-Leblond |

Mathematically m derives as an integer from the requirement that the angular wave stays in phase with itself, i.e.

Now consider the components Lx, Ly and Lz of the angular momentum L along three orthogonal axes. For them to simultaneously take on unique and well-defined integer values mx, my and mz, the system should be in a state of rotational harmonicity around the three axes. This condition is impossible when dealing with traveling waves. Since stationary waves result from the superposition of two oppositely traveling waves, at least two quantum numbers ± m are required for each component of angular momentum.

Since the possible numerical values of the angular momentum components are integers it appears reasonable that the modulus L, which classically is the maximum possible for any of the components, should obey a rule of the same form, i.e. L = lℏ, l integer. This rule however, does not hold for quantum systems. Since

It has been shown [2] that the spherical shape of atoms is caused by the quenching of orbital angular momentum that, in turn gives rise to the mysterious empirical rules of Hund. By the reverse argument, canonical description of a molecule in terms of a minimum energy function, such as the standard quantum–mechanical molecular Hamiltonian that neglects angular momentum, must fail to generate molecular shape without further assumption. It will be futile to look for molecular shape as an emergent property at this level, since energy is a scalar quantity. Three-dimensional shape can only emerge as a function of some three-dimensional vector quantity.

2 Angular momentum

The components of angular momentum of an electron along a space direction (z say) in a central field, for instance a hydrogenic atom, are defined by the spherical harmonics(2)

A stationary state at the energy level E is defined by the wave function:(4)

Rotating wave front and possible particle orbit for non-zero orbital angular momentum along z.

90° rotation of the coordinate axes about y.

Once the special direction has been fixed, the two remaining eigenfunctions always constitute a complex pair with rotational symmetry in the xy-plane. A geometrical representation related to such functions is shown in Fig. 3.

Associated Legendre functions , , plotted as polar diagrams.

The familiar drawings of a set of three orthogonal px, py and pz orbitals to be found in many chemistry textbooks include the linear combinations that redefine the special z-direction along either x or y. The three real functions as a set, therefore has no physical meaning. Conventional hybridization schemes, invoked to rationalize the formation of multiple bonds, are likewise mathematical impossibilities. The generally accepted explanation of the rotational rigidity of double bonds then also has no physical basis.

Whenever an absolute direction can be defined, for instance in a molecule, the conservation of angular momentum as a manifestation of the rotational symmetry of space no longer holds. In practice this means that for any atom in an environment of less than spherical symmetry, an absolute direction exists, fixing the z-direction. In any degenerate set of states only one can be specified in real form; the others cannot be located more closely than to regions of rotational symmetry around the z-axis.

The wave function of an electron in an s state (ml = 0) is real, which means that it has zero angular momentum and zero kinetic energy. Non-zero ml implies circulating charge and non-zero kinetic energy. Since moving charges must by definition be less effective in chemical binding, it is logical that residual orbital angular momentum should tend to become quenched during the formation of chemical bonds.

It was shown before [2] that the condition to ensure the quenching of orbital angular momentum along z, during bond formation, correctly predicts the known structures of simple molecules, such as methane, ethylene, benzene, ammonia and others, as well as the occurrence of barriers to rotation and optical activity. However, adherence [2] to the traditional stipulation of hybridized electronic configurations introduced an unnecessary complication. Some of these structures and effects are now reexamined by consideration of no more than a special direction that exists in non-spherical molecular fragments.

3 Barrier to rotation

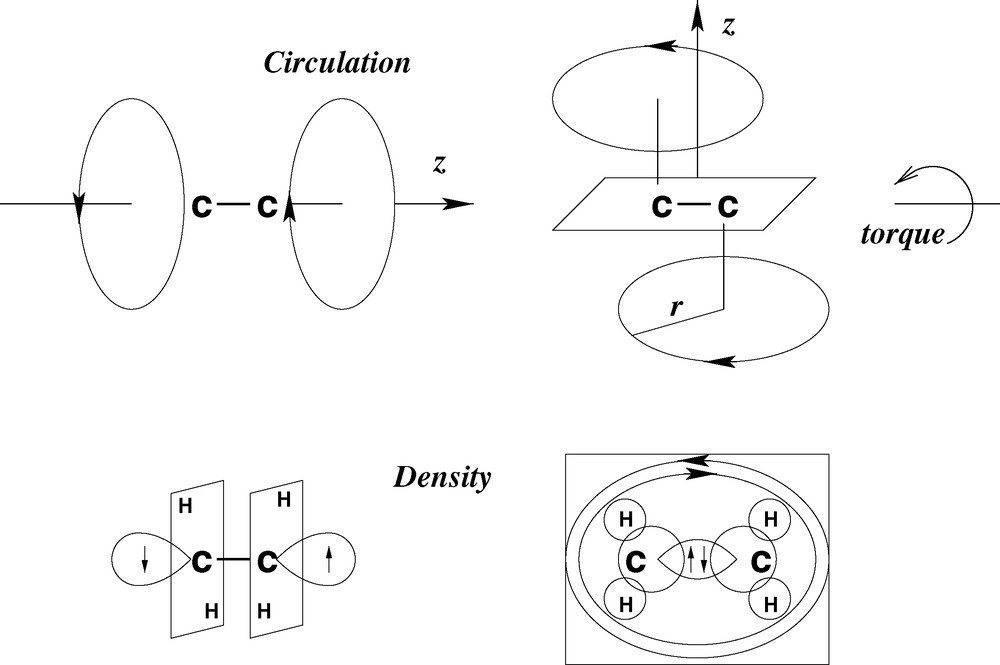

The simplest molecule to exhibit an electronic (non-steric) barrier to rotation is ethylene C2H4. If this molecule is assumed to contain a CC linkage, a special direction may occur in one of two possible ways

Two possible modes of quenching orbital angular momentum in the ethylene molecule. Only the second possibility leads to a planar molecule with a barrier to rotation and fixed positions for the hydrogen atoms.

The generation of angular momentum constitutes a barrier to rotation. In order to torque a centrosymmetric system into a state with non-vanishing angular momentum it is necessary to provide the kinetic energy required to initiate charge circulation. It follows that neither barriers to rotation nor the strengths of double bonds depend on the overlap of π-orbitals. The more logical conclusion is that barriers to rotation occur whenever an applied torque changes the angular momentum.

Although the electron distribution predicted by the angular–momentum model is essentially the same as that obtained in terms of the conventional scheme of sp2 hybridization, the interpretation is exactly the opposite. The barrier to rotation is here ascribed to the pxy quenching of angular momentum while the conventional scheme involves the overlap of pz orbitals.

To calculate the energy barrier to rotation it is noted [3] that the kinetic energy of a rotating charge at a distance r, is(8)

All of the information that was used in the argument to derive the D2h arrangement of nuclei in ethylene is contained in the molecular wave function and could have been identified directly had it been possible to solve the molecular wave equation. It may therefore be correct to argue [5,6] that the ab initio methods of quantum chemistry can never produce molecular conformation, but not that the concept of molecular shape lies outside the realm of quantum theory. The crucial structure generating information carried by orbital angular momentum must however, be taken into account. Any quantitative scheme that incorporates, not only the molecular Hamiltonian, but also the complex phase of the wave function, must produce a framework for the definition of three-dimensional molecular shape. The basis sets of ab initio theory, invariably constructed as products of radial wave functions and real spherical harmonics [7], take account of orbital shape, but not of angular momentum.

4 Optical activity

Optical activity in solution, unlike the same effect in crystals, is an isotropic effect. This interaction between a polarized photon and a molecule therefore implicates a chiral factor that is independent of direction, such as the molecular wave function, and in particular, its complex phase. It is a non-classical factor and hence cannot be attributed directly to a classical three-dimensional structure. In a crystal where optical activity arises from three-dimensional periodicity the vibration ellipsoid has a fixed orientation in the crystal and optical effects are anisotropic. By contrast the high symmetry of molecular eigenstates seems to preclude optical activity. As stated by Woolley [8]:

optical activity has to be understood in a macroscopic context as a loss of inversion symmetry of the whole material medium, and that chirality is not a property that can be related to isolated molecules.

Although the molecular Hamiltonian is by definition spherically symmetrical it however, has chiral solutions (molecular eigenstates) for instance, whenever a molecular magnetic quantum number Ml ≠ 0. The implied magnetic moment causes rotation of the magnetic vector of a field of polarized radiation and, linked to an electric displacement, a helical displacement of charge. The handedness and pitch of the helix are observed as optical activity [9]. In an oscillating magnetic field B associated with electromagnetic radiation the magnetic interaction energy –μ·B leads to transition, with matrix element

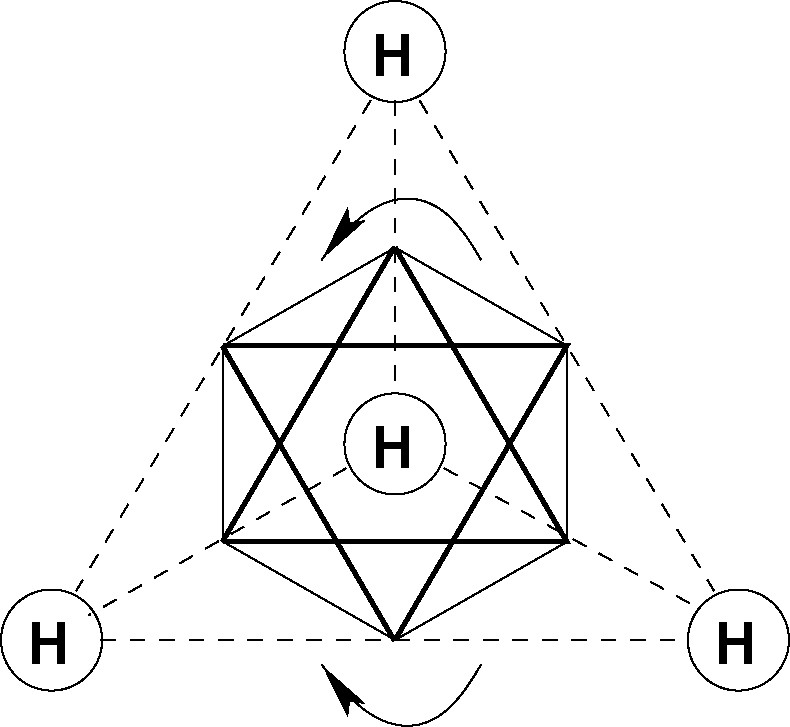

The implied relationship between orbital angular momentum and molecular chirality is conveniently introduced by reference to the structure of methane. The C valence shell of methane consists of two p and six s electrons. To derive a molecular shape it is only necessary to accept that the four hydrogen atoms are equivalent by molecular symmetry. Any of the four HC directions may then be defined to coincide with the z-axis of the molecule. The two angular momentum vectors (l = 1) cannot quench along this axis since that would violate the equivalence assumption. The only alternative is circulation in two planes (ml = ±1) perpendicular to z. This description must be valid from the perspective of any of the four hydrogen atoms. Rotation of the two boldly drawn triangles in Fig. 5 represents the circulation of charge if the z-axis is selected to lie perpendicular to the plane of the paper. Charge accumulation is predicted to occur at the points of intersection of the eight equivalent planes, which together define a regular octahedron, centered at the position of the carbon atom. This condition, as shown in Fig. 5, is satisfied only if the p-density is localized on the six equivalent sites between pairs of hydrogen atoms.

Electronic structure of methane showing charge circulation around the vertical z-axis.

The electron density distribution in the predicted non-classical structure is radically different from that of the geometrically equivalent classical structure and the tetrahedral symmetry occurs for completely different reasons. The structure derived here is stabilized by the anti-parallel alignment of the two angular momentum vectors (along + z and –z) that describe the charges circulating clockwise and anticlockwise, respectively. The balance is exactly symmetrical in point group only if all the ligands around the central atom are equivalent.

Suppose one of the ligands (along z) is replaced by a different atom. The molecular geometry reduces to C3v:3m. The absolute magnitude of the vectors may change, but they stay in balance by symmetry. Replacing a second H atom (at the top of the diagram, say) by yet another ligand, further reduces the symmetry to Cs:m, with a vertical mirror plane that contains the two unique ligand atoms. This modification may well change the direction of the vectors, but the mirror symmetry () between them remains. The vectors become disaligned only when this last element of mirror symmetry disappears and the molecular symmetry reduces to C1:1.

At this stage, with four distinct ligands, angular momentum is no longer quenched (Lz ≠ 0), the molecular quantum number Ml is non-zero and polarized photons interact with the resulting magnetic moment. The plane of polarization is affected differently by enantiomers with respective positive and negative values of Ml. Two enantiomers have identical molecular Hamiltonians and energies – they only differ in angular momentum eigenstates. Decoupling of angular momentum vectors happens whenever a chiral center, here defined in terms of four dissimilar substituents in tetrahedral relationship, occurs in a molecule.

As pointed out before [2] experimental testing of these ideas could be done by the study of paramagnetic susceptibilities of chiral material. It is commonly assumed [10] that orbital angular momentum is completely quenched and that paramagnetism is entirely due to spin. It is not uncommon however, to find that incompletely quenched angular momentum is invoked to explain experimental deviations from spin only values. It is inferred that standard instrumentation is sufficiently sensitive to register the magnetic moments here predicted to be associated with chirality.

4.1 Symmetry of optical rotation

A more fundamental look [11] at both angular momentum and optical activity supports the conclusions drawn here. Angular momentum (L = r × p) is an axial or pseudo vector. A pseudoscalar is generated by taking the scalar product of a polar vector and an axial vector. Optical rotation is characterized by such a property viz. the optical rotation angle.

Under space inversion, an isotropic collection of chiral molecules is re placed by a collection of the enantiomeric molecules. Equal but opposite optical rotation angles will be measured before and after the inversion. The observable is said to have odd parity and since it is invariant with respect to any proper rotation, is a pseudoscalar. Under time reversal an isotropic collection of chiral molecules is unchanged, so the optical rotation observable is a time-even pseudoscalar. The interaction between a polarized photon (polar vector) and residual orbital angular momentum (axial vector) is described by their scalar product, L · ν that generates a pseudoscalar, the optical rotation angle.

There is another type of optical activity known as the Faraday effect. In this case the optical rotation is induced in any crystal, fluid or collection of achiral molecules in the direction of an applied static uniform magnetic field parallel to the light beam. The sense of rotation is reversed on reversing the direction of either the light beam or the magnetic field. It has been realized all along that Faraday optical rotation does not arise from chirality and must be of different symmetry. Under space inversion the molecules and magnetic field direction are unchanged, so the same magnetic optical rotation will be observed. Under time reversal, although the collection of molecules remains unchanged, the relative directions of the magnetic field and the light beam are reversed and the rotation changes sign. These conditions define the magnetic optical rotation observable as a time-odd axial vector.

The symmetry difference between natural and magnetic optical rotation has been interpreted [12] as being generated by time-even odd parity and time-odd even parity tensors, respectively. The former is associated with spatial chirality and the latter with a lack of time-reversal invariance, or temporal chirality in the presence of a magnetic field. The molecular interpretation is straightforward: both spatial and temporal chirality (i.e. the magnetic field) produce non-vanishing orbital angular momentum that interacts with polarized photons.