1. Introduction

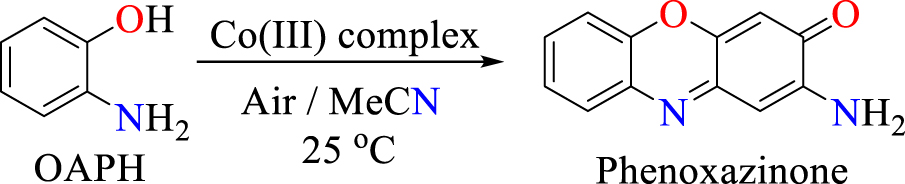

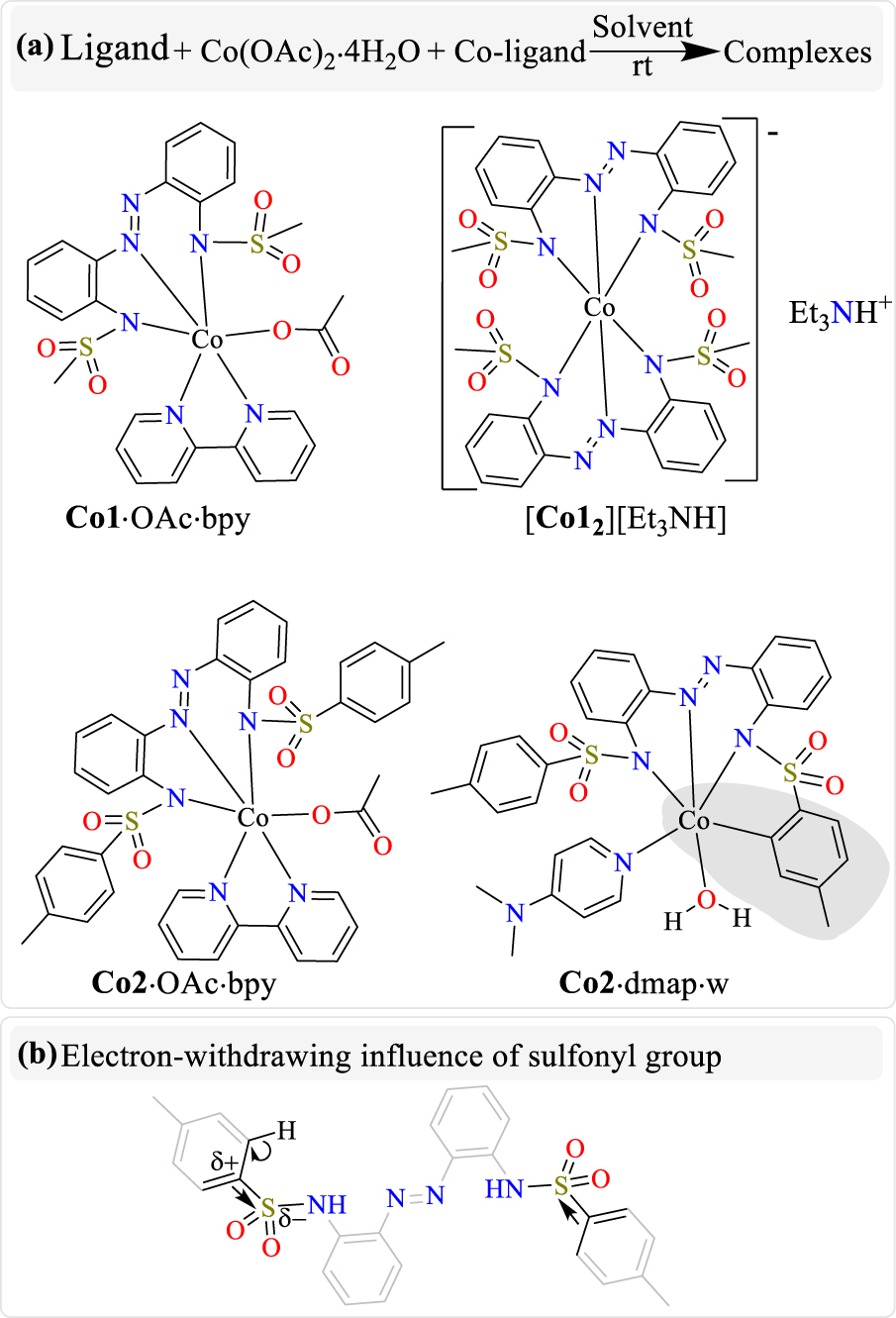

The multi-copper metalloenzyme called phenoxazinone synthase is naturally found in Streptomyces antibioticus [1, 2]. This metalloenzyme catalyses the oxidative coupling of 2-aminophenol (or o-aminophenol) derivatives [3, 4, 5], which leads to biomolecular building blocks of medicinally important anticancer and antibiotic macromolecules such as actinomycin-D, pitucamycin, dandamycin, chandrananimycin E, etc. (Scheme 1(a)) [6, 7, 8, 9]. In biological systems, factors like substrate accessibility of the metal binding site, the presence of a secondary coordination sphere, ligand chelation characteristics, non-covalent interactions, hydrophobic/hydrophilic properties and hydrogen bonding have been recognized to influence the mimicking activity of metal complexes in different biochemical processes [10, 11, 12, 13]. Therefore, we assumed that the design of a series of new cobalt(III) coordination materials in systematically varied coordination environments could improve the understanding of how specific coordination environments affect the enzyme mimicking behaviour of synthetic complexes. Such a structure–property correlation study holds the potential of enabling greater yields in the industrial preparation of the beneficial phenoxazinone chromophores.

Sulfonamide-based molecules have been known for several decades, and they occupy a significant place in biomolecular sciences [14, 15, 16] because of their importance in the development of numerous pharmaceuticals [17, 18, 19, 20]. In organic synthesis, the use of sulfonamides as protecting groups and as excellent sources of introducing nitrogenous units into organic compounds is also well documented [21, 22]. However, sulfonamide moieties are much less explored as N-donors in coordination chemistry. A few reports of complexes containing sulfonamide ligands are encountered for applications in magnetism [23, 24], optics [25, 26], catalysis [14, 27, 28] and drug design [29, 30, 31, 32], but complexes of these biologically significant sulfonamide moieties are scarcely reported as functional models for mimicking metalloenzymes in biological systems [33] and so on.

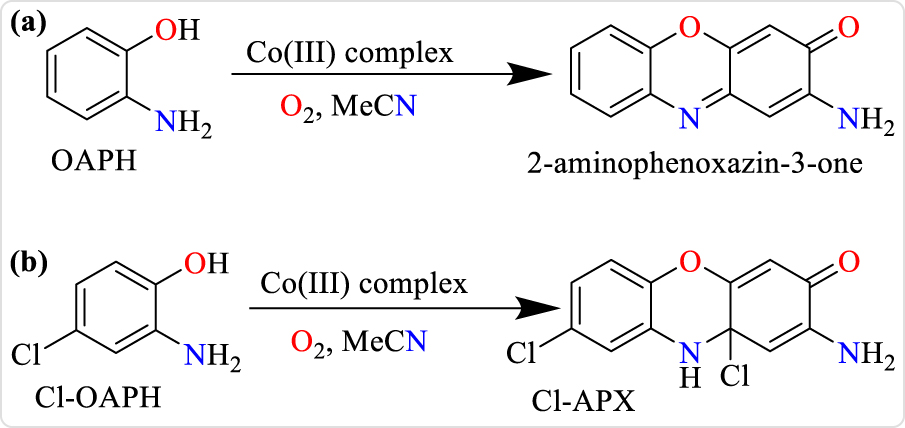

We herein present the results of the syntheses, structural characterization and phenoxazinone synthase mimicking activity of octahedral cobalt(III) complexes bearing sterically varied tridentate diazene–disulfonamide N-donors, which are dianionic, as well as bidentate and monodentate N- and O-donor co-ligands (Scheme 1(b–c)).

(a) Biosynthesis of actinomycin-D catalysed by phenoxazinone synthase, (b) structures of synthesized chelating sulfonamides and (c) the co-ligands incorporated for cobalt(III) complex assembly in this study.

2. Experimental section

2.1. General information

All starting materials for synthesis as well as substrates for the catalytic experiments were obtained commercially as reagent grades and used as supplied without further purification. The o-sulfonamide azo-benzene ligands 1 and 2 have been previously prepared and reported [34]. IR spectra were measured with a Bruker Equinox FT-IR spectrometer equipped with a diamond ATR unit in the range of 4000–600 cm−1. UV–Vis measurement was carried out using Varian Cary 5E UV-VIS-NIR Spectrophotometer. Elemental analyses were carried out on Leco CHNS-932 and El Vario III elemental analysers. Mass spectrometry (MS) spectra were measured with a Bruker MAT SSQ 710 spectrometer. 1H and 13C NMR spectra for characterization of the phenoxazinone product were recorded with a Bruker AVANCE 400 MHz spectrometer using deuterated solvents and TMS as the internal standard.

2.2. Synthesis of cobalt(III) complexes

Co1⋅OAc⋅bpy: Ligand 1 (51 mg, 0.14 mmol), 2,2-bipyridine (22 mg, 0.14 mmol) and cobalt(II) acetate tetrahydrate (0.04 g, 0.14 mmol) reacted in 5 mL ethanol after which a 0.1 mL methanol solution of 0.05 M NaOH was added to the reaction mixture. The solution was kept under slow evaporation. After 2 weeks, Co1⋅OAc⋅bpy was obtained as purple crystals suitable for X-ray measurement. Yield (58 mg, 65%). M.p = 223 °C. Selected IR data (ATR, cm−1): 3060w (Ar–H), 2965w (methyl), 1653m (C=O, acetate), 1606s (C =C, C =N), 1596vs (C =C, C =N), 1507m, 1445vs, 1243s, 1158m, 1119m, 1035m, 959s, 856s, 731s, 623m. MS (EI, Calc. m/z = 640.58): 502 (M – acetate – SO2Me, 5%), 424 (M – bpy & OAc, 50%), 368 (ligand 1), 345, 289, 267, 210, 156 (bpy, 100%), 128. Anal. calc. for C24H22CoN6O4S2: C, 49.57; H, 3.81; N, 14.45; S, 11.03%. Found: C, 49.14; H, 3.83; N, 14.20; S, 10.84%.

[Co12][Et3NH]: Ligand 1 (99 mg, 0.27 mmol) and cobalt(II) acetate tetrahydrate (35 mg, 0.14 mmol) reacted in methanol (2 mL) together with 0.1 mL of triethylamine (Et3N). The solution was allowed to slowly evaporate for 2 weeks, which led to the formation of purple crystals that are suitable for X-ray measurement. Yield (61 mg, 25%). M.p = 301 °C. Selected IR data (ATR, cm−1): 3073m (Ar–H), 2933w (methyl), 1595s (C =C, C =N), 1569s, 1474s, 1330s, 1300vs, 1244s, 1041s, 958vs, 867s, 840vs, 751s, 726vs, 625s. MS (ESI, Calc. m/z = 893.95): 916 (M + Na+, 15%), 758 (M – 2 methyl – Et3NH+, 45%). Anal. calc. for C34H43CoN9O8S4: C, 45.68; H, 4.96; N, 14.10; S, 14.35%. Found: C, 45.54; H, 4.98; N, 13.87; S, 14.13%.

Co2⋅OAc⋅bpy: Ligand 2 (53 mg, 0.10 mmol), 2,2-bipyridine (15 mg, 0.10 mmol) and cobalt(II)acetate tetrahydrate (26 mg, 0.10 mmol) were added together in 3 mL ethanol. 0.1 mL of 0.05 M methanol solution of NaOH was added to the reaction mixture. The solution was slowly evaporated. After 2 weeks, purple crystals of Co2⋅OAc⋅bpy suitable for X-ray measurement were obtained. Yield (63 mg, 79%). M.p = 236 °C. Selected IR data (ATR, cm−1): 3063w (Ar–H), 2978w (methyl), 1606s (C =C, C =N), 1594s (C =C, C =N), 1569m, 1497s, 1451vs, 1357vs, 1295vs, 1247vs, 1159m, 1138vs, 1080vs, 965s, 911s, 836vs, 763vs, 686vs, 624vs. MS (ESI, Calc. m/z + Na+ = 815.76): 815 (M + Na, 45%), 733 (M – acetate, 100%), 659 (M – bpy, 25%), 578 (ligand 2 + Co3+, 20%). Anal. calc. for C36H30CoN6O4S2⋅2H2O: C, 55.07; H, 4.50; N, 10.14; S, 7.74%. Found: C, 54.99; H, 4.37; N, 10.11; S, 7.74%.

Co2⋅dmap⋅w: Ligand 2 (53 mg, 0.10 mmol), 4-dimethylaminopyridine (dmap) (12 mg, 0.10 mmol) and cobalt(II)acetate tetrahydrate (26 mg, 0.10 mmol) reacted in ethanol (3 mL). The solution was slowly evaporated. After a week, yellowish crystals of Co2⋅dmap⋅w suitable for X-ray measurement were filtered, washed with ethanol and air-dried. Yield (51 mg, 71%). M.p = 291 °C. Selected IR data (ATR, cm−1): 3166w (OH, water), 2918w (methyl), 1612vs (C =C, C =N), 1589vs (C =C, C =N), 1533s, 1465s, 1381s, 1280s, 1228vs, 1045s, 1016vs, 942vs, 834m, 781vs, 707s, 661vs, 633s. MS (EI, Calc. m/z = 716.72): 606 (M – tolyl – H2O, 100%), 577 (ligand 2 + Co, 20%), 547 (M – 2Me – dmap – H2O, 80%), 121 (dmap, 20%). Anal. calc. for C33H33CoN6O4S2: C, 55.30; H, 4.64; N, 11.73; S, 8.95%. Found: C, 55.48; H, 4.70; N, 11.47; S, 8.68%.

2.3. Catalytic oxidation of o-aminophenol to 2-aminophenoxazin-3-one

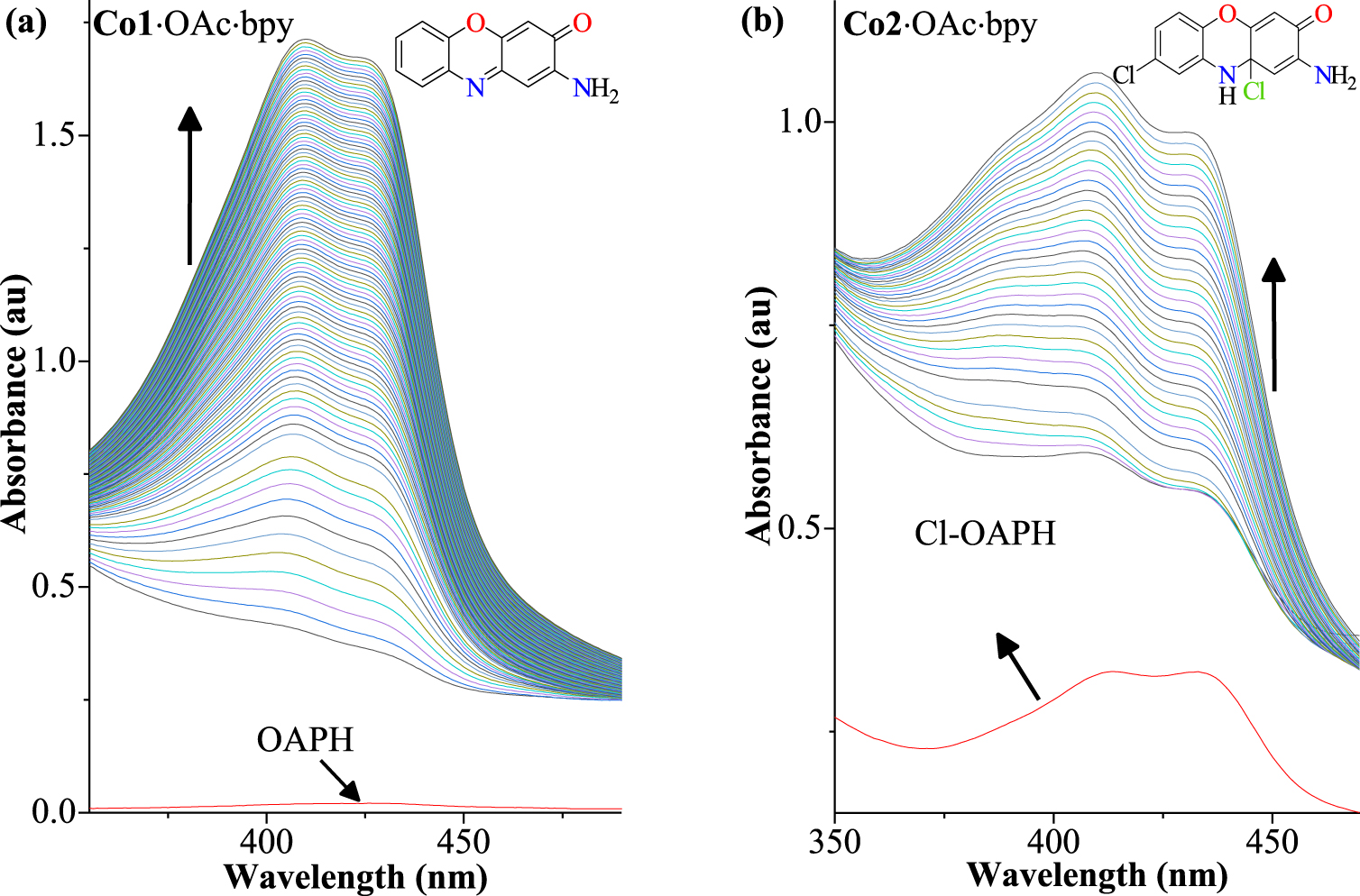

Phenoxazinone-synthase-like activity was studied by deploying 100 equivalents of o-aminophenol (OAPH) relative to concentration of the individual complexes maintained at 5.0 × 10−5 M in acetonitrile and under aerobic conditions at a thermostat temperature of 25 °C. The reaction was followed spectrophotometrically by monitoring the increase in the absorbance of phenoxazinone chromophore as a function of time at 426 nm (ε = 17,278 M−1 cm−1), which is characteristic of 2-aminophenoxazin-3-one in acetonitrile. The 2-aminophenoxazin-3-one molecule was isolated, fully characterized and used for the generation of a calibration curve on the UV–Vis spectrophotometer.

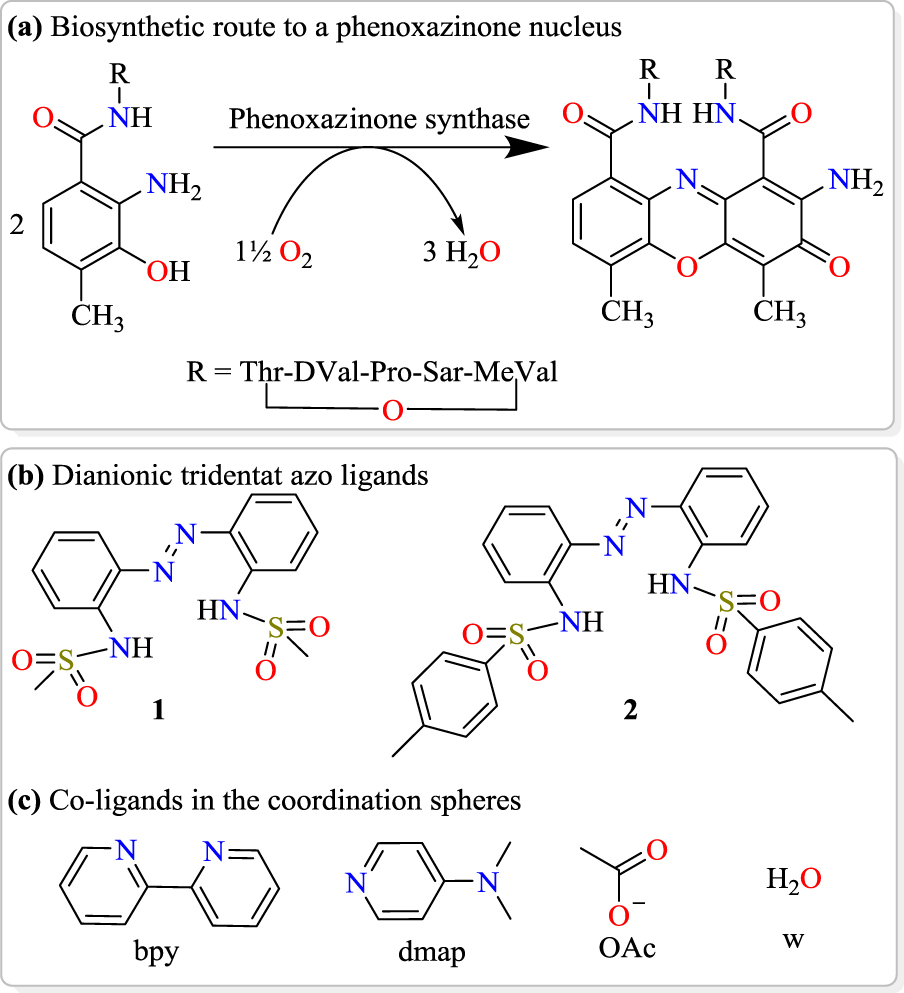

For the catalytic oxidation of 2-amino-4-chlorophenol (Cl-OAPH) to 2-amino-8,10a-dichloro-10,10a-dihydro-3H-phenoxazin-3-one (Cl-APX, Scheme 2), 2.5 × 10−5 M of the complexes was utilized in the presence of 100 equivalents of Cl-OAPH while the increase in absorbance of the phenoxazinone chromophore was monitored at 433 nm. Absorbance spectra of the solutions were measured at time intervals of 30 minutes for all the complexes. The initial rate method was applied to determine the rate of reaction by linear regression from the slope of absorbance values against time.

Aerobic catalytic oxidation of (a) o-aminophenol to 2-aminophenoxazin-3-one and (b) 2-amino-4-chlorophenol (Cl-OAPH) to 2-amino-8,10a-dichloro-10,10a-dihydro-3H-phenoxazin-3-one (Cl-APX).

2.4. Crystal structure determinations

Single crystals of the complexes were obtained by slow evaporation of the solution of the complexes in ethanol or methanol. The intensity data for the compounds were collected on a Nonius KappaCCD diffractometer using graphite-monochromated Mo-Kα radiation. Data were corrected for Lorentz and polarization effects; absorption was taken into account on a semi-empirical basis using multiple scans [35, 36, 37, 38]. The structures were solved by direct methods (SHELXS) and refined by full-matrix least squares techniques against Fo2 (SHELXL-97 and SHELXL-2014) [38, 39]. The hydrogen atoms bonded to the water molecule O5 of Co2⋅dmap⋅w were located by difference Fourier synthesis and refined isotropically. All other hydrogen atoms were included at calculated positions with fixed thermal parameters. All non-hydrogen and non-disordered atoms were refined anisotropically [38]. The crystal of Co2⋅OAc⋅bpy contains large voids, filled with disordered solvent molecules. The size of the voids is 281 Å3/unit cell. Their contribution to the structure factors was secured by back-Fourier transformation using the SQUEEZE routine of the program PLATON [40]. The program XP (SIEMENS Analytical X-ray Instruments, Inc. 1994) was used for structure representations [41]. Crystallographic data as well as structure solution and refinement details are summarized in Table 1.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Syntheses and characterization of cobalt(III) complexes

The octahedral cobalt(III) complexes were generally obtained in good yields by allowing Co(OAc)2 and any of ligands 1 or 2 to interact at room temperature in a given solvent and in the presence of a selected co-ligand additive or base. Analytical characterization data of the complexes agree with the expected values and are further confirmed by X-ray crystal structures.

(a) Synthetic route and compositions of the obtained cobalt(III) complexes. (b) C–H activation of tolyl arm of ligand 2 leading to Co–C cyclometallation.

Although the complexes Co1⋅OAc⋅bpy, Co2⋅OAc⋅bpy and Co2⋅dmap⋅w possess mixed-ligand coordination environments, our deployment of triethylamine as a potential co-ligand preferentially yielded only the bis-ligand complex [Co12][Et3NH], where the triethylamine only functions as a base and acts as a counter cation after becoming protonated (Scheme 3(a)). Furthermore, the tendency of these dianionic ligands to oxidize the cobalt(II) starting material into cobalt(III) products is also worthy of note. The very rare organometallic cyclocobaltated bond in Co2⋅dmap⋅w (shaded regions in Scheme 3(a)), which results from the C–H bond activation of a tolyl ring of ligand 2 (Scheme 3(b)), is also remarkable.

3.2. X-ray structural analyses

Crystal data and refinement details for the X-ray structure determinations

| Compound | Co1⋅OAc⋅bpy | [Co12][Et3NH] | Co2⋅OAc⋅bpy | Co2⋅dmap⋅w |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Formula | C26H25CoN6O6S2 | C36H52CoN9O10S4 | C40H39CoN6O7S2[*] | C33.5H35CoN6O5.5S2 |

| fw (g⋅mol−1) | 640.57 | 958.04 | 838.82[*] | 732.73 |

| °C | −140(2) | −140(2) | −140(2) | −140(2) |

| Crystal system | monoclinic | monoclinic | monoclinic | triclinic |

| Space group | P 21/n | C 2/c | P 21/c | P ı̄ |

| a/ Å | 8.2777(2) | 12.7142(2) | 10.2788(2) | 10.7826(5) |

| b/ Å | 18.0371(5) | 20.2034(4) | 16.6381(4) | 12.1672(6) |

| c/ Å | 18.4623(3) | 17.5336(4) | 24.9023(5) | 14.1688(7) |

| 𝛼/° | 90 | 90 | 90 | 74.698(2) |

| 𝛽/° | 94.003(1) | 107.981(1) | 98.559(1) | 78.483(2) |

| 𝛾/° | 90 | 90 | 90 | 65.782(3) |

| V/Å3 | 2749.80(11) | 4283.88(15) | 4211.35(16) | 1626.32(14) |

| Z | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 |

| 𝜌 (g⋅cm−3) | 1.547 | 1.485 | 1.323[*] | 1.496 |

| 𝜇 (cm−1) | 8.29 | 6.62 | 5.61[*] | 7.1 |

| Measured data | 27341 | 24426 | 42423 | 21261 |

| Data with I > 2σ(I) | 5610 | 4493 | 8547 | 6554 |

| Unique data (Rint) | 6256/0.0349 | 4912/0.0313 | 9615/0.0448 | 7379/0.0458 |

| wR2 (all data, on F2)a) | 0.0767 | 0.0952 | 0.2033 | 0.1112 |

| R1 (I > 2σ(I))a | 0.0363 | 0.0376 | 0.0912 | 0.0427 |

| Sb | 1.046 | 1.025 | 1.235 | 1.062 |

| Res. dens./e⋅Å−3 | 0.676/−0.445 | 0.500/−0.422 | 0.921/−0.573 | 0.673/−0.595 |

| Absorpt method | multi-scan | multi-scan | multi-scan | multi-scan |

| Absorpt corr Tmin∕max | 0.6845/0.7456 | 0.7001/0.7456 | 0.6742/0.7456 | 0.5665/0.7456 |

| CCDC No. | 1903078 | 1903080 | 1903079 | 1903081 |

[*] Derived parameters do not contain the contribution of the disordered solvent.

a Definition of the R indices: R1 = (Σ||Fo|−|Fc||)∕Σ|Fo|;

b

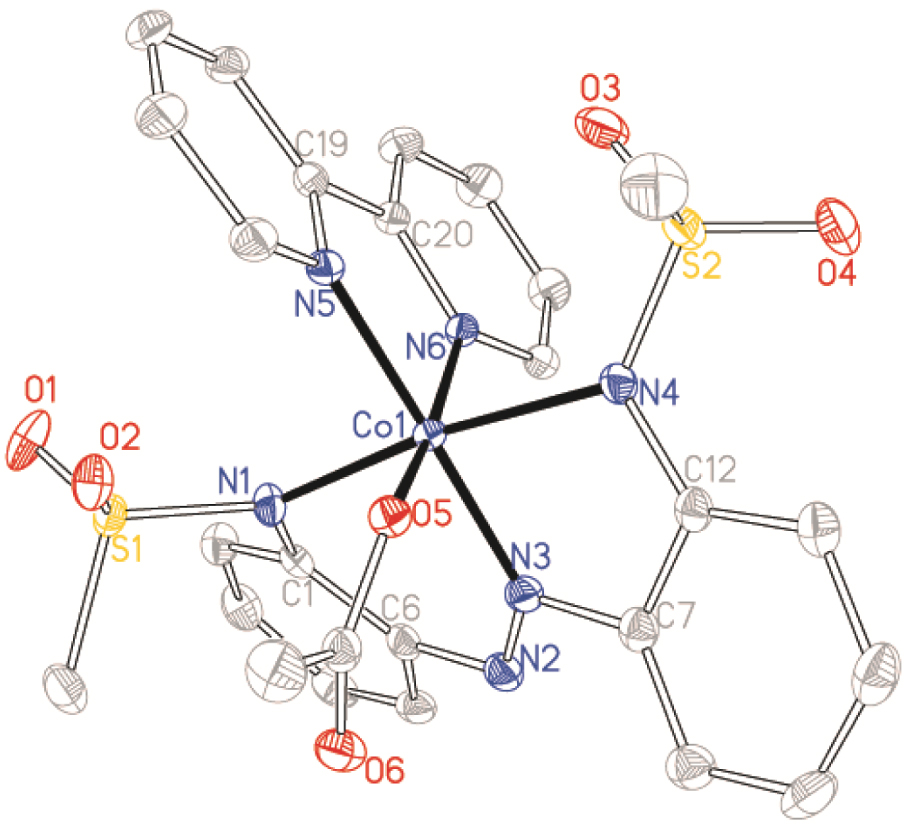

Structure of Co1⋅OAc⋅bpy with ellipsoids drawn at the 50% probability level. Protons have been omitted for clarity.

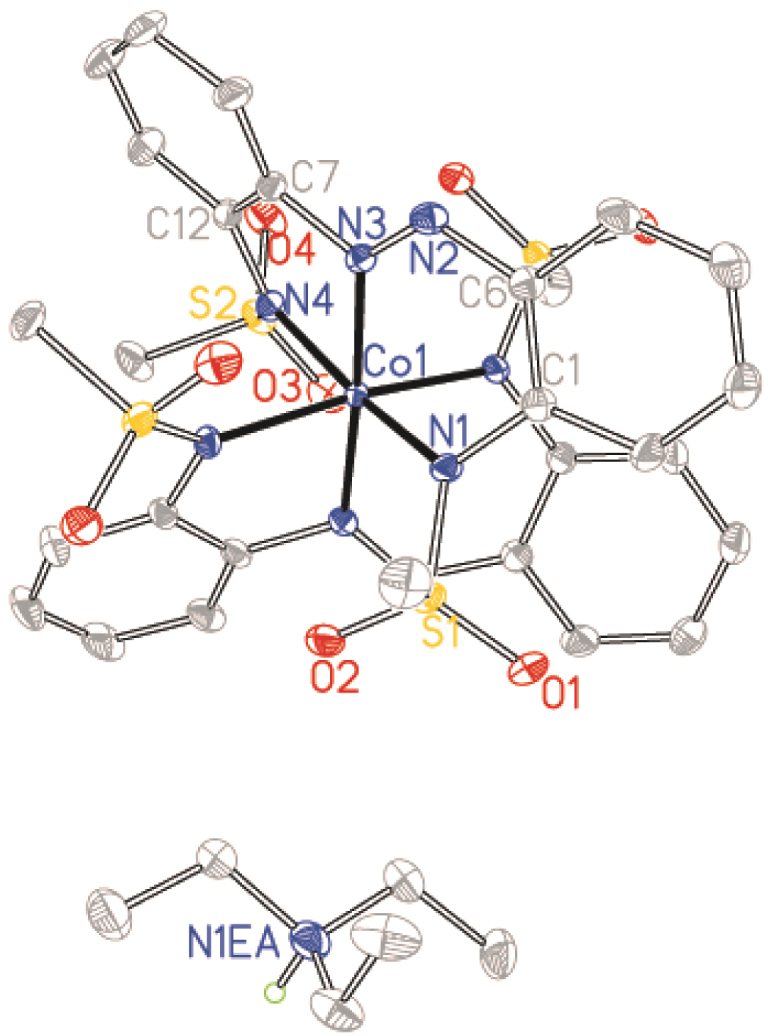

Structure of [Co12][Et3NH] with ellipsoids drawn at the 50% probability level. Protons have been omitted for clarity.

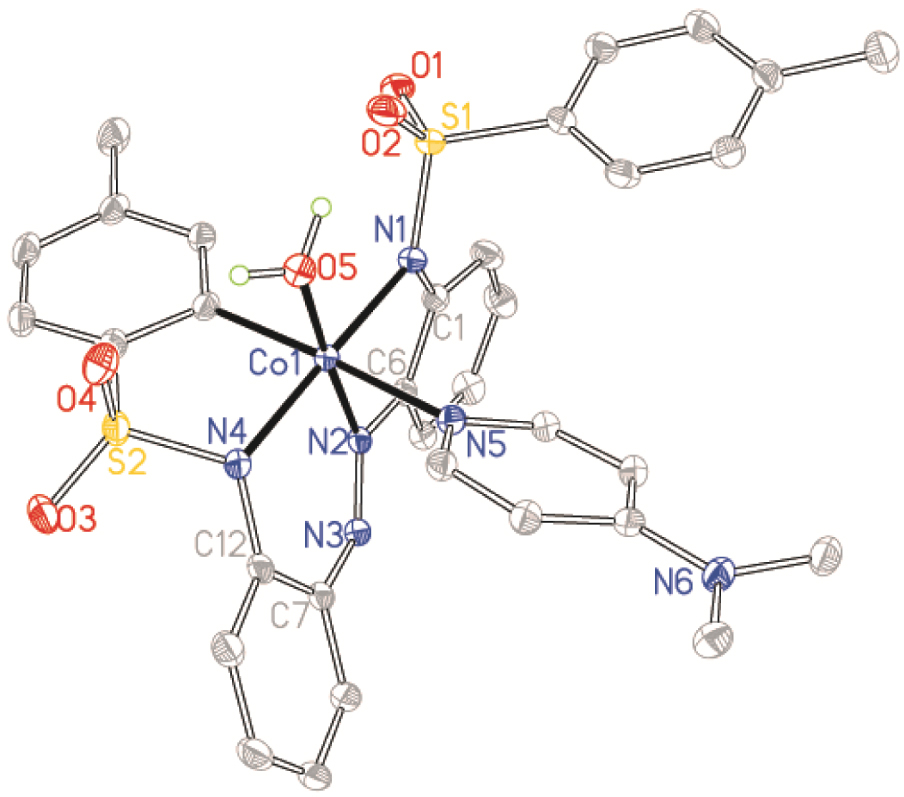

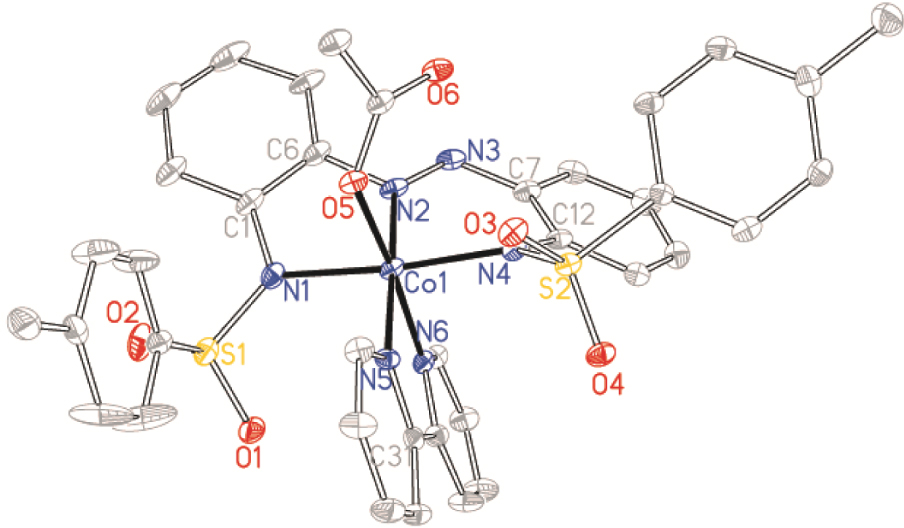

Complexes Co1⋅OAc⋅bpy, [Co12][Et3NH] and Co2⋅OAc⋅bpy crystallized in the monoclinic P21/n, C2/c and P21/c space groups, respectively, while complex Co2⋅dmap⋅w crystallized in the triclinic Pī space group (Table 1). Crystal structures revealed that the synthesized ligands formed tridentate five–six-membered NˆNˆN chelation for complexes Co1⋅OAc⋅bpy, [Co12][Et3NH] and Co2⋅OAc⋅bpy while tetradentate NˆNˆNˆC chelation is obtained for Co2⋅dmap⋅w due to cyclocobaltation (Figures 1–4). Such chelations suggest higher coordination stability from ligands 1 and 2 relative to the other coordinated co-ligands. Bond lengths and angles around the coordination centre of the complexes are within the expected values (see Table S1 of the Supplementary information) [42]. The diversity of coordinative saturation observed among the obtained complexes fulfils our deliberate aim of studying the influence of diverse coordination environments on catalyst efficiencies.

Structure of Co2⋅dmap⋅w with ellipsoids drawn at the 50% probability level. Protons have been omitted for clarity.

Structure of Co2⋅OAc⋅bpy with ellipsoids drawn at the 50% probability level. Protons have been omitted for clarity.

The interesting C–H activation of an ortho-proton on one of the tolyl rings of ligand 2, which leads to cyclometallation in complex Co2⋅dmap⋅w, can be attributed to the strong electron-withdrawing influence of the bonded sulfonamide function (Figure 3). A further factor that possibly supports the cyclometallation is the absence of sufficient anionic donors or insufficient pyridyl co-ligands to satisfy the coordinative saturation required by the Co(III) centre. Even a water molecule had to be taken up as the co-ligand to achieve an octahedral geometry. The only few reports of cyclometallated cobalt complexes have been obtained under classical organometallic inert conditions [43, 44, 45, 46]. To the best of our knowledge, the formation of a cyclocobaltated complex in the presence of moisture and air as in the preparation of Co2⋅dmap⋅w is rare. It is therefore plausible to conclude that incorporation of a sulfonamide substituent could be important for the purpose of facilitating C–H bond activations for organometallic syntheses [47].

Calculated CShM parameters for Co1⋅OAc⋅bpy, [Co12][Et3NH], Co2⋅OAc⋅bpy and Co2⋅dmap⋅w

| Polyhedrona | Co1⋅OAc⋅bpy | [Co12][Et3NH] | Co2⋅OAc⋅bpy | Co2⋅dmap⋅w |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HP-6 (D6h) | 32.295 | 30.155 | 31.750 | 31.862 |

| PPY-6 (C5v) | 25.530 | 26.011 | 26.823 | 27.265 |

| OC-6 (Oh) | 0.748b | 0.673b | 0.598b | 0.348b |

| TPR-6 (D3h) | 11.964 | 13.963 | 13.305 | 14.845 |

| JPPY-6 (C5v) | 29.178 | 29.644 | 30.185 | 30.560 |

aHP-6 (D6h) = hexagon; PPY-6 (C5v) = pentagonal pyramid; OC-6 (Oh) = octahedron; TPR-6 (D3h) = trigonal prism; JPPY-6 (C5v) = Johnson pentagonal pyramid J2.

b Oh has the closest agreement.

| Complex | 103 × V (h−1) |

|---|---|

| No complex | 0.46 |

| Co1⋅OAc⋅bpy | 23.30 |

| [Co12][Et3NH] | 1.15 |

| Co2⋅OAc⋅bpy | 15.48 |

| Co2⋅dmap⋅w | 13.30 |

Reaction conditions: acetonitrile, 1:100 catalyst to OAPH, 25 °C.

In order to properly describe the coordination polyhedra around each cobalt(III) for Co1⋅OAc⋅bpy, [Co12][Et3NH], Co2⋅OAc⋅bpy and Co2⋅dmap⋅w, Continuous Shape Measurement (CShM) calculations were carried out by using the experimentally obtained X-ray structural coordinates of the central cobalt atoms and their directly coordinated donor atoms. The results, which are summarized in Table 2, revealed that the coordination polyhedron around each cobalt(III) centre can best be described as octahedral (Oh) [48, 49, 50]. The distortion path analysis, which provides the percentage deviation from an ideal polyhedron on a scale of 0%–100%, revealed the lowest distortions from an ideal octahedron (i.e. 0.348–0.748%) relative to hexagonal pyramid (30.155–32.295%), pentagonal pyramid (25.530–27.265%), trigonal prism (11.964–19.84%) and Johnson pentagonal pyramid (29.178–30.560%) [51]. The complex Co2⋅dmap⋅w possesses the closest geometry to an octahedron arguably because of the water donor, which allows for the lowest distortive ligand–ligand repulsion and may imply some sort of coordinative stability in Co2⋅damp⋅w. However, the chelate effect in the bis-ligand complex [Co12][Et3NH] would represent a much stronger coordinative stability.

3.3. Phenoxazinone synthase mimicking activity by cobalt complexes

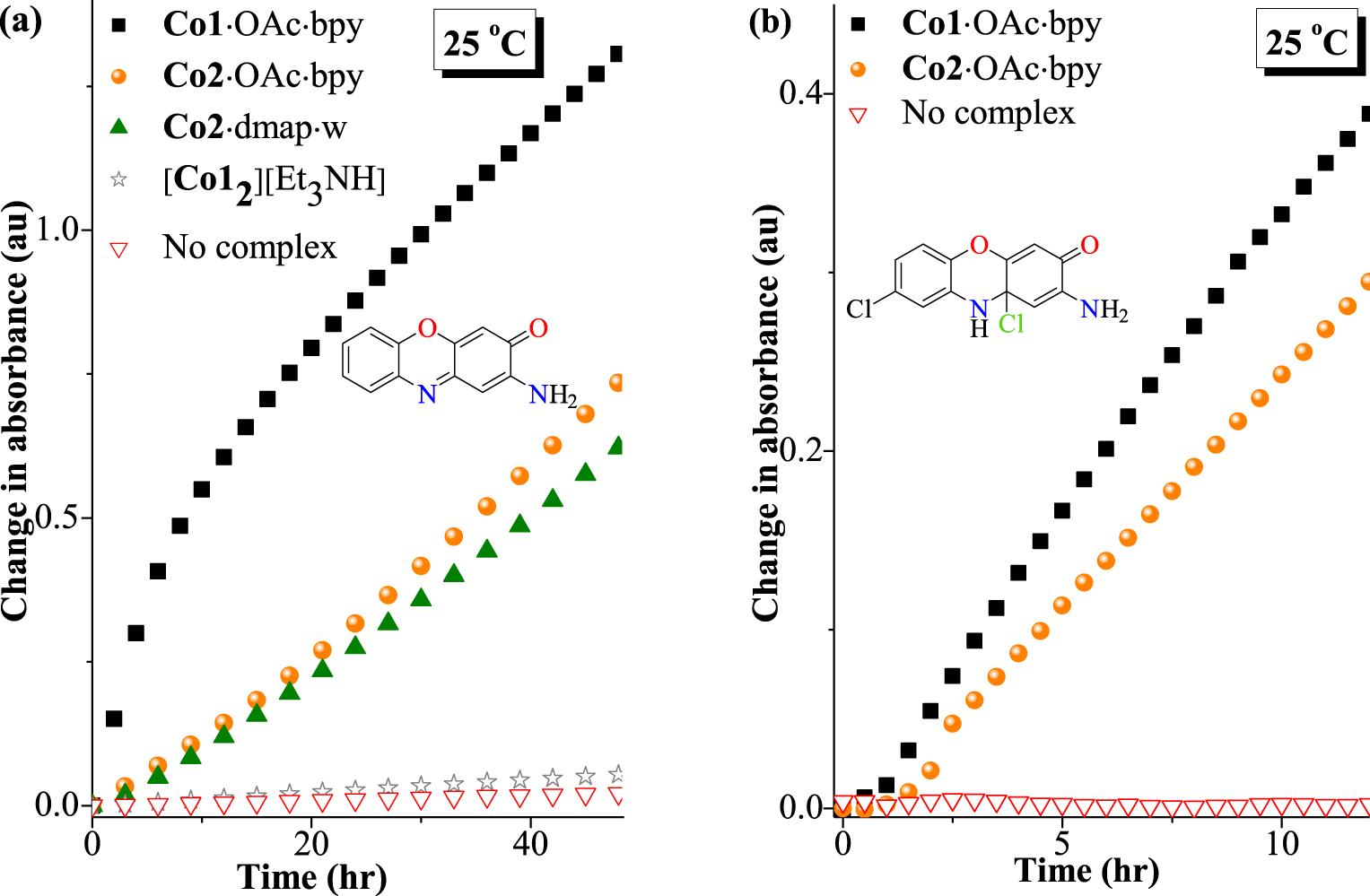

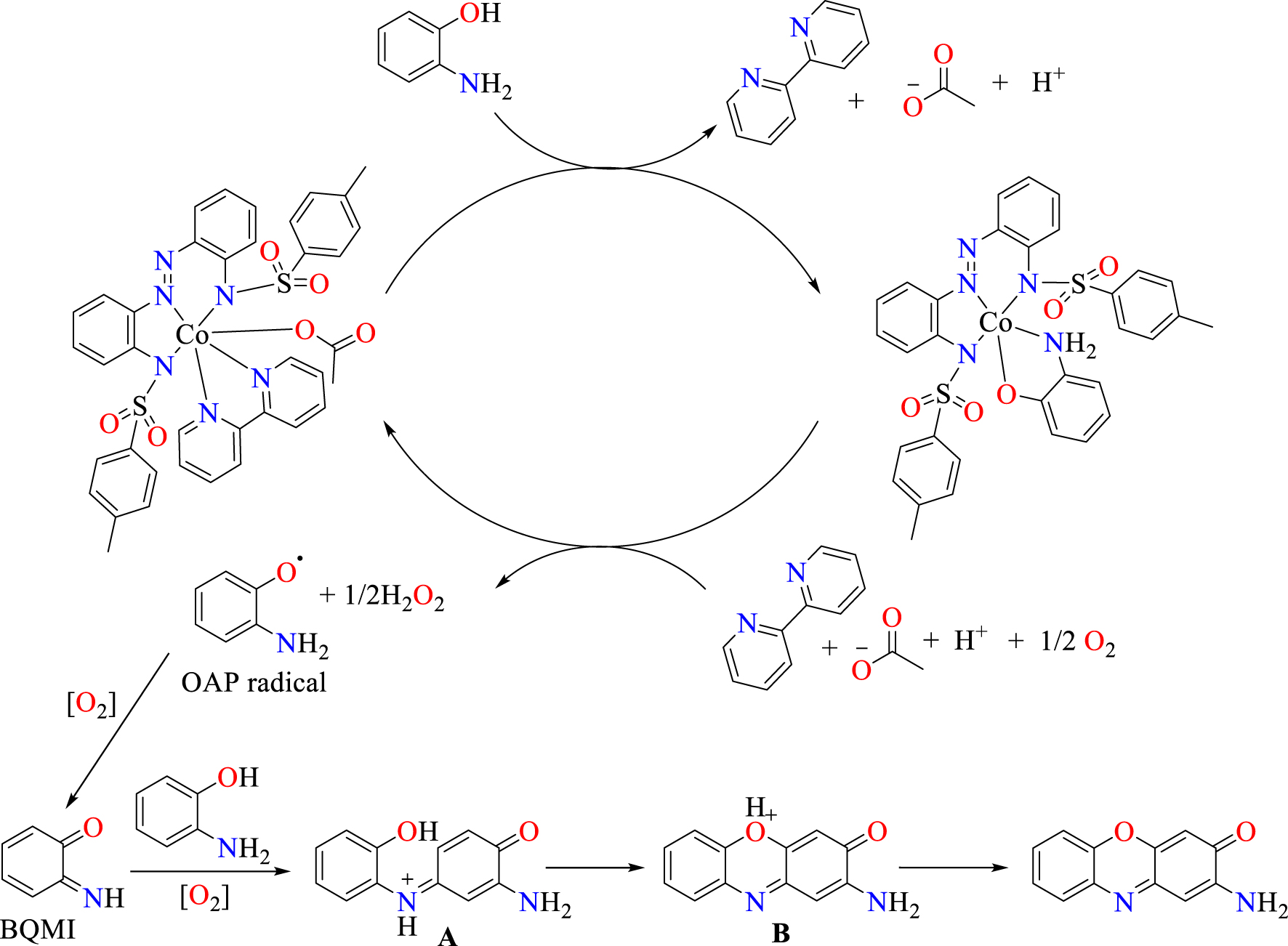

The phenoxazinone synthase mimicking activity of the complexes was tested via oxidative coupling of OAPH or its derivative 2-amino-4-chlorophenol (Cl-OAPH) in the presence of 1 mol% of cobalt(III) and at 25 °C (Scheme 2). The relative catalytic efficiencies for the various complexes were evaluated via absorbance changes (Figure 5(a and b)) as a function of time. Estimates of the initial rate values (V) were determined by linear regression from the slopes of absorbance versus time plots (Figures 6 and 7). These estimates were used for quantitative comparison of catalytic efficiencies among the prepared complexes (Tables 3 and 4).

Insignificant absorbance changes were observed in the absence of the complexes, which proves the importance of the metal ions (Figure 6(a and b) and Table 3). Correlation could be observed between the coordination features and the catalytic outcomes. The bis-ligand complex [Co12][Et3NH], which is the most strongly chelated analogue, has remarkably the least catalytic productivity among the complexes, which could be attributed to the difficulty in releasing the metal centre from the hold of two tridentate chelators. This emphasizes the importance of free coordination sites for the catalysis and that a ligand with strong chelation characteristics as obtainable with porphyrin ligands should be avoided when designing metalloenzyme models.

Stack of UV–Vis spectral scans at regular time intervals showing the increasing phenoxazinone chromophore band for substrates in the presence of 1 mol% of cobalt(III) complexes in acetonitrile solution. (a) Co1⋅OAc⋅bpy + OAPH, 48 hours; (b) Co2⋅OAc⋅bpy + Cl-OAPH, 12 hours.

On the other hand, from a comparison among complexes assembled along with co-ligands [i.e. Co1⋅OAc⋅bpy (23.30 × 10−3 hr−1) > Co2⋅OAc⋅bpy (15.48 × 10−3 hr−1) > Co1⋅dmap⋅w (13.30 × 10−3 hr−1)], the catalyst efficiencies appear to correlate with the percentage extent of deviation from the regular octahedron according to the CShM calculations (i.e. Co1⋅OAc⋅bpy = 0.748% > Co2⋅OAc⋅bpy = 0.598% > Co1⋅dmap⋅w = 0.348%; Table 2). It is therefore plausible to conclude that the general state of steric hindrance in the various coordination polyhedra, which is associated with ligand and co-ligand sizes and the corresponding ligand–ligand steric repulsions, may be accountable for the observed differences in catalytic productivities of the different metal centres. A strained coordination polyhedron hints at the readiness for dissociative events, which is required for creating free substrate-binding sites around the metal ion. Additionally, of the three mixed-ligand complexes, the cyclocobaltated complex Co2⋅dmap⋅w has the tetradentate trianionic complexation feature of ligand 2 as further reason for its poorer catalyst performance.

Complexes Co1⋅OAc⋅bpy and Co2⋅OAc⋅bpy, which possess higher catalytic yields for the coupling of OAPH, are further deployed for the coupling of Cl-OAPH at 25 °C. Their resulting initial rates are 32.06 × 10−3 hr−1 and 26.06 × 10−3 hr−1, respectively, which reveal higher initial rate values relative to the experiments without cobalt(III) complex (Figure 6(b)). A similar coupling reaction for Cl-OAPH in the absence of cobalt(III) also yielded negligible products (see Supplementary information Table S2). Yet it is noteworthy that Co1⋅OAc⋅bpy shows a higher catalytic efficiency than Co2⋅OAc⋅bpy towards the oxidative coupling of Cl-OAPH. It is also worthy of mention that coupling of the chloro-substituted substrate Cl-OAPH is less favoured compared to the non-substituted OAPH, which can be expected on the grounds of steric influence of the chloro-substituent (Figure 6(b) vs. (a)). A proposed scheme of catalytic coupling by complex Co2⋅OAc⋅bpy has been summarized in Scheme 4.

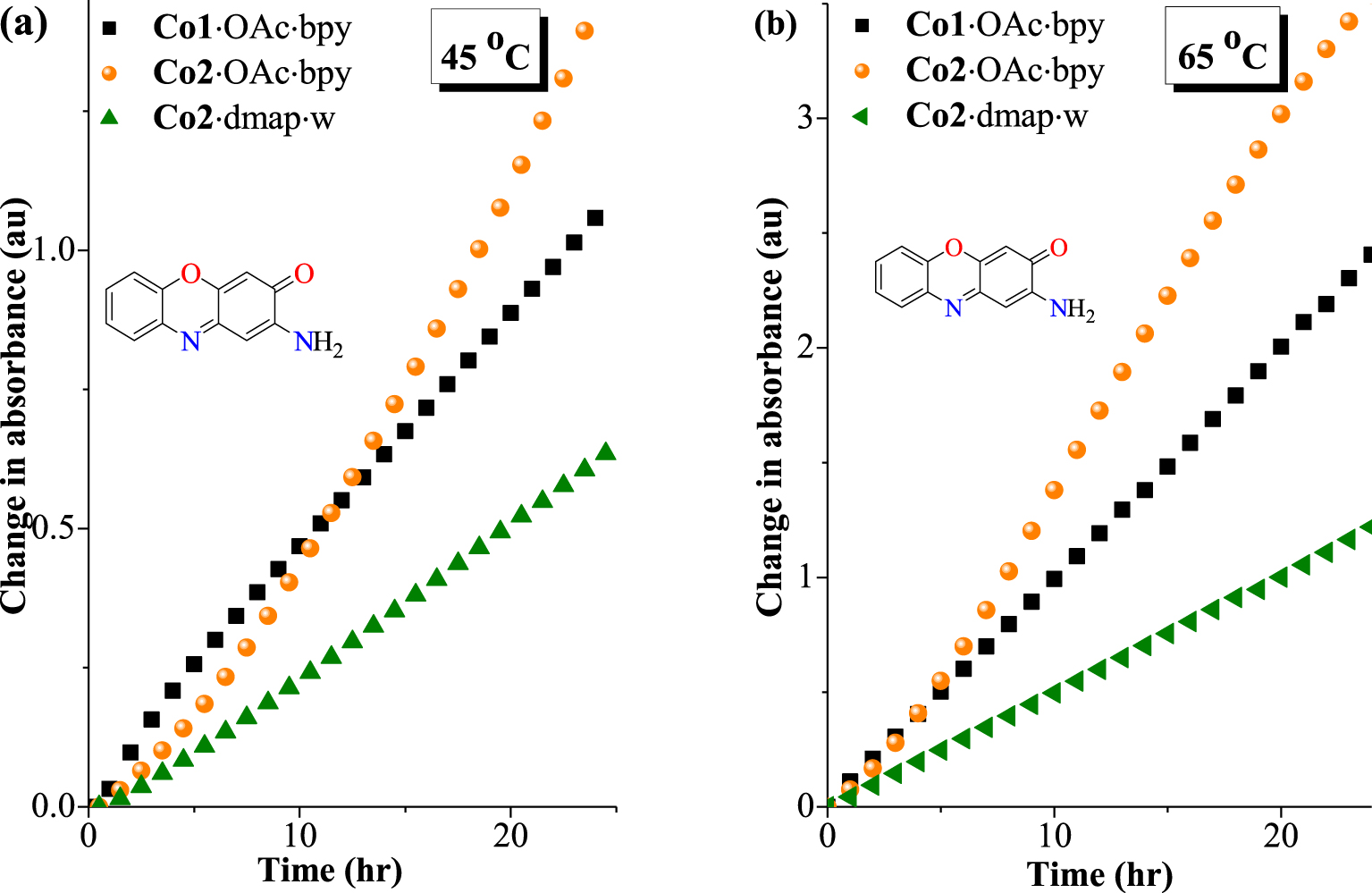

3.4. Temperature variation and phenoxazinone mimicking activities

The effect of temperature variation from 25 °C to 65 °C on the phenoxazinone activity was examined using complexes Co1⋅OAc⋅bpy, Co2⋅OAc⋅bpy and Co2⋅dmap⋅w as catalytic models. The results show a remarkable increase in catalytic activity as the temperature increases (Table 4 and Figure 7). This agrees with the increasing tendency to dissociate co-ligand donors, which then creates vacant coordination sites for substrate binding. Thus, the tendency of the complexes to generate free coordination sites could on one hand depend on the coordinative strain as well as on thermal dissociations on the other hand.

Plot of absorbance vs time for the phenoxazinone synthase mimicking activity of complexes at 25 °C. (a) 1 mol% of complex in oxidative coupling of OAPH (5 × 10−3 M). (b) 1 mol% Co1⋅OAc⋅bpy or Co2⋅OAc⋅bpy in the catalytic oxidation of Cl-OAPH (2.5 × 10−3 M).

Plot of absorbance vs time for the phenoxazinone synthase mimicking activity of complexes at (a) 45 °C and (b) 65 °C (OAPH = 5 × 10−3 M, complex = 5 × 10−5 M).

Proposed mechanism for the aerobic catalytic oxidation of OAPH to 2-aminophenoxazin-3-one by Co2⋅OAc⋅bpy.

Varying temperatures and corresponding 103 × V values for complexes Co1⋅OAc⋅bpy, Co2⋅OAc⋅bpy and Co2⋅damp⋅w

| Temp. (°C) | Co1⋅OAc⋅bpy | Co2⋅OAc⋅bpy | Co2⋅dmap⋅w |

|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | 23.30 | 15.48 | 13.30 |

| 35 | 27.67 | 36.91 | 18.41 |

| 45 | 41.18 | 63.20 | 27.14 |

| 55 | 65.89 | 117.61 | 37.50 |

| 65 | 99.76 | 157.87 | 50.76 |

Reaction conditions: coupling of OAPH (5 × 10−3 M), 1:100 complex to OAPH, 25–65 °C.

A very important observation during the increase in catalysis temperature from 25 °C (Figure 6(a)) through 35 °C, 45 °C (Figure 7(a)) and 55 °C to 65 °C (Figure 7(b)) is the steady improvement in performance for complex Co2⋅OAc⋅bpy. This complex displayed the second best efficiency at 25 °C and thereafter overtakes the originally most active complex Co1⋅OAc⋅bpy from 35 °C (Table 4). The superior activity for Co2⋅OAc⋅bpy at higher temperatures relative to Co1⋅OAc⋅bpy might be attributed to a higher susceptibility to the thermal dissociation of acetate or bipyridine co-ligands in Co2⋅OAc⋅bpy. The bulkiness of the tolyl substituents in Co2⋅OAc⋅bpy appears to be a contributory factor to its thermal susceptibility [52]. In general, the catalysis outcomes suggest that the availability of a vacant binding site during the catalytic process is important.

4. Conclusion

Two well-characterized tridentate NˆNˆN ligands 1 and 2 designed as dianionic disulfonamide–diazo chelators were deployed along with co-ligands such as acetate (OAc), 2,2’-bipyridine (bpy), 4-dimethylaminopyridine (dmap) and/or water (w) to form octahedral cobalt(III) self-assembled complexes from cobalt(II) acetate. These complexes, which were characterized by elemental, spectroscopic and single-crystal structural analyses, were obtained in varying coordination compositions. While Co1⋅OAc⋅bpy, Co2⋅OAc⋅bpy and Co2⋅dmap⋅w were obtained as mixed-ligand complexes, the complex [Co12][Et3NH] assembled as a highly chelated bis-ligand cobaltate(III) anion with a triethylammonium counter cation due to the absence of co-ligands. The sulfonamide group also proved to be useful for enabling C–H bond activation of its substituent aryl rings, which led to cyclocobaltation for the complex Co2⋅dmap⋅w in the presence of insufficient co-ligands. The tendency of the dianionic ligands 1 and 2 to oxidize cobalt(II) during complexation into cobalt(III) is noteworthy. Continuous Shape Measurement calculations based on the single-crystal geometries of atoms within the coordination spheres of these complexes revealed varying degrees of small deviations from a regular octahedral polyhedron (0.348–0.748%).

Trends of the phenoxazinone synthase mimicking activities by these complexes correlated with their relative tendency to dissociatively create a vacant coordination space for substrate–metal site interactions. While the control catalysis experiment in the absence of the complexes and catalysis in the presence of the highly chelated bis-ligand complex [Co12][Et3NH], respectively, produced negligible and very low coupling efficiencies, the mixed-ligand complexes actively acted as coupling catalysts for the substrates. Furthermore, among the mixed-ligand complexes, correlation is also observed between the extent of octahedron distortion as well as the thermal dissociation potentials and the coupling activities, which emphasized the importance of generating vacant binding sites for the substrates on octahedral cobalt(III) centres.

A key result drawn from catalytic trends observed among the complexes in this study is that while coordinative steric strain attributable to ligand sizes and their corresponding ligand–ligand repulsions is the determinant at low temperatures, susceptibility to thermal dissociation of co-ligands is the predominant reason for the catalytic behaviour at higher temperatures and is found capable of reversing the low temperature trends.

Acknowledgements

HOO is grateful to the Government of the Federal Republic of Nigeria for TETfund research grants (TETfund AST&D year 2012 intervention) and to Adeyemi College of Education, Ondo, Nigeria for granting study leave. AOE is thankful to Alexander von Humboldt Foundation for granting post-doctoral scholarship. The financial support by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) is gratefully acknowledged (PL 155/9, PL 155/11, PL 155/12 and PL155/13).

Supplementary data

Supporting information for this article is available on the journal’s website under https://doi.org/10.5802/crchim.15 or from the author. It contains the experimental details and randomization protocols.

Crystallographic data (excluding structure factors) have been deposited with the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre as supplementary publication CCDC-1903078 for Co1⋅OAc⋅bpy, CCDC-1903079 for Co2⋅OAc⋅bpy, CCDC-1903080 for [Co12][Et3NH] and CCDC-1903081 for Co2⋅dmap⋅w. Copies of the data can be obtained free of charge on application to CCDC, 12 Union Road, Cambridge CB2 1EZ, UK [E-mail: deposit@ccdc.cam.ac.uk].

CC-BY 4.0

CC-BY 4.0