1. Introduction

Nuclear facility operations generate significant quantities of aqueous effluents containing transuranic elements. These elements originate from various stages of the nuclear fuel cycle, including ore processing and nuclear fuel production/development. These long-lived radionuclides are of significant international concern because of their dual chemical and radiological toxicity, which can have serious effects on human health and wildlife [1, 2]. To reduce the risk to human health, the United States Environmental Protection Agency has established a maximum contaminant level of 30 μgU⋅L−1 for radionuclides in drinking water, a limit that has been adopted by many countries [3]. The World Health Organization limits the concentration of uranium in drinking water to 15 μgU⋅L−1. In this context, the effective remediation of wastewater contaminated with radioactive uranium has become a critical issue from both social and environmental perspectives [4]. Due to the complexity of chemical and radiochemical composition of radioactive waste, its treatment poses a significant challenge that must be taken very seriously. The removal of radioactive elements in liquid effluents must meet strict requirements regarding the limits of radioactive substances and other contaminants. To meet the standards set by national and international regulations, the waste must be treated to reduce both the volume and concentration of radioactive compounds and other toxic solutes in the effluent [5].

Several processes are available for the removal of uranium from aqueous solutions, including precipitation, membrane separation, electrodeposition, coagulation, reverse osmosis, ultrafiltration, phytoremediation, solvent extraction, and ion exchange [6, 7, 8, 9, 10]. However, most of these techniques have certain drawbacks, such as high operating costs, inadequate metal removal, and the generation of large volumes of sludge [11]. Adsorption using low-cost adsorbents and biosorbents is recognized as an effective and economical method for removing heavy metals at low concentrations. Various materials, such as activated carbon [12, 13], synthetic polymers [14], biomass [15], clay minerals [16], metal oxides [17], and a wide range of inorganic materials, including zeolites, have been developed and used for radionuclide adsorption [18, 19]. Zeolites, as low-cost adsorbents, have attracted considerable interest for the removal of uranium and other trace elements from effluents due to their excellent adsorption capacity, which is attributed to their large specific surface area and developed porosity. Their long lifetime and radiation resistance also provide significant advantages for the treatment of radioactive waste [5]. They have been investigated as cation-exchange adsorbents for heavy metals present in low-activity wastes and, more recently, for the treatment of medium- and high-activity wastes [20]. Many zeolites have been used in the recovery of uranium from liquid radioactive waste, including clinoptilolite, montmorillonite, heulandite, analcime, phillipsite, chabazite, and other minerals, as well as synthetic zeolites such as NaA, NaY, X, 4A, P1 [5], and NKF-6 [7]. Zeolites are a family of aluminosilicates with an open structure with well-distributed micropores. Their general formula can be expressed as follows: Mx/n((SiO2)x(AlO2)y)(H2O)z, where M is an extra-framework cation with a valence of n, which compensates for the negative charges of the framework, enabling zeolites to function as cation exchangers.

The primary objective of this study is twofold: first, to synthesize a large pore ZSM-12 nanomaterial and second, to evaluate its performance as an adsorbent for uranium(VI) from aqueous effluents. In addition, the study investigates sorption isotherm models, kinetics, and various thermodynamic parameters associated with the adsorption process.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Reagents and chemicals

All the chemicals and reagents used in this study were of analytical grade. Uranium nitrate (UO2 (NO3)2⋅6H2O, 99%), nitric acid (HNO3, 63%), aluminum oxide (Al2O3, 98%), arsenazo (III), and tetrapropylammonium bromide (TPABr, 98%) were purchased from Merck. Sodium hydroxide (NaOH, 98%) was sourced from Sigma-Aldrich and Aerosil 200 (SiO2, 100%) was purchased from Degussa. Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (C10H16N2O8, 99%) was provided by PanReac, 4-nitrophenol (C6H5NO3) was obtained from Biochem, and chloroacetic acid (ClCH2COOH, 99%) was purchased from Fluka.

The wastewater used was generated during the processing of uranium ore at the Draria Nuclear Research Center (CRND). Atomic absorption spectroscopy, flame photometry, and ultraviolet–visible (UV–vis) spectroscopy were used to determine the chemical composition of the effluent, with concentrations of U(VI) 151.69 mg⋅L−1; Na, K, and Ca(II) 9.679, 0.752, and 2.708, respectively; Fe(III) 4.502 mg⋅L−1.

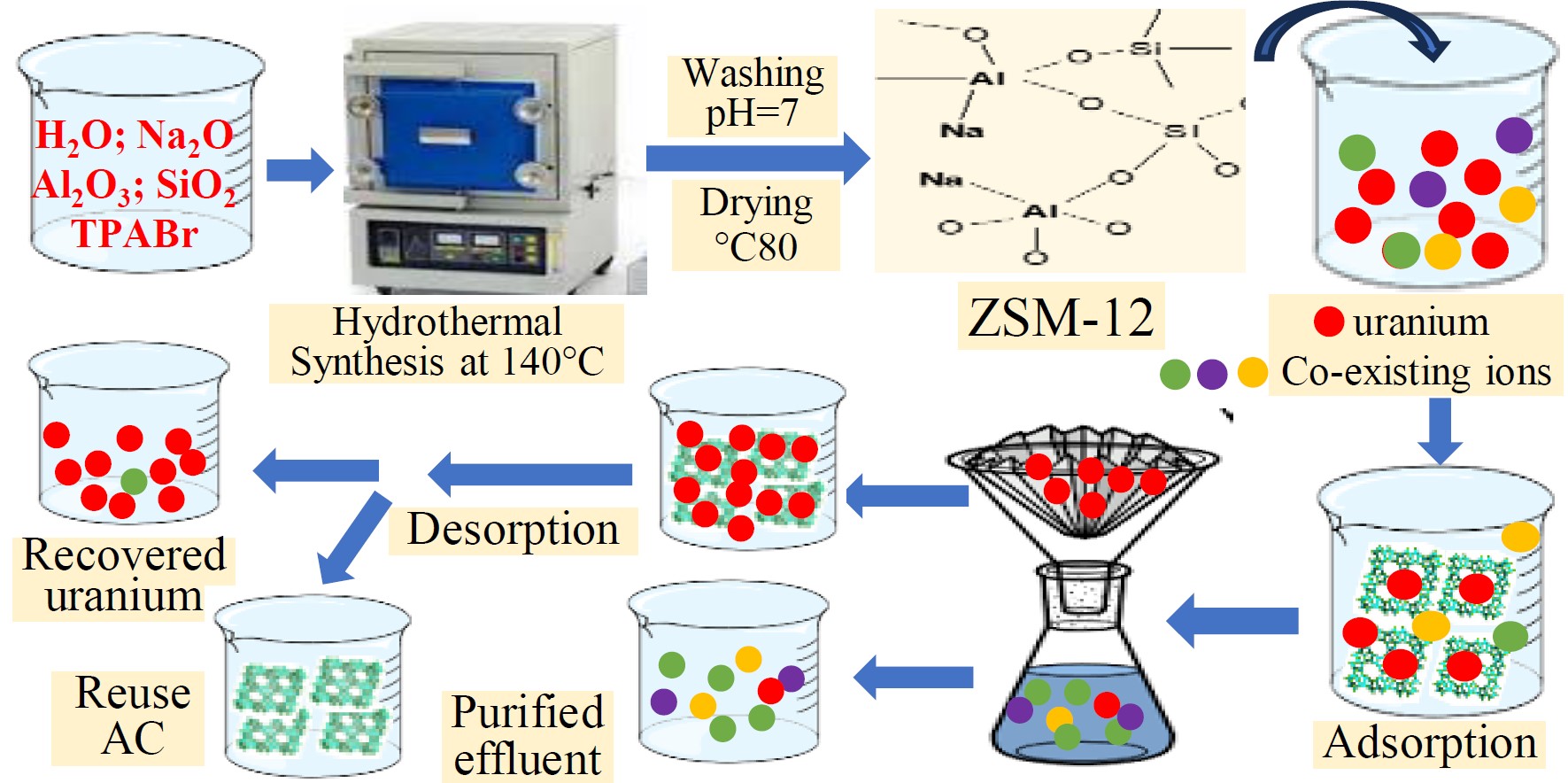

2.2. Synthesis of the adsorbent

The hydrothermal synthesis of ZSM-12 zeolite was carried out in a stainless steel autoclave coated with Teflon. The molar composition of the gel is expressed as follows: 10Na2O:Al2O3:100SiO2:2000H2O:20 TPABr [21]. The gel obtained was stirred for 1 h until homogenization occurred and then placed in an oven and heated to a temperature of 140 °C for 6 days. The autoclave was then cooled under running water. The crystallized product collected after filtration was washed several times with distilled water until it had a pH of 7 and then dried in an oven at 80 °C for 24 h.

2.3. Characterization

The crystallographic structure of the prepared ZSM-12 was analyzed by powder X-ray diffraction (XRD, Bruker AXS D8 Advance). The surface functional groups were identified using Fourier transform infrared (FTIR, UATR, PerkinElmer) spectroscopy. The specific surface area was determined by a N2 adsorption–desorption analyzer (Micromeritics, ASAP 2010). The specific surface area was calculated by the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) method while the pore size distribution and pore volume were calculated by the BJH model.

2.4. Adsorption experiments

A uranium solution with a concentration of 1 g⋅L−1 was prepared through the dissolution of 2.11 g of uranyl nitrate salt UO2 (NO3)26H2O in distilled water. A small amount of concentrated nitric acid (HNO3) was added to prevent hydrolysis. Subsequently, uranium solutions of different concentrations were obtained by diluting the original solution with distilled water.

The U(VI) adsorption experiments were conducted in closed polyethylene bottles of 100 mL in duplicate and the mean values were considered as the final experimental data. In order to determine the optimum parameters of uranium adsorption, the effect of contact time, pH value, initial concentration, temperature, and solid/liquid ratio was investigated. Experiments were conducted with known amounts of ZSM-12 in 20 mL of uranium solutions at a speed of 250 rpm. Once the adsorption equilibrium was reached, the two phases were separated by centrifugation and the filtrates obtained were analyzed by a UV–vis spectrophotometer (Cintra 40 with GBC software) at 652 nm using arsenazo (III) as the complexing agent [22]. The adsorption capacity (Qe, mg⋅g−1) and the adsorption efficiency (%) of uranium(VI) at equilibrium were calculated using the following equations:

| \begin {eqnarray} &\displaystyle Q_{\mathrm {e}}=\frac {(C_{0}-C_{\mathrm {e}})\times V}{m} \label {eqn1}\end {eqnarray} | (1) |

| \begin {eqnarray} &\displaystyle R\ (\%)=\frac {(C_{0}-C_{\mathrm {f}})\times 100}{C_{0}} \label {eqn2} \end {eqnarray} | (2) |

The agreement between the experimental and theoretical adsorbed amounts by the isothermal models was determined by calculating the average percentage error (APE %) according to Equation (3):

| \begin {eqnarray}\label {eqn3} \mathrm {APE}_{\mathrm {kinetic}} (\%)= \frac {\sum | (Q_{t,\exp }-Q_{t,\mathrm {calc}})/Q_{t,\exp }|}{N}\times 100 \end {eqnarray} | (3) |

2.5. Adsorption isotherms

The sorption isotherm reveals the nature of the adsorption, which is directly related to the surface properties of the adsorbent material and its affinity for the adsorbate. It also provides insight into the distribution of adsorbate ions at the solid/liquid interface at equilibrium. Langmuir, Freundlich, and Dubinin–Radushkevich (D–R) models have been tested for the simulation of uranium adsorption isotherm data.

2.5.1. Langmuir isotherm

The Langmuir model [21] is based on the assumption that the maximum adsorption capacity corresponds to the complete coverage of a monolayer of molecules on the surface of the adsorbent without any interaction between the adsorbed molecules. The Langmuir equation for a homogeneous surface is expressed as

| \begin {eqnarray}\label {eqn4} \frac {C_{\mathrm {e}}}{Q_{\mathrm {e}}}=\frac {1}{Q_{\max }K_{\mathrm {l}}} +\frac {C_{\mathrm {e}}}{Q_{\max }} \end {eqnarray} | (4) |

2.5.2. Freundlich isotherm

The Freundlich isotherm model [23] describes adsorption on heterogeneous surfaces in multilayers. The linear form of the Freundlich equation is given by the following equation:

| \begin {eqnarray}\label {eqn5} \mathrm {Log}\, Q_{\mathrm {e}}=\mathrm {Log}\, K_{\mathrm {F}} +\left (\frac {1}{n}\right )\mathrm {Log}\, C_{\mathrm {e}} \end {eqnarray} | (5) |

2.5.3. Dubinin–Radushkevich isotherm

The D–R model [24] assumes that the surface of the material is heterogeneous. This model is more general than the Langmuir and Freundlich models and is used to describe the adsorption on both homogeneous and heterogeneous surfaces [25].

Equation (6) gives the linear form of the D–R equation:

| \begin {eqnarray}\label {eqn6} \mathrm {Ln}\, Q_{\mathrm {e}}=\mathrm {Ln}\, Q_{m}-K\varepsilon ^{2} \end {eqnarray} | (6) |

| \begin {eqnarray}\label {eqn7} \varepsilon =RT \mathrm {Ln} (1+1/C_{\mathrm {e}}) \end {eqnarray} | (7) |

| \begin {eqnarray}\label {eqn8} E_{\mathrm {a}}=1/\sqrt {2K} \end {eqnarray} | (8) |

2.6. Adsorption kinetics

In order to study the uptake mechanism of the uranyl ions by the synthesized ZSM-12 material, two kinetic models were applied to the experimental kinetic data: the pseudo-first-order model and the pseudo-second-order model. The equations associated with these kinetic models are as follows.

Pseudo-first-order model [27]:

| \begin {eqnarray} \mathrm {Log}\, (Q_{\mathrm {e}}-Q_{t})=\mathrm {Log}\, Q_{\mathrm {e}}-K_{1}\frac {t}{2.303} \label {eqn9} \end {eqnarray} | (9) |

| \begin {eqnarray}\label {eqn10} \frac {t}{Q_{t}}=\frac {1}{K_{2}{Q_{\mathrm {e}}}^{2}}+\frac {t}{Q_{\mathrm {e}}} \end {eqnarray} | (10) |

2.7. Adsorption thermodynamics

In order to study the thermodynamic properties of uranyl ion adsorption by synthesized ZSM-12, thermodynamic analysis was carried out at different temperatures. The thermodynamic parameters of the adsorption process such as enthalpy (ΔH°), standard entropy (ΔS°), and standard free enthalpy (ΔG°) were determined using Equations (11)–(13) [29]:

| \begin {eqnarray} &\displaystyle \mathrm {Ln}\, K_{\mathrm {d}}=\frac {\rmDelta S\text {\textdegree }}{R} -\frac {\rmDelta H\text {\textdegree }}{RT} \label {eqn11}\end {eqnarray} | (11) |

| \begin {eqnarray} &\displaystyle \rmDelta G\text {\textdegree }=\rmDelta H\text {\textdegree } -T\rmDelta S\text {\textdegree } \label {eqn12}\end {eqnarray} | (12) |

| \begin {eqnarray} &\displaystyle K_{\mathrm {d}}=\frac {C_{\mathrm {i}}-C_{\mathrm {f}}}{C_{\mathrm {f}}}\times \frac {V}{m} \label {eqn13} \end {eqnarray} | (13) |

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Characterization

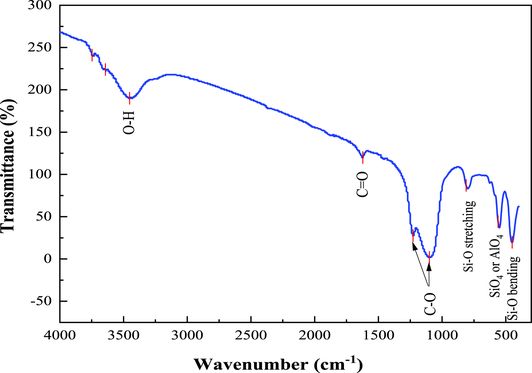

3.1.1. X-ray diffraction

The XRD patterns of the synthesized material are illustrated in Figure 1. The observed patterns show excellent crystallinity as evidenced by the prominent peaks, confirming the efficacy of the hydrothermal synthesis process.

XRD patterns of synthesized material and ZSM-12 zeolite indexed by PDF2 #00-043-0439.

Moreover, the obtained spectrum is consistent with the reference code number 00-043-0439, confirming the ZSM-12 type phase in accordance with the existing literature [30, 31]. The peaks at 7.9°, 8.8°, 20.8°, and 23° were successfully indexed as characteristic diffraction peaks of ZSM-12 zeolite [32]. Furthermore, the peaks at 11.89°, 13.24°, 13.89°, 14.60°, and 15.90° provide evidence for the presence of TPA+ cations [33] with an organized arrangement of the organic template used to synthesize ZSM-12 zeolite within the crystal framework [34].

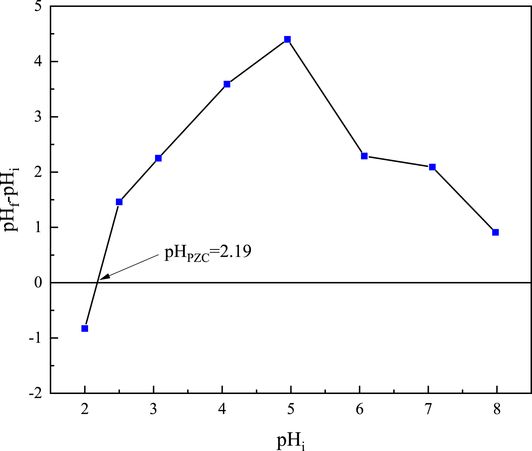

3.1.2. Fourier transform infrared spectrum

In order to identify the functional groups on the surface of the prepared material (ZSM-12), FTIR spectroscopy analysis was conducted in the wavenumber range of 400–4000 cm−1, and the spectrum obtained is shown in Figure 2. The absorption band at 3297 cm−1 could be attributed to the elongation of the O–H bond of hydroxyl groups (alcohols or phenols) [35]. The small band at 1627 cm−1 indicates the C=O stretching vibration in carbonyl groups (aldehydes or ketones) [36]. The bands located at 1227 and 1100 cm−1 can be assigned to the axial deformation of C–O bonds in carboxylic acids, alcohols, esters, and ethers [37]. The bands observed at 798 cm−1 and 548 cm−1 could be attributed to the external symmetric Si–O stretching vibration and the internal vibration mode of tetrahedra (SiO4, AlO4), respectively [38]. Finally, the absorption peak observed at 445 cm−1 corresponds to Si–O bending vibration [38].

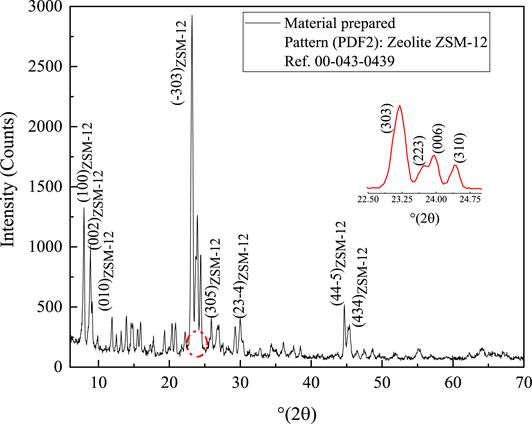

3.1.3. Point of zero charge (PZC)

The acid–base properties of ZSM-12 zeolites were investigated by means of the zero charge point pH (pHPZC) at which the net charge of the particle is zero; the amounts of positive and negative charges at this point are equal [39]. Figure 3 shows the point where the initial and final pH values intersect. The pHPZC value of the sorbent was observed to be 2.19. This value reflects the acidity of this zeolite due to the predominance of acidic groups on its surface [28]. At the point of PZC, the net charge of the sorbent is zero and below this point, the sorption of U(VI) is low. The organic functional groups present in the cells of the sorbent material are charged in a positive or negative way depending on the pH of the solution. Due to the negative charge of the sorbent surface, the sorption process is favored when the pH is above 2.19 [40].

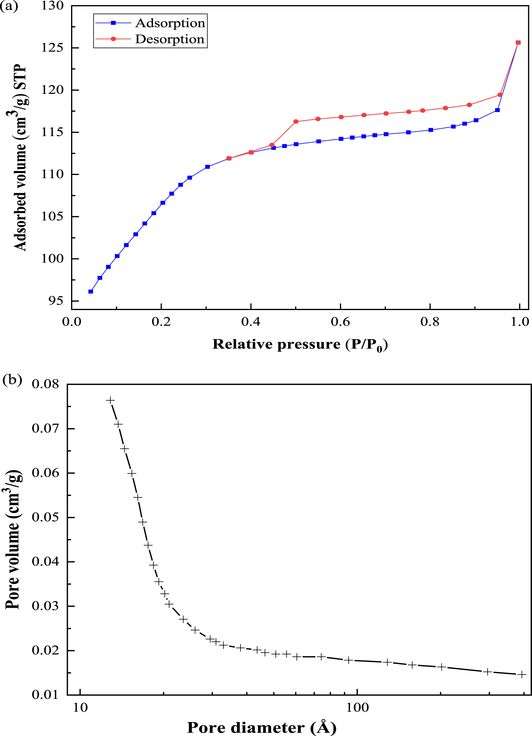

3.1.4. Nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherm

Figure 4 shows the nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherm of the synthesized ZSM-12 zeolite, which is type IV according to the IUPAC classification [41]. A hysteresis loop is observed during the desorption process in the range of 0.4 < P/P0 < 0.95, indicating the coexistence of micro- and mesopores [31, 42]. The large branch of hysteresis indicates that the synthesized ZSM-12 is mainly composed of mesopores accompanied by a few micropores. The mesoporosity might be the result of inter/intracrystalline mesopores corresponding to the zeolitic material as well as the intrinsic mesoporosity of the amorphous material [43]. Furthermore, the synthesized ZSM-12 exhibits a high BET surface area (343.69 m2⋅g−1), low micropore volume (0.1067 cm3⋅g−1), and a small mesopore size (3.0 nm) calculated by BJH models. The narrow mesopore size distribution may be attributed to the nanocrystals that constitute the agglomerates [44]. The high BET specific surface area of ZSM-12 offers abundant adsorption sites, which favors the adsorption of uranium from aqueous solution.

Nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherm (a) and pore size distribution (b) of the ZSM-12 zeolite.

3.2. Adsorption studies

3.2.1. Initial pH effect

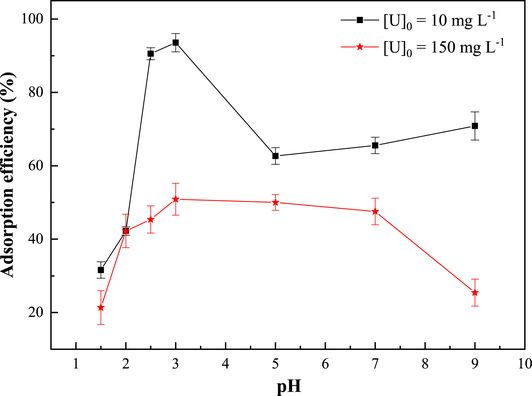

The effect of initial pH on the adsorption of uranium(VI) by the synthesized zeolitic material ZSM-12 was studied in the pH range of 1.5 to 9.0 using initial concentrations of 10 and 150 mg/L. As shown in Figure 5, the adsorption efficiency of uranyl ions increases in the pH range of 1.5 to 3 and then decreases with increasing pH. The highest levels of adsorption efficiency, namely 93% and 50% for initial concentrations of 10 and 150 mg/L, respectively, are observed at a pH of 3. These results can be explained by considering the concentration of hydrogen ions (H+), the pH of the charge zero point (pHPZC), and the speciation of uranium(VI) [45]. At low pH values (pH < pHPZC = 2.19), the active surface functional groups of ZSM-12 zeolite, which are mainly the silanol (Si–OH) and aluminol (Al–OH) groups, and the adsorption of H+(a q) on the zeolite surface cause an increase in the solution pH. Under such conditions, the electrostatic repulsion between $\mathrm{UO}_{2}^{2+}$ and ($\mathrm{SiOH}_{2}^{+}$, $\mathrm{AlOH}_{2}^{+}$) leads to a decrease in the adsorption rate of uranyl ions [46, 47]. In the pH range 2.19 < pH < 3, the surface of ZSM-12 becomes negatively charged with increasing pH. The predominance of the $\mathrm{UO}_{2}^{2+}$ species in this pH zone leads to an increased adsorption efficiency of uranium(VI) via electrostatic attraction between the positively charged uranium species ($\mathrm{UO}_{2}^{2+}$) and the negatively charged functional groups on the surface of ZSM-12. Finally, at pH values higher than 3.0, the surface charge of ZSM-12 remains negative, but complex uranium species such as UO2(OH)+ and $(\mathrm{UO}_{2})_{2}(\mathrm{OH})_{2}^{2+}$ appear [48]. The low adsorption percentage observed in this zone can be explained by the lack of affinity between the material and hydroxylated species.

Effect of pH on the adsorption efficiency of uranium(VI). T = 20 ± 2 °C; contact time = 60 min; R (S/L) = 10 g⋅L−1.

3.2.2. Effect of contact time

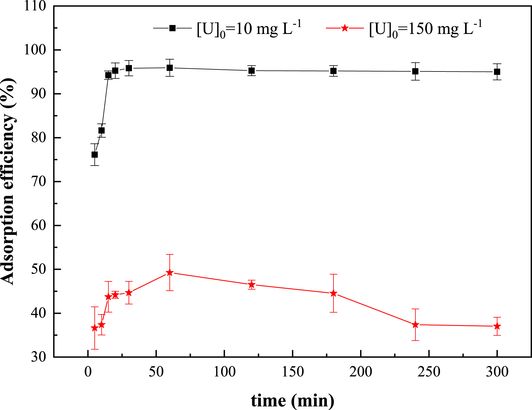

The impact of contact time on the adsorption efficiency of uranium(VI) by the ZSM-12 zeolite adsorbent was explored in a time range of 5–300 min. As shown in Figure 6, the adsorption efficiency of uranyl ions by the synthesized material rises with increasing contact time until it reaches a plateau [48]. The uptake of uranium by ZSM-12 can be delineated into two distinct stages: an initial rapid process occurring within the first 60 min followed by a subsequent very slow phase. Approximately 95% and 50% of the total uranyl ions are adsorbed from uranyl nitrate solutions of 10 and 150 mg⋅L−1, respectively, during the first hour. After this period, most of the active sites on the adsorbent become saturated, marking the end of sorption. It is noteworthy that in the case of the 150 mg⋅L−1 uranyl nitrate solution, the kinetic curve shows a slight decrease in the adsorption rate due to material saturation. A contact time of 1 h is chosen for further investigation.

Effect of contact time on U(VI) sorption on the synthesized ZSM-12 material. T = 20 ± 2 °C; pH = 3; R (S/L) = 10 g⋅L−1.

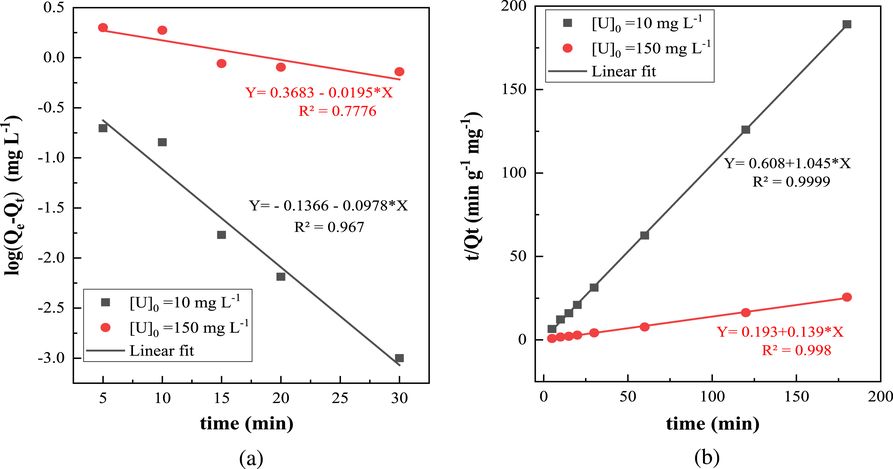

The mechanism of the surface reaction between uranyl ions ($\mathrm{UO}_{2}^{2+}$) and the active sites of ZSM-12 zeolites was tested using the two kinetic equations, namely, pseudo-first-order and pseudo-second-order (Figure 7). The kinetic parameters calculated from the two theoretical models and the values of the regression coefficients are given in Table 1. From Figure 7, we can see that our experimental data follow very well the two kinetic models applied to our system (R2 > 0.96) but with better regression coefficients (R2 > 0.999) if pseudo-second-order reactions are allowed. Therefore, it can be assumed that the adsorption process is controlled by pseudo-second-order kinetics. These results are in agreement with previous research studies, which mentioned that the pseudo-second-order kinetic model described data better than the pseudo-first-order model when investigating U(VI) adsorption by different adsorbents such as cross-linked magnetic chitosan beads [49], magnetic Schiff base [50], chitosan tripolyphosphate beads [51], and cross-linked chitosan [52].

First-order plot (a) and second-order plot (b) for U(VI) adsorption using ZSM-12 as adsorbent. T = 20 ± 2 °C; pH = 3; R (S/L) = 10 g⋅L−1.

Kinetic parameters for the sorption of U(VI) onto ZSM-12

| Pseudo-first-order | Pseudo-second-order | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qe (mg⋅L−1) | K1 (min−1) | R2 | Qe (mg⋅L−1) | K2 (g⋅mg−1⋅min−1) | R2 | |

| [U]0 = 10 mg⋅L−1; R (S/L) = 5 g⋅L−1 |

0.731 | 0.225 | 0.967 | 0.952 | 1.796 | 0.9999 |

| [U]0 = 150 mg⋅L−1; R (S/L) = 8 g⋅L−1 |

2.33 | 0.045 | 0.777 | 7.194 | 0.100 | 0.998 |

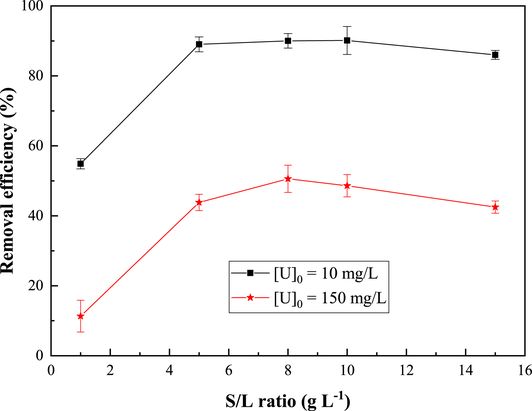

3.2.3. Solid/Liquid ratio effect

Batch experiments were conducted using different solid/liquid ratios to examine the impact of this parameter on the adsorption of uranyl ions by the ZSM-12 zeolite. The results are shown in Figure 8. It is evident that the uranium adsorption efficiency increases with rise in solid/liquid ratio, reaching a maximum at 5 g⋅L−1 and 8 g⋅L−1 for initial concentrations of 10 mg⋅L−1 and 150 mg⋅L−1, respectively. Correspondingly, the adsorption efficiency of U(VI) increases from 54.9% to 89% for the 5 g⋅L−1 ratio and from 11.32% to 50.58% for the 8 g/L ratio, after which a slight decrease is observed. This increasing trend may be attributed to the growing number of adsorption sites and the enhanced contact probability between uranyl ions and the available adsorption sites [53]. Conversely, the decreasing trend could be due to the presence of a large number of active particles, causing overlapping and aggregation, thereby reducing the total surface area available for uranium ion adsorption [54].

Effect of the solid/liquid ratio on U(VI) sorption on the synthesized ZSM-12 material. pH = 3; contact time = 60 min; T = 20 ± 2 °C.

3.2.4. Initial uranium concentration effect

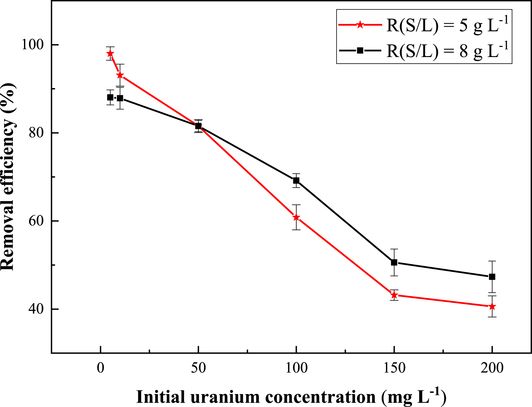

The effect of the initial concentration of uranium on its adsorption by the synthesized ZSM-12 was investigated by varying the concentration of uranium from 5 to 200 mg/L. The experiments were conducted for two solid/liquid ratios of 5 g⋅L−1 and 8 g⋅L−1. The graphs depicting the uranium uptake efficiency in relation to the initial concentration are presented in Figure 9.

Effect of the initial concentration on U(VI) sorption on the synthesized ZSM-12 zeolite. pH = 3; T = 20 ± 2 °C; contact time = 60 min.

The curves in Figure 9 show that the adsorption efficiency of the synthesized ZSM-12 is inversely proportional to the increase in initial uranium concentration. It is known that at low concentration, the mobility of uranium ions is high, which favors their uptake by the adsorbent. However, their mobility decreases as their concentration increases, causing a decrease in adsorption efficiency. In another way, increasing the initial concentration of uranium ions increases the charges of the uranium species in the solution, which increases the Coulomb repulsions, leading to a decrease in the adsorption efficiency. A similar trend was observed by Monika Jail et al. in their studies on the removal of Cr(VI), Cu(II), and Cd(II) using iron oxide/activated carbon nanoparticles [55]. The experimental uranium adsorption capacities (Qe) of the synthesized material were determined by plotting the adsorption capacity as a function of a steady-state uranium concentration as shown in Figure 9. The maximum experimental adsorption capacities of the prepared ZSM-12 zeolite were found to be equal to 14 and 12 mg⋅g−1 for the two solid–liquid ratios of 5 and 8 g⋅L−1, respectively. Table 2 highlights the superior adsorption capacities of ZSM-12 zeolite, especially at different solid–liquid ratios, in comparison with various zeolite-based adsorbents reported in the literature.

Comparison of maximum adsorption capacities of ZSM-12 zeolite with other adsorbents based on zeolite from the literature

| Samples | pH | R (S/L) (g⋅L−1) | Qmax (mg⋅g−1) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZSM-12 | 3 | 5 | 14 | This work |

| ZSM-12 | 3 | 8 | 12 | This work |

| Natural zeolite clinoptilolite | - | - | 1.2 | [56] |

| Natural zeolite clinoptilolite | 6 | 200 | 0.34 | [56] |

| Modified clinoptilolite | 6 | 200 | 4.66 | [56] |

| Hematite material | 7 | 25 | 3.54 | [57] |

| Manganese oxide coated zeolite (MOCZ) | 4 | 5 | 15.1 | [58] |

| Ammonium modified natural zeolite | 5 | 20 | 2 | [59] |

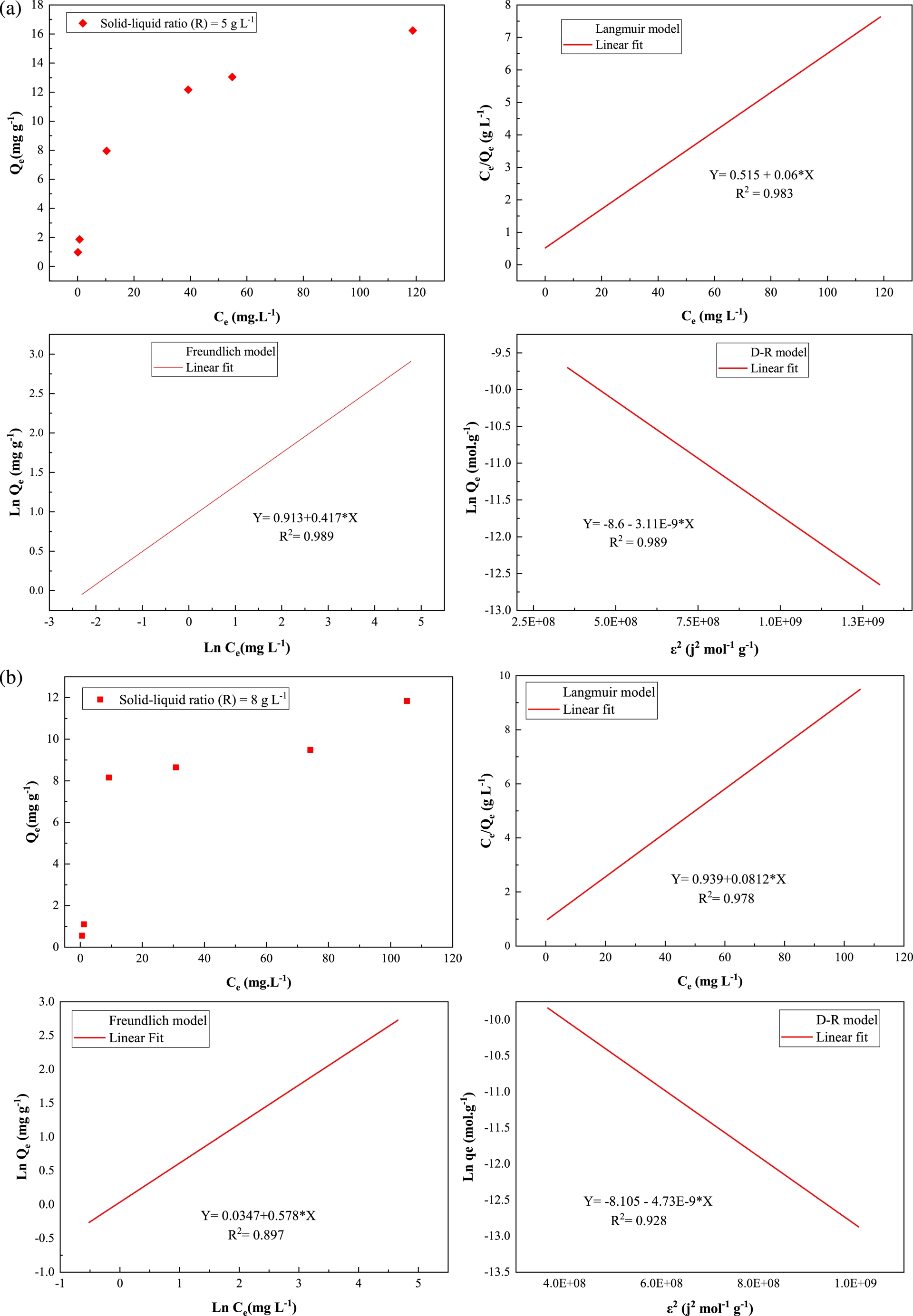

The Langmuir, Freundlich, and D–R models are used to fit the data of the adsorption process of uranium(VI) on ZSM-12 material. The results are shown in Figure 10, and the obtained parameters are listed in Table 3.

Isothermal experimental and fitted data with Langmuir, Freundlich, and D–R models for uranium(VI) adsorption on ZSM-12 zeolite. (a) pH = 3; T = 20 ± 2 °C; contact time = 60 min; R (S/L) = 5 g⋅L−1. (b) pH = 3; T = 20 ± 2 °C; contact time = 60 min; R (S/L) = 8 g⋅L−1.

Adsorption isotherm parameters for U(VI) on ZSM-12 material

| R (S/L) = 5 g⋅L−1 | R (S/L) = 8 g⋅L−1 | |

|---|---|---|

| Freundlich model | ||

| KF | 2.491 | 1.035 |

| n | 2.398 | 1.73 |

| R2 | 0.989 | 0.897 |

| APE (%) | 82.21 | 91.38 |

| Langmuir model | ||

| Qmax (mg⋅g−1) | 16.667 | 12.315 |

| Kl (L⋅g−1) | 0.116 | 0.086 |

| R2 | 0.983 | 0.978 |

| ΔG° (kJ⋅mol−1) | −24.93 | −24.20 |

| APE (%) | 19.05 | 2.625 |

| Dubinin–Radushkevich model | ||

| Qmax (mg⋅g−1) | 49.708 | 81.546 |

| K × 10−9 (mol⋅J−1)2 | 3.11 | 4.73 |

| Ea (kJ⋅mol−1) | 12.68 | 10.28 |

| R2 | 0.989 | 0.928 |

| APE (%) | 255.06 | 314.23 |

The results show that for a solid–liquid ratio of 5 g⋅L−1, the three models fit the experimental data well with high correlation coefficients (R2 > 0.98). However, the calculated APEs for the Freundlich and D–R models are very high (82.21% and 255.06%, respectively). Furthermore, the corresponding adsorption capacity of U(VI) predicted by the Freundlich model is very low (2.49 mg⋅g−1) and that obtained with the D–R model is very high (49.708 mg⋅g−1) compared to the experimental value (14 mg⋅g−1). For a solid–liquid ratio of 8 g⋅L−1, the correlation coefficient (R2) of the Langmuir model is higher than that of the Freundlich and D–R models. In addition, the Qmax value (12.315 mg⋅g−1) for the Langmuir model is more similar to the experimental value (12 mg⋅g−1). Based on the above results, it can be concluded that the Langmuir model is the most suitable for representing the adsorption equilibrium isotherm of uranium(VI) by the ZSM-12 material. This suggests that ZSM-12 provides specific homogeneous sites and sorption of U(VI) ions on the monolayer generated by the ZSM-12 material [57, 60]. The Langmuir separation parameter (Kl) is between 0 and 1, indicating that the adsorption of U(VI) on ZSM-12 is favorable. The estimation of the thermodynamic parameters from the Langmuir model requires using the value of the Langmuir isotherm constant (Kl) in the van’t Hoff equation by multiplying it with the molar weight of uranium(VI) [61]. The free energy is evaluated to be −24.93 and −24.20 kJ⋅mol−1 for the two studied solid–liquid ratios. According to the negative values of energy ΔG°, the adsorption process is both feasible and spontaneous. The values of energy between 0 and −20 kJ⋅mol−1 are generally indicative of physisorption while the values between −80 and −400 kJ⋅mol−1 are indicative of chemisorption [62]. The negative ΔG° values indicate that both chemisorption and physisorption occur simultaneously during the adsorption process.

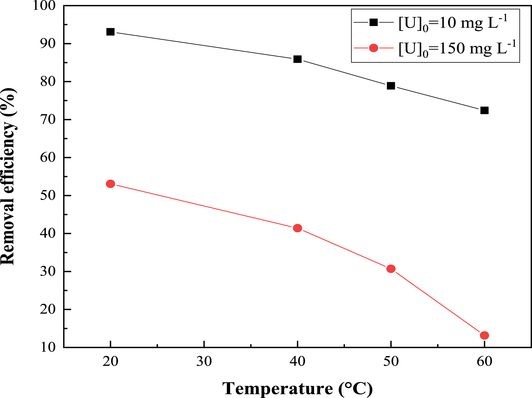

3.2.5. Temperature effect and thermodynamics

The temperature effect was studied by varying the temperature of the uranyl nitrate solution from 20 °C to 60 °C for the two initial uranium concentrations of 10 mg⋅L−1 and 150 mg⋅L−1. The experiments were carried out with a thermostatic bath. The curves in Figure 11 clearly show that the increase in temperature was inversely proportional to the uranium uptake by the studied material ZSM-12. This indicates that the adsorption process was exothermic in nature and that the adsorption of uranium(VI) ions on ZSM-12 was favored at low temperatures. This result can be attributed to fact that the interaction between the active groups on the surface of the adsorbent and the $\mathrm{UO}_{2}^{2+}$ ions was weaker at higher temperature [48, 63].

Effect of temperature on uranium uptake by zeolite ZSM-12. R (S/L) = 8 g⋅L−1; contact time = 60 min; pH = 3.

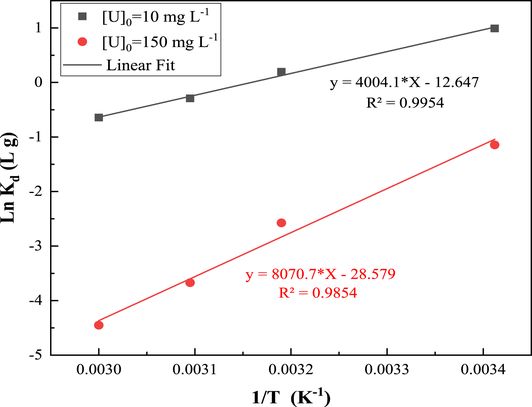

Thermodynamic parameters, such as the enthalpy ΔH° and the entropy ΔS° of the adsorption reaction, are obtained from the slope and intercept of Van’t Hoff plots (Figure 12) and are shown in Table 4.

Variation of Ln Kd versus 1/T for uranium adsorption on ZSM-12 zeolites.

The thermodynamic parameters ΔH°, ΔS°, and ΔG° of uranium adsorption by the ZSM-12 material for the two initial concentrations of 10 and 150 mg⋅L−1

| [U]0 mg⋅L−1 | Temperature (K) | ΔH° (kJ⋅mol−1) | ΔS° (kJ⋅mol−1⋅K−1) | ΔG° (kJ⋅mol−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 293.15 | −33.289 | −0.105 | −2.508 |

| 313.15 | −0.408 | |||

| 323.15 | 0.626 | |||

| 333.15 | 1.691 | |||

| 150 | 293.15 | −67.090 | −0.237 | 2.4975 |

| 313.15 | 7.2475 | |||

| 323.15 | 9.658 | |||

| 333.15 | 11.997 |

The standard enthalpy of the adsorption reaction of uranyl ions by the ZSM-12 material was found to be equal to −33.289 kJ⋅mol−1 for the 10 mg⋅L−1 solution and −67.09 kJ⋅mol−1 for the 150 mg⋅L−1 solution. These results indicate that the adsorption process for the two initial concentrations of uranyl nitrate solutions is exothermic.

Negative values of the adsorption entropy (ΔS°) indicate that the transition of uranyl ions from the aqueous phase to the solid phase (adsorption) results in a reduction in the degree of freedom of the adsorbate, hence the favorable nature of the adsorption and the affinity of the adsorbent toward uranyl ions [64, 65]. Negative values of free energy (ΔG°ads), in the case of an initial uranium concentration of 10 mg⋅L−1, suggest the feasibility and spontaneity of the adsorption reaction, especially at low temperatures. The increase in ΔG°ads with increasing temperature signifies a rise in disorder during adsorption. This phenomenon can be attributed to the redistribution of energy between the adsorbent and the adsorbate [66]. The positive free enthalpy observed at temperatures of 50 °C and 60 °C indicates that an external energy supply is required for the process to occur. For an initial uranium concentration of 150 mg⋅L−1, ΔG° values of the sorbent are obtained as positive, which concludes the reaction to be nonspontaneous, but it shows a range of spontaneity in the reverse direction [67]. In addition, the spontaneous reaction decreases after the initial concentration becomes more significant, and the spontaneous reactivity is negatively correlated with the initial concentration of U(VI) [68].

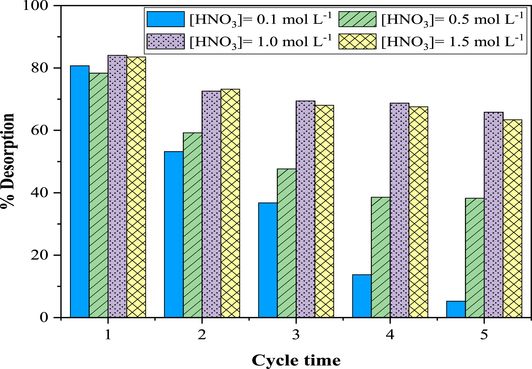

3.3. Reusability of the sorbent

Reusability and regeneration of the used sorbent is an important factor in any removal process. The regeneration process was carried out using a solution of HNO3 as the desorption agent. The effect of the concentration of HNO3 solution was studied in the range of 0.1–1.5 mol⋅L−1. According to Figure 13, a 1.0 mol⋅L−1 solution of HNO3 is the best eluent for the desorption of U(VI) from ZSM-12. After the first adsorption, 84.05% of the adsorbed uranium ions were desorbed, indicating that some adsorption sites with adsorbates cannot be regenerated [69]. The fresh adsorbent has 84.05% sorption sites and its adsorption capacity remains at 9.26 mg⋅g−1 after five adsorption–desorption cycles, which is 65.82% of the fresh adsorbent in the first cycle. In subsequent cycles, the sorption of uranium may be reduced by sorbent loss or partial degradation during the elution process [70] and by the accumulation of uranium molecules on the surface of the ZSM-12 sorbent [71]. However, efforts will be made to improve reuse in the future.

Sequential adsorption–desorption cycles of uranium(VI) on ZSM-12 zeolites. [U]0 = 150 mg⋅L−1; T = 20 ± 2 °C; contact time = 180 min; R (S/L) = 8 g⋅L−1.

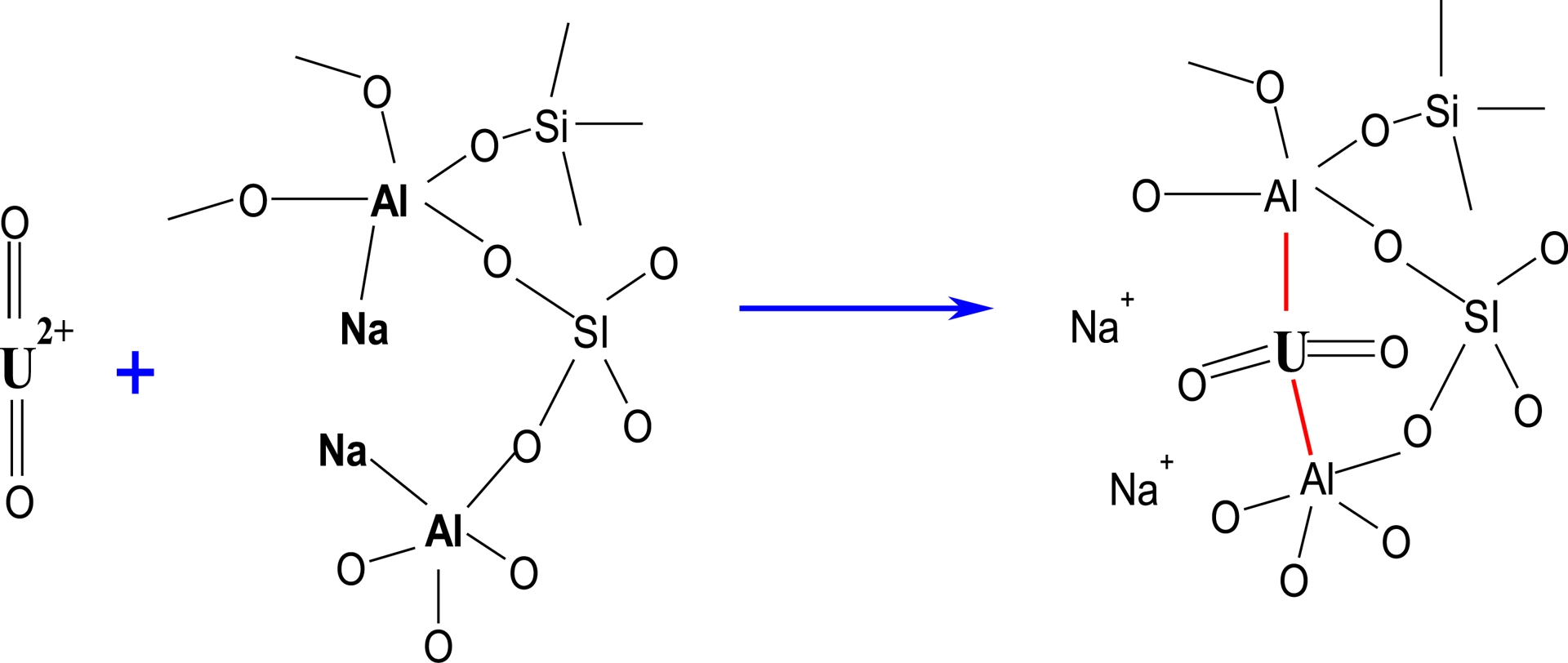

3.4. Adsorption mechanism

The adsorption mechanism of U(VI) on ZSM-12 zeolites is mainly ion exchange as presented in Scheme 1. The divalent cation ($\mathrm{UO}_{2}^{2+}$) is exchanged with two Na+ cations of the ZSM-12 zeolite as already observed by Caputo and Pepe [72] for some toxic and noxious cations, such as Pb2+ and Ba2+, according to Equation (14):

| \begin {eqnarray}\label {eqn14} 2(\mathrm {Na}\hyphen \mathrm {ZSM12})+\mathrm {UO}_{2}^{2+}\rightarrow \mathrm {UO}_{2}(\mbox {ZSM12})_{2} \end {eqnarray} | (14) |

The interaction of surface functional groups of ZSM-12 zeolite with uranyl ions ($\mathrm{UO}_{2}^{2+}$).

3.5. Uranium recovery from a real nuclear effluent by synthesized ZSM-12 material

In order to assess the practical performance of ZSM-12, this material was used for the recovery of uranium from wastewater generated during the processing of uranium ore at the CRND. The optimal parameters obtained from the adsorption study with synthetic uranium solutions were applied. The wastewater consisted mainly of U(VI), Na, K, Ca(II), and Fe(III) with concentrations of 151.69, 9.679, 0.752, 2.708, and 4.502 mg⋅L−1, respectively. Uranium adsorption efficiencies of 38.86%, 41.135%, and 37.57% were obtained with an average yield of 39.18%. As a result, the presence of various ions such as Na, K, Ca(II), and Fe(III) significantly influenced the adsorption behavior of ZSM-12 toward U(VI), resulting in a 21.64% decrease in adsorption efficiency. The initial concentrations of Fe(III), Ca(II), and Na decreased by 65.32%, 76.60%, and 62.72%, respectively. Due to their similar charge and ionic nature, these cations can inhibit the assimilation of uranium ions by participating in competitive adsorption by either trapping or occupying adsorption sites. This competition leads to a reduction in adsorption efficiency for uranium ions [73].

4. Conclusion

In the present work, microporous–mesoporous ZSM-12 zeolite was successfully synthesized by a hydrothermal process, using TPABr as the structuring agent. The structure of ZSM-12 was characterized by XRD, FTIR, and nitrogen adsorption–desorption, which revealed a high specific surface area of 343 m2/g. Adsorption studies demonstrated its efficacy in adsorbing 93% and 50% of the initial uranyl ions ($\mathrm{UO}_{2}^{2+}$) from uranium solutions of 10 and 150 mg/L, respectively, with relatively rapid kinetics well represented by the second-order kinetic model. The equilibrium data fit better to the Langmuir isotherm model. The adsorption energies determined by the Langmuir model confirmed that the adsorption of uranyl ions by the synthesized ZSM-12 material was spontaneous and both chemisorption and physisorption processes occurred simultaneously. The adsorption capacities of the ZSM-12 material were found to be 14.8 mg⋅g−1 and 12 mg⋅g−1 for initial uranium concentrations of 10 and 150 mg⋅L−1, respectively. Thermodynamic parameters indicated that the adsorption of uranium by ZSM-12 zeolite was favored at low temperatures. It can be concluded that the synthesized ZSM-12 zeolite is an effective adsorbent for uranium recovery.

Declaration of interests

The authors do not work for, advise, own shares in, or receive funds from any organization that could benefit from this article, and have declared no affiliations other than their research organizations.

Acknowledgment

This research received financial backing from the Draria Nuclear Research Center (CRND, Algiers). The authors express their gratitude to the General Directorate of the CRND for their financial support.

CC-BY 4.0

CC-BY 4.0