1. Introduction

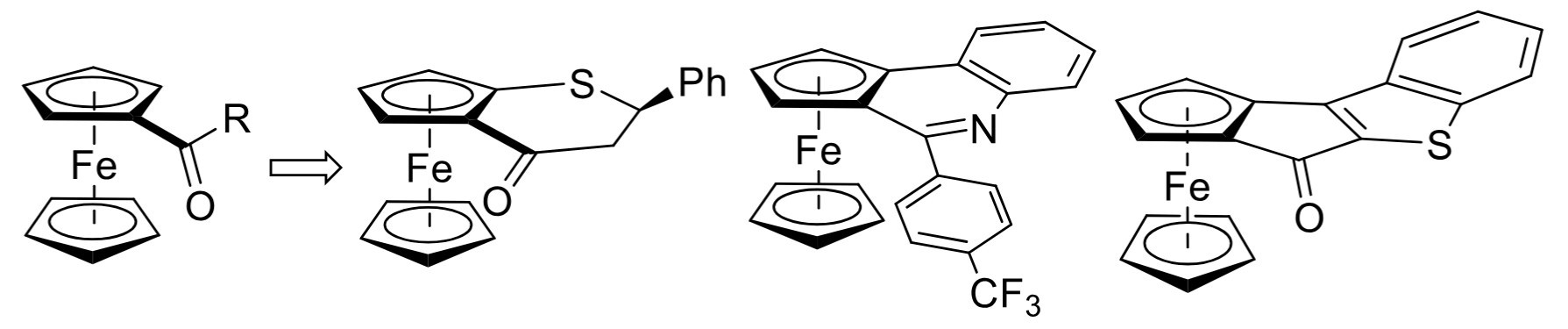

Since the discovery and the structure determination of the parent molecule [1, 2, 3, 4], ferrocenes have attracted considerable interest from synthetic chemists due to their numerous applications [5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13], such as catalysis [14, 15, 16, 17], materials science [18, 19], molecular sensing [20, 21], and bioorganometallic chemistry [22, 23, 24, 25]. In addition to monosubstituted ferrocenes, which can be synthesized from ferrocene via aromatic electrophilic substitution [26] or deprotometalation/trapping sequences [27, 28], polysubstituted structures may be required for targeted applications [29, 30, 31, 32, 33]. Among the most commonly used motifs, 1,1′-disubstituted derivatives are often obtained by double deprotolithiation of ferrocene [34], while 1,2-disubstituted derivatives are typically prepared by directed functionalization of monosubstituted ferrocenes [35, 36, 37, 38].

As a bulky electron-rich aromatic, ferrocene tends to reduce the electrophilicity of the attached functional group [39, 40]. However, although ferrocene ketones are readily accessible by Friedel–Crafts acylation of ferrocene [41], exploiting this change in reactivity to promote their functionalization by deprotometalation/trapping sequences has rarely been explored. In 2000, Enders and coworkers converted ferrocene ketones to enantiopure hydrazones (e.g., using (S)-1-amino-2-methoxymethylpyrrolidine, SAMP) in order to achieve their diastereoselective functionalization by deprotolithiation/trapping sequences [42]. A similar approach was later developed by Top and coworkers using chiral imines derived from ferrocene ketones [43].

To our knowledge, the only study concerning the direct functionalization of ferrocene ketones using lithium bases was reported by Enders and coworkers, who subjected enantiopure diferrocenyl ketones to s-BuLi in the presence of N,N,N′,N′-tetramethylethylenediamine (TMEDA) in toluene at −78 °C for 9 h, prior to interception with various electrophiles [44]. However, the reactivity of the function toward nucleophiles was probably affected by the presence of the two organometallic cores, and the behavior of this particular substrate may not reflect the behavior of aroylferrocenes in general. Thus, when benzoylferrocene was treated with sodium zincate (TMEDA)Na(TMP)Zn(t-Bu)2 [TMP = 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperido] in hydrocarbon solvents at room temperature, mixtures of products were observed, some resulting from deprotonation (mediated by TMP) of the ferrocene core at the site adjacent to the ketone, others from competitive 1,2- and 1,6-addition reactions [45].

In 2010, we reported a synthesis of 1-benzoyl-2-iodoferrocene in 36% yield using a base generated in tetrahydrofuran (THF) from LiTMP (1.5 equiv) and CdCl2⋅TMEDA (0.50 equiv) [46]. Here, our goal is to evaluate an approach using the less toxic ZnCl2⋅TMEDA for the functionalization of ferrocene ketones and to investigate the development of an enantioselective version.

2. Results and discussion

2.1. Preliminary considerations

Our aim in this study was twofold: firstly, to identify suitable conditions to functionalize ferrocene ketones by deprotometalation, and secondly, to understand the regioselectivity observed during this reaction. Indeed, most of the ferrocene ketones studied here have two to four sites that can be functionalized in the presence of organometallic bases.

Our approach involved the use of a hindered lithium amide, LiTMP, in THF containing ZnCl2⋅TMEDA as an in-situ trap [47]. While many deprotometalations using lithium dialkylamides are under thermodynamic control [48], those using the strong base LiTMP can also lead to derivatives functionalized next to a coordinating element, probably via pre-metalation complexes (complex-induced proximity effect) [49, 50] or/and rate-limiting transition states (kinetically enhanced metalation) [51, 52], or benefiting from favorable hydrogen charges (overriding base mechanism) [53, 54, 55, 56]. This is particularly true when using an in-situ trap, as we intended to do.

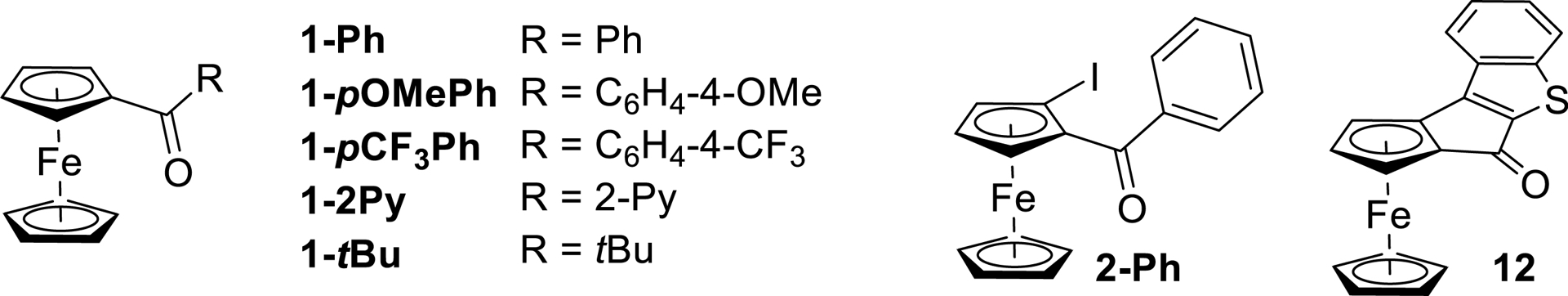

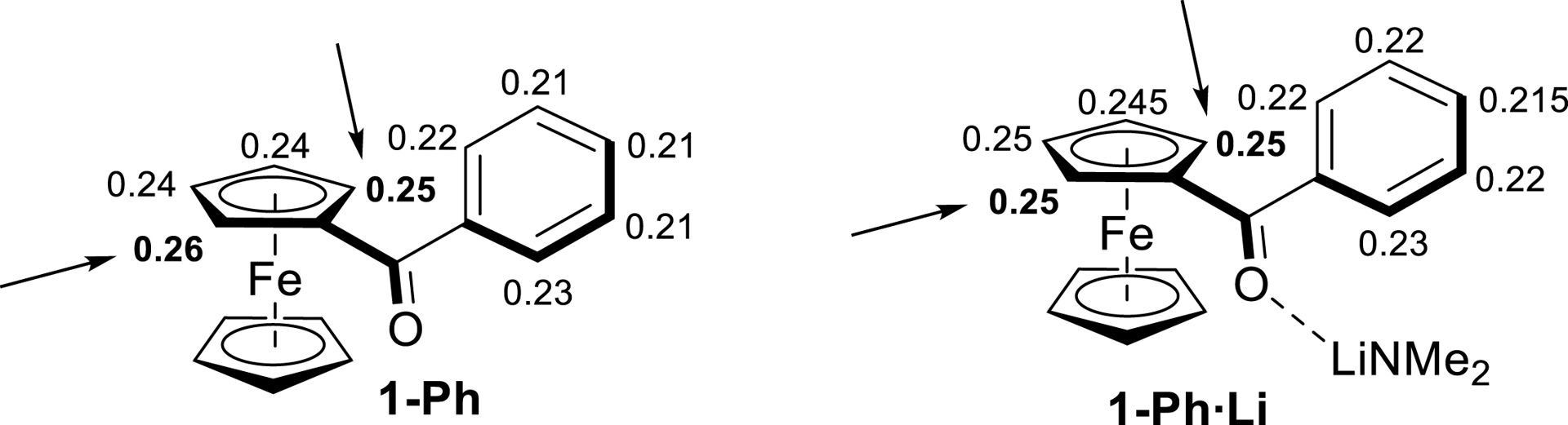

Therefore, to get an idea of the kinetic acidity of the ferrocene ketones selected for the present study, we calculated (see computational details in Supplemantary material) the atomic charges of a few representative examples by natural population analysis (NPA), with and without oxygen coordination to lithium of LiNMe2 chosen as model base. For benzoylferrocene (1-Ph), the most acidic hydrogens were found on the substituted cyclopentadienyl ring of ferrocene, on either side of the benzoyl group (Figure 1, 1-Ph). Further calculations of NPA charges for all hydrogen atoms of the two substituted rings of the complex 1-Ph⋅Li showed comparable results (Figure 1, 1-Ph⋅Li). A similar tendency was observed for the other substrates (Figure S1, in Supplementary material).

Natural-population-analysis charges on hydrogen atoms in the isolated molecule of benzoylferrocene (1-Ph) and impact of coordination to lithium on these charges (complex of 1-Ph with LiNMe2).

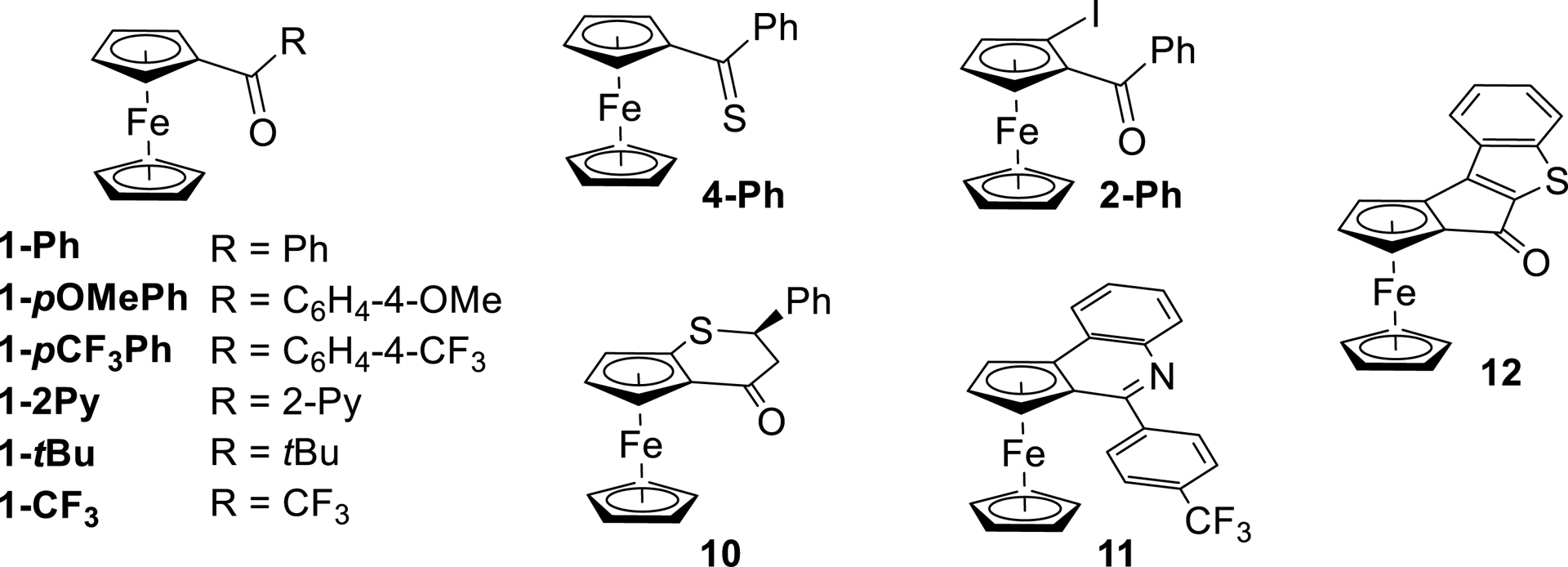

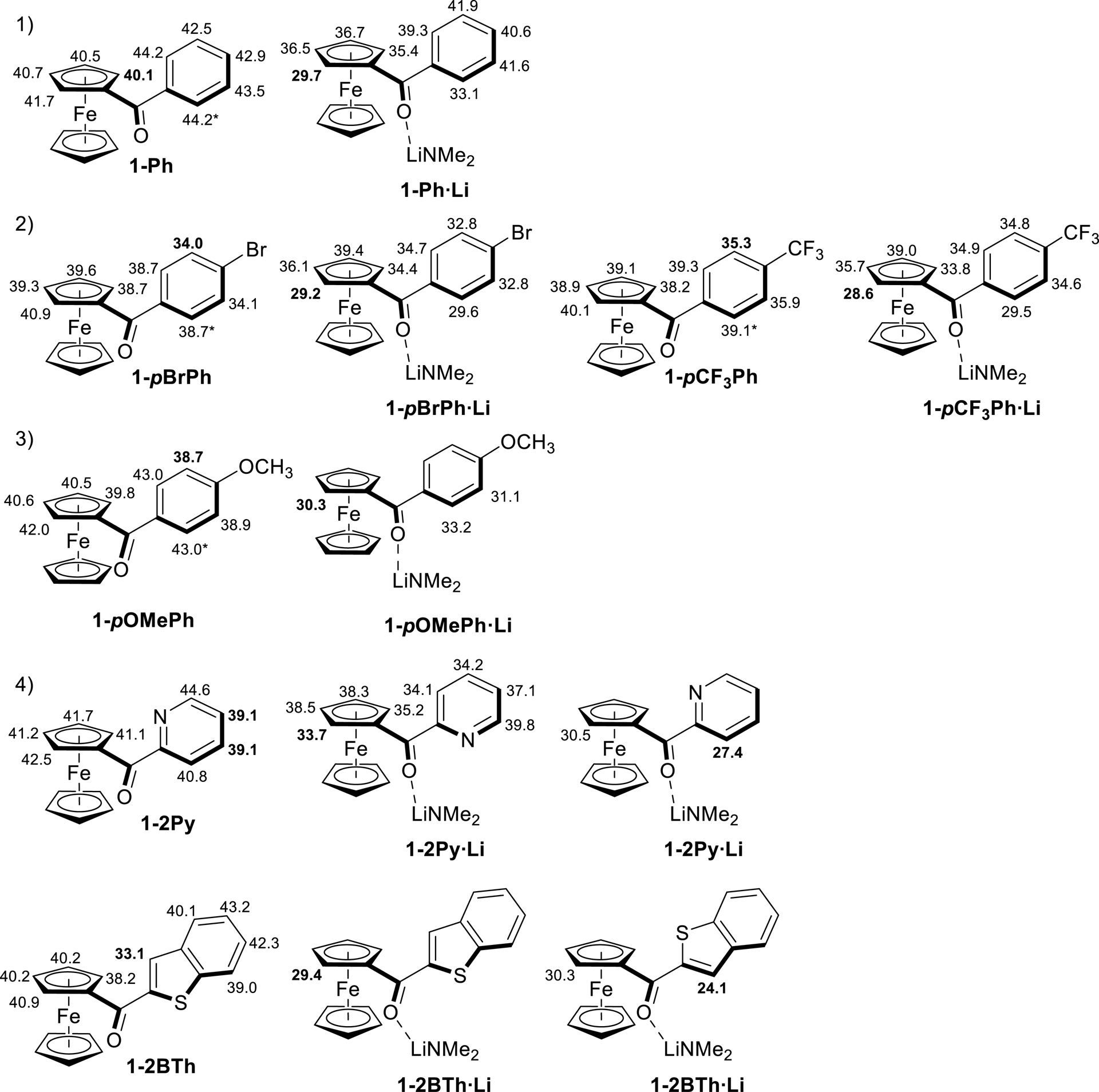

However, formation of the thermodynamic product can also be observed in reactions using strong lithium dialkylamides such as LiTMP [57, 58, 59]. We therefore also calculated significant pKa values for several aroyl ketones in THF within the DFT framework [60, 61, 62, 63] (see Figure S2 in Supplementary material for a complete list). As shown on Figure 2a, the lowest pKa value for 1-Ph corresponds to the ferrocene site next to the carbonyl group. Coordinating the ketone to LiNMe2 (1-Ph⋅Li, to mimic the stabilizing effect that the function exerts on the lithiated derivative formed) also seemed to show that the most stable lithium species was the one deprotonated next to the carbonyl group on the ferrocene side (Figure 2a, 1-Ph⋅Li).

Values of pKa calculated for ferrocene ketones in THF (an asterisk means that deprotonation in the corresponding position is predicted to lead to interring rotation in order to reduce electron repulsion), and impact of coordination to lithium on these values (complexes with LiNMe2).

The introduction of electron-withdrawing substituents such as Br or CF3 on the phenyl group (with compounds 1-pBrPh and 1-pCF3Ph) significantly decreased the pKa values at their adjacent positions (Figure 2b). However, coordination to LiNMe2 restored the desired reactivity, and the species deprotonated on the ferrocene side appeared to be the most stable. A similar, although less pronounced, effect can be noticed for 1-pOMePh (Figure 2c). Finally, in the case of (2-pyridoyl)- and (2-benzothienoyl)ferrocenes (1-2Py and 1-2BTh), the calculations showed different behaviors, with lithium derivatives being more stable when deprotonation occurs on the heterocycle side (Figure 2d). Furthermore, unlike the other benzoylferrocene compounds considered, the conformation adopted by these heterocyclic compounds has a clear impact on their computed pKa values (see Figures S3 and S4 in Supplementary material).

All these data suggest that it should be possible to functionalize most of these derivatives next to the ketone on the ferrocene core, while (heteroaroyl)ferrocenes could afford derivatives functionalized on the heterocycle side. With these predictions in mind, we then subjected our selected compounds to the planned deprotometalation/trapping sequences.

2.2. Functionalization of ferrocene ketones

Various ferrocene ketones have been prepared in the frame of this study (for details, see Supplementary material). Most of the aroylferrocenes were obtained by Friedel–Crafts acylation, by adapting reported procedures [64, 65, 66]. A few other ferrocene ketones were synthesized either by action of lithioferrocene onto the Weinreb 2,2,2-trifluoroacetamide (compound 1-CF3; see Scheme 7) [67] or by reacting heteroarylmetals with the Weinreb amide of ferrocene [68] (compounds 1-2Py and 1-2BTh).

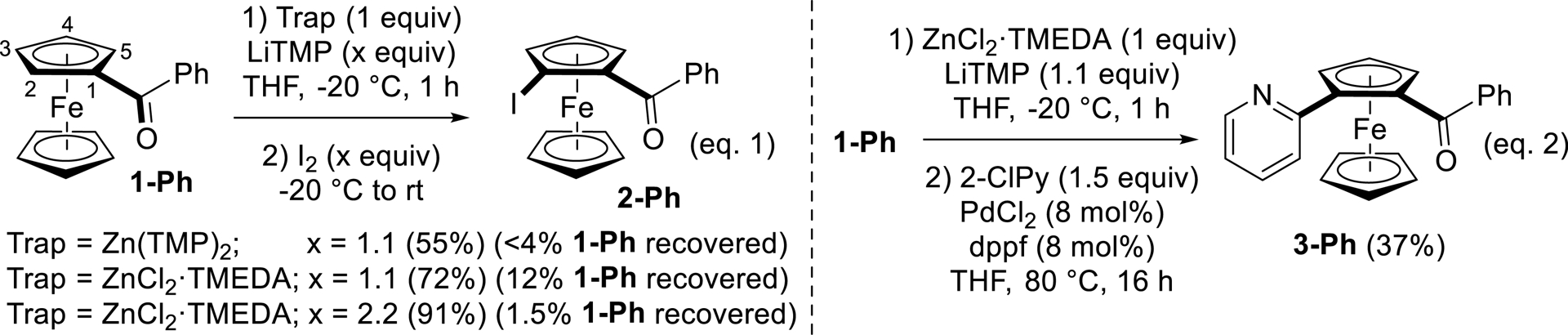

Benzoylferrocene (1-Ph) was chosen to optimize the reaction using LiTMP in the presence of an in-situ trap [47]. We first tested the use of the putative Zn(TMP)2 (generated from 1 equiv of ZnCl2⋅TMEDA and 2 equiv of LiTMP) as an in-situ trap [69] in the reaction of 1-Ph with LiTMP (1.1 equiv) in THF at −20 °C. After subsequent trapping with iodine, the expected product 2-Ph was obtained in a moderate 55% yield although almost complete conversion was obtained (<4% 1-Ph recovered). Replacing Zn(TMP)2 with ZnCl2⋅TMEDA (1.1 equiv) favored the formation of 2-Ph, isolated in 72% yield (91% using 2.2 equiv of LiTMP) (Scheme 1, Equation (1)). The intermediate ferrocenylzinc was also engaged in a Negishi cross-coupling [70, 71] with 2-chloropyridine. Thus, the use of catalytic amounts of PdCl2 and 1,1′-bis(diphenylphosphino)ferrocene (dppf) [72] led to the expected heteroarylated product 3-Ph (37% yield) (Scheme 1, Equation (2)).

Functionalization of benzoylferrocene (1-Ph) by deprotolithiation with in-situ trap, followed by either iodination or Negishi cross-coupling.

We next attempted to use chlorotrimethylsilane instead of ZnCl2⋅TMEDA as the in-situ trap, but we failed to observe the formation of the expected ferrocenylsilane under these conditions. We also tried to replace benzoylferrocene (1-Ph) by (phenylcarbonothioyl)ferrocene (4-Ph), prepared by reacting the former with Lawesson’s reagent [73]. However, as already observed in the case of thionoesters [74], the iodinated derivative was not detected, while we recovered 20% of 4-Ph and 29% of 1-Ph.

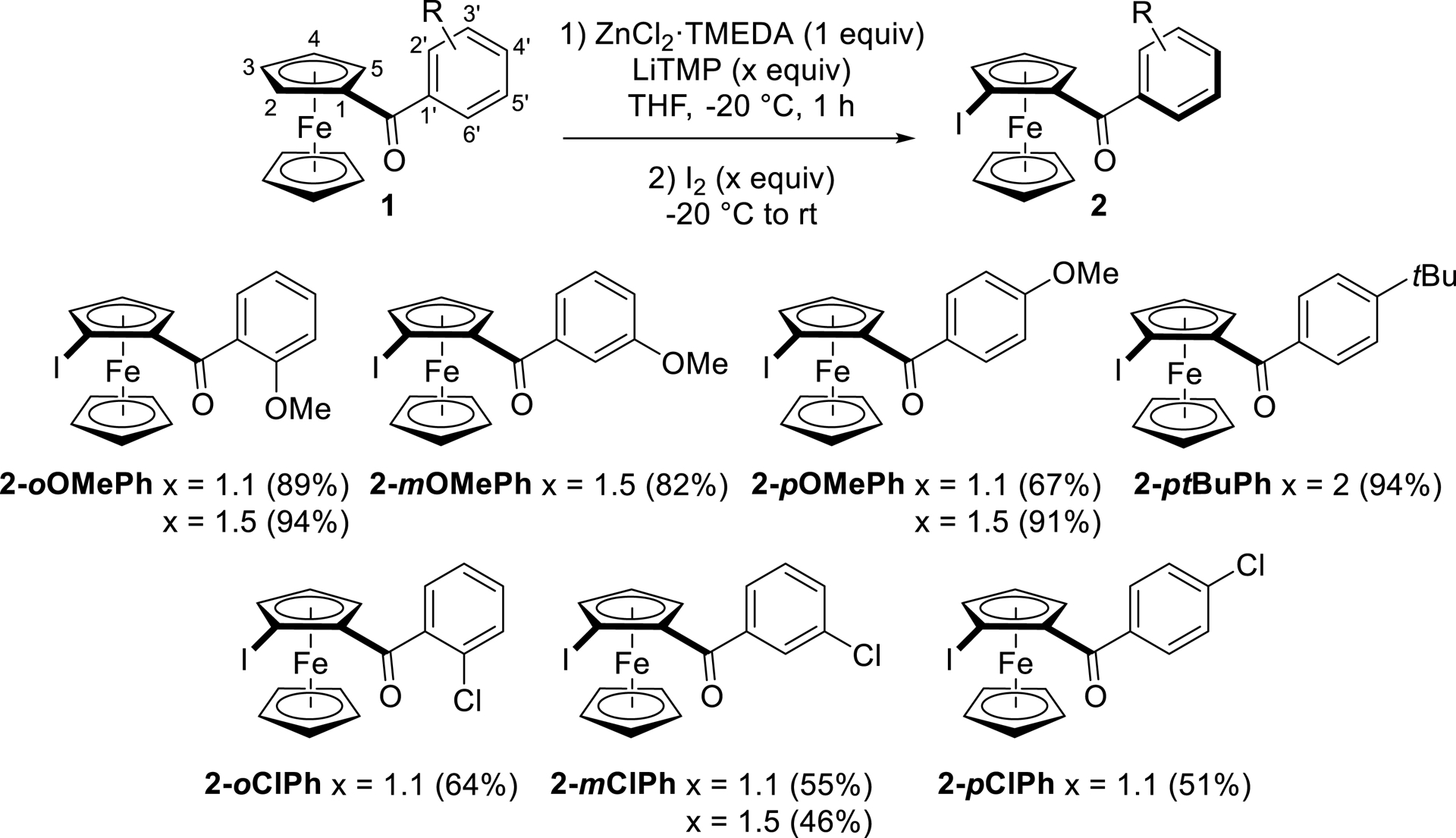

Functionalization at position C-2 of aroylferrocenes was then carried out starting from three different (methoxybenzoyl)ferrocenes, e.g., 1-oOMePh, 1-mOMePh, and 1-pOMePh. As shown in Scheme 2, the amount of base was advantageously increased from 1.1 to 1.5 equiv, enabling the isolation of iodides 2-oOMePh, 2-mOMePh, and 2-pOMePh in yields ranging from 82 to 94%. Functionalization of (methoxybenzoyl)ferrocenes at C-2 is therefore consistent with the calculated pKa values of 1-pOMePh after coordination to lithium (Figure 2c). In the case of (4-tert-butylbenzoyl)ferrocene (1-ptBuPh), derivative 2-ptBuPh was produced in a high 94% yield using 2 equiv of base. Even for the (chlorobenzoyl)ferrocenes 1-oClPh, 1-mClPh, and 1-pClPh, the functionalization took place at the ferrocene site next to the carbonyl group, producing iodides 2-oClPh, 2-mClPh, and 2-pClPh in yields of 51–64%.

Regioselective functionalization of aroylferrocenes at C-2 by deprotolithiation with in-situ trap, followed by iodination.

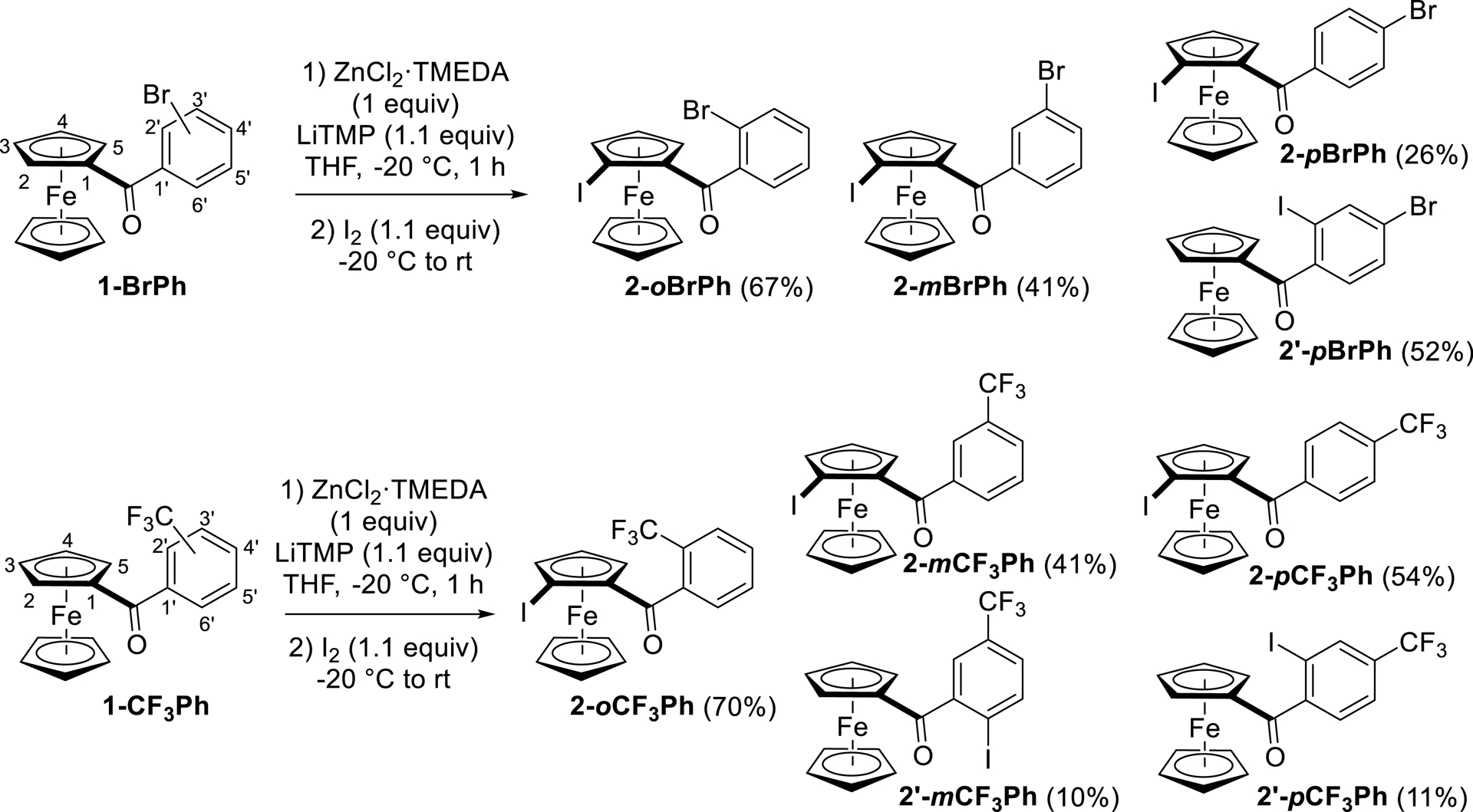

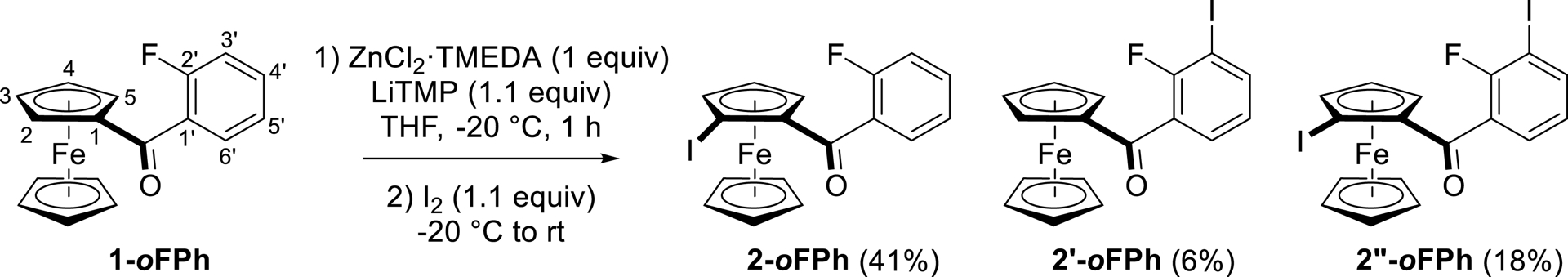

The results were different for the other (halo)benzoylferrocenes. In the (bromoaroyl)ferrocene series, all the derivatives obtained resulted from the functionalization next to the ketone function. However, the iodoferrocenes were formed less efficiently (2-oBrPh > 2-mBrPh > 2-pBrPh), and iodination of the aryl ring was even mainly observed in the case of 2-pBrPh (2′-pBrPh, >50% yield; Scheme 3). This outcome could be rationalized by the combined effects of the ketone function, which promotes deprotolithiation at its neighboring sites, and bromine, which exerts a long-range acidifying effect [75]. This is consistent with the pKa values calculated for 1-pBrPh⋅Li, which are similar for positions C-2 and C-2′ (Figure 2b). A similar trend was noticed in the (trifluoromethyl)ferrocene series, which probably results from the acidifying properties of the trifluoromethyl group in the ortho, meta, and para positions [56, 76] (Scheme 3). For 1-pCF3Ph⋅Li, the pKa difference between positions C-2 and C-2′ is slightly greater than in the case of 1-pBrPh⋅Li (Figure 2b), which could explain the predominance of 2-pCF3Ph, functionalized on the ferrocene side.

Functionalization of (bromobenzoyl)- and [(trifluoromethyl)benzoyl]ferrocenes by deprotolithiation with in-situ trap, followed by iodination.

In contrast to bromine and trifluoromethyl, fluorine is known to be a short-range acidifying group [76, 77]. As a consequence, when (2-fluorobenzoyl)ferrocene (1-oFPh) was treated under the same conditions, the expected product 2-oFPh functionalized on the ferrocene ring (41% yield) was accompanied by (2-fluoro-3-iodobenzoyl)ferrocene (2′-oFPh, 6% yield) and 1-(2-fluoro-3-iodobenzoyl)-2-iodoferrocene (2′′-oFPh, 18% yield), both due to competitive reactions next to the halogen (Scheme 4).

Functionalization of (2-fluorobenzoyl)ferrocene by deprotolithiation with in-situ trap, followed by iodination.

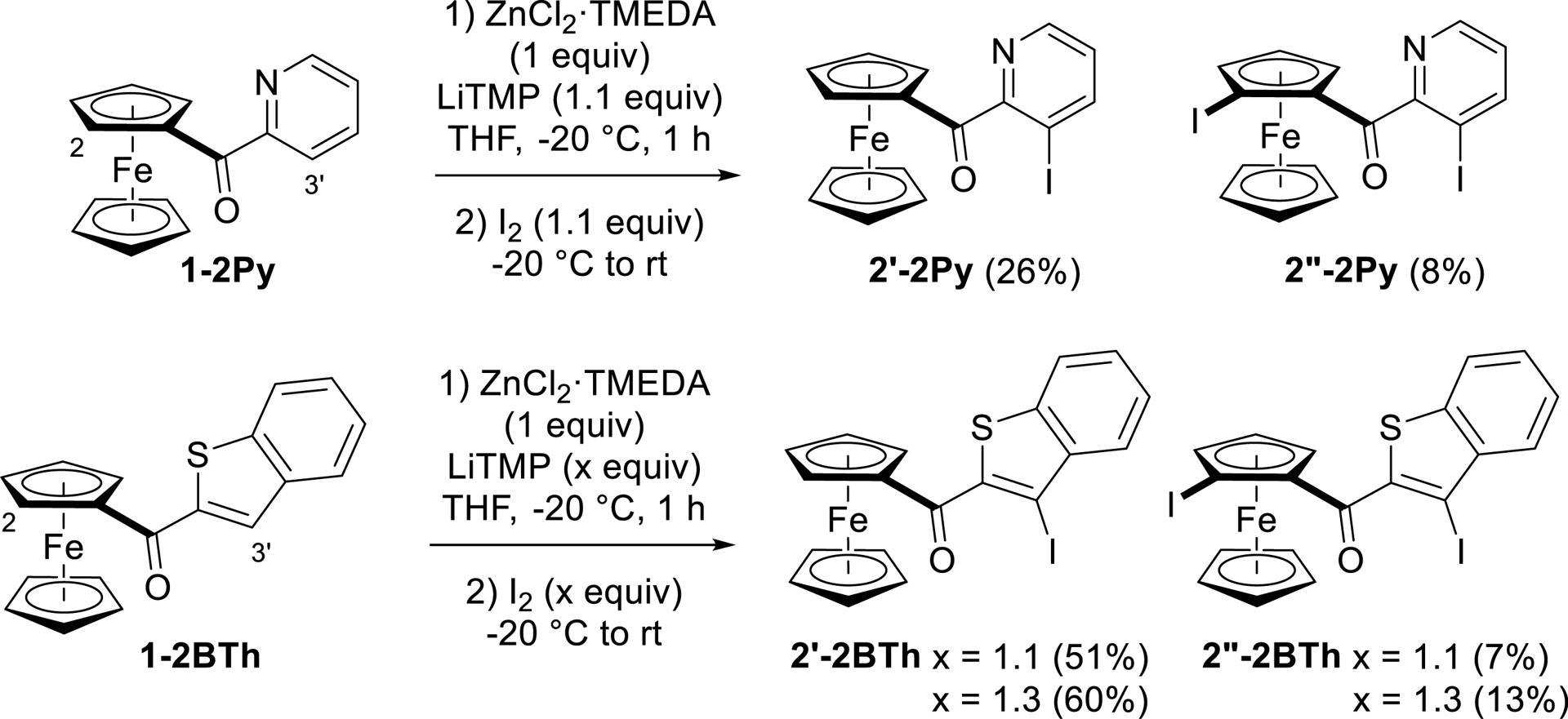

Coordination of (2-pyridoyl)- and (2-benzothienoyl)ferrocenes (1-2Py and 1-2BTh) to lithium decreases their pKa values at position C-3′ by several units, making these sites more prone to deprotometalation than those in position C-2 (Figure 2d). For ferrocene 1-2Py, the calculated pKa difference is about three units, while it reaches six units for ferrocene 1-2BTh. As a result, in these two cases, the main products obtained are iodinated on the heterocycle with 2′-2Py (26% yield) and above all 2′-2BTh (>50% yield). Products monoiodinated on ferrocene were not observed, but the diiodides 2′′-2Pyand 2′′-2BTh, probably resulting from double deprotometalation/trapping, were isolated in ∼10% yield (Scheme 5).

Functionalization of (2-pyridoyl)- and (2-benzothienoyl)ferrocenes by deprotolithiation with in-situ trap, followed by iodination.

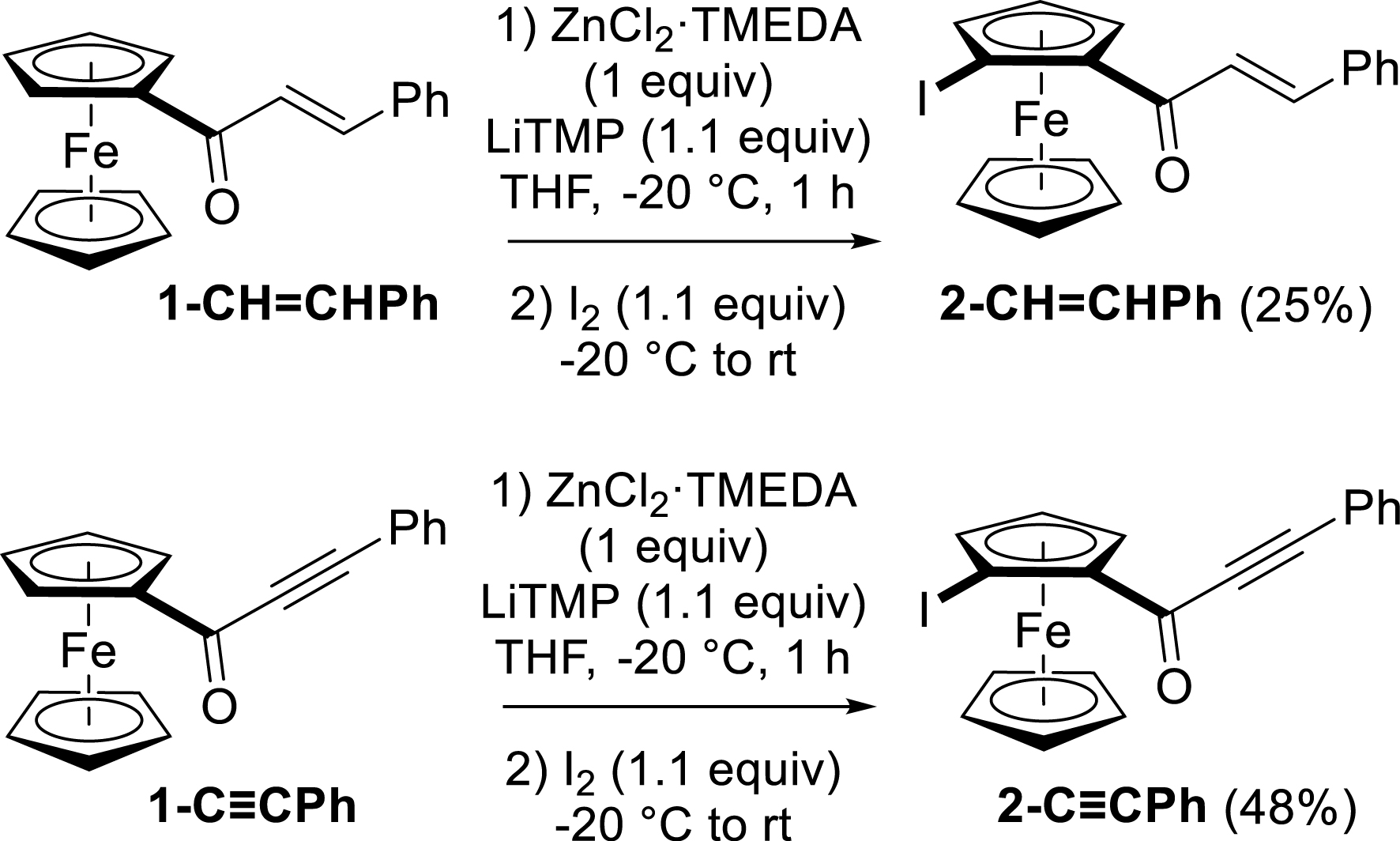

Cinnamoyl- and (phenylpropioloyl)ferrocenes (1-CH=CHPh and 1-C≡CPh) were also involved in the reaction for the purpose of comparison with 1-Ph. The expected products were obtained in both cases, but with lower yields than those observed with 1-Ph. Compound 2-C≡CPh was produced in a higher yield (48%) than 2-CH=CHPh (only 25%), probably due to higher sensitivity of 1-CH=CHPh (only 17% recovered) to nucleophilic attacks, leading to unidentified decomposition products (Scheme 6).

Functionalization of cinnamoyl- and (phenylpropioloyl)ferrocenes by deprotolithiation with in-situ trap, followed by iodination.

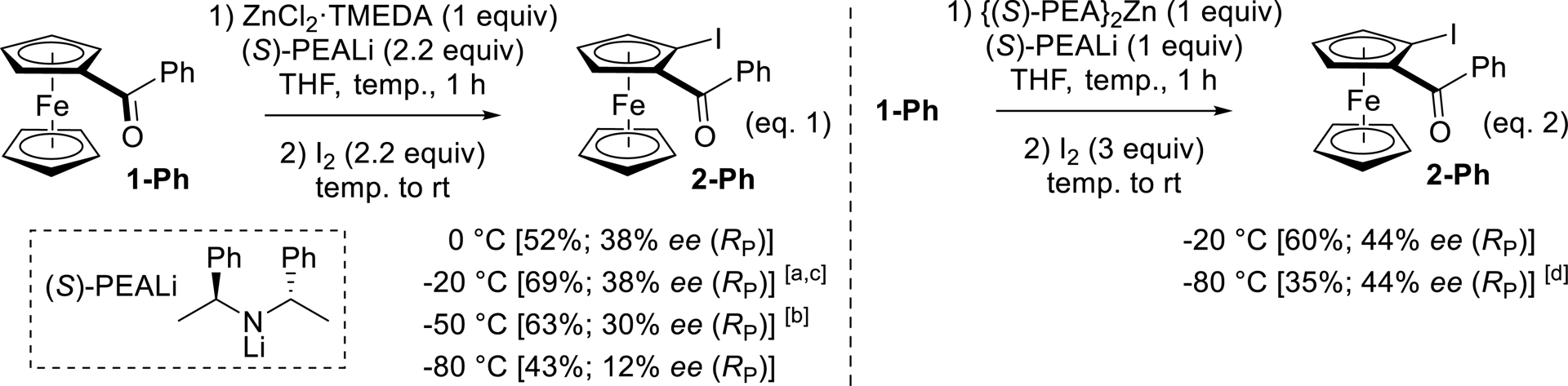

Finally, we compared the reactivities of [(trifluoromethyl)carbonyl]ferrocene (1-CF3) and (tert-butylcarbonyl)ferrocene (1-tBu) under these conditions. As the question of regioselectivity does not arise, 1-tBu was treated with 1.1 or 2.2 equiv of LiTMP to provide, after subsequent trapping, the expected iodide 2-tBu in high yield (75–95%). However, while the use of 1.1 equiv of LiTMP on 1-CF3 afforded 2-CF3 (as an inseparable mixture with 1-CF3) in an estimated 38% yield, using an excess of base was detrimental to the reaction outcome (Scheme 7).

Functionalization of [(trifluoromethyl)carbonyl]- and (tert-butylcarbonyl)ferrocenes by deprotolithiation with in-situ trap, followed by iodination.

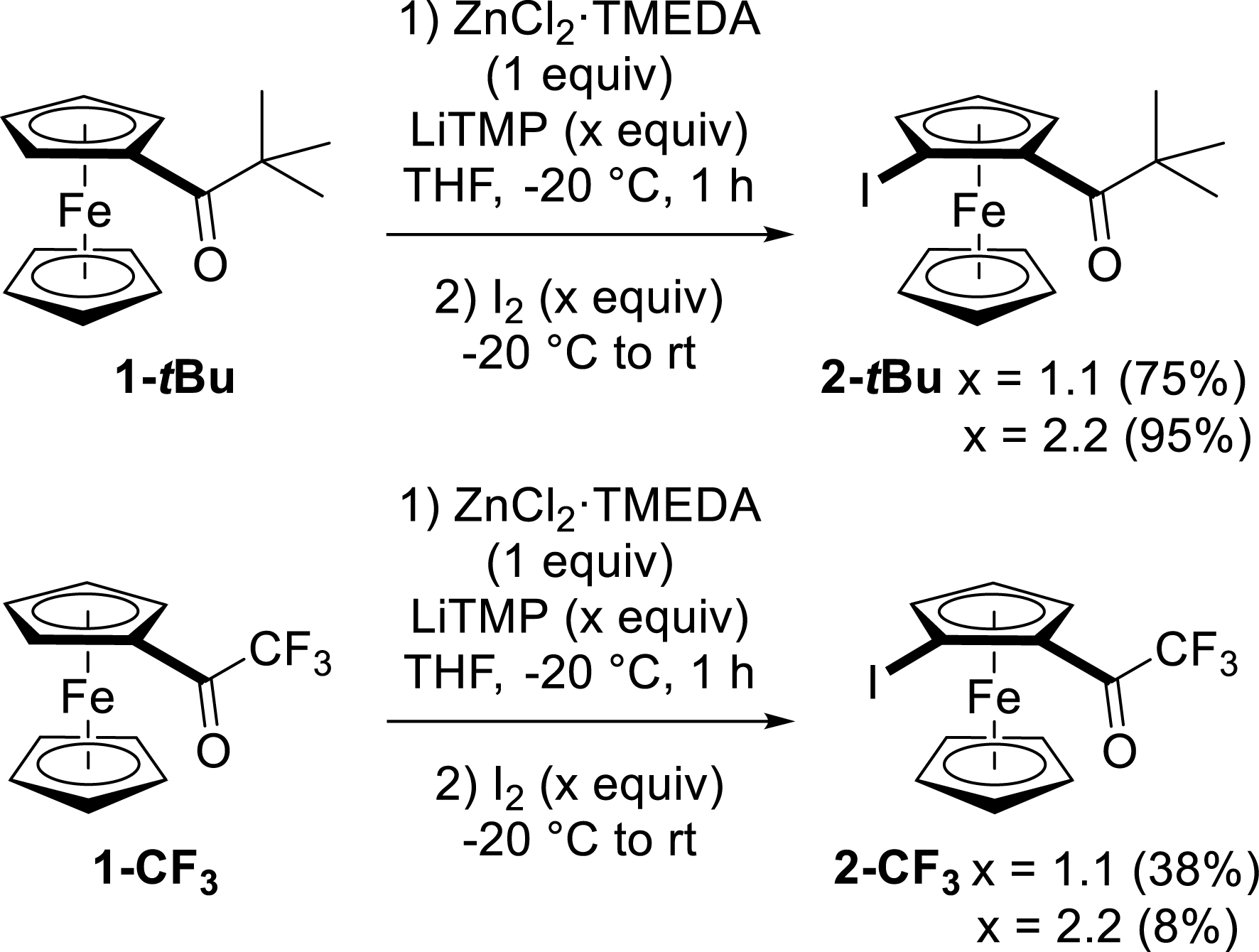

Ferrocene ketones being prochiral substrates, their enantioselective functionalization is expected to deliver enantio-enriched 1,2-disubstituted derivatives [78]. Enantioselective deprotolithiation of ferrocenes substituted by aminomethyl [79, 80] and dimethylamino [81, 82] groups, as well as hindered tertiary carboxamide [83, 84, 85, 86] or even triflone [87], using alkyllithium-chiral ligand chelates (e.g., n-BuLi-sparteine), represents an important achievement in this field. However, as such chiral nucleophilic bases would be barely compatible with a sensitive ketone, we evaluated another approach involving a chiral, non-nucleophilic lithium dialkylamide {lithium di[(S)-1-phenylethyl]amide, (S)-PEALi} in the presence of an in-situ trap, as initially documented by Simpkins [88] and later extended to sensitive ferrocene carboxamides and esters [74, 89, 90]. Regarding the nature of the in-situ trap [91], we selected ZnCl2⋅TMEDA as well as the putative zinc diamide {(S)-PEA}2Zn, obtained in situ from (S)-PEALi and ZnCl2⋅TMEDA in a 2:1 ratio, given their superiority in studies already carried out in the group [87, 92].

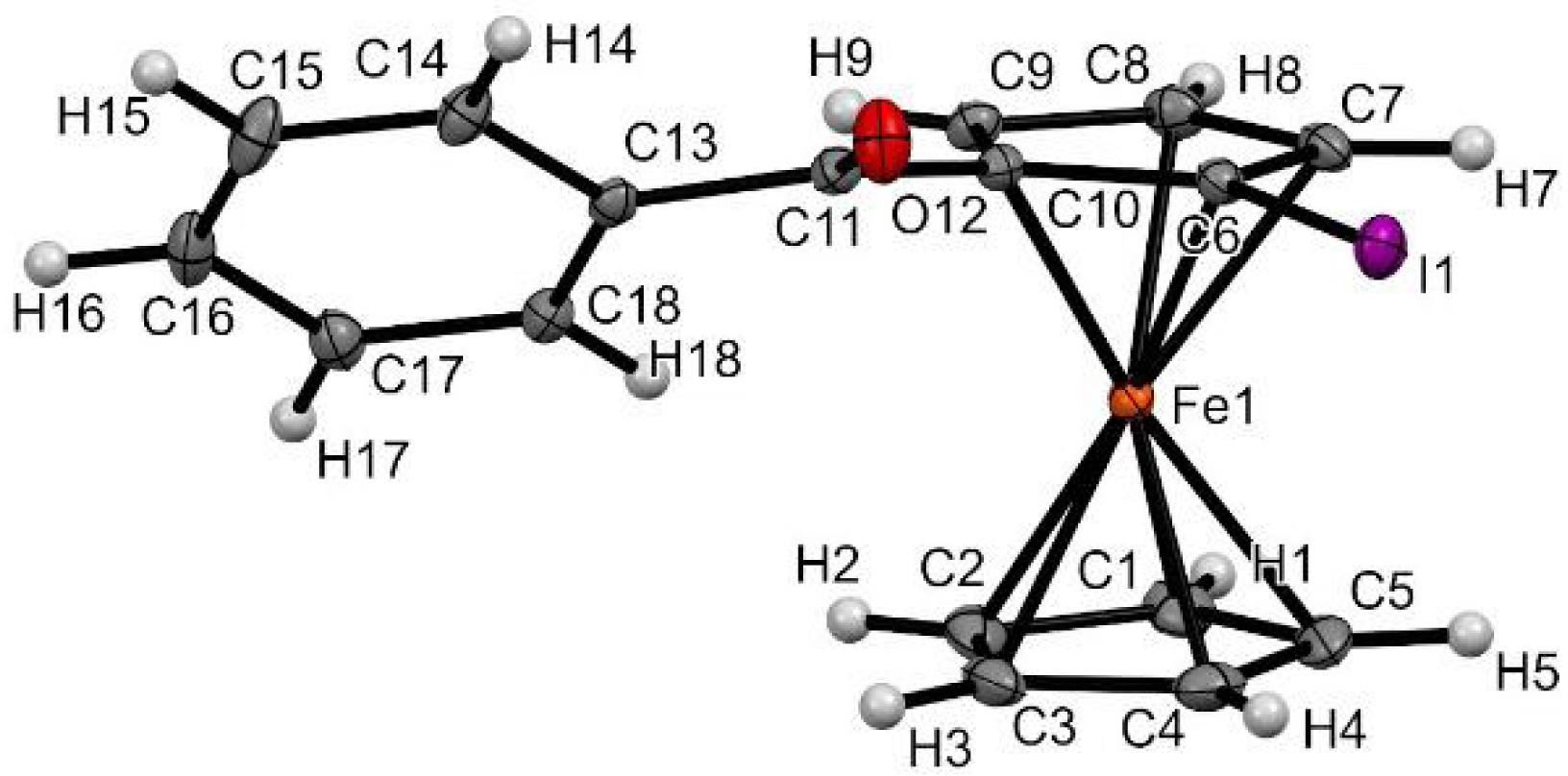

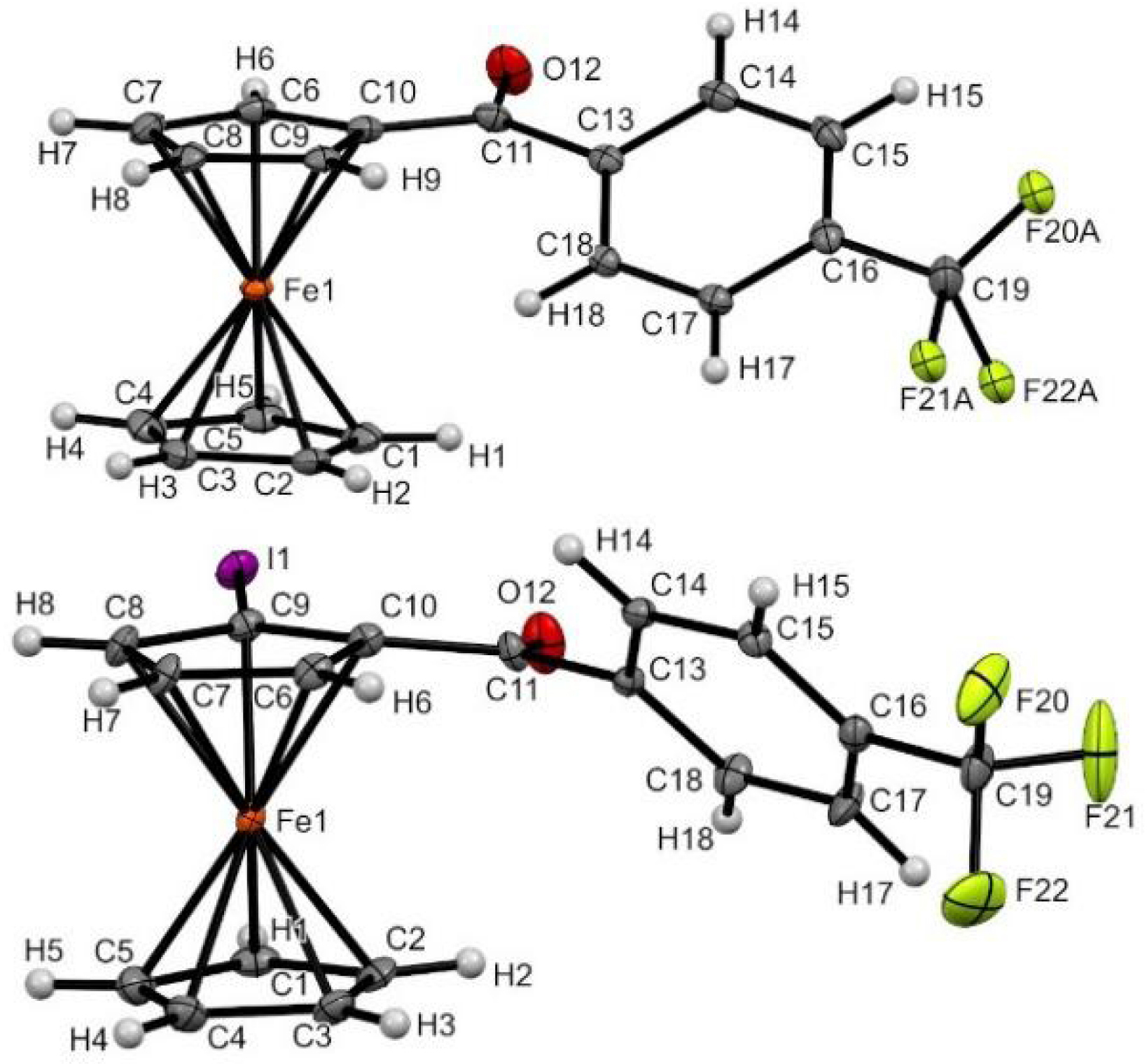

To optimize the reaction, a solution of ketone 1-Ph and ZnCl2⋅TMEDA (1 equiv) in THF was treated with (S)-PEALi (2.2 equiv) at various temperatures (0, −20, −50, and −80 °C) before iodolysis (Scheme 8, Equation (1)). Whereas lower yields of 2-Ph were recorded at −50 °C and even lower at −80 °C, the best enantioselectivities were observed at 0 or −20 °C but did not exceed 38% enantiomeric excess (ee) in favor of the RP enantiomer, as revealed by the growing of crystals suitable for X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis (Figure 3). No change in ee was noticed by using either (R)-PEALi instead of (S) or a shorter contact time. We next attempted the reaction using our alternative in-situ trap, {(S)-PEA}2Zn, instead of ZnCl2⋅TMEDA (Scheme 8, Equation (2)). The reactions were thus repeated at −20 and −80 °C, affording the major RP enantiomer in a slightly improved 44% ee and yields of 60 and 35%, respectively, due to important recovery of 1-Ph at the lowest temperature. In a last attempt to improve the enantioselectivity, THF was replaced by 2-methyltetrahydrofuran (2-MeTHF), which was found helpful in processes involving sensitive species in asymmetric transformations [93]. However, whether using ZnCl2⋅TMEDA at −20 °C or {(S)-PEA}2Zn at −80 °C as an in-situ trap, significantly lower yields (from 69 to 40% and from 35 to 3%, respectively) and enantioselectivities (from 38 to 18% ee and from 44 to 4% ee, respectively) were recorded.

Enantioselective functionalization of benzoylferrocene (1-Ph) by deprotolithiation using the lithium di(1-phenylethyl)amide (S)-PEALi with zinc-based in-situ traps. (a) 67% yield and 38% ee (SP) using (R)-PEALi. (b) 62% yield and 30% ee (RP) after 5 min time. (c) 40% yield and 18% ee (RP) using 2-MeTHF. (d) 3% yield and 4% ee (RP) using 2-MeTHF.

Molecular structure of compound RP-2Ph in the solid state. Thermal ellipsoids shown at the 30% probability level. Selected bond lengths (Å) and angles (°): C10–C11 = 1.475(3), C6–I1 = 2.082(2), C10–Cg2⋯Cg1–C3 = 2.74 (Cg1 being the centroid of the C1–C2–C3–C4–C5 ring and Cg2 the one of the C6–C7–C8–C9–C10 ring), Cg2–C6–I1 = 175.62, C6–C10–C11–O12 = 15.8(4), O12–C11–C13–C14 = 25.9(3).

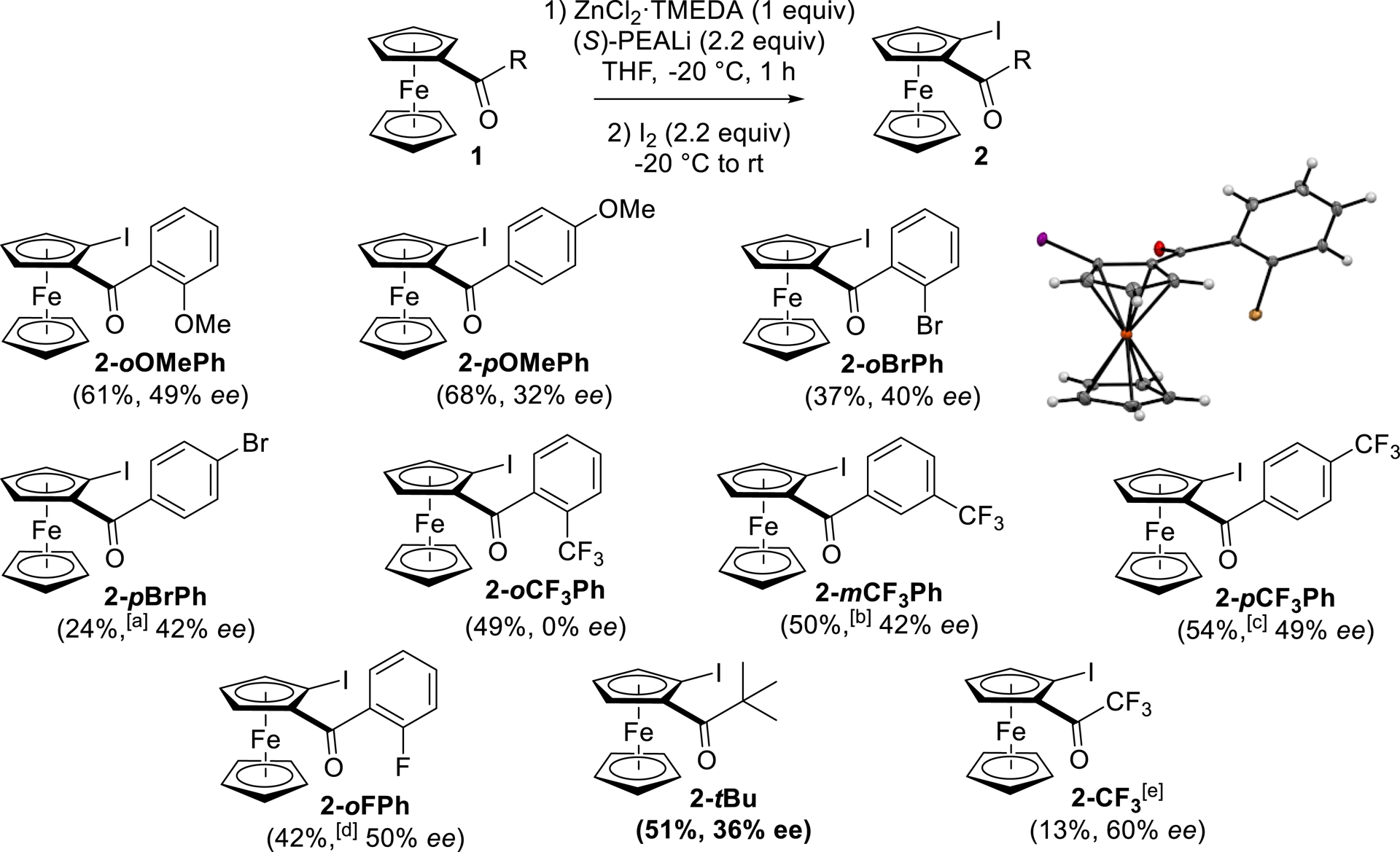

Reactions using ZnCl2⋅TMEDA as an in-situ trap, being considerably easier to implement, were performed at −20 °C to explore the behavior of a selection of ferrocene ketones in asymmetric deprotolithiation (Scheme 9). The yields recorded for these reactions using (S)-PEALi were generally lower than those obtained with the same amount of LiTMP, which can be explained in most cases by the lower reactivity of (S)-PEALi. Using these conditions, ketones 1-CH=CHPh and 1-C≡CPh only afforded mixtures of unidentified products. The ferrocenyl versus aryl deprotonation selectivities were the same, notably with the competitive formation of derivatives iodinated on the aryl group in the case of 1-pBrPh, 1-oFPh, 1-mCF3Ph, and 1-pCF3Ph. The enantioselectivities remained modest at best, ranging from 0% for the sterically hindered ketone 1-oCF3Ph to 60% for the trifluoromethylketone 1-CF3. Pleasingly, crystallization of 2-oBrPh afforded an enantiopure product (see Supplementary material), and XRD analysis validated the expected RP configuration.

Enantioselective functionalization of ferrocene ketones by deprotolithiation using the lithium di(1-phenylethyl)amide (S)-PEALi with ZnCl2⋅TMEDA as an in-situ trap. (a) 2′-pBrPh also obtained in 50% yield. (b) 2′-mCF3Ph also formed in 8% yield. (c) 2′-pCF3Ph also formed in 16% yield. (d) 2′-oFPh (23% yield) and 2′′-oFPh (15% yield, 28% ee) also formed. (e) Reaction carried out by using (S)-PEALi (1.1 equiv) and I2 (1.1 equiv).

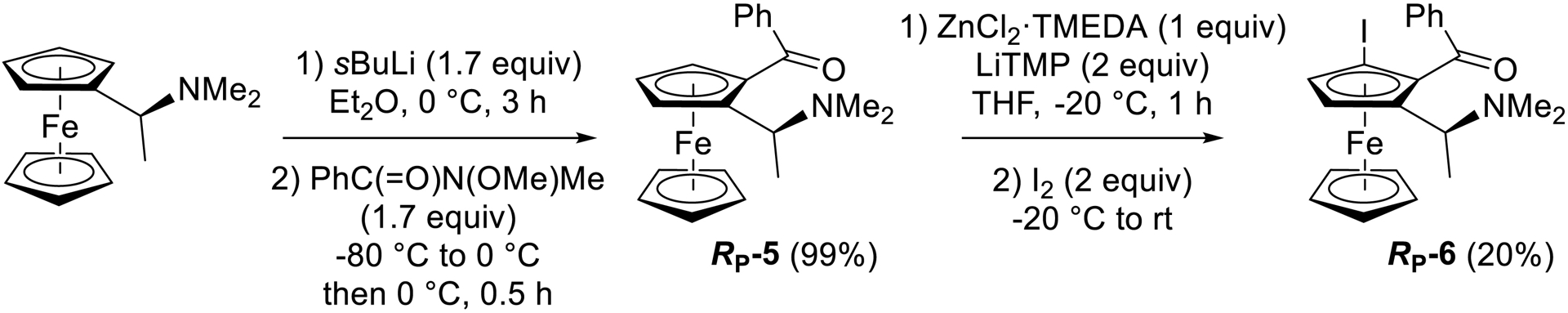

Slightly disappointed by these results, we next turned our attention to a diastereoselective approach and prepared the enantiopure ferrocene ketone RP-5 from [(S)-1-(dimethylamino)ethyl]ferrocene (Ugi’s amine) [94, 95] (Scheme 10). Further treatment of RP-5 with LiTMP (2 equiv) in THF containing ZnCl2⋅TMEDA (1 equiv) at −20 °C before iodolysis afforded the expected iodoferrocene RP-6 as a single diastereoisomer, albeit in a low 20% yield due to recovery of RP-5 (about 20%) and formation of unidentified byproducts (Scheme 10).

Diastereoselective conversion of Ugi’s amine to the ketone RP-5 and further conversion to the enantiopure iodoketone RP-6.

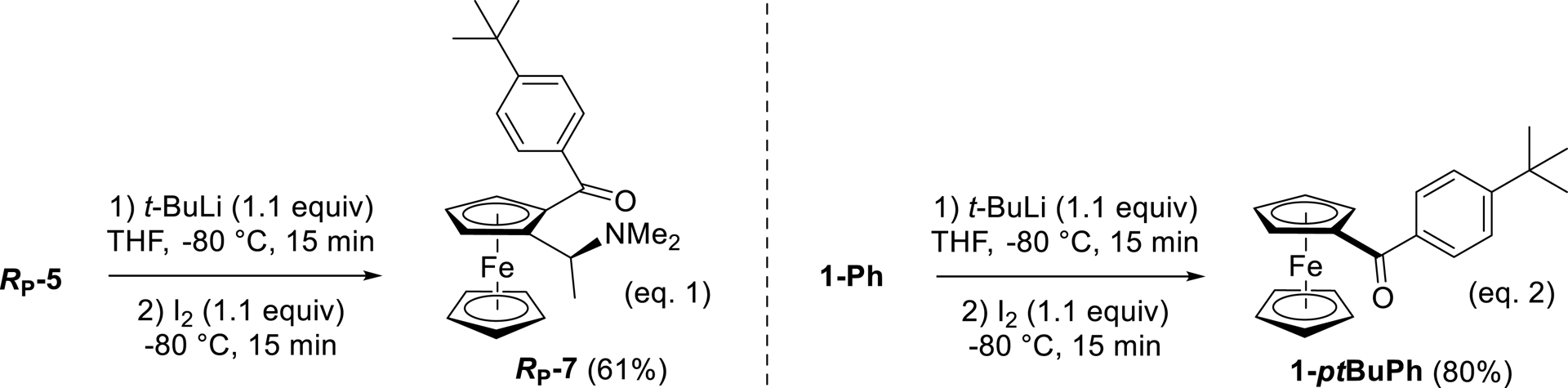

In 1991, Olah and co-workers reported the ring tert-butylation of benzophenones by successive action of t-BuLi in THF at very low temperature and SOCl2 [96]. Inspired by these results, we similarly treated RP-5 with t-BuLi at −80 °C for 15 min before addition of I2 to either intercept a deprotometalated species or oxidize a 1,6-adduct. Pleasingly, we were able to isolate the 1,6-addition/rearomatization product RP-7 in 61% yield (Scheme 11, Equation (1)). A similar result was recorded from benzoylferrocene (1-Ph), with 1-ptBuPh obtained in 80% yield (Scheme 11, Equation (2)).

Ring tert-butylation of RP-5 and 1-Ph.

In the course of their studies on the reactivity of organolithium compounds toward ketones, Yamataka and coworkers obtained both the products coming from the 1,2-addition (65%) and the 1,6-addition/rearomatization (28%) by reacting benzophenone with t-BuLi in Et2O at 0 °C [97]. The use of various tert-butylzinc species in order to achieve para-selective tert-butylation of benzophenone [98, 99, 100] and other (hetero)aromatic ketones [101] has also been extensively studied. In our case, the major 1,6-addition observed by simply using t-BuLi could be explained by the lower electrophilicity of the ketone and the higher steric hindrance generated by the ferrocene core when compared with benzophenone.

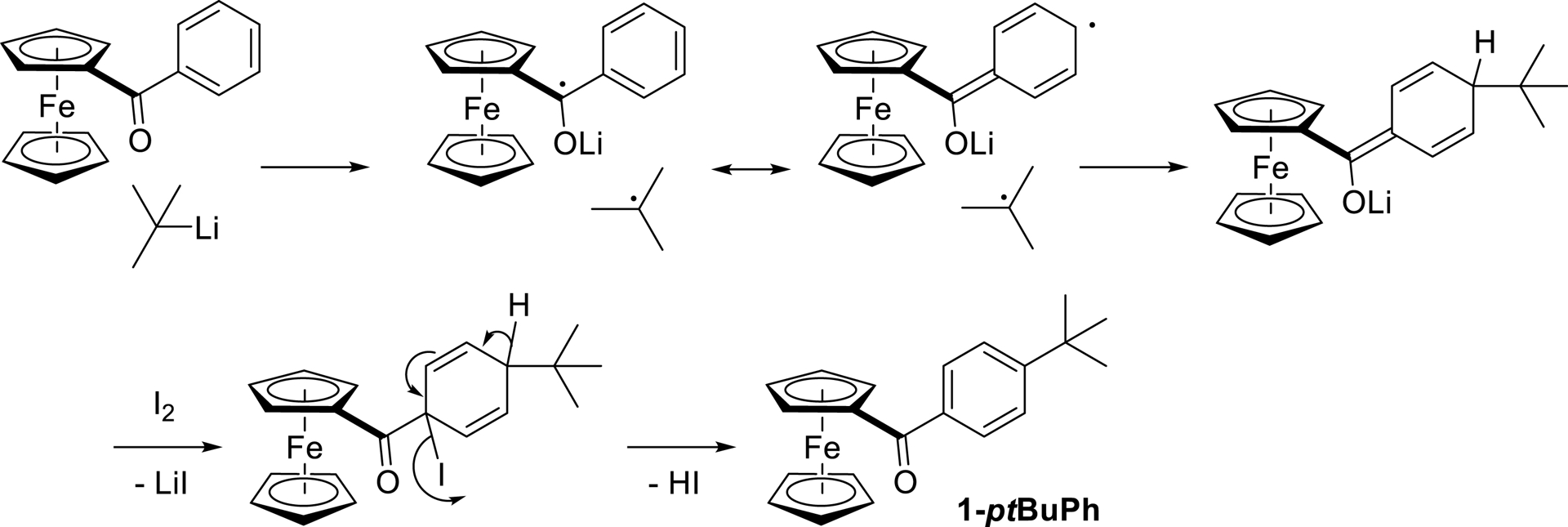

Whether using t-BuLi [97] or tert-butylzinc species [102], all the studies of this reaction have pointed out a single electron transfer mechanism from the alkylmetal to the ketone. Applied to 1-Ph, the formation of 1-ptBuPh could unfold as depicted in Scheme 12.

Proposed mechanism for the tert-butylation of 1-Ph.

2.3. Post-functionalization toward polycyclic compounds

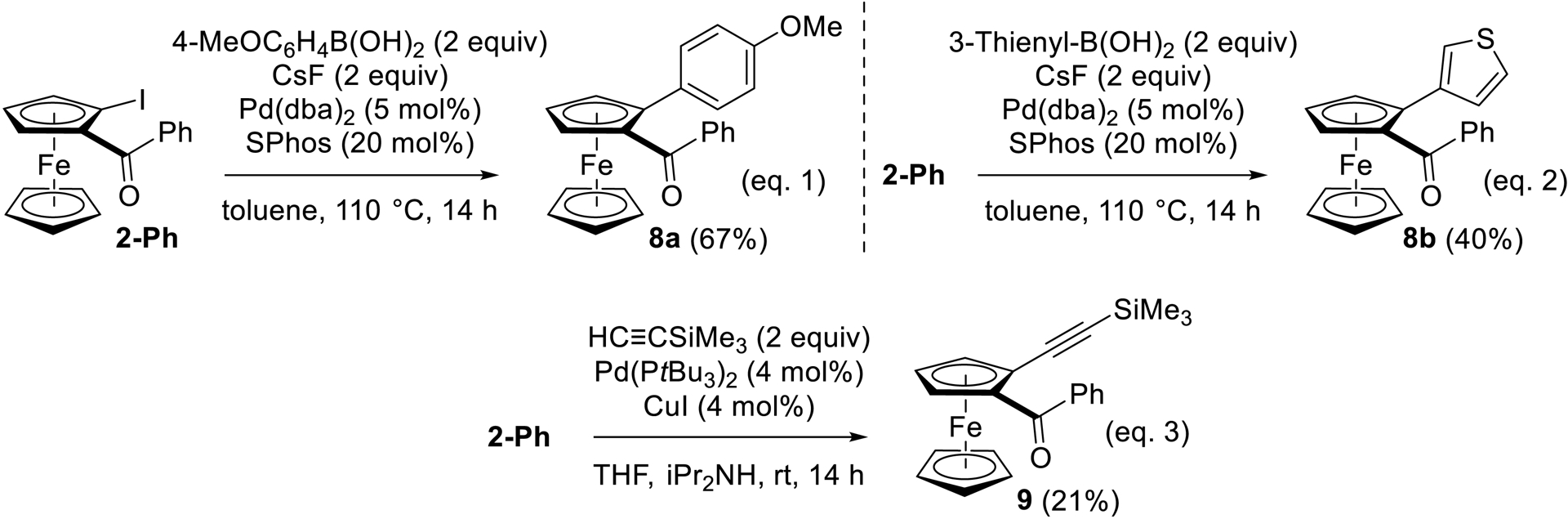

Some of our iodinated ferrocene ketones were next engaged in metal-promoted transformations, and post-functionalization by Suzuki–Miyaura cross-coupling [103, 104] was first considered from 2-Ph. The reactions were carried out with 4-methoxyphenyl- and 3-thienylboronic acid, under conditions previously tested [105, 106] (2 equiv CsF [107], 5 mol% Pd(dba)2 (dba = dibenzylideneacetone) and 20 mol% SPhos (2-(dicyclohexylphosphino)-2′,6′-dimethoxybiphenyl) [108] in refluxing toluene), to afford the derivatives 8a and 8b (Scheme 13, Equation (1) and (2)). A Sonogashira cross-coupling [109] was next attempted with (trimethylsilyl)acetylene, under conditions previously reported [40, 110] [4 mol% Pd(PtBu3)2 and 4 mol% CuI in THF-iPr2NH at rt]. Although the expected product 9 was obtained in a low 21% yield due to 55% recovery of 2-Ph (Scheme 13, Equation (3)), it could be a promising substrate for accessing biologically active ferrocene derivatives such as prostaglandin analogues [111].

Suzuki–Miyaura and Sonogashira cross-coupling reactions from 2-Ph.

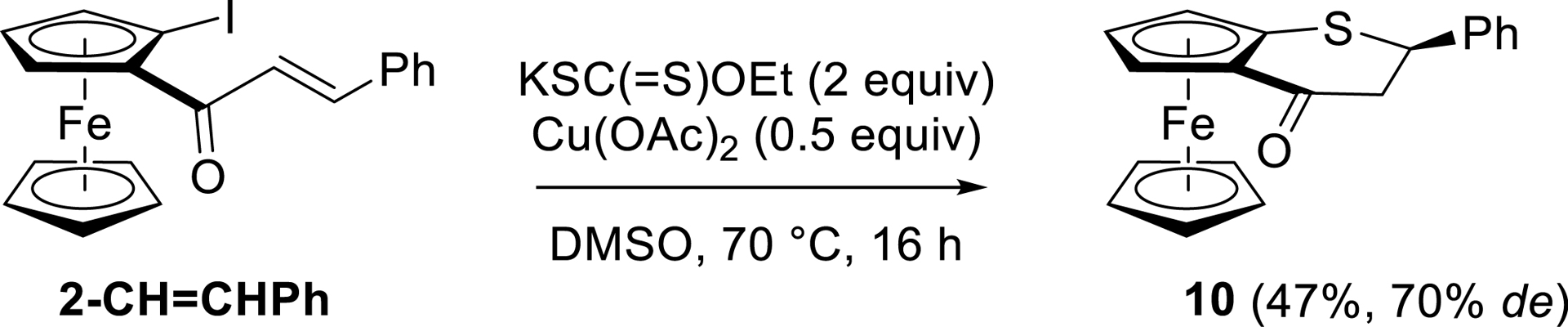

In the last decade, ferrocenes fused with heterocycles such as pyridine [112], 4-pyridone [112], and 4-piperidinone [113] have appeared as privileged structures for different applications [114]. With the aim of preparing a sulfur-containing related compound and inspired by similar reaction in the benzene series [115], we reacted (E)-1-cinnamoyl-2-iodoferrocene (2-CH=CHPh) with potassium ethyl thioxanthate in the presence of Cu(OAc)2 in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) at 70 °C. Pleasingly, we were able to isolate the expected 2,3-dihydrothiopyrano[2,3]ferrocen-4-one 10 in 47% yield and 70% de (Scheme 14).

Conversion of 2-CH=CHPh to the 2,3-dihydrothiopyrano[2,3]ferrocen-4-one 10.

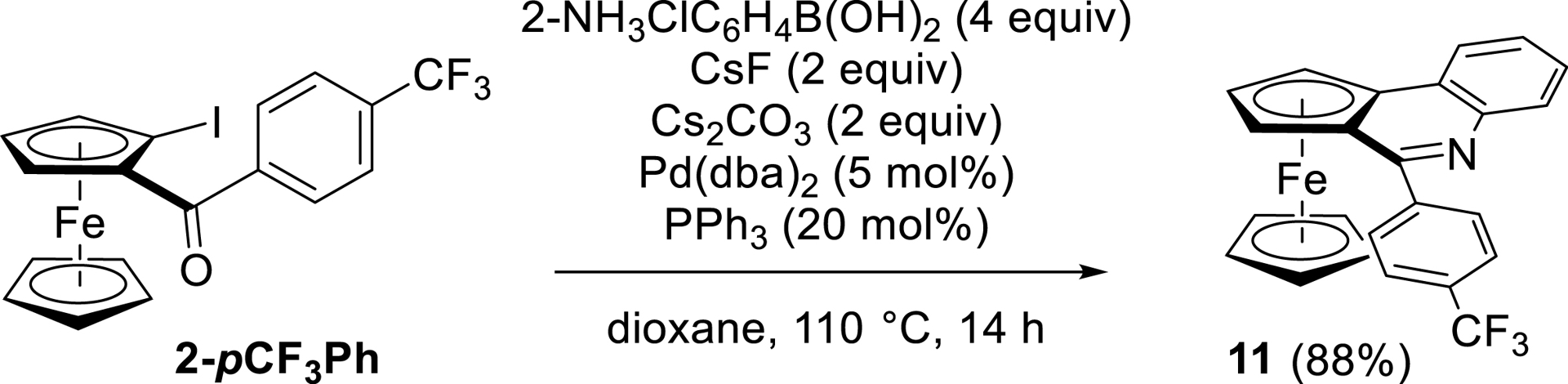

Ferrocene-fused quinoline derivatives are also documented, and notably ferroceno[c]quinolines, which can be synthesized from 2-iodoferrocene carboxaldehyde [116]. As starting from a ketone would provide a substituent in position C-6 of this building block, we were keen to prepare such derivatives from the iodinated ketone 2-pCF3Ph. Inspired by previous results, it was treated with 4 equiv of 2-aminophenylboronic acid, 5 mol% Pd(dba)2, 20 mol% PPh3, and 2 equiv of CsF [107], to which 2 equiv of Cs2CO3 were added for subsequent cyclization in refluxing dioxane. This afforded the original compound 11 in high yield (Scheme 15).

Suzuki–Miyaura cross-coupling from 2-pCF3Ph and subsequent cyclization into ferroceno[c]quinoline.

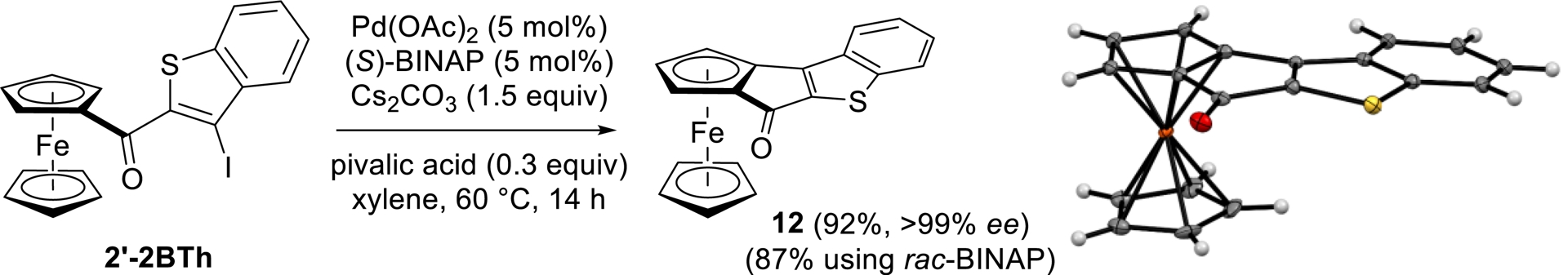

Condensed systems in which the cyclopentadienyl ring of the ferrocene is annulated with a (hetero)aromatic moiety have seen renewed interest with the advent of palladium-catalyzed enantioselective C–H bond activation [114]. Inspired by the synthesis of ferrocene analogues of fluorenone documented by You and coworkers [117], we finally attempted the synthesis of the original thiophene-containing derivative 12 from the iodinated compound 2′-2BTh. To this purpose, our substrate was treated with 5 mol% Pd(OAc)2, 5 mol% (S)-BINAP [BINAP = 2,2′-bis(diphenylphosphino)-1,1′-binaphthyl], 1.5 equiv of Cs2CO3, and 0.3 equiv of pivalic acid in xylene at 60 °C. Pleasingly, the expected tetracyclic compound 13 was isolated in 92% yield and >99% ee, the RP absolute configuration being confirmed by XRD analysis (Scheme 16).

Conversion of 2′-2BTh to the polycyclic compound 12 by CH-functionalization.

2.4. Electrochemical characterization of selected compounds

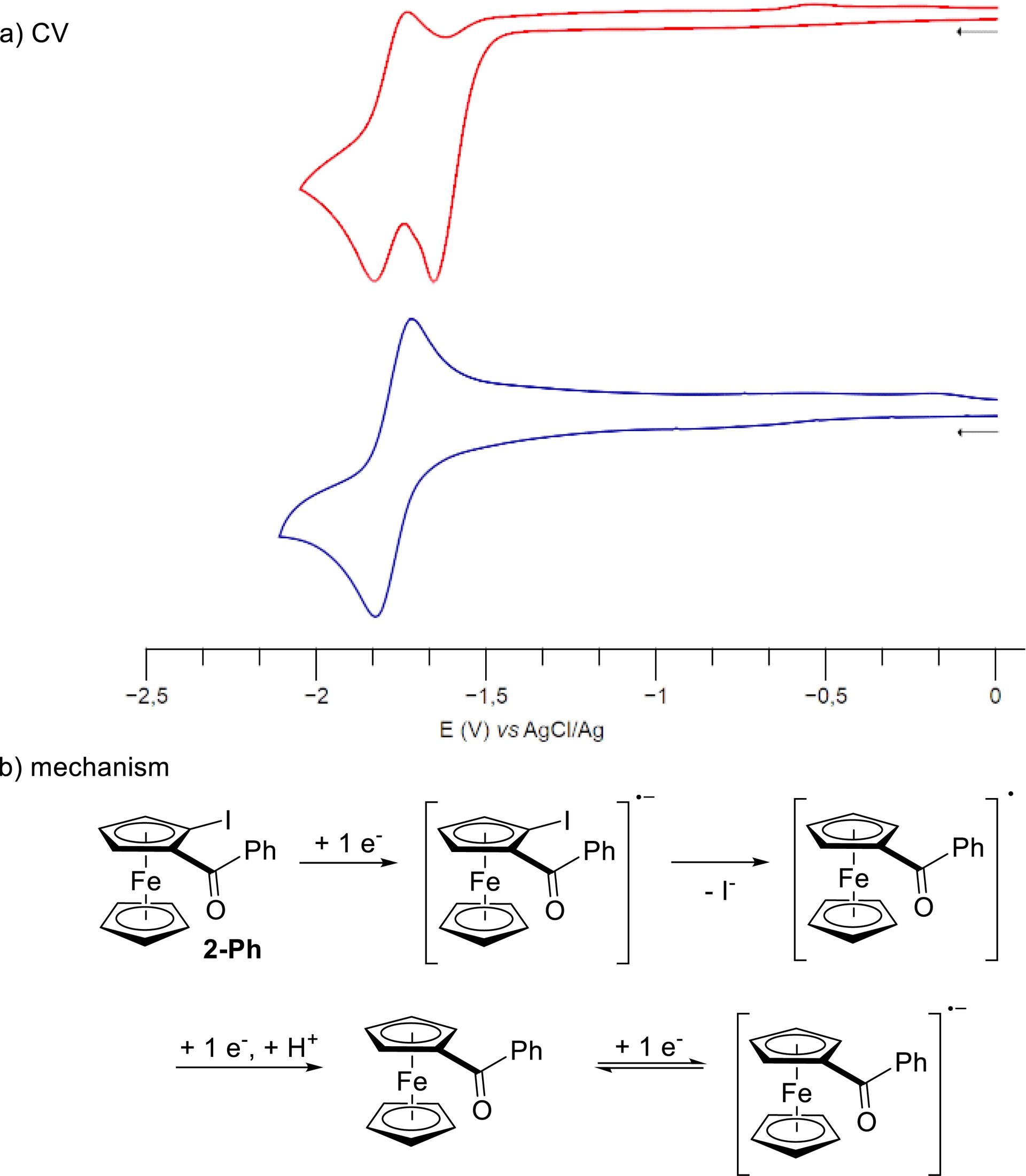

Although ferrocene ketones have been known since the early days of ferrocene history [41], and indeed helped Woodward and his team to coined the name ferrocene [118, 119], they have been scarcely studied from an electrochemical point of view. Kutal et al. reported an in-depth study of the link between the spectroscopic properties and their electronic structure [120], while Gao et al. reported third-order non-linear optical properties of some benzoylferrocenes, supported by DFT calculations [121]. However, electrochemical analyses were not included in these studies. The redox potential of a few ferrocene ketones has been reported from time to time [122, 123, 124], most of the work on benzoylferrocenes coming from the work of Kleinberg et al. [125]. We were therefore interested in investigating the electrochemical properties of some ferrocene ketones prepared during this work, initially focusing our attention on the ketone reduction. Cyclic voltammetry (CV) and differential pulse voltammetry (DPV) were therefore realized in dry, oxygen-free, dimethylformamide, using n-Bu4NPF6 (0.1 M) as the supporting electrolyte with a glassy carbon disk as working electrode, an Ag/AgCl reference electrode, and a glassy carbon rod as counter electrode (Table 1).

Electrochemical data (in V) for the monoelectronic reduction of selected ferrocene ketones

Potential values given relative to Ag/AgCl, scan rate = 100 mV⋅s−1. aFrom CV experiments. bFrom DPV experiments. cA complex reduction process was observed. dAn irreversible dielectronic reduction process was observed.

From benzophenone to 1-Ph, 1-pOMePh, and 1-tBu, the monoelectronic reduction of the ketone, forming the radical anion species, was found reversible and increasingly difficult to achieve, in agreement with the increased electron-donating properties of the group attached to the ketone. Regarding the effect of electron-withdrawing groups, reduction is easier from the 2-pyridyl derivative 1-2Py than from the compounds 1-pCF3Ph and 1-Ph, as one can have expected regarding the electronic properties of these aromatics. We also attempted to push the reduction of 1-pCF3Ph forward to form the corresponding dianion species. However, although we did observe a second reduction in DPV (see Supplementary material), it did not appear to be the expected formation of the dianion species, but rather the reduction of the trifluoromethyl group, as reported by Perichon et al. and Savéant et al. [126, 127]. Due to the inductive effect of iodine, 2-Ph was more easily reduced than benzoylferrocene (1-Ph) by 0.16 V. However, the first dielectronic irreversible process was immediately followed by a second reduction at −1.84 V versus FcH/FcH+, corresponding to that of 1-Ph. We suggest that the initial formation of the radical anion of 2-Ph was followed by the cleavage of the carbon–iodine bond toward the neutral radical 1-Ph∙, which was more easily reduced than the parent compound 2-Ph (Scheme 17). The resulting anion 1-Ph− would then be protonated in situ to generate 1-Ph, which exhibited the expected monoelectronic reduction at −1.84 V. The fused tetracycle 12 was found to undergo an easy and reversible monoelectronic reduction first, followed by two irreversible reduction peaks, which might be attributed to the reduction of the radical anion to the corresponding dianion and to the reduction of the benzothiophene core [128].

(a) Cyclic voltammetry of compounds 2-Ph (red) and 1-Ph (blue). (b) Putative mechanism for the electrochemical conversion of 2-Ph into 1-Ph.

We next investigated the oxidation of the organometallic core for the same compounds but working in dichloromethane this time, in line with our previous studies [92, 129] (Table 2). The redox potential of 1-Ph was measured first, and the 0.25 V value versus FcH/FcH+ was found in good agreement with the results of Herberhold and Jahn, although their measurements were done in acetonitrile instead of dichloromethane [123, 124]. As expected, the redox potential of 1-Ph falls between the ones of 1-pOMePh and 1-pCF3Ph due to their respective electron-donating and electron-withdrawing groups attached to the phenyl ring. The thioketone 4-Ph was more easily oxidized than the parent ketone (E1/2 0.22 versus 0.25 V), probably due to the stronger electron-withdrawing properties of the former [130]. Surprisingly, the redox potential of the pyridyl derivative (1-2Py) was 50 mV lower than that of benzoylferrocene (1-Ph). Indeed, due to the more pronounced electron-withdrawing properties of the pyridine ring, the reverse order was expected. However, electronic repulsion between the lone pairs of the ketone and the pyridine’s nitrogen might promote a conformation similar to the one observed for 2-2Py (see below), avoiding the full transmission of the pyridine’s electronic effect to the ferrocene core. The ferroceno[c]quinolines 11 was found easier to oxidize than any of the ferrocene ketones studied, probably due to the planar structure of the tricyclic core and to the presence of an imine instead of a ketone. In the ferrocene series, it is usually possible to link the E1/2 value of monosubstituted derivatives with the Hammett’s parameter 𝛼p [122, 131, 132] and the E1/2 of polysubstituted compounds with the sum of 𝛼p or 𝛼p +𝛼 m, depending on the substation pattern [133, 134, 135]. Unfortunately, only a limited number of Hammett’s parameters is known for ketones [130]. However, it was still possible to find a correlation between the recorded E1/2 values and the sum of 𝛼p parameters for compounds 1-tBu, 1-Ph, 2-Ph, and 1-CF3 with the equation E1/2 = 1.8466 Σ𝛼p − 0.026 (R2 = 0.9857) (see Supplemtary material).

Electrochemical data (in V) for the oxidation of selected ferrocene ketones

Potential values given relative to FcH/FcH+, scan rate = 100 mV⋅s−1. aFrom CV experiments. bFrom DPV experiments. cIrreversible oxidation was observed.

2.5. Solid-state structures and weak interactions of some ferrocenyl ketones

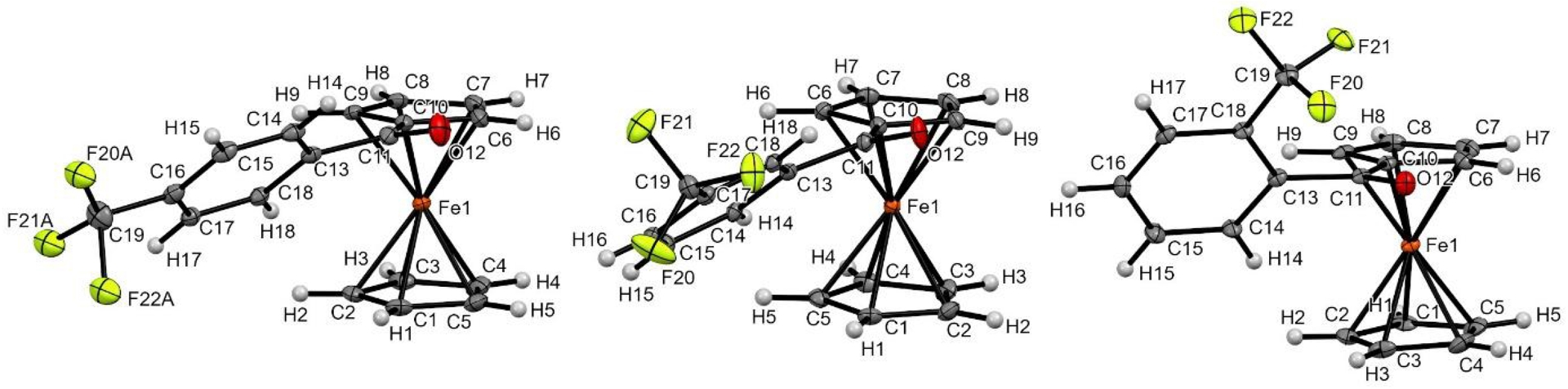

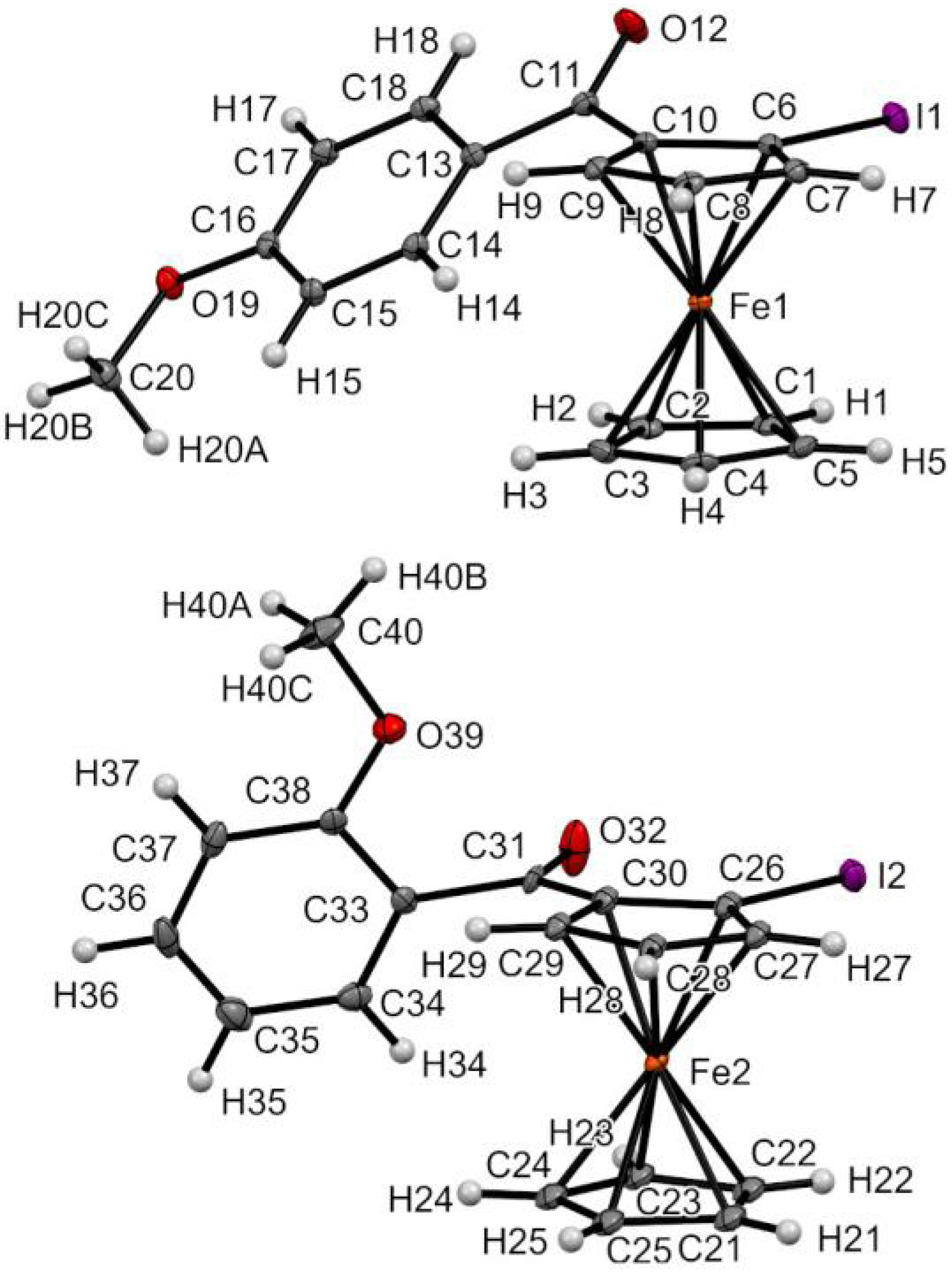

In the frame of this work, many ferrocene ketone derivatives were found to produce crystals suitable for XRD analysis, some of them deserving additional comments. Regarding unsubstituted ferrocene ketones, an eclipsed conformation of the ferrocene core was identified in most cases and the substitution pattern of the phenyl ring was found to have an impact on the solid-state structure. For para- and meta-substituted aromatics, the C=O bond was found tilted above the substituted cyclopentadienyl (Cp) ring while the phenyl ring was slightly inclined compared to the C=O bond. However, for ortho-substituted aromatics, the carbonyl was found aligned with the Cp ring while the aromatic was much more tilted, probably to reduce the steric clash between the carbonyl group and the ortho substituent. The case of the three trifluoromethylated derivatives is especially representative of this general trend (Figure 4).

Molecular structure of compounds 1-pCF3Ph (left), 1-mCF3Ph (middle), and 1-oCF3Ph (right) in the solid state. Thermal ellipsoids shown at the 30% probability level. Selected bond lengths (Å) and angles (°) for 1-pCF3Ph: C10–C11 = 1.469(4), C10–Cg2⋯Cg1–C1 = 4.71 (Cg1 being the centroid of the C1–C2–C3–C4–C5 ring and Cg2 the one of the C6–C7–C8–C9–C10 ring), C6–C10–C11–O12 = 12.9(4), O12–C11–C13–C14 = 27.7(4); for 1-mCF3Ph: C10–C11 = 1.469(3), C10–Cg2⋯Cg1–C1 = 3.19, C9–C10–C11–O12 = 18.0(3), O12–C11–C13–C18 = 20.2(3); for 1-oCF3Ph: C10–C11 = 1.471(8), C10–Cg2⋯Cg1–C3 = 7.58, C6–C10–C11–O12 = 2.5(8), O12–C11–C13–C18 = 53.0(7).

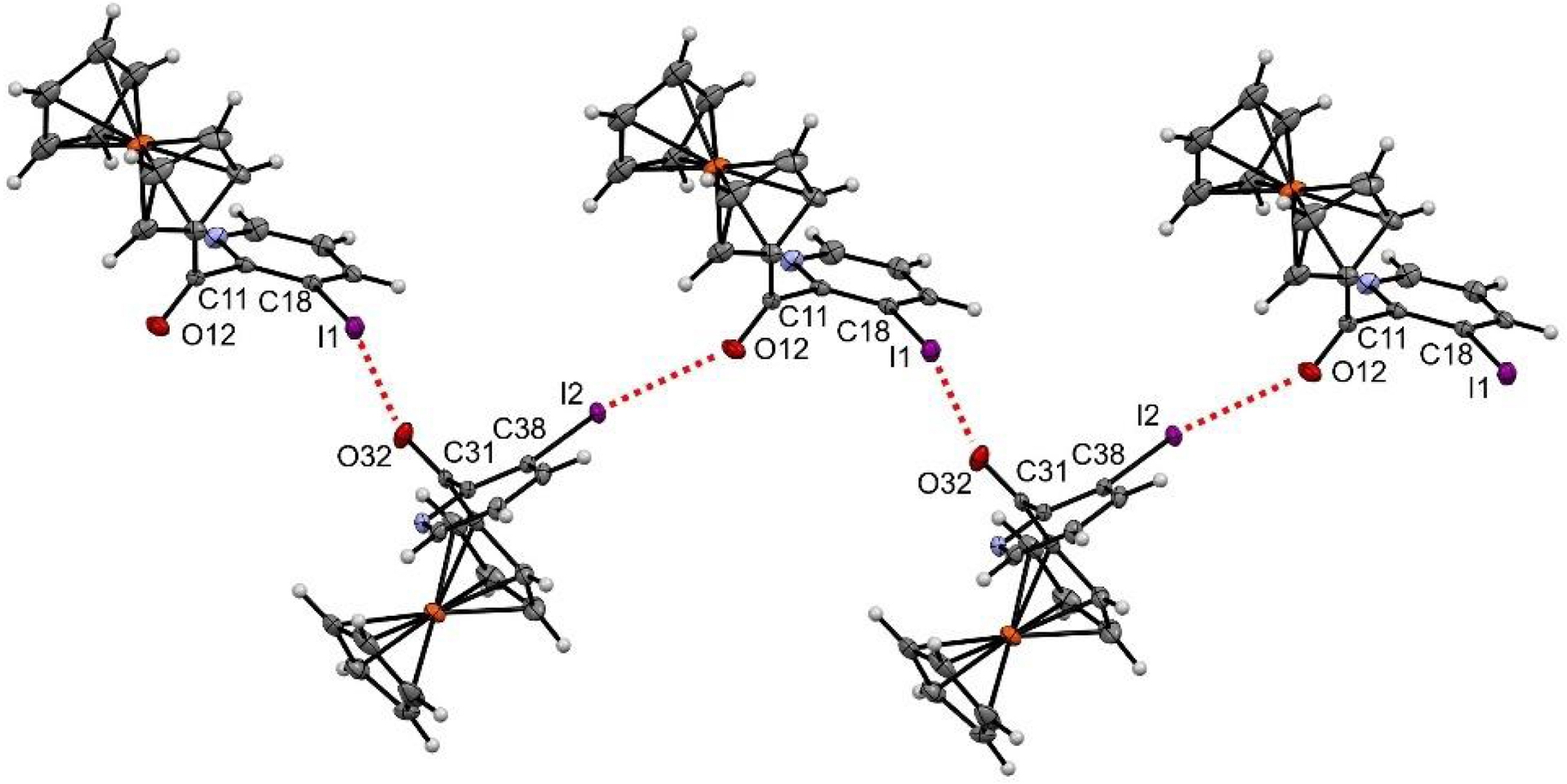

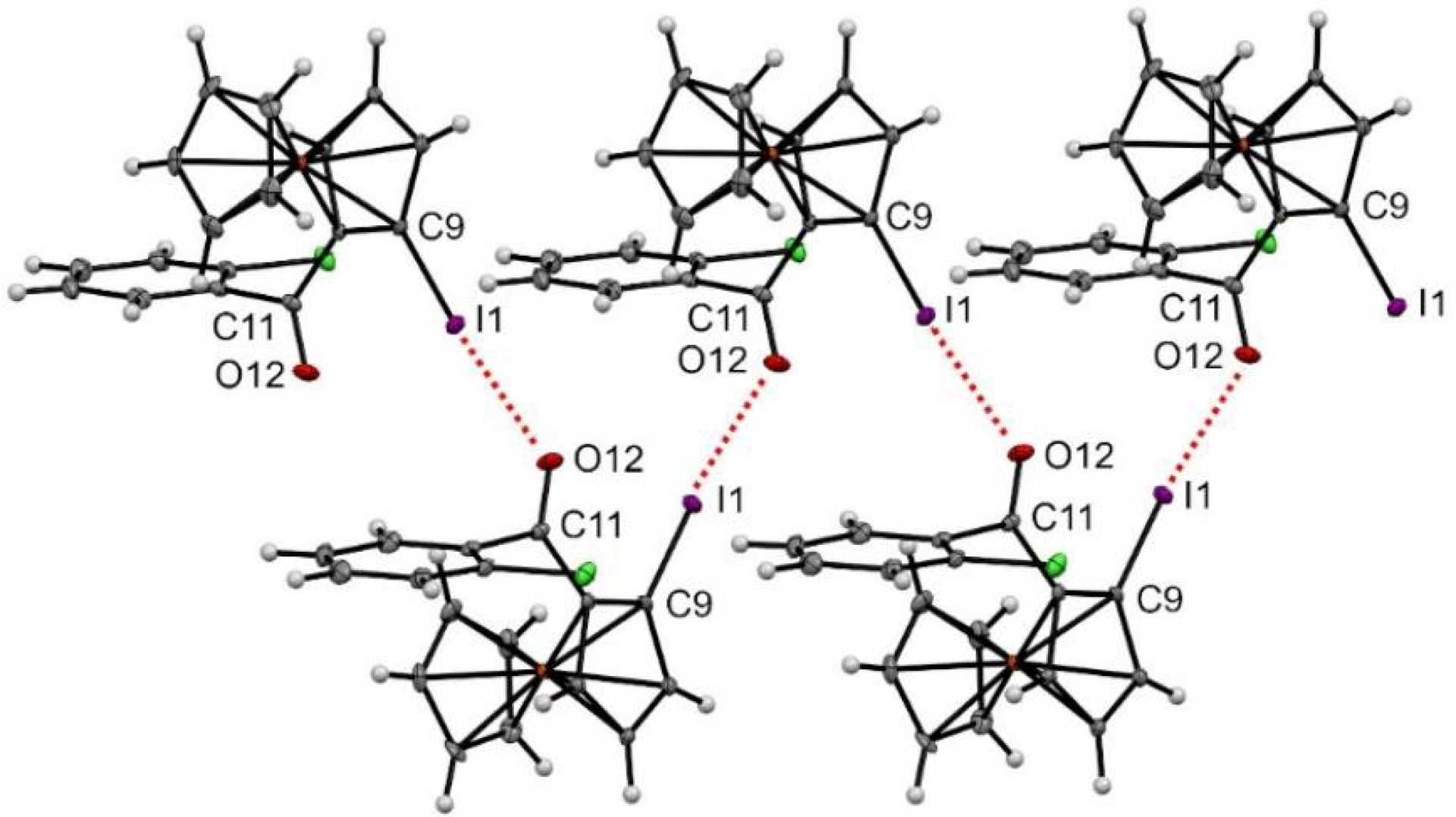

The iodinated derivative 2′-2Py further features an intermolecular halogen–oxygen bond resulting from the interaction between the region of positive electrostatic potential (𝜎-hole) of iodine, acting as the donor, and a lone pair of the oxygen of the ketone, acting as the acceptor [136]. While such interactions are not usually observed with bare iodopyridines, they are more common from iodopyridinium derivatives in which the electron-withdrawing pyridinium ring increases the electrostatic potential of the iodine and thus the strength of the interaction [137, 138]. In 2′-2Py, the ketone adjacent to the iodine atom is expected to have a similar effect, leading to a zigzag halogen-bond network connecting all the molecules in the solid state (Figure 5).

Halogen–oxygen bond observed in the solid state for compound 2′-2Py. Thermal ellipsoids shown at the 30% probability level. Selected bond lengths (Å) and angles (°) O12⋯I2 = 3.051, O32⋯I1 = 3.061, C11–O12⋯I2 147.99, C31–O32⋯I1 146.03, O12⋯I2–C38 156.03, O32⋯I1–C18 160.76.

As expected, the introduction of the iodine next to the ketone induced some structural changes in the solid state, as observed between 1-pCF3Ph and 2-pCF3Ph (Figure 6). Indeed, to accommodate the iodine atom, which was inclined by 4.9° above the Cp ring, the C=O bond was forced to move from its tilted position to be aligned with the Cp ring. A large change in the orientation of the phenyl ring was also observed between the two structures.

Molecular structure of compounds 1-pCF 3Ph (top) and 2-pCF3Ph (bottom) in the solid state. Thermal ellipsoids shown at the 30% probability level. Selected bond lengths (Å) and angles (°) for 2-pCF3Ph: C10–C11 = 1.49(1), C9–I1 = 2.082(7), C10–Cg2⋯Cg1–C2 = 3.35 (Cg1 being the centroid of the C1–C2–C3–C4–C5 ring and Cg2 the one of the C6–C7–C8–C9–C10 ring), Cg2–C9–I1 = 175.11, C9–C10–C11–O12 = −3(1), O12–C11–C13–C14 = −138.0(8).

The substitution pattern of the phenyl ring was also found to influence the solid-state structures of the iodoferrocene ketones. Indeed, except for derivative 2-pCF3Ph, the C=O bond was found tilted from the Cp ring but aligned with the phenyl ring for all the para-substituted derivatives, while the contrary was identified for all the ortho-substituted derivatives, probably for steric encumbrance reasons. The 2-pOMePh and 2-oOMePh structures depicted in Figure 7 nicely illustrate this trend. The opposite behavior of 2-pCF3Ph might be rationalized in terms of substituent effects. Indeed, due to its strong electron-withdrawing inductive effect, the trifluoromethyl group might favor the resonance between the Cp ring of the organometallic and the C=O bond, which therefore need to be aligned. For the other para-substituted aryl derivatives studied, all substituents have a positive mesomeric effect which might override the donating effect of the ferrocene core, explaining why the C=O bond is therefore aligned with the phenyl ring.

Molecular structure of compounds 2-pOMePh (top) and 2-oOMePh (bottom) in the solid state. Thermal ellipsoids shown at the 30% probability level. Selected bond lengths (Å) and angles (°) for 2-pOMePh: C10–C11 = 1.490(3), C6–I1 = 2.089(2), C10–Cg2⋯Cg1–C2 = 3.12 (Cg1 being the centroid of the C1–C2–C3–C4–C5 ring and Cg2 the one of the C6–C7–C8–C9–C10 ring), Cg2–C6–I1 = 178.23, C6–C10–C11–O12 = −33.5(3), O12–C11–C13–C18 = −1.1(3); for 2-pOMePh: C30–C31 = 1.492(7), C26–I2 = 2.096(4), C30–Cg4⋯Cg3–C23 = 22.47 (Cg3 being the centroid of the C21–C22–C23–C24–C25 ring and Cg4 the one of the C26–C27–C28–C29–C30 ring), Cg4–C26–I2 = 176.92, C26–C30–C31–O32 = −10.1(8), O32–C31–C33–C38 = −105.7(7).

From racemic 2-oClPh, preferential crystallization of the enantiopure SP enantiomer was pleasingly observed [139], allowing us to identify the formation of a halogen–oxygen bond in the solid state (Figure 8). Due to the electron-richness of the organometallic core, iodoferrocenes are usually not able to develop such interactions. However, the presence of electron-withdrawing substituents can substantially increase the positive electrostatic potential of iodine’s 𝜎-hole. As a result, halogen bond networks have been recently identified for various iodoferrocenes substituted with sulfonamides [140], sulfonates [92], sulfoxides [141], sulfonyl fluoride [134], and triflones [87]. Similar bonds were also observed for ferrocene iodoalkyne derivatives [142]. In the case of Sp-2-oClPh, having the iodine and the ketone groups in a same plane and pointing in the same direction led to a zigzag chain of halogen–oxygen bonds with bonds lengths and angles being in the range of classical values [136].

Halogen–oxygen bonds observed in the solid state for compound SP-2-oClPh. Thermal ellipsoids shown at the 30% probability level. Selected bond lengths (Å) and angles (°) O12⋯I1 = 2.999, C11–O12⋯I1 139.63, O12⋯I1–C9 173.64.

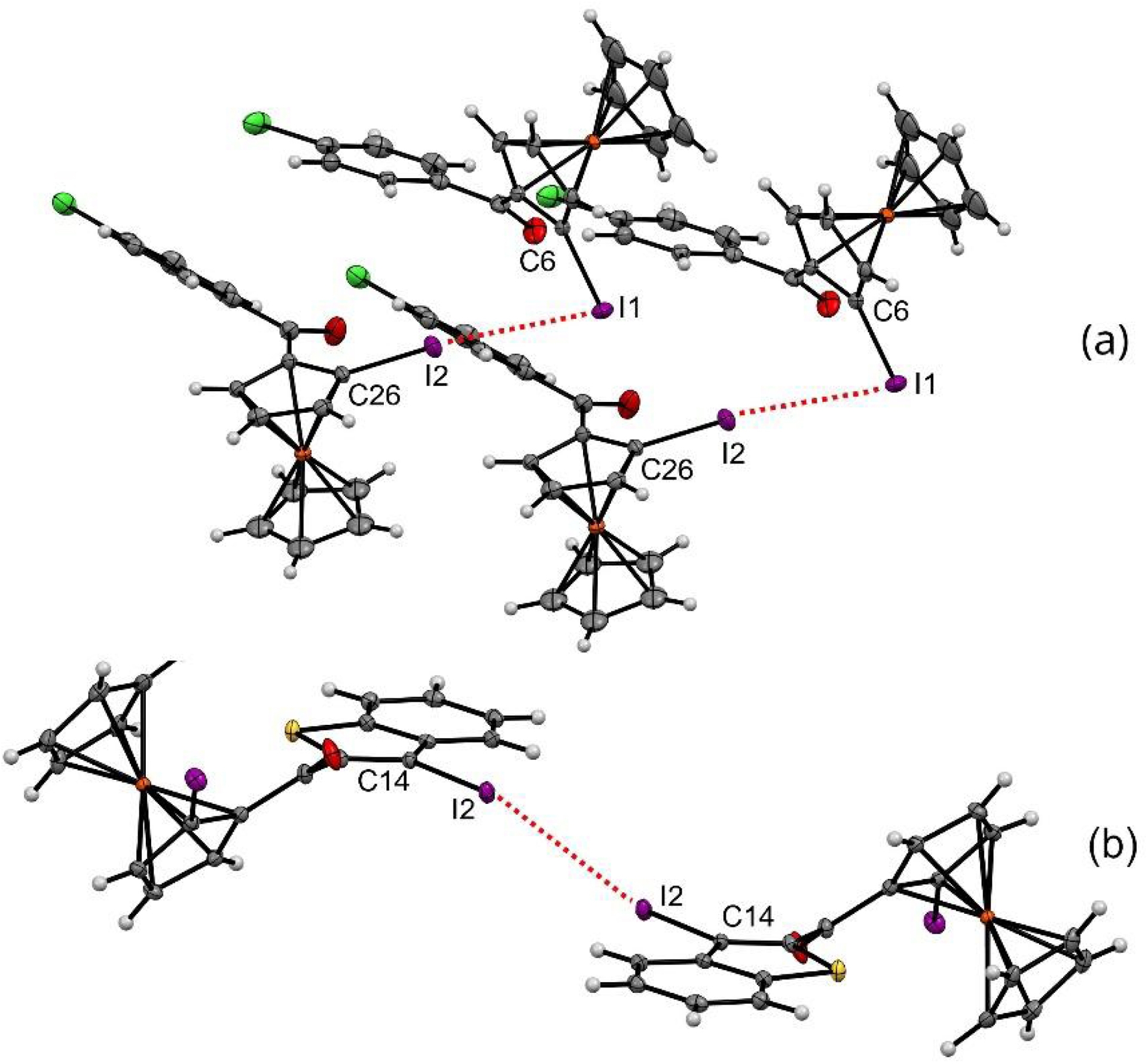

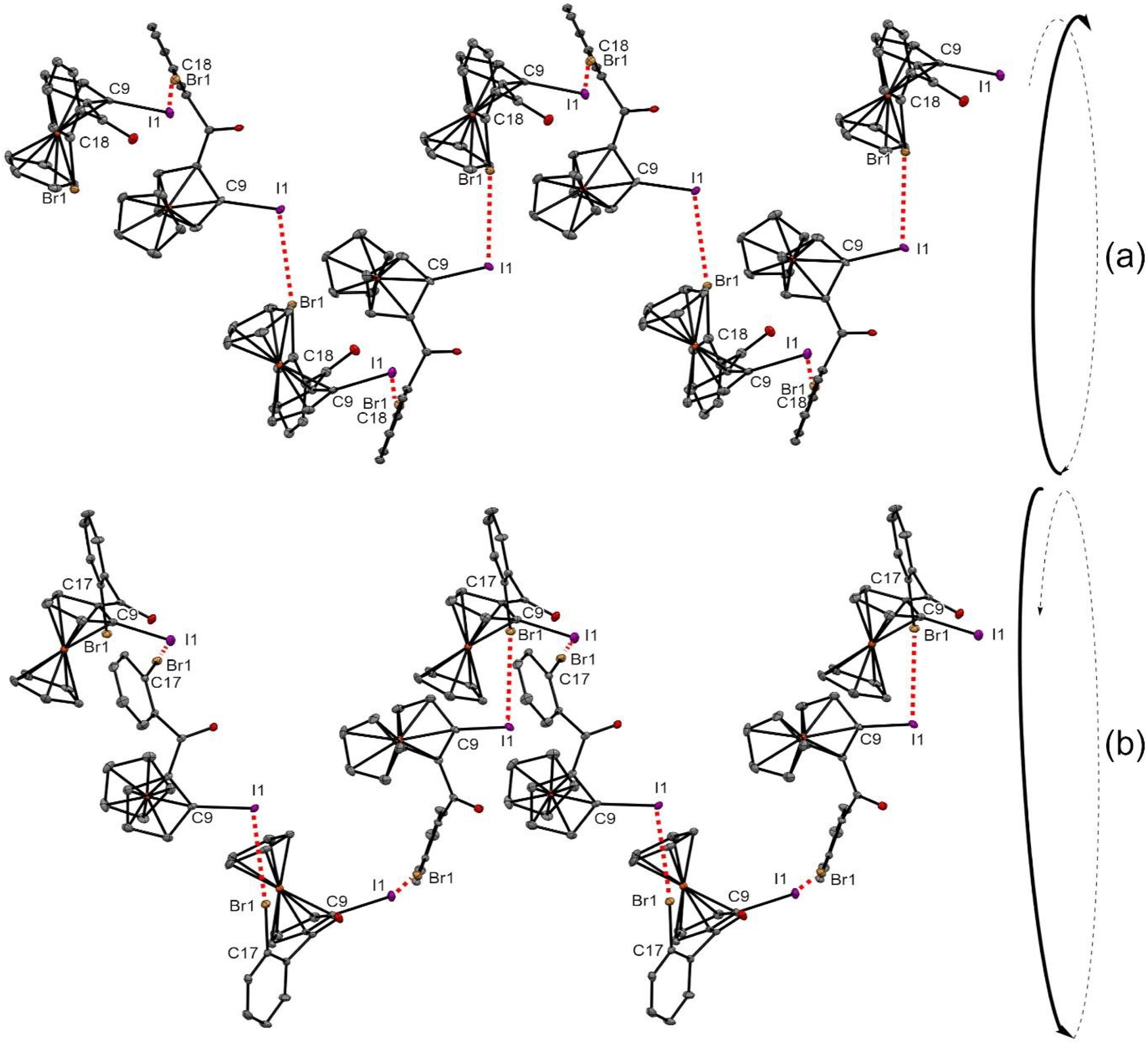

We were pleased to identify the two types of halogen–halogen interactions in three of our iodoferrocene ketones [143, 144]. In the solid state, both enantiomers of 2-pClPh were identified in the crystal structure, with the RP enantiomer interacting with the SP enantiomer via a type II iodine–iodine interaction, characterized by two different C–I⋯I angle values (Figure 9a). However, while the two enantiomers of 2′′-2BTh crystallized together in a similar manner, a type I iodine–iodine interaction with similar C–I⋯Iangles was observed between the iodine atoms attached to the benzothiophene moiety and not between those linked to the ferrocene core (Figure 9b).

Iodine–iodine interaction network observed in the solid state for compounds 2-pClPh (top) and 2′′-2BTh (bottom). Thermal ellipsoids shown at the 30% probability level. Selected bond lengths (Å) and angles (°) for 2-pClPh: I1⋯I2 = 3.882, I1⋯I2–C26 173.07, C6–I1⋯I2 73.43; for 2-pClPh: I2⋯I2 = 3.772, I2⋯I2–C14 137.38, C14–I2⋯I2 137.38.

From racemic 2-oBrPh, spontaneous resolution was observed and the two enantiomers were separately isolated as conglomerates. As expected, single molecules of each enantiomer were almost similar in the solid state, both crystallizing in the same tetragonal system, although in different space groups. However, the most interesting characteristics were observed having a closer look at intermolecular halogen–halogen bonds for each enantiomer. Indeed, the bromine of one molecule was found to develop a type I interaction with the iodine atom of another molecule, leading to the helix arrangement of all molecules. While ferrocene derivatives have previously been involved in the formation of such structures [145, 146, 147, 148], the involvement of halogen–halogen interactions to structure the arrangement is pretty unusual. The planar chirality of the ferrocene core was further found to influence the axial chirality of the helix, the RP enantiomer giving rise to a M helix (Figure 10a), while a P helix was observed for the SP enantiomer (Figure 10b).

Iodine–bromine bond network observed in the solid state for compounds RP-2-oBrPh (a) and SP-2-oBrPh (b) and sense of the helix formed. Thermal ellipsoids shown at the 30% probability level; hydrogen atoms omitted for clarity. Selected bond lengths (Å) and angles (°) for RP-2-oBrPh: Br1⋯I1 = 3.594, C18–Br1⋯I1 171.16, C9–I1⋯Br1 98.79; for SP-2-oBrPh: Br1⋯I1 = 3.599, C17–Br1⋯I1 170.96, C9–I1⋯Br1 99.35.

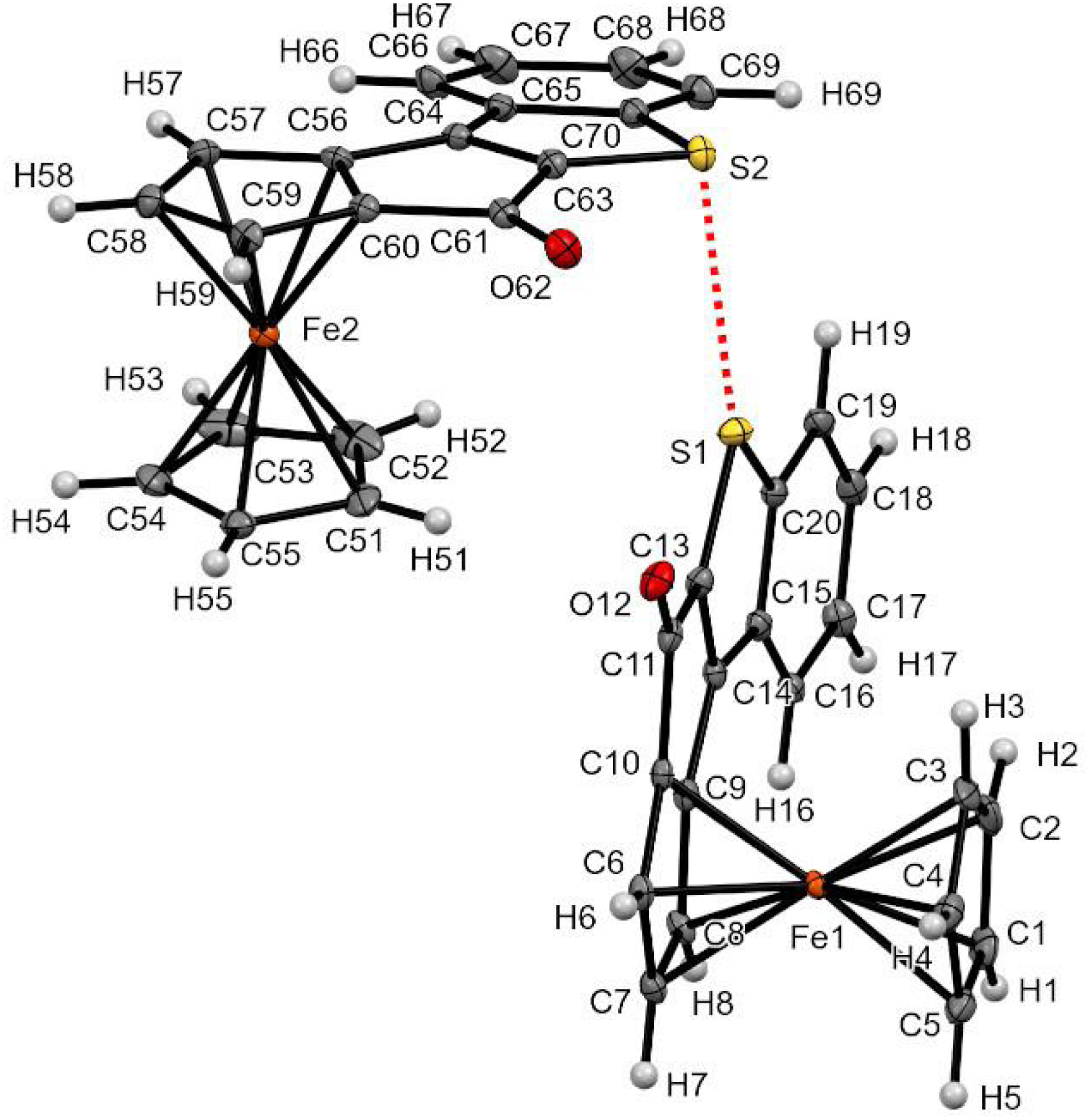

It was finally possible to grow crystals of the enantiopure tetracycle 12 suitable for XRD analysis (Figure 11). Not only the solid-state structure validated the expected RP configuration of the compound but it also allowed the identification of chalcogen–chalcogen interactions [149, 150]. Indeed, a sulfur⋯sulfur interaction between two molecules was likely to happen due to the S1⋯S2 distance below the van der Waals radii (3.54 versus 3.60 Å) [151], although the various C–S⋯S angles are shorter than expected, probably due to the rigid fused-thiophene unit. The tetracyclic systems of the two molecules composing the dimer were found perpendicular and, although this arrangement is not usual, it was previously identified in other benzothiophene derivatives [152].

Chalcogen–chalcogen bond observed in the solid state for compound RP-12. Thermal ellipsoids shown at the 30% probability level. Selected bond lengths (Å) and angles (°): S1⋯S2 = 3.547, C13–S1⋯S2 124.90, C20–S1⋯S2 144.94, C63–S2⋯S1 105.11, C70–S2⋯S1 76.54, angle plane (C9–C8–C7–C6–C10–C11–C13–S1–C20–C19–C18–C17–C16–C15–C14)-(C56–C57–C58–C59–C60–C61–C63–S2–C70–C69–C68–C67–C66–C65–C64) 89.24.

3. Conclusion

Here we have presented the first in-depth study of the deprotolithiation of ferrocene ketones using a bulky, non-nucleophilic lithium amide, as well as an in-situ trap to prevent nucleophilic attack of the function by the ferrocenyllithium formed. The expected iodoferrocene derivatives were obtained in most cases although the presence of electron-acceptor substituents on the aryl moiety was found to reroute the functionalization on this cycle, in agreement with our DFT calculations (pKa values after coordination to lithium).

The development of an enantioselective version of the reaction was next attempted using a chiral lithium amide. Although our best ee did not exceed 60%, the feasibility of this approach was demonstrated. Finally, we took advantage of the installation of the iodine on the (hetero)aryl ring to reach original ferrocene-fused heterocycles, including a tetracycle obtained by enantioselective C–H functionalization.

Given the significant potential of both ferrocene ketones [65] and ferrocene-fused heterocycles [153], the current study is expected to pave the way for future work toward such compounds to promote their application in various fields.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge BASF (generous gift of di[(S)-1-phenylethyl]amine and di[(R)-1-phenylethyl]amine) and Thermofisher (generous gift of 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine). We acknowledge Olivier Perez, Carmelo Prestipino and Jean-François Lohier (CRISMAT, UMR CNRS 6508) and well as Magali Allain (Moltech-Anjou, UMR CNRS 6200) for their help in X-ray data collection.

Declaration of interests

The authors do not work for, advise, own shares in, or receive funds from any organization that could benefit from this article, and have declared no affiliations other than their research organizations.

Funding

This work was supported by the Direction Générale de la Recherche Scientifique et du Développement Technologique (MH), Rennes Métropole (WE), the University of Carthage and the Tunisian Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research (SB), the Fonds Européen de Développement Régional (FEDER; D8 VENTURE Bruker AXS diffractometer), the Université de Rennes and the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (WE, J-PH, MB, TR, FM).

Supplementary materials

The CCDC files 2490197 (1-oOMePh), 2490198 (1-pClPh), 2490199 (1-mBrPh), 2490200 (1-oCF3Ph), 2490201 (1-mCF3Ph), 2490202 (1-pCF3Ph), 2490203 (1-oFPh), 2490204 (1-2BTh), 2490205 (1-C≡CPh), 2490206 [RP-2-Ph], 2490207 (2-oOMePh), 2490208 (2-pOMePh), 2490209 (2-oClPh), 2490210 (2-pClPh), 2490211 [RP-2-oBrPh], 2490212 [SP-2-oBrPh], 2490213 (2-pBrPh), 2490214 (2-pCF3Ph), 2490215 (2′-2Py), 2490216 (2′-2BTh), 2490217 (2′′-2BTh) and 2490218 (12) contain the supplementary crystallographic data. These data can be obtained free of charge from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures.

CC-BY 4.0

CC-BY 4.0