1 Introduction and previous studies

It is widely shared the interpretation which considers the Maghrebian Chain, from Rif to Sicily, as made up by the stacking of nappes originated from three main domains, located from north to south: the Internal, Flysch Basin and External Domains (Durand-Delga, 1980; Guerrera et al., 1993; Wildi, 1983).

The timing of the deformation of the Internal and Flysch Basin Domains has been recently well constrained for the Sicilian sector of the chain, where the youngest preorogenic deposits of the Internal and Flysch Basin nappes, and the oldest up-thrust deposits sealing the tectonic contacts between these nappes, have been dated with acceptable precision (Bonardi et al., 2002; Bonardi et al., 2003; de Capoa et al., 1997; de Capoa et al., 2000; de Capoa et al., 2002; de Capoa et al., 2004). The deformation of the Internal Domain resulted to be Early Miocene, whereas that of the Flysch Basin accounted near to the Burdigalian-Langhian boundary in the internal zone of the basin, and near to the Langhian-Serravallian boundary in its external zone. The deformation age of the External Domain, on the contrary, has never been accurately verified, and several ages, some of them clearly mistaken, are still proposed in the geological literature of Sicily.

In the Tellian Maghrebids, the biostratigraphy of both preorogenic and up-thrust deposits needs to be updated. However, the available data on the Internal and Flysch Basin Domains seem to be coherent with those of the Sicilian sector (Durand-Delga, 1980).

In the Rifian Maghrebids and in the western Betics, whose structural homologies have been evidenced many years ago (Didon et al., 1973), the deformation of the Internal Domain is exactly constrained, because of the reconnaissance of the Viñuela Group and Sidi Abdeslam Fm unconformably resting on the Internal Units of the Betic Cordillera and Rifian Maghrebids, respectively (Ben Yaich et al., 1986; Feinberg et al., 1996; Martín-Algarra, 1987). As to the deformation age of the Flysch Basin, in the Betic Cordillera Middle Miocene post-nappe clastic deposits are known (Chauve, 1968; Martín-Algarra, 1987). In the Rifian Maghrebids (Fig. 1A), on the contrary, the oldest sediments sealing the Flysch Basin Units are Pliocene in age. Therefore, one can only affirm that the deformation of the Flysch Domain is not older than Burdigalian, age of the youngest deposits recognized in the Flysch Basin successions (de Capoa et al., 2007; Zaghloul et al., 2007). However, useful data to better constrain the deformation of the Flysch Basin have been obtained considering the age of detritic deposits, unconformable on units originated from the External Domain, in which clasts, fed by the Flysch Basin Units, have been pointed out. This is the case of the Beni Issef Miocene successions, sealing the contact between the External Tanger and Loukkos Units, located nearly 30 km west of Chefchaouen (Fig. 1B). Both Intrarifian Units represent the most internal part of the External Domain. Their sediments were deposited in the northernmost zone of the African margin, close to the Flysch Basin, and their sedimentary and tectonic history is unclear due to the scarcity of Oligocene and Miocene layers at the top of the stratigraphic successions (Durand-Delga et al., 1985, see later).

A. Geological sketch map of the Rif Chain, simplified after (Boccaletti et al., 1985; Suter, 1980; Wildi, 1983). Box indicates the location of B. B. Geological map of the Beni Issef Massif: 1: Pliocene-Quaternary deposits; 2: Upper Beni Issef Fm: medium-thick sandstone beds, conglomerates and pebbly sandstones alternating with mudrocks; 3: Lower Beni Issef Fm: medium-thin-bedded sandstones alternating with marls and mudrocks; 4: Lower Beni Issef Fm: transgressive conglomerates; 5: External Tanger Unit (Upper Cretaceous-Serravallian); 6: Loukkos Unit (Lower Cretaceous-Eocene); 7: unconformity at the base of the Lower Beni Issef Fm; 8: unconformity at the base of the Upper Beni Issef Fm; 9: fault; 10: normal bed; 11: reverse bed; 12: section of Fig. 3.

A. Schéma géologique de la Chaîne Rifaine, simplifié d’après (Boccaletti et al., 1985 ; Suter, 1980 ; Wildi, 1983). Le petit carré indique la localisation de B. B. Carte géologique du Massif des Beni Issef : 1 : dépôts du Pliocène-Quaternaire ; 2 : Formation Supérieure des Beni Issef : grès et conglomérats alternant avec marnes et argiles ; 3 : Formation Inférieure des Beni Issef : grès alternant avec marnes et argiles ; 4 : Formation Inférieure des Beni Issef : conglomérats ; 5 : Unité de Tanger Externe (Crétacé supérieur-Serravallien) ; 6 : Unité du Loukkos (Crétacé Inférieur-Eocène) ; 7 : discordance à la base de la Formation Inférieure des Beni Issef ; 8 : discordance à la base de la Formation Supérieure des Beni Issef ; 9 : faille ; 10 : stratification ; 11 : stratification renversée ; 12 : coupe de la Fig. 3.

The “Miocène des Beni Issef” was firstly described by Durand-Delga and Lespinasse (1965), who pointed out the occurrence in the conglomerate layers of most pebbles fed by the Flysch Basin Units, in particular quartzarenites from the Numidian succession, as well as Cretaceous-lower Eocene calcareous clasts coming from the Tanger Unit and probably also from the “Chaîne Calcaire” Internal Units. The authors recognized faunas, represented by gastropods (Turritella and Protoma) and bivalves (Crassostrea and Clausinella), qui caractérisent un niveau élevé du Miocène, qu’on le qualifie d’“Helvétien” ou de “Tortonien”, so testifying for a deformation of both the entire Flysch Basin and the Intrarifian Zone before the “Helvetian” or Tortonian. The succession, intensively folded, is interpreted as a post-nappe deposit, deformed during the successive tectogenetic phases which affected the External Domain.

Later, the “Miocène des Beni Issef” was studied by Didon and Feinberg (1979), who also interpreted it as a post-nappe deposit, resting on Senonian marls of the Tanger and Loukkos Units. The authors clearly distinguished two successions, separated by an unconformity, interpreted as an intraformational unconformity. The lower succession consists of sandy marls with Turritella and, in the lower part, of conglomerates and boulders, fed by the Flysch Basin nappes. Foraminifera testify, for the base of the lower succession, a Latest Burdigalian age (Gd. trilobus; Gd. bisphericus; D. altispira; Zone N7). The bulk of the sandy marls was considered to be essentially Langhian, due to the occurrence of P. glomerosa, P. transitoria, O. suturalis, O. universa and P. mayeri; Zones N8-N9). Nannofossils (D. variabilis and R. pseudoumbilicus) indicate the same interval (Zones NN3-NN5). The upper succession is made up mainly of conglomerates with, interbedded, some layers of siltstones, sandy marls and clays. Also for this succession, rare planktonic fossils would indicate a Langhian age. Consequently, the Beni Issef succession is essentially Langhian and the deformation of both the Flysch Basin and the Intrarifian Zone would be not younger than the Latest Burdigalian. These results were quite similar to those obtained by Feinberg and Leblanc (1977) in the area northeast of Taza, where the authors recognized the Langhian-Serravallian Jebel Binet Fm, sealing the Aknoul and Bou Haddoud Intrarifian Nappes, and a Tortonian succession, at Jebel Tizeroutine, unconformable also on the Prerifian Units. So, Latest Burdigalian and Tortonian tectonic phases were responsible for the deformation of the Intrarifian and Prerifian Zones, respectively.

This reconstruction was questioned by Septfontaine (1983), who recognized a Late Tortonian-Messinian age for the Jebel Binet Fm. The author, therefore, evidenced that the Burdigalian age of the deformation of the Intrarifian zone was not supported by the age of the Jebel Binet Fm, and pointed out for the necessity of a revision also of the age of the Beni Issef succession. Later, Zaghloul et al. (2005) demonstrated that the uppermost beds of the External Tanger Unit reach the Late Serravallian, but did not consider the importance of this age for the reconstruction of the tectonic evolution of the Intrarifian Zone. These data would imply an age of deformation younger than the Late Burdigalian for the Intrarifian Zone and an age not older than Late Serravallian for the base of the Beni Issef succession.

In this study, the “post-nappes” Beni Issef successions have been re-examined by means of structural, sedimentologic, petrographic and biostratigraphic analyses. In particular, the successions have been sampled for biostratigraphic studies through calcareous nannofossils, using new techniques and considering the progress within this field of research. The aim is to obtain more data about features, age and evolution of the “Miocène des Beni Issef” and to integrate these terrains in the regional geodynamic context, in order to better reconstruct the Neogene evolution of the Rif in the frame of whole of the Maghrebian Chain.

2 Geological setting and lithostratigraphy

The “Miocène des Beni Issef” crops out in the homonymous massif, high up to 875 m (topographic map of Morocco, sheet 1/50,000 Khemis El Kolla; Fig. 1B). It represents fairly the most developed post-nappe succession within the Rif chain, reaching a total thickness of about 700 m. The Beni Issef outcrop is bounded some kilometres eastward and westward by higher crests of Numidian Flysch, bearing at its base some slices of Lower Cretaceous green-bottle marls and fine-grained mature turbiditic quartzarenites belonging to the Massylian Flysch of the Melloussa Nappe (Fig. 1A). Some small and scattered outcrops, referable to more internal Flysch Basin nappes (Beni Ider Nappe), are also present (Durand-Delga and Lespinasse, 1965).

The cartographic review at scale 1/20,000 confirms some conclusions of previous studies (Didon and Feinberg, 1979; Durand-Delga and Lespinasse, 1965). In particular (Fig. 1B):

- • the Miocene deposits rest on both Middle-Upper Senonian grey-brown or blackish marls, with abundant nodules of limestones, and greyish-greenish clays, belonging to the External Tanger and Loukkos Units, respectively;

- • the angular unconformity, separating two different successions, is clearly visible in the field. This unconformity was already evidenced by Didon and Feinberg (1979) and interpreted as an intraformational unconformity. Taking also into account the structural and biostratigraphic data (see later), actually this unconformity separates two different formations, that hereafter we will denominate Lower Beni Issef and Upper Beni Issef Fms.

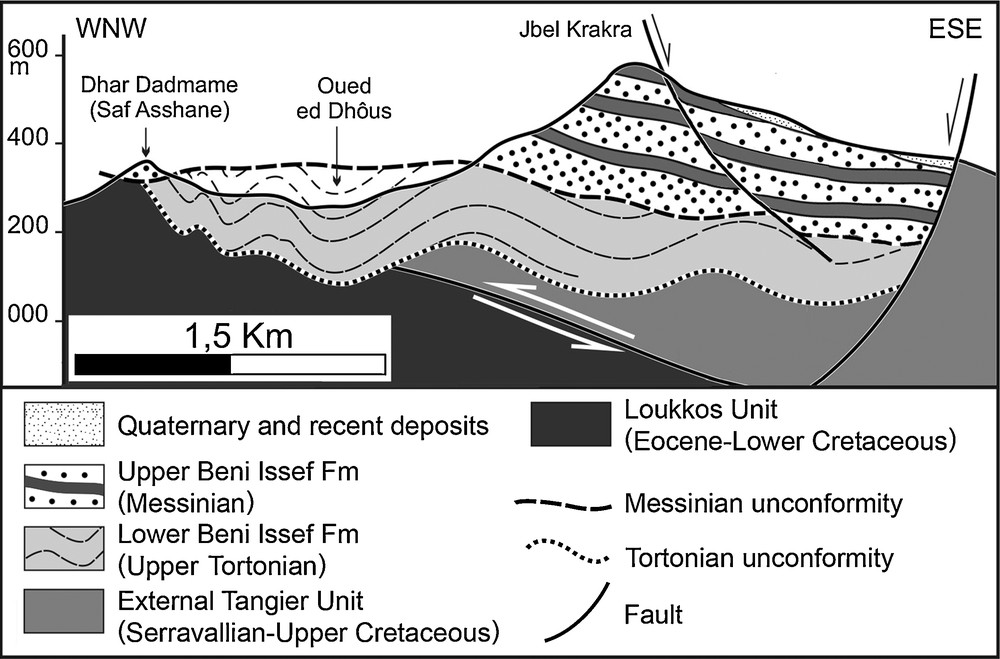

The stratigraphic contact between the Lower Beni Issef Fm and the Intrarifian substratum is frequently covered by Quaternary deposits, but in many places a clear angular unconformity can be pointed out. Moreover, the coarse- to very coarse-grained lithofacies, characterizing the base of the Upper Beni Issef Fm, can be observed directly on the Intrarifian substratum (Fig. 2A). This contact was firstly recognized and described by Didon and Feinberg (1979) at Dhar Dedmame (Figs. 1B and 3), where sandy-gravelly conglomerates of the Upper Beni Issef Fm, dipping northward (50°–60°/350°–360°), rest on both the Middle-Upper Senonian marls of the Loukkos Unit and the Miocene marls with thin siltstone beds, dipping 50° westward, of the Lower Beni Issef Fm (Fig. 3). However, the unconformity between the Upper and Lower Beni Issef Formations is less marked elsewhere and in some outcrops the contact is paraconformable (Figs. 1B, 2B and 3).

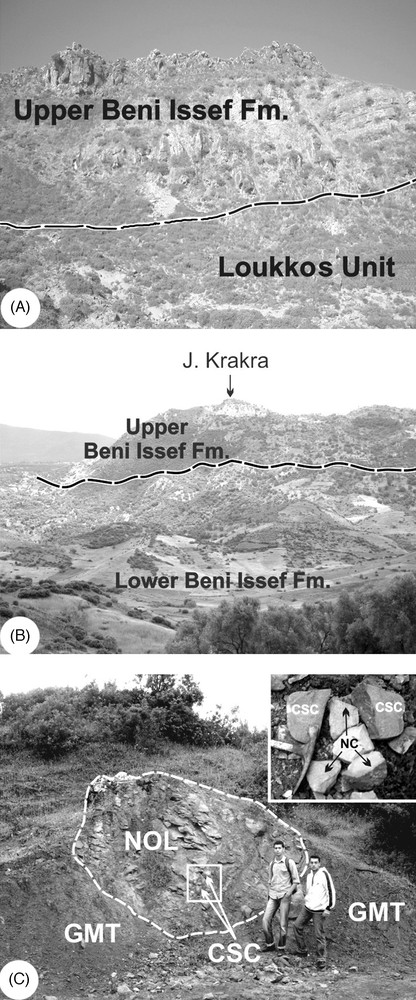

A. Panoramic view of the Messinian unconformity between the coarse- and medium-grained lithofacies of the Upper Beni Issef Fm and the Cretaceous claystones of the Loukkos Unit (southward of Tlata Beni Issef). B. Panoramic view of the Messinian unconformity between the medium-coarse-grained lithofacies of the Upper Beni Issef Fm and the fine-grained lithofacies of the Lower Beni Issef Fm (western versant of Jebel Krakra). C. Boulder of Numidian sandstones (NOL) and cobble clasts of calcareous sandstones (CSC) and Numidian sandstones (NC), all resedimented within grey marls (GMT) of the Lower Beni Issef Fm (south of Saf Asshane).

A. Vue panoramique de la discordance messinienne entre les lithofaciès grossiers de la Formation Supérieure des Beni Issef et les argilites crétacées de l’Unité du Loukkos au sud de Tlata Beni Issef. B. Vue panoramique de la discordance messinienne entre les lithofaciès grossiers de la Formation Supérieure des Beni Issef et les marnes et grès fins de la Formation Inférieure des Beni Issef (versant occidental du Jebel Krakra). C. Boulder de grès numidiens (NOL) et galets de grès calcaires (CSC) et de grès numidiens (NC), tous resédimentés dans les marnes grises (GMT) de la Formation Inférieure des Beni Issef, au sud de Saf Asshane.

Schematic geological cross-section of the Beni Issef Massif.

Coupe géologique schématique du Massif des Beni Issef.

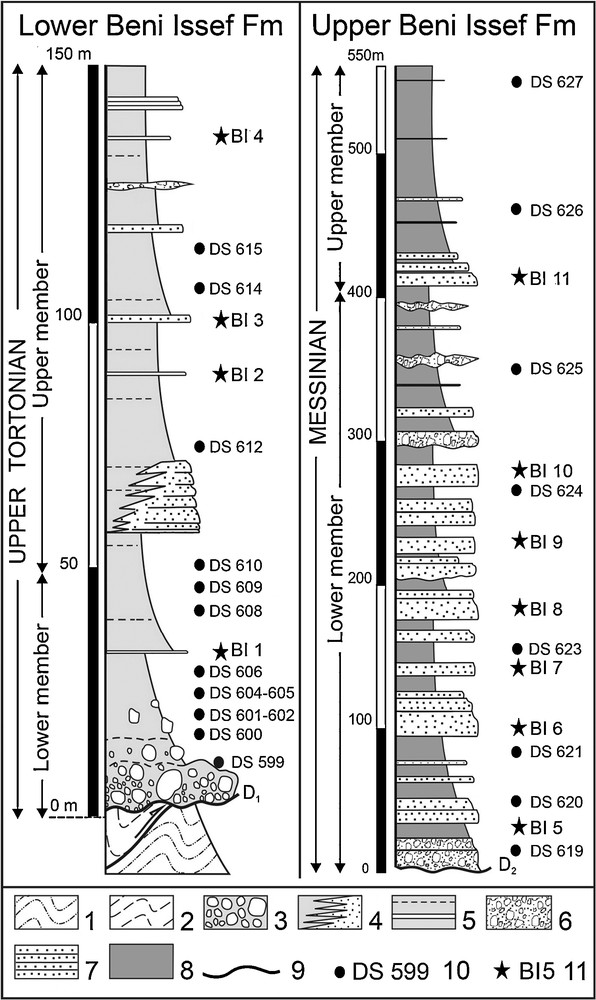

The Lower Beni Issef Fm, 150 m thick, crops out in the topographic depression straight below the sandy-conglomeratic relieves of the Beni Issef Massif, and drained by the Oued ed Dhoûs and its tributaries (Fig. 1B). In the succession (Fig. 4), it is possible to recognize a lower member, nearly 55 m thick, which starts with lenses and layers of coarse conglomerates (debris flows) and huge marl, limestone and quartzarenite blocks in a yellow and grey marly-clayey matrix. This basal conglomerate, deriving from different units of the Flysch Basin and Intrarifian nappes (Fig. 2C), is followed by marls with a few of sandy-gravelly conglomerates and thin-bedded sandstones.

Synthetic stratigraphic section of the Lower and Upper Beni Issef Formations. 1: Loukkos Unit; 2: External Tanger Unit; 3: Lower Beni Issef Fm: conglomerate and basal conglomerate; 4: Lower Beni Issef Fm: amalgamated thick sandstone beds passing laterally to greyish mudrock; 5: Lower Beni Issef Fm: greyish mudrock with thin-bedded sandstone; 6: Upper Beni Issef Fm: conglomerate and pebbly sandstone; 7: Upper Beni Issef Fm: medium- to thick-bedded sandstone; 8: Upper Beni Issef Fm: greyish mudrock and marl with thin-bedded sandstone; 9: unconformity at the base of the Lower Beni Issef Fm (D1) and at the base of the Upper Beni Issef Fm (D2); 10: fossiliferous sample; 11: petrographic sample.

Coupes stratigraphiques synthétiques de la Formation Inférieure et de la Formation Supérieure des Beni Issef. 1 : Unité du Loukkos ; 2 : Unité de Tanger Externe ; 3 : Formation Inférieure des Beni Issef : conglomérats et conglomérat basal ; 4 : Formation Inférieure des Beni Issef : grès en couches épaisses et amalgamées, passant latéralement à argiles grises ; 5 : Formation Inférieure des Beni Issef : argiles grises avec couches minces de grès ; 6 : Formation Supérieure des Beni Issef : conglomérats et grès conglomératiques ; 7 : Formation Supérieure des Beni Issef : grès en couches moyennes à épaisses ; 8 : Formation Supérieure des Beni Issef : argiles grises et marnes avec grès en couches minces ; 9 : discordance à la base de la Formation Inférieure des Beni Issef (D1) et à la base de la Formation Supérieure des Beni Issef (D2) ; 10 : échantillons fossilifères ; 11 : échantillons pétrographiques.

The upper member mainly consists of grey-dark and/or brown massive and gritty marls and minor mudrocks, with interbedded sandstones, deposited on a siliciclastic platform. The lowermost part of this upper member is characterized by lenticular bodies of thick- to medium-bedded sandstones, laterally passing to marls and mudrocks. Upwards, sandstones become rare and the upper 80 m of the member are made up mostly of grey marls, with scarce thin-bedded sandstones and siltstones, and a single lenticular debris-flow bed. Consequently, a fining upward trend could be recognized in the stratigraphic development of the upper member of the Lower Beni Issef Fm.

The Lower Beni Issef Fm is deformed by cylindrical metre- to hectometre-sized open asymmetrical folds, with local reversed limbs (Figs. 1B and 3). Folds can be observed in the Oued ed Dhoûs, flowing along the axis of a synclinal structure (Fig. 1B), and southward of Dhar Dedmame, where they are ESE-verging and characterized by NNE-SSW beds with reversed limbs highly dipping westward (60°–70°).

The Lower Beni Issef Fm is unconformably overlaid by the Upper Beni Issef Fm. The contact is sub-horizontal or gently dipping south- or eastward (Fig. 2B). No folding is recognizable in the Upper Beni Issef Fm: everywhere beds are sub-horizontal or gently dipping towards the east, showing the same attitude of the basal contact. So, the angular unconformity with the folded Lower Beni Issef Fm is clearly evident (Figs. 1B and 3).

The Upper Beni Issef Fm is up to 550 m thick and crops out in the eastern part of the studied area. Also this formation is organized into two members. The lower member, 400 m thick (Fig. 4), shows a thinning-fining upward trend and starts with coarse conglomerates, well exposed at Dhar Dadmame (Figs. 1B and 3). These conglomerates are followed by metre- to plurimetre-thick, medium- to coarse-grained, well-bedded sandstones, with few intercalated marl and clay beds. Sandstones display various sedimentary structures, as planar-cross bedding, parallel, oblique and herringbone-cross stratifications, indicating shallow marine palaeoenvironments. Locally, sandstones are amalgamated, show normal and inverse graded bedding, and alternate with pebbly sandstones and both disorganized and organized conglomerates.

The upper member does not exceed 150 m. It is mainly made of grey-blue marls and mudrocks, clearly prevailing on thin-bedded medium- to fine-grained sandstones and siltstones, evidencing a clear fining upward trend.

The succession of the Upper Beni Issef indicates deposition in a channelized marine delta (lower member), with transgressive evolution towards pro-delta pelites (upper member).

3 Biostratigraphy

Thirty samples of marls and clays of the Lower and Upper Beni Issef Fms have been collected for a biostratigraphic study, using calcareous nannofossils. The location of the samples (DS599-DS618 in the Lower Beni Issef Fm and DS619-DS627 in the Upper Beni Issef Fm) is shown in Fig. 4. Taking into account the systematic reworking occurring in turbiditic and non pelagic sediments, we considered only the First Occurrence (FO) of the recognized taxa, because the Last Occurrence (LO), the acme zones, the state of preservation of the taxa, and the quantitative analysis are meaningless in these sediments. Therefore, the estimated ages must be interpreted as the oldest possible ages.

The samples have been prepared according to the C procedure described by de Capoa et al. (2003). They have been crushed, treated with sodium hypochlorite for 6 h according to Eshet (1996) and centrifuged with spin at 2500 rpm for 80 sec until the supernatant is clear. Calcareous nannofossils have been studied by optical microscope, 1250×. Most of the recognized specimens were affected by dissolution, overgrowth and/or recrystallization. In the present work, we used the stratigraphic scales of Martini (1971), Okada and Bukry (1980), Theodoridis (1984), Perch-Nielsen (1985a, 1985b), Cande and Kent (1992), Berggren et al. (1995).

Nine samples were barren. The nannoflora assemblages are reported in Table 1 and the markers in Fig. 5. The clearly reworked Cretaceous and Paleogene taxa, very common, as already noticed by Didon and Feinberg (1979), prevailing in many samples, have been omitted.

Nannofossiles calcaires des Formations Inférieure et Supérieure des Beni Issef.

| Lower Beni Issef Fm | Upper Beni Issef FM | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Samples | DS599 | DS600 | DS601 | DS602 | DS604 | DS605 | DS606 | DS608 | DS609 | DS610 | DS612 | DS614 | DS615 | DS619b | DS620 | DS621 | DS623 | DS624 | DS625 | DS626 | DS627 |

| Amaurolithus cf. tricorniculatus | M | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Braarudosphaera bigelowii | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||

| Calcidiscus macintyrei | M | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Coccolithus pelagicus | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Cyclicargolithus floridanus | X | X | X | X | X | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | |||||||

| Discoaster deflandrei | X | X | R | R | R | R | R | ||||||||||||||

| Discoaster surculus | M | M | |||||||||||||||||||

| Discoaster variabilis | M | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||||

| Ericsonia cava | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| Helicosphaera carteri | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||

| Helicosphaera euphratis | X | X | R | R | |||||||||||||||||

| Helicosphaera sellii | M | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Rhabdosphaera clavigera | X | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Reticulofenestra minuta | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||||||

| Reticulofenestra perplexa | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Reticulofenestra pseudoumbilicus | M | X | X | ||||||||||||||||||

| Sphenolithus abies | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||||

| Sphenolithus moriformis | X | X | X | R | |||||||||||||||||

| Sphenolithus villae | X | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Umbilicosphaera rotula | X |

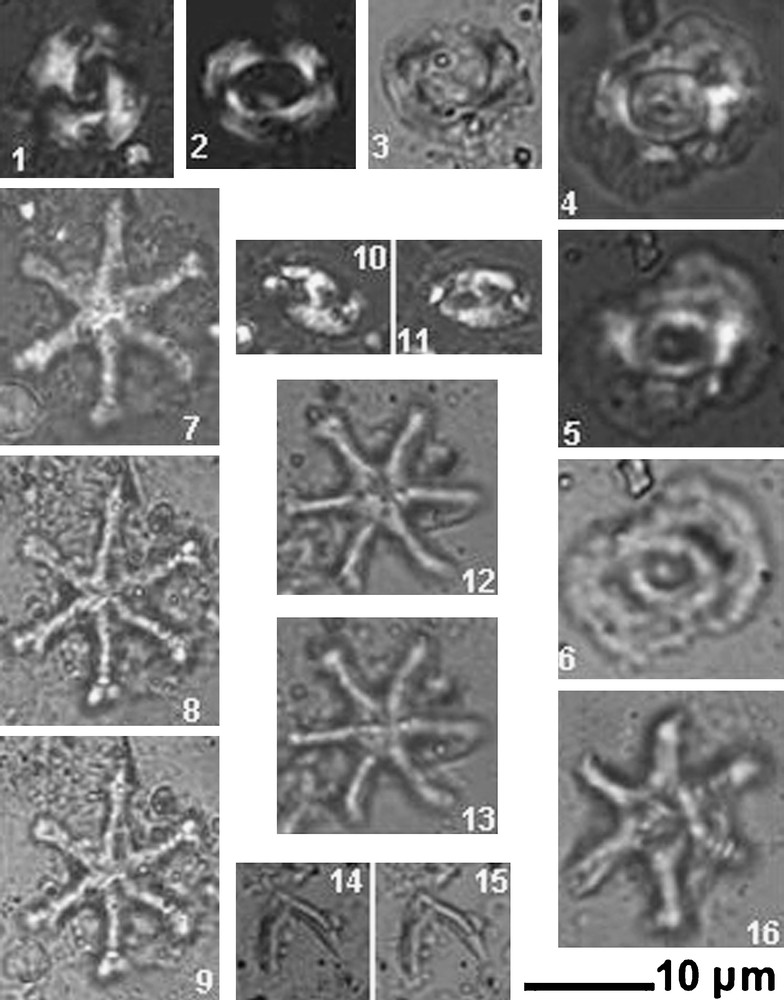

Calcareous nannofossils recognized in the Lower and Upper Beni Issef Fms (all specimens × 2500): 1: Reticulofenestra pseudoumbilicus (sample DS600); 2–3: Reticulofenestra pseudoumbilicus (sample DS614); 4–6: Calcidiscus macintyrei (sample DS605); 7–9: Discoaster surculus (sample DS609); 10–11: Helicosphaera sellii (sample DS610); 12–13: Discoaster surculus (sample DS610); 14–15: Amaurolithus cf. tricorniculatus (sample DS623); 16: Discoaster variabilis (sample DS600).

Nannofossiles calcaires reconnus dans les Formations Inférieure et Supérieure des Beni Issef (tous les spécimens × 2500) : 1 : Reticulofenestra pseudoumbilicus (échantillon DS600) ; 2–3 : Reticulofenestra pseudoumbilicus (échantillon DS614) ; 4–6 : Calcidiscus macintyrei (échantillon DS605) ; 7–9 : Discoaster surculus (échantillon DS609) ; 10–11 : Helicosphaera sellii (échantillon DS610) ; 12–13 : Discoaster surculus (échantillon DS610) ; 14–15 : Amaurolithus cf. tricorniculatus (échantillon DS623) ; 16 : Discoaster variabilis (échantillon DS600).

In sample DS 600, collected 17 m above the base of the Lower Beni Issef Fm near Dhar Dedmame (Saf Asshane), the occurrence of Discoaster variabilis and Reticulofenestra pseudoumbilicus, already recognized by Didon and Feinberg (1979), both appearing at the top of Zone NN4 of Martini (1971), corresponding to the top of Zone CN3 of Okada and Bukry (1980), indicates an age not older than Langhian. These beds have furnished (sampling in 1996, cf. Durand-Delga (2006)) Sphenolithus heteromorphus (determination of H. Feinberg) NN 4-5 in age. The same age is indicated by the occurrence of Calcidiscus macintyrei in the sample DS 605, collected 7 m further up. In samples DS 609 and DS 610, collected at 45 and 50 m above the base of the succession, respectively, the presence of Discoaster surculus and Helicosphaera sellii testifies to an age not older than Late Tortonian (i.e. Zone NN11a, corresponding to the Zone CN9a). This age is difficult to reconcile with a possible Langhian age for the interval containing samples DS 600 and DS 605, because the lower member of the studied succession (Fig. 4) does not show any evidence of stratigraphic break or of condensation. Therefore, it is likely that the Langhian assemblages found in samples DS 600-DS 605 are reworked. Regarding to the Late Burdigalian-Langhian age proposed on the basis of foraminifera and nannofossils by Didon and Feinberg (1979), it must be noticed that the nannofossil assemblages reported by these authors are characterized by the occurrence of taxa spanning the Burdigalian-Tortonian, thus not allowing to limit the succession to the Burdigalian-Langhian. Similarly, the foraminifera indicating a Late Burdigalian age all occur also in the Langhian. Actually, a Langhian age is only constrained by the occurrence of some foraminifera, including P. glomerosa, P. transitoria and Gd. bisphericus. However, Didon and Feinberg (1979) recognize also in the Langhian foraminifera assemblages some taxa (Paragloborotalia mayeri Cushman & Ellisor and Globoturborotalita apertura Cushman, whose FAD has been more recently placed in the Late Serravallian (Chaisson and Pearson, 1997; Turco et al., 2002) and in the Early Tortonian (Zone N14; FAD 11.19 ± 0 Ma (Berggren et al., 1995; Chaisson and Pearson, 1997)), respectively. In conclusion, also taking into account the sedimentary facies of the Lower Beni Issef Fm, we think probable that this formation was deposited since the Tortonian, because taxa indicating an age not older than the Late Tortonian are already present in samples collected 45 m above its base. However, a Langhian-Serravallian age for the lowest beds of the base of the formation (cf. Durand-Delga (2006)) cannot be totally excluded.

As to the Upper Beni Issef Fm, the first productive sample, with biostratigraphically significant taxa, is DS 620, in which Sphenolithus abies occurs. This taxon appears in the Zone NN5, corresponding to the Zone CN4 (Middle-Late Langhian), but this age is clearly meaningless, because taxa indicating an age not older than Late Tortonian have been recognized in the underlying Lower Beni Issef Fm. However, the sample DS 623, collected nearly 150 m from the base of the Upper Beni Issef Fm has furnished Amaurolithus cf. tricorniculatus, whose FO is indicated in the Zone NN11b = Zone CN9b. This taxon would testify to an age not older than Messinian. This age agrees with both the field data and the youngest age recognized in the Lower Beni Issef Fm.

4 Petrography

Eleven sandstone samples were collected from the Dhar Dedmame–Jebel Krakra section (Figs. 1B and 3), four samples of which (BI 1 to BI 4) come from the Lower Beni Issef Fm and seven samples (BI 5 to BI 11) from the Upper Beni Issef Fm. The location of samples is indicated in Fig. 4.

All thin sections were etched with HF and stained by immersion in sodium cobaltinitrite solution to allow the identification of feldspars. Finally, at least 500 points were counted in each thin section, and assigned to 50 petrographic categories including eight siliciclastic and carbonate matrix and cement. In order to minimize the variation of composition with grain size, point counts were performed following the procedures proposed by Gazzi-Dickinson method (Dickinson, 1970; Gazzi, 1966; Ingersoll et al., 1984; Zuffa, 1985). Point-count categories and recalculated parameters are those used by Dickinson (1970) (QtFL, QmFLt, QmKP plots), Ingersoll and Suczek (1979) (QpLvmLsm, LmLvLs) and Critelli and Le Pera (1994).

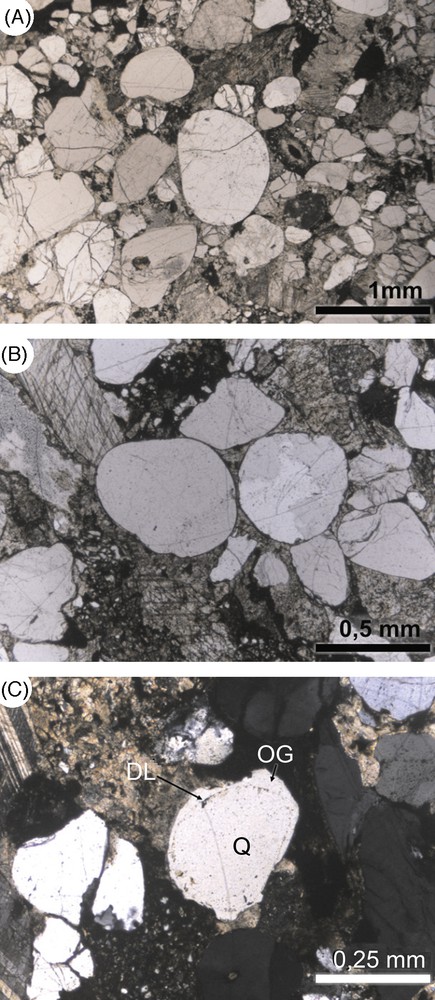

The arenite samples of both Lower and Upper Beni Issef Fms are poorly sorted and characterized by sub-rounded to well-rounded grains, and range from medium- to coarse-grained size. The interstitial component is widely represented by siliciclastic matrix and rarely carbonate matrix and cement (Fig. 6).

Microphotos of arenites of Lower and Upper Beni Issef Fms, showing well-rounded and fractured monomineralic quartz grains and subordinate feldspars of Numidian provenance, siltstones and calcite replacing unknown grains (A, B). In C it is possible to observe quartz grain (Q) with syntaxial overgrowth (OG) indicated by dustline (DL).

Microphotos de grès des Formations Inférieure et Supérieure des Beni Issef, qui mettent en évidence des granules de quartz monominéral bien arrondis et fracturés et, en quantité subordonnée, de feldspaths, érodés du Numidien, siltites et calcite remplaçant des granules d’origine inconnue (A, B). En C, il est possible d’observer des granules de quartz (Q), avec accroissement syntaxial (OG) mis en évidence par une très mince ligne noire (DL).

The composition of these arenites (Fig. 7) is quartzolithic and grains consist mainly of non-carbonate extrabasinal clasts (NCE952CE52CI00). They are characterized by a prevalence of monocrystalline quartz ranging from 26% to 51%; most of them show authigenic cement performing as syntaxial quartz overgrowths (Fig. 6C), indicating a provenance from recycling of sedimentary successions (Qm6113F21Lt3713; Qt6213F21Lt3613). Feldspars are negligible, potassium feldspar is prevalent, and plagioclase does not present intense sericitization (Qm972 K22 P11; P/F = 0.58; Fig. 7). The lithic component is abundant and almost all samples show a notable content of sedimentary lithic fragments and, subordinately, of metamorphic lithics (Lm1223 Lv12 Ls8723; Fig. 7), with the exception of one sample (BI 6), which is anomalously rich in slate fragments. Sedimentary lithics are dominantly siliciclastic, and represented by siltstone and shale, whereas carbonate grains are subordinate, and include micritic, silty arenitic and rarer sparitic limestones (Lm1223 Lss7224 Lsc1611). Metamorphic lithic components are low-metamorphic grade grains of slate, phyllite and fine-grained schist. Volcanic and metavolcanic grains are negligible.

NCE CE CI, QmFLt, QmKP, LmLvLs, LmLssLsc, RgRsRm and RgRvRm ternary plots of the Lower and Upper Beni Issef Fms arenites. NCE: non-carbonate extrabasinal fragments; CE: carbonate extrabasinal fragments; CI: carbonate intrabasinal fragments; Qm: monocrystalline quartz; F: total K-feldspar (K) and plagioclase (P); Lt: total aphanitic lithic and extrabasinal carbonate fragments; Lm: total metamorphic lithic fragments; Lv: total volcanic lithic fragments; Ls: total sedimentary lithic fragments; Lss: total siliciclastic sedimentary lithic fragments; Lsc: total carbonate sedimentary lithic fragments; Rg: total plutonic rock fragments; Rs: total sedimentary rock and lithic fragments; Rm: total metamorphic rock and lithic fragments; Rv: total volcanic rock and lithic fragments.

Diagrammes triangulaires NCE CE CI, QmFLt, QmKP, LmLvLs, LmLssLsc, RgRsRm and RgRvRm des grès des Formations Inférieure et Supérieure des Beni Issef. NCE : fragments non carbonatés extrabassinaux ; CE : fragments carbonatés extrabassinaux ; CI : fragments carbonatés intrabassinaux ; Qm : quartz monocristallin ; F : total de K-feldspath (K) et plagioclase (P) ; Lt : total des fragments lithiques aphanitiques et carbonatés extrabassinaux ; Lm : total des fragments lithiques métamorphiques ; Lv : total des fragments lithiques volcaniques ; Ls : total des fragments lithiques sédimentaires ; Lss : total des fragments lithiques sédimentaires siliciclastiques ; Lsc : total des fragments lithiques sédimentaires carbonatés ; Rg : total des fragments de roches plutoniques ; Rs : total des fragments de roches sédimentaires et lithiques ; Rm : total des fragments de roches métamorphiques et lithiques ; Rv : total des fragments de roches volcaniques et lithiques.

Finally, total component of phaneritic and aphanitic grains is characterized by siliciclastic sedimentary clasts that are dominant with respect to metamorphic and granitoid rock fragments (Rg32 Rs7822 Rm1922; Fig. 7). Considering the non-sedimentary fraction, fine- and coarse-grained metamorphic rock fragments, including slate and phyllite, clearly prevail on granitoid and volcanic fragments (Rg1711 Rv712 Rm7614).

5 Discussion and conclusions

Field and biostratigraphic data allow us to recognize in the “Miocène des Beni Issef” two clastic formations (Lower and Upper Beni Issef Fms.), separated by a significant angular unconformity, related to an important compressive tectonic phase.

The Lower Beni Issef Fm, sealing the tectonic contact between the Intrarifian External Tanger and Loukkos Units, was deposited within an up-thrust basin after their stacking. Therefore, it represents an important constraint for the deformation age of the Intrarifian Zone. The biostratigraphic data indicate an age not older than the Late Tortonian in samples collected 45–50 m above the base of the formation. This is the first reconnaissance of age younger than Langhian in the Beni Issef successions after Durand-Delga and Lespinasse (1965), but we cannot exclude an age older than the Tortonian for the base of the formation. Taking into account these new data, the deformation age of the Intrarifian Zone could be constrained between the Late Serravallian, recognized by Zaghloul et al. (2005) at the top of the External Tanger Unit, and the Late Tortonian. These data would be also in agreement with the age of the Jebel Binet Fm, sealing, in the area northeast of Taza, the contact between the Intrarifian Bou Haddoud and Aknoul Nappes (Septfontaine, 1983). In conclusion, taking into account that Tortonian deposits rest also on some Prerifian Units (Ben Yaich, 1991; Ben Yaich et al., 1988; Favre, 1995; Feinberg, 1986; Médioni and Wernli, 1978; Kerzazi, 1984; Tejera de and Leon, 1993; Tejera de Leon and Duée, 2003), the available biostratigraphic data seem indicate that the deformation of the whole External Domain occurred in the time span Late Serravallian-Late Tortonian. However, a stratigraphic revision at a regional scale of clastic deposits unconformable on the Rifian External Units is necessary.

The Lower Beni Issef Fm is made up of a lower member, characterized by coarse conglomerate layers (debris flows) and boulders, and an upper member, consisting of sandy marls with sandstone beds. These clasts of the lower member come essentially from the Flysch Basin nappes (Beni Ider, Melloussa and Numidian Nappes), which constituted the inner margin of the Beni Issef basin. The upwards evolution of the sedimentary facies testifies for the passage from a proximal environment, in a very unstable tectonic setting, to a sandy-pelitic environment, probably indicating a time span of relative tectonic quiescence. This decreasing tectonic activity could have been responsible for the thinning-upwards evolution of the Lower Beni Issef succession.

The Lower Beni Issef Fm is affected by intense folding, testifying to an important compressive tectonic phase, which allowed to emersion and erosion of the Lower Beni Issef Fm and its substratum. The formation, therefore, can be considered as an Upper Miocene post-nappes deposit, lying on the Intrarifian Units, involved in a successive tectonic phase, in the Late Tortonian-Early Messinian time span, which was responsible for its folding and erosion.

The Upper Beni Issef Fm testifies to a new sedimentary cycle deposited in an intramontane marine basin after the above-mentioned deformation phase, on both the nappe stack and the Lower Beni Issef Fm. Biostratigraphic data point out a probable Messinian age near the base of the formation, which is only gently deformed and, therefore, must be considered as a “post-orogenic” deposit. However, it evidences a Late Miocene, probably intra-Messinian tectonic phase, up to now unrecognized in the Rifian chain. The fining- and thinning-upward stratigraphic evolution from its lower to its upper member probably indicates an increasing rate of subsidence, which produced an accommodation space exceeding the sedimentary supply.

Detrital modes of the arenites of both Lower Beni Issef and Upper Beni Issef Fms are quite homogeneous and no differences are recognizable between these formations. They suggest a provenance from recycled sedimentary successions, all falling (Fig. 7) in the QR (Quartzose Recycled) and TR (Transitional Recycled) fields of Dickinson et al. (1983). In these arenites, the abundance of both monocrystalline well-rounded quartzose grains and lithic grains, as shale and siltstone (Fig. 6), testifies that the sedimentary successions cropping out in the source areas of the clastic supply were prevalently made up of quartzarenites, fine-grained turbidites and pelagic rocks. These successions contained also fine-grained carbonate beds (marly and silty limestone); sparitic fragments derive from recrystallization rather than from erosion of shallow water limestones. These data suggest the arenites of Lower Beni Issef and Upper Beni Issef Fms were fed by Flysch Basin Units, mainly the Numidian Nappe, and by External Units, as the External Tanger and Loukkos Units. Therefore, also the arenites, as the conglomerate beds and boulders, confirm a local provenance of the clastic supply, from areas adjacent to the sedimentation basins, where the Numidian Nappe and the External Units were widely exposed.

At a Mediterranean scale, the above results could be correlated with data available in the Tellian and Sicilian Maghrebids (Durand-Delga, 1980; Grasso, 2001), although recent and detailed researches on the External Domains of these orogenic sectors are lacking. In the Sicilian Maghrebids, however, an intra-Messinian unconformity has been evidenced from long time (Decima and Wezel, 1971). It is noteworthy that in southern Apennines an intra-Messinian tectonic phase is well documented in units derived from all paleogeographic domains. In the Internal (Ortolani et al., 1998) and Oceanic (Lucanian) Units (Amore et al., 1988), this tectonic phase is testified only by an unconformity, well observable in Calabria and in the Cilento region, near 120 km south-east of Naples, because the palaeochain as a bulk passively followed the deformation of the External Domain. The tectonic phase, on the contrary, is well recognizable in some External Zones, affected by the compressive deformation only during Messinian (Amore et al., 2005; Basso et al., 2001; Patacca and Scandone, 2007 and references therein).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by MIUR-PRIN Research Project 2006 “Cenozoic clastic sedimentation in the southern branch of the Tethys in the Betic-Rifian Arc and northern Apennines: consequences for the palaeogeographic and palaeotectonic evolution of the central-western Mediterranean (Research Unit of the University of Urbino, responsible Vincenzo Perrone) and by Proyecto No. CGL2009-09249 (MCI, Spain).