1 Introduction

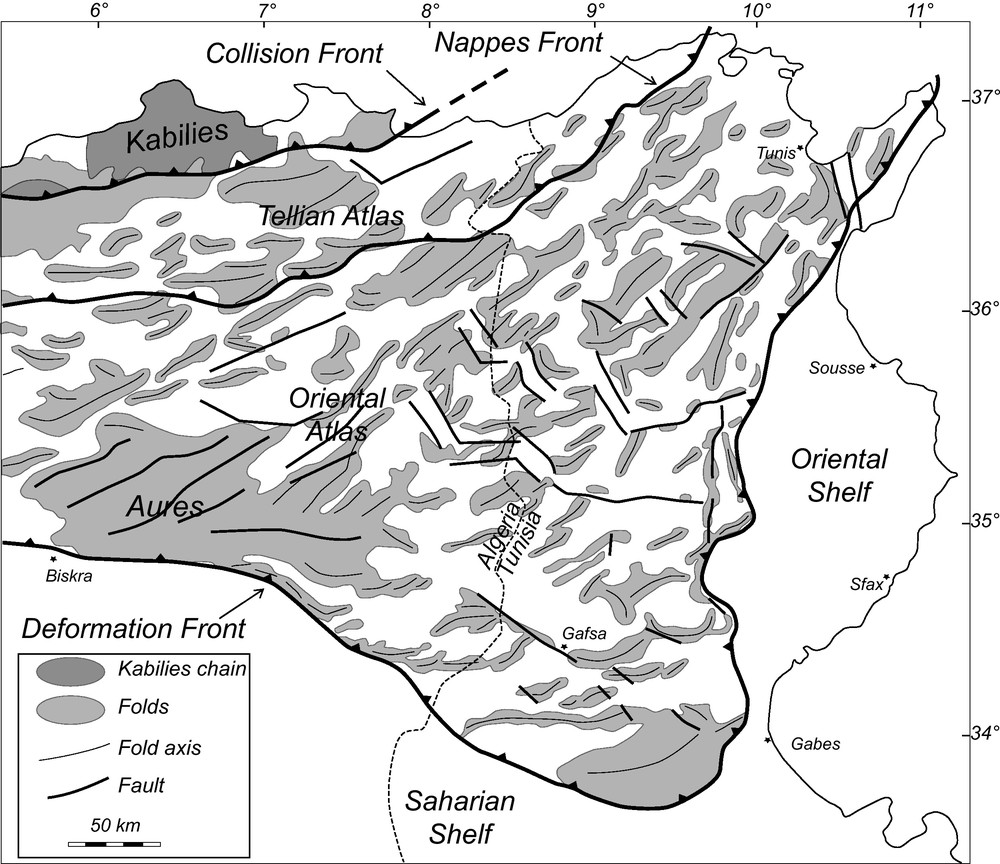

Northern and central Tunisia are dominated by the Tunisian Atlas, and are divided into several structural zones, each characterized by faults and folds of variable magnitude (Fig. 1). By its location at the northern African margin, northern Tunisia is strongly influenced by the N135E-trending convergence of the African and Eurasian plates estimated at about 5 mm/yr (Ahmadi et al., 2006; Burollet, 1951; Caire et al., 1971; Calais et al., 2003; Castany, 1951; Durand-Delga and Fonboté, 1980; Hfaiedh, 1983; Kacem, 2004; Nocquet and Calais, 2004; Piqué et al., 2002). In Late Quaternary, seismological activity has been moderate to locally intense; several earthquakes have been recorded in Northeast of Tunisia (Ben Ayed, 1986; Hfaiedh, 1983; Vaufrey, 1932). This activity could take place in Quaternary folds, reverse and strike slip faults which deserve to be more studied to constrain modern rates of horizontal shortening and fold related fault activity (as illustrated, for example, by the 1980 El Asnam earthquake in Algeria [Philip and Meghraoui, 1983]). The most active tectonic deformation is generally related to the reactivation of pre-existing NW-SE, east-west and north-south trending strike slip faulting (Dlala, 1995; Dlala and Rebai, 1994). One of the best examples of active faulting is the destructive earthquake, which ruined the antique city of Utique (35 km north of modern Tunis) in 412 AD (Vogt, 1993) and left surface deformation still visible (Ben Ayed, 1986). It may have originated in the east-west-trending Utique fold structure, marked by both relief and seismicity (Figs. 2 and 3 [Dlala, 1995]): this structure is thus of major importance in the seismic hazard assessment of the Tunis city surroundings.

Structural map of oriental Atlas (modified after Ahmadi, 2006).

Carte structurale de l’Atlas oriental (modifiée d’après Ahmadi, 2006).

Geological map of northern Tunisia (Office National des Mines de Tunisie, 1987). 1: Late Quaternary sediments, 2: Lower Quaternary, 3: Pliocene, 4: Miocene, 5: Cretaceous, 6: Trias, 7: Oil well, 8: Fault, 9: Seismic line, 10: Administrative boundary of Tunis City. Seismicity from the historical catalog covers the period between 412 AD and 1975 AD (Vogt, 1993); symbol size represents the intensity I.

Carte géologique de la Tunisie nord-orientale (Office National des Mines de Tunisie, 1987). 1 : alluvions du quaternaire récent, 2 : Quaternaire ancien, 3 : Pliocène, 4 : Miocène, 5 : Crétacé, 6 : Trias, 7 : forage pétrolier, 8 : faille, 9 : profil sismique, 10 : contours de la ville de Tunis (limites administratives). Les séismes historiques ayant eu lieu entre 412 et 1975 (Vogt, 1993) sont représentés par des symboles dont la taille varie en fonction de l’intensité I.

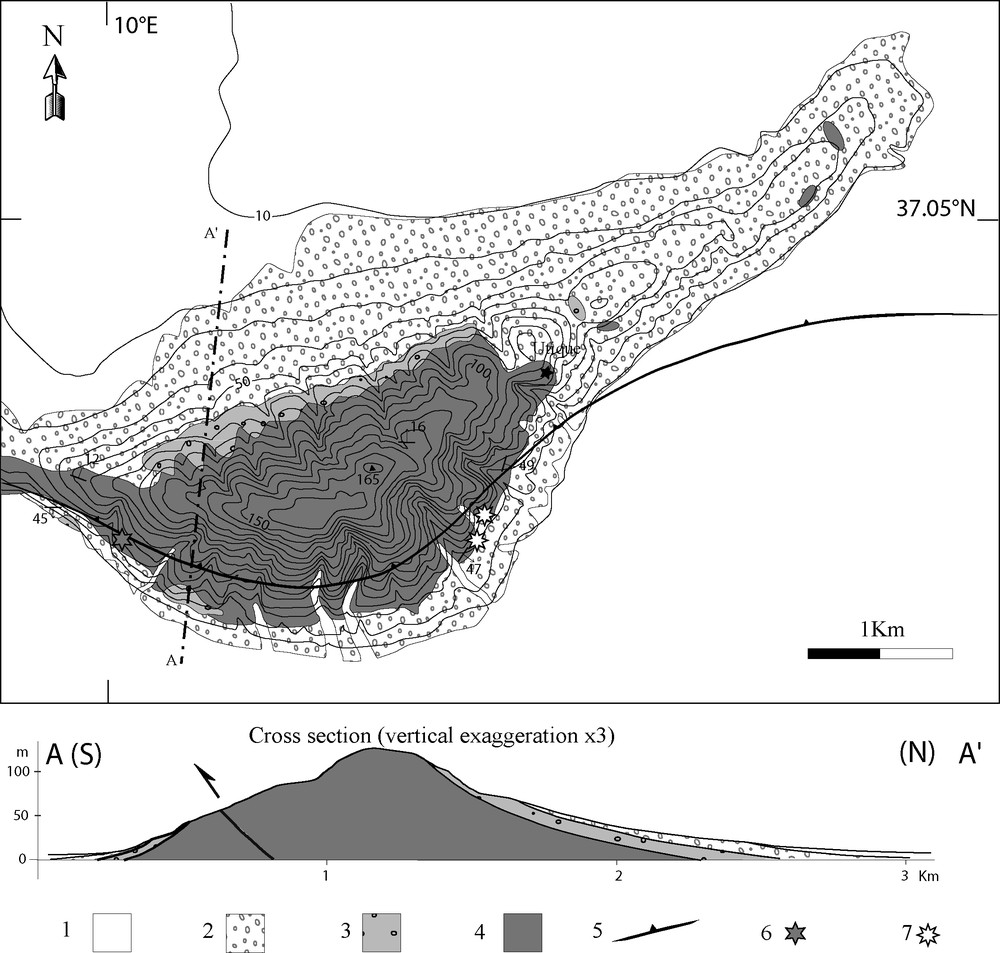

Geological map and cross-section of the Utique anticline. 1: modern alluvium; 2: Quaternary soils and colluvium; 3: Upper Villafranchian; 4: Pliocene (Porto Farina Fm); 5: fault, as seen by geophysical methods (Kacem, 2004); 6-location of Fig. 7; 7-location of Fig. 6.

Carte et coupe géologiques du pli d’Utique. 1 : alluvions récentes ; 2 : sols et colluvions quaternaires ; 3 : Villafranchien supérieur ; 4 : Pliocène (formation Porto Farina) ; 5 : faille détectée par la géophysique (Kacem, 2004); 6-site de la Fig. 7; 7-site de la Fig. 6.

The following study presents an integrated approach based on field observations, neotectonic data, geological sections, seismic reflection data, and well logs to discuss the Utique fold kinematics and estimate the Utique fold-related fault motion.

2 Geological setting

The Utique east-trending fold is located near the Utique village (about 35 km north of Tunis, Fig. 2). It bounds the Mio-Plio-Quaternary Kechabta-Messeftine continental shelf Basin to the southeast, which is characterized by anticlines and lowlands (Ben Ayed, 1980; Burollet, 1951). The fold emerges from a flat area made of Medjerdah river Late Quaternary (Holocene) alluvium. Seismic profiles indicate it is affected by an east-west-trending reverse fault (dip to the north) which outcrops in some places (see thereafter), but not yet clearly described (Ben Ayed, 1986; Dlala, 1995; Oueslati, 1993). The fold forms a topographic ridge about 3 km wide and 200 m high, and emerges from the lowlands for ∼8 km.

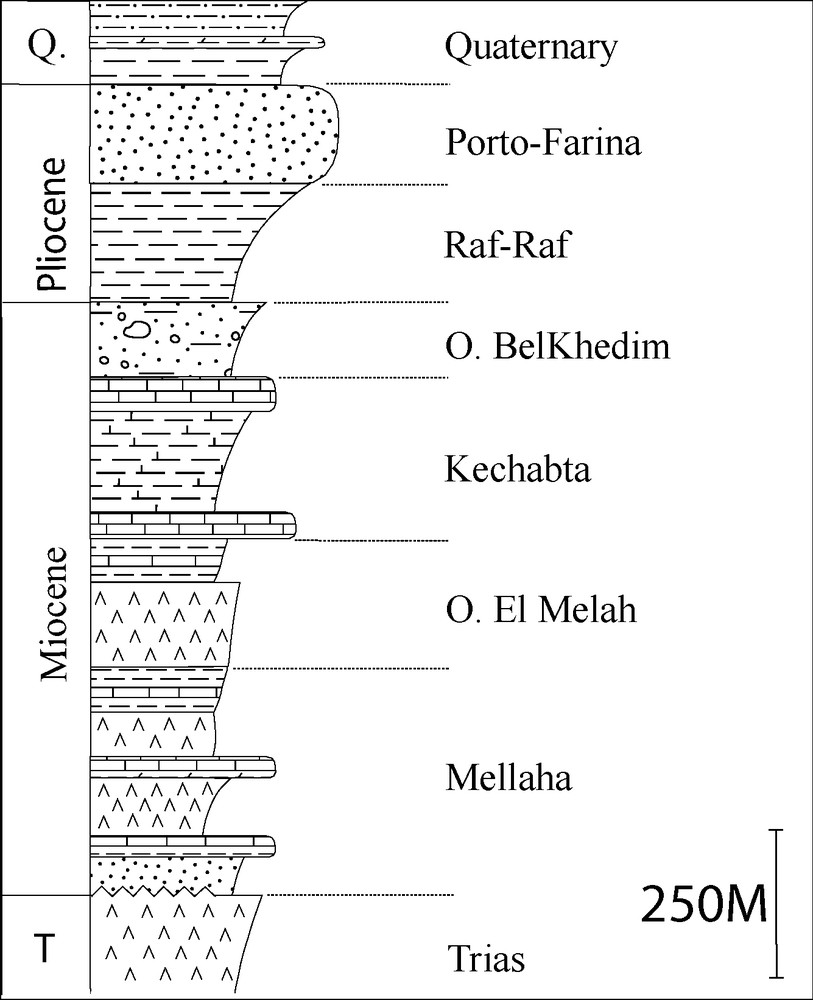

The lithostratigraphical column is known after outcrops and well-logs (ETAP, 2010). Rocks from Trias up to Quaternary outcrop in the area mainly in Anticlines (main relief constituted by the “Jebels”) and plains, respectively (Melki, 1997; Office National des Mines de Tunisie, 1987). Additional stratigraphic information comes from wells Ut1 and BM1 and from the transverse seismic line L1 (Fig. 2). Ut1 well data, confirmed by the seismic profile L1, show mainly 1500 m-thick Neogene units lying above thick chaotic Triassic evaporites. The 1000 m-thick-Upper Miocene is composed of 4 formations (Mellaha, Oued El Melah, Kechabta and Oued Bel Khedim, Fig. 4). The Plio-Quaternary sedimentary pile is about 360 m thick. The lithologic description of these sedimentary units is based on Ut1 well analysis and shows from the surface downwards (ETAP, 2010):

- • Quaternary rocks (up to 60 meters), predominantly continental to restricted lagoon shales, sands conglomerates, calcareous crusts and alluvial deposits;

- • the predominantly sandstone-made Upper Pliocene Porto-Farina formation (up to 300 m) lying above the Lower Pliocene Raf-Raf formation (up to 300 m) which is constituted by calcareous claystone and sand. This level appears only on Ut1 well log;

- • Upper Miocene (Messinian) Oued Bel Khedim formation (up to 300 m) of littoral evaporitic facies, lagoonal shales and local lacustrine limestones;

- • the Kechabta formation (Tortonian) (up to 200 m) constituted by lagoonal to continental shales and sands;

- • the Oued El Melah formation (Tortonian-Upper Serravalian) (up to 150 m) showing predominantly claystone, anhydrite (gypsum) with minor sand, dolomite and limestone;

- • the Mellaha formation (Serravalian) (up to 350 m) evaporitic at its base, grading to interbedded claystone, and anhydride towards its top, with minor dolomite;

- • Trias formations of dolomite and some pyrobitumen, with rare gypsum.

Stratigraphic log of the study area.

Log stratigraphique de la zone d’étude.

This stratigraphy reveals several incompetent evaporite and shale intervals that can be considered as detachment horizons, as it will be shown in this work. These are the Oued El Melah and Mellaha Formations (Tortonian-Upper Serravalian), and Oued Bel Khedim (Messinian) Formations (Fig. 4).

The Quaternary has been studied in details by Oueslati (Oueslati, 1993). It is constituted by successive clayish strata each one usually being cemented on top by a calcareous crust more or less thick (calcrete). The number of strata varies from site to site, but the general trend is clay color evolution from gray-green to red-pink topwards. The succession could be related to Quaternary glacial/interglacial alternation (Oueslati, 1993).

3 Seismological background

Fig. 2 is presenting the historical seismicity. The historical seismicity displayed comes form records of the historical catalog, spanning the period 408–1975 AD (Vogt, 1993) while instrumental seismicity is recorded since 1976 by the Tunisian National Meteorological Institute. In northeastern Tunisia, the background seismicity is important even if magnitudes are generally low, lower than 5. Moreover, the earthquake location figure is not informative about the seismogenic structures: no earthquake alignments could be detected. Earthquakes located are always within the first 15 km of the crust.

Since destructive earthquakes have been recorded in the past, the two main ones being the 408 AD in Utique and the 856 AD in Tunis (Vogt, 1993), studying the active structures in order to better define the seismogenic character is of primary importance. It drove the way this study was conducted.

4 New data and interpretation

4.1 Seismic profiles

The area of interest is well covered by 2D seismic survey acquired by the Maxus Ltd in 1983 and 1994. These seismic profiles are of moderate quality and some of them are not migrated. Thus we present thereafter careful interpretations.

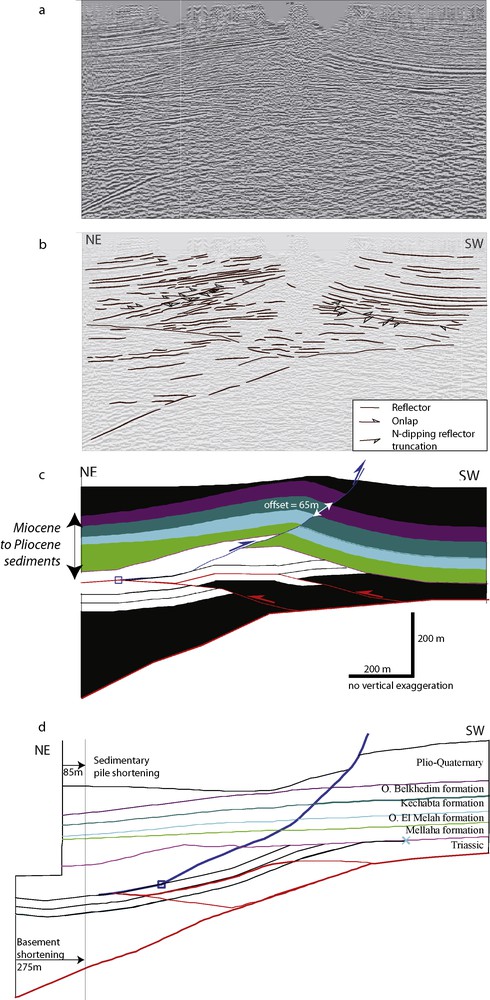

We use the seismic profile L1 (with additional information from profile L2, Fig. 2) trending north–south. This profile crosses the Utique fold and extends for about 15 km from northern Utique to Djebel Ammar to the south. The profile has been depth-converted thanks to stratigraphic data coming from wells Utique1 and Bm1, closely located (2.2 and 1.8 km, respectively; Fig. 2). The Ut1 well is 2500 m deep.

The seismic profile L1 exhibits an erosional unconformity, which separates two stratigraphic packages (Fig. 5). This unconformity is marked by the truncation of north-dipping reflectors corresponding to a lower stratigraphic package and by the onlap of the upper stratigraphic package. Ut1 well data indicates the lower package is made of Mesozoic sediments whose strata in the upper part could be seen, its base being probably made of Triassic rocks. The overall Mesozoic sequence slightly dips to the north. A thick evaporitic section of the Mellaha formation (Serravalian) seals the north-dipping Triassic strata. Such an unconformity was previously reported by Brusset (Brusset, 1999) and Khomsi et al. (Khomsi et al., 2009). The Mellaha fm. is overlain by strata from Upper Miocene upward, which are merely isopach and constitute the upper package. These are only deformed by a thrust branching at depth into the Mellaha formation acting as a decollement level (see thereafter and Fig. 5). The structural style can be tracked on the seismic line. It consists obviously of a triangle zone defined by a deep-seated fault-bend fold and a shallow fault-propagation anticline (Utique anticline). Both folds are associated with south-verging thrusts, which sole-out in Triassic and Mellaha evaporates, respectively (Fig. 5). One must note that if the Mesozoic and the Lower Miocene formations are missing in the Utique structure, they are found at outcrop just 5 km to the south in the Djebel Ammar (Devolvé et al., 1980; Pini et al., 1971).

a: Seismic profile; b: Interpretation (no vertical exaggeration); c: Cross-section in Utique structure drawn after seismic line L1 and slip rate measurement; d: Unfolding cross-section back to Lowermost Miocene.

a : profil sismique ; b : interprétation (pas d’exagération verticale) ; c : coupe équilibrée de la structure d’Utique et estimation du raccourcissement ; d : coupe dépliée jusqu’aux couches du Miocène inférieur.

The seismic section has been analyzed using typical concepts of thrust tectonics (Dahlstrom, 1969; Dahlstrom, 1990; De Sitter, 1964; Jamison, 1987) in order to propose a balanced cross-section of the Utique fold, which gave important insights into the fold history. The Utique fold developed reactivating a pre-Miocene structure. Slip transfer is owing to an intermediate duplex developed in the lower stratigraphic package.

The cross-section was further analyzed by stepwise unfolding. This exercise is represented in Fig. 5. After a quiet period marked by Upper Miocene deposition over previously folded Mesozoic strata, the area has been shortened again. It is not possible to know when this shortening stage began, nor it is possible to be sure this shortening stage has continued up to today, even if such a hypothesis is probable regarding to the background local seismicity. During this last deformation stage, deformation is accommodated at depth by the Mellaha formation decollement (Figs. 4 and 5) and meanwhile by fault propagation folding in the uppermost, from Miocene upward, formations. Interestingly, this scenario implies a connection to deeper structures further south. It allows calculating a total shortening since the Mio-Pliocene boundary of about 690 m (0.14 mm/yr on average) in the basal part and of about 210 m in the uppermost formations (0.04 mm/yr). Note that individual formation offset decreases upward, as predicted by the fault propagation geometry (Ramsay and Huber, 1987; Rouvier, 1985; Suppe and Medwedeff, 1990). This implies that at surface, the maximum offset observable is much less than these 690 m. Actually, it must be less than the uppermost offset observed on the cross-section, which corresponds to the 170 m Mio-Pliocene boundary offset.

4.2 Geomorphology

Geomorphic investigations from Utique anticline were conducted through satellite imagery analysis, and by analysis of a digital elevation model (DEM) of the Utique fold (Fig. 3). The study of this DEM shows that the Utique anticline is trending east–west in the western part, and its trend changes to ENE–WSW in the eastern part. It is about 3 km wide and 200 m high. It is characterized by a steeply dipping forelimb (reaching 45°) and a gently dipping backlimb (not exceeding 30°). Both forelimb and backlimb exhibit a break in slope dividing them into two slope segments separated by a short “flat” with gentle slope (usually used for farming). In both limb the lower slope is shorter than the higher one, both slopes having close dip (Fig. 3). Gullies developed in fold limbs in Quaternary and Upper Pliocene (Porto Farina fm) rocks mantling the fold. In these gullies Quaternary rocks are discordant over the Pliocene ones.

4.3 Neotectonic markers

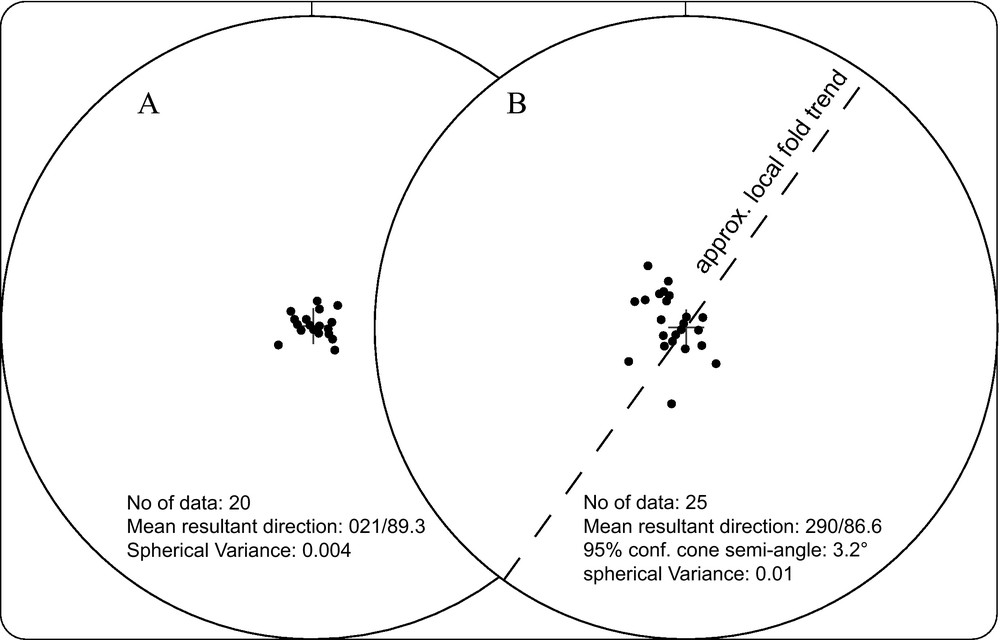

On the south limb of the fold, at least two calcretes horizons are found, attributed to Pleistocene and Holocene, respectively (Oueslati, 1993). These horizons contain calcareous nodules generated around plant roots. Originally, these nodules trend vertically; this is not necessarily the case for the horizon itself, which could have mantled an inclined slope. A careful measurement of calcareous concretion orientation has been carried in two locations on the southeastern limb of the fold (Fig. 6). They indicate a possible slight tilt (less than 5 degrees) with an axis perpendicular to the fold limb. If true, it would imply the tilt has occurred since Pleistocene there.

Wulf stereoplot of calcareous concretion data in two locations southeast of the fold. In A, no tilt is indicated whereas in B, a slight tilt of 3° in a direction N290° is possible (within 95% confidence), but not attested, this direction being roughly perpendicular to the fold trend.

Stéréogramme (projection de Wulf) de l’orientation des concrétions calcaires, à 2 endroits sur le flanc sud-est du pli. En A, il n’y a pas de basculement visible, alors qu’en B un léger basculement de l’ordre de 3° dans une direction N290° est possible (avec une confiance de 95 %), sans certitude ; cette direction est quasiment perpendiculaire à l’orientation du pli.

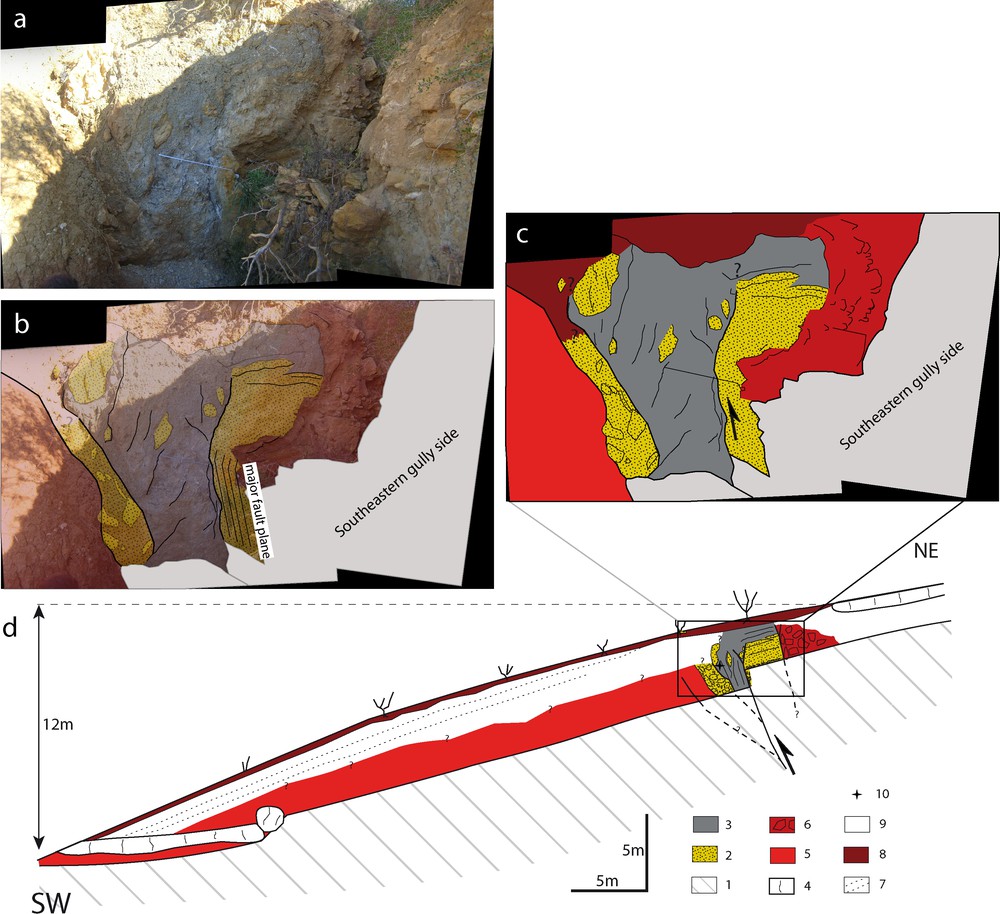

A fault that can be associated with the fold has been observed along the Tunis-Bizerte motorway at the time of its building, but unfortunately the outcrop has never been described and is no more visible (Ben Ayed, 1986; Dlala, 1995; Dlala and Rebai, 1994). In turn, after careful exploration of the fold, another outcrop was found in a quarry now turned into a dump (37°01.80’N; 10°00.00’E). A fault outcrops in a gully ∼5 m wide and ∼5m deep (Fig. 7). The gully seems to have experienced a complicated story with a first incision stage followed by recent filling and renewed incision that continues currently. This explains some strong differences observed on both sides of the gully; the southeastern side is the most representative and is schematized in Fig. 3 in which were added some observations made in the northwestern side. A fault plane was found, displaying important variations in trend and dip, the average values being a N150°E trend and an 80°N dip, with uncertainties evaluated to be ∼20°. It is accompanied by small faults that display an average N150°E-azimut and 60°N-dip. The fault offsets clearly some conglomerates made of Pliocene marine formation reworking and gray clay levels, observed elsewhere lying on top of calcrete. It is mantled by the recent gully infilling made of angular debris, which could have been affected by the fault (Fig. 7). The major fault and its associated minor faults are affecting, with sometimes offsets observed, the following formations (Fig. 7): some sandstones and conglomerates coming from Pliocene strata erosion (2 on Fig. 7); grey clays (3 on Fig. 7); red clays with calcrete remnants, typical form the Quaternary (Oueslati, 1993) (5 on Fig. 7). A disturbed formation, that can be considered as a fault gouge, made of clay and calcrete-derived sands, contains a piece of pottery, less than 2000 years-old after archeologist expertise (Slim Khosrof, National Institute of Patrimony, Tunis, personal communication).

Utique fold outcrop. a: Photography of the main fault plane; b: Interpretation of the photo: faults (the main ones are in bold); c: Interpretation of the photo; d: Outcrop scheme. The photo (a,b,c) corresponds to a zoom of the fault zone. Main lithological formations, in likely stratigraphic order: (1) Gully basement; (2) Sandstones and conglomerates mainly made of Pliocene material (3) Gray clays; (4) Calcareous crust; (5) Red clays with calcareous nodules; (6) Recent conglomerates; (7) Colluvial wedge; (8) Soil; (9) Undetermined; (10) Approximative pottery location.

Affleurement de la faille d’Utique. a : cliché du plan de faille majeur ; b ; cliché interprété en termes de failles ; les traits épais correspondent aux failles principales : c : cliché interprété ; d : Schéma de l’affleurement. La photo (a,b,c) correspond à la zone de la faille. Les principales formations sont données dans l’ordre stratigraphique a priori : (1) partie basale ; (2) sables et conglomérats issus du démantèlement du Pliocène ; (3) argiles grises ; (4) croûte calcaire ; (5) argiles rouges ; (6) débris récents ; (7) colluvions ; (8) sol ; (9) lithologie indéterminée ; (10) Position approximative de la poterie.

To sum up, the fault observed appears to have been active very recently, during the Holocene; it has a clear reverse component.

Observations around this gully indicate that the calcrete underwent a total ∼12 m vertical offset (Fig. 7). The calcrete often mantles the fold topography, but it is found faulted in numerous places in the lower fold slope described in the previous section. One may hypothesize that this lower slope corresponds to the total vertical calcrete offset, evaluated to be ∼40 m, corresponding to ∼45 m of fault motion if fault dip is 60°.

5 Discussion

The stepwise unfolding of the section including Utique structure shows that it was affected by two phases of compressional deformation. The first one is occurred during Miocene (attested by thickness variation of the Serravalian Mellaha formation) and caused folding over a passive ramp in Triassic sediment. The timing of the second one is unclear because of low definition of seismic data in its uppermost part: it clearly occurred after Serravalian. Tectonic studies in neighboring areas (and all over Tunisia) clearly indicate that compression begun early in Pleistocene after a Late Miocene to Late Pliocene extensional phase (Ben Ayed, 1986; Boukadi, 1994; Devolvé et al., 1980; Zargouni, 1985). Field observations of surface faulting, debris of less than 2000 years old pottery reworked and possibly tilted calcareous nodules at the fault zone suggest that the main compressional phase continues up to present.

A total shortening of 690 m has been measured indicating an average shortening rate of 0.14 mm/yr since the beginning of Pliocene. As already mentioned, compression must have begun early in Pleistocene (1.8 My); this leads to a most likely value for shortening rate of 0.38 mm/yr, corresponding to ∼8% of the current shortening in Tunisia (∼4.5 mm/yr in a direction N145°E between stable Africa and Sardinia after a compilation of results from D’Agostino and Selvaggi (2004) and Hollenstein et al. (2003). Interestingly, Ahmadi et al. (2006), Ahmadi (2006) made a restoration of a section crossing the whole Tunisia from north to south. He found a rough value for total shortening of 55 km, which cannot be the result of the Quaternary shortening alone (it would imply an average shortening velocity of ∼3 cm/yr). This does not contradict our data, which shows an older shortening phase (during Lower Miocene), even if it was less marked in the study area.

We observed that the Utique structure must be seismogenic. Indeed, it displays clear evidences of surface rupture. Historic (since roman era) displacements are meter-scale. Speculatively we can use empirical relations from Wells and Coppersmith (1994), with a surface length of ∼8 km, to evaluate the order of earthquake magnitude (∼6) or typical surface offset (∼0.5 m); conversely earthquake recurrence interval should be of ∼103–104 yr. These are rough evaluations. Similar analysis should be extended to adjacent regions to give more precision to fault segmentation.

6 Conclusion

We provide evidence of recent surface rupture along the Utique Fold. In addition, after studying seismic cross-section we are able to evaluate a total shortening of 690 m during the Quaternary. This corresponds to an average shortening rate of about 0.38 mm/yr, one tenth of the total shortening accommodated over the whole country. This makes the Utique fault propagation fold an important structure when regarding seismological hazard of the 1.5 M people Tunis City, located 35 km to the south.

Acknowledgements

This study benefited from financial support by the “Comité mixte de coopération universitaire (CMCU)” between the Tunisian and French foreign ministries. Joseph Martinod is warmly thanked both for support and for manuscript improvements. Both an anonymous reviewer and editor, M. Campillo, made useful advice for manuscript improvement.