1 Introduction

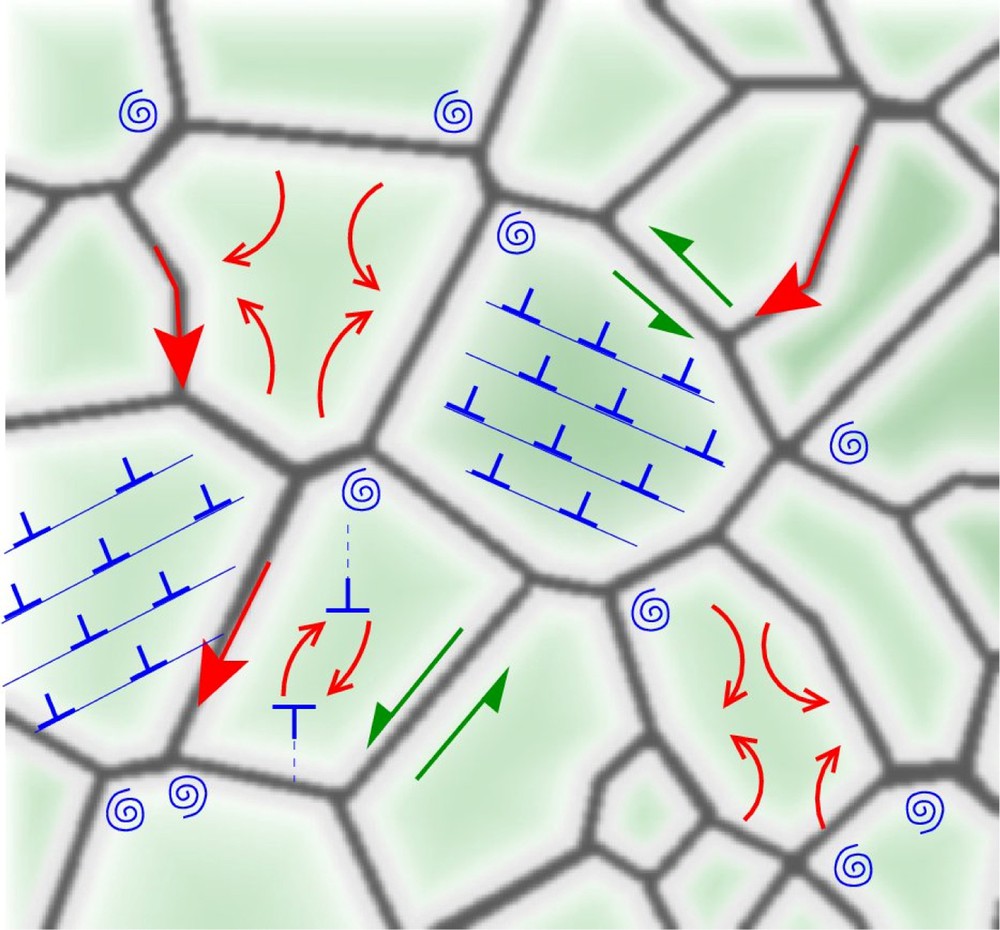

The plasticity of olivine-rich rocks constraints that of Earth's upper mantle. Consequently, there has been considerable effort to quantify olivine aggregate rheology in terms of flow laws that can be implemented in geodynamical models for mantle thermal convection. Experimental studies investigated the effects of temperature and stress (see review in Hirth and Kohlstedt, 2003), pressure (e.g., Bollinger et al., 2013; Durham et al., 2009; Hilairet et al., 2012), fluid fugacities (e.g., Keefner et al., 2011; Kohlstedt, 2006; Ohuchi et al., 2017), grain size (Warren and Hirth, 2006), lattice-preferred orientations (e.g., Hansen et al., 2013), and melt fractions (e.g., Hirth and Kohlstedt, 1995). The traditional view is to assign one dominant deformation mechanism to given deformation conditions (Frost and Ashby, 1982) and implement the flow law with specific dependences on temperature, stress, or grain size. At the microscopic scale, however, olivine aggregate plasticity involves numerous mechanisms operating concurrently, within the grains and at grain-boundary (Fig. 1). To this day, the fundamental question of the amount of strain accommodated in the mantle through grain-to-grain interactions versus that accommodated within the grain remains unanswered.

Schematics of mechanisms accommodating strain in olivine aggregates: dislocations (blue corners) glide, cross slip and climb within grains, disclinations [blue spirals, Cordier et al. (2014)] mostly active near grain boundaries, ionic diffusion (red arrows) occurring at grain interfaces (Cobble diffusion) or within the grains (Nabarro–Herring diffusion, dislocation climb), and grain-boundary sliding (green arrows, see Hansen et al., 2011), which also involves diffusion and can be assisted by dislocations. Other mechanisms that do not accommodate strain, such as grain-boundary migration or recrystallization, also assist olivine deformation. Masquer

Schematics of mechanisms accommodating strain in olivine aggregates: dislocations (blue corners) glide, cross slip and climb within grains, disclinations [blue spirals, Cordier et al. (2014)] mostly active near grain boundaries, ionic diffusion (red arrows) occurring at grain interfaces (Cobble ... Lire la suite

Strain accommodation at grain boundaries has been attributed to several distinct mechanisms. A model for the deformation of aggregates by grain-boundary diffusion was introduced by Coble (1963) to explain the high-temperature plasticity of alumina. Coble creep requires the rearrangement of grain interfaces by grain-boundary sliding (GBS). The corresponding flow law exhibits a linear dependence on stress and a strong inverse dependence on grain size (d), theoretically to the power p = −3. For persistently small grain sizes – when grain growth is, for example, impeded by Zener pinning – Coble creep may contribute to superplastic flow, which has been characterized at room pressure in olivine-rich aggregates (e.g., Hiraga et al., 2010). Grain-boundary sliding can also be assisted by dislocation motions within grains, which contribute to relax stress concentration at triple junctions. This mechanism, called dislocation-assisted grain-boundary sliding (disGBS), has been observed at low pressure in olivine (Hansen et al., 2011; Hirth and Kohlstedt, 2003). It is characterized by a strain rate depending strongly on stress, typically to the power n ∼ 3, with an inverse dependence on grain size to a power p within [−2, −0.6]. Other deformation mechanisms, which do not exist in single crystals, accommodate strain in olivine aggregates. Motions of disclinations – defects identified along grain boundaries in olivine (Cordier et al., 2014) – can accommodate strain. Furthermore, interactions between grains, in materials with limited number of intracrystalline deformation mechanisms, generate locally high stress concentrations (e.g., Castelnau et al., 2008). In materials with anisotropic elastic and plastic properties such as olivine, this may promote high stress and strain transmission patterns percolating throughout the aggregates (Burnley, 2013). Conversely, the stress field associated with single crystal deformation can only be relaxed by intracrystalline deformation mechanisms, such as dislocation motions (glide, climb and cross slip) and intracrystalline diffusion (e.g., Nabarro–Herring diffusion).

Recently, Tielke et al. (2016) compared olivine single crystal and aggregate high-temperature rheology at low pressure, and quantified the contribution of both intracrystalline and intergranular mechanisms to the aggregate strain. They determine that olivine aggregates deform up to 4.6 times faster than what would be expected assuming only intracrystalline plasticity; the latter's contribution to strain rate was calculated from micromechanical modeling of dislocations activity. Following a similar approach, we here compare olivine single crystal and aggregate high-temperature plasticity, as measured experimentally at the high-pressures representative of mantle conditions. We demonstrate that grain-to-grain interactions significantly contribute to accommodating strain in experiments. Extrapolation to mantle stress conditions along geotherms suggests that intergranular plasticity may also dominate upper mantle plasticity.

2 Methods intracrystalline vs. intergranular plasticity

Comparing aggregates and single crystal deformation data allows quantifying the strain rate contributions of intergranular deformation mechanisms. Assuming that intracrystalline (IC) and intergranular (IG) mechanisms operate concurrently, we have:

| (1) |

| (2) |

It should range from 1, when all the aggregate strain is accommodated within the grains, to +∞, when the strain is fully accommodated through grain-to-grain deformation processes. Values for

a: aggregate strain rate

a: aggregate strain rate

We used

| (3) |

3 Results aggregate strain rate

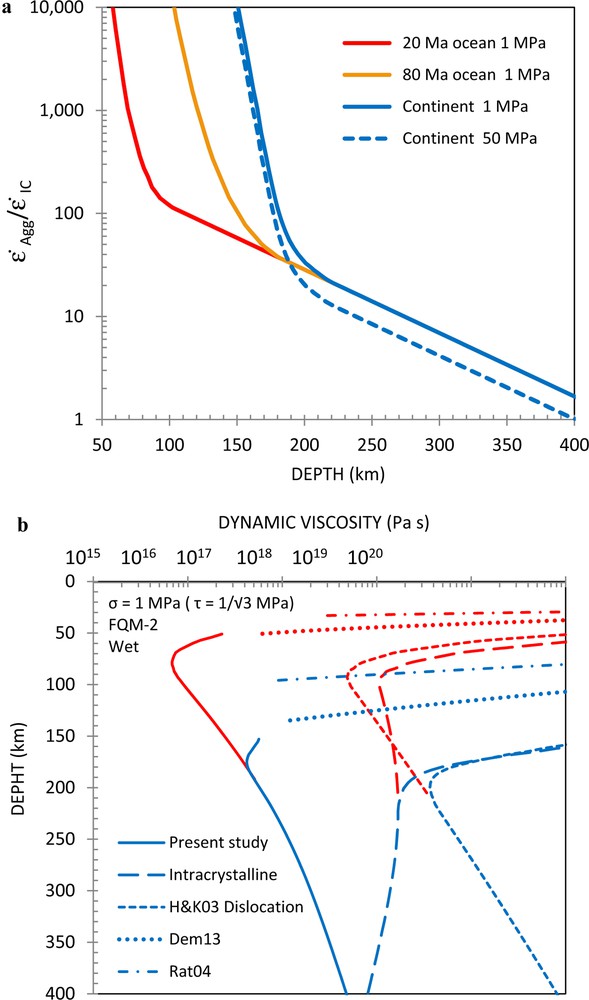

Fig. 2a shows the aggregate strain rate

Fig. 2b shows

The contribution of grain-to-grain deformation processes to the aggregate strain also decreases with temperature (Fig. 2a and b). This effect may result from a combination of factors, such as an increasing aggregate grain size with temperature, i.e. a decreasing grain-boundary surface/bulk volume ratio favoring intracrystalline deformation mechanisms, an increasing activity of disclinations with decreasing T favoring intergranular plasticity, higher stress and strain concentrations near grain boundaries at lower T, or a more effective stress percolation at moderate T (Burnley, 2013) promoting high-strain networks throughout the aggregates, accounted here for as intergranular strain.

A linear fit through

| (4) |

| (5) |

4 Discussion extrapolation to mantle conditions

Fig. 3a shows

a: ratio of the aggregate strain rate by the intracrystalline strain rate

a: ratio of the aggregate strain rate by the intracrystalline strain rate

Fig. 3b shows the viscosity of olivine aggregate along oceanic (20 Ma, red curves) and continental (blue curves) geotherms, as calculated using the composite flow law of Eq. (5) for a differential stress of 1 MPa. Wet conditions are assumed when using Eq. (5), as well as for plotting Hirth and Kohlstedt (2003) dislocation creep flow law with hydroxyl content COH = 300 ppm H/Si. The intracrystalline strain rate calculated from Eq. (3) is shown for comparison, together with two low-temperature flow laws (Demouchy et al., 2013; Raterron et al., 2004). In both contexts, the composite flow law in Eq. (5) leads to viscosities about two orders of magnitude lower than those calculated using Hirth and Kohlstedt's dislocation creep flow law. Interestingly, in the shallow (cold) upper mantle, the composite flow law of Eq. (5) is in relatively good agreement with the low-temperature flow laws reported for olivine, thus captures the change in rheology between high-temperature and low-temperature plasticity. Changing the differential stress to 50 MPa does not significantly affect these results (Supplementary Information, Figure S2). At deeper depths (i.e. 400 km), the difference between the predictions of Eq. (5) and the dislocation creep law of Hirth and Kohlstedt (2003) is due to the pressure-induced change of dominant slip system in olivine (Raterron et al., 2012).

It should be emphasized here that polycristalline specimens in high-pressure experiments have small grain sizes, typically ranging from 1 to 50 μm, which increases significantly their surface versus volume ratio when compared to that of mantle rocks with estimated grain sizes ranging from tenths of millimetre to centimetres. This enhances grain-to-grain interactions, hence intergranular plasticity, in laboratory specimens and may artificially lower their strength with respect to that of mantle rocks. The results reported here (Eq. (5) and Fig. 2) may, thus, significantly overestimate how much strain can be accomodated by grain-to-grain interactions in the coarse-grain mantle. However, our results may apply more directly in the context of mantle shear zones, where grain size reduction weakens sheared peridotites (Skemer et al., 2011; Warren and Hirth, 2006).

5 Concluding remarks

According to our results and extrapolation, we conclude that olivine strain is mostly accommodated by deformation mechanisms involving grain-to-grain interactions at mantle pressures and temperatures, which results in a much weaker strength than that obtained when combining single crystal dislocation creep flow laws. Such a phenomenon was recently observed at low pressure (Tielke et al., 2016), but is much more marked at high-pressure where intergranular plasticity largely dominate deformation.

Uncertainties remain regarding the additional deformation mechanisms, present in aggregates and absent in single crystals, responsible for the measured low strength of aggregates with respect to that of single crystals. Several candidate mechanisms are mentioned in the introduction, such as disclinations, grain-boundary sliding, stress/strain percolation, etc., but our analysis does not allow us to favor one over another.

Furthermore, the empirical model presented here is extracted from deformation experiments carried out at high differential stresses on aggregates with small grain sizes compared to mantle conditions where stresses are much lower and grain sizes larger. Further investigation is necessary to quantify the effects of increasing grain size and decreasing stress on the parameters in Eq. (4). As mentioned above, one may speculate that, due to the larger grain sizes, intracrystalline mechanisms may accommodate more strain in the Earth's mantle than in experiments and, hence, reduce the effect of grain-to-grain interactions highlighted here. Another source of discrepancy when extrapolating the present results to mantle processes is the presence of secondary phases such as pyroxenes, garnet, and possibly partial melts in mantle peridotites, which are absent in the present laboratory specimens.

Keeping in mind the above reservations, let us however emphasize that olivine classical flow laws, whether assuming dislocation or diffusion creep, fail to explain the fast surface displacement observed by GPS after large earthquakes (e.g., Freed et al., 2010), which requires a much weaker strength for the lithosphere as the one we propose here. Also, the particularly deep weakening predicted here along a continental geotherm may provide an explanation for the elusiveness of the lithosphere – asthenosphere boundary beneath cratons (e.g., Eaton et al., 2009), since it should reduce the lithosphere – asthenosphere viscosity contrast. We thus conclude that grain-to-grain interactions are an important component of olivine plasticity at mantle pressures, and may likely contribute to the weakening of the Earth's upper mantle with respect to that calculated from classical flow laws for olivine.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the “Agence nationale de la recherche” (ANR) Grant BLAN08-2_343541 “Mantle Rheology”. We thank two anonymous reviewers for their thoughtful insights, which helped improving the original manuscript. Part of the work was carried out while PR was serving at the National Science Foundation. Any opinion, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.