1 Introduction

Antimicrobial peptides are polypeptides of fewer than 100 amino acids, found in host defense settings, and exhibiting antimicrobial activity at physiologic ambient conditions and peptide concentrations. Two large families of antimicrobial peptides, defensins [1] and cathelicidins [2], are abundant and widely distributed in mammalian epithelia and phagocytes. Other mammalian antimicrobial peptides, including histatins [3], dermcidin [4], and ‘anionic peptides’ [5] have a more restricted tissue and animal species distribution. Many more families of antimicrobial peptides are found in invertebrates [6]. Individual antimicrobial peptides have been implicated in antimicrobial activity of phagocytes, inflammatory body fluids or epithelial secretions. Although this review is primarily focused on mammalian defensins, I will use key studies of other antimicrobial peptides to illustrate more general principles of antimicrobial peptide function.

2 Antimicrobial peptides: activities and their mechanisms

2.1 Activity

Several model antimicrobial peptides, including magainins from frog skin, tachyplesins and polyphemusins from horseshoe crab hemocytes and protegrins from pig leukocytes, have been subjected to detailed studies because of their structural simplicity, small size (16–22 amino acids) and potential pharmaceutical applications. These peptides exhibit a broad spectrum of antimicrobial activity that includes gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria [7,8] and fungi [3], at similar concentrations (in the range of 1–10 μg ml−1) and under similar testing conditions to those used for other antimicrobial pharmaceuticals. Protegrins and tachyplesins are also active against some enveloped viruses [9]. The antimicrobial activity of these peptides is remarkably specific, with little cytotoxicity to mammalian cells even at concentrations ten-fold or more higher than those required for antimicrobial activity [10].

The structurally more complex mammalian defensins (29–50 amino acids) are also active against bacteria and fungi, especially when tested under low ionic strength conditions [11–13] and with low concentrations of divalent cations, plasma proteins or other interfering substances. Under these optimal conditions, antimicrobial activity is observed at concentrations as low as 1–10 μg ml−1 (low μM). Increasing concentrations of salts and plasma proteins competitively inhibit the antimicrobial activity of defensins, in a manner that is dependent on both the specific defensin and its microbial target. At higher concentrations, some defensins are cytotoxic to mammalian cells [14–16]. Certain enveloped viruses are also inactivated by defensins [17,18]. In general, metabolically active bacteria are much more sensitive to defensins then bacteria made inactive by nutrient deprivation or metabolic inhibitors.

2.2 Mechanisms of antimicrobial activity

Antimicrobial peptides are almost always cationic and amphipathic (i.e., they are positively-charged and contain both hydrophobic and hydrophilic domains). This allows them to interact with biological membranes in such a way that the cationic domains are near the negatively charged phospholipid headgroups, while the hydrophobic portions of the peptide are submerged within the hydrophobic interior of the membrane composed of fatty acid chains. The simplest antimicrobial peptides, typified by magainins, form an alpha helix, with cationic and hydrophobic side chains radially arranged on opposite surfaces of the helix. Another simple structure is the beta-sheet hairpin (e.g., protegrins, tachyplesins, polyphemusins) containing positively charged clusters separated by hydrophobic regions. The interactions between simple antimicrobial peptides and model membranes have been extensively explored [19–21]. In these systems, there is strong evidence of a two-stage interaction between the peptides and the membranes. During the first stage, the peptides, attracted to the membrane by electrostatic forces, form a carpet within but near the surface of the membrane, with the long axes of the peptides parallel to the membrane. As more and more peptide molecules accumulate, the membrane becomes distorted and strained, favoring a transition to an energetically more favorable state where the peptides are oriented with their long axes across the membrane, creating toroidal wormholes in the membrane or otherwise disrupting membrane integrity. These interactions are favored by the presence of anionic phospholipids in the membrane and inhibited by neutral phospholipids or cholesterol. Anionic phospholipids are characteristic of bacteria but neutral phospholipids and cholesterol are found in animal cell membranes, explaining the preferential effect of antimicrobial peptides on bacterial targets.

Structurally more complex antimicrobial peptides are thought to act by similar mechanisms. Model bacteria (E. coli ML-35) [22] and mammalian cell line K562 [16] treated by defensins become permeable to small molecules (small sugars and trypan respectively). In bacteria, permeabilization coincides with inhibition of RNA, DNA and protein synthesis and decreased bacterial viability, as assessed by the colony-forming assay. In the model cell line, the permeabilized cells can be rescued for up to 1 h by removing the defensin, and there is evidence that additional intracellular sites of action contribute to cell death [16].

In experiments with artificial phospholipid membranes, defensins NP-1 (rabbit) and HNP-1 (human) formed voltage-dependent channels, requiring negative potential on the membrane side opposite to where defensins where applied [23]. This is consistent with the idea that the insertion of defensin molecules into the membrane is dependent on electrical forces acting on the positively charged defensin molecule. The effect of these forces is evident even when no transmembrane potential is applied externally. Unlike another cationic peptide, melittin, that indiscriminately permeabilized vesicles composed of neutral or anionic phospholipids, defensins were much more active against vesicles that included negatively charged phospholipids [24]. In general, the activity of defensins against vesicles was diminished in the presence of increased salt concentrations, supporting the importance of electrostatic forces between the anionic phospholipids headgroups and the cationic defensins. Interestingly, the permeabilizing activity of the most highly cationic defensins was not inhibited by moderate salt concentrations, indicating that electrostatic screening by salt ions may not have been complete. In other experiments, large unilamellar vesicles composed of the negatively charged phospholipid palmitoyloleoylphosphatidylglycerol were permeabilized by human defensin HNP-2 but the addition of neutral phospholipids to the lipid mix inhibited both defensin binding and permeabilization [25]. Using a very different methodology, the importance of anionic phospholipids for the membrane interactions with defensins was clearly shown by calorimetric measurements of the effects of defensins on phase transitions in membranes [26]. These studies suggest that defensin molecules enter into the membrane under the influence of both externally applied and local electric fields.

It is much less certain what happens once the defensin molecules are in the membrane. The observed leakage of dye markers from liposomes implies that pores (we use this term to refer to any ion or water-permeable structure within the membrane) form either stably or transiently. For some defensins, the release of internal markers from each vesicle occurred in all or none fashion [25], indicating that the pores formed were stable. By measuring the ability of pores to allow the passage of marker molecules of various sizes, the pore diameter was estimated at 25 Å. The authors proposed a model of a defensin pore – a hexamer of dimers – that generates an opening of the observed size. However, stable pore formation is not the only mechanism of defensin interaction with membranes. The more cationic rabbit defensins induced a partial release of markers from individual vesicles indicating that the pores formed were not stable. It is possible that electrostatic repulsion between the highly cationic rabbit defensin molecules destabilizes the pores.

3 Vertebrate defensins

3.1 The structure of defensins

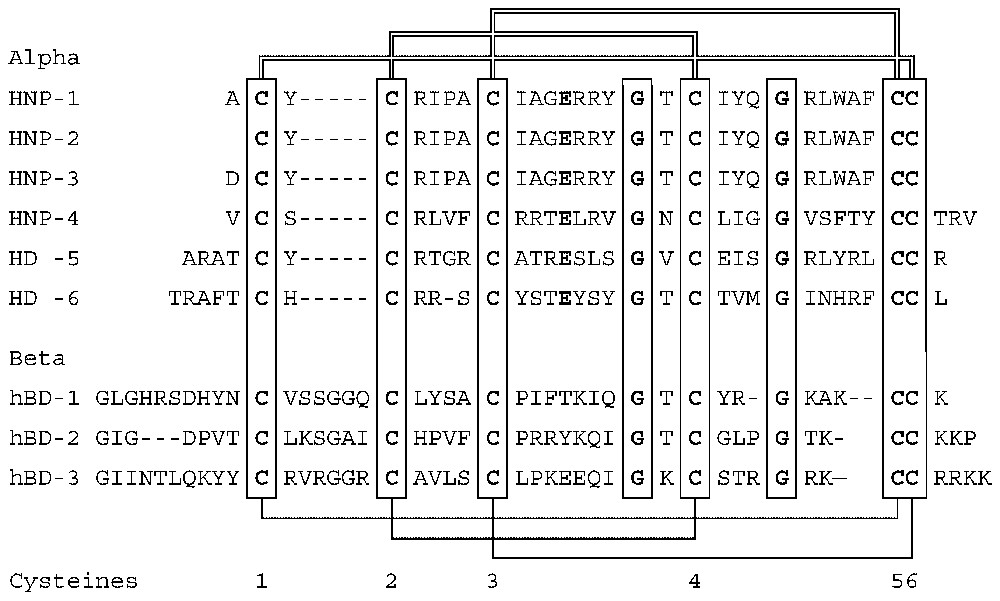

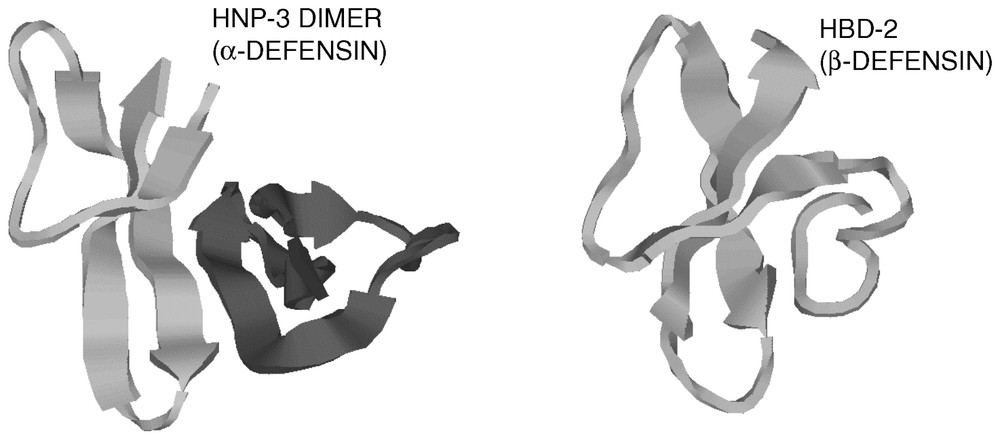

Defensins [1,27] are a family of vertebrate antimicrobial peptides with a characteristic β-sheet rich fold and a framework of six disulfide-linked cysteines [1,27]. The two major defensin subfamilies, α- and β-defensins, differ somewhat in cysteine spacing and connectivity (Fig. 1). Several structures representative of these two families have been solved by 2D-NMR and by X-ray crystallography [28–35]. Both α- and β-defensins consist of a triple stranded β-sheet with a distinctive ‘defensin’ fold (Fig. 2). Whereas in α-defensins the six cysteines are linked in the 1–6, 2–4, 3–5 pattern [36], in β-defensins the pattern is 1–5, 2–4, 3–6 [37]. Because cysteines 5 and 6 are adjacent in both types of defensins, this difference in connectivity does not substantially alter the structure [33]. More recently, another structurally very distinct subfamily of θ-defensins [38] has been identified in the rhesus macaque monkey leukocytes. The mature θ-defensin peptides arise by an as yet uncharacterized process that generates a cyclic peptide by splicing and cyclization from two 9-amino acid segments of α-defensin-like precursor peptides. Based on their adjacent chromosomal location and similar peptide precursor and gene structure it is highly likely that all vertebrate defensins arose from a common gene precursor [39]. Antimicrobial peptides from invertebrates and plants containing six or eight cysteines in disulfide linkage have also been called defensins (e.g., insect and plant defensins). Their evolutionary relationship to vertebrate defensins is uncertain.

Amino acid sequences and connectivities of human defensin peptides.

Cartoon diagrams of a human α-defensin and a human β-defensin. Note the similarity of the folding patterns of the monomers.

3.2 Distribution of defensins

During studies of the antimicrobial activity of rabbit and guinea pig leukocyte lysates in the 1960s, the peptides originally attracted attention because of their abundance and broad spectrum of antimicrobial activity [40]. Subsequent technical developments facilitated their isolation and detailed chemical characterization [11,41,42]. Their discovery in human leukocytes [1,27] suggested that the peptides were widely distributed in nature. After their isolation from leukocytes, defensins were found in other host defense settings where they were produced by epithelial cells [43,44]. Typical defensin peptides have been found in all mammals that have been carefully examined, as well as in chickens and turkeys [45–48]. Defensin-like peptides (growth arresting peptide [49] and crotamines) have been also isolated from snake venom where they may represent an adaptation of epithelial host defense peptides for efficacy against larger predators.

Defensins are found predominantly in cells and tissues involved in host defense against microbial infections. The highest concentrations of defensins (>10 mg ml−1) are found in granules, the storage organelles of leukocytes [1,50]. When leukocytes ingest microbes into phagocytic vacuoles, the granules fuse to these vacuoles and deliver their contents onto the target microbe. Since there is little free space in phagocytic vacuoles the microbe is exposed to minimally diluted granule material. Similarly, Paneth cells, specialized host defense cells of the small intestine, contain secretory granules that they release into narrow intestinal pits, called crypts. The concentration of defensins in the crypts may also reach >10 mg ml−1 [51]. Various epithelia produce defensins, in some cases constitutively [52], in others in response to infection [53]. The average concentration of defensins in these epithelia is in the 10–100-μg ml−1 range [53,54], but because the peptides are not evenly distributed the local concentrations could be much higher.

Patterns of tissue distribution are quite variable even when closely related species are compared. Among rodents, mice lack leukocyte defensins [55], rats have them [56] and both species have numerous Paneth-cell defensins and epithelial β-defensins. In some cases, defensin expression appears to be induced by a combination of a specific cell type and tissue environment. Inflammatory macrophages are leukocytes that arise by differentiation from circulating blood monocytes, under the influence of local tissue signals. In the rabbit, alveolar (lung) macrophages have abundant α-defensins in amounts comparable to rabbit neutrophils but defensins are absent from their peritoneal macrophages [57]. Although defensin expression in monocytes, macrophages and lymphocytes of some mammals can be detected by highly sensitive techniques [58–60], high levels of defensins in macrophages have only been documented in rabbits. We suspect that these peculiarities of the pattern of expression of defensins in certain animal species could be related to the evolutionary pressure from species-specific pathogens.

3.3 Microbial resistance to defensins

Specific mechanisms that confer increased bacterial resistance to defensins have been identified by insertional mutagenesis. Disruption of the two-component transcriptional regulator phoP–phoQ increases the sensitivity of Salmonella to defensins and other cationic peptides [61–64]. PhoP–phoQ directly regulates multiple genes involved in resistance to cationic peptides and also exerts some of its activity by modulating a second two-component regulator, PmrA–PmrB. The function of the downstream genes includes covalent modification of lipopolysaccharides that decreases their affinity for cationic peptides [65] and expression of membrane proteases that degrade cationic peptides [66]. In Neisseria gonorrhoeae, a bacterium naturally quite resistant to defensins, the energy-dependent efflux system mtr increases the resistance to protegrins, potent mini defensin-like peptides of pig neutrophils [67]. In Staphylococci, the disruption of either of two genes, dlt or MprF, increases the sensitivity of the bacteria to defensins [68,69]. The gene dlt is required for covalent modification of cell wall teichoic acid by alanine, and MprF is necessary for covalent modification of membrane phosphatidylglycerol with L-lysine. These modifications probably act by decreasing the negative charge of the cell wall and bacterial membrane respectively and diminishing their attraction for the cationic defensins. Homologues of these resistance genes have been identified in many bacterial species indicating that these mechanisms may be widespread.

3.4 Other activities of defensins

Various defensins have been reported to have chemotactic activity for monocytes, T-lymphocytes and dendritic cells [70–73]. In the case of human β-defensins 1 and 2, which attract memory T-cells and immature dendritic cells, the chemoattractant activity may be due to defensin binding to the chemokine receptor CCR6 [72]. Although the physiologic significance of this interaction has not yet been demonstrated, the high concentrations of HBD-2 in inflamed skin make it likely that this defensin could compete effectively with the natural chemokine ligand (variously named CCL20, LARC, MIP-3α) despite the higher affinity of the latter for the CCR6 receptor. Recent structural analysis of CCL20 pointed out remarkable similarities to HBD-2 in the putative receptor-binding region of CCL20. The role of this region in the chemotactic activity of HBD-2 needs to be confirmed by mutating the amino acid residues suspected in its interaction with CCR6. Human neutrophil defensins HNP1–3 have been reported to be chemotactic for monocytes [70], naı̈ve T-cells and immature dendritic cells [73] but a specific receptor has not yet been identified.

Some defensins (called ‘corticostatins’) [74–76] oppose the action of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) by binding to ACTH receptor [77] without activating it. Although such activity would inhibit the production of the immunosuppressive hormone cortisol, and could thus be useful in responding to infections, the physiologic role of this in vitro interaction has not yet been demonstrated.

Yet another reported activity of some defensins is their ability to activate nifedipine-sensitive calcium channels in mammalian cells [78,79]. This effect required only nanomolar concentrations of defensins. The structural basis of this effect is not understood. Certain mouse Paneth cell defensins (cryptdins) activate chloride secretion most likely by forming channels in the apical membrane of epithelial cells [80,81]. This activity is limited to a subset of cryptdins, and its structural basis is not yet known.

Most recently, several peptides genetically and structurally related to defensins have been found in the male reproductive tract, and in particular in the epididymis [82,83]. While some peptides expressed in the male reproductive tract are typical defensins also found in other organs [84], most are larger peptides from genes that undergo complex alternative splicing. These peptides could have an important role in the host defense of germ cells as well as in the regulation of sperm maturation.

3.5 Defensin biosynthetic pathways

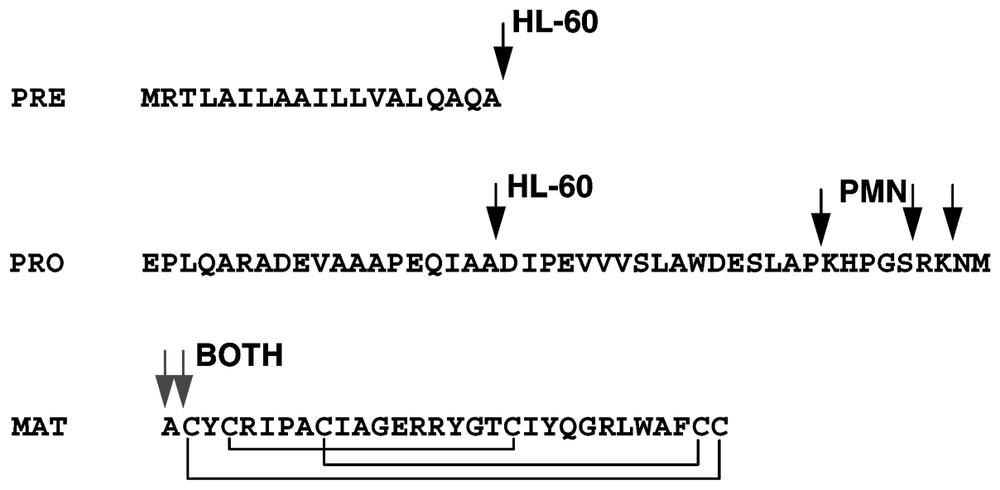

At least eight genes encoding α- and β-defensins are located in a cluster on chromosome 8p23 [39,85–88] and recent studies document additional defensin clusters with multiple transcribed defensin genes [89]. Mapping of the 8p23 cluster has been problematic, probably due to its polymorphic nature, with individuals and their chromosomes differing in the number of copies of individual defensin genes [90,91]. Alpha-defensins are generally encoded as a tripartite prepropeptide sequence, wherein a 90–100 amino acid precursor contains an N-terminal ∼19 amino signal sequence, ∼45 amino acid anionic propiece and a C-terminal ∼30 amino acid mature cationic defensin [92] (Fig. 3). In many cases, the charge of the propiece and the mature defensin approximately balance [93], and this arrangement may be important for folding and/or to prevent intracellular interactions with membranes [94,95]. For neutrophil α-defensins, synthesis takes place in the bone marrow, in neutrophil precursor cells, promyelocytes [96–98]. Mature neutrophils circulating in blood or found in inflamed tissues contain large amounts of defensins but are no longer synthesizing the peptides or their mRNAs. During defensin synthesis in myeloid cell lines, the signal sequence is rapidly removed but the subsequent proteolytic processing to mature defensins takes many hours, and the final proteolytic cleavage may take place in maturing granules [99]. The process is very efficient so that only small amounts of partially processed intermediates are detectable in mature neutrophils [100]. In the case of murine Paneth cell defensins (cryptdins), the metalloproteinase matrilysin (MMP-7) is required for processing since mice with homozygous disruption of the matrilysin gene do not process Paneth-cell defensin past the removal of the signal sequence. The structure of β-defensin precursors is simpler, consisting of a signal sequence, a short or no propiece and the mature defensin peptide at the C-terminus. The lack of anionic propiece in β-defensin precursors contrasts with the relatively large anionic propiece in α-defensin precursors, a difference that has not been satisfactorily explained.

Processing of the α-defensins HNP1-3 as deduced from studies in HL-60 myeloid leukemia cell line and in mature PMN. Arrows indicate the forms detected by direct analysis or radiosequencing. The segments are denoted as PRE (signal sequence), PRO (propiece) and MAT (mature peptide).

3.6 Amino acid sequence and composition of defensins

The amino acid sequences of mature defensins are highly variable, except for the conservation of the cystine framework (Fig. 3) in each defensin subfamily. Clusters of positively charged amino acids are characteristic of most α- and β-defensins, but their specific distribution within the defensin molecule is variable. In leukocytes and in Paneth cells of the small intestine, defensins are stored in granules, subcellular storage organelles rich in negatively charged glycosaminoglycans. With the exception of chicken gallinacins, these α- and β-defensins contain arginine as the predominant cationic amino acid. In contrast, β-defensins that are secreted from epithelial cells contain similar amounts of arginine and lysine. The preferential use of arginine in defensins stored in granules may reflect the constrains imposed by packing defensin molecules into the glycosaminoglycan matrix of granules [101,102].

3.7 Structure-function considerations

A unitary hypothesis of how defensins permeabilize membranes is complicated by the marked differences in net charge, amino acid sequence and quaternary structure (monomers vs. dimers) among the defensins. It is possible that these differences evolved so that various defensins can target different types of bacteria with differing structures of cell walls and membranes. Further complexity is introduced by the flexibility of the basic amino acid side chains that permit a variety of potential spatial interactions with phospholipids headgroups or water. Although the interactions of defensins with membranes have been modeled [25] there are only rudimentary experimental data on the structure of the defensin complexes within the membrane. Further work in this area is clearly needed since the considerable progress in understanding the interactions of amphipathic α-helical peptides with membranes does not readily translate to defensins, which are larger, more complicated and more variable structures.

3.8 Functions of defensins in vivo

When initially proposed [1], the name ‘defensins’ represented a risky conjecture since it was largely based on in vitro antimicrobial activity and the peptides' location in neutrophils, the prototypic host defense cells. Since then, experiments with transgenic mice have largely supported the idea that the dominant function of defensins is antimicrobial. Mice with homozygous disruption of the matrilysin gene failed to activate intestinal prodefensins to defensins, and were more susceptible to infection with Salmonella typhimurium, requiring an eight-fold lower oral dose for 50% mortality [103]. After oral administration of E. coli test bacteria, the counts of viable bacteria were similar in the proximal intestine of wild-type and matrilysin-knockout mice, but the wild-type mice had lower bacterial counts in the mid- and distal small intestine, where Paneth cells are present at higher density. In vitro, segments of intestine from wild-type mice contained and secreted more antimicrobial activity than those of matrilysin knockout mice [51]. Moreover, in wild-type mice the antimicrobial activity could be largely neutralized by anti-defensin antibody, indicating that defensins were responsible for much of the activity. Taken together, these experiments provided important circumstantial evidence for the protective role of defensins in the early stages of infection.

More recently, a gain-of-function model was reported, in transgenic mice expressing the human Paneth cell defensin gene HD-5 [104]. HD-5 compared to murine Paneth cell defensins has greater antibacterial potency against the murine pathogen Salmonella typhimurium. HD-5 mice were fully protected against death from Salmonella typhimurium infection at oral doses that killed all of the wild-type mice. Protection from infection was seen early, already at 6 hours, and correlated with lower S. typhimurium counts in the intestinal lumen, and prevention of the spread of infection to other organs. The effect of transgenic defensin was local, since intraperitoneal inoculation that bypassed the intestine caused equal mortality in the transgenic and wild-type strains. The intestinal lumen-specific effects of transgenic defensin early in the course of infection provide the strongest evidence to date that defensins act as locally secreted antibiotics.

Mice deficient in murine β-defensin-1 show only very mild defects [105,106] in host defense of the urinary and respiratory tracts, most likely due to the redundancy amongst mouse defensin genes. Unlike the many defensin genes present in the mouse genome, there is only one, or at most very few murine cathelicidins (the number depends on how the family is defined). The murine cathelicidin (cathelin-related antimicrobial peptide, CRAMP) is similar to its human ortholog, LL-37, and both are expressed in predominantly in neutrophils. Mice with homozygous disruption of the CRAMP gene showed diminished resistance to skin infection with group A Streptococcus [107]. Taken together, data from loss of function models support a host defense role for cathelicidins and defensins.

4 Conclusions and future prospects

Evidence is continuing to accumulate that vertebrate defensins function as antimicrobial effectors of innate immunity. In addition, some defensins may have also evolved additional roles in host defense, inflammation and even reproduction. Some of the many structurally and genetically diverse antimicrobial peptides in animals and plants should provide useful templates for the development of new antibiotics.