1 Introduction

Surfactants are key components in emulsion polymerisation since they control the nucleation process as well as the stabilization of the polymer particles during the polymerization and storage of the latex. However, surfactants may have negative effects on the properties of emulsion polymerisation latexes, mainly caused by desorption of the surfactant from the polymer particles surface. Indeed, it has been reported that the migration of the unbounded surfactant through the film can modify adhesion, water sensitivity and the optical properties [1–7]. A solution to these problems is the use of polymerisable surfactants, referred as surfmers. The surfmers remain covalently bonded to the polymer, preventing migration during storage and film formation.

In order to be effective, the surfmers must react in such a way that for the main part of the process the surfmer conversion should be low (to avoid surfmer burying and hence to maximize the amount of surfmer present at the surface of the polymer particles) and towards the end of the reaction high surfmer conversion should be achieved (to avoid surfmer migration during film formation) [7,8]. These requirements limit the useful range of values of the reactivity ratios of the surfmer/monomers system [8]. In addition, one important variable to control the conversion of a given surfmer is the surfmer addition policy.

In this article, optimal surfmer addition policies were developed for the high solids content emulsion copolymerization of methyl methacrylate (MMA)/butyl acrylate (BA)/acrylic acid (AA). The surfmer used was a non-ionic alkenyl-functional TMMaxemul 5011 (supplied by Uniqema), with a general formula: CH3(CH2)11CH=CH–CxOyHz–PEO–CH3. The goal was to maintain latex stability maximizing the final surfmer conversion. A mathematical model able to describe surfmer polymerisation [9] was used in the optimisation process. The values of the parameters of the model for this process were previously estimated [10].

2 Optimisation of surfmer feed flow rate

2.1 Objective function

The objective function to be minimized should take into account the following aspects:

- • (i) the conversion of the surfmer should be maximum at the end of the process (first term of Eq. 1);

- • (ii) the effective concentration of the surfmer (surfmer that contributes to colloidal stability) per surface area unit should be maximum (second term of Eq. 1);

- • (iii) at any time during the reaction, there should be a minimum amount of surfmer available for the stabilization of the polymer (third term of Eq. 1)

- • (iv) the total amount of surfmer in the formulation is fixed (fourth term in Eq. 1); in this work, the total surfmer used was 3 wt% with respect to the monomer; this quantity was proven experimentally to be enough to stabilize the high solids content acrylic latexes [11].

Therefore, the objective function was as follows:

| (1) |

The values of the weighing factors were inversely proportional to the order of magnitude of the corresponding terms. α2 was varied by a factor of 10 to check the effect of this parameter on the optimisation. The values used are reported in Table 1.

Values of the weighing factors and Ci coefficients used in the objective function

| Coefficient | Value |

| α1 | 0.216 |

| α2 | 3600 and 36 000 |

| C1 | 5.0 × 1011 |

| C2 | 5.0 × 109 |

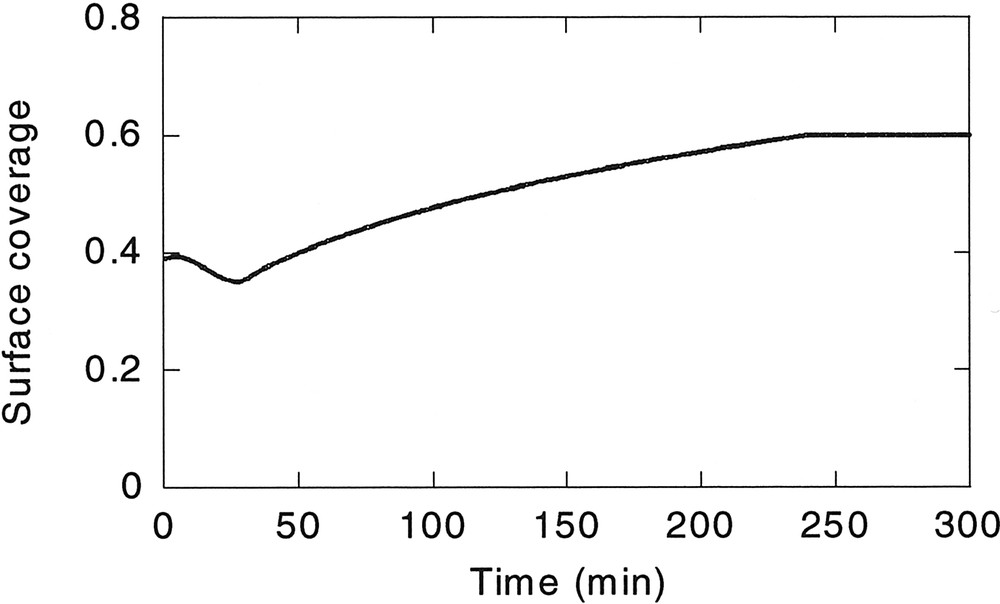

The minimum amount of surfmer required in every moment to stabilize the polymer particles (included in the objective function by means of C1) was calculated by estimating with the mathematical model the surface coverage of a stable latex produced under conditions similar to those of the optimal process (seeded emulsion polymerisation of a MMA/BA/AA: 49/49/2, particle size of the seed: 42.5 nm, 3 wt% of surfmer with respect to the monomers, constant surfmer feeding rate, total feeding time of 4 h, potassium persulfate/sodium metabisulfite as redox initiator system, solids content of 52% – Run 1) [11]. Fig. 1 shows the evolution of the surface coverage for this latex. In addition, the ideal situation with no surfmer burial is also presented. It can be seen that if all the surfmer contributed to stabilization, the surface coverage would be almost 20% at the end of the process. The concentration of surfmer per unit area corresponding to this surface coverage was taken as the reference value for ceff,max (3.5 × 10–11 mol cm–2). On the other hand, when surfmer burial was considered, the minimum surface coverage was between 15% and 14.7%. Since this process yielded stable latex, the lower limit chosen for the surface coverage was 14.7%.

Estimated evolution of the surface coverage for Run 1, with 3 wt% of surfmer [11]. Legend: (——) considering surfmer burial; (----) no surfmer burial considered.

The optimal surfmer addition profiles were determined by minimizing the objective function (Eq. 1), the surfmer feed rates were obtained. For simplicity, the feeding period was divided into six intervals and the feed rate was kept constant within each interval, but it varied between intervals.

Additional constraints took into account in the optimisation were as following.

- • (i) The surfmer feeding time was fixed. Optimisations were performed for two different surfmer feeding times: 4 and 2.5 h. In both cases, the total feeding time for monomers was 4 h.

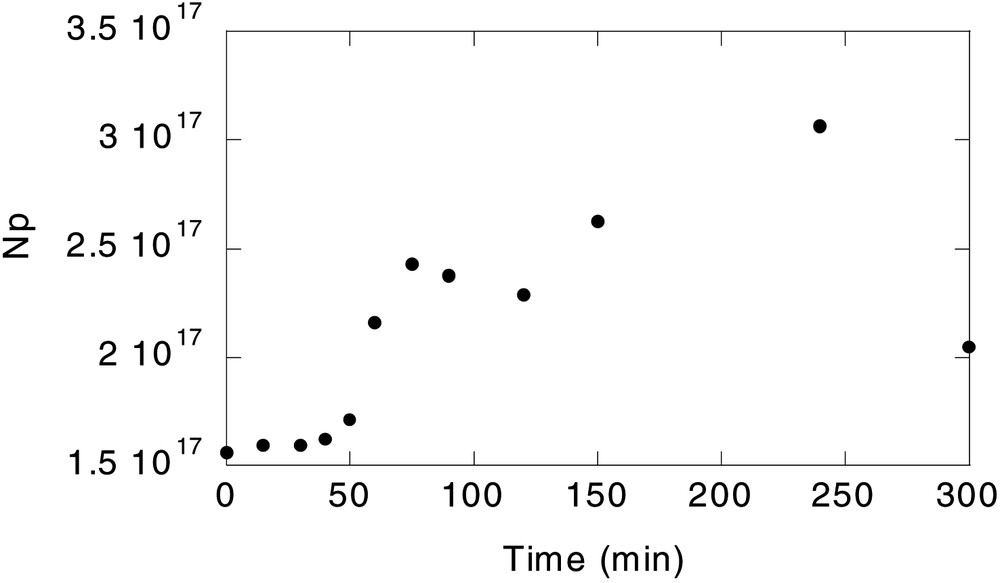

- • (ii) The maximum amount of surfmer fed at any interval was limited, to avoid secondary nucleations. This value was calculated by analysing the minimum surface coverage needed to nucleate new particles. An experiment with 10wt% surfmer was carried out for this purpose. Fig. 2 shows the evolution of the number of particles in this experiment (rest of conditions as in Run 1), and its corresponding surface coverage, estimated with the model is plotted in Fig. 3 . It can be seen that when the surface coverage exceeded 38–40%, new polymer particles were nucleated. Therefore, the maximum surfmer feed rate was fixed to ensure a maximum surface coverage of 38%. This corresponds to a concentration of the surfmer in the aqueous phase of 3.5 × 10–6 M, well below the CMC of the Maxemul (1.8 × 10–4 M), which indicates that homogeneous nucleation was operative.

Evolution of the number of particles (Np) when 10 wt% surfmer is used.

Estimated evolution of the surface coverage when 10 wt% surfmer is used.

2.2 Results of the optimisation

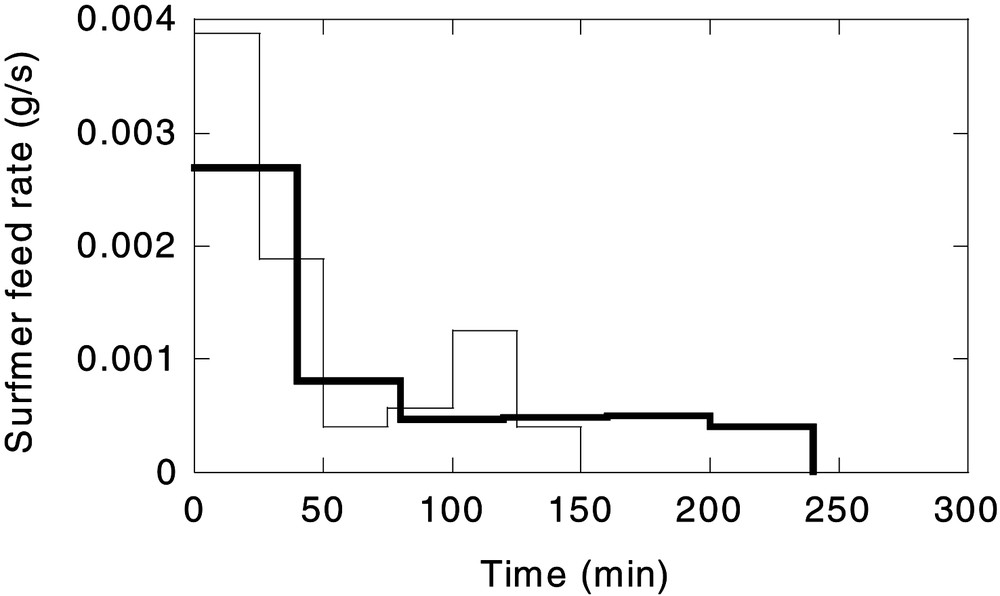

The minimization of the objective function was carried out by using the method developed by Nelder and Mead [12] (DBCPOL subroutine from the Fortran ISML library). Fig. 3 shows the optimal surfmer feed rate calculated for the two surfmer feeding times considered (2.5 and 4 h). The surfmer conversion as well as the percentage of buried surfmer at the end of each process is summarized in Table 2. In this table, the values of this variable in the reference reaction, in which a constant surfmer feeding rate was used (Run 1) are also included.

Comparison of the surfmer performance for different surfmer addition policies

| Reaction | Surfmer addition policy | Surfmer feeding time (h) | Surfmer conversion | Buried surfmer |

| Run 1 | Constant | 4 | 0.58 | 0.20 |

| Run 2 1 | Optimal | 4 | 0.70 | 0.25 |

| Run 22 | Optimal | 4 | 0.70 | 0.25 |

| Run 31 | Optimal | 2.5 | 0.75 | 0.26 |

| Run 32 | Optimal | 2.5 | 0.76 | 0.26 |

Table 2 shows that the final estimated surfmer conversion increased from 58% (in the reference reaction) to about 75% when an optimal surfmer feeding profile was implemented. On the other hand, it was observed that decreasing the feeding time of the surfmer from 4h to 2.5 h, surfmer conversion could increase about 5%, without a significant increase of the amount of surfmer buried. This is significant considering that TMMaxemul 5011 is not a very reactive surfmer because it has an alkenyl double bond.

It was also found that in the studied intervals, the optimisation results did not depend on the weighing factors.

2.3 Experimental check

Two reactions were carried out using the optimal flow rate profiles given in Fig. 4 , keeping the rest of operational variables as in Run 1. These reactions will be referred to as Run 2 (surfmer feeding time of 4 h) and Run 3 (surfmer feeding time of 2.5 h).

Optimal surfmer feed rate. Legend: (——) surfmer feeding rate: 4 h; (——) surfmer feeding rate: 2.5 h

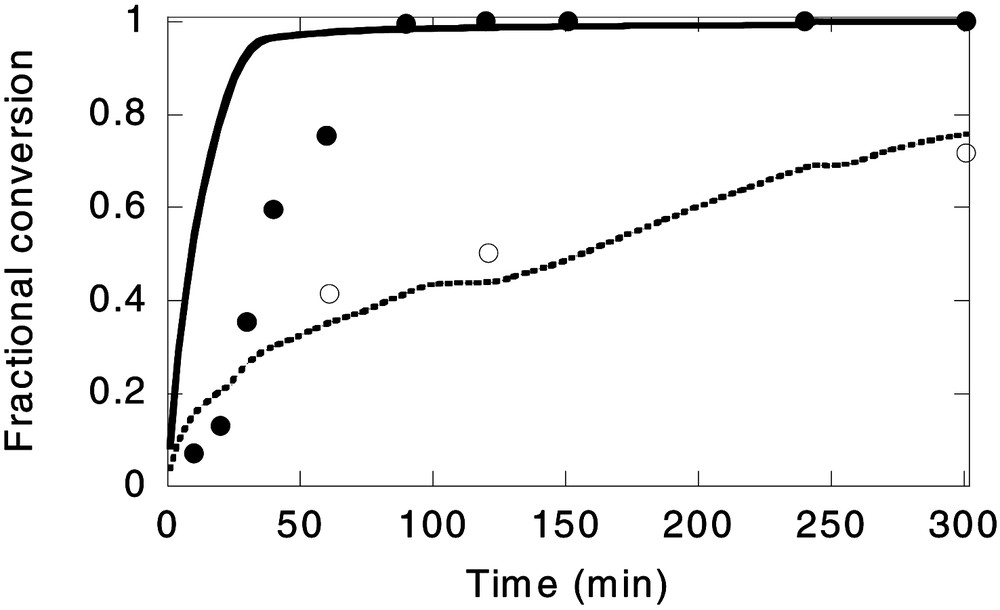

Fig. 5 shows the experimental evolution of the monomer and surfmer conversion for Run 2 as well as the predictions of the model. As it can be seen, surfmer conversion increased up to 69.1%, while in the reference reaction (Run 1, surfmer feed rate constant) only 63.8% was achieved. The colloidal stability was satisfactory as the amount of coagulum obtained was slightly lower than when the surfmer was fed at constant rate (1.48% in Run 2 vs. 1.55% in Run 1).

Experimental data (^) and model prediction (----) for surfmer conversion, and experimental data (●) and model prediction (——) for monomer conversion in Run 2 (surfmer feeding rate: 4 h).

The evolution of surfmer conversion was properly described by the model, but some model mismatch was observed for the monomer conversion at the onset of the process. This may be because at the beginning, a high surfmer feed rate was used. Under these circumstances, the concentration of the surfmer at the surface of the polymer particles was high and could reduce the entry of radicals into the polymer particles [13,14], effect that the model does not take into account. A simpler reason for the low initial monomer conversion is that some inhibition occurred. On the other hand, particle size distribution measurements carried out by means of capillary hydrodynamic fractionation (CHDF), showed that secondary nucleations were not produced. This is somehow expected since the estimated maximum concentration of free surfmer in the aqueous phase was 2.5 × 10–6 M, below the estimated value to avoid secondary nucleations.

Fig. 6 presents the evolution of the monomer and surfmer conversion in Run 3 (surfmer feeding time of 2.5 h), and the predictions of the model. In this case, the final surfmer conversion was 71.7%. The amount of coagulum was similar to that in the reference polymerisation, Run 1 (1.55% in Run 1 and 1.75% in Run 3), and no new nucleation was observed by CHDF. From those results it can be concluded that it is possible to increase the incorporation of the surfmer to the particles keeping the latex stable.

Experimental data (^) and model prediction (----) for surfmer conversion; and experimental data (●) and model prediction (—— ) for monomer conversion in Run 3 (surfmer feeding rate: 2.5 h).

On the other hand, in this run, as occurred in Run 2, the evolution of monomer conversion at the beginning of the process was not as well predicted by the model. This seems to support the hypothesis of a slow radical entry rate at the beginning of the process, although the possibility of inhibition cannot be rejected.

3 Conclusions

The optimisation of the surfmer feed policy was carried out, aiming at obtaining a stable high solids content MMA/BA/AA (49/49/2) latex stabilized with a non-ionic alkenyl functional TMMaxemul 5011 surfmer chemically bound to the polymer. It was observed that, in spite of the relatively low reactivity of the surfmer due to the presence of the alkenyl double bond, using the optimal policy it was possible to increase the surfmer conversion in about 11% (from 58% when constant feed rate is used to 69% with the optimised profile, with a surfmer feeding time of 4 h). In addition, the incorporated surfmer increased until 72% when the surfmer feeding time was reduced to 2.5 h, maintaining the stability of the latex. On the other hand, the experimental results were in good agreement with the predictions of the model, which validate the model used.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Uniqema and The University of the Basque Country (Subvención a Grupos Consolidados) for funding E. Aramendia.