1 Introduction

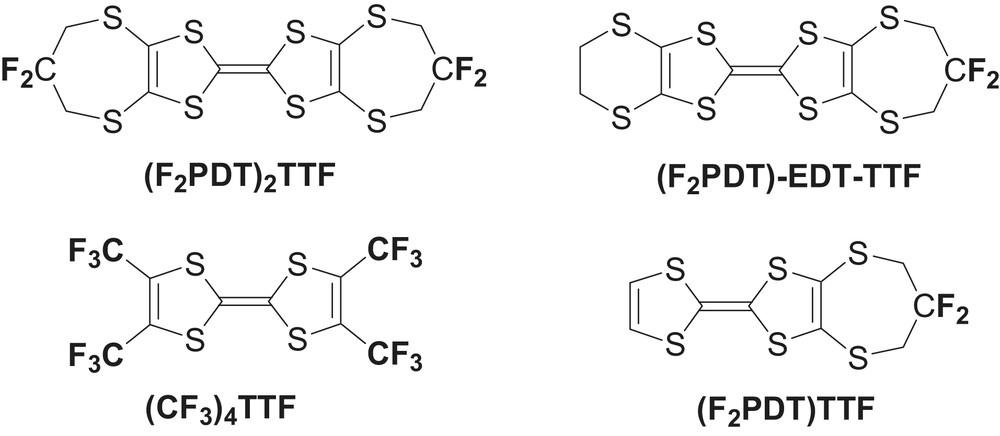

The control of solid state architectures of molecular organic solids through directional, strong intermolecular interactions such as hydrogen [1] or halogen [2] bonds forms the basis of supramolecular solid state chemistry [3], a very successful approach which has allowed a very fine control of supramolecular solid state architectures. On the other hand, in soft matter chemistry, amphiphilic molecules with a strong incompatibility between the different parts give rise to a variety of mesophase morphologies based on the segregation of hydrophilic vs. hydrophobic but also rigid vs. flexible fragments [4]. We wanted to take advantage of segregation effects of fluoroaliphatic groups, well known in soft-matter chemistry, in the realm of crystalline molecular materials as a tool to obtain controlled solid state organizations. For example, semifluorinated tetrathiafulvalenes (TTF) have been prepared for Langmuir–Blodgett films formation [5], while incorporation of highly fluorinated anions such as (CF3)3CF(CH2)2–SO3– in TTF salts also stabilized the formation of layered materials [6,7]. The very strong contrast offered by fluoroaliphatics in polymer science, biochemistry and soft matter chemistry let us infer that a limited number of CF3 or CF2 groups, rather than long CnF2n + 1 perfluoroalkyl chains, adequately positioned on the rigid core, could be sufficient to provide a segregation and formation of layered crystalline structures, also desirable in the structures of the neutral TTF-like donor molecules if one is interested in the design of crystalline thin films for transistor devices [8,9]. In that respect, we already described a series of TTF molecules [10,11] substituted with 2,2′-difluoropropylene-1,3-dithio groups such as (F2PDT)2TTF, (F2PDT)EDT–TTF or (F2PDT)TTF where an effective segregation of the CF2 moieties led to the formation of layered structures with fluorous bilayers. However, the presence of methylenic CH2 groups, activated by the neighboring S and CF2 moieties, did not allow to completely eliminate the possibility that these layers were also stabilized by additional C−H···F hydrogen bonds.

On the other hand, the X-ray crystal structure of tetrakis(trifluoromethyl)TTF, (CF3)4TTF [12], exhibits a one-dimensional pseudo-columnar arrangement with the outer surface of each stack is essentially covered with fluorine atoms. These examples demonstrate that the introduction of CF3 or CF2 moieties on the rigid TTF core can induce a molecular contrast strong enough to force a micro segregation of the fluorinated and aromatic moieties, but does not allow anticipating the formation of either layered of columnar structures.

We therefore decided to prepare the novel fluorinated TTF molecule 1, based on the bis(vinylenedithio)TTF (BVDT-TTF) capped here with two hexafluorotrimethylene −(CF2)3− chains, and lacking any activated hydrogen atoms which could interfere with the fluorine segregation effects in the formation of the supramolecular solid-state organization. We describe here the synthesis of 1 and the analogous, unsymmetrical TTF 2, their electrochemical properties and the X-ray crystal structures of 1 and 2 together with those of intermediate perfluorinated 1,3-dithiole-2-thione and 1,3-dithiole-2-one derivatives.

2 Experimental

2.1 Synthesis

2.1.1 General

Nuclear magnetic resonance spectra were recorded at 500.04 MHz for 1H, 470.28 MHz for 19F and 125.75 MHz for 13C. Mass spectrometry was performed in the MALDI-TOF or high-resolution modes as indicated. 1,2-Dichlorohexafluorocyclopentene was obtained from Aldrich.

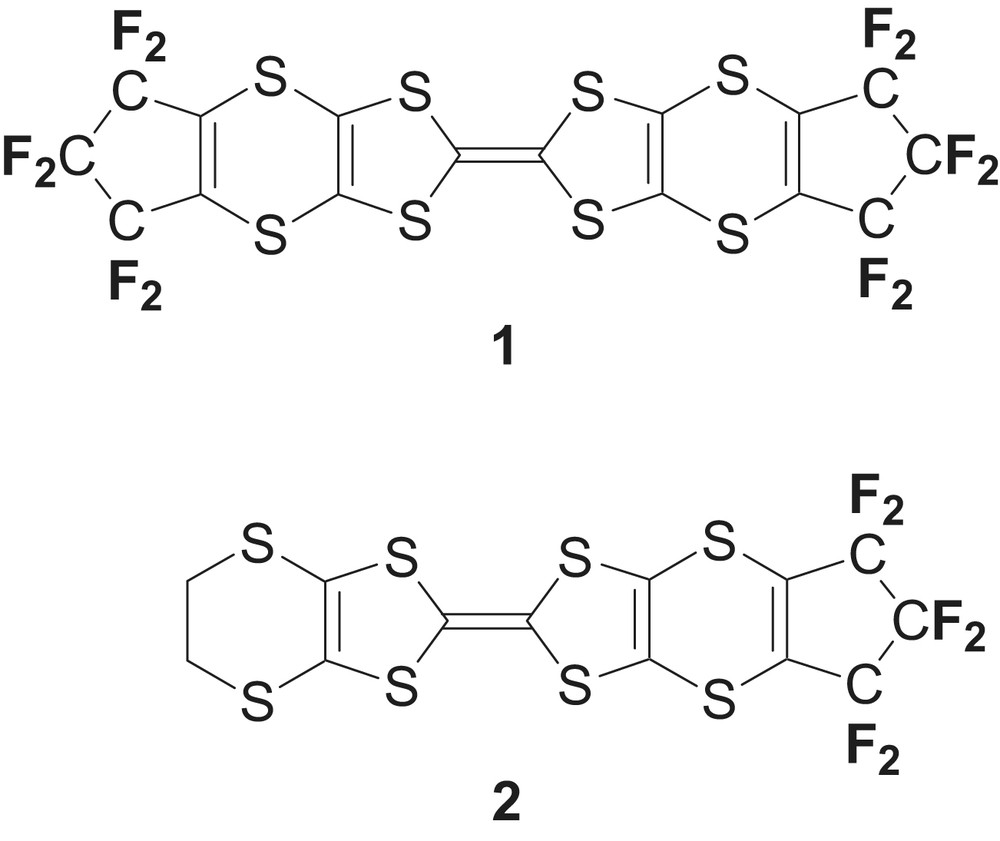

2.1.2 Synthesis of 6,7-dihydro-5H-hexafluorocyclopenta[b]-1,3-dithiolo[4,5-e] [1,4]dithiin-2-thione 3

4,5-Bis(benzoylthio)-2-thioxo-1,3-dithiole (7.4 g, 21.6 mmol) was added to a freshly prepared solution of sodium (1 g, 43.5 mmol) in freshly distilled MeOH (25 ml). After stirring for 20 min, the disodium salt was precipitated by addition of Et2O, filtered and dissolved in freshly distilled CH3CN (100 ml). 1,2-Dichlorohexafluorocyclopentene (3.2 ml, 21.3 mmol) was added to this solution and the reaction stirred overnight. The solvents were evaporated and the solid residue washed with water (2 × 250 ml). The aqueous fraction is extracted with dichloromethane and the combined organic extracts are dried over MgSO4 and evaporated. The residue is chromatographied on silica gel with pentane elution to give 3 as yellow needles (5.04 g, 63%). Suitable crystals for X-ray studies are obtained by recrystallization in pentane. M.p. 100 °C. 19F NMR (CDCl3): –110.97 (t, 4F, 3JFF = 1 Hz); –127.25 (quint., 2F, 3JFF = 1 Hz). 13C NMR (CDCl3): 109.3–115.41 (m, CF2–CF2–CF2); 122.02 (s, S2C=CS2); 138.39 (t of m., CF2SC=CSCF2); 209.94 (s, C=S). EI.HRMS: Calcd: 369.85078; Found: 369.8473. Anal. Calcd. for C8F6S5, C: 25.94; Found, C: 25.48.

2.1.3 Synthesis of 6,7-dihydro-5H-hexafluorocyclopenta[b]-1,3-dithiolo[4,5-e] [1,4]dithiin-2-one 4

Hg(OAc)2 (3.61 g, 11.33 mmol) was added to a solution of 3 (2.1 g, 5.67 mmol) in a 3:1 chloroform/acetic acid mixture (200 ml). After 1-h stirring, the resulting suspension was filtered on celite® and washed with CHCl3 (250 ml). The filtrate was washed with a saturated solution of NaHCO3 (3 × 200 ml), with water (2 × 300 ml) and dried over MgSO4. After evaporation, the crude product is chromatographied on silica gel with pentane/dichloromethane elution (1:1) to give 4 as a pale yellow powder (1.16 g, 58%). Suitable crystals for X-ray studies were obtained by recrystallization from pentane. M.p. 84 °C. 19F NMR (CDCl3): –110.23 (s, 4F), –127.25 (s, 2F). 13C NMR (CDCl3): 109.7–115.19 (m, CF2–CF2–CF2); 113.81 (s, S2C=CS2); 137.97 (t of multiplet, CF2SC=CSCF2); 188.95 (s, C=O). EI.HRMS: Calcd: 353.87362; Found: 353.8764. Anal. Calcd. for C8F6OS4, C: 27.12; Found, C: 26.86.

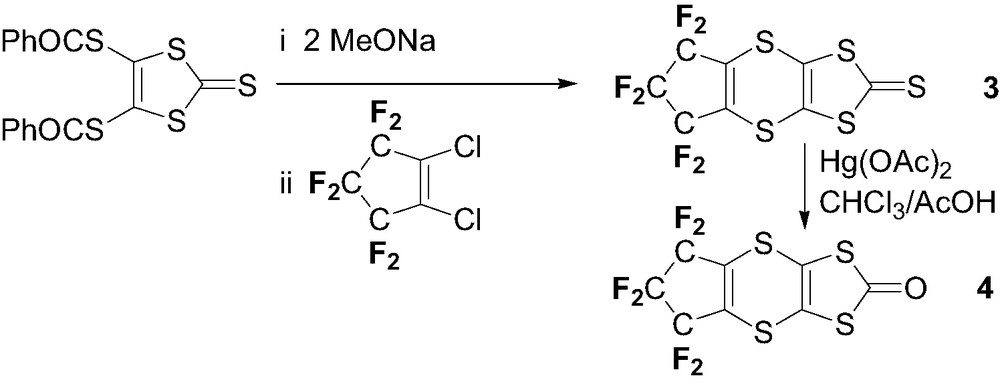

2.1.4 Synthesis of TTF 1

Dithiolone 4 (0.27 g, 0.76 mmol) was heated at 100 °C in (n-BuO)3P (8 ml) for 30 min. After cooling, the orange precipitate was filtered and recrystallized in THF to yield 1 as orange crystals (0.14 g, 54%). Single crystals suitable for X-ray diffraction studies were obtained from a second recrystallization in THF. The very low solubility of the compound did not allow its NMR characterization. M.p. 260 °C. MALDI-TOF MS: Calcd. 675.75, Found: 675.75. Anal. Calc for (C16F12S8): C: 28.40; Found: 27.88.

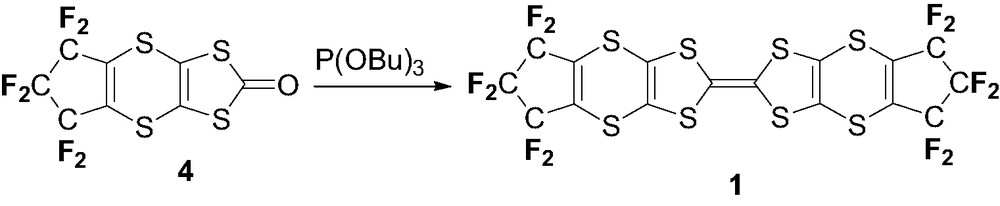

2.1.5 Synthesis of TTF 2

In P(OEt)3: The dithiolone 4 (0.2 g, 0.78 mmol) and 4,5-ethylendithio-2-thioxo-1,3-dithiole 5 (0.17 g, 0.78 mmol) were heated at 110 °C for 1 h in P(OEt)3 (8 ml). TLC (SiO2 3:1 pentane/CH2Cl2) of the reaction mixture shows the presence of at least seven compounds. Chromatography on silicagel (eluent 3:1 pentane/CH2Cl2) afforded the expected dissymmetrical derivative 2 in small quantities (20 mg, 6.7%) together with some symmetrical BEDT–TTF. The product slowly crystallized in the eluent giving only a few orange plates suitable for X-ray diffraction studies. 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 3.31 (s, CH2), 19F NMR (CDCl3) δ −111.21 (s, 4F), −127.37 (s, 2F); MALDI-TOF MS Calcd. 529.80, Found: 529.69.

In P(OMe)3: The dithiolone 4 (0.66 g, 1.86 mmol) and 4,5-ethylendithio-2-thioxo-1,3-dithiole 5 (0.40 g, 1.86 mmol) were heated to reflux in P(OMe)3 (15 ml) for 1.5 h. Precipitation of an orange product occurred after 30 min and then rapidly dissolved giving a dark red solution. The mixture was concentrated and chromatographied on silica gel (eluent: CH2Cl2). The first fraction was essentially a mixture of tetrakis(methylthio)TTF 7 and the unsymmetrical fluorinated TTF 6. A second chromatography on silica gel with pentane elution removed some non-polar impurities while elution with a 1:1 pentane/CH2Cl2 mixture yielded impure tetramethylthio-TTF 7 followed by a small amount of 6, obtained as red plates after solvent removal. Data for 6: M.p. 154 °C. 1H NMR (CDCl3): 2.43 (s, Me). 19F NMR (CDCl3): –111.21 (t, 4F, 3JFF = 4.6 Hz); –127, 33 (quint., 2F, 3JFF = 4.6 Hz). MALDI-TOF MS: Calcd: 531.81; Found: 531.61.

2.2 Electrochemistry

Cyclic voltammetry experiments were performed in CH2Cl2 solutions containing n-Bu4NPF6 0.05 M as electrolyte at a scan rate of 100 mV s−1 with Pt working and counter electrode and Ag+/Ag reference electrode. Ferrocene was used as internal reference.

2.3 X-ray crystallography

Crystals were mounted on top of a thin glass fiber. Data were collected on a Stoe Imaging Plate Diffraction System (IPDS) or a Enraf-Nonius Kappa CCD with graphite monochromated Mo Kα radiation (λ = 0.71073 Å). The crystal data are summarized in Table 1. Structures were solved by direct methods (SHELXS-97) and refined (SHELXL-97) by full-matrix least-squares methods. Absorption corrections were applied for all structures. Hydrogen atoms were introduced at calculated positions (riding model), included in structure factor calculations, and not refined. The cif files have been deposited with the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, 12 Union Road, Cambridge CB2 1EZ, UK (CCDC 293155–293158 for 3, 4, 2 and 1, respectively) and can be obtained by contacting the CCDC (quoting the article details and the corresponding SUP numbers).

Crystallographic data

| Compound | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Formula | C8F6OS4 | C8F6S5 | C13H4F6S8 | C16F12S8 |

| Fw | 354.32 | 370.38 | 530.64 | 676.64 |

| Crystal system | Triclinic | Triclinic | Triclinic | Triclinic |

| Space group | ||||

| a (Å) | 6.9286(13) | 4.8012(3) | 6.7950(7) | 6.9433(7) |

| b (Å) | 8.3690(18) | 16.1384(13) | 9.4646(10) | 11.5381(13) |

| c (Å) | 10.171(2) | 17.280(2) | 15.8552(18) | 27.453(3) |

| α (°) | 91.44(3) | 109.917(8) | 96.055(13) | 93.093(13) |

| β (°) | 97.74(3) | 95.726(7) | 102.053(13) | 90.361(12) |

| γ (°) | 101.79(2) | 91.305(7) | 110.209(12) | 93.860(13) |

| V (Å3) | 571.2(2) | 1250.2(2) | 918.12(17) | 2191.0(4) |

| Z | 2 | 4 | 2 | 4 |

| dcalc (Mg m−3) | 2.060 | 1.968 | 1.919 | 2.052 |

| Diffractometer | Stoe-IPDS | Siemens CCD | Stoe-IPDS | Stoe-IPDS |

| Temperature (K) | 293(2) | 293(2) | 293(2) | 293(2) |

| μ (mm−1) | 0.897 | 0.979 | 1.028 | 0.923 |

| θ-Range (°) | 2.49−26.11 | 2.99−27.50 | 2.34−25.82 | 1.88−25.90 |

| Measured reflections | 5604 | 17 155 | 8953 | 21 422 |

| Independent reflections | 2086 | 5691 | 3289 | 7926 |

| Rint | 0.0572 | 0.1413 | 0.0493 | 0.0395 |

| I > 2σ(I) reflections | 1718 | 2423 | 2261 | 5794 |

| Abs. corr. | Multi-scan | Multi-scan | Multi-scan | Multi-scan |

| Tmax, Tmin | 0.5352, 0.6870 | 0.7243, 1.0554 | 0.7163, 0.8006 | 0.7185, 0.7783 |

| Refined par. | 173 | 343 | 280 | 649 |

| R(F), I > 2σ(I) | 0.0353 | 0.050 | 0.0346 | 0.0402 |

| wR(F2), all | 0.0928 | 0.1059 | 0.0883 | 0.1129 |

| Δρ (e Å−3) | +0.30, −0.29 | +0.33, −0.34 | +0.29, −0.29 | +1.02, −0.45 |

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Syntheses

The preparation of TTFs 1 and 2 is based on cross coupling reactions in phosphite medium of the corresponding perfluorinated dithiolone 4. Reaction of 1,2-dichlorohexafluorocyclopentene with various thiolates (K2S [13], NaSAr) [14] is known to afford the corresponding thioethers in good yields. Accordingly (Scheme 1), we performed the reaction of bis(benzoylthio)-2-thioxo-1,3-dithiole with NaOMe to generate the dmit2– nucleophile which was further reacted with 1,2-dichlorohexafluorocyclopentene in CH3CN to afford 3 in 63% yield. Oxymercuration with Hg(OAc)2 in CHCl3/AcOH afforded the corresponding 1,3-dithiolone 4 in 58% yield.

The corresponding symmetrical perfluorinated TTF 1 was then obtained from 4 by a coupling reaction in tributylphosphite at 100 °C (Scheme 2), as a poorly soluble orange powder. The reaction time should be controlled carefully as the TTF 1, which precipitates after 30 min, rapidly redissolves in P(OBu)3 irreversibly to other products if reaction is not stopped at this stage. This surprising observation has been attributed to a rapid decomposition with elimination of the five-membered perfluorinated ring (see below).

Attempts to prepare the unsymmetrical TTF 2 were performed in triethyl or trimethylphosphite in the presence of 1 eq. of 4,5-ethylendithio-2-thioxo-1,3-dithiole (5) (Scheme 3). A limited amount of 2 was obtained in P(OEt)3, separated from some BEDT–TTF as symmetrical coupling product of 5. On the other hand, reaction performed in P(OMe)3 afforded a complex mixture where, to our surprise, TTFs 6 and 7, bearing −SMe substituents, were isolated in low yields. The presence of 6 and 7 can only be understood from the decomposition of some symmetrical TTF 1 that was formed during the reaction of 4 on itself, followed by alkylation with P(OMe)3. It demonstrates that the hexafluorocyclopentene ring is easily removed from 1 in the conditions of phosphite coupling. This process is most probably at the origin of (i) the rapid decomposition of 1 mentioned above and, (ii) the low yield obtained in the formation of 2.

Nevertheless and despite the low yields obtained from those reactions, TTFs 1 and 2 could be characterized electrochemically and structurally, as described below.

3.2 Electrochemical properties

Cyclic voltammetry experiments were performed in CH2Cl2 to determine the evolution of the redox potentials, particularly by comparison with non-fluorinated analogs such as 8a [15] or 8b [16] (Table 2). Despite the low solubility of the symmetrical derivative 1, a cyclic voltammogram was obtained in CH2Cl2 (Fig. 1), exhibiting a first pseudo-reversible oxidation wave, followed by a second irreversible process.

Cyclic voltammetry data for 1−3 and reference compounds (in V vs. SCE). Values in parenthesis and italics are experimental values determined vs. Fc+/Fc

| Compound | E1ox | E2ox | Solvent | References |

| 1 | 0.85 (0.45) | 1.09 (0.59, irr) | CH2Cl2 | This work |

| 8a | 0.68 | 0.94 | PhCN | [15] |

| 8b | 0.76 | 1.02 | PhCN | [16] |

| 2 | 0.64 (0.24) | 1.08 (0.58) | CH2Cl2 | This work |

| 6 | 0.61 (0.21) | 0.92 (0.52) | CH2Cl2 | This work |

Cyclic voltammogram of 1 (in V vs. Fc+/Fc). Scan limited to the first oxidation wave.

On the other hand, the more soluble unsymmetrical derivatives 2 and 6 exhibit the two prototypical reversible waves of TTF derivatives (Fig. 2). As seen in Table 2, the perfluorination of 8a to 1 induces an anodic shift of the first oxidation potential (Δ = +190 mV), albeit this shift remains limited, when one compares for example the first oxidation potentials of TTF and the perfluorinated (F3C)4TTF [17] which oxidize at 0.33 and 1.05 V (Δ = +720 mV), respectively. This is a likely consequence of the larger distance to the redox core, furthermore through a folded dithiine ring.

Cyclic voltammogram of 2 (in V vs. Fc+/Fc).

3.3 Molecular and solid-state structures

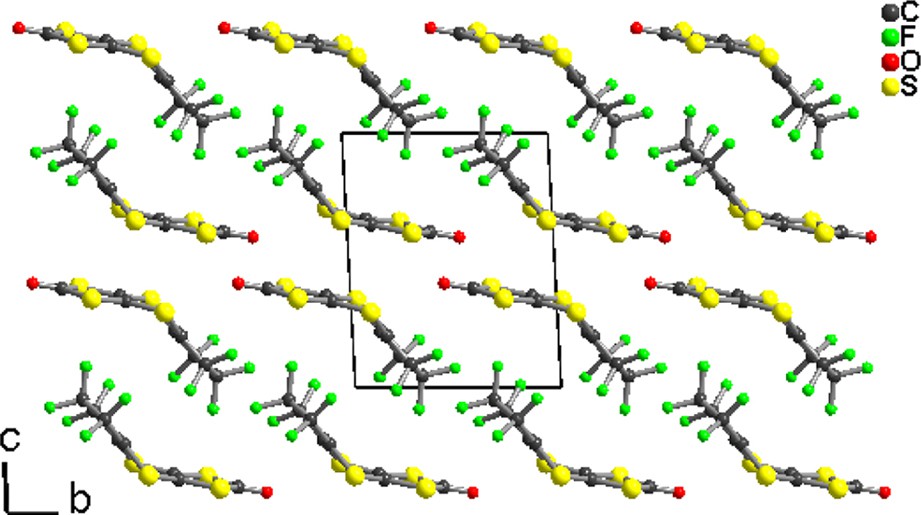

Crystals of the dithiocarbonate 4 have been obtained from pentane. It crystallizes in the triclinic system, space group

Solid-state organization in 4, showing the segregation of the fluorinated moieties.

The corresponding trithiocarbonate 3 also crystallizes in the triclinic system, space group

Unit-cell projection view along a of the trithiocarbonate 3.

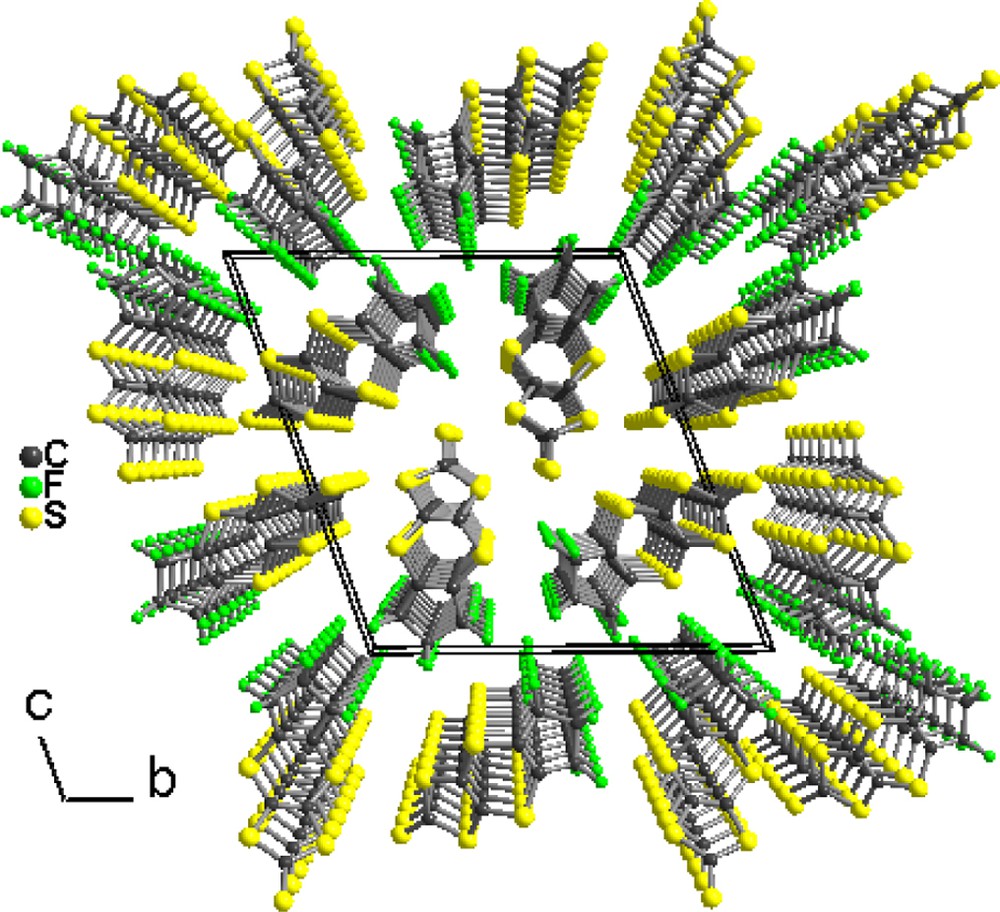

The symmetrical TTF derivative 1 crystallizes in the triclinic system, space group

The two crystallographically independent molecules (A and B) in 1.

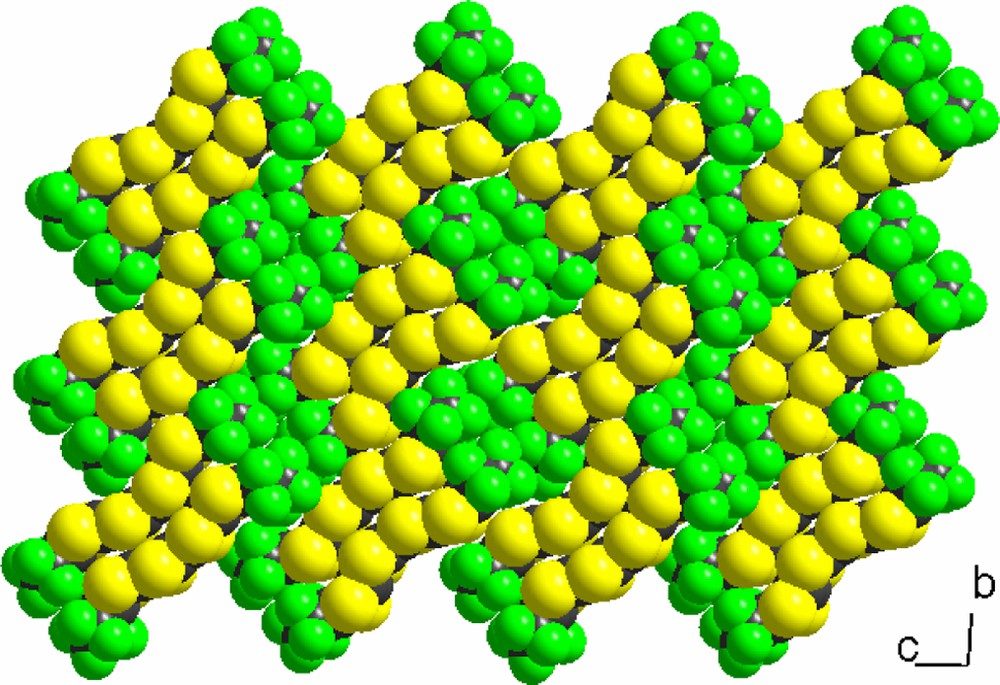

In the solid state, these dyadic moieties with large perfluorinated ends stack side-by-side along a and organize into a chessboard-like pattern in the (bc) plane (Fig. 6), delineating two different kinds of fluorinated zones alternating along the c direction, one of them giving rise to fluorinated bilayers parallel to the (ab) plane, the other limited to columns running along a. This original structural arrangement for neutral TTF derivatives further illustrates the strong tendency of fluorinated aliphatic moieties to segregate in the solid state, without need for long CnF2n + 1 chains, usually used for this purpose [5,18].

Solid-state arrangement in the symmetrical TTF 1.

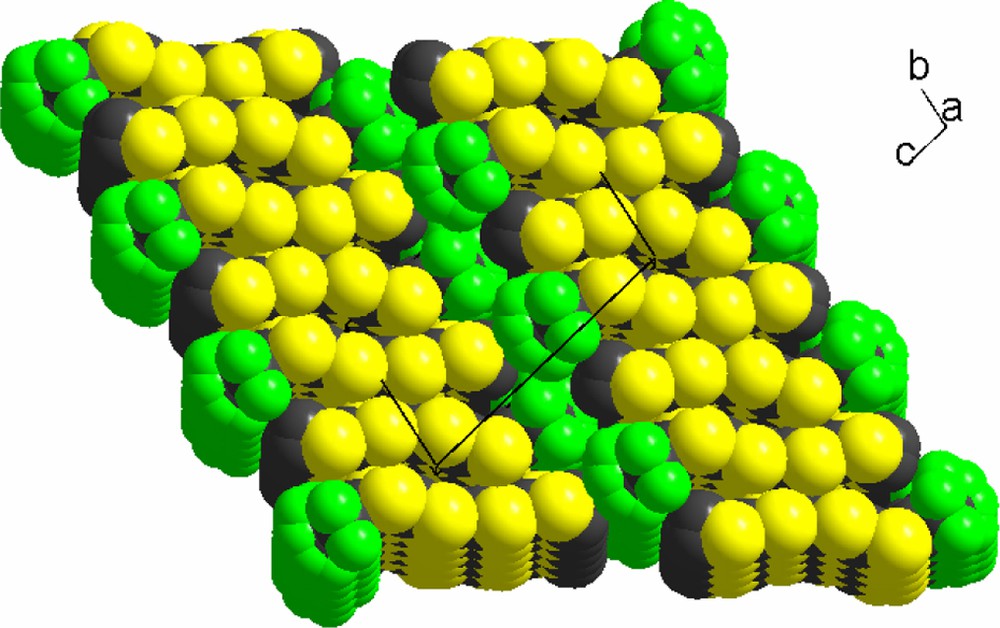

This effect is also observed in the unsymmetrically substituted TTF 2, characterized by two different ends, a −(CF2)3− fluorinated one and a −(CH2)2 hydrogenated one. It crystallizes in the triclinic system, space group

View of 2 with the disordered difluoromethylene (left) and ethylene (right) moieties.

In the solid state, the molecules associate two by two to form slabs parallel to the (ab) plane, with again a strong segregation of the fluorinated moieties, despite the limited number of fluorine atoms when compared with the symmetrical molecule 1. In that respect, the structure of 2 is reminiscent of that described for (F2PDT)2TTF [10], where a similar layered structure was observed, with stacks of TTF moieties most probably stabilized by S···S van der Waals interactions to form slabs, separated from each other by the fluorous bilayer structure. The strong disorder described above, which affects both ends of the molecule, can be interpreted as a lack of structure-directing C−H···F hydrogen bonds, contrariwise to the situation observed in (F2PDT)2TTF [10]. Note that this type of layered structures has proven very desirable for their use in field effect transistor (FET) devices [8,9] and the structure of 2 provides an attractive candidate for this application (Fig. 8).

Solid-state arrangement of 2, showing the efficient fluorine segregation.

4 Concluding remarks

Novel, highly fluorinated TTF derivatives have been prepared by an original method, however limited by the high thermal instability of the hexafluorocyclopentene ring when linked to 1,2-dithiolate moieties. While the low solubility of the symmetrical perfluorinated TTF 1 precluded any possible electrocrystallization experiments [19], the lower oxidation potential and higher solubility of 2 and 6 provides new opportunities for growing single crystals of mixed valence conducting materials. Those experiments are currently in progress, particularly in the presence of organic fluorinated anions [6,7].

5 Supplementary information available

Crystallographic data of 1–4 as cif files. They can also be obtained from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center, 12 Union road, Cambridge CB2 IEZ, UK (fax: +44 1223 33 6033 or e-mail: deposit@ccdc.cam.ac.uk) as supplementary publication on quoting the depository number, No. CCDC 293155–293158 for 3, 4, 2 and 1, respectively.

Acknowledgments

Financial support from the French Ministry of Education and Research (to O.J.) is gratefully acknowledged.

Vous devez vous connecter pour continuer.

S'authentifier