1 Introduction

The proteasome is a multicatalytic protease playing a crucial role in cellular protein turnover in eukaryotic cells. It is involved in the maintenance of the biological homeostasis and degradation of key components of the molecular machinery on which rely important cellular functions such as transcription, cell differentiation, cell-cycle progression, tumor suppression and antigen processing [1]. The regulation of its activity by specific inhibitors makes the proteasome a promising target for cancer treatment as demonstrated by the approval of the peptide boronate bortezomib (or Velcade® or PS-341) by the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of refractory multiple myeloma [2]. Bortezomib and other proteasome inhibitors are currently undergoing clinical trials for various forms of cancer and cardiovascular diseases. Proteasome inhibitors are also potential drugs to be used in a large variety of diseases such as inflammation, muscular dystrophies, tuberculosis, immunological diseases…. As the peptide boronate bortezomib [3], most proteasome inhibitors are short peptides bearing a reactive group which creates a covalent bond with the catalytic Thr1Oγ of the three types of proteasome active sites (for reviews see Ref. [4]). It is the case of peptide aldehydes (MG132, MG262) [5], peptide vinyl sulfones [6], and peptide expoxyketones [7] which are covalently bound to the catalytic sites. The natural β-lactones lactacystin (Streptomyces sp.) [8], salinosporamide (Salinospora tropica) [9] and belactosines A and C (Streptomyces sp. UCK14) [10] are non-peptidic molecules that form covalent acyl ester bonds with Thr1Oγ leading to stable acyl-enzymes [4a]. Bortezomib (injectable preparation) acts quasi-irreversibly with proteasome and important side-effects have been reported [11]. In principle, non-covalent inhibitors should be devoid of the drawbacks associated with the presence of a reactive group as found in covalent inhibitors, i.e., lack of specificity, excessive reactivity, and instability. Nevertheless, non-covalent inhibitors of the proteasome have been investigated less extensively. Ritonavir used in AIDS treatment [12], benzylstatine derivatives [13], lipopeptides [14], the natural tripeptidic TMC-95A [15], and its cyclic [16] and linear [17] analogues have been reported. We used the pseudopeptidic strategy to elaborate new non-covalent inhibitors of 20S proteasome since this was not explored before for proteasome. Pseudopeptides have the advantage of allowing structural modulation of the peptide backbone with possible retention of the side chains required for biological activity. Moreover, the modification of the peptide backbone is expected to enhance resistance to proteolysis in body fluids and cells. This strategy led to several drugs such as antiproteases used in AIDS treatment [18]. We describe here the design, synthesis, and biological characterization of new pseudopeptides interacting with eukaryote 20S proteasome. We have selected in the literature a small portion of protein reported to be preferentially cleaved by proteasome, that of the cytomegalovirus protein pp89. It is cleaved by proteasome between L and G [19]. We synthesized peptides 1–3 of various lengths reproducing the sequence including the cleavage site reported for the whole protein (Fig. 1).

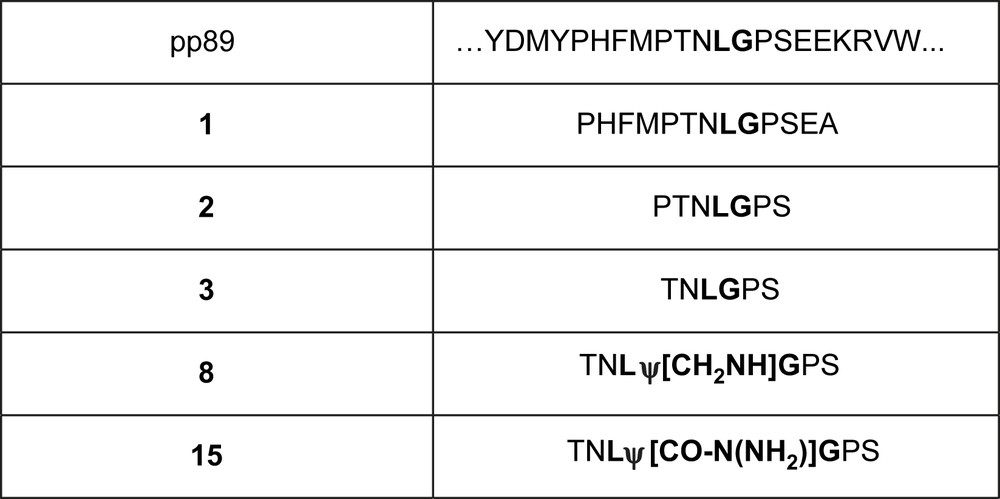

Chosen sequence from cytomegalovirus protein pp89 and some derived peptides and pseudopeptides. The peptidic bond of pp89, peptides 2 and 3 cleaved by proteasome is indicated in bold type.

The most efficiently cleaved peptide was used to produce pseudopeptides 8 and 15. Furthermore, we introduced other structural variations aiming at increasing efficacy and resistance to proteolysis.

2 Results and discussion

2.1 Chemistry

Syntheses of the non-modified peptides 1–3 and 16–23 were carried out using a classical Fmoc/tBu strategy on solid support. Double coupling was performed using a threefold excess of N-Fmoc-amino acid and activation reagents 2-(1H-benzotriazol-1-yl)-1,1,3,3-tetramethyl-uroniumtetrafluoroborate (TBTU), 1-hydroxybenzotria-zole (HOBt), and N,N-diisopropylethylamine (DIEA) (9 equiv) in dimethylformamide (DMF).

Starting from peptide TNLGPS 3 (derived from sequence of protein pp89) acting as a proteasome substrate by cleavage between L and G, the non-cleavable pseudopeptidic links ψ[CH2NH] and ψ[CO-N(NH2)] [20] have been introduced (Fig. 1).

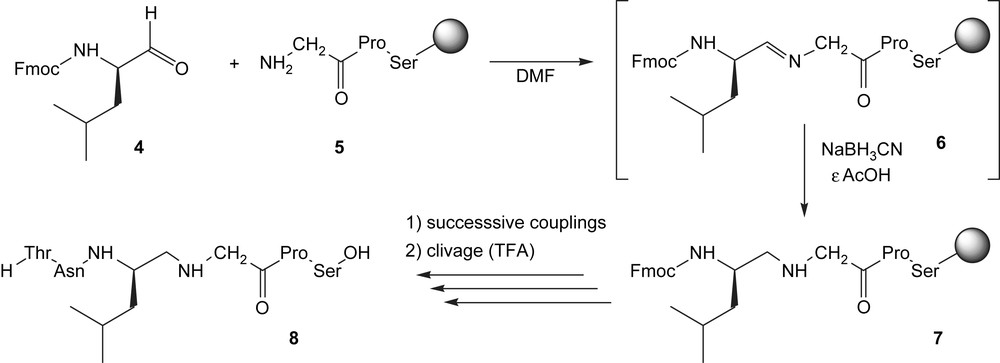

The reduced peptide link ψ[CH2NH] was introduced via a reductive amination. The process lies in the condensation of a protected α-aminoaldehyde (the Fmoc-leucinal) 4 [21] with the N-terminus of the growing peptide 5 to form an imine 6, which is subsequently reduced to amine 7 [22]. Further couplings, deprotections and final cleavage afforded the modified peptide TNLψ[CH2NH]GPS 8 (Scheme 1).

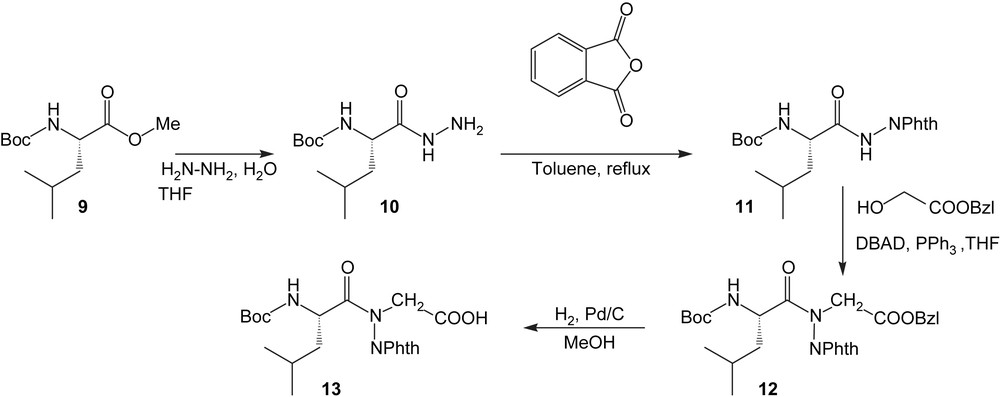

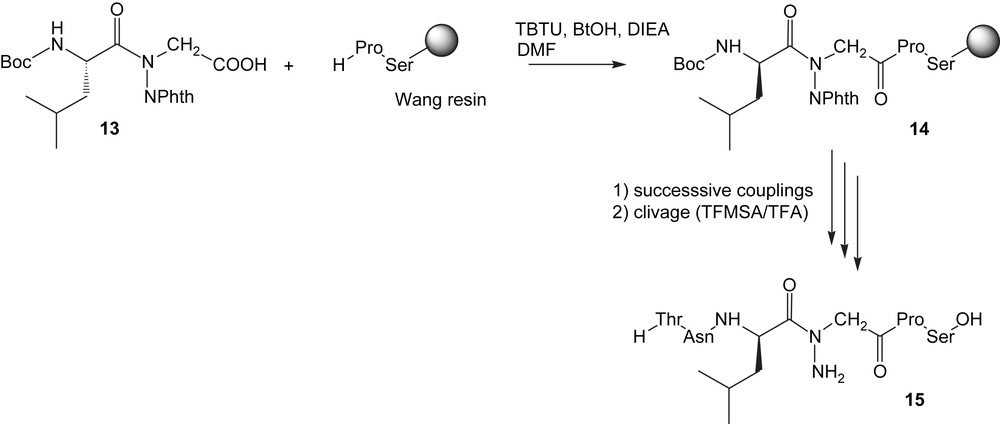

The N-amino link ψ[CO-N(NH2)] has been introduced as a dipeptide building-block, which was previously synthesized in liquid phase (Scheme 2).

The N-aminodipeptide 12 is obtained via the Mitsunobu protocol which involved benzyl glycolate and an N-aminophthalimide derivative 11 as acidic partner [23]. The subsequent catalytic hydrogenation of 12 afforded the building-block 13 which can be introduced in the sequence according to classical Boc/Bzl methodology to give 14, then 15 (Scheme 3).

2.2 Biological results

We studied by HPLC the in vitro cleavage of compounds 1–3 incubated at pH 7.5 and 30 °C for 10 h in the presence of yeast proteasome. In each case, the incubation medium was analyzed by reversed-phase HPLC indicating that all compounds were hydrolyzed but the shortest compound TNLGPS (3) was more efficiently cleaved than compounds 1 and 2 (factors of 4 and 6, respectively). Compound 3 was then selected to produce pseudopeptides by introducing a pseudopeptidic bond ψ instead of the scissile bond L–G: a reduced amide bond for pseudopeptide 8 and N-aminoamide bond for pseudopeptide 15. The inhibitory effects of compounds 3, 8 and 15 were evaluated against the three types of catalytic activities of rabbit protease 20S using the appropriate substrate at pH 7.5 and 37 °C (Fig. 2, Table 1). Whereas compound 3 behaved at the beginning of the enzymatic reaction as an inhibitor towards CT-L and T-L activities, compound 8 inhibited poorly all three activities and compound 15 only CT-L activity. This last molecule was a better inhibitor than the starting compound 3 (factor 2). Several structural variations aiming at improving the efficacy and the metabolic stability of the starting peptide were introduced (Table 1). Replacing polar Asn in 3 by apolar Phe (16) or Leu (17) induced the inhibition of PA activity with loss of inhibition of CT-L. Nevertheless, the inhibitory efficiencies were still poor. Replacing L in 3 by G (17) or I (18) did not increase notably the efficacy against the three types of active sites. The resistance to proteolysis may be greatly improved by introducing d-amino acids since it is known that cellular proteases are unable to cleave peptidic bonds implicating d-amino acids. A d-amino acid was introduced upstream (20, 21, 23) or downstream (22, 23) of the scissile bond. Replacing l-Leu in 3 by d-Leu (21) increased the inhibitory potency against CT-L (factor 10) and favoured PA activity inhibition. This leads to the best inhibitor TN(d)FGPS. Replacement of l-Pro by d-Pro abolished the inhibitory power whereas molecule 23 with d-Leu and d-Pro remained a poor inhibitor of proteasome.

Inhibition of CT-L activity of rabbit 20S proteasome by compound 15 at pH 7.5 and 37 °C (A) and compound 8 (B). The linear variation of V0/Vi with inhibitor concentration is in agreement with competitive inhibition.

Inhibition of CT-L, PA and T-L activities of rabbit 20S proteasome at pH 7.5 and 37 °C.

| Compound | IC50 (μM) | |||

| CT-L activity | PA activity | T-L activity | ||

| 3 | TNLGPS | 803 | nia | 794 |

| 8 | TNLψ[CH2NH]GPS | 636 | 1455 | 1051 |

| 15 | TNLψ[CO-N(NH2)]GPS | 386 | ni | ni |

| 16 | TFLGPS | nd | 221 | 589 |

| 17 | TNGGPS | 23%b | 47%b | 36%b |

| 18 | TNIGPS | 32%b | 30%b | 18%b |

| 19 | TLLGPS | 46%b | 49%b | 51%b |

| 20 | TN(d)FGPS | 882 | 567 | 1217 |

| 21 | TN(d)LGPS | 79 | 86.8 | 501 |

| 22 | TNLG(d)PS | 14%b | ni | 20%b |

| 23 | TN(d)LG(d)PS | 1470 | 1034 | 13%b |

a Non-inhibition.

b % Inhibition at 1 mM.

2.3 Conclusion

The promising preclinical and clinical activity of bortezomib (Velcade®) in malignancies has confirmed the proteasome as an important target in treatment of cancer. Nevertheless, the observed side-effects with the drug demonstrate that there is an urgent need of new drugs, especially of molecules, which do not create a covalent bond with the enzymes' active sites. Pseudopeptides and peptidomimetics meet these criteria. Our preliminary results show that they may constitute a promising strategy for the development of non-covalent inhibitors of proteasome. Their selectivity of action on proteasome and their potential side-effects remain to be characterized. The main fact of this work is that, starting from a substrate of the proteasome, it is possible to obtain inhibitors by introducing a pseudopeptidic modification or d-amino acid(s).

3 Experimental: syntheses and enzymatic studies

3.1 General

3.1.1 Chemistry

Starting materials were purchased from Aldrich, Acros Organics, Merck, Fluka, Senn Chemicals, Novabiochem, etc. and used without any purification. THF was dried and distilled over sodium and benzophenone, methanol over sodium, dichloromethane and acetone over P2O5 or LiAlH4. Reactions were monitored by thin layer chromatography (TLC) using Kieselgel 60 with fluorescent indicator UV254 (purchased from Merck or Macherey-Nagel). Detection was performed by UV or phosphomolybdic acid. Column chromatography was performed using silica gel 60 (70–200 μm). Flash chromatographies were performed on columns of silica gel 60 (40–63 μm). All yields have been calculated from pure isolated products. NMR spectra were recorded on a BRUKER AVANCE spectrometer operating at 300 MHz, in deuterated chloroform (CDCl3) or deuterated dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO-d6). Chemical shifts are given using tetramethylsilane (TMS) as internal standard (δ = 0 ppm for TMS). Infrared spectra were recorded on a BRUKER TENSOR 27 spectrometer. Mass spectra were recorded on a SCIEX API 150EX spectrometer equipped with an ESI source. High-resolution mass spectra were recorded on a ProMALDI/FTMS spectrometer. Abbreviations for NMR: s = singlet; d = doublet; t = triplet; q = quartet; dd = double doublet; m = multiplet; br = broad; mp = melting point; arom = aromatic; Phth = phthalimide; eqiv = equivalent.

3.1.2 Enzyme studies

Rabbit reticulocyte 20S proteasome was obtained from Boston Biochem, Cambridge, USA. Yeast proteasome was obtained using the Sdll 35 strain kindly provided by Dr David Leggett (Harvard Medical Scholl, Boston, USA) and purified [24]. The fluorogenic substrates Suc-LLVY-AMC, Boc-LRR-AMC and Z-LLE-βNA used to measure the proteasome CT-L, T-L and PA activities were purchased from Bachem (France). Fluorescence was measured using a BMG Fluostar microplate reader.

3.2 Synthesis of the building-blocks

3.2.1 Fmoc-Leu-H (4)

Fmoc-leucinal 4 was synthesized according to the procedure described by Douat et al. [21]. The “Weinreb morpholine amide” was prepared, purified (see characterization below) and reduced by LiAlH4 to produce 4, which is used without further purification.

Weinreb amide Fmoc-Leu-N(CH2-CH2)2O: (Rf = 0.40; AcOEt/EP 7/3) 69%.

Formula: C25H30N2O4; molecular weight: 422.5 g/mol; white foam.

1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): 7.76 ppm (2H, d, Ja–b = 7.3 Hz, aroma); 7.60 ppm (2H, m, aromd); 7.40 ppm (2H, dd, Jb–a = Jb–c = 7.3 Hz, aromb); 7.31 ppm (2H, m, aromc); 5.57 ppm (1H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, NH); 4.70 ppm (1H, m, CHCH2CH(CH3)2); 4.37 ppm (2H, m, FmocCHCH2); 4.22 ppm (1H, t, J = 6.7 Hz, FmocCH); 3.66 ppm (4H, m, NCH2CH2); 3.47 ppm (4H, m, NCH2); 1.69 ppm (1H, m, CHCH2CH(CH3)2); 1.54 ppm (2H, m, CHCH2CH(CH3)2); 0.99 ppm (3H, d, J = 6.5 Hz, CH3); 0.94 ppm (3H, d, J = 6.5 Hz, CH3).

3.2.2 Boc-Leu-NHNH2 10

Boc-Leu-OMe 9 (50 mmol) was dissolved in methanol (50 ml). Hydrazine monohydrate (2 equiv) was added to the resulting solution at 0–5 °C and stirred vigorously until a precipitate appeared. The white solid was filtered, washed with the minimum volume of anhydrous diethylether and dried in a vacuum desiccator. The crude product was recrystallized from Et2O/EtOH to give 10 (85%).

Formula: C11H23N3O3; molecular weight: 245 g/mol; white solid.

1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz): δ (ppm) 8.50 (s, 1H, NH-NH2); 7.73 (d, 1H, J = 8.4 Hz, Boc-NH); 4.23–4.21 (m, 1H, CHCH2CH(CH3)2); 1.69–1.36 (m, 12H, NHCOOC(CH3)3, CHCH2CH(CH3)2, CHCH2CH(CH3)2); 0.95–0.92 (m, 6H, CHCH2CH(CH3)2).

3.2.3 Boc-Leu-NHNPhth 11

In a one necked round bottom flask equipped with a Dean–Stark apparatus, hydrazide 10 (50 mmol) and phthalic anhydride (50 mmol) were dissolved in toluene (500 ml) under stirring and the resulting solution was heated to reflux for 6 h. A white solid was obtained by cooling the solution with an ice-water bath. After filtration, the crude product was purified by recrystallization from petroleum ether/EtOAc.

Formula: C19H25N3O5; molecular weight: 375 g/mol; white solid; 90%; mp = 107 °C.

IR: νmax (cm−1) 3331; 3253 (NH); 1798; 1741; 1686 (CO).

1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz): δ (ppm) 9.45 (s, 1H, NHNPhth); 7.85–7.73 (m, 4H, H arom Phth); 5.21–5.19 (m, 1H, NH); 4.74–4.65 (m, 1H, CHCH2CH(CH3)2); 1.79–1.38 (m, 12H, NHCOOC(CH3)3, CHCH2CH(CH3)2 and CHCH2CH(CH3)2); 0.99; 0.96 (2d, 6H, J = 6 Hz, Hf).

13C NMR (CDCl3): δ (ppm) 172.7 (CON(NPhth)); 165.5 (CO Phth); 156.9 (NHCOOtBu); 135.1 (CH arom Phth); 130.8 (C arom); 124.4 (CH arom Phth); 81.3 (OC(CH3)3); 51.7 (Cc); 40.9 (Cd); 28.9 (Ca); 25.2 (Ce); 23.5; 22.6 (Cf).

3.2.4 Boc-Leuψ[CON(NPhth)]Gly-OBn 12

To a stirred solution of Boc-Leu-NHNPhth 11 (3 mmol), PPh3 (4.5 mmol) and methyl glycolate (4.5 mmol) in anhydrous THF (50 mL) under nitrogen atmosphere, di-tert-butylazodicarboxylate (4.5 mmol) was added portionwise with stirring at 0–5 °C. The resulting solution was stirred at room temperature until completion (monitored by TLC) and concentrated in vacuum. The residue was purified by column chromatography using a mixture EtOAc/petroleum ether (30/70) as eluent.

Formula: C28H33N3O7; molecular weight: 523 g/mol; oil; 92%.

IR νmax (cm−1) 3370 (NH); 1798; 1741; 1618 (CO).

1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz): δ (ppm) 7.92–7.77 (m, 4H, H arom Phth); 7.37–7.27 (m, 5H, H arom); 5.13 (s, 2H, COOCH2Ph); 4.94 (d, 1H, J = 9.8 Hz, NH); 4.74 (d, 1H, J = 17 Hz, CH2COOBn); 4.44–4.32 (m, 1H, CHCH2CH(CH3)2); 4.24 (d, 1H, J = 17 Hz, CH2COOBn); 1.61–1.52 (m, 2H, CHCH2CH(CH3)2); 1.44–1.31 (m, 10H, NHCOOC(CH3)3 and CHCH2CH(CH3)2); 0.85 (d, 3H, J = 5.8 Hz, CHCH2CH(CH3)2); 0.73 (d, 3H, J = 5.8 Hz, CHCH2CH(CH3)2).

13C NMR (CDCl3): δ (ppm) 174.5 (CON(NPhth)); 167.5 (COOBn); 164.8; 164.5 (CO Phth); 155.4 (NHCOOtBu); 135.6 (ArC); 135.4; 135.3 (PhthCH); 130.3 (ArC); 129.3; 129.2; 129.1; 129.0; 128.9 (ArCH); 124.7; 124.6; 124.5 (PhthCH); 80.2 (NHCOOC(CH3)3); 67.8 (COOCH2Ph); 49.9 (CH2COOBn); 48.6 (CHCH2CH(CH3)2); 42.5 (CHCH2CH(CH3)2); 28.7 (NHCOOC(CH3)3); 24.9 (CHCH2CH(CH3)2); 23.6; 22.4 (CHCH2CH(CH3)2).

HRMS: Calculated for C28H33N3NaO7 [M + Na+] m/z 546.2367, found 546.2345.

3.2.5 Boc-Leuψ[CON(NPhth)]Gly-OH 13

Formula: C21H27N3O7; molecular weight: 433 g/mol; white solid; 87%.

1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz): δ (ppm) 9.87 (s, 1H, COOH); 7.98–7.85 (m, 4H, H arom Phth); 5.08 (d, 0.25H, J = 9.9 Hz, NHCOOC(CH3)3); 4.92 (d, 0.75H, J = 9.9 Hz, NHCOOC(CH3)3); 4.73 (d, 1H, J = 17 Hz, CH2COOH); 4.60–4.47 (m, 1H, CHCH2CH(CH3)2); 4.40 (d, 1H, J = 17 Hz, CH2COOH); 1.64–1.23 (m, 12H, NHCOOC(CH3)3 and CHCH2CH(CH3)2); 1.02–0.95 (m, 6H, CHCH2CH(CH3)2).

13C NMR (CDCl3): δ (ppm) 174.6 (COOH); 168.2 (CON(NPhth)); 164.9; 164.5 (CO Phth); 155.4 (NHCOOtBu); 135.5; 135.3 (PhthCH); 130.4 (ArC); 124.8; 124.6 (PhthCH); 80.3 (NHCOOC(CH3)3); 49.6 (CH2COOH); 48.7 (CHCH2CH(CH3)2); 42.6 (CHCH2CH(CH3)2); 28.9; 28.8 (NHCOOC(CH3)3); 25.2; 25.0 (CHCH2CH(CH3)2); 23.8; 23.6; 22.7; 22.4 (CHCH2CH(CH3)2).

HRMS calculated for C22H33N3NaO7 [M + Na]+ m/z 456.1741, found 456.1723.

3.3 Assembly of the peptides and pseudopeptides

3.3.1 Peptides 1–3 and 16–23

Non-modified peptides 1–3 and 16–23 were obtained by solid-phase synthesis using classical Fmoc/tBu methodology on a multichannel peptide synthesizer [25]. The side chains of threonine, serine, and glutamic acid were protected by tBu (tert-butyl) or Boc groups (Boc, tert-butoxycarbonyl) as appropriate. Asparagine and histidine were protected by a trityl group. Each coupling step employed 3 equiv of Fmoc-aminoacid in the presence of 3 equiv of HOBt and TBTU, and 9 equiv of DIEA in DMF, at room temperature. Coupling was usually complete within 1 h, as determined by the 2,4,6-trinitrobenzenesulfonic acid (TNBSA) test. The Fmoc group was deprotected with 25% (v/v) piperidine in DMF. The peptides were cleaved from the resin, and the side chains deprotected, by treating with a mixture of 0.75 g crystalline phenol, 0.25 mL 1,2-ethanedithiol, 0.5 mL thioanisole, 0.5 mL deionized H2O, and 10 mL trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) for 1.5 h. Crude peptides, which were generally >85% pure as assessed by analytical reverse-phase HPLC were purified by preparative RP-HPLC, giving final purities >97%. 1H NMR spectra for peptides were fully consistent with the assigned structures.

H-PHFMPTNLGPSEA-OH 1

| NH | α | β | γ | δ | ɛ | Others | |

| Pro | 4.2 | 2.21; 1.99 | 1.85; 1.78 | 3.21 | |||

| His | 8.79 | 4.67 | 2.98 | 2H = 7.43; 4H = 6.99 | |||

| Phe | 8.21 | 4.53 | 3.00; 2.81 | arom = 7.18; 7.25; 7.31 | |||

| Met | 8.54 | 4.67 | 2.09; 1.81 | 2.49 | 1.94 | ||

| Pro | 4.53 | 2.2–1.75 | 1.86; 1.78 | 3.48 | |||

| Thr | 7.93 | 4.23 | 4.00 | 1.07 | |||

| Asn | 8.23 | 4.55 | 2.98; 2.81 | 2.2–1.75 | 3.64; 3.47 | NH2 = 7.41; 6.99 | |

| Leu | 7.94 | 4.32 | 1.68 | 1.47 | 0.86; 0.81 | ||

| Gly | 8.37 | 4.35; 3.59 | |||||

| Pro | 4.53 | 2.2–1.75 | 2.2–1.75 | 3.64; 3.47 | |||

| Ser | 8.01 | 4.57 | 3.78 | ||||

| Glu | 7.78 | 4.3 | 1.78 | 2.26 | |||

| Ala | 8.23 | 4.17 | 1.26 |

MS calculated for C62H92N16O19S [M + H]+ m/z 1397.64, found 1397.30.

H-PTNLGPS-OH 2

| NH | α | β | γ | δ | Others | |

| Pro | 4.55 | 2.22–1.73 | 1.87; 1.79 | 3.51 | ||

| Thr | 8.11 | 3.84 | 3.63 | 1.13 | ||

| Asn | 7.22 | 4.55 | 2.64; 2.48 | NH2 = 7.56; 7.08 | ||

| Leu | 8.10 | 4.42 | 1.68 | 1.63 | 0.83 | |

| Gly | 8.15 | 4.22; 3.99 | ||||

| Pro | 4.52 | 2.30; 2.12 | 1.90; 1.80 | 3.52 | ||

| Ser | 8.23 | 4.25 | 3.75; 3.66 |

MS calculated for C29H48N8O11 [M + H]+ m/z 685.34, found 685.22.

H-TNLGPS-OH 3

| NH | α | β | γ | δ | Others | |

| Thr | 8.09 | 3.80 | 3.60 | 1.10 | ||

| Asn | 7.20 | 4.53 | 2.62; 2.45 | NH2 = 7.53; 7.01 | ||

| Leu | 8.07 | 4.34 | 1.64 | 1.63 | 0.82 | |

| Gly | 8.13 | 4.22; 3.96 | ||||

| Pro | 4.51 | 2.28; 2.10 | 1.88; 1.80 | 3.50 | ||

| Ser | 8.21 | 4.21 | 3.72; 3.61 |

MS calculated for C24H41N7O10 [M + H]+ m/z 588.29, found 588.46.

H-TFLGPS-OH 16

| NH | α | β | γ | δ | Others | |

| Thr | 8.09 | 3.91 | 3.65 | 1.19 | ||

| Phe | 8.78 | 4.63 | 2.63; 2.52 | |||

| Leu | 8.36 | 4.38 | 1.62 | 1.49 | 0.87 | |

| Gly | 7.82 | 3.91; 3.47 | ||||

| Pro | 4.52 | 2.22; 2.05 | 2.03; 1.85 | 3.48 | ||

| Ser | 8.31 | 4.31 | 3.78; 3.69 |

MS calculated for C24H41N7O10 [M + H]+ m/z 621.32, found 621.18.

H-TNGGPS-OH 17

| NH | α | β | γ | δ | Others | |

| Thr | 8.05 | 3.88 | 3.59 | 1.10 | ||

| Asn | 8.72 | 4.60 | 2.60; 2.49 | NH2 = 7.42; 6.96 | ||

| Gly | 8.14 | 3.78; 3.69 | 1.90 | |||

| Gly | 7.92 | 3.99; 3.48 | ||||

| Pro | 4.64 | 2.22; 2.00 | 2.03; 1.80 | 3.50 | ||

| Ser | 8.31 | 4.21 | 3.72; 3.67 |

MS calculated for C24H41N7O10 [M + H]+ m/z 532.23, found 531.98.

H-TNIGPS-OH 18

| NH | α | β | γ | δ | Others | |

| Thr | 8.09 | 3.81 | 3.58 | 1.16 | ||

| Asn | 8.69 | 4.69 | 2.58; 2.42 | NH2 = 7.38; 6.90 | ||

| Ile | 7.90 | 4.20 | 1.75 | 1.53 | 0.72 | γCH3 0.99 |

| Gly | 8.05 | 4.19; 3.62 | ||||

| Pro | 4.50 | 2.22; 1.99 | 1.83; 1.76 | 3.46 | ||

| Ser | 8.39 | 4.29 | 3.72; 3.65 |

MS calculated for C24H41N7O10 [M + H]+ m/z 588.29, found 588.14.

H-TLLGPS-OH 19

| NH | α | β | γ | δ | Others | |

| Thr | 8.07 | 3.78 | 3.59 | 1.13 | ||

| Leu | 8.19 | 4.33 | 1.61 | 1.45 | 0.82 | |

| Leu | 8.53 | 4.41 | 1.67 | 1.48 | 0.91 | |

| Gly | 7.92 | 3.91; 3.50 | ||||

| Pro | 4.53 | 2.22; 1.92 | 1.87; 1.75 | 3.44 | ||

| Ser | 8.30 | 4.31 | 3.72; 3.61 |

MS calculated for C24H41N7O10 [M + H]+ m/z 587.33, found 587.42.

H-TN(d)FGPS-OH 20

| NH | α | β | γ | δ | Others | |

| Thr | 3.82 | 3.55 | 1.13 | |||

| Asn | 8.56 | 4.58 | 2.22; 2.15 | NH2 = 7.29; 6.91 | ||

| Phe | 8.09 | 4.89 | 3.05; 2.67 | |||

| Gly | 8.18 | 4.03; 3.81 | ||||

| Pro | 4.55 | 2.22; 2.05 | 1.88; 1.81 | 3.48 | ||

| Ser | 8.31 | 4.27 | 3.72; 3.60 |

MS calculated for C24H41N7O10 [M + H]+ m/z 622.28, found 622.34.

3.3.2 Reduced peptide TNLψ[CH2NH]GPS 8

Peptide 8 was synthesized according to an Fmoc/tBu protocol with the same side-chain protections as above. The amino acids were added sequentially until the site of the reduced amide bond was reached. At that point, the N-terminal Fmoc group was cleaved with piperidine and a solution of the Fmoc-amino aldehyde (3 equiv) in 1% HOAc/DMF (5 mL) was introduced into the reaction vessel. Sodium cyanoborohydride (3 equiv) was then added portionwise over a 1 h period. The mixture was allowed to stand overnight under stirring. The synthesis of the peptide was then completed using classical Fmoc/tBu strategy.

| NH | α | β | γ | δ | Others | |

| Thr | 8.1 | 3.79 | 3.58 | 1.11 | ||

| Asn | 7.2 | 4.53 | 2.62; 2.45 | NH2 = 7.53; 7.01 | ||

| rLeu | 8.07 | 4.21 | 1.41; 1.22 | 1.61 | 0.84 | Red CH2 = 3.01; 2.89 |

| Gly | 8.11 | 4.30; 3.95 | ||||

| Pro | 4.51 | 2.27; 2.08 | 1.88; 1.79 | 3.43 | ||

| Ser | 8.21 | 4.21 | 3.72; 3.61 |

MS calculated for C24H43N7O9 [M + H]+ m/z 574.31, found 574.41.

3.3.3 N-Aminopeptide TNLψ[CO-N(NH2)]GPS 15

Peptide 15 was obtained by solid-phase synthesis using classical Boc/Bzl methodology using the in situ neutralization protocol [25]. The side chains of threonine and serine were protected by a Bzl group. Asparagine was protected by a xanthyl group. The building-block Boc-Leuψ[CON(NPhth)]Gly-OH 13 was introduced as a natural amino acid using a twofold excess.

| NH | α | β | γ | δ | Others | |

| Thr | 8.11 | 3.88 | 3.52 | 1.11 | ||

| Asn | 8.67 | 4.68 | 2.60; 2.41 | NH2 = 7.35; 6.91 | ||

| Leu | 7.85 | 5.02 | 1.43 | 1.62 | 0.71 | N-NH2 = 4.35 |

| Gly | 8.13 | 4.80; 3.99 | ||||

| Pro | 4.51 | 2.22; 2.03 | 1.88–1.79 | 3.48 | ||

| Ser | 8.43 | 4.28 | 3.72 |

MS calculated for C24H44N8O9 [M + H]+ m/z 589.32, found 589.16.

3.4 Enzyme and inhibition assays

Enzyme activities were determined by monitoring the hydrolysis of the appropriate fluorogenic substrate (λexc = 360, λem = 465 nm for AMC substrates, and λexc = 340, λem = 405 nm for the βNA substrate) for 1 h at 37 °C, in the presence of untreated (control), or proteasome that had been incubated with 1–1000 μmol/L of test compounds ([E] = 0.2 μg/mL; [Suc-LLVY-AMC]0 = 50 μmol/L; [Boc-LRR-AMC]0 = [Z-LLE-βNA]0 = 100 μmol/L). Substrates and compounds were previously dissolved in DMSO, with the final solvent concentration kept constant 3% (v/v). The buffers were (pH 7.5): 20 mmol/L Tris, 1 mmol/L DTT, 10% glycerol, 0.02% (w/v) SDS (CT-L and PA activities) and 20 mmol/L Tris, 1 mmol/L DTT, 10% glycerol for T-L activity. Initial rates determined in control experiments (V0) were considered to be 100% of the peptidase activity; initial rates (Vi) below 100% were considered to be inhibitions. The IC50 values (inhibitor concentration giving 50% inhibition) were obtained by plotting the percent inhibition against inhibitor concentration and fitting the experimental data to equation: % inhibition = 100[I]0/(IC50 + [I]0) or, in few cases (compound 15 for CT-L activity), to equation: where nH is the Hill number.

3.5 HPLC experiments

Peptides (1 mmol/L) were incubated in the presence of yeast proteasome (2 μg/mL) in 20 mmol Tris (pH 7.5), 1 mmol/L DTT, 1 mmol/L MgCl2, 1 mmol/L ATP, 10% glycerol, 0.02% SDS for 10 h. The mixture was filtered on Centricon 30 filtration units (4500 g, 45 min, 4 °C), and loaded onto a Lichrosorb C18 reverse-phase column (Interchim) equilibrated in buffer A (TFA 0.1% in water). Peptides were eluted using a linear gradient from 100% to 40% of buffer A versus buffer B (TFA 0.07% in acetonitrile). The elution profiles and pick areas obtained for the peptides incubated without the enzyme were compared to those obtained for the peptides incubated in the presence of enzyme.