1 Introduction

The importance of vicinal amino alcohols as compounds possessing pharmaceutical and biological properties is well recognized. Indeed, the 1,2-aminoalcohol's function is present in the widely consumed drug propanolol, a β-blocking agent and in the structure of serine protease inhibitors [1–3]. Optically active 1,2-aminoalcohols have an interesting role in asymmetric synthesis and are useful as chiral ligands for catalysts or as chiral auxiliaries [4–5]. Numerous synthetic methods exist for the preparation of these compounds [6–8]. Racemic epoxides, which are easily available, can be readily transformed by reactions with various nucleophiles into 1,2-substituted derivatives and especially into 1,2-amino alcohol [9]. In an ongoing project in our laboratory; we were interested in the synthesis of 1,2-aminoalcohols derivatives from reaction of (S)-α-methyl-benzyl-amine with racemic styrene oxide in presence of different solvents (Scheme 1). This enantioselective ring opening of epoxides by amines is more attractive. The main objective of this work was to report a short and practical sequence to obtain two regioisomers after an attack of the (S)-α- methyl-benzyl- amine on the (R,S)-styrene oxide. In this article we will describe their synthesis and their characterizations.

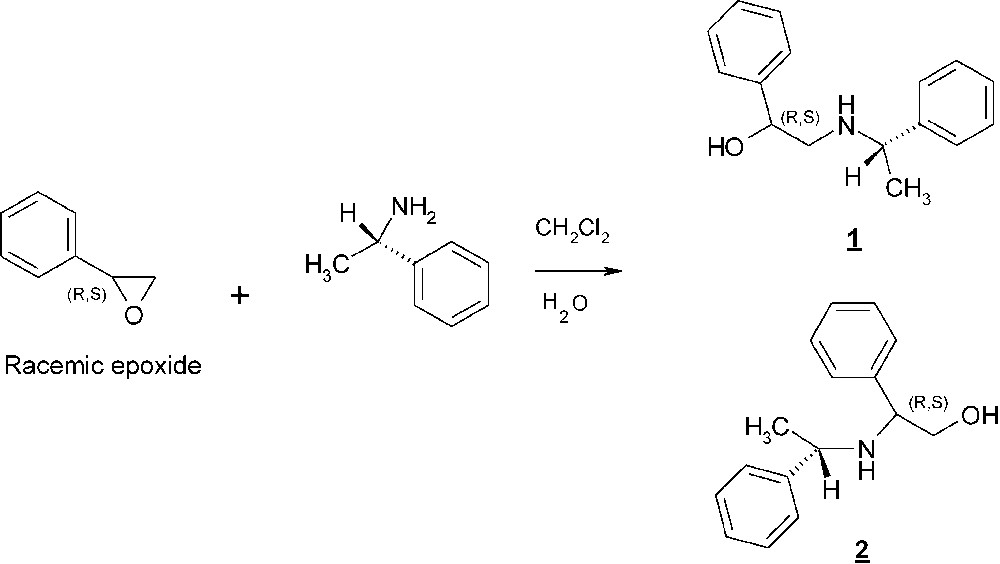

Reaction of ring opening of racemic styrene oxide by (S)-methyl-benzylamine in aqueous medium.

2 Results and discussion

2.1 In aqueous medium

Most of the 1,2-aminoalcohols often have been derived from natural compounds such as amino acids [10–11]. Their structural motifs have proven a high efficiency in other asymmetric transformation. The method we used for the synthesis of 1,2-Amino alcohols, involved the opening of the racemic styrene oxide by the (S)-benzyl-methyl-amine in water .We obtained two regioisomers (Scheme 1).

The infrared spectra show the presence of an absorption band around 3250–3500 cm−1, which corresponds to the hydroxyl and amine groups.

The analysis of 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra revealed the following characteristics.

In the proton NMR, the distinction of 1,2-amino alcohols 1/2 is observed easily by considering the proton chemical shift of H carried by the tertiary carbon C1. This proton is less shielded in the ethanolamine-1 (around 4.70 ppm) than in the ethanolamine-2 (around 4.10 ppm) due to the proximity of oxygen (Table 1). For the same reasons, in regioisomers 1, the methylene protons (-CH2-) are significantly more shielded.

1H NMR chemical shifts of methylene and methine of amino alcohols.

| Compound | Group | Chemical shift (ppm) | Signal |

| Amino alcohol 1 | CH2NH | 2.60–2.80 | M |

| CH-OH | 4.70 | Dd | |

| Amino alcohols 2 | CH2OH | 3.55 | M |

| CH-NH | 4.10 | M |

The identification of regioisomers 1 and 2 is even easier by 13C NMR. Indeed, the tertiary carbon C1 is influenced either a nitrogen or an oxygen and appears to 72 ppm and 66 ppm for ethanol amines 1 and 2, respectively (Table 2).

13 C NMR spectra of amino alcohols.

| Compound | Group | Chemical shift (ppm) | Signal |

| Amino alcohol 1 | CH2-CH–OH | 72.0 | D |

| CH2–NH - | 54.8 | T | |

| Amino alcohols 2 | CH2–OH | 54.7 | T |

| CH2-CH–NH- | 66.0 | D |

According to the 1H NMR spectrum of substituted amino alcohol 1 whose data are given in Table 1 the multiplet (it should be in the form of a doublet of doublets at higher resolution) of the methylene radical CH2-NH appears at 2.75 ppm. On the other hand, the 1H NMR spectrum of the isomer 2 shows that the methylene radical CH2-OH appears at 3.55 ppm. This is probably due to the difference in electronegativity of heteroatoms (N and O) situated at the immediate vicinity. For similar reasons, the methine proton of the CH-OH of amino alcohol 1and the methine proton of CH-NH the isomer 2, appear at 4.70 ppm and at 4.10 ppm, respectively.

The identification of regioisomers 1 and 2 is even easier by 13C NMR. Indeed, the secondary carbon atoms are influenced by the presence of nitrogen and oxygen vicinal atoms. Their chemical shifts are presented in Table 2.

2.2 In acid medium

The ONAKA's method [12] was applied using silica in the reaction medium. It was found that not only the percentage of regioisomer 2 had increased but this isomer became majority comparatively to the aqueous medium seen previously.

The opening of the racemic epoxide in the presence of silica, which is considered as a slight acid had yielded majority the regioisomer 2. Thus Lewis acids that are acids relatively more strong should be interesting. Indeed, under these last conditions a total absence of the regioisomer 1 was noted. The experimental results are listed in Table 3.

Effects of different catalysts on the reaction yields.

| Catalyst | Solvent | 1 (%) | 2 (%) | Global yield (%) |

| SiO2 | CH2Cl2 | 19 | 81 | 60 |

| AlCl3 | CH2Cl2 | 0 | 100 | 73 |

| ZnCl2 | CH2Cl2 | 0 | 100 | 90 |

It is known that silica is sometimes used as Lewis acid in the reactions of heterogeneous catalysis [13–14]. Indeed, the silicon atoms have a vacant 3d orbital willing to form a dative bond with the oxygen atoms of carbonyl groups. Thus, the lone pair of oxygen of the oxide could interact with a vacant 3d orbital of an atom of silicon from the surface of silica gel. The breaking of bond O-C2 of the intermediate oxonium resulted after departure of the silica at the corresponding ylide of oxamethine. The attack of the amine on the aliphatic carbocation leads to the aminoalcohol 2 only. The mechanism is the same if one uses a Lewis acid instead of silica (Scheme 2). The aminoalcohol 2 derives from the nucleophilic attack of amine on carbon C2 most hindered.

The mechanism for obtaining regioisomer 2 alone during the use of a Lewis acid.

3 Conclusion

The action of a primary chiral and aliphatic amine always leads majority to the opening of the styrene oxide on the less hindered side with obtaining almost quantitative ethanolamine 1. The use of silica, in the reaction medium, permits it to form mostly the other diastereoisomer (compound 2). The reaction became regiospecific (obtaining a single regioisomer 2) when a Lewis acid is used in place of silica. The yield of the reaction for obtaining the aminoalcohol 2 was evolved from a minority in an aqueous medium to a majority state in the presence of silica and to 100% in the case of Lewis acid (AlCl3 and ZnCl2).

4 Experimental

4.1 General methods

Melting points were measured on a Kofler apparatus. Infrared spectra were recorded on a Shimadzu FTIR 8400 S instrument; the NMR spectra were measured on a Bruker AC 200 instrument in CDCl3 as solvent. Chemical shifts are in ppm from TMS as internal standard and coupling constants are in hertz. Merck silica gel 60H was used to prepare short-column chromatography.

4.2 Procedures for the preparation of 1,2-aminoalcohol

4.2.1 In aqueous middle

A mixture of 9.26 ml (72 mmol) of the (S)-methyl-benzyl-amine (dissolved in 5 ml of dichloromethane) and 10 ml of water were added at 2.73 ml (24 mmol) of racemic styrene oxide (dissolved in 5 ml of dichloromethane). The mixture was heated to reflux and stirred overnight. After extraction of the aqueous phase with twice 40 ml of chloroform the organic phase was dried over sodium sulphate. After evaporating solvent under reduced pressure and adding 50 ml of heptane to precipitate the solid, the product was separated, purified by recrystallization and identified as the diastereoisomer 1 and the diastereoisomer 2 is liquid.

4.2.2 In presence of silica

An equimolar quantity of racemic styrene oxide and (S)-methyl-benzyl amine (10 mmol) are mixed. It adds 6 g of silica gel dissolved in 20 ml of dichloromethane. The suspension is stirred at reflux of solvent. The evolution of the reaction is followed by TLC. At the end of the reaction (approximately 6 h), add 20 ml of distilled water to the solution. The reaction mixture is returned to reflux for one hour to recover the organic products adsorbed by the silica. After filtering the solid, the organic products are extracted two once 40 ml of dichloromethane then purified by recrystallization in heptane and identified as the diastereoisomer 1 and the diastereoisomer 2 is liquid.

4.2.3 In presence of Lewis acids

An equimolar quantityof racemic styrene oxide and (S)-methyl-benzyl amine (10 mmol) are mixed. It adds 3 equivalents of aluminum chloride dissolved in 20 ml of dichloromethane. The suspension is stirred at reflux of solvent. The evolution of the reaction is followed by TLC. After filtering the solid, the organic products are extracted two once 40 ml of dichloromethane then purified by recrystallization in heptane and identified only the diastereoisomer 2 as liquid.

4.3 2-N[1-phenylethyl] amino-1-phenylethanol 1

This compound was obtained as a solid, mpt: 84–86 °C.

IR (KBr, cm−1): 3300; 1600; 1490; 1450; 1000, 960.

1HNMR: (CDCl3, 250 MHz) 1.40 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 3H), 2.60 (dd, J = 6.8 Hz, 1H), 2.80 (dd, J = 6.8 Hz, 1H), 3.10 (s, 2H, OH and NH); 3.80 (q, J = 6.6 Hz, 1H), 4.70 (dd, J = 6.4 Hz, 1H), 7.20–7.40 (m, 10H, aromatics).

13C NMR: (CDCl3): 24.2 (q), 54.8(t); 57.7 (d); 72.0 (d); 126.3(d); 127.5 (d); 128.2(d); 130.2(d); 144.1 (s); 146.8 (s).

4.4 2-N[1-phenylethyl] amino-2-phenylethanol 2

This compound was obtained as oil.

IR (Film): 3400; 1600; 1490.

1HNMR: (CDCl3, 250 MHz) 1.30 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 3H), 2.90 (s, 2H, OH and NH); 3.55 (m, 2H), 3.80 (q, 1H), 4.10 (m, 1H), 7.15–7.30 (m, 10H, aromatics).

13C NMR: (CDCl3): 24.0 (q), 54.7(t); 61.5 (d); 66.0 (d); 126.1(d); 127.2 (d); 128.0(d); 130.1(d); 141.0 (s); 145.0 (s).