1 Introduction

To ensure drainage of urine from the kidney into the bladder, a stent, name proposed in 1973 by Dr. J. Montie, is placed in the urinary tract. In 1978, Dr. R.P. Finney introduced the “double-J” ureteral stent design, which is curled at both the top and bottom [1]. Usually inserted with the aid of a cystoscope [2], in length it varies between 24 and 30 cm (for adults), and more than 40,000 patients in France benefit from such devices each year.

There are several causes of urinary tract obstruction, but the most common are stone disease [3,4], junction syndrome, and extrinsic compression from nonurologic neoplasms. Several investigations have been focused on interactions between JJ stents and kidney stone concretions [5,6] in humans [7–11] as well as in animals [12]. Because of the presence of incrustations, it is sometimes impossible to withdraw or replace the stent over a guide [13,14]. Moreover, the ability of the stent to prevent duct collapse depends on its compression strength, which decreases as degradation progresses [15]. Thus, as emphasized by several studies [16,17], stent encrustation constitutes a serious complication of ureteral stent use, especially in stone formers. Importantly, Bithelis et al. [18] observed that the mean mass of encrustation in stone formers was larger (71.05 mg) than that in patients without stones (1 mg).

Among the materials used in JJ stents [19–23] are polyurethane [24,25], silicone [26,27], and metallic alloy [28–32]. The coefficient of friction as well as irritation and cell adhesion at the biomaterial–tissue interface [33,34] of stents can be reduced by coatings [35,36]. The aim of this investigation is to assess the physicochemical integrity of JJ stents on which calcifications are present. To this end, the characterization techniques [37–39], Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) [40,41] and field effect scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM) [42], have been used. These have already been successful in determining the chemical composition of biological concretions (see for example Ref. [43]) and describing mesoscopic topology [44]. As clearly shown by Pariente and Conort [45], SEM can be used to visualize the surface of JJ stents. In this article, we also report the uniaxial traction test to evaluate elasticity properties (Young's modulus) of the JJ stents [46].

2 Materials and methods

All 68 JJ stents analyzed in the present study were from Tenon Hospital. We followed the usual procedures. All participants gave their verbal consent, documented by the researchers, for use of the material. Samples were examined without knowledge of the patient's name or other identifying data. Ethical approval was obtained from the ethics committee of Tenon Hospital. The investigation conformed to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

All concretions on the JJ stents were characterized by FTIR (Vector 22; Bruker Spectrospin, Wissembourg, France) according to a previously defined analytical procedure [47,48]. Data were collected in the absorption mode between 4000 and 400 cm−1 with a resolution of 4 cm−1.

An FEI/Philips XL40 environmental FE scanning electron microscope was used for characterization at the mesoscopic scale. Such an environmental scanning electron microscope can image nonconductive materials without any conductive coating and thus permits direct observation with no damage to biological samples. Imaging was performed with a gaseous secondary electron detector, with an accelerating voltage of 20 kV and a water pressure of 0.4 Torr (53.3 Pa) in the chamber.

The mechanical properties were analyzed by uniaxial traction (Adamel Lhomargy DY-30) by placing a millimetric part of the JJ stent between two steel clamping jaws. The initial distance between the two jaws and, hence the initial length of the JJ stent are noted as L0. A hard cylinder with a diameter equal to the internal diameter of the stent was previously inserted at both ends to prevent their compression between the jaws. The displacement is imposed by the operator, and the force F was sampled every 50 ms by a force sensor up to 1 kN. The initial section S of the stent is evaluated through the measurement of the external and internal diameters of the JJ stent with an optical microscope. For elastomers, the elastic modulus E (Young's modulus) should be analyzed using the neo-Hookean model described by

| (1) |

To compare the mechanical properties of the stents and the amount of crystal deposits, we established an incrustation score as described in Table 1.

Scale for scoring encrustations on ureteral double-J stents.

| Score | Definition |

| 0 | No mineral encrustation, no biofilm |

| 1 | Few crystals, or small, well-circumscribed plaques of fine organic encrustation, especially at stent orifices |

| 2 | Some crystals, or more or less extensive plaques of the fine organic film |

| 3 | Fairly numerous locally confluent mineral encrustations, or a fine organic film covering part of the outer and inner surface of stent, and clogging some orifices within this section |

| 4 | Many confluent, but thin, mineral encrustations, or an extensive organic film covering part of outer and inner surface of the stent, and nearly completely clogging orifices within this section |

| 5 | Extensive mineral encrustations, thick in places (1 mm), surrounding part of stent, or an extensive organic film covering part of the outer and inner surfaces, clogging several orifices, and even partially or completely occluding the lumen |

| 6 | Stone formed at the end or on body of stent |

Statistical comparisons relating mechanical parameters, indwelling time, and the chemical content of encrustations were performed using the Mann–Whitney test, multivariate analysis of variance, or chi-square test, when appropriate, with the NCSS statistical package (J. Hintz, Gainesville, FL). A P value of less than 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

3 Results and discussion

Morphological aspects at the macroscopic and mesoscopic scale

Table 2 presents the data for 16 JJ stents examined first by FTIR and FE-SEM for characterization of encrustations.

Selection of biological data corresponding to the 16 different JJ stents selected for this investigation, observed through FE-SEM and FTIR.

| JJ stents | Sex, agea | Pathology | Indwelling time (d) | Encrustation codeb | Composition (%) of encrustations as given by FTIR spectroscopyc |

| 60643 | F, 76 | Lithiasis | 57 | 1K-6B | MAP 60 + AmUr 20 + CA 15 + PROT 5 |

| 60644 | M, 59 | Tumor | 23 | 2K-3B | CA 60 + ACCP 30 + PROT 10 |

| 60646 | M, 54 | Lithiasis | 56 | 3K-4B | COM 85 + PROT 15 |

| 60648 | M, 41 | Lithiasis | 131 | 3K-6B | COD 73 + Br 10 + COM 10 + PROT 5 + OCP 2 |

| 60649 | M, 65 | Tumor of ureter | 28 | 2K-1B | COM 88 + PROT 7 + TRG 5 |

| 60653 | M, 68 | Lithiasis | 76 | 3K-2B | PROT 85 + MPS 10 + COM 5 |

| 60654 | F, 46 | Tumor | 113 | 3K-3B | PROT 75 + MPS 15 + COM 5 + COD 5 |

| 60655 | M, 37 | Lithiasis | 82 | 2K-2B | CA 60 + MAP 30 + PROT 10 |

| 60656 | M, 37 | Lithiasis | 125 | 2K-2B | MAP 50 + CA 25 + PROT 15 + COD 5 + COM 5 |

| 60693 | M, 53 | Hematuria | – | 3K-3B | COM 50 + COD 35 + PROT 15 |

| 60694 | M, 53 | Hematuria | – | 5K-2B | COM 80 + PROT 20 |

| 60698 | F, 37 | Lithiasis | 129 | 1K-5B | CA 70 + AmUr 20 + PROT 10 |

| 60699 | M, 71 | Lithiasis | 69 | 2K-3B | COM 45 + COD 45 + PROT 10 |

| 60700 | M, 51 | Lithiasis | – | 4K-3B | CYS 90 + PROT 10 |

| 60701 | M, 73 | Lithiasis | – | 6K-3B | COM 90 + PROT 10 |

| 60704 | M, 69 | Stenosis | 73 | 1K-1B | COM 80 + PROT 15 + MPS 5 |

a Age is expressed in years.

b Range for encrustation score: 0–6 for kidney (K) and bladder (B).

c ACCP = amorphous carbonated calcium phosphate, AmUr = ammonium hydrogen urate, Br = brushite, CA = Ca phosphate apatite, COD = weddellite, COM = whewellite, CYS = cystine, MAP = struvite, MPS = mucopolysaccharides, OCP = octacalcium phosphate pentahydrate, PROT = proteins, TRG = triglycerides.

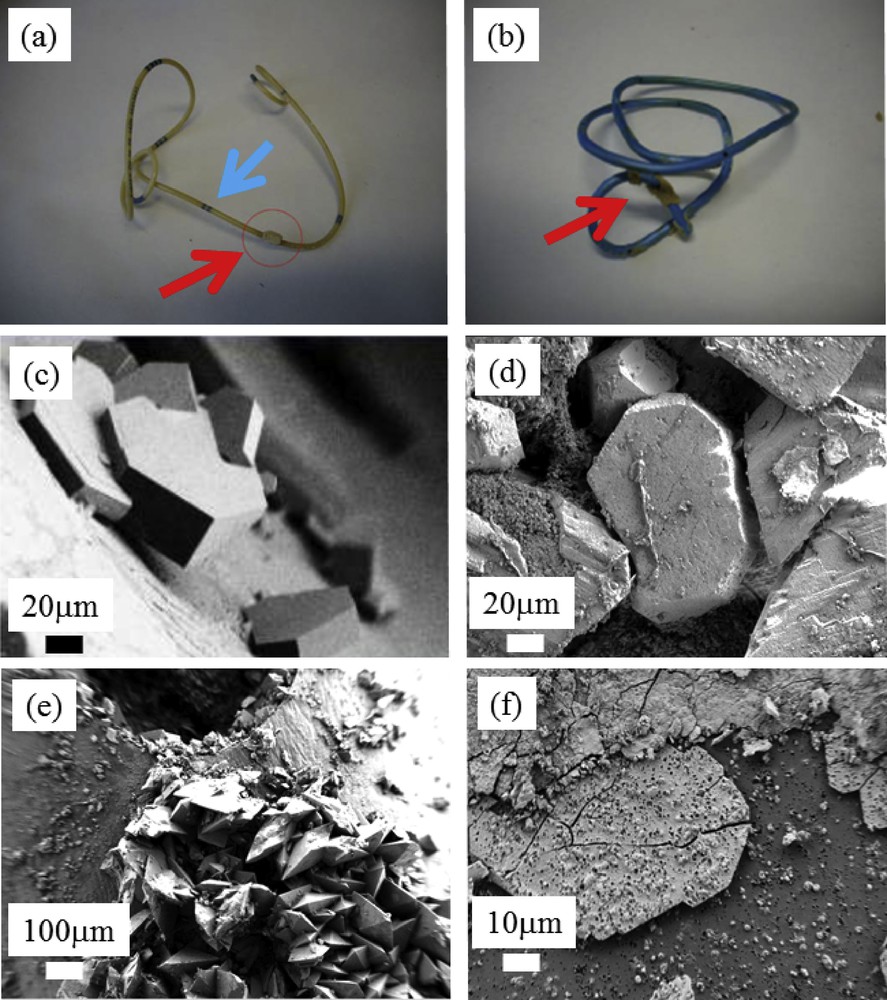

On the macroscopic scale, encrustations may be present in the middle (Fig. 1a) and at the curves (Fig. 1b) of JJ stents (red arrows). Continuous immersion of JJ stents in urine means that encrustations are usually present on the bottom curve. In a previous study, the inner and outer surfaces of the stents were examined under optical microscopy to detect the presence of a biofilm and/or mineral encrustations [16,49]. Encrustations (taken along the stents either by scraping with a scalpel or by using a needle under optical microscopy) were scored on a 0–6 scale (Table 2).

(a and b) Typical encrustations present on JJ stents (red arrows). (c) Cystine crystallites present at the surface of JJ stents. (d) Agglomeration of struvite crystallites, (e) weddellite crystallites, and (f) bacterial imprints present on layers of Ca phosphate apatite.

Observations at the mesoscopic scale give supplementary information on the chemistry of these pathological calcifications. For example, Fig. 1c shows typical cystine crystallites exhibiting flat surfaces with well-defined corners and edges, a result consistent with the hexagonal structure of cystine [50–52]. At this point, we introduce the terms nanocrystals and crystallites as defined by Van Meerssche and Feneau-Dupont [53] to describe the hierarchical structure of these pathological concretions. Crystallites (measuring typically some tens of micrometers) are made up of a collection of nanocrystals (measuring typically some hundreds of nanometers).

Similar observations with respect to crystallites of struvite (Fig. 1d) [54–56] and calcium oxalate dihydrate or weddellite (Fig. 1e) can be made. In Fig. 1f, we can observe bacterial imprints on layers of apatitic calcium phosphate [57,58]. We have previously proposed such an approach in cases of negative urine culture results to highlight the presence of bacteria that may contribute to stone formation.

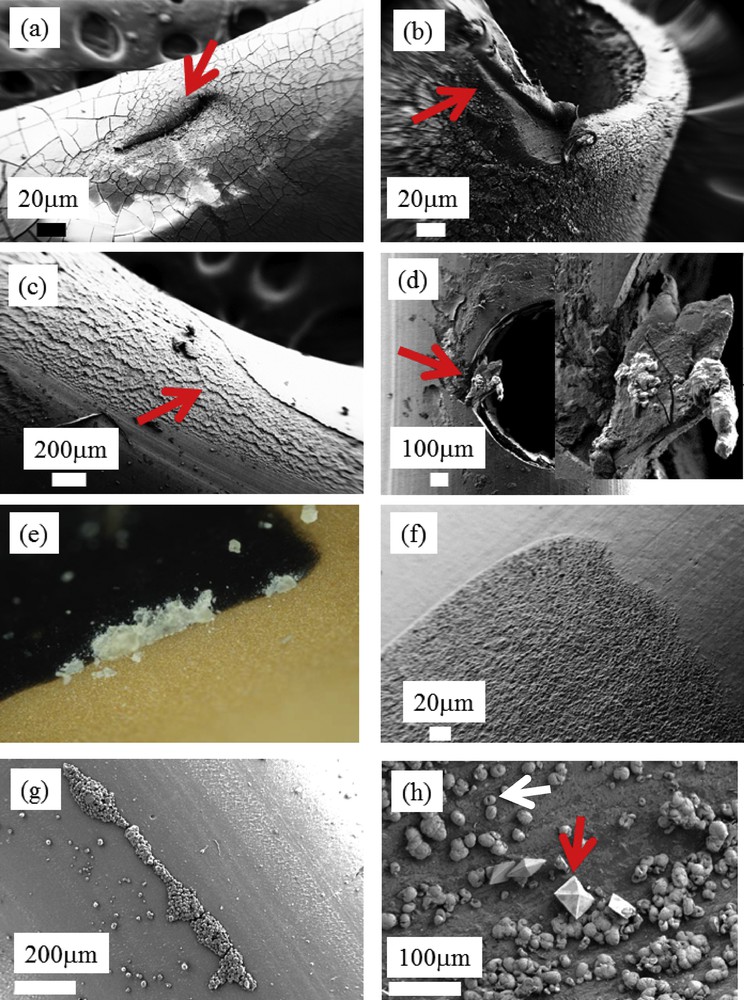

Fig. 2 shows different kinds of structural defects at the surface of JJ stents. Some of them are probably because of manipulations when these devices are positioned between the kidney and the bladder (Fig. 2a and b). In Fig. 2c, it seems that part of the coating is absent. In Fig. 2d, a defect in holes in the JJ stent has clearly played a key role in the formation of the encrustation.

(a–d) Examples of surface defects at the surface of JJ stents. (e) Macroscopic observations of JJ stent. (f) SEM observations of the black marks. (g) Spherical entities made of Ca phosphate apatite along a linear surface defaults. (h) Weddellite (red arrow) and whewellite (white arrow) crystallites coating the JJ stent surface.

To highlight the major role of surface defects in the occurrence of encrustations, we have compared a macroscopic observation (Fig. 2e), in which white deposits on the black marks on the surface of JJ stents (blue arrow on Fig. 1a) are visible, and microscopic observations of these same marks (Fig. 2f). Importantly, note the high surface roughness of the marks. It seems that this step in the fabrication of the stents significantly modifies the surface, leading to a significant nidus for encrustation.

Finally, Fig. 2g shows an encrustation, which follows the linear defects present at the surface of a JJ stent.

Mechanical properties

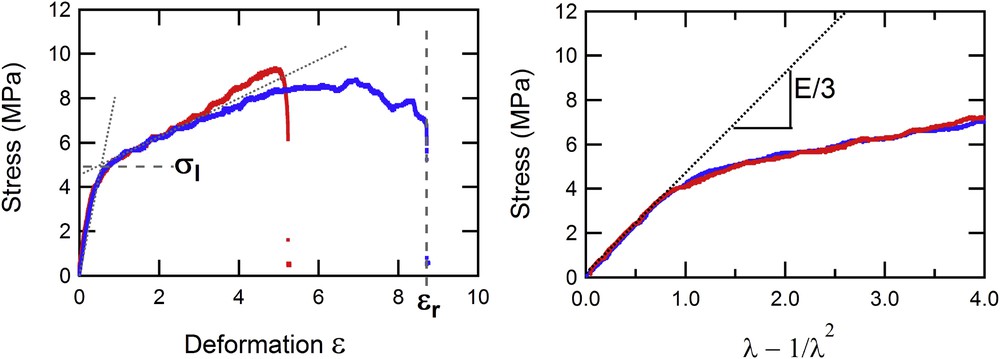

As for the mechanical analysis, Fig. 3 shows the relationship between the stress and deformation, or the “λ-function.” The two experiments shown in Fig. 3 were performed on the same stent (N57614) but in the presence (in red) or absence (in blue) of a hole.

Evolution of the stress (in MPa) measured on two parts of a stent (with or without a hole) vs the deformation ɛ (left) and the λ-function (right).

The properties appear identical whether a hole is present or not, except for the maximal deformation ɛr tolerated by the stent before its rupture, which are 525 and 875%, respectively. This maximal deformation is always higher, in every case, in the absence of a hole. This can be readily understood by the fact that the presence of a hole on the stent causes a stress concentration area on its periphery that can weaken the material. The first phase, corresponding to elastic behavior of the stent, is exactly the same in this representation because the force is normalized, in the definition of stress, by the actual section of the stent. From this phase, we can extract the Young modulus, E, which is related to the slope of these curves by Eq. (1). We can also define the limit of elasticity, σl, which corresponds to the end of the elastic behavior and the beginning of the plastic phase where irreversible damage occurs in the material. In this typical experiment on a widely used stent, we notice that the limit of elasticity is not particularly high (close to 5 MPa), corresponding to a force close to 10 N, thus an applied mass of roughly 1 kg.

Table 3 presents all the data from the 52 JJ stents, which were investigated for their mechanical properties.

Selection of biological data corresponding to the 52 different stents used for mechanical analysis.

| Stent | Sex, agea | Pathology | Indwelling time (d) | Encrustation codeb | Composition (%) of encrustations as given by FTIR analysisc |

| N32782 | M, 38 | Lithiasis | 25 | 3K-2B | COD 73 + PROT 12 + COM 10 + Br 3 + CA 2 |

| N32998 | M, 45 | Lithiasis | 73 | 2K-2B | COD 85 + PROT 10 + CA 5 |

| N33213 | F, 51 | Tumor | 55 | 1K-1B | COM 80 + PROT 15 + CA 5 |

| N33220 | F, 49 | Tumor | 96 | 2K-2B | AU2 60 + AU0 20 + COM 13 + PROT 5 + CA2 |

| N33414 | F, 75 | Tumor | 186 | 2K-2B | COM 85 + PROT 15 |

| N33880 | M, 30 | Lithiasis | 25 | 2K-1B | COM 80 + PROT 16 + CA 4 |

| N42481 | M, 30 | Lithiasis | 51 | 2K-6B | CYS 70 + PROT 20 + CA 10 |

| N42894 | M, 67 | Lithiasis | 81 | 1K-0B | PROT 50 + MPS 30 + COM 12 + COD 8 |

| N42928 | M, 47 | Lithiasis | 66 | 1K-3B | COD 75 + COM 15 + PROT 10 |

| N43196 | F, 51 | Graft | 38 | 2K-1B | PROT 80 + MPS 20 |

| N43198 | M, 72 | Graft | 60 | 0K-1B | PROT 75 + MPS 25 |

| N43321 | F, 22 | Lithiasis | 60 | 5K-5B | CA 40 + MAP 30 + ACCP 15 + AmUr 10 + PROT 5 |

| N43329 | M, 66 | Lithiasis | 9 | 1K-0B | PROT 85 + COM 15 |

| N43362 | M, 67 | Lithiasis | 45 | 1K-0B | PROT 45 + COM 25 + MPS 15 + CA 10 + ACCP 5 |

| N43381 | M, 40 | Lithiasis | 20 | 1K-1B | COM 60 + PROT 25-MPS 15 |

| N43384 | M, 34 | Lithiasis | 144 | 1K-0B | CA 60 + PROT 20 + COM 10 + COD 5 + AU2 5 |

| N43386 | F, 31 | Lithiasis | 47 | 1K-1B | COM 70 + PROT 25 + MPS 5 |

| N43593 | M, 57 | Lithiasis | 20 | 1K-1B | PROT 60 + MPS 30 + COM 10 |

| N43596 | M, 49 | Tumor | 150 | 1K-1B | PROT 75 + MPS 25 |

| N43629 | M, 50 | Lithiasis | 8 | 1K-1B | PROT 55 + COD 30 + MPS 15 |

| N43632 | F, 64 | Lithiasis | 54 | 2K-2B | COM 90 + PROT 10 |

| N43651 | M, 41 | Lithiasis | 18 | 1K-2B | COM 60 + PROT 20 + MPS 10 + COD 10 |

| N43657 | M, 30 | Lithiasis | 42 | 2K-1B | CYS 90 + PROT 10 |

| N43659 | M, 40 | Lithiasis | 42 | 5K-4B | COD 80 + PROT 15 + CA 5 |

| N43665 | M, 68 | Lithiasis | 75 | 2K-1B | CYS 80 + ACCP 10 + PROT 10 |

| N43754 | F, 76 | Lithiasis | 35 | 4K-4B | CA 60 + MAP 25 + ACCP 10 + PROT 5 |

| N45258 | M, 55 | Lithiasis | 15 | 1K-1B | COD 70 + PROT 20 + MPS 10 |

| N45370 | M, 47 | Graft | 45 | 2K-2B | AU0 40 + COM 30 + PROT 20 + MPS 10 |

| N45371 | M, 33 | Tumor | 41 | 2K-2B | COM 55 + MPS 30 + PROT 15 |

| N45372 | M, 66 | Graft | 20 | 1K-1B | PROT 50 + MPS 30 + COM 15 + COD 5 |

| N45373 | F, 25 | Graft | 18 | 1K-0B | PROT 50 + MPS 40 + COM 10 |

| N45398 | M, 23 | Lithiasis | 74 | 4K-5B | AU0 65 + AU2 20 + PROT 10 + COM 5 |

| N45402 | M, 31 | Lithiasis | 77 | 3K-4B | CYS 70 + PROT 20 + MPS 8 + CA 2 |

| N45550 | M, 39 | Lithiasis | 30 | 1K-2B | COM 50 + PROT 30 + MPS 20 |

| N45552 | M, 59 | Lithiasis | 225 | 2K-3B | COM 75 + PROT 25 |

| N45663 | F, 69 | Lithiasis | 10 | 2K-1B | COD 65 + COM 20 + PROT 15 |

| N45664 | F, 35 | Graft | 24 | 1K-1B | PROT 85 + MPS 15 |

| N45799 | M, 42 | Lithiasis | 45 | 1K-2B | COM 70 + PROT 20 + MPS 10 |

| N45928 | M, 72 | Lithiasis | 77 | 1K-0B | PROT 65 + COM 20 + MPS 15 |

| N57447 | M, 67 | Tumor | 111 | 2K-3B | PROT 60 + MPS 20 + COM 15 + COD 5 |

| N57482 | M, 45 | Lithiasis | 63 | 1K-3B | COM 70 + COD 20 + PROT 10 |

| N57561 | M, 58 | Lithiasis | 62 | 2K-1B | COM 45 + COD 25 + PROT 15 + MPS 10 + CALC 5 |

| N57614 | F, 36 | Lithiasis | 53 | 3K-4B | COM 65 + COD 25 + PROT 10 |

| N57780 | F, 37 | Lithiasis | 65 | 2K-2B | CA 35 + COM 25 + COD 15 + PROT 15 + MPS 10 |

| N57783 | M, 28 | Lithiasis | 120 | 1K-2B | COM 45 + COD 30 + PROT 15 + MPS 10 |

| N57786 | M, 70 | Tumor | 91 | 2K-2B | COM 50 + COD 25 + PROT 15 + MPS 10 |

| N59747 | F, 26 | Lithiasis | 36 | 4K-4B | CA 50 + COM 35 + PROT 15 |

| N59766 | M, 62 | Lithiasis | 10 | 2K-2B | COM 60 + PROT 30 + CA 5 + MPS 5 |

| N59768 | M, 66 | Lithiasis | 28 | 3K-5B | MAP 45 + CA 35 + ACCP 10 + PROT 10 |

| N59772 | M, 60 | Lithiasis | 13 | 2K-2B | PROT 75 + MPS 15 + COM 10 |

| N59783 | M, 54 | Lithiasis | 26 | 3K-3B | COM 65 + PROT 35 |

| N60361 | M, 35 | Lithiasis | 24 | 1K-4B | CYS 80 + PROT 15 + COM 5 |

a Age is expressed in years.

b Range for encrustation score: 0–6 for kidney (K) and bladder (B).

c ACCP = amorphous carbonated calcium phosphate; AmUr = ammonium hydrogen urate; AU0 = anhydrous uric acid; AU2 = uric acid dihydrate; Br = brushite; CA = Ca phosphate apatite; CALC = calcite; COM = whewellite; COD = weddellite; CYS = cystine; MAP = struvite; MPS = mucopolysaccharides; PROT = proteins; TRG = triglycerides.

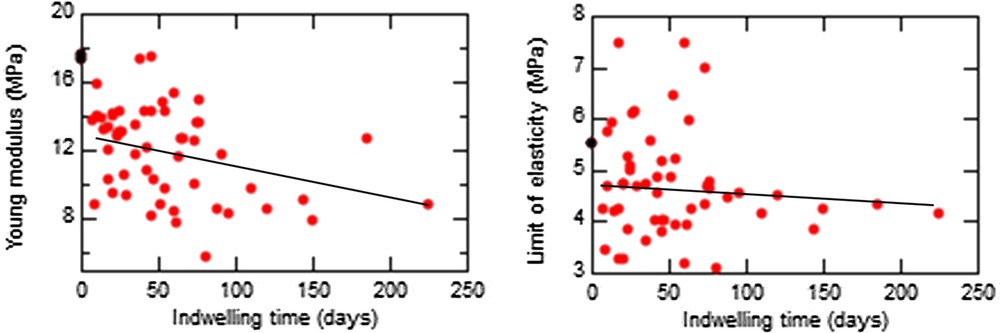

In Fig. 4, we have represented the evolution of the Young modulus and the limit of elasticity for different stent indwelling times, irrespective of pathology. The mean values for these two parameters were

Evolution of the Young modulus (left) and the limit of elasticity (right) vs the indwelling time of different stents (black, unused stent; red, used stents).

As expected, the encrustation score was time-dependent, the mean indwelling time increasing from 42.9 d for a score of 1 to 128.7 d for a score of 3 (P = 0.03). An exception was found for encrustations containing struvite, a marker of urinary tract infection because of bacterial urea catabolism. In such cases, the encrustation score was high (4 or 5) for an indwelling time around 47 d.

Interestingly, the limit of elasticity was influenced by the level of encrustation, increasing from 3.89 to 5.53 MPa when the encrustation score increased from 1 to 5 (P = 0.0073).

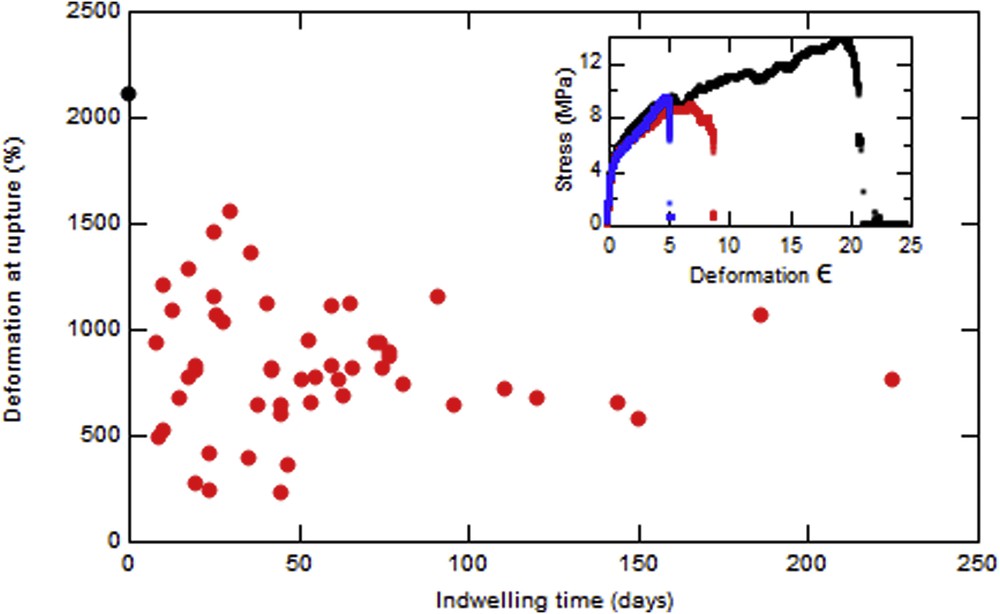

Fig. 5 represents the evolution with time of the relative deformation at rupture (deformation at rupture normalized by the deformation at rupture of the unused stent) for different stents with no hole between jaws. The mean value of this maximal deformation is 39% of that for an unused stent where no hole is present and reduces to 23% at a hole. The inset shows that the maximal deformation for an unused stent is 2100%. The initial behavior of the probe is exactly the same except that it will rupture earlier. We can also notice that if the applied stress goes higher than 10 MPa the stent breaks immediately. The relative deformation at rupture is independent of indwelling time.

Evolution of the maximal deformation before rupture vs the indwelling time of different stents with no hole. Inset: Evolution of stress with the deformation for an unused stent (black), a used stent without hole (red), and a used stent with hole (blue).

4 Conclusion and perspectives

This investigation has focused on JJ stents to assess their surface characteristics and their elastic properties. The complete data establish that several kinds of surface defects exist, probably related to manipulation and/or fabrication procedures. An important finding is that black marks on the surface of the stents, for the purpose of guiding the urologist during the medical procedure, correspond to very rough surfaces. Such roughness may favor the formation of encrustations. Regarding the elastic properties, this first set of measurements indicates that the mechanical strength is strongly reduced whatever the indwelling time and the presence of holes along the stent heightens this effect. This could be a serious problem when removing the stent, although no change is observed at the elastic phase.

JJ stents are currently in widespread use. As encrustations are a major limitation of such medical devices, we believe in approaches such as ours, combining studies of surface state with measurements of elastic properties, can be used to develop new devices and help to select better performance materials.

Vous devez vous connecter pour continuer.

S'authentifier