1 Introduction

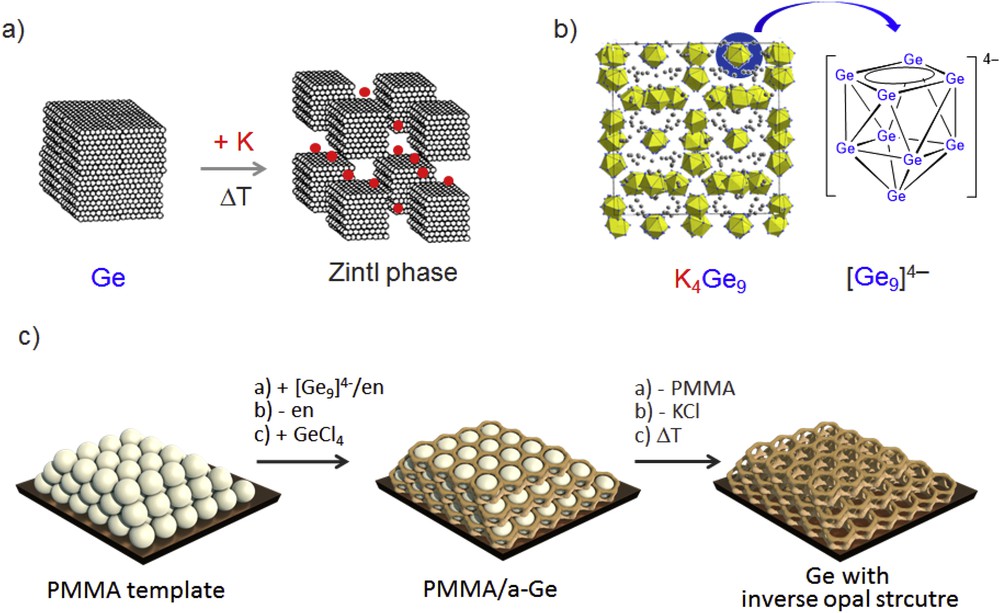

A distinctive combination of chemical synthetic protocols for a metamorphosis of the heavier tetrel and pentel elements has been developed over the years. The formation of small charged atom clusters—so-called Zintl clusters—obtained by reacting the respective elements with alkali metals provides precursors for numerous new compounds [1]. In the case of the deltahedral polyanions of tetrel elements Ge, Sn, and Pb, the respective clusters have a good solubility in very polar aprotic solvents. Such nine-atomic clusters provide a source of an “activated” element for the fabrication of novel morphologies such as germanium in the form of an inverse opal structure (Fig. 1) [2].

Formation of a Zintl phase by the reaction of an alkali metal element with a p-block (semi)metal. (b) The Zintl phase K4Ge9 comprises discrete [Ge9]4− cluster anions. (c) Formation of elemental germanium with a novel morphology. Impregnating a PMMA template structure with a [Ge9]4−/en solution, cluster linking/oxidation with GeCl4, and removal of KCl and PMMA results in mesostructured Ge. PMMA, polymethylmethacrylate; en, ethylenediamine.

Therefore, resourcing of capable main-group-element-rich molecules is a synthetic challenge. By adding various organic groups the polyanions reduce their charge and thus allow better solubility in a larger variety of organic solvents. Recently, equipping these Zintl ions with organic groups opened a new field at the border of solid-state chemistry and solution-based reactions of main-group-element-rich molecules [3]. In this context, especially [Ge9]4– Zintl clusters show multifaceted reactivity toward transition metal compounds and are capable of attaching organic ligands or can undergo follow-up reactions.

The Zintl phases A4Ge9 (A = K, Rb) can be easily dissolved in polar solvents, such as ethylenediamine, pyridine, and liquid ammonia [4]. At a maximum, twofold functionalized Ge9 clusters can be obtained from ethylenediamine solutions. The first exo-Ge9–C bond was obtained in [Ph−Ge9−SnPh]2− [3a]. Simple nucleophilic substitution reaction of Ge94− with alkyl halides resulted in several organofunctionalized deltahedral Ge9 cluster anions of the form [R–Ge9–Ge9–R]2− and [Ge9R2]2− in small amounts [5]. The organofunctionalization was further extended to alkenylated cluster entities by a rather complex reaction of Ge94− with alkynes in ethylenediamine [5a,6]. The most prominent examples are given by the vinylated clusters [Ge9(CHCH2)n](4−n)− [7]. The substitution of simple alkynes by dialkynes leads to the isolation of the so-called Zintl triads [RGe9–CHCH–CHCH–Ge9–R]4− and [Ge9–CHCH–CHCH–Ge9]6− [8]. Due to unforeseen reactions of the deltahedral Ge9 clusters in ethylenediamine, the focus of research was set more toward reactions of the latter in convenient solvents.

In 2003, Schnepf [3c] reported the soluble anion [Ge9(Si(SiMe3)3)3]−, which was synthesized by treating metastable Ge(I) bromide with Li[Si(SiMe3)3]. This complex way of synthesizing the threefold silylated Ge9 cluster was replaced by the Zintl-route-synthesis, which was developed by Li and Sevov [9], wherein a heterogeneous reaction K4Ge9 is treated with 3 equiv of chlorotris(trimethylsilyl)silane in acetonitrile to form [Ge9(Si(SiMe3)3)3]−. From this anion numerous new compounds emerged and new reactivities of the Ge9 Zintl cluster were discovered. The attachment of organic moieties and the accompanied introduction of specific functionalities, as is realized in H2CCH(CH2)nGe9{Si(SiMe3)3}3 (n = 1, 3), have been reported. For these compounds fluctuation in solution at rt was observed, which is most likely caused by labile-bound silyl ligands or a dynamic cluster framework [10].

Besides, specifically functionalized Ge9 anions have been achieved by using less sterically demanding silyl ligands, which carry terminal double bonds, for example, [H2CCH(CH2)nPh2SiGe9{Si(SiMe3)3}2]− (n = 1,2) [11].

Also, the coordination of [Ge9{Si(SiMe3)3}3]− to transition metals and linkage of two cluster units by coordination to transition metals have been accomplished [12]. Even the neutral organofunctionalized cluster CH3CH2Ge9{Si(SiMe3)3}3 is capable of coordinating to late transition metals forming the closo-cluster Pd(PPh3)(CH3CH2)Ge9{Si(SiMe3)3}3 [13].

Only recently, Kysliak and Schnepf developed a synthesis route for the disilylated Ge9 cluster [Ge9{Si(SiMe3)3}2]2−. Remarkably, [Ge9{Si(SiMe3)3}2]2− is formed by reaction of [Ge9{Si(SiMe3)3}3]− with K4Ge9, which enforces the assumption that the silyl ligands are weakly bound to the Ge9 core [14]. So far, the monosilylated Ge9 cluster anion [Ge9{Si(SiMe3)3}]3− has not been reported.

[Ge9{Si(SiMe3)3}2]2− and [Ge9{Si(SiMe3)3}3]− readily react with dialkylphosphines R2PCl to form the species [Ge9{Si(SiMe3)3}2R2P]− and [Ge9{Si(SiMe3)3}3R2P], respectively [15]. Linkage of two [Ge9{Si(SiMe3)3}2]2− entities has been realized in [{Si(SiMe3)3}2Ge9–SiMe2–(C6H4)–SiMe2–Ge9{Si(SiMe3)3}2]2− [16].

Herein we present the addition of an ethyl functionality to [Ge9{Si(SiMe3)3}2]2− by the reaction of the latter with bromoethane in acetone. The resulting anion [CH3CH2Ge9{Si(SiMe3)3}2]− was characterized by NMR spectroscopy and electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI MS). In addition, we present the first monosilylated Ge9 cluster compound carrying an additional ethyl group, which was obtained by addition of 2,2,2-crypt to an acetone solution of [CH3CH2Ge9{Si(SiMe3)3}2]−. The compound was crystallized as [K(2,2,2-crypt)]2[CH3CH2Ge9Si(SiMe3)3] and characterized by single crystal X-ray crystallography, NMR spectroscopy, and elemental analysis.

2 Discussion

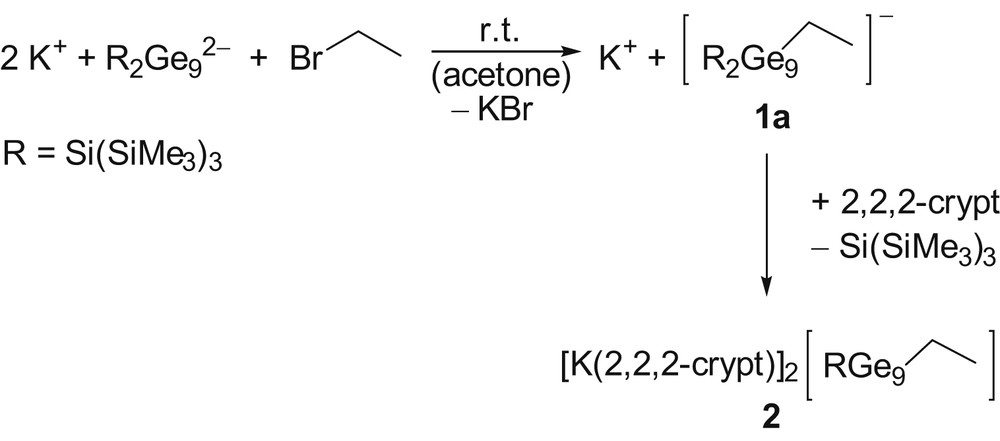

[Ge9{Si(SiMe3)3}2]2− undergoes a nucleophilic substitution reaction with bromoethane exclusively in THF or acetone to form the species [CH3CH2Ge9{Si(SiMe3)3}2]− (1a), which was unequivocally shown by ESI MS and NMR spectroscopy (Scheme 1, for NMR spectra see Fig. S1 of Supporting information).

Reaction of K2[Ge9{Si(SiMe3)3}2] with bromoethane yielding the anion 1a and subsequent reaction to 2.

The obtained mass spectrum of 1a is shown in Fig. 2 and matches the m/z ratio as well as the isotopic pattern of the simulated mass spectrum of the anion [CH3CH2Ge9{Si(SiMe3)3}2]−.

ESI mass spectrum of a THF solution of 1 and predicted structure of 1a. The measured spectrum of [CH3CH2Ge9{Si(SiMe3)3}2]− (1a) is shown in black. The simulated spectrum is shown as bar graph in red. (For further information see Fig. S2 of Supporting information).

Despite the addition of various counter ions, [CH3CH2Ge9{Si(SiMe3)3}2]− could not be crystallized. In case of the addition of 2,2,2-crypt to an acetone solution containing “K[CH3CH2Ge9{Si(SiMe3)3}2]” (1) with the aim of sequestering K+, the abstraction of one silyl ligand occurred. The peaks in the 1H NMR spectrum of the residue of the reaction mixture after evaporating the solvent and dissolution in acetone-d6 show an integral ratio of 27:2:3 for –Si{Si(CH3)3}3, CH2, and CH3 groups, respectively (Supporting information, Fig. S3). The residue was redissolved in acetone and stored at −32 °C for crystallization. Red-brown needle-shaped crystals were obtained. Compound 2 is not stable in the gas phase whereby ESI mass spectra of 2 are not available.

The unit cell of [K(2,2,2-crypt)]2[CH3CH2Ge9Si(SiMe3)3] (2) contains two entities of 2a and four potassium ions complexed with 2,2,2-crypt (Supporting information, Fig. S5). This is consistent with the twofold negatively charged Ge9 cluster entity 2a (Fig. 3). Each cluster is equipped with one silyl group and an ethyl moiety. Compound 2a contains a nearly C2v symmetric Ge9 cluster core with one open face, and thus, is very similarly shaped to so far reported twofold-substituted Ge9 Zintl clusters. The Ge–Ge distances within the cluster core range from 2.519(2) (for Ge3–Ge4) to 2.939(2) Å (for Ge5–Ge6), and are typical of twofold-substituted Ge9 Zintl clusters [6d,7a]. The attachment of ligands to the two atoms Ge1 and Ge3, which are located at the open face Ge1–Ge2–Ge3–Ge4, leads to compression of the Ge distances terminating the open face as compared to those forming the capped square. The Ge1–Si1 distance of 2.423(2) Å is longer than in the crystal structures of [Ge9{Si(SiMe3)3}2]2− (d(Ge–Si) = 2.4097(9) and 2.4071(9) Å) [14] and [Ge9{Si(SiMe3)3}3]− (d(Ge–Si) = 2.363(2)–2.369(1)Å) [9]. The Ge–Si distance integrates well in this series. The more silyl groups are bound to the cluster the stronger the Ge–Si bond. The Ge3–C1 distance of 2.02(1) Å compares well with the Ge–C distance of 1.973(4) Å in CH3CH2Ge9{Si(SiMe3)3}3 [10a]. Remarkably, the hypersilyl ligand does not point radially away from the cluster core, as is the case for the silyl ligands in the crystal structures of [Ge9{Si(SiMe3)3}2]2− and [Ge9{Si(SiMe3)3}3]− but lies in the plane Ge1–Ge2–Ge3–Ge4 (Supporting information, Fig. S6).

The twofold negatively charged anion 2a. All non-hydrogen atoms are shown as ellipsoids at a probability level of 50%. All hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity.

In a next step, we further investigated the desilylation of compound 1 by addition of 18-crown-6. The addition of 18-crown-6 to the reaction solution did not lead to the abstraction of one silyl group as was the case for 2,2,2-crypt (Supporting information, Fig. S7). This was shown by the integral ratio of 54:2:3 for Si(Si(CH3)3)3, CH2, and CH3 of the 1H NMR spectrum of the reaction solution. Nevertheless crystallization of 1a was not successful using 18-crown-6 as a sequestering agent. Presumably, due to the nitrophilicity of the silicon the abstraction of silyl groups is favored when amines like 2,2,2-crypt are present in the solution. Desilylation reactions for germanides have been reported before. Especially KOtBu and fluorides, for example, acyl fluorides have been applied as effective reagents to abstract silyl groups [17].

3 Conclusions

We present a synthetic method for a stepwise ligand exchange reaction at a Zintl ion. The selective organofunctionalization of [Ge9{Si(SiMe3)3}2]2− via the nucleophilic substitution reaction with bromoethane in acetone results in the first step in the anion [CH3CH2Ge9{Si(SiMe3)3}2]−. Upon addition of 2,2,2-crypt to the solution desilylation occurs and one silyl ligand is abstracted, which leads to the isolation of the compound [K(2,2,2-crypt)]2[CH3CH2Ge9Si(SiMe3)3]. The latter represents the first monosilylated Ge9 Zintl cluster. The fact that silyl ligands are weakly bound and can be selectively abstracted might lead to a wide range of interesting structures, which contain deltahedral Ge9 clusters with several different ligands.

4 Experimental section

4.1 General

All manipulations were carried out under a purified argon atmosphere using standard Schlenk techniques. The Zintl phase with the nominal composition K4Ge9 was synthesized by heating a stoichiometric mixture of the elements K and Ge (99.999%, Chempur) at 650 °C for 46 h in a stainless steel autoclave [18]. Anhydrous acetone was purchased from VWR Chemicals and stored over molecular sieve (3 Å) for at least 1 day. Chlorotris(trimethylsilyl)silane (≥95.0%, TCI Chemicals) and bromoethane (98%, Sigma–Aldrich) were used as received. 2,2,2-Crypt (Merck) was dried in vacuum for 8 h. 18-Crown-6 (Merck) was sublimed in vacuum. The solvents, acetonitrile and toluene, were obtained from a solvent purificator (MB-SPS). Acetonitrile was stored over molecular sieve (3 Å). The deuterated solvents acetonitrile-d3 and acetone-d6 were purchased from Deutero GmbH and stored over molecular sieve (3 Å) for at least 1 day.

4.2 Synthesis of K2[Ge9{Si(SiMe3)3}2]

K2[Ge9{Si(SiMe3)3}2] was synthesized according to a modified literature procedure [14]. In a glovebox K4Ge9 (739 mg, 0.91 mmol) was weighed and introduced into a Schlenk flask and a solution of chlorotris(trimethylsilyl)silane (517 mg, 1.82 mmol) in 24 mL acetonitrile was added. The suspension was stirred at rt for 13 days. After filtering the reaction solution the solvent was evaporated in vacuo. The residue was washed three times with a total amount of 22 mL toluene and the residue was dried in vacuo. An orange solid (518 mg) was obtained. The NMR data match with those reported in the literature.

4.3 Synthesis of K[CH3CH2Ge9{Si(SiMe3)3}2] (1)

For NMR spectroscopic investigations of 1, K2[Ge9{Si(SiMe3)3}2] (30 mg, 0.024 mmol) was treated with a solution of bromoethane (1.8 μL, 0.024 mmol) dissolved in 0.6 mL acetone-d6. The deep-brown reaction solution was stirred for 21 h at rt and characterized by NMR spectroscopy. 1H NMR (400 MHz, acetone-d6, 298 K): δ (ppm) 1.28 (m, 2H, CH2 on ethyl), 1.18 (m, 3H, CH3 on ethyl), 0.25 (s, 54H, CH3 on hypersilyl); 29Si NMR (79 MHz, acetone-d6, 298 K): δ (ppm) −9.38 (Si(CH3)3), −108.56 (Si{Si(CH3)3}3); 13C NMR (101 MHz, acetone-d6, 298 K): δ (ppm) 20.44 (q, CH3), 4.10 (t, CH2), 3.12 (q, CH3 on hypersilyl); 1H 1H COSY (400 MHz, acetone-d6, 298 K): δ (ppm)/δ (ppm) 1.27/1.19 (3J, CH2/CH3); 1H 13C HSQC (400 MHz/101 MHz, acetone-d6, 298 K): δ (ppm)/δ (ppm) 1.28/4.07 (1J, CH2/CH2), 1.19/20.40 (1J, CH3/CH3), 0.25/3.13 (1J, CH3 on hypersilyl/CH3 on hypersilyl); 1H 13C HMBC (400 MHz/101 MHz, acetone-d6, 298 K): δ (ppm)/δ (ppm) 1.30/20.34 (2J, CH2/CH3), 1.17/4.15 (2J, CH3/CH2); ESIMS (negative ion mode, 4500 V, 300 °C): m/z 1179 [CH3CH2Ge9{Si(SiMe3)3}2]−.

4.4 Synthesis of {[K(222-crypt)]2 2a} (2)

K2[Ge9{Si(SiMe3)3}2] (140 mg, 0.11 mmol) was weighed and introduced into a Schlenk tube and a solution of bromoethane (8.5 μL, 0.11 mmol) in 3 mL acetone was added. The reaction solution was stirred for 23 h at rt. After filtering through a glass fiber filter 2,2,2-crypt (86 mg, 0.23 mmol) was added to the red-brown reaction solution. The solvent was evaporated in vacuo to obtain a dark oil, which was characterized by NMR spectroscopy. The oil was dissolved in 0.5 mL acetone and stored at −32 °C for 5 days to obtain 15 mg of red-brown needle-shaped crystals suitable for X-ray crystallography (yield 8%). For NMR spectroscopic investigations of 2, the crystals were separated from the mother liquor, washed three times with a total amount of 3 mL hexane, and dried at ambient conditions. The crystals were dissolved in acetonitrile-d3 (for NMR spectra see Fig. S4 of Supporting information). 1H NMR (400 MHz, acetonitrile-d3, 298 K): δ (ppm) 3.56 (s, crypt), 3.52 (m, crypt), 2.52 (m, crypt), 0.91 (m, 3H, CH3 on ethyl), 0.82 (m, 2H, CH2 on ethyl), 0.09 (s, 27H, CH3 on hypersilyl); 1H 1H COSY (400 MHz, acetone-d6, 298 K): δ (ppm)/δ (ppm) 0.91/0.81 (3J, CH3/CH2) elemental analysis calcd (%): C, 32.04; H, 5.95. Found: C, 31.41; H, 5.93.

4.5 X-ray data collection and structure determination

A few crystals of 2 were transferred from the mother liquor into perfluoropolyalkylether under a cold N2 stream. A single crystal was fixed on a glass fiber and positioned in a 150 K cold N2 stream. The single-crystal intensity data were recorded on a Stoe StadiVari diffractometer (Mo Kα radiation (λ = 0.71073), Pilatus 300K detector), by using the X-Area software package [19]. The crystal structure was solved by direct methods using the SHELX software [20]. The position of the hydrogen atoms was calculated and refined using a riding model. All non-hydrogen atoms were treated with anisotropic displacement parameters. Crystallographic details of compound 2 are listed in Table 1. CCDC 1826538 contains the supplementary crystallographic data. These data can be obtained free of charge from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif. The presence of the elements Si, Ge, and K in the measured single crystal was confirmed by energy dispersive X-ray analysis.

Crystallographic details on 2.

| Compound | 2 |

| Formula | C47H104Ge9K2N4O12Si4 |

| Formula weight (g mol−1) | 1761.21 |

| Space group (no) | P21 (4) |

| a (Å) | 14.682 (1) |

| b (Å) | 15.226 (2) |

| c (Å) | 16.993 (2) |

| α (deg) | 90 |

| β (deg) | 90.878 (8) |

| γ (deg) | 90 |

| V (Å3) | 3798.3 (7) |

| Z | 2 |

| T (K) | 150 (2) |

| λ (Å) | 0.71073 |

| ρcalcd (g cm−3) | 1.410 |

| μ (mm−1) | 3.730 |

| Collected reflections | 84,219 |

| Independent reflections | 14,793 |

| Rint | 0.066 |

| parameters/restraints | 714/0 |

| R1 [I > 2σ(I)/all data] | 0.041/0.068 |

| wR2 [I>2σ(I)/all data)] | 0.076/0.092 |

| Goodness of fit | 1.106 |

| max./min differential electron density | 0.89/−0.77 |

4.6 Energy-dispersive X-ray analysis

The presence of the elements K, Si, and Ge in the single crystal of 2, which was used to determine the crystal structure, was confirmed using a Hitachi TM-1000 tabletop microscope.

4.7 Elemental analysis

Elemental analysis was performed by the microanalytical laboratory at the Department of Chemistry of the Technische Universität München. The elements C, H, and N were determined using a combustion analyzer (Elementar Vario EL, Bruker Corp.).

4.8 NMR spectroscopy

NMR spectra were recorded using a BRUKER Avance Ultrashield AV400 spectrometer. The signals were referenced to the residual proton signal of the deuterated solvents acetone-d6 (δ = 2.05 ppm) and acetonitrile-d3 (δ = 1.94 ppm). The chemical shifts are given in δ values in parts per million (ppm).

4.9 Electrospray ionization mass spectrometry

For ESI mass spectrometric investigations samples were prepared as described in Section 4, except instead of the deuterated solvent nondeuterated ones were used. After the reaction time the solvent was removed. A small amount of the residue was characterized by NMR spectroscopy. The residue was then dissolved in THF and filtered through a glass fiber filter. The measurements were carried out on an HCT (Bruker Corp.). The dry gas temperature was adjusted to 125 °C and the injection speed to 240 μL s−1. The measurements were carried out in the negative ion mode.

Acknowledgments

S.F. is grateful to the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie for her fellowship. The authors thank the “Bayerische Staatsministerium für Wirtschaft und Medien, Energie und Technologie” within the program “Solar Technologies go Hybrid” for the financial support. The authors further acknowledge Kevin Frankievicz, B.Sc., for preparation of reaction solutions.