1 Introduction

Ultrasonic energy can clean or homogenize materials, accelerate both physical and chemical reactions [1]. The utilization of ultrasound energy in organic chemistry has been better known from the 1970s [2]. The use of ultrasound in chemical reactions in solution provides specific activation based on a physical phenomenon: acoustic cavitation [3]. Cavitation induces very high local temperatures and pressure inside bubbles (cavities), leading to a turbulent flow in the liquid and enhanced mass transfer [4]. Pyridazinone derivatives have been reported to possess a wide variety of biological activities like antidiabetic [5], anticancer [6] anti-AIDS, antihypertensive [7], antimicrobial [8], fungicida [9], herbicida [10], antifeedant [11], antiplatelet [12], analgesic, anti-inflammatory [13] and anticonvulsant activities [14]. The cyclopropane ring is a main structural part in many synthetic and natural compounds that exhibit a wide range of biological activities from enzyme inhibition to antibiotic, herbicidal, antitumor, and antiviral properties [15]. Cyclopropane derivatives have shown potent HIV antiviral activities as non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors [16]. Due to diversity of cyclopropane containing compounds with biological activity, chemists have tried to find novel and facile methods for synthesis of these compounds [17]. In this article, we describe the results obtained for the regiospecific synthesis of pyrazolines by 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition of 2-diazopropane with pyridazine-3,6-dione derivatives. To the best of our knowledge, there are no literature examples for synthesis of cyclopropanes by ultrasonication. Herein, we wish to report a facile sonochemical synthesis of cyclopropanes in EtOH.

2 Results and discussion

2.1 Synthesis of pyrazolines

We have also investigated the cycloaddition reaction of several pyridazine-3,6-diones 1a–d [18] with 2-diazopropane 2 [19]. The 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition of 2-diazopropane is, in each case, regiospecific. Unambiguous proofs for the obtained cycloadducts regiochemistry arised from their spectral data. However, regiochemical assignments of all adduct were deduced from their 13C-NMR spectra. Particularly the chemical shifts of C-6a (97.01–97.21 ppm) are in excellent agreement with those usually obtained when this quaternary carbon is attached to an oxygen atom (Table 1) [20].

Synthesis of pyrazolines via cycloaddition 1,3-dipolar.

| Entry | R | Yield (%) | 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ |

| 3a | Ph | 75 | 19.16 (CH3), 21.61 (CH3), 27.59 (CH3), 49.99 (C-3a), 93.47 (C-3), 97.21 (C-6a) |

| 3b | p-C6H4-CH3 | 80 | 19.12 (CH3), 21.13 (CH3), 21.51 (CH3), 27.55 (CH3), 49.96 (C-3a), 93.45 (C-3), 97.17 (C-6a). |

| 3c | p-C6H4-Cl | 65 | 19.17 (CH3), 21.52 (CH3), 27.34 (CH3), 50.02 (C-3a), 93.43 (C-3), 97.01 (C-6a) |

| 3d | Bn | 85 | 19.20 (CH3), 21.51 (CH3), 27.31 (CH3), 50.01 (C-3a), 50.72 (CH2Ar), 93.41 (C-3), 96.91 (C-6a) |

2.2 Formation of cyclopropanes

The photolysis of an ethereal solution of the pyrazolines 3a–d through pyrex with a high pressure mercury arc lamp at 0–5 °C led to exclusive formation of bicyclo-cyclopropanes 4a–d.

As shown in Table 2, pyrazoline derivatives 3a–d were sonicated in EtOH in an ultrasonic cleaning bath afforded gem-dimeylcyclopropanes 4a–d.

Synthesis of cyclopropanes under ultrasonication (25 °C, 30 kHz and 150 W).

| Entry | R | Reaction time (min) | Yield (%) | M.P. (°C) | ||

| Photolysis | Ultrasound | Photolysis | Ultrasound | |||

| 4a | Ph | 45 | 15 | 35 | 95 | 112 |

| 4b | p-C6H4-CH3 | 40 | 20 | 45 | 90 | 143 |

| 4c | p-C6H4-Cl | 35 | 15 | 40 | 85 | 127 |

| 4d | Bn | 45 | 20 | 50 | 75 | 129 |

The results were summarized in Table 2. Firstly, it can easily be seen that the irradiation of pyrazolines was carried out in good yield in ethanol under ultrasound irradiation (30 kHz, 150 W) within 15 min. The results show that the method to obtain bicyclo-cyclopropanes 4a–d under ultrasonic irradiation from pyrazoline derivatives 3a–d offers several significant advantages including faster reaction rates, higher purity, and higher yields. In comparison with conventional methods, the main advantage of ultrasound application is the significant decrease in the reaction times and milder experimental conditions. Thus, while the conventional method requires 35–45 min, ultrasonic irradiation affords the respective products in only 15–20 min (Table 2). These results support the idea that the energy provided by ultrasound significantly accelerates these reactions. The difference in yields and reaction times may be a consequence of the specific effects of ultrasound, in particular, cavitation, a physical process that creates, enlarges, and implodes gaseous and vaporous cavities in an irradiated liquid, thus enhancing the mass transfer [21] and allowing chemical reactions to occur. The creation of the so-called hot spots in the reaction mixture produces intense local temperatures and high pressures generated inside the cavitation bubble and at its interfaces when it collapses. In order to gauge the effect of different irradiation frequencies, the model reaction was performed under three different frequencies of 30, 40 and 50 kHz. The cyclopropane 4a yield for these frequencies was 95, 80 and 65% respectively. It seems that the lower frequency of ultrasound irradiation can improve the yield of cyclopropane derivatives.

Secondly, using the formation of 1,7,7-trimethyl-3-phenyl-3,4-diazabicyclo[4.1.0]heptane-2,5-dione 4a as a standard reaction, pyrazolines was sonicated under various sets of conditions in order to obtain optimal irradiation power conditions at a constant room temperature of 25 ± 1 °C and constant frequency 30 kHz (Table 3). By increasing the irradiation power from 100 to 200 W, the reaction time of 4a decreased from 30 to 10 min and the yield increased from 70 to 95%. The reaction time and yield of 4a did not change from 200 to 250 W, therefore, 200 W of ultrasonic irradiation was sufficient to push the reaction forward. The best yield for 4a was obtained by ultrasonic irradiation for 10 min at room temperature and 200 W.

Influence of the reaction intensity.

| Entry | R | Reaction time and yield | |||

| 100 W | 150 W | 200 W | 250 W | ||

| 4a | Ph | 30 min/70% | 15 min/95% | 10 min/95% | 10 min/95% |

| 4b | p-C6H4-CH3 | 30 min/65% | 20 min/90% | 15 min/90% | 15 min/90% |

| 4c | p-C6H4-Cl | 25 min/75% | 15 min/85% | 10 min/85% | 10 min/85% |

| 4d | Bn | 25 min/60% | 20 min/75% | 10 min/75% | 10 min/75% |

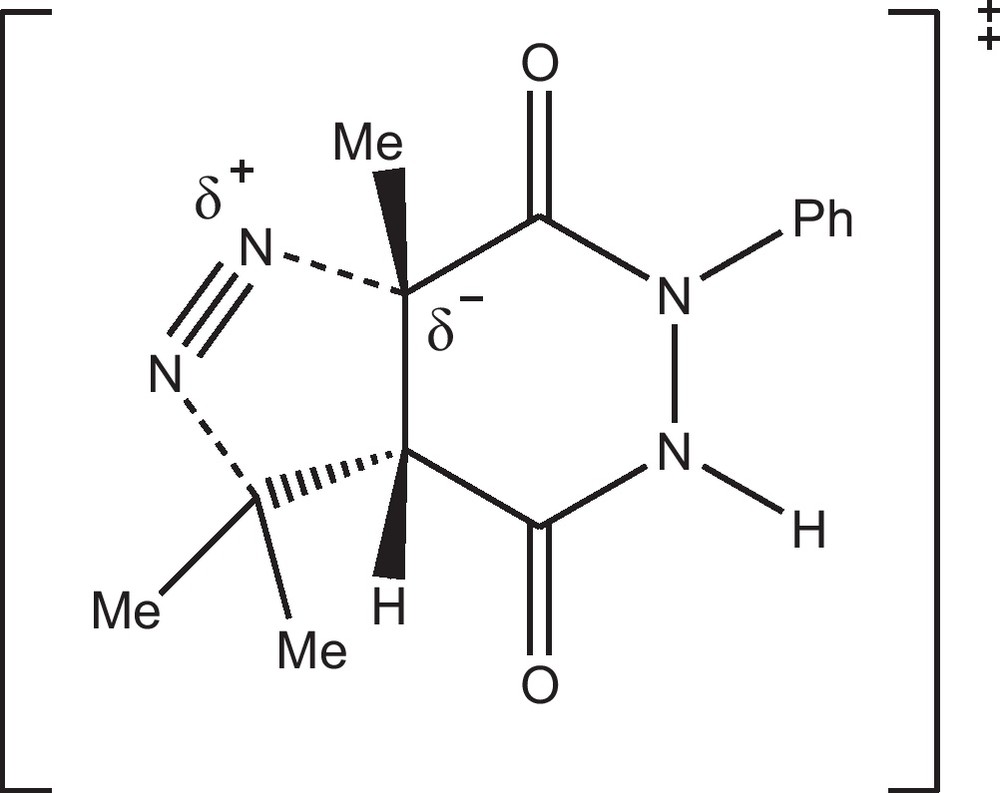

Under stationary irradiations, pyrazolines 3a–d afforded the corresponding cyclopropanes 4a–d with total stereospecificity [22]. The stereochemistry of this ultrasonic product was determined from a NOESY spectrum. The cis relation ship existing between the Me groups and the proton H-6 in compounds 4a could be deduced from observation of an NOE effect between H-6 and the methyl protons (Fig. 1).

NOE interaction between H-6 and the Me protons.

Whereas a diradical mechanistic pathway has been proposed by several groups [23] to explain the highly stereoselective evolution of pyrazolines under photolytic conditions, the course of the thermal decomposition of pyrazolines into cyclopropanes still remains controversial. Indeed, the hitherto reported stereochemical results from thermal decomposition of 1-pyrazolines are quite divergent and strongly dependent on the nature of the substituents at the ring. Concerted [24] or diradical [25] mechanisms have been postulated to explain the most usual pyrolytic processes proceeding without stereoselectivity. Bearing in mind the electron-withdrawing groups existing at the pyrazoline rings reported herein, our stereochemical results are consistent with the concerted thermal decomposition proposed by José et al. [26] of pyrazoline derivatives, which afford cyclopropanes by extrusion of nitrogen through a polar transition state, where the degree of bond breaking of the C(3a)-N bond is advanced over the bond breaking of the C(7)-N bond (Fig. 2).

Proposed transition states for the concerted nitrogen extrusion under ultrasonic conditions.

3 Conclusion

In this article, a new methodology to obtain functionalized bicycle-cyclopropanes under ultrasound irradiation has been used. The present procedure under ultrasound irradiation at room temperature significantly improved conventional methods, giving way to obvious advantages including simple operation, high yields, short reaction times and decreased toxicity.

4 Experimental

4.1 Apparatus and analysis

IR spectra were recorded on a Perkin-Elmer IR-197 spectrometer. NMR spectra were obtained on a Bruker AC 300 spectrometer operating at 300 MHz for 1H and at 75.64 MHz for 13C. Melting points were determined on a Buchi-510 capillary melting point apparatus. Coupling constants are given in Hz. Elemental analyses were performed on a PERKIN-ELMER 240B microanalyzer. Ultrasonication was performed in a GEX750-5 C ultrasonic processor equipped with a 3 mm wide and 140 mm long probe that was immersed directly into the reaction mixture. The operating frequency was 30–50 kHz and the output power was 0–750 W through manual adjustment. The temperature was controlled by a Buchi B-491 water bath at 25 ± 1 °C. All reagents were of commercial quality or purified by standard procedures.

4.2 General procedure for trapping of 2-diazopropane 2 with pyridazine-3,6-diones 1a–d

4.2.1 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition of 2-diazopropane with pyridazine-3,6-diones 1a–d

To a solution of pyridazine-3,6-diones 1a–d (1.0 mmol) in diethyl ether, cooled at 0 °C, was added portionwise 2.6 M ethereal solution of 2-diazopropane. The reaction was kept at the same temperature during 1 h. the solvent was removed in a vacuum without heating to give brown oil, which was subjected to column chromatography (SiO2; ethyl acetate/petroleum ether, 2:1) to afford compounds 3a–d.

3,3,7a-trimethyl-6-phenyl-3a,5,6,7a-tetrahydro-3H-pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyridazine-4,7-dione 3a

Anal. Calcd. For C14H16N4O2: C, 61.75; H, 5.92; N, 20.58%; Found: C, 62.00; H, 5.83; N, 20.50%; IR (KBr) νcm−1; 1640 (N = N); 1690 (C = O); 1700 (C = O); 1H-NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 1.28 (s, 6H, CH3), 1.75 (s, 3H, CH3), 2.51 (s, 1H, 3a-H), 6.27 (s, 1H, NH), 6.55–7.20 (m, 5H, Harom); 13C{1H}NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 19.16 (CH3), 21.61 (CH3), 27.59 (CH3), 49.99 (C-3a), 93.47 (C-3), 97.21 (C-6a), 113.45–143.60 (Carom), 169.67, 170.38 (C-4,C-7).

3,3,7a-trimethyl-6-(4-methylphenyl)-3a,5,6,7a-tetrahydro-3H-pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyridazine-4,7-dione 3b

Anal. Calcd. For C15H18N4O2: C, 62.92; H, 6.34; N, 19.57%; Found: C, 62.87; H, 6.24; N, 19.45%; IR (KBr) νcm−1; 1645 (N = N); 1695 (C = O); 1700 (C = O); 1H-NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 1.25 (s, 6H, CH3), 1.25 (s, 6H, CH3), 1.72 (s, 3H, CH3), 2.31 (s, 3H, CH3), 2.49 (s, 1H, 3a-H), 6.29 (s, 1H, NH), 6.85 and 7.08 (d, 4H, Harom, J = 8.1 Hz); 13C{1H}NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 19.12 (CH3), 21.13 (CH3), 21.51 (CH3), 27.55 (CH3), 49.96 (C-3a), 93.45 (C-3), 97.17 (C-6a), 128.9-136.9 (Carom), 169.63, 170.21 (C-4,C-7).

6-(4-chlorophenyl)-3,3,7a-trimethyl-3a,5,6,7a-tetrahydro-3H-pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyridazine-4,7-dione 3c

Anal. Calcd. For C14H15ClN4O2: C, 54.82; H, 4.93; N, 18.26%; Found: C, 54.73; H, 4.97; N, 18.38%; IR (KBr) νcm−1; 1640 (N = N); 1690 (C = O); 1705 (C = O); 1H-NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 1.22 (s, 6H, CH3), 1.64 (s, 3H, CH3), 2.47 (s, 1H, 3a-H), 6.34 (s, 1H, NH), 6.69 and 7.13 (d, 2H, Harom, J = 8.4 Hz); 13C{1H}NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 19.17 (CH3), 21.52 (CH3), 27.34 (CH3), 50.02 (C-3a), 93.43 (C-3), 97.01 (C-6a), 118.13–153.51 (Carom), 168.97, 171.08 (C-4,C-7).

6-benzyl-3,3,7a-trimethyl-3,3a,5,6-tetrahydro-7aH-pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyridazine-4,7-dione 3d

Anal. Calcd. For C15H18N4O2: C, 62.92; H, 6.34; N, 19.57%; Found: C, 62.98; H, 6.26; N, 19.61%; IR (KBr) νcm−1; 1640 (N = N); 1690 (C = O); 1700 (C = O); 1H-NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 1.21 (s, 6H, CH3), 1.62 (s, 3H, CH3), 2.48 (s, 1H, 3a-H), 5.12 (s, 2H, CH2Ar), 6.39 (s, 1H, NH), 7.26–7.35 (m, 5H, Harom); 13C{1H}NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 19.20 (CH3), 21.51 (CH3), 27.31 (CH3), 50.01 (C-3a), 50.72 (CH2Ar), 93.41 (C-3), 96.91 (C-6a), 117.12–141.51 (Carom), 167.99, 170.88 (C-4,C-7).

4.2.2 General procedure for the irradiation of the pyrazolines 3a–d

4.2.2.1 Photolysis irradiation of pyrazolines 3a–d

All irradiation were carried out using similar conditions. Irradiation of an ethereal solution of the pyrazolines through pyrex with a high pressure mercury arc lamp (Philips HPK 125 W) at 0–5 °C led to exclusive formation of gem-dimethylcyclopropanes. The derivative was dissolved in ether (pretreated by stirring with solid [NaCO3], filtering and flushing with argon) and irradiation at 5 °C for a total of 1 h or until the starting materiel was consumed (TLC). After this period, the solvent was removed in a vacuum without heating to give brown oil, which was subjected to rapid silica filtration. The recovered solid was subjected to a recrystallization treatment from dichloromethane/light petroleum.

4.2.2.2 Ultrasound irradiation of pyrazolines 3a–d

The appropriate pyrazolines 3a–d (1 mmol) was dissolved in ethanol (5 mL). The reaction was irradiated in the water bath of the ultrasonic cleaner at 25 °C. The specific period employed is listed in Table 1. The solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure. The further purification was accomplished by column chromatography on silica (200–300 mesh, eluted with petroleum ether or a mixture of petroleum ether and diethyl ether).

1,7,7-trimethyl-3-phenyl-3,4-diazabicyclo[4.1.0]heptane-2,5-dione 4a

Anal. Calcd. For C14H16N2O2: C, 68.83; H, 6.60; N, 11.47%; Found: C, 68.80; H, 6.55; N, 11.41%; IR (KBr) νcm−1; 1700 (C = O); 1710 (C = O); 1H-NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 1.24 (s, 3H, CH3), 1.28 (s, 3H, CH3), 1.55 (s, 3H, CH3), 2.16 (s, 1H, 6-H), 6.76–7.26 (m, 6H, Harom,NH); 13C{1H}NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 10.31 (CH3), 17.31 (CH3), 22.91 (CH3), 34.96 (C-7), 35.51 (C-6), 38.05 (C-1), 113.78–145.63 (Carom), 172.48, 175.41 (C-2, C-5).

1,7,7-trimethyl-3-(4-methylphenyl)-3,4-diazabicyclo[4.1.0]heptane-2,5-dione 4b

Anal. Calcd. For C15H18N2O2: C, 69.74; H, 7.02; N, 10.84%; Found: C, 69.69; H, 7.05; N, 10.76%; IR (KBr) νcm−1; 1710 (C = O); 1705 (C = O); 1H-NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 1.22 (s, 3H, CH3), 1.27 (s, 3H, CH3), 1.59 (s, 3H, CH3), 2.14 (s, 1H, 6-H), 2.30 (s, 3H, CH3), 6.39 (s, 1H, NH), 6.85 and 7.08 (d, 4H, Harom, J = 8.1 Hz); 13C{1H}NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 10.31 (CH3), 17.31 (CH3), 21.13 (CH3), 22.87 (CH3), 34.93 (C-7), 35.49 (C-6), 38.13 (C-1), 128.9–136.9 (Carom), 171.88, 174.62 (C-2, C-5).

3-(4-chlorophenyl)-1,7,7-trimethyl-3,4-diazabicyclo[4.1.0]heptane-2,5-dione 4c

Anal. Calcd. For C14H15ClN2O2: C, 60.33; H, 5.42; N, 10.05%; Found: C, 60.41; H, 5.39; N, 9.98%; IR (KBr) νcm−1; 1690 (C = O); 1700 (C = O); 1H-NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 1.25 (s, 3H, CH3), 1.29 (s, 3H, CH3), 1.55 (s, 3H, CH3), 2.19 (s, 1H, 6-H), 6.57 (s, 1H, NH), 6.71 and 7.19 (d, 2H, Harom, J = 8.4 Hz) 13C{1H}NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 11.01 (CH3), 18.07 (CH3), 22.90 (CH3), 34.89 (C-7), 35.66 (C-6), 38.01 (C-1), 117.21–152.43 (Carom), 171.36, 173.22 (C-2, C-5).

3-benzyl-1,7,7-trimethyl-3,4-diaza-bicyclo[4.1.0]heptane-2,5-dione 4d

Anal. Calcd. For C15H18N2O2: C, 69.74; H, 7.02; N, 10.84%; Found: C, 69.61; H, 7.00; N, 10.73%; IR (KBr) νcm−1; 1690 (C = O), 1705 (C = O); 1H-NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 1.25 (s, 3H, CH3), 1.28 (s, 3H, CH3), 1.52 (s, 3H, CH3), 2.17 (s, 1H, 6-H), 5.11 (s, 2H, CH2Ar), 6.76 (s, 1H, NH), 7.24–7.31 (m, 5H, Harom); 13C{1H}NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 11.09 (CH3), 18.06 (CH3), 22.87 (CH3), 34.83 (C-7), 35.56 (C-6), 38.04 (C-1), 50.62 (CH2Ar), 116.19–142.41 (Carom), 172.01, 172.29 (C-2, C-5).