1 Introduction

All industries are now facing severe environmental constraints imposed by regulations concerning volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and occupational diseases (European directives 2010/75/EC, 2001/81/EC, 2004/73/EC, REACH, Clean air act, etc.). Progressively they are looking for more sustainable solutions to limit risks and hazards for health and environment. It is also an opportunity for industry to set themselves apart from the competition and to respond to the growing of consumer demands for safer and healthier products. Solvents are the most affected among all commodity chemicals by these regulations [1,2] because of their large-scale use in a significant number of industrial applications. Currently, there are two classes of solvents that are being used in industrial practice: petrochemical-based solvents and solvents from agricultural resources, the so-called “biobased solvents”. Although solvents from oil resources predominate in industrial applications, the chemical industry is willing to implement more sustainable solutions. It concerns especially industries devoted to produce plant-based products in food, cosmetics, fragrances, and pharmaceutical ingredients and where solvent extraction and purification techniques are at the heart of the manufacturing process that need a huge consumption of tailor-made solvents. In particular, n-hexane has been used for decades in extraction of aromas in food, cosmetics, fragrances, and pharmaceutical industries [3]. This solvent offers suitable performances because of its low boiling temperature and low polarity. Although many studies have demonstrated the toxic and hazardous effects [4–6], hexane is still the preferred solvent for the extraction of aromatic compounds despite its top-ranking position in the list of the hazardous solvents.

Previous studies have dealt with the n-hexane substitution for aroma extraction [6,7], but the screening of nonpolar and polar alternative solvents was carried out using experience-based approach. The main criteria for the solvent screening are based on the calculation of the Hansen solubility parameters (HSPs) allowing the evaluation of the affinity between the solvent and each target molecule contained in agricultural resources. Recently, Sixt et al. [8] highlighted the required coupling of the solvent screening methodology with the process design including all typical unit operations in the manufacturing of natural products. Rigorous modeling of solid–liquid extraction, purification by liquid–liquid extraction, distillation, and crystallization must be related to the physicochemical properties representing the affinity between solvent and solutes. The authors used conductor-like screening model for realistic solvents (COSMO-RS) [9] as a predictive model for computing the solubility of the target molecules in every solvent. However, the initial selection of the solvent candidates was again carried out by an experience-based approach. Because of the heterogeneous composition of the extract from bioresources, the entrainer selection based on the trial and error method is limited and may have missed good candidates. Instead, reverse engineering approaches, like computer-aided molecular design (CAMD), are fit to handle several properties simultaneously and to propose very diverse molecular structures matching the target values of these properties.

Nowadays, CAMD approach has become a standard tool for finding single molecular structures matching target physicochemical properties selected a priori by the end-user [10]. CAMD is based on a reverse engineering approach where a complete set of physicochemical properties is first established, and then the building of molecular structures is guided by the closest matching to these properties. The computer-aided product design (CAPD) tool follows the general methodology of a CAMD tool but considering the mixture as another feasible solution for which the composition of each component is also determined. The increasing application of a CAPD tool for replacing substances highly restricted by registration, evaluation, authorization and restriction of chemicals (REACH) regulations has provided some successful results mainly in designing alternative solvents for zero CFC refrigerant and biobased polymers [11]. The substitution of hazardous solvents prevails in manufacturing processes such as perfume, cosmetics, pharmaceutical, food ingredient, nutraceutical, biofuel, or fine chemical industries because solvents are widely used in huge amounts for organic synthesis, extraction, purification, and formulation processes. Recent trends in natural product chemistry have essentially focused on finding new technological solutions for reducing the use of solvents or substituting petroleum-based solvents [12–15]. We have recently developed the IBSS CAMD tool (InBioSynSolv) as a new CAPD computational tool to generate virtual molecular structures of promising solvents for a wide application spectrum in process engineering [16]. IBSS CAMD tool optimizes simultaneously the molecular structure of the component as maximizing a global performance function defined as weighted sum of the individual performance of each target property. The main advantage of IBSS CAMD over the well-known computational tool Virtual Product–Process Laboratory [17] lies on the possibility of the design of biobased solvents by fixing a chemical synthon corresponding to a fragment of an existing molecule in nature [18]. Addition and modification of free connections with external chemical groups are carried out during the optimization method of maximizing the global performance function. As a solution, the IBSS CAMD tool provides a list of best candidates including existing or new molecules. If nonadequate solution is found by designing pure components, the problem of substituting a molecule may result in proposing mixtures where synergetic nonideal thermodynamic behavior may improve properties in a nonlinear manner.

In this article, we have taken the advantages of a CAPD approach to design new alternative solvents as part of n-hexane substitution to extract a group of typical aroma molecules from agricultural resources that are largely used in perfumery. First, the context of the optimization problem formulation by using the IBSS CAMD tool is described. Second, a set of target physicochemical property values matching the specifications of this project is defined allowing the evaluation of the global performance function for each solvent candidate. To build molecular structures, a set of chemical fragments was selected based on the better promising green solvents reported [19] along with the incorporation of other chemical functional groups for which the fluid global performance was expected to be sensitive. Then the CAPD search was run with the help of the IBSS in-house genetic algorithm optimization technique to build new molecular structures. For each molecule, group contribution models in the IBSS property package library were used to predict the target physicochemical properties and further compute the global performance index. This led to a first list of promising candidates as pure fluids that can be further used as a niche for generating azeotropic mixtures to improve the global performance of the pure component candidates.

2 Problem formulation of a CAPD approach for the design of alternative solvents

The systematic methodology uses the reverse design approach [15,16,20] where the targets of the design problem are defined a priori and molecular structures that match the specifications are built in silico. In pure component design, thousands of candidates are systematically generated and screened. The tailor-made pure component design problem is multiobjective because several properties must be satisfied at the same time. However, the multiobjective optimization problem is converted into a single objective, aiming at maximizing a global performance index, GloPerf objective function (OF) subject to k equality and l inequality constraints on each target property P. The mathematical formulation follows:

| (1) |

The optimization variables are the molecular graph structure

The global performance,

| (2) |

Each individual performance

| (3) |

The tolerance parameter tol (mean tolerance) is the deviation from target giving a value of the

The selected search algorithm for a pure component design is the genetic algorithm with elitism policy as earlier proposed by Venkatasubramanian et al. [27] in CAMD. The user defines inherent parameters such as the population size, the elitism value, and all operator probabilities. The initial population of individuals is generated randomly within the predefined constraints on the optimization variables related to

3 Methodology for designing alternative solvents by CAPD

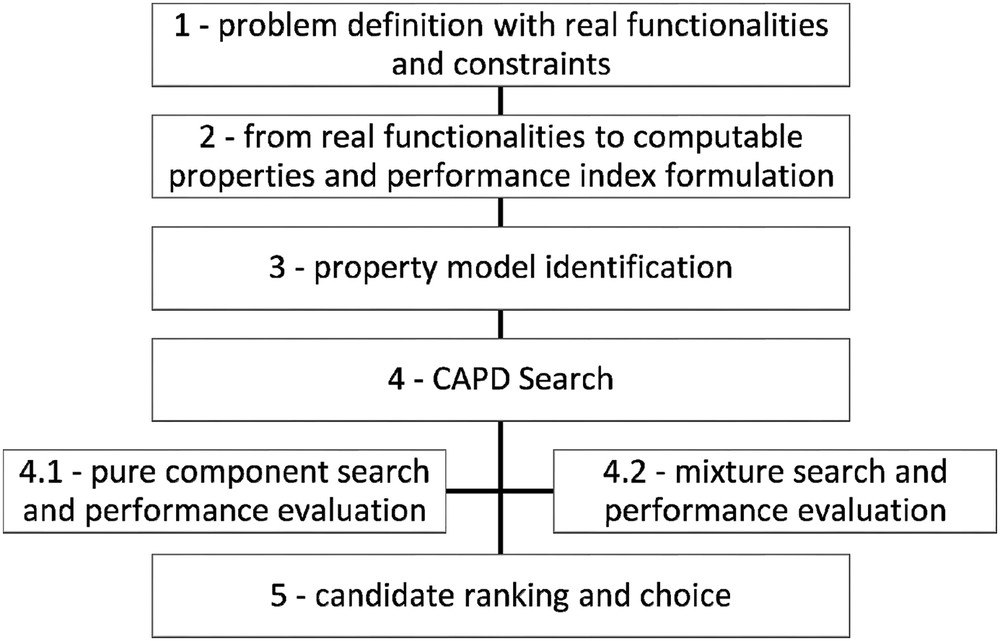

The systematic methodology consists of five steps and is summarized in Fig. 1.

- - Step 1: Definition of the design problem

Systematic methodology based on reverse engineering and CAPD to design alternative solvents.

The specifications of alternative solvents are primarily determined by identifying the key product functionalities of the current solvents to be substituted, for example, n-hexane or other conventional solvents applied for the extraction of aromatic compounds from agroresources.

- - Step 2: Conversion of the specifications into physicochemical properties together with their target values

A knowledge-based analysis is commonly used to transform the product specifications into required physicochemical properties. For instance, volatility is related to a low boiling temperature, liquid state means a low melting point along with high critical pressure and temperature, a safe solvent implicates a flash point (FP) higher than 333.15 K, and so forth. Next, taking into account the values of the physicochemical properties of existing solvents, we can define the target values and their feasible range for each property. For example, a reasonable boiling point (BP) may lie between 333.15 and 373.15 K. At that time, the type of each individual performance

- - Step 3: Property model identification for pure component and mixture

For a pure component, the user retrieves the required property models from the IBSS property package library. They should be able to compute properties for a wide diversity of chemical structures by applying quantitative structure–activity relationship models (QSAR)/quantitative structure-property relationship (QSPR) or group contribution models. In this study, only group contribution methods were used and they were selected taking into account their predicting accuracy based on the quality of the suitable databases that have been used to derive them [25]. In the case of the mixtures, nonlinear behavior of properties is expected over the composition range. Nevertheless, for a fast CAPD search, linear mixing rules of pure component properties are preferred at first. Their prediction accuracy is systematically checked afterward with experimental databases or by rigorous calculation of phase equilibria with thermodynamic models for computing BP and FP from vapor–liquid equilibrium (VLE), melting point from solid–liquid equilibrium, and liquid–liquid equilibrium (LLE) at a given or into a range of composition values.

- - Step 4: Generation and screening of alternative solvents

- • Step 4.1: Design of alternative solvents as pure components

- ✓ Step 4.1.1: Molecular design in silico by using IBSS CAMD tool.

- • Step 4.1: Design of alternative solvents as pure components

Molecular structures of pure components are built as an assembly of basic and complex chemical blocks, which are often similar to some first, second, and third order groups in contribution methods. Hence, their presence in the molecular structure allows cataloging the components into chemical families such as saturated and unsaturated hydrocarbons, alcohols, ethers, esters, ketones, aldehydes, amines, aromatics, polyfunctional molecules, and so forth. The basic chemical groups are selected from a chemical fragment database implemented in the IBSS CAMD tool. New fragments can be readily added to this tool as they are described as connectivity matrices [16]. Some fragments can be imposed in the searched structures, as some users may want to explore the potentiality of existing in-house molecules. Building of molecules is carried out by the random assembling of simple and complex chemical groups and following chemical feasibility rules based on the octet rule. The solution of the optimization problem Eq. 1 by genetic algorithm provides the final list of the best candidates along with the respective value of the OF

- ✓ Step 4.1.2: Ranking of pure component candidates

Step 4.1.1 provides the final list of the best pure candidates. It is recommended at that point to update the value of

- • Step 4.2: Design of alternative solvents as binary mixtures

- ✓ Step 4.2.1: Preliminary formulation of suitable binary mixtures from pure components

The pair of pure components is selected following the knowledge-based approach. Typically the most promising pure components from step 4.1 are selected and the properties penalizing the most their performance are identified. Nonideal behavior in a mixture may result in the synergetic effect that might improve the pure component deficient property values when set in a mixture. For example, the formation of binary azeotropic mixture can lower the fluid boiling temperature and the FP as well [28]. It is promoted by close boiling components and the presence of different chemical groups in the molecule. Prausnitz et al. [29] summarized several principles that can be used as a guide for diagnosing the possible formation of a binary azeotropic mixture. These principles are based either on the creation of hydrogen bonding interactions between dissimilar families of compounds or on the disruption of the hydrogen bonds promoting the formation of the minimum boiling azeotropic mixtures.

- ✓ Step 4.2.2: Prediction of physicochemical target properties

For a quick screening of mixture properties, models based on linear mixing rules are implemented in the IBSS CAMD tool. They are further refined with nonlinear models that are more computer intensive because they require for each composition to solve a flash calculation as they are based on thermodynamic models of the phase equilibrium. The assumption of an ideal gas phase is kept and the liquid phase nonideality is assessed by using an activity coefficient model [30]. Computation of the activity coefficient γ was performed using group contribution methods like original UNIFAC and modified UNIFAC. All these models are available in the commercial thermodynamic calculator Simulis Thermodynamics [31].

In this study, thermodynamic VLE-based nonlinear models are used for computing the boiling temperature and the FP, because they are among the key properties for a safe extraction process, solvent recovery, and recycling. The affinity between the binary mixture and the target aromatic compounds is determined by the calculation of the distance between the solvent mixture and the center of Hansen solubility sphere of the aromatic compounds (Ra in Eq. 4). For that, Hansen parameters for binary mixtures are computed as a linear model considering the volume fraction [32].

- ✓ Step 4.2.3: Ranking of binary mixture candidates

Individual performance

- - Step 5: Ranking of all promising candidates

The final list includes the best candidates for both pure components and binary mixtures. Performance

4 Solvent design for extracting aroma molecules from plant materials

4.1 Selection of target aroma molecules

Natural extracts for use in aromas and perfumes are complex substances also called “complex natural substances” and they are present in plants in small quantities. Logically, if a substance is able to have aroma properties, it must have a moderate molecular weight and a high vapor pressure. On the other hand, there is no need for it to have any particular functional groups or to be chemically reactive. Industrial practice for separating these components from plants mostly involves extraction methods mainly using a pure volatile solvent. This extraction technique was frequently carried out in the first half of the 20th century with petroleum ether (mixture of pentane isomers), benzene, and nowadays solvents such as hexane, cyclohexane, methylene chloride, ethyl acetate, isopropanol, acetone, methanol, or ethanol are conventionally used and then separated by evaporation under vacuum.

Extracts from plants are complex multicomponent mixtures mainly constituted of monoterpenes, sesquiterpenes, and their oxygenated derivatives, together with aliphatic aldehydes, alcohols, and esters. Table 1 displays a list of aromatic molecules mostly contained in plant extracts. The list includes the most current aroma substances in the extracts from roses, jasmines, lavenders, and common gardenias among others [33]. Boiling temperatures were reported in the Handbook of Chemistry and Physics [34], whereas the flash temperatures were found in the Web site www.ChemSpider.com [35]. HSPs (δD, δP, and δH) were taken from published values in the literature [36] allowing the computing of the Hildebrand solubility parameter

Physicochemical properties of the components in the artificial mixture.

| No. | Molecule | BPa (K) | BPb (K) | FPa,c (K) | FPb (K) | ||||

| 1 | α-Pinene | 429.45 | 429.5 | 306.15 | 307.6 301.4 | 17b 16.4d | 1.3 1.1 | 2 2.2 | 16.5 |

| 2 | Limonene | 447.15 | 451.9 | 321.15 | 318.1 311.4 | 16.7b 17.2d | 2.2 1.8 | 4.9 4.3 | 17.8 |

| 3 | α-Terpinene | 447.15 | 436.3 | 323.15 | 313.6 305.1 | 16.4b | 0.7 | 2.7 | 16.1 |

| 4 | Terpinolene | 460.15 | 447.5 | 337.15 | 308.2 | 16.9b | 1.8 | 4.8 | 17.7 |

| 5 | Myrcene | 444.15 | 442.9 | 317.15 | 271.1 317.5 | 15.8b | 2 | 4.2 | 16.5 |

| 6 | Anethole | 505.15 | 505.6 | 369.15 | 325.5 375.2 | 19.0d 18.6b | 4.3 5.2 | 8.7 6.5 | 21.3 |

| 7 | Eucalyptol | 449.65 | 458.9 | 322.15 | 304.5 326.9 | 16.7d 17b | 4.6 4 | 3.4 3.3 | 17.7 |

| 8 | Jasmone | 531.15 | 513.6 | 380.15 | 379.2 | 17.1b | 5.5 | 5.9 | 18.9 |

| 9 | Fenchone | 468.15 | 472.6 | 325.15 | 353.2 344.3 | 17.2b | 8.8 | 4.2 | 19.8 |

| 10 | Camphor | 477.15 | 480.6 | 337.15 | 338.7 348 | 17.8d 17.2b | 9.4 8.8 | 4.7 4.2 | 20.7 |

| 11 | Geraniol | 502.15 | 507.2 | 374.15 | 350.7 382.1 | 16.3b | 4.1 | 11.3 | 20.3 |

| 12 | Linalool | 471.65 | 486.8 | 349.15 | 337.9 365.5 | 16.2b | 3.7d | 10.8d | 19.8 |

| 13 | Benzyl acetate | 488.15 | 484.3 | 368.15 | 349.8 356.4 | 18.3d 18.3b | 5.7 5.2 | 6.0 6.1 | 20.1 |

| 14 | α-Terpinyl acetate | 493.15 | 508.9 | 372.15a | 346.3 363.6 | 16.3b | 3.6d | 4.8d | 17.4 |

| 15 | Linalyl acetate | 494.15 | 505.7 | 358.15 | 321.3 363.3 | 16.0b | 4.0d | 9.9d | 19.2 |

Calculable properties and models for the computation of alternative solvent performance.

| Functionality | Calculable property | Target value | Parameters (Eq. 2) | Pure component model/Gaussian function (Eq. 3) |

| Solvency power | 16< | MB2010 [25] | ||

| val = 0.8 | ||||

| tol = 0.6 | ||||

| val′ = 0.1 | ||||

| tol′ = 0.2 | ||||

| 2< | MB2010 [25] | |||

| val = 0.7 | ||||

| tol = 0.5 | ||||

| val′ = 0.9 | ||||

| tol′ = 0.7 | ||||

| 4< | MB2010 [25] | |||

| val = 0.6 | ||||

| tol = 2 | ||||

| val′ = 0.6 | ||||

| tol′ = 1 | ||||

| Hildebrand solubility | 18< | |||

| val = 0.9 | ||||

| tol = 0.6 | ||||

| HSP distance Eq. 4 | Ra < 3 | MB2010 [25] | ||

| val = 0.9 | ||||

| tol = 0.8 | ||||

| Medium boiler | BP (K) | 323.15 < BP < 393.15 | Hukkerikar et al. [24] Marrero and Gani [21] | |

| val = 0.7 | ||||

| tol = 5 | ||||

| Low flammability | FP (K) | FP > 296.15 | Cartoire et al. [23] Hukkerikar et al. [24] | |

| val = 0.6 | ||||

| tol = 8 | ||||

| Low water soluble | Log(Kw) Kw (mg/L) | <4 | Marrero and Gani [22] | |

| val = 0.85 | ||||

| tol = 0.5 |

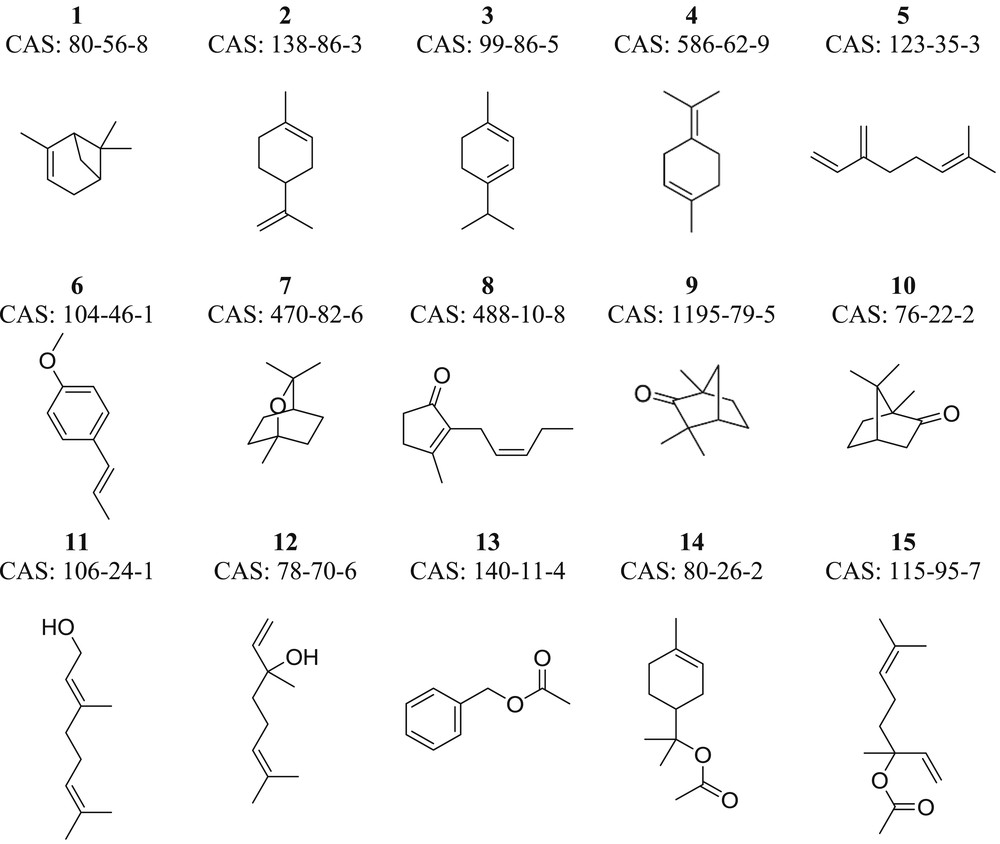

Fig. 2 displays the molecular structure of each molecule reported in Table 1. Each chemical structure is converted into its simplified molecular input line entry specification (SMILES) notation that can be further fragmented into the corresponding first, second, and third group classes according to the respective group contribution method. Hence, physicochemical property P can be computed by an IBSS CAMD tool allowing the evaluation of the individual performance

Chemical structures of target aroma molecules.

4.2 Selection of relevant physicochemical properties

The relevant properties P that will drive solvent selection have to be defined. In the case study of the present work, the selection of an alternative solvent is first based upon its ability to solubilize the group of molecules reported in Table 1, which display a variable polarity going from low polar components as α-pinene to polar components as linalool. The solubilizing capacity of the solvent is evaluated by the Ra, that is, the distance of a solvent from the center of the Hansen solubility sphere of the aroma molecule, given by Eq. 4:

| (4) |

The ratio between the distance Ra and the radius R of the solubility sphere of each aroma molecule is called the relative energy difference (RED = Ra/R) and allows a fast screening of alternative solvents in the design phase. RED is calculated from the HSPs that are based on the concept that the total cohesive energy density is approximated by the sum of the energy densities required to overcome atomic dispersion forces (

Table 2 displays the relationship between real functionalities expected for the alternative solvent and the associated calculable physicochemical properties. The individual performance

Good candidates have a BP between 333.15 and 373.15 K and

As the main aim of this study was to find a middle boiler solvent with a BP lower than 373.5 K, a solvent having an FP between 283.15 and 296.15 K will be considered as an appropriate candidate because it will largely improve the safety of the extraction process with the existing solvents. We set that

5 Results of alternative solvents as pure components

5.1 Results of alternative solvents suggested in the literature

Previous studies have aimed at replacing n-hexane for the extraction of volatile aroma compounds using edible oils [36] and for the extraction of main components in blackcurrant buds [7]. Table 3 displays the global performance index for the main alternative solvents studied in these articles and having a boiling temperature lower than the target value of 393.15 K for substituting n-hexane and their main physicochemical properties.

Target properties and global performance of reported solvents (property units as in Table 1).

| Solvent | BPa | FPa | log(Ws)a | Ra | |||||

| n-Hexane | 348.7 | 253.8 | 3.03 | 15.2 | 0.8 | 2 | 8.3 | 14.9 | 0.2504 |

| 341.8b | 250.15b | −5.01b | 14.9c | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Ethyl acetate | 350.21 | 264.1 | 4.36 | 15.6 | 6 | 7.2 | 3.3 | 18.4 | 0.7257 |

| 346.6b | 270.15b | −3.10b | 15.8c | 5.3 | 7.2 | ||||

| MeTHF | 353.15 | 260.6 | 4.02 | 16.8 | 5 | 4 | 1.8 | 18.14 | 0.6808 |

| 351.1b | 262.15b | −0.84b | 16.9c | 5 | 4.3 | ||||

| Isopropanol | 355.4 | 265.9 | 5.27 | 15.1 | 8 | 14.3 | 11.4 | 23.58 | 0.3550 |

| 329.6b | 285.15b | >7b | 15.8c | 6.1 | 16.4 | ||||

| Dimethyl carbonate | 363.15 | 262.2 | 4.89 | 15.2 | 8 | 6.7 | 4.8 | 18.7 | 0.7367 |

| 342.5b | 289.15b | −0.9b | 15.5c | 3.9 | 9.7 | ||||

| Butanol | 390.81 | 305.1 | 4.31 | 15.6 | 6.6 | 15.8 | 10.4 | 22.92 | 0.3897 |

| 389.2b | 308.15b | −1.14b | 16c | 5.7 | 15.8 | ||||

| Ethylal | 361.1 | 268.1 | 4.97 | 15.3 | 5.7 | 4.9 | 4.4 | 17.12 | 0.6185 |

| 361.15b | 266.15b | −1.2d | 14.87d | 4.67 | 6.95 |

d-Limonene has also been proposed as an alternative solvent for the extraction of aroma compounds from orange peels (Citrus sinensis L.), carrots (Daucus carota), and caraway seeds (Carum nigrum) providing better results than hexane [37]. However, the main drawback of d-limonene is the high boiling temperature imposing a high vacuum condition for its recovery by evaporation, which is why the boiling temperature has been considered among the key properties to be matched in the solvent screening method (see Table 2).

As it can be observed in Table 3, predicted values are in good agreement with experimental results. The higher deviations in BPs and FPs were obtained for isopropanol and dimethyl carbonate (DMC) as it is usual for polar small molecules predicted by group contribution methods [21,22,24]. Hence, the value of the OF global performance displayed in Table 3

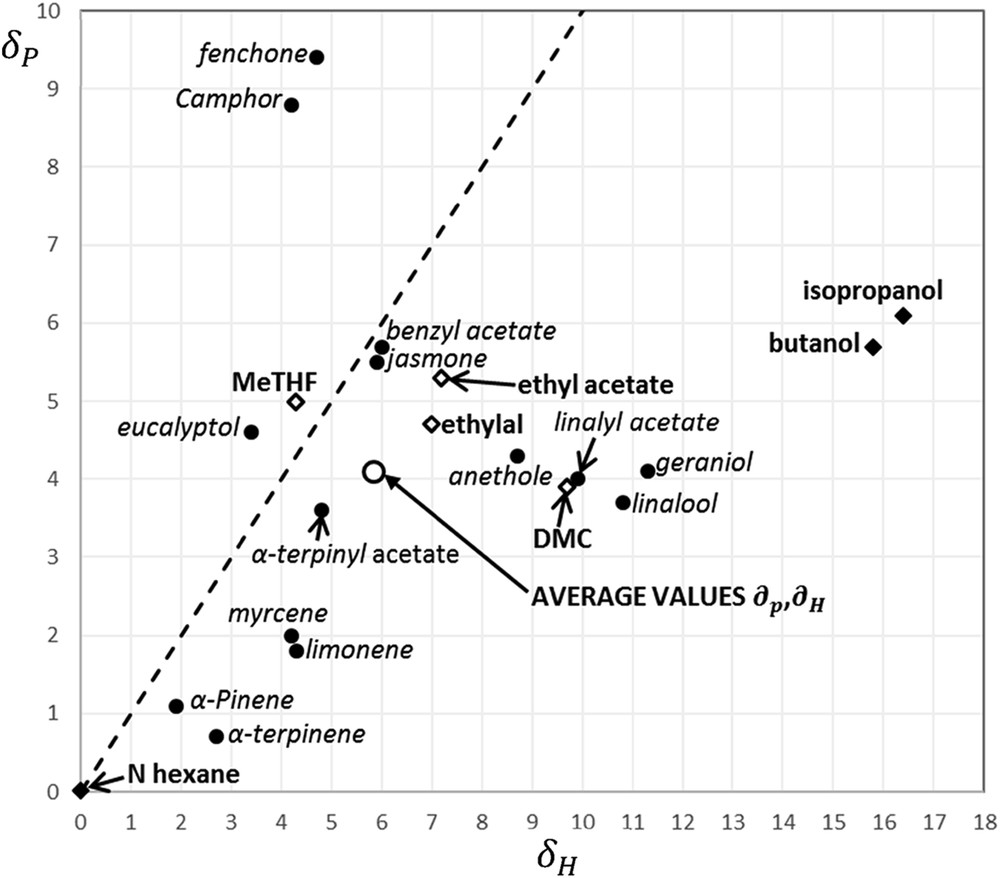

As it can be observed in Fig. 3, most of the aroma molecules constituting our natural extract mixture are located below the discontinuous line (

Hansen parameters for

5.2 Results of new alternative solvents using IBSS CAMD tool

The molecular structure of the new solvent is built from the definition of the list of chemical groups and they are combined in a free manner limited to a maximum of six chemical groups. Table 4 shows the selected chemical groups for generating the molecular structure of the solvent candidates taking into account the number of possible connections for each fragment (N1, one connection; N4, four connections) and the nature of the connection (N1(1), one simple bound; N2(1,2), one simple bound and one double bound). Cyclic molecules can be also built from the list of the fragment having a maximum size of six for the cyclic part and 10 chemical groups for the overall molecule. The following parameters of the genetic algorithm were used for optimizing the OF

Chemical groups for building alternative solvents using IBSS CAMD tool.

| N1(1) | N2(1,1) | N3(1,1,1) | N4(1,1,1,1) | ||

| N1(2) | N1(3) | N2(1,2) | N2(1,3) | N2(2,2) | N3(1,1,2) |

As a result, IBSS CAMD provided a text file where the final population of 500 generated chemical structures is ranked in the decreasing values of the function

List of the best solvent candidates provided by an IBSS CAMD tool (unity of property as Table 1).

| No. | Candidates | BP | FP | Log(Ws) | Ra | |||||

| 1 | Allyl acetate | 372.9 | 280.1 | 4.1 | 15.7 | 5.6 | 6.7 | 3.1 | 17.9 | 0.778 |

| 2 | sec-Butyl formate | 370.4 | 277.5 | 3.9 | 15.8 | 4.9 | 6.9 | 2.7 | 17.9 | 0.764 |

| 3 | Methyl butanoate | 372.7 | 277.6 | 4.1 | 15.7 | 4.8 | 6.6 | 2.8 | 17.6 | 0.759 |

| 4 | Ethyl propanoate | 372.7 | 277.6 | 4.1 | 15.6 | 5.9 | 6.6 | 3.4 | 17.9 | 0.756 |

| 5 | 2-Methyltetrahydrofuran | 350.5 | 260.5 | 4.0 | 16.8 | 5.0 | 4.0 | 2.1 | 17.9 | 0.750 |

| 6 | 1,3-Cyclohexadiene | 350.7 | 254.5 | 3.9 | 17.2 | 1.9 | 4.6 | 2.6 | 17.9 | 0.747 |

| 7 | 1-Methylvinyl cyclopropane | 329.7 | 233.7 | 3.4 | 16.5 | 3.3 | 5.6 | 1.3 | 17.7 | 0.747 |

| 8 | Tetrahydropyran | 365.1 | 270.0 | 4.3 | 17.1 | 3.5 | 4.1 | 1.9 | 17.9 | 0.746 |

| 9 | sec-Butylamine | 332.8 | 249.4 | 3.4 | 15.7 | 4.6 | 7.4 | 3.0 | 17.9 | 0.746 |

| 10 | Methyl cyclopropanecarboxylate | 370.0 | 276.9 | 4.5 | 17.1 | 6.1 | 6.9 | 2.2 | 19.4 | 0.745 |

| 11 | Isopropenyl acetate | 372.9 | 272.8 | 4.0 | 15.6 | 5.2 | 6.6 | 3.1 | 17.7 | 0.744 |

| 12 | 1,2-Epoxybutane | 336.9 | 256.5 | 4.4 | 16.3 | 6.0 | 4.8 | 2.6 | 18.0 | 0.741 |

| 13 | 3,3-Dimethyloxetane | 331.4 | 242.6 | 4.4 | 16.5 | 5.0 | 4.4 | 2.0 | 17.7 | 0.741 |

| 14 | 2,5-Dimethylfuran | 368.9 | 265.6 | 4.4 | 16.9 | 5.2 | 7.3 | 1.8 | 19.1 | 0.741 |

| 15 | Tetrahydrofuran | 324.3 | 243.3 | 4.4 | 16.9 | 4.2 | 4.1 | 1.8 | 17.8 | 0.741 |

| 16 | Propyleneimine | 318.7 | 247.2 | 4.2 | 17.3 | 6.1 | 6.4 | 2.1 | 19.4 | 0.740 |

| 17 | 2-Methyl-1,3-dioxolane | 359.9 | 273.4 | 4.3 | 17.1 | 6.5 | 6.3 | 2.4 | 19.3 | 0.739 |

| 18 | Methyl methacrylate | 372.5 | 268.7 | 4.2 | 15.6 | 6.0 | 6.5 | 3.4 | 17.9 | 0.739 |

| 19 | Vinyl propanoate | 372.5 | 268.7 | 4.2 | 15.6 | 6.0 | 6.5 | 3.4 | 17.9 | 0.739 |

| 20 | 4-Methyl-1,3-dioxolane | 359.9 | 273.4 | 4.3 | 17.4 | 6.0 | 6.7 | 2.2 | 19.5 | 0.738 |

| 21 | 3-Methoxy-1-propyne | 322.6 | 239.9 | 4.4 | 15.7 | 5.9 | 6.7 | 3.3 | 18.0 | 0.738 |

| 22 | 1-Methoxy-1,3-butadiene | 362.8 | 264.2 | 3.6 | 15.5 | 5.1 | 6.6 | 3.2 | 17.6 | 0.734 |

| 23 | Isobutyl formate | 371.8 | 279.0 | 3.9 | 15.2 | 5.1 | 7.0 | 3.9 | 17.4 | 0.729 |

| 24 | 3-(Dimethylamino)-1-propyne | 344.7 | 258.7 | 4.2 | 16 | 3.2 | 5.6 | 2.2 | 17.2 | 0.729 |

| 25 | 2,5-Dihydro-1H-pyrrole | 372.1 | 282.5 | 4.3 | 17.9 | 5.0 | 8.5 | 3.3 | 20.4 | 0.728 |

| 26 | 1,5-Hexadiyne | 357.4 | 259.6 | 2.8 | 16.2 | 3.0 | 4.7 | 2.3 | 17.1 | 0.725 |

| 27 | 2-Methylfuran | 345.0 | 253.2 | 4.4 | 17.3 | 5.7 | 7.6 | 2.4 | 19.7 | 0.725 |

| 28 | Isopropyl acetate | 354.8 | 266.4 | 4.1 | 15.4 | 4.8 | 6.6 | 3.3 | 17.4 | 0.722 |

| 29 | Methyl propanoate | 340.3 | 255.3 | 4.4 | 15.6 | 6.0 | 7.2 | 3.6 | 18.2 | 0.722 |

| 30 | Methyl isobutanoate | 352.8 | 265.6 | 4.2 | 15.4 | 4.8 | 6.6 | 3.3 | 17.4 | 0.721 |

| 31 | N-Methyl-2-propyn-1-amine | 347.0 | 262.7 | 4.7 | 15.7 | 4.9 | 7.8 | 3.3 | 18.2 | 0.718 |

| 32 | Diallyl ether | 359.9 | 261.0 | 3.9 | 15.4 | 4.8 | 6.2 | 3.3 | 17.2 | 0.718 |

| 33 | Vinyl acetate | 344.9 | 254.8 | 4.4 | 15.6 | 6.2 | 7.2 | 3.7 | 18.2 | 0.716 |

| 34 | Butylamine | 360.4 | 270.1 | 4.7 | 15.5 | 5.5 | 7.1 | 3.5 | 17.9 | 0.716 |

| 35 | N,N,N′,N′-Tetramethylmethanediamine | 364.9 | 279.8 | 5.2 | 15.9 | 2.4 | 5.9 | 2.8 | 17.3 | 0.714 |

| 36 | Isopropyl formate | 339.2 | 256.9 | 4.2 | 15.3 | 5.7 | 7.5 | 4.1 | 17.9 | 0.708 |

| 37 | Ethyl methyl carbonate | 373.0 | 283.4 | 4.5 | 15.3 | 7.3 | 6.1 | 4.7 | 18.0 | 0.708 |

| 38 | Methyl acrylate | 340.9 | 251.2 | 4.6 | 15.6 | 6.2 | 7.2 | 3.7 | 18.2 | 0.707 |

| 39 | Allyl vinyl ether | 335.5 | 244.3 | 3.9 | 15.2 | 5.3 | 6.5 | 3.8 | 17.3 | 0.701 |

| 40 | Butylmethylamine | 372.2 | 281.3 | 4.5 | 15.3 | 3.5 | 5.1 | 3.5 | 16.5 | 0.701 |

Most components in Table 5 include at least an oxygen atom into the linear and the cyclic molecular structure. The majority of candidates belong to the ester chemical family. Good candidates contain nitrogen atom into the linear and the cyclic molecular structure. Some candidates also include double and triple bonds between carbon atoms. The presence of oxygen and nitrogen atoms improves the Hansen parameters of

The best candidate according to the IBSS CAMD search is the allyl acetate with a

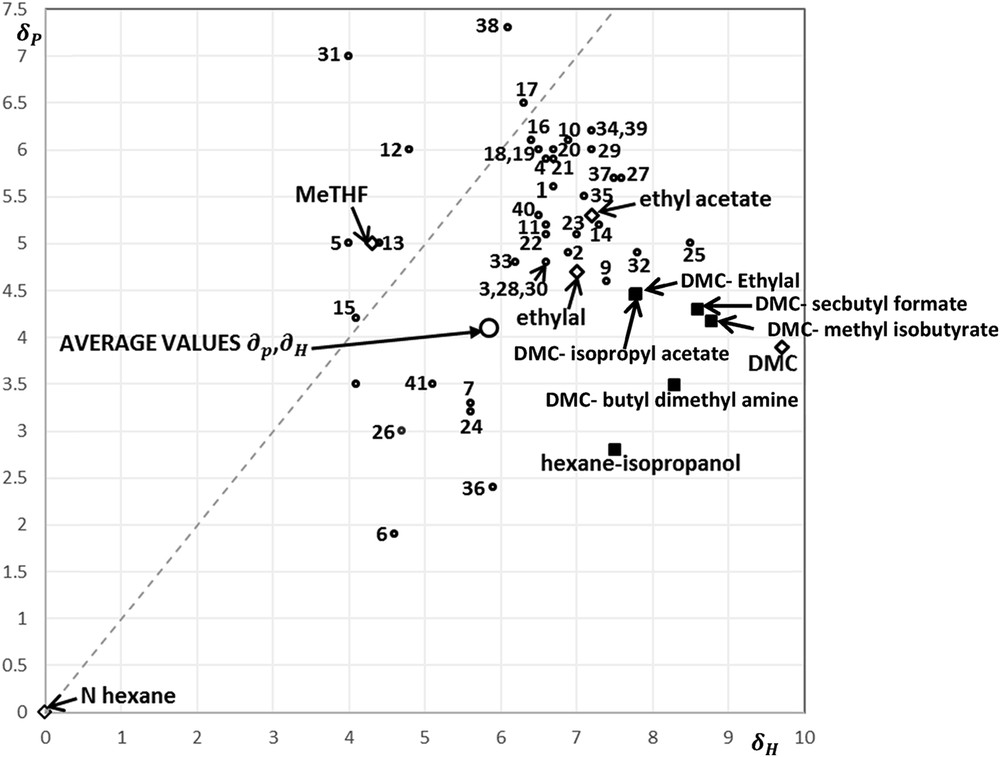

Fig. 4 displays the location of the Hansen parameters

Hansen parameters for studied solvents, new alternative solvents as pure components and binary azeotropic mixtures.

6 Results for alternative solvents as azeotropic binary mixture

The binary azeotropic mixture n-hexane–isopropanol with a mass composition of 0.22 of isopropanol and a BP of 335.15 K has demonstrated in industrial practice being a competitive alternative solvent to hexane alone for aroma extraction. This binary azeotrope provided two main advantages. First, a low composition of the polar alcohol provides an intermediate polarity to the mixture and expands the extraction spectrum of aromas. Second, it has a BP lower than that of n-hexane. Therefore, the binary azeotrope can be easily recovered by a single step of vacuum evaporation allowing its recyclability with a very low solvent makeup. However, both pure components have a very low FP and the mixture also belongs to the high flammable solvent class.

The design of a binary azeotropic mixture was carried out by considering the full list of candidates obtained from IBSS CAMD (Table 3) as well as the studied alternative solvents ethyl acetate, MeTHF, and ethylal (see Table 2). DMC was selected as the main component in the binary mixture because it is considered as a safe solvent exhibiting a good relationship between the BP and the FP. According to general guidance [28], formation of the binary azeotrope with DMC is promoted by components having a difference in the boiling temperature of ±5 K as compared to those of DMC (363.15 K). At that time, we expected that the position of DMC in Fig. 3 can be shifted toward the average values of

With a limited number of mixtures to study and seek an accurate description of the nonideal behavior in these mixtures, Simulis Thermodynamics was used for computing the composition and temperature of the binary azeotropic mixture at 101325 Pa as well as the FP using the modified UNIFAC Dortmund as a thermodynamic model. In the same manner, the solubility of the azeotropic binary mixture in water was determined from the ternary LLE calculation at 298.15 K. Values of log(Ws) can be calculated from the computed mass composition in the water-rich phase. The affinity between the binary mixture and target solutes in aroma was determined from the computation of the RED (Ra from Eq. 4) as well as the Hildebrand solubility as we have done for pure components (Tables 2 and 3). For that, Hansen parameters of binary mixtures were computed using a linear model including the volume fraction of each component [32].

Results of binary azeotropic mixtures are shown in Table 6. It should be noted that ethyl acetate and MeTHF do not form any azeotropic mixture with DMC because they are not close boiling components with DMC. On the other hand, as both components forming the azeotropic mixture have a limited solubility in water, the individual performance

Azeotropic binary mixtures as alternative solvents (property unit as in Table 1).

| Compound 1 | Compound 2 | BPa | (x1)b | FP | Ra | |||||

| n-Hexane | Isopropanol | 333.15 BPmin | 0.712 | 260.23 | 15.3 | 2.8 | 7.5 | 4.0 | 17.3 | 0.697 |

| DMC | Ethyl acetate | Zeotropic | ||||||||

| DMC | MeTHF | Zeotropic | ||||||||

| DMC | Ethylal | 358.65c BPmin | 0.385 | 276.2c | 15.1 | 4.5 | 7.8 | 4.3 | 17.5 | 0.697 |

| DMC | Isopropyl acetate | 365.65c BPmax | 0.33 | 284.1c | 15.4 | 4.5 | 7.8 | 3.7 | 17.8 | 0.809 |

| DMC | sec-Butyl formate | 366.65c BPmax | 0.17 | 285.83c | 15.6 | 4.3 | 8.6 | 3.9 | 18.3 | 0.816 |

| DMC | Methyl isobutyrate | 362.35c BPmin | 0.66 | 284.65c | 15.5 | 4.2 | 8.8 | 4.2 | 18.3 | 0.768 |

| DMC | Butyl dimethyl amine | 360.15c BPmin | 0.68 | 290.15c | 15.5 | 3.5 | 8.3 | 3.9 | 17.9 | 0.908 |

a BP of the binary azeotrope.

b Mass fraction of compound 1.

c Simulis Thermodynamics VLE calculation.

The binary azeotropic mixtures with isopropyl acetate, sec-butyl formate, methyl isobutyrate, and butyl dimethyl amine display a

Fig. 4 displays the position of all binary azeotropic mixtures with DMC. They are all closer than DMC alone to the targeted average values of

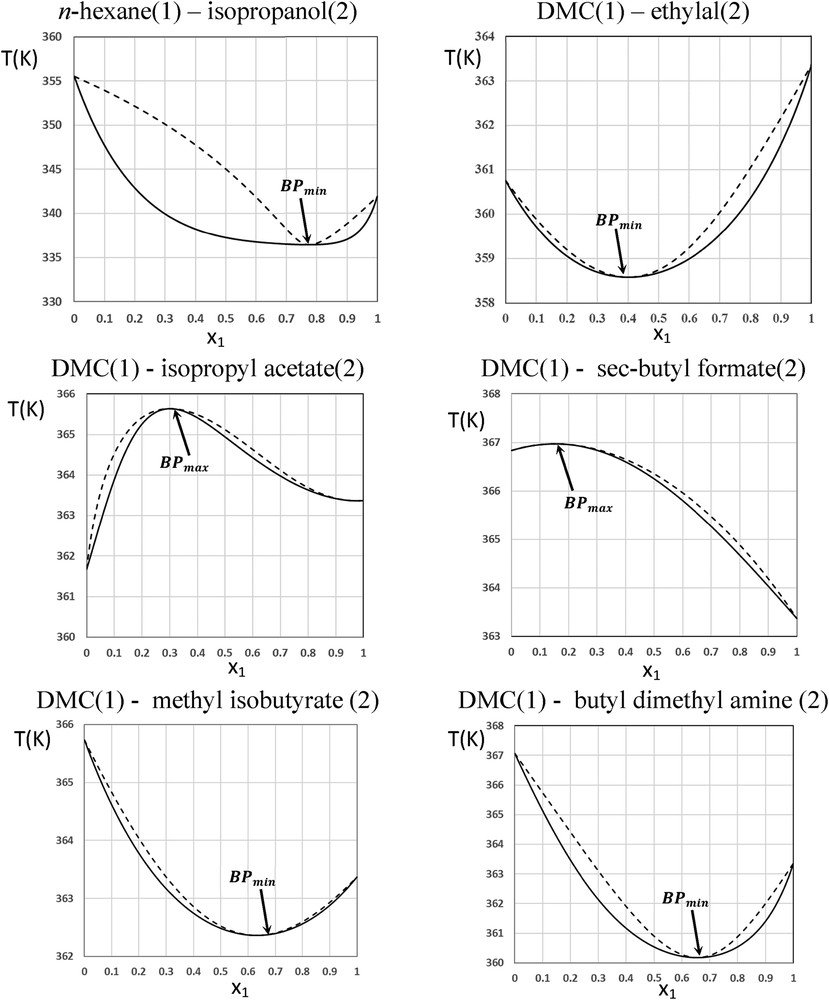

Fig. 5 displays the boiling and dew curves for each binary azeotropic mixture with DMC. Even if the azeotropic mixtures, DMC–isopropyl acetate and DMC–sec-butyl formate, are BPmax mixtures, their boiling temperatures are lower than 373.15 K and hence,

Binary VLE of azeotropic mixtures at 101325 Pa. Boiling temperature curve (continuous lines); dew temperature curve (discontinuous lines).

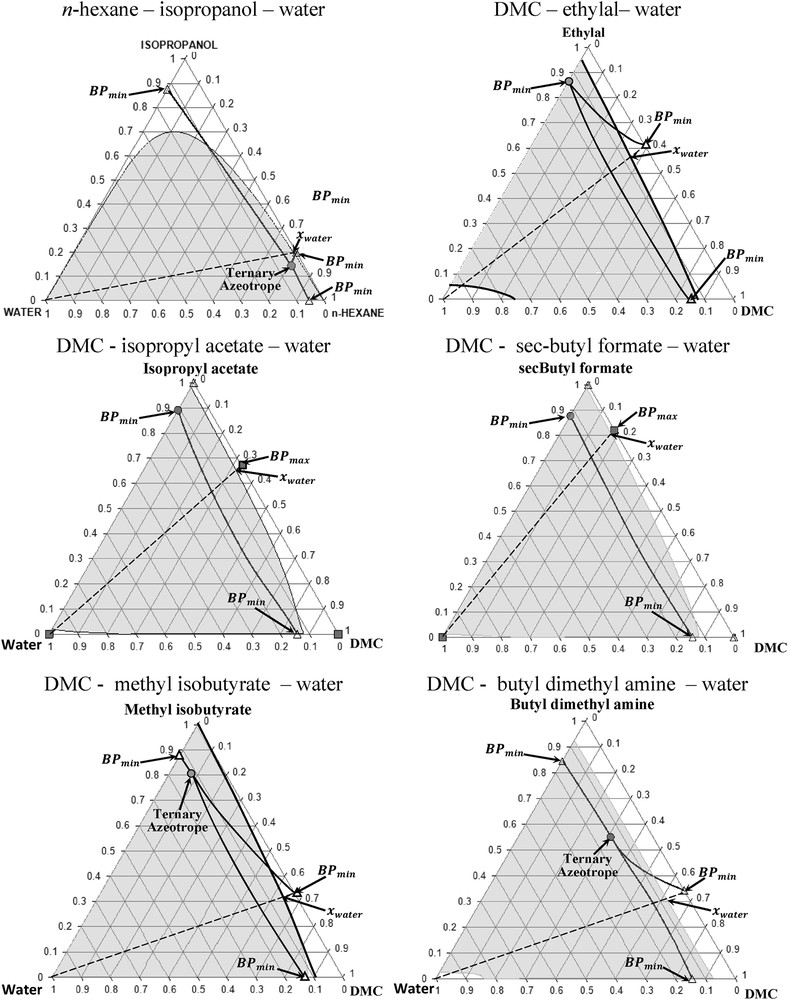

Fig. 6 displays the VLE of all binary mixtures shown in Fig. 4 containing water as the third component. The low solubility between each binary azeotropic mixture and water is verified via rigorous computation of the LLE by Simulis Thermodynamics at 298.15 K and using modified UNIFAC Dortmund as a thermodynamic model. It can be observed in Fig. 6 that a large miscibility gap region exists in all ternary mixtures including DMC validating the assumption of the individual performance

Ternary VLE at 101325 Pa and LLE at 298.15 K.

The following key remarks arose from Fig. 6. In the case of the azeotropic mixture n-hexane–isopropanol, the ternary mixture exhibits a ternary azeotrope having the lowest boiling temperature. Hence, water impurity in the extract will be eliminated in the first distillate cut. The maximum mass fraction of water (xwater) is 0.01 in the organic phase of the binary azeotrope n-hexane–isopropanol, whereas the miscibility gap covers the pure water vertex demonstrating the immiscible nature of this binary azeotrope in water. In the case of ethylal, the maximum mass fraction of water (xwater) is 0.065. However, the binary azeotrope ethylal–DMC exhibits a higher miscibility, xazeo of 0.1 (mass fraction), in the water-rich phase region (see Fig. 6). There is no ternary azeotrope in the mixture ethylal–DMC–water. Nevertheless, the amount of water in the extract can be easily eliminated as the first distillate cut of the heterogeneous binary azeotrope with ethylal, which has the lowest boiling temperature of the ternary mixture [39]. Later, ethylal and water can be separated by decantation. Similar situation exists for isopropyl acetate and the sec-butyl formate, where there is no ternary azeotropic mixture because of the presence of the maximum boiling binary azeotropic mixture with DMC (BPmax). The maximum mass fraction of water (xwater) in the organic phase is lower than 0.03 and 0.02 for isopropyl acetate and for sec-butyl formate, respectively. In both cases, the solubility of the binary azeotrope is very low as the position of xazeo is close to the water vertex. The content of water will be eliminated in the distillate of the binary heteroazeotropic mixtures isopropyl acetate–water and sec-butyl formate–water because both azeotropes have the lowest boiling temperature of their respective ternary mixture. Ternary VLE for methyl isobutyrate and butyl dimethyl amine is similar to that of n-hexane–isopropanol. The maximum mass fraction of water (xwater) is 0.045 for the binary azeotrope DMC–methyl isobutyrate and 0.075 for DMC–butyl dimethyl amine. Comparing both liquid–liquid ternary equilibrium, the organic phase DMC–butyl dimethyl amine azeotrope displays a higher solubility in water given by the position of xazeo in the water-rich phase region. The excess of water can be eliminated in the distillate of the ternary heterogeneous azeotropic mixture.

7 Conclusions

A systematic methodology has been developed for the design of tailor-made alternative solvents, including binary azeotropic mixtures based on the combination of reverse engineering approach and CAPD tool. The knowledge-based method has been used for the identification of the new solvent specifications, the translation to target physicochemical properties, and for the setting of the target values. On the basis of the CAPD principles, the chemical structures of pure components as first solvent candidates are build and modified using a list of chemical groups to maximize a global performance function, which evaluates the matching of the candidate properties with a set of multiple target physicochemical property. FP of the alternative solvent was considered in this study as the most critical physicochemical property in the molecular design of the new alternative solvents because the most used solvents are highly flammable. Solution of the optimization problem of CAPD provided a list of new alternative solvents for the extraction of volatile aromatic compounds from plants with a better global performance than existing ones in industrial practice such as n-hexane, ethyl acetate, and DMC. Binary azeotropic mixtures were then designed to improve the global performance of pure component solvents. DMC was retained as a fixed component in the binary azeotropic mixture because of its good performance regarding the ratio between the boiling temperature and the FP. The second component was selected from the molecule list generated by a CAPD tool with a boiling temperature close to that of DMC. Computation of the boiling temperature and composition of the binary azeotropic mixture was carried out using rigorous model of VLEs, which are able to capture the nonideal behavior in mixtures. In the same way, the limited solubility in water of the binary azeotropic mixtures was calculated using liquid–liquid thermodynamic models, whereas the recyclability of the azeotropic mixture was analyzed based on the ternary VLE. Binary azeotropic mixtures exhibited a better performance than the best new designed and the existing solvents. The short list of pure component and azeotropic mixture candidates, however, need further experimental verification before moving into production because of the inherent inaccuracy of the group contribution methods mainly for calculating the water solubility and the Hansen parameters for pure components. A deep analysis of the environmental, health, and safety properties has to be done as well.