Contribution invited on the occasion of the Emile Jungfleisch Prize of the French Academy of Sciences.

1. Introduction

Multicomponent reactions (MCRs) [1, 2] are chemical transformations in which three or more starting materials react in one convergent single-operation procedure to generate one product. This strategy is almost as old as organic chemistry, since as early as 1850 Strecker published the first three-component reaction for amino acid synthesis [3]. In the context of chemistry for sustainable development, MCRs have received a renewed attention over the last twenty years [4, 5, 6, 7, 8]. These multiple bond-forming transformations [9] are, inherently step-economy reactions, but the criteria of atom-economy is also largely considered since most of the atoms in the starting material are generally incorporated in the final product. If one also put forward their ease of implementation and processing, MCRs can definitively be considered as modern synthetic tools. MCRs can be triggered by numerous types of promoters or catalysts, and the use of heterogeneous and recyclable ones further increases the eco-compatible nature of these reactions [10, 11, 12, 13, 14].

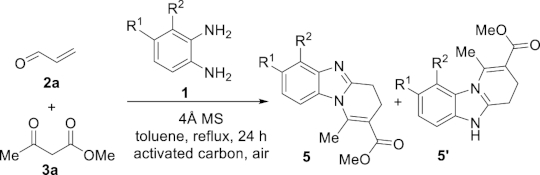

Some time ago, some of us discovered that molecular sieves could promote some original MCRs for the syntheses of complex polyheterocyclic molecules [15, 16]. The general sequence consisted in the reaction between a β-dicarbonyl compound, an α, β-unsaturated carbonyl derivative and a primary amine functionalized by a pendant nucleophilic function, affording the desired product with production of water as the only co-product. In particular, this approach was successfully applied to the synthesis of tri- and tetracyclic fused benzimidazoles via the reaction of o-amino aniline (1a) with various α, β-unsaturated aldehydes 2 and β-diketones, β-ketoesters or β-ketoamides 3, allowing a facile one-pot access to functionalized pyrido[1,2-a]benzimidazoles 5 (Scheme 1) [17]. The intermediate 4 of the MCR, with a dihydrobenzimidazole moiety, contains an aminal function, that is in situ oxidized in the presence of activated carbon and air, leading to the final polyheterocycle.

MCR for the synthesis of pyrido[1,2-a]benzimidazoles.

Benzimidazoles are recognized as privileged heterocycles that exhibit a wide range of pharmaceutical applications and are present in many clinically useful drugs [18, 19, 20, 21, 22]. Owing to this substantial importance, numerous efforts have been made to generate libraries of these compounds [23, 24]. Among them, ring-fused [1,2-a]benzimidazoles have received particular attention [25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31], and synthetic approaches are still needed. In this context, our methodology (Scheme 1) offered a direct multicomponent access to this motif, especially well designed in the context of sustainable chemistry. Since the discovery of these reactions, we have envisioned several plausible mechanisms to account for the efficient formation of the benzimidazole products. The purpose of the work detailed herein is to determine a plausible mechanism for these heterogeneous three-component reactions using a combined experimental and theoretical approach. Particularly, the role of molecular sieves in promoting Michael reactions has been modeled. Finally, the extension of the scope to unsymmetric aromatic diamines has been explored experimentally and rationalized theoretically providing a practical regioselective synthesis of new fused bicylic benzimidazoles.

2. Experimental: general procedure for the synthesis of compounds 5

To a 50-mL two-necked round-bottom flask flushed with air, equipped with a magnetic stirring bar and a condenser, were added anhydrous toluene (25 mL), 4 Å MS (6 g), activated carbon (100 mg, DARCO G-60, −100 mesh), β-ketoester 3a (1.0 equiv), freshly distilled acrolein (2a) (1.2 equiv), and diamine 1 (1.0 equiv). The heterogeneous mixture was stirred at reflux in an open-to-air reaction vessel for 24 h. The reaction mixture was filtered through a short pad of Celite®, which was thoroughly washed with toluene. The solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure to afford the product 5 with good chemical purity (>90% by 1H NMR) and the pure product was obtained after flash chromatography over silica gel.

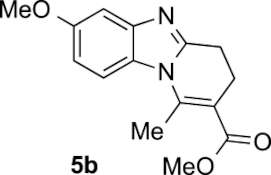

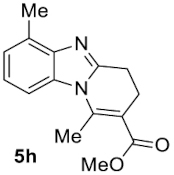

Compound 5b: following the general procedure with 0.19 mL of 3a (1.76 mmol), 0.14 mL of 2a (2.10 mmol) and 237 mg of 1b (1.72 mmol), 303 mg (65%) of 5b were obtained as a dark yellow solid. Recrystallisation of this material from ethyl acetate/toluene afforded light brown prisms suitable for X-ray diffraction analysis (CCDC 1848882).

Mp: 117–119 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO, ppm) δ 7.68 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 7.16 (d, J = 2.5 Hz, 1H), 6.85 (dd, J = 9.0, 2.5 Hz, 1H), 3.79 (s, 3H), 3.74 (s, 3H), 2.97 (dd, J = 8.7, 6.5 Hz, 2H), 2.86 (s, 3H), 2.67 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H); 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, DMSO, ppm) δ 167.2, 155.9, 152.9, 144.4, 143.7, 126.5, 113.8, 111.6, 111.5, 102.5, 55.5, 51.7, 23.0, 21.6, 17.4; HRMS (ESI+) [M+H]+ C15H17N2O3+: calcd. 273.1234; found: 273.1235.

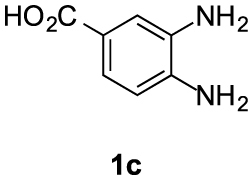

Compound 5c′: following the general procedure with 0.19 mL of 3a (1.76 mmol), 0.14 mL of 2a (2.10 mmol) and 262 mg of 1c (1.72 mmol), 169 mg (34%) of 5c′ were obtained as a white solid. Mp: 210–212 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO, ppm) δ 8.33 (s, 1H), 7.91–7.86 (m, 1H), 7.68 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 3.76 (s, 3H), 3.08–3.01 (m, 2H), 2.92 (s, 3H), 2.71 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H); 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, DMSO, ppm) δ 167.1, 155.4, 146.4, 143.2, 132.0, 124.1, 118.9, 114.8, 112.9, 51.8, 23.0, 21.5, 17.3; HRMS (ESI+) [M+H]+ C15H15N2O: calcd. 287.1026; found: 287.1023.

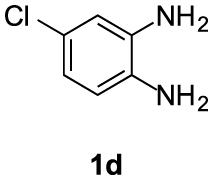

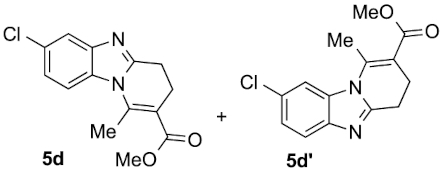

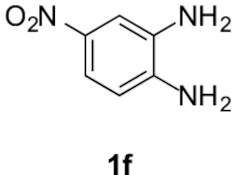

Compounds 5d and 5d′: following the general procedure with 0.19 mL of 3a (1.76 mmol), 0.14 mL of 2a (2.10 mmol) and 245 mg of 1d (1.72 mmol), 214 mg (45%) of 5d and 108 mg (23%) of 5d′ were obtained as white solids.

5d: Mp: 85–87 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO, ppm) δ 7.82 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 7.69 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H), 7.28 (dd, J = 8.8, 2.1 Hz, 1H), 3.75 (s, 3H), 3.01 (dd, J = 8.6, 6.6 Hz, 2H), 2.86 (s, 3H), 2.69 (dd, J = 10.7, 4.4 Hz, 2H); 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, DMSO, ppm) δ 167.0, 154.2, 144.3, 143.1, 131.0, 127.1, 122.8, 118.8, 114.7, 112.8, 51.7, 22.9, 21.5, 17.3; HRMS (ESI+) [M+H]+ C14H14ClN2O: calcd. 277.0733; found: 277.0735.

5d′: Mp: 129–131 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO, ppm) δ 7.87 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H), 7.63 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 7.30 (dd, J = 8.5, 1.9 Hz, 1H), 3.75 (s, 3H), 3.00 (dd, J = 8.6, 6.5 Hz, 2H), 2.87 (s, 3H), 2.69 (dd, J = 10.6, 4.4 Hz, 2H); 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, DMSO, ppm) δ 167.0, 153.7, 143.2, 142.1, 132.7, 127.4, 123.0, 120.4, 113.3, 112.9, 51.7, 22.9, 21.5, 17.2; HRMS (ESI+) [M+H]+ C14H14ClN2O: calcd. 277.0733; found: 277.0729.

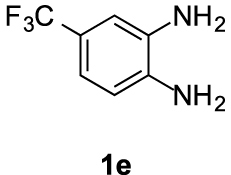

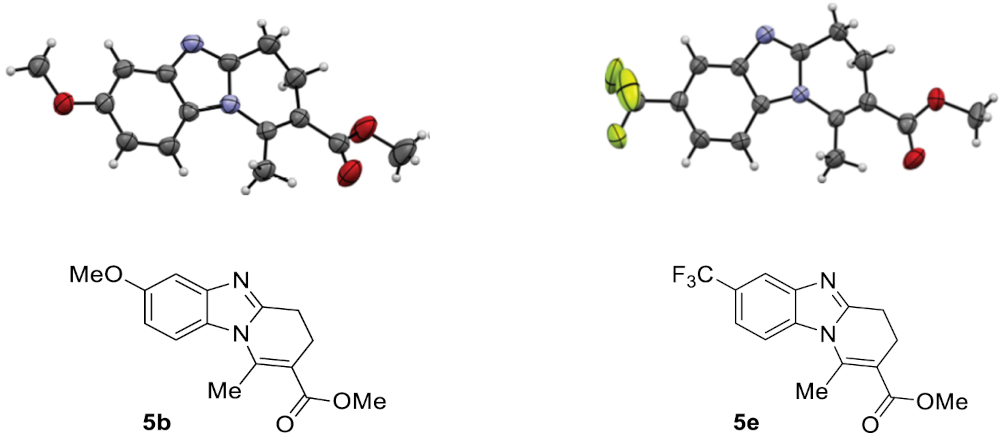

Compounds 5e and 5e′: following the general procedure with 0.19 mL of 3a (1.76 mmol), 0.14 mL of 2a (2.10 mmol) and 303 mg of 1e (1.72 mmol), 159 mg (30%) of 5e and 242 mg (45%) of 5e′ were obtained as white solids. Recrystallisation of 5e from ethyl acetate/toluene afforded colorless prisms suitable for X-ray diffraction analysis (CCDC 1848550).

5e: Mp: 136–143 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO, ppm) δ 8.02 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H), 7.98 (s, 1H), 7.60–7.55 (m, 1H), 3.76 (s, 3H), 3.06 (dd, J = 8.5, 6.5 Hz, 2H), 2.89 (s, 3H), 2.71 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H); 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, DMSO, ppm) δ 167.0, 155.0, 142.9, 142.8, 134.5, 124.7 (q, J = 271.6 Hz), 123.5 (q, J = 31.4 Hz), 119.6 (q, J = 3.5 Hz), 116.3 (q, J = 3.8 Hz), 114.3, 113.7, 51.8.

5e′: Mp: 110–112 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO, ppm) δ 8.08 (s, 1H), 7.82 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.60 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 3.76 (s, 3H), 3.06 (dd, J = 9.0, 7.1 Hz, 2H), 2.92 (s, 3H), 2.71 (dt, J = 7.5, 1.3 Hz, 2H); 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, DMSO, ppm) δ 167.0, 155.7, 145.8, 143.0, 131.8, 124.7 (q, J = 272.1 Hz), 123.4 (q, J = 31.5 Hz), 120.0, 119.6 (q, J = 3.5 Hz), 113.4, 110.8 (q, J = 4.3 Hz), 51.8, 23.0, 21.4, 17.2; HRMS (ESI+) [M+H]+ C15H14F3N2O: calcd. 311,1002; found: 311,1001.

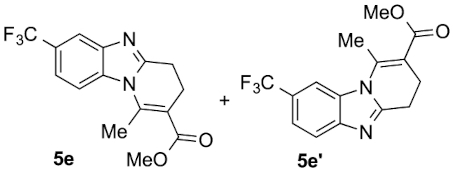

Compounds 5f and 5f′: following the general procedure with 0.19 mL of 3a (1.76 mmol), 0.14 mL of 2a (2.10 mmol) and 263 mg of 1f (1.72 mmol), 54 mg (11%) of 5f and 264 mg (54%) of 5f′ were obtained as orange solids.

5f: Mp: 141–144 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO, ppm) δ 8.63 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 8.18 (dd, J = 8.9, 2.2 Hz, 1H), 7.83 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 1H), 3.77 (s, 3H), 3.10 (dd, J = 8.6, 6.7 Hz, 2H), 2.95 (s, 3H), 2.73 (t, J = 6.8 Hz, 2H); 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, DMSO, ppm) δ 166.9, 158.0, 147.8, 143.0, 142.6, 131.5, 119.5, 118.4, 113.8, 109.9, 51.9, 23.0, 21.3, 17.1; HRMS (ESI+) [M+H]+ C14H14N3O: calcd. 288.0979; found: 288.0967.

5f′: Mp: 134–136 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO, ppm) δ 8.48 (d, J = 2.3 Hz, 1H), 8.15 (dd, J = 9.1, 2.3 Hz, 1H), 8.04 (d, J = 9.1 Hz, 1H), 3.77 (s, 3H), 3.09 (dd, J = 8.5, 6.6 Hz, 2H), 2.89 (s, 4H), 2.73 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H); 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, DMSO, ppm) δ 166.9, 156.6, 143.1, 142.9, 142.4, 136.5, 118.4, 114.8, 114.6, 113.8, 51.9, 22.9, 21.4, 17.3; HRMS (ESI+) [M+H]+ C14H14N3O: calcd. 288.0979; found: 288.0977.

Compound 5g: following the general procedure with 0.19 mL of 3a (1.76 mmol), 0.14 mL of 2a (2.10 mmol) and 267 mg of 1g (1.74 mmol), 312 mg (62%) of 5g were obtained as a purple solid. Mp: 152–158 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO, ppm) δ 8.26 (dd, J = 8.3, 0.7 Hz, 1H), 8.04 (dd, J = 8.1, 0.7 Hz, 1H), 7.45 (t, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 3.77 (s, 3H), 3.11 (dd, J = 8.6, 6.7 Hz, 2H), 2.89 (s, 3H), 2.73 (dd, J = 10.7, 4.4 Hz, 2H); 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, DMSO, ppm) δ 166.9, 156.6, 142.5, 138.6, 136.5, 134.7, 122.5, 119.7, 118.8, 114.4, 51.9, 22.9, 21.3, 17.5; HRMS (ESI+) [M+H]+ C14H14N3O: calcd. 288.0979; found: 288.0975.

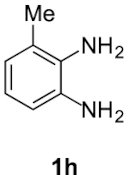

Compound 5h: following the general procedure with 0.19 mL of 3a (1.76 mmol), 0.14 mL of 2a (2.10 mmol) and 215 mg of 1h (1.76 mmol), 324 mg (72%) of 5h were obtained as a white solid. Mp: 95–97 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3, ppm) δ 7.47 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 7.14 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.08 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H), 3.81 (s, 3H), 3.09 (dd, J = 8.5, 6.6 Hz, 2H), 2.93 (s, 3H), 2.77 (td, J = 7.4, 1.2 Hz, 2H), 2.64 (s, 3H); 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3, ppm) δ 167.7, 151.9, 144.4, 142.7, 132.1, 129.9, 123.7, 123.1, 112.8, 110.5, 51.8, 23.8, 22.1, 18.0, 16.7; HRMS (ESI+) [M+H]+ C15H17N2O: calcd. 257.1285; found: 257.1286.

3. Results and discussion

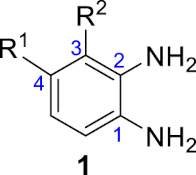

This study aimed at answering two interlinked questions: (1) What is the nature and the order of the elemental steps leading to the benzimidazole products 5 from the simple substrates 1–3? And (2) What is the actual role of the 4 Å MS, an acidic (Lewis and Brønsted acidities) microporous crystalline material composed of sodium aluminosilicates capable of trapping molecules of water with high efficiency? It was previously experimentally demonstrated that 4 Å MS are capable of accelerating the Michael addition of the β-ketoester 3a to acrolein (2a), and that the reaction does not proceed at a significant rate in its absence [32]. Because of the acidic nature of 4 Å MS, only the neutral enol form of the nucleophilic β-ketoester 3a should be considered. A possible mechanism of the reaction is depicted in Scheme 2 (Path A). The reaction would start with a 4 Å MS-catalyzed Michael addition of 3a under its enol form to acrolein (2a) giving the corresponding adduct 6a. The latter would then react with the diamine 1a to form the imine 7a, the double cyclization of which would afford consecutively the aminal 8a and then the cyclic mixed hemiaminal 9a, precursor of the dihydrobenzimidazole 4a following dehydration. Alternatively, it is also possible that the diamine 1a initially reacts with acrolein to give the corresponding α, β-unsaturated imine 10a that would in turn undergo the Michael addition with the β-ketoester 3a to give the imine 7a (Path B), the rest of the sequence being common to both mechanisms. Individually, both the reactions 2a + 3a → 6a and 1a + 2a → 10a do occur under the reaction conditions in the absence of the third component (1a in the former case and 3a in the latter case).

Two plausible mechanistic scenarios.

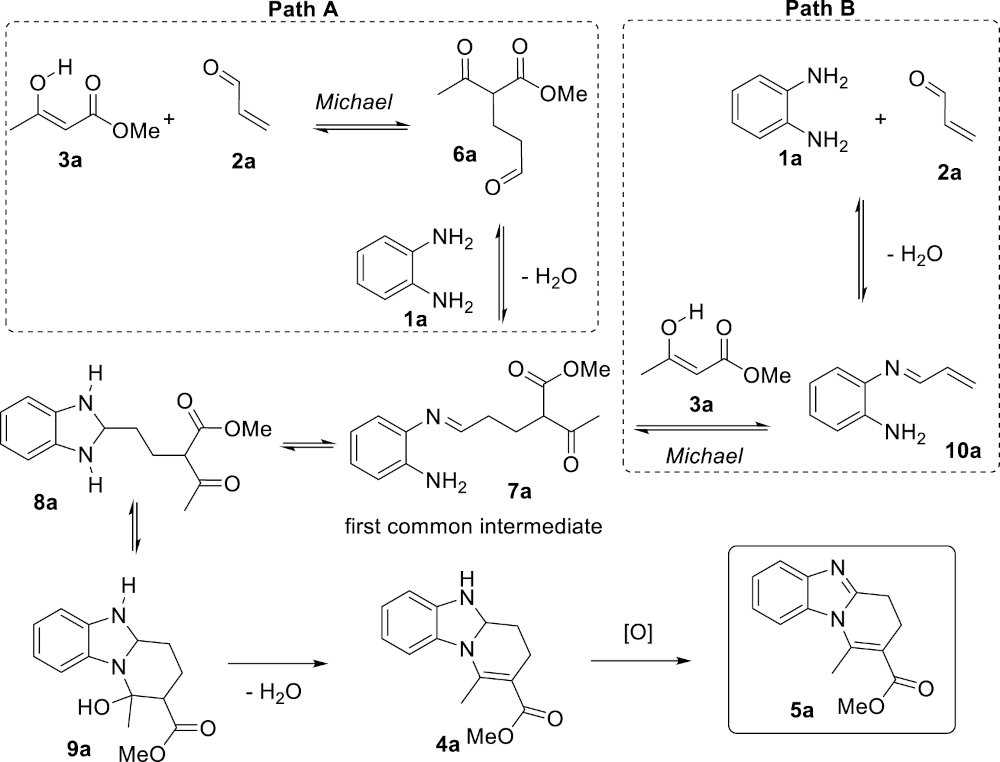

Both scenarios were computationally examined using DFT methods to compare their energy profiles leading to the first common intermediate 7a. All calculations were performed with the Gaussian 16 suite of programs [33]. The M06-2X/6-31G(d,p) method, a functional now recognized performant for systems where main-group thermochemistry, kinetics and non-covalent interactions are all important [34], was employed in optimizing the structures along competitive reaction pathways and evaluating the respective electronic energies in vacuum. The chosen basis set was a compromise between accuracy and calculation time. Frequency calculations for each optimized structure were performed at the same level of theory in order to analyze the nature of stationary points (minima or transition states). The vibrational frequencies were used to compute zero-point energy (ZPE) and Gibbs free energies corrections. Single point calculations at the M06-2X/6-311 + +G(d,p) level combined with polarizable continuum model [35, 36] (IEFPCM) for toluene solvent were performed in order to reach more accurate electronic energy values. As 4 Å molecular sieves contain many silanol moieties at their surface, it was modeled by one molecule of Si(OH)4 all along the reaction profiles [37, 38, 39, 40, 41], and tunneling effect [42] was taken into account for one step with a very high imaginary frequency involving the intramolecular transfer of a proton. Of course, each intermediate identified along the reaction paths exists as multiple conformers with various non-covalent interactions with the Si(OH)4 catalyst, and only the most stable ones among those identified are reported herein. The actual heterogeneous catalytic system is a complex acidic network, ensuring both efficient bond-formation and proton transfers, that is very difficult to reproduce in silico. Thus, the calculated activation barriers herein are probably over-estimated but qualitatively reliable.

For path A, the Michael addition of the enol form of methyl acetoacetate (3a) to acrolein (2a) was found moderately exothermic with a reasonable activation barrier to afford the adduct 6a-enol, the tautomerization of which leading to the corresponding aldehyde 6a with a relatively high computed barrier (Scheme 3). Keto–enol tautomerism is routinely introduced in textbooks as an intramolecular 1,3-shift of a proton although the actual process is far more complex, involving several molecules and/or catalysts. As a consequence, the accurate modeling of keto–enol tautomerism is a complex and very difficult task, sometimes leading to aberrant results [43]. In the present case, the tautomerism of 6a-enol was modeled with a single molecule of silicic acid as catalyst, which afforded an activation free energy ΔG≠ (110 °C) of 142.5 kJ⋅mol-1 corresponding to a rate constant in the magnitude of 10−7 s-1 at 110 °C in the hypothesis of a first order reaction, a value that cannot account for the observed reaction. Considering tunneling effect (see Supporting Information), a much more realistic rate constant of ca. 0.4 s-1 was calculated for this elemental step. From 6a, the reaction continues with the formation of 7a-hemiaminal and its subsequent dehydration to afford the corresponding imine 7a with a barrier calculated at 127.2 kJ⋅mol-1, a value probably over-estimated for the reasons explained above. The capacity of 4 Å MS to act as a trapping agent for the water formed during the reaction is certainly a driving force for the formation of the imine.

Energy profile of both mechanistic scenarios leading to 7a (paths A and B) and relative energy of the aza-Michael adduct 12a (path C). All energies are Gibbs free energies expressed in kJ⋅mol-1 at 298 K.

For path B, the formation of the α,β-unsaturated imine 10a would involve the 1,2-addition of the diamine 1a to acrolein (2a) to give 10a-hemiaminal followed by a dehydration step, which constitutes the rate-limiting step for the formation of the α,β-unsaturated imine 10a. Beside 1,2-addition, the diamine 1a may also react with acrolein (2a) following a 1,4-addition to afford, after tautomerism, the aza-Michael adduct 12a, the relative energy of which was calculated at −93.6 kJ⋅mol−1. The aza-Michael adduct 12a is thus the most stable compound among the various species possibly involved in the early steps of the mechanism (from 1a + 2a + 3a to 7a). We assume that the 1,2 vs 1,4 addition process of the diamine 1a to acrolein (2a) is under thermodynamic control under the reaction conditions. The conclusion is that the resting state of both acrolein (2a) and the diamine 1a is the aza-Michael adduct 12a that forms rapidly after the initiation of the reaction, and that both substrates are slowly released during the reaction maintaining their low concentration (reservoir effect). This scenario is fully consistent with the following experimental facts: (1) imines derived from acrolein (2a) have never been isolated, (2) acrolein decomposes at slow rate in refluxing toluene (essentially unchanged after 24 hours) despite its low boiling point (53 °C) and its tendency to polymerize under acidic conditions, and (3) completion of the reaction requires prolonged reaction time. The conclusions of this part of the study, are that path A (Scheme 2) is most probably the actual mechanism of the reaction, and that 4 Å MS are acting both as a catalyst for the initial Michael addition step leading to 6a and as a dehydrating agent to trap the two equivalents of water formed during the reaction. This results in shifting the corresponding equilibria to the dehydrated products 7a and 4a, respectively.

4. Reaction scope and extension

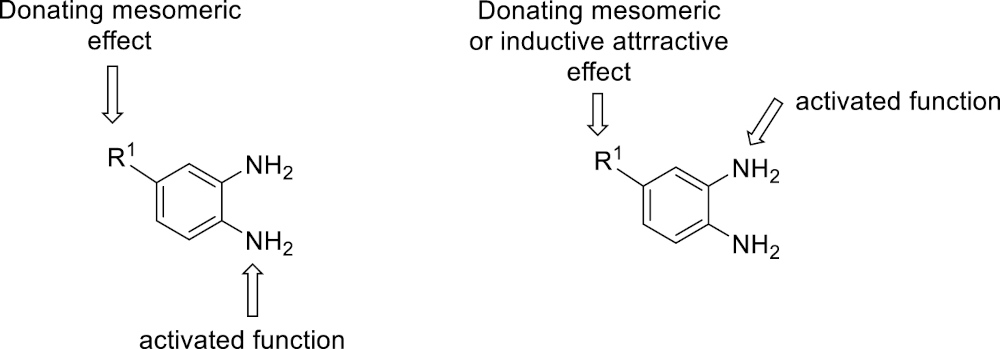

Since the benzimidazole motif is often associated with biological properties, it is important to be able to introduce structural and functional variations on the skeleton. In our preliminary communication [43], various β-dicarbonyl derivatives 3 and different enals 2 were used successfully. With regard to the diamine partner, the study was so far limited to the use of o-phenylenediamine (1a) itself to avoid regioselectivity issues related to the use of unsymmetrical substituted diamines. However, the introduction of a substituent at the position 3 or 4 of the aromatic ring of o-phenylenediamine results in a differentiation of the electron density on each of the two amine functional groups. Considering the formation of the tricyclic mixed hemiaminal intermediate 9 from the aminal 8, as the discriminative step for regioselectivity, it is expected that the most nucleophilic nitrogen atom is the one with the greatest electron density.

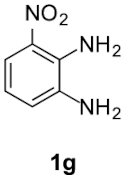

This working hypothesis was studied experimentally and computationally. To this purpose, we selected a representative series of substituted o-phenylenediamines 1b–h bearing functional groups with different electronic effects in position 3 or 4. These substrates were reacted with acrolein (2a) and methyl acetoacetate (3a) under the conditions depicted in Table 1 to afford the corresponding benzimidazoles 5b–h and in some cases their regioisomers 5d′–5f′. Using o-phenylenediamines 1b–f with a functional group in position 4 may lead to the formation of two regioisomers 5 and 5′ of the corresponding benzimidazole. As experimentally established, substrates bearing substituents with either electron-donating (entries 1 and 3) or electron-withdrawing (entries 2, 4, and 5) effects, proceeded with modest to high regioselectivities. This is clearly illustrated by the exclusive formation of 5b with a 4-MeO- (entry 1) and 5c′ with 4-CO2H (entry 2). As expected, the presence of an inductive-only withdrawing substituent induced the lowest regioselectivities (entries 3 and 4). However, in the case of chlorine substituent (entry 3) the additional donating mesomeric effect induced a reversal of the regioselectivity. From a more general point of view, these results indicate that regioisomer 5 is preferentially formed from diamines 1 bearing electron-donating substituents, whereas major or exclusive formation of the other regiosomer 5′ results from the presence of substituent with a withdrawing effect (Figure 1).

Modulation of the reactivity of o-phenylenediamines 1.

| Entry | Substrate 1 | Product 5 | Yield (%)a | Ratio 5 / 5′ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  |  | 65 | 1:ndb |

| 2 |  |  | 34 | ndb:1 |

| 3 |  |  | 68 | 2:1 |

| 4 |  |  | 75 | 1:1.5 |

| 5 |  |  | 65 | 1:5 |

| 6 |  |  | 62 | 1:ndb |

| 7 |  |  | 72 | 1:ndb |

a Isolated yield; b not detected.

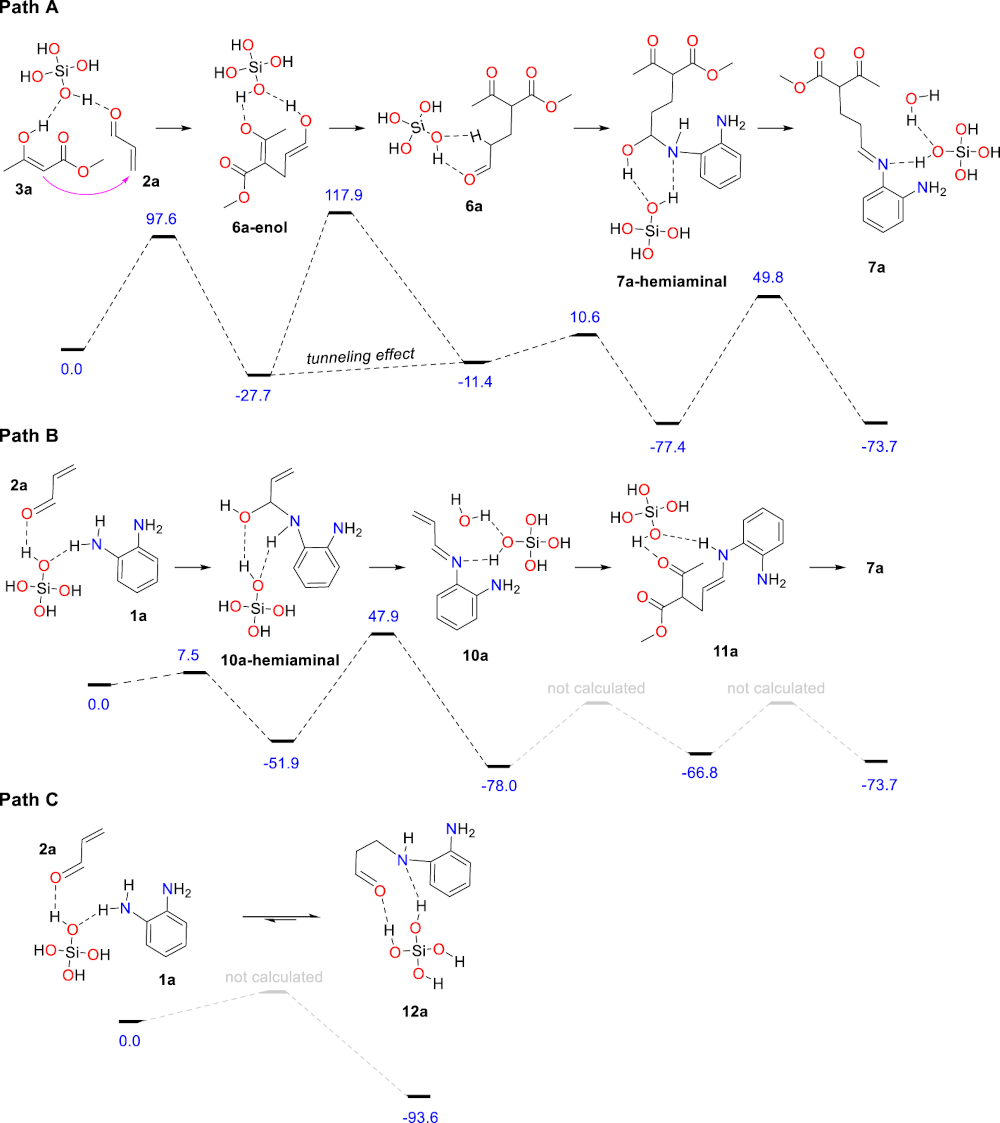

To confirm the regioselectivity observed in these transformations, analysis by X-ray diffraction of a monocrystal of products 5b and 5e were conducted, establishing with no doubt its structures and the position of the substituent on the aromatic ring (Figure 2) [44].

ORTEP views of compounds 5b and 5e; ellipsoids are shown at 50% probability and H atoms are drawn as fixed-size spheres of 0.15 Å radius.

Finally, concerning o-phenylendiamines 1g,h with a functional group in position 3, the reaction led to the formation of a unique regioisomer 5, in both examined cases (entries 6 and 7). In these two cases, the ortho steric effect is certainly largely contributing to the regioselectivity.

A quantitative determination of the electron density was performed theoretically to rationalize the regioselectivity as a function of the substituent in o-phenylenediamines 1 (Table 2). Thus, the geometries of aniline (R =H) and o-phenylenediamines 1a–h were optimized at the MP2/6-31+G(d) level and minima were characterized by the calculation of the vibrational frequencies. Substituent effects were analyzed on the basis of natural population analysis (NPA) [45] charges calculated at the MP2/6-311 + +G(d,p) level using NBO 6.0 package [46]. The MP2 [47, 48] method was preferred to the DFT approach according to the small size of the systems and for a better description of the structural features of these delocalized aromatic compounds.

| Entry | N1/N2 NPA charge | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Aniline (R1 = R2 = R) | −0.102 |

| 2 | 1a | −0.113/−0.113 |

| 3 | 1b | −0.121/0.103 |

| 4 | 1c | −0.092/−0.108 |

| 5 | 1d | −0.109/−0.101 |

| 6 | 1e | −0.096/−0.103 |

| 7 | 1f | −0.085/−0.097 |

| 8 | 1g | −0.101/−0.040 |

| 9 | 1h | −0.119/−0.108 |

In 1a, each amino group is an ortho electron-donating substituent for the other one and the charge on N-1 and N-2 is significantly enhanced when compared to aniline (Table 2: compare entries 1 and 2), resulting in a higher nucleophilicity of 1a and its analogues relative to aniline. The presence of a strong electron-donating 4-methoxy substituent (Table 2: entry 3) enhances the charge on the N-1 atom and also reduces the charge on the N-2 atom. This is in agreement with the experimentally observed higher nucleophilicity of the N-1 atom.

In the case of strong electron-withdrawing substituents at the 4 position (Table 2: entries 4, 6 and 7), the charge on both N-1 and N-2 amino groups is significantly reduced comparatively to 1a, with a relative charge larger for N-2. Again, this is in perfect agreement with the experimental results. In the case of the 4-chloro derivative (Table 2: entry 5) the calculated charges reflect the additional donating mesomeric effect with now the charge on N-1 slightly larger, inducing the observed modest reversed regioselectivity. Finally, for the 3-substituted analogues, the calculated charges were found higher for N-1 in both cases and this combined with the ortho steric effect agrees with the experimental results (Table 2: entries 8 and 9).

5. Conclusion

The present studies bring some complementary experimental and computational insights into our previously reported operationally simple and environmentally friendly molecular sieves-catalyzed three-component synthesis of fused-benzimidazoles. Notably, the role of 4 Å MS in the early steps of the mechanism was investigated rationalizing its effective catalytic properties in the Michael addition. With unsymmetrically substituted o-phenylenediamines, modest to excellent regioselectivities were observed. The regioselectivity can now be predicted based on qualitative steric considerations and the quantitative determination of the electron density of the two nucleophilic amino groups.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR-07-CP2D-06), providing a post-doctoral grant to DC, and the Centre Régional de Compétences en Modélisation Moléculaire de Marseille (Aix-Marseille Université) for computing facilities. Dr. M. Giorgi (Aix-Marseille Université) is gratefully acknowledged for the X-ray analyses. Region PACA and the CNRS are also gratefully acknowledged for providing a PhD grant to FL-M. Finally, VP thanks CONICET for financial support during her training period in France. This article is dedicated to the memory of Dr. Jean-Pierre Dulcère former inspiring mentor and unforgettable friend.

CC-BY 4.0

CC-BY 4.0