1. Introduction

The chemical synthesis of alcohols remains a long-standing challenge. In addition to the time-consuming and sometimes costly preparation of the partially toxic transition metal catalysts, harmful by-products can be produced, or the reaction is dependent on multiple reaction steps (protective group chemistry), harsh reaction conditions and often does not reach the desired selectivity for chiral products [1, 2, 3, 4]. These challenges evoke a sustained interest to explore additional or new approaches. Nature provides an ideal template, offering not only sustainable reaction conditions but also remarkable selectivity often provided by enzymes. The atom-economical, biocatalytic addition of water to alkenes offers an environmentally friendly alternative to the harsh reaction conditions of organic chemistry. Hydratases belong to the enzyme class of hydro-lyases (EC 4.2.1.X) and enable uncomplicated access to secondary and tertiary alcohols, thus opening up new possibilities for their synthesis [5]. The enzymes are categorized into two groups based on their mechanism, the first group comprises hydratases that hydrate conjugated C=C double bonds in α,β-unsaturated carbonyl compounds by a nucleophilic Michael addition. The second group catalyzes the addition of water to non-activated C=C double bonds by an electrophilic addition [6, 7].

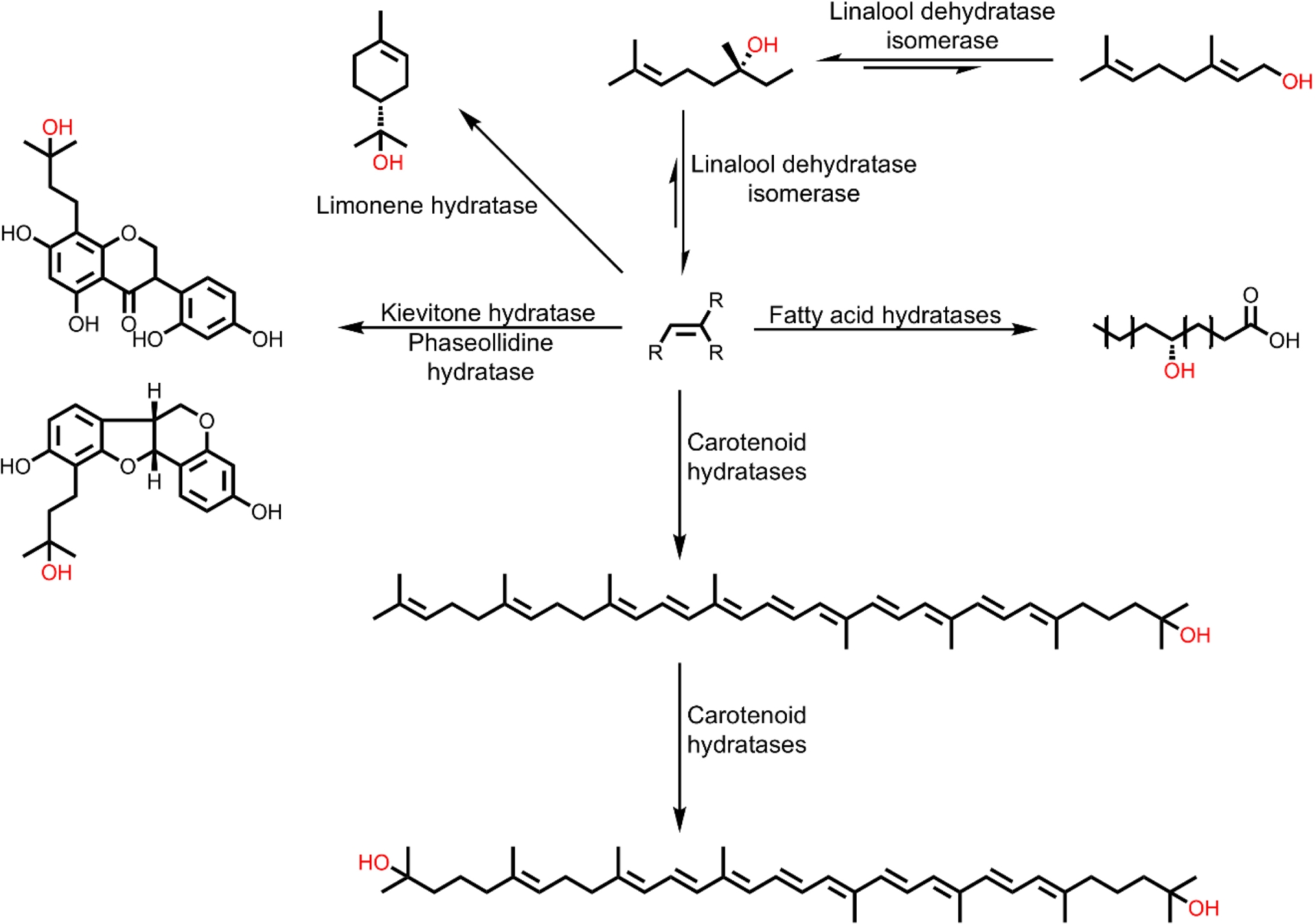

The second group of enzymes is present, for example, in the metabolism of terpenes, where hydratases are involved in the conversion of terpenes by hydrating specific C=C double bonds, thereby forming tertiary alcohols with high selectivity. A prominent example is that of carotenoid hydratases, which catalyze the hydration of terminal prenyl units. Based on their function and their natural substrates, these hydratases are divided into two distinct evolutionary groups, the CrtC superfamily and the CruF family. Both acyclic (e.g., lycopene) and monocyclic (e.g., γ-carotene) carotenoid substrates can be converted to their corresponding hydroxy compounds (Figure S1). An interesting representative example of this enzyme group is the membrane-bound CrtC from Rubrivivax gelatinosus, which can convert the C40 carotenoid lycopene in a regioselective manner to hydroxylycopene and 1,1-dihydroxylycopene and can therefore catalyze both single and double hydration [8, 9, 10]. In addition to the hydration of carotenoids, hydratases such as kievitone hydratase and phaseollidine hydratase have been demonstrated to convert isoflavonoids, including kievitone, xanthohumol, and phaseollidine, to their corresponding hydroxy derivatives (Figure 1) [7, 11, 12]. In addition to very large terpenes, short-chain monoterpenes such as limonene can also be modified by hydratases. Hydrations of limonene have already been observed in yeasts and bacteria, but mostly in whole cell preparations, which means that isolated enzyme studies are rare. An exceptional case is the membrane-bound α-terpineol dehydratase from Pseudomonas gladioli, which was isolated in 1992 [13]. Although the enzyme was classified as a dehydratase, its natural function was shown to be the hydration of limonene to α-terpineol. The only published work on the heterologous expression of a limonene hydratase is by Chang et al. who expressed a limonene hydratase (LIH) from Geobacillus stearothermophilus in E. coli and converted limonene to terpineol [14, 15]. Another interesting case is the bifunctional enzyme linalool dehydratase isomerase (LinD). This enzyme catalyzes the hydration of myrcene to (S)-linalool and its further isomerization to geraniol, as well as the respective reverse reactions, with the formation of myrcene from geraniol being the thermodynamically preferred process [16]. In addition to natural substrates, shortened and extended linalool derivatives could also be converted [16, 17, 18, 19, 20].

Overview of different hydratases adding water to C=C double bonds of different terpenes, terpenoids and fatty acids following the Markovnikov-rule (electrophilic addition).

One of the most frequently used enzymes for the conversion of non-activated C=C double bonds can be found in the cofactor-dependent fatty acid hydratases (FAHs). They catalyze the regioselective addition of water to C=C double bonds of unsaturated fatty acids to form the corresponding hydroxy fatty acids [10, 19]. FAHs have attracted a lot of attention mainly due to their wide distribution in food-safe microorganisms such as Lactobacillus [21]. The oleate hydratase from Elizabethkingia meningoseptica, discovered in 1962, is the most extensively studied FAH. This enzyme catalyzes the conversion of oleic acid to 10-hydroxystearic acid. The enzyme requires flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD) as a cofactor, but its redox state does not change during the reaction. Enzyme engineering has already opened up a broad substrate spectrum with different FAHs. Fatty acids with different chain lengths (C11–C22) or numbers of double bonds (up to 6) as well as oleic acid derivatives with different head groups could be converted [21, 22, 23, 24, 25]. In addition, shorter, non-activated alkenes (C5–C10) were also converted to the corresponding secondary alcohol using a carboxylic acid dummy substrate [26, 27, 28]. Furthermore, the acceptance of alkynes, internal alkenes, substituted alkenes, and styrene derivatives was demonstrated with this dummy substrate [26, 27].

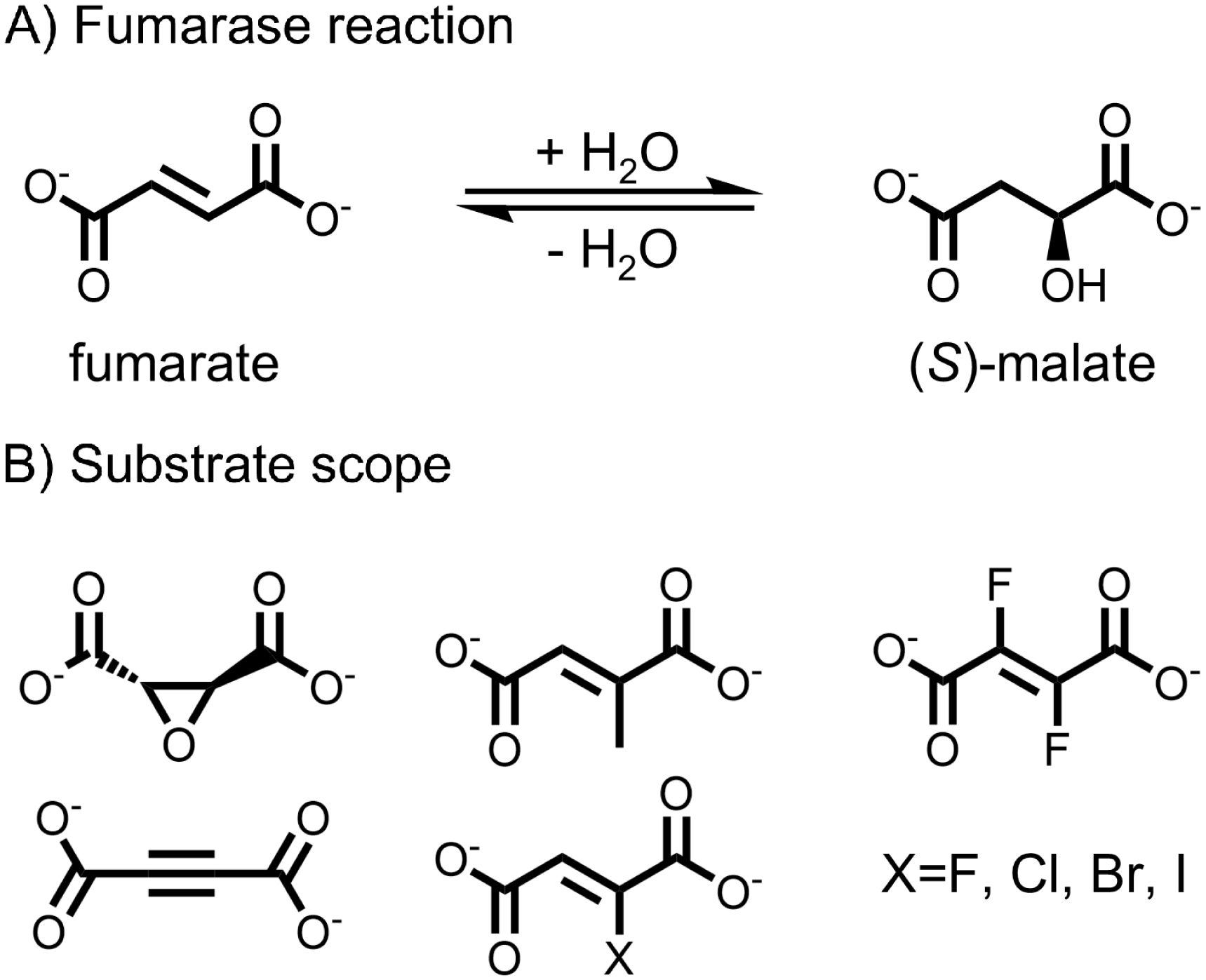

Fumarases, also known as fumarate hydratases, are enzymes catalyzing the reversible hydration of fumarate to malate, a reaction central to the citric acid cycle and ubiquitous across all kingdoms of life (Figure 2A) [29]. Prominent examples include the porcine fumarase, the Saccharomyces cerevisiae fumarase, and the three fumarases from Escherichia coli (FumA, FumB, and FumC). Fumarases are categorized into two classes: class I, dimeric enzymes that contain a 4Fe–4S cluster, and class II, comprising tetrameric, thermostable, cofactor-free enzymes that are well studied due to their robustness [30, 31, 32]. Fumarases are known for their exceptional stereoselectivity, and a narrow substrate scope [33, 34]. From an early stage, halogenated derivatives of fumarate, such as fluorofumarate and chlorofumarate, have been demonstrated to be accepted by class II fumarases, such as the porcine fumarase, which served as an early model enzyme (Figure 2) [35, 36]. In the case of FumA from E. coli, a member of class I fumarases, reports from 1994 state that fluorofumarate is a promiscuous substrate for hydration [37]. Moreover, it was demonstrated that a C≡C triple bond can be accepted by both fumarase classes in the hydration of acetylene dicarboxylate to oxalacetate [35]. It was also shown that the epoxide l-trans-2,3-epoxysuccinate can be transformed to a diol [38].

(A) Fumarases catalyze the reversible hydration of fumarate to (S)-malate. (B) The substrate scope reported for fumarases is limited to structures very close to fumarate and malate.

Among the fumarases of E. coli, FumA and FumB are class I enzymes that share 90% sequence homology [39]. FumC is a class II fumarase, like the fumarases found in eukaryotic organisms, and is therefore structurally very different from FumA and FumB [31]. The expression of the three fumarases in E. coli varies with oxygen availability, carbon source, and growth conditions [37, 40]. While FumA predominantly mediates fumarate hydration under most conditions, FumB expression is elevated under anaerobic conditions, possibly due to its high affinity for (S)-malate. FumC is thought to compensate for the limitations of FumA and FumB during iron limitation, superoxide radical accumulation, or elevated temperatures [30, 37, 40]. Notably, FumA and FumB, despite being class I fumarases, demonstrate catalytic efficiencies that are comparable to those of the class II fumarases, which are typically faster than class I [37].

Industrially, fumarases have been utilized since the 1970s for the production of (S)-malate. Processes employing immobilized Brevibacterium flavum cells and whole-cell Corynebacterium glutamicum have demonstrated large-scale production capabilities, reaching outputs of up to 2000 tons annually [41].

For the hydration of small dicarboxylic acids, fumarases are well-established enzymes valued for their stability and industrial utility. On the other hand, large terpene substrates are converted by, for example, carotenoid and kievitone hydratases. Internal alkenes in fatty acids can be hydrated with high selectivity and efficiency by FAHs. From a synthetic point of view, there is still a gap for a more general enzyme platform for the isoprene moiety in smaller molecules and for enzymes that can selectively add water to linear monoterpenes. Although the hydration of sesquiterpenes and geraniol has been observed in several studies utilizing fungal fermentations, these activities have yet to be attributed to specific genes or enzyme sequences [42, 43, 44, 45]. This study revisits the catalytic potential of fumarases, proposing greater versatility regarding the substrate scope than was previously anticipated, and a potential to address the current gap in the hydration of monoterpenes.

2. Results and discussion

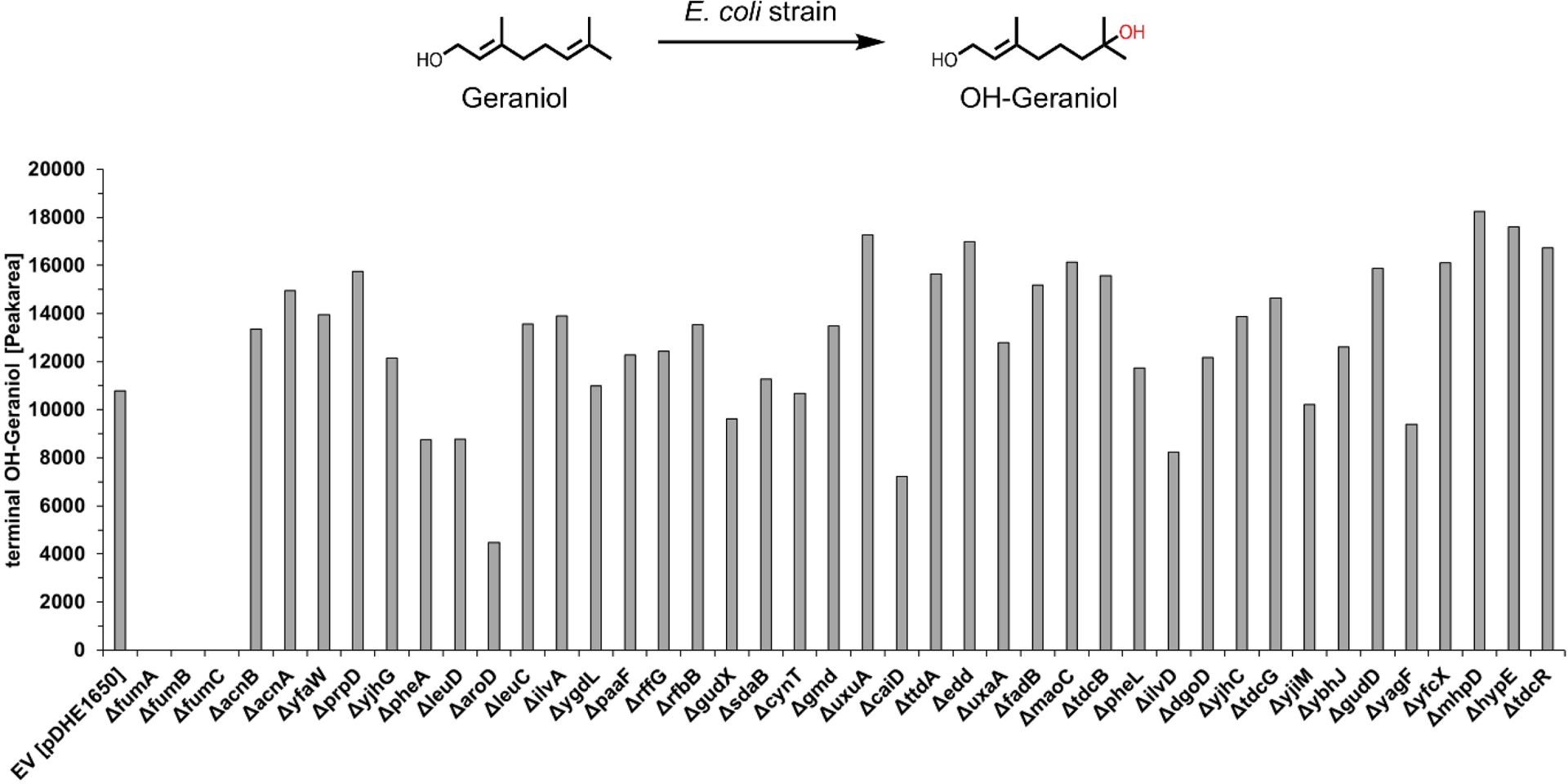

The hydration of geraniol was observed in E. coli strains ITB94, BL21(DE3), and BW25113 with and without a vector system, indicating that endogenous E. coli enzymes catalyze the reaction. The hydration does not occur spontaneously, as verified by buffer control experiments. This observation initiated an investigation to identify the specific gene responsible for this activity. To achieve this, we utilized the Keio collection, a comprehensive library of single-gene deletions in E. coli K-12 BW25113 [46]. From the library of 3985 strains, we selected strains lacking a gene annotated as hydratase-encoding (according to ecocyc.org) and tested 42 individual knockout strains. These strains were screened using a 96-deep-well plate assay coupled with GC-FID analysis. The main product of the reaction was identified through a preparative-scale reaction (see Section 4.4), followed by isolation and characterization using NMR (Figures S4 and S5). By this approach, the strain lacking the enzyme responsible for the hydration activity should be identified.

Screening the selected hydratase candidates revealed varying levels of the hydration product across the knockout strains, with the notable exception of three strains: those lacking a gene for one of the three fumarases (ΔfumA, ΔfumB, ΔfumC; Figure 3). In these knockouts, the hydration product was entirely absent, strongly suggesting that fumarase enzymes are responsible for the observed hydration of geraniol.

Screening of various knockout strains from the E. coli Keio collection to identify hydratases responsible for the conversion of geraniol. The hydration activity of different E. coli strains, lacking genes annotated as hydratases, was measured using 96-deep-well screening (1 mM substrate, 1% DMSO (v/v), 30 °C, 24 h, 300 rpm, extraction with 500 μL cyclohexane/ethylacetate 1:1).

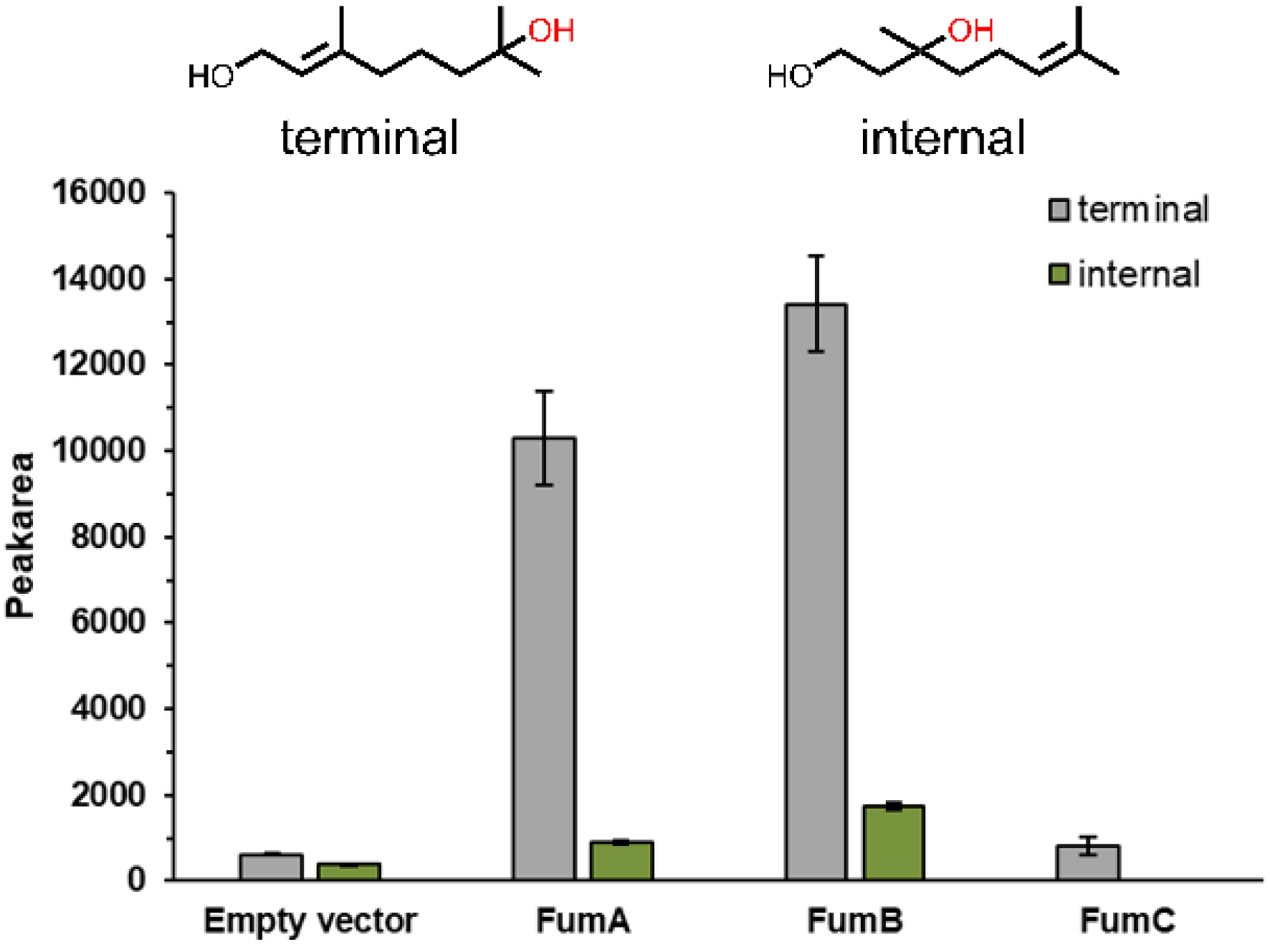

Given the complete loss of product formation in ΔfumA, ΔfumB and ΔfumC strains, we further investigated the activity of each fumarase gene individually by overexpressing them in E. coli ITB94, the strain in which the hydration activity was first discovered. For this purpose, three pDHE1650 plasmids were constructed, each harboring a gene encoding for one of the fumarases (FumA, FumB or FumC). The overexpression was confirmed in whole cells (Figure S3). Given that the strain ITB94 still contains all three fumarase genes within its genome, a background conversion was expected and observed using an empty vector control (pDHE1650 without gene insert). To optimize the reaction conditions for clear differentiation between background and overexpressed enzyme activity, experiments were conducted with 50 mg/mL cell concentration, 10 mM substrate concentration, and a reaction time of 24 h. Under these conditions, the influence of the enzymes on geraniol conversion was clearly detectable, as background activity remained sufficiently low while significant hydration activity was observed for the overexpressed enzymes. The hydration of geraniol at the terminal alkene position was considerably increased by the overexpression of FumA (17-fold) and FumB (22-fold), in comparison to the empty vector control (Figure 4). In contrast, overexpression of FumC did not noticeably alter geraniol hydration activity. Besides the terminal hydration product, we also detected an internal hydration product. Overexpression of FumA and FumB also enhanced the formation of the internal hydration product by 2.4-fold and 4.5-fold, respectively (Figure 4). With FumC overexpression, no internal hydration product was detected.

Formation of the terminal (grey) and internal (green) hydration products of geraniol with E. coli whole cells overexpressing one of the three fumarases (FumA, FumB, FumC) analyzed by GC-FID (10 mM substrate, 1% DMSO (v/v), 30 °C, 24 h, 300 rpm, extraction with 500 μL cyclohexane/ethylacetate 1:1). The values shown are average values from triplicates, the error bars show the standard deviation.

FumA and FumB catalyze the hydration of geraniol to a similar extent, while FumC does not demonstrate promiscuity with geraniol under the tested conditions. The similar behavior of FumA and FumB in geraniol hydration aligns with previous findings that these enzymes catalyze the fumarase reaction with nearly identical kinetic parameters [37, 47]. This is also reasonable in view of the fact that they share 90% sequence similarity [39]. Notably, FumA and FumB exhibited regioselectivity for terminal hydration, with FumA achieving an 11.3-fold higher formation of the terminal hydration product and FumB a 7.8-fold higher formation of the terminal product. Slight differences between FumA and FumB have been reported before for certain substrates, such as D-tartrate, which may reflect their physiological specialization, with FumA being more relevant under aerobic and FumB under anaerobic conditions [40].

In addition to the hydration of geraniol, the reduction of geraniol to citronellol was also observed during the experiments. Among the overexpressed fumarases, cells overexpressing FumB showed an increase in geraniol reduction, while overexpression of FumA had little effect, and overexpression of FumC resulted in decreased citronellol formation (Figure S2). These results, especially those with FumC, suggest an indirect link between fumarase overexpression and geraniol reduction, emphasizing the interconnected nature of metabolic networks. Further investigation into the specific enzymes responsible for this reduction, similar to the study presented here, could elucidate the underlying mechanisms and expand our understanding of the metabolic context surrounding these reactions.

3. Conclusion

Our findings demonstrate that E. coli fumarases might exhibit a broader substrate promiscuity than previously recognized. The hydration of the terpenoid geraniol, observed with overexpression of FumA and FumB, suggests an extension of the substrate range for these enzymes, which are considered highly specific for fumarate and only a few derivatives [33, 34]. While the hydration of geraniol has been previously reported using the marine fungus Hypocrea sp. MFAac46-2 in a three-day fermentation [42], our study represents the first direct linkage of this activity to specific genes and their enzyme sequences. The unexpected substrate conversion by these class I fumarases, despite their more thermolabile and oxygen-sensitive nature compared to class II fumarases, may encourage a reconsideration of class I fumarases as valuable tools in biocatalysis. Furthermore, this discovery suggests that fumarases may contribute to side reactions involving terpenes and alkenes in fermentative processes. To the best of our knowledge, fumarases have not been tested for activity towards terpenes before. And since fumarases are very fast-acting enzymes on their natural substrates (kcat of 3100 s−1) [37], the assay times used were often in the range of seconds and minutes, which may be a reason why much slower promiscuous reactions are not detected. The possibility of using fumarases in terpene hydration and related reactions highlights their potential as highly efficient biocatalysts, which are particularly valued for their 100% atom economy—a key attribute in sustainable chemical processes. These results underscore the promise of hydratases and fumarases as versatile tools and encourage deeper exploration of their applications in biocatalysis and green chemistry.

4. Experimental section

4.1. Materials

All chemicals and solvents were purchased from different suppliers (Alfa Aesar, Carl Roth GmbH, Enamine, Macherey-Nagel, Merck, Sigma-Aldrich, Thermo Fisher, VWR) without further purification. Phusion High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase and DpnI were purchased from New England Biolabs.

4.2. Screening of Keio collection (knockout strains)

4.2.1. Expression

The investigation of the Keio Collection took place in 96-deep-well plates (DWPs). Therefore, overnight cultures were prepared in 96-DWPs by inoculating 1 mL of lysogeny broth (LB) medium containing 30 μg/mL kanamycin (knockouts) or 150 μg/mL ampicillin (empty vector) per well, with glycerol stocks of the knockout variants and empty vector controls. The plates were incubated at 37 °C and 300 rpm for 16 h in an orbital shaker. The main cultures in 96-DWPs were set up using TB-media containing either 30 μg/mL kanamycin (knockouts) or 150 μg/mL ampicillin (empty vector), inoculated with 1% overnight culture, and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C and 300 rpm in the orbital shaker. After 24 h of incubation, the plates were centrifuged at 4000 g for 20 min at 4 °C, and the harvested cells were immediately used for biotransformation experiments.

4.2.2. Biotransformation (screening)

For biotransformations, the fresh cells were resuspended in 495 μL KPi-buffer (50 mM, pH 7.0) and 5 μL of geraniol substrate stock (100 mM substrate in DMSO; final concentration 1 mM) were added and incubated for 24 h at 30 °C and 300 rpm. The reactions were stopped by adding 500 μL of cyclohexane/ethylacetate 1:1. Extraction took place by shaking and inverting with subsequent phase separation by centrifugation at 4000 g for 10 min at room temperature. Finally, 200 μL of the organic phase was transferred into autosampler glass vials with inlets for GC-FID analysis.

4.3. Cloning and biotransformations of fumarases

4.3.1. Cloning of FumA, FumB and FumC in pDHE1650 vector

The genes for the fumarase types FumA, FumB and FumC were successfully integrated into the pDHE1650 vector using Gibson Assembly [48]. For PCR, the standard protocol of Phusion® High Fidelity Polymerase was used. The PCR products were digested using DpnI (1 μL DpnI for 25 μL PCR product, 4 h at 37 °C), purified and transformed via heat shock into E. coli XL1-Blue and after sequencing into ITB94 (derivate of commercial strain TG1, with L-rhamnose-isomerase knockout and two unspecific ADH—ΔyahK and ΔyjgB—knockouts).

4.3.2. Expression

Single colonies were inoculated in 5 mL overnight cultures (LB-medium with ampicillin 150 μg/mL) and incubated at 37 °C and 180 rpm. Main cultures were set up using terrific broth (TB) medium containing 150 μg/mL ampicillin and 0.5 g/L L-rhamnose (500 mL medium in 2 L Erlenmeyer flasks), inoculated with 1% overnight culture and incubated at 30 °C and 180 rpm for 24 h. Cells were harvested at 10,000 g for 30 min at 4 °C and immediately used for biotransformation experiments.

4.3.3. Biotransformation

To investigate the functionality and differences in fumarase biotransformation, experiments were conducted after expression of the cells at a 500 μL scale in 2 mL glass vials. The experimental setup included 495 μL of 50 mg/mL whole-cell suspension (FumA, B, C, or empty vector, in 50 mM NaPi, pH 7.4) mixed with 5 μL of geraniol stock (1 M in DMSO, final substrate concentration: 10 mM). The buffer control was prepared with 495 μL NaPi (50 mM, pH 7.4) and 5 μL of geraniol stock (final concentration 10 mM, in DMSO). Each reaction was performed in triplicates and incubated at 30 °C for 24 h with shaking at 300 rpm. The reaction mixtures were extracted with 500 μL of cyclohexane/ethylacetate 1:1, vortexed, and centrifuged at 4000 g at rt for 5 min. Subsequently, 200 μL of the organic phase was transferred into autosampler glass vials with inlets for further GC analysis.

4.4. Semi-preparative biotransformation

Semi-preparative biotransformations took place in 100 mL shot flasks with 100 mL of reaction volume. Therefore, cells with empty vector were cultivated as described in Section 4.3. Fresh harvested cells were resuspended in KPi-buffer (50 mM, pH 7.0) to a cell concentration of 40 mgcww/mL and 10 mM substrate (geraniol) was added. The biotransformation was incubated for 5d at 30 °C at 200 rpm in an orbital shaker. The reaction was stopped by extracting three times with cyclohexane/ethylacetate 1:1 (in total 1 L solvent) and the pooled organic phase was concentrated in vacuo. The crude product was then dissolved in CH2Cl2 and purified by column chromatography on silica gel 60M 0.04–0.063 mm and with cyclohexane/ethylacetate 8:1 as the eluent. The determination of the product structures was achieved by NMR (additional figures in the SI).

4.4.1. Terminal hydrated OH-geraniol

Isolated product: 97.4 mg of yellow clear oil (56% isolated yield):

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) 𝛿 = 5.13 (t, 3 JH,H = 7.1 Hz, 1H), 4.12 (d, 3 JH,H = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 1.69 (s, 3H), 1.25 (s, 6H) ppm.

13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) 𝛿 = 132.1, 124.2, 74.0, 59.9, 42.4, 41.7, 29.7 (2C), 21.1, 17.7 ppm.

The NMR data obtained are consistent with previously reported values [49].

4.4.2. Internal hydrated OH-geraniol

Isolated product: 6.47 mg of yellow clear oil (3.7% isolated yield):

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) 𝛿 = 5.12 (t, 3 JH,H = 7.0 Hz, 1H), 3.96 (m, 2H), 2.05 (m, 2H), 1.83 (ddd, 3 JH,H = 14.3, 7.0, 5.0 Hz, 1H), 1.69 (s, 4H), 1.63 (s, 3H), 1.54 (m, 2H), 1.26 (s, 3H) ppm.

13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) 𝛿 = 132.6, 124.1, 71.3, 61.3, 42.2, 39.7, 26.9, 25.7, 22.7, 17.7 ppm.

The NMR data obtained are consistent with previously reported values [50].

4.5. Gas chromatography

To analyze the products from biotransformations, gas chromatography (GC) was used. Analysis was performed on a Shimadzu GC2010 instrument using a ZB-5 column (Zebron-Phenomenex, 30 m × 0.25 mm, 0.25 μm film) and hydrogen as carrier gas. The GC was equipped with a flame ionization detector (FID) set to 335 °C. Injections of 1 μL injection volume were performed with an inlet temperature of 260 °C in split mode (split 1:10). The oven temperature started at 110 °C with a gradient of 10 °C per min up to 300 °C, holding the end temperature for 1 min.

Declaration of interests

The authors do not work for, advise, own shares in, or receive funds from any organization that could benefit from this article, and have declared no affiliations other than their research organizations.

Funding

This project has received funding from the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) - 031B1343A.

Acknowledgements

We thank Andreas Schneider for assistance with the evaluation of NMR spectra and Nicolas D. Travnicek for assistance with chromatographic isolation of the products from preparative biotransformations.

Supplementary data

Supporting information for this article is available on the journal’s website under https://doi.org/10.5802/crchim.407 or from the author.

CC-BY 4.0

CC-BY 4.0