1. Introduction

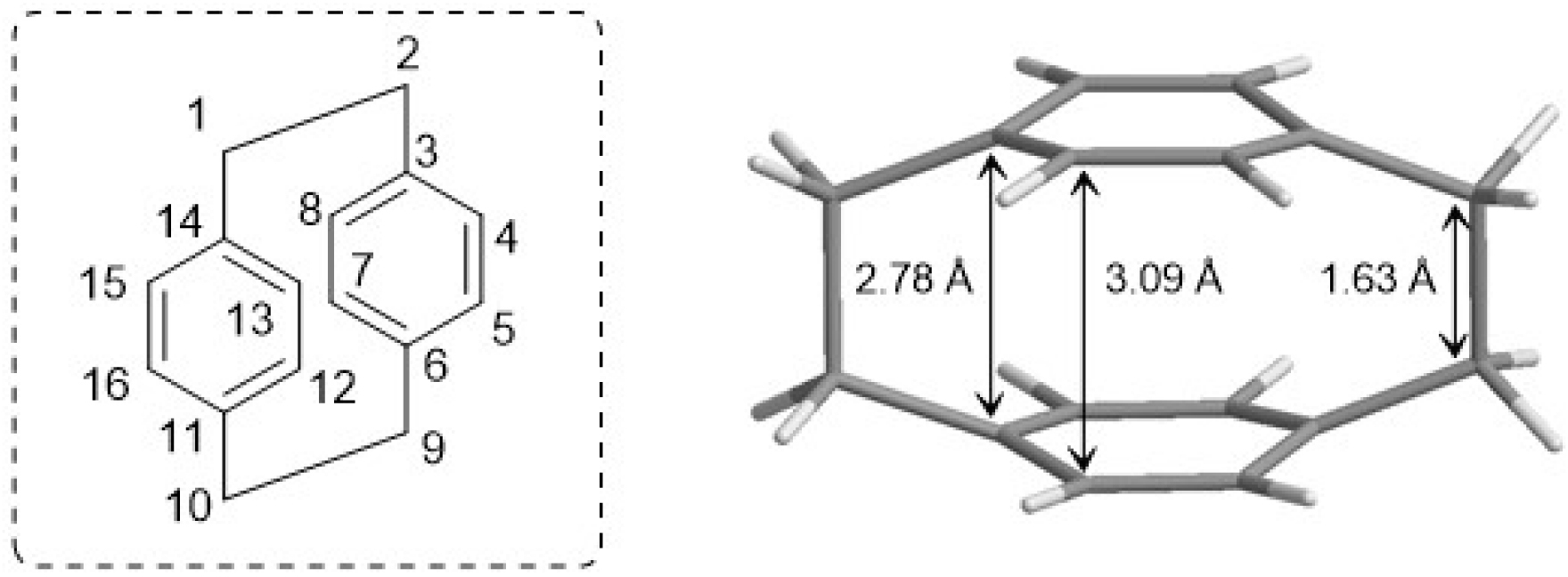

[2.2]Paracyclophane (pCp) is the smallest known member of the [n.n]cyclophane family. This molecule was serendipitously discovered and first isolated in 1949 by Brown and Farthing as an unexpected byproduct of the gas-phase pyrolysis of para-xylene [1]. X-ray diffraction analysis revealed that pCp consists of two benzene rings, commonly referred to as decks, arranged in a cofacial orientation and connected at the para positions by two ethylene bridges [2]. This molecular architecture forces the decks into an unusual boat-like conformation (Figure 1), in which the bridgehead carbon atoms are displaced out of the plane defined by the remaining trigonal carbon atoms. Consequently, the distance between the carbon atoms bearing the ethylene bridges is shorter than the overall inter-ring separation (2.78 Å versus 3.09 Å, respectively, Figure 1).

Structure of [2.2]paracyclophane (pCp).

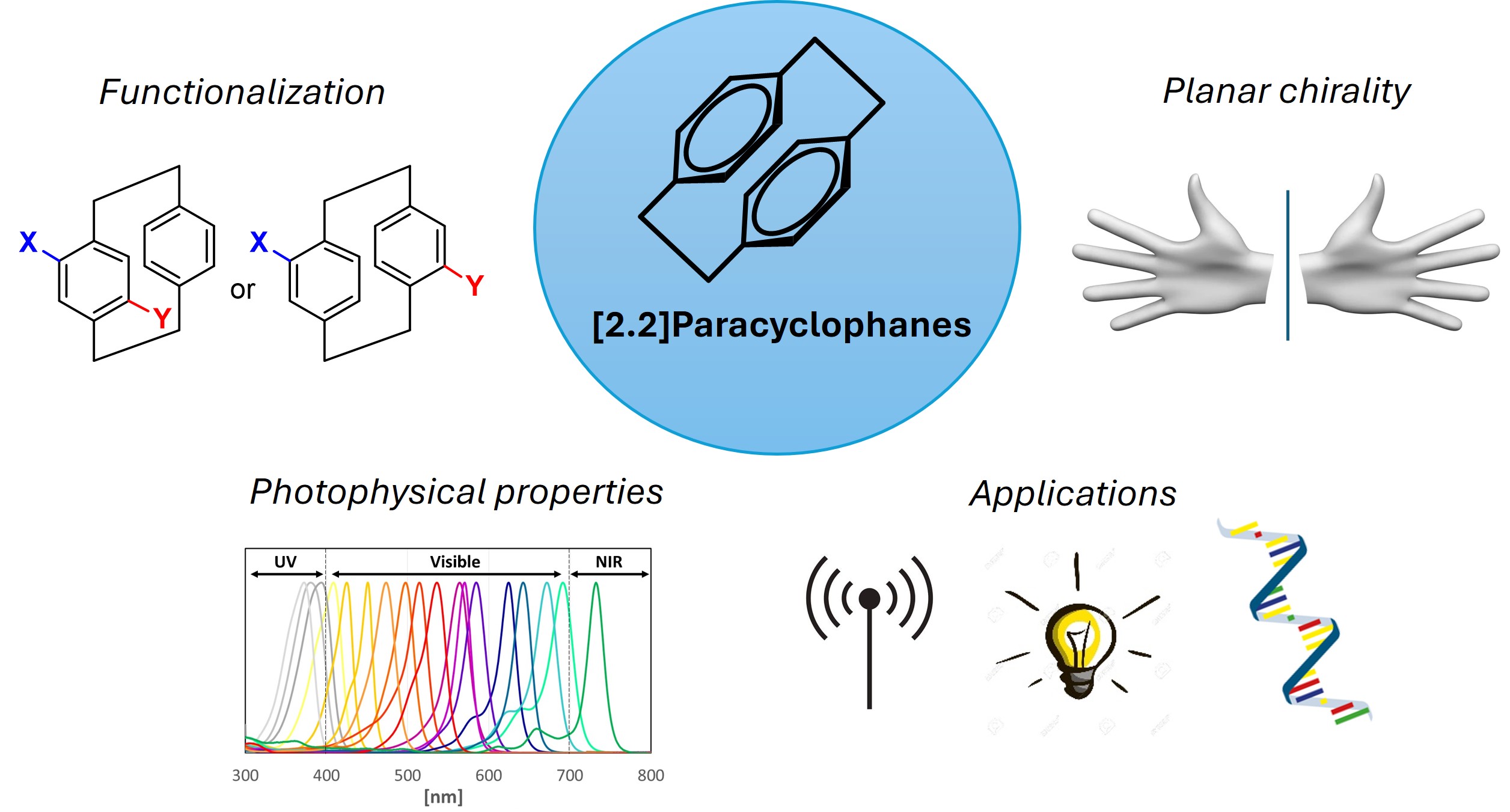

These structural characteristics have a significant impact on the electronic distribution and chemical reactivity of the molecule, positioning pCp as a valuable scaffold for the design of novel aromatic compounds with a distinctive three-dimensional framework. Accordingly, significant research efforts have been dedicated to the synthesis and functionalization of pCp, as well as the modulation of its physicochemical properties and the exploration of its potential across various scientific domains [3].

In this account, we report our contributions to the chemistry of pCps, at first by placing our research in its broader context and outlining the strategies that we have developed to selectively functionalize the aromatic rings of commercially available pCp. Our methods for controlling the planar chirality inherent to these unique systems are then discussed. Finally, the synthesis of novel families of three-dimensional luminophores derived from pCp is described, and their applications across different research areas are discussed, including photocatalysis, coordination chemistry, and chemical biology.

2. Tailoring the aromatic decks of [2.2]paracyclophane

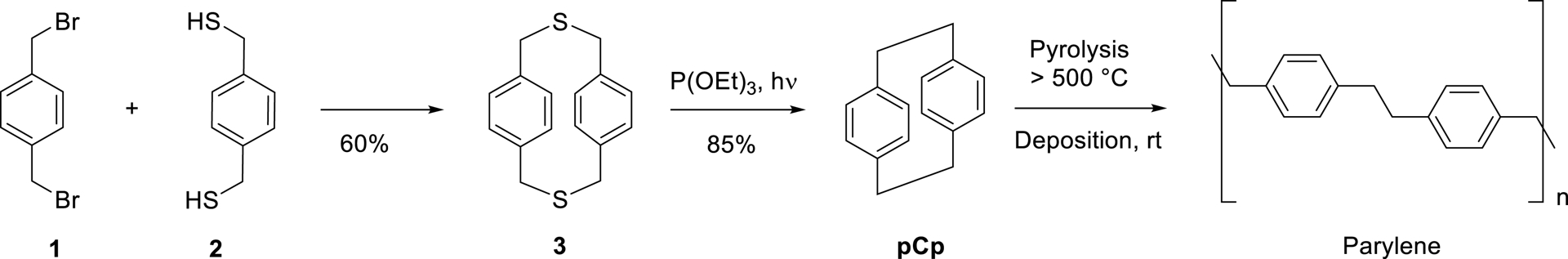

Since its discovery, numerous synthetic strategies have been developed to try and access pCp in an efficient manner. In addition to the industrial synthesis, which relies on the Hofmann elimination of p-methylbenzyl trimethylammonium hydroxide [4], the method reported by Brink in 1975 remains the most widely adopted and highest-yielding approach at the laboratory scale [5]. This approach involves the coupling of 1,4-bis(bromomethyl)benzene 1 with 1,4-bis(mercaptomethyl)-benzene 2 to produce dithia[3.3]paracyclophane 3, followed by photochemical desulfurization to yield pCp in 51% overall yield (Scheme 1). This robust and reliable method has since enabled the synthesis of a broad range of pCp derivatives [6, 7, 8].

Synthesis and polymerization of [2.2]paracyclophane.

[2.2]Paracyclophanes are remarkably stable toward acids, bases, oxidants, or light, and retain their structural integrity up to 200 °C. Above this temperature, homolytic cleavage of the ethylene bridges occurs, leading to ring opening of the pCp core. This thermal behavior has been widely exploited in materials science, particularly for polymer production via chemical vapor deposition (CVD) processes [9, 10, 11, 12]. For example, unsubstituted pCp is a key precursor in the synthesis of parylene (Scheme 1) [13], an aromatic polymer extensively used as a protective coating in electronics, optics, and biomedical devices.

Owing to its widespread industrial applications, pCp is now commercially available at low cost. As a result, functionalized pCp derivatives are nowadays most easily prepared via direct functionalization of the parent compound, rather than through de novo synthesis of substituted analogues.

Each aromatic ring of the pCp scaffold offers four accessible positions, allowing up to eight possible sites for derivatization. Monofunctionalization is typically achieved through electrophilic aromatic substitution, enabling the introduction of diverse functions such as bromine atoms, formyl, nitro, or ester motifs. Alternatively, halogen–lithium exchange from brominated precursors followed by trapping with suitable electrophiles allows the incorporation of a broader array of functional groups, including amines, hydroxyls, azides, thiols, carboxylic acids, and phosphines [14]. More recently, direct C–H activation strategies have also emerged as effective tools for regioselective modification of the pCp core [15].

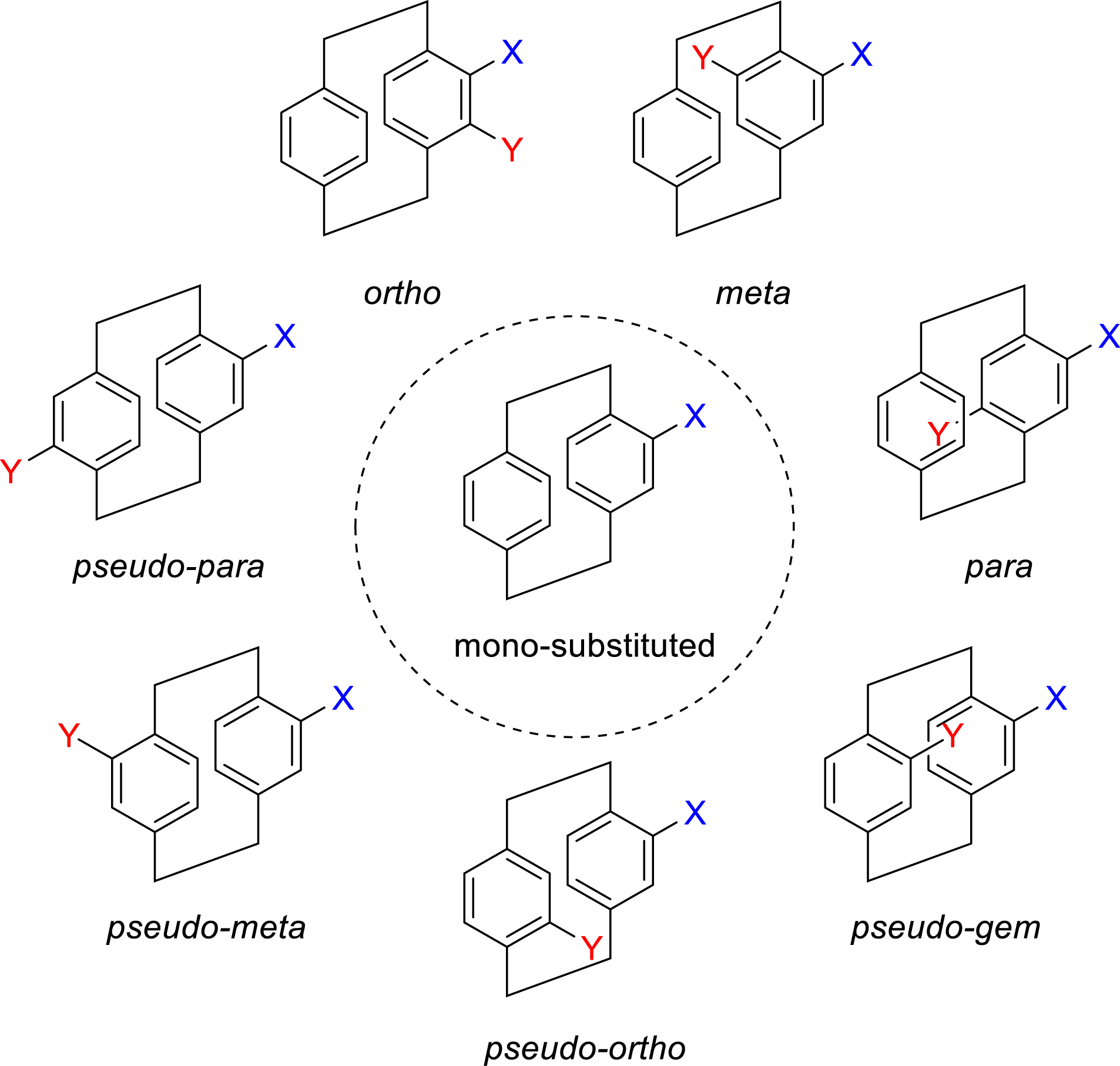

From monosubstituted intermediates, various disubstituted pCps can be easily prepared (Figure 2). These are typically classified according to their substitution pattern: ortho, meta, or para when both substituents are on the same aromatic ring; and pseudo-gem, pseudo-ortho, pseudo-meta, or pseudo-para when the substituents are located on both decks.

Substitution patterns and nomenclature of pCps.

Higher substituted derivatives (tri- and tetrafunctionalized pCps) are generally synthesized via sequential electrophilic substitutions on di-substituted precursors [16]. However, systems bearing more than four substituents are highly strained and remain uncommon in the literature [17].

In certain cases, the reactivity of the aromatic units in pCps can pose notable synthetic challenges due to through-space electronic delocalization between the closely positioned π systems. Interestingly, reactivity patterns resembling those of isolated double bonds have been observed in some cases [18, 19]. Moreover, the introduction of substituents on one deck can significantly influence the electronic distribution across the molecule, thereby activating or deactivating specific positions on the opposite ring. For example, the introduction of electron-withdrawing groups can direct selective functionalization to the pseudo-geminal position, an effect well known and extensively exploited in [2.2]paracyclophane chemistry [20, 21].

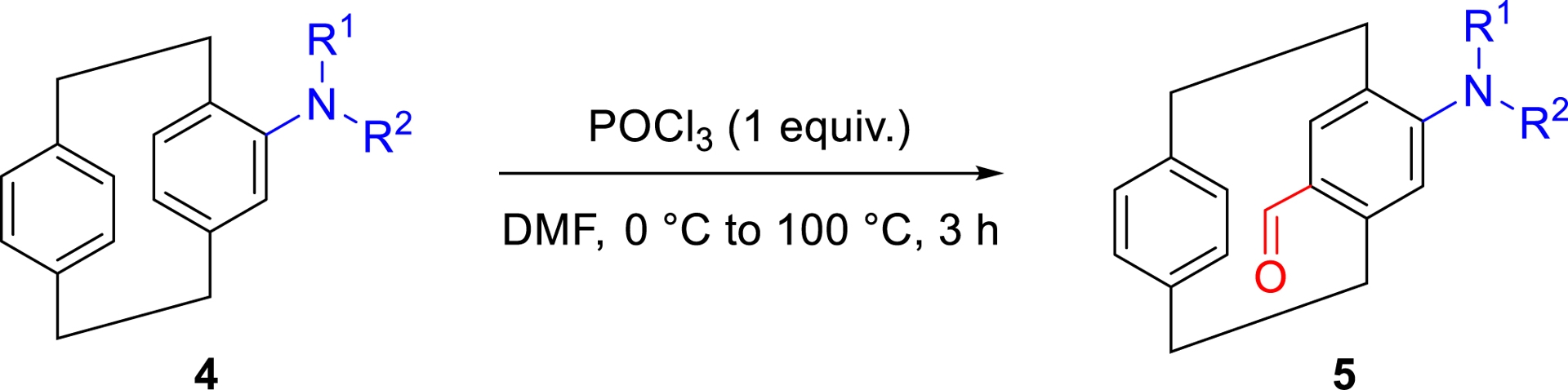

Despite significant progress, the selective introduction of multiple substituents onto a single aromatic ring of pCp remains a synthetic challenge. In our studies, we have developed an efficient and regioselective approach for synthesizing para-disubstituted pCps in a limited number of steps and with good overall yields. This strategy relies on a Vilsmeier–Haack formylation of various 4-amino[2.2]paracyclophane derivatives (4, Table 1), enabling the installation of a formyl group opposite to the existing electron-donating substituent.

| Entry | Product | R1 | R2 | Yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5a | Me | Me | 90 |

| 2 | 5b | Bn | Bn | 77 |

| 3 | 5c | H | Bn | 72 |

| 4 | 5d | Allyl | Allyl | 50 |

| 5 | 5e | H | Fmoc | 42 |

The transformation is performed using POCl3 (1 equiv.) in the presence of DMF, with the reaction mixture gradually heated from 0 to 100 °C over 3 h. These conditions exhibit broad substrate tolerance, accommodating tertiary and secondary amines bearing alkyl, allyl, or benzyl substituents on the nitrogen atom, as well as derivatives featuring mildly electron-withdrawing groups, such as a 9-fluorenylmethyloxycarbonyl (Fmoc) motif (Table 1). This method provides access to a range of functionalized aldehydes in a practical and scalable manner, generating versatile intermediates for the construction of more elaborate molecular architectures based on the pCp core [22], as detailed in the following sections of this account.

3. Controlling planar chirality in [2.2]paracyclophanes

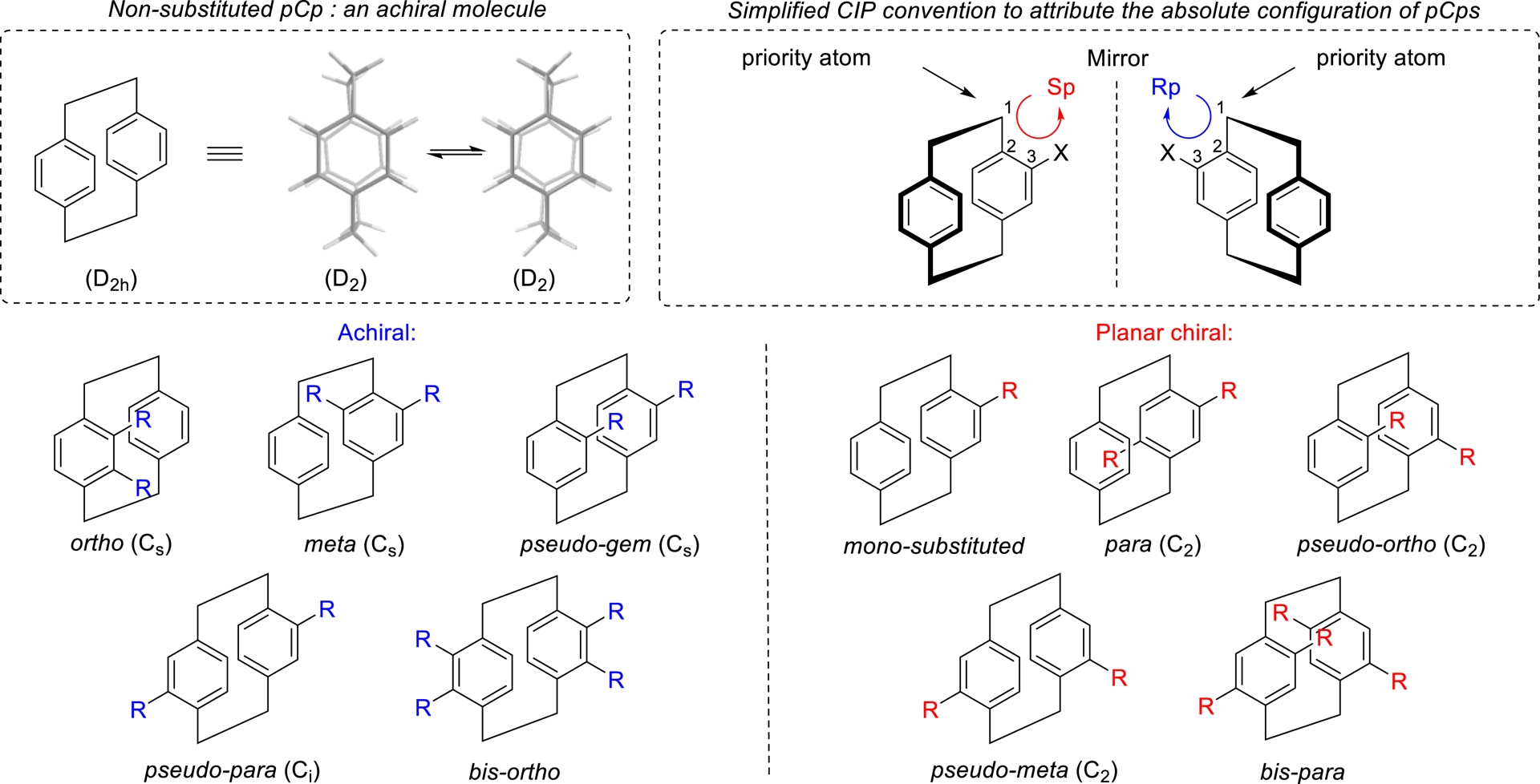

Extensive efforts have been devoted to the investigation and rationalization of the geometry of pCps. For many years, it was believed that the unsubstituted pCp adopted a fully eclipsed conformation with D2h symmetry. However, subsequent experimental and theoretical studies have shown that, at very low temperatures, the molecule favors a staggered conformation with D2 symmetry, characterized by a torsional angle between 6 and 9°. As a result, the D2h structure is now considered as a transition state between two enantiomeric D2 conformers (Figure 3). Despite this, the unsubstituted pCp remains achiral at room temperature due to the rapid interconversion between its enantiomeric conformations [23, 24, 25].

Achiral and planar chiral pCps.

Substituted pCps can exhibit planar chirality due to their rigid, strained structure, which prevents rotation of the aryl groups around their axes. Monosubstituted pCps are inherently nonsymmetrical, but disubstituted derivatives may or may not be chiral, depending on the nature and position of their substituents (Figure 3). Indeed, ortho, meta, pseudo-gem, and pseudo-para derivatives are achiral when both substituents are identical.

On the contrary, para, pseudo-ortho, and pseudo-meta pCps display planar chirality even when bearing the same substituents. A similar trend is observed for tetra-substituted derivatives (Figure 3) [14].

To assign the absolute configuration of pCps, specific Cahn–Ingold–Prelog rules (CIP conventions) [26] must be followed. The less substituted aromatic ring of the pCp core is positioned toward the front of the molecule, and the priority atom is identified as the carbon of the ethylene bridge bonded to the aromatic ring at the position nearest the highest-priority substituent. The configuration is assigned by numbering the ring carbons beginning at the priority atom, moving sequentially toward the highest priority substituent, and including the aromatic quaternary carbon attached to the ethylene bridge. The direction of numbering (clockwise or counterclockwise) determines the Rp or Sp configuration, respectively (Figure 3).

Planar chirality in pCps was first identified by Gram and Allinger in 1955 [27]. Early research in this domain focused on synthesizing monosubstituted pCps and determining their absolute configuration. Since the 1990s, chiral pCps have become valuable ligands in asymmetric catalysis [28] and, more recently, key components in the development of circularly polarized light-emitting materials [29, 30]. However, large-scale synthesis of polysubstituted pCps with controlled chirality remains a significant challenge, which still considerably limits their broader applications.

The synthesis of structurally complex enantiopure pCps typically involves the functionalization of simpler optically active intermediates. Over the years, various strategies have been developed to obtain such compounds in an efficient manner. Techniques like high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) on chiral stationary phases are commonly used for enantiomer separation, although they require costly equipment and large volumes of solvents. Classical resolution methods, which rely on forming diastereoisomeric products using stoichiometric amounts of chiral resolving agents, are also frequently employed to generate enantioenriched pCps. However, these approaches often involve multi-step syntheses (i.e., formation of the diastereomers, separation, and regeneration of the initial pCps), which are time-consuming [31].

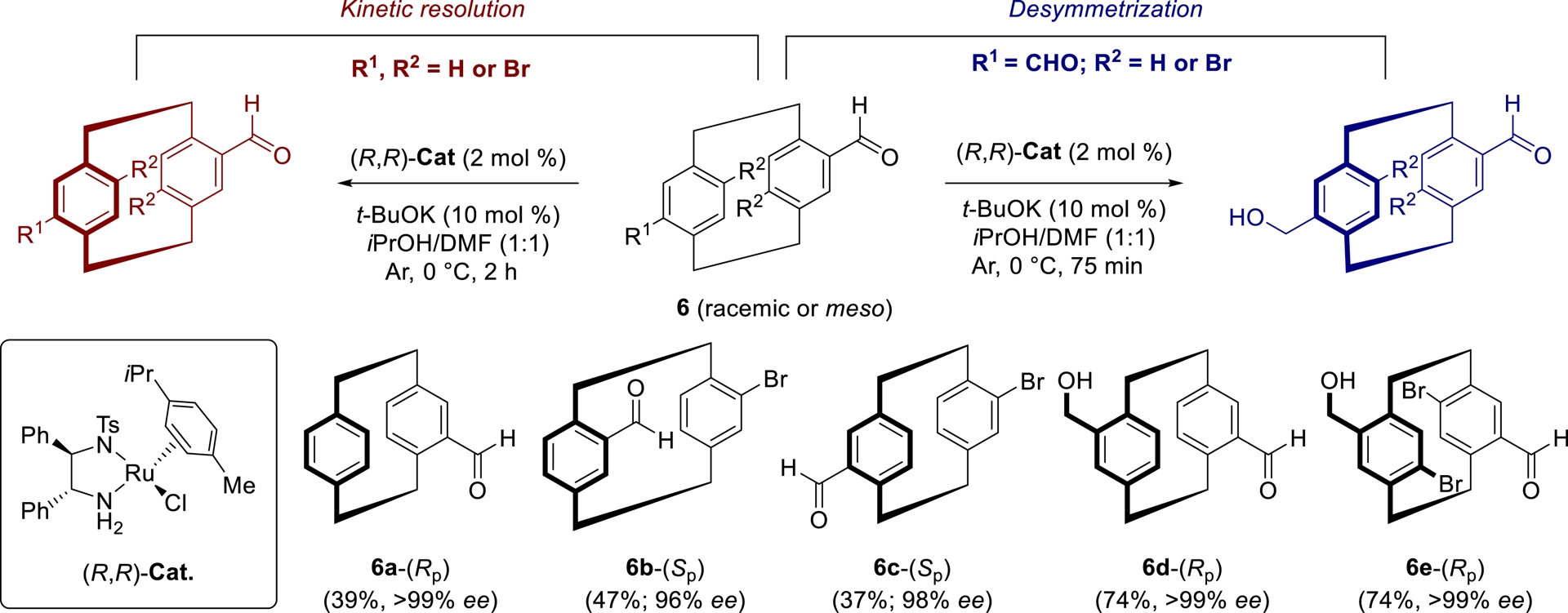

In our studies, we have investigated kinetic resolution and desymmetrization strategies as effective alternatives to traditional methods for accessing optically active pCps. Kinetic resolution (KR) constitutes a powerful approach wherein racemates undergo asymmetric transformations in the presence of a chiral catalyst, with the two enantiomers reacting at different rates. Ideally, at 50% conversion, one enantiomer is recovered as unreacted starting material, while the other one is obtained as the product. In contrast, desymmetrization of meso derivatives enables the generation of enantiopure compounds under similar catalytic conditions in yields up to 100%, by differentiating prochiral sites within an achiral molecule.

Starting from racemic aldehydes or centrosymmetric meso dialdehydes derived from pCp, we employed asymmetric transfer hydrogenations (ATH) as key transformations to control planar chirality [16, 32, 33]. After optimizing the reaction conditions, enantioselective reductions were successfully carried out using the commercially available Noyori’s catalyst RuCl(p-cymene)[(R,R)-TsDPEN] ((R,R)-Cat, 1 mol%) in a 1:1 iPrOH/DMF mixture at 0 °C, with t-BuOK (5 mol%) as the base. These reactions, which are operationally simple and easy to implement, delivered a wide range of optically active products in short times (Scheme 2).

Kinetic resolution and desymmetrization of aldehydes derived from [2.2]paracyclophanes.

The resulting molecules possess diverse substituents, including carbonyl or hydroxyl groups, and halogen atoms, on each aromatic ring of the pCp core, thereby enabling further functionalization through a variety of orthogonal transformations such as condensations, nucleophilic substitutions, Grignard additions, transition-metal-catalyzed couplings, and olefination reactions. Enantiopure pCp-based aldehydes are thus now routinely prepared in our laboratory on multigram scales, serving as valuable key intermediates.

Notably, following our work, there has been a renewed interest in controlling the planar chirality of [2.2]paracyclophanes through catalytic chemical methods, resulting in a number of compelling contributions to the field [34, 35, 36, 37, 38]. Among the various strategies developed in this area, our approach has proven both viable and competitive, and it has been successfully employed by other research teams worldwide [39].

4. Modulating the photophysical properties of [2.2]paracyclophanes

[2.2]Paracyclophanes are known to exhibit unique photophysical properties arising from electronic conjugation between their two aromatic rings, aided by both through-bond and through-space interactions. Indeed, unsubstituted pCp displays a distinctive UV–visible absorption spectrum, characterized by maxima at 225, 244, 286, and 302 nm [40, 41]. The absorption band at the longest wavelength, commonly referred to as the cyclophane band, emerges in a spectral region that is atypical for standard benzene derivatives, such as xylenes. Furthermore, the molecule exhibits a broad fluorescence emission band centered around 356 nm. These characteristics have led to the widespread use of pCp as a core structure in the design of three-dimensional organic luminophores.

Pioneering studies have focused on the development of various systems that mimic excimers, transient dimers typically observed via fluorescence spectroscopy. In contrast to true excimers, which exist solely in the excited state, pCp-based analogues are stable in the ground state, making them particularly well-suited as model compounds for photophysical investigations. Notably, a variety of stilbene dimers incorporating the pCp scaffold have been isolated and thoroughly characterized [42, 43, 44]. Furthermore, di- and tetrasubstituted pCp derivatives bearing both electron-donating and electron-withdrawing groups have been designed to probe through-space charge-transfer delocalization [45]. All these systems offer valuable insight into electronic communication between stacked aromatic units within the distinctive three-dimensional architecture of the pCp framework.

More recently, numerous studies have demonstrated that the synergistic interplay between planar chirality and the distinctive spectroscopic behavior of pCps can be effectively exploited for the development of advanced circularly polarized luminescence (CPL) emitters. Research on CPL active compounds has gained momentum, driven by their promising applications in advanced optoelectronic technologies, such as 3D displays, optical data storage, and bioimaging [46]. Nevertheless, the rational design of organic luminophores that combine high emission efficiency with strong chiroptical activity remains a major challenge, spurring ongoing innovation in molecular engineering.

In this context, helicene-like structures featuring a pCp core have been synthesized and extensively investigated for their CPL properties [47]. Additionally, a variety of second-order molecular architectures, such as V-, N-, M-, triangle-, propeller-, and X-shaped frameworks, have been constructed from pCp units [48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55]. These structurally complex compounds exhibit remarkable optical properties, including high molar extinction coefficients (𝜀), strong fluorescence with significant quantum yields (Φ), and impressive dissymmetry factors [56] in both absorption (gabs) and emission (glum). Such attributes render them promising candidates for the development of advanced functional materials in the field of chiral photonics.

As a complementary strategy to modulate the (chir)optical properties of pCps we explored the possibility of expanding the pCp aromatic framework to access functionalized polycyclic (hetero)aromatic derivatives—three-dimensional analogues of classical aromatic dyes such as naphthalenes, coumarins, and cyanines [57]. This approach has led to the development of chiral luminophores with more compact molecular structures and enhanced solubility, offering key advantages for solution-phase applications, including asymmetric catalysis, supramolecular recognition, and chiral sensing in complex environments.

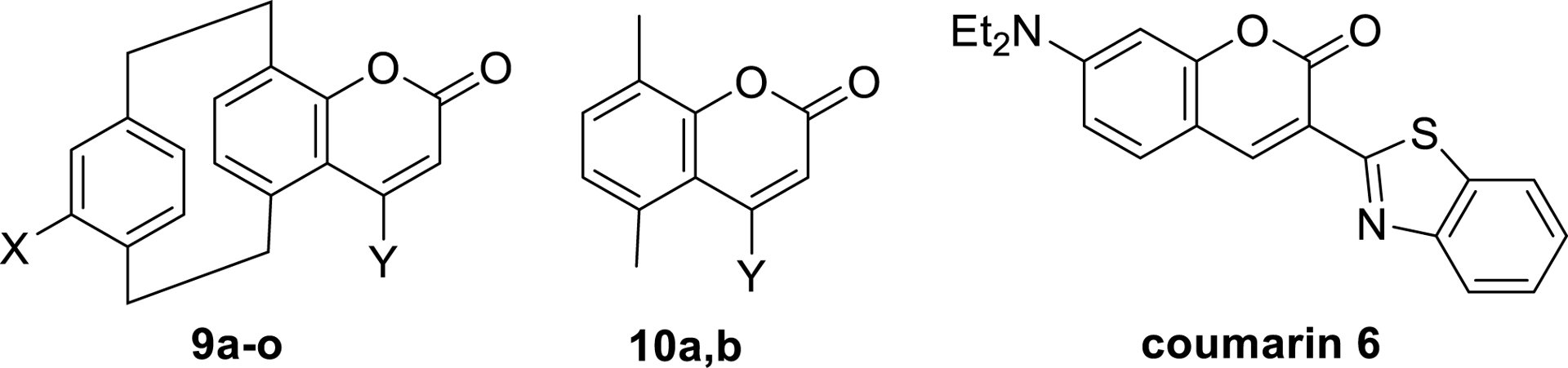

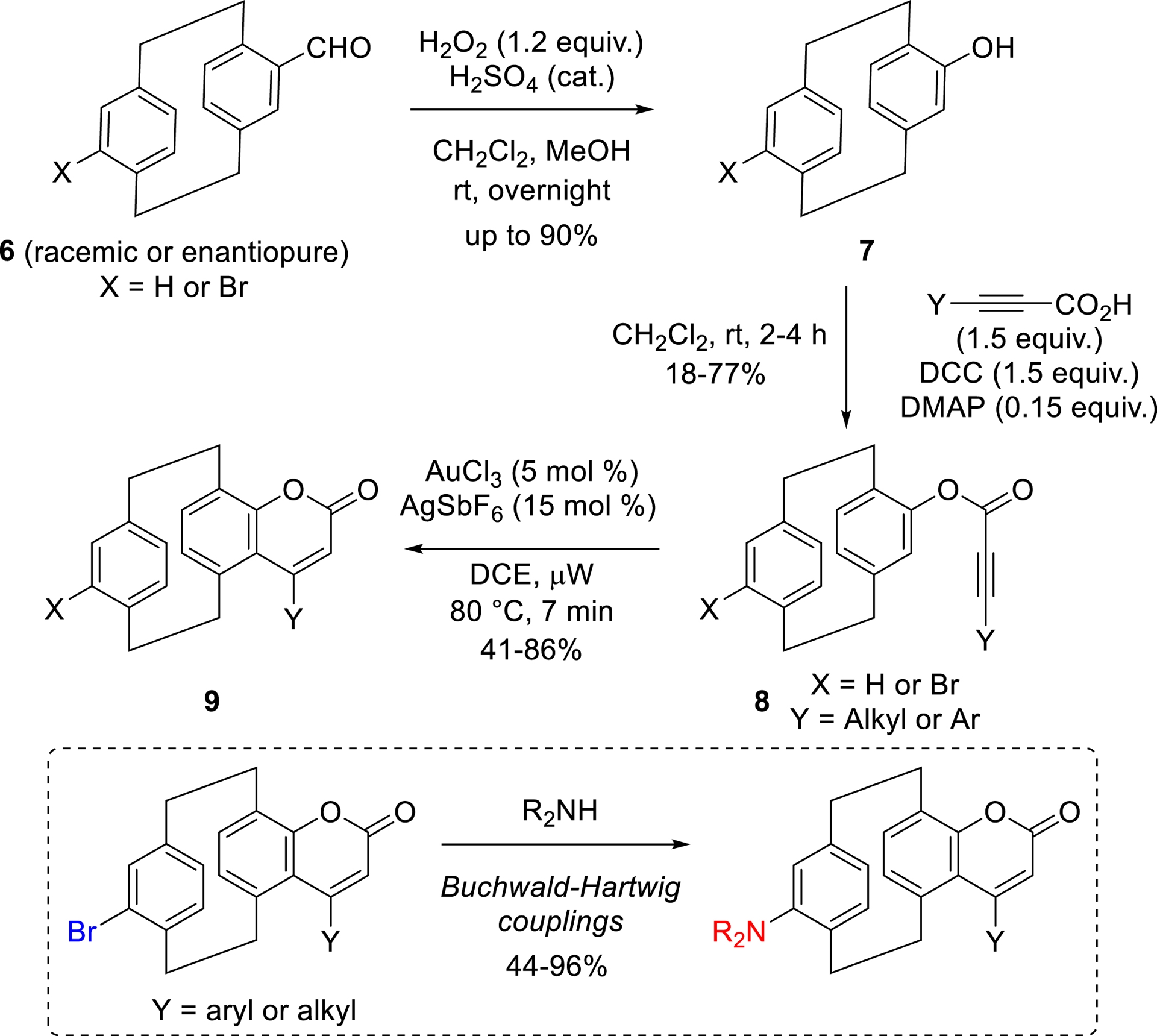

All the new families of 3D luminescent compounds that we developed [57] were synthesized in just a few steps, starting from aldehyde intermediates, the chirality of which can be easily controlled using the methods described earlier in this article. For example, three-dimensional coumarin dyes were synthesized in three steps, beginning with Dakin oxidation, conducted using H2O2 and catalytic amount of H2SO4 in a CH2Cl2/MeOH mixture, to form 4-hydroxy[2.2]paracyclophanes 7 in up to 90% yield. These molecules were then esterified with various propiolic acid derivatives under classical conditions (DCC and DMAP cat. in CH2Cl2). The resulting esters 8 were subjected to cyclization promoted by gold- and silver-based catalysts in 1,2-dichloroethane under microwave irradiation at 80 °C, yielding the desired coumarin core 9 (Scheme 3). In a final diversification step, starting from brominated compounds, Buchwald–Hartwig couplings were employed to introduce electron-donating amino groups on the pCp scaffold [58].

Synthesis of pCp-based 3D coumarins.

The impact of the pCp motif and its characteristic “phane” interactions on the spectroscopic properties of the synthesized coumarins was investigated using unpolarized UV–visible absorption and fluorescence spectroscopy. Overall, the three-dimensional dyes exhibited bathochromic shifts in both absorption and emission spectra compared to analogous planar structures (Table 2). Interestingly, the absorption maxima of the pCp-based coumarins remain hypsochromically shifted relative to those of planar commercial dyes such as coumarin 6, which possess a strong intramolecular charge-transfer character (Table 2). The luminescence properties of the 3D coumarins, which spanned the blue-to-green region of the electromagnetic spectrum, were significantly influenced by the substitution pattern on the out-of-plane aromatic ring of the pCp core. In particular, the introduction of halogen atoms induced hypsochromic shifts in the emission profiles compared to their unsubstituted counterparts (Table 2, entries 5 and 6 versus entries 1 and 2). Conversely, amino-substituted derivatives bearing electron-donating groups exhibited pronounced bathochromic shifts in their emission maxima (Table 2, entry 13 versus entry 1), highlighting the effective modulation of luminescent properties through electronic effects. These findings clearly demonstrate that precise control over the photophysical behavior of these compounds can be achieved by modulating both the nature and spatial arrangement of substituents around the three-dimensional pCp framework.

| Entry | Compound | X, Y | ${\lambda }_{\mathrm{max}}^{\mathrm{abs}}$ (nm) | $\lambda _{\mathrm{max}}^{\mathrm{em}}$ (nm)d |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1a | 9a | H, Ph | 265, 300, 330 | 460 |

| 2a | 9b | H, Me | 301, 319 | 435 |

| 3a | 9c | H, iPr | 300, 320 | 432 |

| 4a | 9d | H, H | 304, 320 | 445 |

| 5a | 9e | Br, Ph | 307, 325 | 450 |

| 6a | 9f | Br, Me | 306, 320 | 425 |

| 7a | 9g | H, p-MePh | 315 | 455 |

| 8a | 9h | H, p-OMePh | 300, 330 | 455 |

| 9a | 9i | H, p-ClPh, | 288, 310, 335 | 465 |

| 10a | 9j | H, p-OTfPh, | 280, 330 | 470 |

| 11a | 9k | H, p-CF3Ph | 270, 335 | 475 |

| 12a | 9l | NHBoc, Ph | 317 | 450 |

| 13a | 9m | NH2, Ph | 300, 330 | 560 |

| 14a | 9n | H, p-NHBocPh | 317 | 450 |

| 15a | 9o | H, p-NH2Ph | 330 | 470 |

| 16b | 10a | -, Ph | 294 | 418 |

| 17b | 10b | -, Me | 286 | 413 |

| 18c | Coumarin 6 | -,- | 455 | 498 |

a10−4 M solution in 1,2-dichloroethane. b10−5 M solution in 1,2-dichloroethane. c10−5 M solution in CH2Cl2. dNo significant effects were observed on the emission spectra while changing the excitation wavelength or the concentration of the samples.

All pCp-based coumarins demonstrated notable photostability, along with exceptionally larger Stokes shifts (reaching up to 43 478 cm−1) in comparison with their flat analogues. However, these dyes generally exhibited modest fluorescence quantum yields (0.1% < Φ < 5%).

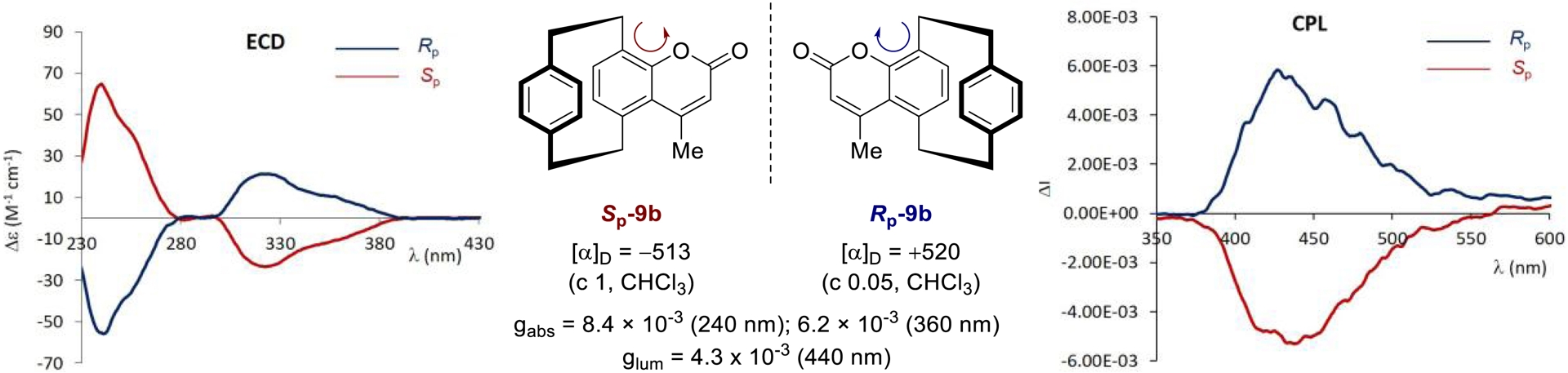

In collaboration with Dr. J. Crassous’s group, we carried out the chiroptical characterization of enantiopure planar chiral coumarins obtained from optically active aldehyde precursors [58]. As expected, electronic circular dichroism (ECD) spectra recorded in CH2Cl2 (10−5 M) displayed well-defined mirror-image signatures for the two enantiomers of compound 9b (Figure 4), with the Sp enantiomer exhibiting a strong positive Cotton effect at 240 nm (Δ𝜀 = +64 M−1⋅cm−1) and a weaker negative one at 320 nm (Δ𝜀 = −23 M−1⋅cm−1). Complementary CPL measurements under identical conditions (𝜆ex = 330 nm) further revealed mirror-image emission profiles, consistent with their enantiomeric nature (Figure 4). Overall, the pCp-based coumarin derivatives showed promising chiroptical responses, with dissymmetry factors of gabs ≈ 6.2 × 10−3 at 360 nm and glum ≈ 4.0 × 10−3 at 440 nm. These values are especially noteworthy given the compact and rigid nature of the molecular framework in contrast to the previously reported systems based on extended π-conjugation. Additionally, the glum/gabs ratio of ∼0.7 suggests minimal structural reorganization upon excitation, an advantageous feature for preserving chiroptical integrity in emissive applications.

Chiroptical properties of pCp-based coumarins Sp-9b and Rp-9b. ECD and CPL spectra were recorded in CH2Cl2 (10−5 M, 𝜆ex = 320 nm).

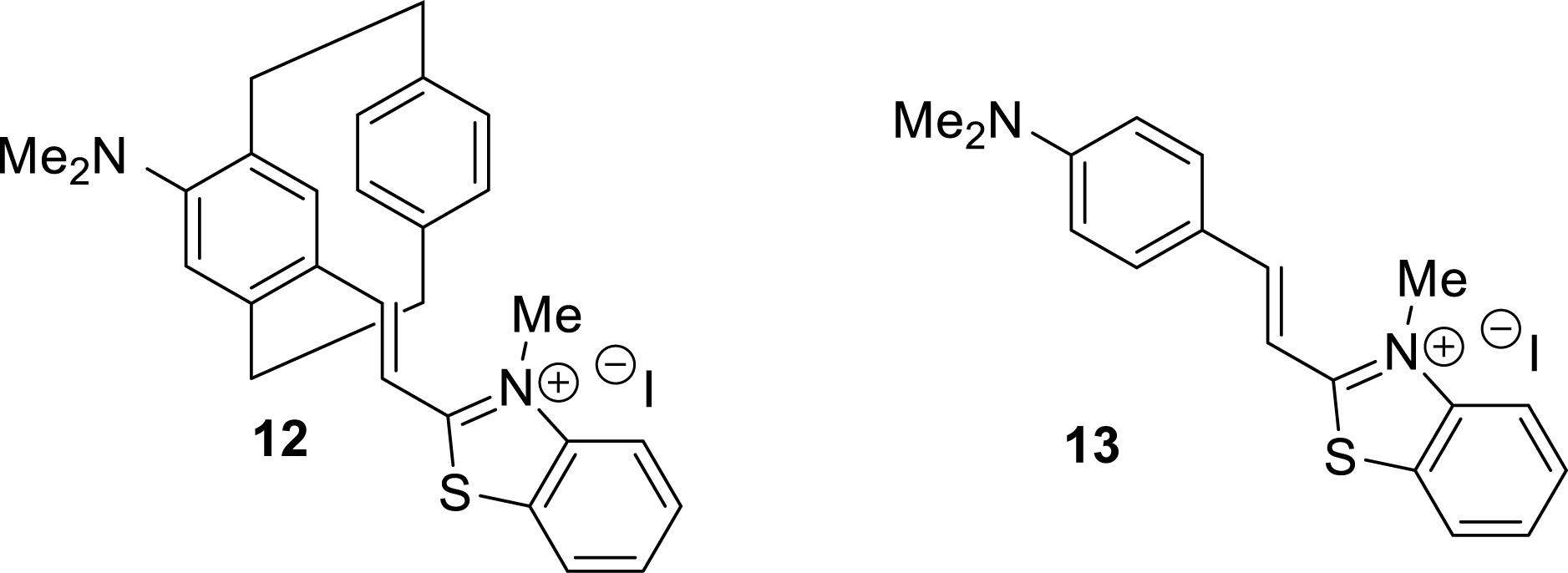

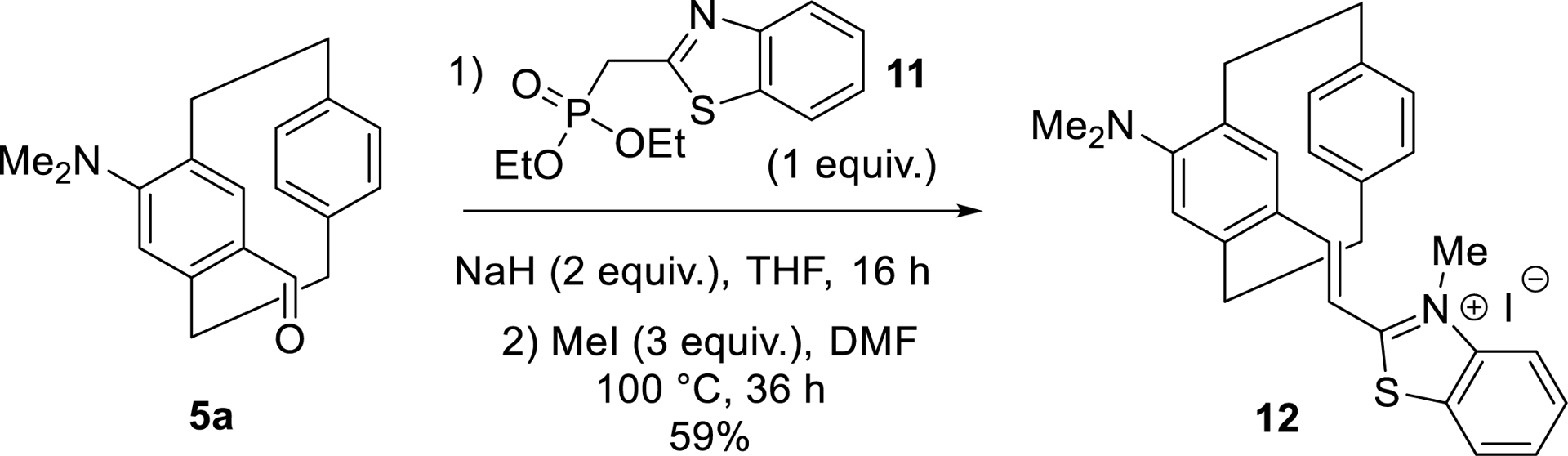

Three-dimensional cyanine-type dyes based on the pCp scaffold were also readily prepared from aldehyde intermediates, particularly those obtained via the regioselective formylation strategy outlined in Table 1. In this case, key aldehyde 5a, bearing a dimethylamino group, underwent a Wittig-type reaction with compound 11, followed by N-methylation of its benzothiazole moiety. This sequence efficiently led to the formation of novel luminescent compound 12, which exhibited emission in the red region of the electromagnetic spectrum (Scheme 4). Once again, both racemic and enantiopure products could be synthesized using the strategies developed in our laboratory [59].

Synthesis of a pCp-based 3D cyanine.

The photophysical properties of three-dimensional cyanine dye 12 were investigated in both dichloromethane and an aqueous Tris-EDTA (TE) buffer, the latter containing 1% DMSO to ensure full solubilization of the organic compound. When comparing the two environments, a modest hypsochromic shift in both absorption and emission maxima was observed upon transitioning from the organic to the aqueous medium (Table 3). Additionally, both the molar extinction coefficient and fluorescence quantum yield were reduced in the TE buffer, indicating diminished brightness in the aqueous phase.

| Dyea | Solvent | $\lambda _{\mathrm{abs}}^{\mathrm{max}}$ (nm) | 𝜀max (M−1⋅cm−1) | $\lambda _{\mathrm{em}}^{\mathrm{max}}$ (nm) | Φf (%)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12 | CH2Cl2 | 597 | 46 × 103 | 645 | 2.0 |

| TEc | 565 | 39 × 103 | 635 | 1.5 | |

| 13 | CH2Cl2 | 553 | 44 × 103 | 607 | 6.2 |

| TEc | 510 | 36 × 103 | 600 | 1.3 |

a10−5 M solution. bAbsolute quantum yields. c1% DMSO was added to fully solubilize the dyes.

Compared to its flat analogue 13 [60], pCp-based cyanine 12 exhibited significantly red-shifted absorption and emission spectra in both organic and aqueous media (Table 3). This pronounced bathochromic shift aligns with observations made for other pCp-derived fluorophores, including the coumarin chromophores discussed earlier. This effect is attributed to the presence of the second aromatic ring in the pCp scaffold, which serves as a mild electron-donating group, thereby modulating the global electronic properties of the dyes.

Overall, these results underscore the remarkable versatility of pCp-based three-dimensional luminophores. By tailoring the functionalization of the pCp core, we can precisely tune absorption and emission profiles to cover the entire visible spectrum and develop differently colored CPL emitters from enantiopure molecules [57]. The diverse families of compounds we have isolated hold promise for a wide range of applications in different domains, including coordination chemistry, photocatalysis, and the chemistry–biology interface. Their potential in these areas will be explored in greater detail in the following sections.

5. Lanthanide luminescence sensitization using [2.2]paracyclophanes

In recent decades, the distinctive photophysical characteristics of lanthanide ions (Ln) have garnered considerable interest, owing to their sharp emission bands and prolonged luminescence lifetimes [61], which make them particularly attractive for imaging and photonic applications [62, 63, 64]. In addition, lanthanide-based organometallic complexes exhibit exceptional photostability, effectively addressing a major limitation of conventional organic fluorophores, namely, photobleaching under prolonged or intense light exposure. A key limitation, however, arises from the intrinsically low molar absorption coefficients of lanthanide cations (𝜀 < 1 M−1⋅cm−1), which severely restricts their direct excitation. To circumvent this issue, the use of antenna ligands, chromophores capable of efficiently absorbing light and transferring the harvested energy to the lanthanide center, has become a widely adopted strategy for efficiently sensitizing lanthanide emission [65, 66].

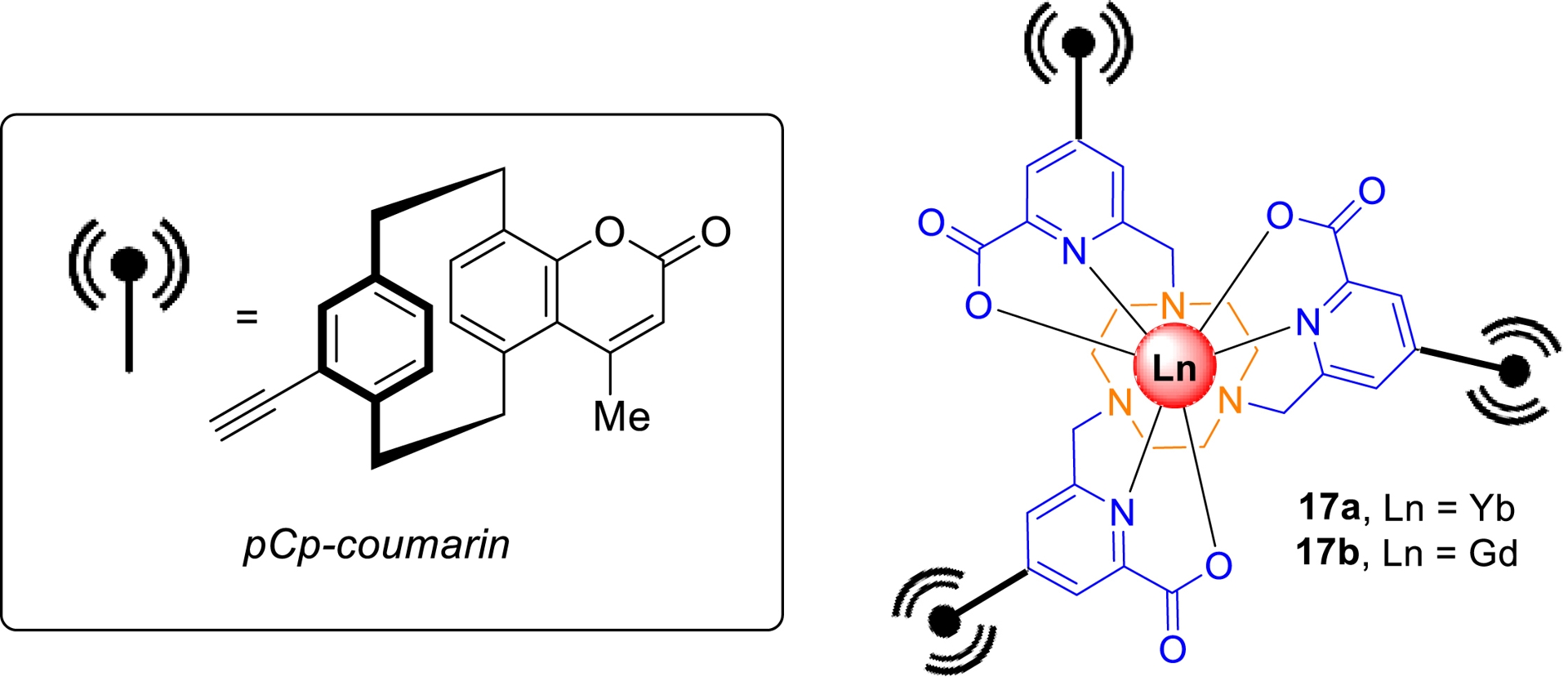

In this context, our group has investigated the potential of luminophores derived from pCp as antenna or ligands for lanthanide sensitization. While pCps have demonstrated significant utility in transition metal coordination chemistry [67], their application in lanthanide systems, either as antennas or as coordinating ligands, remains largely unexplored to date [68]. We thus identified a promising opportunity to expand the functional utility of pCp-based scaffolds by designing new Ln–pCp complexes with enhanced photophysical performance.

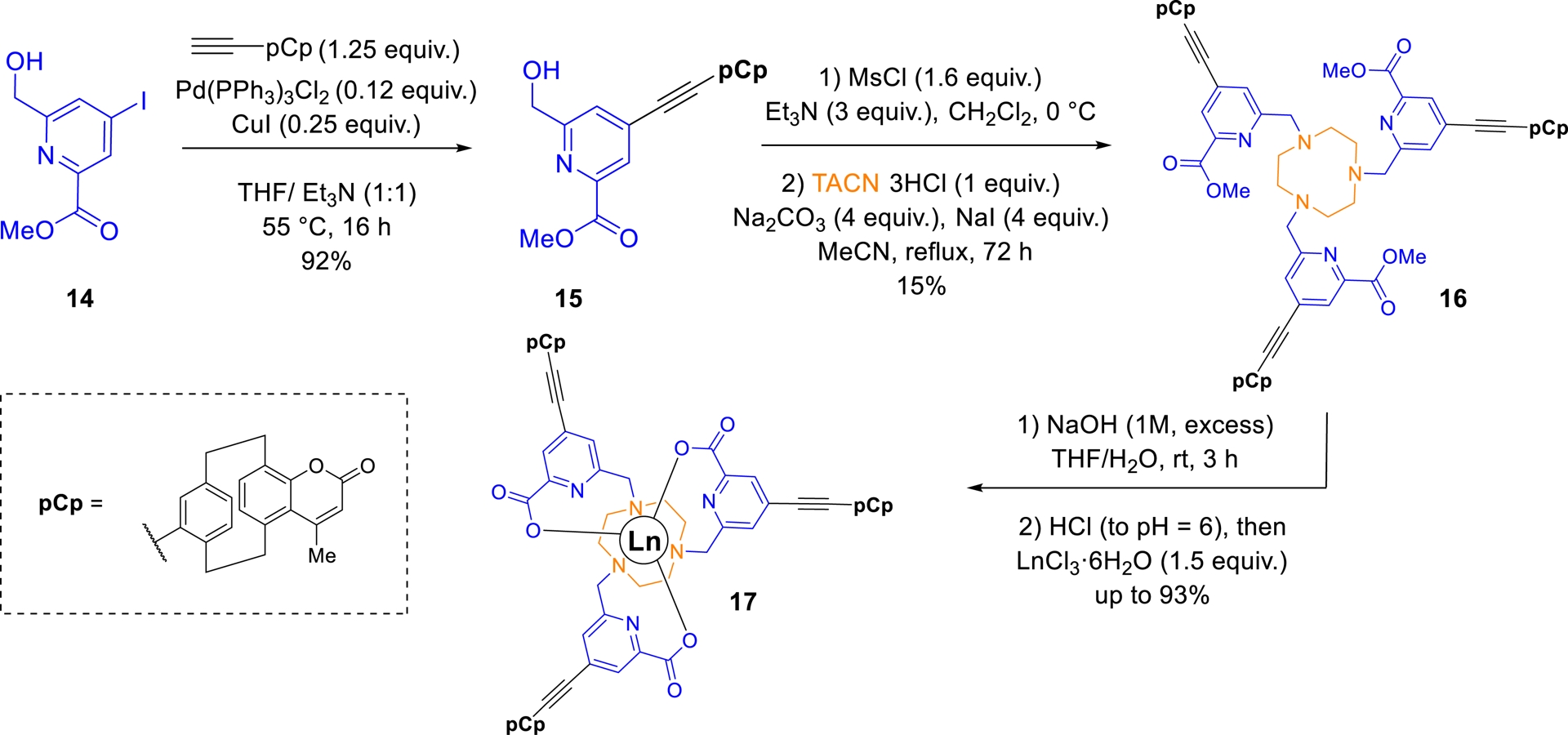

As part of this study, in collaboration with Dr. O. Maury’s group (ENS Lyon), we successfully prepared a series of picolinate-based lanthanide complexes bearing pCp-derived coumarin antennas (Scheme 5) [69]. The synthesis of these molecular objects began with compound 15, obtained from a 3D coumarin bearing a triple bond at its pseudo-para position, via a Sonogashira cross-coupling with iodo-picolinic ester 14. Following mesylation, the intermediate was coupled to 1,4,7-triazacyclononane (TACN), yielding target ligand 16 in 15% overall yield after purification by column chromatography. Complexation with lanthanide ions was then carried out via in-situ saponification, followed by the addition of the hydrated lanthanide chloride at pH 6 (Scheme 5).

Synthesis of Ln complexes incorporating pCp-based coumarins as antennas.

Spectroscopic characterization revealed that the pCp–coumarin unit undergoes rapid intersystem crossing from the singlet to the triplet excited state [E(T1) = 19 500 cm−1]. The triplet-state energy is well-matched for efficient energy transfer to Yb3+ and Gd3+ ions. This was confirmed by excitation of the antenna at 332 nm, which resulted in the characteristic near-infrared (NIR) luminescence of Yb3+ in complex 17a (𝜆em = 980 nm, Table 4, entry 1).

| Ln | 𝜆abs (nm)a | 𝜀 (L⋅mol−1⋅cm−1) | 𝜆em (nm)a | 𝜏obs (μs)a | Φb | ΦΔc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 17a | 332 | 48.5 × 103 | 980 | 9.48 | <0.01 | 0.00 |

| 17b | 332 | 61 × 103 | 422 | - | <0.01 | 0.45 |

aSolution in CH2Cl2 (10−5 M); bfluorescence quantum yield; cquantum yield for singlet oxygen generation.

Notably, under the same excitation conditions, Gd3+-containing complex 17b was found capable of generating a singlet oxygen, with a quantum yield of ΦΔ = 0.45 (Table 4, entry 2) [69]. These findings highlight the potential of pCp-based architectures for the development of lanthanide complexes with tunable and multifunctional properties [70].

Lanthanide ions are currently the focus of extensive research in the field of molecular magnetism [71], as they are prime candidates for the design of single-molecule magnets (SMMs). Unlike traditional magnets, which consist of large assemblies of atoms, SMMs are composed of discrete mono-, di-, or polynuclear complexes capable of retaining magnetic information at low temperatures [72]. To fully harness the potential of SMMs for practical use, it is crucial to investigate their magnetic properties in relation to other physical characteristics, such as luminescence and chirality. This could pave the way for multifunctional materials in emerging technologies, such as: quantum computing, where the integration of stable magnetic states and optical properties could lead to more reliable qubits; molecular electronics, where combining magnetic and luminescent properties may improve device performance and enable further miniaturization; and high-density data storage, where the ability to manipulate and store information at the molecular level could transform data retention capabilities. In this context, luminescent SMMs based on lanthanide complexes, incorporating ligands with central, axial, or helical chirality, have been developed [73]. Embedding rare-earth ions within chiral organic frameworks facilitates chirality transfer from the ligand to the metal center, generating circular anisotropies at the lanthanide ion level. This can give rise to phenomena such as CPL and magnetochiral dichroism (MChD) [74]. Surprisingly, planar chiral ligands have yet to be utilized to modulate these intriguing properties in lanthanide complexes.

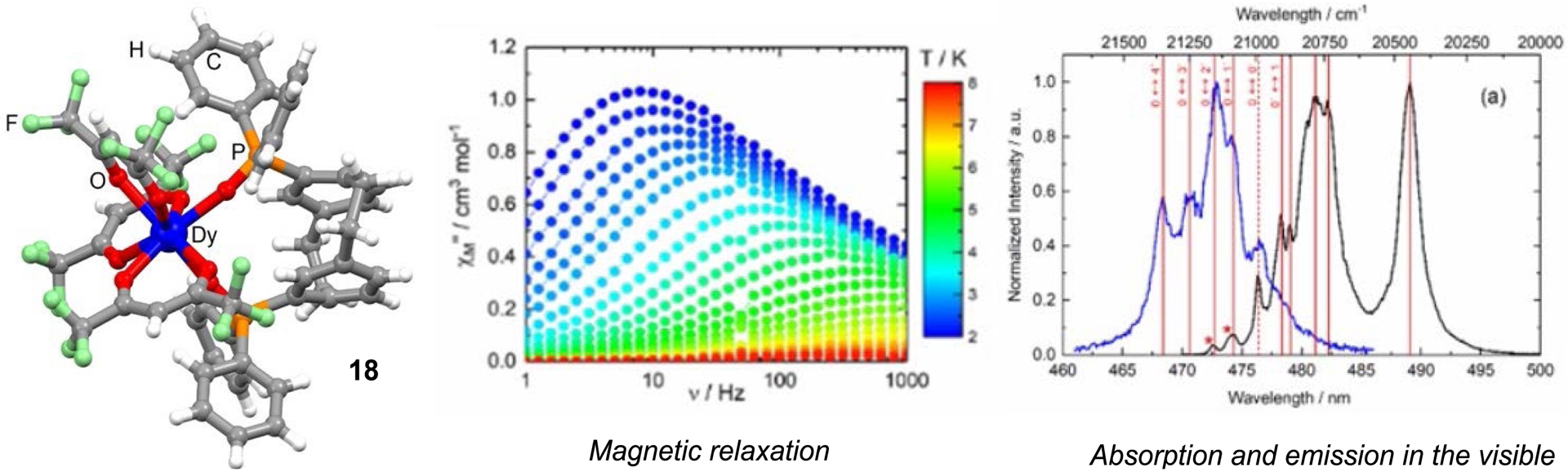

Recently, in collaboration with Dr. O. Maury (ENS Lyon) and Dr. F. Pointillart (Univ. Rennes 1), we employed racemic pCp-derived phosphine oxides as ligands to finely tune the crystal field and electronic environment surrounding Yb3+ and Dy3+ ions, thereby enabling the manifestation of slow magnetic relaxation (Figure 5). The synthesized complexes also exhibited distinct luminescence in the visible or NIR regions of the electromagnetic spectrum. A magneto-structural correlation between the emission and magnetic properties was established for these new complexes, thereby contributing to a deeper understanding of the interplay between these phenomena [75].

Luminescence and magnetic properties of a Dy(III) complex incorporating a pCp-based ligand.

Our laboratory is currently exploring the use of enantiopure pCps as antennas or ligands for lanthanide ions, with the objective of developing novel multifunctional molecular systems that integrate luminescence, magnetism, and planar chirality.

6. [2.2]Paracyclophanes as building blocks for the design of organic photocatalysts

At the beginning of the last century, Ciamician recognized that visible light could serve as a renewable and cost-effective energy source for driving chemical reactions under mild and environmentally friendly conditions [76]. Since then, the fields of photochemistry and photocatalysis have unveiled numerous opportunities for reimagining established reactions and pioneering pathways to previously inaccessible products [77]. Over the years, a variety of highly performant photocatalytic systems have been developed, ranging from metal-based compounds such as ruthenium and iridium polypyridyl complexes to fully organic molecules like eosin Y or acridinium salts. Despite these inspiring advances, the quest continues for novel, more versatile molecules capable of promoting a broader range of catalytic photoreactions. Regardless of their intriguing photophysical properties and considerable potential, pCps had remained largely unexplored as catalysts in photochemical transformations until very recently [39].

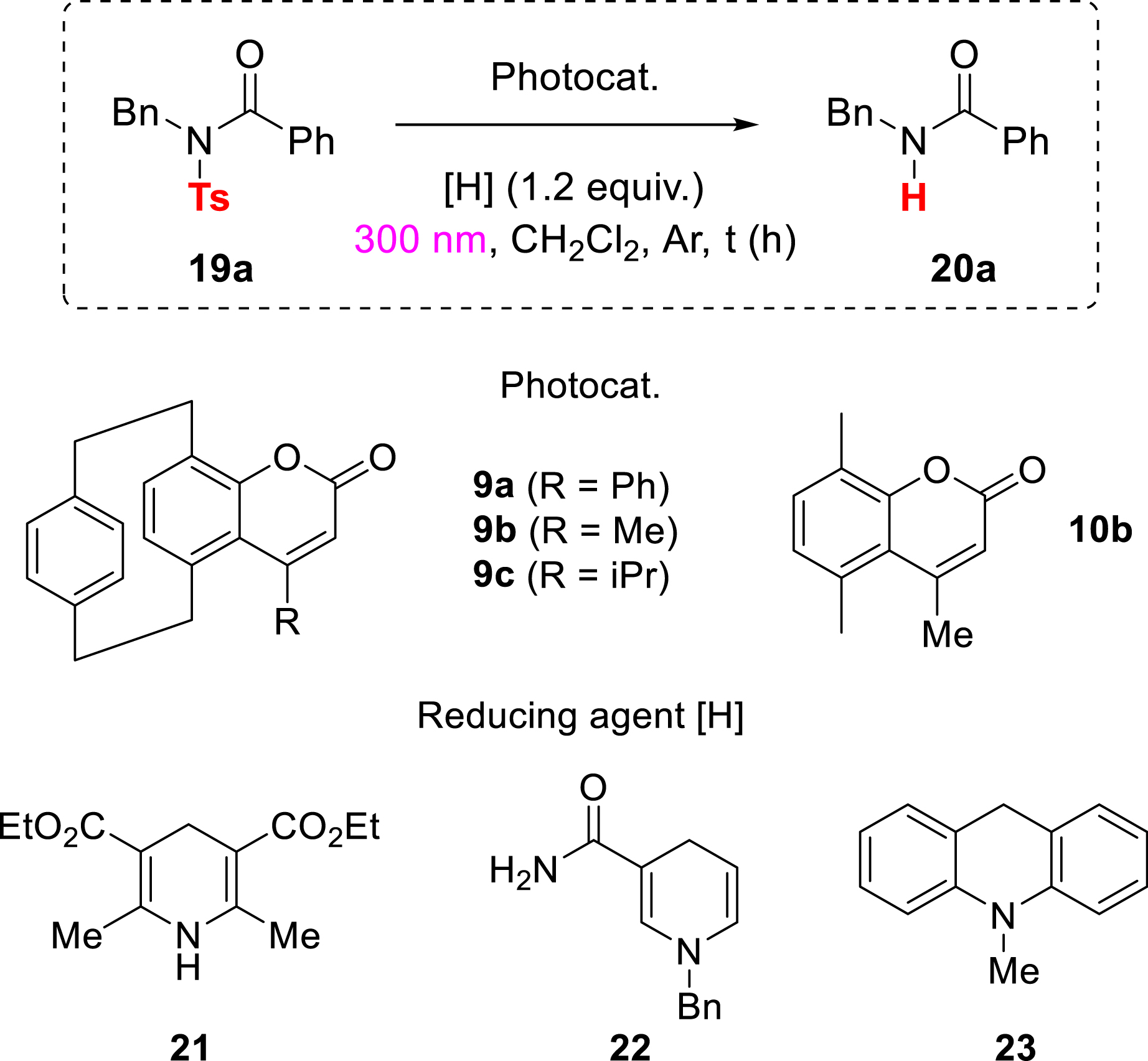

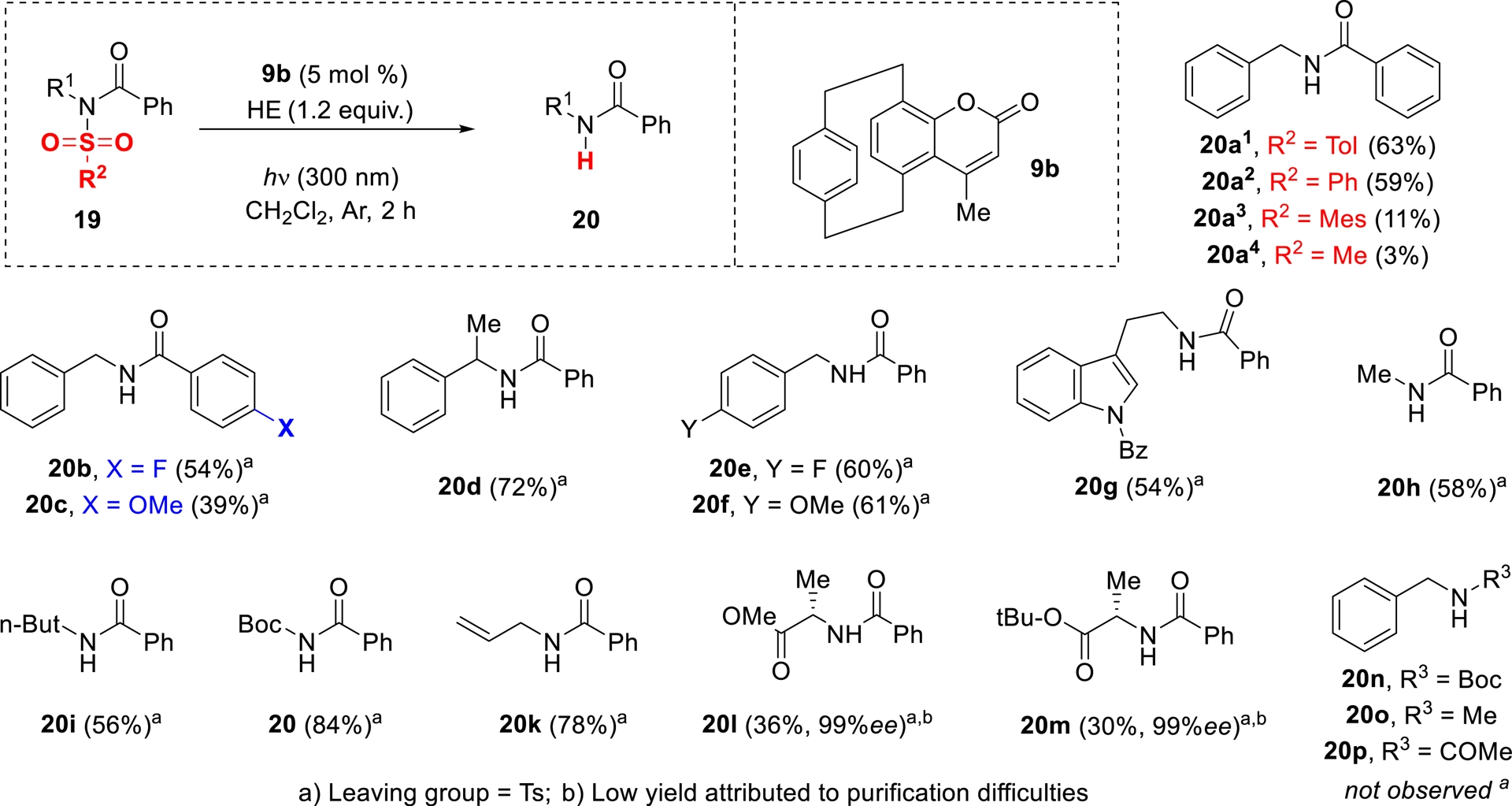

As a proof of concept, and inspired by previous reports [78, 79, 80], our group demonstrated that pCp-based coumarins can serve as organic photocatalysts, effectively promoting desulfonylation reactions under light irradiation [81].

Starting from a readily accessible model substrate (19a, Table 5), prepared according to a reported procedure [78], coumarin derivative 9b demonstrated effective photocatalytic activity for the reductive cleavage of the tosyl protecting group. Using a Hantzsch ester as the sacrificial electron donor, irradiation at 300 nm led to 65% conversion within 2 h (Table 5, entry 1). Prolonging the reaction time did not improve this outcome (Table 5, entry 2); however, catalyst loading could be reduced from 20 to 5 mol% without any loss in efficiency (Table 5, entries 3 and 4). A series of structurally related pCp-based coumarins was evaluated to probe structure–activity relationships. Interestingly, catalyst 9a bearing aryl substituents proved significantly less effective (Table 5, entry 7), indicating that an alkyl group on the coumarin framework may be crucial for efficient photocatalysis in this case. Control experiments further confirmed the key roles of each component: no conversion was observed in the dark or in the absence of the Hantzsch ester (Table 5, entries 8 and 9), while reactions conducted without the pCp-coumarin—or with pCp-deprived analogue 10b—resulted in only traces of conversion (Table 5, entries 10 and 11). These findings underscore the unique contribution of the pCp moiety to the activity of the photocatalyst. The presence of oxygen significantly suppressed the deprotection (Table 5, entry 12), and no conversion was observed when TEMPO, a well-established radical scavenger, was added to the reaction mixture (Table 5, entry 13). Alternative reducing agents were evaluated as well but did not exhibit performances comparable to the Hantzsch ester (Table 5, entries 14–16).

| Entry | Photocat. (mol%) | [H] | t (h) | Conv. (%)e |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 9b (20) | 21 | 2 | 66 |

| 2 | 9b (20) | 21 | 16 | 71 |

| 3 | 9b (15) | 21 | 2 | 63 |

| 4 | 9b (5) | 21 | 2 | 65 |

| 5a | 9b (5) | 21 | 2 | 64 |

| 6 | 9c (5) | 21 | 2 | 56 |

| 7 | 9a (5) | 21 | 2 | 26 |

| 8b | 9b (5) | 21 | 2 | - |

| 9 | 9b (5) | - | 2 | - |

| 10 | - | 21 | 2 | 9 |

| 11 | 10b (5) | 21 | 2 | 14 |

| 12c | 9b (5) | 21 | 2 | 19 |

| 13d | 9b (5) | 21 | 2 | - |

| 14 | 9b (5) | 22 | 2 | - |

| 15 | 9b (5) | 23 | 2 | - |

| 16 | 9b (5) | n-Bu4NBH4 | 2 | - |

Reactions were performed in a Rayonet photochemical reactor equipped with eight 300 nm lamps (T = 29 °C, c = 0.05 M). aReaction performed under more diluted conditions (c = 0.025 M); breaction performed in dark (T = 25 °C, c = 0.05 M); creaction performed under an oxygen atmosphere; dreaction performed in the presence of TEMPO (1 equiv.); edetermined by 1H NMR analysis.

The scope of the reaction was subsequently examined using the conditions optimized on substrate 19a, as illustrated in Scheme 6. The deprotection of a range of sulfonyl groups, including tosyl (Ts), phenylsulfonyl (SO2Ph), and mesitylsulfonyl (SO2Mes), was tested using 5 mol% of catalyst 9b. In line with the reactivity observed for the Ts group, efficient removal of the phenylsulfonyl moiety afforded compound 20a3 in 59% yield. Conversely, sulfonamides bearing mesityl or mesyl groups proved unreactive under identical conditions, yielding only trace amounts of the desired product.

Scope of the photodeprotection reaction.

Substrates containing tosyl groups with a variety of functional motifs, such as substituted (hetero)arenes, alkyl chains, and a Boc-protected amine, were well tolerated, affording the corresponding products in good yields. The method also extended to sulfonamides incorporating alternative aroyl groups, although substrates bearing electron-donating substituents showed reduced efficiency (Scheme 6).

Notably, the protocol was compatible with stereochemically sensitive compounds. When enantiomerically enriched substrates were subjected to the reaction conditions, the corresponding products were obtained with full retention of enantiopurity. This indicates that the transformation proceeds without racemization, even in the presence of base-sensitive stereogenic centers (Scheme 6).

It is worth highlighting that the presence of an aroyl group on the sulfonamide was critical for successful cleavage. Substrates featuring alternative groups such as acetyl, Boc, or methyl failed to undergo transformation under the optimized conditions (Scheme 6).

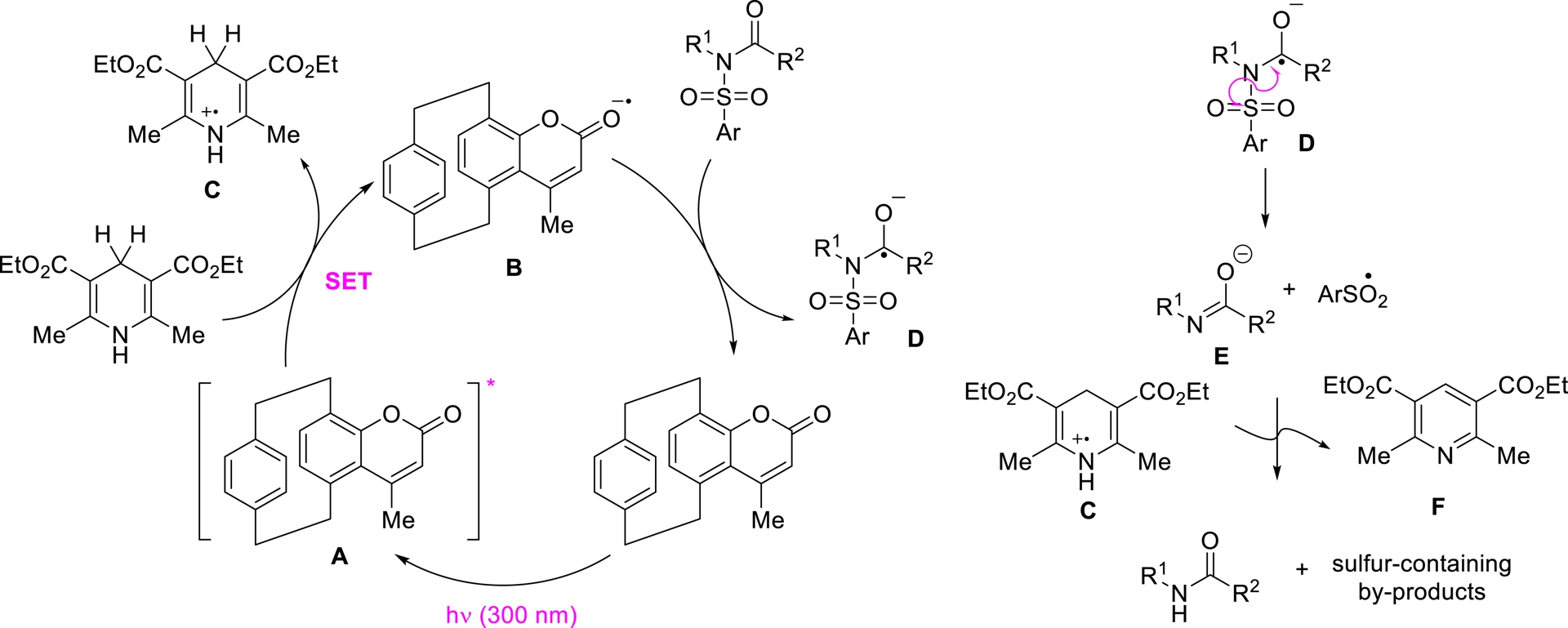

To gain deeper insight into the mechanism of the photodesulfonylation promoted by pCp-based coumarins, we conducted a series of mechanistic studies. Computational analysis realized in collaboration with A. Maruani (LCBPT UPCité) revealed that energy transfer (EnT) from the excited state of catalyst 9b to the lowest excited state of substrate 19a is thermodynamically uphill (ΔGEnT = +1.13 eV), rendering this pathway unlikely. Based on prior studies involving an iridium-based photocatalyst combined with a Hantzsch ester [78], we hypothesized that the sulfonamide cleavage could proceed via a photoinduced electron transfer (ET) mechanism.

Electrochemical measurements of the redox potentials of 9b, 19a, and 21, combined with the determination of the excited-state energy (E∗) of 9b via absorption and fluorescence spectroscopy, enabled the evaluation of the Gibbs free energy for potential photoinduced electron-transfer processes. According to this analysis, ET from the excited catalyst to the Hantzsch ester is thermodynamically favorable (ΔGET = −0.63 eV). Conversely, direct ET from the excited state of 9b to substrate 19a is thermodynamically disfavored (ΔGET = +0.13 eV). Furthermore, UV–Vis absorption studies excluded the formation of electron donor–acceptor (EDA) complexes, as no appreciable spectral changes were detected upon gradual addition of either 19a or 21 to a solution of 9b. Finally, the reaction was shown to halt immediately upon interruption of light irradiation, thereby excluding the involvement of a self-propagating radical chain process in the photocleavage mechanism.

Based on the collected experimental data, the photodesulfonylation was proposed to proceed via the mechanism illustrated in Scheme 7.

Mechanistic proposal for the photodeprotection mediated by pCp-based coumarins.

Upon irradiation at 300 nm, pCp-based catalyst 9b is promoted to its excited state (A), which then undergoes a single-electron transfer (SET) with the Hantzsch ester. This step generates dihydropyridine radical cation C and coumarin-centered radical anion B. The radical anion subsequently interacts with the reaction substrate, forming radical intermediate D and regenerating the ground-state photocatalyst. Note that the formation of intermediate D aligns with analogous species previously identified in related electrochemical processes [82]. Radical D then undergoes homolytic cleavage of its N–S bond, yielding carboxamide anion E and aryl sulfonyl radical $\mathrm{ArSO}_{2}^{\bullet }$. The final desulfonylated product is formed through quenching reactions between these species and dihydropyridine radical cation C. The proposed mechanistic pathway was further corroborated by theoretical calculations carried out in collaboration with A. Maruani (LCBPT UPCité).

Attaining precise control over chirality in photoinduced organic transformations remains one of the foremost challenges in the field of photocatalysis. While numerous reports have demonstrated satisfactory enantioselectivities using costly transition-metal-based catalysts [83], there is growing interest in metal-free strategies. These approaches often employ chiral organocatalysts that function dually as stereocontrolling agents and photosensitizers [84, 85, 86]. Despite these advances, examples of asymmetric photocatalytic reactions driven by such organocatalysts remain scarce [87]. Building on this background, our current research is focused on investigating enantiopure planar chiral pCp derivatives as photocatalysts to promote asymmetric transformations, aiming to broaden the scope of light-driven enantioselective photocatalytic processes.

7. Developing RNA binders using [2.2]paracyclophane scaffolds

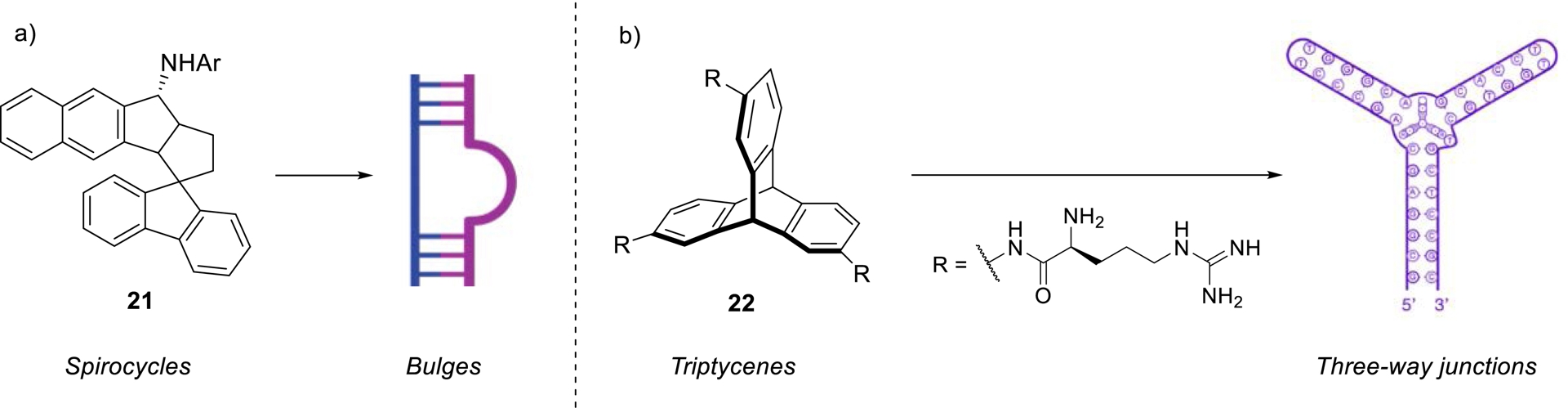

Ribonucleic acids (RNAs) are fundamental biomolecules involved in the regulation of a variety of different cellular processes, including, for instance, gene expression and protein synthesis [88]. Beyond their canonical roles, RNAs have increasingly been recognized as key actors in the onset and progression of various diseases, such as certain cancers, as well as genetic or neurodegenerative disorders [89, 90]. Today, RNA is broadly recognized as a valuable therapeutic target. However, despite this acknowledged potential, developing small molecules that selectively bind to RNA and modulate its function remains a significant challenge in medicinal chemistry.

Most RNA-binding ligands identified to date are planar or rod-like molecules that may show strong binding affinity but often lack selectivity [91, 92, 93, 94, 95]. Their limited ability to distinguish between closely related RNA structures, or even between RNA and DNA, significantly restricts their therapeutic usefulness. Consequently, there is an increasing need to discover and develop novel molecular scaffolds that combine high specificity with strong binding to well-defined RNA targets.

Small molecules interact with nucleic acids through diverse binding modes. Cationic ligands primarily participate in electrostatic interactions with the negatively charged phosphodiester backbone, whereas flat aromatic compounds typically participate in π–π stacking interactions with nucleobases. These interactions can occur via intercalation between base pairs or by occupying the major and minor grooves of helical structures. However, these binding modes are intrinsically limited in selectivity and often fail to distinguish between RNA and DNA duplexes, owing to their similar base-pairing architectures.

To circumvent these limitations, recent studies have focused on incorporating non-planar aromatic motifs that exploit the inherent structural plasticity of RNA. Indeed, unlike DNA, RNA is predominantly found in cell as single-stranded sequences and capable of folding upon itself to generate complex secondary and tertiary architectures, including bulges, internal loops, pseudoknots, and three-way junctions. These unique structural features offer distinct molecular recognition sites for small molecules. For instance, spirocyclic compounds have demonstrated remarkable selectivity for bulged, non-canonical RNA regions (Scheme 8a) [96, 97].

Examples of three-dimensional ligands preferentially targeting non-paired RNA structures.

Similarly, triptycene-based ligands have been reported to specifically target three-way junctions (Scheme 8b) [98, 99, 100]. Notably, these last compounds exhibited potential as modulators of the heat shock response in E. coli, highlighting their functional relevance as RNA-targeting agents. The non-planar architecture of these molecules, which arranges aromatic groups across orthogonal planes, appears to mitigate non-specific intercalation into double-helical regions. This spatial configuration enhances selectivity for non-duplex RNA motifs while minimizing off-target interactions with double-stranded DNA, thus overcoming a common limitation of planar aromatic RNA-binding compounds.

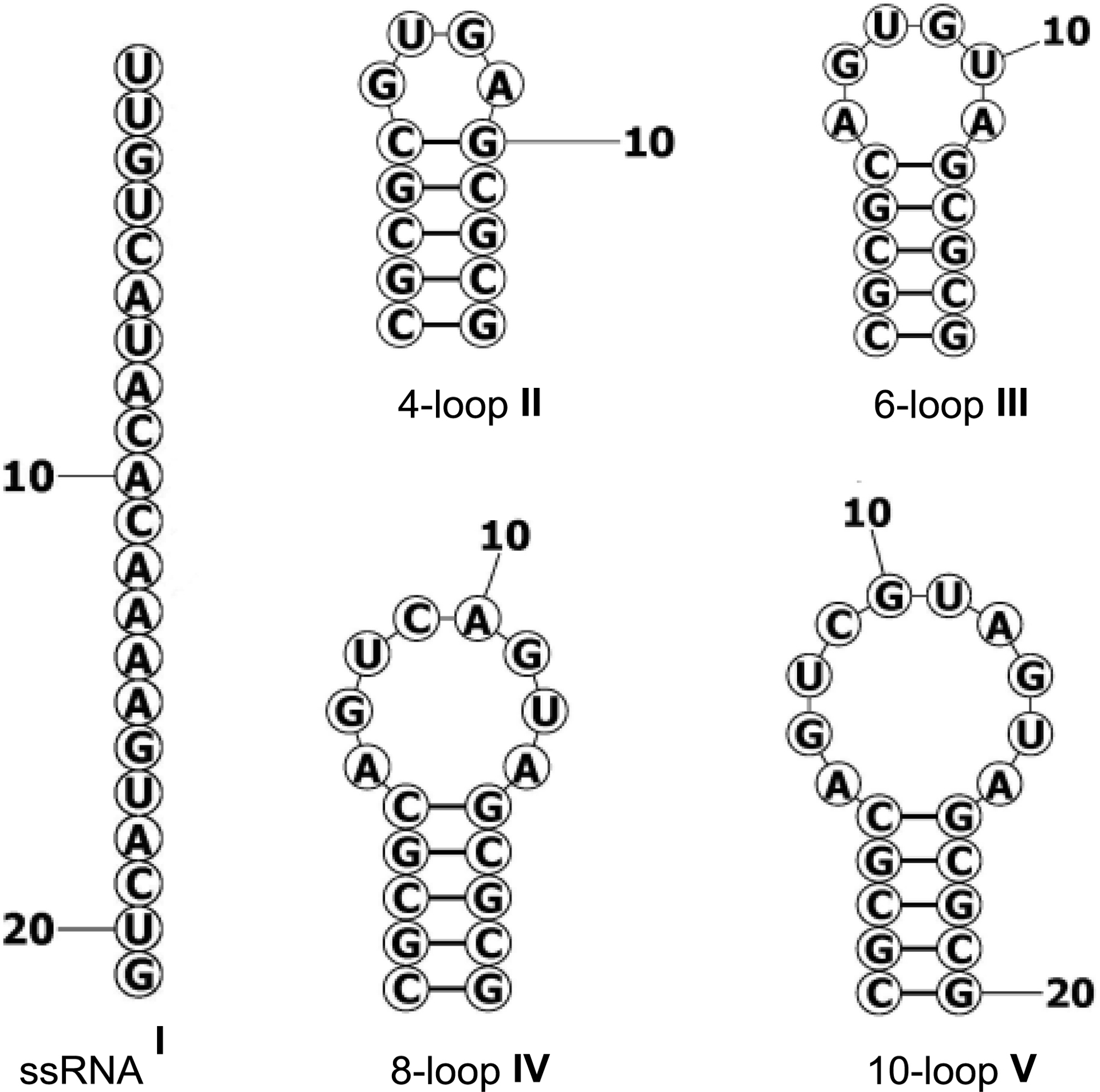

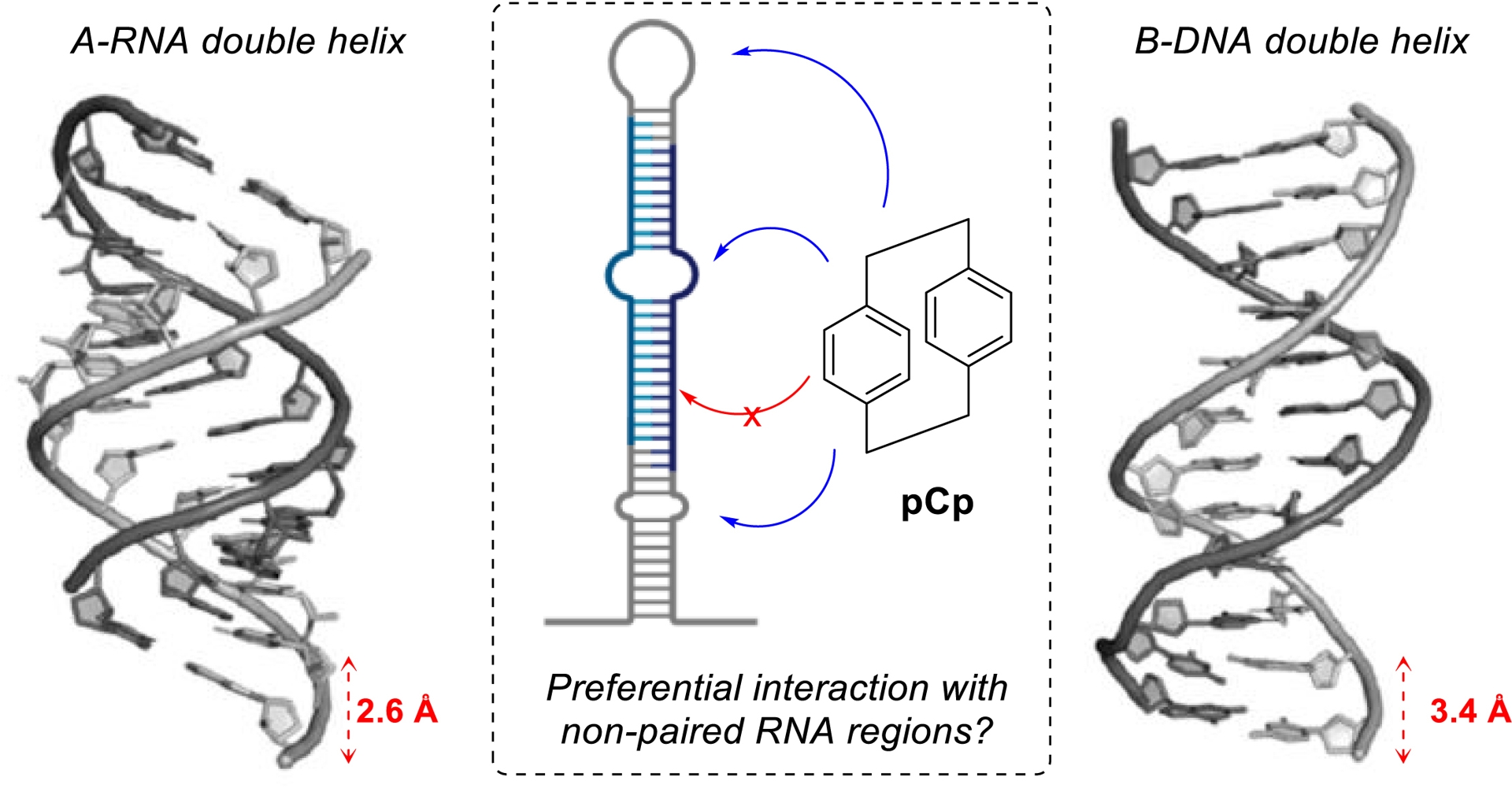

Inspired by these precedents, we hypothesized that pCps could preferentially drive recognition of non-helical RNA structural motifs. Indeed, their rigid and sterically demanding architecture, characterized by a 3.1 Å distance between the benzene moieties (Figure 1), does not match the helical rise per base pair in double-stranded RNA (2.6 Å) or DNA (3.4 Å), making intercalation unlikely and effectively limiting interactions with RNA or DNA duplexes (Figure 6).

Rationale for targeting non-paired RNA motifs using pCp.

Guided by this rationale, we explored pCp as a central core for the design of novel RNA-binding ligands. Simultaneously, we aimed to exploit the intrinsic photophysical properties of pCps to monitor ligand–RNA interactions via fluorescence spectroscopy, enabling real-time observation of binding events.

Cyanine dyes are well-established probes in chemical biology, frequently used for nucleic acid staining [60, 101, 102]. These dyes exhibit strong fluorescence turn-on behaviors upon target binding. We therefore set out to compare the luminescence responses of pCp-based cyanine dye 12 with those of analogous flat cyanine 13 in the presence of nucleic acids.

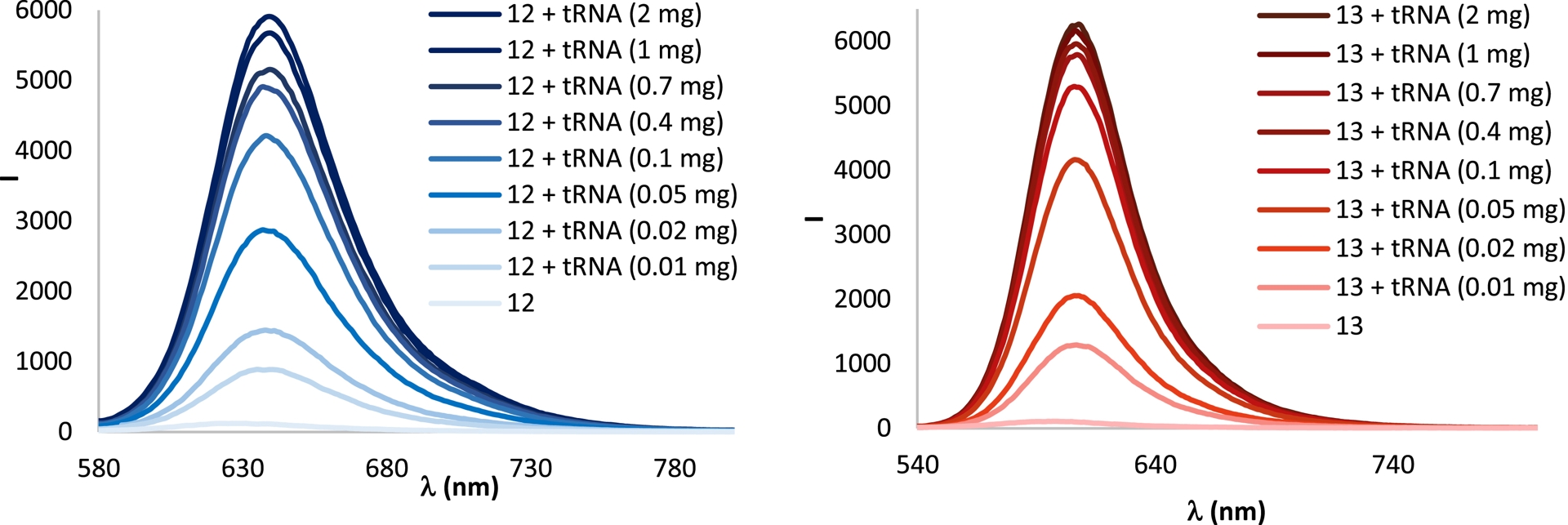

As described earlier in this article, both compounds exhibited low emission in aqueous buffer (Table 3). However, upon the addition of increasing amounts of tRNA, a significant fluorescence enhancement was observed for both cyanines, demonstrating that incorporation of the pCp moiety into the luminophore does not negatively impact the turn-on behavior of the cyanine (Figure 7) [59].

Turn-on fluorescence responses of cyanines 12 (in blue) and 13 (in red) in the presence of increasing amounts of tRNA.

Digestion studies with RNase A confirmed that the observed fluorescence enhancement is attributable to the presence of RNA in solution [34]. Since cyanines are known to form aggregates [61]—a tendency also confirmed for pCp derivative 12—, the observed turn-on responses were attributed to disaggregation processes triggered by the interaction of the dyes with RNA.

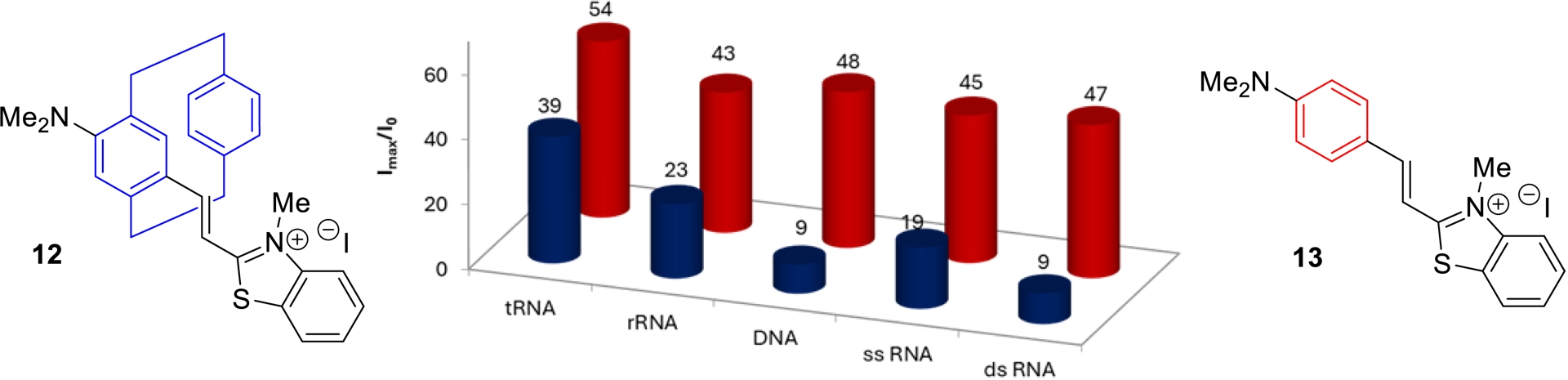

We next compared the behavior of the flat and three-dimensional cyanines in the presence of different types of nucleic acids. Interestingly, flat compound 13 exhibited comparable fluorescence turn-on responses with all tested nucleic acids (Figure 8, in red), indicating a non-selective interaction profile. In contrast, three-dimensional pCp-based derivative 12 displayed only modest fluorescence enhancements in the presence of double-stranded DNA or RNA (Figure 8, in blue), while it showed markedly stronger turn-on behaviors with nucleic acids containing multiple unpaired regions, with a clear preference for tRNA.

Turn-on fluorescence responses of cyanines 12 and 13 (10−6 M) in the presence of diverse nucleic acid (0.4 mg/mL) in Tris-EDTA (TE) buffer at 20 °C.

Fluorescence titrations performed with custom-designed hairpin loops of different sizes (I–V, Table 6) further demonstrated that pCp-based dye 12 interacts weakly with small loop structures, while exhibiting higher binding affinity—reflected by lower dissociation constants (Kd)—for larger loops. Remarkably, the dye showed a marked preference for a sequence containing eight unpaired nucleotides (Kd ∼ 0.54 μM, Table 6). It is also worth noting that, at this stage, both racemic and enantiopure compounds exhibited similar behavior [34].

| Ia | IIa | IIIa | IVb | Vb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14.22 | 24.53 | 6.04 | 0.54 | 1.65 |

| ±14.46 | ±6.60 | ±2.05 | ±0.16 | ±1.14 |

a10−6 M solution of dye 12 in Tris-EDTA (TE) buffer. b10−7 M solution of dye 12 in Tris-EDTA (TE) buffer. Data are presented as mean of the three independent experiments ± standard deviation.

In the future, the ability of enantiopure pCp-based luminophores to emit circularly polarized luminescence may be harnessed to monitor RNA–ligand interactions via CPL spectroscopy. This approach may offer several advantages, including enhanced sensitivity and selectivity stemming from the polarized nature of the emitted light, reduced background interference relative to conventional fluorescence methods, and the potential to provide detailed insights into the chiral environment and binding-induced conformational changes of RNA structures.

8. Conclusions

Thanks to their unique three-dimensional geometry, distinctive electronic properties, and atypical reactivity, [2.2]paracyclophanes (pCps) have emerged as versatile molecular platforms attracting growing interest across diverse areas of chemical research.

In this account, we have highlighted a variety of strategies that enable the selective functionalization of their aromatic cores, efficient control over planar chirality, and modulation of their photophysical properties. The methods developed in our laboratory have enabled access to structurally diverse pCp scaffolds with tunable spectroscopic behaviors on synthetically useful scales. These rigid π-stacked systems exhibited significant potential in fields such as organic and organometallic luminophore chemistry, photocatalysis, and chemical biology. Nevertheless, important challenges remain to be addressed. For example, the development of selective functionalization protocols targeting the ethylene bridges and the meta or pseudo-meta positions of these scaffolds could greatly broaden their chemical diversity. Strategies to further modulate the absorption and emission properties of functionalized pCps, such as attaining higher brightness and enhanced CPL efficiency, also warrant continued investigation. In lanthanide chemistry, pCp-based ligands with planar chirality may lead to the development of next-generation luminescent and multimodal metal complexes. The use of enantiopure chiral pCp derivatives as photosensitizers in photoredox catalysis also remains underexplored and could enable the design of novel light-activated asymmetric transformations. Finally, our recent efforts to incorporate the pCp motif into RNA-binding small molecules have opened promising avenues for targeting non-paired structural motifs within nucleic acids. However, further studies are required to better elucidate the precise binding mode of pCp derivatives to RNA.

In summary, pCps represent a fascinating class of molecular architectures that continue to captivate the chemistry community. Despite the significant progress already achieved in their synthesis and controlled functionalization, we are confident that ongoing research on these original compounds will continue to drive innovation across a range of disciplines, including organic synthesis, materials science, and chemical biology.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their sincere thanks to all undergraduate, master’s, and PhD students, as well as postdoctoral researchers and collaborators, for their invaluable contributions. Special thanks are due to J. Crassous, L. Favereaux, and F. Pointillart (Univ. Rennes 1); O. Maury and L. Abad-Galan (ENS Lyon); A. Maruani, S. Lajnef, F. Peyrot, C. Sagné and S. Turcaud (Paris Cité University).

Declaration of interests

The authors do not work for, advise, own shares in, or receive funds from any organization that could benefit from this article, and have declared no affiliations other than their research organizations.

Funding

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of the CNRS and Paris Cité University (IdEx Dynamique Recherche pCp-Photocat - ANR-18-IDEX-0001), as well as funding from the Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR JCJC PhotoChiraPhane - ANR-19-CE07-0001-01).

CC-BY 4.0

CC-BY 4.0