1 Introduction

Crithmum maritimum (Apiaceae), a halophyte typical of rocky coastal ecosystems, shows substantial economical and medicinal potentials [1]. Its seeds contain significant amounts of oil, potentially edible due to its fatty acid composition, close to that of olive oil [2]. In a preliminary study, we showed that salinities exceeding 50 mM NaCl were detrimental for the germination of Tunisian population of C. maritimum [3]. In saline environments, high salt levels are known to impair seed germination of halophyte species [4]. Despite the mechanisms of this inhibition remain unclear, such an inhibition may partly ascribed to the strong decline in gibberellic acid (GA) levels during seed imbibition [5]. Interestingly, the exogenous application of GA is known to efficiently alleviate the harmful effect of salinity on halophyte germination [6,7]. Similar positive effects have been reported following the exogenous supply of nitrogen [8,9]. On the other hand, germination experiments using fluridone, an ABA synthesis inhibitor, revealed that dormancy is an active process tightly related to the de novo synthesis of ABA during seed imbibition [10].

As changes in growth regulators balance that are induced by salinity may largely account for the salt-induced inhibition of germination [11], the understanding of the hormonal action on germination process is a major key to improve germination of salt-sensitive species and subsequently their establishment under saline conditions. The present work investigates the role of GA3, ABA, and NO−3 during the germination of the oilseed halophyte C. maritimum under increasing NaCl salinity in order to get more information on the mechanisms by which salinity may inhibit germination of this species in the natural conditions.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Fruit collection

Mature fruits were collected in December 2005 from plants in the natural populations growing in the rocky coast of Tabarka (N , E ), located in N-W of Tunisia. In this area, annual mean precipitations reach about 1200 mm and monthly temperatures range between 8 °C during the winter (December to February) and 35 °C during the summer (June to August). Fruits were stored under dry laboratory conditions until experiments were started, in May 2006. At fruit maturation, the mesocarp of C. maritimum is a spongy coat that is easy to remove. However, the endocarp and the secretory envelope, remain firmly attached to the seed. Therefore, in this study the term seed refer to seed plus endocarp and a secretory envelope.

2.2 Experiments

Seeds were disinfected in a 3.5% calcium hypochlorite solution for 5 min before starting the germination tests. They were placed in 9-cm diameter Petri dishes (25 seeds par each) and covered with a double layer of filter paper type Filtrak moistened with 2 ml of distilled water or a test solution. The Petri dish was recovered with transparent plastic film to reduce the evaporation. At each 7 d, the solution and the filter paper were changed. No modification in the solution volume in Petri dish was observed during treatment.

The following experiments ( per each) were carried out in a growth chamber at conditions that simulate the field conditions during the spring, which are suitable for seed germination (18–23 °C, 8 h–16 h dark–light). White light was produced by five fluorescent lamps (Type OS-RAM 40 W, fluence of 35 μmol m−2 s−1, 400–700 nm) and a 160 W incandescent lamp. Three experiments were achieved:

The impact of the external application of KNO3 (10 mM), GA3 (10 μM), fluridone (FLU) (100 μM), and pacloputrazol (100 μM) on germination was tested over a range of a NaCl concentrations (0, 100, and 200 mM). This experiment was conducted for 42 d.Experiment 1

The effect of KNO3 (10 mM), NaNO3 (10 mM), and KCl (10 mM) exogenous supply was compared, in order to distinguish between the specific effect of NO−3 and that of K+. NH4Cl (10 mM) was used to assess the involvement of NO−3 as a nitrogen source (following its reduction to NH+4) under NaCl salinity (0 and 100 mM). This experiment was conducted over 30 d.Experiment 2

The interaction of ABA (10, 50, and 100 μM) and KNO3 (0 and 10 mM) during germination was assessed over time (12, 18, and 26 d).Experiment 3

2.3 Data collection and statistical analyses

Germinated seeds were counted at two-day interval, and a seed was considered as germinated at the radicle protrusion [12]. Germinated seeds were discarded after counting. The germination parameters determined were: the final percentage germination, calculated the end of germination test and the germination velocity. The latter was estimated with a modified Timson index [13]: , where G is the germination percentage calculated for each two-day interval and T is the total germination time.

Germination data were transformed (arcsine) before the statistical analysis. For the experiment 1 data, a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to evaluate the effect of salinity and that of NO−3, GA3, and FLU on the final germination percentage and germination velocity. In the experiment 2, the effects of NaCl salinity and chemicals compounds (KNO3, NaNO3, KCl and NH4Cl) and their interaction were analyzed using a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). The interactive effects of ABA and NO−3 were analyzed in the same manner. Waller–Dankun test was used to identify significant differences among treatments, using the statistical software SPSS 10.0.

3 Results

3.1 Effects of KNO3, GA3, and FLU on germination under NaCl salinity

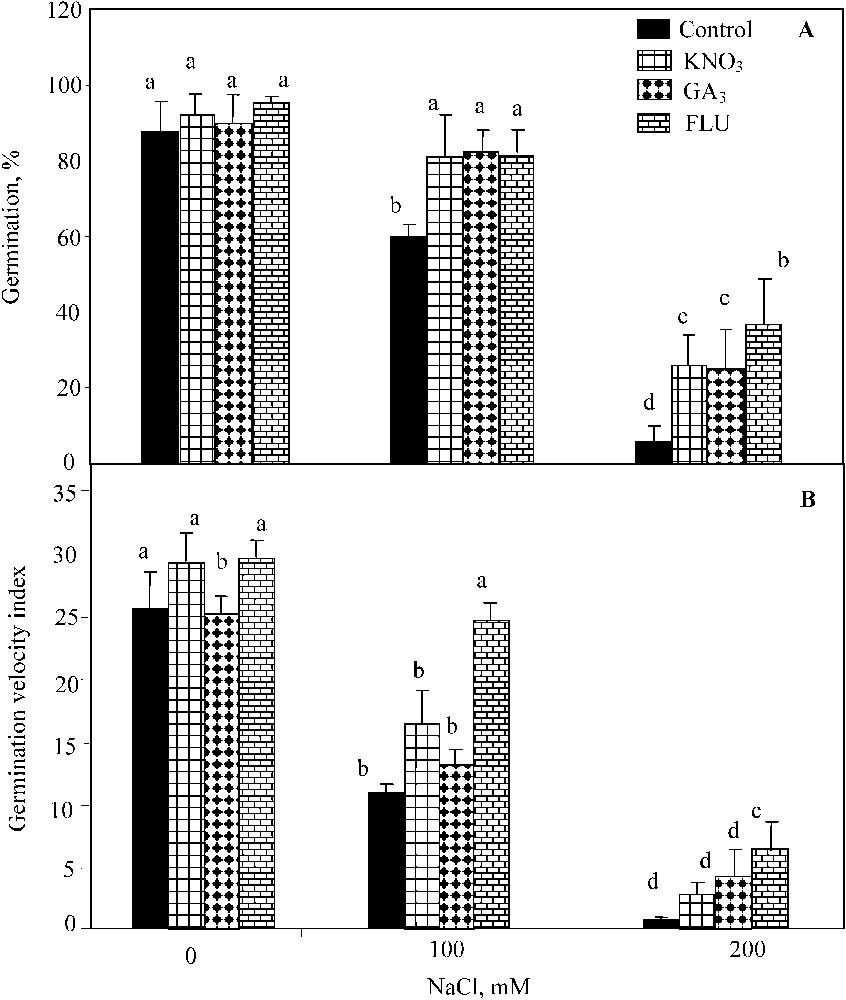

The two-way ANOVA indicated significant individual effects of NaCl salinity (; ) and KNO3 (; ) on seed germination percentage, but the interaction of both factors was not significant. Waller–Dankun test at showed that KNO3 beneficial effect was significant at 100 mM and 200 mM NaCl. KNO3 application resulted in the significant increase of seed germination percentage under NaCl salinity (from 60% and 6% to 81%, and 26% at 100 mM and 200 mM NaCl, respectively) (Fig. 1A). The two-way ANOVA also revealed significant individual effects of NaCl salinity (; ) and GA3 (; ), and their interaction on the germination (; ) (Fig. 1A). GA3 addition restored the final germination percentage up to 70%, and 31% at 100 mM and 200 mM NaCl, respectively (Fig. 1A). The two-way ANOVA showed significant individual effects of NaCl salinity (; ), FLU (; ) and their interaction (; ). The exogenous application of FLU stimulated the final percent germination up to 95%, 81%, and 37% at 0 mM, 100 mM, and 200 mM NaCl, respectively (Fig. 1A).

Final germination percentage (A) and index of germination velocity (B) for seeds germinated under 0 to 200 mM NaCl salinity, in presence of 10 mM KNO3, 3 μM GA3, and 100 μM FLU. Means for each salinity concentration that have the different letters are significantly different at P < 0.05.

As observed for the final germination percentage, the index of germination velocity was significantly improved by KNO3 at 100 mM NaCl (Fig. 1B). The two-way ANOVA indicated significant individual effects of NaCl salinity (; ) and KNO3 (; ) and their interaction (; ). GA3 application significantly enhanced the germination velocity upon NaCl salinity-exposure too (Fig. 1B), and was confirmed by the two-way ANOVA (; ). Yet, the interaction of NaCl and GA3 effect was not significant at . The beneficial effect of FLU on this parameter was also significant (Fig. 1B) (; ) on the germination velocity as well as the interaction of salt and FLU (; ).

3.2 Distinguishing between NO−3 and K+ effects on germination under NaCl salinity

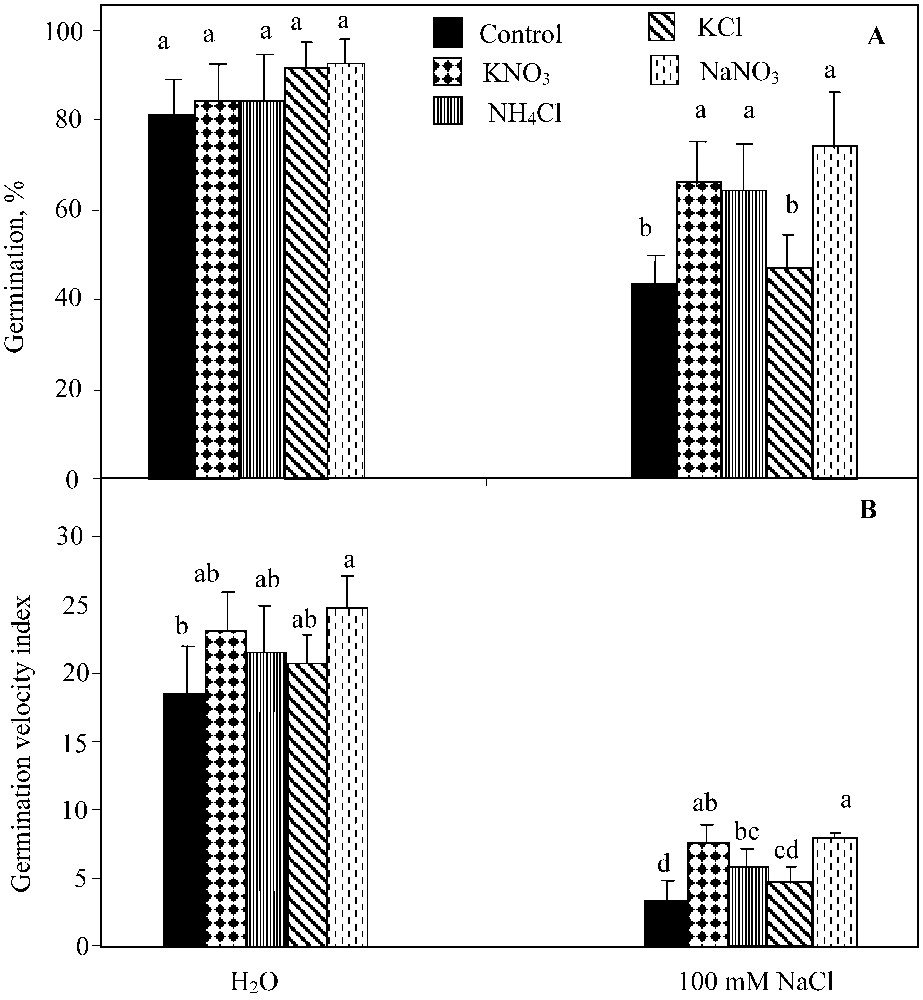

The two-way ANOVA analysis showed a significant effect of NaCl-salinity (; ), the germination-regulating chemicals applied (KNO3, NaNO3, and NH4Cl) (; ) and their interaction (; ) on the germination percentage. KNO3, NH4Cl and NaNO3 supply led to the significant improvement of this parameter under NaCl salinity conditions (Fig. 2A). KCl was much less effective in alleviating the salinity-induced inhibition of germination, since it only slightly improved the seed germination, irrespective of the NaCl treatment applied.

Final germination percentage (A) and index of germination velocity (B) for seeds germinated under 0 or 100 mM NaCl salinity, in presence of 10 mM KNO3, 10 mM NH4Cl, 10 mM KCl, and 10 mM NaNO3. Means for each salinity concentration that have the different letters are significantly different at P < 0.05.

The two-way ANOVA analysis indicated a significant effect of NaCl salinity (; ), germination-regulating chemicals (KNO3, NaNO3, and NH4Cl) (; ) on the germination rate. Yet, their interaction was not significant at . NH4Cl impact was similar to that of KNO3 (, Waller–Dankun test). No significant effect of KCl was registered on the germination velocity index (Fig. 2B).

3.3 Interactive effects of KNO3 and ABA during germination

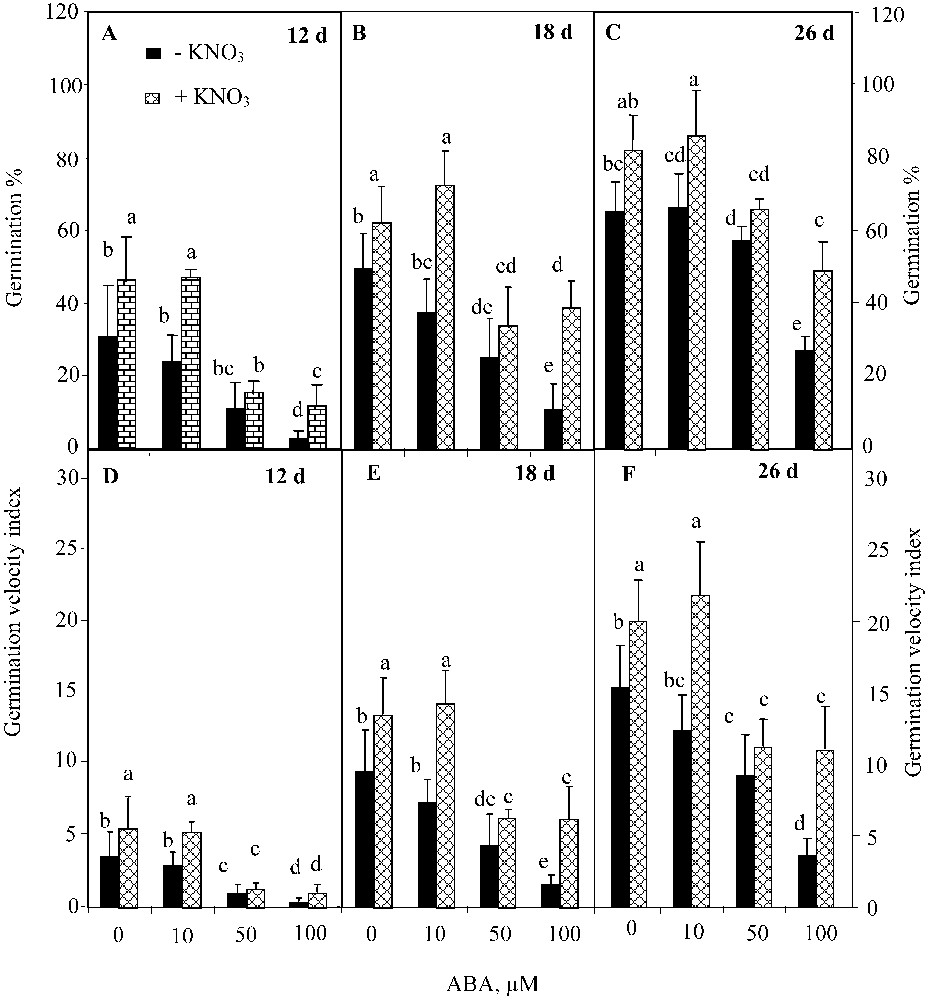

The two-way ANOVA analysis showed a significant effect of ABA (; ) and KNO3 (; ) on the final germination percentage, but their interaction was not significant . Analogous results were found for the germination velocity. ABA inhibited germination over time (Figs. 3A, 3B, and 3C), and reduced the index of germination velocity (Figs. 3D, 3E, and 3F). This trend was more pronounced at higher ABA concentrations. However, KNO3 addition mitigated the detrimental effect of ABA on both germination percentage (Figs. 3A, 3B, and 3C) and germination velocity (Figs. 3D, 3E, and 3F). The positive effect of KNO3 was significant even at the highest ABA concentration (100 μM) (, Waller–Dankun test).

Final germination percentage (A, B, C) and index germination velocity (D, E, F) after 12, 18, and 26 d for seeds germinated in ABA solutions with or without 10 mM KNO3. Means for each histogram that have the different letters are significantly different at P < 0.05.

4 Discussion

Environmental factors like salinity, temperature, and light greatly affect seed germination. This is particularly due to their impact on seed hormone content [14,15]. As in glycophytes, salinity germination of several halophytes is severely reduced by salinity [4,16]. In C. maritimum, NaCl salinity significantly decreased both germination percentage and germination rate at 100 mM and almost fully inhibited these parameters at 200 mM. Nevertheless, this negative impact was considerably alleviated upon NO−3 addition, either as KNO3 or NaNO3. Such an amelioration of germination under saline conditions using either nitrogenous compounds like NaNO3 and KNO3, or hormones has been reported in other halophytes like Allenrolfea occidentalis [8], Atriplex griffithii [17], and Sporobolus arabicus [9]. NO−3 is an important nitrogen source for plants, but also a signal molecule that controls various aspects of plant development [15]. In C. maritimum, a similar germination improvement was found when the nitrate was replaced by GA3. However, the application of pacloputrazol, GA synthesis inhibitor, with or without NO−3 supply, completely impaired the germination process (data not shown). Thus, NO−3 may not effectively substitute for GA. Consistent with our findings, the exogenous application of GA was found to be effective in mitigating NaCl salinity effect on germination of several other halophytes, such as Zygophyllum simplex, Arthrocnemum indicum L., and Prosopis juliflora [7,18,19]. This could be explained by the fact that GA may reduce the ABA level in seeds through the activation of their catabolism enzymes or by blocking the biosynthesis pathway [20].

NO−3 is assimilated following its reduction by nitrate reductase, nitrite reductase, glutamine synthetase and other enzymes, leading to the production of amino acids and nitrogen compounds. Salinity is known to affect germination by decreasing the nitrogen content of seeds, thereby restricting the embryo growth. According to our results, both NO−3 (as KNO3 or NaNO3) and ammonium (as NH4Cl) significantly improved seed germination upon exposure to NaCl salinity. A similar effect was found using thiourea (data not shown). Nitrogen sources including KNO3 and thiourea have been documented to alleviate seed dormancy by decreasing the ABA levels in imbibed seeds [5,14]. Such a positive effect of KNO3 or other nitrogen compounds like thiourea was documented in halophytes like Atriplex griffithii [9], Zygophyllum simplex L. [21], and Suaeda salsa [22], and less tolerant species, such as Lactuca sativa [23] and Avena fatua [24]. In the latter, KNO3 has been proposed to stimulate germination by acting as an osmoticum, thus enhancing water uptake. Since KCl did not significantly increase germination under NaCl salinity, nitrogen (as NO−3 and/or NH+4) may be responsible for the improvement of germination, that was recorded following KNO3 and/or NH4Cl addition to the external medium.

Under NaCl-free conditions (optimal for the germination of this species), ABA markedly decreased the germination percentage as well as the germination rate over time, but KNO3 supply proved to effectively counteract such an inhibition, irrespective of the ABA concentration. The ABA biosynthesis inhibitor fluridone significantly improved germination only at moderate salinity (100 mM NaCl), restoring germination parameters (germination percentage and velocity) to their maximal values (close to that of the control, i.e. 0 mM NaCl). Such a finding provides an indirect evidence for the NaCl-induced ABA accumulation, and suggests that the reduction of germination observed upon exposure to NaCl salinity, could be for the most part attributed to the adverse impact of ABA, since ABA inhibition by fluridone almost fully alleviated this impairment. At 200 mM NaCl, FLU addition was less effective, improving only partially the germination parameters, which leads to think that the germination impairment at high salinities would not be caused solely by the increased ABA synthesis under salinity, but may also result from the toxic effect of salt and/or the delayed mobilization of seed reserves. Previous studies reported that ABA accumulates in plants dealing with abiotic constraints [25] and that ABA application or ABA accumulation in imbibed seeds can reduce reserve mobilization [26]. In addition, ABA was shown to inhibit the germination of A. thaliana by restricting the nutrient availability [26].

In conclusion, NaCl salinity may concomitantly lower the content in germination-stimulating compounds like NO−3 and growth hormones (e.g. gibberellins), increase ABA levels, and induce changes in membrane permeability, as well as in water relations [21], so that germination cannot take place. The exogenous supply with compounds including GA3, KNO3, NH+4, and fluridone could be a useful approach to improve the response of C. maritimum at the early developmental stages (i.e. germination and seedling establishment) to high salinity.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Professor Jerry Baskin (Department of Biology, University of Kentucky, USA) for his critical reading and for improving the English of the manuscript.