1 Introduction

There is a much current interest in the development of TiO2-based heterogeneous photocatalysts that operate under visible light irradiation. Traditional approaches described in literature include coupling TiO2 with organic dye sensitizers, doping with transition metals, and reduction of TiO2 by magnetron sputtering or by hydrogen [1]. Recently published studies describing TiO2 doping by nitrogen [2–8], carbon [9–12], and sulfur [9,13] indicate that this is a very promising approach for the production of catalysts operating at visible wavelengths. However, the nature and mode of action of these materials is still the subject of debate about the origin of such activity. On the basis of first principles calculations, Asahi et al. [5] concluded that visible light activity is due to nitrogen in substitutional sites of TiO2 resulting in efficient mixing with O 2p states. However, others have argued that a combination of titania reduction and/or formation an isolated N 2p narrow band [2,4,7] is principally responsible for the observed phenomena. Some studies have also reported that catalytic activity is a function of nitrogen-doping level [7], with increased nitrogen concentration beyond an optimal level producing a detrimental effect on visible light activity. Moreover, the activity was found to be dependent on the particular procedure used for nitrogen incorporation. Thus although oxidation of titanium nitride has been proposed as a method for visible light active producing N-doped TiO2 [3], others have found that creation of TiN crystal phases by high temperature TiO2 annealing in ammonia had a detrimental effect on catalyst activity [7].

To clarify the underlying phenomena that result in visible light activity of N-doped TiO2, we have developed a model system amenable to detailed studies under UHV conditions. Titania films of controlled and variable composition have been grown in situ and subsequently characterized by XPS, UPS, and AFM. Compared to single crystal surfaces of titania [14], these polycrystalline films are likely to be much more realistic models of practical dispersed titania catalysts in terms of crystallographic structure, morphology, and electronic properties. In this respect our results are entirely novel and should contribute to a better understanding of photocatalytic effects involving these interesting materials.

2 Experimental

Experiments were performed in a VG UHV system, previously described [15] which incorporated facilities for true angle resolved photoelectron spectroscopy. XP spectra were obtained with Mg Kα radiation and UPS experiments were performed with a He I source (hν = 21.2 eV). AFM topographic images were collected in air at 22 ± 1 °C with a Digital Instrument Dimension 3100 AFM with a Nanoscope IV controller in tapping mode. Ultra-sharp MikroMasch (MikroMasch Eesti OU, Estonia) silicon cantilevers (NSC15 series, 125 mm long, tip radius < 10 nm, spring constant ~ 40 N/m, resonant frequency ~300 kHz) were used. The images were collected at 512 × 512 pixels per image at a scan rate of 0.5 Hz. The captured images were analyzed with the Nanoscope image analyzing software (version 5.12r3, Veeco, CA) using first order flattening. The 10 × 10 × 1 mm polycrystalline titanium sample (Advent, 99.6%) was mechanically polished and cleaned in vacuum by Ar+ sputtering/annealing cycles until no impurities were detectable by XPS. A polycrystalline TiO2 thin film was then produced by controlled oxidation in 6 × 10−6 mbar of oxygen at 500 K for 8 min followed by cooling to 300 K in the same oxygen atmosphere.

3 Results and discussion

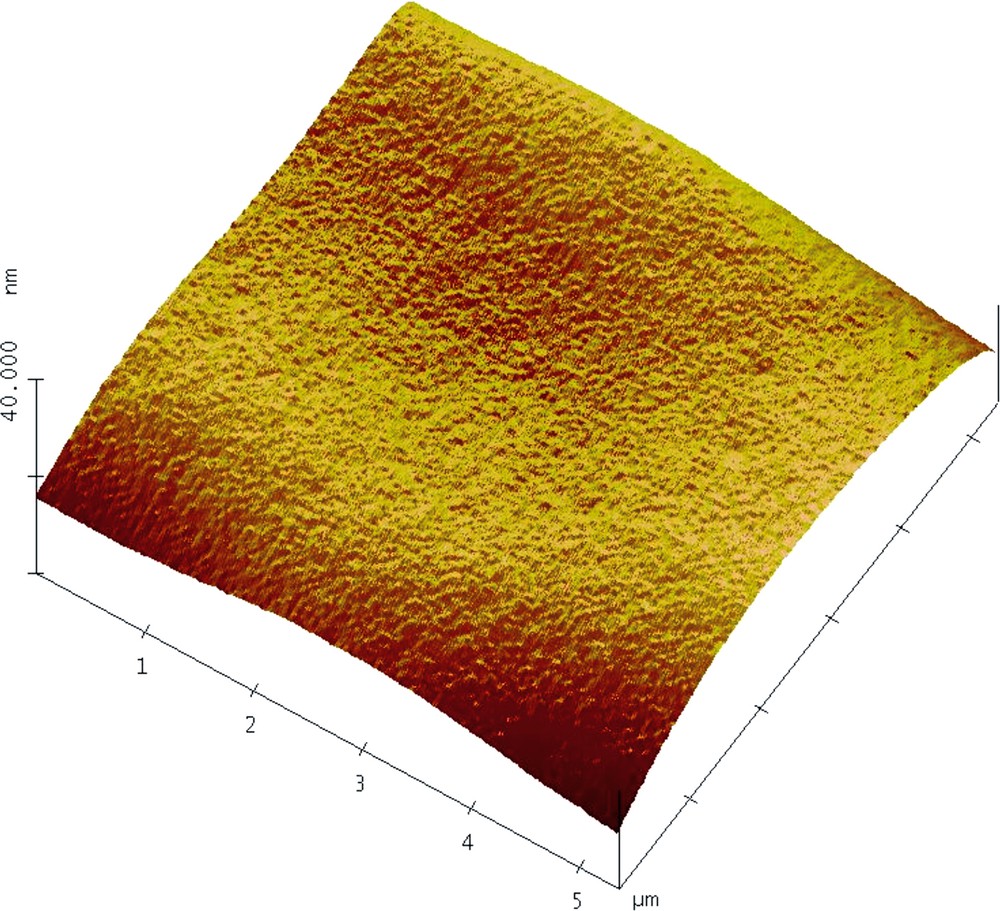

AFM revealed that the surface morphology of the polycrystalline titania thin film (Fig. 1) was dominated by featureless flat regions with a z-roughness on the order of 1 nm. A minority component of the surface consisted of nanocrystallites with z-roughness of ≥ 3 nm.

Representative AFM image of oxidized titanium film.

Two different procedures were employed for generating N-doped titania films. Firstly, nitridation of metallic Ti by exposure to N2 gas (T = 473°K, 1400 l) followed by oxidation of the resulting nitride film with O2 gas (T = 493°K, 2880 l). The second procedure involved nitrogen implantation of a titania film, prepared as described above, by bombardment with N+ ions (4 keV, fluence ~ 3 × 1015 ions per cm2). It is important to recognize that in addition to implanting N, XPS showed that this process results in partial reduction of the titania. Therefore, in order to produce a sample whose properties are relevant to those of photocatalysts working in an oxygen-containing environment, it was essential to re-oxidize this N-implanted titania according to oxidation procedure described above.

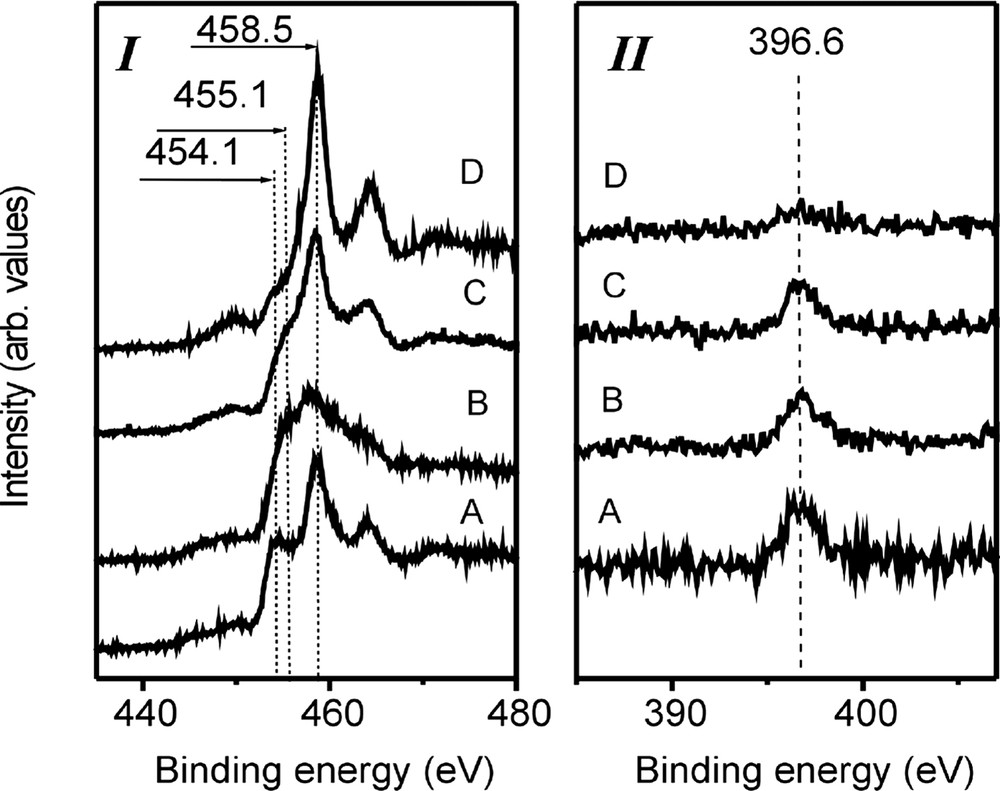

A comparison of results for the two procedures is illustrated in Fig. 2, which shows relevant Ti 2p and N 1s XP spectra. It is apparent that nitridation by nitrogen adsorption on metallic titanium followed by oxidation resulted in a somewhat lower average concentration of nitrogen in the final material (as indicated by N 1s intensities) compared to implantation by N+ bombardment. The average levels of nitrogen-doping for nitrided/oxidized and nitrogen implanted oxide films were 1.0% and 1.2%, respectively, as determined by XPS. These values are based on the approximation of uniform nitrogen distribution within the sampling depth of the XPS measurement (see below). The measured N 1s binding energy was 396.6 eV in both cases, with a slightly broader FWHM for the nitrided/oxidized sample, indicating some differences in nitrogen chemical environments depending on-doping procedure. A much more pronounced difference was observed in the corresponding Ti 2p spectra shown on Fig. 2I. The bottom spectrum (A) corresponds to a nitrided/oxidized sample; spectrum (B) was obtained after implanting nitrogen into a fully oxidized TiO2 sample; spectrum (C) was recorded after re-oxidation of sample (B) and spectrum (D) was obtained after oxidation of clean titanium foil and corresponds to fully oxidized TiO2. The corresponding N 1s spectra are shown in part II of the Fig. 2. Detailed analysis of the data indicated that N2 adsorption on the clean Ti surface resulted in a Ti 2p component shifted by about 0.7 eV and about 20% broader as compared to clean surface. This indicates development of a TiNx (x < 1) surface phase [16]. After oxidation, this component remained unshifted, indicating that the TiNx phase remains largely unaffected by the procedure (Fig. 2I, spectrum A). The only difference, a small broadening towards high binding energies, may be interpreted as a development of a Ti–N–O mixed phase at the interface between the nitrided and oxidized phases. The intensity of the TiNx emission after oxidation was attenuated by about 60%, indicative of an on-top oxide layer of thickness of ~ 1 nm. In contrast, N+ implantation (Fig. 2I, spectrum B) resulted in a development of a phase of variable composition (as it might be expected) characterized by a broad Ti 2p component shifted by 3.6 eV from the clean surface value. As is apparent from the spectrum (Fig. 2I, spectrum B) the oxide was strongly reduced (note the very low Ti4+ intensity), and the low binding energy component at 454.1 eV present in the nitrided/oxidized sample (Fig. 2I, spectrum A) was entirely absent. We attribute this behavior to development of a fairly thick oxygen-rich TiOxNy. Re-oxidation (Fig. 2I, spectrum C) restored the initial shape of the Ti 2p envelope leaving only a small residual component at ~ 456 eV due to the TiOxNy phase located at the surface, or close to the surface. These findings are supported by the UPS results described below. The observed trends provide a basis for explaining the presence/absence of photocatalytic activity of nitrogen-modified TiO2 materials. It should be noted that the position of N 1s peak in our model system (396.6 eV) is similar to that observed in powder catalyst studies (396.0 eV) [5] indicating a resemblance of nitrogen environments. In the two cases our results indicate that reports attributing visible light activity of nitrogen implanted samples [5] to interstitial N-doping appear to oversimplify the phenomenon. We have clearly shown that nitrogen implantation of titania results in a substantial reduction of the material. This suggests that visible light activity reported in some studies [5] cannot be exclusively attributed to the effect of nitrogen-doping and that other effects such as oxygen vacancies creation may be significant.

(I) Ti 2p XP spectra of (A) N2 adsorbed Ti sample after oxidation; (B) TiO2 implanted with N+; (C) TiO2 implanted with N+ after re-oxidation; (D) TiO2 sample; (II) N 1s XP spectra of (A) N2 adsorbed Ti sample after oxidation; (B) TiO2 implanted with N+; (C) TiO2 implanted with N+ after re-oxidation; (D) TiO2 sample.

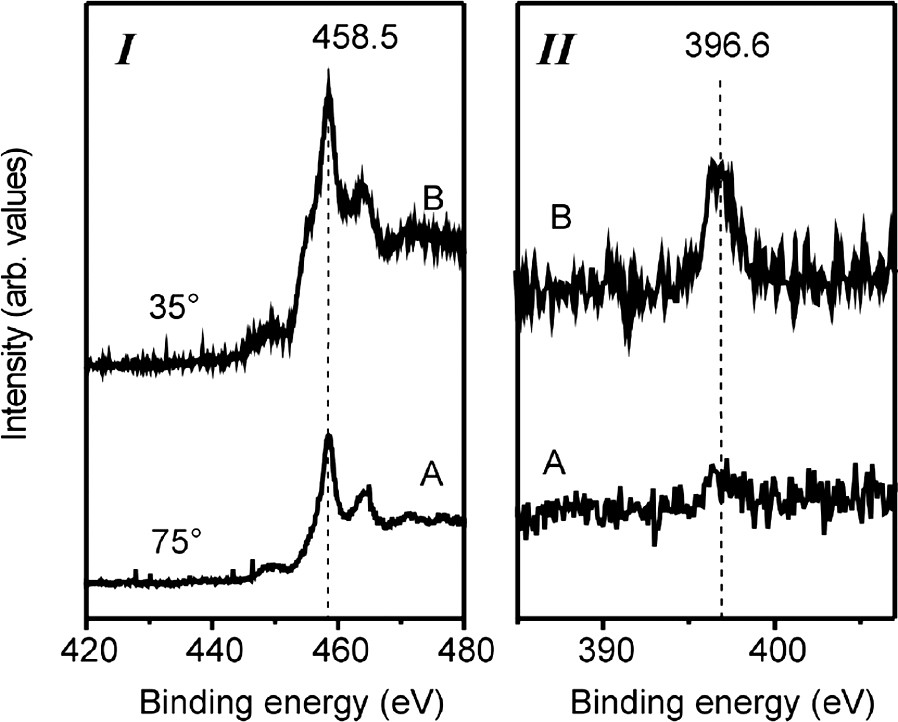

Angle resolved XP spectra provide more detailed information about the depth distributions of nitrogen and the oxidation states of titanium, and Fig. 3 shows the results for the nitrided/oxidized titania film. It is very clear (Fig. 3II) that in this material the nitrogen has migrated beneath the surface (the N 1s emission at 75° photoelectron exit is about five times less intense than that at 35° exit). Furthermore, the Ti 2p component centered at 454.1 eV and observed in 35° spectrum (Fig. 3I) is not present in the 75° spectrum, indicating that this component is well below the fully oxidized surface, in agreement with ~1 nm thickness of the oxide layer estimated above. This observation is of direct relevance to the TiN oxidation method of catalyst preparation [3], as we have now shown that this procedure produces surfaces dominated by TiO2. Therefore, negligible activity in visible region is to be expected. Metallic TiN is a poor photocatalyst, and high levels of doping can lead to transformation of TiO2 to TiN decreasing visible region photocatalytic activity [7]. The opposite process, oxidative transformation of TiN → TiO2 can lead to formation of rutile structures without forming anatase phases, thus actually reducing photoreactivity for reactions in the UV region where anatase is the most active phase [17].

(I) Angle resolved Ti 2p XP spectra of N2 adsorbed Ti sample after oxidation at various detection angles: (A) detection at 35°; (B) grazing detection at 75°. (II) Angle resolved N 1s spectra of N2 adsorbed Ti sample after oxidation at various detection angles: (A) detection at 35°; (B) grazing detection at 75°.

Corresponding angle resolved XPS results for the re-oxidized, N+ implanted titania film are shown in Fig. 4. Once again, despite a very different preparative method, it is evident that the nitrogen is located beneath the surface. However, in contrast to the previous case, the shape of the Ti 2p component does not significantly change with the emission angle, indicating that the sample composition is rather homogenous. We should also note that in the fully oxidized TiO2 sample, prepared in the absence of nitrogen, the feature at ~455 eV, attributed to TiOx (x < 2), is absent at this emission angle [15], in contrast to the N+ implanted sample. Additionally, the N 1s intensity at 75° emission angle is about 1/3 of that at 35° emission angle, indicating that nitrogen is close to the surface.

(I) Angle resolved Ti 2p XP spectra of TiO2 implanted with N+ after re-oxidation at various detection angles: (A) grazing detection at 75°; (B) detection at 35°. (II) Angle resolved N 1s spectra of TiO2 implanted with N+ after re-oxidation at various detection angles: (A) grazing detection at 75°; (B) detection at 35°.

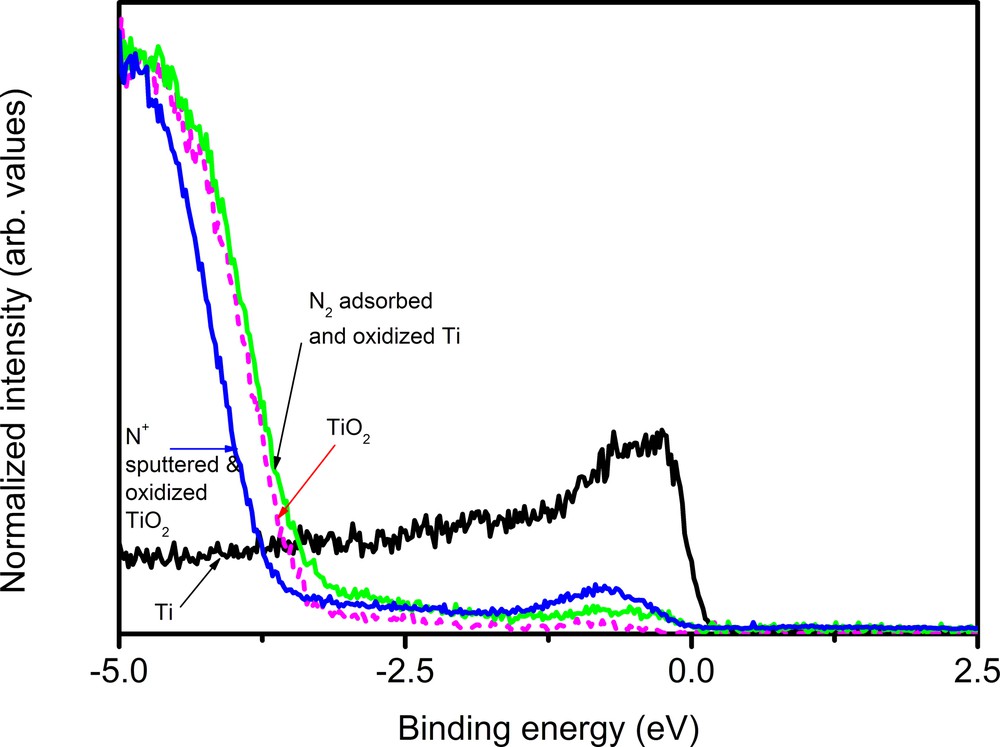

UP spectra of clean Ti, a TiO2 thin film, and both types of nitrogen-modified TiO2 films are shown in Fig. 5 while the corresponding work function and bandgap values are given in Table 1. It should be noted that the UPS/He-I sampling depth (0.5 nm) is significantly less than that for Ti 2p/N 1s photoelectrons (Ek ~ 800 eV for Mg Kα; sampling depth ~ 1.5 nm). For the pure TiO2 film, the valence band consists of features derived from O 2p orbitals whereas the lower portion of empty conduction band is composed primarily of Ti 3d orbitals [18]. The observed band gap of 3.36 eV and the measured work function of 5.35 eV are in excellent agreement with literature values reported for anatase form of TiO2 [15,18] This is an important observation because it is generally found that anatase is a much more effective photocatalyst than rutile [17]. We may therefore conclude that our experiments were carried out on the catalytically relevant form of TiO2. The nitrided/oxidized film exhibited the UP spectra, bandgap and work function values very similar to those of the original TiO2 surface – in very good accord with the XPS data showing that the surface region of the film contains mainly Ti4+. In contrast, the N+ implanted, re-oxidized film had a smaller work function (4.66 eV), with the onset of the oxygen-derived valence features shifted towards higher binding energies by 0.3 eV. It also had a much smaller bandgap (0.1 eV) as compared to TiO2 (3.36 eV). The dramatically decreased bandgap is associated with the photoemission feature that shows a maximum at ~ 0.7 eV below EF, extending to 1.3 eV below EF. This feature may be assigned to a partial occupation of the Ti 3d band (3dx, x > 0). Similar observations have been reported for bulk TiOx (x < 2) where a decrease in work function, partial occupation of the Ti 3d band extending to 1.5 eV below EF, and a shift of the O 2p band to higher binding energies [19,20] were found. This partial filling of the Ti 3d band cannot be unequivocally assigned to the presence of oxygen vacancies as similar emission is observed in the case of non-stoichiometric TiN0.5 [16].

UPS spectra of Ti, TiO2, and nitrogen-modified TiO2 samples.

Bangap and work function values of the samples as determined by UPS

| Sample | Bandgap (eV) | Work function (eV) |

| TiO2 | 3.36 | 5.35 |

| TiO2 N+ sputtered and oxidized | 0.1 | 4.66 |

| Ti N2 adsorbed and oxidized | 3.29 | 5.35 |

| Ti | 0 | 3.59 |

To rationalize our observations, two distinct scenarios resulting from two different methods of nitrogen incorporation into TiO2 may be proposed. The development of a titanium nitride thin film for N2 adsorbed/oxidized titanium sample resulted in substantial changes in XPS features attributed to non-stoichiometric titanium nitride. UPS, a more surface sensitive technique than XPS, confirmed development of TiO2 overlayer after subsequent oxidation. UPS results also indicated that this overlayer has the character of fully oxidized TiO2 with titanium nitride species having negligible contribution to the spectra. On the other hand, in accord with XPS results, N+ implanted samples developed titanium oxynitride and/or reduced titania species much closer to the surface, translating into significant changes in bandgap and work functions values as determined by UPS. It is apparent that the effects of nitrogen incorporation strongly depend on preparation conditions and are a complex function of titanium oxidation state and nitrogen species distribution throughout the sample depth. These parameters can strongly affect the photocatalytic activity of the resulting materials in the visible region. The development of optimized and reproducible methods of N incorporation is an essential requirement for the production of reliable, stable and visible light active photocatalyst. Possible future strategies include co-dosing O2 and N2 using reactive gas pulsing techniques [21], for example.

4 Conclusions

1. Polycrystalline, stoichiometric anatase thin films may be grown by controlled oxidation of Ti metal under vacuum conditions and doped with nitrogen by N+ bombardment. The resulting material is substantially reduced, re-oxidation resulting in the incorporated nitrogen being located close to the surface.

2. An alternative chemical route, nitridation of the metal followed by oxidation, results in an anatase film with a similar degree of N-doping. In this case, however, the nitrogen is located well below the surface.

3. The results imply that earlier interpretations of the origin of visible light activity of nitrogen-doped photocatalysts may be oversimplified or even incorrect. In particular, the role of oxygen vacancies, inevitably introduced by N+ implantation, should be given more significance.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported under Research Grant GR/R03082/01 awarded by the UK Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council. A.O. thanks the Environmental Research and Education Foundation for the award of an International Scholarship, and Schlumberger Cambridge Research for additional financial support.