1 Introduction

The first one-dimensional systems displaying ferrimagnetic behaviour were designed, prepared and investigated during the decade of the 1980s [1–9], and they certainly helped to stimulate progress in the field of molecular magnetism [10]. Most of these systems were mainly based on CuII and MnII metal ions [1–9], although subsequent studies incorporated also organic radicals [11,12].

The magnetic behaviour of ferrimagnetic chains is governed, at least in part, because the antiferromagnetic interaction between distinct spin carriers cannot completely cancel the alternating magnetic moments, thus inducing a short-range magnetic order [11]. Hence, to get this type of systems, it seems a good strategy to make use of the combination of couples of paramagnetic 3d and 5d metal ions exhibiting different magnetic spins.

In this way, in 1999, it was reported the first ferrimagnetic chain based on CuII (3d9 ion with S = 1/2) and ReIV (5d3 ion with S = 3/2), which was obtained with the [ReCl4(ox)]2− metalloligand (ox = oxalate anion), thus demonstrating that the choice of this pair of 3d/5d ions was a promising synthetic route to get ferrimagnetic systems [13]. Indeed, four studies dealing with ferrimagnetic chains based on CuII and ReIV were later reported [14–17], by using the building block [ReCl4(ox)]2− and as terminal ligands towards the CuII ion the organic macrocycles N-dl-5,7,7,12,14,14-hexamethyl-1,4,8,11-tetraazacyclotetradeca-4,11-diene [14] and N-meso-5,12-Me2-7,14-Et2-[14]-4,11-dieneN4 [15,17], or the 2-(2′-pyridyl)imidazole ligand [16]. In all cases, the alternating CuII and ReIV ions exhibit antiferromagnetic coupling between them and the thus obtained chains behave as ferrimagnetic compounds at very low temperatures [13–17].

More recently, the bromo derivative [ReBr4(ox)]2− metalloligand has been studied and used to prepare polynuclear complexes with paramagnetic 3d and 4f ions [18–23], some of them behaving as single-molecule magnet [20]. However, no ferrimagnetic chain containing the [ReBr4(ox)]2− precursor has been reported so far.

As a continuation of our investigation on the magnetic properties of rhenium(IV)-based compounds, we report herein the synthesis and magnetostructural characterisation of a novel copper(II)–rhenium(IV) compound of formula {[ReIVBr4(μ-ox)CuII(pyim)2]·MeCN}n (1) [ox = oxalate anion, pyim = 2-(2′-pyridyl)imidazole]. Compound 1 is the third reported copper(II)–rhenium(IV) complex obtained with the [ReBr4(ox)]2− precursor and the first [ReBr4(ox)]2−-containing compound to exhibit magnetic behaviour typical of ferrimagnetic chain.

2 Experimental section

2.1 Materials

All manipulations were performed under aerobic conditions, using chemicals as received from Sigma–Aldrich. Type 4 molecular sieves were used to dry the CH3CN and CH3NO2 solvents before use. The precursor (NBu4)2[ReBr4(ox)] was prepared following the synthetic method described in the literature [18,23].

2.2 Synthesis

2.2.1 {[ReBr4(μ-ox)Cu(pyim)2]·MeCN}n (1)

(NBu4)2[ReBr4(ox)] (53.9 mg, 0.05 mmol) was dissolved in 20 mL of a CH3NO2/CH3CN (4:1, v/v) mixture and was added dropwise to a solution of Cu(NO3)2·3H2O (12.1 mg, 0.05 mmol) and 2-(2′-pyridyl)imidazole (14.5 mg, 0.10 mmol) dissolved in the same solvent mixture (20 mL). The resulting pale green solution was left to evaporate at room temperature. Dark green crystals of 1 were obtained in 2 weeks and were suitable for X-ray diffraction (XRD) studies. Yield: ca. 60%. Found: C, 24.4; H, 1.6; N, 9.4. Calcd for C20H17N7O4Br4CuRe (1): C, 24.3; H, 1.7; N, 9.9%. X-ray microanalysis gave Re/Cu and Re/Br molar ratios of 1:1 and 1:4, respectively. IR peaks (KBr pellets/cm−1): 3358 (m), 3129 (m), 2930 (w), 1704 (vs), 1651 (s), 1619 (m), 1570 (m), 1549 (m), 1500 (m), 1475 (s), 1404 (w), 1366 (s), 1300 (w), 1161 (m), 1098 (m), 1020 (w), 970 (w), 931 (w), 890 (w), 800 (m), 786 (m), 747 (m), 700 (m), 659 (w), 542 (m), 460 (w).

2.3 Physical measurements

Elemental analysis (C, H, N) were performed using a CE Instruments EA 1110 CHNS analyser. Infrared spectra were recorded using a Thermo-Nicolet 6700 FT-IR spectrophotometer in the 4000–400 cm−1 region. The Re/Cu and Re/Br molar ratios were analysed using a Philips XL-30 scanning electron microscope equipped with a system of X-ray microanalysis from the Central Service for the Support to Experimental Research at the University of Valencia. Magnetic susceptibility measurements of 1 were carried out with a Quantum Design SQUID magnetometer in the temperature range 1.9–300 K and under an applied magnetic field of 0.1 T. All of the experimental magnetic data were corrected for the diamagnetic contributions of the constituent atoms in 1, through the Pascal's constants [24], and also for the sample holder.

2.4 Crystallographic data collection and structure determination

Powder XRD measurements were performed using a PANalytical Empyrean diffractometer with a hybrid monochromator (CuKα1 radiation), a PIXcel detector and a capillary sample holder. XRD data of a single crystal of 1, with dimensions 0.42 × 0.18 × 0.15, were collected using a Bruker D8 Venture diffractometer with PHOTON II detector and using monochromatized MoKα radiation (λ = 0.71073 Å). The structure was solved by standard direct methods and subsequently completed by Fourier recycling using SHELXTL [25–28]. The final full-matrix least-squares refinements on F2, minimising the function Σw(|Fo| − |Fc|)2, reached convergence with values of the discrepancy indices given in Table 1. All non-hydrogen atoms were refined anisotropically. All hydrogen atoms of the MeCN molecule were set in calculated positions and refined as riding atoms. Graphical manipulations were performed using DIAMOND [29]. Main interatomic bond lengths and angles for 1 are given in Table 2. CCDC 1885666 contains the supplementary crystallographic data for compound 1.

Crystal data and structure refinement for {[ReBr4(μ-ox)Cu(pyim)2]·MeCN}n (1).

| CCDC | 1885666 |

| Formula | C20H17Br4N7O4CuRe |

| Formula weight | 988.8 |

| Crystal system | Orthorhombic |

| Space group | Pbca |

| Z | 8 |

| a (Å) | 18.977(4) |

| b (Å) | 14.282(3) |

| c (Å) | 19.809(5) |

| α (°) | 90 |

| β (°) | 90 |

| γ (°) | 90 |

| V (Å3) | 5369(2) |

| Dc (g cm−3) | 2.449 |

| F(000) | 3696 |

| μ (mm−1) | 11.293 |

| Goodness-of-fit on F2 | 1.415 |

| R1 [I > 2σ(I)]a | 0.0831 |

| wR2b,c | 0.1958 |

a R1 = Σ||Fo| − |Fc||/Σ|Fo|.

b wR2 = {Σ[w(Fo2 − Fc2)2]/[(w(Fo2)2]}1/2.

c w = 1/[σ2(Fo2) + (aP)2 + bP] with P = [Fo2 + 2Fc2]/3.

Selected bond lengths (Å) and angles (°) for 1.

| Re(1)O(1) | 2.052(1) |

| Re(1)O(2) | 2.057(1) |

| Re(1)Br(1) | 2.499(1) |

| Re(1)Br(2) | 2.468(1) |

| Re(1)Br(3) | 2.458(1) |

| Re(1)Br(4) | 2.491(1) |

| Cu(1)O(4) | 2.682(1) |

| Cu(1)N(1) | 1.995(1) |

| Cu(1)N(2) | 1.994(1) |

| Cu(1)N(4) | 2.056(1) |

| Cu(1)N(5) | 1.941(1) |

| O(1)Re(1)O(2) | 78.9(4) |

| O(1)Re(1)Br(2) | 92.4(3) |

| O(2)Re(1)Br(2) | 171.1(3) |

| O(1)Re(1)Br(3) | 172.7(3) |

| O(2)Re(1)Br(3) | 93.8(3) |

| Br(2)Re(1)Br(3) | 94.9(1) |

| O(1)Re(1)Br(4) | 87.5(3) |

| O(2)Re(1)Br(4) | 88.5(3) |

| Br(2)Re(1)Br(4) | 93.2(1) |

| Br(3)Re(1)Br(4) | 92.1(1) |

| O(1)Re(1)Br(1) | 89.4(1) |

| O(2)Re(1)Br(1) | 85.8(3) |

| Br(2)Re(1)Br(1) | 92.2(1) |

| Br(3)Re(1)Br(1) | 90.3(1) |

| Br(4)Re(1)Br(1) | 173.9(1) |

| N(5)Cu(1)N(2) | 99.3(5) |

| N(5)Cu(1)N(1) | 166.4(5) |

| N(2)Cu(1)N(1) | 83.1(5) |

| N(5)Cu(1)N(4) | 82.0(5) |

| N(2)Cu(1)N(4) | 157.8(5) |

| N(1)Cu(1)N(4) | 100.8(5) |

| C(3)N(1)Cu(1) | 132.9(1) |

| C(7)N(1)Cu(1) | 113.3(10) |

| C(8)N(2)Cu(1) | 110.0(10) |

| C(10)N(2)Cu(1) | 145.7(12) |

| C(11)N(4)Cu(1) | 126.8(11) |

| C(15)N(4)Cu(1) | 113.0(11) |

| C(16)N(5)Cu(1) | 111.4(10) |

| C(18)N(5)Cu(1) | 140.2(11) |

| O(4)C(1)O(1) | 122.8(14) |

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Crystal structure of {[ReBr4(μ-ox)Cu(pyim)2]·MeCN}n (1)

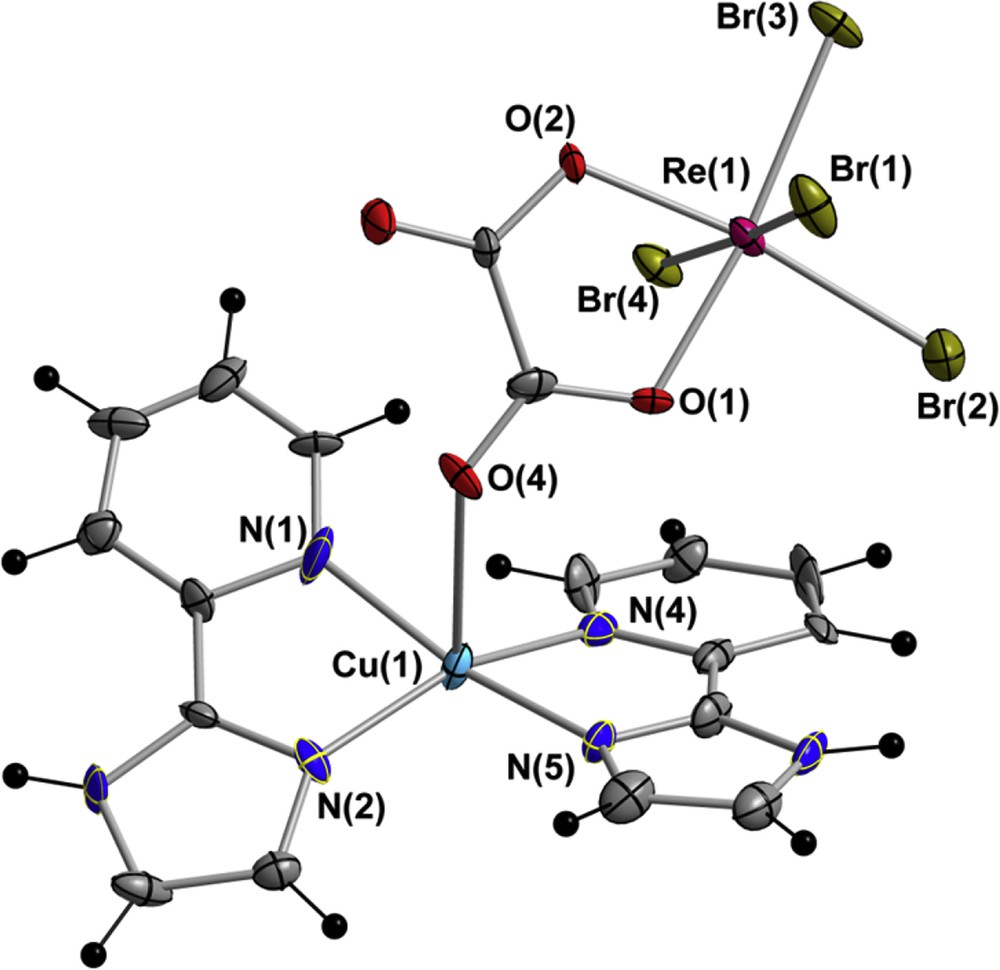

Compound 1 crystallises in the orthorhombic system with space group Pbca (Table 1). The crystal structure is made up of [Cu(pyim)2]2+ cations and [ReBr4(ox)]2− anions, which are mainly linked through alternating oxalato and bromo bridges generating a CuIIReIV chain of repeating [ReBr4(μ-ox)Cu(pyim)2] units. A MeCN molecule along with a dinuclear [ReBr4(μ-ox)Cu(pyim)2] complex forms the asymmetric unit in 1. Although selected bonds lengths and angles are listed in Table 2, a perspective drawing showing the metal-based ions in 1 is given in Fig. 1.

Molecular structure of the dinuclear [ReIVBr4(μ-ox)CuII(pyim)2] unit showing the atom numbering of the CuII and ReIV metal ions along with those of their chromophores in compound 1. Thermal ellipsoids are drawn at the 50% probability level.

There exist a couple of significant structural differences between 1 and the previously reported [ReCl4(μ-ox)Cu(pyim)2] (2) and [ReBr4(μ-ox)Cu(bpy)2] (3) compounds that we would like to point out [16,19]. Compounds 2 and 3 crystallise in the monoclinic system with space group P21/n, but besides that, 2 and 3 do not contain solvent molecules of crystallisation. Remarkably, the coordination of the oxalate group to the CuII ion is through the O(1) atom in 2, whereas it is by means of the O(4) atom in 1 and 3. Only in 3 there exist short halogen⋯halogen contacts connecting the adjacent CuIIReIV chains [19].

In 1, rhenium(IV) ion is six-coordinate by four bromide anions and two oxygen atoms in a distorted octahedral geometry. The main cause of such a distortion is the reduced bite angle of the oxalate group [the value of the O(1)Re(1)O(2) angle is 78.9(1)°], which exhibits bidentate and monodentate bridging modes towards the ReIV and CuII ions, respectively. The O(1), O(2), Br(2) and Br(3) set of atoms constitute the best equatorial plane around the ReIV ion, the largest deviation from planarity being 0.070 Å for O(2). The average value of the ReIVBr [2.479(1) Å] and ReIVO [2.055(1) Å] bond lengths, and also the bond angles, found in 1 are in agreement with those previously reported for complexes containing the anionic [ReBr4(ox)]2− entity [18–22].

Each CuII ion in 1 is mainly five-coordinate and bonded to four nitrogen atoms from two pyim molecules and an oxygen atom from the oxalate group of the closer [ReBr4(ox)]2− anion, in a distorted square pyramidal geometry. The CuIIO bond length is 2.682(1) Å and the average value of the CuIIN bond lengths is 1.997(1) Å. Nevertheless, having into account the Br(1a) ion that would occupy a sixth position generating the one-dimensional motif [the Cu(1)⋯Br(1a) distance is ca. 3.23 Å; (a) = x, 1/2 − y, 1/2 + z], the CuII ion could also be seen in a very distorted octahedral environment, as previously described in similar chloro-derivative CuIIReIV systems [13,16].

The intramolecular CuII⋯ReIV distance through the oxalato bridge is 5.457(1) Å, whereas this intermetallic distance through the bromo bridge is somewhat shorter [Cu(1a)⋯Re(1) distance of 5.263(1) Å; (a) = x, 1/2 − y, 1/2 + z]. The average CC and CN bond length values of the pyim ligand show the expected values for this molecule when coordinated to a metal ion [30–67].

In the crystal packing of 1, the [ReBr4(μ-ox)Cu(pyim)2] units are arranged helicoidally forming chains that grow along the c-axis direction (Fig. 2). These CuIIReIV chains are extended to layers, on the crystallographic bc plane (Fig. 3), by means of bifurcated hydrogen-bonding interactions between oxalate and NH groups of coordinated pyim ligands [the N(6)⋯O(3b) and N(6)⋯O(4b) distances are 2.87(2) and 2.93(2) Å, respectively; (b) = 3/2 − x, 1 − y, −1/2 + z]. Likewise, π⋯π type interactions between the aromatic rings of neighbouring pyim ligands connect the CuIIReIV chains along the crystallographic ab plane (the shortest intercentroid distance being approximately 3.42 Å). The value of the shortest intermolecular CuII⋯ReIV distance between adjacent chains is 8.822(2) Å [Cu(1)⋯Re(1c), (c) = 3/2 − x, −y, −1/2 + z], whereas the shortest intermolecular CuII⋯CuII and ReIV⋯ReIV distances are 7.385(3) and 9.161(2) Å [Cu(1)⋯Cu(1d) and Re(1)⋯Re(1d), (d) = 3/2 − x, −1/2 + y, z], respectively.

Perspective view showing the one-dimensional motif of 1 along the a-axis direction. Hydrogen atoms and MeCN molecules have been omitted for clarity. Colour code: pink, Re; pale blue, Cu; green, Br; red, O; blue, N; black, C.

View along the crystallographic a axis of a fragment of the crystal packing of 1 showing the arrangement of [Cu(pyim)2]2+ cations and [ReBr4(ox)]2− anions linked through oxalato and bromo bridges. Hydrogen atoms and MeCN molecules have been omitted for clarity. Colour code: pink, Re; pale blue, Cu; green, Br; red, O; blue, N; black, C.

In addition, weak CH⋯Br interactions that vary in the range 3.72–3.78 Å link parallel planes and contribute to stabilising the supramolecular structure of 1.

Finally, the phase purity of the bulk sample of 1 was confirmed through powder XRD patterns (Fig. 4).

Plot of the simulated (top) and experimental XRD (bottom) patterns profile in the 2θ/° range 0–45° for 1.

3.2 Magnetic properties

Direct current magnetic susceptibility measurements were carried out on a microcrystalline sample of 1 in the 1.9–300 K temperature range and under an external magnetic field of 0.1 T. The χMT versus T plot (χM being the molar magnetic susceptibility per CuIIReIV pair) of 1 is shown in Fig. 5. At room temperature the χMT value is 1.96 cm3 mol−1 K, which is very close to that expected for a pair of uncoupled CuII (3d9, S = 1/2 with g = 2.2) and ReIV (5d3, S = 3/2 with g = 1.8) ions [14–18]. Upon cooling, the χMT value decreases slowly with decreasing temperature, more abruptly at approximately 50 K, reaching a minimum value of 0.50 cm3 mol−1 K at 2.0 K. Then, the χMT value increases giving a final value of 0.58 cm3 mol−1 K at 1.9 K. No maximum of the magnetic susceptibility is detected in the χM versus T plot. The magnetic behaviour observed at higher temperatures would be because of the large zero-field splitting of the ReIV ion, together with antiferromagnetic interaction between the ReIV and CuII centres, whereas the final increases in the χMT value at very low temperatures would account for a ferrimagnetic behaviour for 1 [13–16].

Thermal variation of the χMT (o) product for 1. The solid line is the calculated curve and the inset shows a detail of the low temperature range (see text).

The field dependence of the molar magnetisation (M) plot for 1 at 2.0 K is given in Fig. 6, which exhibits a continuous increase in M with the applied magnetic field and neither saturation nor hysteresis loop was observed. The lack of saturation of M at this temperature is likely because the applied magnetic field would overcome the weak intrachain antiferromagnetic interaction [13,16]. The M versus H plot also supports the presence of antiferromagnetic interactions in 1, given that the maximum value of M per CuIIReIV pair (ca. 1.19 μB) is smaller than that of the mononuclear [ReBr4(ox)]2− complex isolated as its tetra-n-butylammonium salt (ca. 1.50 μB) [23].

| (1) |

| (2) |

Plot of the variable-field magnetisation versus applied field at 2.0 K for 1 (see text).

Taking into account both the structural description of 1 (see above) and the presence of a minimum at very low temperature in the χMT versus T plot, we can consider that compound 1 behaves as a ferrimagnetic chain [13–16]. Thus, to analyse the magnetic properties of 1, the experimental magnetic susceptibility data have been treated through Eqs 1 and 2 and the following spin Hamiltonian (Eq 3):

| (3) |

The approach that we have used to fit the experimental data consists in assuming that the magnetic susceptibility is given by that of the 4A2g term (ground state for a d3 ion in an octahedral environment), including the zero-field splitting, and modulated by a factor predicted from the Ising model of the magnetic exchange with the parameters J and j that would be assigned to the magnetic exchange pathways of the alternating oxalato and bromo bridges, respectively (and defined as indicated in Eqs 1 and 2) [16,17]. This is possible because the magnetic susceptibility of 1 in the high temperature region may be described by two contributions: one from the 4A2g term of the ReIV ion and the other from the uncoupled CuII ion. In the low temperature region it would be described as a chain of SRe = Seff = 1/2 with different local gCu and gRe Landé factors [13–16].

To avoid overparameterisation, we have also assumed that g = g// = g⊥ for the CuII and ReIV ions. This approach has previously been used for fitting the magnetic data of similar heterometallic CuIIReIV chains [13–16,58]. A least-squares fit of the experimental data in the 1.9–300 K temperature range afforded the following parameters for 1: J = −6.3, j = −5.4, gCu = 2.25, gRe = 1.87, and |DRe| = 64.2 cm−1 with R = 6.4 × 1-0−5 {R being the agreement factor defined as Σi[(χMT)obs(i) − (χMT)calc(i)]2/Σi[(χMT)obs(i)]2}. As shown in Fig. 5, the theoretical curve for 1 (red solid line) matches quite well with the experimental magnetic data in the studied temperature range. The values of the J and j magnetic exchanges that we have obtained by this approach are referred to an Seff = 1/2 and aiming at comparing them with the DRe value (which is referred to a real SRe = 3/2), they should be reduced by a factor of about 3/5 (3J/5 = −3.8 cm−1 and 3j/5 = −3.2 cm−1), as previously reported [13,16,58]. The calculated values for the gCu, gRe and DRe parameters are in agreement with those previously computed for similar one-dimensional CuIIReIV systems [13–16,58]. The calculated values of the J and j magnetic exchanges support antiferromagnetic interactions between the ReIV and CuII centres across the two magnetic pathways, that is, through the alternating oxalato and bromo bridges in 1. According to the orthogonality of the involved magnetic orbitals [eg for CuII and t2g for ReIV], a priori, a ferromagnetic exchange would be expected. However, this orthogonality is broken because of the asymmetry of the bridges and the distorted coordination geometry of the Cu(II) ion, resulting in a very poor overlap of the magnetic orbitals and, hence, in a weak antiferromagnetic exchange between these metal ions.

Despite showing a chain motif in its crystal structure, compound 3 behaves magnetically as a tetranuclear [ReIV2CuII2] species [19]. Compound 3 does not exhibit behaviour of ferrimagnetic chain given that contains in their crystal lattice significant Re–Br⋯Br–Re interactions (Br⋯Br separation of ca. 4.8 Å) between adjacent ReIVCuII chains. These intermolecular interactions in the rhenium(IV) chemistry are usually very strong and can easily overcome the intramolecular ones, accounting for the magnetic behaviour observed in the χMT versus T variation [68]. Nevertheless, this fact has not been reported for ferrimagnetic chains based on other 5d metal ions [69].

As far as we know, compound 1 is the first system containing the [ReBr4(ox)]2− metalloligand to exhibit magnetic behaviour of ferrimagnetic chain and, therefore, any comparison would be precluded. Nonetheless, we have tried to compare our results with those obtained for the previously studied CuIIReIV chains based on the chloro-derivative [ReCl4(ox)]2− complex [13–17]. Thus, we have plotted the J values versus the ReIV⋯CuII distances and the Re–X–Cu angle (°) (X = Cl and Br) for ferrimagnetic CuIIReIV chains (Table 3). As shown in Fig. 7, there exists a certain trend in these systems: when the Re···Cu separation shortens and the Re–X–Cu angle decreases, the value of the antiferromagnetic coupling also decreases (red solid line in Fig. 7). Although we cannot talk about a magnetostructural correlation, given that more data of CuIIReIV systems would be needed to complete the study in detail, this trend could help at least to design new ferrimagnetic CuIIReIV compounds and similar systems, having into account the high magnetic anisotropy that ReIV ion exhibits [70–75].

Selected magnetostructural parameters for ferrimagnetic ReIVCuII chains.a

| Compound | Space group | d(Re⋯M) (Å) | J, j (cm−1) | ǀDǀ (cm−1) | gRe | gCu | Ref. |

| [ReCl4(μ-ox)Cu(bpy)2] | P21/n | 4.798, 4.658 | −25.0, −13.0 | 53.0 | 1.84 | 2.17 | [13] |

| [ReCl4(μ3-ox)Cu(L1)] | P21 | 5.568, 5.870 | −3.4, NA | 49.6 | 1.91 | 2.27 | [14] |

| [ReCl4(μ-ox)Cu(L2)] | Pī | 4.684, 4.718 | −18.1, −0.7 | 63.0 | 1.89 | 2.20 | [15] |

| [ReCl4(μ-ox)Cu(pyim)2] | P21/n | 4.544, 4.805 | −7.8, −6.0 | 54.8 | 1.80 | 2.29 | [16] |

| [ReCl4(μ-ox)Cu(L2)] | P21/c | 6.030, 4.769 | −14.2, −8.7 | 54.5 | 1.81 | 2.24 | [17] |

| [ReBr4(μ-ox)Cu(pyim)2] | Pbca | 5.457, 5.263 | −6.3, −5.4 | 64.2 | 1.87 | 2.25 | This work |

a bpy = 2,2′-bipyridine; pyim = 2-(2′-pyridyl)imidazole; L1 = N-dl-5,7,7,12,14,14-hexamethyl-1,4,8,11-tetraazacyclotetradeca-4,11-diene; L2 = N-meso-5,12-Me2-7,14-Et2-[14]-4,11-dieneN4; NA = not available.

Dependence of the J parameter (cm−1) on the ReIV···CuII distance (Å) and the ReXCu angle (°) for ferrimagnetic CuIIReIV chains. The solid line represents the linear best fit.

4 Conclusions

We have reported the synthesis, characterisation and magnetic properties of a novel CuIIReIV compound of formula {[ReIVBr4(μ-ox)CuII(pyim)2]·MeCN}n (1) [ox = oxalate anion, pyim = 2-(2′-pyridyl)imidazole]. The analysis of the magnetic properties of 1 through variable-temperature magnetic susceptibility data revealed a magnetic behaviour typical of ferrimagnetic chain, which is consistent with its crystal structure. Remarkably, compound 1 is the first reported copper(II)–rhenium(IV) complex obtained with the [ReBr4(ox)]2− metalloligand that exhibits such a magnetic behaviour.

In addition, by comparing our results with those reported in the literature, we have observed a trend associated with the family of ferrimagnetic CuIIReIV chains, although more systems would be needed to complete a study that establishes a proper magnetotructural correlation.

Acknowledgements

Financial support from the Spanish Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades (projects MDM-2015-0538 and CTQ2016-75068-P) and “Ramón y Cajal” Programme is gratefully acknowledged. The authors wish to thank Prof. Michel Verdaguer for his superb guidance and continuous support to the younger researchers throughout his scientific career.