1 Introduction

The multicomponent reaction (MCR) has become an important area of research in organic, medicinal, and combinatorial chemistry [1–4]. Its simplicity and atomic economy of the process offer rapid and easy access to complex N-heterocyclic systems in a single eco-friendly synthetic operation [5].

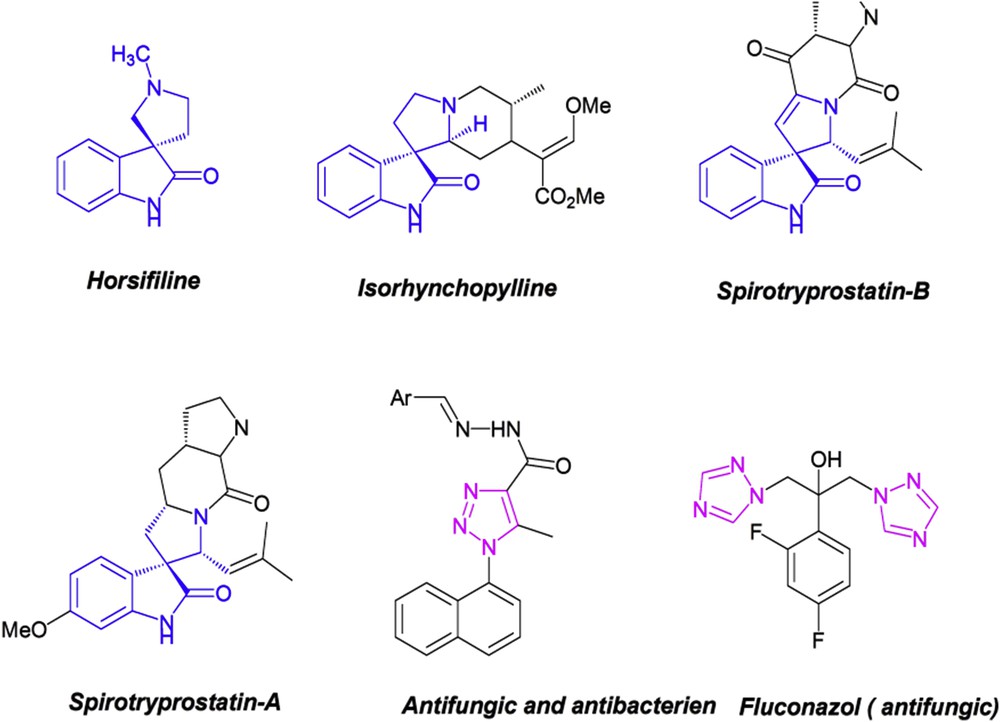

Spirooxindole–pyrrolidines are an important subset of the oxindole-based molecules [6], which represent attractive targets in the organic synthesis because of their highly marked biological activities such as antimicrobial [7], antitumoral [8], anti-inflammatory [9], anti-HIV [10], and anticancer properties [11]. On the other hand, triazole and their derivatives display a wide range of biological activities incorporating anticancer [12], antitubercular [13], antimicrobial [14], antifungal [15], and antibacterial [16,17] activities that are also found in drugs like fluconazole [18] (Fig. 1).

Representative examples of biologically active molecules containing a spirooxindole and triazole core.

In view of the biological importance of the oxindole scaffold and to increase the breadth of accessible library members of this family, it was of considerable interest to develop novel structures including both the oxindole structure and the five-membered ring hoping that such a combination could be more biologically effective.

In the last decade, multicomponent 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition reactions of azomethine ylides derived from isatin and α-amino acids with dipolarophiles have been emerged as a fascinating and powerful tool for the synthesis of spirooxindolopyrrolidine [7,11] and spirooxindolopyrrozilidine [19] derivatives in a highly regio- and stereoselectivity fashion. For example, P.T. Perumal et al. have demonstrated that spirooxindole–pyrrolidine compounds, which exhibit an anticancer activity, are accessible by the reaction of azomethine ylides generated from isatin and sarcosine or thioproline with the dipolarophile 3-(1H-imidazol-2-yl)-2-(1H-indole-3-carbonyl) acrylonitrile [11]. The group of V.V. Lipson has developed a regioselective synthesis of spirooxindolopyrrolidines and pyrrolizidines via three-component reactions of acrylamides and aroylacrylic acids with isatin and α-amino acids [19].

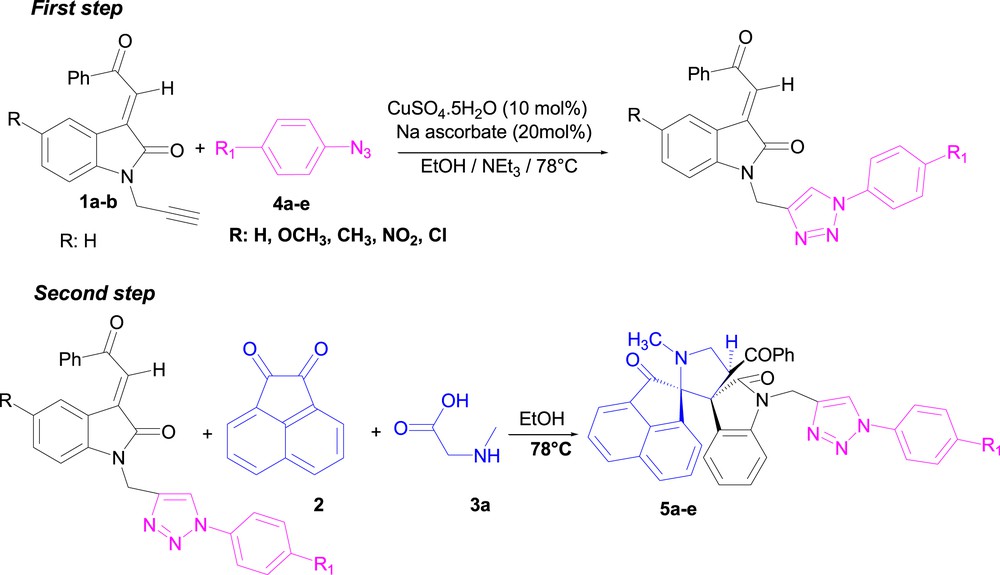

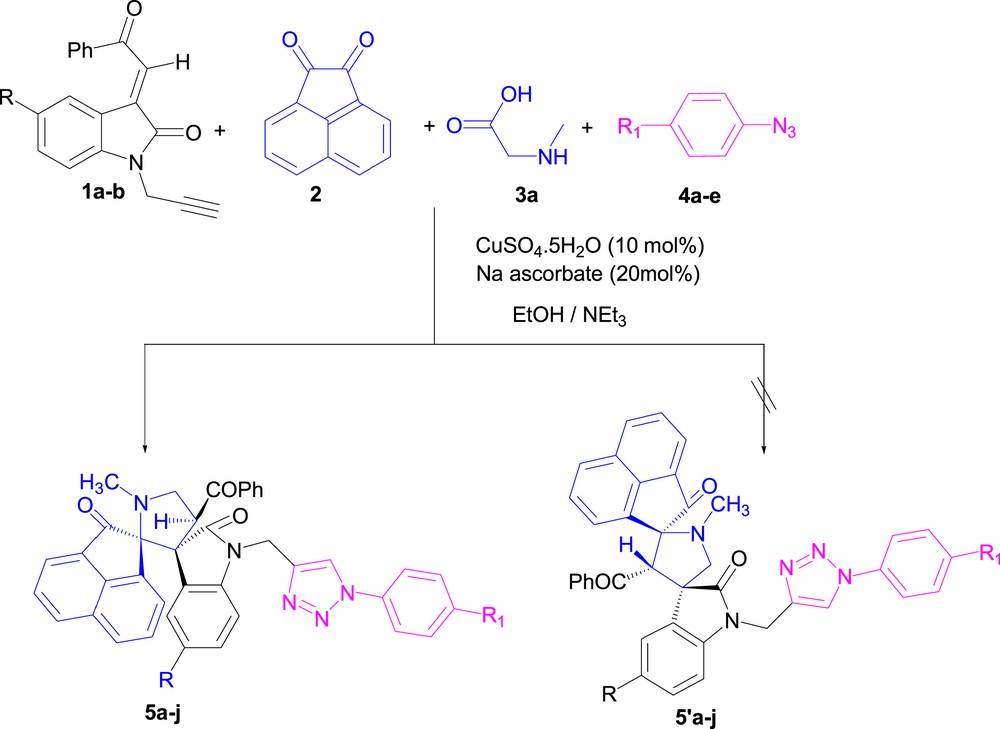

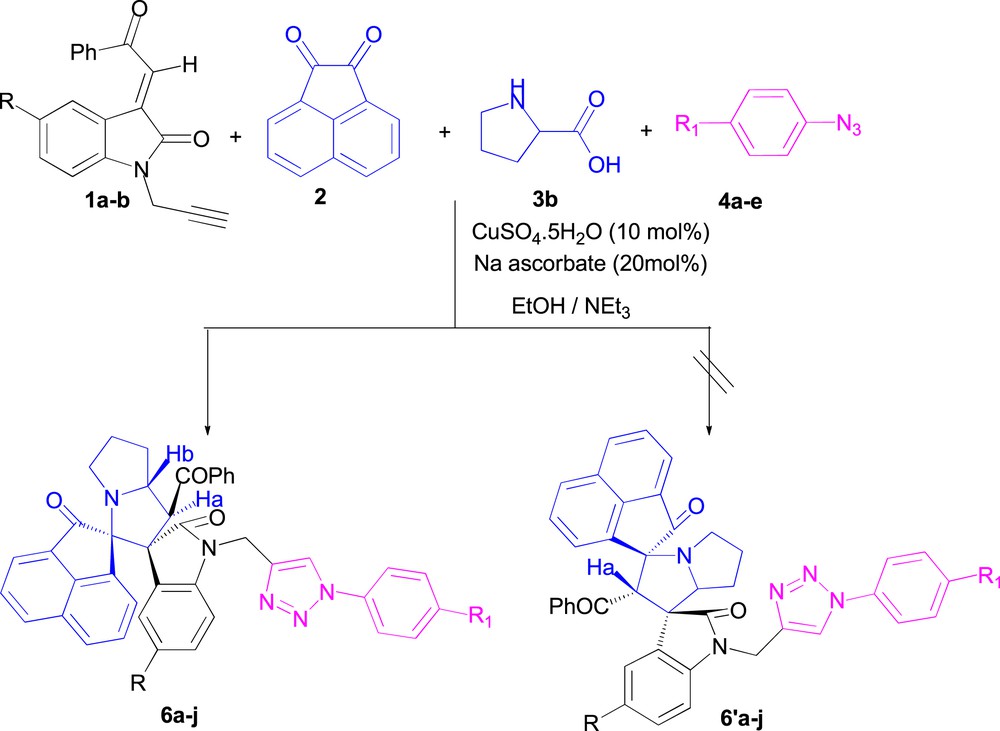

Also, it is well-known that the conventional route to triazole relies on [3+2] cycloaddition between alkynes and organic azides [20]. We describe in this article an efficient synthesis of a series of novel spirooxindolopyrrolidine- and spirooxindolopyrrolizidine-linked 1,2,3-triazole conjugates via a one-pot, four-component condensation of (E)-2-(1-propargyl-2-oxoindoline-3-ylidene)acetophenones 1a–b, acenaphthenequinone 2, sarcosine 3a or proline 3b, and substituted aryl azides 4a–e using Cu(I) as the catalyst (Scheme 1).

Synthesis of spirooxindole–pyrrolidine/pyrrolizidine-linked 1,2,3-triazole conjugates.

Exocyclic enones and terminal triple bonds have been occasionally served as dipolarophiles for the synthesis of spiropyrrolidine, spiropyrrolizidine, and triazole derivatives. However, a survey of the literature reveals that there is no example describing the synthesis of spirooxindoles incorporating triazole and pyrrolidine or pyrrolizidine units at the same time by the one-pot, four-component synthesis. We therefore prompted to investigate the chemical activity of exocyclic enones and terminal triple bonds for [3+2] cycloaddition reactions that were not reported to date. Thus, it appeared to be highly desirable to explore this kind of a reaction that could constitute a promising strategy for the synthesis of diverse spirooxindole–pyrrolidine/pyrrolizidine-linked 1,2,3-triazole conjugates. In continuation of our interest in the synthesis of novel heterocycles employing MCRs [21–24], we therefore explored a new protocol for the synthesis of highly diversified novel functionalized spirooxindolopyrrolidine- and spirooxindolopyrrolizidine-linked 1,2,3-triazole conjugates via the one-pot, four-component condensation of (E)-2-(1-propargyl-2-oxoindoline-3-ylidene)acetophenones, acenaphthenequinone, proline or sarcosine, and substituted aryl azides.

2 Results and discussion

The N-propargylated dipolarophiles 1 possess two dipolar functional groups (C]C and CˆC), making them versatile synthons for the synthesis of triazoles and pyrrolidines/pyrrolizidines. The condensation involves two sequential [3+2] cycloaddition reactions, namely, azomethine ylide–alkene and azide–alkyne coupling. First of all, we studied these reactions step by step. The first step is the cycloaddition of aryl azides 4a–e with the propargylic function of (E)-2-(1-propargyl-2-oxoindoline-3-ylidene) acetophenone 1a using CuSO4.5H2O/Na ascorbate as the catalyst. Then, the second step is the cycloaddition of azomethine generated in situ from acenaphthenequinone 2 and sarcosine 3a across the C]C bond giving the desired cycloadducts 5a–e (Scheme 2). The two cycloaddition reactions are accomplished after 6–7h, providing yields up to 70%.

Two-step synthesis of spirooxindol e–pyrrolidine-linked 1,2,3-triazoles conjugates 5a–e.

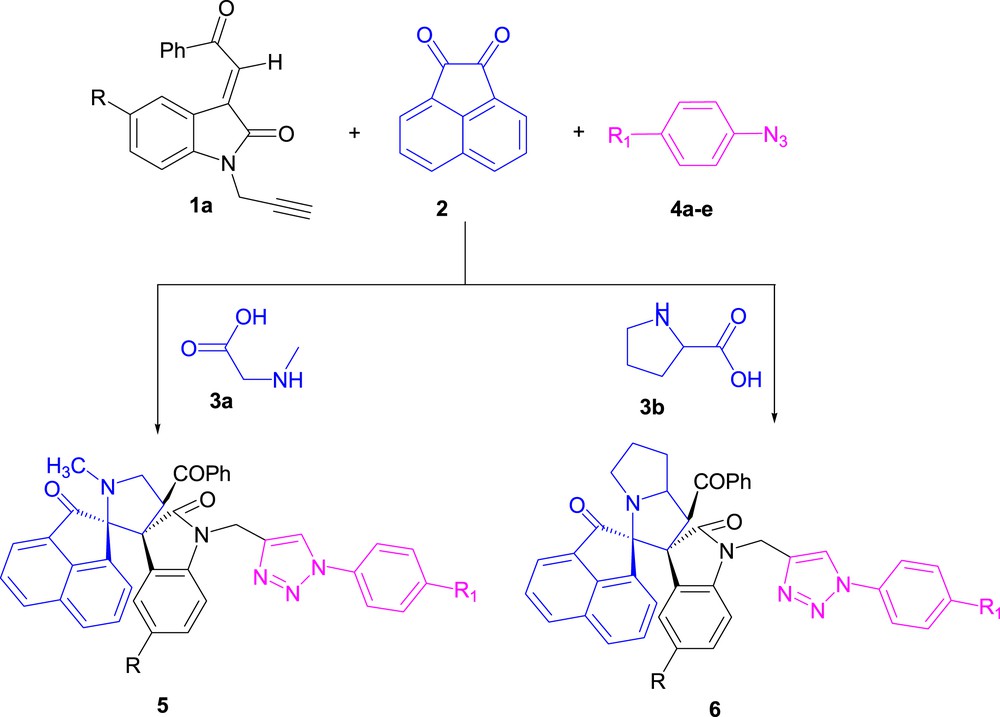

In order to achieve a high-yield reaction with a minimum number of synthetic steps and shortened reaction time, we decided to explore a new protocol, namely, condensation of azomethine ylide–alkene and azide–alkyne in the one-pot synthesis to assemble the desired product. This condensation was achieved after 3–4h, providing excellent yields of 98%. The four-component condensation of (E)-2-(1-propargyl-2-oxoindoline-3-ylidene) acetophenones (1.0 mmol) 1a, acenaphthenequinone (1.0 mmol) 2, sarcosine 3a or l-proline 3b (1.0 mmol), and substituted aryl azides (1.0 mmol) 4a–e was examined under conventional conditions (without the catalyst). Different reaction conditions (solvent, temperature, and amount of catalyst) were screened to find suitable conditions. We conducted, first, the cycloaddition reaction in various solvents, such as CH2Cl2, PhCH3, CH3CN, CH3OH, EtOH, and H2O, both at room temperature and under reflux (Scheme 3).

One-pot, four-component condensation to find suitable reaction conditions.

Without the catalyst, the cycloadducts were only obtained using refluxing ethanol, albeit in moderate amounts.

When water was used as a solvent, no product formation was detected. This may be due to the poor solubility of the dipolarophile in water. In the next step, the reaction was carried out using different coinage metal-based catalysts (Table 1). Table 1 reveals that the silver-catalyzed reaction allowed obtaining the corresponding dispirooxindolopyrrolidine-linked triazoles 5a–e and dispirooxindolopyrrolidine-linked triazoles 6a–e within a considerably shorter reaction time (12h) in improved isolated yields (65%–82%) as yellowish solids. The reaction time could be further shortened to only 3–4 h using 10 mol % of CuSO4.5H2O and 20 mol % of the Na ascorbate catalyst. Moreover, all [3+2] cycloadditions involving dipolarophile 1 and azomethine-ylide/azide furnished the targeted cycloadducts in even superior yields (85%–96%) compared with the Ag2CO3- and CuI-catalyzed syntheses. Our synthetic approach was based on a four-component strategy involving the 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition between (E)-2-(1-propargyl-2-oxoindoline-3-ylidene)acetophenones (1) and azomethine ylides generated in situ from acenaphthenequinone (2), sarcosine (3a), and substituted azides (4a–e) (Scheme 4).

Optimization of 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition reaction conditions.

| Entry | Compoundsa | Conventional conditions | Ag2CO3-catalyzedb | CuI-catalyzed conditionb | CuSO4.5H2O/Na ascorbate catalyzed | ||||

| Time | Yield (%) | Time | Yield (%)b | Time | Yield (%)b | Time | Yield (%)b | ||

| 1 | 5a | 72 | 47 | 12 | 80 | 6 | 85 | 4 | 95 |

| 2 | 5b | 48 | 59 | 12 | 79 | 6 | 83 | 4 | 93 |

| 3 | 5c | 120 | 20 | 12 | 70 | 8 | 68 | 4 | 85 |

| 4 | 5d | 72 | 50 | 12 | 65 | 6 | 74 | 4 | 87 |

| 5 | 5e | 72 | 57 | 12 | 78 | 6 | 80 | 4 | 96 |

| 6 | 6a | 48 | 65 | 12 | 82 | 6 | 79 | 3 | 90 |

| 7 | 6b | 72 | 48 | 12 | 69 | 6 | 72 | 3 | 96 |

| 8 | 6c | 120 | 25 | 12 | 75 | 8 | 65 | 3 | 87 |

| 9 | 6d | 48 | 48 | 12 | 68 | 8 | 73 | 3 | 85 |

| 10 | 6e | 48 | 52 | 12 | 74 | 6 | 82 | 3 | 96 |

a All reactions were carried out in refluxing ethanol.

b The reaction was carried out using 10 mol % of the catalyst and 20 mol % of Na ascorbate in the presence of Et3N.

Synthesis of spirooxindole–pyrrolidine-linked 1,2,3-triazole conjugates 5a–j using the one-pot four-component approach.

Having established suitable reaction conditions, dipolarophiles 1 featuring two dipolar functional groups readily reacted with acenaphthenequinone 2, sarcosine 3a, and substituted p-aryl azides 4a–e in the presence of CuSO4.5H2O (10 mol %)/Na ascorbate (20 mol %) as the catalyst in refluxing ethanol to obtain the desired cycloadducts 5a–j as a single product in good yield (Scheme 4, Table 2), independently of the nature of aryl substituents R and R1 of the starting material 1 and ArN3. No nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopic evidence for completing the formation of other isomeric compounds 5′ was obtained.

Synthesis of dispiropyrrolidine triazole derivatives 5a–ja.

| Entry | R1 | R | Time | Product | Yield (%) |

| 1 | H | H | 4 | 5a | 95 |

| 2 | OCH3 | H | 4 | 5b | 93 |

| 3 | CH3 | H | 4 | 5c | 85 |

| 4 | Cl | H | 4 | 5d | 87 |

| 5 | NO2 | H | 4 | 5e | 96 |

| 6 | H | Br | 4 | 5f | 92 |

| 7 | OCH3 | Br | 3 | 5g | 86 |

| 8 | CH3 | Br | 4 | 5h | 88 |

| 9 | Cl | Br | 3 | 5i | 91 |

| 10 | NO2 | Br | 3 | 5j | 89 |

a All reactions were carried out in ethanol at 78 °C in the presence of CuSO4.5H2O (10 mol %)/Na ascorbate(20 mol %) and Et3N.

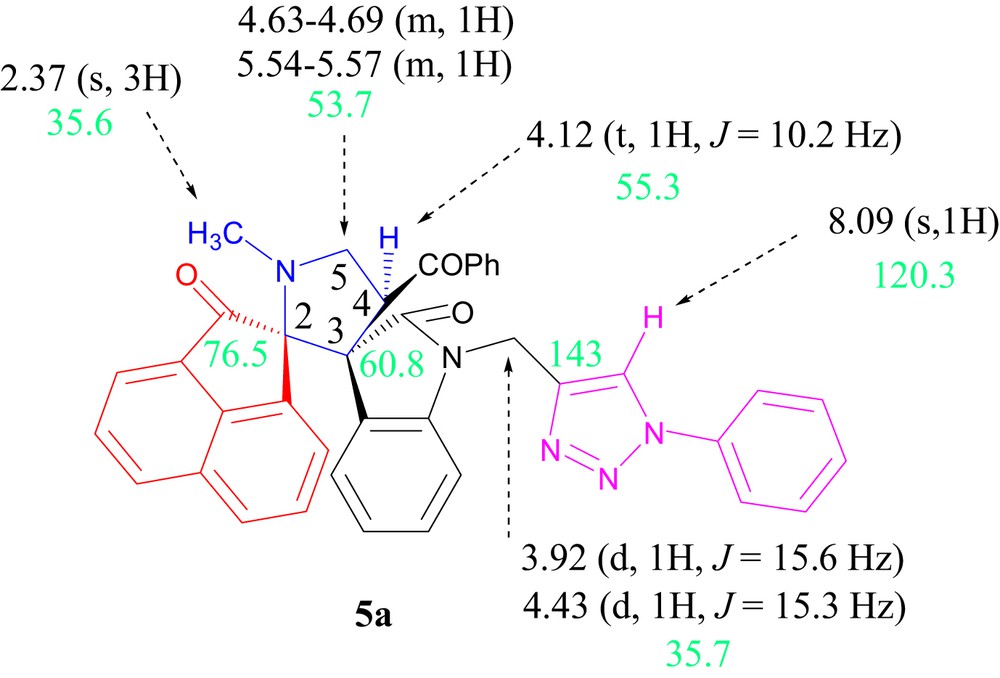

The structural and stereochemical features of all spiroadducts 5 are supported by the infrared (IR) and NMR spectroscopic data, as exemplified for cycloadduct 5a.

The 1H and 13C spectroscopic data of 5a are illustrated in Fig. 2.

Selected 1H and 13C NMR chemical shifts of 5a.

The IR spectrum of 5a shows absorptions at 1621, 1728, and 1667 cm−1 due to oxindole ring carbonyls, dihydrophenalenone carbonyl, and benzoyl carbonyl. The proton NMR (1H NMR) spectrum of compound 5a shows a singlet at δ 2.38 ppm due to the N-methyl protons. Additionally, two doublets at δ 3.86 ppm (J = 15.6 Hz) and at δ 4.45 ppm (J = 15.3 Hz) correspond to the NeCH2 group. The multiplets at δ 4.63–4.69 and δ 5.54–5.57 ppm and a triplet at 4.12 ppm (J = 10.2 Hz) are assigned to the two geminal eCH2 protons of the spiropyrrolidine ring and the pyrrolidinyl proton, respectively. The occurrence of these signals clearly proves the regiochemistry of the azomethine ylide–alkene cycloaddition reaction. The multiplicity of the pyrrolidinyl proton as a triplet is due to the coupling with the two geminal eCH2 protons of the spiropyrrolidine. If the other regioisomer 5'a (Scheme 5) would have been formed, the pyrrolizidinyl proton H-4 should give rise to a singlet pattern in the 1H NMR spectrum, and this is not observed.

Regioselective synthesis of compounds 5a–i.

Further, the off-resonance-decoupled carbon NMR (13C NMR) of the product displays signals at δ 60.8 and 76.5 ppm that corresponds to the two spirocarbons of the pyrrolidine cycle. The signals at δ 175.8 ppm and δ 205.1 ppm confirm the presence of dipolarophile carbonyl group. As well as, the resonance at δ 197.3 ppm is due to the dihydrophenalenone carbonyl groups. In the distortionless enhancement by polarization transfer (DEPT)-135 spectrum, the signal at δ 35.6 ppm is due to NeCH3; further peaks at δ 53.7 and 55.3 are attributed to the carbon of the pyrrolidine ring.

The disappearance of the vinylic C]CeH peak at δ 7.82 present in the starting material also confirms the disappearance of the exocyclic double bond. Also, the replacement of the triplet at δ 2.49 ppm due to the acetylenic CeH in (E)-2-(1-propargyl-2-oxoindoline-3-ylidene)acetophenones 1 by a low-field singlet at δ 8.09 ppm confirms the formation of a 1,2,3-triazole ring. On the other hand, the regiochemistry of the copper-catalyzed [3+2] cycloaddition reaction is supported by the 13C NMR data.

The chemical shifts of the two triazole carbons at δ = 120.3 ppm and δ = 143 ppm are the characteristics for 1,4-disubstituted-1H-1,2,3-triazoles [25–28]. The quaternary carbon of a hypothetical isomeric triazole compound should appear at around 133 ppm [28]. The formation of these regioisomeric 1,5-disubstituted-1H-1,2,3-triazoles has been reported to occur by Ru-catalyzed cycloaddition [29,30], but we are not aware of the copper-catalyzed reactions leading to these isomers. To conclude, the reaction was found to be highly regioselective leading to the formation of only one detectable regioisomer, and the combined spectroscopic data rule out the alternative structure 5'a (Scheme 5).

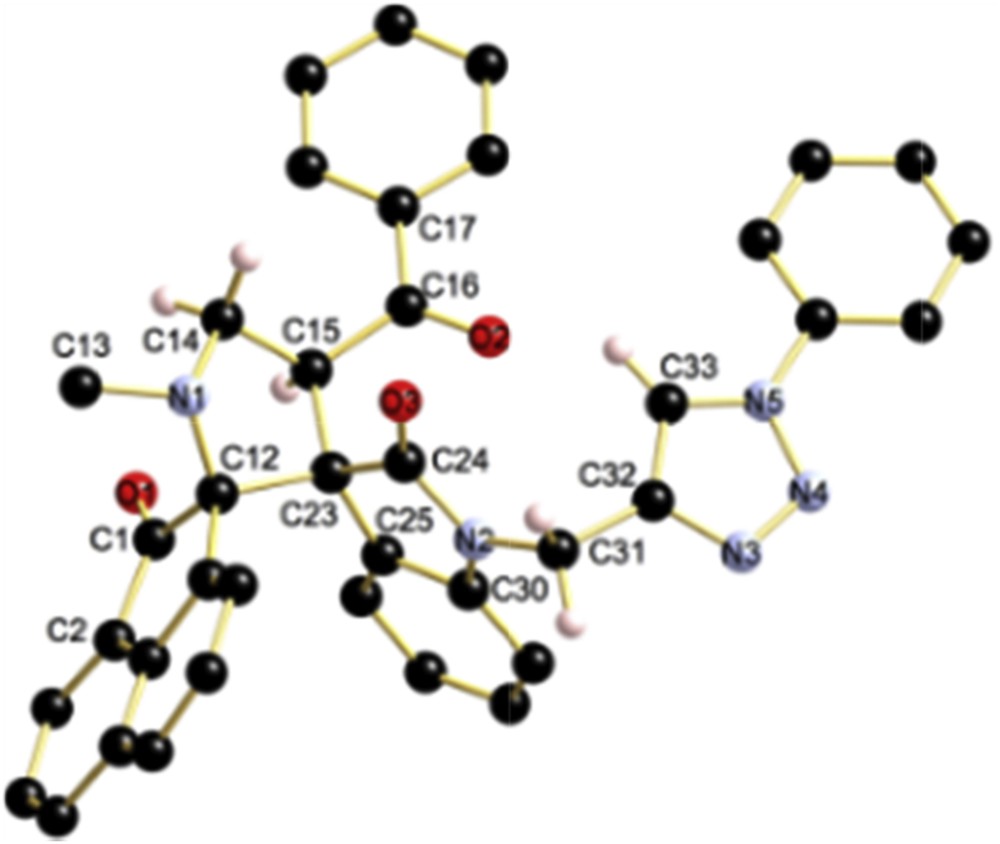

The regio- and stereochemical outcome of the cycloaddition was unambiguously ascertained by a single-crystal X-ray diffraction study of cycloadduct 5a, whose molecular structure is presented in Fig. 3. The structure reveals that the cycloadduct was formed through an exo-approach between (E)-2-(1-propargyl-2-oxoindoline-3-ylidene)acetophenones 1 and a W-shaped ylide. The latter is more stable than the S-shaped form [31], which is in accordance with many similar cycloaddition studies [32].

View of the molecular structure of compound 5a. Selected bond lengths (Å) and angles (°): C12–N1 1.4571(16), C14–N1 1.4656(16), C1–O1 1.2133(16), C16–O2 1.2162(16), C44–O3 1.2139(15), N2–C30 1.4027(16), C31–C32 1.3613(17), C33–N5 1.3439(17), N5–N4 1.3434(16), N4–N3 1.3109(17), N3–C32 1.3541(18); N1–C14–C15 105.12(10), C14–C15–C23 105.22(10), C15–C23–C12 100.41(10), C23–C12–N1 101.22(102), C12–N1–C14 108.48(10), C15–C23–C24 113.57(10), C15–C23–C25 116.29(10), C23–C24–N2 107.50(10), C24–N2–C30 111.36(10), N2–C30–C25 109.50(11).

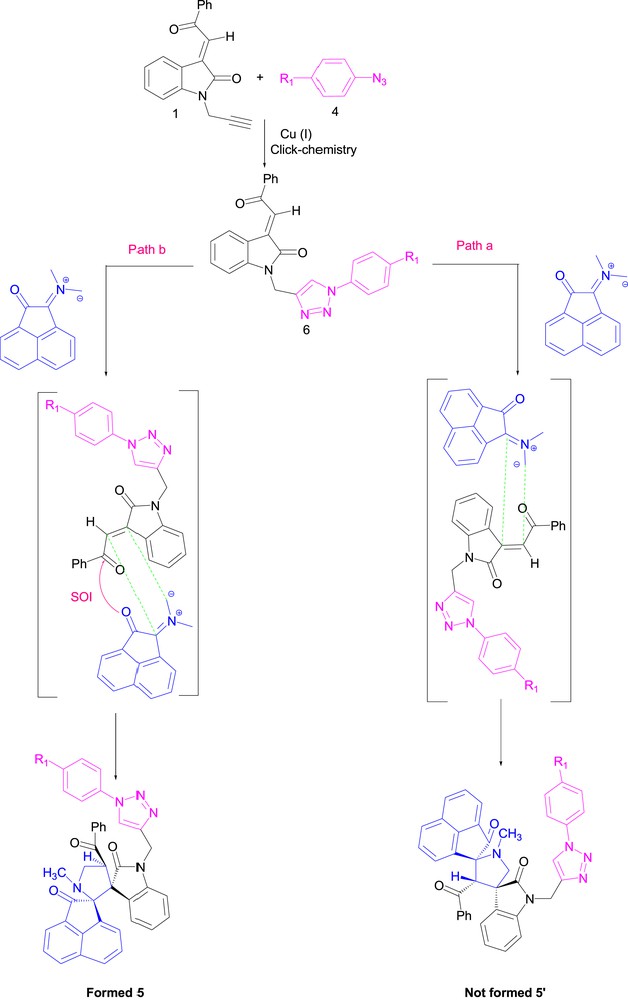

A plausible reaction mechanism for the formation of triazole-containing spirooxindolopyrrolidine heterocycles 5 is depicted in Scheme 6.

Plausible mechanism for the regio- and stereoselective dispiropyrrolidine triazole formation.

The proposed pathways consist of two parts: the first part indicates the formation of triazole intermediate 6 by Cu (I) catalyzed 1,3-azide alkyne cycloaddition. The Cu (I) species is generated in situ by sodium ascorbate reducing Cu(II) to Cu(I) [33]. In the second part, intermediate 6 undergoes subsequent 1,3-cycloaddition reaction with the generation of azomethine ylide via the decarboxylative condensation of acenaphthenequinone and sarcosine to give the desired product 5 (path B). However, in the case of path B, the presence of secondary orbital interactions [34–36] in the transition state stabilize the intermediate led to the formation of 5, but, in case of path A, no such stabilization by secondary orbital interactions occurs as shown in Scheme 6. The formation of regioisomer 5 via path B is more favorable which is not possible in path A [37,38]. The role of Cu(I) [33] in catalyzing only the azide–alkyne click addition in the first part of the pathway was also confirmed by an independent reaction of our dipolarophile with acenaphthenequinone and sarcosine or proline. The reaction was attempted in both the presence and absence of CuSO4.5H2O (10 mol %)/sodium ascorbate (20 mol %).

The reactions resulted in the formation of 5 in good yield, suggesting that Cu (I) is catalyzing only the [3+2] azide–alkyne cycloaddition and has no effect on [3+2] cycloaddition reaction between azomethine ylide and alkene.

Encouraged by the successful formation of the targeted cycloadducts 5a–j, we have extended this reaction using cyclic amino acids like l-proline. A series of the expected dispirooxindolopyrrolizidine–triazoles 6a–j was obtained as a single regioisiomer with satisfying yields in the form of solids, employing identical reaction conditions (Scheme 7, Table 3).

Synthesis of spirooxindole–pyrrolizidine-linked 1,2,3-triazoles conjugates 6a–j using the one-pot four-component approach.

Synthesis of dispiropyrrolizidine-triazole derivatives 6a–ja.

| Entry | R1 | R | Time | Product | Yield (%) |

| 1 | H | H | 3 | 6a | 90 |

| 2 | OCH3 | H | 3 | 6b | 96 |

| 3 | CH3 | H | 3 | 6c | 87 |

| 4 | Cl | H | 3 | 6d | 85 |

| 5 | NO2 | H | 3 | 6e | 96 |

| 6 | H | Br | 3 | 6f | 92 |

| 7 | OCH3 | Br | 2 | 6g | 88 |

| 8 | CH3 | Br | 3 | 6h | 80 |

| 9 | Cl | Br | 2 | 6i | 83 |

| 10 | NO2 | Br | 2 | 6j | 81 |

a All reactions were carried out in ethanol at 78 °C in the presence of CuSO4.5H2O (10 mol %)/Na ascorbate(20 mol %) and Et3N.

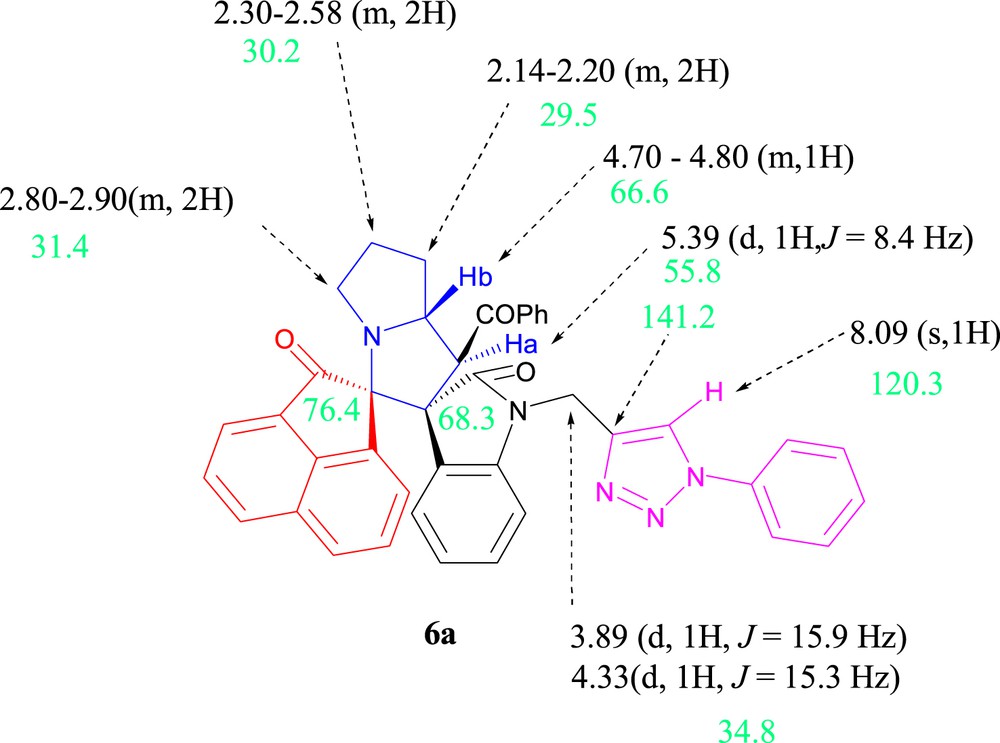

The structures of dispirooxindoles-triazole derivatives 6a–j were confirmed through spectroscopic analysis, as exemplified by 6a.

The IR spectrum exhibits peaks at 1606, 1713, and 1728 cm−1 due to the oxindole ring carbonyls, the dihydrophenalenone carbonyl, and the benzoyl carbonyl.

Selected chemical shifts of dispirooxindoles-triazole 6a are depicted in Fig. 4.

Selected 1H and 13C NMR chemical shifts of 6a.

The 1H NMR spectra for the resulting cycloadduct 6a displayed a characteristic doublet for the proton Ha at δ 5.40 (J = 8.4 Hz) due to coupling with Hb, proving the regiochemistry of cycloaddition reaction and a multiplet for the proton Hb [24]. This excludes the presence of the hypothetical inverse regioisomer 6'a (Scheme 8), for which the 1H NMR spectrum should exhibit a doublet in compound 6a coupling with the proton Hb in the trans-position with the latter.

Regioselective synthesis of compounds 6a–i.

This is confirmed by the magnitude of its coupling constant (2J = 8.4 Hz).

In addition, the 13C NMR spectrum of 6a displays two peaks at δ 68.3 and 76.4 ppm corresponding to the two spirocarbons. In the DEPT-135 spectrum, the peaks at δ 29.5, 30.2, and 31.4 ppm indicate the presence of three methylene groups. The two resonances at δ 55.8 and 66.6 ppm are attributed to pyrrolizidinyl carbons.

Also, the replacement of the triplet at δ 2.49 ppm due to the acetylenic CeH in (E)-2-(1-propargyl-2-oxoindoline-3-ylidene)acetophenones 1 by a low-field singlet at δ 8.09 ppm confirms the formation of a 1,2,3-triazole ring. The chemical shifts of the two triazole carbons at δ = 120.3 and 141.2 ppm are the characteristics for 1,4-disubstituted-1H-1,2,3-triazoles, in accordance with the literature [25–28].

Therefore, the data of these results confirm the existence of regioisomer 6a and rule out the formation of the other regioisomer 6'a (Scheme 8).

3 Biological activities

3.1 Antibacterial and antifungal activity – Structural activity relationship (SAR)

The antibacterial activity of the synthesized compounds was screened against four bacteria, namely, Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 96 (S A), Escherichia coli ATCC 443 (E C), Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 1688 (P A), and gram-positive Staphylococcus pyogenus ATCC 442 (S.P). Ampicillin and gentamycin were used as standard antibacterial agents. The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) was defined as the lowest concentration of the product inhibiting the visible growth of each microorganism. The MICs of the synthesized compounds were determined by the broth microdilution method, as described by Rattan [39]. The antifungal activity of the products was also tested against two pathogenic reference yeasts, namely, Candida albicans ATCC 227(CA) and Aspergillus niger ATCC 282(A.N). Griseofulvin and nystatin were used as standard antifungal agents [40]. The MIC was defined as the lowest drug concentration that prevents visible microorganism growth after incubation at 37 °C between 18 and 24h. All product stock solutions were prepared by dissolution in 10% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). The in vitro antibacterial and antifungal screening results are summarized in Table 4. Since it is literature-known that the presence of copper surfaces, copper-containing nanoparticles, and Cu ions in solution may affect the biological activity in screening tests [41–43], we checked whether our samples have been contaminated by Cu traces stemming from the CuSO4 catalyst that was employed for the cycloaddition reactions. We therefore analyzed the Cu content of compound 5d and 6d by energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy. Whereas in one sample the effective Cu percentage was below the detection limit in the lower ppm range, the second sample revealed some traces of Cu, but just at the detection limit of this very sensitive technique. According to the literature, much higher concentrations may cause marked effects. For example, Candida utilis is completely inhibited at 0.04 g/L copper concentrations, Tubercle bacillus is inhibited by copper as simple cations or complex anions in concentrations from 0.02 to 0.2 g/L [44–46]. Therefore, we rule out that such tiny traces of Cu in our samples may influence significantly the antibacterial activity of our compounds.

Antibacterial and antifungal activities (MIC was determined in μg mL_1).

| Comp. | Antibacterial activity | Antifungal activity | ||||

| Gram-negative bacteria | Gram-positive bacteria | |||||

| E.C | P.A | S.A | S.P | C.A | A.N | |

| ATCC 443 | ATCC 1688 | ATCC 96 | ATCC 442 | ATCC 227 | ATCC 282 | |

| 5a | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT |

| 5b | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT |

| 5c | 500 | 250 | 250 | 250 | 200 | 500 |

| 5d | 250 | 250 | 250 | 500 | 250 | 250 |

| 5e | 250 | 250 | 500 | 250 | 1000 | 250 |

| 5f | 100 | 250 | 250 | 250 | 250 | 500 |

| 5g | 125 | 125 | 62.5 | 62.5 | 250 | 500 |

| 5h | 31.25 | 250 | 31.25 | 250 | 500 | 500 |

| 5i | 31.25 | 250 | 31.25 | 250 | 250 | 250 |

| 5j | 31.25 | 125 | 31.25 | 500 | 200 | 1000 |

| 6c | 500 | 100 | 500 | 500 | 200 | 500 |

| 6d | 250 | 250 | 250 | 250 | 250 | 500 |

| 6e | 125 | 500 | 250 | 250 | 250 | 1000 |

| 6f | 100 | 125 | 100 | 125 | 250 | 1000 |

| 6g | 125 | 125 | 62.5 | 62.5 | 250 | 1000 |

| 6h | 31.25 | 500 | 31.25 | 250 | 500 | 250 |

| 6i | 31.25 | 500 | 31.25 | 250 | 250 | 500 |

| 6j | 31.25 | 250 | 31.25 | 500 | 200 | 1000 |

| A | 100 | 100 | 250 | 100 | – | – |

| G | 0.5 | 1 | 0.25 | 0.5 | – | – |

| N | – | – | – | – | 100 | 100 |

| G | – | – | – | – | 500 | 100 |

The results of the antimicrobial evaluation revealed that the activity was considerably affected by introducing a methyl or methoxy group on the triazole aryl ring, as well as indolinone core substitution.

For the antibacterial activity, it was remarked that the introduction of electron-withdrawing groups on the indolinone and triazole cycle caused a considerable increase in the antibacterial potency of the tested compounds. It was observed from the screening data that the compounds 5h, 5i, 5j, 6h, 6i, and 6j with bromo substitution on the indolinone ring containing nitro, chloro, and methyl groups on the aryl ring of the triazole unit showed excellent activity against E. coli and S. aureus with an MIC value of 31.25 μg/mL.

On the other hand, in the case of S. aureus, compounds 5c, 5d, 5f, 6d, and 6e were as equipotent as ampicillin. The compounds were also evaluated against S. aureus and S. pyogenus. In this case, compounds 5g and 6g containing a methoxy group on the triazole ring and a bromo substituent on the indolinone ring showed significant potency with MIC values of 62.5 μg/mL. In the case of E. coli, compounds 5f and 6f were equally active. The remaining compounds were found to be moderate or less active compared to the standard antibiotics.

Concerning the antifungal activity and according to the MIC values, compounds bearing a nitro group at the triazole ring such as 5j and 6j as well as 5c and 6c containing a methyl group at the triazole unit were highly active against C. albicans with respect to the standard antifungal agent griseofulvin. Compounds 5h and 6h were found to be equally active against C. albicans compared to griseofulvin. The activity of the other derivatives was found to be moderate or less important. With respect to the structure–activity relationship (SAR), the data show that the presence of halogen substituents on indolinone and some substituents on the aryl ring of the triazole cycle enhance the activity of compounds against several bacterial and fungal tested strains.

4 Conclusion

Exploring novel pharmacological agents with a minimum number of synthetic steps and less time is a major challenge for chemists. We have synthesized a series of novel dispiropyrrolidine and dispiropyrrolizidine-fused triazole conjugates via the facile one-pot four-component cycloaddition reaction. This methodology has the advantages of providing good yields of products, environmentally friendly operational procedure, easy workup procedure, availability of reactants and starting materials, short reaction times, and high regio- and stereoselectivity. Screening of selected derivatives against four bacteria and two fungi revealed that some compounds were active antibacterial and antifungal agents.

5 Experimental section

5.1 Instruments and methods

NMR spectra were recorded with a Bruker-Spectrospin AC 300 spectrometer, operating at 300 MHz for 1H and 75 MHz for 13C with tetramethylsilane as an internal standard. CDCl3 was used as the solvent. Splitting patterns are designated as follows: s, singlet; d, doublet; and m, multiplet. Chemical shift (δ) values are given in parts per million and coupling constants (J) in Hertz. IR spectra were recorded on a JASCO FT-IR instrument (KBr pellet, in case of solids). Melting points were determined by using an Electrothermal 9100 digital melting point apparatus. Materials: thin-layer chromatography (TLC) plates (Merck, Silica gel 60 F254 0.2 mm 200 × 200 mm) substances were detected using UV light at 254 nm.

5.2 X-ray structure study

A colorless single crystal of 5a has been mounted on an Xcalibur, Sapphire3 diffractometer, and the intensity data have collected at 173 K using MoKα radiation (λ = 0.71073 Å). Using Olex2,59 the structure was solved with the Superflip60 structure solution program using Charge Flipping and refined with the ShelXL61 refinement package using least-squares minimization. Crystal and refinement data for 5a: C39H29N5O3; M = 481.55; crystal system: triclinic; space group P-1, a = 9.8526(5) Å, b = 12.0736(6) Å, c = 12.7965(6) Å, α = 88.076(4), β = 99.486(4), γ = 87.771(4)°, V = 1494.9(3) Å3, Z = 2, F(000) = 504, μ(Mo-Kα) = 0.089 mm-1, Dcalc = 1.368 g/cm3. 22,063 reflections collected, 6650 unique and 5322 with I>2σ(I). Final agreement factors: R1 = 0.05429 (all observed) and 0.0419 with I>2σ(I), wR2 = 0.1034 (all observed) and 0.0542 with I>2σ(I). Goodness of Fit = 1.028. Final residuals ρmax = 0.30, ρmin = −0.25 e−/Å3. Crystallographic data.

(Excluding structural factors) for the structure of 5a have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC) with the deposition number 1564072. These data may be obtained free of charge from CCDC through www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.

5.3 General procedure for the synthesis of spiropyrrolidine 5 and spiropyrrolizidine 6 linked 1,2,3-triazoles

An equimolar mixture of (E)-2-(1-propargyl-2-oxoindoline-3 ylidene)acetophenones (1a–b) (1.0 mmol), acenaphthenequinone (2) (1.0 mmol), α-amino acids (3a) or (3b) (1.0 mmol), and substituted aryl azides (4a–e) (1.0 mmol) were dissolved in 10 mL of ethanol in a 50 mL round-bottomed flask. The reaction contents were stirred magnetically in an oil-bath maintained at 78 °C. An aqueous solution of CuSO4.5H2O (10 mol %) followed by an aqueous solution of sodium ascorbate (20 mol %) were then added to the reaction mixture and the heating was continued. After completion of the reaction as determined by TLC, the solvent was removed under reduced pressure. The residue was purified by column chromatography on silica gel using ethyl acetate cyclohexane (7:3 v/v) as the eluant to obtain the pure products 5 and 6.

5.3.1 1-N-methyl-spiro [2.3′] oxoacenaphthylen-2yl)-spiro [3.5″]-3″eN-((1-(4-phenyl))-1H-1, 2,3-triazol-4-yl) methyl) indolin-2-one-pyrrolidine (5a)

Yellow solid; M.p.: 250–252 °C; Yield 95%; 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 2.37 (s, 3H, –NCH3), 3.92 (d, 1H, N-CH2, J = 15.6 Hz), 4.12 (t, 1H, C–H, J = 10.2 Hz), 4.43 (d, 1H, N-CH2, J = 15.3 Hz), 4.63–4.69 (m, 1H, C–H), 5.54–5.57 (m, 1H, C–H), 6.44–8.09 (m, 18H, Ar-H), 8.09 (s, 1H, Ar-H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 205.1, 197.3, 175.8, 143.7, 143.1, 143.0, 137.2, 136.5, 134.1, 133.2, 131.7, 131.5, 130.2, 129.5, 128.5, 128.4, 128.3, 127.8, 125.5, 124.6, 123.8, 122.6, 121.6, 121.1, 120.3, 108.6, 76.5, 60.8, 55.3, 53.7, 35.7, 35.6; IR (KBr, cm−1): νmax = 1621,1667, 1728; CHN Anal. Calcd for C39H29N5O3: C, 76.08; H, 4.75; N, 11.37. Found: C, 76.28; H, 4.86; N, 11.48.

5.3.2 1-N-methyl-spiro[2.3′]oxoacenaphthylen-2yl)-spiro[3.5″]-3″-N-((1-(4-methoxyphenyl))-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)methyl)indolin-2-one-pyrrolidine (5b)

Yellow solid; M.p.: 242–244 °C; Yield 93%; 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 2.26 (s, 3H, –NCH3), 3.85 (d, 1H, N-CH2, J = 15.9 Hz), 3.92 (s, 3H, OCH3), 4.02 (t, 1H, C–H, J = 10.2 Hz), 4.37–4.42 (m, 1H, C–H), 4.46 (d, 1H, N-CH2, J = 15.9 Hz), 5.47–5.52 (m, 1H, C–H), 6.39–7.95 (m, 18H, Ar-H),7.85 (s, 1H, Ar-H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 204.9, 197.8, 172.5, 160.1, 142.3, 141.7, 140.9, 137.4, 132.4, 132.0, 131.8, 130.7, 130.4, 129.8, 129.4, 128.1, 127.9, 125.2, 122.5, 122.4, 120.3, 119.2, 115.2, 114.5, 109.9, 81.3, 63.1, 55.6, 52.7, 51.7, 35.0, 34.9; IR (KBr, cm−1): νmax = 1627,1669, 1732; CHN Anal. Calcd for C40H31N5O3: C, 74.40; H, 4.84; N, 10.85. Found: C, 74.63; H, 4.97; N, 10.98.

5.3.3 1-N-methyl-spiro[2.3′]oxoacenaphthylen-2yl)-spiro[3.5″]-3″-N-((1-(4-methylphenyl))-1H- 1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)methyl)indolin-2-one-pyrrolidine (5c)

Yellow solid; M.p.: 249–251 °C; Yield 85%; 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ H: 2.27 (s, 3H, –NCH3), 2.51 (s, 3H, CH3), 3.88 (d, 1H, NCH2, J = 15.9 Hz), 4.03 (t, 1H, C–H, J = 10.2 Hz), 4.39–4.44 (m, 1H, C–H), 4.47 (d, 1H, NCH2, J = 15.6 Hz), 5.48–5.54 (m, 1H, C–H), 6.41–7.96 (m, 14H, Ar-H), 7.89 (s, 1H, Ar-H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 204.8, 197.8, 172.4, 142.4, 141.7, 140.8, 139.7, 137.2, 136.5, 132.6, 131.9, 131.7, 131.0, 130.3, 129.7, 129.3, 129.1, 128.1, 128.0, 127.9, 125.4, 122.7, 121.5, 120.5, 119.2, 118.0, 115.4, 110.0, 76.5, 63.0, 52.7, 51.7, 35.3, 34.8, 21.4; IR (KBr, cm−1): νmax = 1629,1670, 1735; CHN Anal. Calcd for C40H31N5O3: C, 76.29; H, 4.96; N, 11.12. Found: C, 76.49; H, 5.07; N, 11.26.

5.3.4 1-N-methyl-spiro[2.3′]oxoacenaphthylen-2yl)-spiro[3.5″]-3″-N-((1-(4-chlorophenyl))-1H- 1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)methyl)indolin-2-one-pyrrolidine (5d)

Yellow solid; M.p.: 253–255 °C; Yield 87%; 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 2.23 (s, 3H, –NCH3), 3.93 (d, 1H, N-CH2, J = 15.6 Hz), 4.03 (t, 1H, C–H, J = 9.9 Hz), 4.30–4.35 (m, 1H, C–H), 4.45 (d, 1H, N-CH2, J = 15.9 Hz), 5.48–5.54 (m, 1H, C–H), 6.41–7.95 (m, 18H, Ar-H), 7.95 (s, 1H, Ar-H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 205.4, 198.1, 172.7, 142.9, 141.8, 140.8, 137.3, 135.0, 134.8, 133.7, 132.6, 131.9, 131.8, 130.8, 130.3, 129.8, 129.7, 129.5, 128.3, 128.0, 127.9, 125.2, 122.5, 121.9, 120.4, 119.1, 115.3, 109.9, 76.6, 62.9, 52.7, 51.9, 35.1, 34.8; IR (KBr, cm−1): νmax = 1629,1672, 1735; CHN Anal. Calcd for C39H28ClN5O3: C, 72.05; H, 4.34; N, 10.77. Found: C, 72.28; H, 4.45; N, 10.90.

5.3.5 1-N-methyl-spiro[2.3′]oxoacenaphthylen-2yl)-spiro[3.5″]-3″-N-((1-(4-nitrophenyl))-1H- 1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)methyl)indolin-2-one-pyrrolidine (5e)

Yellow solid; M.p.: 256–258 °C; Yield 96%; 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 2.22 (s, 1H, –NCH3), 4.02–4.12 (m, 2H, NCH2), 4.21–4.26 (m, 1H, C–H), 4.40–4.52 (m, 1H, C–H), 5.51–5.57 (m, 1H, C–H), 6.42–8.42 (m, 19H, Ar-H), 7.80 (s,1H, Ar-H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 205.1, 197.8, 172.3, 146.8, 141.4, 140.3, 136.8, 132.5, 132.2, 131.4, 131.2, 130.2, 129.6, 129.5, 129.3, 127.8, 127.6, 127.4, 124.8, 124.6, 122.0, 120.1, 119.9, 114.9, 109.3, 80.3, 62.2, 52.4, 51.7, 34.4, 34.3; IR (KBr, cm−1): νmax = 1631,1676, 1738; CHN Anal. Calcd for C39H28N6O5: C, 70.90; H, 4.27; N, 12.72. Found: C, 71.13; H, 4.38; N, 12.85.

5.3.6 1-N-methyl-spiro[2.3′]oxoacenaphthylen-2yl)-spiro[3.5″]-5-bromo((1-(4-phenyl))-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)methyl)indolin-2-one- pyrrolidine (5f)

Yellow solid; M.p.: 245–247 °C; Yield 92%; 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 2.38 (s, 3H, –NCH3), 3.89 (d, 1H, N-CH2, J = 15.6 Hz), 4.05 (t, 1H, C–H, J = 10.2 Hz), 4.43 (d, 1H, N-CH2, J = 15.3 Hz), 4.63–4.69 (m, 1H, C–H), 5.52–5.56 (m, 1H, C–H), 6.45–8.15 (m, 19H, Ar-H), 8.15 (s, 1H, Ar H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 205.1, 197.3, 175.8, 143.7, 143.1, 143.0, 137.2, 136.5, 134.1, 133.2, 131.7, 131.5, 130.2, 129.5, 128.5, 128.4, 128.3, 127.8, 125.5, 124.6, 123.8, 122.6, 121.6, 121.1, 120.3, 76.5, 60.8, 55.3, 53.7, 35.7, 35.6; IR (KBr, cm−1): νmax = 1624,1668, 1732; CHN Anal. Calcd for C39H28BrN5O3: C, 67.44; H, 4.06; N, 10.08. Found: C, 67.64; H, 4.19; N, 10.22.

5.3.7 1-N-methyl-spiro[2.3′]oxoacenaphthylen-2yl)-spiro[3.5″]-5-bromo((1-(4-methoxyphenyl))- 1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)methyl)indolin-2-one- pyrrolidine (5g)

Yellow solid; M.p.: 232–234 °C; Yield 86%; 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 2.26 (s, 3H, –NCH3), 3.85 (d, 1H, N-CH2, J = 15.9 Hz), 3.92 (s, 3H, OCH3), 4.02 (t, 1H, C–H, J = 10.2 Hz), 4.37–4.42 (m, 1H, C–H), 4.46 (d, 1H, N-CH2, J = 15.9 Hz), 5.47–5.52 (m, 1H, C–H), 6.39–7.95 (m, 17H, Ar-H), 7.85 (s, 1H, Ar-H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 204.9, 197.8, 172.5, 160.1, 142.3, 141.7, 140.9, 137.4, 132.4, 132.0, 131.8, 130.7, 130.4, 129.8, 129.4, 128.1, 127.9, 125.2, 122.5, 122.4, 120.3, 119.2, 115.2, 114.5, 109.9, 81.3, 63.1, 55.6, 52.7, 51.7, 35.0, 34.9; IR (KBr, cm−1): νmax = 1637,1676, 1737; CHN Anal. Calcd for C40H30BrN5O4: C, 66.30; H, 4.17; N, 9.67. Found: C, 66.52; H, 4.28; N, 9.81.

5.3.8 1-N-methyl-spiro[2.3′]oxoacenaphthylen-2yl)-spiro[3.5″]-5-bromo((1-(4-methylphenyl))- 1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)methyl)indolin-2-one- pyrrolidine (5h)

Yellow solid; M.p.: 235–237 °C; Yield 88%; 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 2.27 (s, 3H, –NCH3), 2.51 (s, 3H, CH3), 3.88 (d, 1H, N-CH2, J = 15.9 Hz), 4.03 (t, 1H, C–H, J = 10.2 Hz), 4.39–4.44 (m, 1H, C–H), 4.47 (d, 1H, N-CH2, J = 15.6 Hz), 5.48–5.54 (m, 1H, C–H), 6.41–7.96 (m, 13H, Ar-H), 7.89 (s, 1H, Ar-H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 204.8, 197.8, 172.4, 142.4, 141.7, 140.8, 139.7, 137.2, 136.5, 132.6, 131.9, 131.7, 131.0, 130.3, 129.7, 129.3, 129.1, 128.1, 128.0, 127.9, 125.4, 122.7, 121.5, 120.5, 119.2, 118.0, 115.4, 110.0, 76.5, 63.0, 52.7, 51.7, 35.3, 34.8, 21.4; IR (KBr, cm−1): νmax = 1628,1676, 1739; CHN Anal. Calcd for C40H30BrN5O3: C, 67.80; H, 4.27; N, 9.88. Found: C, 68.03; H, 4.38; N, 10. 01.

5.3.9 1-N-methyl-spiro[2.3′]oxoacenaphthylen-2yl)-spiro[3.5″]-5-bromo((1-(4-chlorophenyl))- 1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)methyl)indolin-2-one- pyrrolidine (5i)

Yellow solid; M.p.: 253–255 °C; Yield 87%; 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 2.23 (s, 3H, –NCH3), 3.93 (d, 1H, N-CH2, J = 15.6 Hz), 4.03 (t, 1H, C–H, J = 9.9 Hz), 4.30–4.35 (m, 1H, C–H), 4.45 (d, 1H, N-CH2, J = 15.9 Hz), 5.48–5.54 (m, 1H, C–H), 6.41–7.95 (m, 17H, Ar-H), 7.95 (s, 1H, Ar-H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 205.4, 198.1, 172.7, 142.9, 141.8, 140.8, 137.3, 135.0, 134.8, 132.7, 132.6, 131.9, 131.8, 130.8, 130.3, 129.8, 129.7, 129.5, 128.3, 128.0, 127.9, 125.2, 122.5, 121.9, 120.4, 119.1, 115.3, 76.6, 62.9, 52.7, 51.9, 35.1, 34.8; IR (KBr, cm−1): νmax = 1629,1679, 1736; CHN Anal. Calcd for C39H27BrClN5O3: C, 64.25; H, 3.73; N, 9.61. Found: C, 64.48; H, 4.84; N, 9.75.

5.3.10 1-N-methyl-spiro[2.3′]oxoacenaphthylen-2yl)-spiro[3.5″]-5-bromo((1-(4-nitrophenyl))-1H- 1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)methyl)indolin-2-one- pyrrolidine (5j)

Yellow solid; M.p.: 247–249 °C; Yield 89%; 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 2.22 (s, 1H, –NCH3), 4.02–4.12 (m, 2H, NCH2), 4.21–4.26 (m, 1H, C–H), 4.40–4.52 (m, 1H, C–H), 5.51–5.57 (m, 1H, C–H), 6.42–8.42 (m, 18H, Ar-H), 7.80 (s,1H, Ar-H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 205.1, 197.8, 172.3, 146.8, 141.4, 140.3, 136.8, 132.5, 132.2, 131.4, 131.2, 130.2, 129.6, 129.5, 129.3, 127.8, 127.6, 127.4, 124.8, 124.6, 122.0, 120.1, 119.9, 114.9, 109.3, 80.3, 62.2, 52.4, 51.7, 34.4, 34.3; IR (KBr, cm−1): νmax = 1630,1677, 1733; CHN Anal. Calcd for C39H27BrN6O5: C, 63.34; H, 3.68; N, 11.36. Found: C, 63.57; H, 3.79; N, 11.49.

5.3.11 1-N-methyl-spiro[2.3′]oxoacenaphthylen-2yl)-spiro[3.5″]-3″-N-((1-(4-phenyl))-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)methyl)indolin-2-one-pyrrolizidine (6a)

Yellow solid; M.p.: 250–252 °C; Yield 90%; 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 2.14–2.19 (m, 2H, CH2), 2.20–2.30 (m, 1H, C–H), 2.56–2.58 (m, 2H, C H2), 2.80–2.90 (m, 1H, C–H), 3.89 (d, 1H, N-CH2, J = 15.9 Hz), 4.33 (d, 1H, NCH2, J = 15.3 Hz), 4.70–4.80 (m, 1H, C–H), 5.39 (d, 1H, C–H, J = 8.4 Hz), 6.45–7.96 (m, 16H, Ar-H), 8.06 (s, 1H, Ar-H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 198.0, 183.1, 171.6, 147.5, 143.6, 141.2, 140.7, 140.5, 137.6, 132.6, 132.4, 132.2, 131.9, 130.7, 130.6, 129.9, 129.0, 128.8, 128.2, 128.1, 128.0, 125.1, 124.8, 122.8, 120.6, 120.3, 119.2, 115.6, 109.9, 76.4, 68.3, 66.6, 55.8, 34.8, 31.4, 30.2,29.5; IR (KBr, cm−1): νmax = 1606,1713, 1728; CHN Anal. Calcd for C41H31N5O3: C, 76.74; H, 4.87; N, 10.91. Found: C, 76.78; H, 4.98; N, 11.05.

5.3.12 1-N-methyl-spiro[2.3′]oxoacenaphthylen-2yl)-spiro[3.5″]-3″-N-((1-(4-methoxyphenyl))-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)methyl)indolin-2-one-pyrrolizidine (6b)

Yellow solid; M.p.: 210–212 °C; Yield 96%; 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 2.16–2.21 (m, 2H, CH2), 2.20–2.33 (m, 1H, C–H), 2.58–2.60 (m, 2H, C H2), 2.77–2.80 (m, 1H, C–H), 3.91 (d, 1H, N-CH2, J = 15.9 Hz), 3.94 (s, 3H, OCH3), 4.35 (d, 1H, N-CH2, J = 15.9 Hz), 4.70–4.90 (m, 1H, C–H), 5.41 (d, 1H, C–H, J = 8.4 Hz), 6.48–7.98 (m, 14H, Ar-H), 8.08 (s,1H, Ar-H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 207.6, 198.2, 171.5, 160.0, 156.7, 152.8, 142.4, 140.7, 132.5, 132.2, 131.8, 130.7, 130.4, 129.8, 129.0, 128.1, 127.9, 124.7, 122.5, 122.2, 119.9, 119.2, 115.3, 114.5, 110.1, 76.5, 68.5, 66.3, 55.6, 55.4, 46.6, 34.8, 31.3, 30.4; IR (KBr, cm−1): νmax = 1607,1716, 1730; CHN Anal. Calcd for C42H33N5O4: C, 75.10; H, 4.95; N, 10.43. Found: C, 75.14; H, 5.08; N, 10.57.

5.3.13 1-N-methyl-spiro[2.3′]oxoacenaphthylen-2yl)-spiro[3.5″]-3″-N-((1-(4-methylphenyl))-1H- 1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)methyl)indolin-2-one-pyrrolizidine (6c)

Yellow solid; M.p.: 217–219 °C; Yield 87%; 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 2.17–2.21 (m, 2H, CH2), 2.26–2.34 (m, 1H, C–H), 2.50 (s, 3H, CH3), 2.53–2.71 (m, 2H, C H2), 2.78–2.83 (m, 1H, C–H), 3.90 (d, 1H, N-CH2, J = 15.6 Hz), 4.34 (d, 1H, N-CH2, J = 15.9 Hz), 4.80–4.90 (m, 1H, C–H), 5.40 (d, 1H, C–H, J = 8.4 Hz), 6.75–7.96 (m, 16H, Ar-H), 8.12 (s,1H, Ar-H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 198.5, 197.6, 171.3, 142.3, 141.0, 140.6, 139.6, 137.4, 136.6, 132.6, 132.0, 130.9, 130.5, 129.8, 129.6, 129.2, 128.1, 128.0, 127.9, 125.0, 121.5, 120.2, 119.1, 118.0, 115.5, 110.1, 76.5, 68.4, 66.7, 55.4, 34.8, 31.2,30.3, 26.9, 21.3; IR (KBr, cm−1): νmax = 1610,1718, 1733; Anal. Calcd for C42H33N5O3: C, 76.93; H, 5.07; N, 10.68. Found: C, 76.96; H, 5.18; N, 10.82.

5.3.14 1-N-methyl-spiro[2.3′]oxoacenaphthylen-2yl)-spiro[3.5″]-3″-N-((1-(4-chlorophenyl))-1H- 1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)methyl)indolin-2-one-pyrrolizidine (6d)

Yellow solid; M.p.: 234–236 °C; Yield 85%; 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 2.15–2.17 (m, 2H, CH2), 2.20–2.30 (m, 1H, C–H), 2.58–2.60 (m, 2H, C H2), 2.78–2.83 (m, 1H, C–H), 4.07 (d, 1H, N-CH2, J = 15.9 Hz), 4.29 (d, 1H, NCH2, J = 15.9 Hz), 4.70–4.90 (m, 1H, C–H), 5.46 (d, 1H, C–H, J = 8.7 Hz), 6.45–7.98 (m, 18H, Ar-H), 8.14 (s,1H, Ar-H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 208.3, 198.3, 171.6, 167.6, 141.0, 140.5, 137.4, 135.0, 134.8, 132.7, 131.9, 130.8, 130.4, 129.8, 129.6, 128.8, 128.2, 128.1, 128.0, 124.8, 122.4, 122.0, 120.1, 115.5, 110.1, 80.1, 68.4, 66.3, 55.4, 46.6, 34.7, 31.3, 30.6; IR (KBr, cm−1): νmax = 1615,1720, 1735; CHN Anal. Calcd for C41H30ClN5O3: C, 72.83; H, 4.47; N, 10.36. Found: C, 72.85; H, 4.58; N, 10.49.

5.3.15 1-N-methyl-spiro[2.3′]oxoacenaphthylen-2yl)-spiro[3.5″]-3″-N-((1-(4-nitrophenyl))-1H- 1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)methyl)indolin-2-one-pyrrolizidine (6e)

Yellow solid; M.p.: 235–237 °C; Yield 96%; 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 2.15–2.17 (m, 2H, CH2), 2.20–2.30 (m, 1H, C–H), 2.58–2.60 (m, 2H, C H2), 2.78–2.83 (m, 1H, C–H), 4.07 (d, 1H, N-CH2, J = 15.9 Hz), 4.29 (d, 1H, NCH2, J = 15.9 Hz), 4.70–4.90 (m, 1H, C–H), 5.46 (d, 1H, C–H, J = 8.7 Hz), 6.45–8.40 (m, 18H, Ar-H), 8.14 (s,1H, Ar-H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 198.5, 197.6, 171.3, 142.3, 141.0, 140.6, 139.6, 137.4, 136.6, 132.6, 132.0, 130.9, 130.5, 129.8, 129.6, 129.2, 128.1, 128.0, 127.9, 125.0, 121.5, 120.2, 119.1, 118.0, 115.5, 110.1, 76.5, 68.4, 66.7, 55.4, 34.8, 31.2,30.3, 26.9; IR (KBr, cm−1): νmax = 1619,1728, 1738; CHN Anal. Calcd for C41H30N6O5: C, 71.71; H, 4.40; N, 12.24. Found: C, 71.73; H, 4.53; N, 12.38.

5.3.16 1-N-methyl-spiro[2.3′]oxoacenaphthylen-2yl)-spiro[3.5″]-5-bromo((1-(4-phenyl))-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)methyl)indolin-2-one- pyrrolizidine (6f)

Yellow solid; M.p.: 249–251 °C; Yield 92%; 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ H: 2.14–2.19 (m, 2H, CH2), 2.20–2.30 (m, 1H, C–H), 2.56–2.58 (m, 2H, C H2), 2.72–2.74 (m, 1H, C–H), 3.89 (d, 1H, N-CH2, J = 15.9 Hz), 4.33 (d, 1H, N-CH2, J = 15.3 Hz), 4.70–4.80 (m, 1H, C–H), 5.39 (d, 1H, C–H, J = 8.4 Hz), 6.69–7.96 (m, 15H, Ar-H), 8.06 (s,1H, Ar-H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 198.5, 197.6, 171.3, 142.3, 141.0, 140.6, 139.6, 137.4, 136.6, 132.0, 130.9, 130.5, 129.8, 129.6, 129.2, 128.1, 128.0, 127.9, 125.0, 121.5, 120.2, 119.1, 118.0, 115.5, 76.5, 68.4, 66.7, 55.4, 34.8, 31.2, 30.3, 26.9; IR (KBr, cm−1): νmax = 1616,1719, 1732; CHN Anal. Calcd for C41H30BrN5O3: C, 68.34; H, 4.20; N, 9.72. Found: C, 68.36; H, 4.33; N, 9.86.

5.3.17 1-N-methyl-spiro[2.3′]oxoacenaphthylen-2yl)-spiro[3.5″]-5-bromo((1-(4-methoxyphenyl))- 1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)methyl)indolin-2-one- pyrrolizidine (6g)

Yellow solid; M.p.: 238–240 °C; Yield 88%; 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 2.16–2.21 (m, 2H, CH2), 2.20–2.33 (m, 1H, C–H), 2.58–2.60 (m, 2H, C H2), 2.77–2.80 (m, 1H, C–H), 3.91 (d, 1H, N-CH2, J = 15.9 Hz), 3.94 (s, 3H, OCH3), 4.35 (d, 1H, N-CH2, J = 15.9 Hz), 4.70–4.90 (m, 1H, C–H), 5.41 (d, 1H, C–H, J = 8.4 Hz), 6.48–7.98 (m, 13H, Ar-H), 8.08 (s,1H, Ar-H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 207.6, 198.2, 171.5, 160.0, 156.7, 152.8, 142.4, 140.7, 132.5, 132.2, 131.8, 130.7, 130.4, 129.8, 129.0, 128.1, 127.9, 124.7, 122.5, 122.2, 119.9, 119.2, 115.3, 114.5, 110.1, 76.5, 68.5, 66.3, 55.6, 55.4, 46.6, 34.8, 31.3, 30.4; IR (KBr, cm−1): νmax = 1622,1720, 1736; CHN Anal. Calcd for C42H32BrN5O4: C, 67.20; H, 4.30; N, 9.33. Found: C, 67.21; H, 4.43; N, 9.47.

5.3.18 1-N-methyl-spiro[2.3′]oxoacenaphthylen-2yl)-spiro[3.5″]-5-bromo((1-(4-methylphenyl))-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)methyl)indolin-2-one- pyrrolizidine (6h)

Yellow solid; M.p.: 250–252 °C; Yield 80%; 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 2.17–2.21 (m, 2H, CH2), 2.26–2.34 (m, 1H, C–H), 2.50 (s, 3H, CH3), 2.53–2.71 (m, 2H, CH2), 2.78–2.83 (m, 1H, C–H), 3.90 (d, 1H, N-CH2, J = 15.6 Hz), 4.34 (d, 1H, N-CH2, J = 15.9 Hz), 4.80–4.90 (m, 1H, C–H), 5.40 (d, 1H, C–H, J = 8.4 Hz), 6.75–7.96 (m, 14H, Ar-H), 8.12 (s, 1H, Ar-H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 198.5, 197.6, 171.3, 142.3, 141.0, 140.6, 139.6, 137.4, 136.6, 132.6, 132.0, 130.9, 130.5, 129.8, 129.6, 129.2, 128.1, 128.0, 127.9, 125.0, 121.5, 120.2, 119.1, 118.0, 115.5, 76.5, 68.4, 66.7, 55.4, 34.8, 31.2,30.3, 26.9, 21.3; IR (KBr, cm−1): νmax = 1629,1727, 1739; CHN Anal. Calcd for C42H32BrN5O3: C, 68.67; H, 4.39; N, 9.53. Found: C, 68.71; H, 4.52; N, 9.67.

5.3.19 1-N-methyl-spiro[2.3′]oxoacenaphthylen-2yl)-spiro[3.5″]-5-bromo((1-(4-chlorophenyl))- 1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)methyl)indolin-2-one- pyrrolizidine (6i)

Yellow solid; M.p.: 252–254 °C; Yield 83%; 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 2.15–2.17 (m, 2H, CH2), 2.20–2.30 (m, 1H, C–H), 2.58–2.60 (m, 2H, CH2), 2.78–2.83 (m, 1H, C–H), 4.07 (d, 1H, N-CH2, J = 15.9 Hz), 4.29 (d, 1H, NCH2, J = 15.9 Hz), 4.70–4.90 (m, 1H, C–H), 5.46 (d, 1H, C–H, J = 8.7 Hz), 6.79–7.98 (m, 17H, Ar-H), 8.14 (s, 1H, Ar-H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 208.3, 198.3, 171.6, 167.6, 141.0, 140.5, 137.4, 135.0, 134.8, 132.7, 132.1, 131.9, 130.9, 130.8, 130.4, 129.8, 129.6, 128.8, 128.2, 128.1, 128.0, 124.8, 122.4, 122.0, 120.1, 115, 80.1, 68.4, 66.3, 55.4, 46.6, 34.7, 31.3, 30.6; IR (KBr, cm−1): νmax = 1635,1734, 1743; CHN Anal. Calcd for C41H29BrClN5O3: C, 65.22; H, 3.87; N, 9.28. Found: C, 65.26; H, 3.98; N, 9.41.

5.3.20 1-N-methyl-spiro[2.3′]oxoacenaphthylen-2yl)-spiro[3.5″]-5-bromo((1-(4-nitrophenyl))-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)methyl)indolin-2-one- pyrrolizidine (6j)

Yellow solid; M.p.: 254–256 °C; Yield 81%; 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 2.15–2.17 (m, 2H, CH2), 2.20–2.30 (m, 1H, C–H), 2.58–2.60 (m, 2H, C H2), 2.78–2.83 (m, 1H, C–H), 4.07 (d, 1H, N-CH2, J = 15.9 Hz), 4.29 (d, 1H, NCH2, J = 15.9 Hz), 4.70–4.90 (m, 1H, C–H), 5.46 (d, 1H, C–H, J = 8.7 Hz), 6.79–8.40 (m, 17H, Ar-H), 8.14 (s, 1H, Ar-H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 207.6, 198.2, 171.5, 160.0, 156.7, 152.8, 142.4, 140.7, 132.5, 132.2, 131.8, 130.7, 130.4, 129.8, 129.0, 128.1, 127.9, 124.7, 122.5, 122.2, 119.9, 119.2, 115.3, 114.5, 76.5, 68.5, 66.3, 55.6, 46.6, 34.8, 31.3, 30.4; IR (KBr, cm−1): νmax = 1639,1730, 1742; CHN Anal. Calcd for C41H29BrN6O5: C, 64.32; H, 3.82; N, 10.98. Found: C, 64.36; H, 3.95; N, 11.12.