1. Introduction

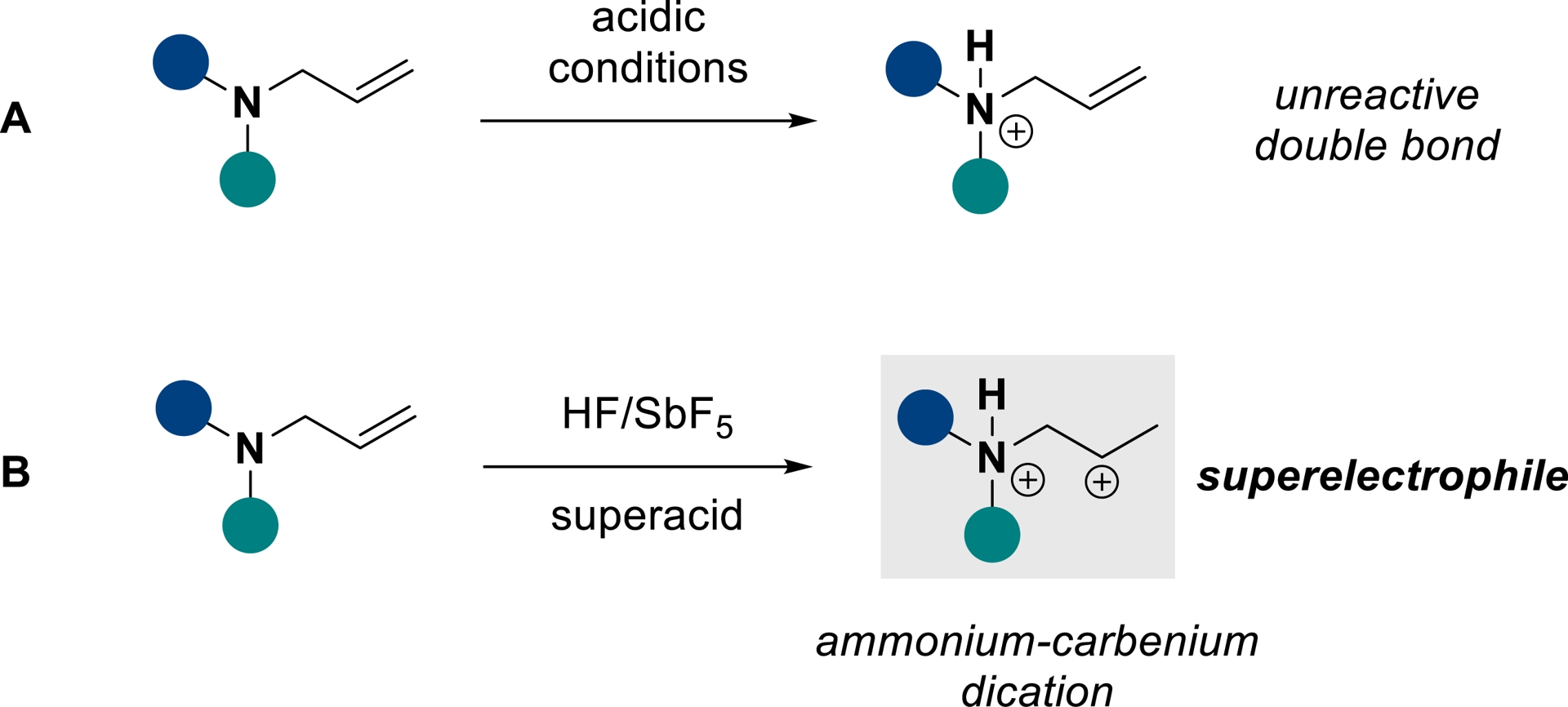

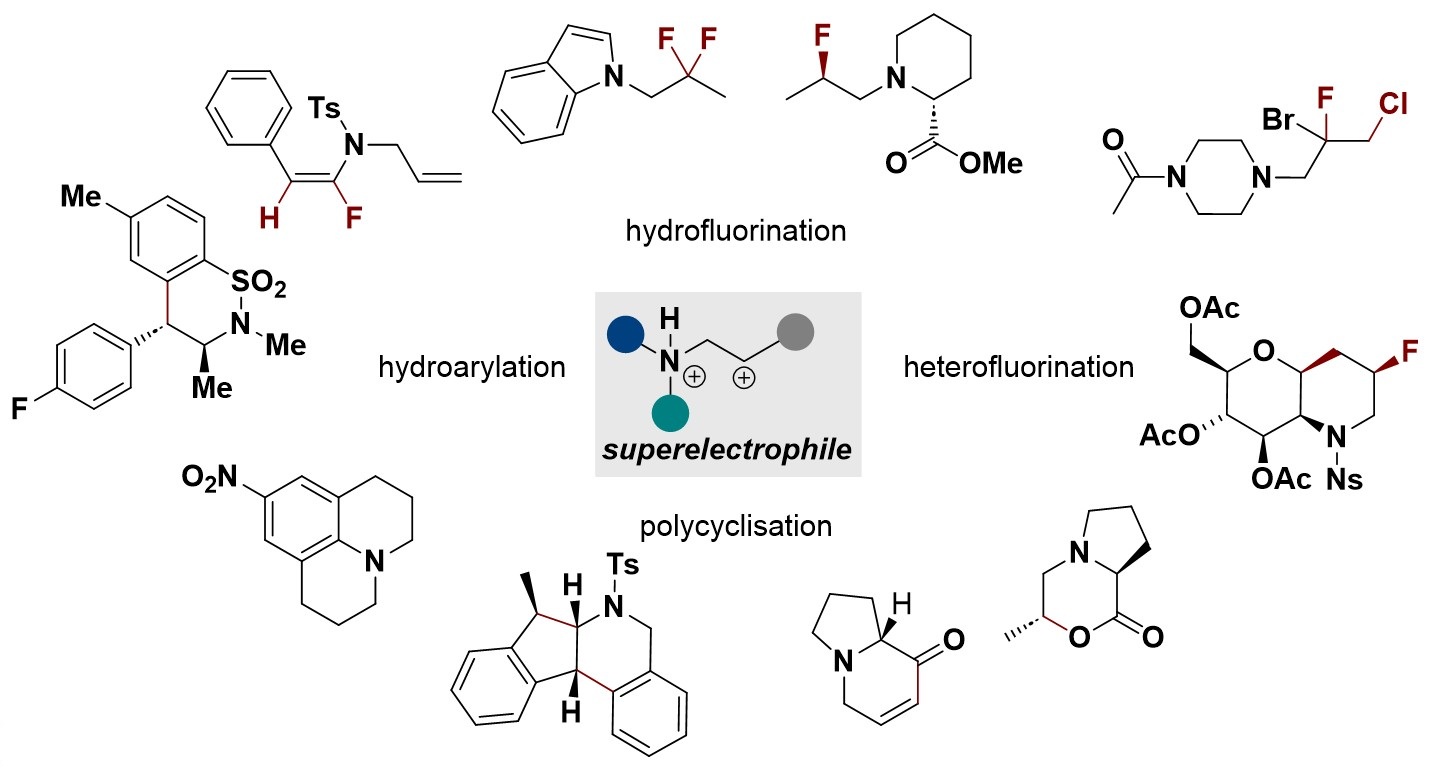

The hydrofunctionalization of N-containing alkenes and alkynes represents an attractive, atom-economical approach to furnish linear or heterocyclic nitrogen-containing molecules, which are widespread moieties in the pharmaceutical and agrochemical fields [2, 3, 4]. Nonetheless, applying this strategy to unsaturated amines remains limited because of the electronic deactivation of the unsaturated C–C bond after protonation of the amino group under acid conditions (Scheme 1A). Over the past decades, our group has shown that the use of superacid activation can enhance the reactivity of such substrates, which allows us to overcome this obstacle.

N-allylamines activation in classical acidic conditions vs superacidic conditions (adapted/redrawn from [1]).

The term “superacid” was first mentioned in the literature by Hall and Conant [5]. However, it was only in the 1960s that George Olah brought it up to date when his work was focused on the use of highly acidic non-aqueous systems for studying long-lived carbocations using NMR spectroscopy [6]. The significant contribution of George Olah in carbocation chemistry has been later recognized with his attribution of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1994 [7]. In 1971, Gillespie arbitrarily defined the Brønsted superacids as non-aqueous systems having an acidity equal or greater than that of 100 wt% sulfuric acid [8]. This can be quantified using the Hammett acidity scale with H0 values lower than −12 [9, 10]. Since then, a wide range of superacid media have been studied including pure liquid Brønsted superacids and their combinations with various Brønsted or Lewis acids [6]. The strongest superacid systems are composed of hydrogen fluoride and antimony pentafluoride (HF/SbF5) with Hammett acidities that could reach H0 values down to −24 [11]. Under these highly acidic conditions, functionalized organic substrates can be mono- or polyprotonated leading to original reactivity (Scheme 1B). Through the addition of a positive charge (or electron deficiency) close to them, the generated cations show increased electron deficiency and enhanced electrophilic character (superelectrophilic activation) allowing reactions with poor nucleophilic partners [12, 13, 14, 15].

Although other contributions allowed the development of elegant strategies, especially hydroarylation [16, 17, 18, 19], this report only accounts for the use of superacid-promoted hydrofunctionalization to generate fluorinated N-containing compounds.

2. Hydrofluorination of unsaturated N-containing derivatives

The use of fluorine atom(s) to enhance therapeutic efficiency and improve pharmacological properties of a drug is a well-established strategy as shown by the number and diversity of fluorine-containing pharmaceuticals commercially available [20, 21, 22]. This success can be directly related to the many effects that the fluorine atom(s) and fluorinated moieties can exert on the biological and physicochemical properties of a molecule [23, 24]. Thanks to these benefits, fluorine is now “the second-favorite heteroatom” after nitrogen in drug design [25], in particular in order to tune amine basicity to play with the penetration and bioavailability of a molecule [26, 27]. In this context, the development of new synthetic pathways to further extend the scope of fluorinated N-containing building blocks is of a high interest.

In this effort, hydrofluorination of unsaturated amines can be envisaged as a direct route to monofluorinated amines. However, radical hydrofluorination compatible with a wide range of substrates has never been applied to unprotected amines [28, 29] and Pd-catalyzed hydrofluorination is inefficient with amine substrates [30]. Moreover, the use of Olah’s reagent (HF∙pyridine 9:1) with unsaturated amines is limited to very few examples in the literature with relatively modest yields [31, 32, 33, 34, 35], which could be directly related to the electronic deactivation of the unsaturation after protonation of the amino group, and neither gold catalysis [36, 37] nor designed HF-based fluorination reagents can overcome this obstacle [38].

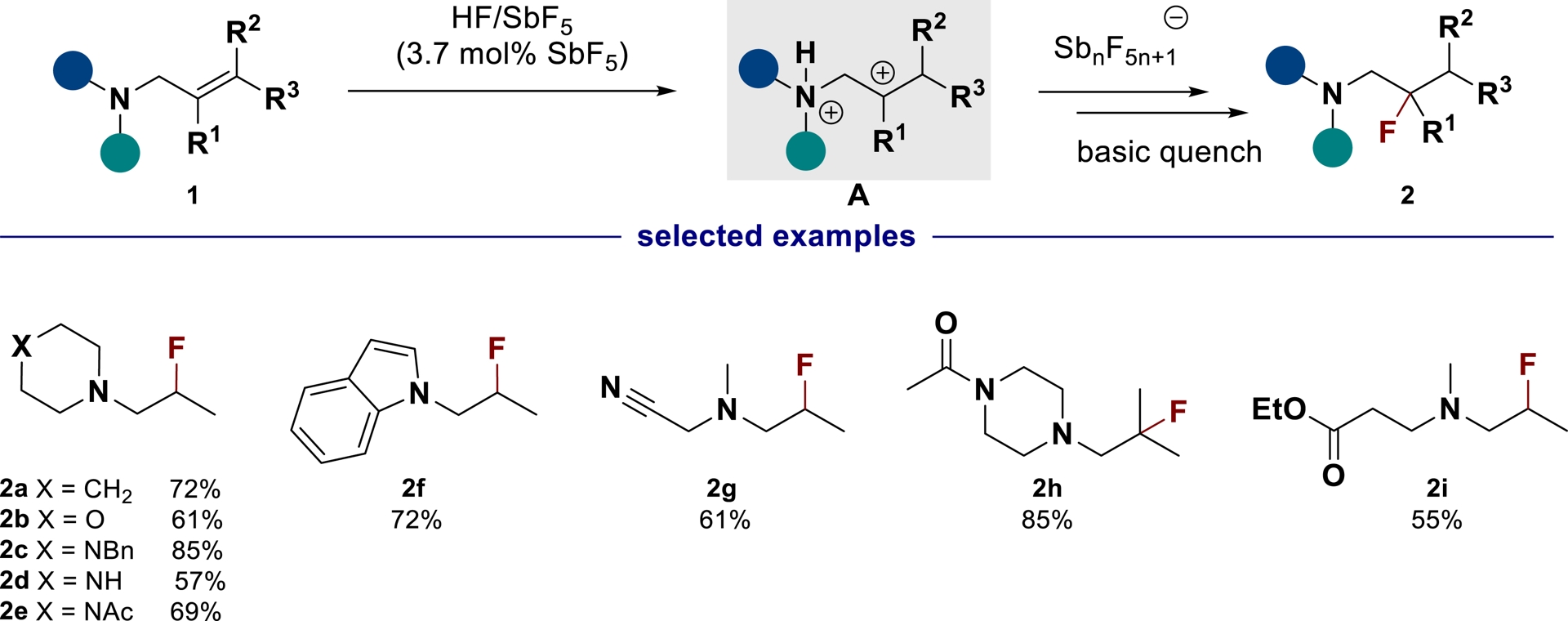

In superacid HF/SbF5, amine 1 can undergo a subsequent protonation of the alkene moiety to form ammonium–carbenium dication A (Scheme 2). While the “non-coordinating” properties of fluoroantimonate anions were largely exploited in catalysis to tune catalyst properties [39], ammonium–carbenium superelectrophilic activation overcomes the non-coordinating anions’ properties [40]. The electron-withdrawing effect of the proximal protonated nitrogen-based group enhances the superelectrophilic character of the dication A, allowing its trapping by $\mathrm{SbF}_{6}^{-}$ or $\mathrm{Sb}_2\mathrm{F}_{11}^{-}$ anions [41, 42], resulting in the formation of the corresponding fluorinated amines 2 in good yields [43, 44].

Hydrofluorination of unsaturated amines in superacidic conditions (adapted/redrawn from [1]).

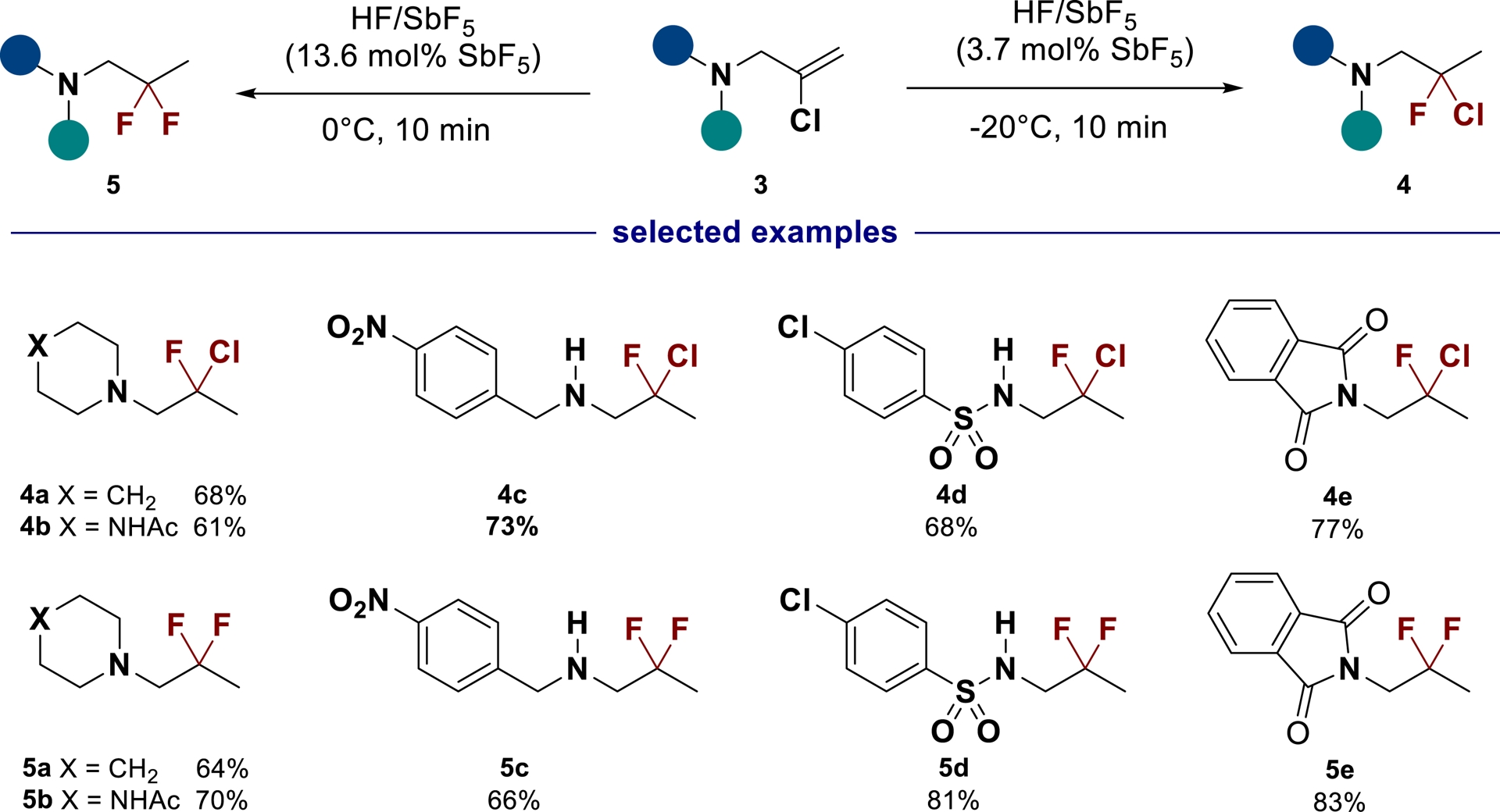

Gem-chlorofluorinated N-containing derivatives 4 (successfully applied to amines, amides, sulfonamides and imides with good yields 68–83%) at −20 °C or the corresponding gem-difluorinated products 5 under more acidic conditions at 0 °C can be easily obtained by applying the previously described method to chlorine-substituted olefins 3 (Scheme 3) [45].

Synthesis of gem-chlorofluorinated and gem-difluorinated N-containing derivatives in HF/SbF5 (adapted/redrawn from [1]).

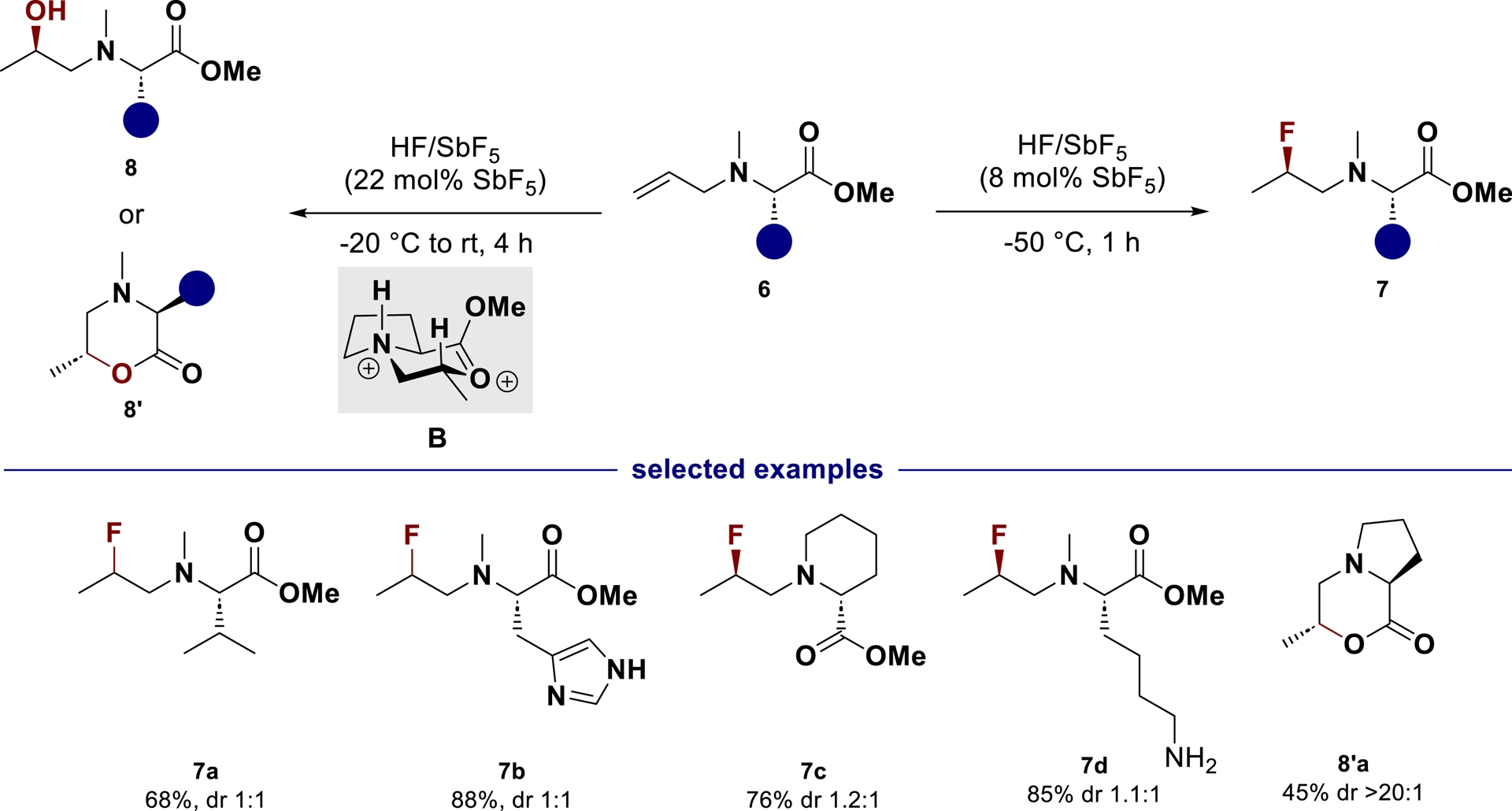

We have recently explored this strategy for the diastereoselective hydrofunctionalization of allylic amines derived from natural amino acids [46]. In this case, the reaction mechanism involves the accumulation of chiral cyclic ammonium–carboxonium dications after a tandem diastereoselective proton transfer/intramolecular cyclization from N-allyl substituted amino esters (Scheme 4). The latter can then react inter- or intramolecularly to furnish fluorinated amines 7, amino alcohols 8 or amino lactones 8′ depending on the reaction conditions. The diprotonation of unsaturated amino esters followed by a concerted diastereoselective proton-transfer/cyclization with full diastereocontrolled formation of a chiral lactone 8a′ from a L-proline-derived substrate confirms the persistency of a well-tuned chiral dication B which should open interesting synthetic perspectives.

Reactivity of N-allyl amino esters in HF/SbF5.

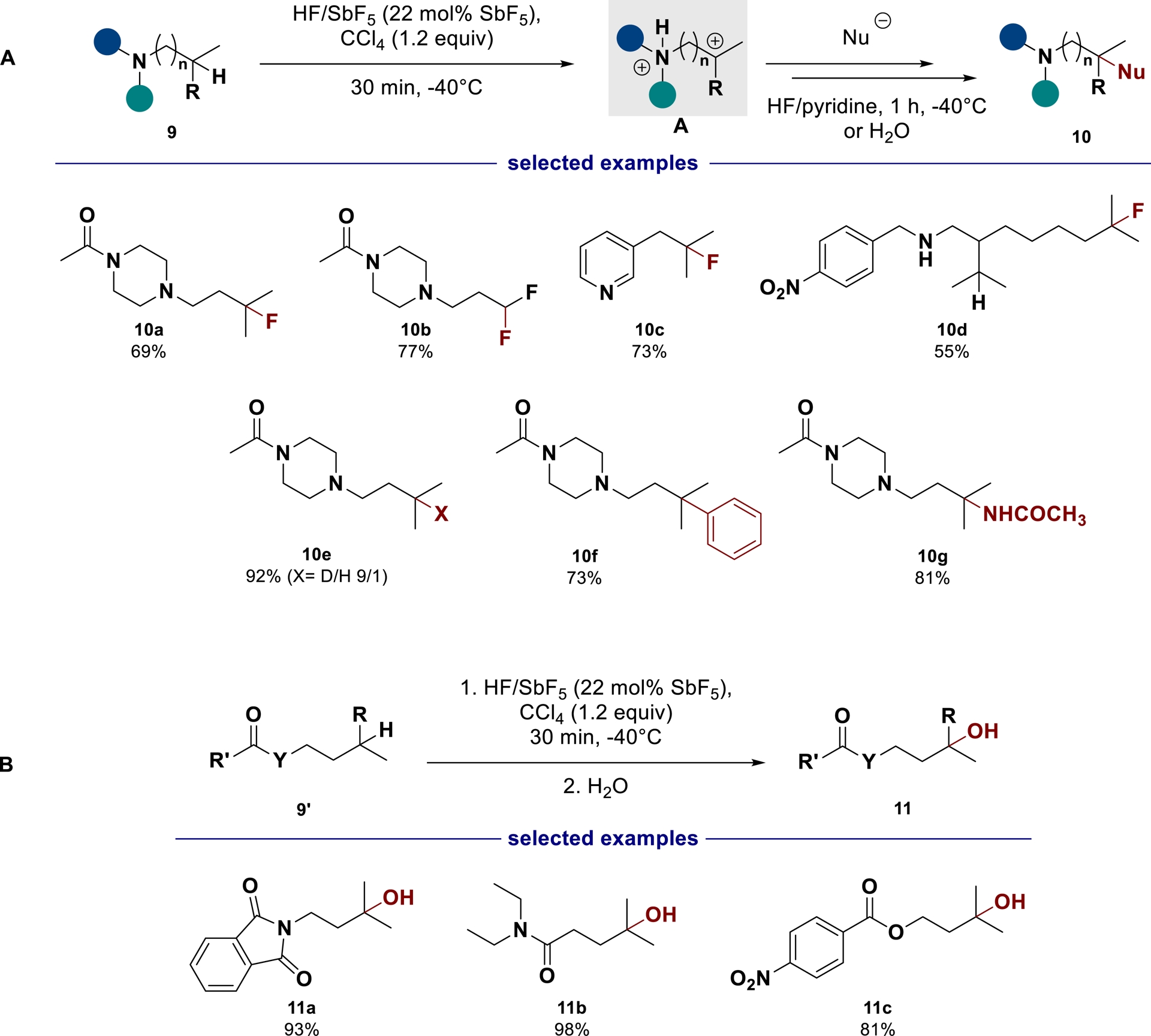

Alternatively, the synthesis of fluorinated amine derivatives can also be achieved from saturated substrates through the superelectrophilic C(sp3)–H bond fluorination of aliphatic amines in superacid [47]. Indeed, by using the hydride abstraction capabilities of CCl$_{3}^{+}$ species in HF/SbF5 conditions [48], we developed a direct strategy to fluorinate unactivated C(sp3)–H bonds of terminal isopropyl moieties in aliphatic amines with moderate to fair yields. This method was also used to introduce other nucleophiles, allowing arylation, amination, and deuteration (Scheme 5A). Extended to amides and esters, the superacid-promoted electrophilic activation can be exploited to generate alcohols 11 in a selective way (Scheme 5B).

(A) Superelectrophilic C(sp3)–H bond functionalization of aliphatic amines in superacid; (B) Superelectrophilic C(sp3)–H bond hydroxylation of aliphatic amides and esters in superacid.

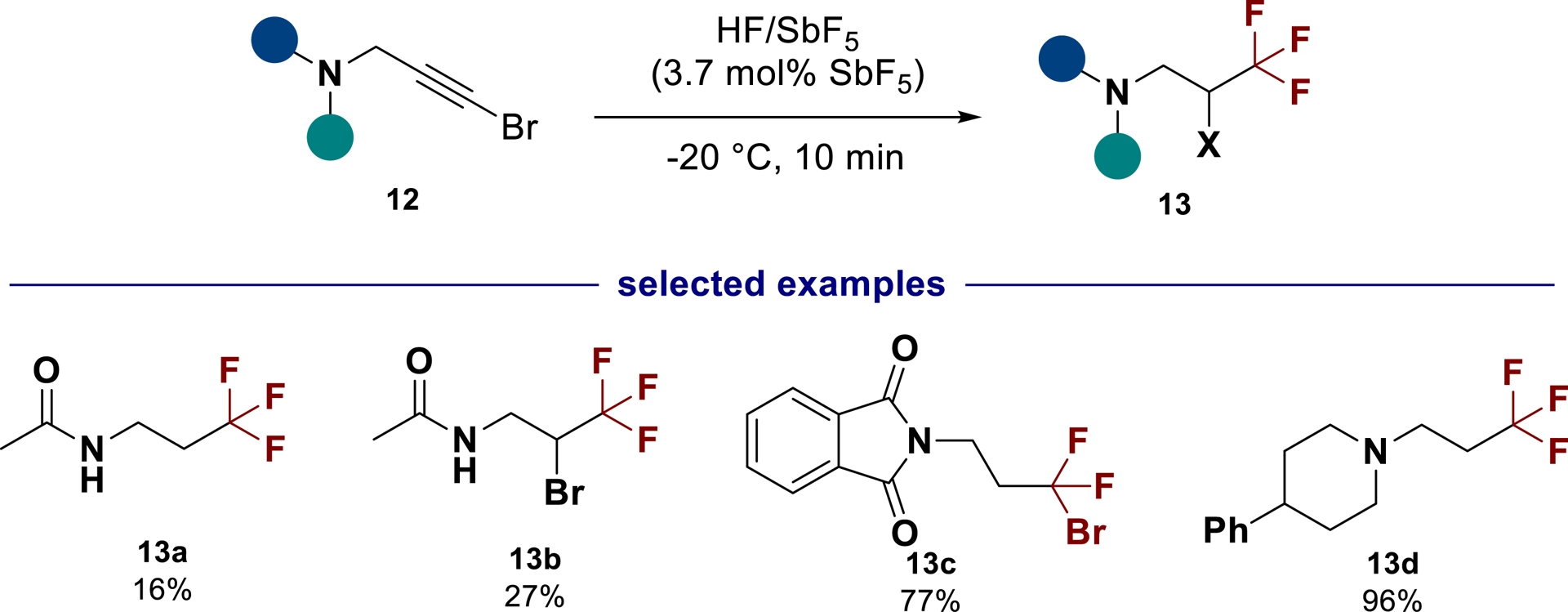

The hydrofluorination reaction in HF/SbF5 can also be applied to alkynes. Starting from 1-bromopropargylic amines 12, the trifluorinated amines 13 can be synthesized with moderate to good yields (Scheme 6). On the other hand, 1-bromodifluoroamines or 2-bromo-1,1,1-trifluorinated products may be isolated depending on the amine substitution and reaction conditions [49].

Synthesis of trifluorinated amines from 1-bromopropargylic amines in HF/SbF5.

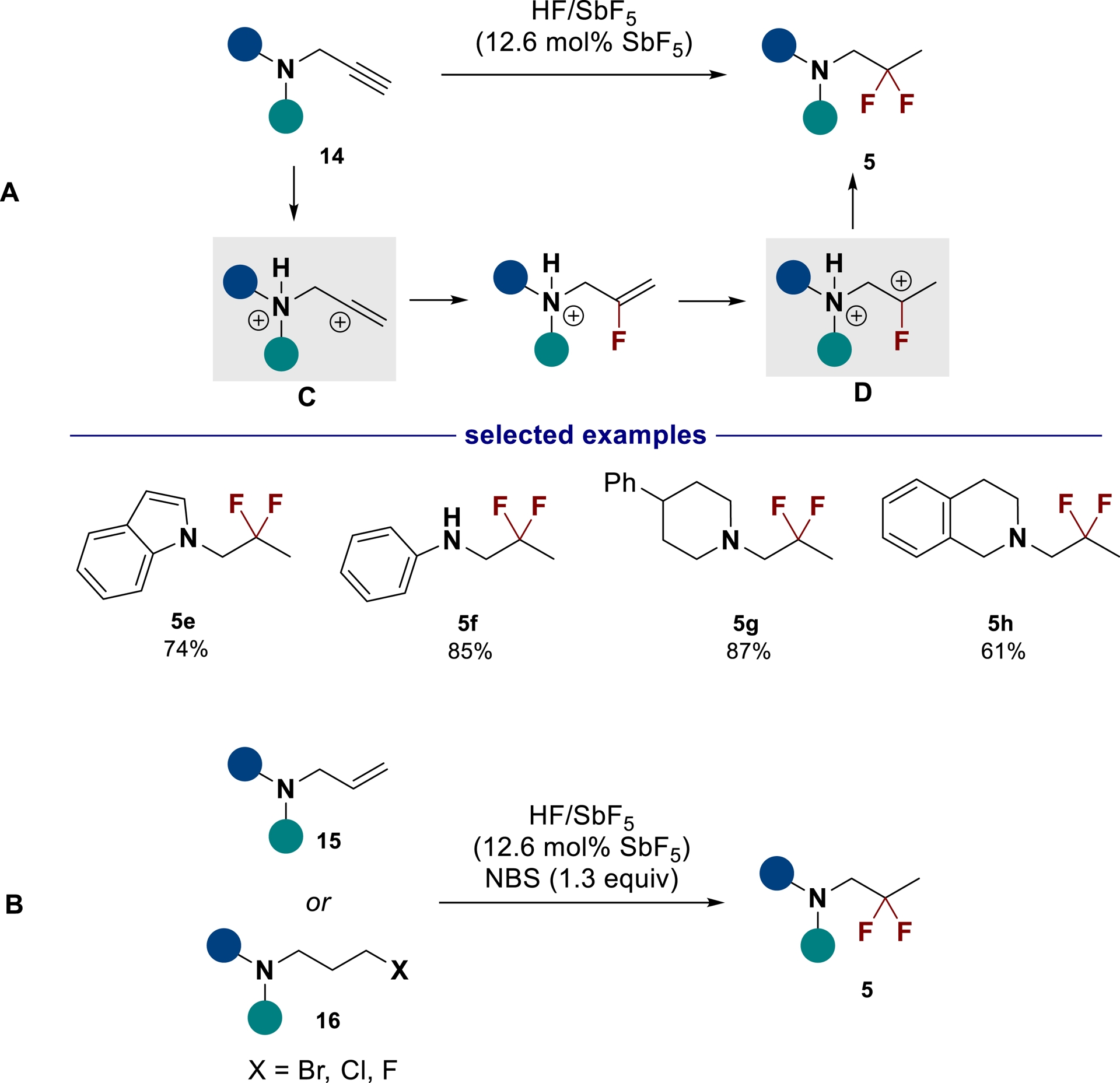

The gem-difluorination reaction can also be efficiently achieved from propargylic amines 14 in HF/SbF5 through the successive formation of dicationic superelectrophiles C and D to afford the gem-difluorinated products in good yields (Scheme 7A) [50]. As an alternative method, the gem-difluorinated amine derivatives could also be obtained through oxidative gem-difluorination in the presence of N-bromosuccinimide (NBS) from allylic or haloamines (Scheme 7B).

Synthesis of gem-difluorinated amines in HF/SbF5 starting from propargylic amines (A) or from allylic and haloamines (B) (adapted/redrawn from [1]).

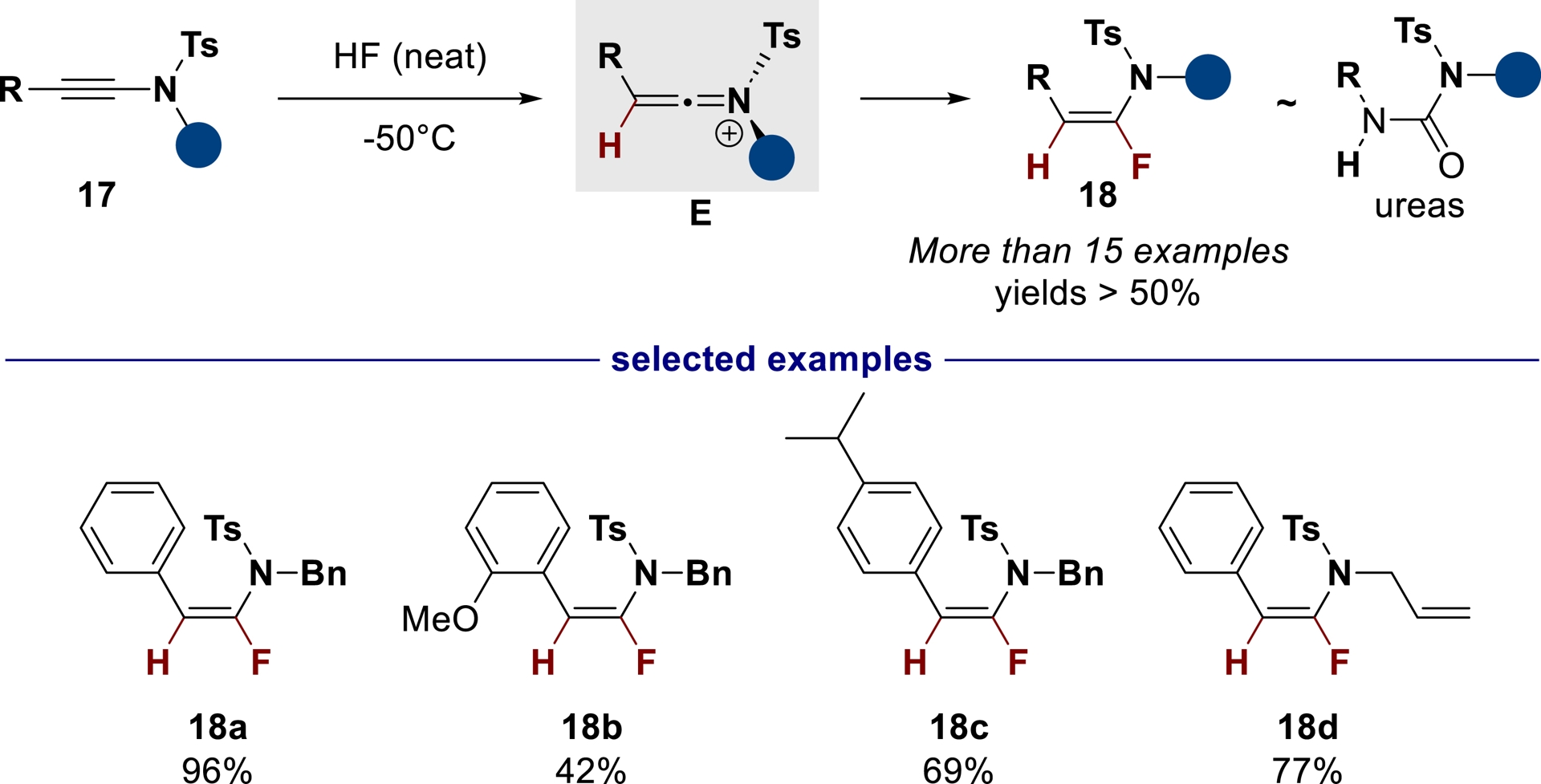

Over the past decades, because of their singular physicochemical features [51], ureas have seen a renewed interest in chemistry-related fields with remarkable applications (organocatalysts [52, 53], anion chemosensors [54, 55], and artificial membranes [56, 57]). Furthermore, the recent development of urea-based anticancer compounds [58, 59] highlights their potential as key structural elements and/or pharmacophores in medicinal chemistry. Thus, generating bioisosters from this functional group is an area of interest for the pharmaceutical industry [60, 61, 62]. Considering the well-known bioisosterism between fluoroolefins and amides [63] and the scarcity of reported urea bioisosters in SAR studies [64, 65, 66], we have developed, in collaboration with the Evano group, the first stereoselective hydrofluorination of ynamides 17 in HF as an entry to α-fluoroenamides 18, potent urea bioisosters (Scheme 8) [67]. In neat HF conditions, after protonation, extremely reactive keteniminium intermediates E can be further stereoselectively fluorinated (sterically-favored incoming approach of the fluorinating agent) to produce fluoroenamides 18 in excellent yields. A similar reaction can also occur in HF/pyridine systems [68], prompting us to develop a semi-empirical approach to determine the acidity of HF/base mixtures [69].

Hydrofluorination of ynamides in neat HF (adapted/redrawn from [1]).

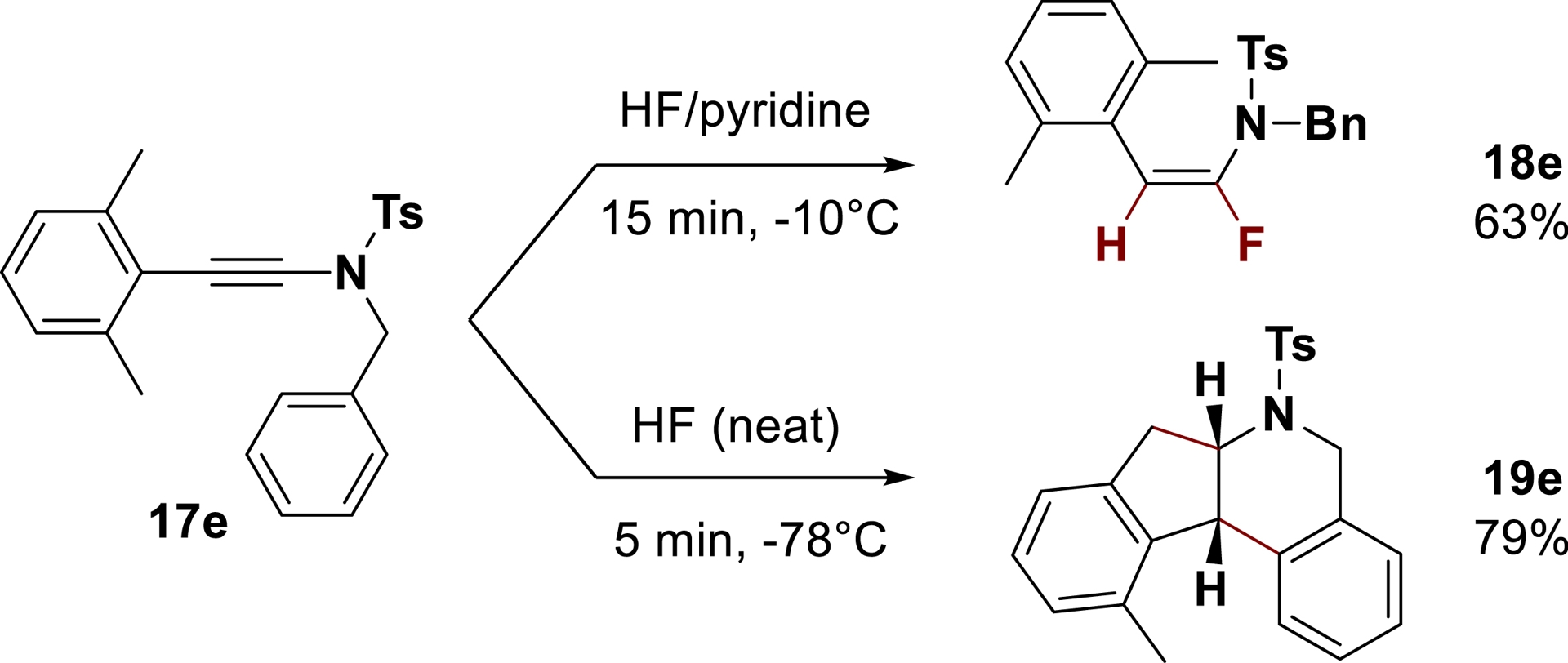

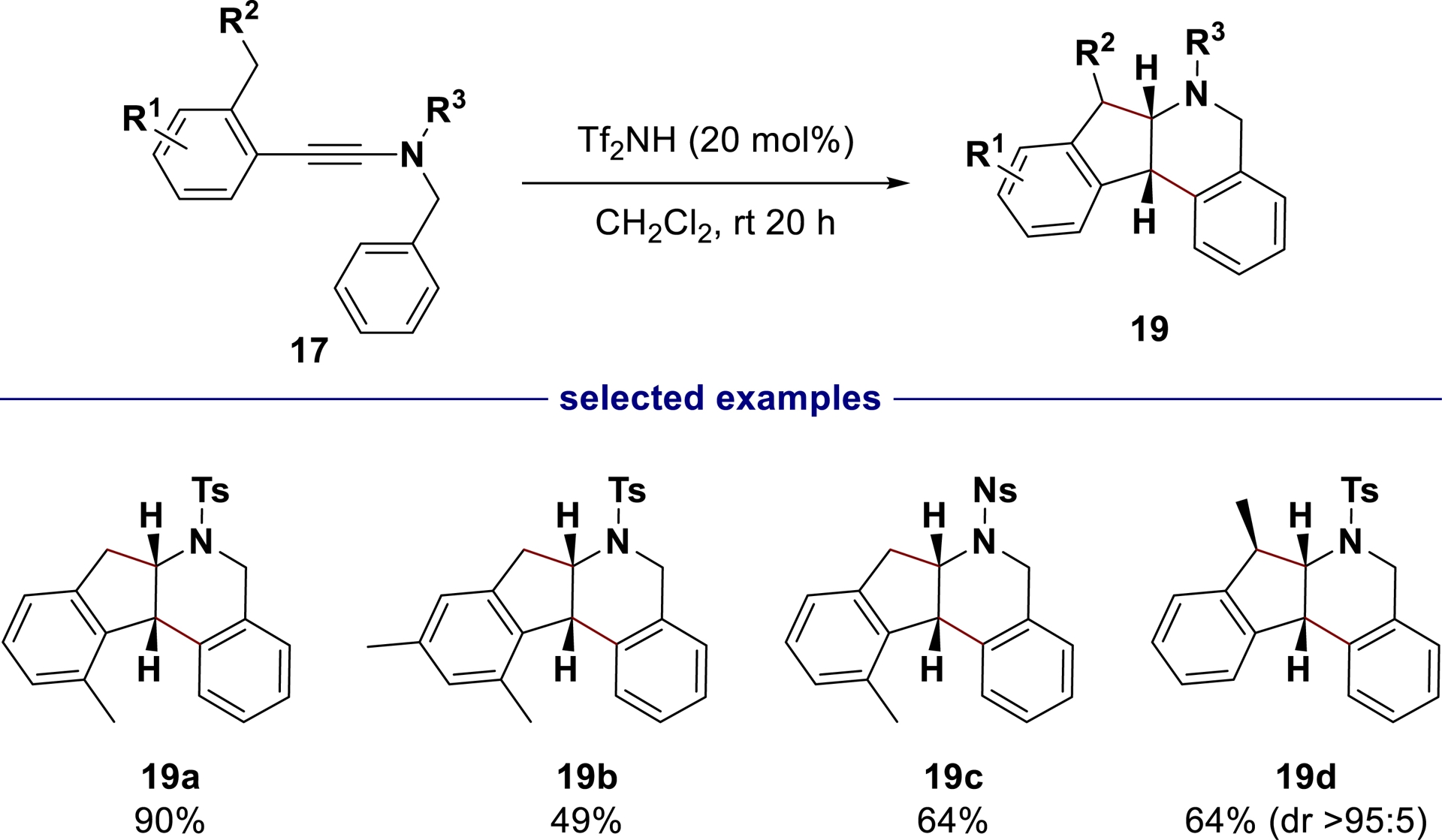

Surprisingly, while the targeted fluoroenamide 18e was isolated in 63% yield from ynamide 17e after reaction at −10 °C in HF/pyridine, the tetracyclic compound 19e was generated at −78 °C in neat HF as a single diastereomer in 79% yield (Scheme 9) [70]. With these unexpected results in hand, various acids were screened to further optimize the reaction conditions. The use of triflic acid (TfOH) as well as catalytic amounts of bistriflimidic acid (Tf2NH) in CH2Cl2 provided selectively the polycyclic product 19e in 90% yield. The method designed was exemplified to a large range of substrates (more than 15 examples) with good yields and was successfully applied to chiral ynamides and bis-ynamides, allowing larger molecular diversity of the reaction.

Behavior of ynamides 17e in HF/pyridine vs HF conditions (adapted/redrawn from [1]).

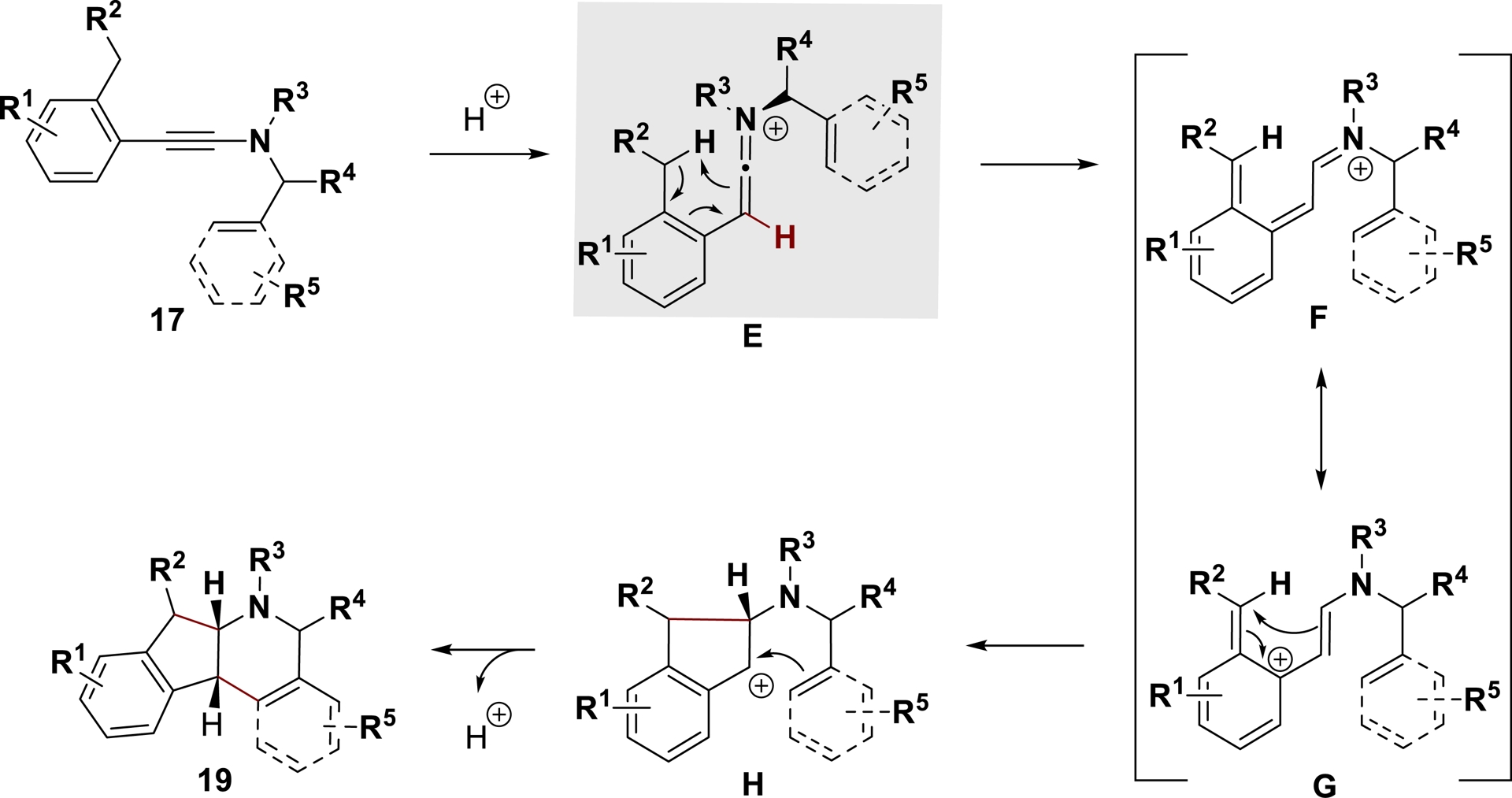

The following mechanism was hypothesized based on a series of experiments using deuterated substrates and reactants, as well as DFT calculations, to justify the original cationic polycyclization of ynamides (Scheme 10). The keteniminium ion E is generated first, followed by a [2, 6]-sigmatropic hydrogen shift from the intermediate F (in resonance with the bis-allylic carbocation G). The first cycle would be generated by a diastereoselective 4π conrotatory electrocyclization, resulting in H. The tetracycle and its cis ring junction would then be formed via a final cyclization of the benzylic cation H.

Proposed mechanism for the polycyclization of ynamides in HF (adapted/redrawn from [1]).

Having demonstrated that this polycyclization could be conducted with catalytic amounts of bistriflimidic acid (Tf2NH, 20 mol% in CH2Cl2), the method was applied to a range of ynamides derivatives 17 (Scheme 11).

Selected examples of N-containing chiral tetracycles 19 generated from ynamides 17 in the presence of catalytic amounts of Tf2NH (adapted/redrawn from [1]).

3. Heterofluorination of unsaturated N-containing derivatives

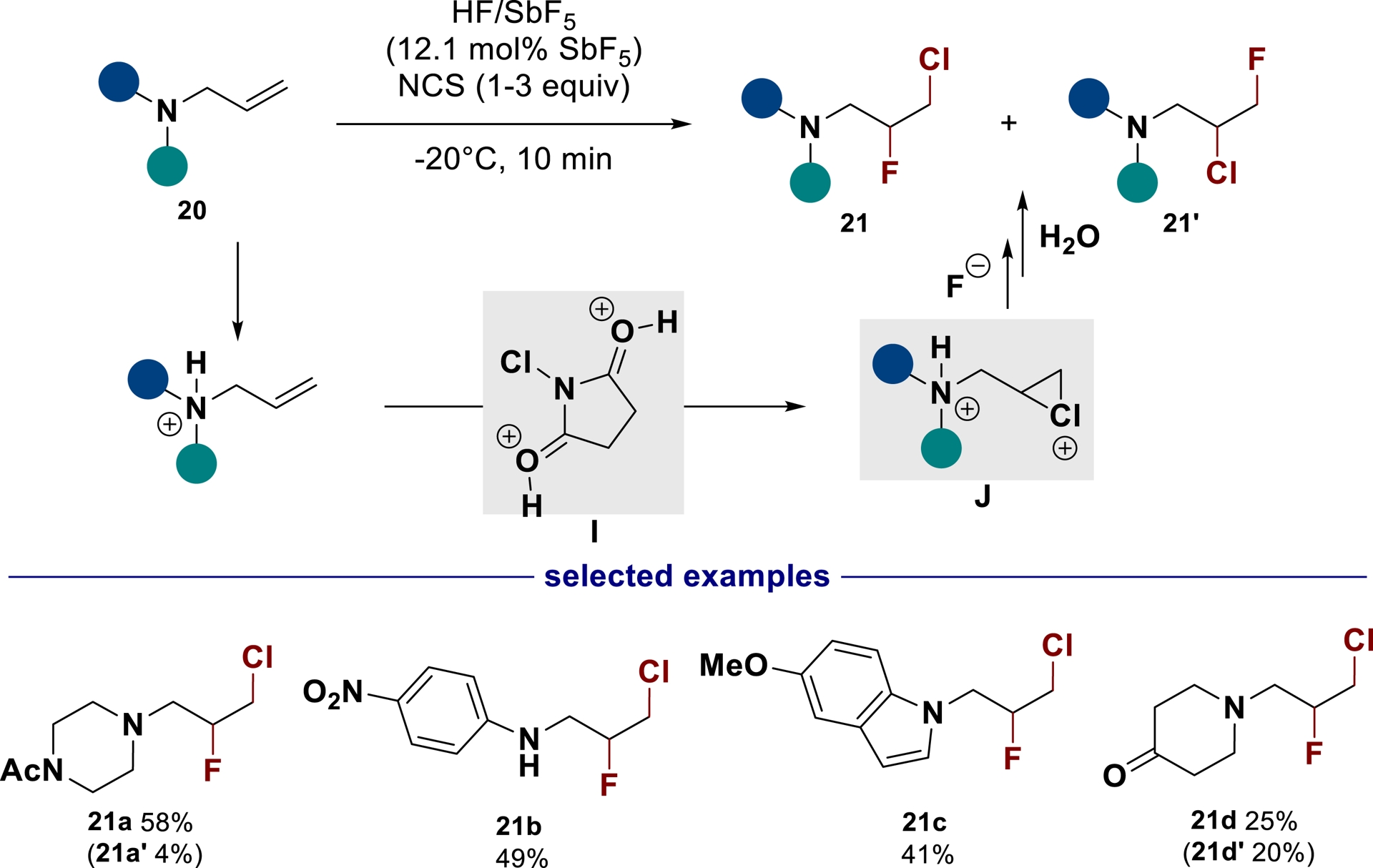

Following our interest in the synthesis of fluoroamine derivatives, we also became interested in the halofluorination of unsaturated amines. While electrophilic activation of alkenes by halonium ion addition has been widely employed to produce new C–C, C–O, C–N, and C–X bonds [71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77], its application to the halofluorination of allylic amine derivatives is limited to few examples [31, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83]. The combination of HF/base and N-halosuccinimide (NXS) reagents is particularly efficient for the halofluorination of C=C double bonds, although it is significantly less efficient on allylic amine derivatives. Again, the fundamental challenge in applying chlorofluorination to unsaturated amines is the significant decrease in nucleophilicity of the double bond after protonation of the amino group, which prohibits any interaction with a halonium ion source [84]. In this regard, tandem superelectrophilic activation of unsaturated nitrogen-containing compounds with N-chlorosuccinimide (NCS) was discovered to be a useful alternative to address this difficulty (Scheme 12) [85]. In superacid, the classical chloronium ion source NCS can be activated through the protonation of both carbonyl groups as showed by low temperature NMR experiments. In these conditions, NCS—activated as superelectrophilic species (I)—is reactive enough to allow the formation of chloronium ion J from amine 20. The fluorination of this chloronium ion leads to the corresponding β-fluoro-γ-chlorinated amine 21. This method was found to be compatible with a wide range of unsaturated nitrogen-containing substrates.

Synthesis of chlorofluorinated amines from N-allylamines in superacid conditions (adapted/redrawn from [1]).

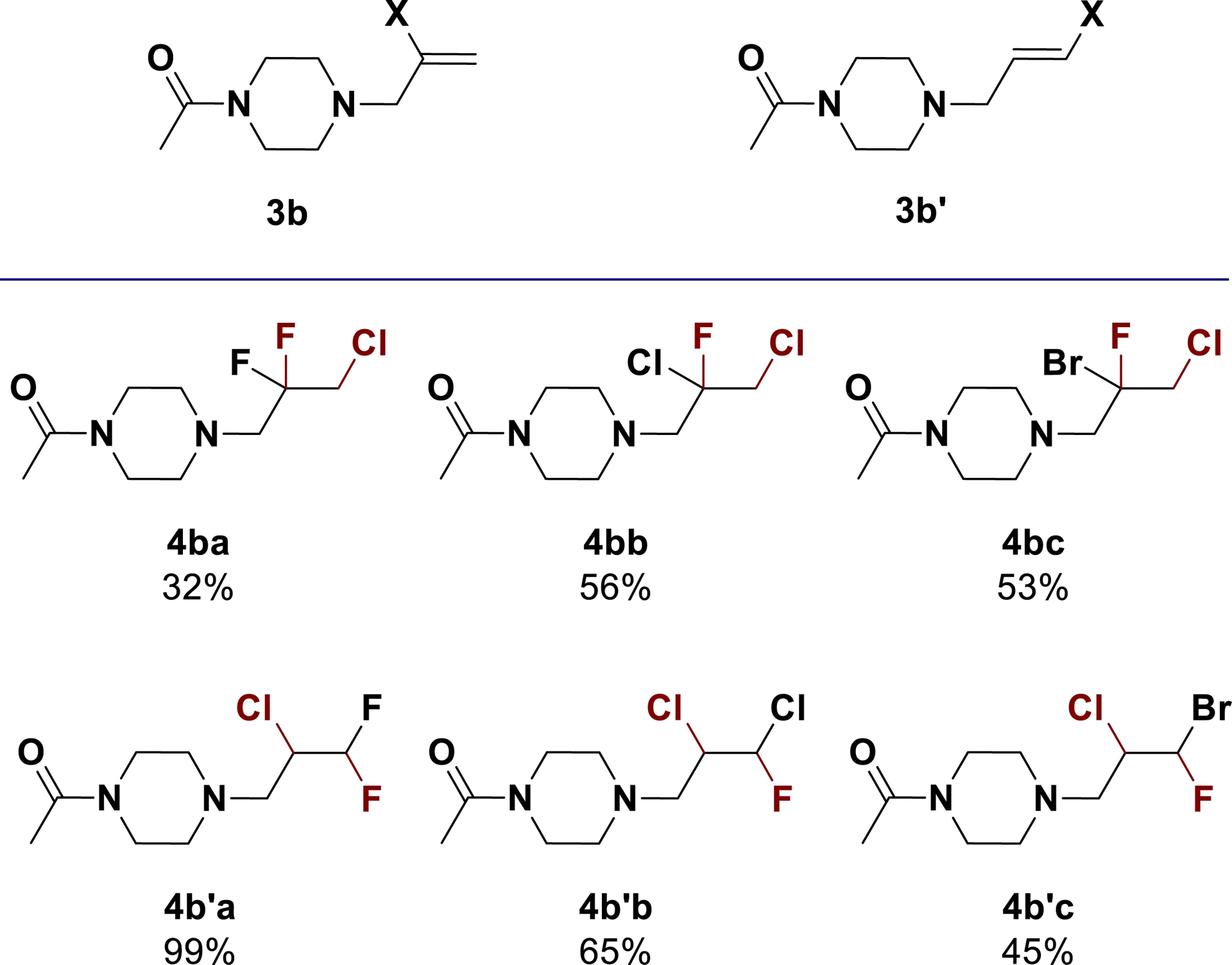

Directed by a halogen substituent on olefins 3b and 3b′, chlorofluorination demonstrated good efficiency for the synthesis of original and high-valued polyhalogenated building blocks in relatively good yields (Scheme 13).

Extension of the method to the synthesis of polyhalogenated compounds (adapted/redrawn from [1]).

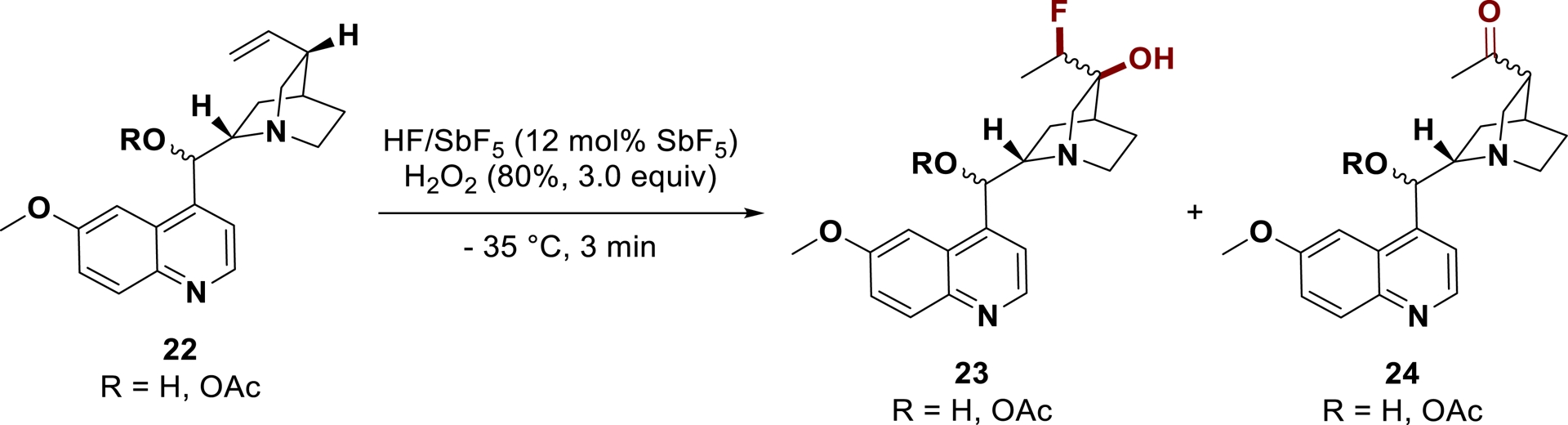

Our group has also shown that 1,2-oxyfluorination of unsaturated amines can be performed in the presence of hydrogen peroxide. Applied to elaborated unsaturated amines such as quinine derivatives 22, fluorohydrins 23 could be synthesized along with ketones 24 (Scheme 14) [86].

Oxyfluorination of quinine derivatives using superacid in the presence of oxygen peroxide.

4. Anti-Markovnikov hydroarylation of unsaturated N-containing derivatives

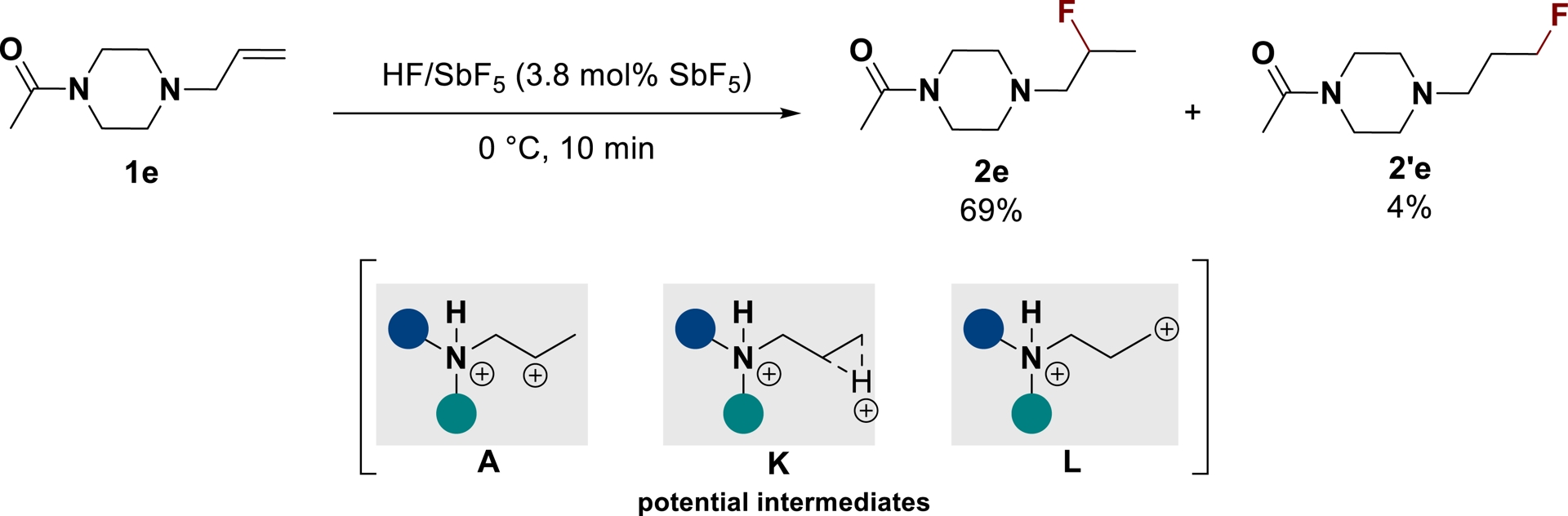

In the course of our work on superacid-mediated hydrofluorination of olefins, the unusual formation of a γ-fluorinated product 2′e besides the desired product 2e from substrate 1e led to a deep mechanistic investigation (Scheme 15) [87].

Hydrofluorination of substrate 1e in HF/SbF5 (adapted/redrawn from [1]).

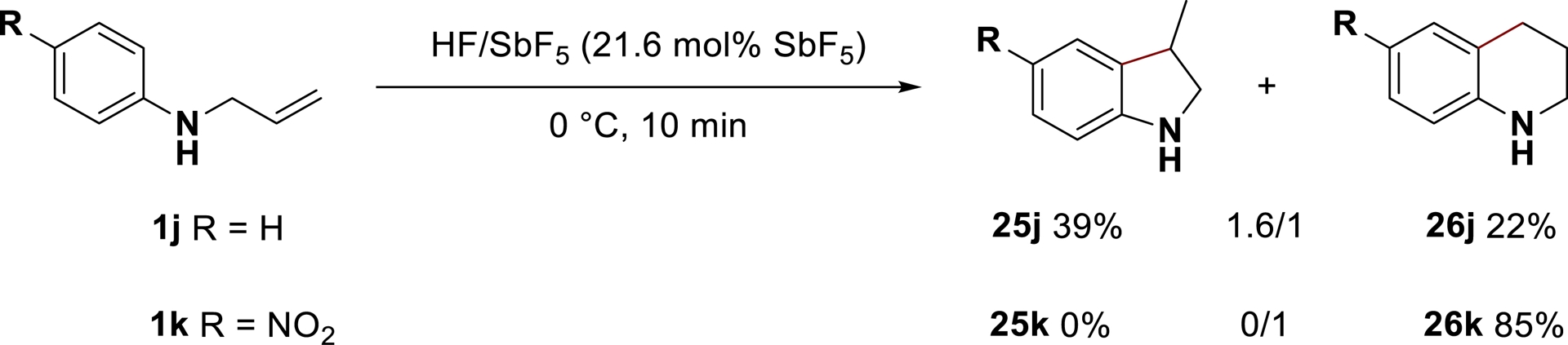

The Markovnikov product 2e and anti-Markovnikov product 2′e may respectively result from the nucleophilic trapping of the secondary carbocation A (β-position) and primary carbocation L (ω-position) [88], or from a nonclassical intermediate K (μ-hydrido-bridged structure) [89, 90]. By submitting fluorinated products 2e and 2′e to HF/SbF5, both compounds were found to be in a thermodynamic equilibrium via the C–F bond activation/carbocation formation/fluorination process under the reaction conditions. As a consequence, intramolecular trapping of the generated cationic intermediate through stable C–C bond formation was proposed. As previously stated, starting from N-allylic aniline derivatives, intramolecular trapping of the generated carbocation with aromatics enabled the synthesis of indolines 25 and tetrahydroquinolines 26, which were found to be stable under the reaction conditions. A significant difference in behavior was noticed between anilines substituted with electron-donating or electron-withdrawing groups. For example, the reaction of aniline 1j led to a mixture of products 25j and 26j in a 1:6:1 ratio while nitro-substituted substrate 1k transformed only into the tetrahydroquinoline 26k (Scheme 16).

Reactivity of N-allylanilines in HF/SbF5 (adapted/redrawn from [1]).

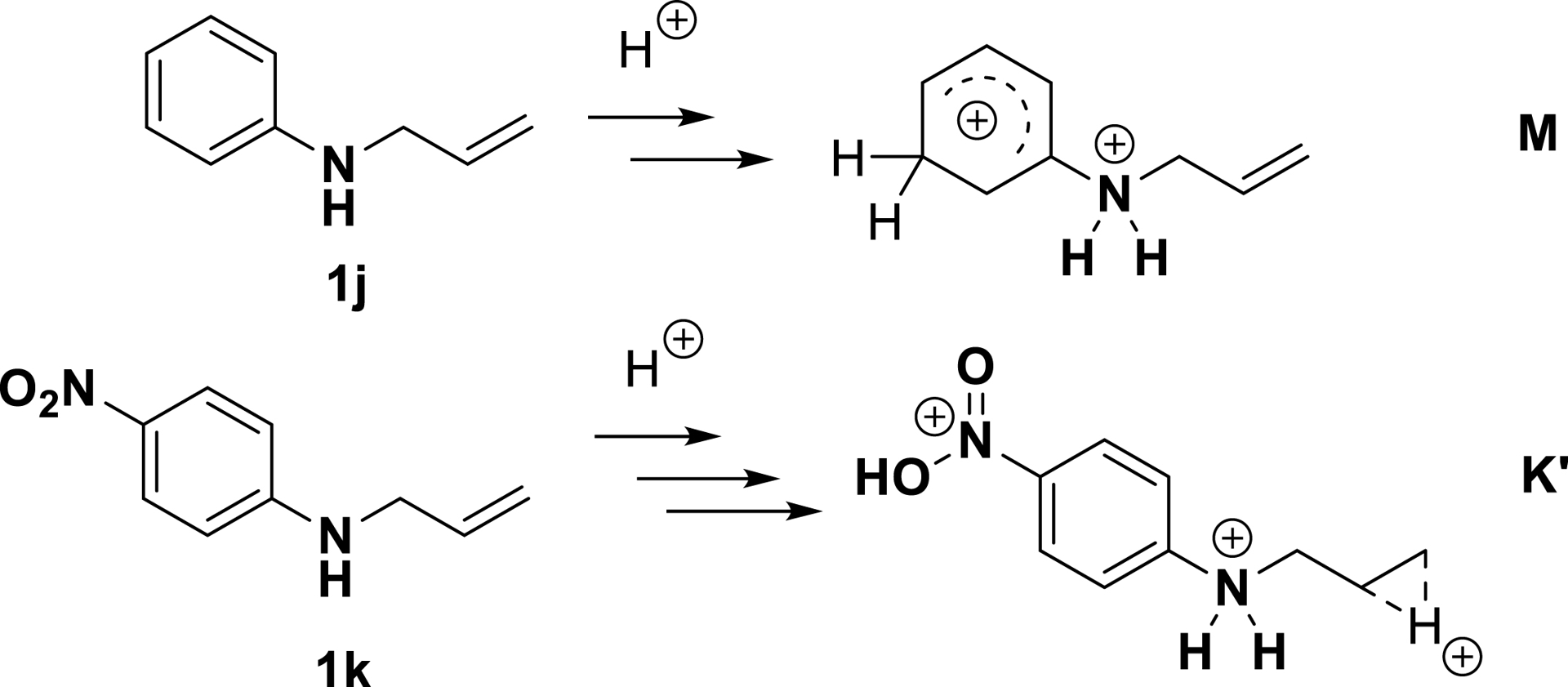

This difference in reactivity prompted us to evaluate the protonation of these substrates by DFT calculations (M06-2X level). This study revealed that the polyprotonation of “non-deactivated” aniline derivatives (anilines are partially deactivated in superacid due to nitrogen protonation) results in the formation of dicationic ammonium–arenium species M (Scheme 17). The species formed via protonation of the nitrogen atom and the C–C double bond has stationary points on the potential energy surface as well, but it is 7.7 kcal/mol more energetic. Similar calculations using 4-nitroaniline derivative 1k predicted the first protonation of the nitro group and the second protonation of the amino group. Interestingly, the computed energies suggested that further protonation on the double bond would result in a triprotonated carbenium ion (type A). This reaction was anticipated to be energetically more favorable (by over 40 kcal/mol) than aromatic ring protonation, implying that tetrahydroquinoline products would not be produced by aromatic ring protonation for deactivated substrates. A third protonation would result in a secondary carbenium ion of type A, however a second stationary point (energy minimum) was near in energy at +1.1 kcal/mol. The optimized K′ structure (Scheme 17) has a three-center two-electron bond intermediate corresponding to a symmetrically μ-hydrido-bridged species (μ-H⋯C distances: 1.33 Å, activated C=C bond length: 1.39 Å).

Proposed superelectrophilic structures in superacid based on DFT calculations (adapted/redrawn from [1]).

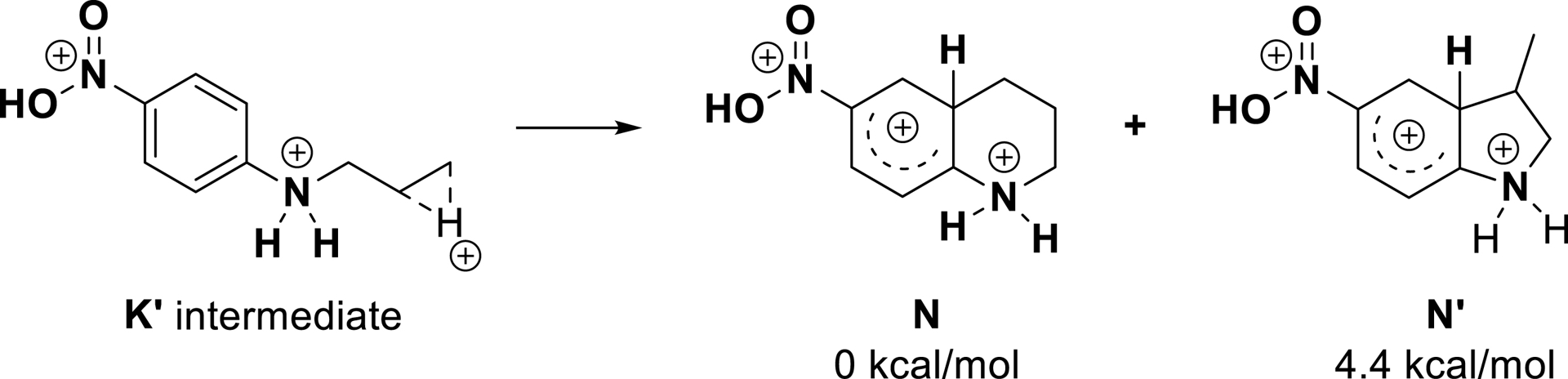

As a result, the selectivity for the production of six-membered ring products from deactivated substrates was attributed to the relative stabilities of Wheland intermediates N and N′ emerging from cyclization via trapping of intermediate K′ (Scheme 18). In the case of substrate 1k, the energy difference between intermediates N and more strained N′ is responsible for the formation of the tetrahydroquinoline product.

Structures of the Wheland intermediates of substrate 1k (adapted/redrawn from [1]).

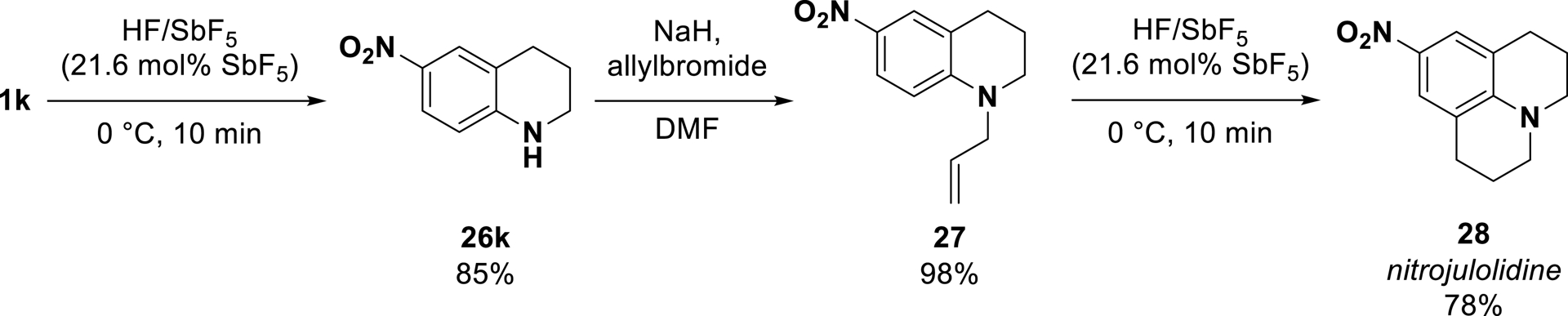

This anti-Markovnikov process was then used to prepare nitrogen-containing polycyclic molecules [91]. Starting from substrate 1k, through a tandem cyclization/allylation/cyclization process, the nitro-substituted julolidine 28 was synthesized in an overall yield of 65% (Scheme 19).

Application of the method to the synthesis of nitrojulolidine 28 (adapted/redrawn from [1]).

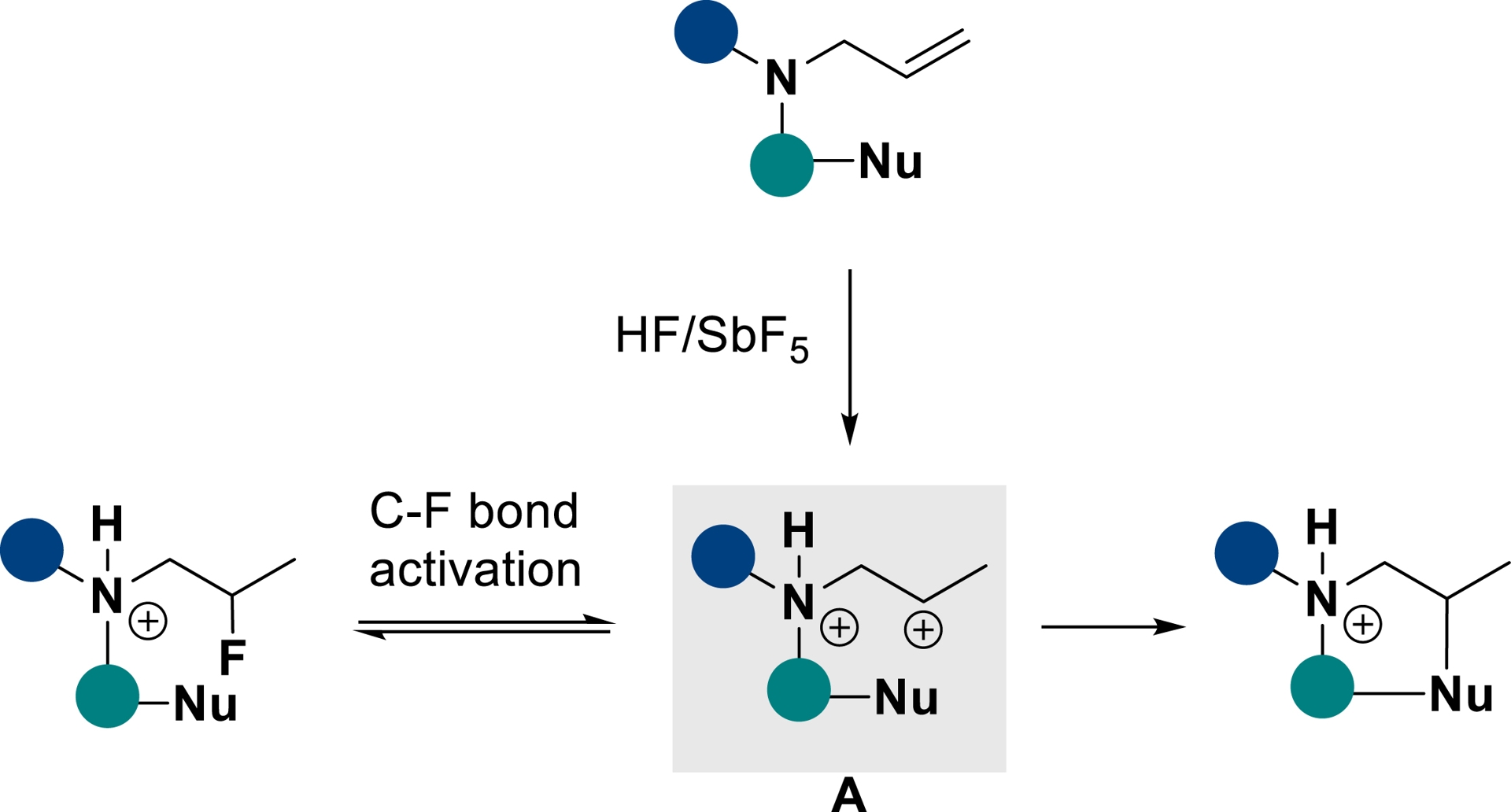

As mentioned earlier, the capability of superelectrophiles to react with poor nucleophiles can be exploited not only in hydrofluorination reactions. Indeed, depending on the superacid conditions, C–F bonds can be activated (SbF5 loading ⩾ 13.6 mol%), thus displacing the equilibrium toward the formation of an ammonium–carbenium intermediate A, prone to be quenched intramolecularly (Scheme 20).

C–F bond activation and intramolecular trapping of ammonium–carbenium dications in HF/SbF5 (adapted/redrawn from [1]).

Since the discovery of sulfa drugs and their antibiotic and antibacterial properties [92], sulfonamides and sultams have gained popularity in SAR investigations in medicinal chemistry research with numerous applications [93, 94, 95, 96, 97, 98]. As a consequence, diversifying the synthetic route for their preparation found a strong interest [99].

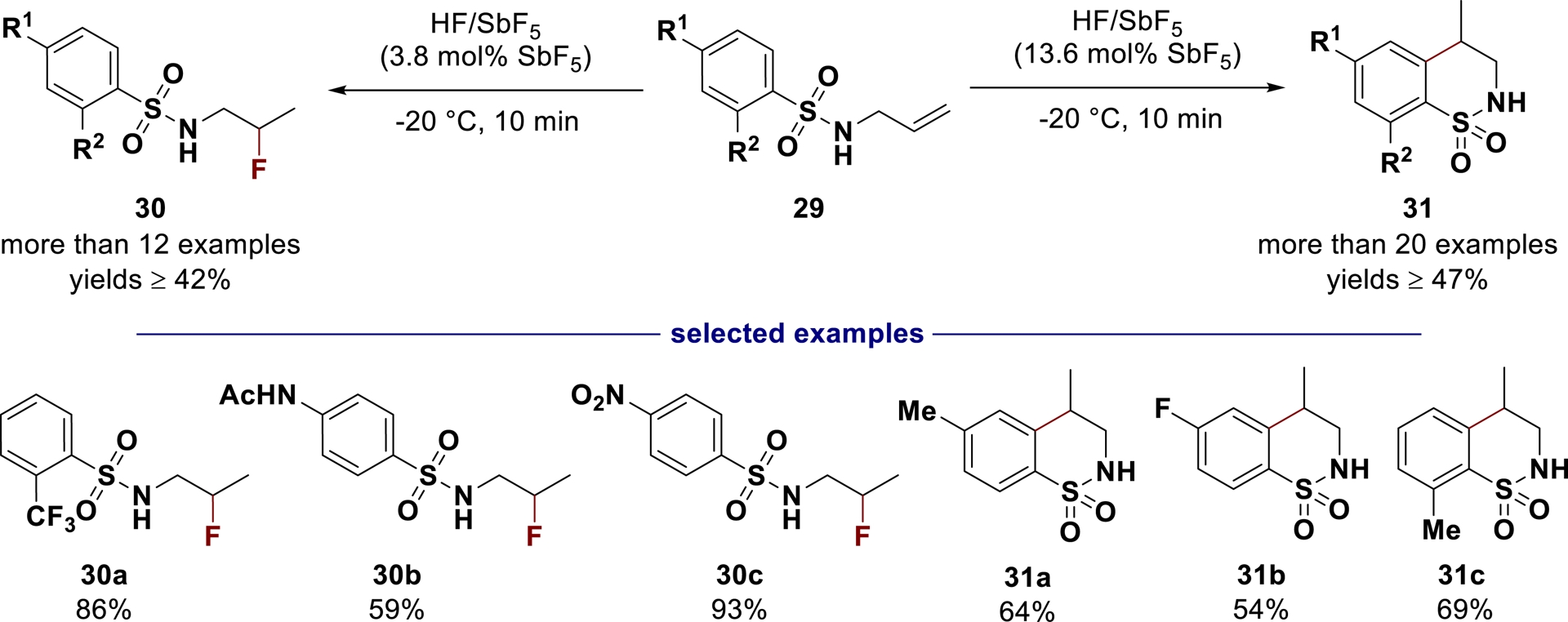

Exploiting the stability of fluorinated products (obtained from hydrofluorination reactions) in HF/SbF5 (SbF5 loading ⩽ 10 mol%), and the ability to activate C–F bonds at higher acidity with a concomitant decrease in the nucleophilicity of the fluoride ions, fluorinated sulfonamides 30 and benzofused sultams 31 can be selectively synthetized from N-allyl-benzenesulfonamides 29 (Scheme 21) [100]. With this method, a large variety of products 30 and 31 incorporating alkyl, halogen, amide, ester, ketone, and other functions were generated in good yields.

Selective hydrofluorination and cyclization of N-allyl-benzenesulfonamides in HF/SbF5 (adapted/redrawn from [1]).

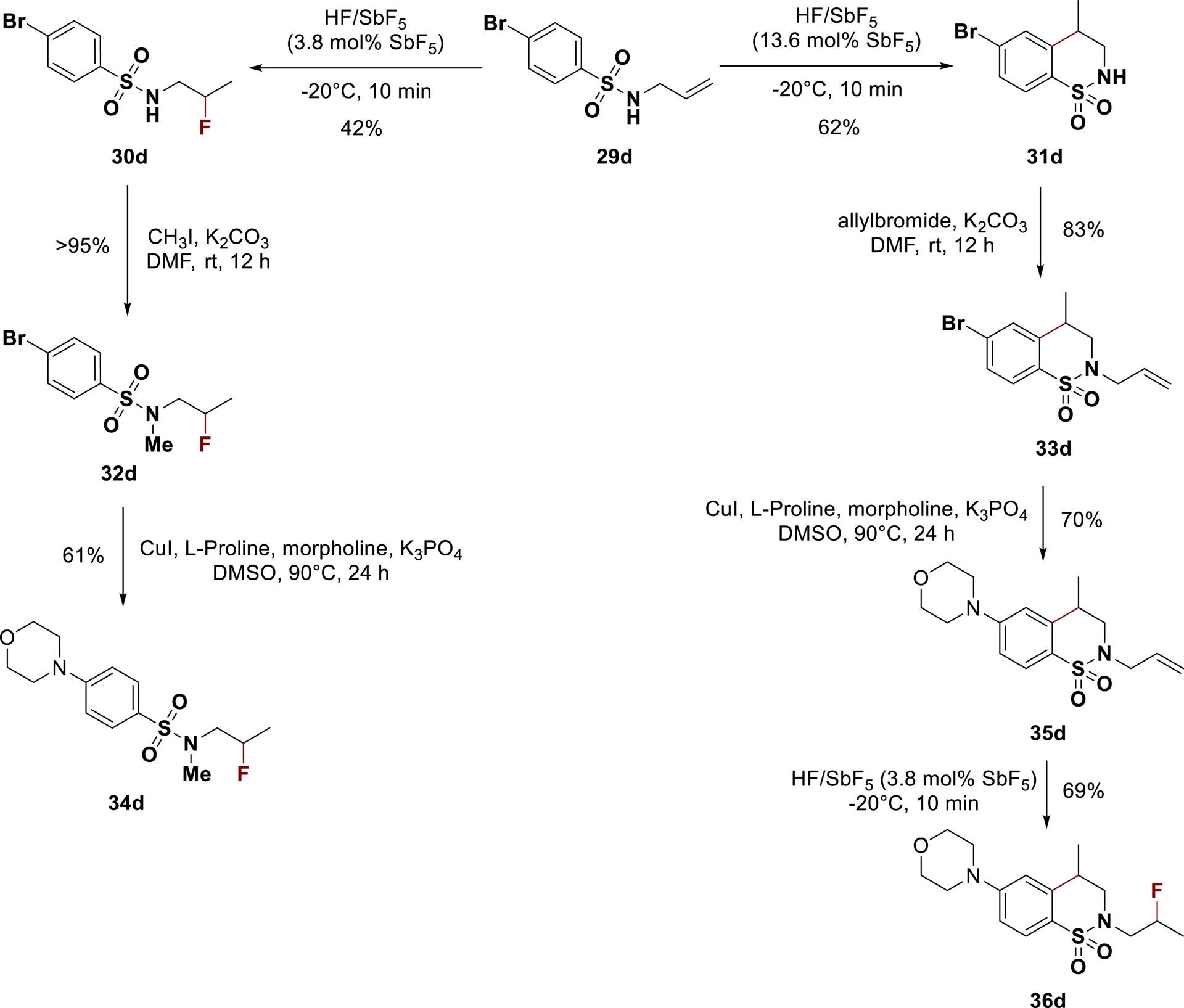

Given that amino-benzenesulfonamide derivatives and their cyclic analogues are interesting targets for various therapeutic applications (inhibition of matrix metalloprotease [101], carbonic anhydrases [94, 95, 102] or HIV protease [103, 104] for instance), the method described above was next applied to their synthesis. A complete set of fluorinated 4-aminobenzofused sultams and fluorinated 4-aminobenzenesulfonamides could be produced from halogen-substituted derivatives using a combination of superacid-mediated cyclization/hydrofluorination and Ulmann-type coupling with amines [105]. For instance, starting from brominated N-allyl-benzenesulfonamide 29d, fluorinated 4-morpholino-benzenesulfonamide 34d and fluorinated 4-morpholino-benzofused sultam 36d were synthesized in overall good yields, confirming the synthetic potential of this method (Scheme 22).

Superacid/copper-mediated multistep divergent synthesis of 4-aminobenzenesulfonamides (adapted/redrawn from [1]).

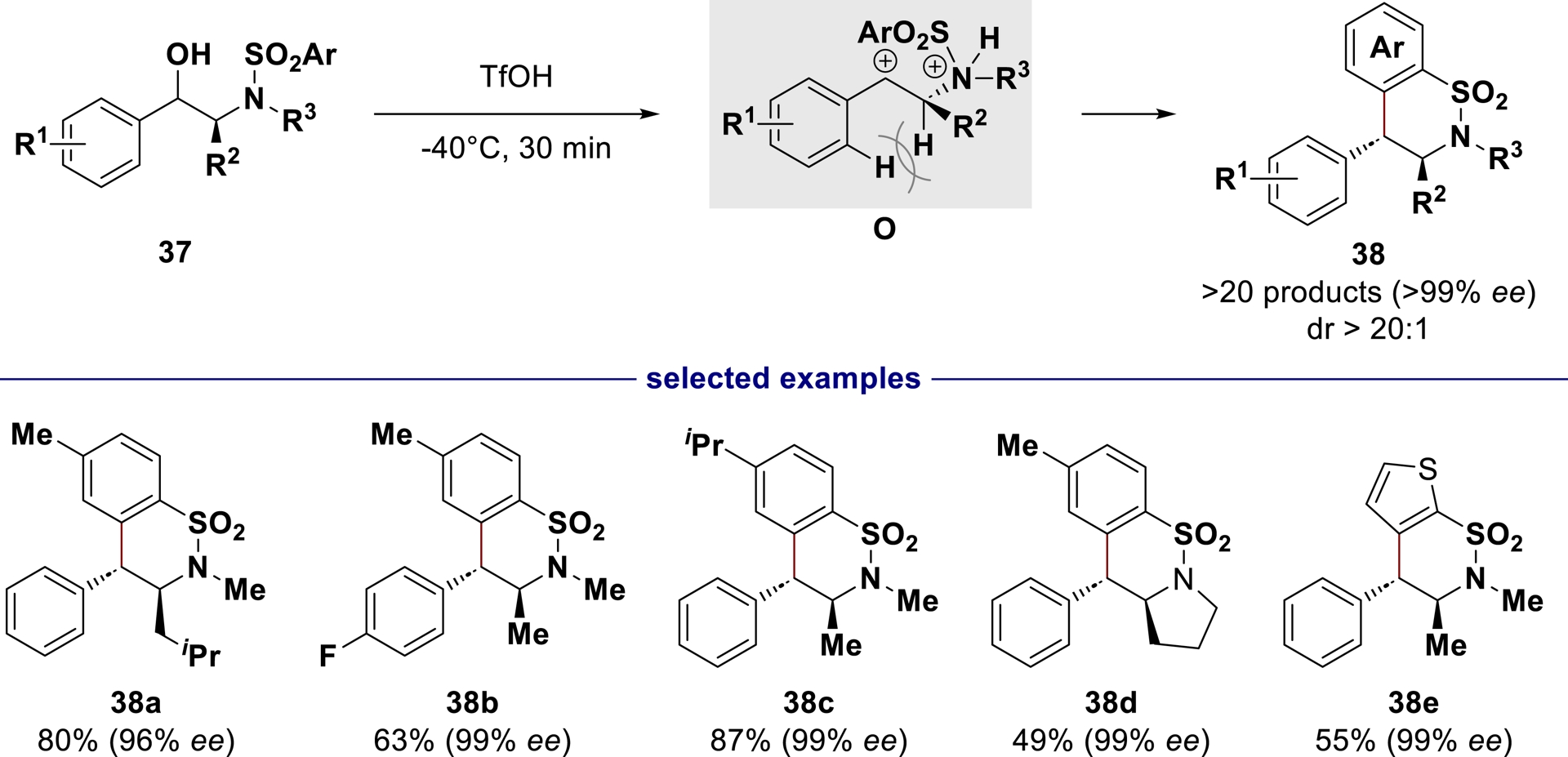

Using the stability of benzylic carbocations and their restricted conformation due to benzylic strain [106, 107], we hypothesized that starting from simple N-(arenesulfonyl)-ephedrine derivatives 37, dicationic intermediate O could be generated under superacidic conditions. It would react diastereoselectively, to afford enantiopure benzosultams 38 [108]. Taking advantage of the chiral pool, a number of optically active N-(arenesulfonyl)-amino alcohols were successfully transformed in triflic acid into enantiopure benzosultams with a diverse range of functionalities and substitution patterns (Scheme 23).

Superacid-mediated synthesis of enantioenriched benzosultams.

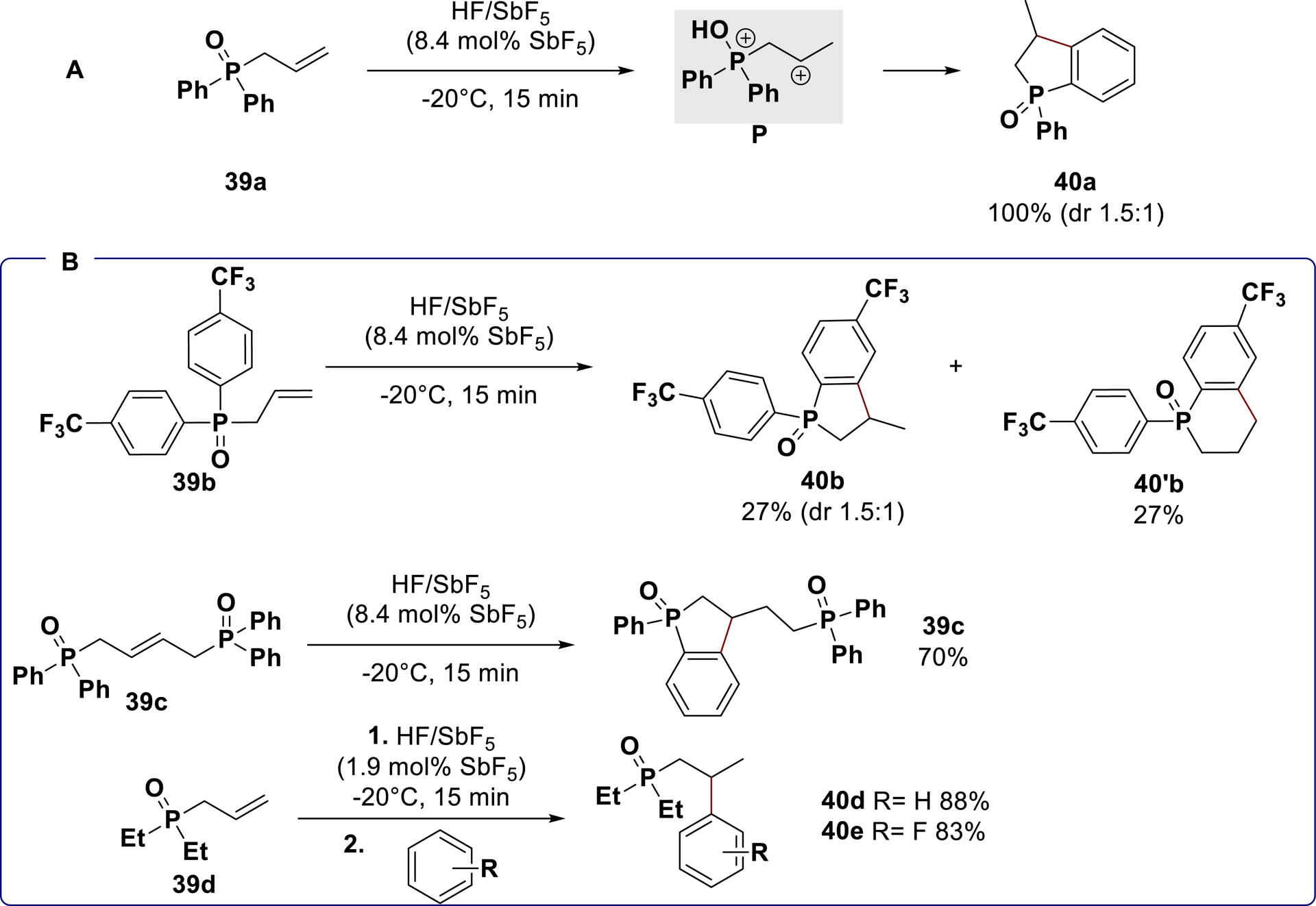

Pursuing our efforts to develop hydrofunctionalization methods, we also turned our attention to organophosphorus derivatives which have found wide application in various fields such as catalysis, medicinal chemistry, and material science [109, 110, 111, 112, 113]. Starting from arylated phosphine oxide derivatives 39a in HF/SbF5 superacid conditions, the cyclized phosphinindoline 40a was generated in a 2/3 mixture of syn/anti diastereomers (Scheme 24A) [114]. The same substrate submitted to anhydrous HF (H0 ≈ −11) or CF3SO3H (H0 = −14) remained unreactive at −20 °C. These results confirmed that activation of the substrate is strongly dependent on the (super)acidity of the medium, a result that is consistent with a superelectrophilic activation process. This hypothesis was further confirmed by in-situ low-temperature NMR experiments and single-crystal X-ray diffraction studies showing evidences for the formation of phosphonium–carbenium dications in HF/SbF5. The superelectrophilic character of these species was exploited in intra- and intermolecular hydroarylation reactions (Scheme 24B).

Reactivity of phosphonium–carbenium superelectrophiles toward hydroarylation reaction.

5. Cyclization/fluorination of unsaturated N-containing derivatives

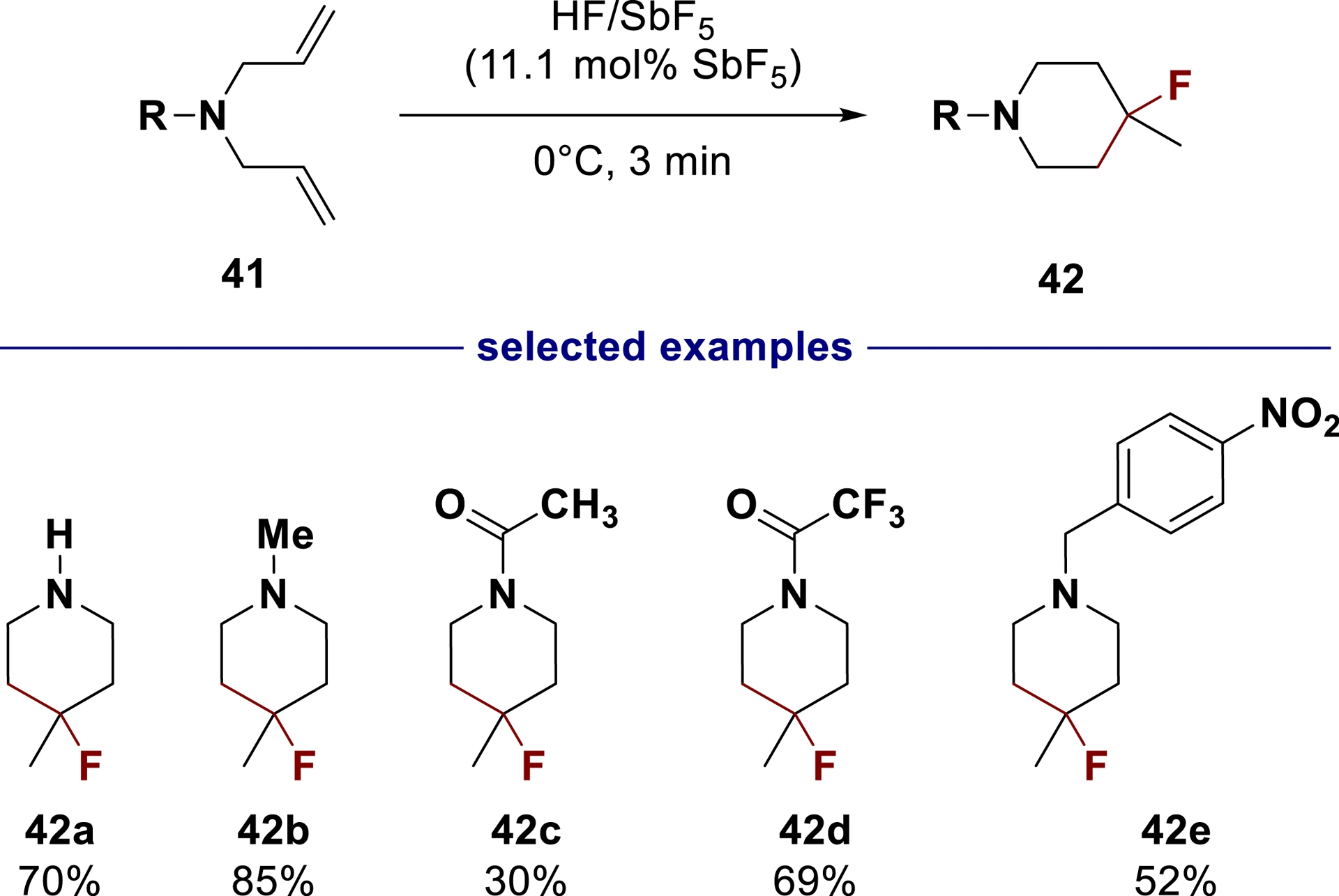

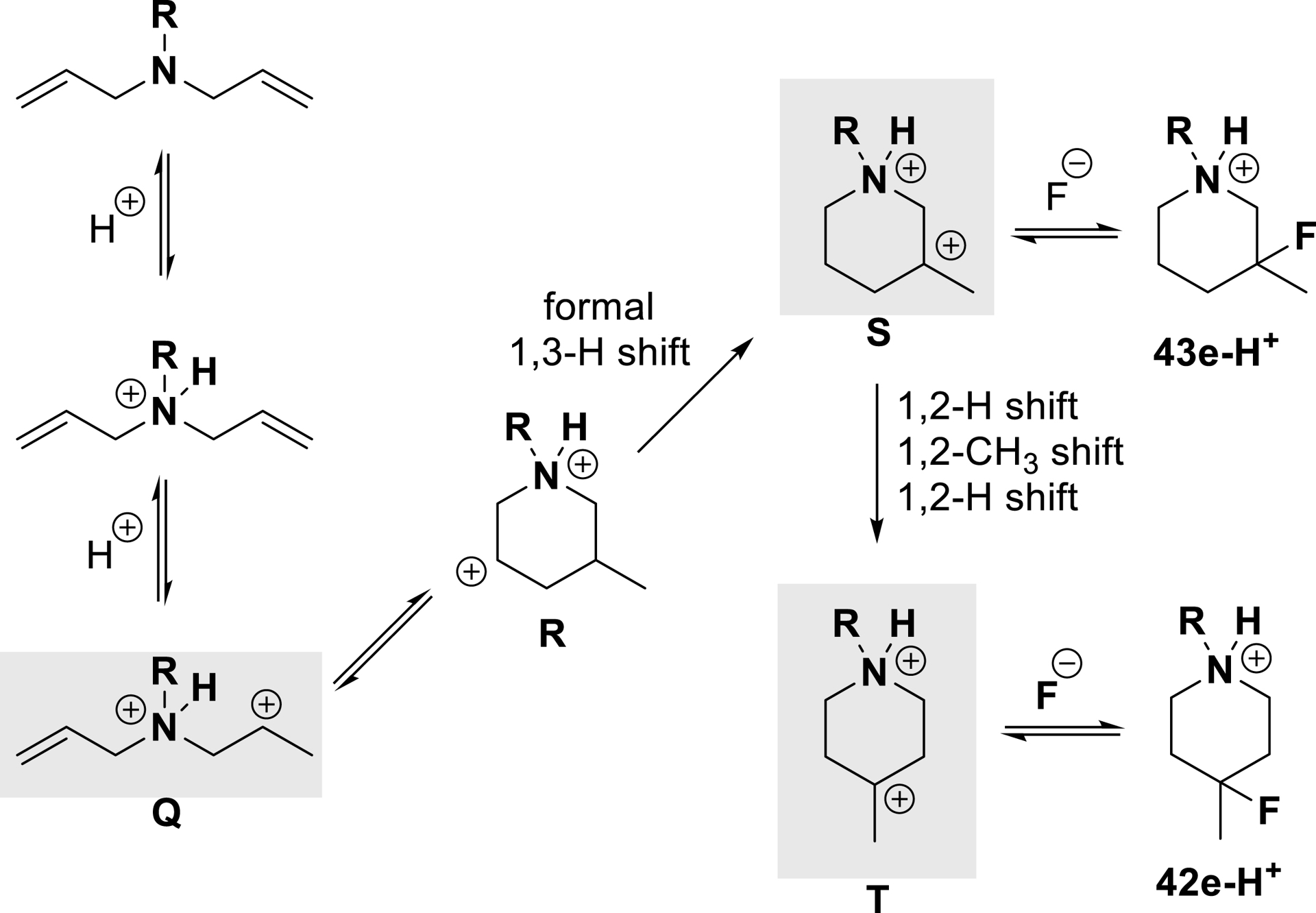

As demonstrated in the synthesis of benzofused sultams, the superelectrophilic nature of ammonium–carbenium dications enables intramolecular trapping with poor nucleophiles. This reactivity was further expanded by utilizing a C=C double bond as a nucleophile. The cyclization/fluorination of differently substituted dienes 41 was found to be a versatile technique to obtain fluorinated piperidines 42 (Scheme 25) [115].

Cyclization/fluorination of N-dienes in superacid HF/SbF5 (adapted/redrawn from [1]).

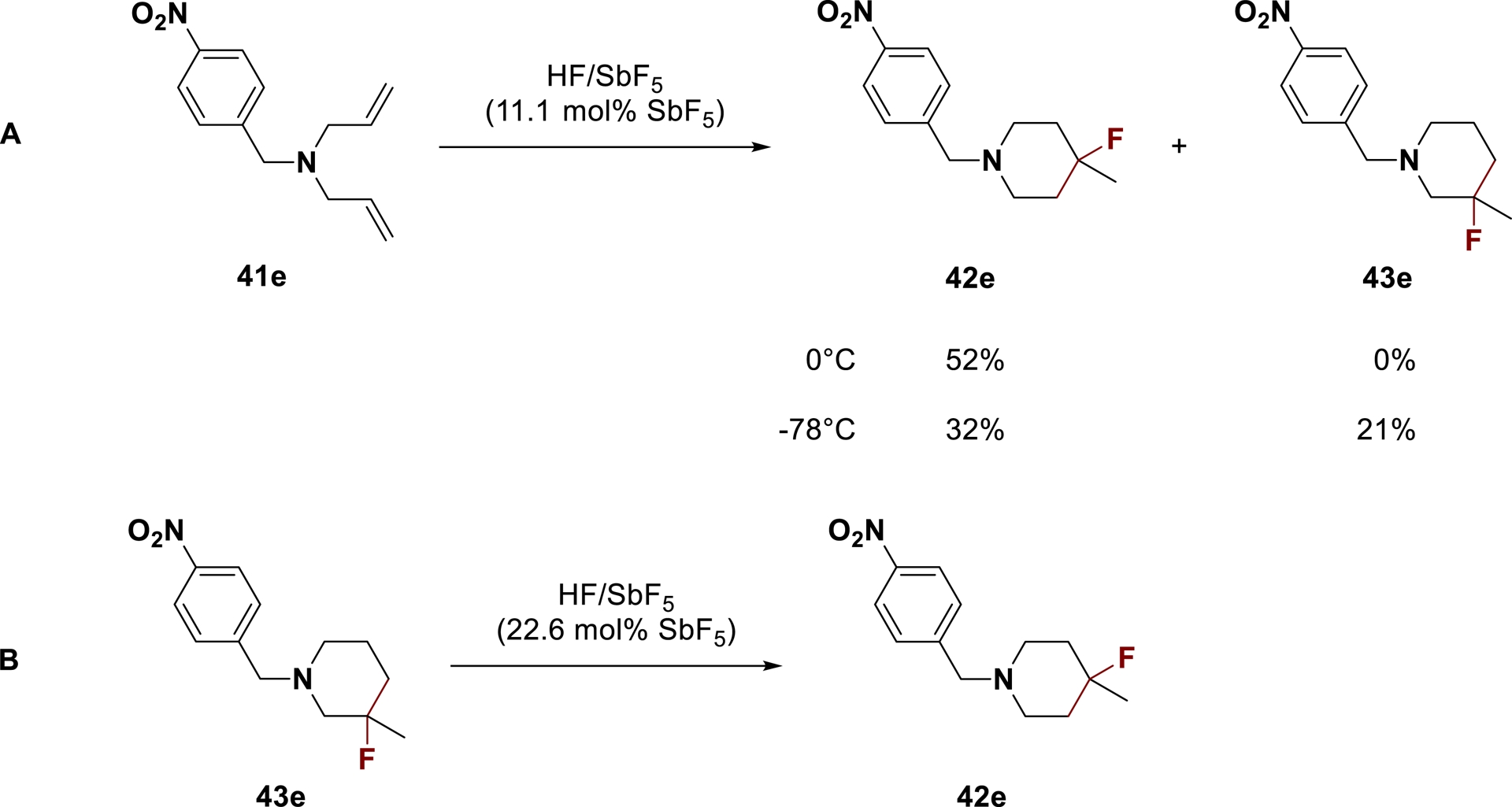

Low-temperature experiments were carried out to investigate the reaction mechanism. After reaction of amine 42e in HF/SbF5 (11.1 mol% SbF5) at −78 °C, 21% of 3-fluoropiperidine 43e was generated beside 4-fluoro analog 42e (Scheme 26A). Furthermore, substrate 41e was shown to transform only into 42e after reaction at 0 °C. Thus, milder conditions were required to selectively generate the 3-fluoropiperidine, which indicated that this isomer might be an intermediate of the reaction. The quantitative formation of compound 42e starting from 3-fluoropiperidine 43e validated this hypothesis (Scheme 26B), which allowed to postulate the following mechanism (Scheme 27).

(A) Formation of 3- and 4-fluoropiperidines in HF/SbF5; (B) Formation of 4-fluoropiperidine 41e from 3-fluoropiperidine 42e in HF/SbF5 (adapted/redrawn from [1]).

Proposed mechanism for the cyclization/fluorination reaction of diallylamines (adapted/redrawn from [1]).

After nitrogen protonation, the superacidity of the medium allows formation of ammonium–carbenium dication Q. Proximity of the charges greatly activates its electrophilic character, permitting nucleophilic addition of the non-protonated alkene (despite electronic deactivation due to the strong withdrawing influence of the proximal ammonium ion), resulting in intermediate R. A sequence of hydride and methyl shifts favors the formation of the more stable dication T through the generation of intermediate S, both respective precursors of 42 and 43 after fluoride ion trapping.

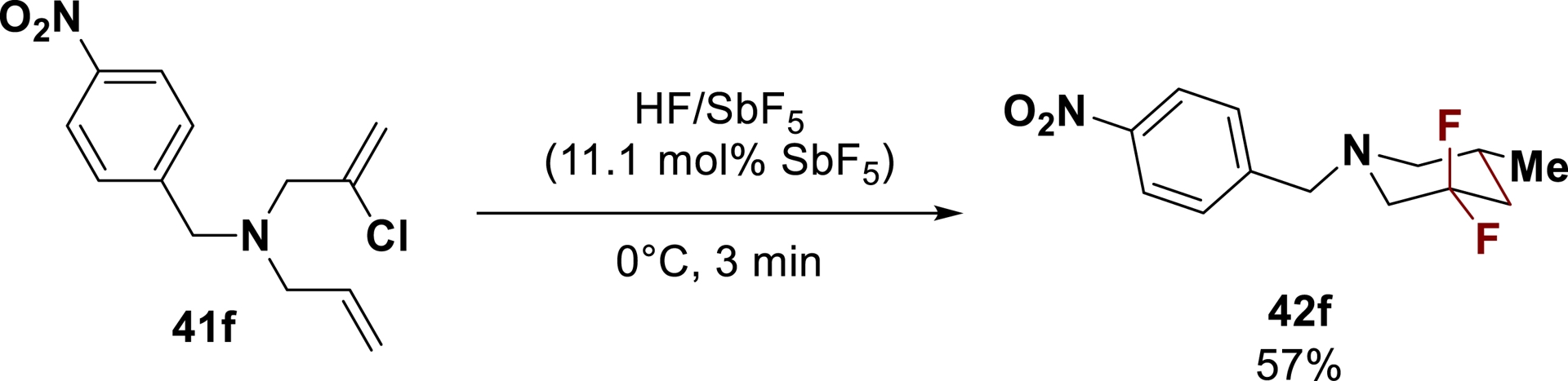

Using superelectrophilic ammonium–α-chlorocarbenium dications allowed the direct preparation of difluorinated piperidines by cyclization and fluorination. Starting from chlorinated N-diene 41f, the difluorinated piperidine 42f was directly synthesized in 57% yield (Scheme 28) [116].

Direct synthesis of a difluorinated piperidine through cyclization/fluorination reaction (adapted/redrawn from [1]).

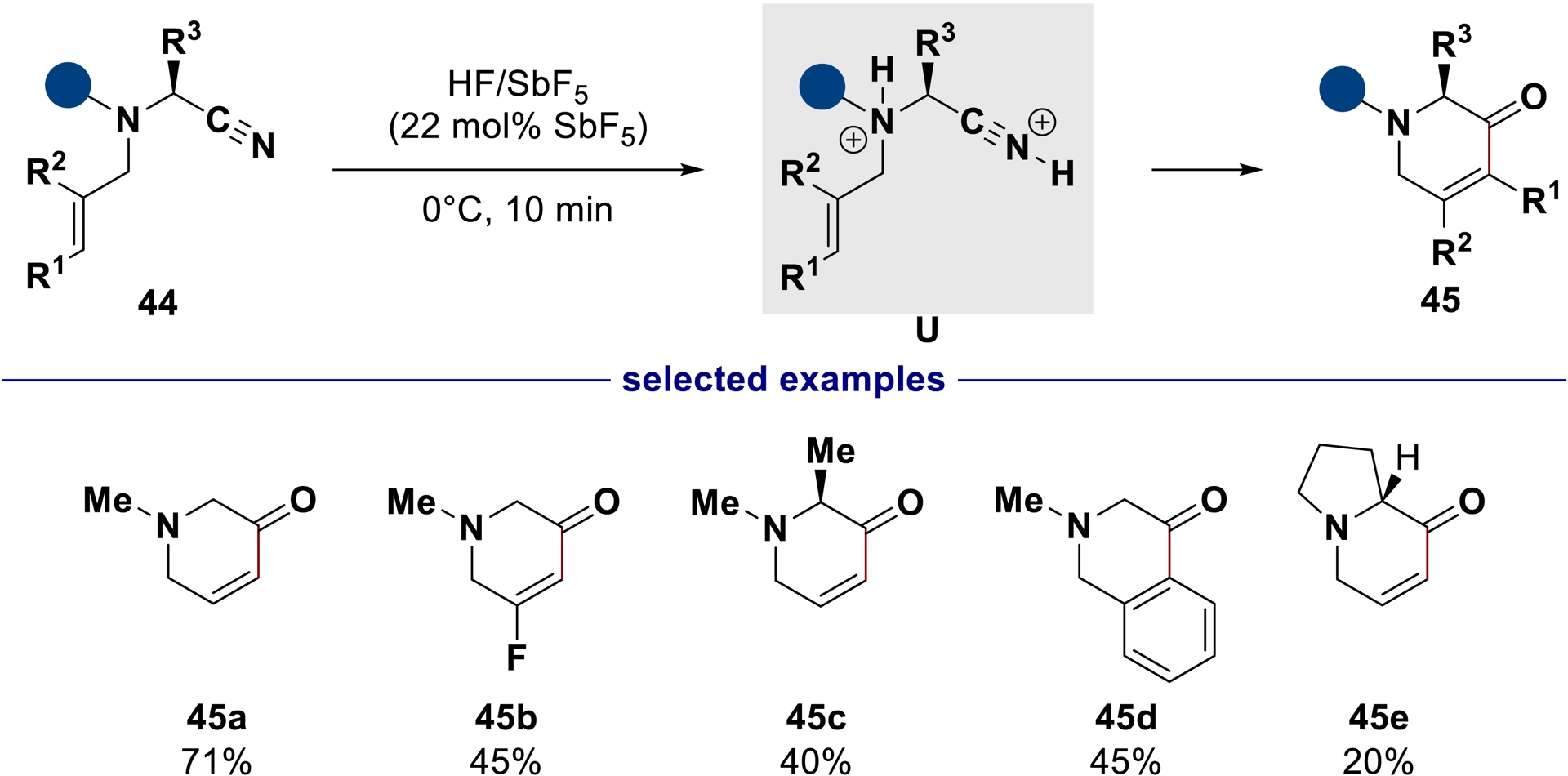

Alternatively, using ammonium–nitrilium dications as superelectrophiles, unsaturated piperidinones can also be synthesized exploiting the alkene moiety as internal nucleophile [47]. These ammonium–nitrilium dications U have been observed and characterized by single-crystal X-ray diffraction analysis and low-temperature NMR experiments in superacid media. Taking advantage of their superelectrophilic character, their intramolecular trapping with poorly nucleophilic alkenes allows straightforward access to high-valued (enantioenriched) piperidin-3-ones 45 (Scheme 29).

Exploitation of ammonium–nitrilium dications’ reactivity in HF/SbF5 for the synthesis of piperidinones.

6. Miscellaneous applications

6.1. Late-stage functionalization

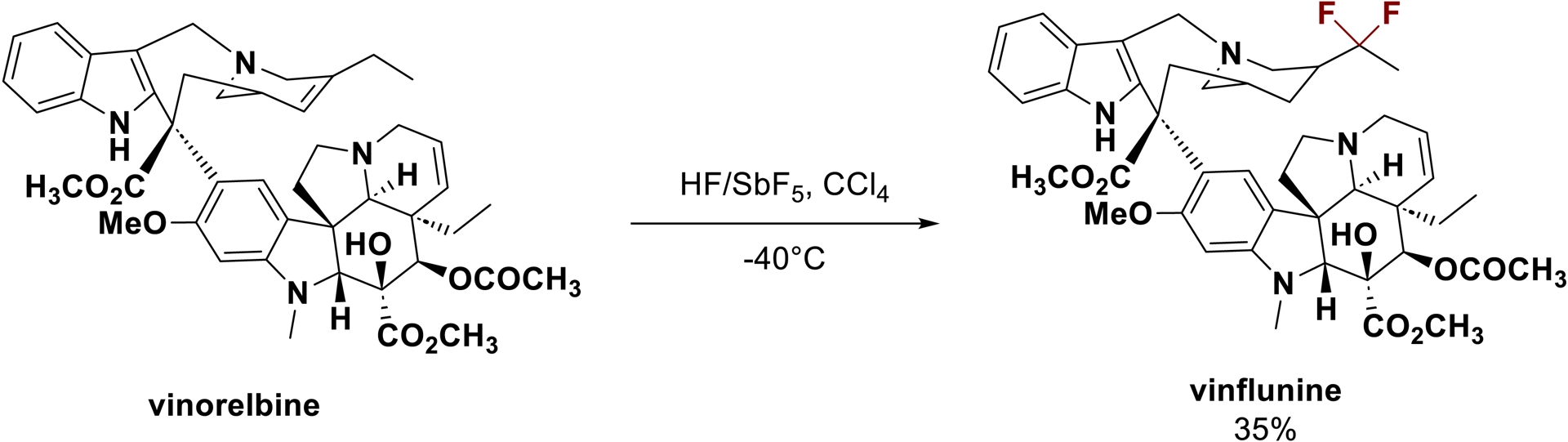

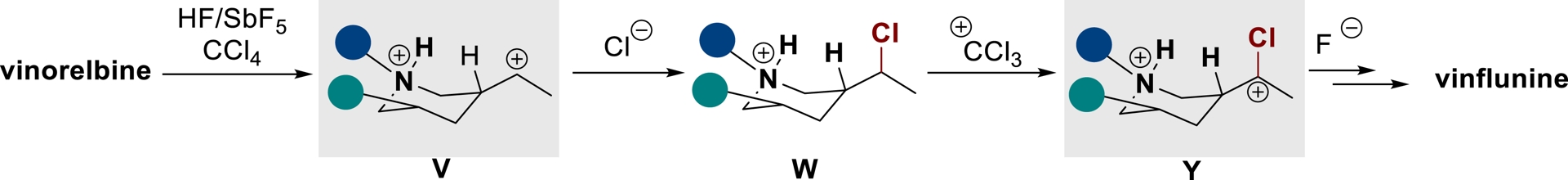

The development of new synthetic methods is essential for the discovery of efficient and selective pharmaceuticals [117]. Jacquesy et al. have shown that activation in superacid medium is a suitable synthetic tool in this perspective, allowing the modification of simple to highly complex molecules and thereby giving access to new analogs [118, 119]. The most notable example is the direct synthesis of vinflunine from a Vinca alkaloid through a direct modification in a HF/SbF5 solution (Scheme 30) [120, 121, 122]. To the best of our knowledge, despite extensive efforts, this anti-cancer agent [123], commercialized under the brand name Javlor®, cannot be synthesized by other synthetic methods [124].

Synthesis of vinflunine in HF/SbF5/CCl4 (adapted/redrawn from [1]).

The vinorelbine starting material reacts with HF/SbF5 to form a superelectrophilic ammonium–carbenium dication V which can be chlorinated in the presence of CCl4 to generate intermediate W along with chlorocarbocation $\mathrm{CCl}_{3}^{+}$. The latter can act as a hydride-abstracting agent (as shown above on some standard building blocks) [48], allowing the ionic electrophilic activation of the C–H bond which leads to superelectrophile Y. Its subsequent fluorination and halogen exchange allow delivering vinflunine (Scheme 31). A similar strategy has also been applied to diverse Cinchona alkaloids [125, 126].

Superelectrophilic activation of Vinca alkaloids in superacid (adapted/redrawn from [1]).

6.2. Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors

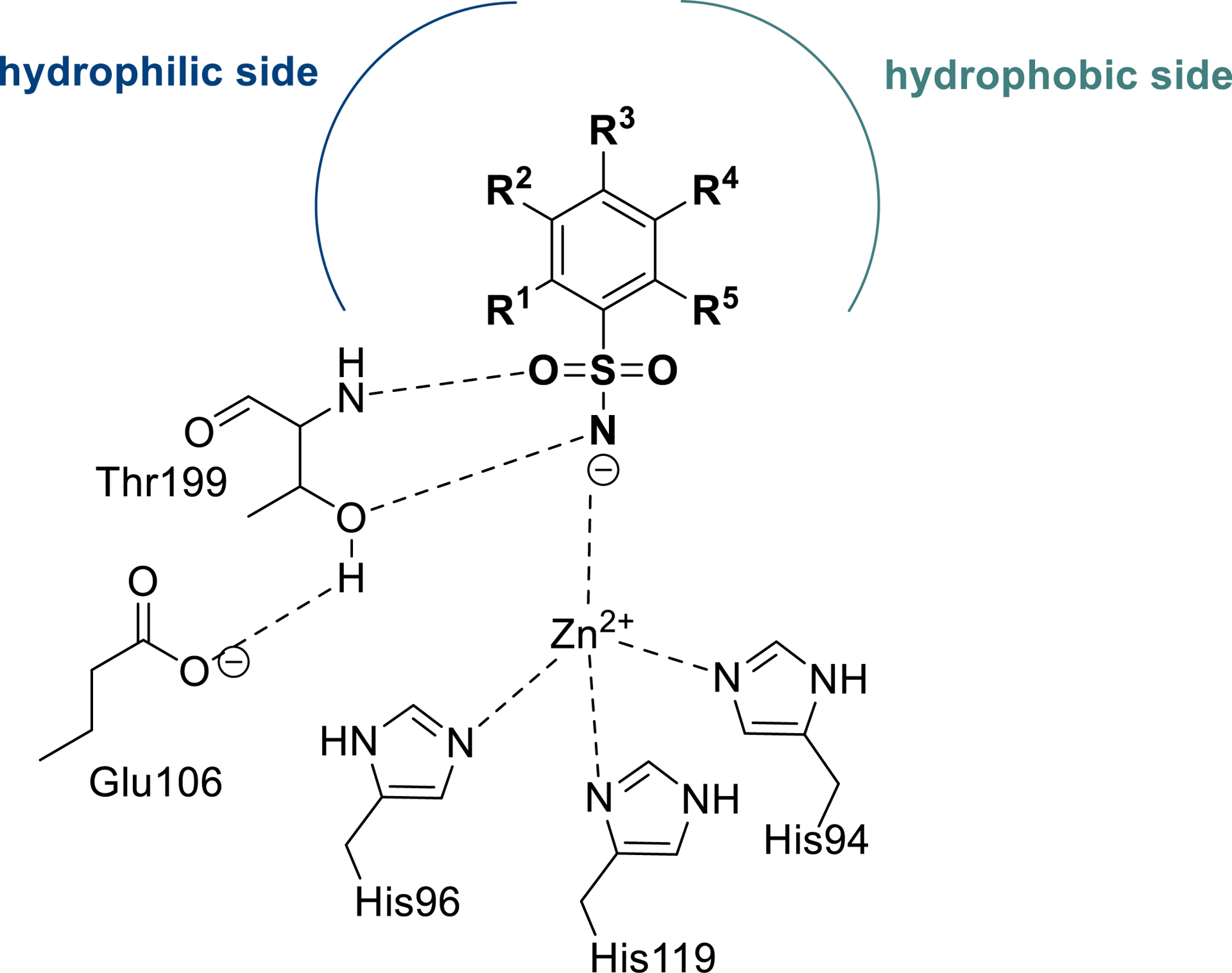

Carbonic anhydrases (CAs, EC 4.2.1.1) are widespread metalloenzymes that participate in a variety of metabolic processes involving the hydration/dehydration of carbon dioxide/bicarbonate [127, 128, 129]. Human CAs (hCAs) present 16 isoforms, which belong to the α-class. They differ in cellular location (cytosol, mitochondria, and cell membrane) and catalytic activity [94, 95, 96]. They are involved in numerous cellular and physiological activities, including respiration, electrolyte secretion, pH homoeostasis, and biosynthetic reactions that require bicarbonate as substrate including lipogenesis, glucogenesis, and ureagenesis, as well as tumorigenicity among others [95]. As a consequence, CAs are well-established therapeutic targets for treating a variety of diseases using inhibitors or activators [102, 130, 131]. Classical CA inhibitors (CAIs) disrupt the catalytic process by complexing (as anions) the zinc ion from the enzyme’s active site [95]. Among the numerous families of CAIs, primary sulfonamides are one of the most exploited, mainly due to the multiple interactions that such compounds can establish with the hydrophobic and hydrophilic half parts of the isoforms (Figure 1) [132, 133, 134].

Binding of primary sulfonamide inhibitors to carbonic anhydrase. Key interactions between a generic benzenesulfonamide and the hCA II active site (adapted/redrawn from [1]).

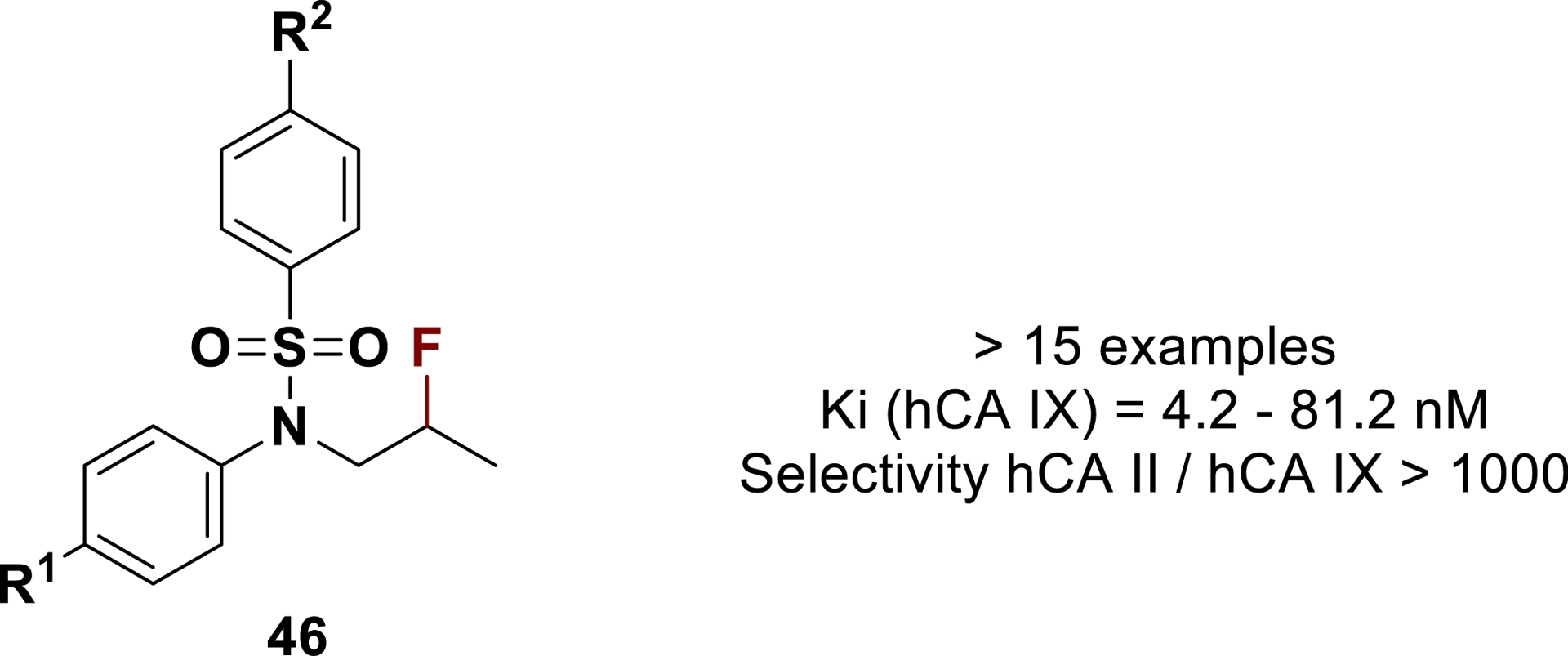

The design of highly selective CAIs is a favored strategy to prevent undesired side effects [135, 136]. In this context, the so-called family of “non-zinc binding inhibitors” have deeply increased over the last few years [137, 138, 139], especially in the quest of potent and selective anti-cancer agents (targeting the cancer-associated isoforms hCA IX and XII) [140, 141, 142, 143, 144]. On the other hand, various studies have been conducted on the impact of fluorine insertion on benzenesulfonamides inhibitors showing that inserting fluorine atoms can improve specific interactions that can strengthen the inhibition by the fluorinated benzenesulfonamides compared to the non-fluorinated ones [145].

Our recent investigations on the synthesis of fluorinated compounds in superacid led to the identification of a series of fluorinated tertiary benzenesulfonamides 46 acting as selective hCA IX inhibitors (Figure 2) [146, 147]. Almost all of the proposed compounds in this fluorinated series were shown to be highly selective tumor-associated CAIs that did not inhibit the widespread off-target isoform hCA II, showing a new mode of inhibition of tumor-associated CAs by sulfonamides.

Fluorinated tertiary benzenesulfonamides acting as selective hCA IX nanomolar inhibitors (adapted/redrawn from [1]).

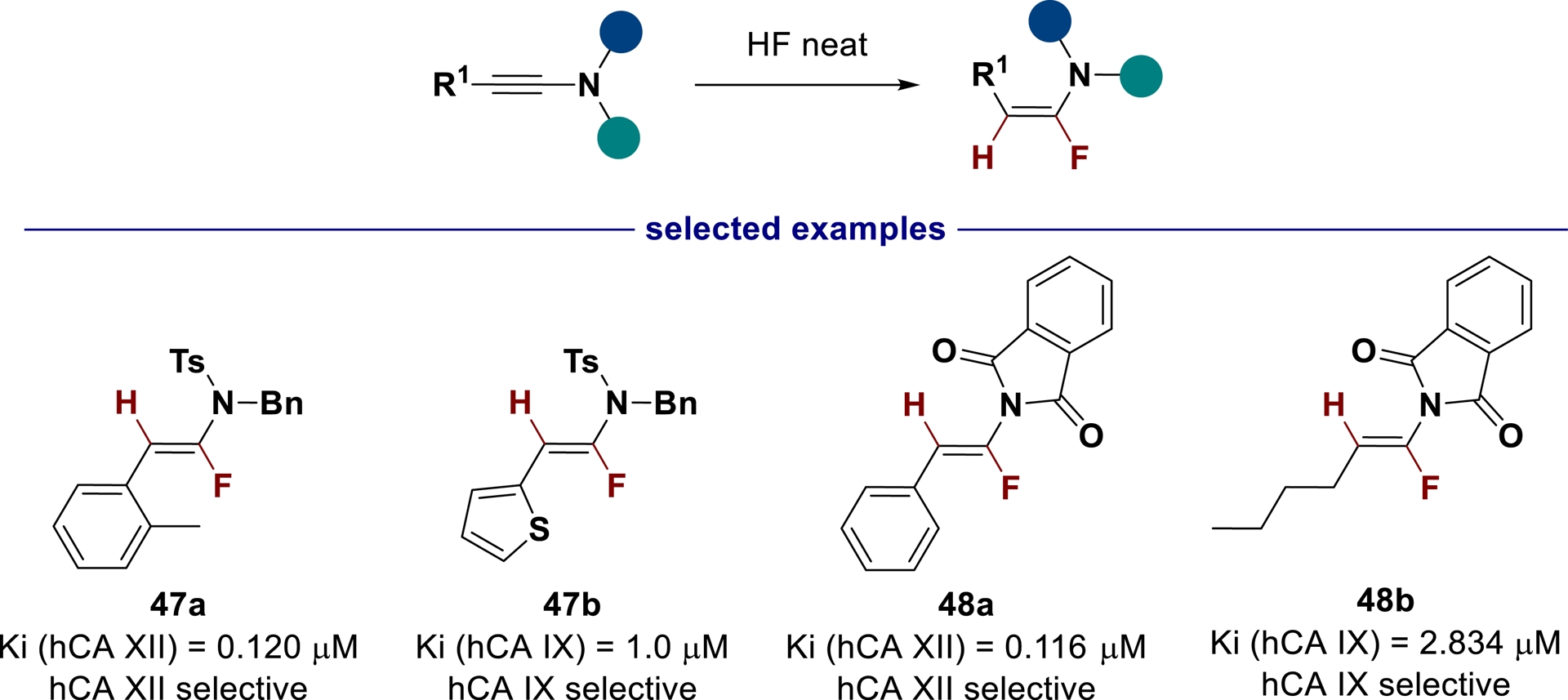

Recently, urea derivatives, and especially sulfonylurea analogs, were found to be good inhibitors of hCA IX/XII [148, 149, 150]. Exploiting our method to design new fluoroenesulfonamides as N-sulfonylurea isosters [87], these compounds, which are stable in solution, were evaluated as CA inhibitors (Scheme 32) [151]. This study identified a novel, highly selective family of cancer-related transmembrane CAIs. The studied α-fluoroenamide ureidoisosters did not inhibit broadly distributed cytosolic isoforms hCA I and II, but preferentially inhibited transmembrane cancer-related isoforms hCA IX and XII. Modifying the C-substituent of α-fluoroenesulfonamide 47 and α-fluoroenimide 48 resulted in selective hCA IX, selective hCA XII, or dual hCA IX and hCA XII isoforms, demonstrating the potential of these novel pharmacophores.

6.3. Carbohydrate chemistry

Considering the weakly coordinating nature of the anions in superacid media, as well as the ability to generate and stabilize cationic species in HF/SbF5 solutions, we recently contributed to the investigation of the glycosylation mechanism in partnership with the Blériot and Barbero groups. It is accepted that glycosyl oxocarbenium intermediates play a key role in the stereochemical outcomes of glycosylation reactions. Yet, their direct experimental observation remained elusive owing to their very short lifetime in solution. Using superacidic (non-nucleophilic) conditions, their analysis by NMR, combined with computational methods, becomes possible. Thus, we have reported the use of superacid HF/SbF5 solution to generate and stabilize the glycosyl cations derived from peracetylated 2-deoxy- and 2-bromoglucopyranose [152].

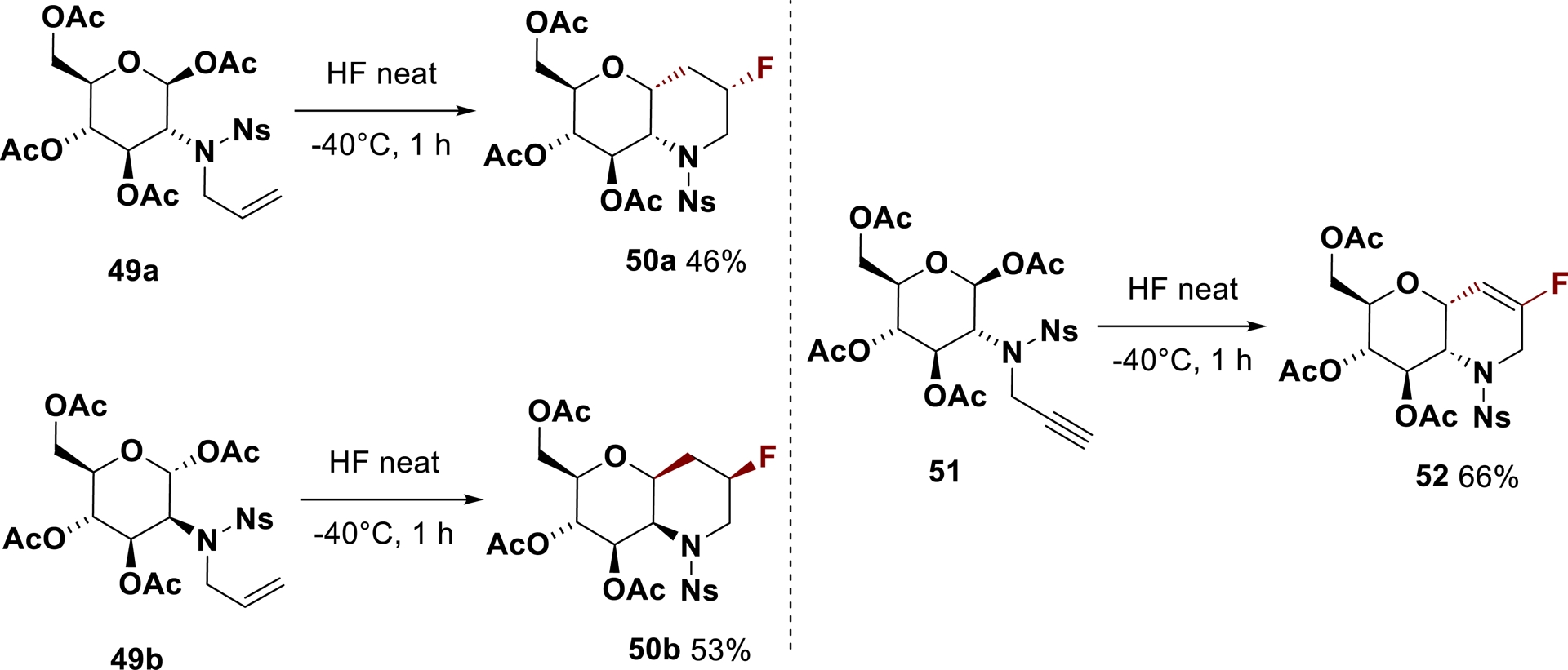

The generation of glycosyl cations from carbohydrates in superacid was then used for synthetic purposes in the 2-aminoglycoside series resulting in unprecedented sugar–azacycle hybrids. A tandem internal C-glycosylation/fluorination reaction initiated by 2-N-allyl- and 2-N-propargyl-glycopyranoses through the intermediacy of ammonium–carbenium superelectrophiles afforded new fluorinated compounds (Scheme 33) [153]. The reaction of N-allyl-D-gluco- 49a and D-mannopyranose 49b provided the corresponding monofluorinated bicycles 50a (46%) and 50b (53%) with a 1,2-cis relationship. Fluoride anion trapping of the transitory cyclic cation led diastereoselectively to the formation of a C–F bond in β-position to the nitrogen atom. A similar process involving alkyne derivative 51 enabled direct synthesis of analog 52 incorporating a vinyl fluoride moiety. These sugar-based polycyclic compounds with a central piperidine ring, amenable to further structural modification, are of interest in a medicinal chemistry context [154], owing to the therapeutic potential offered by both fluorine-containing molecules and sugar derivatives.

Direct synthesis of fluorinated sugar–azacycle hybrids in neat HF.

The replacement by a nitrogen atom of the endocyclic oxygen in monosaccharides results in iminosugars, a class of sugar mimics with strong therapeutic potential [155]. Its most famous representative, 1-deoxynojirimycin (DNJ), is a natural product [156] that exhibits potent α- and β-glucosidases inhibition. The alkylation of the endocyclic nitrogen with various alkyl chains led to two approved medicines Zavesca® and Miglitol® which target Gaucher’s disease [157] and type II diabetes [158], respectively (Figure 3).

Structure of 1-deoxynojirimycin (DNJ) and representative derivatives.

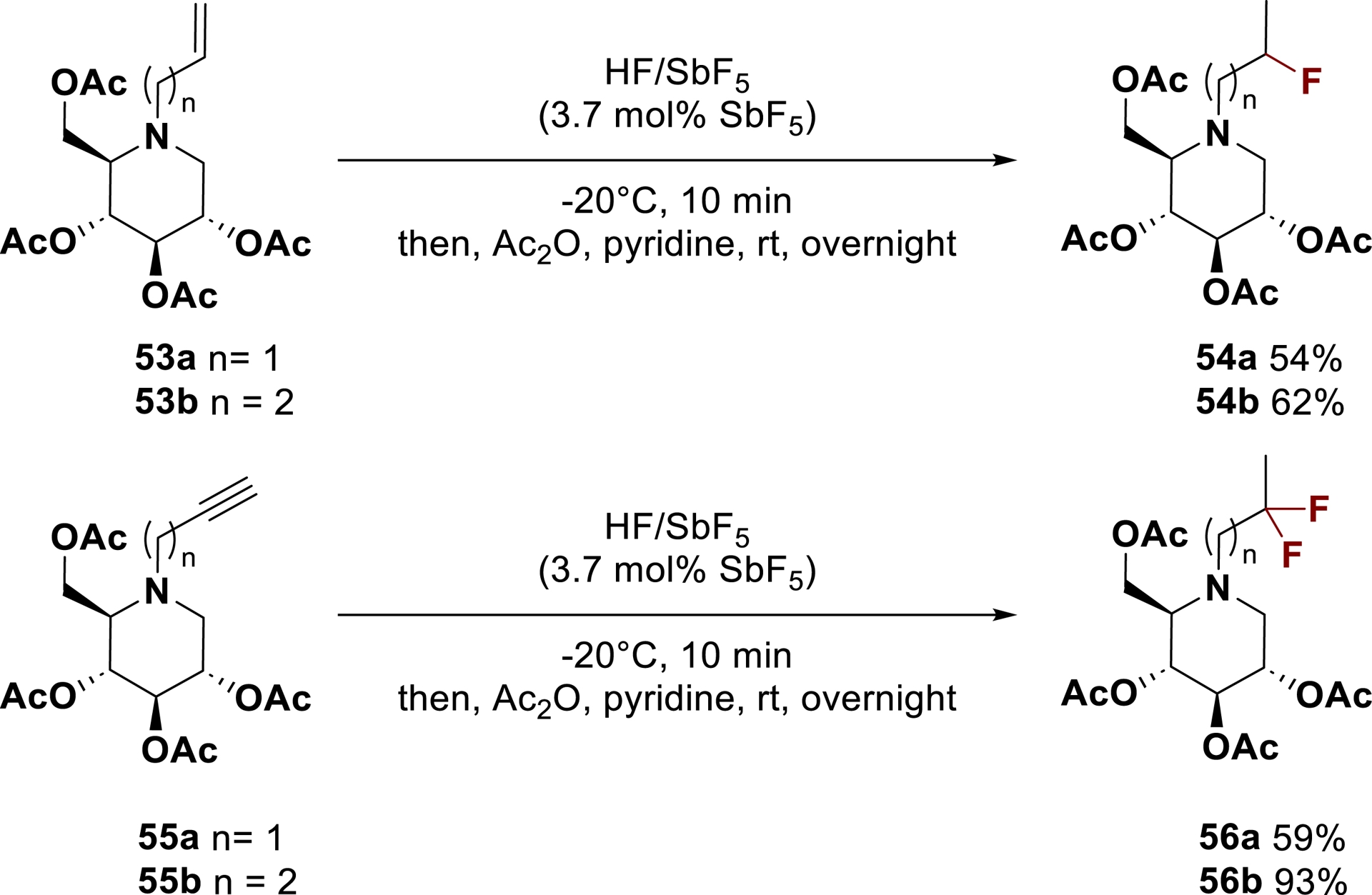

In this context, the introduction of a fluorinated chain on the iminosugar moiety through superacid activation was explored. A small series of fluorinated DNJ derivatives 54 and 56 were successfully synthetized from N-allyl and N-propargyl iminosugars 53 and 55 with good yields, showing the potential of this strategy to generate potentially interesting pharmacophores in this context (Scheme 34) [159].

7. Conclusion

Elegantly exploited by Olah and others for studying long-lived carbocations, superacids can be considered as especially unique media to transform organic molecules. In the design of nitrogen-containing fluorinated bioactive compounds, we recently demonstrated that superacid media (e.g., HF-based media) allow original hydrofunctionalization of N-containing alkenes and alkynes and can be applied to the late-stage functionalization of elaborate molecules ranging from natural products to active pharmaceutical ingredients. The ability to use superelectrophilic activation for C–H bond fluorination or for carbohydrate activation also let us envisage original applications of this chemistry in a near future.

Declaration of interests

The authors do not work for, advise, own shares in, or receive funds from any organization that could benefit from this article, and have declared no affiliations other than their research organizations.

CC-BY 4.0

CC-BY 4.0