This account is dedicated to my mentor, Dr. Jean-Luc Parrain, whose intellectual integrity and scientific rigor have been a source of inspiration throughout my career.

1. Introduction

Donor–acceptor cyclopropanes (DACs) are highly versatile reactive intermediates in organic synthesis, thanks to their unique combination of electronic polarization and ring strain (for seminal reports on DACs, see [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]). These molecules feature electron-donating and electron-withdrawing groups on adjacent carbon atoms, creating a pronounced push–pull effect that facilitates selective bond cleavage and rearrangements. At the same time, the significant strain inherent to the cyclopropane ring (∼27.5 kcal/mol) contributes a powerful driving force for a variety of transformations. It is precisely the synergy between these two features, electronic polarization and ring strain, that underpins the distinctive reactivity of DACs (for kinetic studies on the reactivity of DACs, see [6]). Consequently, they have emerged as valuable synthetic building blocks for constructing complex carbocyclic and heterocyclic frameworks, enabling access to diverse molecular architectures with high efficiency and selectivity (for selected reviews on DACs chemistry, see [7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29]; for an example on total synthesis, see [30]).

While numerous DAC-mediated transformations have been developed, the influence of the reaction environment on their reactivity remains an area of investigation. DAC activation can occur through thermal, catalytic, or photochemical methods, each offering distinct benefits and presenting specific challenges (for different modes of activation of DACs, see [31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43]).

In solution-phase reactions, factors such as solvent polarity, thermal input, and catalytic systems play a central role in governing reactivity and selectivity. In contrast, crystal-state transformations (for seminal reports on topochemical polymerization, see [44, 45, 46, 47]; for examples of topochemical polymerization, see for instance [48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54]) introduce unique considerations, including crystal-packing effects, molecular orientation, and topochemical restrictions, which can profoundly influence reaction pathways [55, 56, 57]. A deeper understanding of how these environmental variables impact selectivity and product distribution is essential to fully harness the synthetic potential of DAC chemistry.

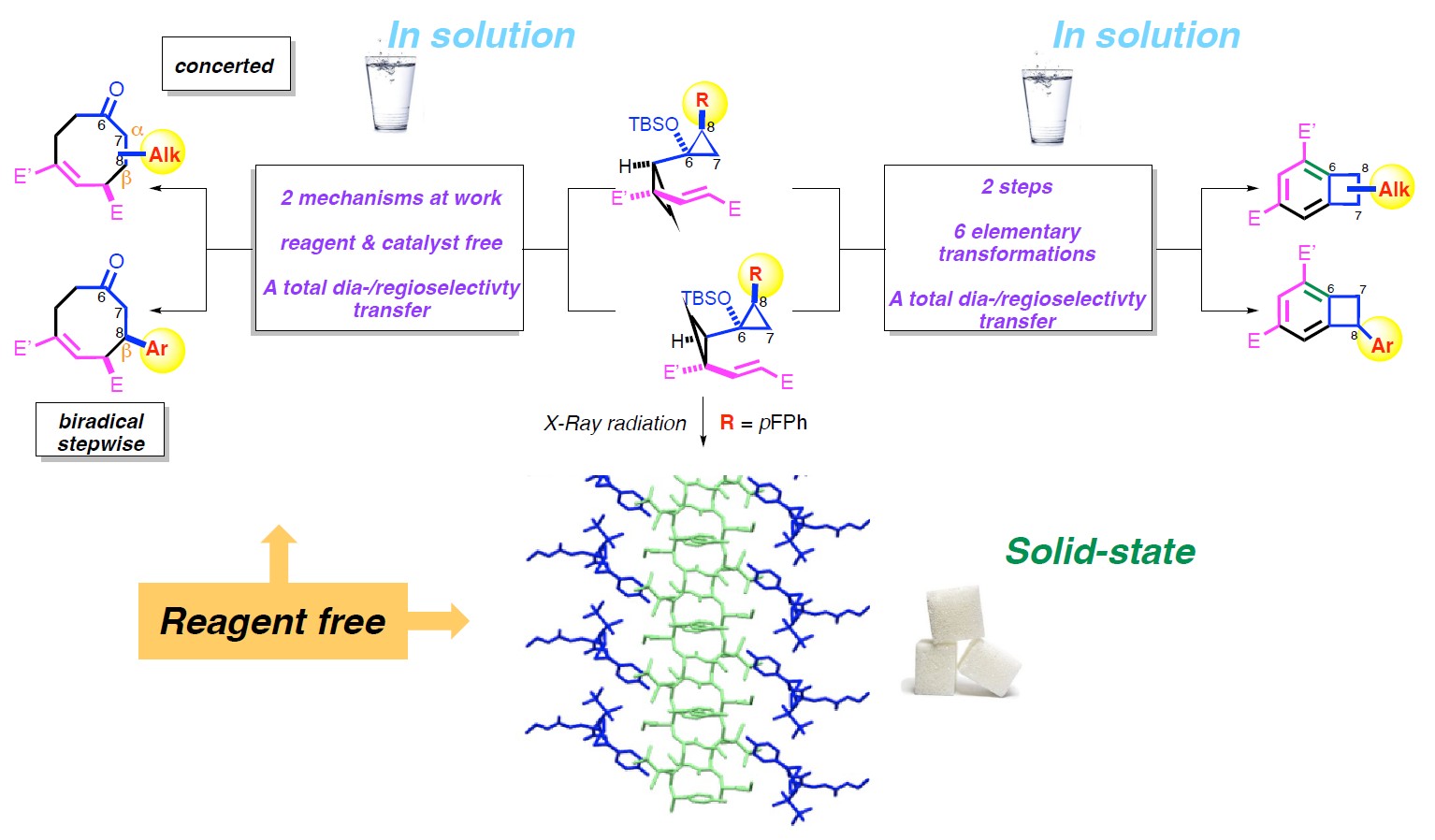

This account critically examines three distinct activation modes, thermal, catalytic, and photochemical, for our in-house synthesized DACs, studied across two different physical states (solution and solid). Each pathway reveals unique aspects of DAC reactivity and selectivity: thermal synthesis of eight-membered rings (solution phase), rearrangement to benzocyclobutenes (solution phase), and crystal-to-crystal photopolymerization (solid state).

By comparing these three pathways, this work aims to identify key mechanistic differences, evaluate their scope and limitations, and illustrate how both mode of activation and reaction medium contribute to the outcome. Ultimately, this comparative approach offers insights into the interplay between molecular design, reaction conditions, and functional outcomes in DAC chemistry. By bridging the gap between solution-phase and crystal-state reactivity, this study provides insights into how reaction environment dictates selectivity and efficiency in DAC transformations.

2. Solution-phase reactivity of DACs

2.1. Solution-phase synthesis of eight-membered rings

This section summarizes the results recently reported by our group, in which a thermally driven rearrangement of bis-cyclopropyl DACs afforded eight-membered carbocyclic systems under catalyst-free conditions [58].

Medium-sized functionalized cycles (eight- to eleven-membered rings) occupy a unique chemical space [59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66]. Their intermediate size imparts conformational rigidity and distinct three-dimensional geometry that can sometimes enhance biological activity by improving binding affinity, oral bioavailability, and/or membrane permeability compared to both acyclic analogs and rings of other sizes [62, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73]. Despite these advantages, medium-sized rings remain underexplored in drug discovery programs, largely due to well-known kinetic and thermodynamic barriers to their synthesis.

From a synthetic standpoint, medium-sized rings are particularly difficult to access via classical cyclization of linear precursors, which is often entropically disfavored. Moreover, their ring size is small enough to experience destabilizing transannular strain. As such, innovative synthetic strategies are required to overcome these inherent limitations [74, 75, 76, 77, 78].

One promising approach involves ring-expansion reactions, particularly starting from small strained rings like cyclopropanes [79, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85, 86, 87, 88]. The substantial release of ring strain (∼27.5 kcal⋅mol−1) offers a thermodynamic driving force, while appropriate substitution can be employed to guide selectivity.

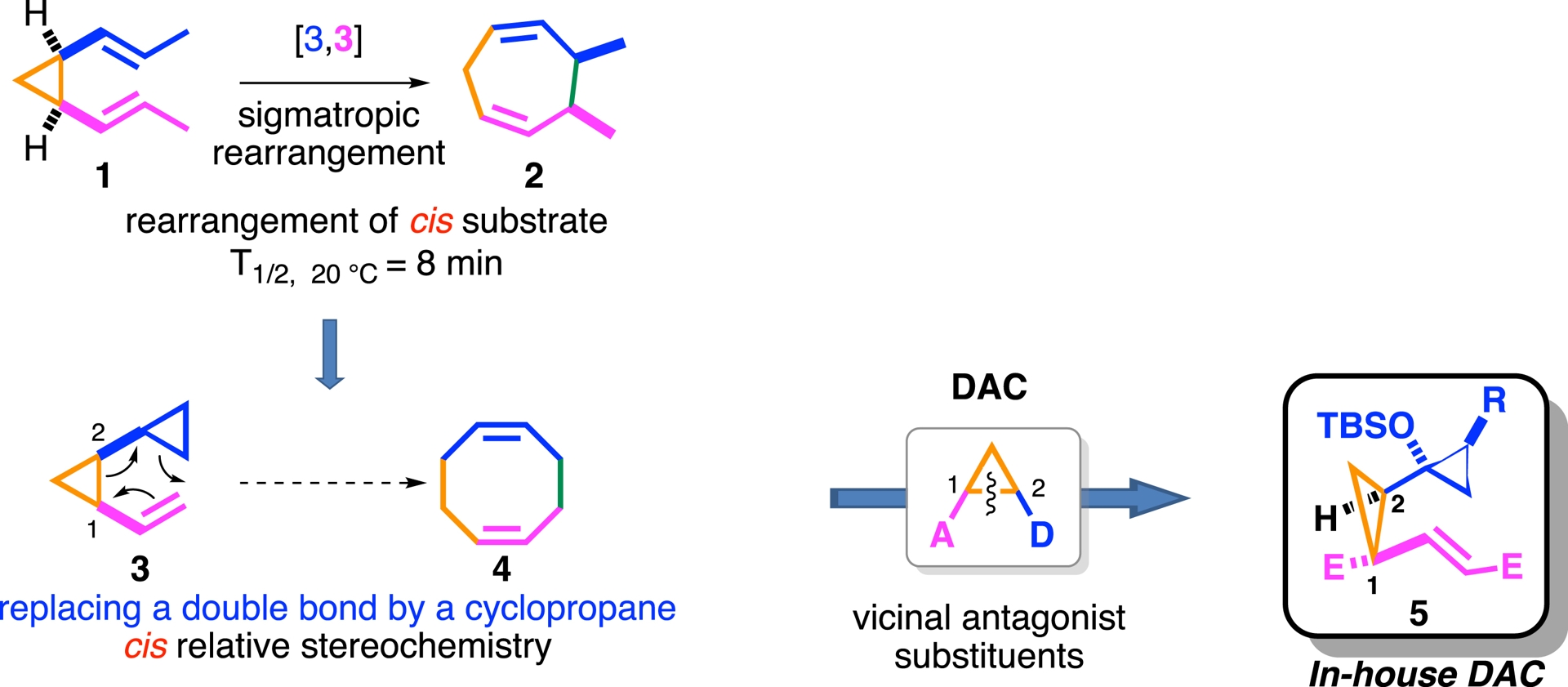

Since divinylcyclopropanes 1 undergo Cope-type rearrangements to form seven-membered rings 2 [89, 90, 91, 92, 93], and given that cyclopropanes can exhibit C–C double bond character1 , we aimed to extend this strategy by replacing one of the alkene units with a cyclopropyl moiety (see compound 3, Scheme 1). This modification would provide the additional carbon atom needed to access eight-membered carbocyclic frameworks.

Design of a strategy.

It is also worth noting that, for this rearrangement to occur at room temperature or even below, a cis relationship between the two olefin partners is necessary (see compound 1, Scheme 1) [94]. Therefore, a cis relationship at the C1 and C2 positions should be considered a prerequisite in the design of precursor 3.

At the heart of this approach lies the donor–acceptor cyclopropane (DAC), a class of reactive intermediates known for their versatility (see Introduction). In our design, a gem-ester/vinyl ester motif was employed as the electron-withdrawing component to promote C1–C2 bond cleavage (see compound 5). The donor moiety consisted of a cyclopropyl group, whose donor reactivity has been previously demonstrated [95, 96, 97, 98, 99, 100, 101]. To further enhance donor ability and facilitate rearrangement, an alkoxy substituent was introduced, inspired by the known behavior of vinyl cyclopropanols [102, 103, 104, 105, 106], (for reviews, see [107, 108]).

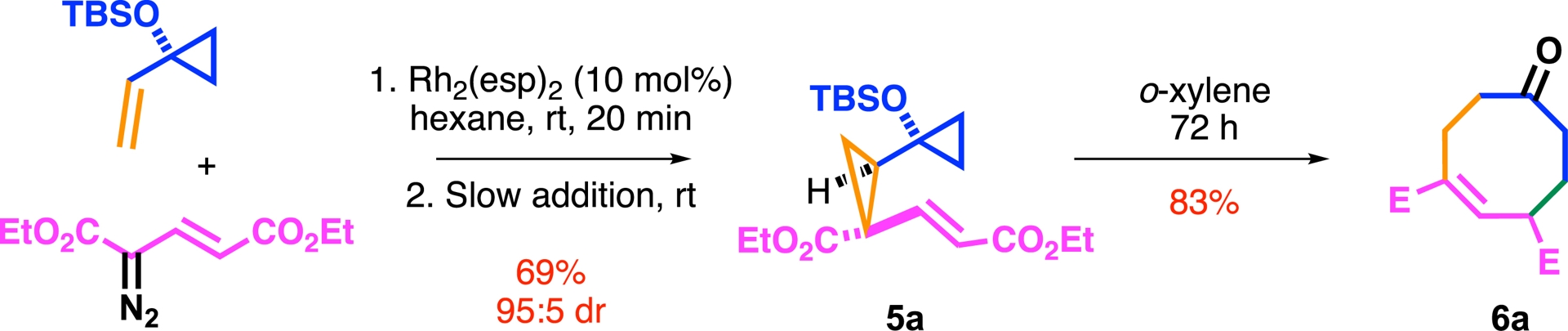

This design merges strain-release strategies with sigmatropic rearrangement logic, as illustrated in Scheme 1. From a structural perspective, the resulting precursor 5 resembles a modified Cope system, in which one π-bond is replaced by a bent reactive cyclopropane [40]. The synthesis of biscyclopropane 5a, obtained in only four steps, relies on a classical Rh(II)-mediated cyclopropanation reaction between a vinylcyclopropane and a di-acceptor diazo derivative (Scheme 2). Notably, after three days of reflux in xylene, the designed DAC 5a successfully delivered the expected eight membered ring 6a in 83% yield.

With this platform in hand, we quickly recognized that the nature of the substituent on the donor portion of the molecule (R in biscyclopropanes 5, Scheme 1) significantly influences the reaction outcome, revealing the existence of two distinct mechanistic pathways.

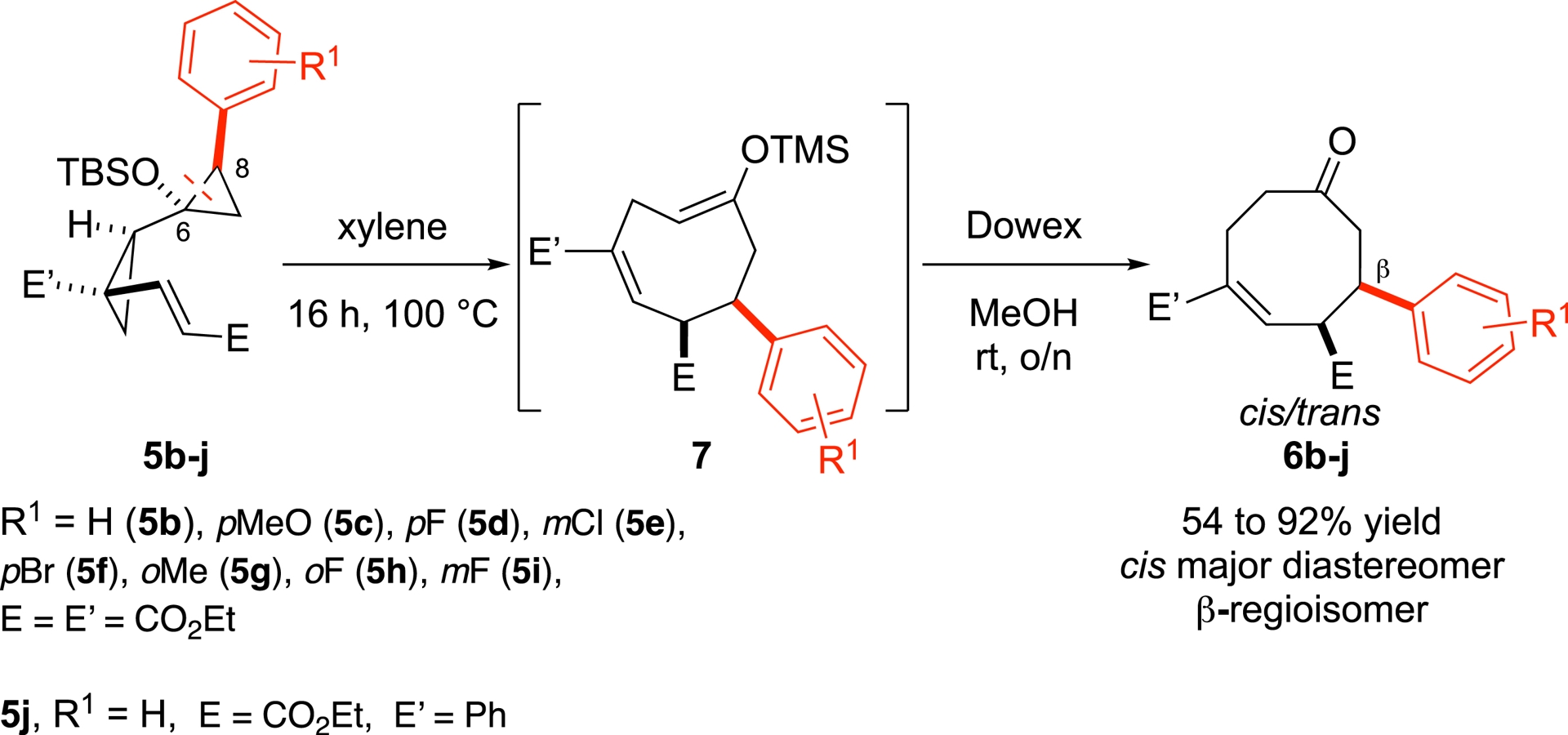

Aryl-substituted biscyclopropanes 5b–j underwent thermal cyclization at 100 °C to afford the corresponding eight-membered Z-enol ethers 7, which were subsequently hydrolyzed to ketones 6b–j using Dowex H+ cation-exchange resin (Scheme 3).

Exploring the aryl scope of the Cope-type rearrangement.

Electron-rich, electron-poor, and ortho-, meta-, or para-substituted aryl groups all participated successfully in the cyclization (yields ranging from 54 to 92%), furnishing mixtures of cis-/trans-diastereomers (50:50 < d.r. < 95:5) but consistently yielding the same β-regioisomer of ketones 6b–j. These results suggest that, in aryl-substituted systems 5b–j, the C6–C8 bond is cleaved selectively during the rearrangement.

In contrast, the outcome of the cyclization for alkyl-substituted biscyclopropanes displayed a strong dependence on both the size of the R groups (Scheme 1) and the nature of the starting diastereomers 5k–p and 5n–p′ (Scheme 4). In these cases, a temperature of 160 °C was required for the reaction to proceed. For secondary alkyl groups 5k–m (R = iPr, Cy), the reactions proceeded with high regio- and diastereoselectivity (yields 70–99%, d.r. > 95:5), indicating a preferential cleavage of the C6–C7 bond, now favoring the formation of the α-regioisomer. In the case of smaller alkyl groups (e.g., R = Me, n-Hex), starting from a mixture of diastereomers 5n–p and 5n–p′, the reaction afforded mixtures of regioisomers 6n–p and 6n–p′, while diastereoselectivity remained excellent (yields 54–90%; d.r. > 95:5, 55:45 < 𝛼/𝛽-regioisomer < 68:32). We showed that the diastereomeric identity of the starting material is fully retained in the regioisomeric outcome, i.e., each diastereomer yields a single regioisomer.

Exploring the alkyl scope of the rearrangement.

These results prompted a theoretical investigation using density functional theory (DFT) to clarify the origin of the observed selectivity. For both methyl 6n and 6n′, and phenyl 6b derivatives, detailed energy profiles were established.

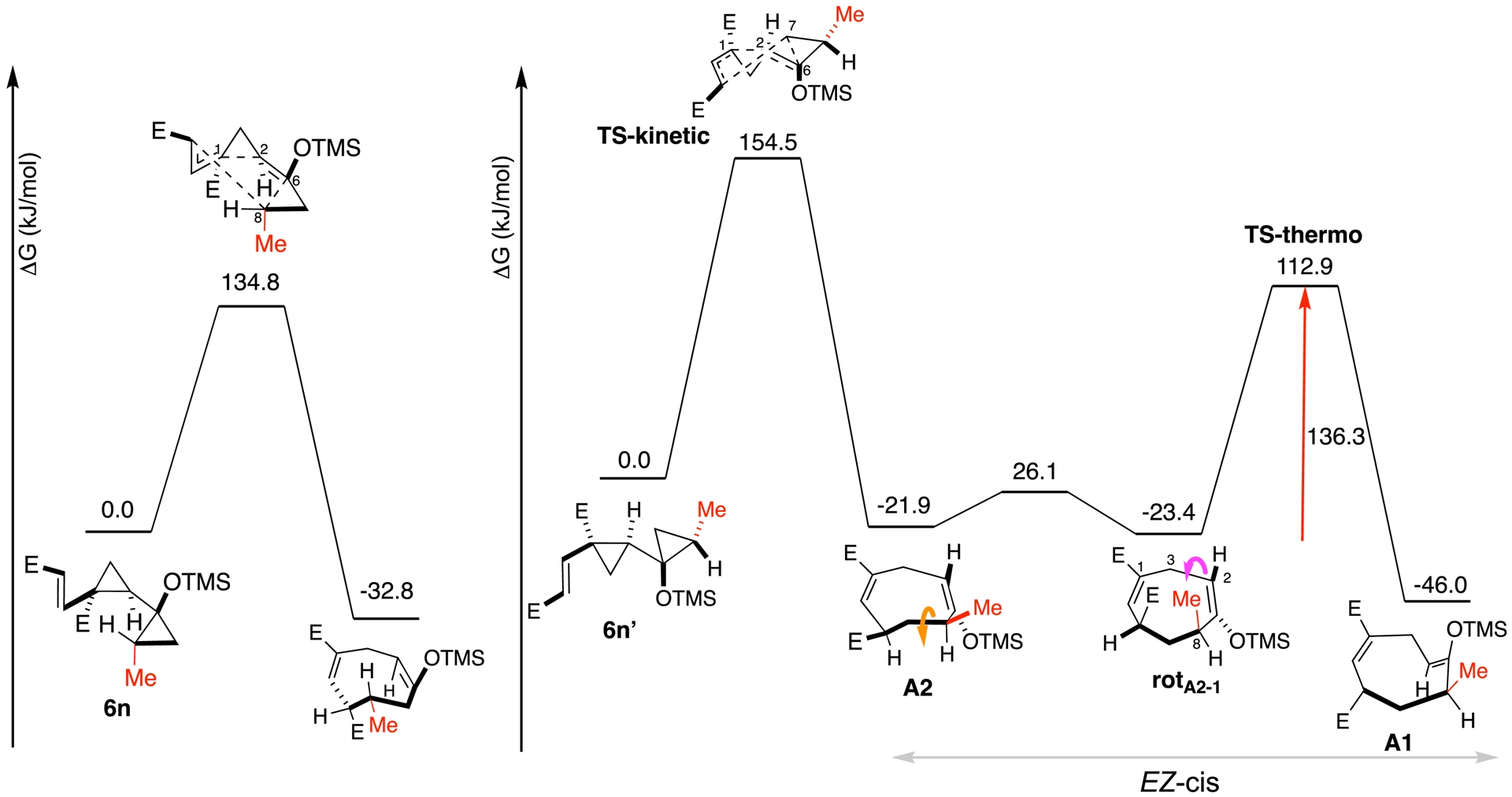

Computational analysis supported a concerted but asynchronous mechanism for both diastereomers of methyl derivatives 6n and 6n′, initiated by the opening of the central cyclopropane ring (Figure 1). In the case of methyl derivative 6n′ (Figure 1, right), two atropisomers of the enol ether (A1 and A2) were identified. A2 was found to exist in two conformations that differed by the equatorial or axial orientation of an ester group (see rotA2−1). The A1/A2 ratio depends on the reaction temperature: A1 was favored at 160 °C, while A2 predominated at 120 °C. This axial chirality arose from restricted rotation around the C2–C3 bond. Computational data indicated that A2 corresponds to the kinetic product, formed more rapidly and preferentially at lower temperature, whereas A1 was the thermodynamic one (Trans-cyclooctenes are known to display atropisomerism. The transient trans-enol ether in a 1,5- or 1,3-cyclo-octadiene has been reported before but as far as our knowledge goes, never in the 1,4 cyclooctadiene case [109, 110, 111, 112, 113]), (for detailed computational studies on (E,Z)-cycloocta-1,4-diene conformers see [114]).

Mechanistic study of the alkyl pathway.

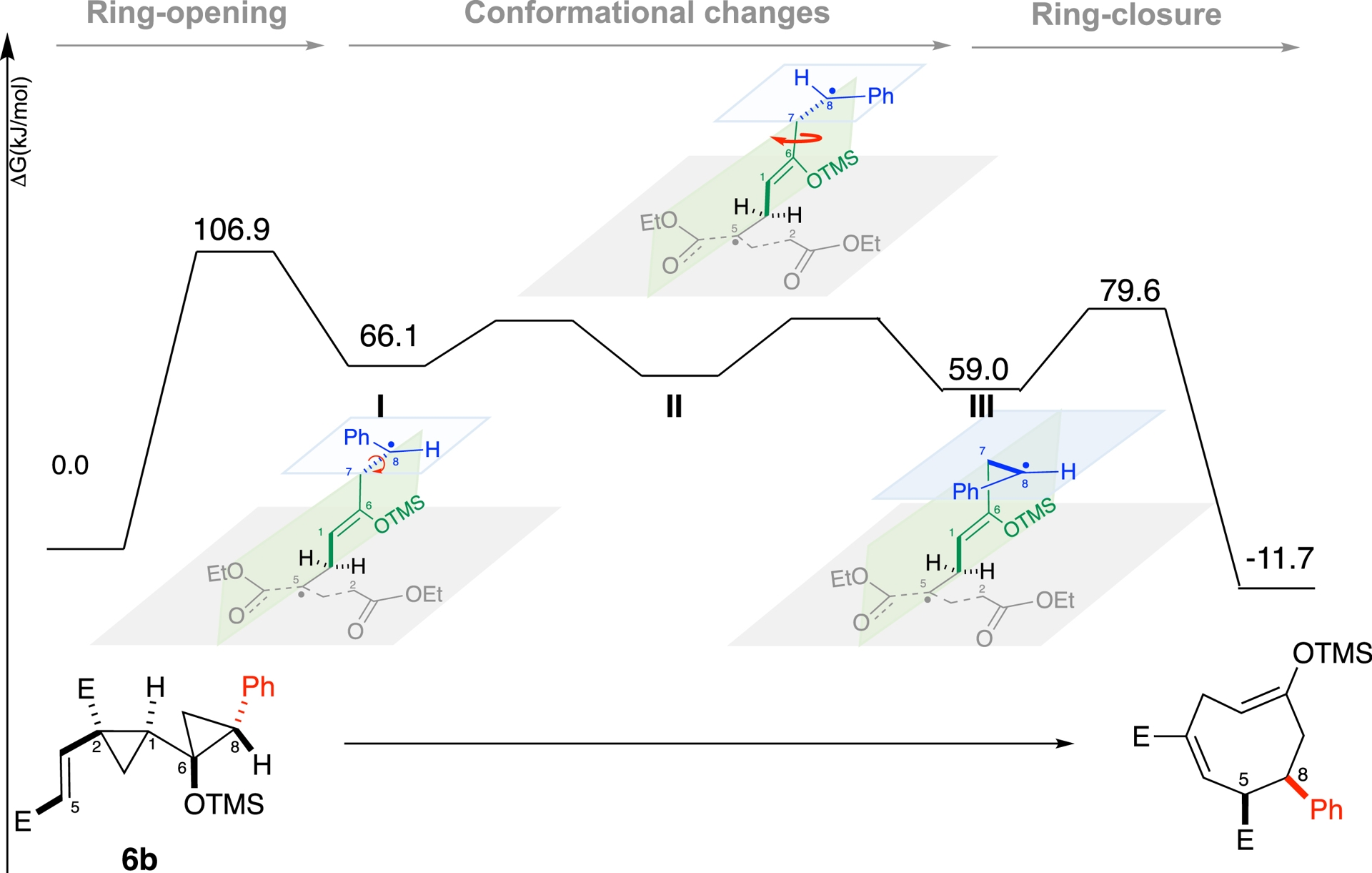

For phenyl derivative 6b, the mechanism diverged. We proposed a stepwise biradical pathway involving the ring opening of the two cyclopropane moieties (Figure 2, Intermediate I), and low-barrier conformational changes (Figure 2, intermediates II and III) before ring closure. This pathway rationalized both the observed regioselectivity and diastereomeric mixtures.

Mechanistic study of the phenyl pathway.

In both cases, calculations show no feasible route to the E-configured enol ethers, consistently with experimental observations.

Through the rational design of DAC-based precursors, we have developed a robust and versatile method for constructing eight-membered carbocyclic systems under simple thermal conditions. This reaction achieved key transformations in a single operation: ring opening of two cyclopropane moieties, formation of a new C–C bond, and generation of a medium-sized ring, all achieved in a catalyst-free, thermally driven process.

The transformation is regio- and stereoselective, and it accommodates a range of substituents. Two mechanistic pathways were identified, a concerted asynchronous route and a biradical stepwise one, depending on the electronic and steric nature of the donor part of the molecule.

This work demonstrates the powerful synergy between molecular design, experimental validation, and computational insight, offering new opportunities for the efficient and selective synthesis of challenging medium-sized ring systems.

2.2. Rearrangement of DACs to benzocyclobutenes

As part of our ongoing investigation into the reactivity of our DAC frameworks, we identified an unanticipated rearrangement pathway leading to the formation of benzocyclobutene derivatives [115].

Benzocyclobutenes are valuable synthetic species (for reviews on benzocyclobutenes, see [116, 117, 118]), notably due to their ability to generate o-quinodimethane (oQDM) intermediates [119] under thermal or photochemical conditions. They play a key role in natural product synthesis, medicinal chemistry [120, 121, 122, 123, 124, 125, 126, 127, 128], and polymer/material science [129, 130, 131, 132, 133, 134, 135, 136]. While numerous synthetic methods have been reported (for seminal reports, see [137]; for selected examples, see [116, 117, 118, 138, 139, 140, 141]), a general and broadly applicable approach remains challenging. We believed that we could contribute to this effort by offering a complementary strategy.

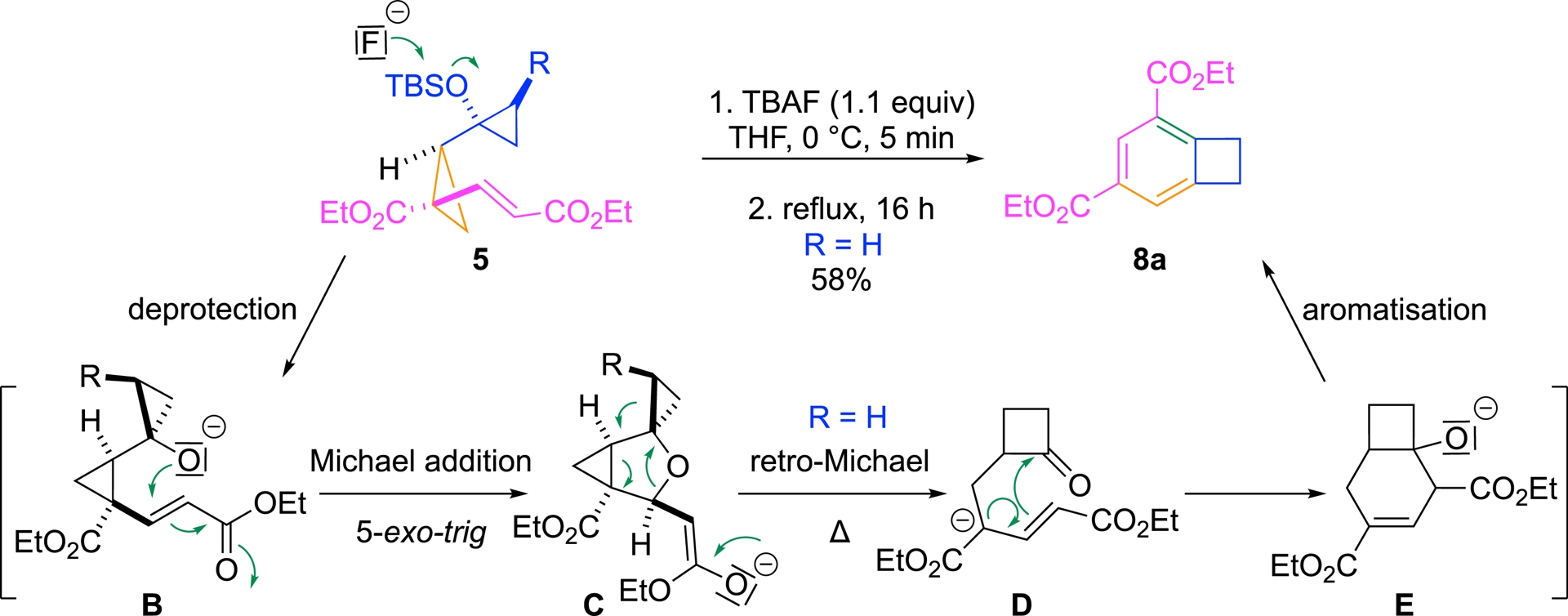

Remarkably, this transformation originates from the same DAC precursors 5 that we previously employed in our annulation cascade strategy. In the presence of a fluoride anion, a skeletal reorganization occurred, but the product outcome differed significantly from our initial expectations. Upon refluxing DAC precursor 5a (R = H) in THF for 16 h in the presence of a fluoride source (TBAF), benzocyclobutene product 8a was obtained in 58% yield (Scheme 5).

Rearrangement of the DAC precursor in the presence of TBAF.

Mechanistically, the reaction likely begins with fluoride-mediated deprotection of the tertiary alcohol, generating alkoxide intermediate B, which could undergo a hetero-Michael addition to the neighboring vinyl ester. Subsequent retro-Michael fragmentation of moiety C could induce ring expansion to a four-membered ring ketone D, reminiscent of known rearrangement of 1-silyloxy-1-vinylcyclopropanes. The resulting ketone D could undergo an intramolecular aldol-type condensation to form bicyclic intermediate E, followed by elimination and aromatization to yield the final benzocyclobutene scaffold 8a. Crucially, the proposed mechanistic sequence is not purely hypothetical. Each intermediate along this pathway was successfully isolated and fully characterized. These experimental findings provide direct validation for the stepwise mechanism.

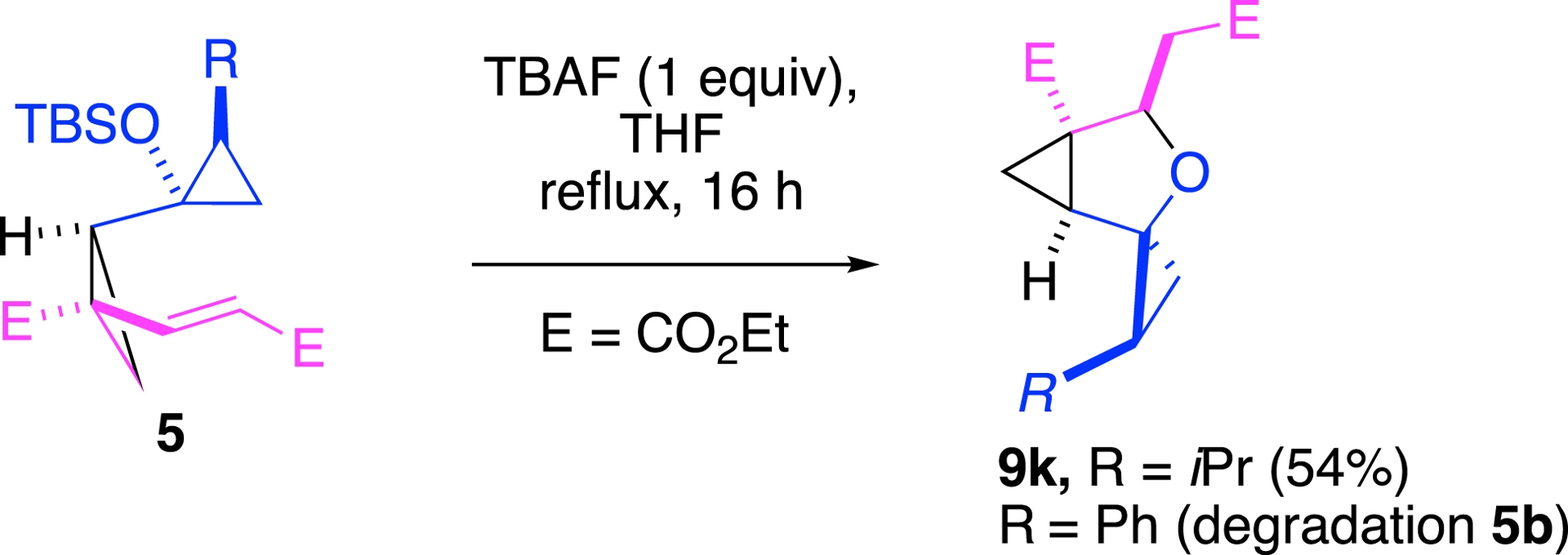

However, this fluoride-mediated protocol showed limitations. When a substituent was present on the donor portion of DAC 5 (R ≠ H), the reaction either stalled at the formation of tetrahydrofuran 9k (R = iPr; 54% yield) (Scheme 6) or led to complete degradation of 5b (R = Ph).

A very limited scope.

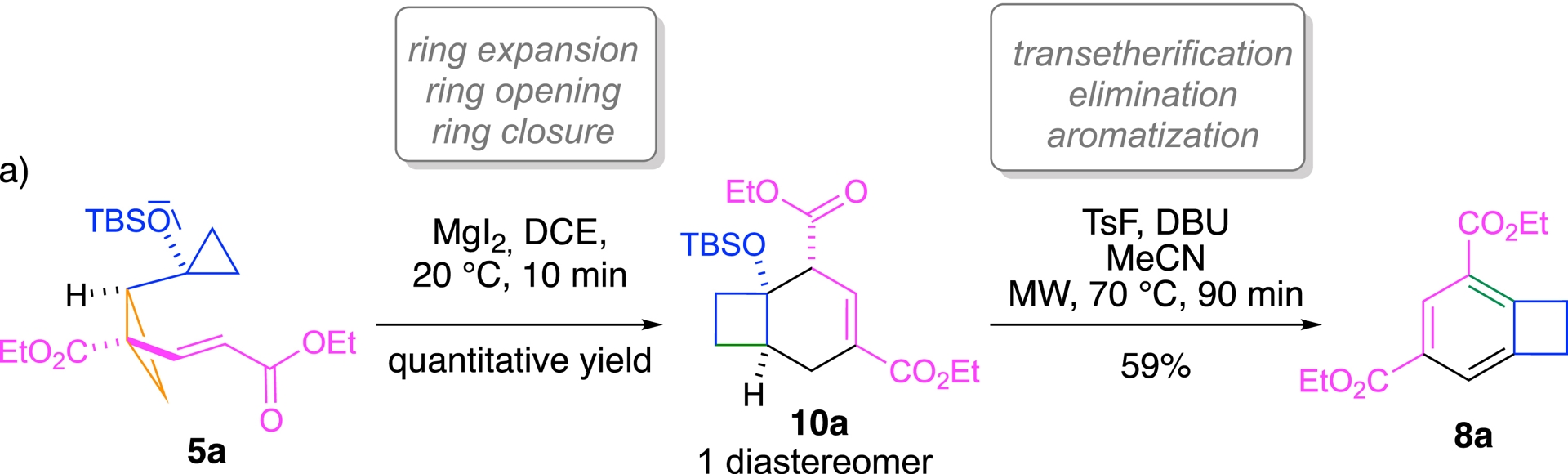

In response, we developed an alternative two-step route. Initial exposure of the precursor 5a to MgI2, used as a mild Lewis acid, rapidly (10 min only) triggered the formation of bicyclic product 10a by a ring-expansion/ring-opening/ring-closure domino sequence (Scheme 7). This intermediate could then undergo a mild base-induced transetherification/elimination/aromatization step, ultimately affording the desired benzocyclobutene 8a in 59% yield [142].

An alternative two-step route.

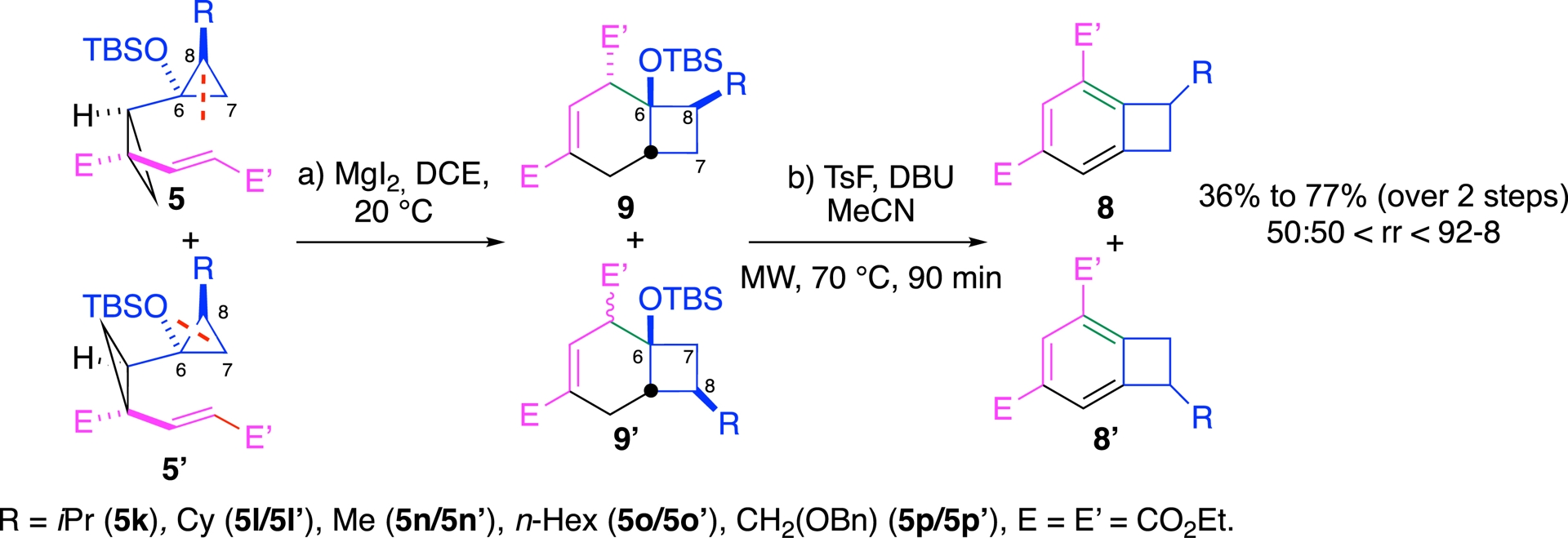

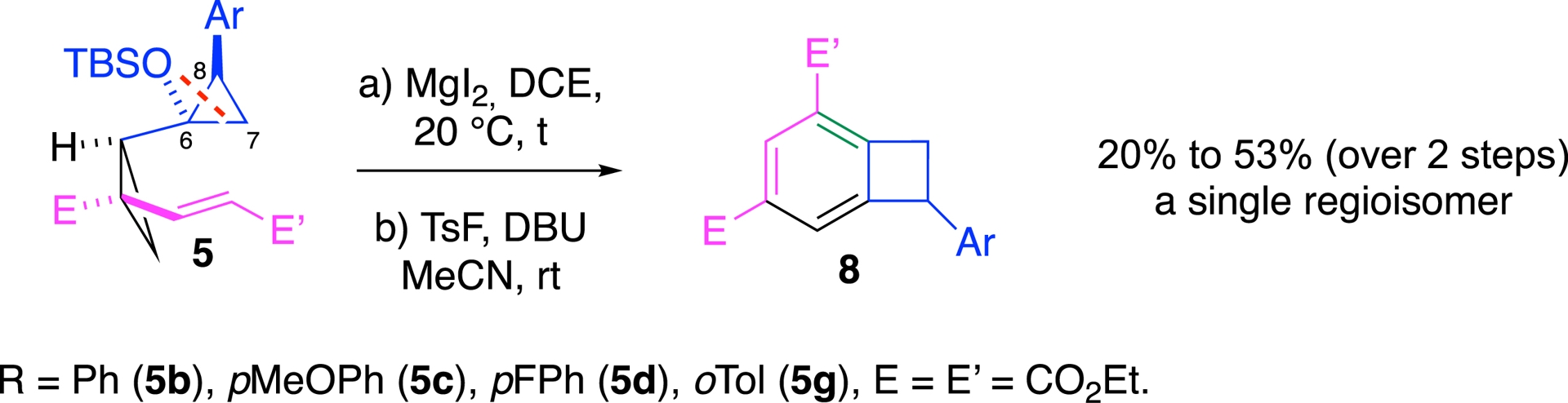

This sequence tolerated a range of substituents (R = primary and secondary alkyl, aryl) and could be applied to a broader set of substrates. As in the previous approach, regioselectivity was controlled by the relative configuration of the starting diastereomer.

For alkyl derivatives, each diastereoisomer led exclusively to a distinct regioisomer. For instance, compound 5n (R = Me) underwent C6–C7 cleavage to furnish regioisomer 8a (R = Me), while its diastereomer 5n′ (R = Me) followed an alternate bond reorganization route (C6–C8 bond cleavage), yielding regioisomer 8a′ (R = Me) (Scheme 8). This strict correspondence between initial stereochemistry and final regioisomer demonstrates a complete transfer of diastereoselectivity into regioselectivity, offering rare predictive control over the product distribution.

Alkyl derivatives—total transfer of diastereoselectivity into the regioselectivity.

The nature of the substituent profoundly impacted the regioselectivity of the DAC ring opening. Aryl-substituted analogs consistently favored C6–C8 cleavage (Scheme 9).

Aryl derivatives—the opposite regioisomer.

These divergent behaviors echo isolated reports in related cyclopropyl ether systems [58, 143] and also other cyclizations [144]. A concerted mechanism likely governs the alkyl series, minimizing steric repulsion in the transition state, whereas the aryl series appears to favor a stepwise pathway, enabled by stabilization of a benzyl carbocation intermediate. These findings demonstrate how fine-tuning the electronic profile of DACs can serve as a powerful tool to control reactivity and regioselectivity across mechanistically distinct pathways.

The elegance of this approach lies in its conciseness, a two-step sequence encompassing six elementary transformations, all initiated from a simple yet functionally rich cyclopropane framework. The method offers a direct and efficient route to benzocyclobutene scaffolds, with complete regio- and diastereocontrol, and compatible with a range of functional groups.

Taken together, these results not only unveil a new facet of DAC reactivity but also underscore the power of combining ring strain, stereoelectronic effects, and tailored reaction conditions to access otherwise challenging molecular architectures.

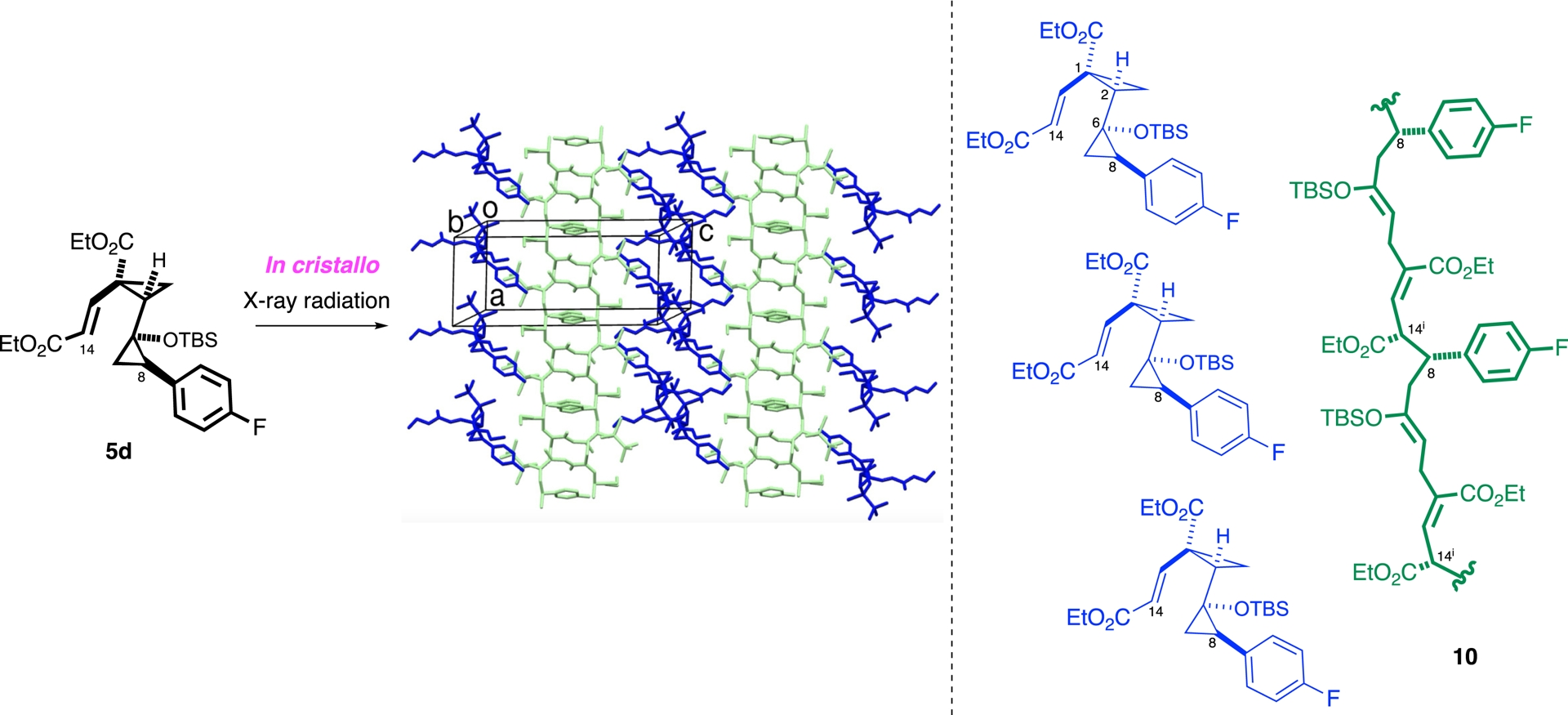

3. Solid-state photopolymerization of donor–acceptor cyclopropanes

In our recent investigations of DACs, we identified an unexpected reactivity pathway occurring in the solid state, distinct from the thermal behavior observed in solution. While characterizing vinyl bis-cyclopropane compound 6a (R1 = p-F) by single-crystal X-ray diffraction (SCXRD), we unexpectedly found that even a short exposure (10 min) to Cu radiation triggered a notable transformation of the crystal packing, leading to the emergence of a layered structure composed of both intact monomers and newly generated polymer chains (Scheme 10, left side) [145]. Structural analysis indicated that polymerization proceeded via ring opening of both cyclopropane units, leading to covalent linkage between benzylic (C8) and vinyl carbons (C14) of adjacent monomers. The resulting polymeric chain 10 (Scheme 10, right side) displayed two non-conjugated Z-alkenes and two stereocenters per repeating unit, features difficult to access via conventional solution-phase methods.

Topochemical polymerization.

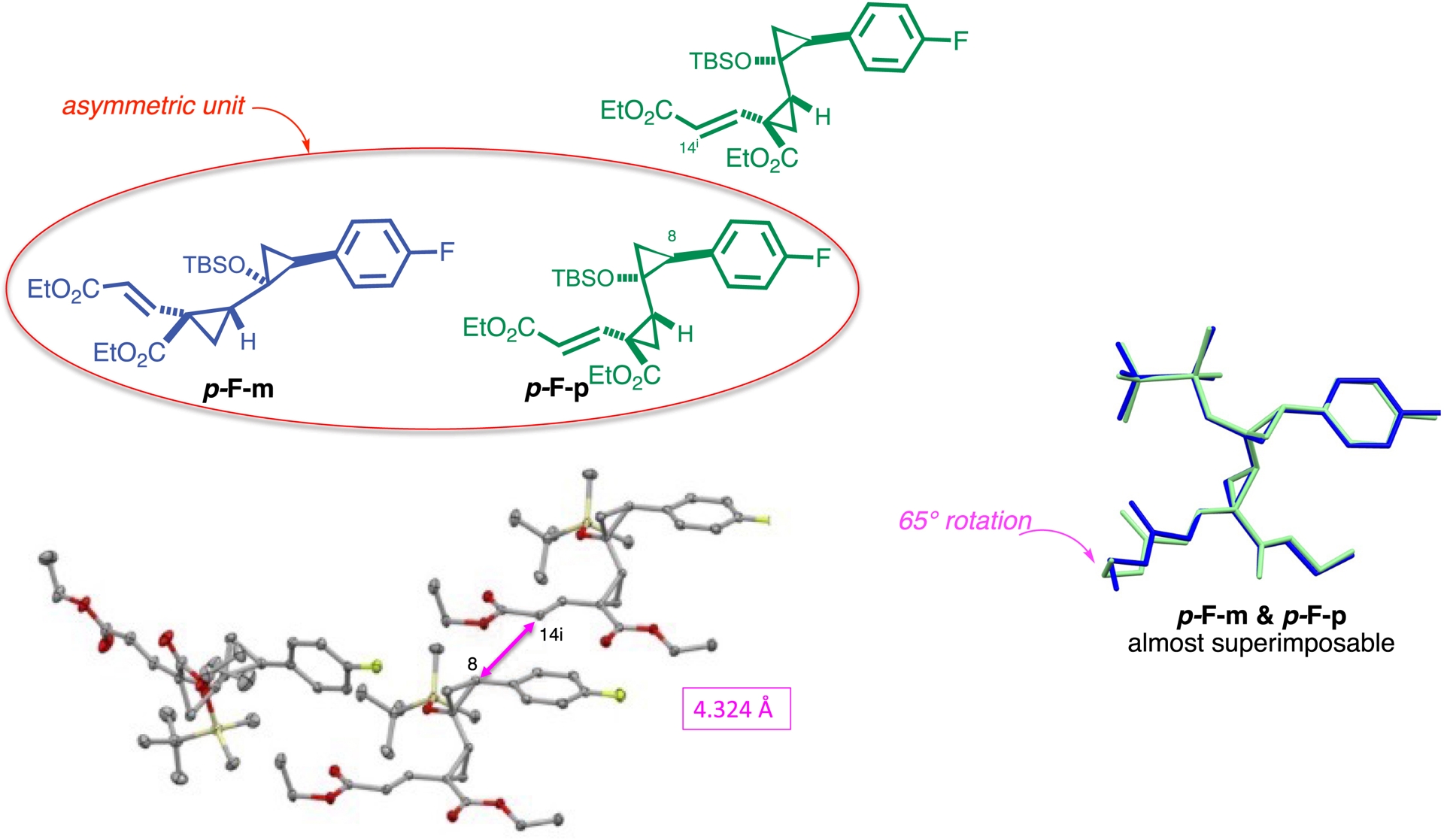

To gain structural insight into the pre-reactive state of the crystal, we performed SCXRD analysis at 150 K, a temperature deliberately chosen to lie below the reaction threshold. Under these conditions, the system remains unreactive, allowing direct observation of the intact monomer. The structure revealed the presence of two closely related conformers, p-F-m and p-F-p, coexisting in the asymmetric unit (Scheme 11). These conformers were nearly superimposable, differing primarily by an approximate 65° rotation around the terminal ethyl group of the vinyl ester (Scheme 11, right side). Notably, only the p-F-p conformer adopted a spatial arrangement favorable for topochemical polymerization, with a distance of 4.324 Å between the reactive carbons C8 and C14i, allowing head-to-tail propagation along a crystallographic axis (Schmidt’s rules say a distance < 4.2 Å is needed between reactive site for a topochemical reaction to occur [146] and see reference [46] but this can be overcome if there is enough void space in the crystal to allow molecular movement [147, 148]). Due to the centrosymmetric packing of the crystal, polymer growth proceeds in a racemic fashion. This structural snapshot illustrates how small conformational variations and crystal symmetry elements govern the selectivity and outcome of solid-state transformations.

Initial crystal packing of the monomer.

To explore the generality of the observed solid-state reactivity, we extended our study to a broader set of DAC derivatives. Among the compounds tested, only the para-chlorobenzene p-Cl and meta-fluorobenzene m-F analogs exhibited molecular arrangements compatible with topochemical reactivity. Measurements by SCXRD performed at 150 K revealed that each of these derivatives crystallized with a single conformer per asymmetric unit.

The p-Cl derivative underwent a temperature-dependent transformation that could be resolved into a series of well-defined intermediate states, ultimately leading to a topochemical polymerization. Upon warming to 250 K, two partially reacted species were detected in a 2:1 occupancy ratio. In the dominant species, the inner C–C bond of one cyclopropane stretched to 1.713(9) Å. In the minor species, full ring opening of the second cyclopropane was observed. This transformation progressed further at 270 K, with the reactive bond reaching 1.87(1) Å. These structural snapshots suggest a possible manifestation of push–pull polarization, as evidenced by progressive bond elongation prior to full cleavage. While this behavior aligns with expectations for DAC systems, it must be interpreted cautiously, since crystallographic data alone do not offer direct insight into electronic structure [149]. By 290 K, the crystals did not diffract anymore, reflecting the loss of crystalline integrity. In contrast, the m-F analog, despite its favorable preorganization, showed no signs of reactivity at any measurement temperature.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations revealed that favorable alignment of reactive centers must be coupled with sufficient molecular motion to allow bond reorganization. For p-F, such motions, especially perpendicular to the polymerization axis, were accommodated without compromising lattice coherence. In the case of p-Cl, movement was largely restricted to the direction of polymerization, resulting in mechanical stress and crystal collapse during the polymer growth. Despite its favorable packing and geometric preorganization, m-F remained unreactive. This lack of reactivity can be attributed to an insufficient number of internal degrees of freedom. There was not enough conformational flexibility to accommodate the structural rearrangements required for polymerization. Interestingly, the non-reactive conformers in p-F played a stabilizing role, possibly acting as molecular templates [150, 151]. This divergence underscored the importance of not only geometric alignment, but also conformational flexibility and packing plasticity in enabling productive reactivity.

Collectively, these observations demonstrated that the crystalline environment acts as a true reaction variable, comparable to classical parameters such as temperature or pressure. It not only influences reaction rates, but also determines mechanistic pathways and enables access to product architectures that remain elusive in solution [55, 56, 152, 153, 154, 155, 156]. The topochemical constraints observed in DAC systems reveal a distinctive mode of reactivity, intimately tied to molecular packing and conformational freedom.

The combined use of SCXRD and molecular dynamics simulations [157, 158, 159]2 provided an atomically resolved view of this rare single-crystal-to-single-crystal polymerization. This approach allowed us to capture the interplay between molecular orientation, symmetry, and lattice plasticity with unprecedented clarity. Although predicting whether a given reaction will proceed in the solid state remains challenging, the introduction of ring strain and, more broadly, of built-in structural tension that seeks release, emerges as a promising strategy to bias systems toward reactivity under topochemical constraints.

4. Critical discussion

Beyond their distinct activation conditions, the contrasting reactivity profiles of donor–acceptor cyclopropanes (DACs) in solution and in the solid state emphasize the structural versatility and mechanistic richness in this class of compounds. In solution, DACs undergo cascade transformations such as ring expansion, rearrangement, and condensation, typically under mild thermal or basic conditions and often without the need for additional catalysts. These processes are largely governed by the intrinsic electronic polarization of the substrate and, critically, by the release of ring strain embedded in the cyclopropane core. This strain allows complex bond reorganizations to occur efficiently and selectively.

In the solid state, DACs display a fundamentally different mode of reactivity. The transformation is constrained by crystal packing, requiring precise preorganization of reactive units and sufficient lattice flexibility. Under these topochemical conditions, polymerization or bond cleavage occurs only when the spatial arrangement is favorable. Yet here too, ring strain plays a central role—facilitating the reaction by providing a thermodynamic incentive for bond rupture, even in the absence of molecular mobility. Although predicting whether a given transformation will proceed in the solid state remains inherently challenging, the deliberate incorporation of strain—and more generally, of structural tension that seeks release—emerges as a rational design element to bias systems toward productive reactivity.

However, a key limitation of this approach lies in its lack of scalability. To date, the solid-state transformations that we observe remain confined to single-crystal-to-single-crystal conversions, which require highly ordered materials and low-throughput handling. We have not yet identified operationally simple or bench-stable conditions that would enable these reactions to be performed in batch or on preparative scale. As such, while mechanistically instructive and structurally unique, the synthetic utility of these transformations is currently constrained by practical considerations.

Importantly, the reactivity principles traditionally associated with vinyl-cyclopropanol derivatives—well-known for undergoing ring opening and rearrangement—can be effectively transposed to biscyclopropanol systems. These more complex frameworks preserve the electronic and conformational features of their monosubstituted analogs but introduce new degrees of freedom and stereochemical control. In this context, the complete transfer of stereochemical information into regioselectivity, where each diastereomer leads unambiguously to a specific regioisomer, highlights the importance of geometric predisposition in steering divergent mechanistic pathways. This observation underscores how subtle differences in molecular orientation in strained systems can dictate not only product identity but also reaction trajectory.

Together, these insights consolidate DACs as uniquely powerful platforms for controlling molecular reorganization across environments. Whether in solution or in the solid state, they provide rare access to structurally complex, stereochemically defined products through mechanistically distinct yet conceptually unified strategies.

5. Conclusion and future directions

Taken together, these studies emphasize the synthetic potential of donor–acceptor cyclopropanes as highly versatile platforms for molecular construction. Whether activated in solution through well-orchestrated domino sequences or engaged in solid-state transformations dictated by lattice constraints, DACs enable access to diverse and otherwise challenging structural motifs. The capacity to translate reactivity patterns, such as ring expansion or rearrangement, from simpler vinyl-cyclopropanol systems to more elaborate bis-cyclopropane derivatives, further highlights the adaptability of this class of compounds. Beyond their synthetic utility, these transformations offer rare mechanistic insights into the interplay between strain release, stereoelectronic effects, and medium-dependent selectivity. This duality of behavior not only broadens the scope of DAC chemistry but also opens new avenues for rational design of reactivity, both in and beyond conventional solution-phase settings.

Acknowledgments

I would like to express my gratitude to my coworkers and collaborators who participated in this project: Dr. Bohdan Biletskyi, Dr. Sara Chentouf, Dr. Pierre Colonna, Professor Laurent Commeiras, Dr. Maxime Dousset, Dr. Virginie Héran, Dr. Kévin Masson, Dr. Jean-Valère Naubron, Dr. Paola Nava and Dr. Fabio Ziarelli. This work was supported by the computing facilities of the “Centre Régional de Compétences en Modélisation Moléculaire de Marseille” (CRCMM).

Declaration of interests

The authors do not work for, advise, own shares in, or receive funds from any organization that could benefit from this article, and have declared no affiliations other than their research organizations.

Funding

We gratefully acknowledge the Agence Nationale de la Recherche (project ANR-18-CE07-0005/Benz) for its financial support. We thank the French Ministère de l’Enseignement Supérieur et de la Recherche (MESR) for PhD fellowships. We also acknowledge institutional financial support from Aix-Marseille Université (AMU), the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS), and Centrale Méditerranée.

1 In cyclopropane, the internal bond angles are forced to be 60°, far from the ideal 109° angle, causing severe angle strain. To relieve strain, the carbon atoms in cyclopropane adjust their hybridization toward more p-character (closer to sp2). This gives the C–C bonds some characteristics of π-bonds, similar to those in alkenes.

2 To the best of our knowledge, molecular dynamics (MD) has rarely been used to study crystal-to-crystal transformations in organic systems.

CC-BY 4.0

CC-BY 4.0