1. Introduction

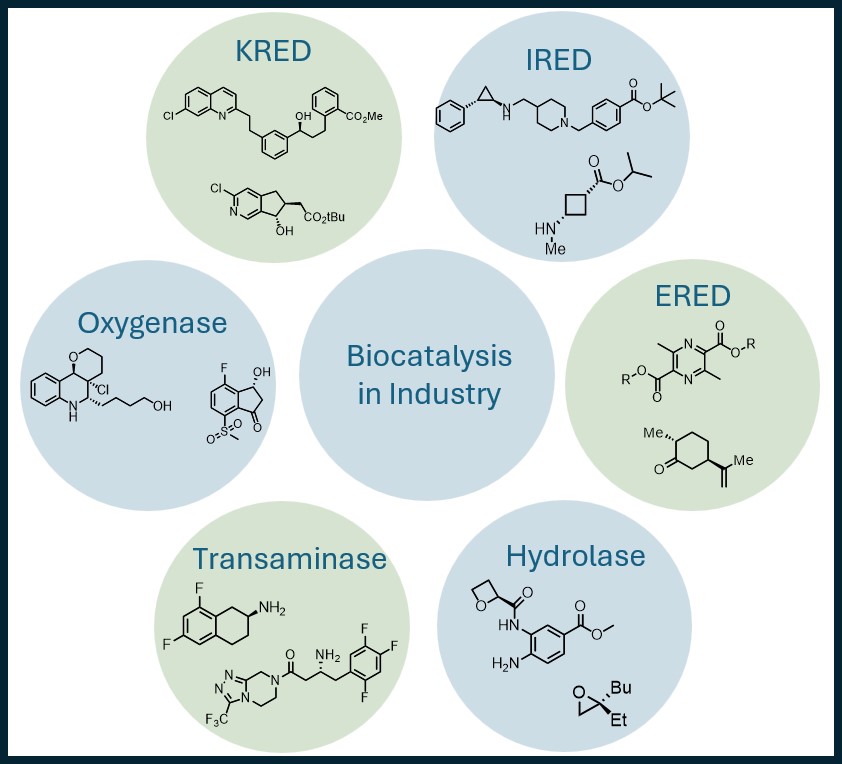

Biocatalytic reactions are characterized by exceptional chemo-, regio-, and enantioselectivity, making biocatalysis a key enabling technology in asymmetric synthesis. In this review, we highlight the most prominent enzyme classes, and more importantly, dozens of successfully implemented examples. We provide relevant conditions for successful biocatalytic reaction execution, including buffers, pH, temperature, and cofactor recycling systems when applicable. A significant number of enzymes are readily accessible through commercial suppliers or through preparation via fermentation of recombinant microorganisms. Crude lyophilized enzyme formulations have facilitated widespread distribution of biocatalysts, while genetic engineering has advanced contemporary enzymatic processes by improving reaction selectivity and productivity. These processes are performed under a diverse array of conditions and in many cases at concentrations comparable to those achieved in traditional synthetic chemistry methods [1].

2. Ketoreductases (KREDs)

Enzymatic reduction of ketones and aldehydes are well-established methods for the synthesis of chiral alcohols. These transformations are catalyzed by a diverse array of enzyme families, including alcohol dehydrogenases (ADHs) and aldo-keto reductases (AKRs), collectively referred to as ketoreductases (KREDs) or carbonyl reductases (CREDs). In their active sites, these enzymes bind NAD(P)H, which delivers a hydride to the carbonyl of interest, producing the chiral alcohol [2].

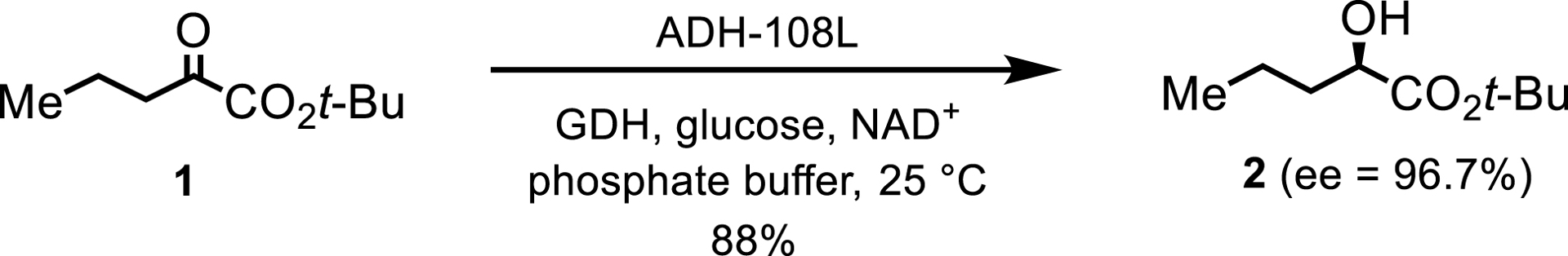

Most examples utilize a second enzyme for NAD(P)H cofactor recycling. Others employ a single enzyme for both ketone reduction and cosubstrate oxidation of propan-2-ol to acetone [3]. Generally, KREDs exhibit broad substrate specificity, although the reduction of ketones with bulky substituents is lacking. For instance, an intermediate for an investigational γ-secretase inhibitor for Alzheimer’s Disease treatment (Scheme 1), 1,1-dimethylethyl (R)-2-hydroxypentanoate 2, was synthesized via enzymatic reduction of a ketoester [4]. The reaction, conducted with 35 kg of ketoester in phosphate buffer and glycerol, utilized low enzyme loadings of ADH-108L and glucose dehydrogenase (GDH), with efficient NAD+ recycling by GDH and glucose.

KRED-catalyzed reduction toward a γ-secretase inhibitor.

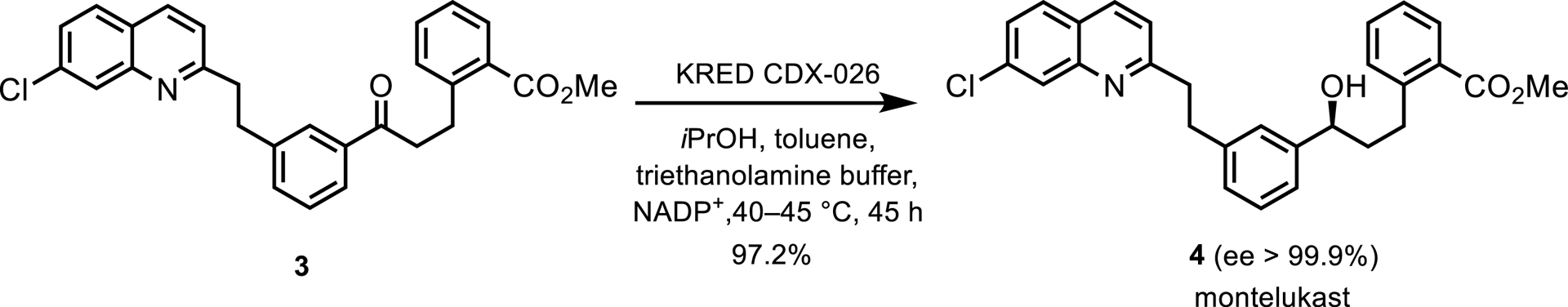

Another example employed an engineered KRED, CDX-026, in the synthesis of an intermediate for montelukast, the active ingredient in Singulair® from Merck (Scheme 2) [1]. The reaction, performed on 230 kg of ketone 3 in a mixture of propan-2-ol, toluene, and triethanolamine buffer, achieved a 97% yield. Crystallization of the alcohol as monohydrate drove the reaction to high conversion without acetone removal, with CDX-026 recycling NADP+ by oxidizing propan-2-ol.

KRED-catalyzed reduction toward montelukast.

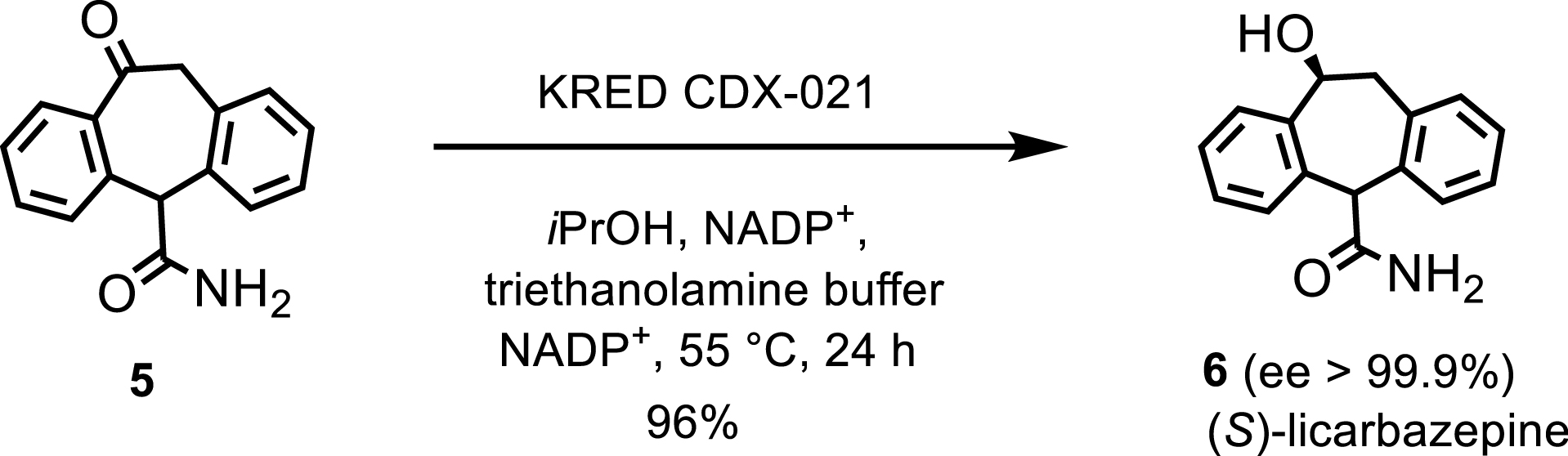

Additionally, an engineered KRED facilitated the scalable synthesis of (S)-licarbazepine, an anticonvulsant [5]. After four rounds of engineering and a design of experiments (DoE) made up of 32 experiments, the process was conducted on a 500 mL scale, 50 g of ketone, and 1% w/w of KRED CDX-021. This produced (S)-licarbazepine 6 in 96% yield after distillation and filtration (Scheme 3). KRED CDX-021 recycled NADP+ by oxidizing propan-2-ol, with a nitrogen sweep removing acetone to drive the reaction forward.

KRED-catalyzed reduction toward (S)-licarbazepine.

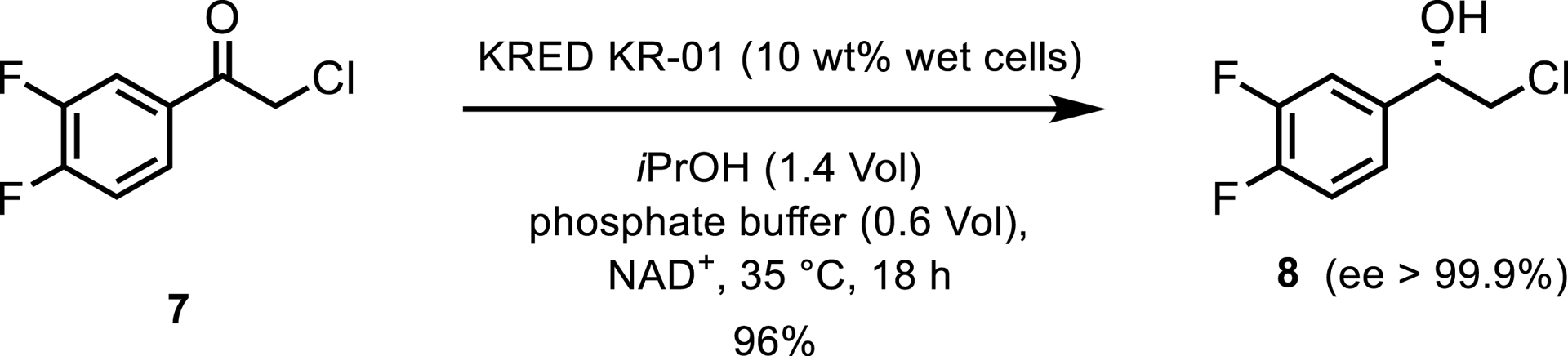

A wild-type KRED from Leifsonia sp. S749 was used to synthesize (S)-2-chloro-1-(3,4-difluorophenyl)ethanol 8, an intermediate for ticagrelor, a treatment for acute coronary syndromes [6]. The enzyme, overexpressed in recombinant E. coli, was used in concentrated conditions with propan-2-ol and phosphate buffer, recycling NAD+ by oxidizing isopropanol (Scheme 4). The reaction was optimized to substrate loadings of 500 g/L and resulted in space time yields of 145.8 mmol/L/h. The same enzyme also converted a different substrate, (R)-1-(3,5-bis(trifluoromethyl)-phenyl)ethanol, also at 500 g/L substrate loading with high yield and high stereoselectivity.

KRED-catalyzed reduction toward ticagrelor.

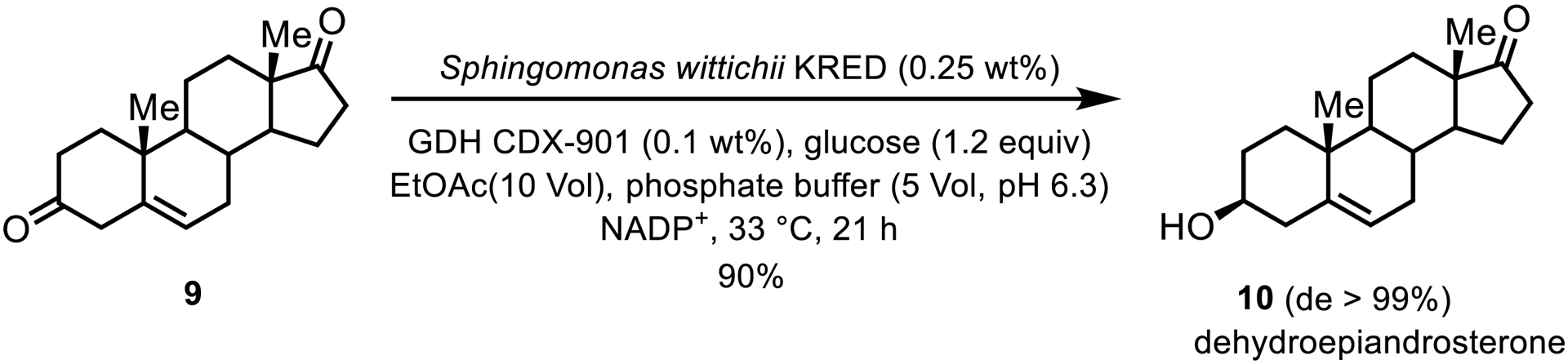

An example of a bulky substrate involved a wild-type KRED from Sphingomonas wittichii for the reduction of 5-androstene-3,17-dione 9 to dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) 10, a precursor for steroidal drugs (Scheme 5) [7]. This KRED was identified by a colorimetric screen in the reverse oxidative direction, to streamline the identification of enzymes which acted on the desired regio- and stereoisomer. The resulting highly stereo- and regioselective reaction produced DHEA with minimal by-products and up to 150 g/L substrate loadings under biphasic reaction conditions.

KRED-catalyzed reduction that produces dehydroepiandrosterone.

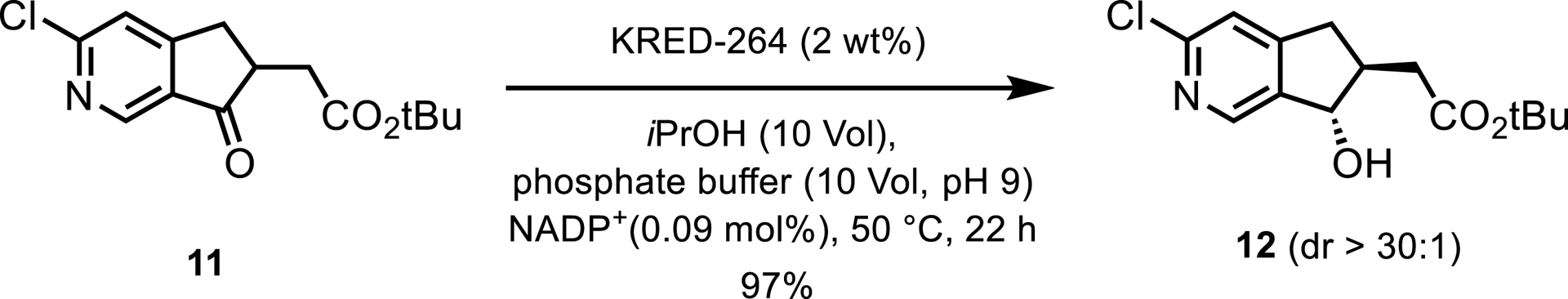

Merck reported a KRED process that involved a dynamic kinetic resolution for the synthesis of an intermediate for a GPR40 partial agonist [8]. Following assessments of the kinetic and free energy profiles of the KRED reaction, and by performing six rounds of enzyme engineering, KRED-264 provided the desired trans diastereomer in high yield and diastereomeric ratio (Scheme 6).

KRED-catalyzed dynamic kinetic resolution towards a GPR40 partial agonist.

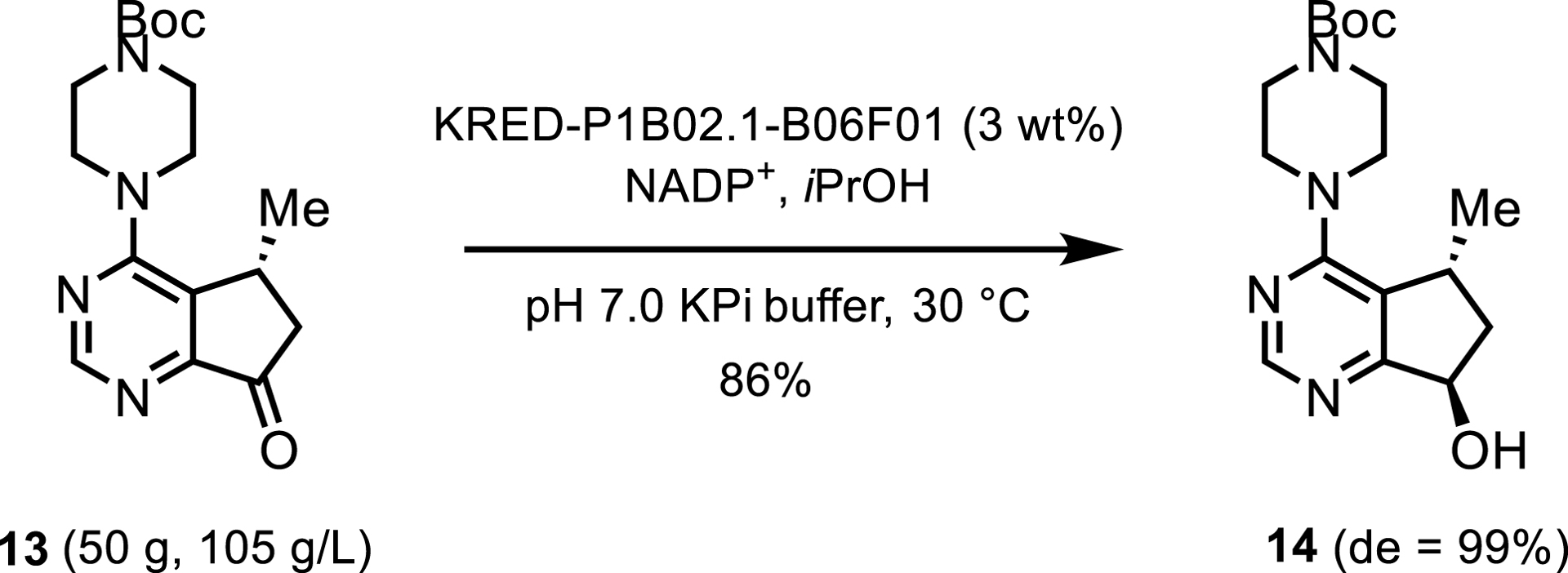

Diastereoselectivity was also a beneficial characteristic of the KRED employed in Roche’s synthesis of investigational cancer therapeutic ipatasertib. The process offered higher yields and diastereomeric ratios than those obtained by the ruthenium- or palladium-catalyzed processes explored in parallel. A commercially available KRED was therefore applied to this route and achieved highly diastereoselective reduction and NADPH regeneration via propan-2-ol oxidation. The overall chemoenzymatic synthesis of ipatasertib has been performed on a hundred-kilogram scale (Scheme 7) [9].

KRED-catalyzed reduction toward ipatasertib.

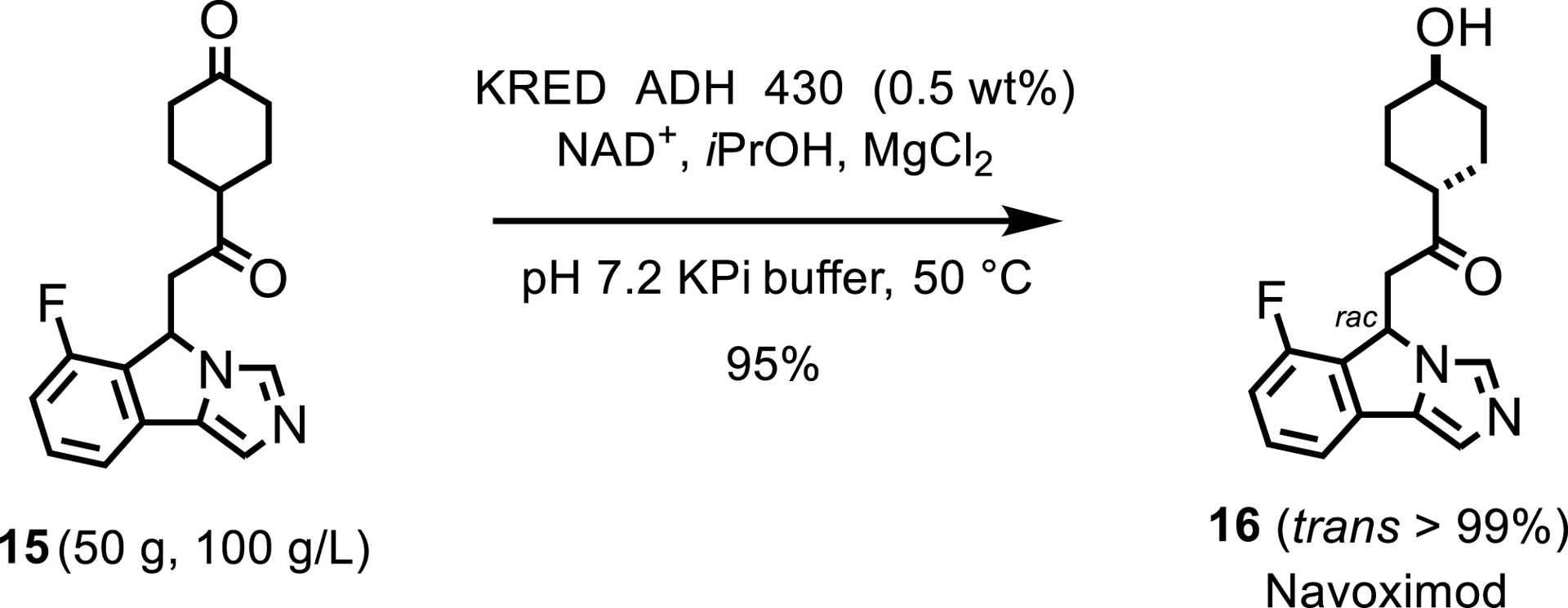

Another report from Roche detailed the synthesis of an intermediate for the indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase inhibitor navoximod. Both ketone moieties of the diketone intermediate were initially targeted for biocatalytic reductions with a screen of 500 KREDs performed; however, a metal hydride reduction was ultimately favored for the central ketone. Their KRED panel was successfully screened resulting in a process scaled up to 50 g scale, achieving high yield and selectivity with low enzyme loading (Scheme 8) [10].

3. Ene-reductases (EREDs)

Ene-reductases (EREDs), a subset of the oxidoreductase enzyme family, are known for their ability to facilitate the asymmetric reduction of electron-deficient alkenes [11]. Distinct from KREDs and imine-reductases (IREDs), which directly utilize NAD(P)H, EREDs operate through a unique mechanism involving hydride transfer from a non-covalently associated, reduced flavin mononucleotide (FMNH2) cofactor to the substrate alkene [12, 13]. The subsequent reduction process of FMN is mediated by NAD(P)H [14].

The classification of ene-reductases encompasses five distinct classes, with the Old Yellow Enzyme representing the most extensively researched category [15]. The initial demonstration of ene-reductase activity dates back to 1932, as documented by Warburg and Christian [16]. It was not until 1995 that EREDs were employed in the synthesis of chiral intermediates. After this pivotal development, numerous instances of ERED applications in biocatalysis have been documented.

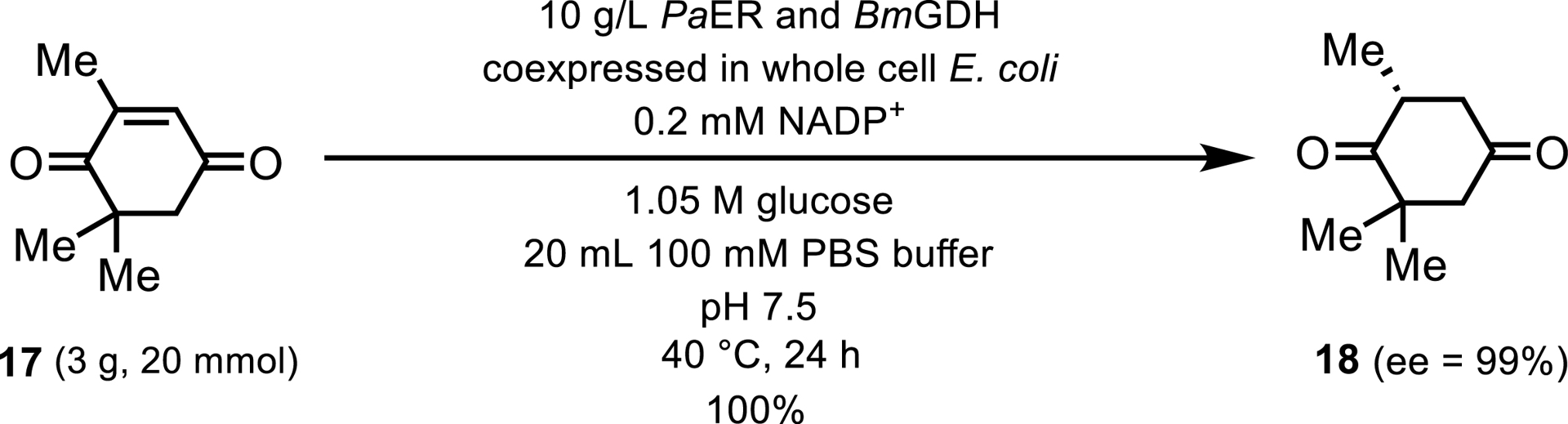

A recent scholarly article detailed the characterization of a novel ERED derived from Pichia angusta (PaER), which exhibited remarkable stereoselectivity in the reduction of ketoisophorone 17 to (R)-levodione 18 as depicted in Scheme 9 [17]. The reaction was conducted with an impressive substrate concentration of 154 g/L, utilizing whole E. coli cells that housed both the ERED and the GDH cofactor recycling enzyme.

Preparative-scale reduction of ketoisophorone.

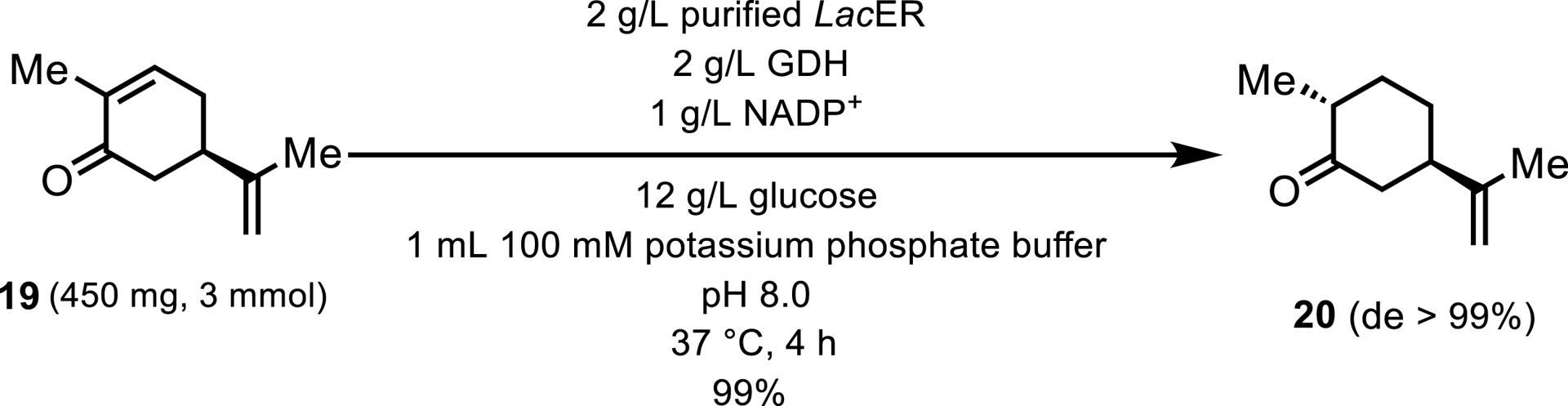

Another example characterized by almost perfect stereoselectivity involves an ERED isolated from Lactobacillus casei (LacER). This ene-reductase was used to catalyze the reduction of (5R)-carvone 19, yielding (2R, 5R)-dihydrocarvone 20 as illustrated in Scheme 10 [18]. The enzyme facilitated the production of this compound with a diastereomeric excess (de) of 99%. Additionally, this ERED demonstrated versatility by functioning in a one-pot cascade reaction alongside a KRED, culminating in the synthesis of (1S, 2R, 5R)-dihydrocarveol.

Analytical-scale reduction of (5R)-carvone.

In instances where the catalytic characteristics of ERED catalysts are deemed suboptimal, enzyme-engineering techniques can be harnessed to enhance the enzymatic properties. A 2015 study demonstrated that enzyme engineering could modify the enantioselectivity of OYE 1 from S. pastorianus through the introduction of a singular W116V mutation [19]. In a separate investigation, a consensus mutagenesis approach was applied to the 12-oxophytodienoate reductase from L. esculentum (tomato) applied to cyclohex-2-en-1-one-based substrates, resulting in an improved enantioselectivity exceeding 99% ee [20]. Furthermore, a rational design strategy was employed to truncate the flexible loops of the nicotinamide-dependent cyclohexenone reductase (NCR), thereby augmenting both the thermal stability and solvent resistance of the ERED [21].

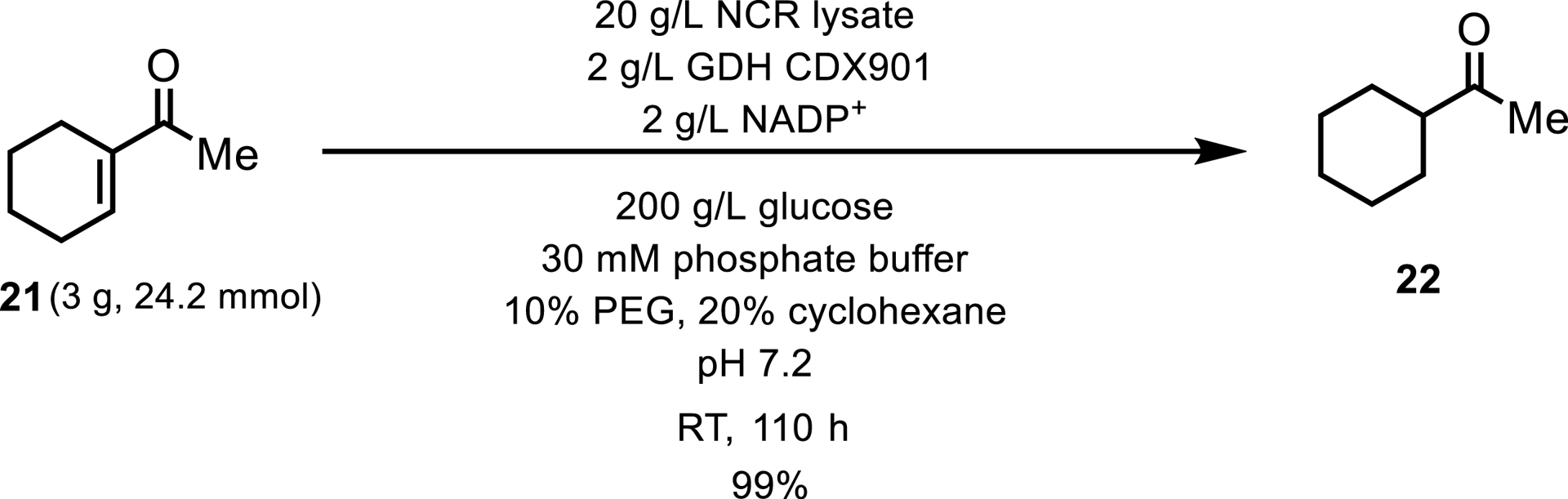

The NCR ERED has also been documented to function effectively at elevated substrate concentrations. For instance, a study focusing on the reduction of 1-(cyclohex-1-en-1-yl)ethan-1-one 21 to 1-cyclohexylethan-1-one 22 reported a substrate loading capacity of 100 g/L, achieving a 99% conversion over a span of 110 h (Scheme 11) [22].

Reduction of 1-(cyclohex-1-en-1-yl)ethanone via NCR.

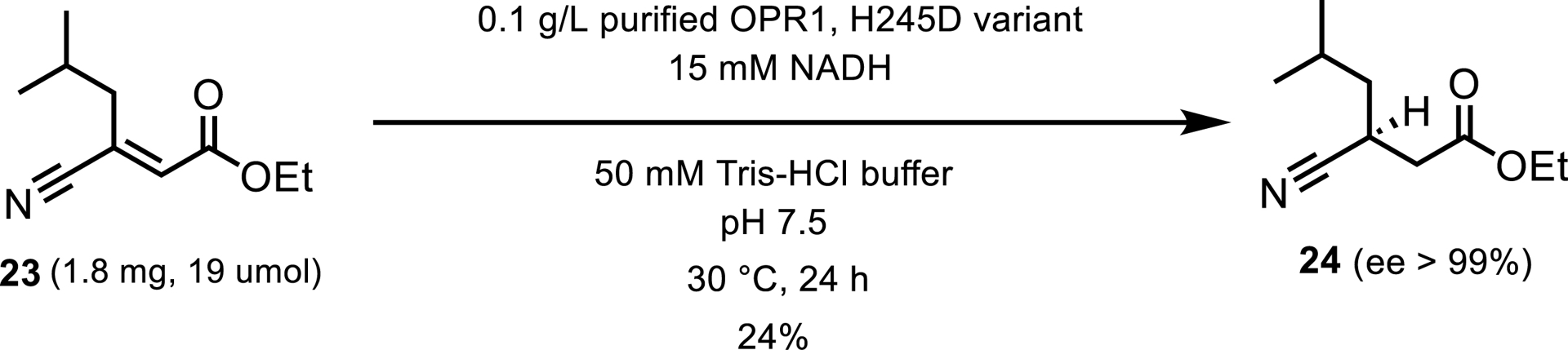

EREDs have been employed in the synthesis of pharmaceutical intermediates, notably in the production of pregabalin, a medication with anticonvulsant, analgesic, and anxiolytic properties for treating neurological conditions. Ethyl (E)-3-cyano-5-methylhex-2-enoate 23 underwent reduction by 12-oxophytodienoate reductase (OPR1) to yield ethyl (S)-3-cyano-5-methylhexanoate 24, as depicted in Scheme 12 [23].

Analytical-scale reduction of a potential intermediate in pregabalin synthesis.

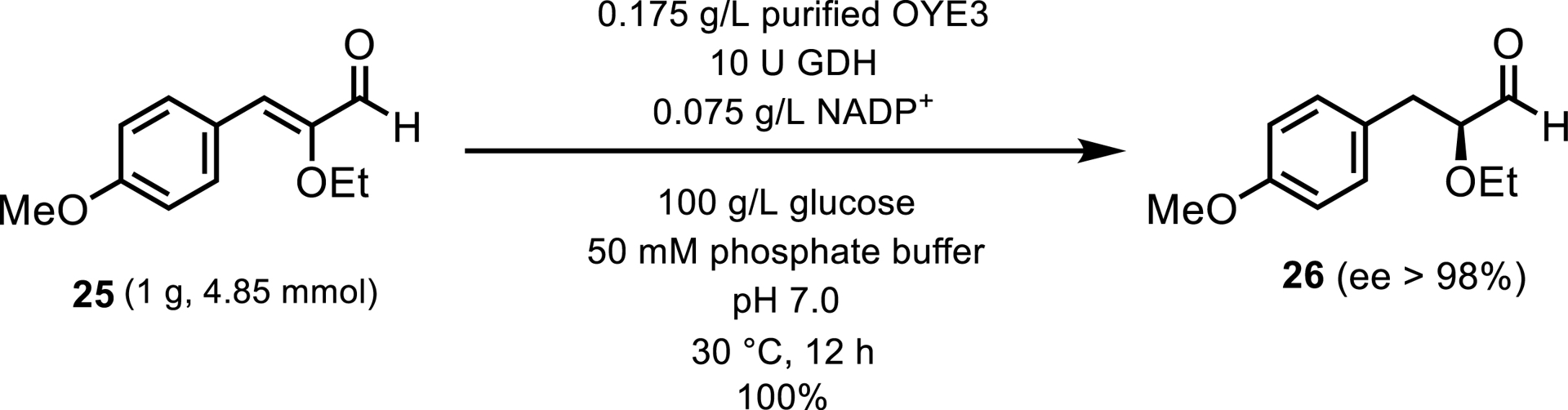

EREDs have also been utilized in the synthesis of intermediates for pharmaceuticals, exemplified by tesaglitazar, a drug under investigation for the treatment of type 2 diabetes [24]. The specific reaction involves the reduction of (Z)-2-ethoxy-3-(4-methoxyphenyl)acrylaldehyde 25 to (S)-2-ethoxy-3-(4-methoxyphenyl)propanoic acid 26, executed with high efficiency and selectivity (100% conversion; 98% ee), employing Old Yellow Enzyme 3 (OYE3) as the biocatalyst (Scheme 13).

Analytical-scale reduction of a potential intermediate in tesaglitazar synthesis.

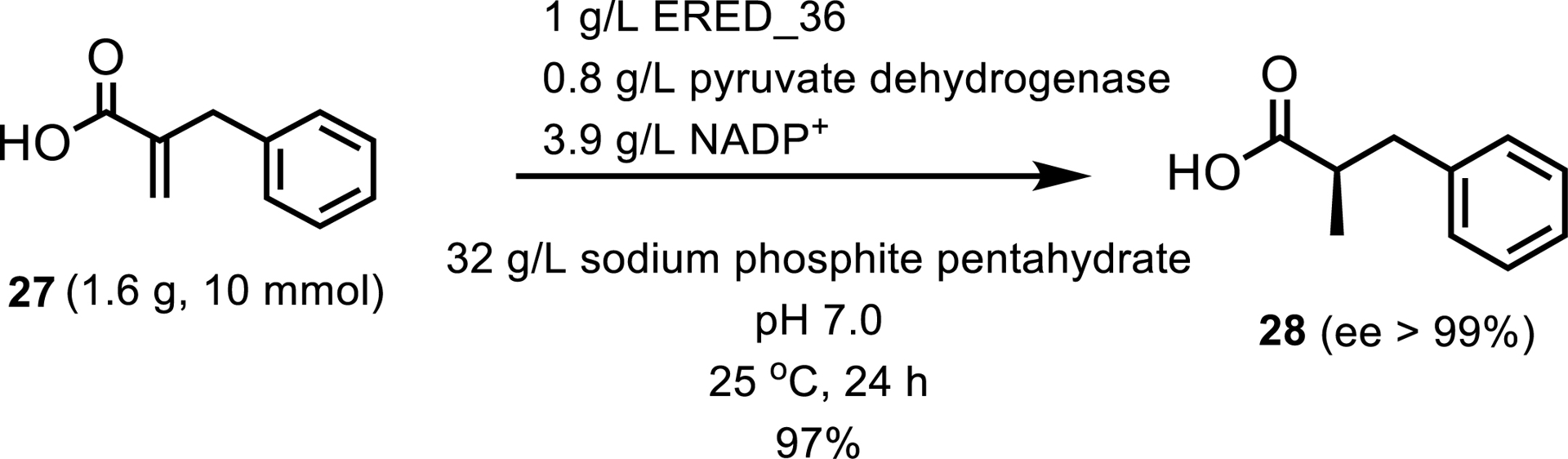

Ene-reductases have also been shown to catalyze reactions that are not limited only to activated olefins. Two recent reports have shown the expansion of the ERED substrate scope. The first report demonstrated that EREDs can reduce several carboxylic acid substrates [25], of which the most successful example involved the stereoselective reduction of 2-benzylacrylic acid 27 (Scheme 14).

Demonstrated ERED reduction of a carboxylic acid substrate.

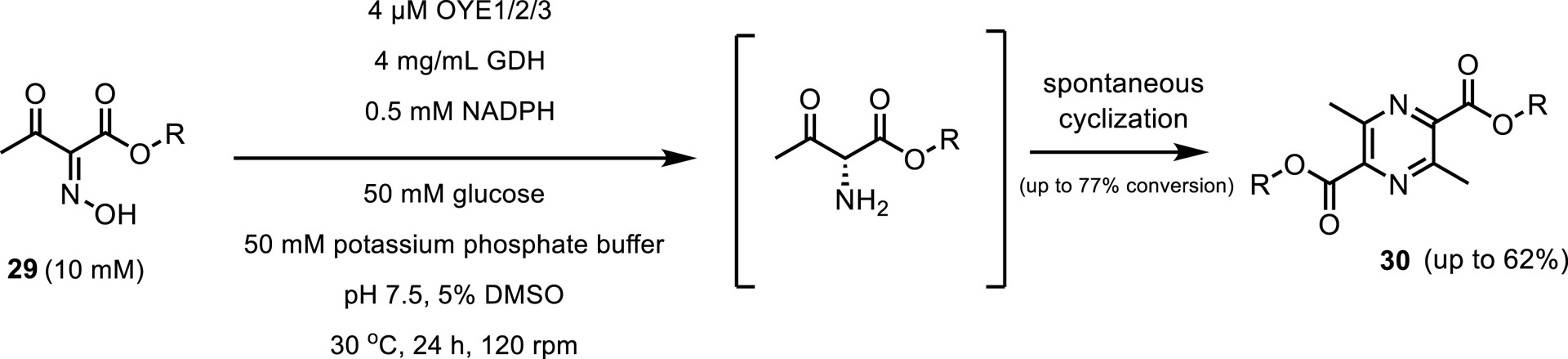

The second report showed a novel feature of EREDs, the reduction of C=N in oximes (Scheme 15) [26]. Several enzymes exhibited this activity with the most notable members being OYEs 1, 2 and 3. In addition, for seven out of the eight oxime substrates tested, EREDs have demonstrated catalysis characterized by an isolated yield greater than 50%, at 10 mM substrate loading.

ERED reduction of C=N bonds in oximes.

Therefore, in recent years, the type of activities that EREDs exhibit have been significantly expanded. We do not see this trend slowing down soon.

4. Imine-reductases (IREDs)

Imine reductases (IREDs) are a class of enzymes commonly used for the formation of secondary and tertiary amines, and less frequently primary amines. As the name suggests, these enzymes catalyze the reduction of imine C=N bonds with a NADPH cofactor. This activity was first shown by Nagasawa and coworkers in 2009 with two enzymes from strains of Streptomyces reducing 2-methyl-1-pyrroline to (R)- or (S)-2-methylpyrrolidine [27]. Further research expanded the panel of known IREDs and showed that these enzymes work well with a range of ketones and imines including cyclic and acyclic, aromatic, and aliphatic ketones [28]. For the amine partner, IREDs prefer smaller amines such as methyl, allyl, and cyclopropyl amines. Couplings with ammonia, however, can be difficult. Regardless, larger amines like benzylamine and isoindoline [29] have been reported to be accepted. A recent report even showed a successful coupling of an aldehyde with α-(1-aminoethyl)naphthalene [30].

Being NADPH-dependent, IREDs are typically used in tandem with an NADPH recycling system. Many of these are the same systems used in KRED reactions. The most used system is the glucose-dehydrogenase (GDH)-catalyzed oxidation of glucose to gluconic acid. As the glucose oxidation step is non-reversible, this imparts a driving force on the imine reduction step. Other recycling systems have been reported such as alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) oxidation of alcohols to carbonyls (typically propan-2-ol to acetone) [31, 32], soluble hydrogenase (SH) reduction of NADP+ with hydrogen gas [33], phosphite dehydrogenase (PTDH) oxidation of phosphite to phosphate [34], and formate dehydrogenase (FDH) oxidation of formic acid to carbon dioxide [35]. While these systems are very attractive from an atom economy standpoint, glucose oxidation remains the most commonly used in industry.

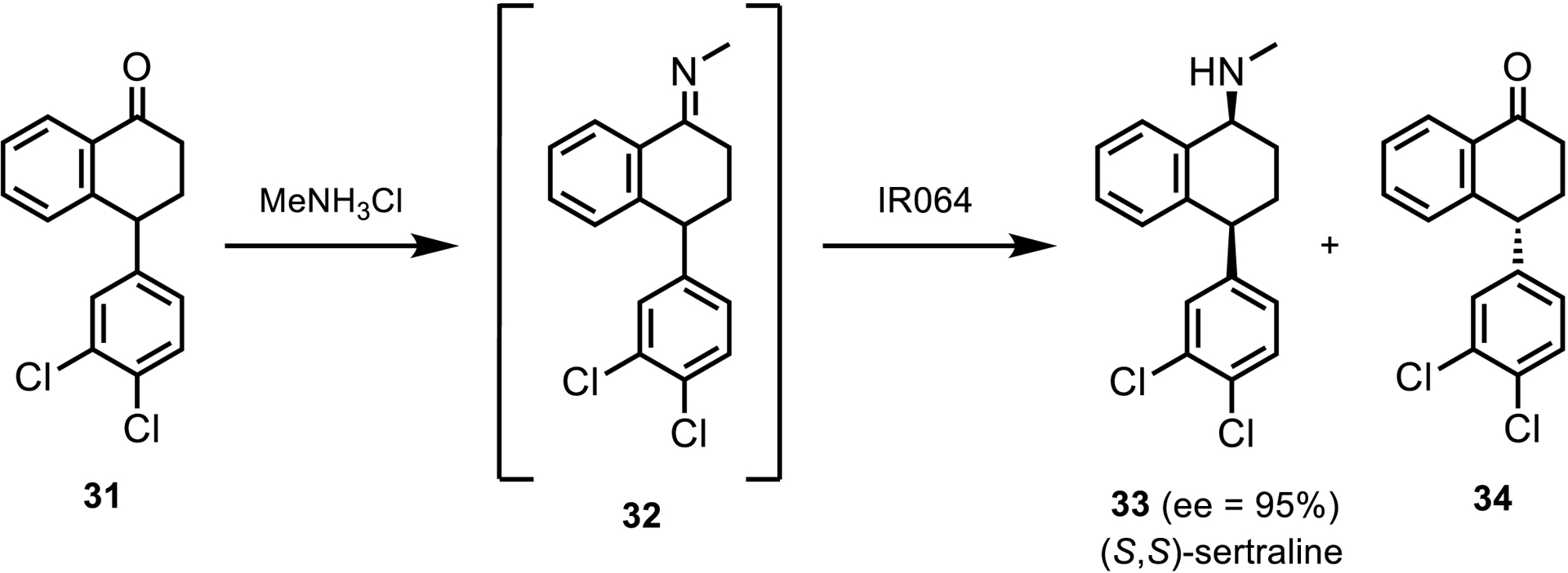

In 2017, Pfizer gave a brief report of an IRED-catalyzed reduction to synthesize (S,S)-sertraline [36]. Since the aryl ketimine 32 did not form spontaneously, the team synthesized the imine by chemical means and fed it into the IRED reduction. Via this route, IR064 from Myxococcus fulvus was identified as a hit for the reduction with the desired selectivity at both chiral centers and 95% ee (Scheme 16). Enzyme engineering efforts focused on IR064 allowed the team to identify variants with improved activity and selectivity. One variant with 5 mutations gave a 2.3-fold improvement in activity with 95% ee [36].

Telescoped condensation and reduction toward the synthesis of (S,S)-sertraline.

In the same year, Aleku and coworkers reported a new IRED from Aspergillus oryzae which, in addition to reducing imines, also catalyzed the condensation of a ketone and amine to form the imine for reduction [37]. This subset of IREDs has been dubbed reductive aminases or RedAms, and following their discovery, a mechanism of enzymatic reductive amination was proposed [38]. Since then, several articles reporting the use of RedAms to produce various amines have been published, and additional IREDs that show this activity have been discovered.

The first of these reports came in 2019 from GSK showing the use of an IRED from Saccharothrix espanaensis (IR-46) to resolve trans-phenylcyclopropylamine 35 and use it in the reductive amination of an aldehyde (Scheme 17) [39]. After three rounds of enzyme engineering, Schober and coworkers reported that they were able to run the reaction at 20.1 g/L aldehyde 35 with 1.2 wt% enzyme loading to reach 84% isolated yield of the desired product amine obtained with 99.7% ee. They noted that, although IREDs are typically most active at neutral to slightly basic pH, a slightly acidic pH was needed for product and substrate stability, and product solubility.

Pilot-scale reductive amination toward the synthesis of GSK2879552.

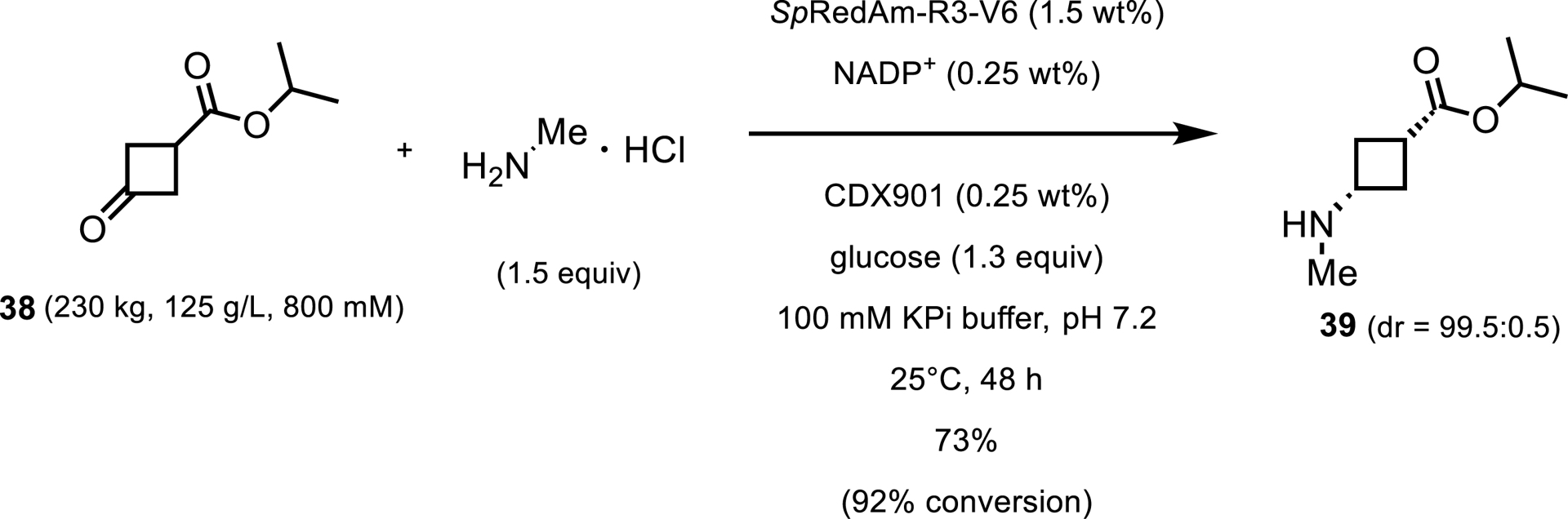

A few years later, Pfizer reported using an IRED from Streptomyces purpureus (SpRedAm) to couple isopropyl 3-ketocyclobutylcarboxylate 38 with methylamine for the production of an intermediate in the synthesis of abrocitinib [40]. The wild-type enzyme (40 wt%) was able to convert 20 g/L of ketone with 2 equiv of methylamine to give the desired product in 27% isolated yield. The engineered enzyme (SpRedAm-R3-V6) was used in this reaction at 230 kg scale with 125 g/L ketone and 1.5 wt% enzyme. Reaction performance under these conditions improved to 92% assay yield with 73% isolated yield and 99.5:0.5 dr (Scheme 18).

Preparative-scale reductive amination toward the synthesis of abrocitinib.

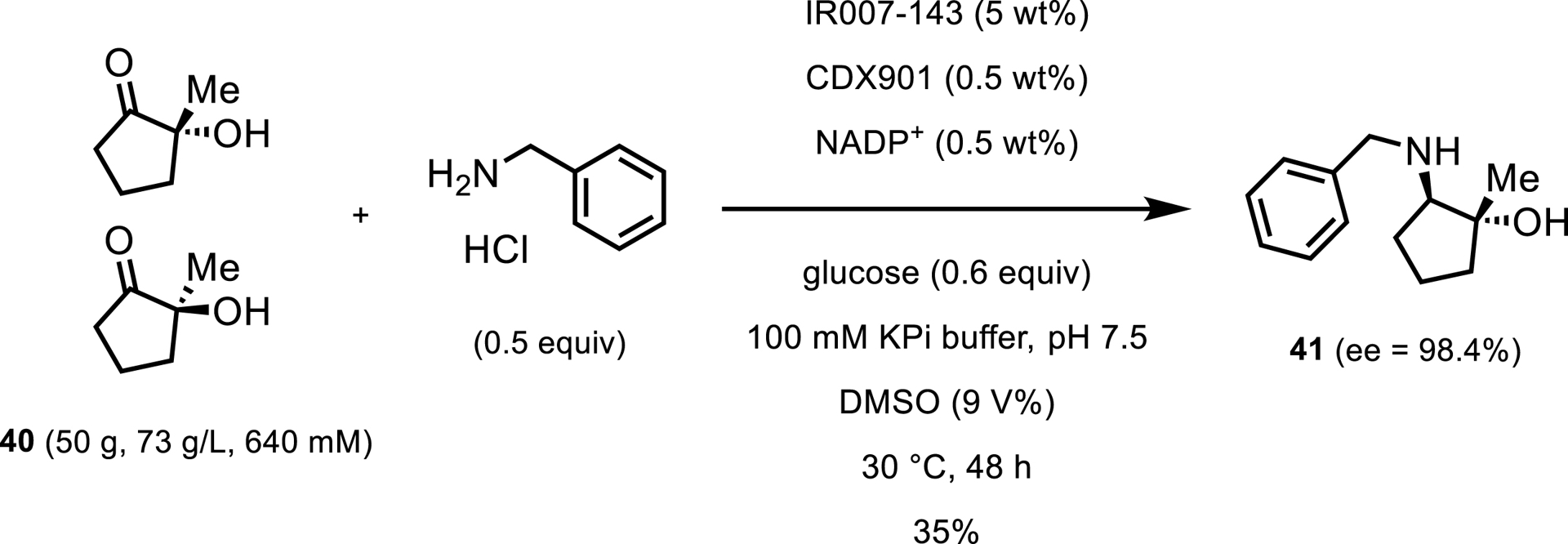

Another report from Pfizer showed the use of a larger amine in a resolution and reductive amination of hydroxyketone 40 [41]. As part of a synthesis toward an investigatory CDK2/4/6 inhibitor, the team identified an IRED from Amycolatopsis azurea, dubbed IR007, which resolved the racemic hydroxyketone via reductive amination with benzylamine as the donor to produce the desired amine as a single stereoisomer. After engineering IR007 for improved activity and stability, variant IR007-143 was identified, which resolved the ketone with only 2.5 wt% catalyst loading to give 35% isolated yield and 98.4% ee after 48 h (Scheme 19). This process was developed as an alternative to a transaminase-catalyzed reaction discussed in a later section of this review. With higher chiral purity and easier product isolation, this IRED approach was selected to move forward.

Preparative-scale reductive amination with IR007-143.

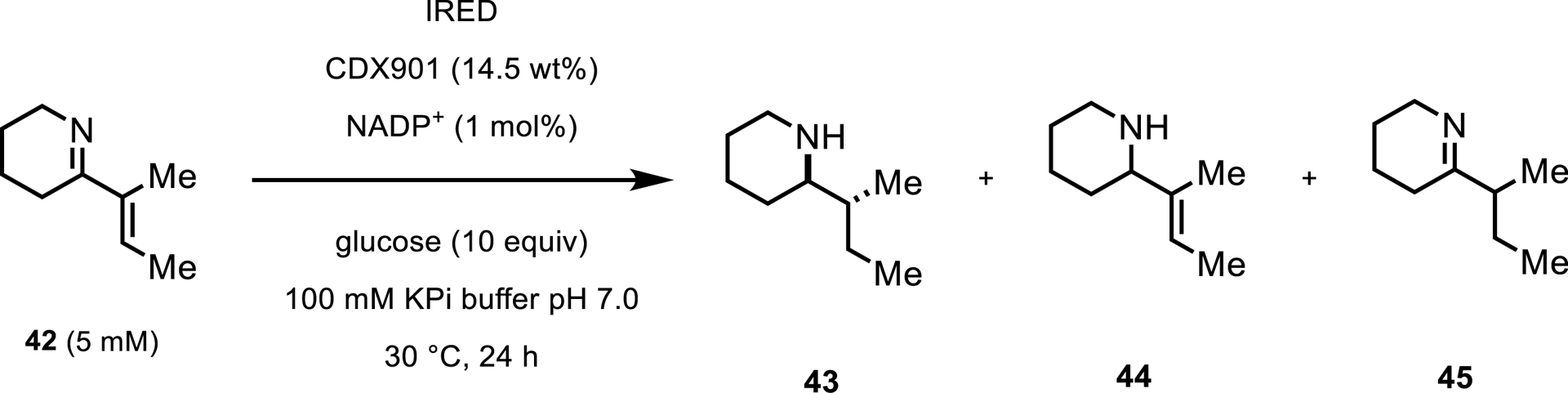

Most recently, Thorpe and coworkers have reported a new type of activity from IREDs. In 2022, the group showed the use of an IRED with α,β-unsaturated imines to reduce not only the C=N bond but also the C=C bond [42]. From a screen of 389 IREDs, 44 enzymes were identified which reduced the ene–imine to the fully saturated piperidine 43 (Scheme 20).

Analytical-scale screening for Ene-IRED reactivity.

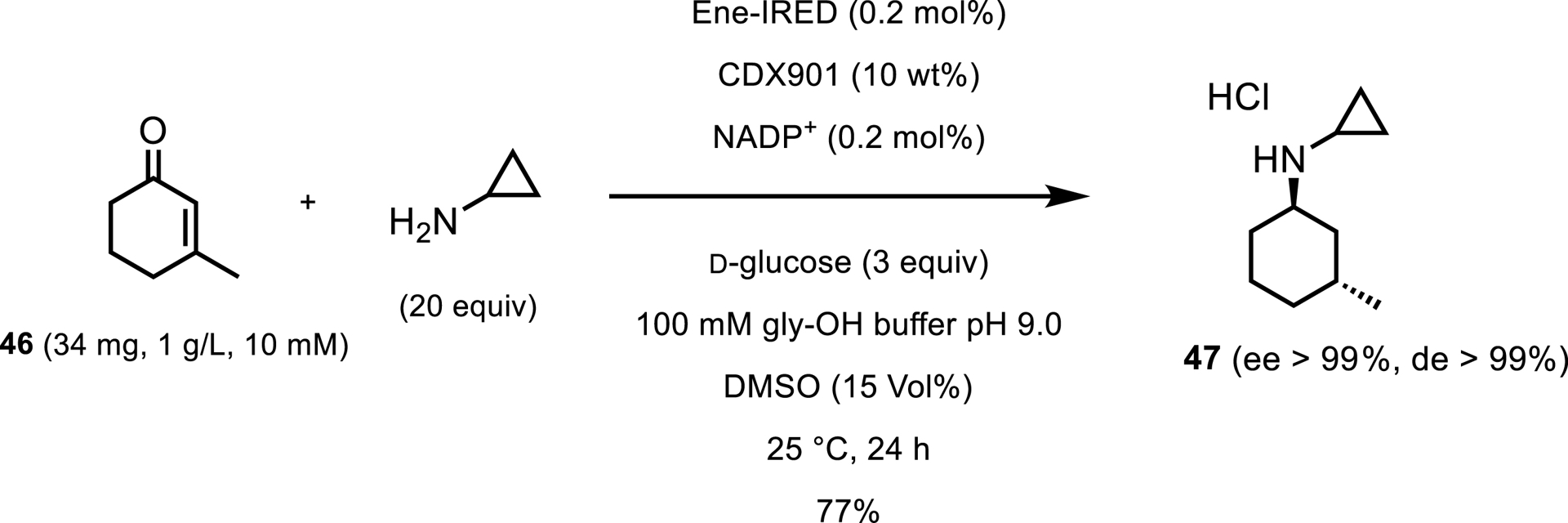

An additional 12 IREDs were identified that gave the reduction of only the C=C double bond resulting in 45. The enzyme with the highest activity for the full reduction was dubbed EneIRED and was selected for further study. After reaction optimization, EneIRED was able to catalyze the condensation and reduction of methylcyclohexenone 46 and cyclopropylamine to 61% conversion with only 1.1 equiv of amine (Scheme 21). When the reaction was performed with 20 equiv, the final product was isolated as the chlorhydrate salt in 69% yield. To test the scalability of the new reaction, the condensation/reduction of 3-methylcyclohex-2-en-1-one and cyclopropylamine was run at mmol scale with 50 mM enone and 5 equiv of amine. The desired product of this reaction was isolated in 77% yield.

Analytical-scale screening for Ene-IRED reactivity.

5. Transaminases

Another class of enzymes for amination are transaminases. These enzymes are used to synthesize primary amines from a ketone or aldehyde using a pyridoxal phosphate (PLP) cofactor and a sacrificial amine donor such as isopropylamine. This is achieved via a two-step mechanism where the amine donor is deaminated by the PLP cofactor to form a ketone and pyridoxamine (PMP). An amination step then transfers the amine group on to the target carbonyl, reforming PLP in the process. During this reaction, the enzyme can preferentially form one epimer of the amino compound. In cases where the starting carbonyl compound has additional stereogenic centers, the transaminase may also show preference for one of the starting material stereoisomers and set both chiral centers of the product in a single reaction. α-Transaminases are limited to the formation of α-amino and α-keto acids whilst ω-transaminases exhibit a much wider substrate scope and are employed much more widely for biocatalysis.

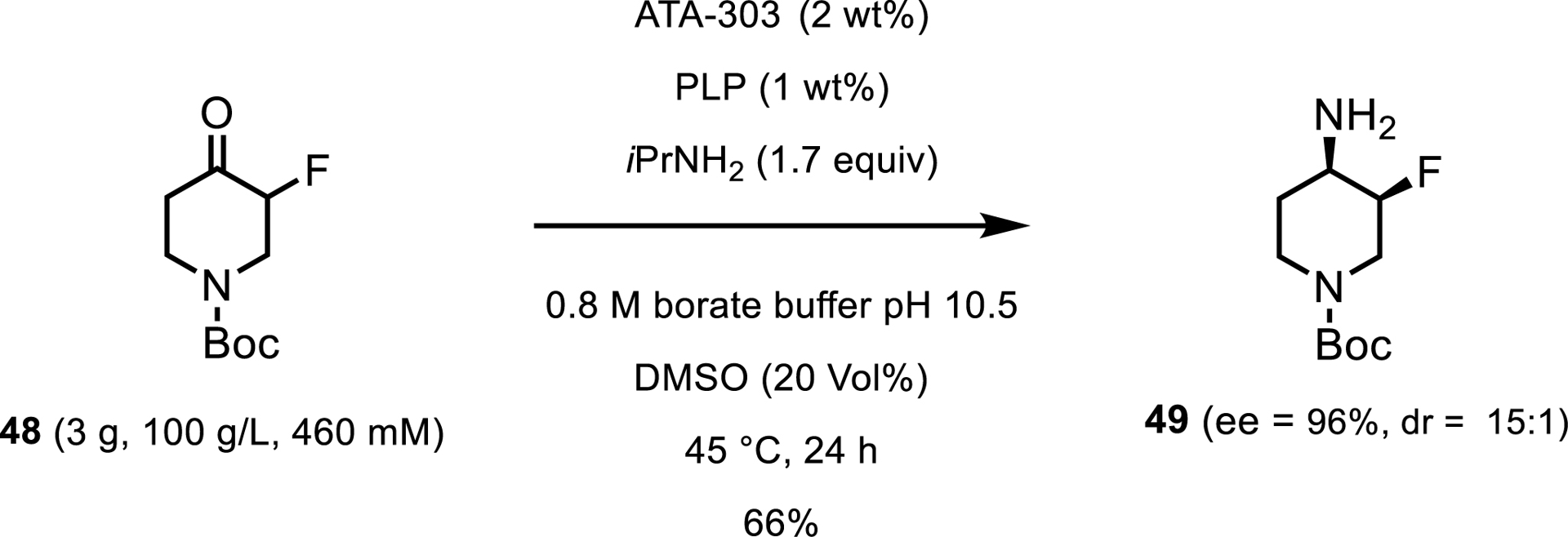

In 2019, the biocatalysis team at Merck reported the use of a transaminase for the synthesis of an intermediate for a CGRP receptor antagonist, 4-amino-N-Boc-3-fluoropiperidine 49 [43]. Starting from the racemic fluoroketone 48 and screening at pH 10.5 to promote epimerization of the chiral fluoride center, the team identified ATA-303 from Codexis as a hit for the desired product stereoisomer. Under initial screening conditions, the ATA-303 gave the desired isomer with 79% ee and 16:1 dr (Scheme 22). Without any enzyme engineering, the process was intensified to 100 g/L ketone and 2 wt% enzyme. This process resulted in 66% isolated yield, with 94% ee and 15:1 dr.

Preparative-scale synthesis of a chiral building block.

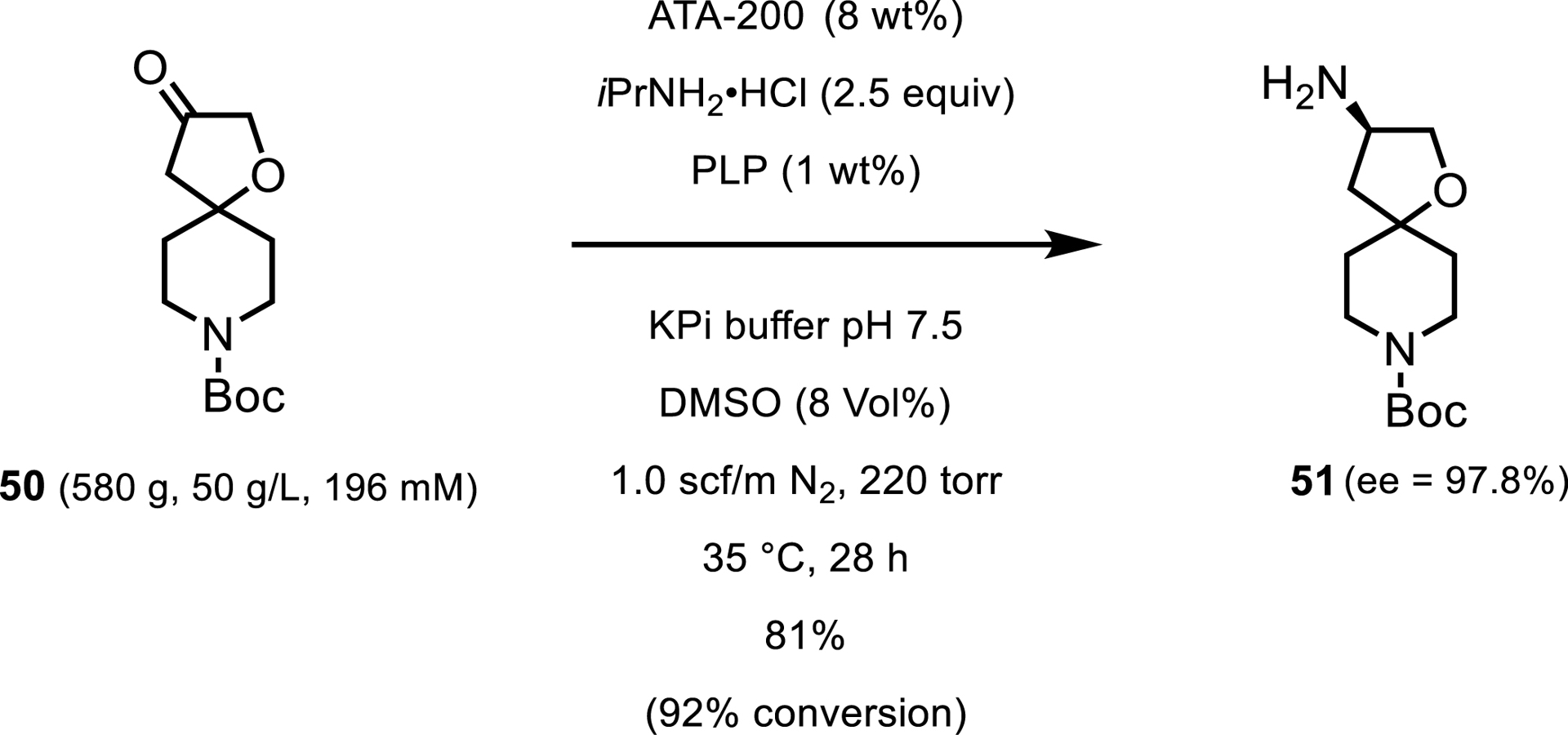

One obstacle commonly encountered with transaminases is the fact that these reactions are controlled by the reaction equilibrium and require a large excess of amine donor to push the reaction forward. Fortunately, several methods have been developed to introduce a thermodynamic or entropic driving force into the reaction. With isopropylamine as the amine donor, the reaction can be pushed to completion by removing the acetone by-product with a constant nitrogen sweep, or by applying a slight vacuum. A report from Pfizer in 2021 showed the use of another commercial transaminase (ATA-200) in the synthesis of 3-amino-4′-Boc-spiro[oxolane-2,4′-piperidine] 51 [44]. In this process, the spiroketone was converted to the amine using 2.5 equiv of IPA and applying a constant nitrogen sweep with periodic vacuum at 220 torr. As in the previous example, no enzyme engineering was needed, and the process was successfully implemented at 50 g/L ketone and 8 wt% enzyme. The optimized conditions resulted in the reaction where the desired amine was isolated with 82% yield and 98% ee (Scheme 23). Additionally, the enzymatic synthesis enabled the formation of 51 as a single enantiomer, avoiding the use of hazardous reagents such as bromine, sodium azide, and triphenylphosphine.

Pilot-scale synthesis of chiral amine.

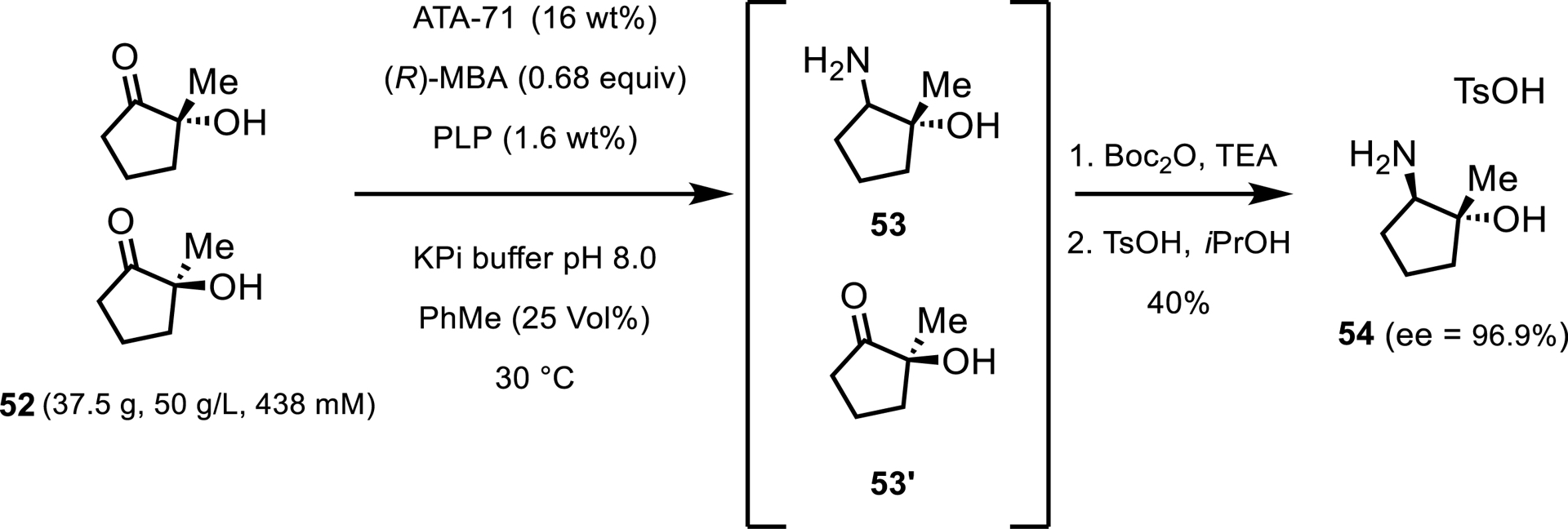

Alternatively, when methylbenzylamine (MBA) is used as the amine donor, evaporation of the by-product can be replaced by removal extraction. In 2022 [41], a report showcased this in a transamination/resolution of hydroxyketone 52 (Scheme 24). In this report, the authors explain that while isopropylamine was initially used for development, it led to an unfavorable reaction equilibrium causing the reaction to stall at low conversion. Applying the nitrogen sweep helped increase conversion but also caused significant solvent loss and deactivation of the enzyme. To remedy this, the team used (R)-MBA instead, as using this donor imparted a more favorable equilibrium. One caveat to this is that the formation of acetophenone can be detrimental to the enzyme at higher concentrations. To account for this phenomenon, the reaction was run as a biphasic mixture with 25 vol% toluene to remove the acetophenone as it is formed. These conditions allowed the reaction of 50 g/L ketone and 16 wt% enzyme load to reach 40% yield over 3 steps with a very favorable 97% ee.

Preparative-scale transamination with ATA-71 and (R)-MBA.

It should be noted that when using a chiral amine donor (e.g., methylbenzylamine, alanine, etc.) it is important to use the correct enantiomer. Typically, this is the isomer with the same chirality as the desired product (e.g., (R)-MBA was used in this example to generate the (R)-amine).

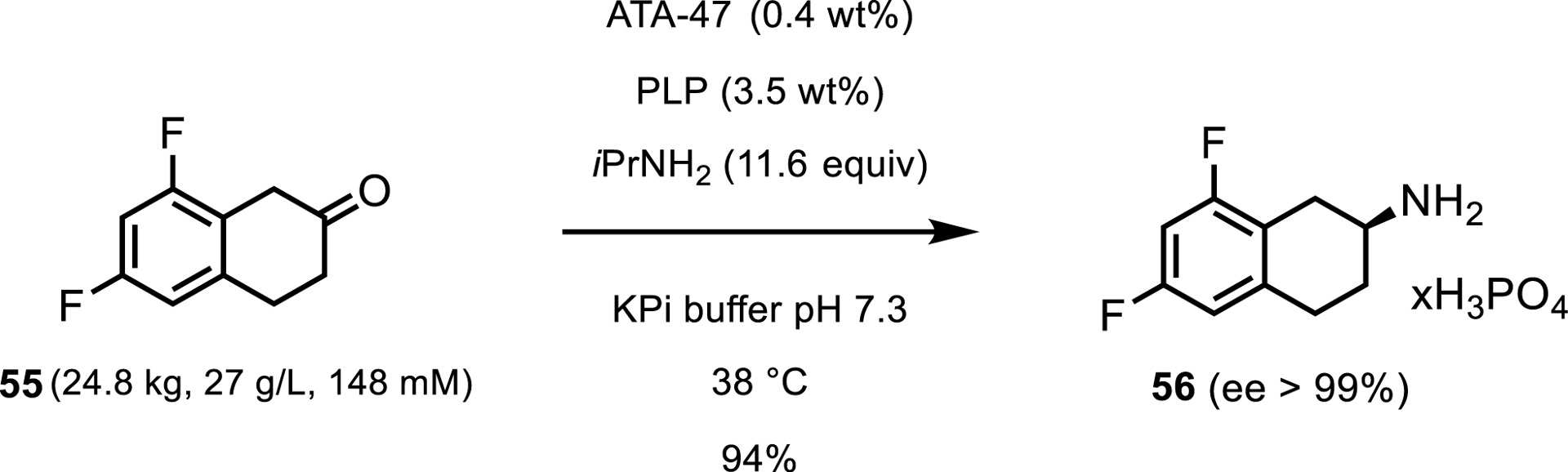

A less common method of driving the transaminase equilibrium forward is by removing the desired product from the reaction mixture as it is formed. A 2017 report showcases the synthesis of 2-amino-6,8-difluorotetralin 56 [45]. The Pfizer biocatalysis group showed that using ATA-47 from c-LEcta GmbH enabled the conversion of 6,8-difluoro-beta-tetralone 55 to the desired (S)-amine in 94% yield (Scheme 25). More importantly, they reported that due to low solubility of starting material and product, the product precipitated in the form of phosphoric acid salt as it was formed.

Industrial-scale transamination with ATA-47.

Other transaminase reactions involve the removal of pyruvate (formed from alanine) that can be achieved using lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) or pyruvate decarboxylase (PDC). A downside to using LDH is that it requires a NADPH recycling system to continue removing pyruvate. On the other hand, PDC yields acetaldehyde and carbon dioxide that can be removed by vacuum or a nitrogen stream due to their volatility [46].

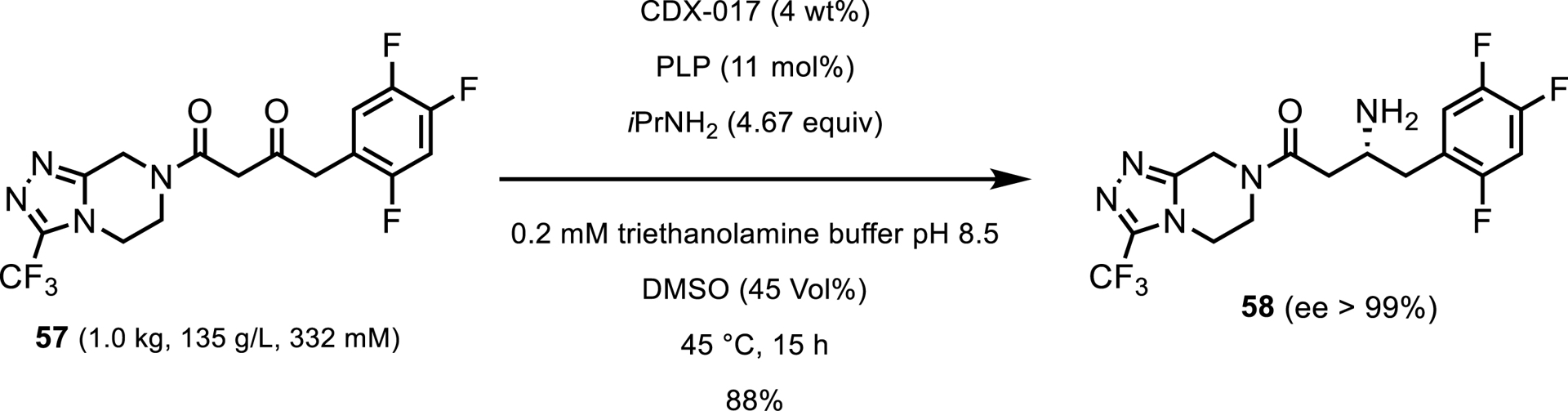

Another obstacle with transaminase processes is that they are typically limited to aldehydes or small ketones (e.g., methylo, cyclic ketones). However, a large area of transaminase research has focused on expanding the binding pocket of transaminases to accommodate larger substrates. Several groups have reported successfully expanding the active site of a transaminase to accommodate carbonyls as large as phenyl tert-butyl ketone [47]. In fact, in 2010, Codexis and Merck reported a transaminase that after only one round of engineering, was able to transaminate pro-sitagliptin ketone 57 (Scheme 26) [48]. This variant achieved less than 1% conversion with high enzyme load; however, this was a huge improvement considering the lack of any hits in the initial screen. After several additional rounds of enzyme and process engineering, the team was able to develop an enzyme which converted the target ketone in 88% assay yield at 134 g/L with only 4 wt% enzyme.

Transamination of the bulky pro-sitagliptin ketone.

6. Cytochrome P450

Cytochrome P450 monooxygenases (P450s or CYPs) are heme enzymes which perform oxidations with molecular oxygen and often with the aid of NADPH cofactor and a redox partner protein [49, 50]. P450s perform a diverse range of functionalizations from oxidation of heteroatoms, to C–C bond formation or cleavage, to aromatic hydroxylation of aromatic compounds. However, they are most often used to achieve the hydroxylation of sp3 C–H bonds. The ability to stereo- and regioselectively activate a previously inactivated C–H has been captivating due to the ability of P450s to eliminate the need for multistep synthetic processes. P450s do come with many limitations such as low stability, limited substrate scope and low activity, which have prevented them from replacing these synthetic steps on a larger scale. Engineering has been applied to combat these limitations, often with P450-BM3 from Bacillus megaterium as the starting point for these enzyme-modifying methods [51].

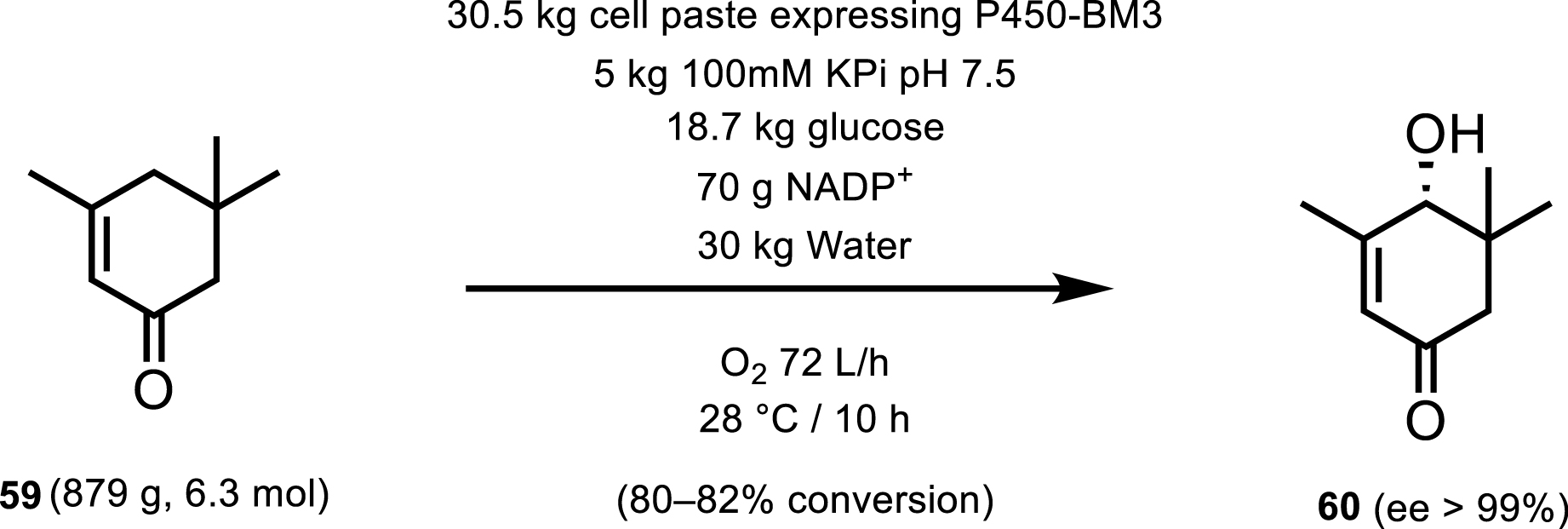

An example of P450-BM3 reaching a kilogram scale production was demonstrated by Kaluzna et al. [52] where they synthesized 4-hydroxy-α-isophorone 60 from α-isophorone 59. At a 1 L scale, Kaluzna et al. were able to obtain unprecedented product concentration of 10 g/L and a space time yield of 1.5 g/L/h (Scheme 27). Upon extensive reaction engineering, the process was scaled up to a 100 L scale, however the authors noted that at this scale, the reaction was restricted by the oxygen transfer rate (OTR) and by self-deactivation of the enzyme.

100 kg scale hydroxylation of a-isophorone by P450-BM3.

To overcome some of the restrictions of P450s, fusion enzymes have been designed. Many families of P450s require a reductase partner enzyme for NADPH binding. An electron is transferred from the reductase partner to the P450 heme domain, allowing the desired oxidation reaction to proceed with the target substrate. In a so-called self-sufficient P450, the reductase domain is already fused to the heme domain, however nonnatural self-sufficient P450s have also been developed to improve the catalytic efficiency [53].

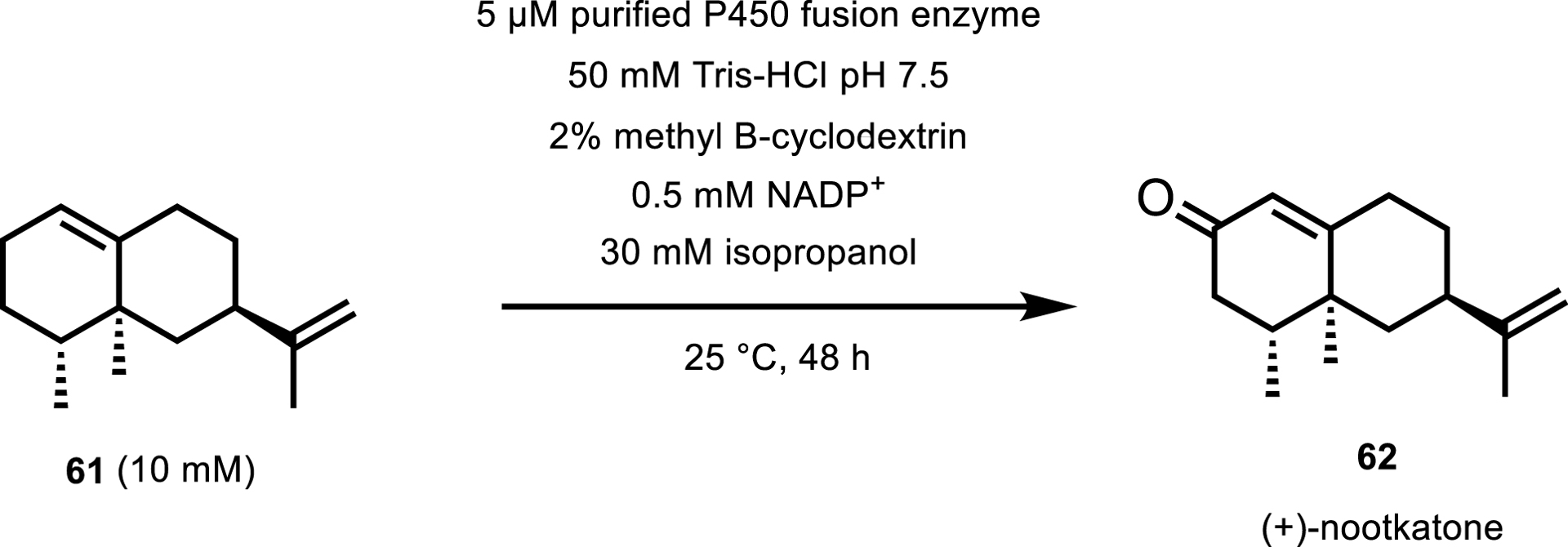

This has also been taken a step further, by Kokorin et al. [54], where a dehydrogenase enzyme has been fused to a self-sufficient P450 to eliminate the need for a separate cofactor recycling enzyme, resulting in an increase of activity and catalytic efficiency. Kokorin and Urlacher [55] then expanded on this work by applying a fusion enzyme to the two-step oxidation of the insecticide and food additive (+)-nootkatone 62 from (+)-valencene 61 with 1.5 times increase in activity compared to the individual enzymes (Scheme 28).

Two-step oxidation of (+)-valencene to (+)-nootkatone.

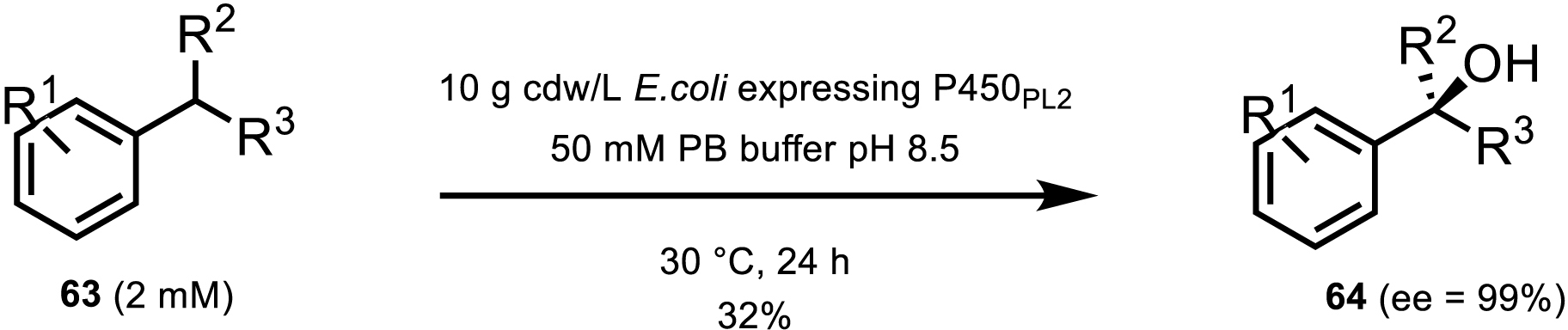

Although P450s are often considered to have narrow substrate scopes, Zhang et al. [56] have demonstrated that hydroxylation at a tertiary carbon position is possible with P450s. Tertiary hydroxylation is synthetically often difficult to achieve on inactivated C–H bonds and even more difficult to achieve in high enantiomeric excess. Zhang et al. engineered P450-BM3 variant P450PL2 to reach up to 99% ee and 32% yield upon α-hydroxylation of a benzylic C–H bond with a range of substituted substrates (Scheme 29).

Tertiary hydroxylation of benzylic CH by P450-BM3 variant P450PL2.

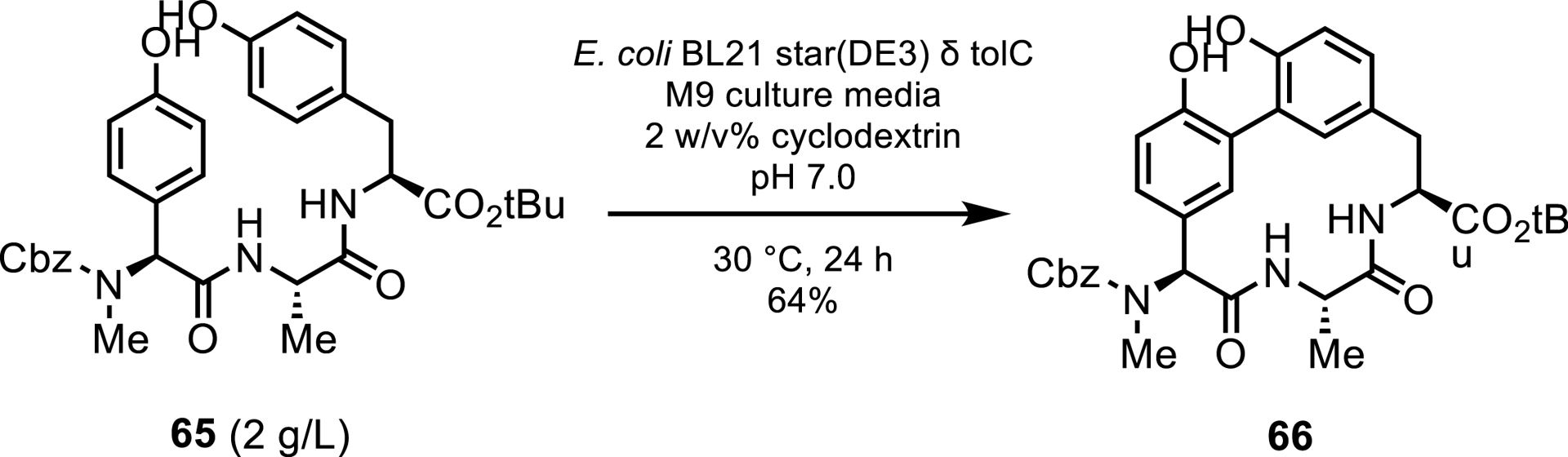

Aside from hydroxylations, alternative functionalizations by P450s are being explored on process scales. A recent report by Genentech has demonstrated that engineered P450s are a viable replacement for Suzuki–Miyaura couplings on a gram scale by performing an oxidative biaryl macrocyclization to produce an arylomycin antibiotic core 66. Molinaro et al. [57] obtained 1.3 g of product in 64% yield from a 3 L fermentation process after purification (Scheme 30).

P450-catalyzed biaryl coupling of arylomycin.

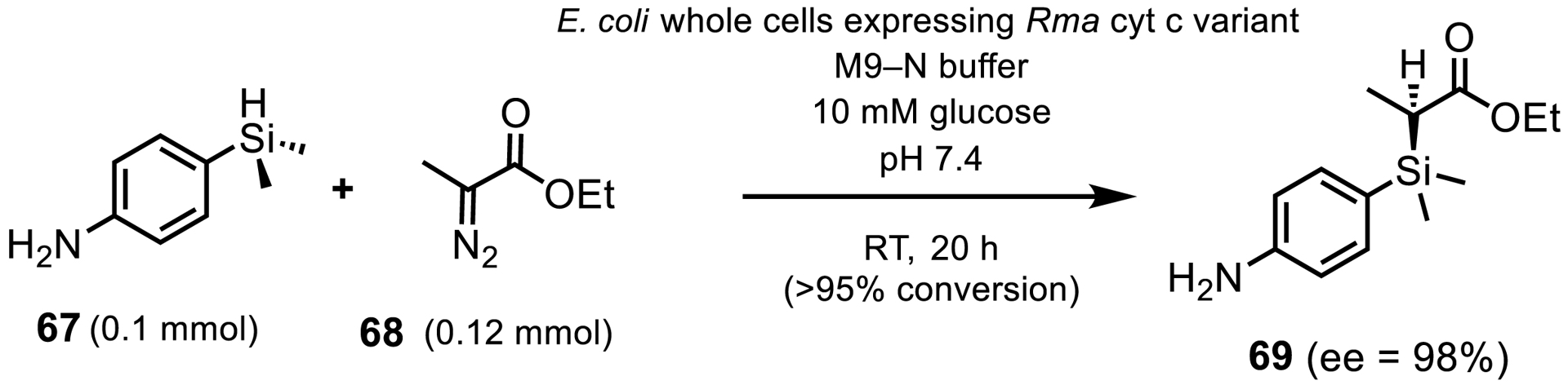

Bond connections that do not occur in natural biological processes have also been performed by P450s. Inspired by P450’s non-natural carbene transfers with N–H and S–H insertions to form C–N or C–S bonds [58, 59], Kan et al. [60] proposed that a similar method could be achieved with Si–H insertions to form carbon–silicon bonds. As C–Si bonds are present in a diversity of compounds which include materials and pharmaceutical compounds, upon engineering cytochrome c from Rhodothermus marinus (Rma cyt c), Kan et al. were able to stereoselectively insert a C–Si bond into 4-(dimethylsilyl)aniline 67. Moreover, Rma cyt c was engineered to chemoselectively form the C–Si bond despite the presence of a competing nitrogen atom in the molecule. Preparative-scale reactions with whole cells resulted in over 95% conversion and a 70% isolated yield with 98% ee and a total turnover number (TTN) of 3410 (Scheme 31).

Chemo- and stereoselective carbene Si–H insertion of to 4-(dimethylsilyl)aniline.

7. Iron/α-ketoglutarate-dependent oxygenases

Like P450s, iron/α-ketoglutarate-dependent oxygenases or iron/2-oxoglutarate-dependent oxygenases (Fe/αKGs or 2ODs) are iron-coordinating enzymes which perform oxidations with molecular oxygen. However, unlike P450s, Fe/αKGs are non-heme iron-binding enzymes and instead recruit an α-ketoglutarate (αKG) cofactor which coordinates to the iron via a catalytic triad and assists in electron transfer to the substrate of interest. Fe/αKGs, first discovered in the 1960s [61], have many important roles in biological processes, both in humans and many other organisms [62]. As such, Fe/αKGs can perform a diverse range of C–H functionalizations, but biocatalytic applications are often focused on their halogenation or hydroxylation capabilities.

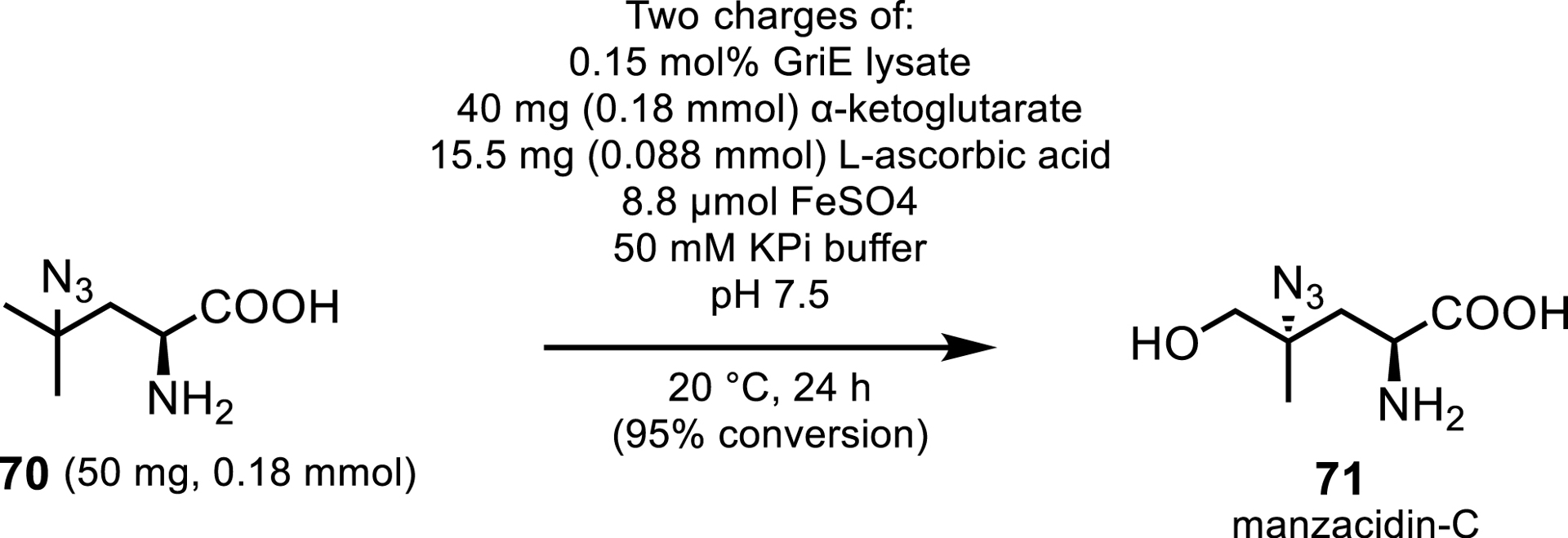

One such enzyme, is the putative leucine hydroxylase GriE, which performs sequential oxidations at the delta position of L-leucine, forming 4-methylproline by cyclization via a spontaneous reductive amination in the biosynthesis of griselimycin [63]. Zwick and Renata [64, 65], report a proof of concept where they employ GriE as the first Fe/αKG to be used in a natural product synthesis. They share that GriE can produce an array of substituted pyrrolidine building blocks and also demonstrate the utility of the enzymes in natural product synthesis by performing the chemoenzymatic preparation of manzacidin-C (Scheme 32), a bromopyrrole alkaloid first isolated from sea sponge Hymeniacidon sp. [66] Zwick and Renata reported a photocatalytic azidation to L-leucine which is followed by a single Δ hydroxylation by GriE, creating the hydroxylated product intermediate with a yield of 95% on a 130 mg scale.

Hydroxylation by GriE of an intermediate in the chemoenzymatic synthesis of manzacidin-C.

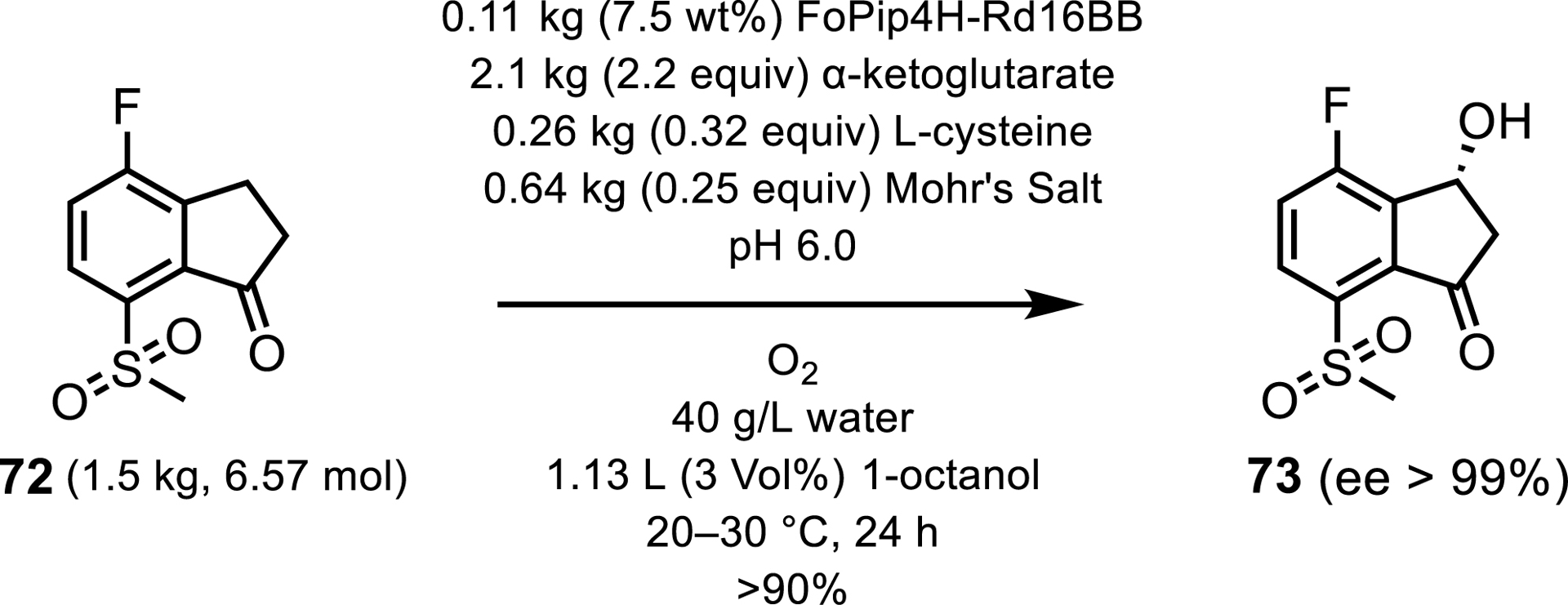

Most recently, the industrial potential of Fe/αKG hydroxylases has been used by scientists at Merck who have incorporated an Fe/αKG into the synthesis of the oncology treatment belzutifan, by performing a stereoselective hydroxylation on a non-native fluoroindanone intermediate 72 [67, 68, 69]. This biocatalytic step replaced five chemical synthesis steps reducing the process mass intensity (PMI) by 43%, again illustrating the environmental advantages to employing biocatalysts in industry. Cheung-Lee et al. [67] reported that, despite a P450 reaching higher conversions in their initial screens, a Fe/αKG hydroxylase, FoPip4H from Fusarium oxysporum, was selected for further development in this process due to the resulting economic and time benefits. After 15 rounds of directed evolution, FoPip4H Rd16BB showed a 3000-fold improvement in catalytic efficiency over the wild type. Furthermore, DiRocco et al. [68] stated that an overall improvement of more than 400,000-fold was observed in comparison to the wild type when enzyme loading, reaction concentration, yield, and enantioselectivity were achieved. At kilogram scale, the final variant exhibited yields and ee of more than 90% and than 99%, respectively (Scheme 33).

Hydroxylation of a fluoroindanone intermediate in the synthesis of belzutifan.

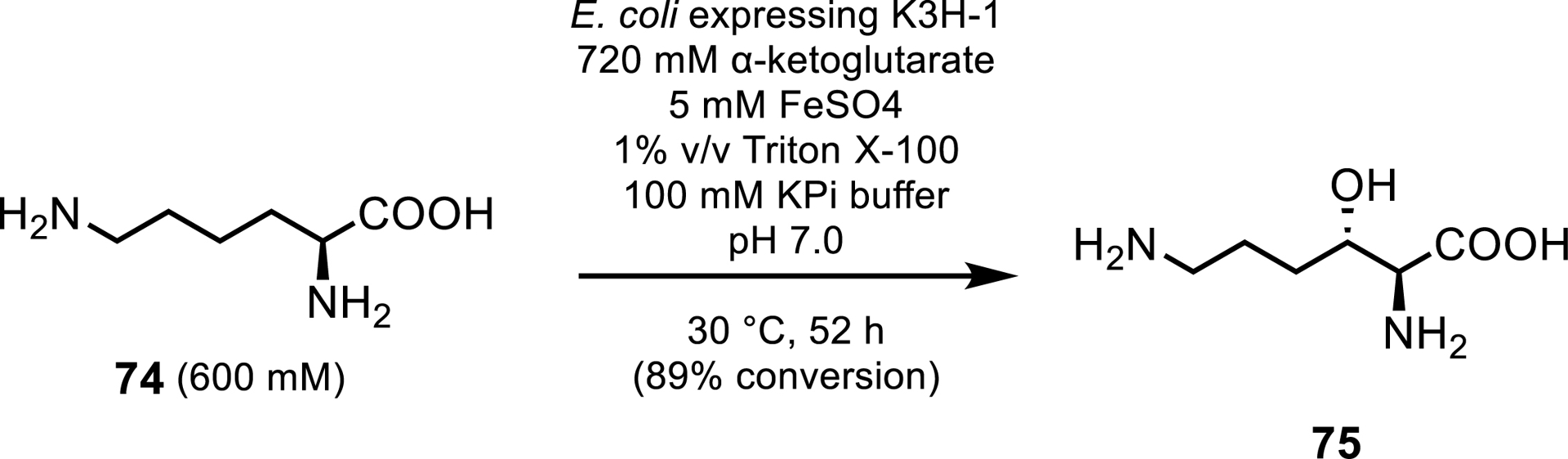

Another scaled up application of Fe/αKGs was demonstrated by Hara et al. [70]. They reported the preparative-scale synthesis of (2S,3S)-3-hydroxylysine 75, among other hydroxylysines, which can be an intermediate in the synthesis of (−)-balanol, a protein kinase C inhibitor. The lysine hydroxylases tested in this study were identified by sequence analysis of the clavaminic acid synthase superfamily with K3H-1 showing the greatest productivity. High substrate loadings were achieved of up to 600 mM lysine, and after 52 h, a 40 mL reaction yielded 531 mM (86.1 g/L) of (2S,3S)-3-hydroxylysine, with 89% molar conversion from whole cells expressing K3H-1 (Scheme 34). The authors did not report the diastereoselectivity of the enzyme.

Preparative-scale hydroxylation of lysine by K3H-1.

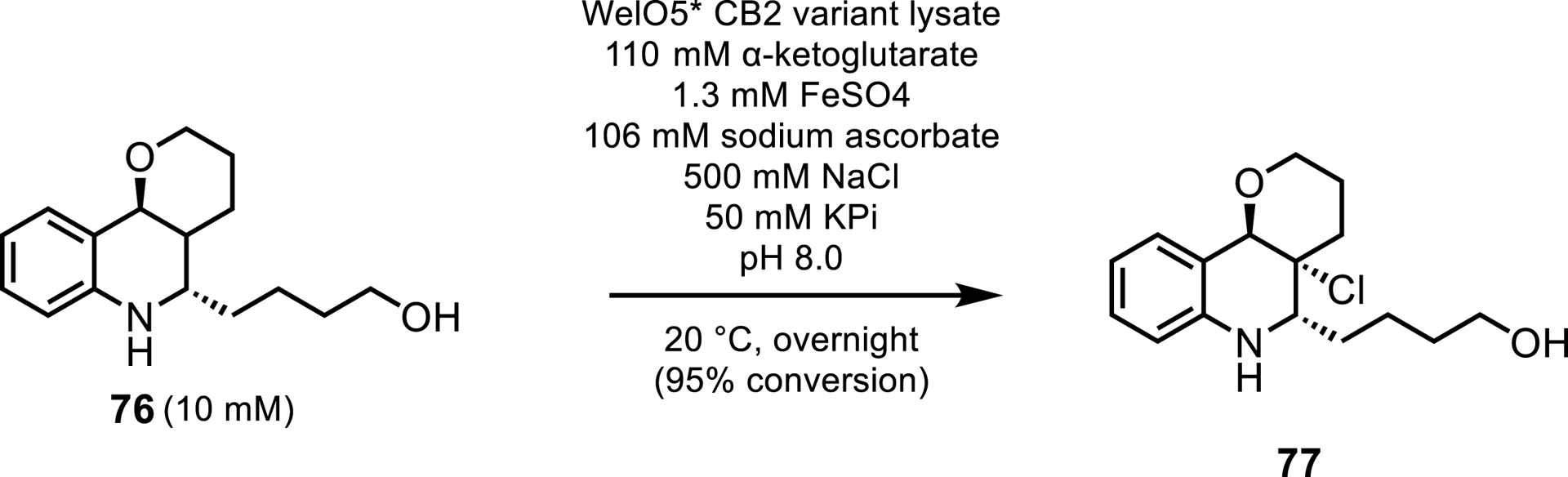

Aside from hydroxylations, halogenations with Fe/αKG enzymes are being reported more frequently in the literature. In 2005 the first Fe/αKG halogenase, SyrB2, was discovered to perform monochlorination of a L-threonine substrate covalently tethered to carrier protein, SyrB1 [71]. The requirement of a carrier protein limited the biocatalytic applicability of these enzymes. However, in 2014, WelO5, isolated from Fischerella ambigua and Hapalosiphon welwitschia, was identified as the first Fe/αKG halogenase to work on a freestanding small molecule. WelO5 performed a stereoselective monochlorination of an aliphatic carbon in the native substrates 12-epi-fischerindole U and 12-epi-hapalindole C [72], and has subsequently been engineered for biocatalytic applications. Mutagenesis studies on these halogenases were performed by Novartis and the Buller team in Switzerland [73, 74], using a homolog of WelO5 called WelO5∗ with 95% sequence identity from Hapalosiphon welwitschia. This was the first study to evolve a Fe/αKG halogenase for a substrate other than the native indole-alkaloids. Hayashi et al. were able to evolve WelO5∗ to halogenate fragments of a substrate analog of martinelline 76, a bradykinin receptor agonist. After two rounds of mutagenesis, the final variant was able to perform both chlorination and bromination to the martinelline core analog reaching 95% conversion at 10 mM substrate loadings (Scheme 35). It was noted that this mutant reduced the formation of unwanted side products, exhibiting 290- and 400-fold increases in TTN and catalytic efficiency, respectively, over the wild-type enzyme. No diastereoselectivity of the catalyst was reported in the work of Hayashi et al.

Halogenation of a martinelline core analog.

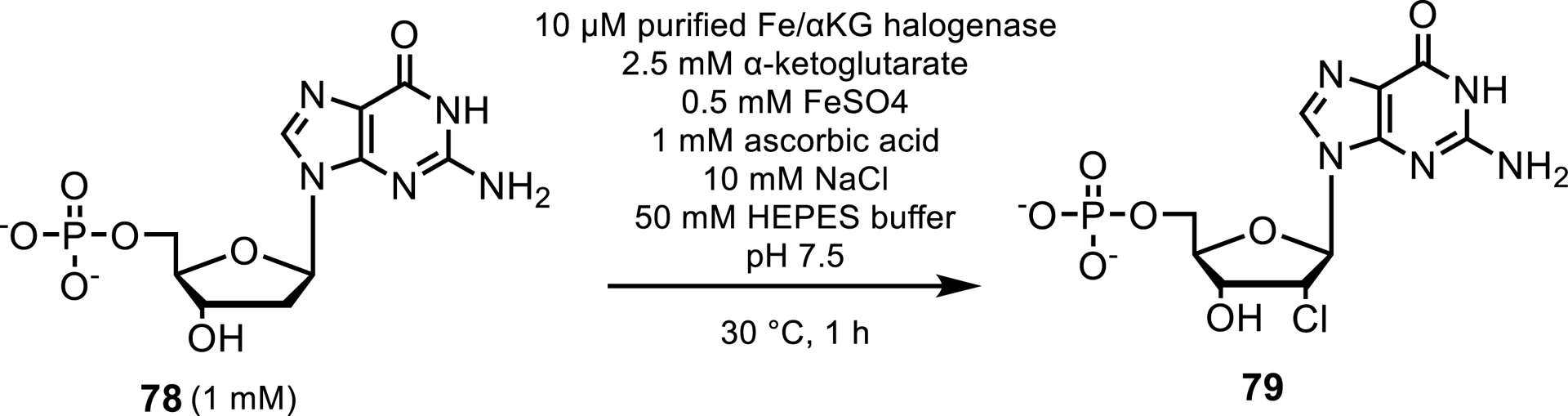

The Fe/αKG halogenases act on natural products. However, Fe/αKG amino acid halogenases and Fe/αKG nucleotide halogenases have also recently been discovered. BesD catalyzes the chlorination, bromination and azidation of aliphatic carbons in amino acids [75]. In 2020, an Fe/αKG nucleotide halogenase called AdeV was the first Fe/αKG to perform halogenations of nucleotides by carrying out a C2′-chlorination to 2′-deoxyadenosine-5′-monophosphate (dAMP) 78 (Scheme 36) [76]. Despite the narrow substrate scope of AdeV, these nucleotide halogenases have the potential to catalyze the halogenation of nucleotide analogs for therapeutic purposes such as anticancer medicine like clofaribine or antiviral drugs such as uprifosbuvir. Recent developments in nucleotide halogenases have been made by Ni et al. [77] who have identified enzymes VaNTH and CtNTH which can carry out chlorinations, brominations and azidations at the C2′ position of 2′-deoxyguanosine monophosphate (dGMP) and exhibit a more than 43-fold improvement in catalytic efficiency when compared with AdeV acting on dAMP. Furthermore Ni et al. demonstrated that the activity and nucleotide specificity can be modulated with engineering, demonstrating the potential that these enzymes hold for nucleotide modifications.

8. Monoamine oxidases

Monoamine Oxidases (MAOs) selectively oxidize amines to form imines with the aid of molecular oxygen and a flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD) cofactor, producing hydrogen peroxide as a byproduct. A monoamine oxidase from Aspergillus niger (MAO-N) was first discovered by Schilling and Lerch [78] and exhibits high S-stereoselectivity for amines at the α-carbon position. This can be exploited in kinetic resolutions and deracemizations to access a single (R)-enantiomer of an amine starting material when combined with a chemical reducing agent such as BH3NH3. Wild type MAO-N exhibits a narrow substrate scope of alkylamines but this has been substantially broadened by engineering, with three key variants D5, D9 and D11 often employed [79].

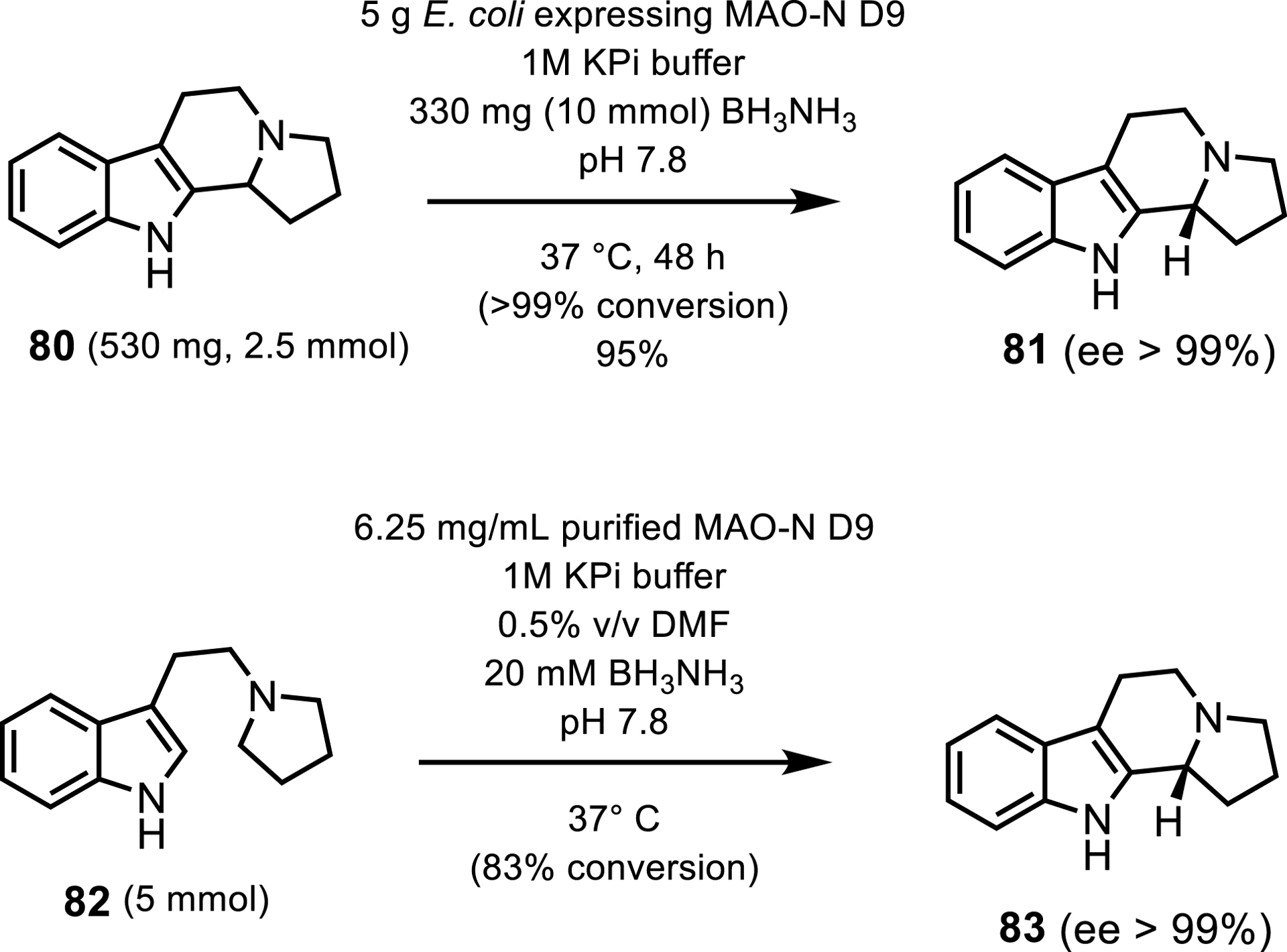

The pharmaceutical applicability of these MAO-N variants was demonstrated by the analytical-scale syntheses of solifenacin and levocetirizine. Their utility outside of deracemizations was also demonstrated by two approaches with the MAO-N D9 variant via the synthesis of (R)-harmicine 81, an alkaloid which shows anti-leishmania activity [79]. The first approach to synthesizing this active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) involved a deracemization step to afford the final product in more than 99% ee and 95% yield. The second approach reduced the overall syntheses to two synthetic steps by using an oxidative asymmetric Pictet–Spengler reaction resulting in more than 99% ee and 83% conversion (Scheme 37).

Two routes to (R)-harmicine with MAO-N D9.

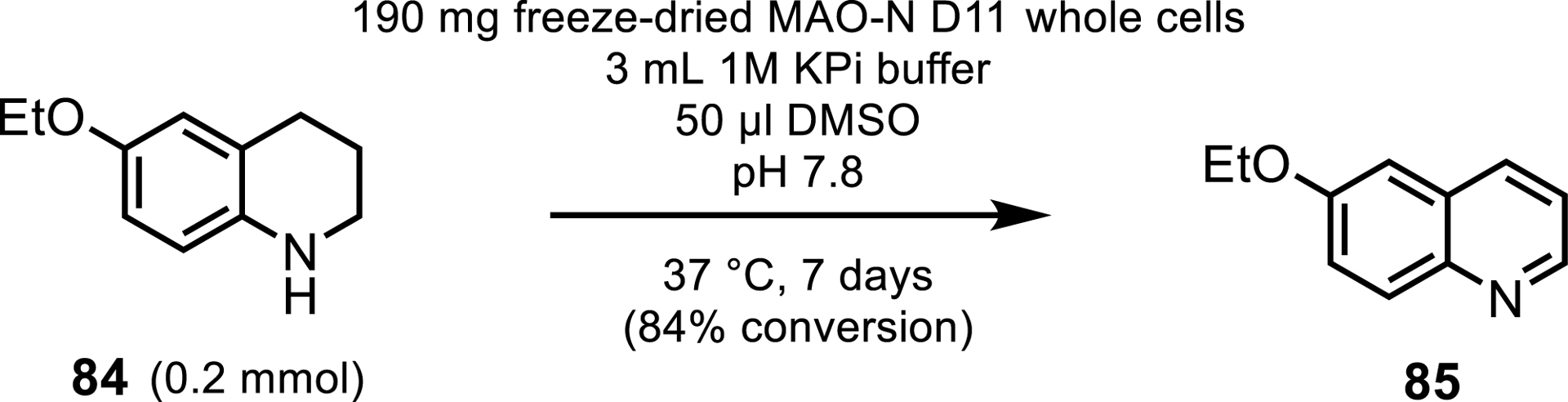

Recently, it has been demonstrated that MAOs can oxidize 1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinolines (THQs) into quinolines and 2-quinolones [80] which are prevalent scaffolds in many APIs. Biotransformations were successful with unsubstituted or electron-donating substituents to THQ, with the ethoxy-substituted THQ affording 84% conversion (Scheme 38). However, bulkier or electron-withdrawing substituents performed poorly. In-silico studies did note that steric and binding constraints may be hindering the activity with bulkier substituted substrates. To overcome this, Xiang et al. also employed a horseradish peroxidase.

Synthesis of a quinoline heterocycle by MAO-N D11 variant.

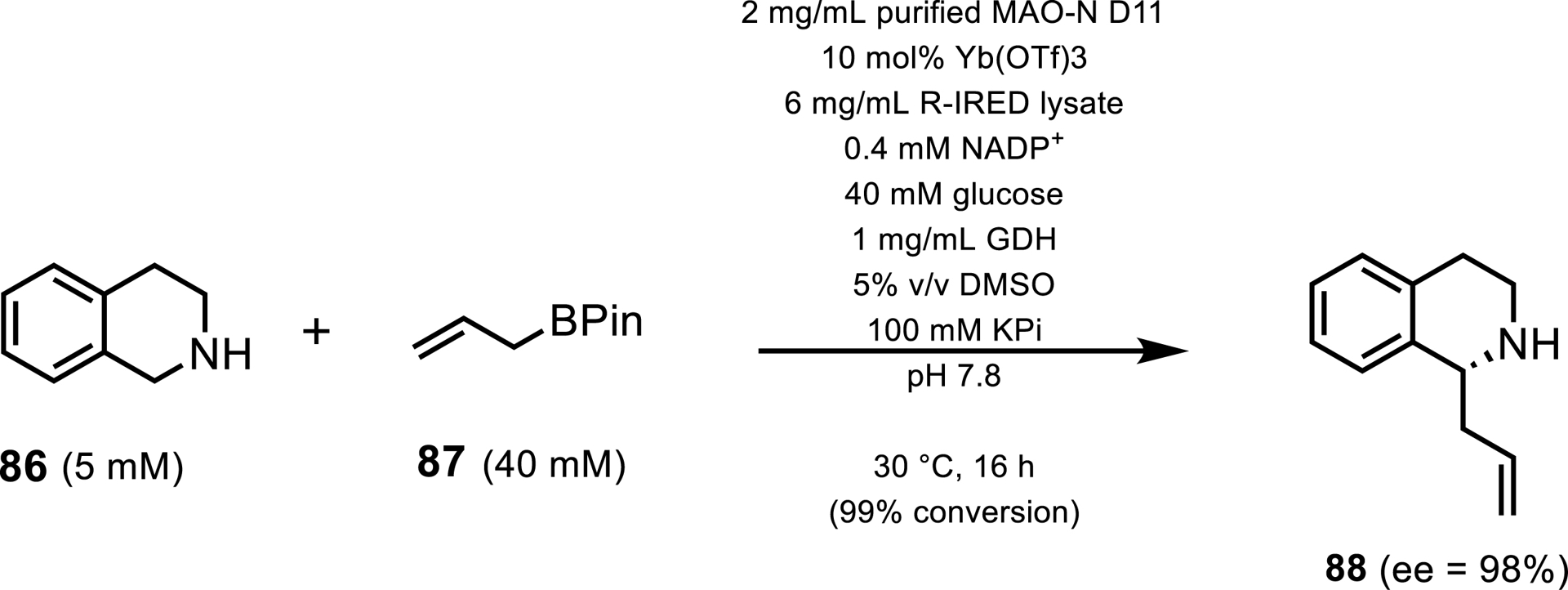

This focus on THQ-like molecules was taken even further by the Turner group. They introduced a chemoenzymatic cascade where they employed MAO-N and R-IRED enzymes alongside a chemical allylation resulting in C–C bond formation at the C1 position of tetrathydroisoquinoline (THIQ) 86 [81]. Sangster et al. noted that there have been few reports of enantioselective allylation of cyclic imines despite their prevalence in many pharmaceutical scaffolds. Here they demonstrated that the scaffolds can be synthesized on a preparative scale at high enantioselectivity of up to 98% ee and purified yields of 64% (Scheme 39). Furthermore, on analytical scales, a range of substituents both on the aryl ring and boryl–allyl partner were accepted with good conversions, albeit lower ee values, demonstrating the broad substrate scope that can be reached by this cascade.

Enzymatic cascade using MAO-N D11 and an R-IRED for the allylation of tetrahydroisoquinolines.

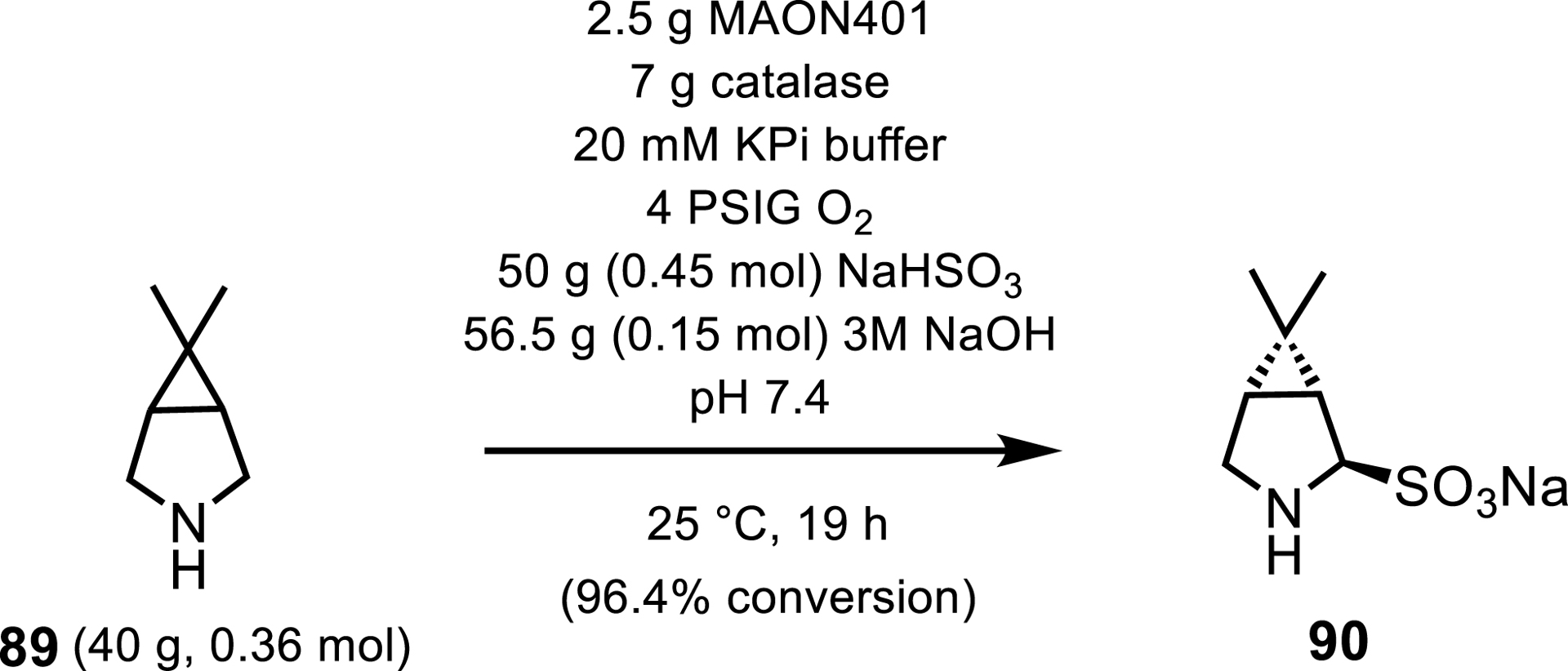

However, MAOs have not only been used to synthesize APIs on an analytical scale. Merck and Codexis employed a MAO for the synthesis of protease inhibitor boceprevir, used in the treatment of chronic hepatitis C infections [82]. MAO-N was evolved through 4 engineering rounds into MAON401, which replaced a synthetic resolution step in the synthesis of the P2 moiety of boceprevir 90. By replacing this synthetic step, Merck increased the product yield by 150% and reduced overall process waste (E-factor) by 63.1%, demonstrating the environmental advantages of employing biocatalytic steps in industrial processes (Scheme 40). The stereoselectivity of this MAO-N-catalyzed step was not reported.

MAO synthetic step in the synthesis of the P2 moiety of boceprivir.

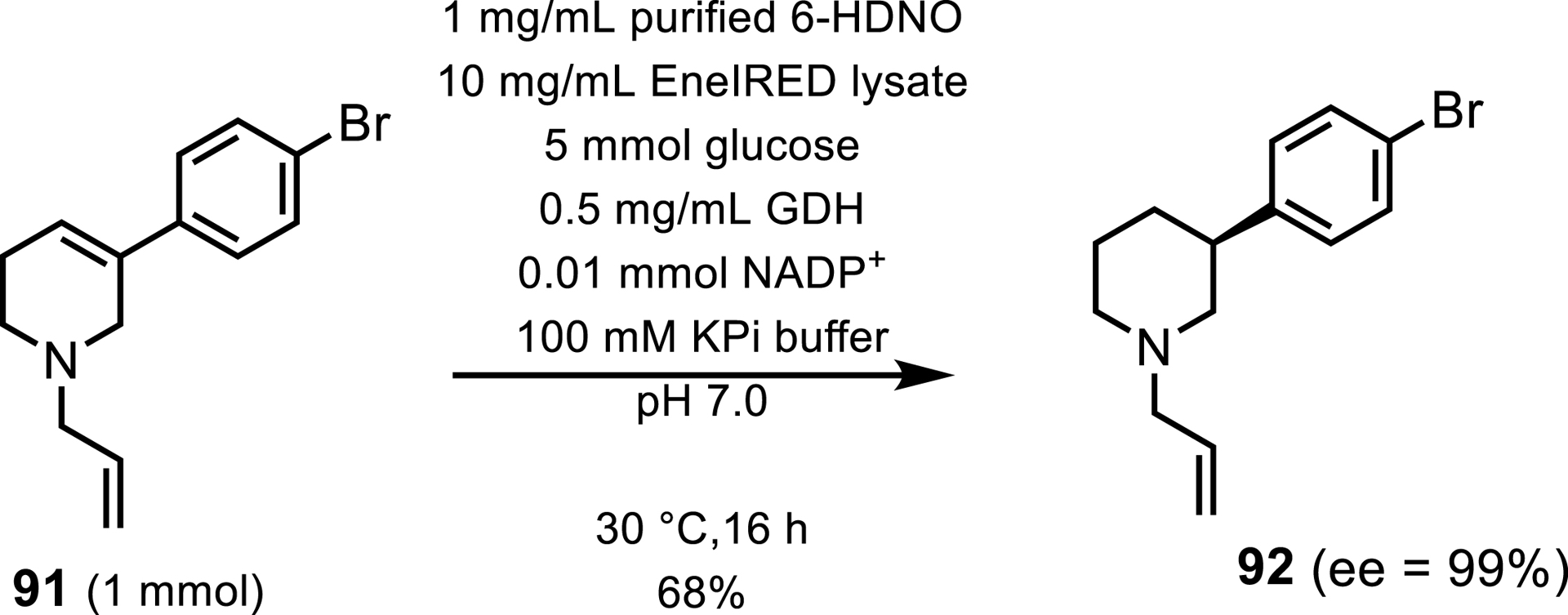

Aside from MAO-N, other S-selective FAD-dependent monoamine oxidases have been identified including human monoamine oxidases MAO-A [83], MAO-B [84], and cyclohexylamine oxidase from Brevibacterium oxydans [85, 86]. Only one R-selective MAO is reported in the literature by Heath et al. [87] 6-hydroxy-D-nicotine oxidase (6-HDNO) has been shown to isolate secondary and tertiary S-amines upon enzyme engineering. 6-HDNO has been included in cascades alongside IREDS [88]. Such a cascade reported by Harawa et al. [89] employs 6-HDNO and an EneIRED for the synthesis of 3-substituted and 3,4-disubstituted piperidines as intermediates in the synthesis of ovarian cancer drug Niraparib. 6-HDNO oxidizes a tetrahydropyridinium (THP) to form a dihydropyridinium (DHP) which is then enantioselectively reduced by an EneIRED to form the 3-substituted piperidine, which was obtained in 68% yield (Scheme 41).

Enzymatic cascade using 6-HDNO and an eneIRED for the synthesis of a Niraparib intermediate.

9. Hydrolases

Hydrolases are a well-established enzymatic class in biocatalysis, represented by a broad range of enzymes, operating on esters and amides (hydrolysis catalyzed by proteases, esterases, and lipases); alcohols and amines (in lipase-catalyzed acylations); and nitriles and epoxides (hydrolysis catalyzed by nitrilases and epoxide hydrolases, respectively). Their mechanisms involve a catalytic triad to enable catalysis [90]. Lipases are hydrolases that can operate in the presence of organic solvents, including biphasic systems and without a strict immobilization requirement [91]. The following examples, highlight various substrates and typical conditions employed for preparative-scale applications.

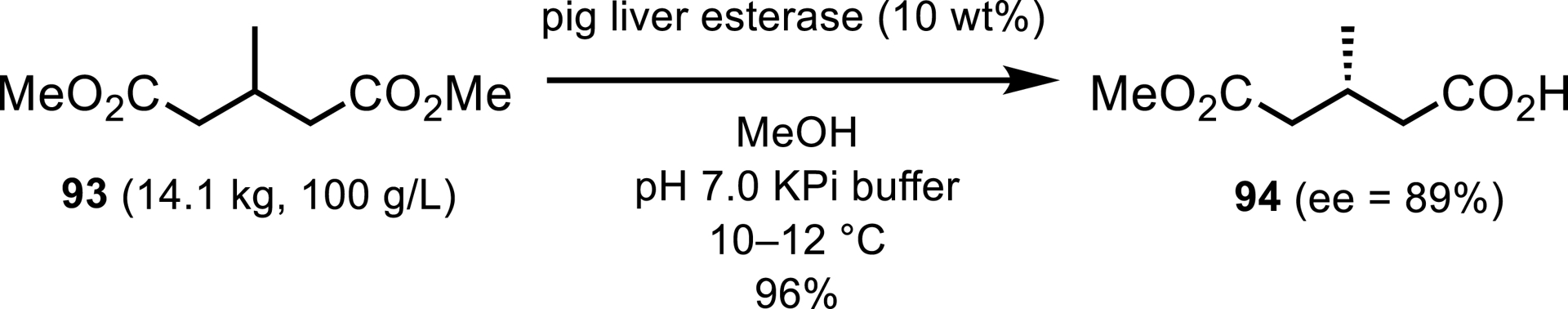

A biocatalytic desymmetrization was employed in the synthesis of the chiral lactam motif of the CGRP receptor antagonist (VIII). Researchers at Merck developed an esterase-catalyzed hydrolysis of the symmetrical diester 93 to achieve the chiral monoacid 94 in high yield (96%) (Scheme 42) [43]. Commercially available pig liver esterase was used for this transformation which was successfully scaled to multikilogram scale at high substrate loading (100 g/L). Only a modest ee of 89% was obtained from this enzymatic process, which could however be efficiently increased to 99% by a chiral salt resolution in a subsequent synthetic step.

Esterase desymmetrization in the synthetic process of CGRP receptor antagonist (VIII).

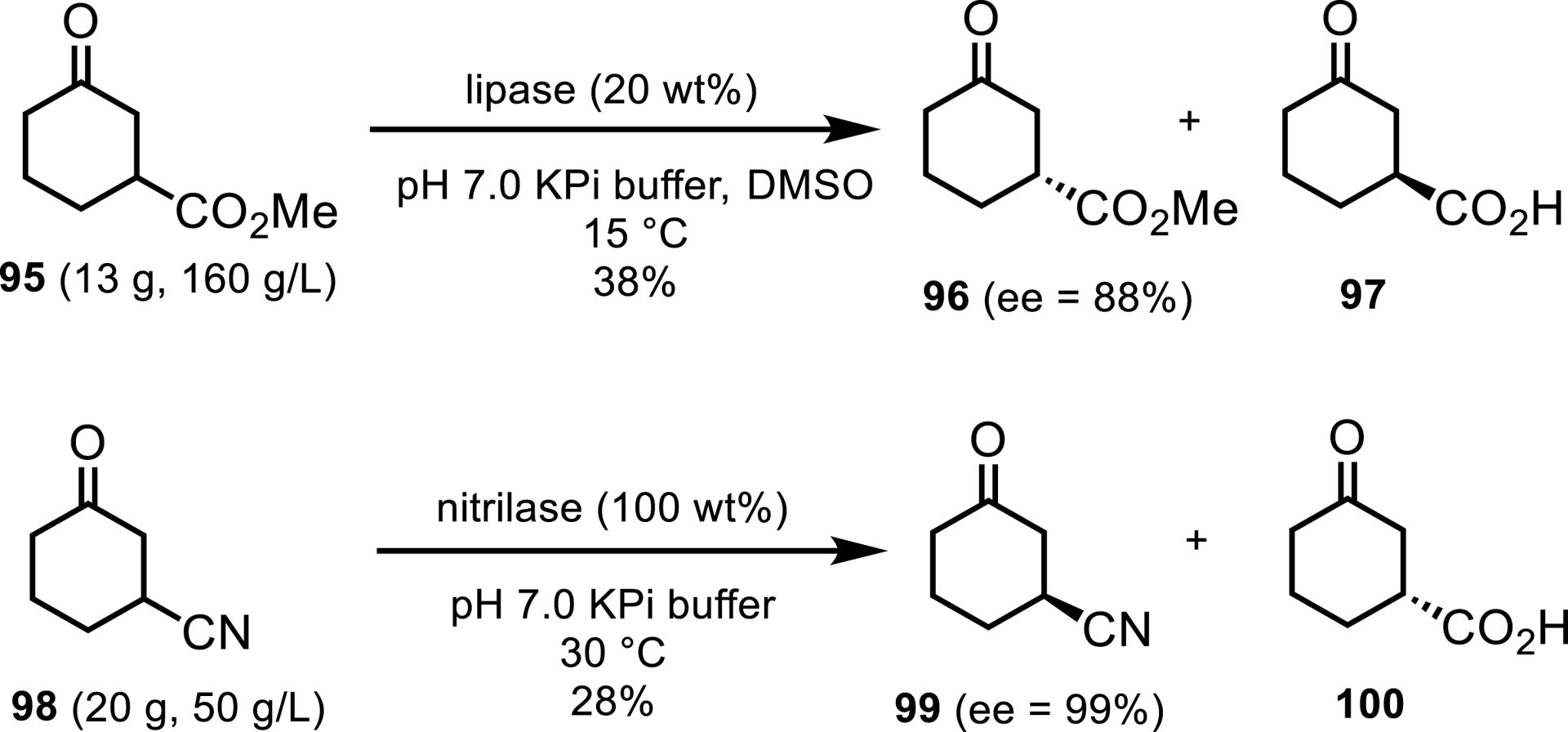

Researchers at GSK developed hydrolase resolutions to the enantiocomplementary compounds 97 and 100 (Scheme 43) [92]. A commercial lipase and a wild-type nitrilase were selected from screening for rapid process enablement to deliver multigram quantities of each material.

Lipase and nitrilase approaches to synthesize chiral 3-substituted cyclohexanone building blocks.

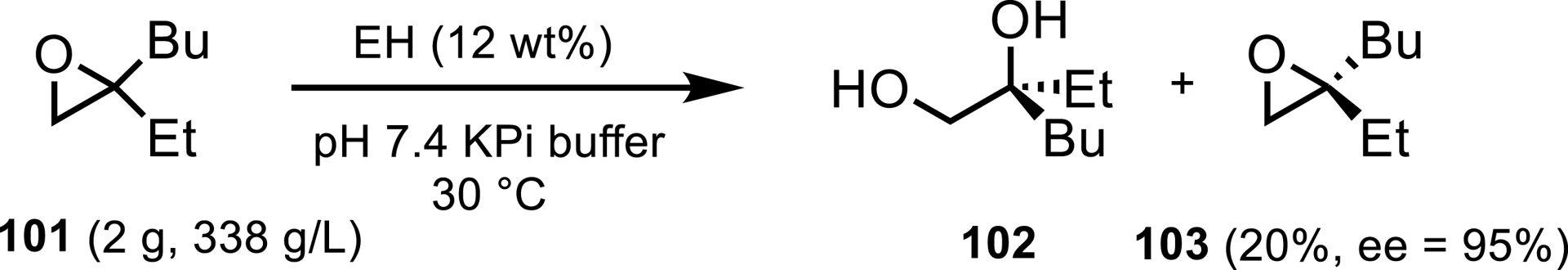

An epoxide hydrolase (EH) process was developed by GSK to resolve racemic epoxide 101, a key intermediate used to access the ileal bile acid transport (iBAT) inhibitor GSK2330672 (XVII) for type 2 diabetes and cholestatic pruritus (Scheme 44) [93]. The wild-type enzyme used for this reaction was identified from a panel comprised of literature and metagenomically sourced biocatalysts. This enzyme had sufficient activity and substrate tolerance to enable a 22 g scale-up with very high substrate loading (338 g/L). It was noted that enzyme engineering may be able to improve the selectivity of the enzyme to increase the yield of 103 while maintaining high enantioselectivity.

Epoxide hydrolase resolution involved in the synthetic process of an acid transport (iBAT) inhibitor GSK2330672.

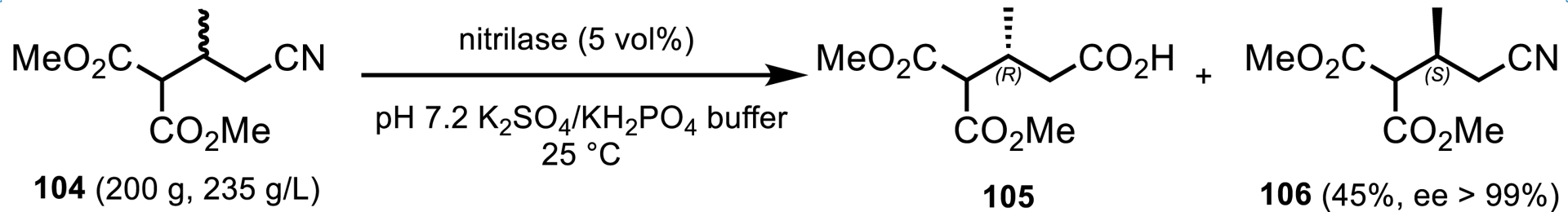

Genentech and Roche utilized a nitrilase to access an enantiopure nitrile building block for ipatasertib (Scheme 45) [94]. As part of their efforts to develop a long-term manufacturing synthesis of this API, a nitrile resolution process was developed in which the (R)-enantiomer of racemic nitrile 104 was selectively hydrolyzed to the corresponding acid 105, leaving the desired (S)-enantiomer 106 unreacted. A commercial enzyme from c-LEcta GmbH was employed in this transformation as a liquid preparation. It was found that high concentrations of sulfate and phosphate ions enhanced the enzyme activity and polar organic cosolvents had a detrimental effect on the enzyme performance. This led to a process being implemented on 200 g scale at very high substrate loading (235 g/L) without organic cosolvents (Scheme 45).

Nitrilase resolution process to access an enantiopure nitrile building block for ipatasertib.

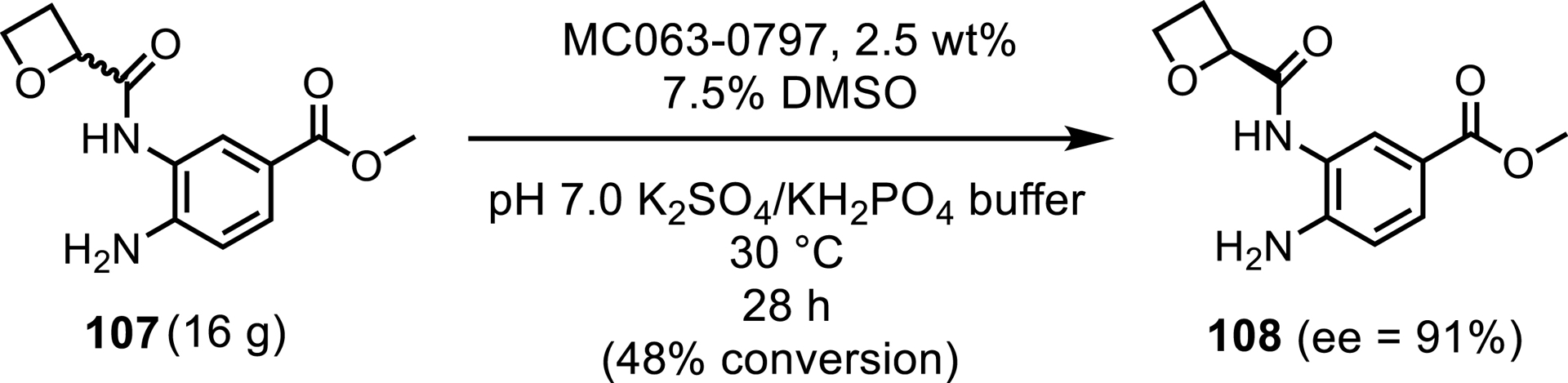

Another example of a successfully implemented hydrolase into a biocatalytic process involved an engineered variant of MC064, MC064-0797. This hydrolase was responsible for resolving a key racemic amide 107 in the synthetic process of an oral late-stage glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist (GLP-1-RA) used in the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and for weight loss [95, 96]. Two rounds of enzyme engineering improved the wild-type enzyme to support a 16 g reaction at low enzyme loads of 2.5 wt% (Scheme 46). The reaction yielded a close to perfect resolution of 48% conversion and 108 with an ee of 91%. The ee of the resulting product could be improved by using a chiral salt crystallization as a subsequent step.

A hydrolase resolution used to synthesize a key chiral intermediate in the synthetic process of a glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist (GLP-1-RA).

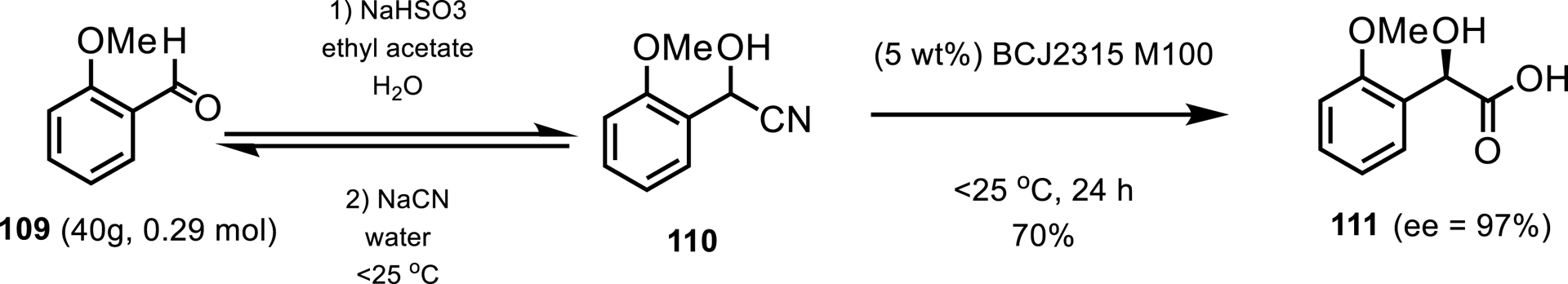

A nitrilase was also employed by Gilead and Almac for the enantioselective, dynamic kinetic resolution of (R)-2-methoxymandelic acid 111 [97]. A one-pot process was devised to exploit the reversible nature of the cyanohydrin formation step by performing a dynamic kinetic resolution with nitrilase BCJ2315 isolated from Burkholderia cenocepacia J2315. A multipronged approach was developed to improve the reaction performance and reduce enzyme deactivation by carrying out process development alongside in-silico-guided enzyme engineering. A scaled-up process at 10 g/L substrate loadings with the M100 mutant resulted in 70% isolated yield and 97% ee in 111 (Scheme 47).

One-pot preparation of (R)-2-methoxymandelic acid.

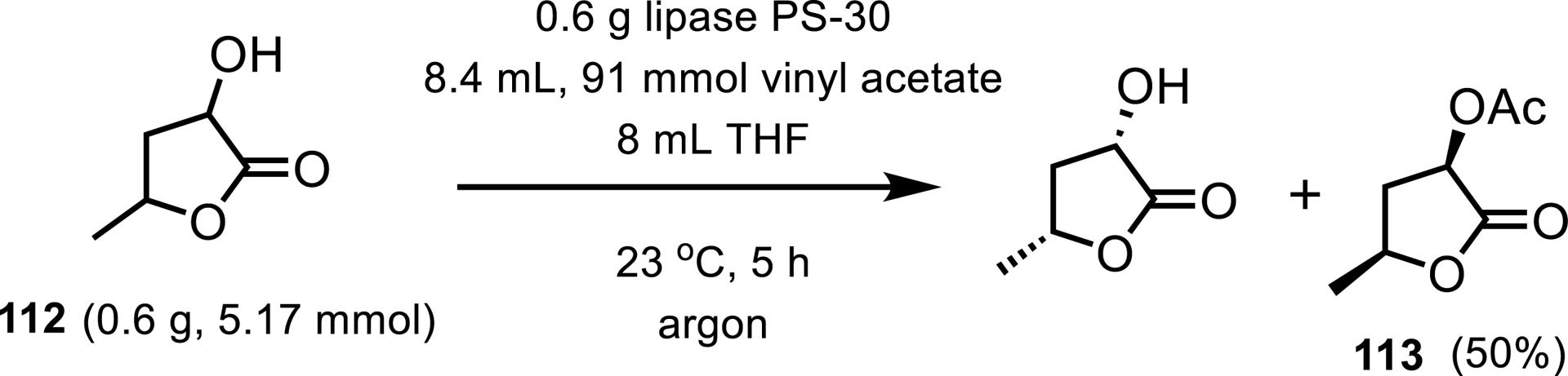

Ghosh and Nyalapatla presented a total synthesis of (+)-amphirionin-4 which exhibits proliferation-promoting activity in ST-2 cells [98]. This synthetic route includes a lipase resolution step to isolate an acetate intermediate 113 with readily available Burkholderia cepacia lipase (Amano PS-30). Using lipases in biocatalytic reactions is beneficial in this process since it requires a high solvent content. The resilience of this lipase to nonaqueous environments is demonstrated in the following example where approximately 50% of the reaction solution was THF (Scheme 48).

10. Enzyme and process engineering considerations

Enzyme engineering has proven to be a key enabler to developing biocatalytic processes in the pharmaceutical sector [99, 100]. However, the rapid engineering of enzymes for complex and insoluble substrates remains a bottleneck. The use of computational tools to design and accelerate enzyme engineering is proving to be of vital importance in the development of robust enzyme catalysts [101, 102, 103]. Among those, machine-learning-assisted enzyme engineering and ancestral sequence reconstruction (ASR) have the potential to accelerate enzyme engineering [104, 105, 106, 107, 108, 109]. High-throughput platforms include microfluidics with enhanced capabilities to acquire enzyme kinetic data. These novel methods have the potential to make game changing leaps in how biocatalysis development is performed, particularly by enabling the screening of more complex multisite recombination libraries [110, 111, 112, 113].

From a process chemistry implementation perspective, the solubility and complexity of substrates, and the need to run processes at high substrate loadings, often lead to processes operating as slurries. Efficient protein removal remains a challenge which is especially heightened in cascade processes when there are many enzymes present in the system. Ultimately, enzymes engineered for high specific activity and stability, enabling high utilization factors (ratio of substrate load to enzyme load), are required to minimize challenges in downstream processing. A strong control strategy demands fate and purge studies of enzymes, and monitoring using gel electrophoresis and MS techniques has become essential. Moreover, well-defined process acceptable ranges (PARs), ensuring robustness and easily defined normal operating ranges (NORs) for enzyme steps, minimizes failures at manufacturing scale. Although there is great promise for the successful combination of flow chemistry and biocatalysis, the vast majority of biocatalysis processes are still run in batch mode, mainly due to substrate insolubility in aqueous solutions. The scientific literature is dominated by examples of immobilized enzymes operated in packed bed reactors, however, there is huge potential for growth in the flow biocatalysis area on alternative systems [114, 115, 116]. Photobiocatalysis is an emerging area in the field of biocatalysis; during the past few years, it has been used to generate new reaction pathways for asymmetric synthesis, resulting in new-to-nature transformations enabled by photo-bio-redox systems, in situ production of hydrogen peroxide, as well as cascade reactions [117, 118].

11. Final remarks

As demonstrated by the examples mentioned in this review, biocatalysis continues to be highly impactful for key synthetic challenges in the pharmaceutical industry. Well-established enzyme classes such as ketoreductases and transaminases have become the go-to methods for the synthesis of chiral alcohols or amines, respectively, as well as hydrolases for desymmetrizations or resolution processes. In addition, imine-reductase, reductive aminases and ene-reductases have increasingly joined the top tier of enzymes enabling highly feasible transformations [92].

Looking ahead to the continued growth of biocatalysis implementation in the pharmaceutical industry, certain gaps in the biocatalytic toolbox remain. Amide bond synthesis, present in many pharmaceutical drugs is still a challenge, despite advances being made in the use of ligases for these transformations [119, 120, 121]. Functional group interconversions starting from carboxylic acids are still underexploited, and carboxylic acid reductases (CARs) offer great potential to bridge the gap and enable amine and alcohol synthesis from acid derivatives [122]. Continued development that involves engineering and efficient enzyme expression of these complex ATP-dependent reactions is anticipated in the coming years. Enzymatic halogenations have great potential for pharmaceutical synthesis due to the ubiquitous presence of halogens in pharmaceutical route scouting. Implementable enzymatic solutions remain elusive primarily due to low catalytic activities and very limited substrate specificity [123, 124]. Applications of underutilized biocatalysts for the synthesis of chiral amines, sulfoxides, carboxylic acids, and amino acid analogs is mainly associated to low activities and limited substrate scope [125]. Finally, there are still limited options for general C–C bond forming in biocatalytic transformations; despite lyase-catalyzed C–C bond formation being represented in scattered examples over the past two decades, there is a need for the discovery of novel and broad scope enzymes to perform enzymatic carboligations [126, 127]. The repertoire of reactions available to synthetic chemists is rapidly growing, aided by the emergence of sophisticated computational tools to sort through ever-expanding public and private enzyme databases [128, 129, 130].

Declaration of interests

The authors do not work for, advise, own shares in, or receive funds from any organization that could benefit from this article, and have declared no affiliations other than their research organizations.

CC-BY 4.0

CC-BY 4.0