1 Introduction

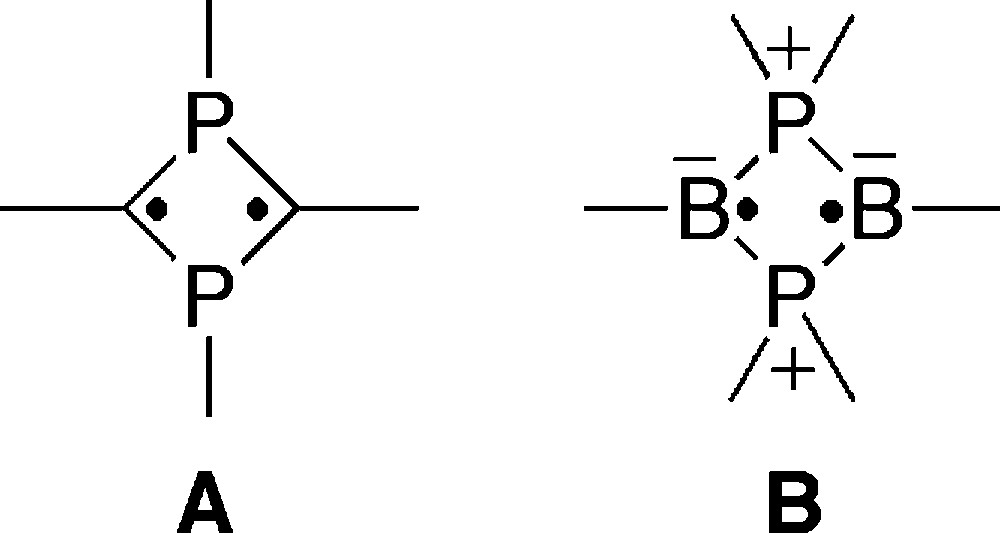

A sterically protected 1,3-diphosphacyclobutane-2,4-diyl, A, is one of the isolable biradicals containing heavier main group elements [1–3]. Their 4-membered cyclic biradical moiety is perturbed by the neighboring phosphorus atoms to form a particular singlet state [4,5]. At the same time, substituents at the phosphorus atoms in A affect the electronic structure of the 4-membered biradical moiety. In fact, ab initio calculations for several substituted 1,3-diphosphacyclobutane-2,4-diyls demonstrated that the energetic difference between singlet and triplet states depends on properties of substituents especially at the phosphorus centers [4]. Thus, introduction of various substituents on the phosphorus atoms is of strong interest when one prepares compounds with new functionality in these single biradical systems (Scheme 1).

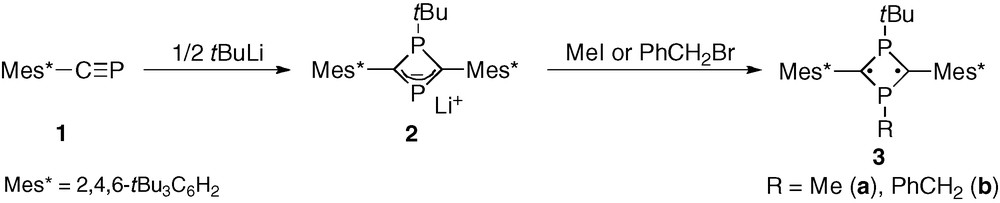

Biradicals composed of phosphorus and boron B represent an interesting variant on this singlet biradical via direct atom substitution in the ring [6,7]. As an alternate synthesis of isolable 1,3-diphosphacyclobutane-2,4-diyls described in the report of Niecke and co-workers in 1995 [8], we established a convenient method for construction of air-stable 1,3-diphosphacyclobutane-2,4-diyls 3 by utilizing nucleophilic reaction of cyclic phosphaallyl anions, 2. The anion 2 is conveniently available from the reaction of phosphaalkyne 1 (Mes* = 2,4,6-tri-tert-butylphenyl) with anionic nucleophiles [9]. The neutral monoradical of 2 is produced by the interesting oxidation of the anion with iodine [10]. These two findings demonstrate a wide versatility of the phosphaallyl anions 2. Scheme 2 illustrates that a variety of 1,3-diphosphacyclobutane-2,4-diyls may be obtained from the phosphaalkyne, 1, by employing appropriate choices of the nucleophiles (only t-BuLi is depicted) and electrophiles. Synthetic procedures developed thus far have enabled the isolation of various kinds of 1,3-diphosphacyclobutane-2,4-diyl derivatives containing hydrocarbon-substituents such as alkyl or aryl groups [11–14].

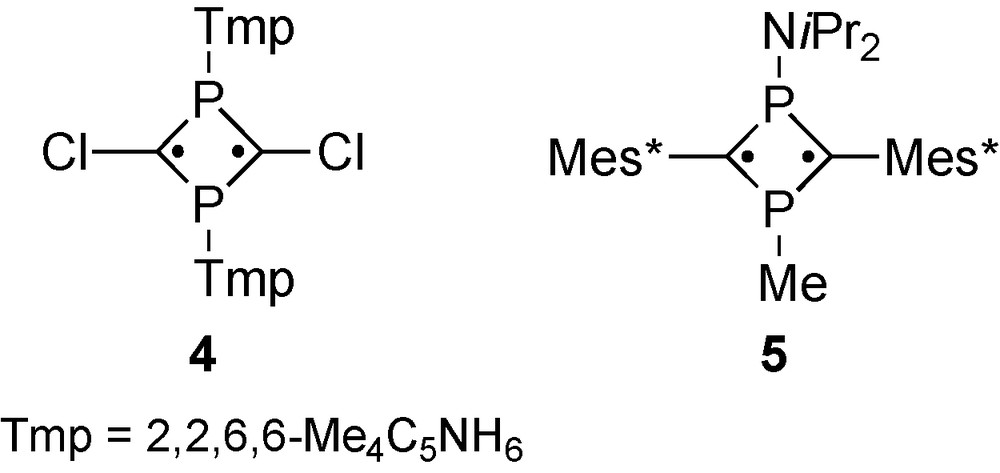

The number of the P-heterocyclic biradicals containing P–X moieties, wherein X denotes a heteroatom, is limited in some synthetic approaches because of the reduced stability leading to the valence isomerization to a 1,4-diphosphete skeleton in the case of 4 (Tmp = 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidinyl) [15]. We also found that the stability of 5 containing diisopropylamino group is disappointingly low precluding the handling of these materials under normal atmosphere conditions [11,13]. Nevertheless, properties of 1,3-diphosphacyclobutane-2,4-diyls bearing heteroelement-containing groups remain attractive for providing insight into the nature of the P-heterocyclic biradicals. Hence, stable compounds similar to 4 or 5 remain important targets (Scheme 3).

We can now report that 3-sulfanyl-1,3-diphosphacyclobutane-2,4-diyls show considerable stability thus enabling manipulations under air.

2 Results and discussion

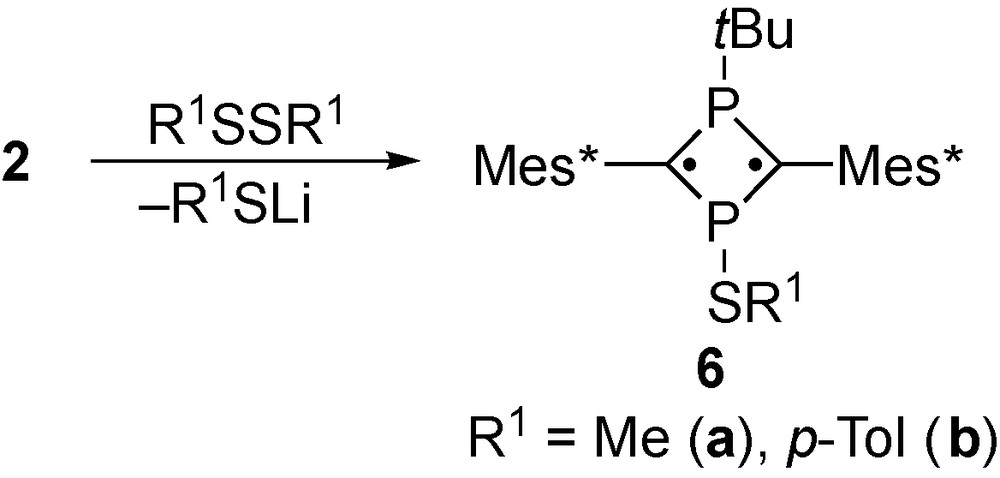

Phosphaalkyne 1 [9] was allowed to react with tert-butyllithium to obtain the cyclic phosphaallyl anion 2 as a room-temperature stable species. A solution containing 2 was treated with dimethyl- and di-p-tolyl disulfides as electrophiles to afford the corresponding sulfanyl-substituted 1,3-diphosphacyclobutane-2,4-diyls 6, as air-stable greenish-blue crystalline substances (Scheme 4). Compound 6b (R1 = p-Tol) showed extremely high stability over 6 months in air, whereas 6a gradually decomposed in air over 1 month. Nevertheless, 6 can be handled under ambient conditions in sharp contrast to the stability previously reported for 5.

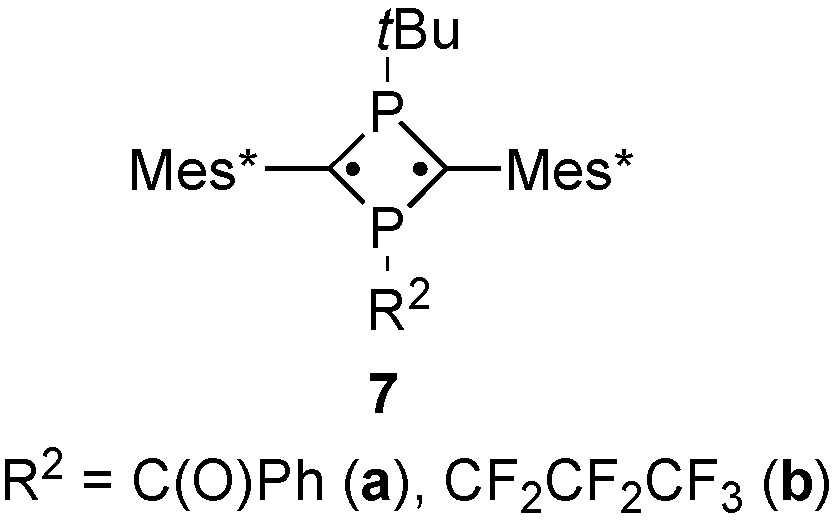

In the 31P NMR spectra of 6, lower-field chemical shifts were observed for the tBuP moiety, which is similar to 1,3-diphosphacyclobutane-2,4-diyls bearing benzoyl (7a) [11] or perfluoropropyl groups (7b) [13] as electron-withdrawing substituents. Similarly to the previous data for 6, the 2JPP values were smaller than those of hydrocarbon-substituted 1,3-diphosphacyclobutane-2,4-diyls. In the 13C NMR spectrum of 6, the sp2 carbons in the 4-membered ring were observed at around δC 105 with 1JPC constants of ca. 30 Hz. Slightly higher-field shift and larger coupling constants were comparable to those data observed for 7 (Scheme 5).

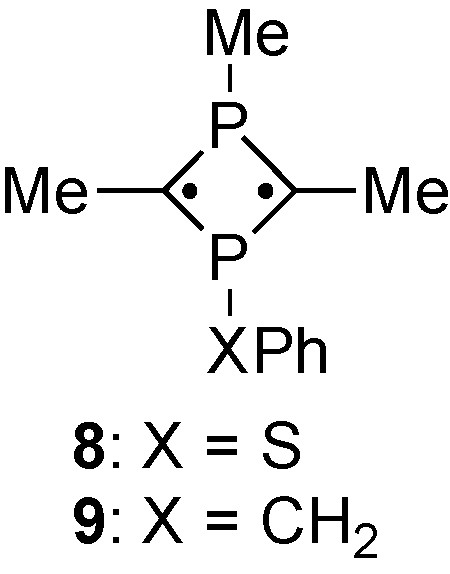

UV–vis spectra of 6 showed substantial red-shift of the longest wavelength band (6a: 640 nm; 6b: 643 nm), which was also observed in 7a (664 nm) [11]. Therefore, the sulfanyl groups appear to function as an electron-withdrawing substituent, that reduces the HOMO-LUMO energetic gap inductively. DFT calculations were performed for 8 as a model for 6b and 9 as a model for 3b, wherein Mes* and t-Bu groups were replaced with methyl and p-Tol group was replaced by phenyl (Scheme 6). The modeling results for 8 indeed show a smaller HOMO-LUMO gap (2.37 eV) compared to that of 9 (2.54 eV) at the B3LYP/6-311 + G(d,p) level [16] (See supplementary data). In addition to the UV–vis properties of 6, redox potentials indicating substituent effects on the sulfur atom were also briefly investigated (See supplementary data for initial studies. Further work on this aspect is in progress).

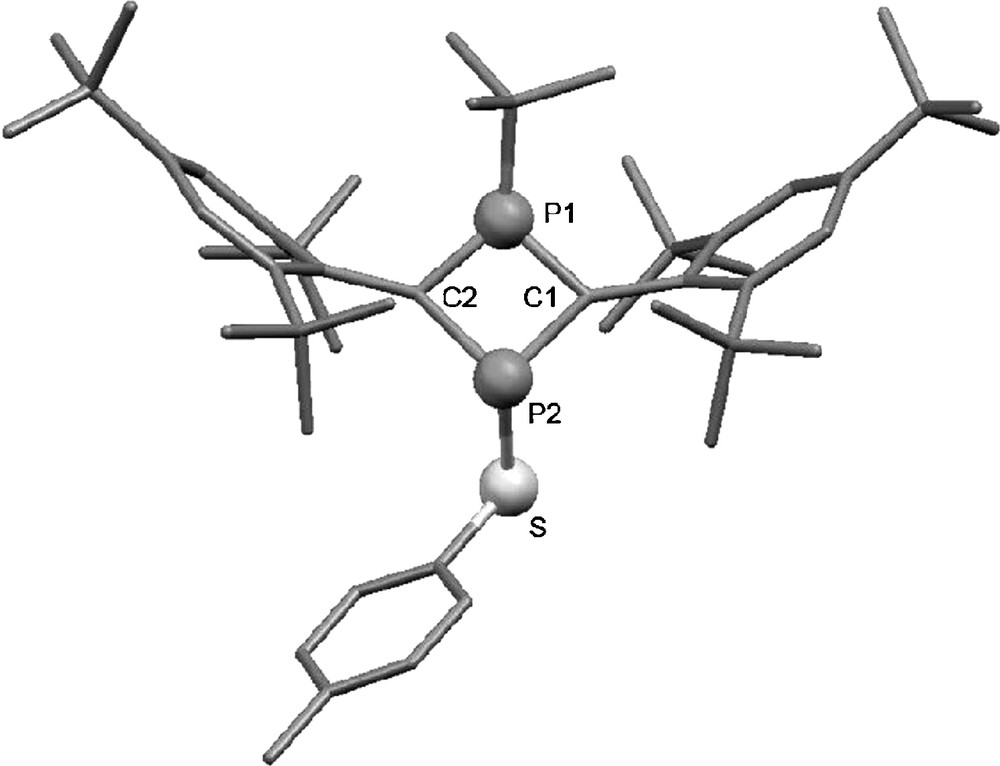

Recrystallization of 6b from dichloromethane afforded single crystals suitable for structural determination by X-ray diffraction (Fig. 1). Although quality of the crystals is insufficient to obtain enough diffraction data for detailed discussion of all metrics, the data obtained confirm the expected structure of 6b and provide guidance on gross structural features including distorted aromatic rings. The P–C distances in the planar P2C2 ring [Θ(P1–C1–P2–C2) 6.2(3)°] are intermediate between P–C single- and PC double-bonds [17]. The planar sp2 geometries of the carbon centers in the P2C2 ring [Σ(C1) = 359.6°, Σ(C2) = 357.7°] and pyramidalization of the phosphorus atoms [Σ(P1) = 346.8°, Σ(P2) = 312.9°] remain characteristic, and the P–C distances to the less-pyramidalized phosphorus are also comparatively short. The C1…C2 long distance of 2.54 Å appears to exhibit no ordinary covalent bond between the sp2 carbon atoms in the diphosphacyclobutane ring. To avoid steric congestion, the Mes* groups tilt by 60–62° from the planar 4-membered P2C2 ring and the aromatic rings are slightly distorted to a boat-like structure [Θ(Cmeta – Cortho – Cipso – Csp2): 150.3, 150.8, 150.9, 152.9°] [18]. Both aromatic rings of the Mes* groups face towards tBuP, possibly due to CH–π interaction [19] or packing effect in the crystalline state. These structural aspects of 6b are almost the same as those observed for 3 [9,12,13]. In other words, geometric parameters of the P-heterocyclic biradical moiety are not dramatically changed by sulfanyl substitution, in contrast to the pronounced electronic changes.

X-ray structure of 6b. Hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity. The p-t-Bu group in one of the Mes* groups connecting to the C2 atom is disordered and the atoms with predominant occupancy factor (0.58) are shown. Some selected bond distances (Å) and angles (°): P1–C1 1.701(6), P1–C2 1.710(6), P1–C(tBu) 1.863(5), P2–C1 1.813(5), P2–C2 1.817(6), P2–S 2.137(2), C1–C(Mes*) 1.468(8), C2–C(Mes*) 1.481(8), S–C(Tol) 1.800(6), C1–P1–C2 96.2(3), C1–P2–C2 88.7(3), P1–C1–P2 87.4(3), P1–C2–P2 87.0(3).

3 Conclusion

A new class of 1,3-diphoshacyclobutane-2,4-diyls bearing alkylsulfanyl and arylsulfanyl group together with the sterically demanding Mes* groups have been prepared as air-stable compounds. An X-ray structure of the sulfanyl P-heterocyclic biradicals shows no significant geometric deviation from the known P2C2 skeletons. On the other hand, UV-vis and NMR spectra and redox properties suggest that the sulfanyl groups behave as electron-withdrawing substituents to reduce the HOMO–LUMO gap and electron-donating potentials. Such electronic perturbation by these sulfur-containing groups can be utilized for exploration of novel functional materials based on this biradical system.

4 Experimental section

4.1 General

All manipulations were carried out under an argon atmosphere by the standard Schlenk technique. All solvents employed were dried by appropriate methods. 1H, 13C and 31P NMR spectra were recorded with a Bruker Avance 400 or an AV 300 spectrometer with Me4Si (1H, 13C) and H3PO4 (31P) as internal and external standards. Mass spectra were recorded with a Bruker APEX3 spectrometer. UV-vis spectra were recorded with a Hitachi U-3210 spectrometer. Electrochemical analyses were performed with a BAS CV-50W voltammetric analyzer. X-ray diffraction data were collected on a Rigaku RAXIS-IV imaging plate detector. Phosphaaalkyne 1 was prepared according to the method reported previously from 2,2-dibromo-1-(2,4,6-tri-tert-butylphenyl)-1-phosphaethene (Mes*P = CBr2) [11].

4.2 1-tert-Butyl-3-methylsulfanyl-2,4-bis(tri-tert-butylphenyl)-1,3-diphosphacyclobutane-2,4-diyl (6a)

tert-Butyllithium (0.18 mmol, 1.4 M solution in pentane) was added to a solution of 1 (100 mg, 0.35 mmol) in THF (5 mL) at –78 ̊C and stirred for 10 min. The reaction mixture was allowed to warm to room temperature and stirred for 1 h. To the solution containing 2 was added dimethyl disulfide (0.18 mmol) and subsequently stirred for 1 h. The volatile materials were removed in vacuo, and the residue was extracted with hexane. The hexane extract was concentrated in vacuo, and the residual solid was washed with ethanol to afford 6a as a deep blue solid (43 mg, 36%).

Mp 135–137 ̊C (decomp); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 0.72 (d, 3JP,H = 14.8 Hz, 9H, tBuP), 1.28 (s, 18H, p-tBu), 1.60 (s, 18H, o-tBu), 1.61 (s, 18H, o-tBu), 2.32 (d, 3JP,H = 11.6 Hz, 3H, CH3), 7.20 (s, 2H, m-Mes*), 7.37 (s, 2H, m-Mes*); 31P{1H} NMR (162 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.7 (d, 2JP,P = 299.7 Hz, SMeP), 70.1 (d, 2JP,P = 299.7 Hz, tBuP); 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 16.9 (dd, 2JP,C = 22.8 Hz, 4JP,C = 9.7 Hz, SCH3), 28.8 (pt, (2JP,C + 4JP,C)/2 = 3.8 Hz, PCMe3), 31.3 (s, p-CMe3), 33.3 (d, 5JP,C = 10.7 Hz, o-CMe3), 34.5 (s, p-CMe3), 34.9 (s, o-CMe3), 37.3 (s, o-CMe3), 38.5 (s, o-CMe3), 47.2 (dd, 1JP,C = 42.4 Hz, 3JP,C = 5.2 Hz, PCMe3), 106.6 (dd, 1JP,C = 37.1 Hz, 1JP,C = 27.6 Hz, CP2), 120.0 (s, m-Mes*), 122.4 (d, 4JP,C = 2.4 Hz, m-Mes*), 132.0 (d, 3JP,C = 4.9 Hz, ipso-Mes*), 145.2 (d, 5JP,C = 1.4 Hz, p-Mes*), 148.0 (d, 3JP,C = 10.6 Hz, o-Mes*), 151.4 (dd, 5JP,C = 10.3 Hz, 5JP,C = 1.8 Hz, o-Mes*); UV-vis (CH2Cl2) λmax (ɛ) = 640 (750), 390 (12700), 331 (11900 M–1cm–1) nm; ESI-MS Calcd. for C43H70P2S, 680.4668. Found, m/z 680.4670.

4.3 1-tert-Butyl-3-p-tolylsulfanyl-2,4-bis(tri-tert-butylphenyl)-1,3-diphosphacyclobutane-2,4-diyl (6b)

In a similar procedure to the preparation of 6a, the reaction of 1 (0.35 mmol), tert-butyllithium (0.18 mmol) with di-p-tolyl disulfide (0.18 mmol) afforded 53 mg of 6b (40% yield).

Blue solid, Mp 138–139 ̊C (decomp); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 0.78 (d, 3JP,H = 14.8 Hz, 9H, tBuP), 1.30 (s, 18H, p-tBu), 1.47 (s, 18H, o-tBu), 1.67 (s, 18H, o-tBu), 2.30 (s, 3H, CH3), 6.97 (d, 3JH,H = 8.0 Hz, 2H, C6H4), 7.21 (s, 2H, m-Mes*), 7.27 (d, 3JH,H = 8.0 Hz, 2H, C6H4), 7.40 (s, 2H, m-Mes*); 31P{1H} NMR (162 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.9 (d, 2JP,P = 293.4 Hz, SC6H4P), 72.4 (d, 2JP,P = 293.4 Hz, tBuP); 13C{1H} NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 21.1 (s, CH3), 28.8 (pt, (2JP,C + 4JP,C)/2 = 3.6 Hz, PCMe3), 31.3 (s, p-CMe3), 33.4 (d, 5JP,C = 10.3 Hz, o-CMe3), 34.5 (s, p-CMe3), 34.9 (s, o-CMe3), 37.3 (s, o-CMe3), 38.5 (s, o-CMe3), 47.8 (dd, 1JP,C = 43.3 Hz, 3JP,C = 3.6 Hz, PCMe3), 105.2 (dd, 1JP,C = 30.1 Hz, 1JP,C = 26.4 Hz, CP2), 120.0 (s, m-Mes*), 122.2 (s, m-Mes*), 129.3 (s, C6H4), 129.3 (s, C6H4), 131.9 (d, 3JP,C = 5.2 Hz, ipso-Mes*), 134.8 (d, 5JP,P = 3.0 Hz, C6H4), 137.2 (s, C6H4), 145.4 (s, p-Mes*), 148.3 (d, 3JP,C = 10.8 Hz, o-Mes*), 152.0 (t, {3JP,C + 3JP,C}/2 = 5.6 Hz, o-Mes*); UV-vis (CH2Cl2) λmax (ɛ) = 643 (740), 391 (13400), 333 (14200 M–1cm–1) nm; ESI-MS Calcd. for C49H74P2S, 756.4981. Found, m/z 756.4983.

4.4 DFT calculations

Computations were performed with the Gaussian03 (revision D.01) quantum chemical program package [16]. DFT calculations were performed at the B3LYP/6-311 + G(d,p) level for model compounds 8 and 9.

4.5 X-ray crystallography for 6b

A Rigaku RAXIS-IV imaging plate detector with graphite-monochromated MoKα radiation (λ = 0.71070 Å) was used. The structure was solved by direct methods (SIR92) [20] expanded using Fourier techniques (DIRDIF94) [21] and then refined by full-matrix least squares on F for variable parameters. The positions of the hydrogen atom on phosphorus were refined. The data were corrected for Lorentz polarization effect. Structure solution, refinement, and graphical representation were carried out using the teXsan package [22]. C49H74P2S, greenish deep-blue prisms (from dichloromethane), MW = 757.13, crystal dimensions = 0.20 × 0.15 × 0.10 mm3, monoclinic, space group P21/c (#14), a = 13.829(1), b = 193.503(2), c = 17.410(1) Å, β = 102.061(4)̊̊, V = 4592.2(7) Å3, Z = 4, λ = 0.71070 Å, T = 123 K, ρcalcd = 1.095 g cm–3, μMoKα = 0.171 mm–1, F000 = 1620, 33645 total reflections, 9467 unique reflections (Rint = 0.153), R1 = 0.109 (I > 2σ(I)), wR = 0.204, S = 1.04 (467 parameters) (CCDC-764366).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (No. 13304049) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan, the Program Research, Center for Interdisciplinary Research, and the Support for Young Researchers, Graduate School of Science, Tohoku University, Casio Science Promotion Foundation, the National Science Foundation (CHE-0413521, CHE-0342921), US Department Energy Grant (DE-FG02-86ER13465), and the Department of Energy, Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy under the Hydrogen Storage Grand Challenge (DE-PS36-03GO93013). We thank Prof. Koichi Mikami at Tokyo Institute of Technology and Prof. Takeaki Iwamoto at Tohoku University for their valuable comments.

Appendix A Supplementary data

Supplementary data: CV data for 6a and 6b and DFT calculation results for 8 and 9 are available. Crystallographic data for 6b (CCDC-764366) can be obtained free of charge from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.